16 minute read

Miss Dillon’s Gas Company Kendric W. Taylor

Dillon family wedding anniversary, circa 1903. May Dillon(back row, third from the left);author’s mother,Frances Veronica Dillon (front row, fourth from the left).

Miss Dillon’s Gas Company

Advertisement

By Kendric W. Taylor

It’s the first day of summer as I write. A dreadful winter is past, and warmly awaited June is here -- a month of endings and beginnings – especially graduations, which are both. This year’s commencement celebrations included participation of one of our editorial number – our publisher – who had the pleasant task of attending, with his wife, two of their granddaughters’ college ceremonies: for a journalist and a lawyer. No doubt others of us on the Natural Traveler masthead – from Maine to Malaysia -- have proudly looked on as one of the young women in their families completed one journey while embarking on the next: one lofty life pinnacle achieved, surely to be followed by others. I myself am closely following the path of a granddaughter, who just completed her college freshmen year, and whom I am quite certain is odds-on to be the first red-haired woman president of the US.

But this was not always so -- as history, and any female, will tell you. Opportunities have improved, yes, with scores of women prominent in almost every profession, but it doesn’t take an historian to remind us it has been a struggle that took centuries to get from there to here, or a pundit to remind us that a complete breakthrough is far from complete: just look at salary inequities. It took immense courage and determination for women to even get out of the house, much less manage to get an education, to get a

decent job, and to begin that climb to even achieve equality, much less gain the top.

Look back in history: who were the most famous women to come to the mind in the US in the 20’s and 30’s? Mostly movie stars, occasional athletes and spouses of famous men: the 20’s had Mary Pickford and Zelda Fitzgerald (Mrs. F. Scott), Gloria Swanson and Gertrude Ederle, first woman to swim the channel (I had to tell you that one); while Ginger Rogers, Amelia Earhart and Eleanor Roosevelt were prominent female headliners in the 30’s. This is solely a family remembrance, and not intended as a scholarly work by any means -- an academic treatise by a social scientist– so I am sure there were certainly others at the time -writers, teachers, public health advocates, explorers even, all trailblazers in their own right -- but compared to the enormous potential being wasted, pitifully few.

Of course, women were in the workforce, but doing what? According to the 1930 census, for example, nearly eleven million women, or 24.3 percent of all the women in the country, were gainfully employed. Three out of every ten of these were in domestic or personal service. Of professional women, three-quarters were schoolteachers or nurses, where they worked at a reduced wage. And, if they were recent immigrants, the sweat shops were always available.

Offsetting this, I am sure many families have stories of someone who made it. In mine, it was my great aunt, Mary Elizabeth Dillon. When she passed away in 1983, The New York Timesdescribed her as “the first woman to be president and chairman of a public utility corporation.” (That’s not only in New York -- but in the U.S. and anywhere else). She was also the first woman president of the New York City Board of Education, and in 1935, Eleanor Roosevelt called her “one of the women she most admired in America for her ‘well-rounded life.’”

Known to her family as ‘May,’ she was also part of the Irish story in this country. Born in Greenwich Village in 1885, back in the days when it was commonplace to see signs in the city reading “No Irish Need Apply,” she was part of a large family that originated here with the arrival from Ireland in 1851 of John Dillon and his wife, Mary Welsh (my great-great grand parents). They settled into Sullivan County, in southern New York State, about 80 miles north of Manhattan. Soon enough, a branch of their offspring moved down to the city itself –more accurately Greenwich Village, and eventually spreading over into Brooklyn and Coney Island. May Dillon was part of this latter group making the move after the turn of the century. She was one of 11 children of Philip J. Dillon, listed in the 1880 and 1900 censuses variously as a brush maker and a postal worker, His wife, Anne Wise Dillon, is listed as a home maker, as are all the females counted that day on those pages.

Back across the relatively new Brooklyn Bridge, one of Philip J.’s sons, George Philip Dillon, my grandfather, had married Mary Jane Maher, herself one of five children whose family owned a carting company. My

mother, Frances Veronica Dillon, was born in 1898 – one of four. George Philip, their father, died in 1907 at age 33 (already with four children, part of a family of hearty Irish boyo’s – who knows what kind of numbers he might have rung up had he lived). Family Disruptions My grandmother, Mary Jane, finding herself with four children and a husband just in the ground (died of the consumption), for whatever reason, decided her best course was to take herself off to upstate Saratoga, famous for its year-round fresh- air treatment of TB. She left the four children (the oldest 9, the youngest 3) with her mother -- also Mary Jane (Maher). This was on 158th street on Manhattan’s upper west side, which already had a house-full of Mahers -- grandchildren left by other relatives – boys in one room, girls in another (the 1910 census lists 11 people: 5 adults and 6 children). This ménage over time also included various aunts and uncles moving in and out, and included at one point, a boarder just arrived from Germany who barely spoke English!

In that house, as soon as the children were old enough, they worked: the boys up early, delivering goods from the local bakery, or newspapers, or whatever else that paid a wage. The girls, too, were sent out to look for work as soon as they were old enough, and at age 12, their education was over. That was it for the two Dillon girls; there was no thought of high school: it was eighth grade and done: go find a job. Despite this, and the fact that my mother never forgave her mother for leaving them there, with her and her sister caring for their two younger brothers, she remembered it as a happy time, with “Nana,” their grandmother, ruling the roost and supplying the love they all needed.

Things were different over in Brooklyn, although money was probably tight as well, with a family that size. But May Dillon had managed not only to attend high school, but when her sister Evangeline left the Brooklyn Borough Gas Company to get married in 1903, she managed to get May to replace her as a secretary. She was 17.

An article in Brownstonermagazine by Susan De Vries, a staff member of the National Trust for Historic Preservation, continued the story:

Mary knew nothing about the gas business, and started out in the office as the “office boy” as she would later call herself. Anything they asked her to do, she did, and over the next few years, she learned everything about the gas business,from billing to operations. She was like an early movie heroine, a pretty, petite and blonde young woman who made her way in a man’s world. More women were eventually hired in the company, but there were very few women like Mary Dillon.

Three years afterbeing hired, Mary had gone from junior clerk to office manager, at the age of 20. By 1912, she knew the gas business inside and out, from top to bottom. She was so knowledgeable that she was selected by the general manager to be his assistant. Seven yearslater, her manager left his position. Mary Dillon was the obvious choice to succeed him. She knew more about Brooklyn Borough Gas than anyone else in the company. But she was a woman, by then a 33 year old unmarried woman. It was unheard of that a woman could manage a gas company.

While the board was fretting over public reaction to a female at the helm, they were having trouble getting a rate increase, the company was facing bankruptcy, and word was going around that they were up for sale. Figuring they had nothing to lose, they gave in, gave her the job, but not the title.

What was even worse, electricity was now replacing gaslight (my mother remembered as a young girl seeing the electric lights going on up along Broadway for the first time). May Dillon didn’t waste any time: she got the rate increase, and immediately began upgrading their infrastructure, including new and better gas lines, which in turn, allowed them to provide higher quality gas to borough families. She also did something that women will do when given the chance – she showed how things could be done better – and with a woman’s touch.

She began running a series of announcements in The Brooklyn Eagle , the borough’s widely read daily newspaper. As the Brownstonerexplained, these were:

Not ads, but simple statements of company purpose and goals, they were reminders of what the gas company meant to Coney Island. Mary Dillon knew that while the gas industry might be thought to be a messy man’s world, it was, in fact, used primarily by the women of Coney Island. Gas stoves and other appliances were taking over the market, and these were women’s tools. These ads, placed in the women’s pages of the paper, were gentle reminders that gas was important and worth paying for.

The stock went up, rumors of a sale faded away, and the specter of bankruptcy disappeared. Now, there was little doubt that she was able to run the company, and in 1924, the Board of Directors announced she was the new vice president and general manager of Brooklyn Borough Gas. May Dillon was running a $5 million company ($85 million today) with 500 employees, serving 170, 000 customers.

Over in Manhattan, the Great War over, and the nation rebounding into the Roaring Twenties, with all their social changes, my mother and her sister were part of a new generation of young women, bobbing their hair, shortening their skirts and flocking to nightclubs for all that wonderful new jazz music, all considered very sinful. They were known as flappers, and while not sinful themselves, they were looked at askance by the proper folks. Squired around the town by the songwriter Irving Berlin, they and their friends no doubt hit all the speakeasies, the dining and dancing palaces, like Reisenweber’s Café, famous for its glamour, late nights, dance floors hot jazz, and, as she told me, going to parties at his place where Berlin would play “his funny looking piano.” Models and Movie Extras

During the war, there had been a portrait in the window of the famous Fabian Bachrach Studio on Fifth Avenue of her sister, Mildred, posed in a Red Cross uniform, which had been all the rage. The sisters weren’t shy about riding that celebrity, modeling for Hattie Carnegie, the popular fashion designer (Lucille Ball later modeled there). They also took the ferry over to Queens to the movie studios, for work as extras. It didn’t last long, especially for Mildred, a war widow with a young daughter, and by the mid-1920’s, both were married to advertising men.

Post-war, May had also been adapting to new times – as the head of a large public utility. She set out to build a state-of-the-art corporate headquarters in Brooklyn: a place where customers could not only drop by to pay their bills, but visit the modern showroom as well, to see the absolute latest in gas-powered equipment (washers, dryers, fireplaces, heating stoves and other gas-fueled appliances). And – there was always time for experts on hand, instructing in new cooking

skills, which included not only recipes, but something else – time management.

Back in the early 1920s, May had joined the British Women’s Engineering Society (WES) in London, and the Electrical Association for Women, which, at the time, were the only such organizations in the world. An early networker, later in the decade, she teamed up with fellow member Dr. Lillian Gilbreth, a leading expert in time and motion studies (a hit 1950 movie, “Cheaper by the Dozen,” was based on her family). Based on May’s ideas, they developed a kitchen built around three basics: a circular workplace, at a uniform height, with the work taking place within the circle, thus reducing the time and effort to put together a meal. This development of kitchen design principles –using gas, naturally -- still underlies much of the kitchen layouts we still see today. It quickly became apparent that, whatever the borough, whether living in a house or an apartment, young marrieds like my mother were not interested in old fashioned kitchens: they had been eyeing those advertisements and they wanted countertops, cabinets and yes, those new gas appliances, the kind they could get in the major department stores.

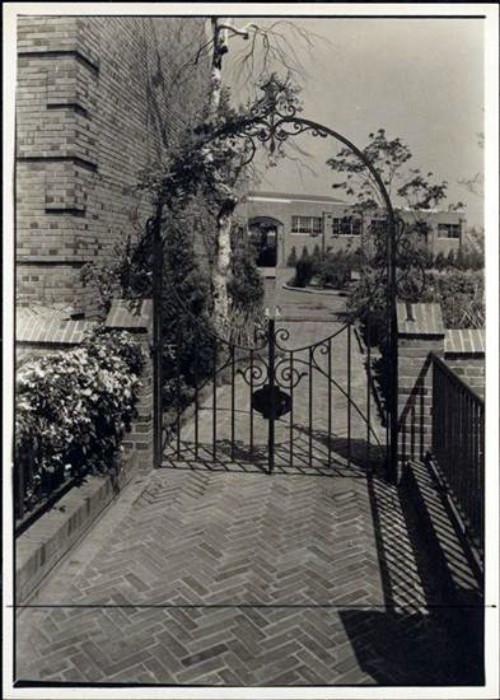

May’s new headquarters was not only beautiful, in an estate-like setting, but definitely appealing to women’s growing sense of place. And, it was a practical gas plant where millions of gallons of were processed and stored. Art Deco in style, not unlike the colossal new Rockefeller Center being built over in Manhattan, it even had its own eye-catching Diego Rivera mural (the Rockefeller’s later got rid of theirs). Not surprisingly, the building won the Brooklyn Chamber of Commerce’s Architectural Excellence Award in 1931. And had a new name -- the Brooklyn Union Gas Company.

Additionally, she also became a member of the governing committee of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, as well as a member of the local school board in Coney Island – and the director of the Brooklyn and Coney Island Chambers of Commerce. Recognizing the paucity of cultural life during the great depression, she organized a summer theater, known as the Theater on Wheels. A few years later, with the advent of World War ll, she was on the Mayor’ s Business Advisory Council and the War Council of the City of New York.

The Dillon family is traceably back to Ireland in the mid-1700’s. Beyond that, it gets murky. Our original here, John Dillon, took up farming, and gained a certain amount of prominence in Sullivan County. Those that moved further south, the new city dwellers, became drovers, many of them, hearty men driving overloaded carts behind teams of horses from the wharfs of New York harbor, over cobblestone streets, delivering goods from all over the world to the city’s

Brooklyn Gas Complex, 1933

shops and markets. The spouses, homebound, kept house, until women like May Dillon began to change all that.

Now of course, the choices for women are virtually limitless. For four years, I provided pickup after school and sports for my granddaughter Annie and her BFF, Máiread -- both Irish descent, honors students, and already awesome-squared. As they fast-tracked their way through school, I found myself marveling at what they and women in general -- including their own mothers -- were accomplishing – juggling work, home, and children – striking balances never dreamed of by past generations. Women now were the ones determining their future – not someone else. Not only equal but taking the lead. I mean, what’s wrong with being George Clooney married to an international lawyer? Plenty of achievement for both. Girls like Annie and Máiread are close on the heels of those women who are right now pushing through the so-called glass ceiling, if not already past it

May Dillon retired in 1949. She had married, but nothing much is known about her husband. She had lived in Vermont, but then moved out to Hawaii. Naturally, May was a family legend, and we were all very proud of her -- but my mother was my hero. She was always reading yet another book –fiction and non-fiction, it didn’t matter, she loved to read, and I got that gift from her. Her favorite employment was a job she had in a bookstore, which provided a constant flow of books for both of us to read. Thrown into the workforce during World War Two, she had a natural bent for sales, and worked at it until they wouldn’t let her anymore. A true autodidact, she never stopped being curious and learning, right up until she couldn’t anymore. When she was very old and dementia had taken her to another place, I’m glad it was to west 158th street, where she thought she was, and had been so happy. She lived to be 94 and was my rock.

The rest of the Dillons became part of the demographics of this nation, migrating out of the city up toward Connecticut and out onto Long Island. Many of the Brooklyn branch chose to stay right where they were, watching the borough rejuvenate itself all around them. They all kept in sporadic touch somehow: it was easy for my mother and her sister, both living in the same town. At any get-together, there would be stories, especially if their two brothers were visiting, huge Irishmen with booming laughs; the youngest would arrive in a chauffeur-driven limousine, to the delight of my cousins who would borrow it to impress girlfriends.

May lived to a wonderful old age, out in Hawaii. A family story was that she was learning a new language, at the end. But before that, she came back to star at a family reunion in New York, organized to honor her. I met her then for the first time. She was very tiny, but that impression quickly faded as you talked with her. Name tags at the event had no practical use really, as it seemed like all the men were named either George Dillon or Philip Dillon, with my father, the proper Englishman, and I the only exceptions. And he was named after his grandfather and I was named after him!

It was a prosperous, well-fed group, mostly sexagenarian, about two dozen people, representative of all the rest of the present family: which now – like many families -- included among their ranks, teachers, lawyers, business executives, bankers, actors, corporate executives, clergy, small business owners, journalists, salespeople, and just plain working people, even a new incarnation of those once called drovers, an engineer on the Metro North railroad -- who promises to honk every time he comes through my town.

You know – the American Dream -- the one that should apply to everyone equally.