10 minute read

GARDEN OF TREASURES The history and highlights of our Sculpture Garden

GARDEN OF TREASURES

Lucina Ward explores the history and highlights of our art in landscape.

Advertisement

Winter, Spring, Summer ... a little-known fact about the National Gallery Sculpture Garden is that its layout is structured around the four seasons – but the Autumn section was never created.

The original garden, designed by Howard Hughes and Associates and planted over 1981–82, stretches over three hectares from the Gallery’s north to Lake Burley Griffin. Its layout uses many of the design principles of Col Madigan’s architecture, creating synergy with the National Gallery building.

Within the garden a series of distinctive environments complement the sculptures, from the axis path which stretches from the building to the lake, or the intimate ‘rooms’ created with foliage and filtered light.

Fringed by deciduous trees along the shore, the local species of the Sculpture Garden give it a distinctly Australian flavour. The slatepaved forecourt area is the Winter Garden, while the casuarina forest and marsh pond comprise the Summer Garden — that is when the area near the lake with its spring-flowering banksia, hakeas and grevillias is best seen. On the southern side, where the new Australian Garden opened in 2010, the terraced lawns combine with layered plantings and waterways. Eventually, it is hoped, the gardens will merge to encircle the entire building.

Winter Garden: highlights then and now

Auguste Rodin is regarded as the father of modern sculpture and The burghers of Calais (above) is one of his best known works. The fourteenth-century burghers, six leading citizens of Calais in France, sacrificed themselves to Edward III of England to save the town. The figures convey the angst of their situation: taunt bodies, large expressive hands and gestures. As the artist intended, the burghers are at level so the viewer can feel their struggle, and see details such as the faces and the proffered key.

Emile Bourdelle’s Penelope (centre) watches over the pathway to the lake. Her husband Odysseus has left for the Trojan Wars and she keeps wait for him over 10 years. The sculptor took almost as long to complete the work, developing a series of studies before creating the final version. Penelope no longer holds a spindle — a reference to the unfinished tapestry, woven by day and unravelled at night, to avoid would-be suitors — but the sculpture’s mass, curve of the figure and texture of her robe convey a sense of her story.

Angel of the North (life-sized maquette, right) is a 1:10 model of Antony Gormley’s most discussed work: a 20-tonne figure that towers over a motorway near Gateshead in England’s north east. While the scale of the model here is

smaller, the materials are the same, and hint at centuries of coal mining in England’s industrial past. Angels can be a symbol of hope and this figure was cast from the artist’s body, with the wings made separately on a wire frame.

Spring Garden: highlights then and now

The enormous curve of steel which is Clement Meadmore’s Virginia 1970 (above) defies gravity. The work is made from a thin shell of welded steel and is actually hollow; with upturned ends, and only two points of contact with the ground, it looks light and flexible, despite weighing over eight tonnes. The artist dedicated this work to a fellow expat artist Virginia Cuppaidge, whom he had met in New York, and the sculpture was shipped from the United States in four parts and reassembled here.

The black beams of Mark di Suvero’s Ik ook 1971–72 — the title is ‘me too’ in Dutch —

direct viewers to explore other parts of the Garden. The sculpture’s geometric forms are reminiscent of cranes on a building site or the heavy-duty machinery of a dockyard. Di Suvero creates tension and balance through sophisticated use of modern building materials and engineering techniques: he transforms I-beams and cables into gigantic calligraphic statement in three-dimensions.

A group of tutini or Pukumani poles (below) inhabit one of the elevated ‘rooms’ of the Spring Garden. An important funerary ceremony of the Tiwi people, a Pukumani ceremony involves singing, dancing and making tutini from ironwood tree trunks. When originally made by the artists from Melville and Bathurst Islands, these were covered

in traditional designs associated with the Ancestors Purukaparli, Tapara and Bima who first brought death to the world. Deliberately allowed to age, they are then abandoned and left to return to the earth.

The work of Canadian artist Cal Lane is seemingly full of inherent contradictions. For Domestic turf 2012 she takes a standard maritime shipping container and ‘carves’ it into a gorgeous, fairy-tale-like abode adorned with curlicues, flowers and a range of animals. The delicacy of Lane’s doilies contrasts with the machine quality of her readymade industrial form. Originally shown on Cockatoo Island as

part of the 2012 Biennale of Sydney, Domestic turf has found a new home in a clearing of eucalypts in the Spring Garden.

Summer Garden: highlights then and now

The sculptural traditions of Vanuatu emphasise the human figure as seen in these lali, or slitdrums (left), carved from dense hardwood. Heads and facial features are rendered in detail; the rounded body sections of the drums were originally painted. Drums of this type are used to perform rites for the ancestors. Commissioning a drum and overseeing its completion are a major achievement, reflecting both the earthly and spiritual power of the family within the village.

The polished stainless-steel surface of Bert Flugelman’s seven Cones 1982 reflect and distort the ground, sky and surrounding vegetation. Viewers become participants, their reflections elongated or made squat as they move around

the sculpture: the seven cones appear to join the dance, tilting and pirouetting across the clearing. Flugelman’s sculptures feature in many public spaces — and are sometimes concealed — in several Australian cities.

One of the most haunting works of art in the Garden is Heads from the North by Dadang Christanto (above). Partially biographical, the work refers to the artist’s experiences of social and political injustices growing up in Indonesia. The 66 bronze heads remember the victims of violence following an unsuccessful military coup in 1965–66, including Dadang’s father. The artist was eight-years-old when his father disappeared and, when the heads were installed in 2004, he created a performance to pay his respects.

Gallery entrance and forecourt, The Australian Garden and Fiona Hall

Fern Garden

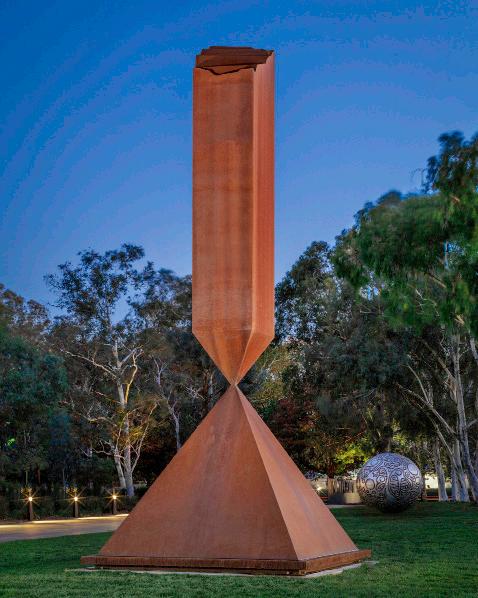

The grassed section near the main entrance is dominated by two geometric works of different styles and intentions. Barnett Newman’s Broken obelisk 1963/67 (below) is powerfully symbolic and acutely political, one of the most recent additions to the Sculpture Garden. The work combines qualities of ancient forms with the

geometry of modern architecture and materials. Eran 2010 (top right), by artist and indigenous elder Thanakupi, was commissioned for the National Gallery and shows crocodiles, kangaroos, lizards, eggs and birds swarming across a silver globe. Described as being made from ‘the sands of country’, the bauxite-rich earth of Weipa in North Queensland, Eran is ‘river’ in the artist’s Thaynakwithlanguage.

On the grassed terraces of the Australian Garden is George Baldessin’s Pears – version number 2 1973 (below), an elegant and slightly surreal still life. The oversized fruit seem like a group of friends, leaning towards each other as if conversing, or sharing a joke. The pun within artist’s title, too, captures the ideas central to still life and momento mori traditions: denial, desire, eroticism, penitence and death. The Australian Garden is also home to Within without 2010 (right), a Skyspace by James Turrell, another work which plays with perception. Visitors enter via a long, sloping

walkway, and once inside the large pyramid, encounter a stupa of Victorian basalt set at the centre of a turquoise pool. Inside the stupa is the viewing chamber open to the sky and where, at dawn and dusk, a special light shows throughout the year, see nga.gov.au/turrell.

Near the above-ground carpark on the Gallery’s eastern side, a wrought-iron gate leads to Fiona Hall’s Fern garden 1998 (above). This sheltered oasis, framed by 23-metre high bush-hammered concrete walls, features more than 50 tree ferns, Dicksonia Antarctica, planted as mature trees and now at least 200-yearsold. Hall’s garden, set out in a spiral with waterspouts and benches at key points, refers to the environment, and cycles of birth, life and death. ■

Lucina Ward is a Senior Curator

All works National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Page 54: Robert Stackhouse, On the beach again 1984, bronze, purchased 1983 © Robert Stackhouse Page 55: (top to bottom) the garden was planted over 1981–82. Bert Flugelman, Cones 1982, polished stainless steel, commissioned 1976, purchased 1982 *© Bert Flugelman; Henry Moore, Hill arches 1973, bronze, purchased 1975, Reproduced by permission of the Henry Moore Foundation *© Henry Moore; Mark di Suvero, Ik ook 1971–72, painted steel, purchased 1979 © Mark di Suvero, courtesy of the artist / Spacetime C.C. Page 56: Then and now: Auguste Rodin, Nude study for Jean d’Aire 1885–86 cast 1973, bronze. The burghers of Calais c 1885-86 cast 1974, bronze, purchased 1974; Emile Bourdelle, Penelope 1912, bronze, purchased 1976, Clement Meadmore, Virginia 1970, weathered steel, purchased 1973 *© Clement Meadmore; Antony Gormley, Angel of the North (life-size maquette) 1996, cast iron, Gift of James and Jacqui Erskine 2009 © Anthony Gormley Page 57: Then and now: Mark di Suvero, Ik ook 1971–72, painted steel, purchased 1979 © Courtesy of the artist and Spacetime C.C.; Bert Flugelman, Cones 1982, polished stainless steel, commissioned 1976, purchased 1982 *© Bert Flugelman; Willy Taso and Tofor Rengrengmal, Slit-drums from Malampa Province mid 20th-century, wood, purchased 1972, *Mickey Geranium Warlapinni, *Deaf Tommy Mungatopi, *Boniface Alimankinni, *John Baptiste Pupangamirr, *Alan Papaloura Papajua, Tutini c 1979, natural pigments on ironwood, purchased 1979

Opposite: Dadang Christanto, Heads of the North 2004, cast bronze, purchased 2004 © Dadang Christanto. Courtesy of Nancy Sever Gallery, Canberra Walkway to front entrance showing Thanakupi (Dhaynagwidh/Thaynakwith people), Eran 2010, aluminium, acquired through the Founding Donors’ Fund 2010, © the estate of the artist, licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd and Barnett Newman Broken obelisk 1963/1967/2005, weathering steel, gift of the Barnett Newman Foundation in honour of Dr Gerard Vaughan AM 2018 *© The Barnett Newman Foundation; James Turrell, Within without 2010, Skyspace: lighting program, plaster and painted concrete, granite, marble; concrete and basalt stupa; water, earth, landscaping, purchased with the support of visitors to the Masterpieces from Paris exhibition 2010 *© James Turrell; George Baldessin, Pears - version number 2, 1973 corten steel: 7 forms, purchased 1973 *© George Baldessin; Fiona Hall, fern garden 1988, sculptures, tree ferns, river pebbles, granite, steel, concrete, copper wood mulch, water. Purchased with the assistance of Friends of Tamsin and Deuchar Davy, in their memory, 1998 © Fiona Hall This page: Neil Dawson, Diamonds 2002, aluminium extrusion and mesh painted with synthetic polymer automotive paints, stainless steel fittings and cables Commissioned 2002. Purchased with the assistance of ActewAGL 2002