13 minute read

his Granddaughter Diane Taylor Brown

Nantucket, Far Away and Long Ago

by Joseph Warren Phinney and his Granddaughter Diana Taylor Brown

23

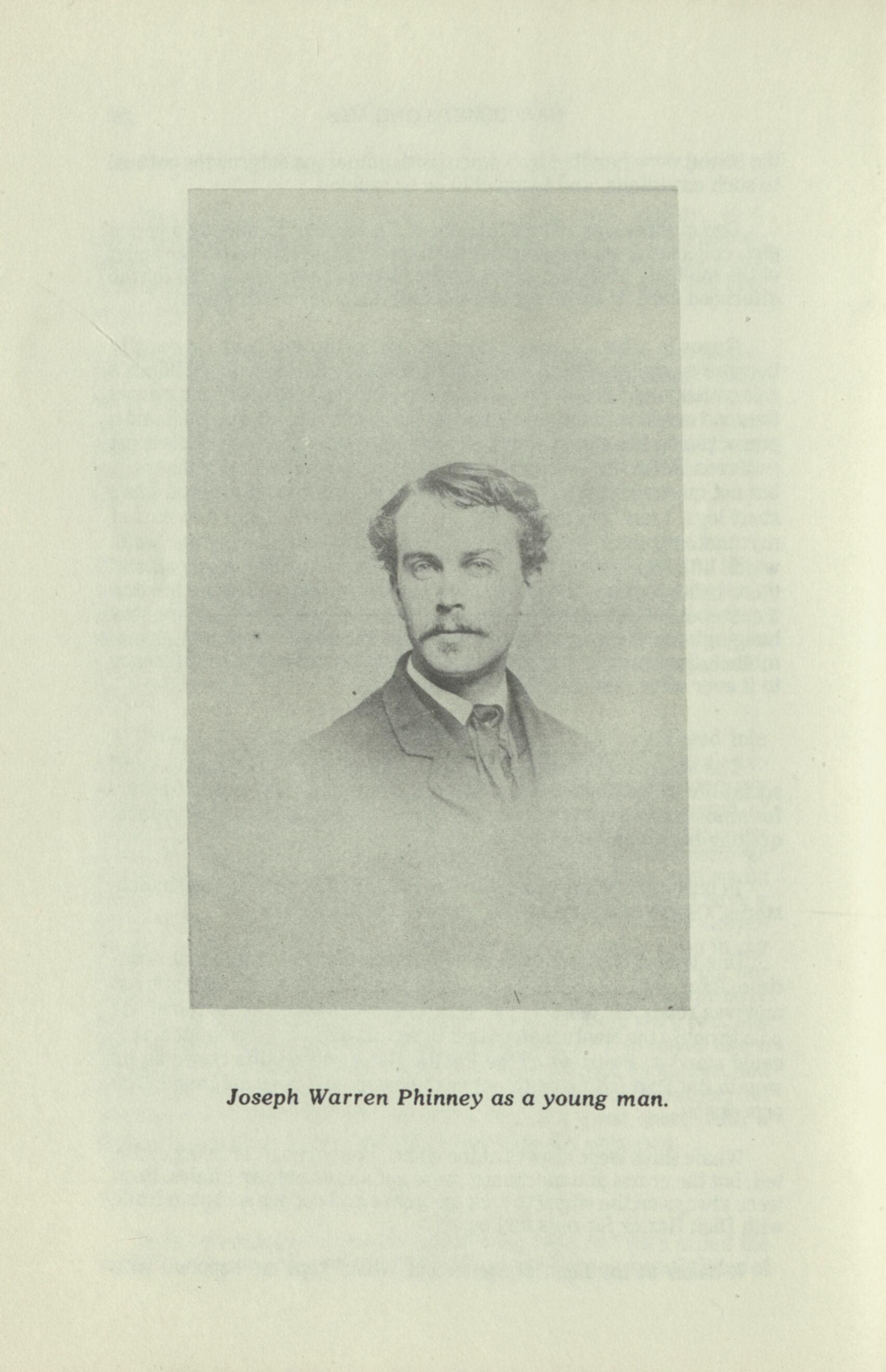

THESE ARE EXCERPTS from the autobiographical reminiscences of Nantucket which my grandfather, Joseph Warren Phinney, dictated to my Grandmother a year or so before he died.

My Grandfather was born on Nantucket Island in 1845 and died at the end of 1934 in West Medford, Massachusetts. I'm adding here a few more dictated anecdotes which were not included in the printed manuscript.

Orphaned before he was four years old, he moved to Sandwich, Massachusetts, with his grandmother and grandfather at the age of seven or eight.

The Cape Cod Advocate was a newspaper published in Sandwich in 1860 by Matthew Pinkham and Benjamin Bowman. Bowman, the printer, enlisted in the army in 1861, and Joseph Warren Phinney got his job at $3.00 a week. Thus began the work that he was to follow the rest of his life.

Although brought up in the Quaker faith, he twice enlisted in the Union Army. Once he was returned because of his age, but the second time he was old enough to become a corporal with Co. A, 5th Regiment Infantry. After the war he went on with journalism and the printing business, living in both the middle west and New England. Later on my Grandfather became a well known authority on type foundings, and became manager of the American Type Foundry.

I remember, as a child, sitting on his lap, as he sang sea chanties to me or told stories of the Civil War — how he once saw Abraham Lincoln who visited his regiment stationed outside of Washington. My grandfather did not inherit the love of the sea from his forebears who were often whalers and captains in the China trade, or from his own father, a captain who lost his life in the burning of his ship on Lake Erie. My Grandfather recalled to his family that an uncle of his had a fleet of whalers and was very wealthy. When he was ten years old, this uncle tried to get him to "ship before the mast". When he wouldn't go, the uncle had no further use for him.

24

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

Nantucket, Far-Away and Long Ago

Why I was bamboozled into talking with your mother, of a miscellaneous account or, story of how and when I came to life and continued to live until the present time, is a mystery. It is a story for those who know how small a thread it was strung on. Part of it I saw, and part of it I was told.

About my first consciousness is hearing that my Cape Cod father, Warren Phinney, and my Nantucket mother, Henrietta Jane Smithi, were married on the deck of a ship captained by my father. They have only meant names to me. The young mother passed out of life as I came into it.2 Before I was four years old my father's effects were sent to my grandparents on Nantucket by a Cleveland Lodge of Odd Fellows. He died in the burning of the Propeller Goliath, on Lake Erie.3

About the first relative I recall was an uncle, who returned from a Cape Horn voyage. He was fond of me, apparently, and psed to fill a coat-pocket with sugar pipe-stems, long and hollow, so I could draw air through them, playing they were cigars, until they so melted that they disappeared. This seems a trifle to remember, but everything is serious with a young one, and those sugar pipe-stems have stayed with me all this time.

When a little older my first tragedy came, and I plunged into crime. Wednesday afternoon was the Cent School holiday. I planned to spend it on the wharf with my chum, Arthur Folger. Before leaving, my Grandmother was to send me on an errand — for one pound of saleratus sand one-quarter of a pound of cream-of-tartar, a total of ten cents. She sent me to the cupboard for the money, and as I counted over the ten big copper cents, the devil suggested that one copper cent would never be missed by my Grandmother, and Arthur and I could have a spree with it. I pocketed the extra copper, and as I passed my Grandmother on the way out, she asked me how many pennies I had in my pocket. I promptly lied that I had only ten. The wise old lady put her hand into my pocket, and counted twelve cents. It was the surprise of my life! I had planned to steal only one cent, and there were two. She started Arthur home, and I was put to bed, where I wrestled like a criminal with my crime. I had no dinner, but was called for supper, and the family stopped eating as I took my seat next my Grandfather, full of shame and fear. My Grandmother was a a good sport, with a Quaker's belief in silence, and practiced what she preached.

In the prosperous days of Nantucket the boys and men sailed the world over in search of whales. The business and the responsibilities of

NANTUCKET, LONG AGO

25

the island were handled by women, with numerous outgrowths natural to such conditions, and found only on Nantucket.

One of these was "The Cent School". A woman, frequently a young girl, collected from the neighborhood the small children, for the relief of the mothers, charging a cent for the forenoon care and a cent for the afternoon care. It made for a small cash income, worth while.

Opposite where I lived was such an institution, and I naturally became a scholar. There was usually a short recess for the children's relaxation, and I recall that during one of them I smelled from across the road my Grandmother's gingerbread. I scurried across and found a pan of piping-hot gingerbread, and promptly absorbed one of the most generous slabs. My Grandmother, unfortunately for me, saw the theft, but not quick enough to stop it. The road was deeply rutted, and I had short legs. I tumbled into every rut, and as I crawled out, that part of my anatomy most in display received a hard and corrective hand, which lifted me along lively until I got to the steps of the school, and there being so many steps and such hearty smacking, I stumbled into the school-room roaring lustily and demoralizing the scholars, but hanging onto the gingerbread! With the fairness of a perfect grandmother, there was no further punishment at the time, and no reference to it ever after. The end justified the means.

The absence of men voyaging for whales threw the business and social life of Nantucket into the hands of women. Their opportunities for amusement were of the neighborhood — meetings for candy frolics, quilting-bees, church sociables, etc.

In business the women made journeys to Boston to replenish their stores, Centre Street being the original "Petticoat Lane".

One boat a day from the mainland brought the mail about noontime. Back of the Post Office was a tall pole, and after the mail arrived and was ready for delivery, a black ball was hoisted to the top of the pole to notify the Nantucketers that the mail was being distributed. One could stand on the steps of the Pacific Bank and see the crowd on its way to the Post Office, with only an occasional boy or old man in the procession.

Whale ships were always at the wharf, under repair or being outfitted, but the crews and mechanics were not active in town affairs. Boys were always on the wharf to pick up bronze and copper scraps to trade with Dick Hosier for nuts and candy.

A baker at the head of Steamboat Wharf kept me supplied with

Joseph Warren Phinney as a young man.

NANTUCKET, LONG AGO

27

ship-bread baked as hard as brick — the kind Cape Homers took out for whaling crews.

I recall a ride on a Nantucket calash6 — a two wheeled affair, with no seats, but with a rope lashed on each side to hold onto in riding. It was my first and only voyage to the Sheep-Shearing, Nantucket's great merry-making event, usually lasting the week.

At the entrance to the grounds was an old blind man, bare-headed, seated on a keg, fiddling one tune, and repeating monotonously "To you can, to you can't, all the way to shearing." Barney Gould, a Cape Cod itinerant, looked after Blind Frank's comfort as far as might be.

In those days the United States mail was not reckoned reliable, and Barney delivered letters between Boston and Provincetown, and, he claimed, as far as San Francisco, for his uniform price of ten cents. Barney is credited with making the journey to California with five letters at ten cents each, bringing back acknowledgments of the letters, and also samples of black sand showing flakes of gold. After I came to Boston he brought me a letter from my Grandmother, and refused the quarter I offered him, his charge being ten cents only.

One of my uncles sailed the China seas — the term for deep-sea merchant sailing. The China trade was a large part of Newburyport and Salem prosperity, in which big fortunes were accumulated. Uncle Billy was a Nantucketer, and planned to visit his home at the end of each voyage. Aunt Mary was his wife — the salt of the earth, a natural nurse, to whom the neighborhood turned for sicknesses and births. One room in her house was devoted to all sorts of herbs from all parts of the world, warranted to cure what ailed you. Uncle Billy had supplemented her assortment with strange remedies collected during his voyage.

Aunt Mary was monstrously stout. Once a year my Grandmother gathered her three sisters to an anniversary dinner. I recollect Aunt Mary in a beautiful green silk dress, an embroidered red shawl, and a purple calash7, with a string pulled to protect her face from the sun. These wonderful garments were testimonials of Uncle Billy's affection and artistic selection. She always came in a two-wheeled cart, seated in a chair, as no other vehicle was big enough!

It was a Nantucket opportunity to sometimes order special dinner sets from China, in original styles of decoration. Aunt Mary wanted a new set. She decided to have the different pieces bear a selection from the Bible. To prevent possible mistakes she wrote the verse, designated where it must be placed, and cautioned with the words "Put it here." Uncle Billy took the copy and the instructions to China, and on his next voyage brought back Aunt Mary's set, proud and happy! It was the

28

HISTORIC NANTUCKET

most famous dinner set that ever arrived from China! The Chinaman was absolutely literal, and he had followed copy exactly — Aunt Mary's handwriting, her Scriptural verses, and her directions. The piece I remember as most satisfactory was in Aunt Mary's peculiar writing, "Suffer little children to come unto me. Put it here."

Returning from one voyage, Uncle Billy brought home a talkative parrot. Aunt Mary hung the cage in the sitting-room, the bird wandering where it pleased. Her ambition was to teach it "Now I lay me down to sleep." Sometimes Aunt Mary, with Uncle Billy at home, would show off the parrot, holding it on her wrist, and the bird would get as far as "Now I lay me down to sleep," and Uncle Billy would pull a tail feather, and out would come "Damn you, go to hell!" — indicating its fo'cas'le instructions.

When I was about eight years old, my grandparents moved from Nantucket in a schooner, with all their household effects, landing at Buzzards Bay. From there they teamed to North Sandwich. At the end of some months another move was made to my Grandfather's birthplace in Spring Hill, a Sandwich village.

On the morning we were to sail from Nantucket our cat appeared with five kittens. She was conscious that we were to leave the house, and as we started for the wharf she picked up one of the kittens in her mouth, carried it a short distance, dropped it, and went back for another, until she had brought together all five. This she repeated at intervals until she landed them all on the wharf. As we boarded the schooner she stood there and miaowed pathetically her Good-bye. Finally my Grandfather took her along.

In our back yard was an old-fashioned, tall, wooden pump. One morning a neighbor's dog chased our cat until she landed on top of the pump. The dog jumped and barked in an effort to reach her. Getting tired of the dog and the noise, she watched her opportunity, and landed on top of him, putting her claws into his shoulder and back. Yelping, he started for home, and as they passed under the top rail of the fence, she adroitly jumped off and watched the dog disappear.

She was a great rat-catcher, always bringing her game to my Grandmother's bedroom window and miaowing until told she was a "Good Pussy," when she left contentedly.

It was necessary to get rid of her. Tying her in a bag, loaded with a big stone, I took her a mile from home, and dropped her in a deep creek to drown. When I got home she was at the back door, waiting for me.

NANTUCKET, LONG AGO

29

The string had loosened, and she got out of the bag all right.

I tried once more. I took the cat in the engineer's cab by train to Wareham, some thirty miles away, dropping her at the station. This time it took her between two and three days to reach home again. We decided at length to keep her until she should pass out without violence. Her name was Jenny Lind.

I found these two additional recollections of my Grandfather which were omitted from the manuscript printed by my Grandmother for her family after his death.

"The irresponsibility of sailors is well-known. They will stay indefinitely ashore, but when the mood strikes them, they will pick up a berth, and go to sea. E. Snow, who left his tools where he dropped them, went to sea, and was never heard of again. On the beach was his branding iron, just as he left it. "Captain Pollard was 'gum-shoe' man of the town. The boys were supposed to be in the house by nine o'clock, and he used to make a tour of the town with a long library pole with an iron hook, under his arm. He was a short fat man, jolly, loving the good things of life, and they used to say Aunt Mary, his wife, who had been a tailoress, when he needed a new pair of breeches laid him down on the cloth and marked him out on it. When he wore out the knees he turned them round hind side fore'most. Once a year on the anniversary of the loss of The Essex he locked himself in his room and fasted — of course he could have lived on his fat."

This later bit about Captain Pollard was probably omitted by my Grandmother, because until relatively recently The Essex disaster was rarely discussed amongst Nantucketers. (As a child I was told not to mention it to natives of the island.) Only by chance when doing some genealogical research did I find out that I had two ancestors who were indeed survivors of that ill-fated vessel.

Diana Taylor Brown

Reference Notes

1. Henrietta Jane Smith was born in Nantucket in 1822. The name of the ship on

which they were married on June 3,1844 was the "Lavinia", named after Cap