TEACH • HEAL • DISCOVER TheOath

FALL 2022

‘This Procedure Saved His Life’ How NC State’s nephrology expertise rescued Max

Inhalable COVID-19 Vaccine Shows Promise Next Step For Nephrology and Urology Meet the Class of 2026 Three Pembroke Scholars On A Pathway To Success

CVM Wins USAID Grant for Interdisciplinary Poultry Project in Ethiopia

Intentionally, Strategically, Collaboratively, NC State Situated for Research To Soar

When Rare Isn’t a Strong Enough Word

2

This Issue

4| 6 | 12 | 14 | 16 | 22 | 26 |

From the Dean

The mission of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is to enhance animal and human health through education, leadership, and innovation. Innovation drives almost everything we do as it has since the college opened.

In many ways we are fortunate to be one of the younger colleges of veterinary medicine in the country (our first class graduated in 1985). We are young enough that our community is still willing to allow us to continue to change. This gives us a freedom to make changes and contin ually try to improve, whether in how we deliver clinical medicine to our patients, how we train our students and house officers or how we practice medicine.

I am particularly proud of this aspect of our culture. We are not afraid to try something new if we think it can be done better. At the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, we are innova tors, we are problem-solvers and we are life-changers.

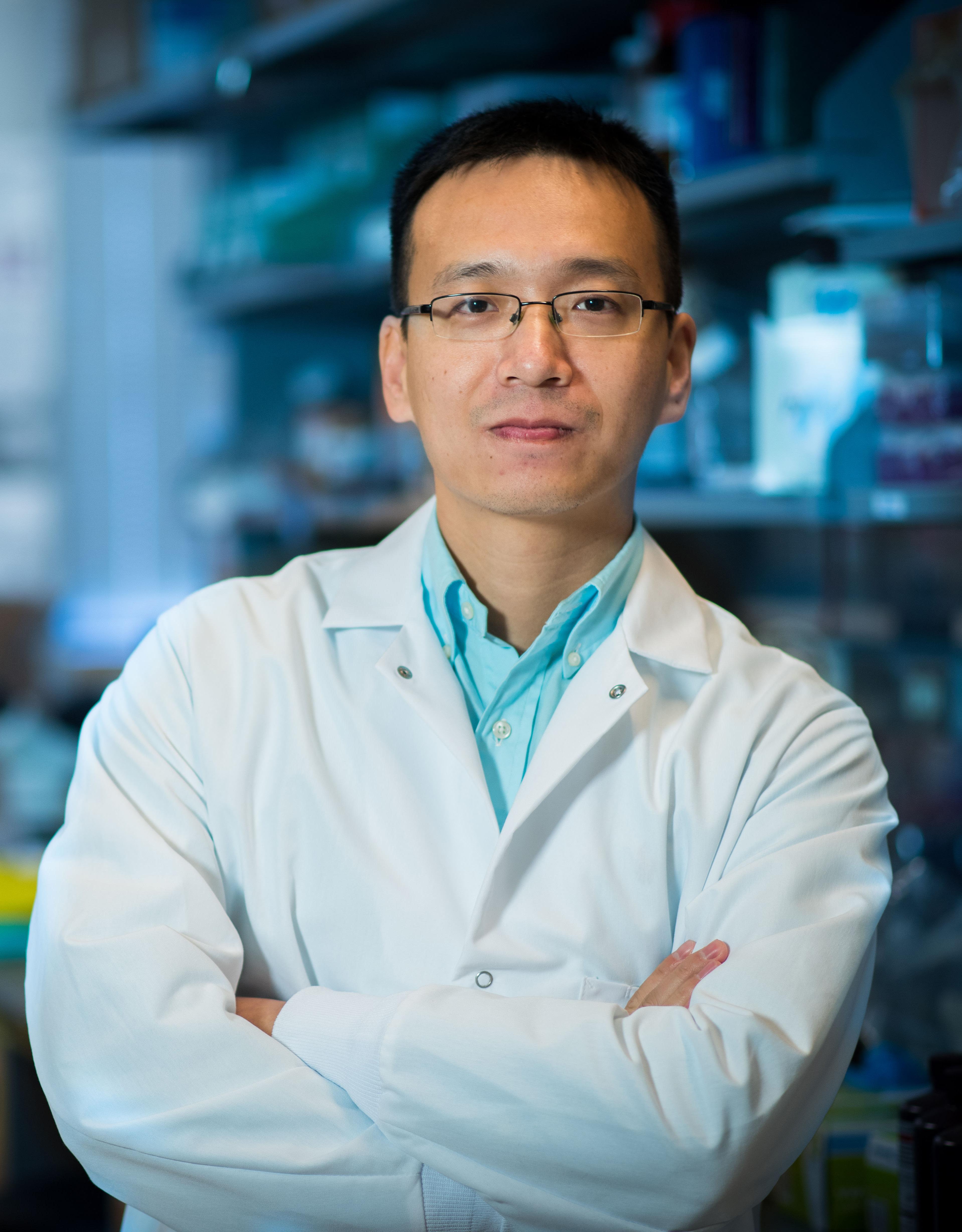

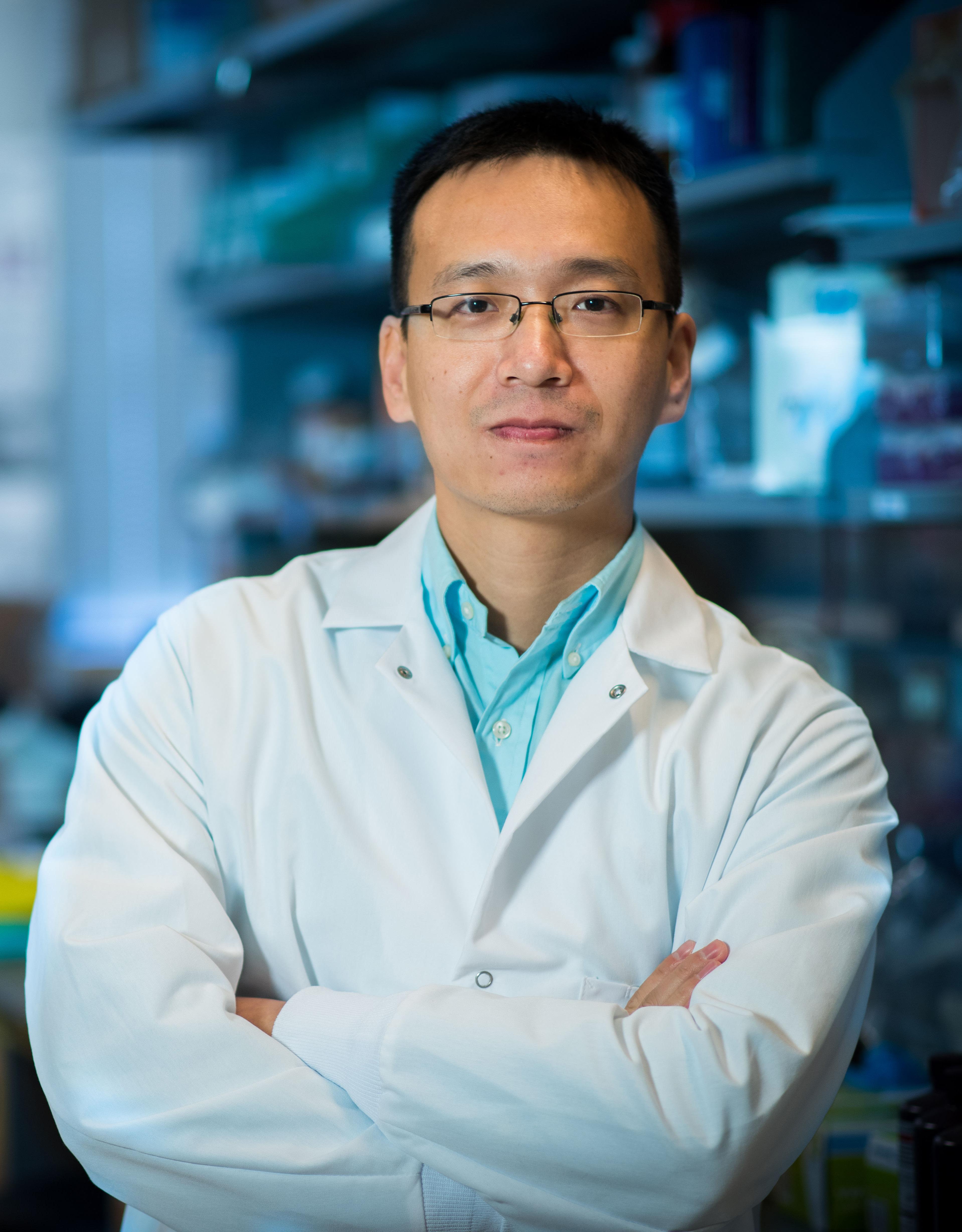

In this edition of the Oath, we highlight a few of these innovations. Dr. Ke Cheng’s discovery of an inhalable COVID-19 vaccine, stable at room temperature and easy enough to use that it can even be self-administered, is an amazing example of this. Dr. Cheng is an innovator who assessed the problems with the current vaccine technology and was creative enough to develop a life-changing solution for preventing this deadly virus. Now Dr. Cheng, a faculty member in the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences, will turn his cutting-edge solution to animal health and use this new vaccine technology to help improve veterinary medicine.

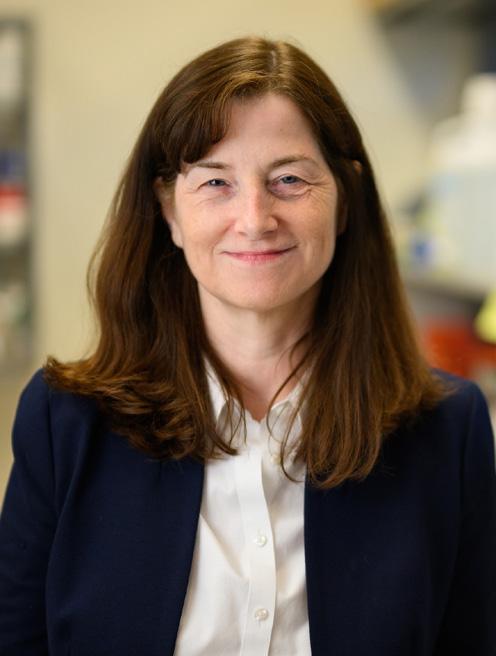

Dr. Shelly Vaden is another excellent example of leadership and innovation. Dr. Vaden has been a key member of our internal medicine service for many years and has been a life-changer for thousands of patients. Her own research in nephrology and urology has resulted in signifi cant innovation that has improved animal health.

Most recently, Dr. Vaden was instrumental in developing a new American College of Veteri nary Internal Medicine Specialty in Veterinary Nephrology and Urology. Elevating this area of veterinary medicine to a specialty college will bring new education and research focus on this significant and expanding area. Dr. Vaden will bring her leadership to help this new specialty build momentum by becoming the college’s first president-elect. This is another excellent ex ample of someone who identified a problem, in this case in the way the profession focused its teaching, research and service areas, and worked to create a solution.

Finally, I am extremely proud of how we apply our innovative, problem-solving and life-chang ing philosophy to our educational program as well. We understand that the education we provide our students and house officers directly impacts their ability to be good doctors and life-changers in their new careers. This is why we are in the process of updating our curriculum to reorganize existing material into larger, integrated sequences and to expand experiential, hands-on learning.

At the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, we are proud to be innovators, problem-solv ers and life-changers.

Kate

3

Inhalable COVID-19 Vaccine Shows Promise

BY TRACEY PEAKE NC STATE UNIVERSITY NEWS

Researchers have created an inhalable COVID-19 vaccine that is shelf stable at room temperature for up to three months, targets the lungs specifically and effectively, and allows for self-administration via an inhaler.

The researchers also found that the delivery mechanism for this vaccine – a lung-derived exosome called LSC-Exo – is more effective at evading the lung’s mucosal lining than the lipid-based nanoparticles currently in use and can be used effectively with protein-based vaccines.

Ke Cheng, the Randall B. Terry Jr. Distinguished Professor in Regenerative Medicine at NC State and a professor in the NC State/UNC-Chapel Hill Joint Department of Biomed ical Engineering, along with colleagues from UNC-Chapel Hill and Duke University, led the development of the vac cine prototype from proof-of-concept to animal studies.

“There are several challenges associated with vaccine delivery we wanted to address,” Cheng says. “First, taking the vaccine via intramuscular shot is less efficient at getting it into the pulmonary system and so can limit its effica cy. Inhaled vaccines would increase their benefit against COVID-19.

“Second, mRNA vaccines in their current formulation re quire cold storage and trained medical personnel to deliver them. A vaccine that is stable at room temperature and that could be self-administered would greatly reduce wait times for patients as well as stress on the medical profession during a pandemic. However, reformulating the delivery mecha nism is necessary for it to work through inhalation.”

In order to deliver the vaccine directly to the lungs, the re searchers used exosomes (Exo) secreted from lung spheroid cells (LSCs).

Exosomes are nanosized vesicles that have recently been recognized as an excellent means of drug delivery.

First, the researchers looked at whether LSC-Exo was able to deliver protein or mRNA “cargos” throughout the lungs. The researchers compared the distribution and retention of LSC-Exo with nanoparticles similar to lipid nanoparticles currently used with mRNA vaccines. In a paper in Extracel lular Vesicle, the researchers demonstrated that lung-derived nanoparticles were more effective at delivering mRNA and protein cargo to bronchioles and deep lung tissue than syn thetic liposome particles.

Next, the researchers created and tested an inhalable, pro tein-based, virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine by decorating the exterior of LSC-Exo with a portion of the spike protein – known as the receptor binding domain, or RBD – from the SARS-CoV-2 virus. A paper describing the research is published in Nature Biomedical Engineering.

“Vaccines can work through various means,” Cheng says. “For example, mRNA vaccines deliver a script to your cell that instructs it to produce antibodies to the spike protein. This VLP vaccine, on the other hand, introduces a portion of the spike protein to the body, triggering the immune system to produce antibodies to the spike protein.”

In rodent models, the RBD-decorated LSC-Exo vaccine (RBD-Exo) elicited production of antibodies specific to the RBD and protected the rodents, after two vaccine doses, from infection with live SARS-CoV-2. Additionally, the RBD-Exo vaccine remained stable at room temperature for three months.

The researchers note that while the work is promising, there are still challenges associated with large-scale production and purification of the exosomes. LSCs, the cell type used for generating RBD-Exo, are currently in a Phase I clini cal trial by the same researchers for treating patients with degenerative lung diseases.

“An inhalable vaccine will confer both mucosal and systemic immunity, it’s more convenient to store and distribute, and could be self-administered on a large scale,” Cheng says. “So while there are still challenges associated with scaling up production, we believe that this is a promising vaccine worthy of further research and development.”

The work was supported by the National Institutes of Health and the American Heart Association. North Car olina State University has filed a provisional patent on the technologies reported in those publications, and the patent right has been exclusively licensed to Xsome Biotech, an NC State startup company co-founded by Cheng.

4

Recognizing that the field of veterinary nephrology and urology has grown in complexity and vision, the AVMA American Board of Veterinary Specialties provisionally approved a petition to elevate the field to a new specialty college.

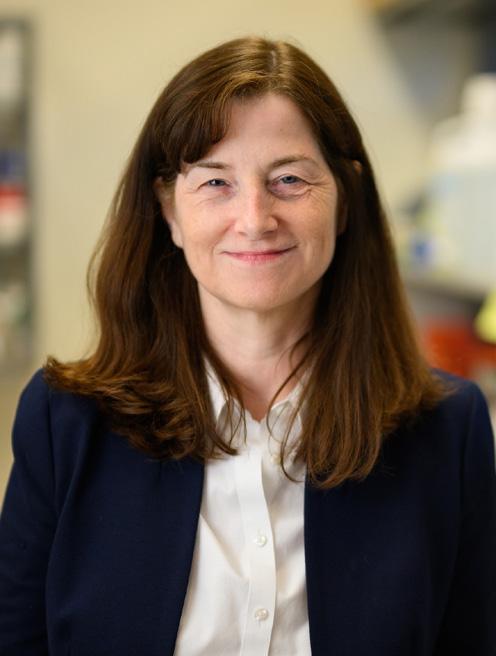

Shelly Vaden, professor of internal medicine at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, is president-elect of the new American College of Veterinary Nephrology and Urology, which will be able to apply for permanent status after four years.

“The field of veterinary nephrology and urology has grown exponentially over the past 15 to 20 years so this is a very exciting opportunity to pull all the people together who are making these changes and devoting clinical time to the field so we can contin ue to make clinical advances,” says Vaden, whose clinical and research focus has been on the upper and lower urinary tract of the dog. “We’ve become so advanced with urinary procedures, and many of these require training beyond residency training to develop proficiency.”

A large part of what the specialty college will do is formalize and oversee training programs, Vaden says. Nephrology and urology have always been an important part of internal medicine.

Nephrology fellow Tanner Slead, left, and professor Shelly Vaden consult during a bladder cystoscopy of a veterinary medicine patient.

6

The ACVNU will allow internists and criticalists to pursue advanced training in nephrology and urology, beyond what they would receive in their internal medicine or emergency or critical care residencies.

NC State was one of the first veterinary colleges in the Unit ed States to offer focus clinics in nephrology and urology, Vaden says. Now the college has added fellowship training programs to that clinical service. In July, Tanner Slead, who completed a residency in small animal internal medicine at NC State, became the first fellow in nephrology and advanced urological procedures at the College of Veterinary Medicine. In August, Andre Le Sueur became a fellow in extracorporeal therapies. Fellowships offer advanced train ing in a specialized discipline, beyond what can be learned in a traditional three-year residency program.

As part of NC State’s nephrology and urology team, the fellows joined Vaden, director of extracorporeal therapy service; Yu Ueda, assistant professor of emergency and critical care and associate director of dialysis and apheresis; and Allison Kendall, assistant clinical professor of internal medicine who has advanced training in urological interven tional procedures.

The petition in support of having nephrology and urology recognized as a specialty college, written by an organiz ing committee that included Vaden and Bernie Hansen, professor of emergency/critical care at NC State, cited how advancements in the research and understanding of urinary tract diseases have led to innovations in diagnostic methods and disease management.

“These advances include, but are not limited to chronic kidney disease, acute kidney injury, glomerular diseases, urolithiasis, urinary tract infection, incontinence, and urologic neoplasia,” the petition said. “The evolution of sophisticated techniques including extracorporeal therapies and endourology have become the advanced standards-ofcare for many urinary tract diseases.”

More veterinary hospitals throughout the world now offer dialysis for dogs and cats, and urinary tract diseases that previously required surgery now can be managed less inva sively. At the NC State Veterinary Hospital, the treatment offerings include diagnostic and therapeutic cystoscopy, nonsurgical stone retrieval and removal, endoscopic ure thral bulking for incontinent dogs and urethral and ureteral stenting and ballooning for neoplasia, strictures, obstruc tions or infections.

“The internal medicine speciality is a large part of veteri nary medicine, but the addition of the new specialty college allows us to become tailored experts in nephrology and urology,” Kendall says. “This is so exciting for our patients because it provides top of the line speciality care that they won’t be able to receive anywhere else. I am so excited to bring this to our patients at the NC State CVM and to be an early leader in this field.”

“We’re continuing to expand capabilities and learn new techniques,” Vaden says. “The ACVNU provides recogni tion to those veterinary centers, including NC State, that have dedicated experts in this field.”

Ueda cited a local case of a dog whose kidneys were dam aged when it was trapped inside a hot car.

8

“The local emergency veterinary hospital called us just this morning with a young Yorkshire terrier that had suffered heat stroke and severe acute kidney injury requiring hemo dialysis treatment to save his life,” Ueda says. “NC State is the only hospital offering hemodialysis treatment for dogs and cats in this area so they called us for help.”

Ueda says the closest veterinary hemodialysis centers to NC State are in Washington, D.C., and Florida.

The ACVNU will differ from other specialty colleges within veterinary medicine in that members will need to be board-certified in another discipline or have at least four years of experience in the field.

For example, Kendall and Vaden are board certified in internal medicine, and Ueda is board certified in emergency and critical care.

“When animals have diseases in other systems of the body, the kidneys are affected,” Ueda says. “It’s very important to understand nephrology but also to understand the interac tions with other organ systems.”

The ACVNU will offer two certifications: diplomate status for candidates with backgrounds in patient care such as internal medicine and emergency and critical care, and

affiliate membership for those with nonpatient care back grounds such as pathology, clinical pathology and clinical nutrition.

Kendall says veterinary medicine continues to follow the lead of specialization seen with human medicine.

“Similar to human medicine, it is challenging to be an expert in all fields,” she says. “Having more focused training in a specific area is going to drastically improve the quality of care in veterinary medicine by creating experts in these fields. I think the College of Nephrology and Urology is leading the way for more hospitals to enhance the level of care we provide.”

As the specialty college’s president-elect, Vaden has a lot of work to do to get the new ACVNU up and running, and she’s excited that her field has reached the next level of recognition.

“The whole premise of having a specialty college is to con tinue to expand the knowledge in the field,” she says. “The idea is that we organize and we work together with other universities and hospitals to expand our understanding of the diseases that affect the kidneys and the urinary tract and develop better ways to diagnose and manage those, all while training new specialists in the field.”

9

Yu Ueda, assistant professor of emergency and critical care and associate director of dialysis and apheresis, performs dialysis on a patient.

Kind of Gave Us a Very Grim Outlook’ then NC State Saved the Day

BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER

Lenny and Sylvia Chin are so eager to explain how the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine saved the life of their dog Max that they both get on the phone from their home in Waxhaw, North Carolina, and try to talk at once.

“It was critical,” Sylvia says of the day in January when Lenny hurried almost three hours to Raleigh with Max, a miniature Australian Labradoodle that had had numerous episodes of unexplained blood in his urine. “It was at the point we were going to have to put him to sleep.”

“He was suffering,” Lenny interjects. “He was in pain. At that moment I thought he was just going to go. That

morning I had rushed him back to the hospital, and they actually called NC State to see if they could take him in. I rushed him to NC State the same day.”

“I got his bags packed fast,” Sylvia adds as Lenny contin ues, “Dr. Tanner Slead was the performing clinician.”

“This procedure saved his life,” Sylvia cuts in.

The procedure, called sclerotherapy, is a minimally invasive technique that required special equipment and a level of expertise in nephrology and urology that could be found in North Carolina only at the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine. The college is at the forefront of veterinary ne phrology and urology medicine in the United States as the AVMA American Board of Veterinary Specialties elevates the field to a specialty college. “Max’s condition is such a

Lenny and Sylvia Chin love traveling with their children Jaden and Ella and family dog Max.

10

‘They

rare one,” says Slead, the first fellow in nephrology and advanced urological procedures at the College of Veteri nary Medicine. “Not a lot of primary veterinarians have it on their list of differentials. To diagnose it, you have to endoscopically identify which ureter, and therefore which kidney, the blood is coming from, and unless you have that equipment, you cannot make a definitive diagnosis without open surgery.”

Max, born in November 2020, was a Christmas gift that year for the Chins’ teenage daughter. After Max was neu tered in June 2021, he began to have noticeable blood in his urine, and the family’s local veterinarian treated him for a urinary tract infection, the Chins say.

After Max’s second or third urinary tract infection, blood work showed his blood oxygen levels were abnormally low, and Max was referred to a local veterinary hospital, where he stayed a couple days and had a blood transfusion.

“They kind of gave us a very grim outlook” but no official diagnosis, Sylvia Chin says. When Max showed few symp toms over Christmas 2021, the Chins took him and their two children on a beach vacation.

“As soon as we got back, almost out of nowhere, he took a turn for the worse,” Lenny Chin recalls. “He was not him self. He could not urinate.”

The Chins took Max back to the local hospital. “He got discharged,” Lenny says. “They were thinking we’d just bring him home, see how he does. He was under so much medication, antibiotics, herbal medicine.”

Sylvia breaks in: “The plan was to get him stabilized, and ei ther he’ll get better miraculously or they were talking about removing his kidney.”

Wanting to do more for the sweet dog she calls her third and favorite child, Sylvia Chin started scouring the internet for options, typing in Max’s symptoms and seeing information about sclerotherapy, which uses a scope to chemically cau terize blood vessels. Their veterinarian told the Chins only NC State could perform the procedure.

When Max again ended up at his local hospital in January 2022 because of blood clots in his urethra, his owners plead ed to have him seen at NC State, and on Jan. 20 he was referred to the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine.

“His case was really severe,” Slead recalls. “He had already bled so much that he presented with severe anemia, required a transfusion and was found to have a large clot in his bladder, which can ultimately cause an obstruction and lead to kidney failure.”

Cystoscopy, which uses a special type of scope used to eval uate the urinary tract, showed that Max was suffering from idiopathic renal hematuria, which is characterized by severe bleeding from the kidneys with no identifiable cause.

To Slead, Max’s case perfectly illustrates how the recent elevation of the nephrology and urology field to a specialty college will just continue to improve medical knowledge and patient care.

“Having a new college like this means, when there is a di agnosis in question or a problem involving the urinary tract that general practitioners don’t have experience with, we’re a very obvious place to go and the obvious people to ask,” Slead says. “It cuts down a lot on the middlemen. You can go straight to people who have that expertise and can get a diagnosis, and therefore treatment, sooner.”

And for Max, that treatment saved his life.

“Before we could even do the procedure to cauterize the bleeding vessel, we had to dissolve the clot in his bladder,” Slead says. “He was hospitalized here, received a transfusion and had special medicine put into his bladder to dissolve his clot. We then used a combination of techniques to diagnose the main problem, which then required a high level of expe rience along with specialized equipment to actually perform the procedure to fix it. This is a classic case of why we need urologists and nephrologists.”

Max has an excellent prognosis at this point, Slead says. There’s no guarantee the problem won’t recur, but now everyone knows sclerotherapy will address it. Since recover ing from the surgery in January, Max has been a remarkably active and fun pup, the Chins say.

“He’s as healthy as you can get now,” Sylvia Chin says. “He runs around. He plays catch.”

Lenny Chin interjects, “He loves to go outside. He loves everyone. He loves other dogs.”

Sylvia Chin lets a beat of silence pass.

“He’s my buddy,” she says. “He’s Mama’s boy. He waits for me to eat breakfast. He waits for me to go to sleep. I love him.”

11

When classes began Aug. 8, students from South Carolina, Texas, Virginia, Puerto Rico, Rhode Island, Ohio, New Jersey, New Hampshire, Arizona, California, Florida and Guam joined North Carolina residents, including 25 from Wake County, as first years at the college.

The Class of 2026 includes graduates from 41 academic institutions, including NC State University. There are 42 NC State grads in the group.

12

13 Go Pack!!

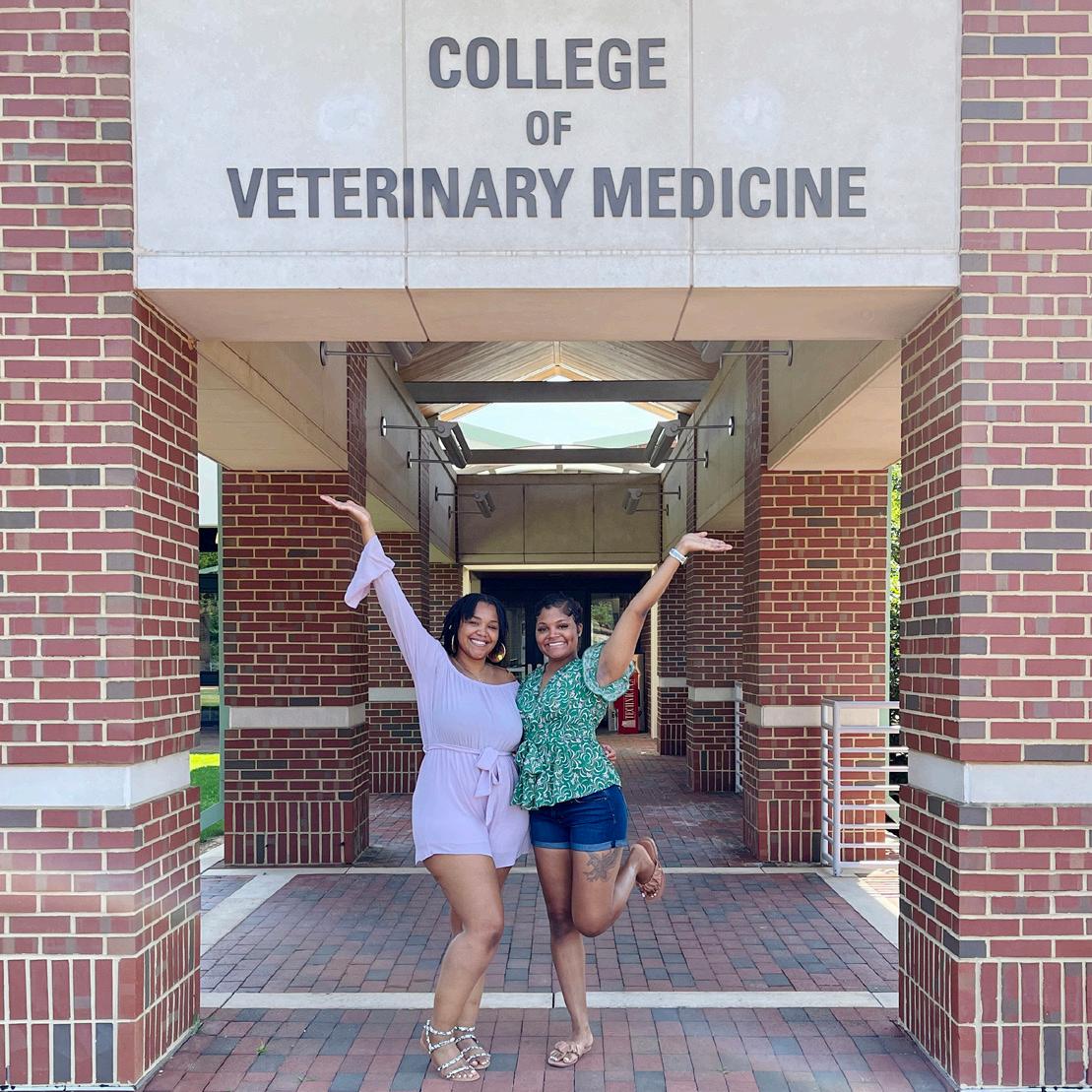

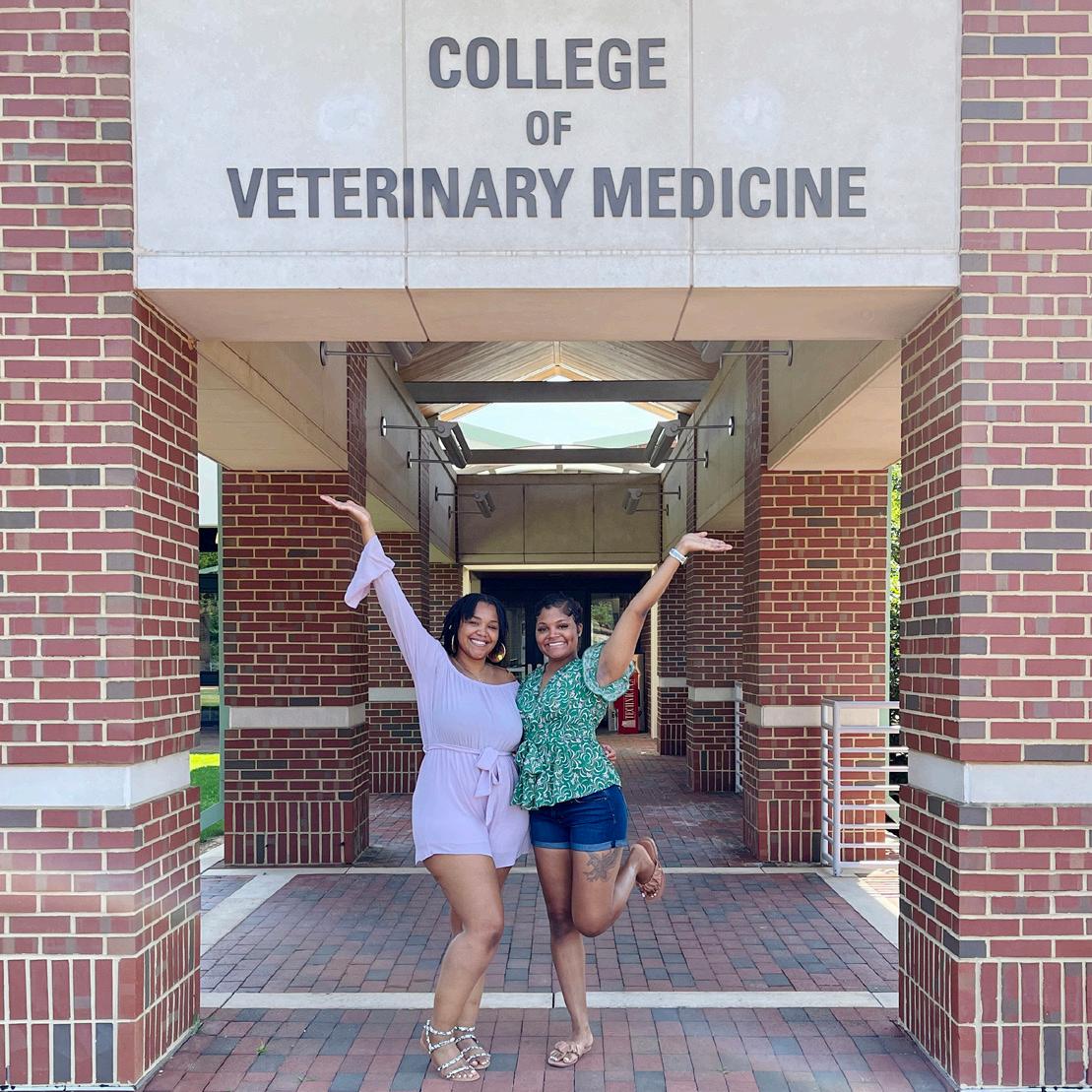

This fall, University of North Carolina at Pembroke grad uates Allyson Lane and Allyson Chavis started their studies at the College of Veterinary Medicine, joining Lexi High as successful participants in the University of North Caroli na System Veterinary Education Access or UNC-SVEA program.

The program, established in 2017, was designed to make degrees in veterinary medicine more accessible to minority students and students from a rural background.

High was the first beneficiary of the program to enter the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, and now Lane and Chavis have emerged from the rigorous admissions process to take their places at the CVM.

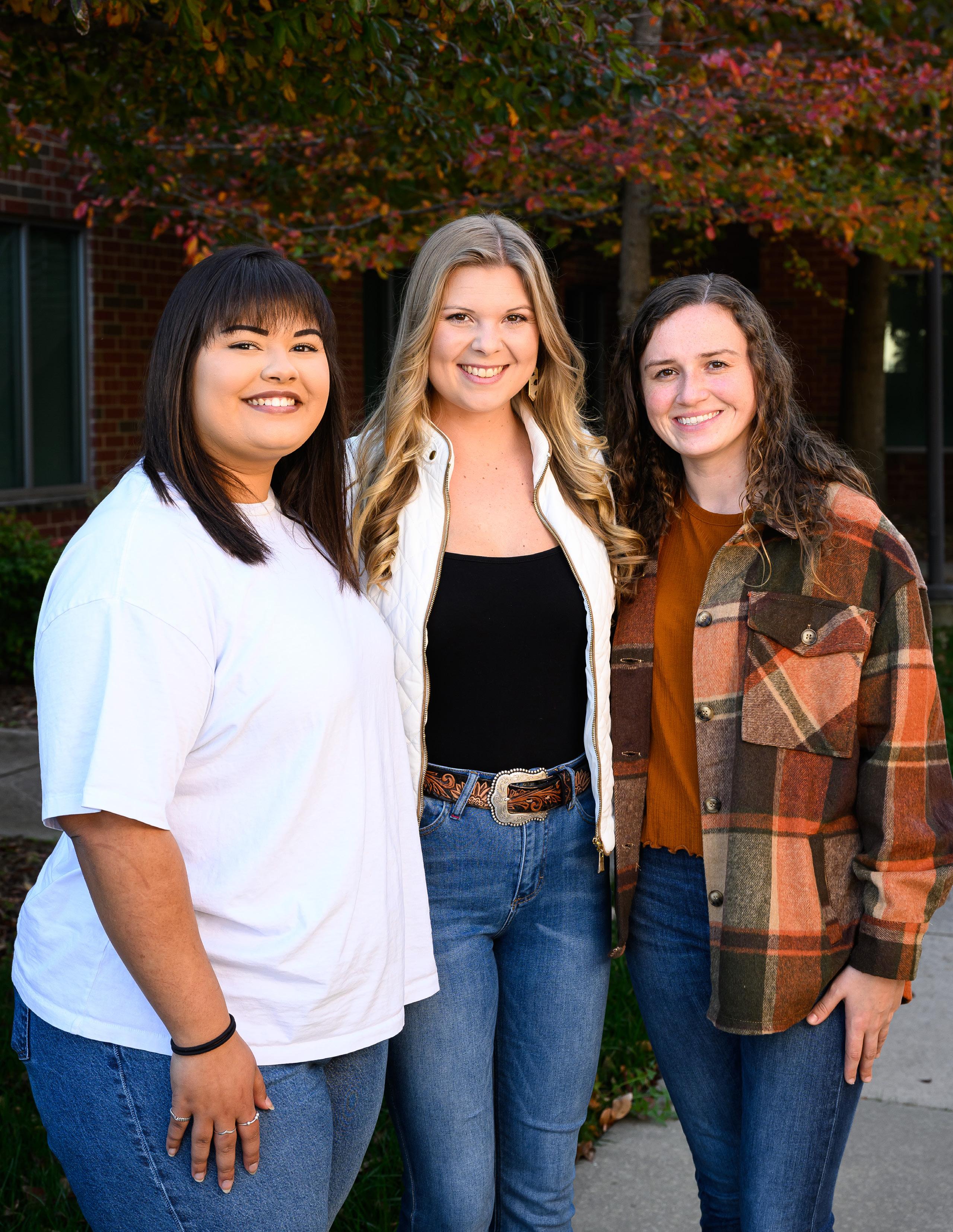

Interestingly, all three are well acquainted and are rooming together now. Of course, each has her own story, too.

Allyson Chavis is a member of the Lumbee Tribe and is the sole Native American member of the Class of 2026. She says she has dreamed of being a veterinarian since she was 8 years old. That’s when she and her great-grandmother res cued a bird with a broken wing and together nursed it back to health. It was a life-changing experience.

Chavis began volunteering at Baird’s Animal Hospital in Lumberton when she was 14 years old. “I did just general work at first, but by the time I was 16, I was working as a veterinary assistant,” she says. Her professional goals have never wavered. After high school it was on to Pembroke, where she soon learned about the Veterinary Education Access program.

Asked about her reaction to learning that she had been ac cepted at NC State, she says: “I can’t describe it. I couldn’t stop crying. It’s difficult for people in our area to get access to resources. It removed a lot of stress. Now I can focus on school.”

After graduation, Chavis plans to return to a small animal practice near her home. “I want to be near my family,” she says, “and I hope I can be an example to others.”

In the meantime, she gained experience working at the Cooley Veterinary Hospital in Rockingham.

Lane also wants to return close to home to be near family and hopes to enter a mixed animal practice, with an inter esting twist. “I’d like to focus on preventative medicine for farm animals, including vaccinations,” she says. “There’s a definite need for a mixed practice in rural areas.”

The Lane family has deep roots in the area. Her grandpar ents are in Rowland, just off I-95 near the South Carolina border. Her parents, too, are UNC-Pembroke alumni, and Lane plans to make the area home for another generation of her family.

Lexi High always had lofty goals. By the time she was in high school, she was barrel racing horses and intent on becoming a large animal veterinarian working with cows and horses.

Like Allyson Lane, High grew up in Laurel Hill, where car ing for animals on the family farm was a part of everyday life. “I’ve been working since I was big enough to carry a bucket,” she says.

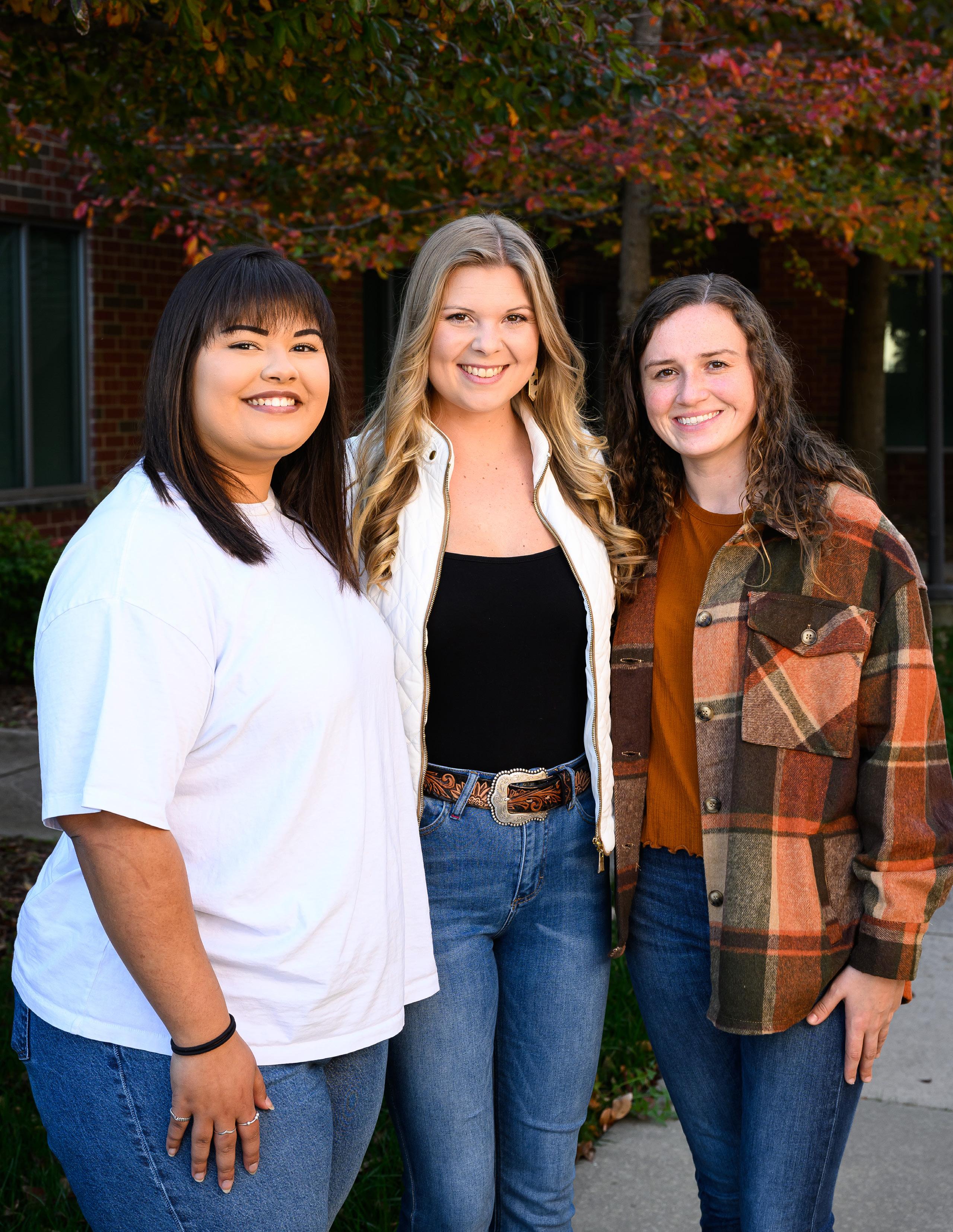

The first recipient of the program, High is a member of the Class of 2025.

All are grateful to those involved with the Veterinary Edu cation Access program for helping them turn their dreams into reality.

Allyson Lane grew up in Laurel Hill near Laurinburg in Scotland County. “I never thought of being anything other than a veterinarian,” she says.

A dedicated student, she graduated from Scotland County Early College in 2018, earning a high school diploma and an associate’s degree in science, the equivalent of a commu nity college degree. Although she considered several options to pursue her undergraduate degree, she stayed close to home at Pembroke, where she got her general biology degree in 2.5 years.

From left, Allyson Chavis, Lexi High and Allyson Lane all graduated from UNC-Pembroke.

15

“I can’t describe it. I couldn’t stop crying. It’s difficult for people in our area to get access to re sources. It removed a lot of stress. Now I can focus on school.”

- ALLYSON CHAVIS, Class of 2026, Lumbee Tribe member

-BY STEVE VOLSTAD

‘This is a Big Deal’

CVM wins USAID grant for interdisciplinary poultry project in Ethiopia

Bolstering its work in global health, the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine received its first USAID grant for a research project that could lead to healthier chickens and better nourished children in Ethiopia and to a model for how to address food insecurity elsewhere.

The interdisciplinary project, led by Andrew Stringer, former assistant professor of Veterinary Global and Public Health, embodies the growing movement known as One Health to recognize the connection among the health of people, animals and the environment.

“This is a big deal,” says Sid Thakur, director of the college’s Global Health Program. “Dr. Stringer has been working on food safety and security in Ethiopia for a long time, and this is a testament to his efforts. The beauty of this grant is that it’s focused on an interdisciplinary effort, where people from different backgrounds work on problems that need a concerted effort. One person can’t do everything, so I’m really, really excited about this USAID grant.”

USAID is a federal agency that works to advance U.S. national security and economic prosperity, demonstrate American generosity and promote paths to self-reliance and resilience.

In addition to Stringer, Seifu Hagos of Addis Ababa Univer sity and Alemayehu Amare from the Ethiopian Institute of Agricultural Research are co-principal investigators on the grant. Collaborators include Stephanie Martin, an assis tant professor of nutrition at the Gillings School of Global Public Health at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; Zachary Brown, associate professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at NC State; Jirata Shiferaw of Addis Ababa University College of Veterinary Medicine and Agriculture; and Sefinew Alemu of the Uni versity of Gondar.

The project, expected to last 18 months, has several com ponents but one driving principle: Improving the health of animals ultimately improves the health of humans.

Stringer and his colleagues hope to train female “chick en champions” to provide poultry-owning households in Ethiopia with access to a vaccine for a common virus known as Newcastle Disease Virus. The vaccine, which is administered in an eyedrop format that doesn’t have to be refrigerated, would lead to fewer poultry deaths and poten tially increased egg production. The team also will study how best to encourage rural families to feed the additional nutrition-packed eggs to their children under age 2 to tackle growth-stunting malnourishment.

The USAID office says malnutrition contributes to more than 50 percent of all infant and child deaths in Ethiopia.

“First, we need chickens to stop dying,” says Stringer, whose Ph.D. from the University of Liverpool focused on evalu ating how best to transfer animal health messages to rural farmers in Ethiopia. “And then we’ll move on to whether we can increase egg consumption. That’s why we have the partnership with the UNC Department of Nutrition and collaboration across institutions. Will the mothers do it? Will they feed the eggs to their children? What did they like and dislike? What’s the best way to do that?”

Stringer says he’ll use qualitative research approaches including focus groups and one-on-one interviews to explore how to reach the best outcomes.

Another hope is that the rural Ethiopian women who par ticipate as community vaccinators can establish sustainable businesses, creating revenue that can be invested into more vaccines for wider delivery and generating income for the chicken champions.

The project will work within the existing poultry system and will not include giving chickens or eggs to families.

“So if all they have is five chickens, then we will work with that flock,” Stringer says. “We need this intervention to be sustainable.”

The project will include a Social and Behavior Change Communication intervention package to promote egg con sumption in children under age 2.

16

17

The hope is that the rural Ethiopian women who participate as community vaccinators can establish sustainable businesses.

An Ethiopian in the Ada district of the Oromia region displays nutrition-packed eggs.

These interventions also will be delivered to rural Ethiopians by the chicken champions.

“An early project objective is understanding the cultural, economic, social and religious reasons that influence house hold egg consumption choices,” Stringer says. “Then we’ll know the best approach for designing a behavioral change package where we’re asking households to increase feeding children eggs.’”

The last 12 months of the project will be a cluster-random ized controlled trial. Some designated villages will receive both poultry health and the child nutrition interventions that explain the benefits of feeding eggs to children, some will receive only poultry interventions and control villages will receive nothing.

“Integrating a poultry health intervention program with a human nutrition intervention package can capitalize on these two issues, poultry mortality and child malnutrition, and provide benefits to both poultry and human health,” Stringer said in his application for the USAID grant. The project also could lead to strategic partnerships across academia and nongovernmental and governmental sectors and to private sector partners to support the scaling of any successful innovations.

“If it works, households will have improved existing flocks of poultry, vaccinated chickens, and chicken champions will have a business, they can charge a fee for providing a vac cination service and reinvest it in more vaccines,” Stringer says. “That’s why USAID is interested because we can

improve outcomes and create sustainable small businesses for these rural women and deliver that last-mile health to households. This project really is a testament to the One Health approach of tackling these challenges. Complex problems don’t have simple solutions.”

Under Thakur’s leadership, the NC State College of Veter inary Medicine combined its global health education and re search programs into one Global Health Program in 2018. In September, NC State University announced the launch of the universitywide Global One Health Academy, which will build upon the university’s strengths in agriculture and plant health, veterinary medicine and domestic animal health, and the health of biodiverse ecosystems and human societies. Thakur is the academy’s executive director.

“Global Health is a key program but a very young program, and two of our four years were affected by COVID,” Thak ur says. “For a young program to see some grants getting funded, to be one of only 18 collaborating centers with the World Health Organization on One Health and antimi crobial resistance, to have all of the pathogen surveillance programs we have and the visiting scholars even in the midst of COVID, CVM and NC State are already showing the world that we can make a difference.”

18

19

ONLINE NOW

In addition to writing news stories about fascinating people, research and events, we often let pictures and videos do our talking online. Here’s a look at some of the visual stories we’ve told in the past few months.

A CHILL CHECKUP. Many hands make light work of caring for Ronan, a 165-pound harbor seal from the North Carolina Zoo who came to the NC State Veterinary Hospital for tests.

TRIP OF A LIFETIME. Kayla Bonadie, a third-year NC State College of Veterinary Medicine student, was able to participate in a research trip and work among amazing wildlife in South Africa thanks to a seed grant awarded to help expand the involvement of minority students in global field research.

20

To watch these videos and more, scan here!

Be sure to follow us on social @NCStateVetMed

STUDENT SUMMER RESEARCH SERIES

. We asked three DVM students to explain how their summer research projects might change the world. See how Chris Ponticello, Stephanie Anderson and Ashley Cave are solving problems.

ONWARD AND UPWARD! In April, Kate Meurs started her tenure as the dean of the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, becoming the first woman to lead the college. She shared her vision.

21

The NC State College of Veterinary Medicine attracted its largest amount of research grants ever in 2021, putting the exclamation point on the more than 220 percent growth the college has experienced in grants since 2011.

The dramatic increase over the past 10 years, however, is just a footnote in the story of how NC State has made inten tional and innovative changes to expand its research impact. It also is an indication of how the power of cross-depart ment and university partnerships and the recognition of the translational nature of veterinary research have altered the scientific landscape.

“No one succeeds or fails alone,” says Dean Kate Meurs, a former associate dean for research at NC State. “Every fac ulty member we have is involved in research to some extent. That might be true of staff, too. They might be hypothe sizing, driving a research project. They might be collecting samples for collaborators or they might be studying the best way to teach a class or a new surgical technique or even how to word exam questions. All of those are aspects of research that drive veterinary medicine forward.”

At the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine, the years between 2011 when the grant total was $9.7 million and 2021 when it was $31.2 million have been ones of strate gic hiring, increased mentorship and an intensive focus on building on existing strengths at the college, Meurs says.

Anthony Blikslager, left, professor of equine surgery and gastro intestinal biology and head of the Department of Clinical Studies, confers with Mathew Gerard, professor of anatomy.

“The department heads and the faculty developed a team to mentor and support new faculty with grant work as they came in,” says Meurs, who became dean April 1 after serving three months as interim dean. “The college invested in long-term research support positions. We have a fulltime biostatistician now. And we are getting the very best graduate students and post-doctoral fellows to assist with our research, which strengthens the team as well.”

The research ascent began when former Dean Paul Lunn, appointed in 2012, inherited a group of faculty positions because of enrollment increases, says Barbara Sherry, a virology professor who leads the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences at the College of Veterinary Medicine. Lunn left the college in January.

“Rather than saying to department heads, ‘You get five, and you get five,’ he said, ‘All right, faculty, why don’t you pitch what you need based on group strength? Think about what kind of people you need to make your area even stronger,’ ” Sherry recalls Lunn saying. “And that’s exactly what we did.”

Lots of pitches were followed by many searches – not searches for one faculty member but searches for a group of faculty who would not only complement each other, but complement the existing teams, she says.

At the same time, the university had launched the Chancel lor’s Faculty Excellence Program that championed the idea

23

Jorge Piedrahita, left, Randall B. Terry Jr. Distinguished Professor of Translational Medicine at the CVM and director of the Comparative Medicine Institute, leads the Translational Regenerative Medicine cluster.

of “cluster hires.” The university added 75 faculty members across 20 select fields, bringing NC State University to the forefront of interdisciplinary education.

For example, the Translational Regenerative Medicine cluster includes faculty from the Comparative Medicine Institute, the College of Engineering, the College of Textiles and the College of Veterinary Medicine working together to advance the health and well-being of animals and humans.

Jorge Piedrahita, Randall B. Terry Jr. Distinguished Profes sor of Translational Medicine at the CVM and director of the CMI, leads the cluster.

“This is a huge part of where success lies,” Sherry says. “Gone are the days where you could just approach a prob lem, just me, to solve this problem. Problems are too dirty, too complex, too gritty. You need a lot of angles, and no one person is skilled in all of those things. Bring in someone who approaches things in entirely different ways and put them in a group that doesn’t have that skill, and it can be incredibly disruptive, in a good way.”

Partnering with other universities

In addition to more collaboration among departments inside NC State, there are more research partnerships among the Triangle’s universities. UNC-CH and NC State share a Joint Department of Biomedical Engineering, for example.

Sometimes the universities pull together to seek grants as well. That was the case with the largest award to the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine for 2021 – a $6.3 mil lion grant from the National Institutes of Health to build a swine biomedical research facility for gnotobiotic, transgenic and translational medicine. NC State College of Veterinary

the grant because, unlike Duke and UNC, it is equipped to house and handle pigs, but all three schools were involved in the grant application, Meur says.

To Anthony Blikslager, professor of equine surgery and gas trointestinal biology and head of the Department of Clini cal Studies, this NIH grant shows how NC State is uniquely situated to continue its upward research trajectory as more funding entities invest in research into diseases of larger animals that has translational applications for human health. The NIH supports only research with human applications.

“Duke, UNC and NC Central are collaborating with us be cause we have the facilities and we care for larger animals,” Blikslager says. “We have anesthetists who know how to anesthetize large animals. They don’t. We have the hospital technicians. They say, why reproduce what they’re trying to do at the vet college? And we’re purposefully positioning ourselves that way.”

The upshot is that, because of its access to animals and its expertise, NC State is equipped to take research through more stages.

“So few entities can connect it all, to take the science through the initial cellular research, through large animal studies and then on to clinical trials,” Blikslager says. “In the medical community, all of that would be segregated. In a vet school, we can get people to do all three of those and con nect it. A lot of research done in smaller animals like mice hasn’t translated to human use. It kind of missed something. Now it’s recognized that studying diseases that affect pets and larger farm animals can provide better insight into human health.”

As the research landscape evolves, the NC State College of

24

Barbara Sherry, CENTER, a virology professor, leads the Department of Molecular Biomedical Sciences

well-positioned to take advantage of the changes also be cause of the foundational changes Meurs has made, Sherry says.

“She created workgroups, small informal discussion groups, for junior investigators and for people writing these kinds of grants,” she says. “There’s nothing like talking things out with your peers. You get good ideas, emotional support, critiques. And it’s not someone lecturing at you. It’s a bunch of people discussing things. It’s been very successful.”

Meurs also enlisted Ken Adler, one of the world’s foremost researchers in airway disease and a recipient of numerous grants from the National Institutes of Health, to help other NC State faculty members with grant proposals.

“We’ve taken advantage of the system put in place with Ken Adler to work on this,” Blikslager says. “In the past, he would do that unofficially, mostly help with the first page, but more recently he’s helped with the entire grant. This is a concrete example of something we’ve put into place.”

Gathering the grant-whisperers

Meurs also gathered a group of people Sherry calls grant-whisperers to mentor colleagues and created a re search fund within the College of Veterinary Medicine that she could use to help promising proposals stay on track.

“Dr. Meurs tied some of that seed funding to your accessing her bank of mentors and grant- whisperers,” Sherry says. “If you write a grant proposal and it doesn’t get funded the first try, and they ask for some more data, now you need money to do that work. And she’ll give you some money, but only if you worked with a grant-whisperer the first time. If you were already doing all you could to be successful, then she’ll add her money on top.”

For Meurs, one measure of how well NC State’s new research structure is doing is the nearly even distribution of the research dollars among the Department of Clinical Sci ences, the Department of Molecular Biological Sciences and the Department of Population Health and Pathobiology.

“The growth in funding is spread among the three depart ments, and I love that,” Meurs says. “It’s really nice to have that balance.”

The most important thing

Rather than talk about the largest grants from 2021, the dean and department heads emphasized that totals fluctuate year to year and that all research, no matter its funding level, is critical to increasing our scientific understanding.

“Really, the most important thing is, what is the impact of those research dollars?” Meurs says. “What is the new inno vative research performed and what will be discovered?”

At NC State, Blikslager says, research is valued in whatever way someone contributes.

“Some people research how to teach better, and it scales up from there,” he says. “When people get in at a small level, they get bold about bigger things. It has an exponential effect. When some people are successful, others will see it happening and think, ‘Maybe I could do that, too.’ ”

The story of research grants awarded to NC State College of Veterinary Medicine over the past 10 years is clearly a success story, Sherry says, but not because of the amount.

“It’s always about a trajectory,” she says. “We’ve had huge growth, and we anticipate continued growth, and we anticipate having even greater impacts on animal and human health. It’s very much a story of our faculty, not just a few faculty but a majority of our faculty, contributing to this. And it involves the students we’re teaching, our house officers, our graduates, our staff and our post-docs. It’s team science.”

-BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER

“Gone are the days where you could just approach a problem, just me, to solve this problem. Problems are too dirty, too complex, too gritty. You need a lot of angles, and no one person is skilled in all of those things.”

BARBARA SHERRY, Department Head and Professor

25

26

WHEN RARE ISN’T A STRONG ENOUGH WORD

A fortuitous combination of an NC State veterinary resident’s relentlessness and a UNC physician’s skill saves an Apex family’s dog

BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER

BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER

When Dr. Todd Baron, a professor of medicine and gastroenterologist at UNC Hospital-Chapel Hill, arrived at the NC State Veterinary Hospital to treat an ailing cockapoo puppy, he was about to perform a life-saving procedure no one likely had ever used on a dog before.

And the puppy, named Winston, had a rare pancreatic condition that no one at NC State could recall seeing before.

Winston, as owner Bill Kivett says today, is alive to see his first birthday in Janu ary only because the medical sun and the moon and all of the planets perfectly aligned.

The sun in this case is NC State veterinary resident Dr. Katie Anderson, the moon “human” doctor Baron and the planets a host of moving parts including a piece of medical equipment so rare and expensive that it had to be rented from the manufacturer.

In April, Kivett and wife Stacy had brought Winston, born in January in Winston-Salem, home to their two sons in Apex. Within a few weeks, the pup started having episodes of vomiting and lethargy that resulted in multiple visits to local veterinary emergency hospitals.

“He literally wouldn’t move from one spot,” Stacy Kivett recalls. “That’s what triggered us to take him in. He wasn’t moving, and when we did pick him up, he was wincing in pain. He was a little bitty thing, maybe 6 or 8 pounds.”

Katie Anderson, third-year internal medicine resident, and Bill Kivett, Winston’s owner

27

About every two weeks, the pup would have another episode, always after hours on a Saturday, the Kivetts joke. Winston, who loves to take rides in the car, would perk up after receiving intravenous fluids at whatever local emergen cy hospital could see him, and the Kivetts would be advised to follow up with their primary care veterinarian.

Of course, Winston always seemed fine during the followup appointments, the Kivetts say, but their veterinarian did suggest that Winston might be suffering from pancreatitis, which would be uncommon in a puppy.

was a strange history’

On a Saturday in June, Winston had a particularly bad episode, and the Kivetts took him to a local veterinary emer gency hospital, which referred him to the NC State Veteri nary Hospital at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

The on-call resident in internal medicine that weekend was Anderson, who took the dog’s history from the Kivetts.

“It was a strange history,” says Anderson, a DVM graduate of the University of Minnesota in her third year of residen cy at NC State. “We did a diagnostic workup for gastroin testinal disease trying to figure out what was going on. We evaluated bloodwork and an abdominal ultrasound. We determined he was having recurring episodes of pancreati tis, and this was surprising and unexpected. You just don’t see that in a dog this young.”

Anderson says she stayed awake for hours that night reading through the medical literature on juvenile pancreatitis in

humans because there simply was no literature on the condition in puppies. Pancreatitis, or inflammation of the pancreas, is usually a disease of the middle-aged and elderly, even in dogs.

“The thing I kept running across was this congenital abnor mality,” she says. “The pancreas has a little duct that leads down to the intestine, and at the entrance to the intestine is a sphincter that’s usually closed. When the pancreas releases enzymes, the sphincter is supposed to open and allow them to empty into the intestine.”

When the sphincter doesn’t open properly, the fluid backs up into the pancreas and can cause recurrent pancreatitis, she says. It can also cause the duct to become dilated, and An derson was able to see a dilation in Winston’s duct because of NC State’s state-of-the-art equipment.

“This is how we ended up diagnosing him with this disease,” she says. “It’s called Wirsungocele if the major duodenal papilla is affected or Santorinicele if the minor duodenal papilla is affected in people.”

Canine anatomy is slightly different, but Winston naturally had the less common abnormality.

“The message we got initially was that Dr. Anderson had literally never seen anything like this before. Ever,” Stacy Kivett says. “She had never seen it. She consulted with many, many doctors, radiology, and they had never seen it. Ever. We were, like, of course you haven’t.”

28

‘It

Dr. Katie Anderson, left, gives Winston a checkup in October after his surgery in July, right.

Diagnosis in hand, the next obstacle was figuring out how to treat it.

The protocol in humans requires using a special endoscope, made by Olympus, that has a side-facing rather than for ward-facing camera to better see the tiny pancreatic ducts, says Dr. Jody Gookin, a professor of internal medicine at NC State. Only two pediatric-sized Olympus scopes exist, Baron says.

“These endoscopes are designed to be able to find these ducts and actually catheterize these sphincters in people,” says Gookin, Fluoroscience Distinguished Professor of Veterinary Research Education. “The use of these scopes enables us to do what’s called a sphincterotomy to open the obstructed duct to cure these patients. It’s something we just don’t have in veterinary medicine.”

He wrote the book

Because Gookin is part of the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease, a collaborative GI research center at UNC-Chapel Hill and NC State University, she sought advice from a colleague there. The center is funded by the National Institutes of Health and focuses on the microbi ome, clinical and translational research, and regenerative medicine and repair.

“The center provides a unique resource for clinical and

research collaboration between veterinary and human gastroenterologists that goes both ways,” Gookin says. “I reached out to a colleague at the UNC-Chapel Hill human hospital and asked if he knew anyone with any expertise in using this scope. The procedure is called ERCP or endo scopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography.”

It just so happens that her colleague knew Baron, director of Advanced Therapeutic Endoscopy at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Baron, who has been doing complex endoscopy since 1993, wrote the book on ERCP. It’s in its fourth edition.

“They gave us Dr. Baron’s contact info, and we had a con ference call that same afternoon,” Anderson says. “We said, ‘Do you think this is a possibility?’ And he said, ‘Yes, abso lutely, that’s what’s going on with this dog.’ We talked about surgical options, and he just offered to come and bring the equipment and do the procedure for us. He was incredibly generous, incredibly kind.”

The Kivetts were stunned by the offer.

“We were jokingly saying we’d have to wheel him into Rex Hospital or UNC with a tail coming out of his gown,” Stacy Kivett says. “But Dr. Baron came to NC State!”

a professor of medicine and gastroenterol ogist at UNC HospitalChapel Hill, performs endoscopic retrograde cholan-giopan creatography on Winston.

29

Dr. Todd Baron,

On a Wednesday in July, Baron arrived at NC State with an adult-sized endoscope in hand. Used to maneuvering the scope through 200-pound humans, Baron says it was surreal when he walked into the procedure room and actually looked down at tiny Winston.

“It was a little bit of bewilderment, and it wasn’t lost on me that this dog was important to somebody,” he says. “I didn’t look at it as just an animal. You put yourself in the place of the owner, and it’s their family member. I thought about it the same way I do when I do this procedure on a person. It’s not an inanimate object. They have feelings and family members. What I do doesn’t affect only the person but all of the people who depend on and love that person.”

Once he had guided the special endoscope with the side camera into place through Winston’s esophagus, Baron discovered that the adult-sized instrument was too large, obstructing his view.

“We switched back to a standard scope that doesn’t have the same capabilities,” he says, “but through ingenuity we were able to complete the procedure and open the duct with a cutting instrument so it would drain better.”

The “we” was Baron and the staff at the NC State Veteri nary Hospital. Baron was the only “human” clinician there, although a representative from the scope manufacturer also attended to witness the never-before-seen use on a dog.

‘A real team effort’

Gookin says the veterinary college had several conversations and planning sessions with Baron before the procedure was scheduled and also coordinated with Winston’s owners.

“We got the dog here, we put the dog under anesthesia, then it was all done under fluoroscopy where we can see where the scope is and anatomy in real time,” says Gookin, who particularly praised the work of Patty Secoura, an experi enced internal medicine veterinary technician. “Dr. Baron was able to put contrast media in one of the pancreatic ducts to highlight what was going on, identify the site of the obstruction and use the scope to perform a sphincterotomy. The patient has recovered extremely well.”

The veterinary medical facilities were top-notch, and the high-level imaging equipment was vital to completing the procedure successfully, Baron says.

“It wasn’t just me looking on the inside,” he says. “We need ed the imaging equipment to be high resolution because we injected the pancreas duct with contrast to find the open ings. It was a real team effort.”

And the team, Baron and Anderson are quick to point out includes the Kivetts.

“They were probably the best owners to be involved with this case,” Anderson says. “It’s hard when doctors tell you we’ve never seen this condition before, we think this is what’s going on, but we don’t know for sure. We’re going to do this uncommon procedure that may or may not fix your dog. They were amazing and very open to trying anything that worked.”

For the Kivetts, both of whom graduated from NC State University in 2000, the fact that Winston has had no more painful episodes since the procedure in July is everything.

“Dr. Anderson and her team went above and beyond anything either one of us could have ever imagined to really figure out what was going on with Winston,” Bill Kivett says. “It wasn’t a check the box exercise. I don’t think we can express our gratitude enough to everybody who has helped out, everything that’s happened from the first time we took him to NC State until today.”

The most astonishing thing to Baron was all of the pieces coming together. He found Bill Kivett’s sun and moon and planets analogy apt.

“The biggest things are the collaboration around the two universities, the willingness of everyone to really pitch in,” Baron says. “It was very exciting obviously because we were doing something very novel, something other institutions in the country really couldn’t provide. And we had the good fortune to have everything work out.”

Against all odds, Winston today is taking the car rides he loves and playing hide and go seek the ball with the Kivett boys. And, the next time the family takes a beach trip, Stacy Kivett says her pup will be sitting on the balcony, face to the wind, ears just flapping away.

30

“I don’t think we can express our gratitude enough to everybody who has helped out, everything that’s happened from the first time we took him to NC State until today.”

BILL KIVETT, Winston’s owner

31

Top, William and Michael Kivett like to play hide the ball with their dog Winston. / Far left, Winston gets a checkup at the NC State Veterinary Hospital in October.

NC State Veterinary Medicine

NC

Veterinary Medical Foundation

1060 William Moore Drive • Raleigh, NC 27607

Give Now: Use the giving envelope enclosed, (checks payable to “NCVMF”), or give online at cvm.ncsu.edu/giving.

Contact Us: Giving Office: 919-513-6660 cvmfoundation@ncsu.edu

The Oath is published by the NC State Veterinary Medicine Communications and Marketing office. Contact us at CVMCommunications@ncsu.edu

This magazine was printed for a total cost of $4,500, or $1.33 per copy. No state funds were used.

Make an Impact

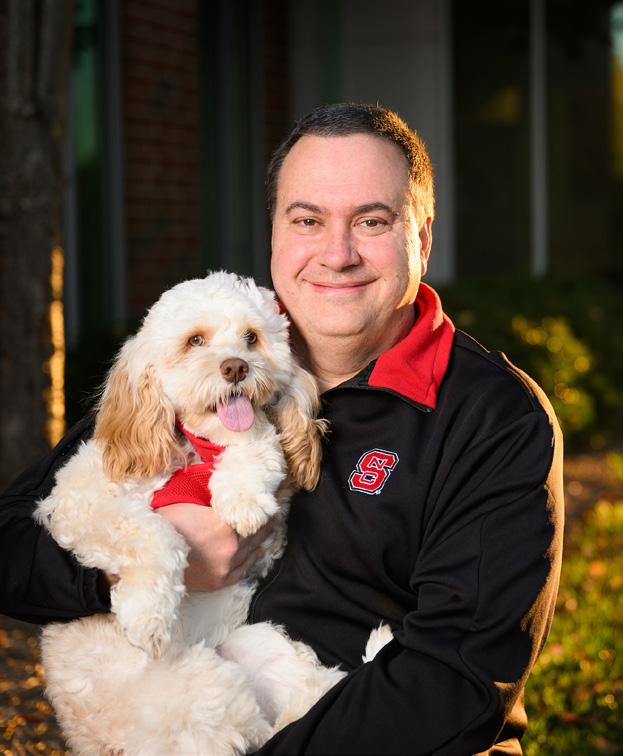

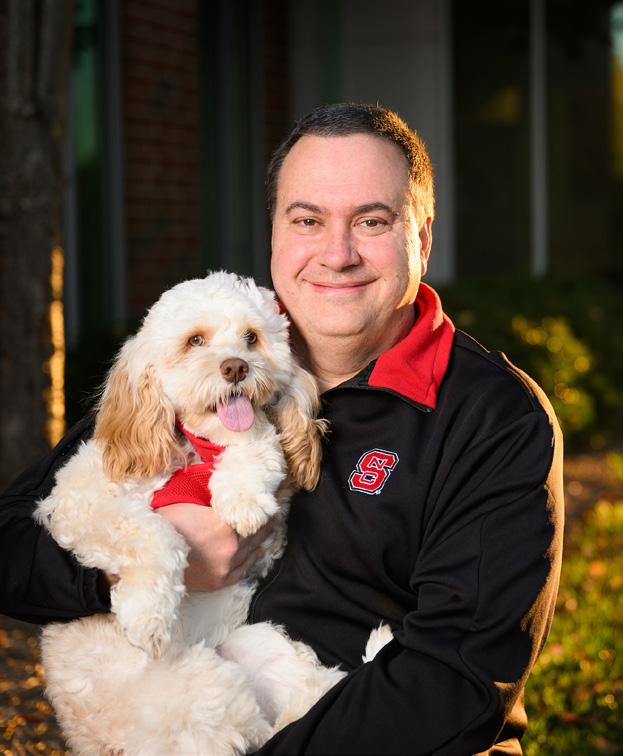

Your support helps shape the future of veterinary medicine and changes lives.Generous donors like Dr. Jackie Jaloszynski and Sid Bragg help us advance our work in education and discovery.

“Being donors to the NC State College of Veterinary Medicine is an honor for us because it allows us to make a difference. In helping to support the students, residents, professors and researchers, we are able, through them, to make a lifetime of differences in so many fur babies’ lives and their parents who love them.”

-Jackie, Sid & Hudson

Help make an impact: https://cvm.ncsu.edu/giving/

BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER

BY BURGETTA EPLIN WHEELER