North Carolina Pharmacist Volume 105 Number 1 Advancing Pharmacy. Improving Health. Official Journal Of The North Carolina Association Of Pharmacists ncpharmacists.org 2024 NCAP Annual Convention June 24th - June 26th “Off the Beaten Path: Trekking Toward Transformative Practice” Register Now - Early Bird Rates End April 30

North Carolina Pharmacist (NCP) is currently accepting articles for publication consideration. We accept a diverse scope of articles, including but not limited to: original research, quality improvement, medication safety, case reports/case series, reviews, clinical pearls, unique business models, technology, and opinions.

NCP is a peer-reviewed publication intended to inform, educate, and motivate pharmacists, from students to seasoned practitioners, and pharmacy technicians in all areas of pharmacy.

Articles written by students, residents, and new practitioners are welcome. Mentors and preceptors – please consider advising your mentees and students to submit their appropriate written work to NCP for publication.

Don’t miss this opportunity to share your knowledge and experience with the North Carolina pharmacy community by publishing an article in NCP.

Click on Guidelines for Authors for information on formatting and article types accepted for review.

For questions, please contact Tina Thornhill, PharmD, FASCP, BCGP, Editor, at tina.h.thornhill@ gmail.com

North Carolina Pharmacist is the official journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists Located at: 1101 Slater Road, Suite 110 Durham, NC 27703 Phone: (984) 439-1646 Fax: (984) 439-1649 www.ncpharmacists.org

Call for Articles

Official

1101 Slater Road, Suite 110

Durham, NC 27703

Phone: (984) 439-1646

Fax: (984) 439-1649

www.ncpharmacists.org

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Tina Thornhill

LAYOUT/DESIGN

Rhonda Horner-Davis

EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS

Anna Armstrong

Jamie Brown

Lisa Dinkins

Jean Douglas

Brock Harris

Amy Holmes

John Kessler

Angela Livingood

Bill Taylor

BOARD OF DIRECTORS

EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR

Penny Shelton

PRESIDENT

Bob Granko

PRESIDENT-ELECT

Tom D’Andrea

PAST PRESIDENT

Ouita Gatton

TREASURER

Ryan Mills

SECRETARY

Beth Caveness

Madison Wilson, Chair, SPF

Anita Yang, Chair, NPF

Cornelius Toliver, Chair, Community

Tyler Vest, Chair, Health-System

Kimberly Hayashi, Chair, Chronic Care

Mackie King, Chair, Ambulatory

Angela Livingood, At-Large

Elizabeth Locklear, At-Large

Macary Weck Marciniak, At-Large

North

any manner, either whole or in part, without specific written permission of the publisher.

Pharmacist

North Carolina

Journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists

Carolina Pharmacist (ISSN 0528-1725) is the official journal of the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists. An electronic version

published quarterly. The journal

provided to NCAP members through allocation of annual dues. Opinions expressed in North Carolina Pharmacist

not necessarily official positions or policies of the Association. Publication of

advertisement

represent

endorsement. Nothing

publication

reproduced in

Volume 105 Number 1 • From the President..................................................................................................4 • Drug Supply Chain Security Act..............................................................................6 • Who Gets What?...................................................................................................12 • New Drug Monograph..........................................................................................18 • NCAP News........................................................................................................24 • In Case You Missed It.............................................................................................26 • A Message from PAAS National............................................................................29 • NCAP Classifieds................................................................................................30 A Few Things Inside North Carolina Pharmacist is supported in part by: • Pharmacy Technician Certification Board (PTCB) .................................5 • Alliance for Patient Medication Safety ..................................................10 • Working Advantage.................................................................................10 • NCAP Career Center .............................................................................17 • Pharmacists Mutual Companies ............................................................23 • Pharmacy Quality Commitment.............................................................28 Event Sponsorship Ads: • Karius ....................................................................................................11 • Founders Wellness ................................................................................25 CORRECTIONS AND ADVERTISING For rates and deadline information, please contact Rhonda Horner-Davis at rhonda@ncpharmacists.org Connect With Us!

is

is

are

an

does not

an

in this

may be

It is with great pleasure I write my first installment for the North Carolina Association of Pharmacists as the 2024 President.

I am beyond excited to have this wonderful opportunity. Before I begin, I would like to thank all of the individuals who have and currently serve. They are all working to fulfill the vision of NCAP as the essential organization representing pharmacy in North Carolina, fostering the advancement of pharmacy practice to improve the health of the people we serve.

As I step into this year, I am reminded how much is changing across all aspects of our lives and throughout our communities. Given all that change, NCAP has remained steadfastly focused on three operational tenets, including:

1. Building awareness about the Association, pharmacist, and technician roles,

2. Creating value for our members, and

3. Generating a voice for the profession.

The mission of NCAP is clear and serves as a true north for us, our membership, and those who seek to join the association: To unite, serve, and advance the profession

• From the President •

Robert P. Granko, PharmD, MBA, FASHP, FNCAP

“Of Service”

of pharmacy for the benefit of society. Together, leveraging our network and our communities, we have the power to effect positive change and make a meaningful impact on issues affecting our profession and importantly, the care we deliver for our patients, regardless of the practice setting.

My focus over the next 12 months is quite simple: I’ve titled it “Of Service”; that’s what fuels my professional and personal desires as well as my personal leadership vision of empowering my team and those around me by creating a thriving culture that enables and fosters each pharmacy team member to do what they do best, better.

A common definition of service may include “Helping or doing work for someone.” Building off that theme and leaning on work covered in The Leadership Challenge by Kouzes and Posner, I am reminded of the five practices of an exemplary leader.

These five practices will shape my messaging over the coming months, and you will have to stay tuned for all five. Today, I am going to introduce #1. As I begin my service for you, NCAP, and its membership, I ask that you join me and encourage others you work with to carry forward and share some of what we will discuss over the coming months.

Modeling the Way

Part of modeling the way is finding your voice – and directing the voice of NCAP. NCAP has aligned its actions with shared values, including:

• Presenting a unified voice for pharmacy on social, political, and economic issues.

• Providing a forum for the exchange of innovative ideas among pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and student pharmacists.

• Equipping pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, and student pharmacists with information, education, and resources necessary for optimal patient care.

• Anticipating future information and professional development needs for pharmacy practice.

• Strengthening collaborative relationships among pharmacists, pharmacy technicians, student pharmacists, and other health professionals.

As I close out this first installment, I encourage you to share your voice around NCAP and how our great association has modeled the way for so many of us across the state and beyond. I am honored to serve as NCAP President and be your voice for this brief time. I remain excited about the myriad of possibilities that lie ahead for NCAP and its membership and look forward to sharing the next exemplary leadership practice.

Page 4

The Final Phase of Implementation for the Drug Supply Chain Security Act

By Horng-Ee Vincent Nieh, PharmD/MBA Candidate and Dr. Penny S. Shelton

By Horng-Ee Vincent Nieh, PharmD/MBA Candidate and Dr. Penny S. Shelton

Background

Drug counterfeiting is a shrouded and harmful problem that permeates both non-medical and legitimate healthcare operations throughout the world. Healthcare crises, like the opioid epidemic and the COVID pandemic, further exacerbate and create opportunities for counterfeiters to prey upon individuals and exploit weaknesses in our drug supply chain controls. Title II of the 2013 Drug Quality and Security Act is known as the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA).1 The DSCSA was to be implemented in phases over a ten-year period to create a more secure, interoperable, and electronic track and trace system for the prescription drug supply chain in the United States. The final DSCSA requirements, to track and trace to the individual package or unit level, were to be enforced by November 27, 2023; however, in August 2023, the United States Food and Drug Administration called for a one-year delay until November 27, 2024.2

Problem: Drug Counterfeiting

To fully understand the importance of the DSCSA, it is helpful

to delve somewhat into recent pharmaceutical crimes. The Pharmaceutical Security Institute (PSI) broadly categorizes drug counterfeiting, diversion, and theft as “pharmaceutical crimes.”

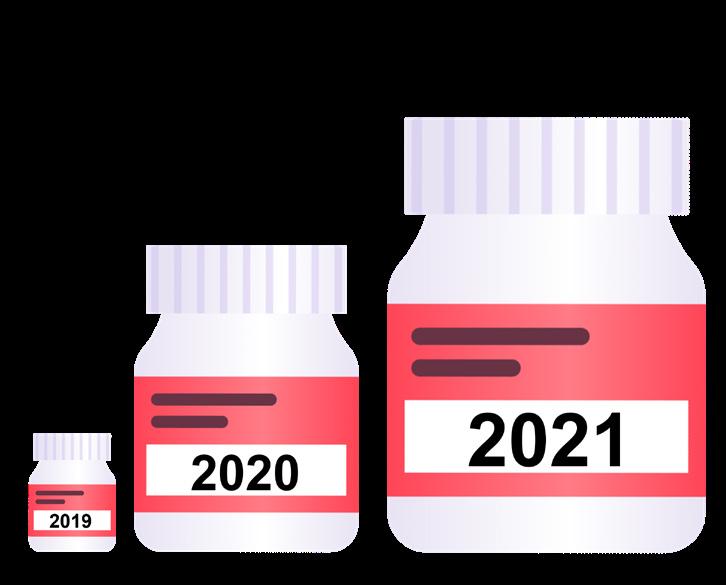

The PSI’s most recent data, for 2017 to 2021, shows a consistent year-over-year increase in pharmaceutical crime, with a high of 5,987 incidents in 2021. The 2021 incidents represented a 40% increase from the previous year, and nearly 60% were classified as “commercial” offenses, meaning these cases involved greater than 1,000 dosage units.3 It is important to note that many non-commercial pharmaceutical crimes are not represented in the annual incident reports due to both an underreporting of these types of incidents and because of their lesser magnitude of impact. Furthermore, a lack of adequate tracking and reporting systems in some countries contributes to an overall underrepresentation of the actual number of pharmaceutical crime incidents worldwide. When reviewing incident data by geographical region for the 142 countries represented among the 5,987 pharmaceutical crimes in 2021, most occurrences were from North America.4

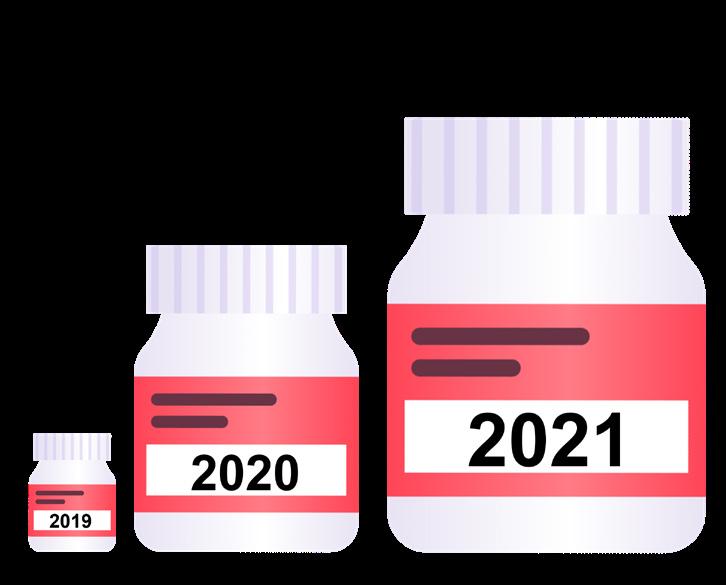

In recent years, the U.S. Drug En-

forcement Agency (DEA) has also identified an alarming increase in counterfeit pill seizures nationwide. As depicted in Figure 1, by September 2021, the DEA reportedly had already seized more drugs in 2021 (9.6 million pills) than the previous two years combined (9.4 million pills), representing a 340% increase in counterfeit drug seizures from 2019 to 2021.5

Counterfeit opioids (i.e., oxycodone and hydrocodone) are among the most commonly seized drugs, and the counterfeit opioid market is a major contributor to the United States’ ever-increasing opioid crisis. The DEA has also identified fentanyl and methamphetamine as the two most common substances in counterfeit pills. Provisional data from

Page 6

Figure 1. Visual representation of the number of counterfeit drugs seized by the DEA from 2019-21.5

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports 107,622 drug-overdose deaths in the United States for 2021, up 15% from what was a previous record-high of 93,655 overdose deaths in 2020.6 Fentanyl was identified as the most common opioid found in counterfeit pills, as well as the greatest cause of drug overdose deaths. DEA lab analyses have also concluded that 40% of the seized drugs containing fentanyl contain a potentially lethal dose.5

Meanwhile, non-narcotic medication counterfeiting has become a multi-billion-dollar criminal enterprise. In an interview with Fierce Pharma, the PSI reported that medications for chronic conditions are among the most popular counterfeits. From oncology, cardiovascular, antibiotics, and antipsychotics to HIV, insulins, erectile dysfunction, and weight loss medications, nothing is seemingly off the table for profit-hungry counterfeiters willing to prey on patients and others.7 The World Health Organization estimates that globally, 10-11% of medications are substandard or fake.8

Solution: DSCSA

The U.S. Congress established the DSCSA in November 2013 as a means to help address the staggering counterfeit prescription drug problem.1 The Act is to be enforced by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The agency’s DSCSA guidance centers on the establishment of an interoperable electronic system to track and trace pharmaceutical drugs throughout the entirety of

the supply chain, from manufacturing to dispensing.1,9 The Act will also require national licensure for wholesale distributors and third-party logistics providers.

Once fully in place, the DSCSA regulations will require entities in the drug supply chain, including manufacturers, distributors, wholesalers, re-packagers, hospitals, pharmacies, dispensers, and third-party logistics providers, to electronically track and trace the origin of a drug product and be able to provide the transaction history, information, and statement.1 Specifically, the transaction information (TI) primarily refers to product information, including but not limited to name, dosage, strength, NDC, lot number, and date of transaction, whereas transaction history (TH) outlines the complete transaction exchanges through the supply chain from the manufacturer to the current party or end user. The transaction statement (TS) is a paper or electronic form that the entity transferring ownership of the product is required to produce upon request to help confirm the legitimacy of the product at the time of the transaction.1 These DSCSA regulations will pertain to all prescription drugs for human use. Exemptions from the requirements include animal medications, blood components for transfusion, radioactive drugs, biologic products, imaging drugs, certain intravenous products, medical gases, and drugs compounded in compliance with section 503A or 503B of the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act.1,10

The DSCSA’s goal is to protect pre-

scription drug consumers from counterfeit, stolen, adulterated, or harmful drugs that infiltrate the U.S. drug supply chain. In product tracing, requirements will be able to track a step-by-step account of where the drug was sourced and which entities have handled the product during its distribution processes. Serialization may need to be updated as a unique product identifier should be interoperable across all drug-tracking systems. Product verification procedures should also be established for each entity to confirm their sourced drugs are legitimate and unadulterated. Drug supply chain entities are also required to have measures in place to investigate suspect products, and if a drug is deemed counterfeit or adulterated, the drug must be reported to the FDA.9,11

The DSCSA rollout has been gradual since its passage in 2013. In most cases, manufacturers and distributors had earlier implementation deadlines than dispensers, as they are upstream in the supply chain. The timeline, depicted in Figure 2, highlights major DSCSA requirements over the past ten years and note, the final unit-level, track-and-trace phase, previously set for November 2023, has been delayed until November 27, 2024. 12,13

Page 7

Pharmacists play a pivotal role in the DSCSA because pharmacies, denoted as dispensers in DSCSA regulations, are typically last in the supply chain, just before patients receive their medication. As such, pharmacists should ensure their pharmacy procures drug products from authorized trading partners that have been licensed to distribute drugs in their respective states. If pharmacists are unsure whether their trading partners are registered or licensed, they can contact their appropriate state authority. Pharmacists in North Carolina should check with the North Carolina Department of Agriculture & Consumer Services (NCDA & CS) Food and Drug Protection Division to see if a company is properly registered as a prescription drug wholesaler. All product tracing documents should be stored safely for six years, and an effective procedure should be in place to recall the data and investigate any suspicious drugs should issues arise. Suppose a drug product is suspected or deemed to be illegitimate. In that case, the pharmacy should work with the upstream

supply chain entities and manufacturers to determine the cause and notify the FDA within 24 hours.11,13

FDA DSCSA Pilot Program

The FDA established a pilot program on February 8, 2019, to assess the effectiveness of various technologies and operational processes needed along various points in the supply chain.14

The FDA collected data for the pilot program among participating supply-chain stakeholders between May 2019 and June 2020. The average study period for individual stakeholders was six months. Participating supply-chain stakeholders included, among others, AmerisourceBergen, Cardinal Health, Walmart, and Sanofi.

At the end of the year-long pilot, the FDA held a virtual meeting to gather feedback from the stakeholders and then released its interoperability findings from the pilot project. Interoperability is

one of the main requirements of the DSCSA, and the FDA concluded that either a single, centralized system or a decentralized range of solutions could be viable if standardization were maintained to facilitate interoperability. In terms of effective software systems, there were instances where existing systems could be modified and others where new software components were implemented. The FDA also found that many manual processes became automated in these updates.15

Compliance Resources

A quick online search can yield a long list of DSCSA proprietary compliance resources. Most of these software systems are designed to help verify and report data. Some companies offer different pricing tiers, including limited free or trial packages, that can appeal to pharmacies with various customer bases. National pharmacy associations back some software systems. For example, the DSCSA 360 system is en-

Page 8

Figure 2. Timeline of major requirements in the DSCSA.1

dorsed by the Federation of Pharmacy Networks and the National Community Pharmacists Association. Another software system, Pulse, is endorsed by the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy. Pulse is expected to be free to any state-registered pharmacy to track and trace drugs, but a fee will be required to access a list of authorized trading partners.16

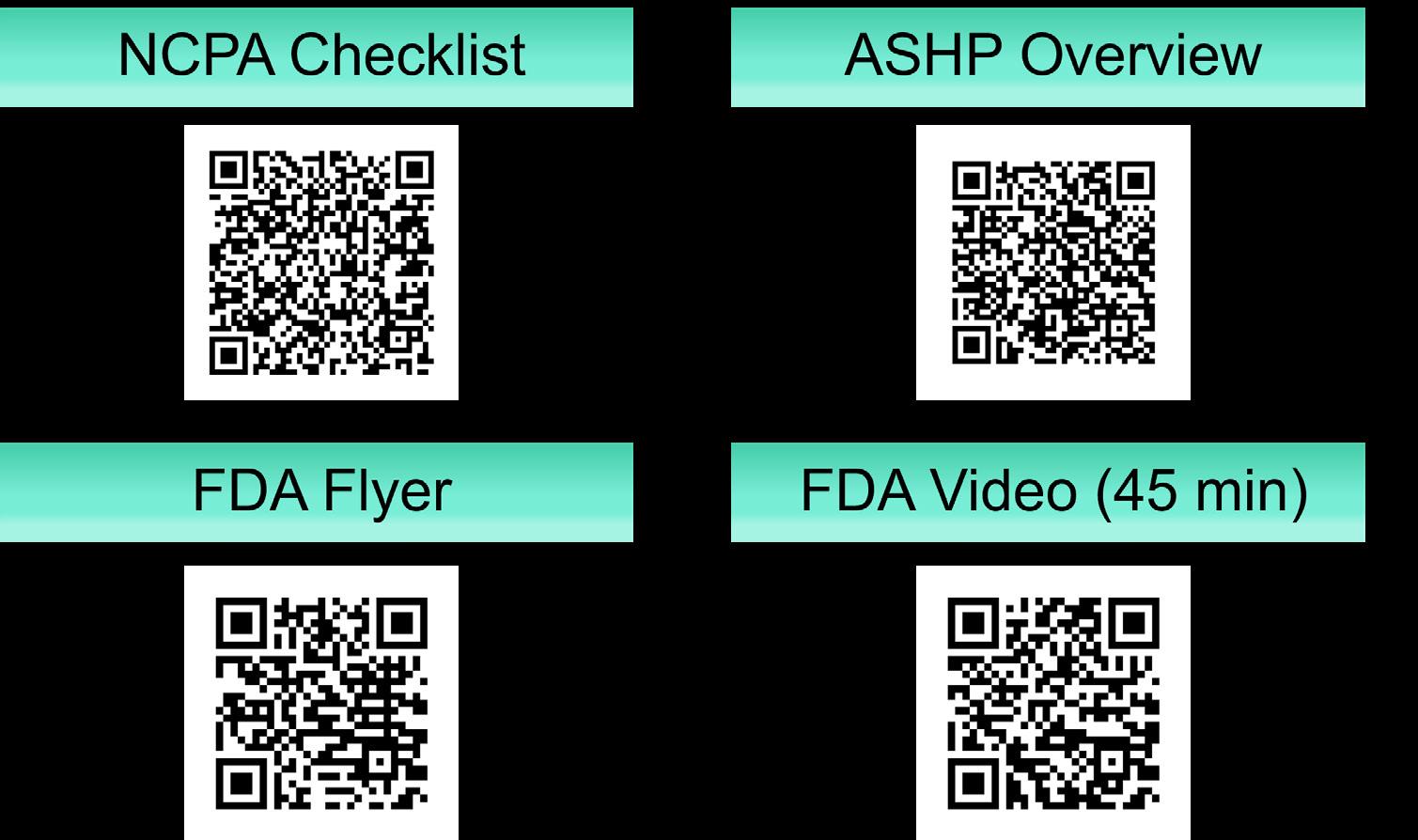

Figure 3 provides quick reference links to an array of helpful DSCSA resources made available by national pharmacy organizations.

lot number, and expiration date, even if the lot consists of hundreds of units. This may cause a strain on current inventory tracking processes and may lead to need-based software updates or staffing. During this phase, interoperability must continue to be maintained with the drug exchange, verification, and tracing. All parties in the supply chain must continue to be able to communicate effectively with each other, even if different software systems are utilized to manage data.17,18

Conclusion

Also referred to as “Phase 2,” the last DSCSA requirements are scheduled to become effective on November 27, 2024. The most substantial change will be the transition from tracing at the lot level to the individual package or unit level. In other words, every single drug in the pharmacy will be required to have a unique product identifier, serial number,

Pharmacists should ensure their current drug procurement processes can be tracked and traced via a secure, interoperable electronic system. Pharmacy systems should be able to track the information through the supply chain as far back as the manufacturer and be ready to check and verify the package identifier at the package or unit level. Pharmacies also need to be prepared to access and share track and trace information to the unit level for regulatory authorities, as well as be prepared

to provide product information and transaction history to a clinic or patient if requested for a dispensed medication.

Authors: Horng-Ee Vincent Nieh, PharmD/MBA Candidate, Class of 2024, Campbell University College of Pharmacy & Health Sciences, and Dr. Penny S. Shelton, PharmD, FASCP, FNCAP; Executive Director, North Carolina Association of Pharmacists

References

1. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA). May 23, 2023. Accessed June 14, 2023. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/ drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/ title-ii-drug-quality-and-security-act

2. US Food and Drug Administration. DSCSA compliance policies establish 1-year stabilization period for implementing electronic systems. August 30, 2023. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www. fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/dscsa-compliance-policies-establish-1-year-stabilization-period-implementing-electronic-systems

3. Pharmaceutical Security Institute. Incident Trends. 2023. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.psi-inc.org/incident-trends.

4. Pharmaceutical Security Institute. Geographic Distribution. 2023. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.psi-inc.org/ geographic-distribution

5. Drug Enforcement Administration. Counterfeit Pills. September 2021. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www.dea. gov/sites/default/files/2021-09/DEA_ Fact_Sheet-Counterfeit_Pills.pdf

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Overdose Deaths in 2021 Increased Half as Much as in 2020—But Are Still Up 15%. May 11, 2022. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www. cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/nchs_press_ releases/2022/202205.htm#:~:text=Provisional%20data%20from%20 CDC%27s%20National,93%2C655%20 deaths%20estimated%20in%202020.

7. Miller G and Duggan E. Special Report: Top Counterfeit Drugs. Fierce Pharma. Accessed March 11, 2024. https://www. fiercepharma.com/special-report/ top-counterfeit-drugs-report

8. Pathak R, Gaur V, Sankrityayan H, Gogtay

Page 9

Figure 3. DSCSA Quick References. Scan the QR codes for access.

J. Tackling Counterfeit Drugs: The Challenges and Possibilities. Pharmaceut Med. 2023;37(4):281-290. doi:10.1007/ s40290-023-00468-w.

9. King C, Fink J. What Are the Drug Supply Chain Security Act’s Key Provisions? Pharmacy Times. 2017;83(11). Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/view/what-are-the-drugsupply-chain-security-acts-key-provisions

10. US Food and Drug Administration. FD&C Act Provisions that Apply to Human Drug Compounding. August 13, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2024. https:// www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fdc-act-provisions-apply-human-drug-compounding#:~:text=Section%20503A%20of%20the%20 FD%26C,compounding%20within%20 an%20outsourcing%20facility.

11. DispenserEDU. DSCSAEdu Resources. 2023. Accessed June 15, 2023. https:// dscsa.pharmacy/resources/

12. US Food and Drug Administration. Pharmacists: Utilize DSCSA Requirements to Protect Your Patients. January 19, 2022. Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www. fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/pharmacists-utilize-dscsa-requirements-protect-your-patients

13. Milenkovich N. Pharmacies Gear Up for DSCSA Interoperability Go-Live Deadline. Pharmacy Times. 2023;89(1). Accessed June 21, 2023. https://www. pharmacytimes.com/view/pharmacies-gear-up-for-dscsa-interoperability-go-live-deadline

14. US Food and Drug Administration. DSCSA Pilot Project Program. May 24, 2023. Accessed June 20, 2023. https://www. fda.gov/drugs/drug-supply-chain-security-act-dscsa/dscsa-pilot-project-program

15. US Food and Drug Administration. Drug Supply Chain Security Act Pilot Project Program: Final Program Report. May 2023. Accessed June 20, 2023. https:// www.fda.gov/media/168307/download.

16. Pharmaceutical Commerce. NABP Hopes to Fill a Key Gap in DSCSA Compliance: Local Pharmacies. March 15, 2023. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www. pharmaceuticalcommerce.com/view/ nabp-hopes-to-fill-a-key-gap-in-dscsacompliance-local-pharmacies

17. National Community Pharmacists Association. Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) Pharmacy Checklist and Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) Considerations for 2023. March 20, 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https:// ncpa.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/ NCPA%20DSCSA%20Checklist%20 and%20SOP%20guidance%20 2023%20FINAL_021323.pdf.

18. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Preparing for the November 2023 Drug Supply Chain and Security Act Requirements. 2023. Accessed June 22, 2023. https://dscsa.pharmacy/ wp-content/uploads/2023/02/ASHP_ DSCSA_Member_02062023-Update.pdf

Page 10

All NCAP members can unlock the best life has to offer with exclusive savings on: Theme Parks, Attractions and Shows; Hotels, Flights and Rental Cars; Concerts, Sports and Live Events; Movie Tickets; Electronics and much more. Visit the Membership Benefits tab at ncpharmacists.org to find out more! www.workingadvantage.com 2530 Professional Road Suite 200 North Chesterfield, Virginia 23235 Toll Free: (866) 365-7472 www.medicationsafety.org Discounts on Home, Travel, and Entertainment

Combat Antimicrobial Resistance with Culture-Independent AMR Marker Detection.

In addition to detecting 1,000+ pathogens (including DNA viruses, fungi, and bacteria) from blood, the Karius Test® detects bacterial AMR markers for 4 classes of antimicrobials across 18 bacterial pathogens.

2.8M AMR INFECTIONS occur in the US each year.1

The Karius Test is designed to help improve the diagnosis and management of life-threatening infections.

Pathogen identification combined with genotypic AMR detection for bacterial infections may help clinicians to optimize antimicrobial treatment for a variety of diagnostic applications.

Click the icons below for more information on use of the Karius Test for some of the most relevant diagnostic applications.

35,000+ DEATHS reported as a result of AMR infections annually in the US.1

Click here to learn more about the Karius Test and its AMR capability.

Pneumonia Febrile Neutropenia Endocarditis

The Karius Test includes detection of common AMR markers for 4 classes of antimicrobials across 18 bacterial pathogens:

• Methicillin-resistant Staphylococci (SCCmec, mecA, mecC)

• Vancomycin-resistant Enterococci (vanA, vanB)

• Carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria (KPC)

• Extended spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Gram-negative bacteria (CTX-M)

References: 1. National Infection & Death Estimates for Antimicrobial Resistance. Centers for Disease Control. 2021. Accessed from https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/national-estimates.html

Karius Test is an LDT. Clinicians should independently evaluate its use and interpret test results. This content is provided for informational purposes only and is not intended or implied to be an exhaustive list of considerations or substitute for existing medical expertise or guideline recommendations.

WITH BACTERIAL ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE (AMR) DETECTION

Who Gets What? Drivers of Emergency Room Use & Access to Medication Assistance Programs in North Carolina

Abstract:

Background: Prescription Assistance Programs (PAPs) have become an integral part of the healthcare system and function largely as a safety net for patients who lack sufficient prescription coverage. By lowering costs to patients, hospitals, and taxpayers, PAPs strive to provide a win-win scenario for all stakeholders involved. Despite having more than 100 active sites in North Carolina, some of the most populous counties still lack access or have disproportionate access per capita.

Methods: A linear regression analysis was conducted to investigate the impact of access to PAP sites, median age of county residents and urban vs rural county setting on ER visit volume per capita on a county level.

Results: Neither the median age of the population nor the number of MAP sites within a county had a significant impact on ER visit volume per capita. However, the statistical analysis showed the urban-rural environment of the counties did make a difference in the ER visit volume per capita. Rural counties had higher access

By Dr. Amro Ilaiwy and Dr. Maureen Berner

to MAP sites per capita compared to urban counties.

Limitations: Higher numbers of MAP sites within a county may simply reflect declining insurance coverage and an increased need for prescription assistance within rural populations. The decision-making logic behind MAP site distribution remains unclear.

Conclusions: Access to MAP sites was not associated with a decrease in ER visit volume. Further studies are needed to evaluate the role of access to primary care services as well as insurance coverage on a county level in ER visit volume and healthcare service use.

The terms MAP and PAP are used interchangeably to describe medication assistance programs or prescription assistance programs.

Background

Ensuring adequate access to emergency room (ER) services is vital to public health. Determining the factors driving emergency room visit volume helps guide funding decisions for hospitals within different counties. It also provides healthcare facilities with

a roadmap to achieving adequate staffing and avoiding overcrowding and diversion, which in turn affects ER visit volume. (1) Many factors can impact visit volume, including seasonal and weather-related changes, urban vs. rural county settings, and the median age of the population. (2,3)

Prescription Assistance Programs (PAPs) have become an integral part of the healthcare system and function largely as a safety net for patients who lack sufficient prescription coverage. Current research suggests PAPs can have a gross impact on healthcare access and cost in certain geographical regions. Demonstrating such an impact at a local county level can be extremely valuable to local governments as the burden of lack of access to healthcare often falls on the county resources including local emergency rooms and services as well as federally qualified health centers.

Prescription Assistance Programs in North Carolina

The North Carolina Medication Assistance Program (NC-MAP) was created in 2003 to provide safety-net prescription coverage

Page 12

in North Carolina. According to a 2021 report published by the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS), MAP offered medication assistance services to more than 25,000 patients across the state in facilities such as rural health clinics, federally qualified health centers, and community and faith-based organizations. Many local MAPs in North Carolina are named after the county they serve and rely heavily on partnerships with local health systems to initiate referrals and plan fundraising events. Establishing evidence of MAPs’ efficacy in reducing emergency service use is instrumental to achieving buy-in from neighboring local health systems. By lowering costs to patients, hospitals, and taxpayers, MAPs strive to provide a win-win scenario for all stakeholders involved.

Despite having more than 100 active MAP sites in North Carolina, some of the most populous counties still lack access or have disproportionate access per capita (e.g., Orange County has no access sites while Duplin County has five access sites). This project aims to bridge some of the knowledge gaps regarding NC-MAP.

Factors Driving ER Visit Volume, What We Know and What We Don’t

This analysis focuses on multiple factors of interest that have the potential to impact ER visit volume per capita on a county level. One factor of interest is access to MAP sites on a county level which will be measured by calculating the number of MAP sites per capita. Additional factors that have

been shown in other studies to drive ER visit volume include county setting (urban vs rural) and the median age of the population. The latter two will be used as control variables.

While the project focuses on investigating the impact of all three factors of interest on ER visit volume, it also aims to provide further understanding of MAP site distribution among different counties including any disparities in access between urban and rural counties.

Research Question: Does access to North Carolina Medication Assistance Programs have an impact on healthcare use represented by local emergency room visit volume?

Research Hypothesis (H1): Counties with a higher number of MAP access sites have a lower rate of emergency room visits per capita. The hypothesis behind this assumption is that many visits to the emergency room result from patients not taking their prescription medications.

(4) By lowering prescription drug prices, patients are more likely to adhere to medication regimens (e.g., blood pressure-lowering medications), leading to better health outcomes (lower blood pressure) and fewer emergency room visits for high blood pressure. (Figure 1)

Page 13

Figure 1. Proposed logic model behind MAPs’ impact on ER visit volume.

Intended Audience

The findings of this study will impact local and state governments, including administrators within the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and will have implications on future policymaking relevant to building and staffing of emergency rooms and MAP access sites within a county. Furthermore, discovering such a correlation can be significant to local health systems interested in reducing cost of unnecessary emergency room visits and local emergency room wait times, and may incentivize health systems to collaborate with NCDHHS to expand access to NC-MAP locally, which will also be of benefit to the population at large.

Methods

All one hundred counties in North Carolina are included in this study. The volume of emergency room visits per capita within a county from September 2022 until August 2023 is available through the NC Detect ED initiative’s website. The NCDHHS website provides an updated list of MAP access sites with their location and addresses. While the total number of MAP sites has increased from 103 in 2021 to 115 in 2023, fewer counties currently provide MAP services (98 counties in 2021 compared to 67 in 2023) due to shifting MAP sites from certain counties to others.

County demographics, including population, median age, and setting, were all obtained using the NC Office of State Budget and Management’s website. To control for seasonal changes in ER visit volume, visit volume was collect-

ed over a 12-month period from September 2022 to August 2023 and provided data per capita.

Data were consolidated into a single sheet. Rows included the one hundred counties with their corresponding data points, including monthly ER visit volume, the county’s population, the county’s setting, the number of medication assistance sites per 100,000 population, and the county’s population median age. The county’s setting (urban/ rural) was assigned a value of either zero or one depending on their status, respectively. This dataset was then uploaded to the statistical analysis software SPSS, and linear regression analysis was conducted using variables mentioned above. In addition, a simple two-tailed t-test analysis was conducted to detect any difference in the number of medication assistance programs between rural and urban counties.

Results

Neither median age of the population nor number of medication assistance program sites within a county had a significant impact on ER visit volume per capita (t=-0.4, p=0.69 and t=-1.08, p=0.28, respectively). However, the statistical analysis showed the urban-rural environment of the counties did make a difference in the ER visit volume per capita (t=4.18, p<0.001).

Urban vs. Rural Divide and Impact on ER Visit Volume

Our analysis revealed rural counties had a higher ER visit volume per 100,000 population on average compared to urban counties. (Figure 2) Urban/Rural divide was the one factor out of the three originally highlighted (median age and number of MAP sites per capita) to have an impact on ER visit volume. Of note, other contributors to ER visit volume locally, such as urgent care openings and ambulance divergence, were not considered in this analysis. (1,5) When looking at the average ER visit volume per capita in rural counties vs urban ones, the former averaged 56,026 per 100,000 population compared to 44,056 per 100,000 population in the latter. In other words, emergency room visits per capita were approximately 25% higher in rural counties compared to their urban counterpart. We can conclude with higher than 99.9% confidence any difference in ER visit volume was not due to chance.

Page 14

Impact of Prescription Assistance Program on ER Visit Volume

To parse out the details of the urban/rural divide in access to MAPs, we investigated the difference in the number of MAPs between rural and urban counties. We found a rural population of 100,000 has access to an average of 4.1 medication assistance program sites, compared to 1.1 in its urban counterpart (Figure 3.). The difference was confirmed with higher than 99.9% confidence (p=0.00029).

The number of medication assistance program sites within a county was not a significant factor in determining emergency room visit volume on a local county level (t=-1.08, p=0.28). A higher number of MAPs within a county was associated with a modest increase in ER visit volume per capita, with the caveat these results did not reach the statistical significance threshold. This finding contradicts the research hypothesis, which assumes that increasing access to MAPs will lead to a reduction in ER visit volume per capita. One plausible explanation is emergency room visit volume is a result of a lack of access to primary care services and not a lack of access to prescription medications. Furthermore, while the increase in the median age of the population nationally has been shown to drive higher ER visit volume per capita, this was not the case in this analysis. (3) It is worth noting that most national studies that linked median age to ER visit volume were conducted in Medicaid and Medicare beneficiaries and not on a population-wide level.

Rural vs Urban Divide as a Main Driver of Disparity in Healthcare, Summary Analysis and Recommendations

While these results may come as a surprise, it is important to read these findings within the context of the urban/rural divide and understand the challenges to delivering high-quality care within rural counties:

Page 15

Figure 2. Rural counties had a higher ER visit volume per 100,000 population on average (56,026 per 100,000 population compared to 44,056 per 100,000 population in urban counties). Each person represents 10,000 people.

Figure 3. Disparities in access to medication assistance programs between rural and urban counties per capita. Each person represents 100,000 people.

1. Residents of rural counties use emergency services at a higher level compared to urban counties.

Most rural counties lack adequate access to urgent care and primary care services. Populations in rural communities are increasingly elderly; the average age for hospital admissions in rural settings is over 65, and these older patients comprise one-half of all admissions. Furthermore, patients treated in rural settings are more likely to be underinsured or uninsured. All these factors have the potential to drive patients to emergency rooms instead of seeking care in non-urgent outpatient settings. (6)

Recommendations: We recommend future analyses take into consideration access to primary care services as well as insurance coverage on a county level and their role in ER visit volume and use. This is more important than ever as Medicaid expansion goes into effect across the state of North Carolina. One challenge we anticipate is the fluid nature of insurance coverage within a population due to frequent changes in employment status and Medicaid eligibility.

2. Increased access to MAP sites in rural counties was not associated with lower ER visit volume per capita.

This finding contradicts the proposed logic model. One caveat is that higher numbers of MAP sites within a county may simply reflect declining insurance coverage and an increased need for prescription assistance within

rural populations. Unfortunately, NCDHHS does not provide any information regarding the decision-making logic behind MAP site distribution.

Recommendations: Moving forward, we recommend a follow-up study to monitor ER visit volume and use of prescription assistance programs on a county level before and after Medicaid expansion. Expanding insurance coverage within a county will reduce eligibility for prescription assistance programs but also has the potential to increase access to prescription medication and outpatient medical and behavioral services, which in turn may reduce the need for emergency services.

Providing a deeper understanding of factors driving emergency room service use will help local health systems and agencies plan better and provide equitable access to healthcare for residents across North Carolina. Requiring publicly funded programs to set goals that are specific, measurable, attainable, realistic, and timely (SMART) ensures responsible use of government resources and allows for a smooth evaluation process to determine whether a program has met its objectives.

Authors: Amro Ilaiwy, MD, is a Master of Public Administration Candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill School of Government; Maureen Berner, Ph.D., is a Professor of Public Administration and Government at UNC School of Government, Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The corresponding author is Dr. Ilaiwy at amroilaiwy@gmail.com

Acknowledgments: The authors do not report any relevant conflict of interest or financial support for this project.

References

1. Hsia RY, Zagorov S, Sarkar N, et al. Patterns in Patient Encounters and Emergency Department Capacity in California. JAMA Network Open, 2023;6(6):e2319438.doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.19438.

2. Hitzek J, Fischer-Rosinský A, Möckel M, et al. Influence of Weekday and Seasonal Trends on Urgency and In-hospital Mortality of Emergency Department Patients. Front Public Health. 2022;10:711235. Published 2022 Apr 25. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.711235

3. Greenwood-Ericksen MB, Kocher K. Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(4):e191919. Published 2019 Apr 5. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1919

4. Heaton PC, Frede S, Kordahi A, et al. Improving care transitions through medication therapy management: A community partnership to reduce readmissions in multiple health-systems. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(3):319-328. doi:10.1016/j.japh.2019.01.005

5. Carlson JN, Zocchi MS, Allen C, et al. Critical procedure performance in pediatric patients: Results from a national emergency medicine group. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(9):1703-1709. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.009

6. Nielsen M, D’Agostino D, Gregory P. Addressing Rural Health Challenges Head On. Mo Med. 2017 SepOct;114(5):363-366. https://www.ncbi. nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6140198/ Accessed 2/25/2024.

Page 16

Connecting Top Employers with Premier Professionals.

EMPLOYERS:

Find Your Next Great Hires

• PLACE your job in front of our highly qualified members

• SEARCH our resume database of qualified candidates

• MANAGE jobs and applicant activity right on our site

• LIMIT applicants only to those who are qualified

• FILL your jobs more quickly with great talent

NCAP CAREER CENTER

PROFESSIONALS: Keep Your Career on the Move

• POST a resume or anonymous career profile that leads employers to you

• SEARCH and apply to hundreds of new jobs on the spot by using robust filters

• SET UP efficient job alerts to deliver the latest jobs right to your inbox

• ACCESS career resources, job searching tips and tools

started today under the Career Center tab at ncpharmacists.org!

Get

New Drug - VelsipityTM (etrasimod)

By Olivia Hill and Gerell Harvey, PharmD Candidates

By Olivia Hill and Gerell Harvey, PharmD Candidates

2024

VelsipityTM (etrasimod), by Pfizer, Inc., is a sphingosine 1-phosphate (S1P) receptor modulator approved by the FDA on October 12, 2023, for the treatment of moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis (UC) in adults. (1)

Etrasimod binds with a high affinity to S1P receptors 1, 4, and 5. (1) Through binding to these receptors, etrasimod partially and reversibly blocks the ability of lymphocytes to exit from the lymphoid organs. The exact mechanism by which etrasimod has a therapeutic effect in UC is unknown, but it may involve the reduction in the movement of lymphocytes into the intestines. (1)

Etrasimod reaches maximum plasma concentrations within 2-8 hours (median time: 4 hours) after oral administration. There were no clinically significant differences in absorption observed after etrasimod was administered with food; therefore, it may be administered without regard to meals. Etrasimod is 97.9% protein bound; the mean apparent volume of distribution is 66 L. Etrasimod is metabolized by oxidation and dehydrogenation,

which are mediated primarily by CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4. CYP2C19 and CYP2J2 minorly contribute to metabolism. Conjugation also occurs primarily via UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGTs), with a minor contribution from sulfotransferases. The main component circulating in the plasma is unchanged etrasimod. The elimination half-life of estrasimod is approximately 30 hours, with 82% of radioactive drug in the feces and 5% in the urine. The pharmacokinetics of etrasimod are similar in people 65 years of age and older compared to younger adults. (1)

Etrasimod is contraindicated in anyone having a myocardial infarction, unstable angina pectoris, stroke, transient ischemic attack, decompensated heart failure requiring hospitalization, or Class III or IV heart failure within the last 6 months. (1) History or presence of Mobitz type II second- or third-degree atrioventricular (AV) block, sick sinus syndrome, or sino-atrial block, unless the patient has a functional pacemaker. (1)

Drug Interactions

Anti-arrhythmic drugs and QT-prolonging agents can cause a transient decrease in heart rate and delays in AV conduction when initiating etrasimod. Moreover, there is an increased risk of QT prolongation and Torsades de Pointes when etrasimod is used concomitantly with Class Ia and Class III antiarrhythmics and QT-prolonging drugs. (1,2)

Patients taking beta-blockers or calcium channel blockers may experience a transient decrease in heart rate and delays in AV conduction when initiating etrasimod. It is important to note that patients on a stable dose of their beta-blocker did not experience a reduction in heart rate. The manufacturer recommends consulting with a cardiologist if the patient is receiving etrasimod and is being considered for beta-blocker or calcium channel blocker therapy. (1,2)

There is a risk of additive immunosuppression when etrasimod is given concomitantly with other immunosuppressive therapies; therefore, it is recommended to avoid concomitant use during and in weeks after etrasimod administration by considering the elim-

Page 18

ination half-life and mechanism of action of any immunosuppressant. (1,2)

Etrasimod is primarily metabolized through CYP2C8, CYP2C9, and CYP3A4; therefore, it is suggested to avoid concomitant use with a moderate to strong inhibitor of CYP2C9 or inhibitor of CYP3A4. (1) In patients who are poor CYP2C9 metabolizers, the use of moderate to strong inhibitors of CYP2C8 or CYP3A4 inhibitors should be avoided. (1) Patients receiving etrasimod should avoid rifampin. (1,2)

Etrasimod is available as a 2 mg oral tablet. The recommended dose for the treatment of moderate to severe US is 2 mg orally one time daily with or without food. (1) The list price set by Pfizer Inc. is $6,164 for a 30-day supply. (3)

In clinical trials, patients receiving etrasimod 2 mg daily experienced headaches, elevated liver tests, dizziness, arthralgia, nausea, hypertension, bradycardia, UTI, hypercholesterolemia, and herpes viral infection more than patients receiving a placebo. (1,2)

A pregnancy exposure registry monitors pregnancy outcomes in females exposed to etrasimod during pregnancy. Pregnant females exposed to etrasimod are encouraged to contact the pregnancy registry. Based on findings from animal studies, etrasimod could potentially cause fetal harm. (1,2)

There is no data about the presence of etrasimod in human milk, its effects on a breastfed infant, or its effects on milk production.

When orally administered to female rats during pregnancy and lactation, etrasimod was detected in the plasma of offspring, which indicated excretion of etrasimod in milk. (1,2)

Etrasimod should be stored at 20°C to 25°C (68°F to 77°F); It is permitted to be stored between 15°C to 30°C (59°F to 86°F) during excursions. (1)

The clinical efficacy of etrasimod was studied by Sandburn et al. in two phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to assess the efficacy and safety of etrasimod in adult patients with moderately to severely active UC. The first trial examined etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE UC 12) enrolled patients from 407 centers across 37 countries. The second trial, ELEVATE UC 52, enrolled patients from 315 centers in 40 countries. (4)

Participants were eligible for both trials if they were between the ages of 16 and 80 years and had moderate to severe active UC (confirmed by endoscopy and modified Mayo Clinic score (MCS) of 4-9). Participants also needed to have a documented history of inadequate response, loss of response, or intolerance to at least one therapy approved for the treatment of UC. Patients with isolated proctitis at baseline who met other eligibility criteria could enroll in both ELEVATE UC 12 and ELEVATE UC 52, with enrollment capped at 15% of total patients. Patients were allowed to receive concomitant therapy with stable doses of aminosalicylates or cor-

ticosteroids for the treatment of UC, given that they were on a stable dose 2 weeks or 4 weeks prior to trial screening, respectively. (4)

Participants were excluded from these trials if they had been previously treated with at least three biological agents or at least two biologicals and a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor. Patients were also excluded if they were at high risk for requiring a colectomy within the next 3 months, had a history of myocardial infarction, stroke, or second- or third-degree AV block, had a history of opportunistic infections or macular edema, or were pregnant or breastfeeding. (4)

There were 354 participants in ELEVATE UC 12 that were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either once-daily oral etrasimod 2 mg or placebo. Participants were stratified by previous exposure to biologicals or JAK inhibitor therapy, baseline corticosteroid use, and baseline disease activity. Baseline characteristics were relatively similar among study groups in ELEVATE UC 12. The average MCS was 6.6 for both the etrasimod and placebo groups, with 46% of patients in both groups having an MCS of 4-6 and 54% of patients in both groups having an MCS of 7-9. The duration of UC diagnosis was 6.6 years for those in the etrasimod group compared to 7.3 years in the placebo group. Regarding previous therapies for UC treatment, 84% of patients in the placebo group had tried corticosteroid therapy compared to 74% in the etrasimod group. For 5-aminosalicylic acid, 73% of patients in the placebo group had previous-

Page 19

ly been on that medication compared to 63% in the etrasimod group. In both the etrasimod and placebo groups, 37% of patients had been previously exposed to biologicals or JAK inhibitors. At baseline, 33% of patients in both groups were being treated with corticosteroids. In the placebo group, 81% of patients were currently taking 5-aminosalicylic acid compared to 84% in the etrasimod group. The treatment was administered over a 12-week induction period with a 4-week follow-up period.

The primary endpoint for ELEVATE UC 12 was the proportion of patients in clinical remission at the end of the 12-week induction period. Key secondary endpoints for this trial included endoscopic improvement, symptomatic remission, and histological response at week 12. (4)

After 12 weeks, patients showed greater clinical improvement when treated with etrasimod compared to placebo. At the end of the 12-week induction period, 55 (25%) of 222 patients in the etrasimod group had clinical remission compared to 17 (15%) of 112 patients in the placebo group (p=0.026). Significant improvements at week 12 with etrasimod compared to placebo for the secondary endpoint of endoscopic improvement were 31% vs 19%, respectively (p=0.0092). Improvements in symptomatic remission with etrasimod vs placebo were 47% vs 29%, respectively (p=0.0013). Of those using etrasimod, 16% saw improvements in histological response compared to 9% of those using a placebo (p=0.036). (4)

ELEVATE UC 52 included 433 participants who were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio to receive either once-daily oral etrasimod 2 mg or placebo. Participants were stratified by previous exposure to biologicals or JAK inhibitor therapy, baseline corticosteroid use, and baseline disease activity. Baseline characteristics were relatively similar among study groups. The average MCS was 6.7 for both the etrasimod and placebo groups, with approximately 40% of patients in both groups having an MCS of 4-6 and approximately 60% of patients in both groups having an MCS of 7-9. The duration of UC diagnosis was 7.5 years for those in the etrasimod group compared to 5.9 years in the placebo group. In regard to previous therapies for UC treatment, 70% of patients in the placebo group had tried corticosteroid therapy compared to 78% in the etrasimod group. For 5-aminosalicylic acid, 66% of patients in the placebo group had previously been on that medication compared to 68% in the etrasimod group. In both the etrasimod and placebo groups, approximately 37% of patients had been previously exposed to biologicals or JAK inhibitors. At baseline, approximately 33% of patients in both groups were being treated with corticosteroids. In the placebo group, 77% of patients were currently taking 5-aminosalicylic acid compared to 79% in the etrasimod group. In ELEVATE UC 52, there was a 12-week induction period followed by a 40-week maintenance period and a 4-week follow-up period. (4)

The co-primary endpoints of ELEVATE UC 52 were the proportion

of patients in clinical remission at the end of week 12 and week 52. Key secondary endpoints of this trial were the same as ELEVATE UC 12, along with corticosteroid-free and sustained clinical remission being assessed at week 52. A larger portion of those treated with etrasimod compared to placebo experienced clinical remission at the 12-week induction period (27% vs. 7% respectively, p<0.0001) and at week 52 (32% vs. 7% respectively, p<0.0001) in ELEVATE UC 52. At week 52, those treated with etrasimod showed significant improvement in key secondary endpoints compared to those treated with placebo. Regardless of corticosteroid use at baseline, 32% vs 7% of patients treated with etrasimod compared to placebo, respectively, experienced corticosteroid-free remission for at least 12 weeks (p<0.0001). More patients experienced sustained clinical remission when treated with etrasimod compared to placebo (18% vs 2% respectively, p<0.0001). (4)

Overall, ELEVATE UC 12 and ELEVATE UC 52 both showed that etrasimod had clinical efficacy in patients with moderately to severely active UC at weeks 12 and 52. The most common adverse effects seen in ELEVATE UC 12 were anemia (6%), headache (5%), nausea (4%), and worsening of UC or UC flare (4%). The most common adverse effects seen in ELEVATE UC 52 were anemia (8%), headache (8%), dizziness (5%), and worsening of UC or UC flare (8%). These studies concluded that etrasimod was safe and effective for the treatment of moderately to severely active UC. (4)

Page 20

A phase 2, proof-of-concept, double-blind, parallel-group study was also done to research the efficacy and safety of etrasimod in patients with UC. Participants from 87 centers in 17 countries were included in this study, which took place from October 15, 2015, through February 14, 2018. Participants were eligible if they were between the ages of 18 and 80 years old with UC and an MCS of 4-9, which included a centrally read endoscopic subscore of greater than or equal to 2 and a rectal bleeding subscore of greater than or equal to 1. Patients who had diseases limited to only the rectum were excluded from the study. (5)

One hundred and fifty-six total patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 fashion to receive either oral etrasimod 1 mg, etrasimod 2 mg, or placebo one time daily for 12 weeks. Of the total randomized patients, 141 patients completed the full 12-week treatment study trial. The mean baseline modified MSC was between 6.5 and 6.6. Between 25-36% of the patients in the study were taking oral corticosteroids at the time of the study. In the study, patients were assessed for efficacy at both baseline and week 12 using the MCS. (5)

The primary efficacy endpoint was improvement in the modified MCS from baseline to week 12. Secondary efficacy endpoints included the proportion of patients at week 12 that achieved endoscopic improvement (defined as an endoscopic subscore of <1 point), improvement in the 2-component MCS (0-6 range, including rectal bleeding and endos-

copy findings), and improvement in the total MCS (0-12 range, composed of the modified MCS plus Physician Global Assessment). (5) Regarding the primary endpoint, at week 12, the least squares mean (LSM) for improvement in the modified MCS was 1.94, 2.49, and 1.50 points for the etrasimod 1 mg, etrasimod 2 mg, and placebo groups, respectively. There was a significant LSM difference of 0.99 in the modified MCS between the etrasimod 2 mg group compared with placebo at week 12 (p=0.009). (5) The LSM difference between etrasimod 1 mg and placebo was 0.43 (p=0.15).

(5) Regarding the secondary endpoints, 41.8% of patients who took etrasimod 2 mg had endoscopic improvement as opposed to 17.8% of patients who took a placebo (p=0.003). (5) Of the patients that took etrasimod, 22.5% of them had endoscopic improvement in comparison to 18.5% of patients taking placebo (p=0.31).

(5) The LSM difference for the 2-component MCS between the etrasimod 2 mg and placebo groups was 0.84 (p=0.002). (5) The etrasimod 1 mg group had a 0.39 difference from the placebo group. The total MCS had an LSM difference of 1.27 between the etrasimod 2 mg and placebo groups (p=0.010). (5) The etrasimod 1 mg and placebo groups had a 0.60 difference (p=0.13).

(5) The most reported adverse events included worsening of UC, upper respiratory tract infection, nasopharyngitis, and anemia. (5) The conclusion of this study was that etrasimod 2 mg was more efficacious than placebo in the improvement of modified MC at week 12 in patients with moderately to severely active UC. (5)

Summary/Clinical Applications

The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recommend the use of tumor necrosis factor blocking agents (infliximab, adalimumab, and golimumab), integrin receptor antagonists (vedolizumab), and Janus kinase inhibitors (tofacitinib) for the induction and maintenance of remission in moderate to severe UC. Their guidelines also mention concomitant corticosteroid therapy to help induce remission. (6.7)

The current 2020 AGA and 2019 ACG guidelines do not include S1P receptor modulators, as the first S1P receptor modulator approved for moderate to severe UC (ozanimod) was not approved until 2021. (1) Ozanimod is administered orally, with an initial dose of 0.23 mg once daily on days 1 through 4, then 0.46 mg once daily on days 5 through 7, and a final maintenance dose of 0.92 mg starting on day 8. (8) Other S1P receptor modulators available include fingolimod, ponesimod, and siponimod, none of which are FDA-approved for UC.

Etrasimod is the newest addition to the S1P receptor modulators, and clinical trials have shown it to be a safe and effective option for the treatment of moderate to severely active UC in adults. (1,4,5) Another study is actively recruiting to test the safety and efficacy of etrasimod for UC in children. Additionally, etrasimod is also being studied as a potential agent in the treatment of Crohn’s Disease.

Currently, there is insufficient evidence to support the use of etra-

Page 21

simod in adolescents. (1) There is also insufficient safety data to support the use of etrasimod in pregnant or lactating patients. (1) Based on findings from animal studies, this drug could potentially cause fetal harm. There are currently no dosage adjustments recommended for patients with renal dysfunction. Those with severe hepatic dysfunction (ChildTurcotte-Pugh Class C) should not use etrasimod. (1)

Patients should be counseled to take this medication at the same time each day, without regard to food. (1) Before taking this drug, patients should inform their healthcare provider of any antiarrhythmics, QT-prolonging medications, immunosuppressive agents, and moderate to strong CYP2CP and CYP3A4 inhibitors they are currently taking. (1) The most common adverse effects seen with etrasimod include headache, dizziness, nausea, elevated liver tests, and arthralgia. (1)

Authors: Olivia Hill is a PharmD Candidate in the Class of 2024 at Campbell University College of Pharmacy & Health Sciences. Gerell Harvey is a PharmD Candidate in the Class of 2024 at the Campbell University College of Pharmacy & Health Sciences. The corresponding author is Olivia Hill, orhill0603@email.campbell. edu.

Labeling.aspx?id=19776. Accessed November 5, 2023.

2. Important safety information and indication. Velsipity Official Patient Website. https://www.velsipity. com/important-safety-information. Updated 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

3. Chiorean M. Pfizer’s Velsipity Approved for Ulcerative Colitis. FormularyWatch. https://www. formularywatch.com/view/pfizer-s-velsipity-approved-for-ulcerative-colitis. October 13, 2023. Accessed November 28, 2023.

4. Sandborn WJ, Vermeire S, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Etrasimod as induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis (ELEVATE): two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 studies. Lancet. 2023; 401:1159-1171. doi:10.1016/ S0140-6736(23)00061-2.

5. Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L,

Zhang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Etrasimod in a phase 2 randomized trial of patients with ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(3):550-561. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.035

6. Feuerstein JD, Isaacs KL, Schneider Y, et al. AGA Clinical Practice Guidelines on the Management of Moderate to Severe Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:1450-1461. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2020.01.006.

7. Rubin DT, Ananthakrishnan AN, Siegel CA, et al. ACG Clinical Guideline: Ulcerative Colitis in Adults. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:384-413. doi:10.14309/ ajg.0000000000000152.

8. Ozanimod [package insert online]. Celgene Corporation; Princeton, NJ; Revised August 2023. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/fda/ fdaDrugXsl.cfm?setid=93ce2fab-ed-

References:

1. Velsipity (etrasimod) tablet [package insert online]. Pfizer Inc., New York, NY; Revised October 2023. https://labeling.pfizer.com/Show-

Page 22

•

•

•

•

•

Protect your Tomorrow with VISTA LEARN MORE AT: phmic.com/vista-pharmacy Executive Liability, Surety and Fidelity Bonds, Personal, Life, and Disability insurance are written through PMC Advantage Insurance Services, Inc., a whollyowned subsidiary of Pharmacists Mutual Insurance Company. Our VISTA business package policy protects your tomorrow with:

Commercial Liability

Cyber Liability

Sexual Misconduct and Physical Abuse

Employment Practices Liability

Commercial Property

Coverage Enhancements Additional Coverage Options • Professional Liability • Workers Compensation • Commercial Auto • Commercial Umbrella • Executive Liability including: • Directory and Officers Liability • Employment Practices Liability • Fiduciary Liability • Surety and Fidelity Bonds • Life - Business and Personal Coverage • Group Disability Professional | Commercial | Personal | Life | Disability phmic.com

•

Apply for NCAP Fellow Status

Deadline April 1st

Have you achieved Fellow status with NCAP? Not sure? Find out the requirements to earn the FNCAP credential and apply. The application deadline is April 1, 2024. Those earning NCAP Fellow status will be recognized and pinned at the 2024 Annual Convention, June 24 - 26 in Cary, NC. The Awards Ceremony will be on June 24th. This recognition program is open to pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.

Get Those Award Nominations Submitted Deadline April 1st

It’s time to nominate that colleague who always gives 110%. They work hard to give the best care to their patients and support their fellow staff and community. Nominate that awesome pharmacist, pharmacy student, or pharmacy technician for one of the awards described here. Nominees need to be a member of NCAP. Award recipients will be announced at the 2024 Annual Convention, June 24 –26.

Final Leadership Buzz Book Discussion April 9th

If you’ve been participating in NCAP’s New Practitioner Forum’s Leadership Buzz book discussions, the final one for this series is Tuesday, April 9 from 5 – 6 pm. All registrants will receive their meeting link the week of the discussion. The book is “Op-

tion B: Facing Adversity, Building Resilience, and Finding Joy.” The discussion will be led by Killian Rodgers.

Scientific Poster Abstract Submission Deadline April 15th

The 9th Annual Scientific Posters showcase will be presented during our annual convention’s Pharmacy Expo & Posters Extravaganza on Monday, June 24, 2024. A limited number of posters will be accepted this year. The exact details for the session are still being planned. For more information on how to submit your abstract and an example of a structured abstract, visit our convention website and click on the Call for Posters button. All abstracts chosen to present at the convention will be published in an upcoming edition of this journal.

Registration is open for the 2024 NCAP Annual Convention

This year’s convention theme is “Off the Beaten Path: Trekking Toward Transformative Practice” and aims to arm you with everything you need to elevate your practice. This convention is for any pharmacy professional working in any area of practice. We will have breakout sessions that speak specifically to each academy’s needs; workshops on front-burner topics like immunizations, opioids, diabetes, and more; and this year, we have state-level leaders from various organizations participating in panel and general sessions including Dr. Elizabeth Tilson, State Health Director and Chief Medical Of-

Page 24

ficer for the NC Department of Health and Human Services. You do not want to miss this year’s convention at the Embassy Suites Raleigh Durham Research Triangle in Cary, NC! For more information, visit our convention website. See you there!

Mark Your Calendars – Upcoming Webinars

The NC Association of Pharmacists is proud to present you with live webinar opportunities through our Sunday Evening Webinar Series. Each month, with the exception of June when we will hold our annual convention, we present a live webinar. Mark your calendar for the following dates and topics. Watch our webpage for details to know when registration for each webinar is opened.

Sunday, April 21st

The topic will be asthma and will be presented by Tara McGeehan, PharmD

Sunday, May 19th

The topic will be sexually transmitted infections and will be presented by Rey Perez, MD.

June

Convention Month

No webinar

Sunday, July 21st

The topic will be multiple sclerosis and will be presented by Cori Shope, PharmD

Page 25

Increased Access to Sickle Cell Therapies

On February 23, the NCDHHS announced they will pursue participation in the new Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ Cell and Gene Therapy Access Model, which will focus on access to recently approved gene therapies (e.g., Casgevy and Lyfgenia) for people on Medicaid living with sickle cell disease (SCD). These therapies are estimated to cost $2 million per person through Medicaid; thus, they are inaccessible to many people with SCD. Notably, both therapies were found to reduce or eliminate the extreme pain crises experienced by people living with SCD. The Cell and Gene Therapy (CGT) Access Model aims to improve health outcomes by supporting outcomes-based agreements that will provide treatments within a framework that lowers prices for states and ties payment to outcomes. Participation in the CGT Access Model aims to increase access to cell and gene therapies and lower healthcare costs while decreasing taxpayer costs.

FDA Withdraws Approval of Pepaxto

On February 23rd, the FDA announced its final decision to withdraw approval of Pepaxto (melphalan flufenamide), which was approved for use in combination with dexamethasone to treat certain patients with multiple myeloma. In August, a post-approval confirmatory trial (a condition of Pepaxto’s approval) failed to demonstrate clinical benefit, while evidence failed to prove safety or efficacy under its condition of use.

NC Launches a New Statewide Peer Warmline

Effective February 20, The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NCDHHS) launched a new statewide Peer Warmline. Peer Support Specialists (or “peers”) are people living in recovery with mental illness and/or substance use disorder who provide support to others who can benefit from their lived experience. The additional phone support works with the North Carolina 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline by allowing callers to speak with a Peer Support Specialist. These Peer Support Specialists offer non-clinical support and resources to those in crisis. Their unique expertise helps reduce stigma while strengthening overall engagement in care.

NC Expands Access to Treatment for Syphilis

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services is raising awareness among providers and patients of a recent rate increase to support treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries. As of February 1, the Medicaid reimbursement rate has been increased to reflect the updated costs of Bicillin L-A (penicillin G benzathine), which can be used to treat syphilis and is the only known effective treatment for preventing congenital syphilis. NC Medicaid also covers Extencilline (powdered benzathine benzylpenicillin) to address the ongoing national penicillin G benzathine (Bicillin L-A) shortage.

ncpharmacists.org Page 26

FDA Warns Against Using Smartwatches or Smart Rings to Measure Blood Glucose Levels

On February 21, the FDA released a safety alert warning patients about the dangers of smartwatches or smart rings that claim to gauge blood glucose levels without requiring the user to pierce their skin. Although numerous models have flooded the market, none are sanctioned by the FDA. The agency said they can produce inaccurate readings with the potential to create harm.

For patients who rely on accurate blood glucose measurements to manage their diabetes, healthcare providers should direct them to appropriate FDA-authorized devices. Data from authorized devices may be transferred and displayed via applications on some smartwatches or smart rings, which the FDA clarifies are not the target of its safety communication. Their warning applies only to unauthorized devices that claim to measure blood glucose through noninvasive methods.

FDA Adds Boxed Warning to Denosumab for Patients with Advanced CKD

On February 1, the FDA announced the addition of a boxed warning to denosumab (Prolia). For patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD)—especially those on dialysis or those with a concomitant diagnosis of mineral and bone disorder, the FDA said they could develop severe hypocalcemia. The labeling change includes a boxed warning to reflect the risk of hospitalization and even death for this group of patients. Information in the package insert advises both patients and providers on strategies to curtail the risk of harm, including a recommendation to evaluate kidney function in patients before prescribing denosumab, emphasis on the importance of sufficient calcium and vitamin D intake for current users, and a recommendation for frequent monitoring of blood calcium levels for patients with advanced CKD.

First Interchangeable Biosimilar to Humira (adalimumab-ryvk)

The FDA-approved adalimumab-ryvk (Simlandi; Alvotech, Teva Pharmaceuticals) injection as the first interchangeable high-concentration, citrate-free biosimilar to adalimumab (Humira, AbbVie). Accord-

ing to the FDA, an interchangeable biosimilar may be substituted at the pharmacy for the reference product without the intervention of the prescribing healthcare provider, much like how generic drugs are routinely substituted for brand-name drugs.

Adalimumab-ryvk was approved to treat adult rheumatoid arthritis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, adult psoriatic arthritis, adult ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, adult ulcerative colitis, adult plaque psoriasis, adult hidradenitis suppurativa and adult uveitis. As an interchangeable biosimilar, it can be substituted for adalimumab at the pharmacy level.

Assistive Technology for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing

Although the Division of Services for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (DSDHH) does not endorse any of the products or companies listed on the NCDHHS website, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians can employ a number of potentially useful resources when communicating with patients needing hearing accommodations.

Page 27 Click Here To Donate To NCAP NCAP Advocacy Advocacy Fund Fund Your support drives positive change in our profession! ncpharmacists org ncpharmacists.org Generous contributions have helped us to achieve huge success during the 2023 legislative session.

Law Enforcement Access to Protected Health Information – What’s Your Policy?

Understanding and adhering to the HIPAA Privacy Rule is required for covered entities who handle protected health information (PHI), but because the Privacy Rule was designed to be flexible, implementation of policies and procedures to meet the Privacy Rules can vary from covered entity to covered entity. Look no further than the December 12, 2023 letter1 from the United States Senate Committee on Finance (herein, “The Committee”) for evidence of this variation and how it can seriously impact the privacy of sensitive patient data.

In the December letter drafted to Xavier Becerra, Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, The Committee outlined the results of their oversight inquiry into the seven largest pharmacy chains (CVS Health, Walgreens Boots Alliance, Cigna, Optum Rx, Walmart Stores, Inc., The Kroger Company, and Rite Aid Corporation), and Amazon Pharmacy. The inquiry focused on obtaining briefings from the major pharmacy chains about their policies and procedures for releasing PHI to law enforcement agencies. Below is a general overview of the findings:

• Five pharmacy corporations had policies that would require a law enforce-

ment agency’s demand for PHI to be reviewed by legal professionals before responding

• The remaining three pharmacy corporations had policies that put “extreme pressure” on the pharmacy staff to respond to the inquiries immediately and stated their pharmacy staff “are trained to respond to such requests and can contact the legal department if they have questions”

• None of the pharmacy corporations required warrants to share information with law enforcement agencies, unless required by state law

• Pharmacies would turn over PHI to a law enforcement agency when presented with a subpoena (“which often do not have to be reviewed or signed by a judge prior to being issued”)

• Only CVS Health published annual transparency reports on the records requests from law enforcement

• Patients already have the right to know who is accessing their health information through the HIPAA Accounting of Disclosure process, but the obligation is on the patient or their authorized representative to request the appropriate information from the covered entity; since this patient right is not well known in the general patient population it leads to a very small number of disclosure requests annually

The Committee urged the Secretary to strengthen HIPAA Privacy regulations to better protect PHI, and referenced a 2010 decision2 from the Federal Court of Appeals which protected the privacy of emails and would require a warrant before providers such as Google, Yahoo, and Microsoft could release customer data.

What does this mean for independent pharmacies? As stated in The Committee’s letter, “These findings underscore that not only are there real differences in how pharmacies approach patient