5 minute read

by Helen Wilson Sherman

19

A Whaling Man's Needlework

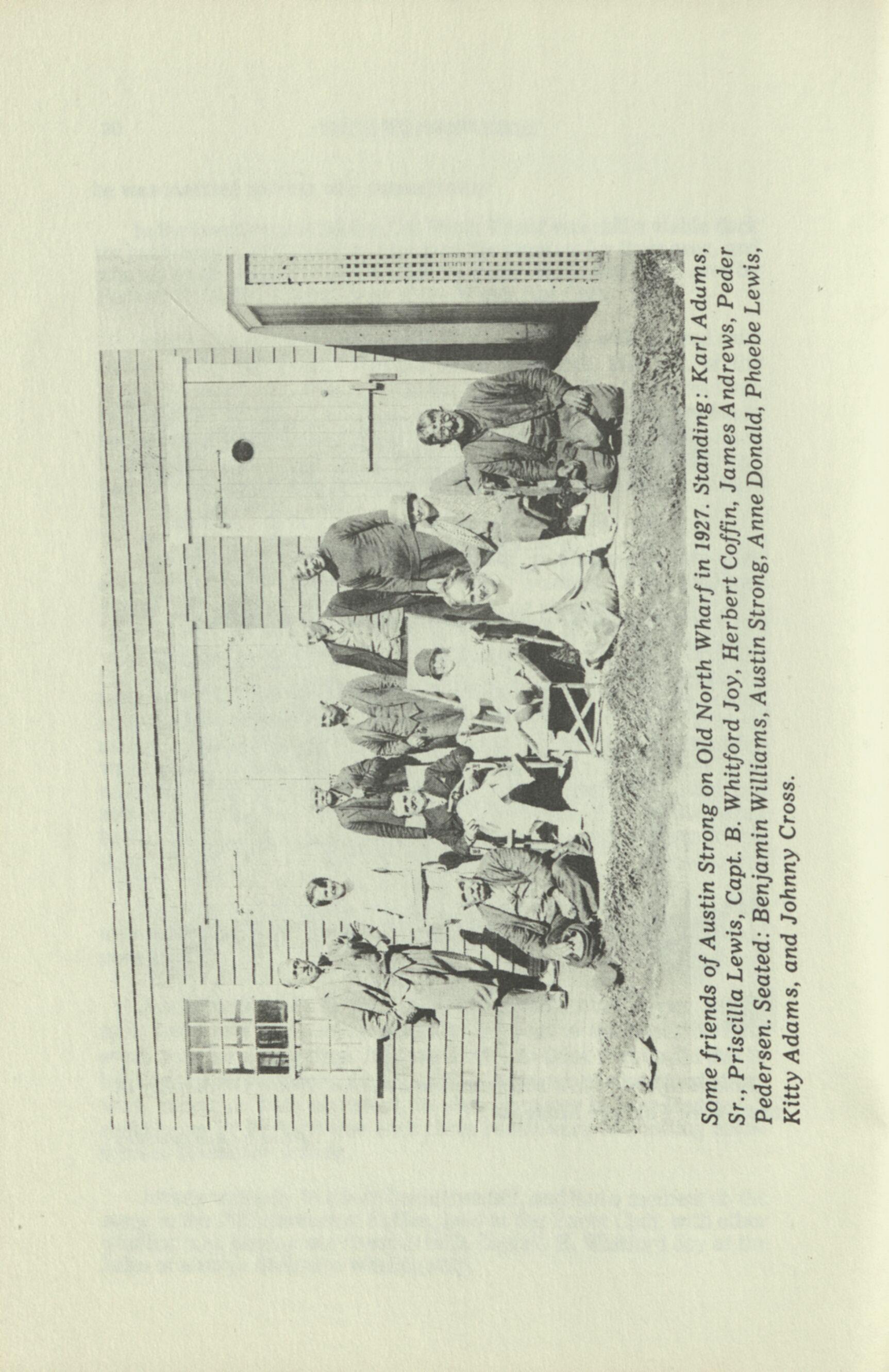

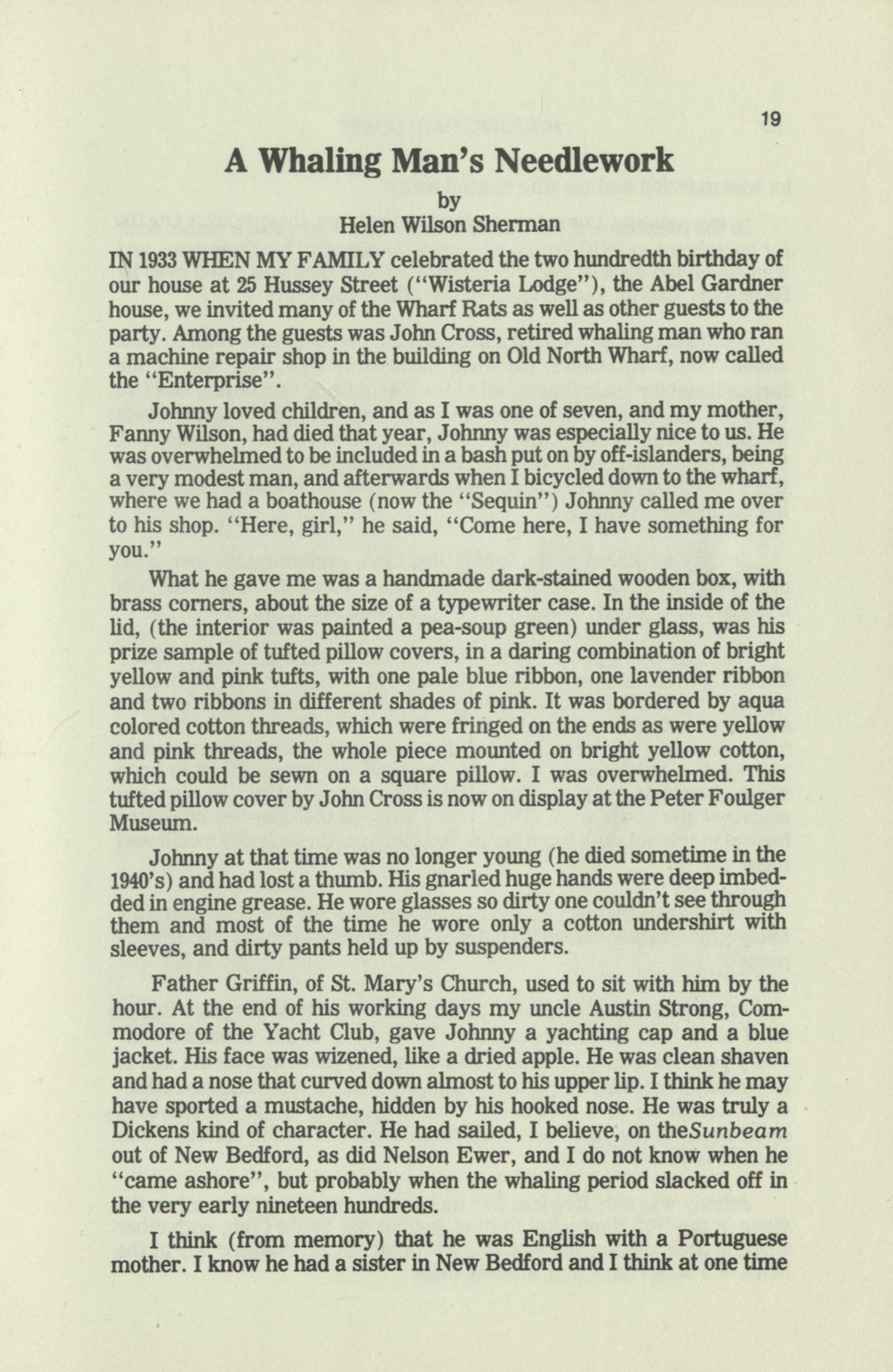

by Helen Wilson Sherman IN 1933 WHEN MY FAMILY celebrated the two hundredth birthday of our house at 25 Hussey Street ("Wisteria Lodge"), the Abel Gardner house, we invited many of the Wharf Rats as well as other guests to the party. Among the guests was John Cross, retired whaling man who ran a machine repair shop in the building on Old North Wharf, now called the "Enterprise".

Johnny loved children, and as I was one of seven, and my mother, Fanny Wilson, had died that year, Johnny was especially nice to us. He was overwhelmed to be included in a bash put on by off-islanders, being a very modest man, and afterwards when I bicycled down to the wharf, where we had a boathouse (now the "Sequin") Johnny called me over to his shop. "Here, girl," he said, "Come here, I have something for you."

What he gave me was a handmade dark-stained wooden box, with brass corners, about the size of a typewriter case. In the inside of the lid, (the interior was painted a pea-soup green) under glass, was his prize sample of tufted pillow covers, in a daring combination of bright yellow and pink tufts, with one pale blue ribbon, one lavender ribbon and two ribbons in different shades of pink. It was bordered by aqua colored cotton threads, which were fringed on the ends as were yellow and pink threads, the whole piece mounted on bright yellow cotton, which could be sewn on a square pillow. I was overwhelmed. This tufted pillow cover by John Cross is now on display at the Peter Foulger Museum.

Johnny at that time was no longer young (he died sometime in the 1940's) and had lost a thumb. His gnarled huge hands were deep imbedded in engine grease. He wore glasses so dirty one couldn't see through them and most of the time he wore only a cotton undershirt with sleeves, and dirty pants held up by suspenders.

Father Griffin, of St. Mary's Church, used to sit with him by the hour. At the end of his working days my uncle Austin Strong, Commodore of the Yacht Club, gave Johnny a yachting cap and a blue jacket. His face was wizened, like a dried apple. He was clean shaven and had a nose that curved down almost to his upper lip. I think he may have sported a mustache, hidden by his hooked nose. He was truly a Dickens kind of character. He had sailed, I believe, on theSunbeam out of New Bedford, as did Nelson Ewer, and I do not know when he "came ashore", but probably when the whaling period slacked off in the very early nineteen hundreds.

I think (from memory) that he was English with a Portuguese mother. I know he had a sister in New Bedford and I think at one time

20

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

he was married and his wife passed away.

In the twenties and thirties Old North Wharf was still a viable dock for partyboats and fishermen who used the shanties for their gear, and who sat on the deck of Perry & Coffin's store, which was ruled over by Herbert H. Coffin, Commodore of the Wharf Rat Club.

Austin Strong introduced a little fleet of catboats with colored sails called "Baby Rainbows" because there were five, still left, of the larger Rainbow boats that raced at the Yacht Club. Our family had two Baby Rainbows, the Kittiwake, and the Emerald, and Johnny Cross hauled them out of the water every September when we had to go back to Providence to school. We would come to him for slight repairs, and there was always a circle of sailing children around Johnny's shop having something fixed.

Johnny never sat at the Wharf Rat Club, preferring his own huge open doorway where he'd sit when he wasn't working. On one side was a huge fishnet which he said was for catching sturgeon.

He made orange sodapop and bottled it, storing it in a high loft near the hot ceiling, and we were always hearing "bangs" when the bottles blew up. He also made fish chowder into which he put whole fish, scales and all, laced with dried celery he hung overhead. He had a tiny kitchen and everything in it was black with smoke and grease. The chowder was always on the stove in a huge pot and we were enticed to have some. I suppose my mother would have shrieked at the dirt but somehow the bowls were clean, and I enjoyed the chowder but hated having to spit out scales and bones and fish lips. He probably swallowed them all.

He told me that he made the pillow covers for the Brockton Fair every year, and took them up in the wooden box, which has since disappeared.

Johnny's ideas of colors for these shams were totally gypsy. But he must have sold them successfully for he went to the Brockton Fair every year for a long time. It is rather nice to think that he did this to help some poor members of his family, as he never left the island otherwise, except on rare occasions, to visit his sister in New Bedford. I could never understand how such clean needlework and tufting came from so blackened a shop.

Johnny was only five feet five inches tall, and had a moment on the stage in the 1929 Nantucket Follies, held at the Yacht Club, with other whaling men singing sea chanties with Captain B. Whitford Joy at the helm of a stage deck of a whaling ship.

P a s t e l t u f t e d p i l l o w s h a m , m a d e b y J o h n C r o s s . O n d i s p l a y a t t h e P e t e r F o u l g e r M u s e u m .

Photo by Rob Benchley

m i m u m