JEAN-LOUIS-ERNEST MEISSONIER LA BARRICADE , 1848 (THE BARRICADE)

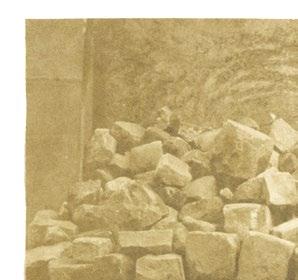

GUSTAVE LE GRAY (ATTRIBUTED)

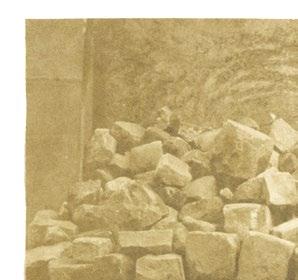

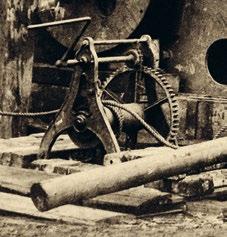

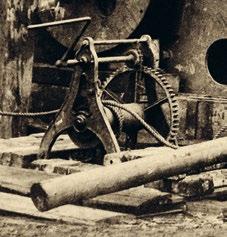

TAS DE PAVÉS , FROM ALBUM REGNAULT , CA. 1849–1855 (PILE OF COBBLESTONES)

1

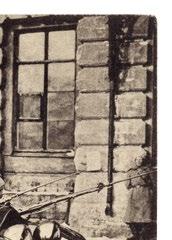

CHARLES FRANÇOIS THIBAULT

LA BARRICADE DE LA RUE SAINT-MAUR-POPINCOURT AVANT L’ATTAQUE PAR LES TROUPES DU GÉNÉRAL LAMORICIÈRE, LE DIMANCHE 25 JUIN 1848 , 1848 (THE BARRICADE OF THE RUE SAINT-MAURPOPINCOURT BEFORE THE ATTACK BY GENERAL LAMORICIÈRE’S TROOPS, SUNDAY, JUNE 25, 1848)

2

CHARLES FRANÇOIS THIBAULT LA BARRICADE DE LA RUE SAINT-MAUR-POPINCOURT APRÈS L’ATTAQUE PAR LES TROUPES DU GÉNÉRAL LAMORICIÈRE, LE LUNDI 26 JUIN 1848 , 1848 (THE BARRICADE OF THE RUE SAINT-MAURPOPINCOURT AFTER THE ATTACK BY GENERAL LAMORICIÈRE’S TROOPS, MONDAY, JUNE 26, 1848)

3

HIPPOLYTE BAYARD

RUE ROYALE ET RESTES DES BARRICADES DE 1848 , 1848 (RUE ROYALE AND THE REMAINS OF THE BARRICADES OF 1848)

4

WILLIAM EDWARD KILBURN

WILLIAM EDWARD KILBURN

5

THE CHARTIST MEETING ON KENNINGTON COMMON, 10 APRIL 1848 , 1848

UNKNOWN

PHOTOENGRAVING BASED ON A DAGUERREOTYPE OF CHARLES FRANÇOIS

THIBAULT, FROM THE MAGAZINE

L’ILLUSTRATION , NO. 279–280, 1848

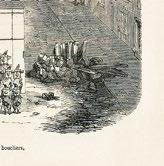

UNKNOWN L’ATTAQUE À L’ABRI DES

BOUCLIERS , FROM THE MAGAZINE L’ILLUSTRATION , NO. 285, 1848 (THE ATTACK UNDER COVER OF SHIELDS)

6

UNKNOWN

PHOTOENGRAVING BASED ON A DAGUERREOTYPE OF WILLIAM EDWARD KILBURN, FROM THE MAGAZINE THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS , APRIL 15, 1848

7

THOMAS THURLOW STREET SCENE, BOY IN A DONKEY CART , CA. 1847 9

10

ROBERT P. NAPPER GROUP OF GYPSIES: ANDALUSIA , FROM THE ALBUM VISTAS DE ANDALUCÍA , CA. 1860

JOSEPH KORDYSCH

11

MENDIANT, PODOLIE , BEF. 1886 (OLD BEGGAR FROM PODOLIA)

GUSTAVE DE BEAUCORPS

GRENADE, GITAN ASSIS JOUANT DE LA GUITARE , CA. 1858

(GRANADA: SITTING GYPSY PLAYING GUITAR)

12

CHARLES CLIFFORD

VISTA DE LA PLAZUELA Y PUERTA PRINCIPAL DE ENTRADA AL CAPRICHO CON GRUPO DE DEPENDIENTES , FROM THE ALBUM VISTAS FOTOGRAFIADAS DE LA ALAMEDA, DEL PALACIO DE MADRID, DEL DE GUADALAJARA Y DE LA CASA DE LOS MENDOZAS EN TOLEDO (HOY INCLUSA) PERTENECIENTES AL EXMO. SR. DUQUE DE OSUNA Y DEL INFANTADO , CA. 1856 (VIEW OF THE LITTLE PLAZA AND MAIN ENTRANCE TO CAPRICHO)

13

CHARLES NÈGRE

LES RAMONEURS EN MARCHE , 1851–1852 (CHIMNEY SWEEPS ON THE MARCH)

14

15

JOHN THOMSON BEGGARS , FROM THE ALBUM FOOCHOW AND THE RIVER MIN , CA. 1871

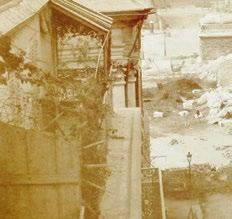

CHARLES MARVILLE PERCEMENT DE L’AVENUE DE L’OPÉRA: BUTTE DES MOULINS (DE LA RUE SAINT-ROCH) , 1876–1877 (BUILDING THE AVENUE DE L’OPÉRA: THE BUTTE DES MOULINS FROM RUE SAINT-ROCH)

17

18

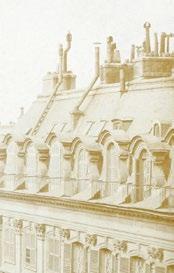

CHARLES CLIFFORD

CHARLES CLIFFORD

19

PUERTA DEL SOL, 2ª VISTA , 1857 (PUERTA DEL SOL, 2ND VIEW)

THOMAS ANNAN

CLOSE, NO. 37 HIGH STREET , 1868–1871

FERDINAND VON STAUDENHEIM

STADTBEFESTIGUNG: LINIENWALL—SPIELENDE KINDER , FROM THE SERIES LEBEN UND TREIBEN AUF DEN LINIENWÄLLEN , CA. 1890 (CITY FORTIFICATION: LINIENWALL— CHILDREN PLAYING)

AUGUST STAUDA

NUSSGASSE 1—BLICK GEGEN VEREINSSTIEGE , 1906 (1 NUSSGASSE—VIEW WITH THE STAIRS OF THE CLUB)

20

21

FREDERIC BALLELL LA RAMBLA: ENLLUSTRADOR DE SABATES , 1907–1908 (LA RAMBLA: BOOTBLACK)

EUGÈNE ATGET SUR LES QUAIS—LA SIESTE , 1904 (ON THE BANKS—THE NAP)

22

UNKNOWN

WIEN, SCHLAFENDE , FROM THE POSTCARD SERIES WIENER STRASSENLEBEN , 1906–1907 (VIENNA: SLEEPING)

UNKNOWN

SCHUHPUTZER , 1906–1907 (BOOTBLACK)

23

UNKNOWN

WRANGELSTRASSE 11, 4 TREPPEN , FROM THE PUBLICATION UNSERE WOHNUNGS-ENQUETE IM JAHRE 1906/7 , EDITED BY ALBERT KOHN, 1907–1908 (11 WRANGELSTRASSE, STAIR 4)

HEINRICH ZILLE

FRAU MIT KORB VOR DER SILHOUETTE DER WESTEND-KOLONIE , 1899 (WOMAN WITH BASKET BEFORE A SILHOUETTE OF THE WESTEND-KOLONIE)

25

UNKNOWN

PRESOS TRABAJANDO EN LA CARRETERA DE MADRID A VALENCIA POR LAS CABRILLAS , CA. 1850–1851 (PRISONERS WORKING IN THE CABRILLAS ROAD FROM MADRID TO VALENCIA)

PAGES 28–29: CHARLES CLIFFORD PRESA DEL PONTÓN DE LA OLIVA , 1855 (PONTÓN DE LA OLIVA DAM)

27

NADAR

CATACOMBES DE PARIS: MANNEQUIN Nº 1 , CA. 1861 (PARIS CATACOMBS: MANNEQUIN NO. 1)

30

TIMOTHY O’SULLIVAN AT WORK: GOULD & CURRY MINE , 1868 31

UNKNOWN

WHEEL TIRE TRANSPORT, FROM THE SERIES WORK SCENES FROM THE KRUPP WORKS AT ESSEN , 1899

LOUIS-ÉMILE DURANDELLE

ORNAMENTAL SCULPTURE, FROM THE PUBLICATION LE NOUVEL OPÉRA DE PARIS: STATUES DÉCORATIVES, GROUPES ET BAS-RELIEFS , 1875–1876

32

33

34

ROBERT HOWLETT

ROBERT HOWLETT

35

THE GREAT EASTERN: WHEEL AND CHAIN DRUM , 1857

FREDERIC BALLELL LA MAQUINISTA TERRESTRE Y MARÍTIMA (FACTORY), CA. 1910

UNKNOWN

FACTORY WORKER, FROM THE SERIES WORK SCENES FROM THE KRUPP WORKS AT ESSEN , 1899

36

37

CHARLES NÈGRE ASILE IMPÉRIAL DE VINCENNES, L’INFIRMERIE , 1857–1860 (IMPERIAL ASYLUM AT VINCENNES, THE INFIRMARY)

39

UNKNOWN

J.M. CHARCOT ET UNE PATIENTE ATAXIQUE , 1875 (J.M. CHARCOT AND AN ATAXIC PATIENT)

NADAR HERMAPHRODITE DEBOUT , 1860 (STANDING HERMAPHRODITE)

40

41

42

LEWIS ALBERT SAYRE SPINAL DISEASE AND SPINAL CURVATURE: THEIR TREATMENT BY SUSPENSION AND THE USE OF THE PLASTER OF PARIS BANDAGE , 1877

43

44

45

JAMES GARDNER HOSPITAL AT FREDERICKSBURG, VIRGINIA , MAY 1864

46

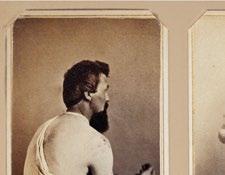

MCPHERSON & OLIVER, WILLIAM D. MCPHERSON THE SCOURGED BACK , 1863

MCPHERSON & OLIVER, WILLIAM D. MCPHERSON THE SCOURGED BACK , 1863

47

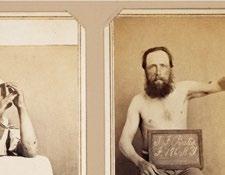

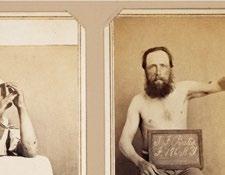

REED BROCKWAY BONTECOU ALBUM PAGES WITH “CARTES DE VISITE,” 1864–1865

48

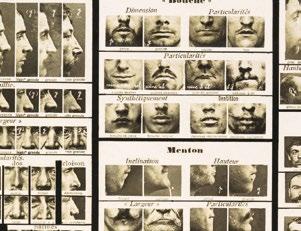

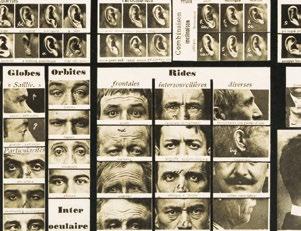

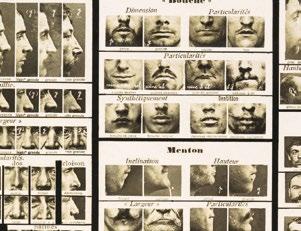

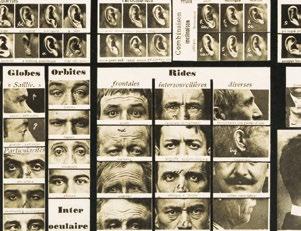

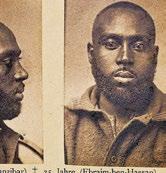

UNKNOWN INSIDE PAGES OF THE CRIMINAL , BY HAVELOCK ELLIS, 1890 49

50

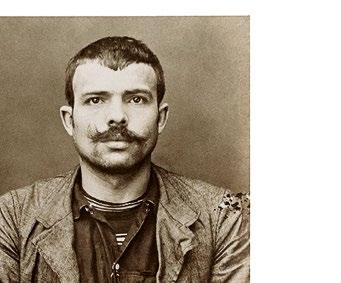

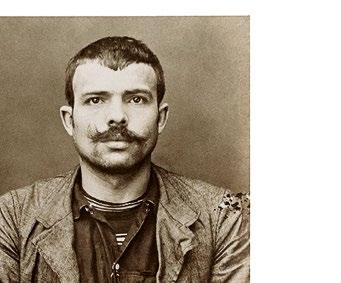

UNKNOWN TYPE OF THE LIFE SENTENCE CONVICT , 1894–1905

UNKNOWN SCHEDA SEGNALETICA CON DUE FOTOGRAFIE DI CRIMINALE, SECONDO METODO DI BERTILLON , 1894–1900

(IDENTIFICATION SHEET WITH TWO PHOTOGRAPHS OF CRIMINALS, BERTILLON’S METHOD)

51

FRANK GILBRETH AND LILLIAN GILBRETH MOTION EFFICIENCY STUDY , CA. 1914

ALPHONSE BERTILLON TABLEAU SYNOPTIC DES TRAITS PHYSIONOMIQUES , CA. 1909 (SYNOPTIC TABLE OF PHYSIOGNOMIC TRAITS)

52

53

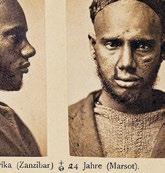

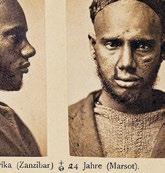

UNKNOWN OSTKÜSTE VON AFRIKA , FROM THE ALBUM ANTHROPOLOGISCHETHNOLOGISCHES

ALBUM IN PHOTOGRAPHIEN , EDITED BY CARL DAMMANN, 1875 (EAST COAST OF AFRICA)

54

55

ABY WARBURG

HOUSES IN WALPI WITH HOPI WOMAN, 1896 , SLIDE NO. 27 FROM THE LECTURE “THE SERPENT RITUAL,” 1923

56

JOHN K. HILLERS

JOHN K. HILLERS

57

PLATE 3: TERRACED HOUSES IN WOL-PI , FROM THE ALBUM MAJOR J. W. POWELL’S EXPLORATIONS, VIEWS IN THE PROVINCE OF TUSAYAN, NORTHERN ARIZONA , 1871–1879

58

BRONISŁAW MALINOWSKI

THE TASASORIA ON THE BEACH OF KAULUKUBA: STEPPING THE MASTS AND GETTING THE SAILS READY FOR THE RUN , FROM THE BOOK ARGONAUTS OF THE WESTERN PACIFIC , 1915–1916

59

BRUNO BRAQUEHAIS STATUE OF NAPOLEON FROM VENDÔME COLUMN , FROM THE ALBUM VIEWS OF THE PARIS COMMUNE , 1871

61

JEAN ANDRIEU

LA COLONNE VENDÔME APRÈS SA DÉMOLITION PAR LES COMMUNARDS LE 16 MAI 1871 , FROM THE SERIES DÉSASTRES DE LA GUERRE , 1871

(THE VENDÔME COLUMN AFTER ITS DEMOLITION BY THE COMMUNARDS ON MAY 16, 1871)

62

UNKNOWN

BARRICADE DE LA RUE DE LA ROQUETTE, PLACE DE LA BASTILLE , FROM ALBUM DE PHOTOGRAPHIES ET D’ARTICLES DE JOURNAUX SUR LA GUERRE FRANCO-PRUSSIENNE ET LA COMMUNE DE PARIS 1870–1871 , MARCH 18, 1871 (BARRICADE AT RUE DE LA ROQUETTE, PLACE DE LA BASTILLE)

63

UNKNOWN FRONT COVER OF THE ILLUSTRATED LONDON NEWS , JUNE 24, 1871 64

ALPHONSE LIÉBERT

LE THÉÂTRE LYRIQUE INCENDIE:

VUE INTÉRIEURE DE LA SALLE , FROM THE ALBUM LES RUINES DE PARIS ET SES ENVIRONS , CA. 1871 (THE THÉÂTRE LYRIQUE BURNED: INTERIOR VIEW OF THE HOUSE)

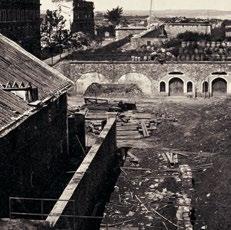

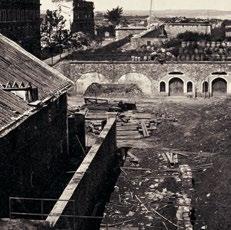

PAGES 66–67: ADOLPHE BRAUN

INTÉRIEUR S DU FORT D’ISSY ET FORT DE VANVES , FROM THE ALBUM THÉÂTRE DE LA GUERRE , 1871 (INTERIORS OF FORT D’ISSY AND FORT DE VANVES)

65

IAKOV SHTEINBERG

POSTCARD OF ARMED CAR ON GUARD, 1917

UNKNOWN

POSTCARD OF THE BARRICADE ON DOLGORUKOV STREET DURING THE DECEMBER UPRISING IN MOSCOW (1), 1905

68

UNKNOWN

POSTCARD OF THE BARRICADE ON DOLGORUKOV STREET DURING THE DECEMBER UPRISING IN MOSCOW (2), 1905

UNKNOWN

POSTCARD OF A PEACEFUL DEMONSTRATION ON DECEMBER 17, IN PETROGRAD, 1917

69

71

PAGES 70–71: VIKTOR BULLA SHOOTING AT A DEMONSTRATION ON NEVSKY PROSPEKT, PETROGRAD, JULY 4, 1917 , 1917

FREDERIC BALLELL PRIMER DE MAIG DE 1890 , 1890 (FIRST OF MAY, 1890)

72

CORNELIS LEENHEER GROUP PORTRAIT J.B. ASKEN, ERNEST BELFORT BAX, AUGUST BEBEL, ETCETERA , SIXTH CONGRESS OF THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL, AMSTERDAM, 1904

73

JOHN THOMSON

THE INDEPENDENT SHOE-BLACK , FROM THE SERIES STREET LIFE IN LONDON , 1877–1878

75

LEWIS HINE A HOT DAY ON THE EAST SIDE, NEW YORK , 1910 76

NEW YORK

1906 77

LEWIS HINE GREEK BOOTBLACKS,

, CA.

LEWIS HINE

PHOTOGRAPH OF NATIONAL CHILD LABOR COMMITTEE EXHIBIT AT THE PANAMA–PACIFIC INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA, 1915

78

PHOTOGRAPH—NEW YORK / SANDWICH MAN

FROM THE MAGAZINE CAMERA WORK , NO. 49/50, 1917 79

PAUL STRAND

,

PAUL STRAND

PAUL STRAND

80

PHOTOGRAPH—NEW YORK / BLIND WOMAN , FROM THE MAGAZINE CAMERA WORK , NO. 49/50, 1917

documentary genealogies photography 1848 –1917

“If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” said Robert Capa, one of the most important photojournalists of the twentieth century. His maxim already resonated in the mid-nineteenth century when photography began to acquire its documentary dimension. e Documentary Genealogies: Photography 1848–1917 exhibition at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía invites us to reconsider the early age of photography from a new perspective, paying closer attention to that very documentary dimension. is reappraisal is aided by the essays in this book, a carefully selected collection of critical studies that helps us delve deeper into the various issues raised by the show.

e exhibition probes the moments that preceded the birth of documentary as an artistic genre, stressing the disruptive power of the rst representations of common people and subaltern gures. Bourgeois, industrial, and colonial culture had made photography a tool for the legitimization and dispersion of its own set of values and interests.

Jorge Ribalta—researcher, writer, photographer, and curator of the exhibition—sets out the premise that, although the appearance of common people and subaltern gures in photographs from this period was always accidental or incidental, their presence nevertheless shows that photography’s documentary capacity was there from the start. is is re ected in the subordinate, or “plebeian,” status photographic works initially held within modern art. e French poet Charles Baudelaire even went so far as to describe photography as a “servant of the arts,” due to it being an industrial practice that lacked the ability, according to him, to o er anything other than an exact reproduction of nature.

is exhibition gives us the opportunity to contemplate scenes from the nineteenth and early twentieth century that are as characteristic as they are varied: the great works of infrastructure and urban reform, medical experimentation, anthropological studies, criminology research, and the numerous national, historical, and cultural heritage campaigns that were key components in promoting nationalist discourses throughout Europe.

Finally, I highlight the collaboration between the Museo Reina Sofía and the Biblioteca Nacional de España. is project is the fruit of that collaboration, enabling us to better understand modern and contemporary photography’s gestation.

MIQUEL ICETA I LLORENS MINISTER OF CULTURE AND SPORT

Documentary Genealogies: Photography 1848–1917 brings to a close a cycle of exhibitions that the Museo Reina Sofía, in conjunction with the photographer and researcher Jorge Ribalta, began over a decade ago. e aim was to o er an alternative account of how the discourse of documentary emerged within the broader history of photography.

e earlier shows in the cycle—A Hard, Merciless Light: e Worker Photography Movement, 1926–1939 (2011) and Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism (2015)— examined documentary photography’s gestation, development, and latitude in terms of the establishment of a subaltern perspective, linked in the rst case to portrayals of the industrial worker and in the second to the emergence of new political subjectivities in the 1960s and 1970s. is new exhibition, breaking with the previous chronological order, shines a spotlight on moments that anticipated these developments: documentary photography’s protohistory.

e premise for the show is that, although the birth of documentary lm or photography as a genre—as a speci c form of photographic and cinematographic poetry—occurred in the 1920s with the outbreak of working class–led amateur photography and the creation of a critical de nition for the documentary genre, photography’s documentary role is as old as photography itself. In this respect it is worth recalling Walter Benjamin’s in uential essay “ e Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” in which he points out that photography and socialism emerged at the same time. is was hardly a coincidence: looked at retrospectively, much of the iconography used by documentary photographers to depict the working classes in the interwar period was already present, if latent, in the visual culture of the 1840s.

e oldest images in the exhibition stem from this period. Here we have the rst appearance of subaltern gures—servants, beggars, laborers; the enslaved, imprisoned, and in rm—and can see the evolution of their early representation, which must be considered within the context of photography’s emergence as the driving force in a new visual regime that served the interests of the dominant class and bourgeoise and colonial culture generally. According to the symbolic logic of this new visual order, what historian André Rouillé terms the “empire of photography,” portrayals of common people and subaltern gures were essentially “accidental, gures popping up incidentally in the corner of frames focused elsewhere.” But they were also the early manifestations of “an episteme of documentary” that would, in Ribalta’s words, a ord photography a “speci c and contradictory status” within modern art.” e “documentary idea” has remained something of a counterargument

within modernity because, as an instrument-based practice, it challenges the pure autonomy aspired to by vanguard art.

e narrative arc in our exploration of documentary’s crystallization as a photographic form spans eight decades. e revolutionary cycles of 1848 and 1917 mark the beginning and the end of our tour, and not without good reason. ese two historic milestones bookend a turbulent period of revolts and reforms, seminal moments in which photography, as an emerging technology, moved away from its earlier pictorialism and aesthetic priorities to explore a more testimonial vocation. Few photographic records remain of the revolutionary episodes of 1848, considered by contemporary historians to be the moment the proletariat acquired class consciousness, but the images we do have—of barricades on the Parisian streets, for example— provide a foretaste of the apocalyptic iconography that bourgeoise culture would come to associate with popular uprisings.

e same apocalyptic iconography is much in evidence in photographic portrayals of the 1871 Paris Commune, for which a far wider repertoire of work survives. Here the emphasis is on the vandalism involved in the uprising, as would later be the case with depictions of the 1909 Tragic Week in Barcelona and the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917, events that also provided the rst images of the mobilized masses. at these kinds of images were so widely circulated goes to show how afraid the dominant classes were of the ascendent workers’ movement. e powers that be deliberately and systematically used the illustrated press to try to stigmatize and hold back working-class advances. Somewhat paradoxically, another form of photography that gave visual expression to what bourgeoise culture deemed the “other” came through projects designed to promote and strengthen nation-state ideologies. Photography albums of a nation’s historic landmarks and artistic heritage, for example, proliferated in this period and showed subaltern gures—maids, beggars, artisans—amid the monuments and civic buildings. Something similar happened with photographic reports of urban redevelopment schemes and the era’s great feats of engineering and infrastructure: images of construction workers and factory hands helped to create, intentionally or otherwise, from a perspective that inclined toward paternalism and criminalization, the rst iconography of the urban proletariat. As Ribalta observes, these images bear eloquent witness to “how much industrial capitalism prospered by radically exploiting the disempowered.”

e will to document is especially present in the vast body of photographic work that was produced with explicitly demonstrative ends. Taken to support studies in the incipient elds of anthropology and criminology, as well as for medical and forensic research, these images, apparently scienti c and neutral, were crucial in legitimizing technology-based forms of social control and discipline.

In the nal period that the exhibition deals with, the rst photographs emerge that combine the will to document with more social and emancipatory aims. is was a time when, following successive revolutionary surges and a consolidated workers’ movement, public policy initiatives nally sought to improve living conditions and social integration for the working classes. A key gure in this context is Lewis Hine, a US photographer who made exposing societal ills the focal point of his practice. His work had a clear pedagogical component, and he actively collaborated with numerous civil rights organizations, including the National Child Labor Committee, for whom he produced a celebrated series of pictures condemning child labor, engendering the documentary photography genre in the process. Hine had a huge in uence on Paul Strand, who was one of the founding fathers of modernism in photography. Strand straddled the end of one era and the start of the next, making him the logical last stop on our tour of documentary photography’s protohistory.

e exhibition’s wide range of case studies shows how, during the second half of the nineteenth century and the rst decades of the twentieth, a vast array of photographic images was produced that sought to and/or happened to provide some sort of factual record. e exhibition re ects on how this happened and invites us to delve deeper into the genealogy of the discourse of documentary photography. It brings to light how those early images foreshadowed and anticipated later historic accounts of class relations and con ict—a guiding principle in the discourse of documentary—and paved the way for bourgeoise visual culture to be penetrated by what Molly Nesbit terms “the aesthetic Other.” is book interrogates these ideas from a range of perspectives in the next essays, some of them historical texts (by Jacob Riis, Allan Sekula, and the aforementioned Hine), others written speci cally for this project.

MANUEL BORJA-VILLEL DIRECTOR OF THE MUSEO NACIONAL CENTRO DE ARTE REINA SOFÍA

LOUIS DAGUERRE BOULEVARD DU TEMPLE , 1838

THE AESTHETIC OTHER: NOTES FOR A PROTOHISTORY OF THE DOCUMENTARY IDEA

Jorge Ribalta 91 THE STREETS AND THE BARRICADES: DEMOS AND DOCUMENT IN NINETEENTHCENTURY PHOTOGRAPHY

Steve Edwards 101 1848: PICTURING PROTEST

Anne de Mondenard

119

EXCEPTIONALLY TYPICAL: SUBLIMINAL REVOLUTIONS IN THE REALM OF PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY AROUND 1848 IN CENTRAL EUROPE

Petra Trnková

127

IMAGINING THE COMMONWEALTH: ADAMSON AND HILL’S NEWHAVEN PHOTOGRAPHS

Duncan Forbes

137 RIIS’S OTHER HALF Maren Stange

147

THE OTHER HALF AND HOW THEY LIVE: STORY IN PICTURES

Jacob Riis

153

EXPOSING SOCIAL QUESTIONS: PHOTOGRAPHIC PROJECTS IN THE VIENNA OF THE LONG NINETEENTH CENTURY

Michael Ponstingl

167

THE EMERGING PICTURELANGUAGE OF INDUSTRIAL CAPITALISM

Allan Sekula

179 WARBURG, PREMODERN MAGIC, PHOTOGRAPHY

Josh Ellenbogen

193

APPROACHES TO A PHOTOGRAPHY OF PAIN

Inés Plasencia

201

THE DILEMMA OF PHOTOGRAPHY: PHOTOJOURNALISM, HISTORY, AND THE PARIS COMMUNE

Paul Mellenthin

209

PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORDS OF THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONS: MYTHS AND DOCUMENTS

Erika Wolf

219

PHOTOGRAPHY OF REVOLUTIONS IN SPAIN (1854–1909)

Bernardo Riego

229

SOCIAL PHOTOGRAPHY: HOW THE CAMERA MAY HELP IN THE SOCIAL UPLIFT

Lewis Hine

237

ON SOCIAL PHOTOGRAPHY

Stephanie Schwartz

243 CONTRIBUTORS

250

LIST OF IMAGES

253

THE AESTHETIC OTHER: NOTES FOR A PROTOHISTORY OF THE DOCUMENTARY IDEA

JORGE RIBALTA

For the document functioned in a part of visual culture that had few aspirations to greatness or avant-garde revolution; it issued from the depths of bourgeois culture; it was the aesthetic Other.

—Molly Nesbit, Atget’s

Albums, 1992

With this research, the Museo Reina Sofía closes an extended study of documentary as an idea and a cultural form. It began in 2010 with A Hard, Merciless Light: e Worker Photography Movement, 1926–1939, an exhibition, seminar, and book project surveying the largely ignored worker photography experiments of the interwar period. It continued in 2015 with Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism, an exhibition and an anthology of essays attending to the rise of critical documentary practices in the “long seventies” (1972–1991). Next, in 2018, came a retrospective of the work of Marc Pataut: Marc Pataut: First Attempts. A coda to the previous studies, the retrospective considered the work Pataut had produced in the metropolitan area of Paris in the 1990s, at the time of the emergence of what has become known as the anti-globalization movement. Taking key decades in the history of twentieth-century photography as case studies, the series of exhibitions sought to o er an alternative political narrative for the rise and evolution of documentary practice.

91/

Seven

GUSTAVE LE GRAY (ATTRIBUTED) TAS DE PAVÉS (DETAIL), FROM ALBUM REGNAULT , CA. 1849–1855 (PILE OF COBBLESTONES)

Together, the three exhibitions provide a historical overview of the transformation of the idea of documentary. ey o er a history of the evolution of the subaltern voice implicit in documentary, from the mobilized industrial worker of the 1920s and 1930s to the urban, micropolitical struggles of the post -1968 period, ending with the emergence of the precariat in the 1990 s. Documentary Genealogies provides a di erent, albeit complementary, perspective. Imagining a protohistory of documentary in photography’s earliest period, it breaks with the chronological sequence of the previous exhibitions.

John Grierson’s “documentary idea” is reconsidered here. e ocial intellectual founder of documentary, Grierson placed documentary at the intersection of art, education, information, and persuasion. For the British lmmaker, cinema and photography’s hybrid, multiple, and minor artistic condition provided a ground for an art/nonart practice that displaced artistic autonomy into social life.1 us, in the 1920s, documentary constituted a counterdiscourse inside modernism. It emerged as much from a tension with and a resistance to modernist desires for autonomy as from the abstraction, with cubism onward, of everyday-life from the con icts of the social world. e functionalist and unstable nature of documentary implied an imperative of realism. Its historic mission was to represent the new political protagonist, the working class, in the era of mass democracy. Since then, documentary’s episteme has become constitutive of the speci c and contradictory status of photography inside of modernism.

In retrospect, it might be argued that photography’s documentary role is as old as photography itself, even though the rise of documentary as an artistic genre was a product of the 1920s. is, arguably, was what Walter Benjamin was suggesting in his 1935 essay “ e Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” when he re ected on the parallel emergence of photography and socialism. is project departs from Benjamin’s re ection by acknowledging that the iconographies of photography used in the 1920s to represent working-class life were latent in the visual culture of the 1840 s. e seminal, if accidental, gure of the bootblack in Boulevard du Temple (1838), one of Louis Daguerre’s rst plates, is a case in point. e daguerreotype can be seen not only as the rst photographic representation of labor but as a trigger for all subsequent historical accounts of class relations and con icts, or the crux of documentary practices that would emerge in the twentieth century.

This book maps a range of photographic practices inside what historian André Rouillé calls the “empire of photography.” This phrase designates photography’s rise as a new visual form in the midnineteenth century or the period coinciding with the Second Empire in France, as well as its status as a tool of empire, of the hegemonic

92/

1 Forsyth Hardy, ed., Grierson on Documentary (London: Collins, 1946).

bourgeois, industrial, and colonial cultural system. 2 Considering practices that developed inside and against the grain of “empire,” this history takes as its starting point the earliest depictions of subaltern subjects—servants, beggars, laborers; the unemployed, enslaved, imprisoned, sick, and so forth. It considers how they might stand as metaphors for Charles Baudelaire’s renowned and early condemnation—in his “Salon of 1859”—of photography as the “handmaiden” to the arts. Documentary is, thus, a minor art twice over. On the one hand, photography’s mechanical and instrumental nature makes it read as an impure art; on the other hand, its historical mission of representing the working class connotes an added degree of subalternity. Photography’s democratic promise went unful lled for more than a century, remaining the preserve of bourgeois culture. Portrayals of the lower class, subalterns, or proletarians remained marginal or accidental, gures appearing only incidentally in the periphery of frames focused elsewhere. Such images were made “from above,” rooted in the pious and paternalistic traditions of naturalism. is historic tour of the protohistory of the documentary idea starts with the oldest photographic images of revolution. ese date to the 1848 revolutions in Europe, the so-called Spring of the Peoples. Considered by contemporary historiography to be the moment the proletariat acquired class consciousness and workers’ political struggles began, this moment was not without its contradictions. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels published e Communist Manifesto in January 1848, declaring that the specter of communism was haunting Europe. eir claim gained substance a month later when protests in Paris sparked an uprising. But Marx himself viewed the events of 1848 in a critical light. In his 1852 e Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, he dismissed them as a parody of the 1789 French Revolution by remarking that the great events of history happen twice: rst as tragedy, then as farce.

Photographic records from the period of the 1848 revolutions are scarce; they amount to no more than a few daguerreotypes and calotypes depicting the Paris barricades and other scenes of political signi cance in London, Vienna, and Rome. But the photographs of Paris are most signi cant. ey are the rst examples of the kind of apocalyptic iconography that would become associated with popular uprisings. eir focus on urban chaos and the destruction wreaked by proletarian fury is a clear expression of bourgeoise fears of revolution.

A er this seminal moment, the historical narrative o ered in this interpretation takes an alternative approach to the “empire of photography.” It focuses on the production of photographic representations of what was deemed other to bourgeois culture inside some of its most iconic photographic enterprises.

93/

2

André Rouillé, L’empire de la photographie (Paris: Le Sycomore, 1982).

Molly Nesbit, Atget’s Seven Albums (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992), 9.

Two emblematic, dialectic impulses for such an “empire of photography” in Europe from the 1850s onward were the campaigns to record historical monuments, such as the Heliographic Mission in France, and those of urban center redevelopments, like that of Paris led by Georges-Eugène Haussmann. As new boulevards destroyed medieval cities, the rise of discourses on cultural heritage and antiquity became instrumental to the rise of nationalism. e decision to place photography in the service of preserving what was disappearing and publicizing what was emerging coincided with the medium’s rst great technological revolution: the combination of collodion negatives and albumen prints, which allowed for the photograph’s multiplicity. e organization of photographic archives and albums followed, and photography erupted into the public sphere. e Heliographic Mission of 1851 is a prime example of how the discourse of national historical monuments facilitated the narrative of the nation - state and fostered nationalist ideologies. is was not only a French trend; equivalent photographic campaigns took place in several countries. In Spain, Charles Cli ord was the pioneer. His photographic albums of Queen Isabella II’s travels around Spain constitute the rst photographic articulation of the nation based on the records of historical sites and monuments. But the bourgeois idea of nation, which is the impetus for such campaigns and albums, nds a dialectical counterpoint in the appearance of gures of alterity in the peripheries of the monuments: servants in palaces, gypsies at the Alhambra, small tradespeople, street beggars, and driers loitering in the street or in the architecture. ese gures represent the subaltern condition and constitute embodiments of what Antonio Gramsci referred to as the “national-popular.” Viewed, as Gramsci did, from below, the lower class and dispossessed were not, as bourgeois ideology would have it, survivors of “primitive” or premodern ways of life but the representatives of an alternative modernity. eir very presence resisted the “othering” discourse of liberal bourgeoise models of modernity, foreshadowing or re ecting the emergence of the proletariat as a political force and anticipating the class struggles that would de ne the ethos of documentary in the 1920s. As Molly Nesbit summarizes in her study of the albums of Eugène Atget, documentary issued from the depths of bourgeoise culture to represent its aesthetic Other.3

e second major trend driving the “empire of photography” was the spatial reorganization of urban centers according to the demands and logic of industrialization. The inner - city redevelopment campaigns of Paris, Vienna, Barcelona, and Madrid prompted photographic projects that both memorialized the old streets before they disappeared and celebrated the new avenues and urban infrastructure. Charles Marville’s record of Haussmann’s overhaul of Paris is perhaps

94/ 3

the quintessential example. Intentional or accidental, the rst iconography of the urban proletariat began to emerge around the same time. e earliest body of photographic work to take the working class as its subject is probably David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson’s study of a community of sherfolk in Newhaven, Scotland, a remarkable collection of calotypes produced around 1845 . In the 1850 s, Charles Négre in Paris and Giacomo Caneva in Rome photographed the urban and rural proletariat respectively. John omson photographed people on the streets of London in the 1870s and published his seminal book illustrated with woodburytypes, Street Life in London (1877 ). In the 1880 s, in New York, the sensationalist journalist Jacob Riis photographed working-class slums on the Lower East Side. He presented his photographs as lantern slides in public talks and later published them in the book How the Other Half Lives (1890). In 1904 , Hermann Drawe pursued a similar agenda in Vienna. He, too, presented photographs of the city’s underbelly, neighborhoods inhabited by the poor and vagrant, in public lantern- slide lectures, and he collaborated with the journalist Emil Kläger, whose work was also published in book form. e urban outskirts created by the tearing down of city walls at the turn of the century and the poor and subproletariat occupants of these terrains vagues were photographed by Atget in Paris, Heinrich Zille in Berlin, and Ferdinand Ritter von Staudenheim in Vienna.

Alongside photographic campaigns documenting national heritage and historic monuments, the “empire of photography” registered itself in another element that was part of the building of the modern nation-state: the great engineering and transport infrastructure projects of the mid-nineteenth century, such as railroads, aqueducts, and lighthouses. At the same time, photography began to be used to advertise new industrial products and factories. Universal and industrial exhibitions publicized this industrialization and were additional sites for the display of photography in the public sphere. e Great Exhibition of London in 1851 is a prime example. In Spain, Cli ord was again the pioneer, documenting major public works such as the Isabella II Canal, inaugurated in 1858 to solve Madrid’s water supply issues. Within this context, the rst images of factory work and of the workers themselves appeared. Studies of workers operating machinery at the Krupp steel works in Essen, taken in the 1890s, are probably the rst photographs of their kind and anticipate the iconography of men-at-work in industrial environments that proliferated in the twentieth century.

e great infrastructure projects o en relied on forced labor—an indication of just how much industrial capitalism prospered by radically exploiting the disempowered—and photographs of the great

95/

public works projects are similar to those made of workers in penal colonies. Chain-gang laborers working on public projects designed by the civil engineer Lucio del Valle, a trailblazer in Spain for having his projects photographically documented, can be seen in daguerreotypes from 1850. e incarcerated and the enslaved can also be seen in railroad construction photographs from the United States taken during the period of the Civil War by Matthew B. Brady, William Henry Jackson, and Timothy O’Sullivan. e rst images of miners working underground, captured by O’Sullivan using innovative articial lighting technology as part of his work for the 1868 Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel, bear witness to a hellish world. Another context to the “empire of photography” was the medium’s use of modern technologies of social discipline and governance. As a product of industrialization, photography formed part of the episteme of the natural and social sciences, and in this it helped to establish a new archival unconscious, a symptom of the hegemony of positivism. Photography’s use in geological exploration had an early golden age when great surveys of the US Western territories were commissioned in the late 1860 s, in the a ermath of the American Civil War. e rst of these was that of geologist Clarence King’s Fortieth Parallel survey, with O’Sullivan as the main photographer. e great body of photographic work in the form of albums produced by these surveys served a double purpose. On the one hand, they contributed to a discourse of nation -building by celebrating the heritage of North America’s sublime landscapes, leading to policies for the creation of national parks that claimed to preserve unique and emblematic natural environments; on the other hand, they were a tool for the control and exploitation of the land’s natural resources, of mining in particular. e Western surveys also testify to the decisive encounter between explorers or colonizers and natives. In this respect, the surveys can be also seen as one of the sources for the anthropological use of photography in the United States, which in the 1890s gave rise to wide-ranging documentation of Native Americans by pioneers such as Adam Clark Vroman and Edward S. Curtis. However, it was the work of Bronisław Malinowski and his collaborators on the Trobriand Islands around 1915 that cemented photography’s place in eldwork. A selection of photographs from this undertaking was published in 1922 as Argonauts of the Western Paci c, a seminal work of modern anthropology.

e surge in anthropology’s use of photography in the late nineteenth century happened in parallel with its increased deployment in the medical and judicial spheres. e American Civil War produced a remarkable range of anatomical photography, including compendiums of injuries, amputations, and deaths. In Europe, the French

96/

photographer Nadar participated in some of the photo-medical experiments of the 1860s, producing celebrated studies of hermaphroditism. But photography’s true pioneer in medical experimentation was the neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. His studies of so-called female hysteria and other neuropsychiatric pathologies, carried out in the 1870s at the Hospital de Pitié-Salpêtrière in Paris, were groundbreaking. His illustrated publications, which were published the following decade, had a huge in uence on modern neurology. ese experiments with photography parallel the early uses of photography in police and judicial work, including the rise of modern methods of photographic identi cation, such as those based on the studies of Alphonse Bertillon in France, Cesare Lombroso in Italy, and Francis Galton in England. In much the same way that medical photography is integral to normative discourses on health and pathology, police photography categorizes criminal and deviant personalities.

Such archival practices constitute photography’s disciplinary and repressive side. the counterpoint is the iconography of the urban chaos of popular uprisings, which brings us to the start of the nal episode in this protohistorical tour of the documentary idea: the Paris Commune. e political experiment in popular self-government that was the 1871 Paris Commune constituted a foundational and mythical moment in the political culture of the workers’ movement. It also produced the rst signi cant and widely distributed body of photographic work representing revolution. Growing from the seeds sown by the daguerreotypes of Parisian barricades in 1848, the photographs of the Paris Commune established a grammar for future depictions of revolution, even if the industrially produced and disseminated pictorial mass—in the form of albums, souvenirs, and an array of printed matter—was essentially counterrevolutionary. A catalog of the toppling of monuments, such as the Vendôme Column, and great institutional buildings being set ablaze, including the Paris Town Hall, underpinned a dystopian image of a city in ruins.

e same iconography of vandalism, trained on the chaotic and amorphous moments when a revolution or uprising was breaking out, would recur in depictions of the Russian revolutions of 1905 and 1917 and of Barcelona’s revolts from 1909. Known as the Semana Trágica (Tragic Week), the latter events also brought some of the rst images of the mobilized masses. ese disturbances all occurred at a time when the collotype was gaining ground and print media had begun to introduce photographs in place of sketched illustrations. Images of these events thus marked the birth of news photography and media sensationalism, all of which relied on the widespread circulation of images. In this respect the Tragic Week was a foundational moment for photojournalism in Spain. Images of barricades, religious buildings

97/

on re, and macabre scenes of mummies being turned out of the convents and put on public view appeared in the illustrated press of the time, heralded as eyewitness accounts in real time. e burned buildings later were featured in a collection of one hundred photographic postcards, Sucesos de Barcelona (Events of Barcelona), released in 1909 by the editor Àngel

Toldrà Viazo.

e iconography of revolutionary terror gained wide circulation, articulating early twentieth-century political antagonisms and social upper - class fears of the ascendent workers’ movement. Media was increasingly instrumental to the ruling class and to bourgeois culture. Images of the working classes tended to be paternalistic or criminalizing, a visual representation of the dominant ideology and of class con ict. e working class would not gain access and control of the means of representation and communication until much later in the 20th century—and only as a counterdiscourse to the bourgeois press. At the turn of the century, the photographic medium with the highest potential for widespread circulation was the collotype-based printed postcard, which proliferated in the 1890s in parallel with the rise of cinema as a public spectacle. e picture postcard was photography’s most-advanced form of public visibility until the arrival of mass photographic media at the time of the great revolution in modern visual culture in the 1920s.

Revolutionary uprisings and the organization of workers’ movements throughout the nineteenth century eventually led to advances in social rights and public policies, improvements in inner - city living conditions for the working classes, and the incorporation of those classes into nascent social and welfare states. e seminal example of the interaction between photographic practice and social policy— and a major contributor to the establishment of documentary as a genre—is Lewis Hine’s work for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). Founded in 1904, the committee was one of several state and parastate organizations that helped shape the development of public services and social welfare in the United States in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in response to growing demands by civil rights movements. Hine, who began to work with the NCLC around 1907 , was something of a mediator between the state and disadvantaged groups, championing reforms that would improve the lives of the most disempowered of workers: the children. Hine’s initiatives, positioned at the junction of art, politics, and education, were part of a wave of new social and popular education techniques in reformist policies proposed by academics from the emerging eld of sociology. Hine had a sociology background himself and argued that his mission as a documentary photographer was to highlight things that needed changing. His photographs of child laborers were widely circulated in

98/

the committee’s publications and in social studies magazines and literature. e NCLC organized itinerant awareness-raising exhibitions with Hine’s photographs displayed in panels alongside texts and diagrams. One image survives of such exhibitions; namely, of the NCLC pavilion at the 1915 Panama-Paci c International Exposition in San Francisco. e persuasive power of photography combined with text in an immersive exhibition space constituted a new paradigm and anticipated practices that would emerge in the late 1920s, such as El Lissitzky’s propaganda exhibitions and John Heart eld’s photomontages.

Hine was a photography professor at the Ethical Culture School in New York from 1904 to 1909, where one of his students was Paul Strand. Strand’s photographs mark the end point of this historical tour. e classic founder of photographic modernism, his work was in uenced by the reception of Parisian avant-garde painting a er the exhibition in New York of the work of Paul Cézanne and the cubists Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. Two portfolios of Strand’s work, published in successive issues of Alfred Stieglitz’s avant-garde magazine Camera Work, in 1916 and 1917, amount to something of a manifesto that anticipates photography’s future. Following Hine’s model of photography as a social practice, Strand became politically engaged in the 1930 s, when he became involved with the New York branch of the Worker’s Photography Movement, the Photo League. He presents a most complex gure, not without contradictions, especially his lurching from an o en-regressive aesthetic romanticism to a revolutionary ideology. But he is the link between an era that was ending and another that was about to begin, and he was to become both a symbol and symptom of the ambiguities between factuality and idealization that the documentary idea carried into twentieth-century photography.

99/

THE STREETS AND THE BARRICADES: DEMOS AND DOCUMENT IN NINETEENTHCENTURY PHOTOGRAPHY

Documentary politics is frequently associated with the 1930s: with America in Depression; with the alternative working - class civilizations in Weimar and Russia; with modernist vision and the Popular Front. But documentary practice did not emerge ab initio, rather it morphed out of the nineteenth-century conjuncture of undervalued pictorial genres and the depiction of subaltern subjects—the working class, colonial people, and unruly women. Some elements of this conjuncture are apparent in the odd picture made in 1847 by the English sculptor and daguerreotypist omas urlow (p. 9). Two things are unusual about this photograph, which is di cult to t within existing pictorial categories. Working wheeled vehicles are common enough in the history of art, but they are associated with the pastoral tradition of idyllic rural views, not with urban scenes. In contrast, urlow’s photograph is an ordinary picture of not very prosperous street life. e other signi cant feature is its awkward frontality. Donkey and cart are positioned diagonally to the picture plane, with di erential focus from front to back, creating a visual barrier; they block imaginative access to the space and direct the viewer’s attention to the dirty-faced boy who stares back, meeting our gaze. It is an awkward, plain, and everyday picture.

101/

STEVE EDWARDS

HIPPOLYTE BAYARD RUE ROYALE ET RESTES DES BARRICADES DE 1848 (DETAIL), 1848 (RUE ROYALE AND THE REMAINS OF THE BARRICADES OF 1848)

1

Frederick Engels, e Condition of the English Working Class in 1844 (1845), in Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, Collected Works 1844–1845, vol. 4 (London: Lawrence and Wishart, 1975).

2

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: e Birth of the Prison (London: Penguin, 1979); and Foucault, e History of Sexuality, vol. 1 (London: Penguin, 1981). For the emergence of “examination” and “inquiry,” see Foucault, “Truth and Juridical Forms” (1973), in Power: Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984, ed. James D. Faubion (London: Penguin, 2000), 1–89. For dossier making, see Michel Foucault, ed., I, Pierre Rivière Having Slaughtered My Mother, My Sister and My Brother . . .: A Case of Parricide in the 19th Century (London: Penguin, 1978), x–xi; and S.D. Chrostowska, “‘A Case, an A air, an Event’ ( e Dossier by Michel Foucault),” Clio: A Journal of Literature, History and the Philosophy of History

35, no. 3 (2006): 329–49. For photographic history based on Foucault’s work, see, in addition to Sekula, John Tagg, e Burden of Representation: Essays on Photographies and Histories (New York: Macmillan, 1988); David Green, “A Map of Depravity,” Ten.8, no. 18 (1985): 36–43; David Green, “On Foucault: Disciplinary Power and Photography,” Camerawork

32 (1985): 6–9; and David Green, “Veins of Resemblance: Photography and Eugenics,” in Photography/Politics Two, ed. Patricia Holland, Jo Spence, and Simon Watney (London: Comedia; Photography Workshop, 1986), 9–21.

Henri Lefebvre, e

Production of Space (London: Blackwell, 1991), 28.

DOCUMENTS

Capitalist industrialization and urbanization produced new forms of social investigation during the nineteenth century: government reports explored social conditions; journalists wrote firsthand accounts of life in the poor districts; statistical societies collected data on poverty; and novelists such as Eugène Sue, Charles Dickens, and Elizabeth Gaskell cra ed ction where the working poor interacted with the middle class. None are neutral or objective, all involve staging images of class, whether to manage fear and fascination or to advocate radical change, as did Friedrich Engels.1 From the mid-century, photographic documents were combined with these forms of social investigation to reveal, identify, and classify subaltern subjects. New techniques of biopolitical governance turned on visibility and transparency, quanti cation and individuation. 2 is is a transparency “under whose reign everything can be taken in by a single glance from the mental eye which illuminates whatever it contemplates.” 3 at is, it is a detached view, seemingly from nowhere. In his justly acclaimed essay “ e Body and the Archive,” Allan Sekula suggests that, alongside André Rouillé’s “empire” of middle - class portraits, we should pay attention to a “shadow archive” containing pictures of “the poor, the diseased, the insane, the criminal, the nonwhite, the female, and all other embodiments of the unworthy.” 4 Writers on photography have increasingly studied this repressive archive, but even those who have done so have paid little attention to the form of these instrumental documents. Photographs produced from within this ideological purview were o en combined with written statistics and, just as important, stored on cards in ling systems, creating dossiers or case histories. In Discipline and Punish Michel Foucault writes, “‘ e examination,’ surrounded by all its documentary techniques, makes each individual a ‘case’: a case which at one and the same time constitutes an object for a branch of knowledge and a hold for a branch of power.”5 e case le, he continues, brings into view the “individual as he may be described, judged, measured, compared with others, in his very individuality.” 6 According to Foucault, the writing and constructing of cases played an important role in the development of governmental techniques. Photographic documents contributed to these case les.7 Across multiple facets of society, from policing and sanitation reform to colonial administration, making and interpreting pictorial documents helped to consolidate middle-class expertise.

Case photographs can be found in individualizing (Bertillon) and typifying (Galton) variants, 8 and they appear in the records of the police and charitable organizations, medical establishments,

102/

3

and in colonial albums of racist “ethnic types” of the sort made by Carl Dammann, John Forbes Watson, and John William Kaye (e.g., e People of India: A Series of Photographic Illustrations, with Descriptive Letterpress, of the Races and Tribes of Hindustan). As it emerged, the photographic document prized clarity above all else. Subjects were positioned centrally within the frame and fully illuminated, eliminating patches of shadowy obscurity. ese pictures are frontal and unembellished, with the lm plane parallel to the axis of the subject. Documents are plain and seemingly without style; they appear to be merely technical pictures. In her outstanding study of Eugène Atget and the photographic document, Molly Nesbit characterizes the document as a low-plane form of vision that constitutes the “base line” of visual culture, a mere “point of departure” for other practices. It was, she said, so ubiquitous and workaday that it was almost invisible: mere “optical dust.” 9 e document form is a rhetorical construction of artlessness where observers lay claim to an “objectivity” rooted in the absence of any evident markers of subjective investment.10 Documents are seemingly all function and hardly noticeable as a pictorial style, but the document is the “cell form” of documentary.11

ON THE STREET

In the latter part of the nineteenth century a related vision of social transparency was extended to exploration of the social “lower depths” with pictures by omas Annan, Jacob Riis, Hermann Drawe, and a host of other middle-class men with cameras. In the earliest forms of photography, “images of the ‘unworthy’” are rare, and pictures of people at work by W.H.F. Talbot or Robert Adamson and David Octavius Hill draw on the tradition of genre painting, particularly seventeenth - century Dutch scenes of everyday life. e same can be said for the slightly later images by Charles Nègre and Giacomo Caneva. These are conventional pictures with workers at ease in harmonious rural settings. e photographs Samuel Bourne made in India situate human gures in landscapes inspired by English aesthetic ideas. is should not be surprising; photographers adopted available pictorial languages and forms to their purposes.

Among the earliest images, Louis Daguerre’s picture Boulevard du Temple (pp. 86–87) stands out. Taken from a high vantage point, this may well be the rst photograph of labor, yet the bootblack working at the man’s feet is paradoxically invisible. e slow exposures of this period made it impossible to capture motion. In Daguerre’s picture, a gentleman has remained static long enough to register, but the

4 Allan Sekula, “ e Body and the Archive,” October, no. 39 (1986): 7, 10

5 Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 191; emphasis in original.

6 Foucault, Discipline and Punish, 191

7 Steve Edwards, “Making a Case: Daguerreotypes,” British Art Studies, no. 18 (2020), https://dx.doi .org/10 17658/issn.2058-5462/ issue-18/sedwards.

8

Alphonse Bertillon was a Parisian police o cer who pioneered the use of photographs, both portraits and details of the body, to identify criminals. Francis Galton made superimposed images from multiple negatives in which he believed the essence of a type was revealed.

9

Nesbit, Atget’s Seven Albums, 16.

10

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity (New York: Zone Books, 2007).

11

Karl Marx describes the commodity as the “cell-form” of capitalism. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, vol. 1 (London: Penguin, 1976), 90.

103/

12

Allan Sekula, “An Eternal Esthetics of Laborious Gestures,” in Art Isn’t Fair: Further Essays on the Tra c in Photographs and Related Media, ed. Sally Stein and Ina Steiner (London: MACK, 2020), 159–60

13

Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism (London: Verso, 1983); and David Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity (London: Routledge, 2006).

bootblack working at his feet appears as a blur. Sekula argues that this image embodies the fetishism of commodities in a society where labor is systematically occluded.12

As the major cities of the Western world underwent unprecedented growth and transformation during the nineteenth century, many more photographs were taken to document urban transformation: the building of elite shopping areas along with large- scale engineering works such as the new sewerage and underground transport systems, railways, roads, and docks. All this construction depended on human muscle power, yet the laboring gure is largely absent from such pictures. Since the work of Walter Benjamin, Paris is o en viewed as paradigmatic of this transformation, and Charles Marville is the photographer most closely associated with the work, under the dictatorship of Napoleon III, that turned Paris into a pleasure ground for middle-class consumption. Beginning in 1854, construction teams directed by Georges-Eugène Haussmann began to demolish the old Paris, replacing it with parks, squares, and eighty kilometers of planned, radial avenues.13 e old, ramshackle streets were torn down, clearing the way for the construction of grand boulevards with straight lines and regular, imposing facades. In the process, workers were displaced from dwellings in the center of the city to its fringes. e city that emerged was composed of striking vistas and, as Benjamin observed, conduits for rapid troop movements. Marville documented these changes with before - and - a er pictures (p. 17 , fig. 1 ). Typically, his images employ exaggerated perspective to create sight lines emphasizing ordered grandeur. In these images the tens of thousands of workers involved in this monumentalizing labor are nowhere to be seen; it is as if the city built itself with Haussmann in the starring role of the sorcerer’s apprentice. Photographs by Marville that do depict the labor of construction employ an engineer’s vision, recording the sites of building with working men posed at rest. In the technical language of art, these gures are “sta age,” providing a sense of scale for the promethean feats of the engineer and introducing variety into the scene. Workers may be visible in such images, but they remain inert and incidental—the visual equivalent to the anecdote.

In photographs by Nègre, Joseph Kordysch, and John ompson, working people appear as picturesque “types,” but before the later decades of the century “sta age” was the most typical pictorial mode for these working gures. Scenes of engineering and construction— often taken from a high vantage point, which gives a controlling sense of possession—sometimes include such gures posed for scale. In these pictures what matters is the magnitude of the construction, with the feats of human endeavor attributed to the engineer or

104/

entrepreneur. Charles Cli ord’s photographs of the Canal de Isabel II are good examples. In a variant, Robert Howlett’s picture of the SS Great Eastern as the immense ship was under construction at the John Scott Russell shipyard on the Isle of Dogs, London, focuses attention on the middle-class engineer, with the working shipbuilders pushed to the edges of the frame and beyond the zone of focus. In Nadar’s pictures of work underground, human laborers are literally replaced with mannequins. When the camera leaves the street for the workshop or factory, the scene is equally devoid of human presence, with the apparatus of production at rest, suggesting order and calm or the wonder of “self - acting” machines; the workforce would be mere visual clutter.

In the 1880 s and 1890 s, new types of photographic pictures began to take shape, with portraits of work groups and even people engaged in work, such as the images in the present exhibition taken by the unknown photographer of the Krupp factory in Essen, Germany (pp. 32, 37 ). Annan, Drawe, and Riis depicted cramped and unsanitary living conditions, people posed in alleyways and courtyards, and children sleeping outdoors. ese images have overwhelmingly been treated negatively by historians as extensions of the

105/

Fig. 1 CHARLES MARVILLE PERCEMENT DE L’AVENUE DE L’OPÉRA: CHANTIER DE LA BUTTE DES MOULINS DU PASSAGE MOLIÈRE , 1858–1878 (BUILDING OF AVENUE DE L’OPERA, BUILDING SITE OF THE MOUND OF MOULINS NEAR PASSAGE MOLIÈRE)

14

John Roberts, Photography and Its Violations (New York: Columbia University Press, 2014).

15

Rouillé’s L’empire de la photographie 1839

1870 (Paris: Le Sycomore, 1982) is con ned to the Second Empire, while his compendium of texts, La photographie en France: Textes et controverses: Une anthologie, 1816–1871 (Paris: Macula, 1989), ends with an image of the massacred Communards.

16

Adrian Ri in, Snapshots Forever, episode 2, “Barricade,” produced by David Perry, BBC Radio 3, July 1991

17

For barricades, see Mark Traugott, Insurgent Barricade (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2010); Eric Hazan, A History of the Barricade (London: Verso, 2015); and Jean-Marie Mayeur and Alain Corbin, eds., La barricade (Paris: Éditions de la Sorbonne, 2016).

disciplinary vision described by Foucault and Sekula. We are told that the photographers stripped agency from the working poor and exposed them to the reforming agendas of the middle class, almost as if they were Nadar’s mannequins. The argument has many elements of truth, but it is too unequivocal, closing interpretation and xing meaning with univocal interpretation. With the new evidentiary form of picture, subaltern subjects emerge into visibility. e evidentiary mode points and highlights. As John Roberts argues, it is “ostensive”; it says, “pay attention to this” and “attend to these people’s lives”—but, as anyone who works with historical or legal evidence knows, documents require interpretation.14 e popular TV forensic-crime genre typically ends with an arrest or confession, because in court things are never so simple once experts begin disputing evidence and suggesting alternate explanations. e evidentiary mode, out of which documentary congealed, puts into play conditions of subaltern visibility, but it cannot x in advance the ways they will be understood. In calling attention to poverty and degradation, in making subalterns an object of attention, the evidentiary images of the later nineteenth century played a part in establishing class as the terrain on which politics would have to be elaborated. By the time Riis made Chinatown, Smoking Opium in a Joint around 1890 (p. 162) or August Stauda took 19., Heiligenstädter Straße 119 —Hofansicht around 1904 (p. 171 ), something approximating documentary vision was coming into focus.

BARRICADE

Rouillé punctuates his L’empire de la photographie ( e empire of photography) with the event of the Paris Commune of 1871 and images of the barricades.15 But earlier, with the revolutions in France and Chartism in England, another kind of photography had been consolidated. In the rst instance, this was not a deliberate strategy adopted by politically conscious makers but a conjuncture or collision of overlooked subjects and plain or “anti-aesthetic” visual forms. Against this politics of transparency and overview we can contrast the barricade, both literal and symbolic.

As Adrian Ri in observed, from 1848 to 1871 “Paris was a city where the barricade and photography grew up together.”16 As much as it is a defensive forti cation of neighborhood or zone, the barricade proclaims a politics of space. 17 Leon Trotsky argues in his book 1905 that barricades are as much “moral” structures as defensive barriers, bringing the people into contact with the troops. Mark Traugott observes in a detailed study of the history of the barricade

106/

–

that the process of their construction, by consolidating forces of opposition, may be more significant than the military role they play.18 Barricades are choke points against the logistical circulation of people and commodities, blocking space and thwarting transparency. As symbolic markers of workers’ antagonism to the rule of capital, barricades de ne neighborhoods as sites of opposition; they are metonyms for insurgency and machines for producing the revolutionary people.19

Barricades scar and deface the grand metropolitan thoroughfares of idleness and consumption, casting temporary and makeshi structures against permanent architecture, irregularity against symmetry, mass against facade, and a leveling horizontality against phallic verticality. e photographs of barricades reveal a working-class encampment, or occupation of enemy territory.20 e vernacular handiwork of workers, these barricades impose a point of view that is frontal and confrontational: separating us and them, above and below. e optical perspective of the camera enhances this feature, so it matters whether the barricade is seen from a distance or up close and from which side it is photographed. In the terms set out by Marxist philosopher and urban theorist Henri Lefebvre, barricade photographs contrast counter - space to the abstract space of capital (perceived space).21 Abstract space, according to Lefebvre, condenses relations of capital, particularly nance capital, subordinating use to “phallicvisual - geometric space.” 22 Barricade pictures deface this obscene facade of space and power.

I 1848

Only a handful of photographs were made of the barricades in Paris in 1848 . e technical di culties were real, but perhaps the middle class did not want to see a challenge to its rule. CharlesFrançois ibault created daguerreotypes of the barricades on rue Saint-Maur Popincourt on June 25 and 26 (pp. 2–3). Located in an artisan faubourg, dense with small workshops (a sign on a building in these photographs reads, “large and small workshops for rent”), the photographs depict the site of one of the bloodiest clashes in June between the troops of General Lamoricière and the workers attempting to defend the social gains of February, including the National Workshops that had provided employment in the crisis year of 1848 for 117,000. Made from a high vantage point, the pictures present distant views of the informal architecture of insurgency. Photographic technology would become more adept at recording such scenes, but, with a slow exposure, the rst image is largely unpopulated, though a blurred group can be made out to the right. In

18

Leon Trotsky, 1905 (London: Penguin, 1972), 411; and Traugott, Insurgent Barricade

19

Traverso cites Alain Corbin to this e ect. See Enzo Traverso, Revolution. An Intellectual History (New York and London: Verso, 2021), 191.

20

Kristin Ross, e Emergence of Social Space: Rimbaud and the Paris Commune (New York: Macmillan, 1988), 42

21

Lefebvre, e Production of Space

22

Lefebvre, e Production of Space, 289. For nance capital and the production of space, see Harvey, Paris, Capital of Modernity.

107/

23

Olivier Ihl, “In the Eye of e Daguerreotype: On the Rue du Faubourg-du-Temple in June 1848,” preprint, August 2018, https://doi.org/10.13140 /RG.2.2.16383.25765. Originally published as “Dans l’œil du daguerréotype : La rue du Faubourg-du-Temple, juin 1848,” Études photographiques 34 (Spring 2016), https:// journals.openedition.org /etudesphotographiques/3597

24

For a recent treatment of this and related images by Bayard that contains a great deal of historical detail, see Margaret Fields Denton, “Traces of History: Hippolyte Bayard’s Photographs of the 1848 Revolution,” Getty Research Journal, no. 15 (2022): 43–66. In an apparent variant of this picture, made shortly a erward or beforehand, the cart and horses occupy other positions.

25

As Denton observes, at the same time Bayard also made a photograph of the Bibliothèque du Louvre, the former royal palace renamed the “palace of the people,” carefully framing the doorway to render visible the inscription on the lintel of the window: “Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité.” A er the coup of Napoleon III at the end of 1851, the slogan was replaced with the word Imperial Denton, “Traces of History,” 60

26

Lefebvre, e Production of Space, 41, 273.

the second image, taken a er the defeat of the insurgents, troops and shopkeepers mingle, and the fuzzy gures are put to good use, suggesting the bustling return of commerce and order known as “normality.” Olivier Ihl shows that ibault was a landowner and president of the “club fraternel du Faubourg du Temple,” which supported the aims of the February revolution but rejected the more radical worker politics.23 e perspective on the scene is indicative of this political view; it is detached and keeps a safe distance from events, much as an uninvolved observer might do. In these pictures elevation implies social hierarchy. ibault’s photographs—symmetrical, frontal, and detached—are in some ways characteristic of the document form, and yet the barricade intercedes and disrupts the politics of the overview.

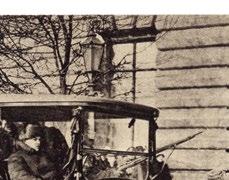

The paper photograph of a partially dismantled barricade on rue Royale, taken by Hippolyte Bayard, employee of the Ministry of Finance, is more complex and more interesting (p. 4 ). 24 It, too, is a picture of political restoration, but here the scene is down- toearth and replete with revolutionary history. e backdrop at the end of the avenue is the grand site of bourgeois sociability, the Place de la Concorde. is kind of abstract space functions as a stage for the performance of bourgeois displays of fashion and decorum, for promenading, looking at others, and being seen. During the French Revolution it was renamed the Place de la Révolution and was the site of the execution of Louis XVI, Marie Antionette, and later of Maximilien Robespierre. Renamed for Louis XV and then Louis XVI a er the Restoration, it become the Place de la Concorde in the wake of the revolution of 1830, but during 1848 it was once more called Place de la Révolution. e rue Royale, site of this barricade, had also been renamed rue de la Révolution. In February the street had been the site of one of the earliest confrontations of the revolution, with attempts to erect barricades. With this image, Bayard presented a view on revolutionary history.25

For Lefebvre, facade and vanishing point are important in the abstract space of capital, creating a “logic of visualization” or a monumental vista.26 Abstract space, which occludes social relations, contains a logic of transparency that eliminates obstacles to apprehension. Rue Royale is marked by the remnants of a barricade and the remains of a canon (or possibly a cart). At its right edge is a newly planted “liberty tree,” a symbol of popular sovereignty with connections to the French Revolution and the founding of the Republic. Often decorated with revolutionary insignia such as the bonnet rouge, liberty trees were planted with great ceremony in 1848. In 1850, the year that three million workers were stripped of the vote, the government conducted a program of uprooting these trees. One reason for this war against nature was that the trees were said to obstruct

108/

vistas and interfere with the “harmony of public squares and monuments.”27 e ecocidal practitioners of deforestation were right: the liberty trees, with their roots in the earth, interjected a sign of life into this deathly, abstract space. In Bayard’s photograph the spindly saplings break the scene of overblown regularity with the mark of festivity.

Barrows and a cart suggest the point at which the strewn rubble of a defeated insurrection is being cleared away, while the carriages parked along the street indicate the return of social immobility. is scene of the removal of the barricade provides a symbolic erasure of opposition, wiping out any traces that might remind people another world is possible. Bayard comes down to street level and positions his camera closer to the barricade than ibault, yet the railing in the foreground provides a de nite barrier to the viewer, imaginatively barring him or her from the space. Perhaps, the anthropomorphic gas lamp—an eye and a camera—on the other side of the fence stands as a solitary defender of the barricade, a reminder of insurrectionary desire. Bayard made another picture from a similar point of view, conceivably a er the eradication of these signs of revolutionary action, and in 1850 he returned once more to photograph the crowds celebrating the proclamation of the Republic. No longer distanced or external, in this picture the camera allows access to the space and the crowd, now inviting the viewer to join them. Michael Löwy sees the earlier barricade photograph as a “melancholic image” that replaces “the insurgent’s utopian dream” with “piles of scattered stones.”28 But the image is more dialectical than this description suggests. Since much of the picture presents signs of restoration, its meanings cannot easily be xed, and for any subsequent viewer the barricade and liberty tree may carry the charge of a suspended moment of freedom. Photographs exist between then and now.

In this regard, Gustave Le Gray’s salt print Tas de pavés (Pile of cobblestones) of 1849 (p. 1), while it may not show a barricade (it might be an image of construction materials), is wonderfully evocative, calling to mind the recent events of 1848. In this image, stacked paving stones—the building blocks of barricades—are depicted with absolute frontality, in close-up, and they seem to extend beyond the edges of the frame, confronting the bourgeois viewer with the very image of insurgency. is shadow, or a erimage, distils the characteristics of the barricade photograph, conjuring proximity, confrontation, and fear; it may be the most compelling image of the year of European revolutions.

En route to the Middle East in 1860 , Le Gray stopped in Sicily, where he photographed the traces of the nationalist insurgency against the Bourbon occupation. In Palermo, led by General

109/

27 Q

in Denton,

55 28

9.

uoted

“Traces of History,”

Michael

Löwy, ed., Revolutions (London: Haymarket, 2021),

Giuseppe Garibaldi, approximately 750 Redshirts and three thousand picciotti (Sicilian volunteers), joined by residents and freed prisoners, confronted forces that were numerically vastly superior, including battalions of mercenaries. Ultimately, twenty- two thousand Bourbon forces surrendered. Le Gray made several images of the con ict, including a portrait of Garibaldi. Most of the photographs reprise features seen in images made by ibault and Bayard, with barricades in the middle ground, photographed from a suitably distant height, with a shadowy human presence ( g. 2). But one picture foregoes the transparent overview and returns to the point of view of Tas de pavés, situating the camera (and viewer) close up and

110/

Fig. 2

GUSTAVE LE GRAY (SOMETIMES ATTRIBUTED TO ALEXANDRE FERRIER) BARRICADE OF INSURGENTS IN PALERMO, 1860

directly behind the barricade, looking over the cannons down a narrow street onto a public square. No distant overviews or blockages to access here; this is the viewpoint of the barricades’ defenders. Perhaps the sympathy felt by a middle-class public for the cause of the nationalists allowed for this di erent kind of view.

II. e Commune

By the time of the Paris Commune of 1871, photographic technology had been improved to the point where many more photographs could be made depicting partisans of the Universal Republic. ey range from portraits of significant participants to images depicting the destruction of that phallic monument to the victors, the Vendôme Column; and from scenes of destruction resulting from the fighting to the morbid curios of slaughtered Communards numbered and arranged in their co ns. Here I consider only photographs of barricades, which appear almost as obscenities or vulgar curses that besmirch the polite architectural and spatial order.29 During the defense of the Commune, some nine hundred barricades were erected. Many were informal and rapidly constructed, but they also included the large and elaborate structure at the corner of Place de la Concorde and rue de Rivoli known as “Château-Gaillard” a er Director General of Barricades Napoléon Gaillard, who was a shoemaker, author of a treatise on the foot, and inventor of rubber galoshes.

Whereas the photographs of barricades in 1848 exclude workingclass bodies, with images of the Commune the protagonists enter the scene. Inserted into abstract space, they are their own liberty trees. In some pictures, Communards pose in federal uniform; in others, groups are positioned irregularly, creating group portraits of workers pleased with their handiwork and their new society. In the photographs of the elaborate structure at rue Royale ( gs. 3–4), Gaillard appears proudly before his creation: in the frontal image he sits to the right; in the more diagonal one he is the second gure from the le . Ross and Ri in observe that Gaillard in this way “signed” the barricade a er the fashion of an artist signing a painting.30 At a time when a photograph would cost a worker a month’s wages, this was probably the rst time these men had had their portraits taken. e barricade allowed them to enter history, emerging from what the critic Siegfried Kracauer calls “the abyss of imageless oblivion.”31 A few weeks later that visibility might turn into a death sentence when identi cation with the Commune resulted in thousands of summary executions and thirty thousand dead.32 But in the sixty-two days of the Commune, workers went from invisibility, mere sta age or visual

29

As Kristin Ross observes, Commune was a bloody word that spread fear among the middle class. Ross, e Emergence of Social Space, 150

30

Ross, e Emergence of Social Space, 18. On two occasions, Ross cites Ri in to this e ect, but I have been unable to nd the source (it must have been from a private exchange). Traverso similarly notes, “Standing before the camera lens, the revolution’s protagonists literally turned themselves into actors in the ‘theater’ of History.” Enzo Traverso, “ e German Revolution: 1918–1919,” in Revolutions, 214

31

Siegfried Kracauer, e Salaried Masses: Duty and Distraction in Weimar Germany (London: Verso, 1998), 94

32

Prosper-Olivier Lissagaray, History of the Paris Commune of 1871 (London: Verso, 2012).

111/

112/

incident, to the central actors in the upheaval, replacing engineers with top hats. As we know from Plato, shoemakers are supposed to know their place and “stick to their last.”33 Instead, Gaillard erected barricades and broke down social barriers.

In these photographs, two forms of architecture, invoking two kinds of civilization, are juxtaposed. Inserted among the monumental classical facades, the barricades and bodies assert another use of space. Ross notes that Château - Gaillard “reached a height of two stories and was complete with bastions, gable steps, and a façade anked with pavilions.”34 Despite the elaborate structure, within the imperial space this proletarian construction was, like its makers, low, horizontal, and vernacular. In the photographs, the barricade screens the grand architecture, denying the bourgeois spectator an uninterrupted view of triumphal splendor and grandiosity. Here order, regularity, and symmetry take on quite di erent connotations. ese pictures of barricades, which are also pictures as barricades, announce that shoemakers and other workers can creatively reorder space even as they build their universal republic.

e barricade photographs reject high vantage points, and the insurgent construction blocks o the space, defacing monumental and symmetrical vistas, obstructing the transparent (phallic) gaze.