48 minute read

4. Pantomime, Paratext, and Expressivity

from Silent Ibsen

4. Pantomime, Paratext, and Expressivity Ghosts (George Nicholls, Majestic, 1915)

Mark Sandberg

This chapter concerns a “failed” silent-film adaptation of Ibsen that might not have been a failure after all, or at the very least, not in the way that is usually assumed. The version of Ghosts produced by the Majestic Motion Picture Company in 1915 shows, no doubt, the difficulties of transposing a densely verbal naturalist drama to the visual regime of silent film, but the usual conclusion – that Ibsen’s plays are essentially untranslatable to the screen – does not do justice to the more complex contemporary promotion and reception of this film at the time of its release. It is possible to appreciate Ibsen’s dramatic texts, as I do, for his mastery of the analytic dramatic form, his evocation of the unsaid underneath all that is said, and the subtle psychology of his characters without weaponising the excellence of his stage works as an easy criticism of any filmic adaptation. Such aesthetic hierarchies, anchored in ideas of medium specificity, obscure the peculiar characteristics of this 1915 film and the ways that it does something more than fall short of Ibsen’s theatrical standard. By examining the 1915 film of Ghosts within the assumptions and expectations of its own media environment, it is possible to recover historical perspectives that evade the aesthetic hierarchies that have since then become the de facto and somewhat facile explanations for why there are relatively few “Ibsen films”. This larger historical contextualisation beyond a simple adaptation of drama into film follows the lead of Eirik Frisvold Hanssen’s

examination of Ibsen films of the 1910s in terms of both their aesthetic position and their paradoxical role in “uplift cinema” of the transitional era between 1907 and 1917. After admitting that these Ibsen adaptations fall short on both counts (aesthetically and morally), Hanssen states: “[W]hat remains fascinating about the Ibsen adaptations of this crucial period is how they make visible cinema’s negotiation with other more established media and cultural and social norms at a time when the notion of what a film is and should be is constantly contested and redefined” (2017, 176). In what follows, I will examine this “negotiation with other more established media” in terms of two supplementary communicative strategies that were to varying degrees available to the 1915 Ghosts when adaptation difficulties arose. For the sake of brevity, I will call these “pantomime” and “paratext”, though the argument for each will involve more nuance than those terms convey in themselves. On the one hand, an examination of the extended performance context allows for recovery of the legibility strategies and virtuoso expressivity that made the acting in this film an attraction instead of a flaw. At the same time, the incomplete support from these legibility strategies in performance necessitated the creation of a paratextual ensemble surrounding the film. These adjacent textualisations of the film make clear the way that Ibsen’s name functioned as a positive constellation of composite impressions when the acting could not convey what was needed in the adaptation. The fact that both contexts to a certain degree functioned as communicative supports for a cinematically transposed densely verbal drama can easily lead to familiar conclusions about essential medium-specific deficiencies of “the silent Ibsen film”; this chapter acknowledges those contextual support functions but also suggests that an intermedial approach to this 1915 film opens the way to understanding this Ghosts as a different kind of success.

A Prestige Production

The Reliance and Majestic Studios in Hollywood, where this Ibsen film was produced in 1915, was described by an in-house trade-press article by the film’s distributor, the Mutual Film Corporation, as follows:

A veritable city by day, at night transforming itself into a monster fairyland, with thousands of electric lights twinkling and flashing in the darkness, is that section of Hollywood, California—to be exact, No. 4,500 Sunset Boulevard—occupied by the Reliance and Majestic studios. (Reel Life, 1915d)

This was D. W. Griffith’s production facility, the one that a few months later, in July 1915, would team up with Mack Sennett’s Keystone studio and Thomas Ince’s Kay-Bee studio to form the Triangle Film Corporation (the 1916 Pillars of Society film was produced by Triangle after the consolidation, and this Ghosts just before; see also King in this volume). The distribution of Ghosts was handled through the Mutual Film Corporation, direction came from George Nicholls under Griffith’s supervision (the degree of his involvement is unclear), and the film was released on 24 May 1915. Its most famous star was the lead actor, Henry B. Walthall, who played the roles of both Captain Alving and his son Oswald. Mary Alden played the role of Helen Alving. Both of these leads had worked with Griffith the year before during the filming of The Birth of a Nation. Most famously, Walthall had played the lead role of the Confederate soldier and imagined founder of the Ku Klux Klan (Ben Cameron, the “Little Colonel”) and Mary Alden had performed in blackface as the mixed-race woman Lydia Brown, the housekeeper/mistress of the white Reconstruction Senator Austin Stoneman. Although this racist epic has since become notorious for its role in perpetuating the South’s “lost cause” narrative, at the time it was also considered a major leap forward in narrative ambition and technique (see also Rees in this volume). Walthall had previously performed in other film adaptations of literary sources, as he had also starred in two films based on works by Edgar Allen Poe from 1914 and 1915 (entitled The Avenging Conscience and The Raven); it would also be Walthall and Alden who would again team up for another round of Ibsen adaptation by playing Karsten Bernick and Lona Tonnesen in Triangle’s Pillars of Society a year later. All of this detailed production information situates this adaptation of Ghosts firmly within mainstream developments in Hollywood’s transitional era leading up to 1917 – the major studio, well-known

actors, and the turn to prestigious literary material to perform a kind of “uplift cinema”. Today, that term seems retrospectively unacceptable for a film like The Birth of a Nation, and as Hanssen also notes, Ibsen’s reputation as an author of highbrow literature could not really mitigate the discrepancies raised by his controversial themes and biting social critique of the very middle-class mores that “uplift cinema” was attempting to appropriate (2017, 175). As one contemporary reviewer put it, “‘Ghosts’ is not a pretty story. But it is a forceful story, and one which will create thought and talk” (Proctor 1915, 67). One might say the same of Edgar Allen Poe’s writing (as that reviewer in fact did), the source for two other Walthall vehicles of the time: a canonical writer, sure, but also morbid in ways ill-suited to an “uplift” project. The apparent ability to overlook the effects of the actual subject matter conveys the intensity of cinema’s overriding embrace of the cultural capital of canonical literature and famous authors in the transitional era, despite the perceived moral valence of the literature itself. If cinema can “create thought and talk”, the reasoning seemed to go, it has vaulted film into a different cultural category. So, what kind of Ghosts was this? Despite the film’s opening homage to the great author – a tableau-like pose by the Vitagraph actor Karl Formes in Ibsen costume (see the introduction in this volume) – it would otherwise be a stretch to call this adaptation “respectful” when applying typical fidelity criteria; there are too many significant departures from Ibsen’s text. For example, a doctor figure has been added to the cast. In the play, of course, the knowledge of the hidden half-sibling relationship between Osvald and Regina is carefully guarded by Helene Alving,1 who reveals it to Pastor Manders and thereby makes clear that she understands the risk of incest if the two were allowed to marry. Here in the film, that crucial knowledge is instead doled out to this added figure of the doctor. He seems to be borrowed more or less from Damaged Goods, a film made a few months earlier in October 1914. Based on

1 Throughout the discussion here, the Norwegian spellings “Osvald” and “Helene” will refer to the characters in Ibsen’s play and “Oswald” and “Helen” to those in the film adaptation.

Eugene Brieux’s cautionary syphilis drama Les Avariés from 1901, which was also translated into novelised form as Damaged Goods by Upton Sinclair in 1913, the film adaptation of Brieux was produced shortly thereafter by the Mutual Film Corporation and thus preceded the 1915 film of Ghosts by Majestic. Ghosts’s doctor figure lectures everyone as pedantically as he does in the Brieux play (typically with wagging finger and a sad shake of the head), a link that did not go unnoticed in a contemporary review of the film that stated, “For those who are not Ibsen students let it be said that ‘Ghosts’ resembles ‘Damaged Goods’ in being a study in inherited taint” (Proctor 1915, 67). The doctor of this silent film Ghosts is thus saddled with providing a reminder of the public health consequences of the initial alliance between Helene and the Captain. When Regina’s mother, Johanna, dies in the midst of a written confession of the identity of the Captain as Regina’s true father, it is the doctor who intercepts and hides the note from the other characters. When the doctor then hears of the sudden wedding plans of Oswald and Regina, he is also the one to race to the church to stop the wedding in the nick of time. The main effect of giving the doctor such a crucial role of narrative mediation is that the play’s tragic element is eliminated as well: here, Mrs Helen Alving knows no more than the other characters, and her actions after the Captain’s death thus lose their aspect of tragic misdirection because there is no disparity between her knowledge and her actions. Here in this filmed version, she is only a victim, achieves no belated insight, and, unlike Helene Alving of the play, provides no tragic dimension. There are other differences as well – Regina’s father in the film is not a scoundrel like Engstrand in the play, but a respectable, kindly, pipe-smoking gentleman. Pastor Manders is no longer a sly, calculating hypocrite and the indirect cause of Helene Alving’s tragedy, but a milquetoast pious man of the cloth – a walking cliché, really. Regina has also lost her ruthless vitality here, giving instead her best impression of Ophelia as she runs distraught to her likely suicide after the halted wedding. (In the play, of course, she swiftly recalculates how her chances would improve if she nimbly pivoted to Engstrand’s brothel instead.) Most crucially, in the final scene Oswald takes poison

himself while his mother runs for help from the doctor, removing the euthanasia element of the morphine pills in the play and the uncertain, suspended aspect of the drama’s close. Even more significant is the film’s straightening out of Ibsen’s famously recursive narrative timeline, which in the drama gradually reveals pieces of the past that finally cohere into a terrible realisation and reconstructed storyline by the time the curtain falls. The 1915 Ghosts chooses to represent directly the crucial events of the past instead of leaving them implicit or narrated gradually as fragmentary clues – a linear exposition tactic that the other Ibsen films of the early teens also employed (see King and Yalgın in this volume). The intricate retrospective, analytic structure of the original play – one of Ibsen’s key contributions to Western drama – is in this way entirely lost; in the film there is no detective activity made available to either the characters or the spectators, no crucial secret to piece together from strategically placed euphemistic hints, and no gradually dawning understanding that ambushes the viewer. Thus we also lose the resonance of the play’s title: there are no “revenant” narrative bits from the past that make a ghostly appearance in the present; they come instead as straightforward linear exposition from the earliest point of the dramatic plot until the end of the play. If the ambush of the present by the past is key to Ibsen’s aesthetic form and his social critique, then it seems fair to say that the film abandons the most Ibsenian aspect of the play. The film’s depiction of the past could have been handled in flashback instead of in the chronologically linear way in which it is actually presented. Flashbacks had developed to that point by 1915 and were known from other films, as Maureen Turim has shown in her history of the technique. She states: “It does appear that flashbacks clearly marked as temporal analepses were quite common in the teens—although relatively few of these films have survived” (1989, 28–29). That is to say, if one were already going to go to the trouble of visually dramatising the past, as this film does, one could just as well have embedded the sequences as shorter recursive, remembered revelations as present them in sequential order as a backstory (in this case, approximately the first twenty-seven minutes of a fifty-nine-minute

film – not a trivial proportion). Choosing a flashback strategy might have preserved some of that sense of the relentless pressure of the past on the present that exists in the original play. Of course, it is hard to argue from absence about roads not taken. David Mayer suggests an explanation can be found in Griffith’s “arm’s-length supervision” of Ghosts, namely that Griffith’s investment in “concurrent—parallel and overlapping—actions” made the flashback less interesting to him: “His narratives unfolded in a forward direction and were set in ‘the present’” (2009, 169), although it is unclear whether Griffith’s tastes as producer were determinant in Nicholls’s film. It is relevant to note, however, that the initial overt, linear depiction of the implicit theatrical backstory was also the strategy used in the 1911 Pillars of Society film (and of course, the same recursive role of the past is crucial to that plot; see also King in this volume). That approach could be seen as consistent with the much shorter one-reel format that conveyed the dramatic action in briefer tableaux, with the backstory portion of the narrative taking the form of brief scenes from the past very much similar in narrative logic to those of the dramatic present. The same approach was taken in the later 1916 version of Pillars of Society, however, so its use in Ghosts was probably not simply a holdover from the narrative logic of shorter films. In fact, the longer feature-length (one-hour) films that had become increasingly common internationally after 1913 might have had reasons to fill out that past action with a fuller exposition: without recourse to extensive dialogue (which would have impossibly weighed down the film with intertitles), the filmmakers needed more action sequences that could play out for a longer time: in Ghosts, a visually exciting dinner/ dance party at Captain Alving’s house, or the dynamic movement of an invented horseback riding date between the Captain and Helen out in the open air on a country road. The past in this film seems intended not to haunt the present as much as to eat up playing time in the first part of the film. Reinforcing this impression is the fact that extended sequences (the chase to stop the wedding, for instance) have also been added to the second half of the story, which is set in the present.

The Media Essentialists

Two of the most frequently cited early film theorists writing around the time of this film in 1915 and 1916, Vachel Lindsay and Hugo Münsterberg, seem provoked by the attempt to adapt Ibsen’s drama to film. Both of them use Ibsen’s stage drama somewhat reductively as an explanatory foil for the new cinematic art form, emphasising the comparative externality and visual compression of the silent cinematic image while still defending in equal but separate measure the achievements of serious theatre (see also King in this volume). Lindsay specifically discusses Majestic’s Ghosts – which in 1915 would have been a film quite contemporary with the publication of his book – in order to insist on this medium specificity. He writes, “It is a principle of criticism, the world over, that the distinctions between the arts must be clearly marked, even by those who afterwards mix those arts” (2000, 109), and in his appraisal of the problem of adapting the Ibsen drama to film, he states, “Wherever in Ghosts we have quiet voices that are like the slow drip of hydrochloric acid, in the photoplay we have no quiet gestures that will do trenchant work. Instead there are endless writhings and rushings about, done with a deal of skill, but destructive of the last remnants of Ibsen” (ibid., 108). In light of the flashback discussion above, it is interesting that there apparently was a tableau-like scene (not extant in the Library of Congress print of the film) occurring when Oswald goes off to paint the portrait of the King. Lindsay describes the scene at length:

He is looking sideways in terror. A hairy arm with clutching demon claws comes thrusting in toward the back of his neck. He writhes in deadly fear. The audience is appalled for him. This visible clutch of heredity is the nearest equivalent that is offered for the whispered refrain: “Ghosts,” in the original masterpiece. This hand should also be reiterated as a refrain three times at least, before this tableau, each time more dreadful and threatening. It appears but the once, and has no chance to become a part of the accepted hieroglyphics of the piece, as it should be, to realize its full power. (ibid., 107)

Lindsay imagines the hairy arm (which we in the surviving print do not see at all) performing the interspersed function of the flashback

imagined earlier in this discussion, returning as a regular visual refrain to substitute for the “acid drip” of dialogic refrains in the original.2 The overriding logic of his analysis, however, is to assert the distinctive qualities of each medium that make the search for equivalence necessary in the first place. Employing a rhetorically contrastive symmetry, Lindsay famously states:

At the close of every act of the dramas of this Norwegian one might inscribe on the curtain “This the magnificent moving picture cannot achieve.” Likewise after every successful film described in this book could be inscribed “This the trenchant Ibsen cannot do.” (ibid., 105)

Lindsay’s pithy summary reinforces a media essentialism that has persisted to this day as an explanation for the lack of successful film adaptations of Ibsen. In Hugo Münsterberg’s book on film perception from the following year, The Photoplay: A Psychological Study, he too wrote of Ibsen in media-essentialist ways:

The usual make-up of the photoplay must strengthen this effect inasmuch as the wordlessness of the picture drama favors a certain simplification of the social conflicts. The subtler shades of the motives naturally demand speech. The later plays of Ibsen could hardly be transformed into photoplays. Where words are missing the characters tend to become stereotyped and the motives to be deprived of their complexity. (1916, 219)

Like Lindsay, Münsterberg elevates this observation to the status of a general law of separate-but-equal media, an attitude he also conveys when making the following observation: “If ever a Shakespeare arises for the screen, his work would be equally unsatisfactory if it were

2 Lindsay’s mention of this now-unavailable scene is plausibly accurate, not only because of the detail of his description but also because, in the current versions, there is a puzzling narrative break around the moment he describes, occurring between the intertitles “A Royal Command to paint the King’s portrait” and “His hope blasted, he returns home”. The visualisation of the “clutching hand of heredity” as a hairy demon arm in this missing tableau scene likely also explains the later intertitle using exactly the same phrase, which does not entirely make sense in its current context without the visual echo back to the missing tableau.

dragged to the stage. Peer Gynt is no longer Ibsen’s if the actors are dumb” (ibid., 196). It is important to note that the commonplace observation “it would no longer be Ibsen” – which appears so frequently that it passed easily under the radar without argument – loads up that authorial name with a high degree of assumed media essentialism that might be worth revisiting in a new light. As Hanssen and others have pointed out, the view that Ibsen’s drama is fundamentally unadaptable to film has persisted mostly unchallenged from the time of Lindsay and Münsterberg to this day (Hanssen 2017, 159; Elliott 2013, 27), but it seems worth adding that, both now and then, those making that claim often do so in order to signal an elite command of each medium. That attitude is clear in Lindsay, at any rate, who wants his reader to understand that he knows his theatre. The assumptions guiding that claim, however, deploy models of influence or adaptation still dependent on aesthetic models of fidelity that make it difficult to see the filming of an Ibsen drama as anything other than a failure to find a meaningful equivalent. Both Lindsay and Münsterberg, in other words, approach Ibsen adaptation as they might approach an unusually tricky linguistic idiom, by simply retreating into easy claims of untranslatability. This is where it might be helpful to pivot to a different model and think about these Ibsen films not as drama-into-film translation measured by successful or failed fidelity, but as examples of multiple movements of remediation within a media environment. A film such as the 1915 Ghosts would in this light be seen less as a failed Ibsenian drama and more as a remediated or repurposed media object in its own right. This eliminates the need to defend Ibsen or his aesthetic achievements, which tends to create a locked-in position where it is difficult to regard the film of Ghosts with anything other than disdain or bemusement. Instead, one might choose to see this film from a 1915 perspective, as an interesting nexus in a media environment, as will now be traced through its relationship to traditions of stage acting and as accompanied by paratextual support.

Coming for the Show: Acting Styles in Transition

Despite the importance of dialogue in Ibsen’s play, in this filmed version of Ghosts one finds it used rather sparingly in the intertitles. There are forty-eight intertitles in the Library of Congress print, but only eight represent dialogue, and of these only three seem to use Ibsen’s dramatic text as a source. In one early example, Pastor Manders states, “Your duty is to your husband” (in Ibsen’s text, this is cast in retrospective dialogue: “[…] And your duty was to hold firmly to the man you had once chosen”3 (1906, 202)),4 and then in another, Helen tells Manders, “I want my son to inherit nothing from his father. He’s mine—all mine” (in Ibsen’s text: “I was determined that Oswald, my own boy, should inherit nothing whatever from his father”5 (ibid., 211)). The third example, the most famous line in the play, comes at the dramatic climax of the film: “Give me the sun, Mother – Give me the sun!” (“Mother, give me the sun”6 (ibid., 294)). The remaining few dialogue intertitles use invented speech for different plot points, especially in showing the backstory sequences for which there can logically be no dialogue to borrow from the play since those actions were either invented for the film or left undepicted or reported elliptically in the play. The more typical intertitles in this film are narrative inserts that advance the plot descriptively in a summary way. (The Oscar Apfel adaptation of Peer Gynt of the same year did attempt intertitles that mimicked conversational turn-taking as in a printed dramatic script, but Ghosts does not pursue that strategy; see also Rees in this volume.) Compounding the issue of lack of dialogue was the fact that, after 1913, the length of feature films changed from one to five reels (Sandberg 2005). Previous Ibsen adaptations (such as the early ones from 1911 dis-

3 In the Norwegian first edition: “Og Deres pligt var at holde fast ved den mand, som De engang havde valgt” (2008, 429). 4 I use William Archer’s 1906 translation for comparison here since that would have been the likeliest available English version for the film producers in 1915. Vachel Lindsay, in fact, mentions that he prepared for the film viewing by refreshing his memory with the Archer translation (106). 5 “Jeg vilde ikke, at Osvald, min egen gut, skulde ta’ nogetsomhelst i arv efter sin far” (2008, 438). 6 “Mor, gi’ mig solen” (2008, 525).

cussed elsewhere in this volume; see King and Yalgın) were condensed into a series of summary tableaux presented over the course of 10 to 15 minutes. The 1915 version of Ghosts came closer to one hour in length, and this presented the paradoxical challenge of extending the playing time without being able to rely on all that missing dialogue (there were fewer difficulties in the same year’s film version of Peer Gynt since that play lends itself better to an elaborate string of visual scenes than Ghosts). It is even more challenging to convey the Ibsenian sense of the unsaid beneath the said when so little is said in the film in the first place. A 1916 article in Moving Picture World on Ibsen’s creative method confronts this issue of dialogue in the longer five-reel form. Although the article indicates that a five-reel film would have a “scenario of acts” mimicking the overall organisation of a stage play, there was nevertheless clearly a concern about filling the time, given the removal of dialogue and the need to distil all of the reported plot into overt action:

An application of this method to the big screen story would be to write a rude scenario of the action. In the first act the characters do so and so, in the second so and so, and so on, to determine, if for no other purpose, whether or not there is sufficient material for five reels. The writer may otherwise reach his crisis long before the fifth reel with a resultant amplification in the wrong place. (Harrison 1916, 1804)

One solution to the problem of length was to turn to other gestural theatrical traditions to fill in for the missing naturalist dialogue, although perhaps not in the way one might assume. Pantomime, the most direct substitution of gesture for speech, would be unsustainably tedious as the main communicative mode throughout a one-hour playing time, clumsier even than overloading the film with dialogue intertitles. Other approaches to gestural expressivity might be too vague and impressionistic to convey the crucial details of the Ibsenian plot and its interplay between the overt and the hidden. But framing the problem like this assumes that contemporary audiences shared the concerns about the faithful adaptation and reproduction of Ibsen on film. That seems unlikely, as there is little actual detailed comparison of the film with the original play in the contemporary press. It would seem that few film

viewers knew more about Ibsen than his general literary reputation. In that light, it may be worth exploring whether expressive acting styles could have functioned as an attraction – a show in their own right – as much as a compensatory compromise for what was missing. But first, an examination of the complex historical interplay between stage and screen acting in the early 1910s will help situate this 1915 Ibsen film. The several studies of transitions in screen acting in the first half of the 1910s note a gradual abandonment of straightforwardly pantomimic styles. As Kristin Thompson notes, “Between approximately 1909 and 1913, acting styles in the American cinema underwent a distinct change: an exaggerated pantomime gave way to a system of emphasizing restrained gestures and facial expression” (1985, 189). “Facial acting,” she argues, was in part made possible by the closer proximity of the camera but was also a marked preference in the emerging American style (ibid., 190). Thompson rightly points out that, while pantomime in the European style “conveyed a good deal of information” to the audience, it was a poor choice for communicating psychological causality and, in her assessment, was largely on the way out as a dominant acting style by the mid-teens. Roberta E. Pearson, who devotes an entire chapter of her book Eloquent Gestures to a discussion of Henry Walthall’s acting styles, proposes an overly binary distinction between an earlier histrionic acting practice and an emerging verisimilar style but nevertheless nuances her assessment of Walthall’s career by noting the overlaps and stylistic pivots he could perform as he varied his roles, over the progression of his career and even within a single film:

Here we have an actor of preeminent reputation among his contemporaries who clearly thought about his craft and yet who, nonetheless, exhibits no clear “progression” toward the verisimilar code. Rather, Walthall alternates between the old style and the new according to the film’s narrative structure and other signifying practices, as well as according to his character type. (1992, 119)

Surveying the many Walthall films from this period, Pearson also notes that he clearly adjusted his acting style with each filmic genre as well.

An especially perceptive assessment of trends in acting styles can be found in the work of Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs. Arguing from historical context and sources, they find the identification of “pictorial” acting styles to be more useful conceptually when describing the main trends of the 1910s (1997, 82). The striking of attitudes (moments of dilated or even fully paused temporality in which a posture was struck and held), which was carried over from the tableau traditions of nineteenth-century theatre into screen acting, allowed for dramatic emphasis: “Like music, posing was used to underscore dramatic moments, to convey and heighten emotions, to elongate and intensify situations” (ibid.). The pictorial mode also provided stage actors with an expressive alternative to cruder forms of pantomime, which Brewster and Jacobs define more narrowly as the simple “substitution of gesture for dialogue” (ibid.). Also relevant to this study, however, is their passing mention that, in stage acting, the Ibsenian drama represented one of the strongest breaks with this pictorial tradition (ibid., 95), which of course made the adaptation of his works to the screen the most challenging:

[W]e would like to stress the daring involved in adopting this kind of refusal of pictorial effect in the medium of silent film. Naturalist theatre was famously wordy, and to some extent the emphasis on the language compensated for the opacity of gesture and action typical of the [Naturalist] acting style. It required considerable sophistication to adapt it to the new medium. (ibid., 96)

In sum, this research into American film acting of the early 1910s indicates that at the time Ghosts was being produced, one can identify a rapid waning of directly mimed action, the enduring influence of a pictorial acting tradition, the emergence of new forms of verisimilar acting codes, and, most importantly, a likelihood of encountering any of these acting styles overlapping within or between films. Moreover, where the film in question was using a play from the Naturalist school (like Ibsen’s Ghosts) as source material, there was a further clash between what that play had already accomplished in terms of shifting the norms of stage acting and what was still happening at that time in the emergence of codes for the screen in its new adaptation context. All

of this together serves to make the 1915 Ghosts a truly “daring” project. What one finds in the film itself is indeed a range of styles and a sophisticated extension of pictorial acting styles. Some of the actors offer vestigially pantomimic acting. Al W. Filson, who plays the doctor, uses finger pointing at characters to make relationships visible or at the head to warn of coming disease, along with extensive head-nodding and fist-pounding while talking to himself to show determination. Although Walthall himself generally avoids the direct substitution of gesture for speech, he too resorts to an extended pantomime in a scene with the doctor immediately after Oswald’s birth. He is shown successively laughing, pointing at the doctor, himself, and the baby’s room, patting himself on the chest, circling his finger in his hand, dusting both hands, opening his arms wide, and laughing again without really getting a clear message across to the viewer. What might this extended pantomime actually mean? Those familiar with the play might guess that the Captain is telling the doctor that, despite his concerns about the parental fitness of a debauched and drunken father, he will continue on happily as he is. Or perhaps, alternatively, that he is a proud father. Or even that he cares nothing about that child in there. In other words, if this is pantomime used as a communicative crutch, it fails. Sequences like this are not what attract comment in the fan-magazine discussions of Henry Walthall’s acting around the time Ghosts was released. Instead, viewers were more interested in what we might call “expressiveness”. This could take cerebral and affective forms, but in neither case was it framed as communicating the plot detail of the written play. For example, a Swedish actress of the Ibsenian stage, Hilda Englund,7 speculated on the appropriateness of Ibsen’s plays on screen in 1913 by emphasising their suitability for meeting the moviegoing demand for “pictures that think”, for films in which “thought is conveyed by the actions of the character” (1913, 14).

7 For a retrospective overview of her career as an Ibsenian actress, see the letter to the editor by New York theatre critic Dixie Hines, “Ibsen and Hilde Englund” (New York Times 1926). Englund’s Swedish first name is spelt “Hulde” in the IbsenStage database and may have been normalised when she emigrated to America after the turn of the century.

Ibsen’s plays are not “merely narrative”, she states, but present actors with the challenge of depicting pictures of thought: “They not only require acting in the conventional sense, they require thought, and the expression of thought in the face and by medium of the body as a whole” (ibid.). This 1913 assessment from the actress’s perspective predated several Ibsen film adaptations, including Majestic’s Ghosts, and is fascinating insofar as it reaches a conclusion diametrically opposed to that of the film theorists Lindsay and Münsterberg, namely that Ibsen is especially suited for film adaptation in a less verbal and more gestural performance mode because he creates “pictures that think”. More commonly, however, this discourse praises the conveyance of feeling, and Walthall was seen as particularly adept at this. One can see this most easily in his repertoire of characters gone mad in 1914–15, including the part of Edgar Allen Poe in the two films mentioned earlier, The Avenging Conscience (released earlier in 1914) and The Raven (released on 8 November 1915, after Ghosts’s premiere in

Fig. 1. Movie Pictorial profile of Henry B. Walthall emphasising his expressive repertoire. Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library.

May). That autumn, an article in Movie Pictorial called Walthall a “Master Emotionalist”, referring especially to his performance as the Little Colonel in D. W. Griffith’s film (Fig. 1):

Every emotion that can be found upon the strings of human sympathy has been brought into action by this star in “The Birth of a Nation.” Happiness, hope, despair, grief, determination, tenderness, belief, invention, satisfaction, organization, revenge, love, hatred—these and a thousand other reflections of the soul are to be found in Mr. Walthall’s part. And in the expression of each emotion and each mental change will be found the indelible imprint of genius. We do not say that it is Mr. Walthall’s eyes, or his expressions, or his dramatic action, or any other single thing that makes him what he is. It is all of these talents working in unison. (Movie Pictorial, 1915)

The same article continues thus: “In ‘Ghosts,’ his acting was a study and carried with it such pronounced dramatic emotion, it did not seem to be a thing of this world at all. It breathed horror, which means the very frontier of dramatic art” (ibid.). His growing reputation for affective acting is also clear in this assessment of his Ghosts performance in Reel Life (Mutual’s in-house promotional publication for film fans published between 1914 and 1917): “Strong and admirable as his acting has been in the many dramas and Griffith subjects in which he has been starred, the Mutual leading man perhaps never has measured up to the full height of his ability until now” (Reel Life, 1915b). Especially impressive to some viewers was Walthall’s ability to “get things over” to the viewer, as conveyed in this letter to the editor of the fan publication Motion Picture Magazine:

He is the most wonderfully adept actor on any screen. He possesses an untiring energy and ability, perfect control of facial expression, nerve and daring, and the ability to get things over without useless gestures. And if ever his hands and arms are used, they are so tense and filled with expression that they get the idea across; they fill your whole being with the feeling of his every emotion so well that a glance at his face is unnecessary to discern his meaning. Just drop in to your nearest movie and witness his performance of “Ghosts,” and see wherefore I speak. Ugh! I was never filled with horror, dread, not hate of anything so much as I was when I beheld Mr. Walthall as the dissipated father. His hands were hateful, writhing, claw-like things! (Motion Picture Magazine, 1915)

Fig. 2. Ghosts actor Henry B. Walthall compared to Shakespeare actor Edwin Booth in Motion Picture Magazine. Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library.

Although “getting things over” and “ideas across” might sound like the process of pantomime, this viewer’s intense reaction suggests instead that some fans had developed a connoisseur’s appreciation of Walthall’s gestural repertoire itself, his ability to convey feeling, not information, to the viewer. Seeing him test his skills in repeated emotive film roles throughout the mid-1910s was clearly an attraction of its own, independent of any particular narrative context, even a canonical one such as Ibsen’s play. Each story was just another occasion to see the “Master Emotionalist” at work. Although another article in that same issue of Reel Life goes so far as to call Walthall’s gestural performance in Ghosts a revival of the ancient art of “Greek pantomime”, that use of the term seems to be loosely metaphoric, intended to convey the evocation of profound feeling: “Here is a picture, which in its pantomimic power, in its play upon the emotions, outrivals and outclasses the spoken play […]” This writer even speculates that if Ibsen had been able to see this film, he would have had to admit “how much more effectively the screen has interpreted the message which he wished to bring, than all the many masterly productions of the speaking stage” (1915a). That is a big claim, one that upends the usual aesthetic hierarchies. More interesting than the accuracy of the claim itself – this is after all promotional discourse from the film distributor – is the fact that it was “thinkable” at all, that the substitution of expressive gesture for dialogue could be perceived not as a deficiency or compromise, but as something that could in fact be promoted as a positive feature in the trade press, as it was when, for instance, he was described as the “Edwin Booth of the Screen” (Fig. 2), referring to the most famous Shakespearian stage actor of the nineteenth century (Motion Picture Magazine, 1916). There is in fact a remarkable degree of nuance and range in Walthall’s performance in Ghosts, and watching his gestural range suggests an interesting extension of the pictorial acting style. One particular gesture can suggest the whole as Oswald’s disease progresses. While the main image in Figure 2 has likely been taken from The Avenging Conscience, the insert image in the upper left is from Walthall’s performance in Ghosts. It isolates the repeated and escalating sign of the “inherited taint”,

(a) (b)

(e) (f)

(i) (j)

Figs. 3a-l. Montage of several of Walthall’s gestural winces that signal “inherited taint”. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

(c) (d)

(g) (h)

(k) (l)

as an intertitle so delicately puts it: a kind of spasm, reaching for the back of the head. Although not strictly a pictorial pose as it does not involve any real stasis or held attitude, Walthall’s repeated wince does involve a “stereotyped posture” that is both repeated and varied over the course of the film, underscoring the character psychology or dramatic situation, which Brewster and Jacobs include as other elements of the traditional style (1998, 101). There are more than a dozen repetitions of this gesture, with a selection of them shown here as a collage (Fig. 3). This is the film’s past made visible, a gesture that communicated dread and approaching doom to the viewers of 1915, to judge from the popular response. A closer look at these moments even reveals that what Lindsay referred to dismissively as “endless writhings” might instead be seen as the actor’s solo cadenzas within this repeated gestural frame, as Walthall’s body pauses but his face moves rapidly and plastically through a series of minute transformations that signal the progress of the disease. As the film progresses to its conclusion, the writhings become more comprehensive, to be sure, but the continuum from first twinge to final collapse at the end of the film is impressive. What Walthall “gets across” to the viewer is a general affective horror, not plot detail, and to judge from the popular contemporary reactions in the fan magazines, the writhings were a feature, not a bug. Perhaps the impatience of today’s viewers with the frequent repetitions of a seemingly identical gesture is an anachronistic response, an imposition of the standards of narrative economy onto a system designed instead for the appreciation of expressivity.

Paratexts: Elaboration or Remediation? The historical sources presented above indicate that the substitution of an expressive code for a communicative code (whether actual or pantomimed speech) clearly satisfied those coming to see a Walthall film, but what of those looking for an Ibsen film instead? While our examination of the transitional screen acting context of the early 1910s has suggested ways of recovering the lost pleasures of gestural virtuosity, questions remain about this film’s tether to the dramatic plotting of the original and whether it seemed important to communicate that to the audience as well. As has been mentioned, the lack of sustained insider

discussion of plot differences in the trade press suggests that promoters cared or knew little about Ibsen’s originals, and even those who, like Vachel Lindsay, took pride in their knowledge of the dramatic canon seem to have understood their position as exceptional. When Lindsay mentions, for example, that the film of Ghosts had been “furiously denounced by the literati” (2000, 106), he was also marking that response as elite, suggesting indirectly that divergences from a frankly unfamiliar original were unlikely to concern most viewers. Nevertheless, there seems to have been a nagging sense of obligation to that original text that surfaces in the paratextual discourse about the film. That is, if the 1915 Ghosts had given itself over entirely to the display of virtuoso expressive gesture, one wouldn’t find such a proliferation of textual materials related to the film. In this regard it is worth remembering that films of the silent era have been unnaturally isolated in the archive as discrete objects. In their original performance context, they were projected along with other films and musical accompaniment, and films of the early teens also often relied on what we now would regard as extra-filmic narrative support – plot summaries in printed souvenir cinema programmes and story elaborations in fan magazines – but which at the time are likely to have been considered part of the same media environment, as their archival isolation had not yet occurred (Singer 1993; Sandberg 2001). We can see evidence of this paratextual practice around the time when Ghosts was released as well, for the trade and fan magazines were full of ekphrastic narrative forms. It is certainly possible to see this interest in “short stories” of the films as an indirect admission on the part of exhibitors that the cinematic narration of dramatic texts still felt incomplete in its visual delivery without full access to the dialogue. But rather than automatically seeking an explanation in this narrative-deficiency model, it may be interesting to note the pivot from adaptation-translation models that occurs when one regards these paratexts not as stop-gap narrative crutches but as a parallel elaboration of the story world of both play and film in a wider media environment. An advertisement in Motion Picture Magazine from 1916, for example, seems to suggest that these short stories were taking on a role of their own, untethered from the films that inspired them, around

the time of Ghosts’ release, and, in fact, one can find just such a promotion of a “Film Story” derived from Ghosts in the British fan magazine Pictures and the Picturegoer two months after the film’s initial release. Entitled “The Inherited Burden” (which was also the title of the Ghosts film itself in its British distribution), this three-page short-story version elaborates on the adapted plot in a way the film cannot given its limited use of dialogue, even as it repurposes stills from the 1915 film as supporting illustrations for the story (Fig. 4). It is worth emphasising here the complicated chain of textual transformations that led to this printed version of The Inherited Burden: the story is credited in the fan magazine to Norman Howard, but the story’s masthead title also traces the material back to both Ibsen (“Based on the celebrated play ‘Ghosts’”) – and the film – (“Adapted from the Majestic Production”) (Howard 1915, 368). Lest we persist in thinking simplistically about adaptation, it is worth emphasising that, technically speaking, the latter example announces itself as an adaptation of an adaptation, but at that point it might be best to let go of all hierarchies of originals and derivatives and to begin to see this in terms of the simultaneous circulation of similar materials, because this “short

Figs. 4a–b. Two of the three pages from the paratext “The Inherited Burden”. Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library.

story” contains at least as many traces of the drama as of the film. Note, for instance, the compulsive use of appositional adverbs in this prose elaboration of the film’s plot. As we read here, Mrs Alving repeats “critically”, Manders replies “courteously”, Mrs Alving returns “smiling”; Helen echoes “huskily,” etc. The comma-plus-adverb formally mimics the way stage directions appear on the page in a drama, an effect especially noticeable in the short-story version due to its conspicuous repetition, but also because there is of course no possibility of delivering dialogue “huskily” in a silent film since it is precisely the aural quality of the voice that cannot be conveyed – that is an effect for the page. It is as if the repressed dialogue and stage directions from the play return with a vengeance in this “film story”, which, unlike most actual short stories, consists almost exclusively of speech and no other forms of narration. The “story” here is mostly dialogue in a prose package, supplemented by images taken from the film. In this way it is neither drama nor film but a third thing – yet another version of Ghosts. Another example gives further evidence of the wider textual activity circulating around the 1915 Ghosts. A one-page prose summary of Ghosts, again from the Mutual Corporation’s promotional Reel Life, includes an extensive dialogue section from the scene in which Oswald returns home from Paris (1915c). (The film, by contrast, includes exclusively the following intertitles in this middle section of the film, with no dialogue: “Oswald’s return to his home”/ “The doctor makes an examination: He recognises the taint but conceals the truth from his patient”/ “As the days go by.”) In the prose version of the story, however, we get dialogue that sounds much more like it is coming from Ibsen’s play:

“Mother!” cried the young man at last, “I’ve something to tell you. I cannot go on hiding it from you!” Helen showed alarm. “I could never bring myself to write to you about it,” he hurried on. “And since I’ve come home—I feel such a terrible dread! The everlasting gloom of this Norway country—will the sun never shine again?” “Oswald,” whispered the mother, seizing him by the arm, “what is the matter? You are fatigued? You are not ill?” “It’s not an ordinary fatigue. No, and I’m not what is commonly called ‘ill’, either.” He clasped his hands above his head. ‘Mother, my mind is

broken down—ruined—I shall never be able to work again.” He buried his head in her lap, sobbing heart-brokenly. (ibid.)

And in fact, it may not be surprising to discover that it is coming from Ibsen’s play – quite directly from William Archer’s English translation of Ibsen, the one that would have been most readily at hand for a trade magazine film journalist on assignment to recreate Ibsenian dialogue for the short prose paratext of the film, which as mentioned would itself have been of no help whatsoever as a source for quoted speech. These lines from the 1906 Archer translation, however, clearly served the anonymous Reel Life journalist in 1915 very well:

OSWALD. [Sits down.] There is something I must tell you, mother. MRS. ALVING. [Anxiously.] Well? OSWALD. [Looks fixedly before him.] For I can’t go on hiding it any longer. […] OSWALD. [As before.] I could never bring myself to write to you about it; and since I’ve come home— […] OSWALD. […] I’m not downright ill, either; not what is commonly called “ill.” [Clasps his hands above his head.] Mother, my mind is broken down—ruined—I shall never be able to work again! [With his hands before his face, he buries his head in her lap, and breaks into bitter sobbing.]8 (Ibsen 1906, 243–45)

8 OSVALD sætter sig

Nu må jeg sige dig noget, mor.

FRU ALVING spændt Nu vel! OSVALD stirrer frem for sig For jeg kan ikke gå og bære på det længer. […] OSVALD som før Jeg har ikke kunnet komme mig for at skrive dig til om det; og siden jeg kom hjem –[…]

OSVALD […] Jeg er ikke rigtig syg heller; ikke sådan, hvad man almindelig kalder syg. (slår hænderne sammen over hodet) Mor, jeg er åndelig nedbrudt, – ødelagt, – jeg kan aldrig komme til at arbejde mere! Han kaster sig med hænderne for ansigtet ned i hendes skød og brister i hulkende gråd (Ibsen 2008, 472–473).

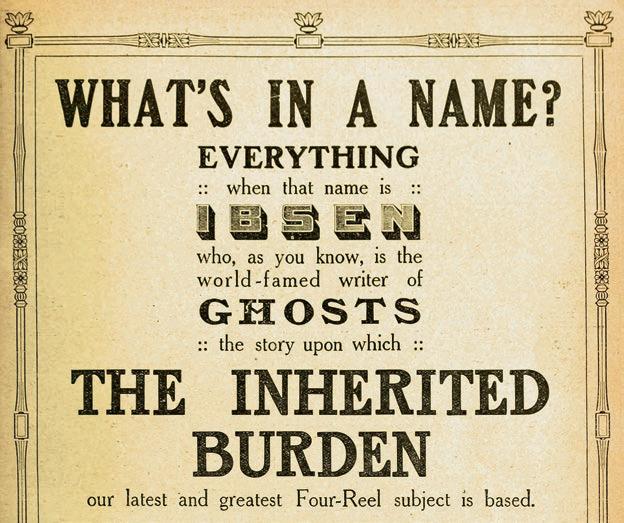

This little forensic reconstruction of sources is not undertaken in the spirit of detecting plagiarism but to underscore this rendering of Ghosts as at the very least a triangulation between the film, the play, and the promotional prose. As the conventions of film writing grew to the point where permanent staff could be hired to produce such reading material for each issue that could be recognised within its own discursive niche, there were suddenly Ghosts aplenty in circulation in the summer and autumn of 1915. What conclusions might one draw from this circulation of materials between the drama, film, and magazine paratexts? For one, it confirms the productivity of thinking about adaptation as an ongoing “transpositional” and “textualizing” process (Sanders 2016, 22; 207) rather than as an issue of fidelity, as that would not account for the several ways in which viewers and readers encountered Ibsen’s Ghosts in 1915. For some who encountered the synopsis or the short story in the fan magazines, this was conceivably their introduction to Ibsen, one that led back both to the film (through the still images) and perhaps to the play (through the quoted dialogue) simultaneously. The “para” in paratext, in other words, places this fan magazine prose “next to” both film and drama in equal measure. In fact, this image from another fan magazine in 1915 (Fig. 5) shows just this phenomenon, the way that all of these mediations were simply gathered under the name “Ibsen”: “What’s in a name? Everything, when that name is Ibsen” (Pictures and the Picturegoer, 1915). Rather than view this as another simple case of film’s crass borrowing of prestige from the world of letters, it might be useful to regard it in this way instead: in 1915, “Ibsen” was the name of a media constellation. The unidirectional model of literature-to-film adaptation doesn’t account for the complexity of these transactions and assumes too much about the essential qualities of dramatic literature, which as we have seen get dispersed across these written paratexts in several different ways. But the bigger problem seems to be the way that the understanding of adaptation makes the failure or unsuitability of Ibsen drama the main story of its relationship to film. That hierarchical literary prioritisation of dense theatrical dialogue prevents us from seeing many other

attractions evident in the film: everything from an actress’s view of “pictures that think” to the ways in which audiences appreciated virtuoso gesticulation as a kind of extreme sport that one could track across Henry Walthall’s various madness films of the mid-teens and to the pleasures of “fan-reading” the films in short-prose form. If, in this film’s original horizon of reception, the word “Ibsen” functioned more as the name of a media constellation than of a canonical author, then it seems safe to claim that there can indeed be a good “Ibsen” film – or at least a historically intriguing one.

Fig. 5. At the height of the “ghostly” summer of 1915, this advertisement ran in Pictures and the Picturegoer. Courtesy of the Media History Digital Library.

Bibliography

Brewster, Ben and Lea Jacobs. 1998. Theatre to Cinema: Stage Pictorialism and the Early Feature Film. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Elliott, Kamilla. 2013. “Theorizing Adaptations/Adapting Theories.” In Adaptation Studies: New Challenges, New Directions, edited by Jørgen Bruhn, Anne Gjelsvik, and Eirik Frisvold Hanssen, 19–46. London: Bloomsbury.

Englund, Hilda. 1913. “Ibsen Dramas on the Screen.” Exhibitors’ Times, 31 May:14.

Hanssen, Eirik Frisvold. 2017. “Silent Ghosts on the Screen: Adapting Ibsen in the 1910s.” In The Oxford Handbook of Adaptation Studies, edited by Thomas Leitch, 154–78. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harrison, Louis Reeves. 1916. “Creative Method—Ibsen.” Moving Picture World, 16 September:1804.

Hines, Dixie. 1926. “Ibsen and Hilde Englund.” New York Times, 28 March: n.p.

Howard, Norman. 1915. “The Inherited Burden.” Pictures and the Picturegoer, 14 August:368–70.

Ibsen, Henrik. 1906. The Collected Works of Henrik Ibsen. Vol. VII: A Doll’s House; Ghosts. Translated by William Archer. London: William Heinemann, Ltd.

———. 2008. Henrik Ibsens skrifter 7: Samfundets støtter; Et dukkehjem; Gengangere; En folkefiende, edited by Vigdis Ystad. Oslo: Aschehoug & University of Oslo.

Lindsay, Vachel. 2000. The Art of the Moving Picture. New York: The Modern Library.

Mayer, David. 2009. Stagestruck Filmmaker: D.W. Griffith and the American Theatre, edited by Thomas Postlewait. Studies in Theatre History and Culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Motion Picture Magazine. 1915. “Letter to the Editor.” October:163.

———. 1916. “The Edwin Booth of the Screen.” February:140.

Movie Pictorial. 1915. “Henry Walthall—Master Emotionalist.” 15 September:14–15.

Münsterberg, Hugo. 1916. The Photoplay: A Psychological Study. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

Pearson, Roberta. 1992. Eloquent Gestures: The Transformation of Performance Style in the Griffith Biograph Films. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Pictures and the Picturegoer. 1915. “What’s in a Name?” 17 July:299.

Proctor, George D. 1915. “Ghosts.” Motion Picture News, 29 May:67.

Reel Life. 1915a. “Stories of the New Photoplays.” 8 May:8.

———. 1915b. “Real Tales About Reel Folk.” 8 May:25.

———. 1915c. “Ghosts.” 15 May:16.

———. 1915d. “Where the Movies are Made.” 15 May:22.

Sandberg, Mark B. 2001. “Pocket Movies: Souvenir Cinema Programs and the Danish Silent Cinema.” Film History 13:6–22.

———. 2005. “Multiple–Reel Feature Films: Europe.” In Encyclopedia of Early Cinema, edited by Richard Abel, 452–56. New York: Routledge.

Sanders, Julie. 2016. Adaptation and Appropriation, 2nd edition, The New Critical Idiom. London: Routledge.

Singer, Ben. 1993. “Fiction Tie-ins and Narrative Intelligibility 1911–1918.” Film History 5:489–504.

Thompson, Kristin. 1985. “The Formulation of the Classical Style, 1909–28.” In The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style & Mode of Production to 1960, edited by David Bordwell, Kristin Thompson, and Janet Staiger, 155–240. New York: Columbia University Press.

Turim, Maureen. 1989. Flashbacks in Film: Memory & History. New York: Routledge.