7 minute read

Be the Best

Advertisement

Photos courtesy of AD1 (AW) Jonathan J Hunt, ENS Brandon Shackelford and CDR Christopher M Amis

WHEN AN UNSTOPPABLE FORCE MEETS AN IMMOVABLE OBJECT

By AD3 (AW) Thomas R. Scott

It was an unusually cold late February night on the flight line at Marine Corps Air Station Iwakuni, home of America’s forward-deployed Carrier Air Wing, CVW-5. Usually, shore-based operations have a little more relaxed pace than underway operations, but this was a hectic shift on top of an unusually busy workweek.

Maintenance control warned everyone that at least two of the currently “down” jets would need to be “up” to successfully execute the flight schedule in the morning. Like many squadrons, ours leaned heavily on night check to get things done. My shop was also spread a little thin as a result of Sailors attending mandatory training in the morning. To pick up a bit of the slack, Maintenance Control tasked our “Mech”-qualified Quality Assurance Representative (QAR) with conducting maintenance instead of conducting their regular duties acting as safety observers.

As a qualified turn operator and Collateral Duty Inspector (CDI), I was well-positioned to make a significant contribution in taking a dent out of the workload. After speaking with the other CDI and qualified “turn body” in the shop, we agreed to split the workload to get as many of the tasks done as possible. With a plan to work from easiest to hardest, we could complete our own tasks and come together to conquer more challenging tasks at the end of the night. I volunteered to take on two downed generators and an engine wash. All of these tasks required low power turns. I’ve been through the routine of conducting these kinds of turns plenty of times before. When preparing for a turn, a series of steps need to be completed before approaching the jet.

First, the turn operator is supposed to read the Aircraft Discrepancy Book (ADB). Then there is the gathering of all the required personnel. Specifically, you need the turn operator, a plane captain, a CDI, two safety observers and a flight deck Chief.

Once you’ve completed all the prerequisites and gathered the required personnel, a brief is held in maintenance control to ensure everyone is on the same page.

Finally, the turn operator is given a turn card to head out to the jet for final inspections and, eventually, the turn itself. I repeatedly completed this routine and would be lying if I said I wasn’t feeling a little complacent and overconfident with my abilities.

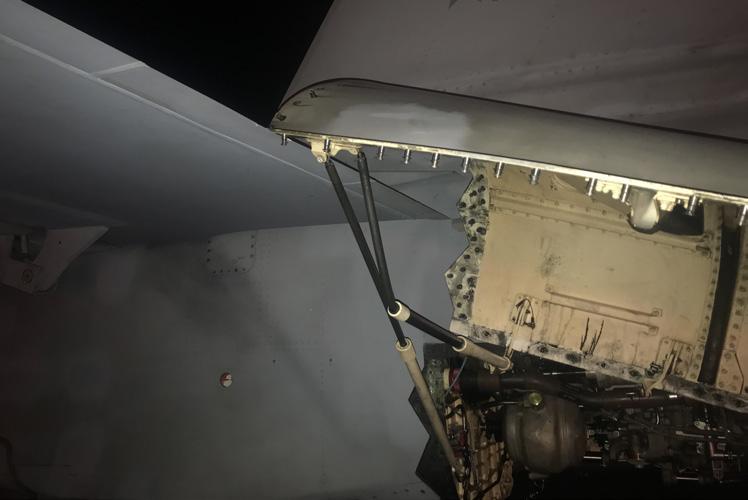

AFTER REMOVING AND REPLACING THE SECOND GENERATOR, I GOT READY FOR THE ENGINE WASH LOW POWER TURN.” By this time everyone was busy. It was cold outside and I figured it would be fine without the extra personnel since I was so used to this type of turn. After all, I had another Sailor out on the jet to make sure everything was safe and secure. After the walk around, I hopped in the cockpit. I then turned the battery on and proceeded to start up the Auxiliary Power Unit (APU). When the green light for the APU came on, I began to motor the port engine. Everything seemed fine until I saw the safety run to the jet. My shipmate flagged me down; immediately, I shut down the engine and climbed out of the cockpit to see what happened. It turns out that the 64L door got caught on the moving trailing edge flap, resulting in breaking off the hinges and piercing the flap. I notified the QAR and other shop notitied the CDIs about the incident. How could this have happened? I was so focused on getting the engine wash done that the 64L door was left in the upright position to be ready for the next task! I also didn’t realize that when an APU is cranking one of the motors, the hydraulic pumps kick in and the flight surfaces move even with the flaps in the full position and the flaps switch in the full position. Naval Aviation demands focus, communication and adherence to the procedure for the safe execution of aviation maintenance. Permitting complacency, overconfidence or distraction on the flight line only serves to tempt disaster. This story should serve as a perfect example of why we, aviation maintenance professionals, should not take complacency lightly. Pay attention, do your pre-ops; take your time and never think, “It won’t happen to me!” We hope our brothers and sisters up and down the flight line can benefit from our mistake, as we all strive to be the best! #1

Simple Task, Little Damage, Big Cost

ON JUNE 30, 2020, TWO VFA-32 AVIONICS TECHNICIANS WERE WORKING ON AN F/A-18F IN ONE OF THE HANGAR BAYS ON THE USS DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER (CVN 69).

U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Peter Burghart

THEIR TASK THAT EVENING INVOLVED REASSEMBLING THE JOINT HELMET-MOUNTED CUEING SYSTEM (JHMCS) IN AN AIRCRAFT’S AFT COCKPIT. THERE ARE SEVERAL PARTS, LOTS OF FASTENERS AND CABLE CONNECTIONS IN PUTTING A SYSTEM BACK TOGETHER.

#2

By AT3 Bryan Minneman and AT3 Anthony Klein

Amongst the work involved in the process, there is little space for parts. The parts were moved at several different points in time to create space to work in the cockpit. During the installation of the JHMCS equipment, the aircraft was moved between the hangar bays.

Due to the aircraft moving, neither of the Sailors involved recalled when the parts were moved; however, at some point, one of the last pieces that required installation made its way to the very aft section of the canopy sill. This area houses many essential parts, such as canopy seals, actuators, actuator arms, thin-layer explosives and one of the most vital sections of the canopy frame. In the aft section of the canopy sill, the area the part made its way to is very dark, painted black and the part that shifted was black as well. As work continued past shift turnover, the two Sailors decided they had gotten to the point they needed to turn the job over to the next shift.

As an all tools accounted for (ATAF) evolution was being completed on the toolbox, the other Sailor was closing up the jet. The first function is shutting the canopy. There are multiple steps in closing and verifying the canopy sill is clear of all foreign objects and debris (FOD) is one of them. This step was not performed thoroughly that night. While shutting the canopy, just before it met the canopy sill, both Sailors heard a relatively loud “pop.” They stopped the evolution immediately and proceeded to reopen the canopy and check the source of the noise. While one Sailor checked the noise source, the other went to inform the Aviation Structural Mechanic (AME) shop of the situation.

At this point, the canopy had already shut on top of the JHMCS cable plate, damaging both the plate and the aft section of the canopy frame. At first, it looked like a potentially repairable warp in the structure, but it was enough for a mandatory canopy removal and replacement. An F/A-18F has two seats. This makes the canopy relatively larger and heavier than that of its single-seat counterparts. If you look in the integrated electronic technical manual, you will find that the canopy weighs quite a lot, regardless of the version. The sheer size and weight alone can give you a good indication that it is costly.

When damaged beyond repair, it is expensive enough to be considered a Class C mishap.

Class C mishap classification is any mishap costing more than $60,000 but less than $600,000. Many things could have been done to avoid a mishap, such as thoroughly checking the canopy sill before closure, having a collateral duty inspector or supervisor on the job to double-check the sill, following the steps in the operating publication and avoiding rushing back to the shop.

Had these two Sailors taken the time to slow down and go through all the steps, the mishap could have been avoided.

It is crucial to slow down and take your time on the job. There is no reason to rush to finish a job and cause either a mishap or rework for your shop. It is always good practice to have someone else check your work. Over the last several years, “crunching” canopy sills has been one of the top five Super Hornet maintenance-related mishaps degrading the aircraft’s readiness.

Right: Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Chris Bartlett Left: Photo by Petty Officer 3rd Class Lauren Booher