11 minute read

VALE JAMES MOLLISON, AO

20 March 1931 – 19 January 2020

James Mollison, the founding Director of the National Gallery of Australia, spent more than two decades building, shaping and carefully nurturing the national collection. Among Australian art’s most admired figures, James will always be remembered for his foresight in acquiring Jackson Pollock’s Blue poles 1952 and his extensive input into architect Col Madigan’s design of the building, among many other incredible achievements. We pay tribute to James with an extract from his conversation with Anne Gray, former Head of Australian Art, from the 2003 publication Building the Collection.

Advertisement

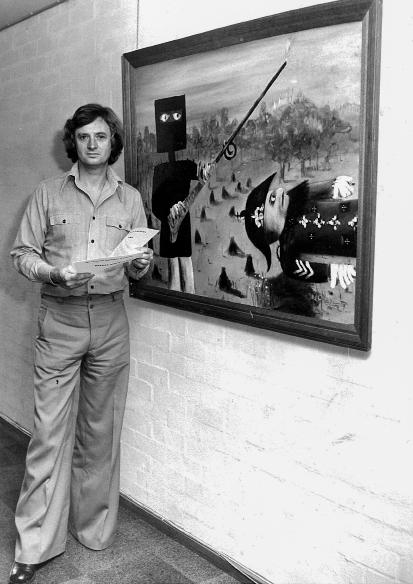

Above: Founding Director James Mollison pictured in 1975 with Sidney Nolan’s Death of Sergeant Kennedy at Stringybark Creek, 1946, enamel on composition board, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, gift of Sunday Reed 1977 © National Gallery of Australia Photo with permission of The Canberra Times Opposite (left to right): the founding Director holding a staff meeting at the former NGA facilities at Fyshwick; Mr Mollison and art critic Robert Hughes inspect Blue poles 1952 when it first arrived in Australia Page 50: Mr Mollison escorts Prince Charles around the National Gallery

The National Gallery’s Australian art collection is now one of the best collections of Australian art. You started with the Commonwealth collection but nothing much else. It was a huge job. How did you approach building the collection?

I followed instructions from government – through the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board – to put together a definitive collection of Australian art. I have to qualify that; the then Art Advisory Board thought that Australian art comprised paintings mainly; sculpture got a small look in, prints and drawings were of no interest really, nor were the decorative arts. But they did ask me to put together the finest possible collection of Australian work for the Gallery that was then to open in 1976.

You were ahead of your time in recognising that prints and drawings, decorative arts and photography were an important part of the whole story. Had you had seen examples of this in collections elsewhere?

I grew up in Melbourne. The National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) contains marvellous prints and drawings and a collection of decorative arts at least equal in quality to the collection of paintings. It never occurred to me that some things were better art than others because of their category.

How did you persuade the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board of this?

I waited. I can remember putting a proposal to the Board that we set aside $2,000 a year from which we would buy a comprehensive collection of Australian prints. For $100 you could get a Margaret Preston print or the rarest impression of Norman Lindsay. But they said, ‘No. We will do without prints and drawings in the collection. You get back to work and find us the paintings we want.’

So you just waited until the time was right?

I was prepared to wait.

How did the Board find you?

I’d known Daryl Lindsay from the time I was about 16 when I visited him to ask for a job. He was then Director of the NGV. When I was appointed to the Ballarat Art Gallery as Director in 1967, Daryl was overseeing the installation there of the sitting room from Creswick, the Lindsay family house. He offered me a job that I refused – six months in India with an exhibition of Australian art. The exhibition had already arrived and had been lost. The paintings were finally discovered on a dock, with all the useful timber from the crates taken.

Eventually a position was advertised. The job was to create an Australian collection in readiness for the Gallery opening and to look after Australian exhibitions that went overseas. I was very busy and happy in Ballarat and never thought of applying. When it was found difficult to fill the position I was asked to go to Canberra to talk to the appointment committee. With no great sense of looking forward to it, I took the day off and went to Canberra to talk about the need to get somebody who knew what museums were, knew what art was and where to find it, knew what exhibitions were, knew how to put them together. To my surprise I was asked if I would like the job. I said no.

Bill Cumming - who was the Prime Minister’s Department officer on the Commonwealth Art Advisory Board – suggested we play a game of ‘What if’. ‘What would we need to pay you to get you to come and work here?’ I said, ‘I’m not going to come to work in Canberra.’ He said again, ‘What would we need to pay you?’ I doubled the acceptable salary I was being paid at Ballarat. ‘That’s no problem’, he said. ‘What else would you need?’ And I said, ‘Well I’ve been talking to you about how collections are formed and shown in museums, and the need to know about overseas venues for exhibitions, the need to know what is in every Australian collection. If you want something useful in Canberra there would have

to be aeroplane tickets around Australia available on a weekly basis.’ Heads nodded; so I added, ‘and it would be necessary to spend at least three months each year overseas’. Then I heard, ‘Well the government has access to two airlines, that wouldn’t be a problem.’ My heart thumped. I was asked, ‘What else?’ I had been collected by a Commonwealth car in Ballarat and taken to the airport, met by another in Canberra and taken to the meeting. I said, ‘I would need a car and driver at all times I was working.’ They nodded; so I added, ‘wherever I was in the world’. ‘We will send you back to the airport in a Commonwealth car’, they said. And I said, ‘No, I’ll walk.’ So I walked to the airport from East Block in a sort of dazed state, and immediately went home and told my folks what had happened. Dad said, ‘They seem to want you son.’

It took the best part of a year to create the position. I was appointed in October 1968. The Board quickly realised that it would be possible to present a very wide picture of art in Australia – starting with the Rex Nan Kivell collection at the National Library (which was then considered material for a future National Gallery) through to contemporary art. They also appreciated that I have never believed my likes and dislikes are important in terms of doing a job. If it’s there, and there at a sufficient level of interest and excellence, it should be represented. Some few months into the job I was thrown, because the Board asked me to gather together a collection of, say, 25 really contemporary works for them to look at. I showed them contemporary art as it was available at that moment in Sydney. And they couldn’t look at it. What they were thinking of as contemporary were works by Boyd, Nolan, Tucker and Williams. To me these were established artists - contemporary is something new, something about which I don’t already know very much. At the end of the day the Board said, ‘There are 25 things here. Let Mr Mollison make up his mind which ten he’ll keep.’ Then they asked me to find the category of works they really had in mind.

So what did you do when they said to go and get those works?

Two things happened. I realised that if the national collection were to gain quick recognition it had to contain works that either had been reproduced or would be used as reproductions once they were in the public domain. So I went through everything ever published on Australian art and we set about bringing that known material into the collection. Then looking in the stores of the State collections I saw that these had been put together by people who were interested in the establishment figures in Australian art. The Canberra collection could be made to look different by representing modernism throughout the country. So I went to the artists who had made history from the 1930s forward. They were still around in the 1960s – people in Sydney like Grace Crowley and Ralph Balson and, in Melbourne, Arthur Boyd and Albert Tucker - and I began long negotiations with them to release works they had deliberately retained.

You’ve a huge reputation for having trained and fostered and encouraged a lot of people. Who were your own mentors?

Daryl was certainly one of them. The old-fashioned way in which I hang exhibitions comes from Daryl – a big painting in the middle and a pair either side. Lucy Swanton was a truly big influence on me. She showed me how to listen to artists, to be the recipient of their secrets - and their unkindness if they wanted, or their anger, or whatever – but never to pass this on. Rudy Komon also. The art world thought he never had an unkind word to say about anybody. And John Reed, at his successive Museums of Modern Art. I didn’t know until John told me a couple of years before Sunday died that she liked me. I always found her so curious. After I arrived at the house she would appear from somewhere. She would sit with us, characteristically with her shoulder towards me, and never say anything very much. Then she would wander away. I do wish I had known that she liked me because I could have let her see that I liked her back.

What prompted Sunday Reed to give Nolan’s Ned Kelly paintings to the Gallery?

They saw that it was the right place for them to be. The paintings were in the house at Heide, on show two or three at a time. The rest were in the crates in which they had travelled to Europe, stacked where cats and possums could pee on them. We had to rid them of the smell.

The choice would have been giving them to Melbourne or giving them to Canberra? Knowing of your vision for Canberra they would have recognised how important it was for the series to go there, to be part of a national collection.

I have trouble with my ‘vision for Canberra’. I was just working at a job that I had been asked to do.

Right from the opening, Aboriginal art was given prominence, and it was an important step to integrate Indigenous art with works by other Australians.

As soon as I realised that people did not want the Australian hang to represent the two streams of Australian art, I decided to make it obvious to them that they had to think about this very carefully.

When did you develop your personal interest in Aboriginal art?

From the time I was a youngster archaeology was an interest. I am truly curious about other beliefs, other times, other places, and I discovered Fred McCarthy’s Australian Museum book on Aboriginal Decorative Art in 1948. I was also looking at Aboriginal works in the stores of the State Museum, and with an art school friend had tidied Baldwin Spencer’s glass slides of his Central Desert trips that were then in a terrible muddle, and broken. I was 19 when I discovered that the Methodist Missionary Society had an upstairs sales outlet for Aboriginal things in Sydney quite near the Town Hall. I think I bought the four shilling rather than the four guinea items. I would come back from there with bark paintings.

There’s a story about you visiting Kakadu to expand the direction of the Aboriginal art collection.

I spent untold hours talking with senior men, sitting on logs, telling them what they already knew – that is, that in Canberra we were not interested in just one bark painting. What we wanted from them was their story, their business. We should have the full representation of all the business to which the artist is the key, the holder of tradition. In due course artists came to be pleased that Canberra was the keeping place for their material; but to begin, the idea had to be discussed and agreed.

Would you discuss your ideas on collection building?

Museum work to my mind is ‘target’, ‘work on it’, ‘next target’, ‘complete the first one’, ‘work on the second’, ‘next target identified’ – it goes on forever. Every curator has plans for acquisitions and exhibitions years ahead. Projects can always be delayed for something more ambitious. Work must progress on a week-by-week basis over many projects. You must also collect information that explains objects. I believe it is absolutely essential that if the sketch for anything in the collection comes up, you must get it. You have to have the sketchbook; you have to have the prints - things that complement. ■

See the world through artist’s eyes and go behind-the-scenes at the National Gallery. Find connection and inspiration online.

Conservator David Wise analyses Jackson Pollock’s iconic work Blue poles 1952