17 minute read

Silence in November Kendric W. Taylor

103rd Aero Squadron Spad 13

Le Duc, Le Dauphin et Le Comte de Paris

Advertisement

Silence in November

By Kendric W. Taylor

August 9, 1918 (Near the front)

Dear Old Sport: What a lovely time on our picnic. I’m so glad we were finally able to have it. You looked very fine in your new American uniform. I was quite proud.

I’m moving to a base hospital near S ______s. I feel I can help more, especially now as so many of the wounded coming in from the battlefields are American boys. The hospital in Neiully will continue to forward my mail. In haste, A

October 14, 1918

Dear Old Chap:

A small operating team of two doctors and myself are moving to a Casualty Clearing Station closer to the lines, which are moving so quickly now as the Germans pull back. I am well, tho’ hungry and filthy, and tired, of course. I thrive on the work, and the good I hope we do, altho’ the wounded from mustard gas are especially heart-rending – 600 in the last 48 hours.

This will be over soon, I know, and then we will be together. Hastily, A.

They dived out of a cold November sky, a small flight of three. The two enemy observation balloons grew fat in their sights in the late afternoon light. Lawrence felt cramped and cold in the small cockpit. His knee had taken much longer to heal than anticipated -- in the end there had to be an operation -- and he had not been fit for flying for much longer than expected, not until late summer. But it gave him five happy days with Alex in late July, when she had been given a brief leave between assignments. By that time, he had been accepted as a captain in the Army Air Service, posted as adjutant to one of the American squadrons. He had taken Le Duc d’Orleanswith him. He spent little time on administrative duties, delegating them to a parcel of bored enlisted clerks who required little direction and were resentful of interference. Much of his time was taken up preparing the new pilots for what faced them. The great German spring offensive of 1918 had ended in exhaustion and despair for their General Staff, their shock troops stalled short of Paris, replaced with an inexorable tide in the opposite direction, a series of steady attacks spearheaded in part by the fresh American troops. For the first time since 1914, the fighting climbed out of the trenches and spread over the countryside. As a scout squadron, his group ranged far and wide above the moving battle line, reporting back on the fluid enemy dispositions as their armies retreated out of France. Earlier in the morning, on the day’s first patrol, they had spotted the two observation balloons. He and Albert had discussed tactics during the afternoon, and then called for a volunteer to accompany them. The entire group stepped forward, and he had chosen the most experienced among them, a man he didn’t particularly like, but who had displayed a cool head in the few air combats in which he had participated. They had taken off before dusk for the flight across German lines.

It took the three new Spad 13s nearly 20 minutes to climb to 18,000 feet, where they set a course northward over the edge of the Argonne, generally following the river Meuse. His plan was to overpass the balloon emplacement by some 8 to 10 miles, then swing back to attack from where he hoped they would be least expected. Slipping in nose down, he would switch off his engine a few thousand yards out and take advantage of the Spad’s gliding capabilities to coast in and spring silently on the gasbag, taking the ground and gondola crew by surprise. With the chill quickly setting in, his chest heaved as he struggled to get sufficient oxygen into his lungs and remain alert. Lawrence was grateful their time at this height would be brief. He checked the primitive instruments on his cockpit panel – altimeter, fuel gauge, oil pressure gauge, air speed indicator, inclinometer, and tachometer – all in working order. This latest model Spad had a second Vickers machine gun mounted forward of the cockpit, and also boasted a more powerful engine -- 235 horsepower -increasing its cruising speed to 133 mph. Its ceiling had also been increased to 21,800 feet. Peering over the side into the thickening gloom below, he spotted the two balloons ahead, swaying above the drifting battlefield smoke and suppurating pockets of phosgene gas. He counted slowly to himself, measuring the next 10 miles, then waved vigorously at his companions, raising one finger, then two, shaking his gloved hand emphatically, reminding them that he would attack the balloon on the left while they both made for the one on the right. They had determined that he would first strike from above, while the other two pilots would rush in from head-on, counting on his distraction, along with audacity and surprise to get them through safely. He banked slowly to port, and then eased the Spad into a long dive. At three miles out, and about 2,000 feet above the target, he cut the magneto and glided silently through the buffeting air, his mind and eye estimating the angle that would take him down directly at the top of the balloon. The trio drifted closer in from their different directions, propellers dead in the air, still unnoticed. Excited by his perfect angle of attack, he reached for the switch to restart the engine. The German ground crew, suddenly alert, scrambled to crank the balloon back to earth, but released the tether instead. The balloon lurched up some 100 feet, the huge Maltese cross on its side popping directly into his sights. He snapped the magneto over, and the engine cranked in with a roar. Almost simultaneously, his machine gun cut loose with a streak of flame that seared into the side of the huge canvas behemoth. He had refilled his ammo belts personally, each round an explosive tracer, hoping that at least one would do the trick, igniting the hydrogen that kept the balloon aloft. He roared in closer, watching intently as a small circle of flame appeared in the center of the cross and almost immediately began spreading. He fired a last burst, then shoved the stick over with all his might, kicked hard right rudder, yawing the aircraft to the left as sharply as he could, as the German crew dove over the side of the

gondola. He continued in the tight left turn, knowing that if he climbed, the explosion would be directly beneath him, and if he dived, he might hit the tether or the other wires hanging there to guillotine unsuspecting fighter planes.

The giant gasbag exploded with a flashing, deafening roar, billowing into the sky like an obscenely pulsating jellyfish, the lurid flames illuminating the small cockpit, flinging the Spad into a sickening uncontrolled skid across the sky. He fought to right the aircraft, perspiration soaking his flying suit, fogging his goggles, his hands cramping over the control stick. He leveled off, then hauled back on the stick, shoved full throttle and fought for altitude. The German anti-aircraft guns were making up for their earlier negligence, launching a frenzied carpet of shrapnel into the air, filthy gray and black blossoms bouncing him sickeningly about as he dodged and climbed. He searched with quick glances across the horizon for his comrades, but saw nothing. The other balloon was gone as well – cranked down or destroyed –he knew not which: the ground site was in flames.

Spotting a huge cumulous formulation a thousand yards ahead, he swung right to head for it and knifed into its wispy interior. Inside, he banked gently to the right, the Spad describing a long slow circle as he checked his fuel and ammo. The sound of his engine, which had been muffled in the moist interior of the cloud, began drumming curiously louder in his ears, until he realized it was not only his engine, but the motors of a huge British HandleyPage 0/400 bomber descending onto him from above, its endless wingspan blotting out the already dim light. He chandelled out from beneath in a breathless rush, to rise up next to the bomber, its startled crew staring over mutely through the mist. He dropped the Spad flat out of the cloud, the cockpit seat shoving up against his rear end, his gut dropping in the other direction. He caught a flash of a yellow triplane approaching from his starboard, and shoved his stick forward and dived. This was getting to be a busy morning, he thought to himself. Quickly he assessed his chances: he was confident he could outrun the Fokker’s top speed of slightly over 100 mph with the Spad’s superior diving capabilities. Although this was surely the feared and famous German Imperial Air Service’s Flying Circus, which was known to be in this sector, Von Richthofen was long since dead, and with Germany’s heavy losses, the quality of enemy pilots had declined. Still, as he craned his head for a look backward, he was not in a good spot and he disliked giving up all this altitude. He hauled the Spad back and to the left, denying the following triplane a deflection shot with its twin Spandau guns. He climbed for the advantage, then instinctively leveled off and stood on a wingtip as a burst of tracer ripped into the spot he had only just vacated, rounds pinging off his undercarriage. Then he was turning tightly, trying to get inside the Fokker for a burst of his own. By now he was totally exhausted, his arms and hands numb from hauling on the stick and working the throttle and triggers. Managing to escape the explosion of the observation balloon had used up vast reserves of nervous energy, his near-miss with the British bomber in the cloud further

depleted his adrenaline, and now he was locked in mortal combat with someone he was discovering was as skilled as himself. Maybe even better. After the toll of years of combat, suddenly, today, in this gray sky, the bill was due. Both machines broke off simultaneously and climbed again toward the setting sun, dodging and jinking for advantage, firing an occasional burst as fleeting opportunities for a shot presented themselves. The maneuvering seemed to last forever; he was running nervously low on fuel, and he was certain he was down to his last few cartridges. Again, both machines tried turning into one another, to no avail, trying everything that hard-won knowledge, skill and experience had taught them – Immelmann, split-S, tight loops -- each man’s gambit frustrated by the skill and tenacity of the other. Finally, the German broke off after a final burst, and started to head for home. “Lost his stomach,” Lawrence thought tiredly, and turned to chase. In a flash, the German had clapped on rudder and looped over the top, ending up directly behind him. Lawrence had tried everything he knew and had been unable to defeat this man. He hunched his shoulders; waiting for the burst he had been expecting all these months. He was amazed he had lasted this long. In the early days of his combat flying experience, the German machines had been so superior; their pilots so uniformly excellent, that he had resigned himself before each patrol to it being his last. Somehow he had survived, until now, at this moment, the man at his back would extinguish the brief flame that had been his short life: a man who must be an extraordinary pilot to have survived this long. Deep within his resigned soul, despite the desperate tiredness squeezing in behind his eyes, his primordial will to live sent a last spasm of energy down through his sinews, gathering strength in his arms for a last mighty effort to throw his Spad into a split- S to throw off the German’s aim. Instead, incredibly, the Fokker throttled up and eased in beside him. The two pilots gazed at one another across the expanse. Was the German out of ammo? Or, like himself, was he totally and completely played out? Maybe he sensed, as did Lawrence, that they could be up here as long as their fuel held out, twisting and turning until the engines sputtered dry and they fell long miles to their deaths? Should he blast away at the man opposite with his Colt, until the clip emptied, as that other German pilot had done at him? He was too tired even to fumble for the pistol. Both men knew the war was nearly done: German plenipotentiaries were already meeting with the Allies, discussing an armistice in a war that had settled nothing. What was the sense of any of this? The German seemed to give him a satisfied look, then flicked a weary salute and dropped away. Lawrence did not follow him, but only gestured in turn and dipped his wing for home. And then for some reason, the chorus of a song rang through his

head:

He'd fly through the air with the greatest of ease A daring young man on the flying Trapeze His movements were graceful, all girls he doth please and my love he purloined away.

“Not this time, pal.”

As the darkness settled in, he sat exhausted in an old wicker chair at the edge of the field. He still wore his flying suit, his heavy flying boots splayed on the grass before him, helmet and goggles lying on the ground. A silk scarf trailed from his hand to the sparse grass, hooked on fingers too fatigued to release it. A line sergeant stood silhouetted against the horizon in front of him, firing a Very pistol at intervals into the glowering sky, signaling the location of the airdrome to any returning aircraft. Flare after flare rose into the air, popped open, then arched over and floated back down slowly, the hissing light creating an eerie halo in the heavy air. No other planes returned.

“Good morning, Captain. Did you enjoy the armistice celebration last night?” The young staff lieutenant stood cheerily in front of the desk in the operations hut, happy, spared, already thinking of the great victory parade down Fifth Avenue in New York, marching in front of everyone with his bright service ribbons. In the corner, a gramophone scratched at a popular hit: “How ‘Ya Gonna Keep ‘em Down on the Farm (After They’ve Seen Paree).” “Ah yes, 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month,” Lawrence replied. “Very precise, these politicians. Now it’s all over but the retribution and the boasting: ‘made the world safe for democracy,’ don’cha know. So much rodomontade.” “Sir?” “Big word -- another way of saying bullshit.” The lieutenant nodded brightly: nothing could ruin this day. “Sir, I wanted to remind you that that ship with the new Liberty engine that groundlooped last week and killed Lieutenant McKeever? It’s ready to go again. For the third time. Your orders are that you test everything before anyone else goes up. Of course, it’s probably not necessary now.” “Oh yes?” He gathered up his flying helmet from the desk and shoved it into the pocket of his leather flying coat. He glanced once more at a letter in his hand he had been reading from the Russian agent who contacted him in Paris, seeking pilots to fly for the civil war beginning there. He crumpled it into his pocket as well and went out the door and around to the hangar and watched them push the Spad out of the dark interior into the frosty sunlight of the early morning. He followed slowly as the men rolled it over to the flight line,

enjoying the day, savoring the quiet after four years of guns cannonading across the French landscape. He stood considering the machine for awhile, running takeoff procedure in his mind: full throttle to pick up speed, stick forward to lift the tail skid off the grass, goose it up to about 40 mph, then back gently on the stick and up and away! Simple. He thought of the hundreds of times he had done this during the war, all the takeoffs and landings. For the first time in a long while he allowed himself to think of the men he had flown with, the men who shared all of this with him; the men who were gone. He nodded to the mechanic standing by to spin the propeller to turn the engine over, and then glanced at the lieutenant who had accompanied him, and inquired: “It’s all ready to go, you say?” “Yessir.” He looked at the mechanic: “It’s a bloody under-powered deathtrap with that damn engine, wouldn’t you say?” “Yessir. If you say so, sir.” “I do indeed.” He climbed up to the cockpit, looked in and saw a Very pistol on the seat. He reached in, picked it up and jumped lightly back down onto the grass. He walked a few feet from the aircraft, motioning the mechanic and the young officer away with a wave of his hand. He fired the pistol directly into the side of the wood and canvas airframe where the petrol tanks were. The Spad exploded with a whump, as the onlookers scrambled away, their eyes wide, mouths open in astonishment. He watched interestedly as the wings bent into a Vee, then folded in on the exposed airframe, the fiery structure collapsing onto the undercarriage, the smoking propeller dropping awkwardly off onto the grass. “Oh dear,” he said to no one in particular. The lieutenant seemed to be having trouble breathing, his mouth open, and his hands gesturing hopelessly. He began sprinting in short bursts in different directions, then returned to stand gaping at the heavy smoke spiraling up from the wreckage, undecided whether to run for help, or to just run away and pretend he had never seen anything. Within a few minutes, an olive drab Ford bounded across the airstrip toward them, sliding over the grass to a halt next to the group. An anxious soldier called to Lawrence from behind the wheel: “Captain, they want to see you at the headquarters hut – right away,

sir!”

He mounted the running board of the Model T and pulled the driver out of the cab. Sliding himself into the driver’s seat, he released the brake lever on the floor and reached his right hand through the wooden steering wheel to advance the throttle. “Captain -- the airplane,” the driver called, his hands cupped to his mouth. “They want to see you!” “Tell them to send me the goddamn bill,” he shouted back as the flivver chugged away from the direction of HQ. “For this thing, too,” he

shouted back. Take it out of my pay. I’m going over to Soissons to collect someone, and then we’re going home.”

New York, December 21, 1918 – (Combined News Services) -- Captain Hobart A. H. (Hobey) Baker, hockey and football player of international reputation, was accidentally killed on Saturday in France, according to a cable dispatch. He was making his last flight, for he had already received orders to return home when his plane fell. Details have not yet been received.

In Memory of Lt. Hugh S. Thompson 96 Aero Squadron AEF KIA 16 Sept. 1918, St. Mihiel, France

Toronto Photo by Andrea England

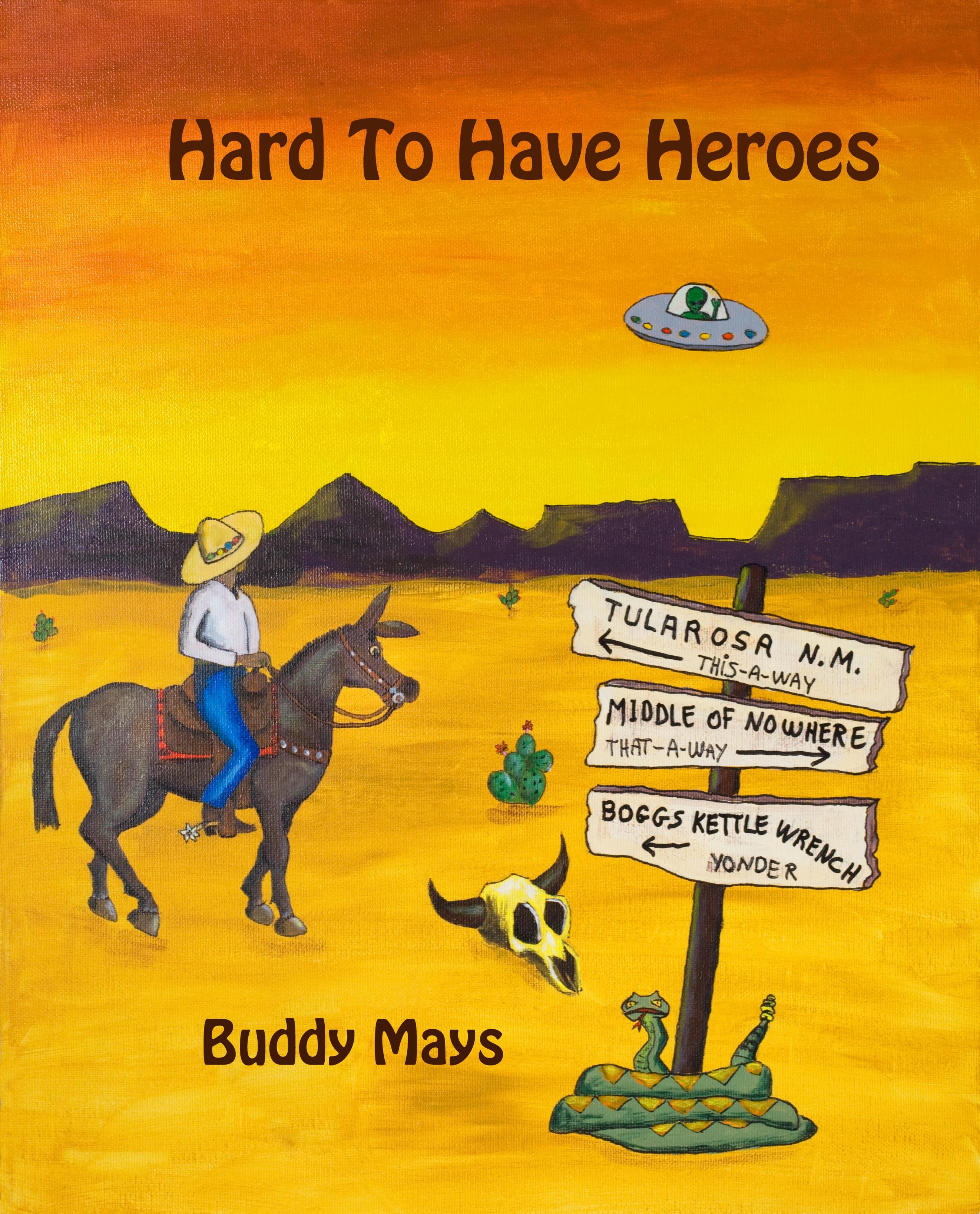

Some Fine Summer Reading

Need a book to readthis summerat the beach, on a plane or wherever? Excerpts from these fourwonderful books will help you decide. The first, beginning on the following page, is from Bill Scheller’s work in progress, “In All Directions,”coming soon from Natural Traveler Books.

Bill Scheller In All Directions

Thirty Years of Travel

Tony Tedeschi

Unfinished Business

She could only hope to put it all behind her, if the painting, like that terrible day in her life, were relegated, emphatically, to her past.