4 minute read

by Edouard A. Stackpole

A Night in the Ice Fields on B o a rd S t e a m e r N a n t u c k e t

IN THE PRESENT era of marine transportation whenever a "freezeup" has prevented the motor vessels leaving or entering the harbor there is the excellent alternative of travel by airplane. But, early in this century such was not the case — the steamboat was the only link with the mainland when heavy ice prevented the use of other craft.

Many unusual happenings occurred during the winter months of embargo by ice fields, and one of these took place in February, 1905, when passengers hoping to leave the island had an unique experience. The last days of January were cold and breezy, and the ice had formed to a thickness keeping the boat in port. Monday, Jan. 31 brought some hope of a break-out as a snow-storm in the early morning was succeeded by rain and a southeasterly wind, and the ice fields outside the jetties moved out into the Sound. But a change developed during the afternoon and evening, with the wind backing into the northwest and the temperature dropping rapidly. Feb. 1 found the ice embargo again in place, and the next day was a duplicate weather-wise.

Thursday, Feb. 3, came in with a mild trend, with the wind again settling in the southeast and some snow and rain falling. Seams appearing in the ice between Brant Point and the jetties promised further hope, and Captain Furber decided to attempt to break out of theTiarbor on the following morning, Feb. 4, and shortly after daybreak the sidewheel steamer Nantucket got under way from the wharf.

At this time there were only five passengers who had to decided to brave the trip—Cromwell G. Macy, of New York, James Phillips of Providence, a Mr. Brush, of Boston, and two young men whose names have not been ascertained. Captain Furber knew that on the other side of the Sound there were Nantucketers anxious to get home and a week's collection of mail, newspapers, and provisions—ready to be loaded.

The troubles began for the steamer as she approached Brant Point. After two hours of bucking the heavy ice the Nantucket managed to round the Point but then began to encounter even thicker ice, piled up by the tides. The hours passed, with only a few feet of progress. Between 3 o'clock that afternoon, and 5 o'clock the steamer managed to reach the passage between the two jetties, where she at last reached an impassable stretch and was held fast.

After a few hours of watching the steamer edge her way through the ice the passengers passed the time as best they could. All manner of means were used to amuse themselves. Several kinds of games were played; cards were at first enjoyed and then finally abandoned; stories of their experiences provided a few hours of entertainment; accounts of books, plays, sports and festivals became a last resort.

One of the passengers, Cromwell G. Macy, wrote of his experience: "Some time after the sun had gone down behind Tuckernuck, Captain Furber, in whom the company maintained unquestioning confidence, apportioned the short supply of staterooms among his involuntary guests, and all hands prepared for a night just beyond the harbor lights. The restless vigilance of the captain, however, soon discovered that the ice was parting and that the boat was about to sail to some unseen land. The steamer's officers thereupon put her in gala trim, with her electric lamps lighted, and the search-light cast over the ice to the jetty end to the surprise of the belated coot and the circling gull. In excursion apparel the officers by tireless efforts, way towards morning, succeeded in maintaining a favorable berth until the sun, looking over Sankaty Head, found our little community snugly locked in the drift ice just within the western jetty."

All through that night the N a n t u c k e t remained in the grip of the ice fields, being carried to and fro just off the jetties, unable to free herself, entirely controlled by the tidal flow of the heavy ice. In this perilous situation Captain Furber spent a sleepless night, with regular consultation with his officers and chief engineer.

At daybreak, a seam in the ice enabled Captain Furber to make a turn, and an hour later he was headed for the channel leading back into the harbor. Slowly but surely the Nantucket forced her way toward Brant Point, to reenter the inner harbor and regain her berth at Steamboat Wharf at 1:30 o'clock Saturday afternoon, February 5. Captain Furber received the highest praise for his judgment by both passengers and crew. He had previously stated that if he did not attempt the break-out it would be a long time before the Nantucket would make her way to Woods Hole.

Captain Furber's observation proved only too true. During the next three weeks the steamer remained at her berth, and the ice embargo continued until February 25, when the Nantucket finally was able to make a trip across the Sound. In the interim, the Revenue Cutter Mackinac steamed around to the east end of the island, landing passengers, mail and provisions at Quidnet, at last breaking one of the longest freeze-ups on record. „jr \ §

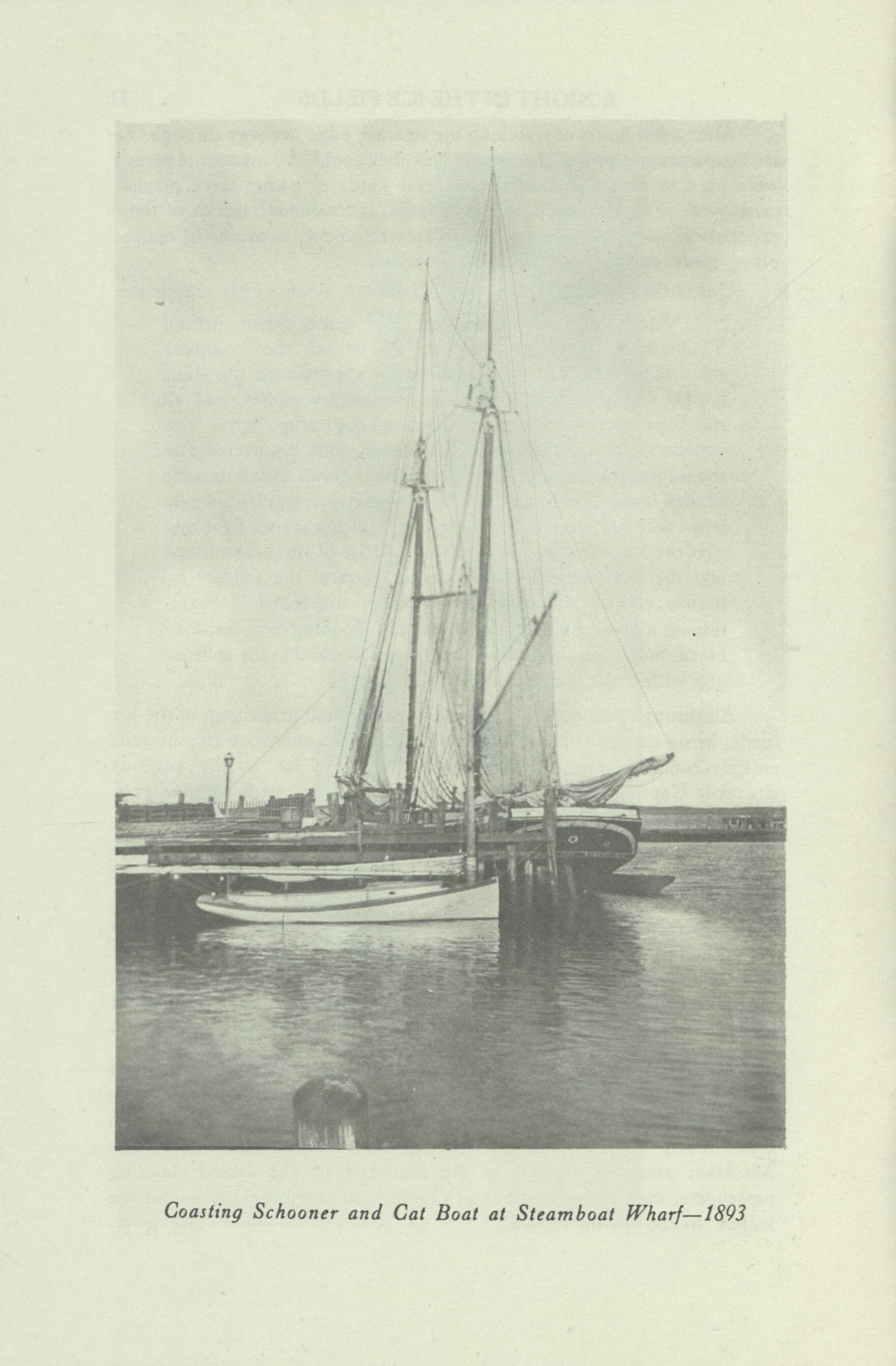

Coasting Schooner and Cat Boat at Steamboat Wharf—1893