22 minute read

by Andre Aubuchon

A u g u sta B u n k e r P i o n e e r S c h o o lte a ch e r a n d R a n c h e r

by Andre Aubuchon

IF, AS MONTESQUIEU believed, climate shapes character and institutions, how much stronger the force of geography and history. The influences of these forces can be observed in no better an environment than that of Nantucket, which had to turn to whaling for its survival. For a century, Nantucket was one of the leading whaling ports of the world, and it was Nantucketers who prosecuted the most difficult and demanding aspects of the industry: Pacific whaling and the pursuit of the sperm whale. The whale fishery in turn required courage. Skilled tradesmen, able seamen, keen businessmen, and proficient masters were all necessary for the success of the enterprise, but without courage whaling was bound to fail. Stories of Nantucket captains keeping mutinous crews at bay with armed pistols, of unbearded Nantucket youths meeting after surviving massacres in the South Pacific, of Nantucket vessels resisting pirates, privateers, and enraged "natives" are common and for good reason: without this courage Nantucket could never have led the world in whaling.

If geography encouraged Nantucketers to turn to whaling, it also required Nantucketers to emigrate. The food supply and economic resources of the island have at best always been limited, and, unfortunately, insufficient to maintain an ever-increasing population. Sons and daughters of each successive generation of Nantucketers have been forced to leave the island. Not all have, like some hardy adventurers, established themselves as merchants and mariners in such far flung corners as Hawaii, Australia, or the western ports of South America. Neither have most emigrating Nantucketers shared in the adventure of serving as whaling "colonists" in Nova Scotia in the 1760's and 1780's, Hudson, New York, in the 1780's, Milford Haven, Wales, in the same period, and Dunkirk, France, on the eve of the Revolution of 1789. The experience of most Nantucket emigrants has been a bit more prosaic: solid citizens, they found their way to the offices and counting houses of mercantile Boston and New York, the factories of Providence and New Bedford, the farms of the South and Midwest, and the mines of California.

If emigration has not attracted the attention it has deserved from Nantucket's historians, this is especially true of one particular species of

AUGUSTA BUNKER 7

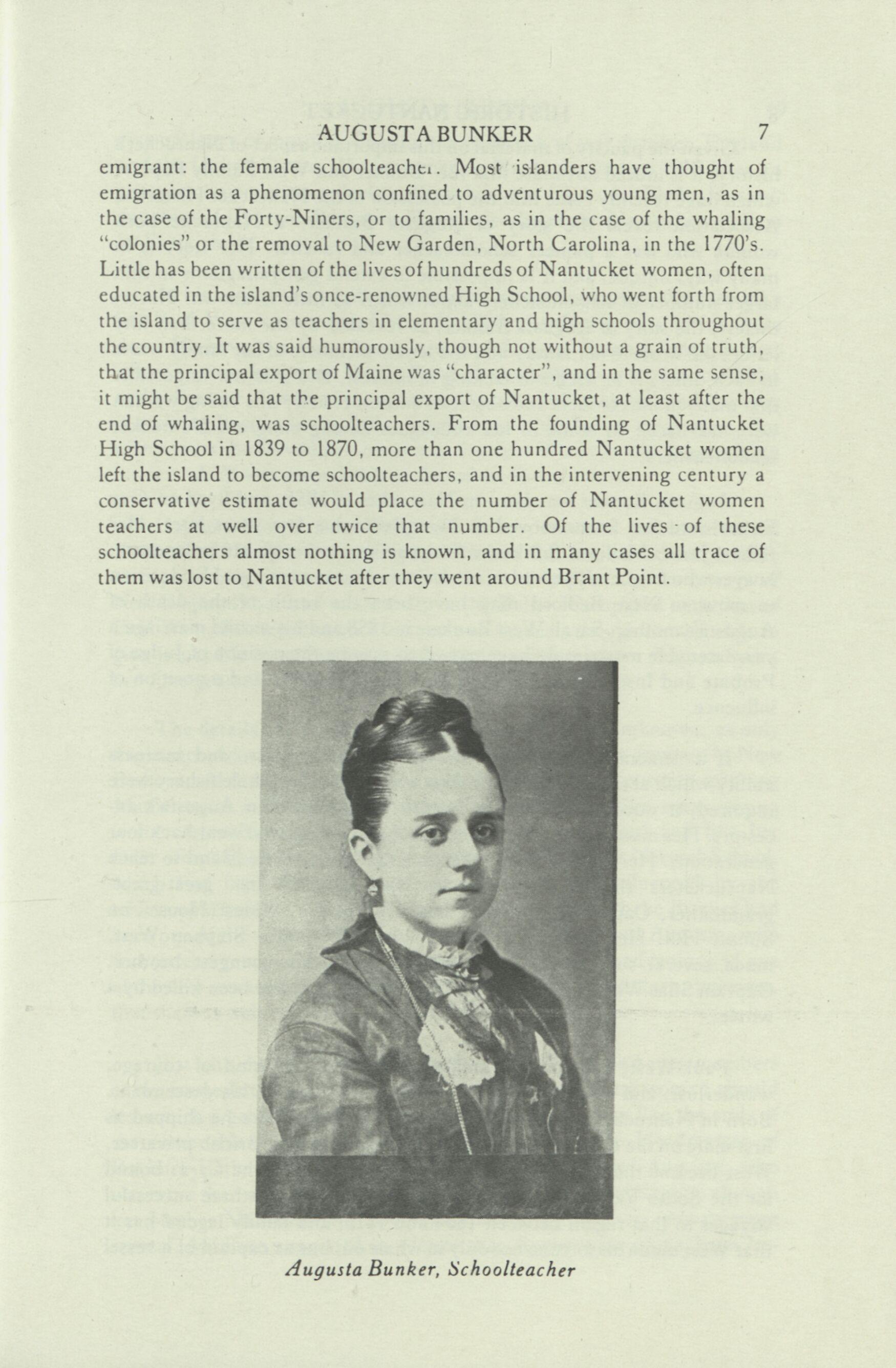

emigrant: the female schoolteachti. Most islanders have thought of emigration as a phenomenon confined to adventurous young men, as in the case of the Forty-Niners, or to families, as in the case of the whaling "colonies" or the removal to New Garden, North Carolina, in the 1770's. Little has been written of the lives of hundreds of Nantucket women, often educated in the island's once-renowned High School, who went forth from the island to serve as teachers in elementary and high schools throughout the country. It was said humorously, though not without a grain of truth, that the principal export of Maine was "character", and in the same sense, it might be said that the principal export of Nantucket, at least after the end of whaling, was schoolteachers. From the founding of Nantucket High School in 1839 to 1870, more than one hundred Nantucket women left the island to become schoolteachers, and in the intervening century a conservative estimate would place the number of Nantucket women teachers at well over twice that number. Of the lives - of these schoolteachers almost nothing is known, and in many cases all trace of them was lost to Nantucket after they went around Brant Point.

8 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

Given the paucity of material on this important aspect of Nantucket's history, it is indeed fortunate that the "Bunker and West Family Papers" which have recently come into the possession of the Nantucket Historical Association reveal the story of Augusta Bunker, a Nantucket-born woman who was a pioneer schoolteacher and rancher. Her story is in many ways unique, and it is impossible to extend generalizations to that larger number of schoolteachers about which so little is known. Nevertheless, the story of Augusta Bunker, as revealed by the more than fifty letters she wrote to her family and the letters members of her family wrote to each other, is in itself not lacking in interest, and it is not impossible that many of the conflicts and obstacles encountered by this young woman were also faced by some of her colleagues among emigrant Nantucket schoolteachers.

Augusta Bunker was born in Nantucket in 1855, and lived on Gay Street until her father moved to New Bedford a few years later. Her father, James Madison Bunker, was a prominent, though not prosperous, lawyer who frequently served as moderator of town meetings. His decision to move to New Bedford may have been the result of the death of Augusta's mother, Sarah West Bunker, in 1858 and his second marriage a year later. He may simply have moved to assume the position of Judge of Probate and Insolvency which offered a steady income and a position of influence.

If a demonstration of the courage, resourcefulness, and business ability which accounted for Nantucket's success in the whale fishery were required, it would be necessary to look no further than Augusta's ancestors. Her maternal ancestors were whaling masters who went back four generations. Her earliest Nantucket ancestor came to the island to teach Nantucketers the art of on-shore whaling, and her great-greatgrandfather, Captain Paul West, had lived in the "Oldest House" on Sunset Hill. Her grandfather's older brother Captain Stephen West, made several successful whaling voyages, and his youngest brother, Captain Silas West, was one of few Nantucketers to have been killed by a whale.

Paul West, Augusta's grandfather, showed the kind of courage, wanderlust, and love of adventure which was evident in his descendant. Born in Nantucket, he made his way to Dunkirk, where he shipped as first mate on the Cyrus. When the Cyrus was taken by a British privateer, West became the Captain. In 1804, he left London on the Cyrus bound for the South Pacific by way of Cape Horn. He made three successful voyages to that region between 1804 and 1812, and family legend has it that West made his fortune not only in whale oil, but as captain of a vessel

given a letter of marque. Fearing the outbreak of war between England and the United States, West returned to Nantucket in late 1812 after an absence of more than a decade. With him was his bride, Phebe Hussey, daughter of Captain Benjamin Hussey, leader of the Nantucket whalers in Dunkirk.

In his career as a whaling master, or as a privateer, as the case may be, Paul West accumulated over $60,000, a princely fortune for those days. He bought a large house, still standing, at Seven Liberty Street, where he was close to the Pacific Bank of which he was a large stockholder and a director. A man of energy as well as of wealth, he invested not only ingrowing Boston banks and railroads but in Nantucket enterprises. For many years, he served as treasurer of Straight Wharf in which he held an interest which was second only to that of the Rotch Family.

Captain West's older daughter, Sarah, married James Madison Bunker in 1835. His father, Captain Reuben Bunker, served successfully as captain of a packet boat which had not only plied the waterways of New England, but had made a trip to the Baltic. Compared with that of Paul West, Reuben Bunker's fortune was modest, though he was able to give James Madison Bunker a house on Gay Street where Augusta spent her first years.

The details of Augusta's childhood and youth are unknown, as only fragments of correspondence survive. It is known that she grew up in New Bedford and that she attended college before obtaining a position teaching Mathematics at Stetson High School in Randolph. Like many young women from Nantucket and Southeastern Massachusetts and like her older sister, Phebe, she may have attended Bridgewater Normal School, which had been founded to educate teachers and influenced by the educational leaders, Horace Mann and Cyrus Peirce. Phebe Bunker had been one of the early students at Vassar in the 1860's, and Augusta, who was sixteen years younger than Phebe, may have taken advantage of one of the new women's colleges like Vassar or Smith. It is known, however, that she was well-educated and qualified as a teacher.

Just why she left Randolph is open to speculation, and even members of her immediate family were puzzled as to why a young woman should leave such a good position to go to what could only seem like the ends of the earth. Her brothers, Paul and Alfred (later the Headmaster of Roxbury Latin School), and her sister, Phebe, regarded Augusta, who was more than a decade younger than they, with fond indulgence, though her brother Madison, only two years older than she, was always more critical. Madison suggested in a letter that Augusta may have been im-

pelled to leave by an unhappy "love affair". Whether he meant to imply that a suitor had jilted her, or that she had rejected a suitor cannot be determined, though it must be noted that Madison's suggestion is worthy of consideration. Of Augusta's siblings, he knew his sister from the closest perspective. It must also be kept in mind, however, that Madison's attitudes were "unenlightened" by contemporary standards, and that most men would explain any unexplainable aspect of the behavior of a female by reference to a female's relation to males.

Perhaps it is unnecessary to look further than the historical and hereditary influences on Augusta Bunker. Any young woman whose maternal grandfather had made three voyages from London to the Pacific whaling grounds, or whose paternal grandfather had sailed in European waters, was not likely to regard a transcontinental journey as a fearful undertaking. If Augusta's brothers and sister could not understand her motives for heading for the Pacific Northwest, Augusta could not understand their puzzlement. Perhaps she was a bit disdainful of kin who had not seen fit to leave New England.

Phebe West Bunker, Elder Sister

AUGUSTA BUNKER 11

The first letter from Augusta to Phebe was written from Merced, California, 152 miles from San Francisco. It was dated March 23, 1882, a little less than three weeks after her twenty-seventh birthday. In that letter she described her travels on the transcontinental railroad in company with Mr. Felch who was to escort her to Cheyney, Washington Territory, where she had been engaged to teach at the local academy. In the letter she commiserated with travelers forced to cross the Arizona Desert in the summer, and noted that even in March, "The sand and dust were terrible and I do feel so dirty that I shall be only too glad to leave the train at San Francisco and have a room wh(ere) to make myself comfortable." Nevertheless, the mountains and valleys, the fertile farm land, and the mild climate of California were sufficiently impressive after winter's cold and desert's heat to make California seem like "Paradise on Earth". Los Angeles, then an unspoiled and clean town, was especially beautiful as the Spring flowers were in full bloom.

There was little time for taking in the scenery, and less time for writing East, and the next letter to Phebe was dated July 19. Augusta had already made her way to Cheyney, and had left for Spokane Falls, the largest town in Eastern Washington. By that date, she had become an accomplished horsewoman and the week before, she had taken four ten mile rides. September 4th, the opening of Cheyney Academy found her boarding with the widow of a minister. Life in a small house next to the general store was different from what Augusta had known back East, but she was beginning to make the acquaintance of the little more than one hundred inhabitants of the town. "Miss Bunker," Augusta wrote to Phebe, "is a lonesome title when no other is used," but she was happy to report that her landlady had taken to calling her "Augusta".

School and community presented problems to the moralistic newcomer from New England. While there were thirty-nine desks, there were more than sixty students, and many of these were older, less apt, and more likely to misbehave than the docile children she had taught. In several letters, Augusta made known her pointed opposition to serving as a missionary, and she "positively declined" to take a Sunday School class. Her background inclined her to decry the eight saloons in Cheyney, and to wish that the Principal, Mr. Felch, would wash more frequently and more thoroughly. Nevertheless, she seemed to be adjusting though she could not help but observe to Phebe that Cheyney Academy was "a kind of school that no money would have persuaded me to teach (in the) East."

Cheyney was undeniably a pioneer town with unfinished houses and even rougher characters, and Augusta was by temperament and determination a pioneer. The letters to her New England family talked of

12 HISTORIC NANTUCKET

extreme temperatures—110 degrees in tne summer and forty below in tne winter—but they also tell of her transformation. In the Fall of 1882, her letters were filled with details of homesteading: she had bought 160 acres five miles from town, and in five years she would obtain clear title to the land and cabin. Her letters were so filled with plans and diagrams of houses and land to make her brother Madison complain to Phebe. It could not be doubted that Augusta was capable of handling her homestead and her class of over-age roughnecks, and that a more enthusiastic young woman could be found anywhere west of the Rockies. Before Augusta had been in school for a month, her landlady had unwittingly prophesied that she would not remain a schoolteacher, "but that ranching will be more profitable in money and health..."

The ensuing year and a half in Cheyney passed quickly, and if the town was quiet, there was no lack of work at school and on the farm. Augusta's only complaints were of numerous colds and sore throats, and of chronic over-work at Cheyney Academy where three teachers did work which required twice their number. In April, 1883, Augusta wrote of teaching an extra class, and of having to give up the strenuous work of playing the organ and singing in the local church. At times, she worked too hard and in January, 1884, she complained in a letter to Phebe that hoodlums in her class were smoking and using profanity. In the next letter, she remarked that she was "almost an inveterate coffee drinker now", surely not an easy confession for a young lady with a proper New England background.

If Eastern Washington Territory provided little by way of amusement and intellectual pursuits, it developed in Augusta Bunker a love for farming and the land. During the winter she boarded with respectable women in Cheyney. but at the end of school she headed for her 160 acre homestead, horseback riding and vegetable farming. Letters to New England in the Spring and Summer of 1883 delight in details and drawings of plans of the homestead and cottage. Vacations offered Augusta the opportunity for attendance at teachers' institutes at Spokane and Walla Walla, though Cheyney offered some social life to an eligible young lady. She "saw" several young business men and professional men in addition to the male teachers and clergymen at Cheyney Academy. A spirited young lady, Augusta was not above deflating a conceited young lawyer from Massachusetts: it seemed that this gentleman assumed that no "Westerner" was good enough for a lady who had beheld Boston.

This life of arduous schoolwork, church and social activities, and farming was brought to an unexpected halt in March, 1884, when the authorities at Cheyney Academy failed to rehire her for the Spring Term.

AUGUSTA BUNKER 13

There was no question of misconduct or of incompetence, as all of her superiors offered to write recommendations and two of the trustees wrote of their regret at her dismissal. That the situation surrounding her dismissal was suspicious cannot be denied: she was not informed by letter of the decision and it was not until she returned from a visit to Spokane that she was told—by her landlady!—that she had not been rehired.

It is unfortunate that the only explanation of Augusta's dismissal has come from her own hand. She explained in a letter to Phebe that the sister-in-law of a trustee had been appointed in her place, but it is not certain that nepotism was the only cause of her dismissal. The official letter, written after the dismissal, referred to Augusta's ill health, and extended wishes for a speedy recovery. It might be said in criticism of Augusta that she may well have been a difficult and fractious colleague: in her letter to Phebe, she constantly criticized almost all of the authorities and teachers at the school, and she spoke most disparagingly of Cheyney, its school, teachers, and pupils. It may have been that the "Easterner's" criticism was not sufficiently disguised.

The six months following Augusta's dismissal were completely lacking in the hope and high spirits so evident in her first two years in Washington Territory. The letters show a dark side to her character: Augusta gloated that the woman who had been brought from the East as her replacement broke down after a day and a half in the classroom. Moving between Cheyney and Spokane, Augusta was unable to obtain several situations which had interested her. By June, 1884, the young woman who had almost never mentioned her family and home "back East" suffered from an acute case of homesickness. Either Augusta was so overcome by defeat and depression, that she was unable to write, or what letters she had written have not survived, but there are no letters between June 14 and September 5.

The months of the Autumn of 1884 proved to be the test of Augusta's courage and resolution, and she survived a wiser, if not unscathed, young lady. In her letter of September 5, Augusta observed that "to come from Boston is no recommendation here." She had been unable to find a position, and wrote now of coming home. To leave Washington would be to admit defeat, and though it is certain that her aunt Phebe Ann West in Nantucket had ample resources to fund a return to New England, Augusta decided to stay. A month later, she wrote again of returning East and, as a compromise, suggested she might spend the winter with friends in Minneapolis. Leaving Washington would involve Augusta's relinquishing her homestead, so she settled instead for a visit to a Mrs. Fee, the sister-in-law of one of her landladies.

By November 4, Augusta's life had taken what could only be described as an abrupt change for the better. In her visit to the Fees in Lewiston, Idaho Territory, Augusta had met, fell in love with, and become engaged to marry Walter Fee, the son of her host and a rancher in Nez Perce County. Together with his brother-in-law, Walter Fee owned a ranch which produced wheat, feed, and beef cattle. Augusta was decidely taken with Walter and with the life of a rancher. She noted approvingly that Walter was a good Christian—and parenthetically, that his father was a Christian minister—and that he had "character", which was especially necessary in the rough-and-tumble, rugged West. By way of explanation to kin "back East", she added that Walter's brother-in-law was a "Maine man", no doubt a high recommendation to her New England family.

Augusta's first year on a ranch located several miles outside of Waha, Idaho, provided more excitement than had the several years in Cheynev. In this period, she learned how to be a rancher's wife, and perhaps even a rancher herself. The usual diagrams were sent to Phebe and her brothers and the letters were filled with descriptions of rescuing cattle from floods, bringing cattle to town, haying, and harvesting the wheat. The traditional wifely duties of cooking and keeping house were not neglected, especially not in harvest time when Augusta and her sister-in-law had to cook for "from fourteen to eighteen (ranch-hands) for three days... For these men we have to seek one end, that is to give them enough to eat."

In the summer, Augusta picked and canned green gooseberries, currents and red raspberries. There were jam and jellies to put up for the winter, and in that season there was sausage to be made—140 lbs. to be exact! Augusta's menus show that she learned to cook in a New England kitchen, and such Nantucket staples as baked beans and indian pudding were frequently on the table.

With only three other people on an isolated ranch, life was lonely but informal dinner parties with neighboring ranchers and occasional visits to Walter's parents in Lewiston, the nearest large town, provided diversions from the harsh realities of life on the frontier. There were newspapers and magazines from the East for amusement on winter evenings, and Augusta's letters indicate that she not only subscribed to the Inquirer and Mirror, but that it was read carefully. Waha, Idaho, was not New England, however, and when Augusta was occasionally left alone on the ranch, she had a rifle and dog to protect her against the desperados who roamed the countryside. Law and order was constantly threatened, but it surprised even long-time residents of Nez Perce County when two neighbors, both successful ranchers and respectable men, killed each other in a quarrel.

Augusta seemed to love Idaho for its-flaws and failures as well as for its strengths. Her feelings about the territory and her ranch were to some degree strengthened by her devotion to her husband. Comments Augusta made to Phebe suggest that Walter Fee was not a handsome man: "The artist (i.e. photographer) is not a good one, and his pictures all have a hard look." Earlier she described him as bald and fair-complexioned, and in another letter she suggested that Walter was not as stern as his photograph had made him seem.

What made Walter attractive to Augusta was his sobriety, consideration, and Christian piety. Of the last, Augusta wrote on several occasions: "... how I thank God that my husband is a Christian and that I'm not deprived of human sympathy in my own ways of thinking." For Walter's abstinence from alcoholic beverages Augusta was especially thankful, as she was aware of the severity and frequency of drunkenness in the West. Not only Walter, but his sister and brother-in-law were teetotalers even to the extent of not sharing Augusta's "vice" of coffee drinking. Of Walter's consideration, one incident bore effective testimony: when Augusta and Georgia Dyer were in Lewiston, their husbands kept the house immaculate.

It could only have been with great joy and keen anticipation that in the late summer or early autumn of 1885, Walter and Augusta looked forward to the birth of their first child. Despite occasional colds and sore throats, Augusta had enjoyed good health since going West. Nothing indicated that she would have any trouble bearing a child, and the occasional complaints of pain and illness found in her letters to Phebe throughout the fall of 1885 were not unusual in healthy women. By December 3, she could comment to her sister that: "I am beginning to show my size... I will tell you before long that you may speak of my condition."

If Walter and Augusta had doubts about the desirability of her "condition", they were probably reassured by news that Georgia Dyer had given birth to a nine-pound son. Their delight in the birth of a nephew and interest in his growth was evident in Augusta's letters. The Fee Family was cautious, and arrangements were made for Augusta to stay with Walter's parents in Lewiston, where physicians were within reach. On April 18, 1886, Augusta, still at the ranch, felt that the time was near and with a cake in the oven, penned a note to Phebe noting "All are well and busy."

In the next several days, complications developed, and Augusta was moved to Lewiston where she was attended by two physicians and nursed

by her mother-in-law. By April 19, it had become apparent that Augusta's infant had died, and it was necessary for physicians to perform surgery to remove the fetus. After an illness of several days, Augusta died peacefully in her sleep. Her last words were spoken to console her husband, and she gently remarked to her mother-in-law: "I can't undertake worship." She observed: "The Lord is very near to me," and fell into a sleep from which she did not awaken.

Augusta's death did not sever the ties between the family of her husband and her relatives in New England. Walter and his mother kept up a correspondence with Phebe West Bunker in Bradford, Massachusetts, and with Augusta's aunt, Phebe Ann West of Liberty Street, Nantucket. In October, 1889, Walter Fee visited Phebe Ann West in Nantucket, and in a subsequent letter remarked that he would like to visit Nantucket again.

What an Idaho rancher in his mid-thirties and a Nantucket spinster of advanced years discussed cannot be known with certainty, but the conversation most likely turned to Augusta Bunker Fee. Each had known "Gusta" in a different season of her life: Aunt Phebe Ann had known her as an infant in Nantucket, and Walter as a pretty and strong-minded schoolteacher and pioneer in the West. The three years intervening between Augusta's death and Walter's Nantucket visit had undoubtedly assuaged the loss, and it may have been that he was able to understand from the conversation of the daughter of that adventurous whaling master, Paul West,what had motivated Augusta to leave her family and home in New England.

Phebe West Bunker received many letters of sympathy from relatives and friends. Perhaps the most fitting eulogy of Augusta Bunker Fee was written by her in 1882, the year in which she went West: "Yet death is inevitable and one after another passes on, and yet the world moves on." Captains Paul West and Reuben Bunker would have understood their granddaughter.

Dr. Andre Aubuchon is the Archivist working at the Peter Foulger Museum, where he is cataloguing the Manuscript Collections of the Nantucket Historical Association.