Accountants: Kelly Wike, Ashley Hillerson

Business Operations Manager: Brian Hosek

Technical Operations Lead: Alan Reile

Data Scientist: Shane Wegner

Licensing Manager: Randy Meissner

Assistants: Amanda Anstrom, Tracy Price, Tana Bentz, Tanya Mikkelsen, Elizabeth Klein

Administrative Assistant – Dickinson: Stephanie Richardson

Administrative Assistant – Devils Lake: Lisa Tofte

Administrative Assistant – Jamestown: Tonya Kukowski

Administrative Assistant – Riverdale: Mattea Bierman

Administrative Assistant – Williston: Stephanie Wellman

CONSERVATION AND COMMUNICATIONS DIVISION

Division Chief: Greg Link, Bismarck

Communications Supervisor: Greg Freeman, Bismarck

Editor: North Dakota OUTDOORS: Ron Wilson, Bismarck

R3 Coordinator: Cayla Bendel, Bismarck

Digital Media Editor: Lara Anderson, Bismarck

Video Project Supervisor: Mike Anderson, Bismarck

Photographer/Videographer: Ashley Peterson, Bismarck

Marketing Specialist: Jackie Ressler, Bismarck

Information Specialist: Dawn Jochim, Bismarck

Graphic Artist: Kristi Fast, Bismarck

Education Supervisor: Marty Egeland, Bismarck

Education Coordinator: Jeff Long, Bismarck

Hunter Education Coordinator: Brian Schaffer, Bismarck

Outreach Biologists: Doug Leier, West Fargo; Greg Gullickson, Minot; Jim Job, Grand Forks

Conservation Supervisor: Bruce Kreft, Bismarck

Resource Biologists: John Schumacher, Aaron Larsen, Bismarck

Conservation Biologists: Sandra Johnson, Patrick Isakson, Elisha Mueller, Bismarck

Administrative Assistant: Amber Schroeter, Bismarck

ENFORCEMENT DIVISION

Division Chief: Scott Winkelman, Bismarck

Investigative Supervisor: Jim Burud, Kenmare

Investigator: Blake Riewer, Grand Forks

Operations Supervisor: Jackie Lundstrom, Bismarck

Region No. 1 Warden Supvr: Mark Pollert, Jamestown

District Wardens: Corey Erck, Bismarck; Michael Sedlacek, Fargo; Andrew Dahlgren, Milnor; Erik Schmidt, Linton; Greg Hastings, Jamestown; Noah Raitz, LaMoure

Region No. 2 Warden Supvr: Paul Freeman, Devils Lake

District Wardens: Jonathan Tofteland, Bottineau; Jonathan Peterson, Devils Lake; James Myhre, New Rockford; Alan Howard, Cando; Drew Johnson, Finley; Sam Feldmann, Rugby; Gage Muench, Grand Forks

Region No. 3 Warden Supvr: Joe Lucas, Riverdale

District Wardens: Ken Skuza, Riverdale; Michael Raasakka, Stanley; Connor Folkers, Watford City; Shawn Sperling, Minot; Keenan Snyder, Williston, Josh Hedstrom, Tioga; Riley Gerding, Kenmare; Clayton Edstrom, Turtle Lake

Region No. 4 Warden Supvr: Dan Hoenke, Dickinson

District Wardens: Kylor Johnston, Hazen; Zachary Biberdorf, Bowman; Courtney Sprenger, Elgin; Zane Manhart, Golva; Jerad Bluem, Mandan; Zachary Schuchard, Richardton

Administrative Assistant: Lori Kensington, Bismarck

WILDLIFE DIVISION

Division Chief: Casey Anderson, Bismarck

Assistant Division Chief: Bill Haase, Bismarck

Game Mgt. Section Leader: Stephanie Tucker, Bismarck

Pilot: Jeff Faught, Bismarck

Upland Game Mgt. Supvr: Jesse Kolar, Dickinson

Upland Game Mgt. Biologist: Rodney Gross, Bismarck

Migratory Game Bird Mgt. Supvr: Mike Szymanski, Bismarck

Migratory Game Bird Biologist: Jacob Hewitt

Big Game Mgt. Supvr: Bruce Stillings, Dickinson

Big Game Mgt. Biologists: Brett Wiedmann, Dickinson; Jason Smith, Jamestown; Ben Matykiewicz, Bismarck

Survey Coordinator: Chad Parent, Bismarck

Wildlife Veterinarian: Dr. Charlie Bahnson, Bismarck

Wildlife Health Biologist: Mason Ryckman, Bismarck

Game Management Biological Technician: Ryan Herigstad, Bismarck

Wildlife Resource Management Section Leader: Kent Luttschwager, Williston

Wildlife Resource Mgt. Supvrs: Brian Prince, Devils Lake; Brian Kietzman, Jamestown; Dan Halstead, Riverdale; Blake Schaan, Lonetree; Levi Jacobson, Bismarck

Wildlife Resource Mgt. Biologists: Randy Littlefield, Lonetree; Rodd Compson, Jamestown; Judd Jasmer, Dickinson; Todd Buckley, Williston; Jake Oster, Riverdale

Wildlife Biological Technicians: Tom Crutchfield, Jim Houston, Bismarck; Dan Morman, Robert Miller, Riverdale; Jason Rowell, Jamestown; Scott Olson, Devils Lake; Zach Eustice, Williston; Colton Soiseth, Lonetree

Private Land Section Leader: Kevin Kading, Bismarck

Habitat Manager: Nathan Harling, Bismarck

Private Land Field Operation Supvrs: Curtis Francis, East Region, Andrew Dinges, West Region, Bismarck

Private Land Biologists: Colin Penner, Jens Johnson, Bismarck; Jaden Honeyman, Ryan Huber, Riverdale; Renae Schultz, Jeff Williams, Jamestown; Terry Oswald, Jr., Lonetree; Andrew Ahrens, Devils Lake; Erica Sevigny, Williston; Brandon Ramsey, Dickinson; Matthew Parvey, Devils Lake

Procurement Officer: Dale Repnow, Bismarck

Administrative Assistant: Alegra Powers, Bismarck

Lonetree Administrative Assistant: Diana Raugust, Harvey

FISHERIES DIVISION

Division Chief: Greg Power, Bismarck

Fisheries Mgt. Section Leader: Scott Gangl, Bismarck

Fisheries Supvrs: Russ Kinzler, Dave Fryda, Riverdale; Paul Bailey, Bismarck; Brandon Kratz, Jamestown; Aaron Slominski, Williston; Bryan Sea, Devils Lake

Fisheries Biologists: Todd Caspers, Devils Lake; Mike Johnson, Jamestown; Jeff Merchant, Dickinson; Zach Kjos, Riverdale

Fisheries Biological Technicians: Phil Miller, Devils Lake; Justen Barstad, Bismarck; Brian Frohlich, Riverdale; Lucas Rott, Jamestown; Ethan Krebs, Williston

Production/Development Section Supvr: Jerry Weigel, Bismarck

Aquatic Nuisance Species Coordinator: Benjamin Holen, Jamestown

Aquatic Nuisance Species Biologists: Mason Hammer, Kyle Oxley, Jamestown

Fisheries Development Supvr: Bob Frohlich, Bismarck

Fisheries Dev. Proj. Mgr: Wesley Erdle, Bismarck

Fisheries Development Specialist: Kyle Hoge, Jacob Heyer, Joe Fladeland, Bismarck

Administrative Assistant: Janice Vetter, Bismarck

ADVISORY BOARD

District 1 Beau Wisness, Keene

District 2 Travis Leier, Velva

District 3 Edward Dosch, Devils Lake

District 4 Karissa Daws, Michigan

District 5 Doug Madsen, Harwood

District 6 Cody Sand, Ashley

District 7 Jody Sommer, Mandan

District 8 Rob Brooks, Rhame

A common sight this spring on the Missouri River as anglers jockey for position to get in on the walleye bite.

Periodical Postage Paid at Bismarck, ND 58501 and additional entry offices. Printed in the United States POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: North Dakota OUTDOORS 100 North Bismarck Expressway Bismarck, ND 58501-5095 Report All Poachers (RAP) 701-328-9921 In cooperation with North Dakota Wildlife Federation and North Dakota State Radio. Official publication of the North Dakota Game and Fish Department (ISSN 0029-2761) 100 N. Bismarck Expressway, Bismarck, ND 58501-5095 Website: gf.nd.gov • Email: ndgf@nd.gov • Information 701-328-6300 • Licensing 701-328-6335 • Administration 701-328-6305 • North Dakota Outdoors Subscriptions 701-328-6363 • Hunter Education 701-328-6615 • The TTY/TTD (Relay ND) number for the hearing or speech impaired is 800-366-6888 Contributing photographers for this issue: Mike Anderson, Jesse

Sandra

Colin

and Ashley Peterson. DEPARTMENT DIRECTORY Governor Doug Burgum ADMINISTRATIVE DIVISION Game and Fish Director: Jeb Williams Deputy Director: Scott Peterson Chief, Administrative Services: Kim Kary Federal Aid Manager: Corey Wentland Administrative Staff Officer: Justin Mattson Administrative Assistant: Lynn Timm Building Maint. Supervisor: Brandon Diehl Administrative Officer: Melissa Long, Alan Peterson Accounting Manager: Angie

Kolar,

Johnson,

Penner

Morrison

The mission of the North Dakota Game and Fish Department is to protect, conserve and enhance fish and wildlife populations and their habitats for sustained public consumptive and nonconsumptive use.

■ Editor: Ron Wilson

Graphic Designer: Kristi Fast ■ Circulation Manager: Dawn Jochim

North Dakota OUTDOORS is published 10 times a year, monthly except for the months of April and September. Subscription rates are $10 for one year or $20 for three years. Group rates of $7 a year are available to organizations presenting 25 or more subscriptions. Remittance should be by check or money order payable to the North Dakota Game and Fish Department. Indicate if subscription is new or renewal. The numbers on the upper right corner of the mailing label indicate the date of the last issue a subscriber will receive unless the subscription is renewed.

Permission to reprint materials appearing in North Dakota OUTDOORS must be obtained from the author, artist or photographer. We encourage contributions; contact the editor for writer and photography guidelines prior to submission.

The NDGFD receives Federal financial assistance from the US Fish and Wildlife Service and the US Coast Guard. In accordance with Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, Title II of the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, the NDGFD joins the US Department of the Interior and its Bureaus and the US Department of Homeland Security in prohibiting discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, sex (in education programs or activities) and also religion. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or you desire further information, please write to: ND Game and Fish Department, Attn: Chief of Administrative Services, 100 N. Bismarck Expressway, Bismarck, ND 58501-5095 or to: Office of Civil Rights, Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, NW, Washington, DC 20240.

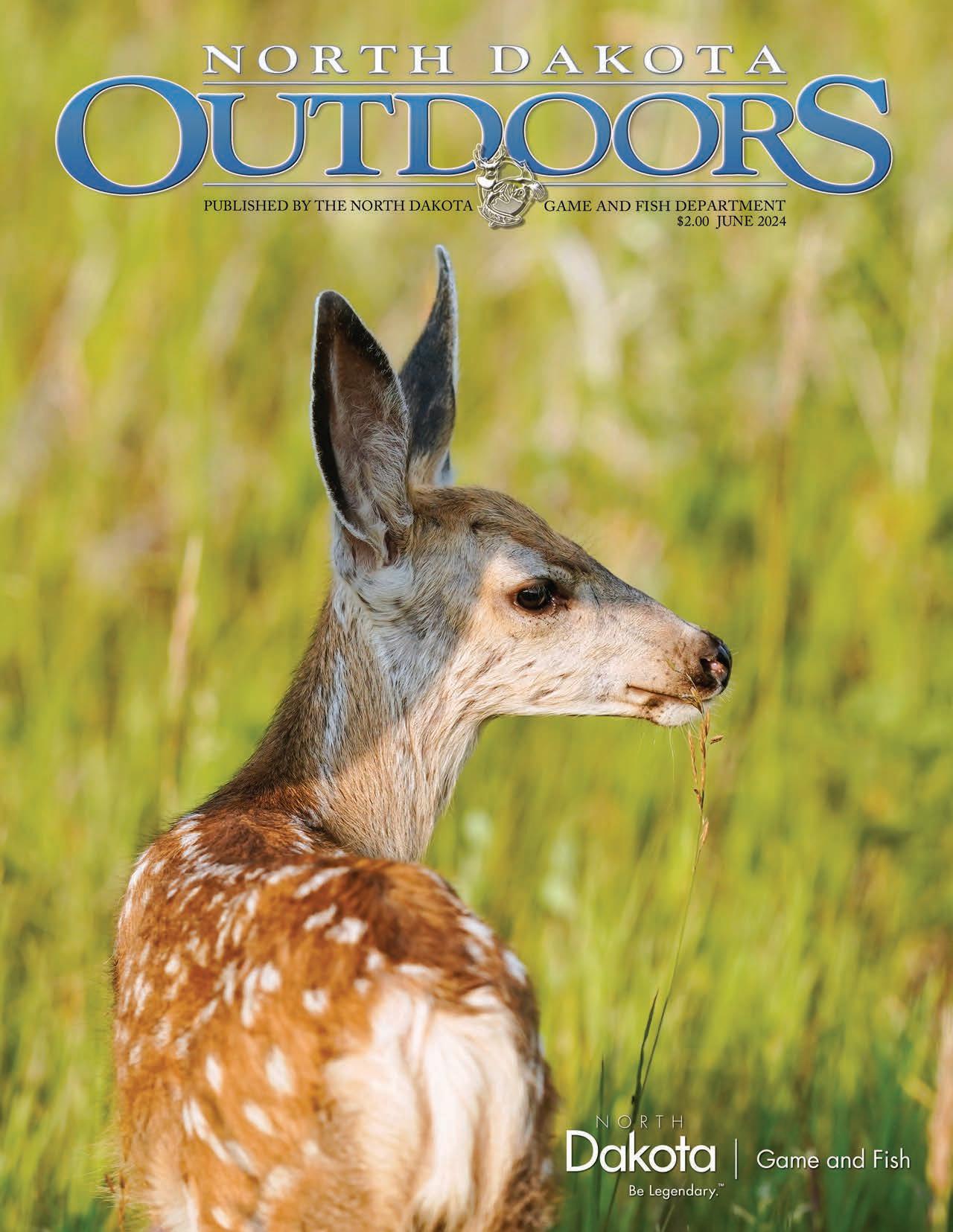

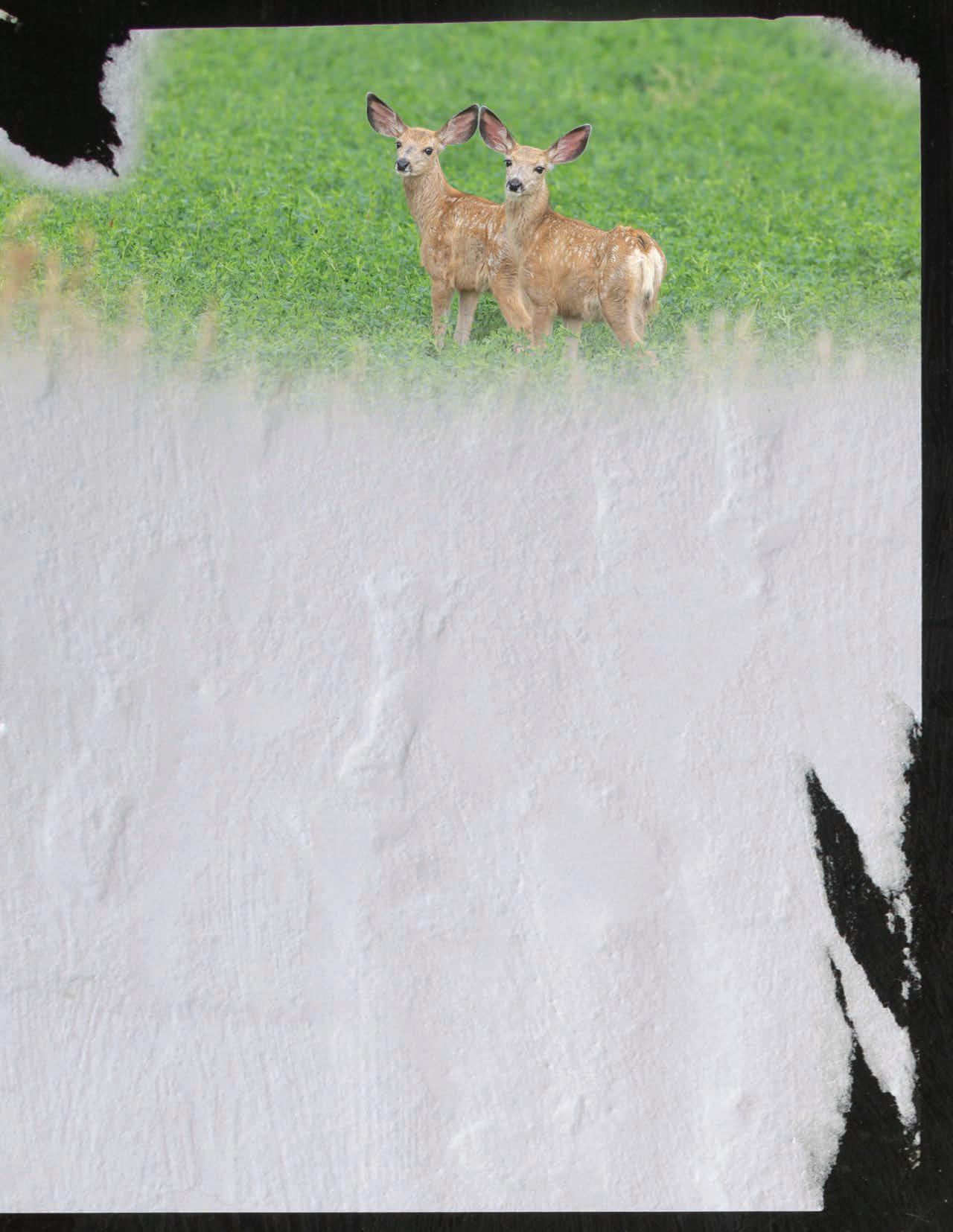

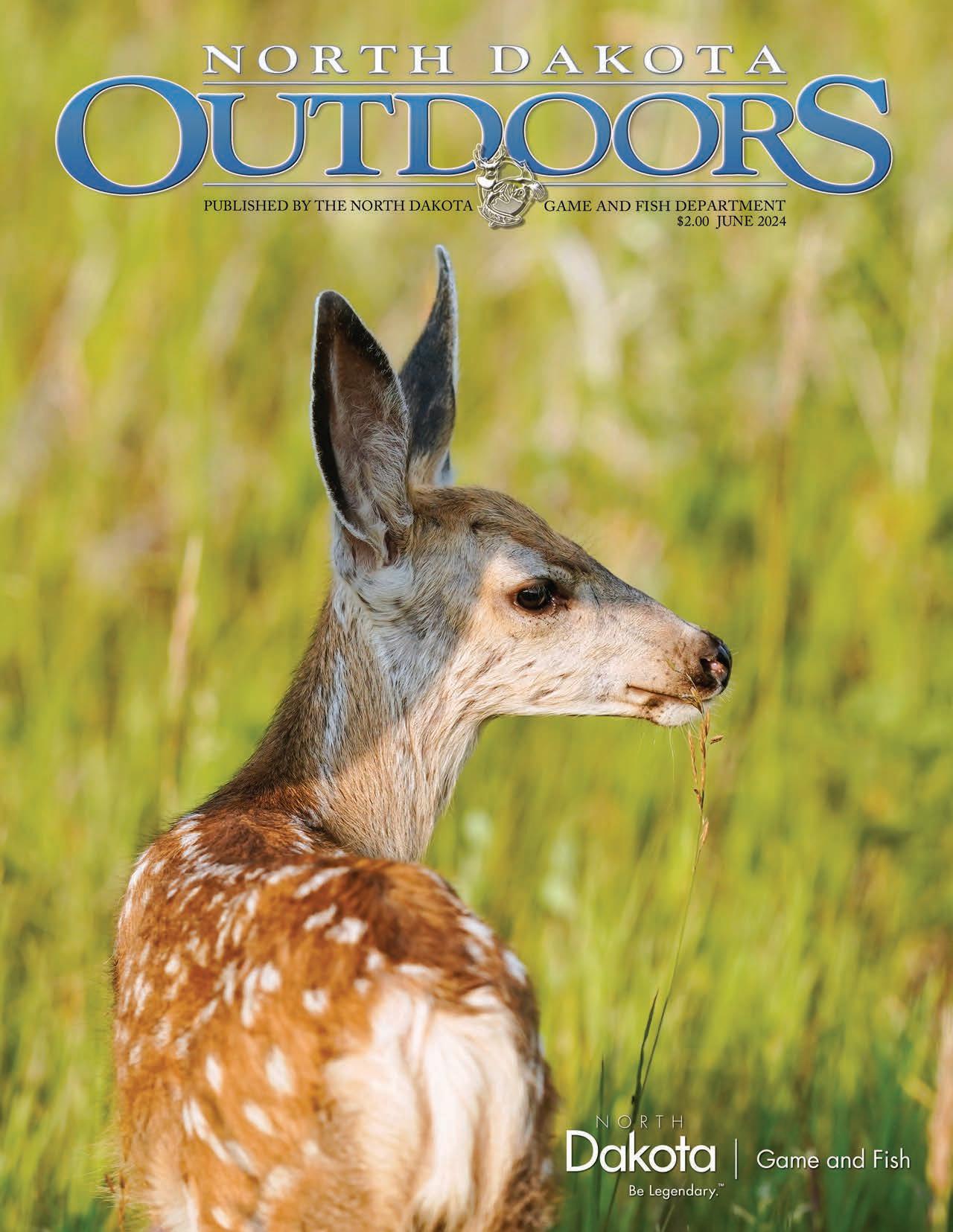

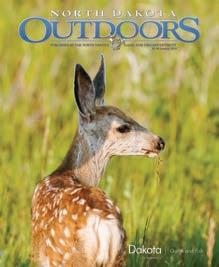

This mule deer fawn is exactly what wildlife managers hope to see more of this summer. Following the brutal winter of 2022-23, fawn production for both mule deer and whitetailed deer was down. After last winter, which was more reasonable in many regards, fawn production should be better.

PHOTO BY ASHLEY PETERSON.

JUNE 2024 • NUMBER 10 • VOLUME LXXXVI

CONTENTS

■

Front Cover

2 Study Follows State Bird 10 The Lure of Crappies 14 Slow Rebound 18 The Sound a Mirror Makes 22 Buffaloberry Patch 25 Back Cast

2 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

Andy Boyce releases a Western meadowlark in McLean County that was captured then fitted with a small GPS backpack earlier in spring.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 3

western W

estern meadowlarks arrive in North Dakota in early March and then turn and wing it south sometime in late October or early November.

That’s what scientists tell us about our state bird, an appealing songster with a recognizable call and unmistakable appearance.

Yet, compared to all that scientists do know about this common prairie species, there is some that they don’t, which is why researchers caught and fitted six meadowlarks with small GPS satellite backpacks in early May to track these birds throughout their movements across the entire year.

“Meadowlarks are extremely charismatic and anyone who’s spent time in grasslands throughout the country knows meadowlarks. They’re really an excellent symbol for our nation’s grasslands,” said Andy Boyce, research ecologist for the Smithsonian Migratory

Bird Center and the Smithsonian Great Plains Science Program, based in Missoula, Mont. “Surprisingly enough, even though they’re very well known to the average person, we don’t know really anything about their migratory ecology, which was one of the reasons for using meadowlarks in this study.

“Another reason is that they’re just a really good indicator of grassland habitat quality. They’re not the pickiest. I work with some birds like Sprague’s pipits, and they need 100,000 acres of native grass or else you won’t find them,” he added. “Meadowlarks are a little bit more flexible than that, but they won’t tolerate really degraded habitat. So, if you have meadowlarks using certain areas, that’s a good indication that’s valuable grassland habitat that needs protecting.”

Aside from the Smithsonian Institute, players in the study include the North Dakota Game and Fish Depart-

Setting mist nets.

Setting mist nets.

4 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

Employing a stuffed meadowlark to trick live meadowlarks.

ment, University of North Dakota and the Meadowlark Initiative, a statewide strategy that teams landowners, conservation groups, scientists and others to enhance, restore and sustain native grasslands in North Dakota.

Sandra Johnson, Game and Fish Department conservation biologist, said the study is funded by the Department through a state wildlife grant. The study will run through 2025.

Like the substantial loss of native grasslands in the state, roughly 75% over time, Johnson said there is a need to learn more about meadowlarks as their population is also on the decline.

“Western meadowlarks have been declining about 1% per year. I often get calls from people saying they just don’t see and hear meadowlarks like they used to,” Johnson said. “That stems from the fact that grasslands are being lost in North Dakota and elsewhere.”

To learn where these birds spend

their time throughout the full annual cycle, the GPS technology is critical as it gives researchers a fix on their whereabouts about two times per week.

“For a lot of more charismatic megafauna, whether you’re talking about deer or bison or prairie dogs, you can conserve them in one place because they’re staying in the same place year-round,” Boyce said. “With migratory birds if we want to effectively do conservation, we need to understand where they are throughout the annual cycle. So, if North Dakota’s got a problem with its meadowlarks, it needs to be communi cating with states like Kansas and New Mexico, for example, where those birds are spending the winter to make sure that there’s effective conservation going on there as well, because conservation of migratory species is only as good as the weakest link in that chain.”

Meadowlarks were caught in 30-foot mist nets that have a long history of

meadowlark

Meadowlarks are extremely charismatic and anyone who’s spent time in grasslands throughout the country knows meadowlarks. They’re really an excellent symbol for our nation’s grasslands. “ “

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 5

being safe for birds. The nets were placed near a prominent song perch like, say, a rock or fence post, that the target birds were using. Researchers also deployed a meadowlark decoy and a device that played the meadowlark song.

“Essentially, we’re trying to convince these birds that there’s an intruder in their territory they’ve got to deal with,” Boyce said. “Sometimes it takes a little bit of cajoling, but just enough to lure them into the nets.”

All the birds caught earlier this spring were males, which came as no surprise to researchers.

“When male meadowlarks are on the breeding grounds, they’re enraged and they’re dumb. They’re easy to catch because they’re willing to put themselves at risk to defend their territory,” Boyce said. “The females are a little bit more cryptic. They’re not going to respond to intruders nearly as much. The bottom line is males are just easier to catch. We hope we can tag females in the future.”

Boyce said researchers are pretty confident that the GPS fitted to the study birds has little if any impact on survival, movement or reproductive success.

“The guideline that we’ve come up with as a research community is that you don’t want to be putting any more than 3% of the bird’s body

mass on them in terms of weight. We total up everything including the weight of the harness, the weight of the tag … we total all that up and we are really careful about keeping that below the 3% threshold,” Boyce said. “We’ve got a lot of evidence that shows that if we’re below that threshold, we’re not having any negative impacts. Earlier this morning, for example, 45 minutes after we tagged our first bird, he was already singing and responding to the audio playback back on his territory, so we felt pretty good that he was feeling fine.”

Boyce said the first thing researchers look for after releasing a GPS tagged meadowlark is to make sure the backpack harness doesn’t encumber the wings and hinder the bird’s ability to fly.

“We also make sure we watch them until they come down and perch for the first time because the harness also goes around the legs,” Boyce said. “Usually, they’ll settle down after that first release flight. They’ll kind of shake everything out, preen their feathers out from under the harness, and as long as we see them walking around normally, we’re really comfortable that they’re in a good place, which happens really fast.”

The lifespan on a GPS tag is about 12 months or more. The harness is made of a soft plastic, string-

Meadowlarks (top) were caught in 30-foot mist nets that have a long history of being safe for the birds. A GPS backpack (middle photo) that was fitted to a captured meadowlark by researchers. A researcher (bottom photo) makes sure the GPS backpack is a perfect fit so it doesn’t hinder the bird in any way.

< 6 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

This is exactly what researchers want to see. An unharmed Western meadowlark, fitted with a GPS backpack that will alert researchers to its whereabouts for the next year or so, fly off to do meadowlark things.

like material that eventually breaks down and falls off the study birds.

“There’s been a lot of work done that shows that stuff breaks down right around 18 months to two years, just from exposure to UV on the landscape,” Boyce said. “Some of these birds can be quite long-lived, and we don’t want them toting this nonfunctional thing around for any longer than they have to.”

The meadowlark tagging study isn’t exclusive to North Dakota, Boyce said, as researchers are tagging Western, Eastern and Chihuahuan meadowlarks on breeding grounds across North America. The goal is to build a map that shows the connections between breeding and winter grounds for all three species of meadowlarks.

Boyce said researchers have already received some information from meadowlarks tagged in North Dakota in

2022. Of the four birds fitted with GPS backpacks, three provided a full annual cycle of data.

“Twelve months of data is pretty darn good. Two of those birds made a straight shot down to southern Nebraska, spent the winter there on some private land, while another bird went a little bit farther into central Kansas,” he said. “So, that’s given us kind of a first look at where our North Dakota population of meadowlarks spends the winter. Once we get up to 10 total tags, we’ll have a little bit better of an idea because there can be a lot of variation. These birds don’t necessarily all spend the time in the same place just because they breed in the same place.”

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

“ “

Twelve months of data is pretty darn good. Two of those birds made a straight shot down to southern Nebraska, spent the winter there on some private land, while another bird went a little bit farther into central Kansas.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 7

gf.nd.gov

CLEAN DRAIN DRY CLEAN DRAIN DRY EVERY SURFACE. EVERY TIME.

HELP KEEP ND WATERS CLEAN

Catch moreathanmemory! CHALLENGE

NORTH DAKOTA GAME AND FISH

The Lure crappies of

BY RON WILSON

North Dakota Game and Fish Department fisheries biologists have for the last 15-plus years set their survey nets in the shallows of Jamestown Reservoir to assess a fish not named walleye that draws anglers from near and far.

“Jamestown Reservoir has been historically and traditionally one of the better crappie fisheries in the state,” said Brandon Kratz, Department fisheries supervisor in Jamestown, of the fish species targeted in the reservoir in late May. “We’ve got good numbers and pretty good quality of fish.”

Prior to 2002, there wasn’t a limit on crappies and anglers could keep as many as they wanted. That year, the Game and Fish Department set the daily limit at 35 fish, and further lowered it to 20 in 2006 and 10 in 2014.

10 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

Kaitlyn Miller, Department seasonal fisheries technician, gets ready to release a crappie back into Jamestown Reservoir.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 11

“The reason we did that was some of the data that we collected suggested that we had good survival of crappies, not good recruitment. In other words, the fish don’t recruit to the population every year, but they tend to live long here so you can spread the wealth out over a longer period of time,” Kratz said. “That’s one of the cool things about Jamestown Reservoir, as well as the good spawning substrate for crappies. They’re successful every year in spawning for the most part, yet it’s the first winter that they have difficulty making it through.”

Kratz said when the Department set the 10-fish limit, anglers were supportive of the move.

“We found that when we have no limit or a liberal limit, anglers were fishing down those fish pretty fast,” he said. “And once we found that they lived longer and they were available year after year and not dying naturally, by lowering that limit and spreading that out, we have a more consistent fishery rather than the boom and bust as it used to always be. People tend not to like to have a great year one year, and then they make all the effort to plan a trip to a place the next year, and then they don’t catch anything. When you can have a little more stability, it’s usually better.”

Fisheries biologists set their nets in late May when the crappies were in shallower water and accessible. The trend information they seek from the population includes growth rates, length and weight, condition of the fish and sex ratios.

“Back in 2008 we dedicated a survey for the crappie population because we figured it was a pretty important resource … it’s one of the unique opportunities in North Dakota because we don’t have a lot of crappie fisheries,” Kratz said. “So, we focused more on trying to target those fish when they’re most susceptible to being caught, which tends to lead to better trend information so you can monitor the population a little better. And then we can evaluate whether our current limits and limits of the past were the right or the wrong thing to do and manage the fishery appropriately.”

What is it about Jamestown Reservoir that makes it such a good crappie fishery? Kratz said the reservoir is unique in that it produces a lot of plankton in summer, a go-to food source for smaller fish.

“While that food source is plentiful, our growth rates after about age 6 start to suffer, and they start to plateau out because plankton is good for smaller fish, but it takes a little bigger forage to grow fish quickly to bigger sizes,” he said.

“In combination with the abundant plankton is the spawning substrate … it’s fairly clean and there’s some gravel and shale that make for good crappie rearing areas. And then, of course, the flooding of the reservoir when the water gets high produces productivity that drives the food chain.”

12 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

Happy angler, Jackie Ressler of Bismarck, with a Jamestown Reservoir crappie caught earlier this spring.

While fisheries managers understand that crappies in the reservoir are easier to sample once they’ve moved into shallow water in spring, anglers casting in the shallows have also figured it out.

“Fish are going to be in less than 10 feet of water for the most part this time of year, and 6 feet is even better. That means that probably 75% of the fish population right now is within casting distance from shore, which folks really capitalize on using small jigs and light line,” Kratz said. “A lot of folks just use a fathead minnow suspended 2 to 3 feet below a bobber, cast offshore and just wait for crappies to come along. Get a pair of polarized sunglasses and you can also do some sight-fishing by just walking the shoreline on the right day when you have some calm conditions. Because the water clarity is usually clear enough, you can see fish on their beds and roaming around. Those fish are typically pretty active and easy to catch. It’s not hard to catch 50 crappies from shore this time of year on the right day if you are willing to walk a little bit.”

Come winter, when days of casting from shore are behind us, the lure of catching some good-eating crappies remains.

“Jamestown Reservoir attracts a lot of winter anglers. That’s probably the top fish people are pursuing out here. Walleye is a second of course, and perch fishing has been pretty good too,” Kratz said. “We did a creel survey in 2022 and anglers, during the winter at least, actually harvested about 30,000, and we estimated that they caught 50,000. And the crappies were nice as we estimated about an 11-inch average size, which is three-quarters of a pound or so. So, the crappie fishing was pretty good here the last couple winters.”

What

is it about Jamestown

Reservoir that makes

it such a good crappie fishery?

Kratz said the reservoir is unique in that it produces a lot of plankton in summer, a go-to food source for smaller fish.

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

The paperwork that comes with assessing the crappie population in Jamestown Reservoir.

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

The paperwork that comes with assessing the crappie population in Jamestown Reservoir.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 13

BY RON WILSON

“The problem with bad winters is that it curbs the deer herd in a hurry, and the rebuilding is awful slow. “ “

14 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

The winter of 2022-23 was a doozy.

Historic in some regards.

We remember it arriving in early November and loitering until sometime in April. Areas of North Dakota received 100 inches of snow or more over those six months, making life extremely difficult for some wildlife and deadly for others. Not surprisingly, an untold number of deer died that winter. The death toll was higher in some parts of the state than others. The fallout, and there were more than a few, was a reduction of nearly 11,000 licenses for deer gun season from the season prior.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 15

Depending on where you live, where you hunt, Mother Nature will need to help us out, but we’re also going to need habitat.

Understandable.

The reduction in tags, considering the number of deer that died of exposure and starved, coupled with the reality that many does were simply unable to have fawns, is something hunters can wrap their heads around.

But here’s the head-scratcher. Last winter was a doozy, too, but thankfully on the other end of the spectrum. Snow wasn’t an issue. Nor were agonizingly long, bitter cold stretches that hung around like unwanted houseguests. Yet, while deer and other critters were gifted a much-warranted winter that, if nothing else, increased the odds of does successfully birthing young, the Game and Fish Department again reduced the number of licenses by 3,300.

What gives?

“The problem with bad winters is that it curbs the deer herd in a hurry, and the rebuilding is awful slow. That’s especially true in those areas of the state where habitat is limited,” said Casey Anderson, North Dakota Game and Fish Department wildlife division chief. “The other thing that happened was that we had a lot of deer that didn’t have fawns coming out of that bad winter. Essentially, you’re talking a year where we didn’t have many animals recruited into the population.”

Anderson said wildlife biologists lean in a number of directions to determine the number of deer gun licenses to make available to hunters each fall. In addition to harvest rates and winter aerial surveys, which weren’t conducted last winter because of the lack of snow, Department staff monitor other population indices to determine license numbers, including depredation reports, hunter observations, input

at advisory board meetings and comments from hunters, landowners and Department staff.

“One of the big ones is hunter success and it tells us over time what’s happening on the landscape,” Anderson said.

Hunter success last fall, unfortunately, wasn’t great, about 55% statewide. In southeastern North Dakota, it was lower than that.

“In some of those southeastern units, we were closer to the mid-30s to 40% success. So, it was down considerably in some of those areas. And that’s where the reduction in the tags came from,” Anderson said.

Of the 3,300 deer gun licenses trimmed from the 2023 total, 2,600 were in southeastern North Dakota, a part of the state that was arguably hit hardest by the 2022-23 winter.

“I think in the areas where we reduced tags, those folks who live, breathe and hunt there probably understand. We heard from a lot of those folks in those areas, especially with the round of advisory board meetings, and we had some people say we didn’t drop the number of tags far enough,” Anderson said. “If you’re taking the bird’s eye view and you’re just looking at the whole state and you don’t happen to hunt or live in one of those areas where we reduced tags, you might be thinking, ‘Oh, boy, we had a pretty easy winter, so how can we be reducing tags?’ What it really comes down to is how we manage our deer herds unit by unit.”

To get the state’s deer population back to where their numbers are tolerable to landowners and where hunters would like to see them, Anderson said the answer is twofold.

16 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

“ “

“Depending on where you live, where you hunt, Mother Nature will need to help us out, but we’re also going to need habitat,” he said. “A lot of times hunters just think of where they’re hunting. They want habitat that’ll hold a deer or hold a pheasant, but that’s not necessarily what we need to increase the population. What we need is habitat that’s year-round, habitat that’ll help in those bad winters, habitat that provide places for does to have fawns, places for fawns to find cover to avoid predators …”

In terms of habitat, sometimes the little things like providing buffers around cattail sloughs could spell the difference between life and death for many deer during a tough winter.

“Cattail sloughs fill with snow at some point, but if we have some buffer that catches some of that snow so those cattail sloughs don’t fill up quite as fast, that just extends an animal’s ability to survive winter,” Anderson said. “A lot of times where we lose deer is during those March time frames when we get the last blizzard of the year. Their bodies are at the breaking point, but if we could gain another two or three weeks of reserves, we’d have a lot better chance of bringing some of those critters through those bad winters.”

Imploring for more wildlife habitat is something that Anderson and those wildlife managers before him have long lobbied for. While it may come off like a broken record to some, he understands the significance of gaining back some of what has been lost.

“I don’t know if I get tired of talking about our need for more wildlife habitat. It’s part of the job, right? What’s important is making people understand if they want more deer, pheasants and other wildlife on the landscape, that’s what it’s going to take,” he said. “People will ask about changing the way lotteries are divvied out, making it easier for people to get tags or whatever. I mean, these are really all band-aids to the problem. They may help you for a year or two, but ultimately, it’s going to take habitat on the landscape to get all hunters more opportunities.”

While it was more difficult to draw a deer license this year for some hunters, there’s hope things will be different down the road.

“We have the opportunity to see good number of fawns being added to the population this year,” Anderson said. “The body condition of does should be excellent coming out of winter, which could lend itself to some high fawn rates … high twin rates is the hope. But we’ll see as time goes on what the habitat looks like for their ability to have those fawns and keep them protected and make it through summer.”

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

DECADE OF DEER

A look at North Dakota deer gun licenses made available to hunters in the last 10 years.

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

2022

2023

2024

– 43,275

– 49,000

– 54,500

– 55,150

– 65,500

– 69,050

– 72,200

– 64,200

– 53,400

– 50,100

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 17

THE SOUND A MIRROR MAKES

BY ASHLEY PETERSON

It’s mid-May and we’re somewhere in McLean County. Ron Wilson and I are playing spectators from the vehicle as researchers set nets with intentions of catching a Western meadowlark. I have my camera resting on my trusty steady bag, documenting from afar. Amidst our casual conversation, Ron asked: “So, are you going to take a picture or what?” I smile, nearly chuckle out loud, before assuring him that not only did I have photos, but some video as well. “How can that be?” he said. “I didn’t hear your camera click.”

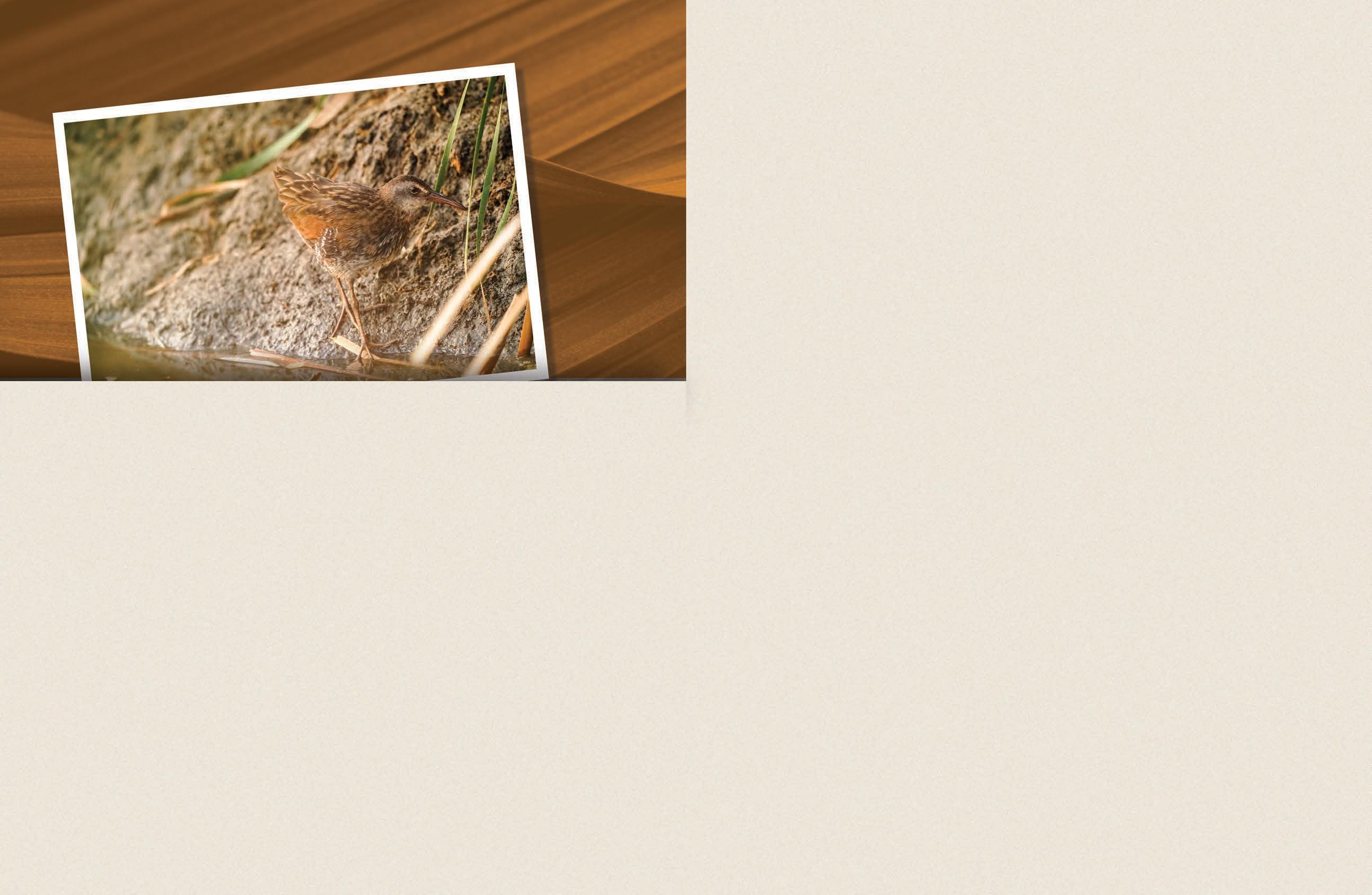

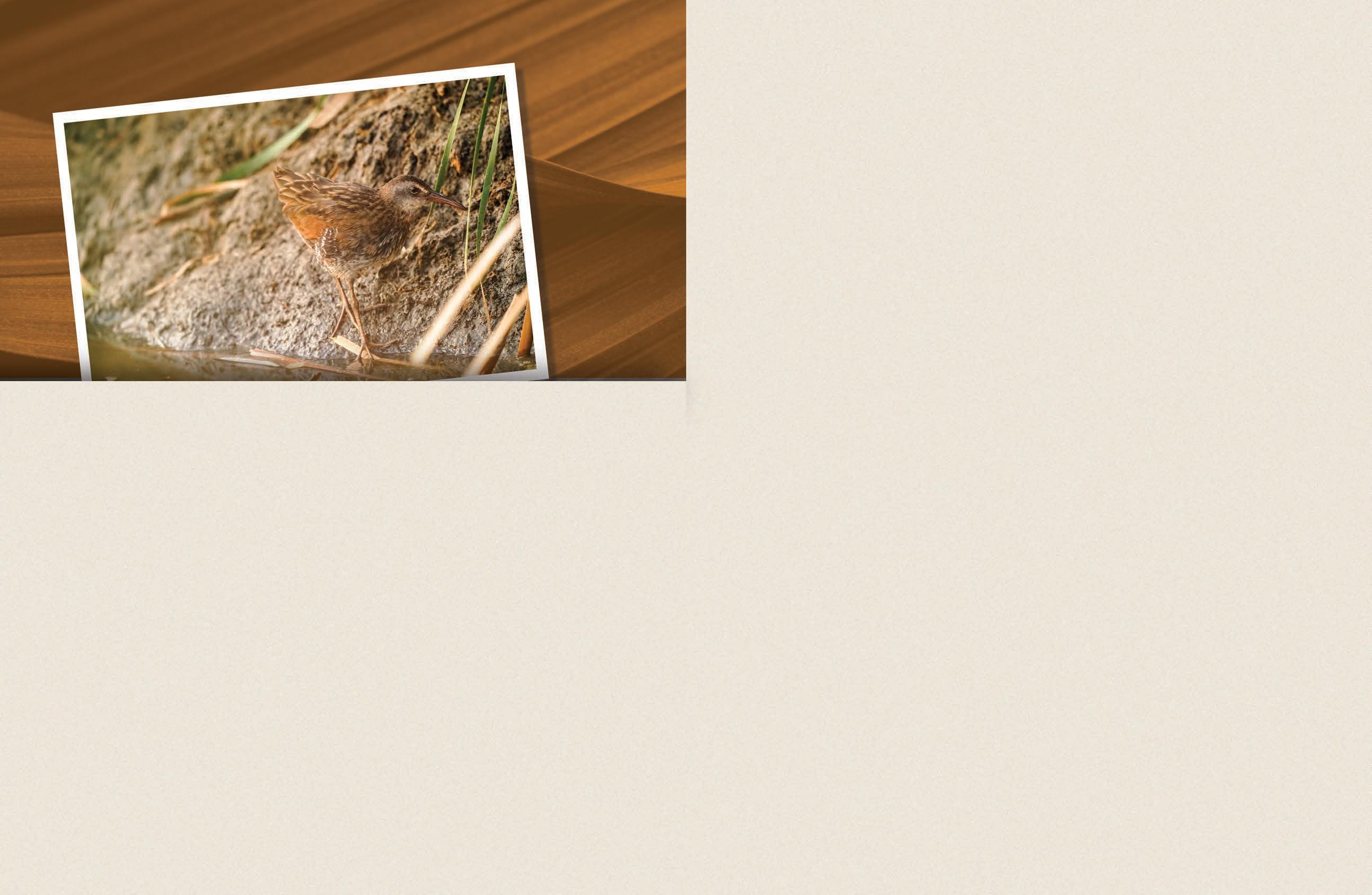

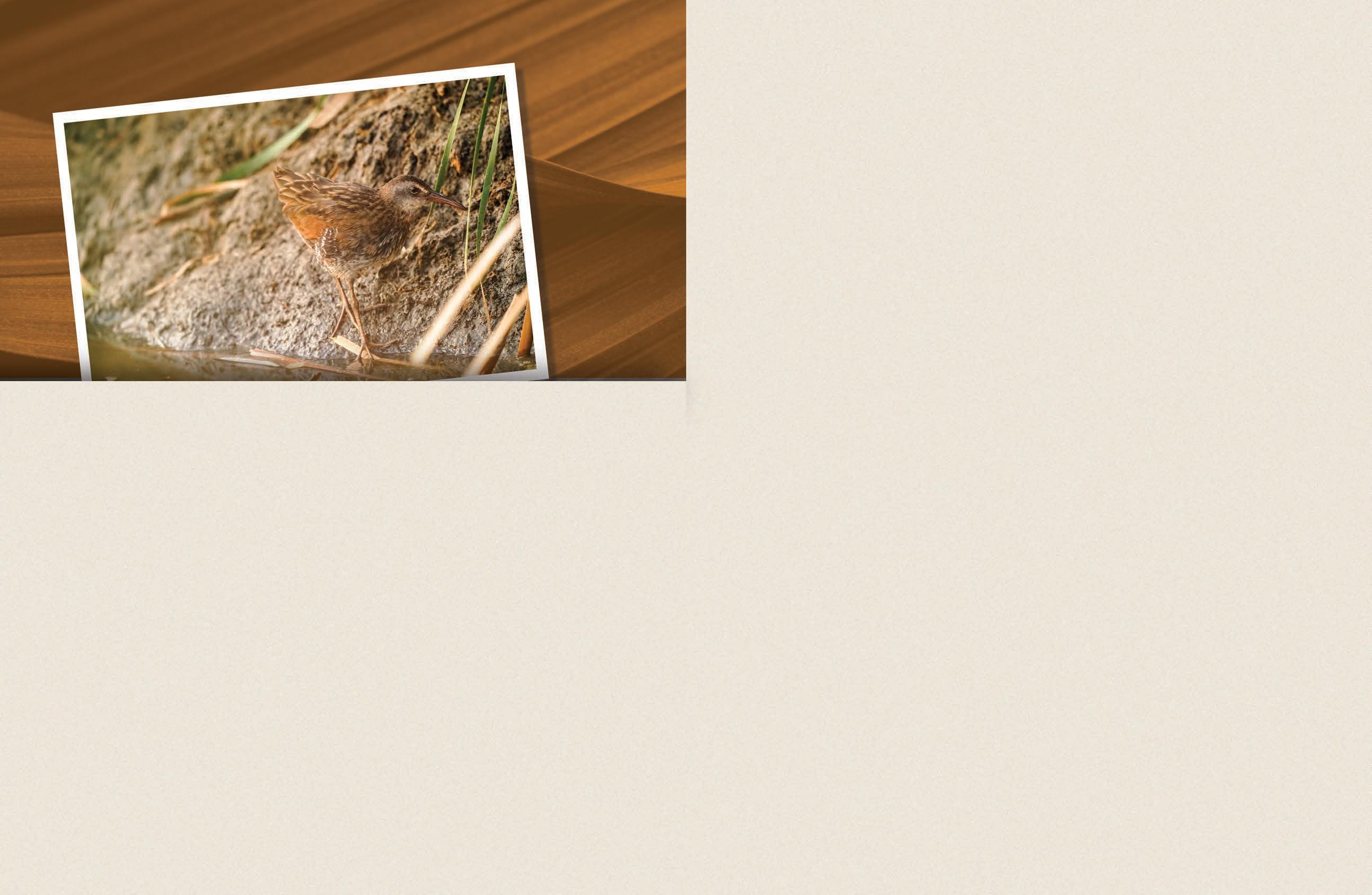

A secretive bird, the Virginial Rail is a tricky one to get in focus. I was lucky to even find one, and with the help of the mirrorless camera’s auto focus and tracking, I walked away with several keepers.

18 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

When a digital single lens reflex was the camera of choice at the time, I had my fair share of moments wondering how many photos I could get before the camera action would spook my critter subject. Some animals are more tolerant to the incessant clicking, affording me several minutes before bolting. Others would flee after just a single disruptive frame.

Some DSLRs offered a “quiet mode,” but I hardly found it quiet at all and the feature seemingly forced the shutter to operate slower. Which was certainly not ideal, especially for rapid-fire burst shooting. Enter the mirrorless camera world where, as you may have guessed it, the mirror is no more, rendering the shutter truly silent, not just quiet. That’s a gamechanger, especially for wildlife photography.

Like the time I was sitting in a blind on a sharp-tailed grouse lek, in the company of Jesse Kolar, Game and Fish Department upland game supervisor. In between birds dancing near and far, he clicked away on his own camera before pausing to whisper in my direction: “Are you shooting video?” To which I gently nod.

The less I disturb a wild animal while I’m a guest in its home, the better for that animal, and the more natural looking the images.

I was fortunate to sneak up on this mule deer buck pair undetected. With the help of the camera’s silent shutter, I captured a couple hundred frames before accidentally tipping them off.

The camera’s intelligent eye detection auto focus system tracked this sharp-tailed grouse/ prairie chicken hybrid through the grass until it was close enough to capture this image.

The camera’s intelligent eye detection auto focus system tracked this sharp-tailed grouse/ prairie chicken hybrid through the grass until it was close enough to capture this image.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 19

Shocking for largemouth bass was my first night shoot with a mirrorless camera. The assignment put my knowledge of the camera’s inner workings to the test.

“Oh,” he said, “I wondered why I didn’t hear your camera, but if you’re shooting video, that makes sense.” I quickly whispered back, “No, I have photos, too … see?” as I swiveled my camera’s screen to reflect the evidence. A quizzical expression took over Jesse’s face as he voiced some concern for his hearing. I suppressed a laugh before confirming his hearing was fine because my camera didn’t make noise.

The mirrorless camera’s “silent shutter” sparked a conversation for later, and perhaps inspired some research on my colleague’s part. While the clicking from Jesse’s camera didn’t seem to bother the birds, the ability to sit amongst them without making extra, unnecessary noise is a benefit in and of itself. The less I disturb a wild animal while I’m a guest in its home, the better for that animal, and the more natural looking the images.

Stepping into the mirrorless camera world has afforded me some new opportunities courtesy of the mirror’s absence. Take for instance a night assignment at Nelson Lake with our Department’s Riverdale fisheries crew shocking for largemouth bass. My previous experience with shooting on a DSLR meant I needed a decent light source (such as a flash or a bright, continuous light, ideally the latter) and preferably multiple, to assist with capturing a clear image. As the sun set and night

settled in, the only light I had to work with was that on the boat, which was minimal, and a small LED mounted to Mike Anderson’s video camera.

For context, video cameras typically capture better in low light than DSLRs. Much to my surprise, my little mirrorless camera stood its ground, offering clean images that I didn’t think would be possible, given the situation. Not only did it utilize what little light I had, I was afforded some steadiness assistance, courtesy of the in-body image stabilization. As I worked through that assignment, my initial concerns for blurry bass faded away upon reviewing a few frames on the back of the camera. As I processed those images the next day, I couldn’t help but be impressed with the clarity and color that resulted from shooting with such limited light.

Another perk of working with these cameras is the fast and accurately “sticky” auto focusing. Couple that with incredible frame rates for burst mode shooting and you have more options for “the perfect frame” than one would care to imagine. In some instances, upwards of 120 frames for each second the shutter button is held. While super fun in the moment, it’s a guaranteed way to tie me to the desk after the fact, sorting out keepers from the discarded.

For the meadowlark study, I knew we needed

20 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

a photo of the bird returning to the wild. At a minimum, a bird in hand, just at or right after the moment of release: wings unfurling, legs stretching out, transmitter antenna floating. Thankfully, due to the camera’s high burst rate, excellent auto focus and subject tracking, I successfully captured that exact scene … and nearly a dozen more until the meadowlark left the frame. The final images provided many options for the story layout and afforded me the ability to composite the sequence together into one cool frame. I couldn’t think of a better way to illustrate the meadowlark’s return to his world.

Despite the incredible advancements in digital photography in even the past decade, it’s easy to forget these little black boxes take more effort

Many of today’s mirrorless cameras offer high burst rates. This image is comprised of five different images, taken within seconds of each other, then composited into one image. The camera’s “sticky” autofocus tracking followed the bird as it flew through the frame.

than simply pointing and shooting. I humbly admit I needed hands on a camera weekly for the better part of a year to truly feel confident operating this gear. Even with that, my initial success rate was below 10%. After a few years of learning and growing with this camera, I’m happier with my average 25% keeper rate. Some days it’s more, while others it’s significantly less.

The takeaway of my experience is that no matter how advanced the camera is, you still need to learn how to operate it, practice often and be willing to step out of your comfort zone.

ASHLEY PETERSON is the Game and Fish Department’s photographer/videographer.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 21

BUFFALOBERRY PATCH

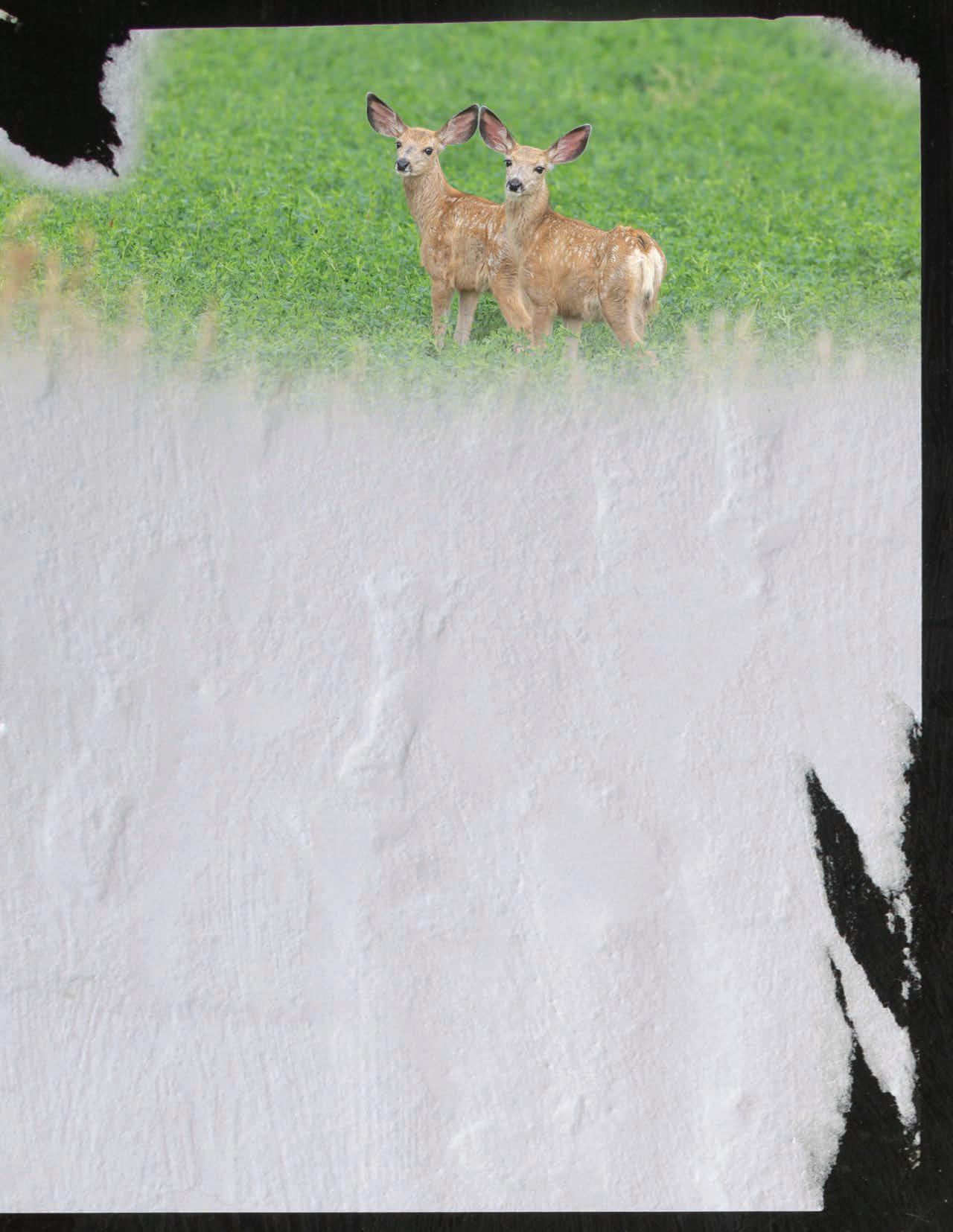

Mule Deer Survey Completed

Results of the North Dakota Game and Fish Department’s annual spring mule deer survey indicate western North Dakota’s mule deer population is 1% higher than last year but 4% below the long-term average.

Biologists counted 2,047 mule deer in 286.3 square miles. The overall mule deer density in the badlands was 7.1 deer per square mile.

Bruce Stillings, Department big game management supervisor, said mule deer densities remained the same compared to 2023 following last year’s record low fawn production, reduced gun harvest and a mild winter in 2023-24.

“The 2024 spring survey results were largely influenced by the 2022-23 record-setting harsh winter, which resulted in mule deer does being in poor body condition last spring and record low fawn production in 2023,” Stillings said. “This past mild winter with higher survival helped offset lack of fawns from the previous two years, which led to mule deer populations being similar to last year.”

Biologists are encouraged that last winter’s mild conditions could result in higher fawn production this summer, leading to an increased population in 2025.

Biologists counted 1,735 mule deer in the aerial survey in October to determine demographics in the badlands. The ratio of 57 fawns per 100 does was the lowest recorded since the survey began in 1964, and similar to fawn production in 2011 and 2012 (59/100) following the extreme winters of 2008-10. The 39 bucks per 100 does was similar to 2022 (40/100) and the long-term average (43/100).

The spring mule deer survey assess mule deer abundance in the badlands. It is conducted after snow melt and before trees begin to leaf out, providing the best conditions for aerial observation of deer. Biologists have completed aerial surveys of the same 24 study areas since the 1950s.

The fall aerial survey, conducted specifically to study demographics, covers 24 study areas and 306.3 square miles in western North Dakota. Biologists also survey the same study areas in spring of each year to determine deer abundance.

2023 Upland Game Seasons Summary

North Dakota’s 2023 pheasant, sharp-tailed grouse and gray partridge harvests were up from 2022, according to the state Game and Fish Department.

RJ Gross, Department upland game biologist, said the overall harvest was likely a result of more hunters, more trips and more birds in the population.

“Despite enduring one of the highest snowfall totals in history (winter 2022-23), we anticipated an increase in upland bird harvests based on increases in all our metrics (number of birds, broods, brood size and age ratio) during our late summer roadside counts,” he said.

Last year, 53,819 pheasant hunters (up 5%) harvested 319,287 roosters (up 11%), compared to 51,270 hunters and 286,970 roosters in 2022. Counties with the highest percentage of pheasants taken were Hettinger, Divide, Burleigh, Williams and Stark.

A total of 21,512 grouse hunters (up 5%) harvested 67,710 sharp-tailed grouse (up 8%), compared to 20,461 hunters and 62,640 sharptails in 2022. Counties with the highest percentage of sharptails taken were Divide, Hettinger, Williams, McLean and Bowman.

Last year, 20,313 hunters (up 6%) harvested 67,481 gray partridge (up 24%). In 2022, 19,125 hunters harvested 54,553 partridge. Counties with the highest percentage of gray partridge taken were Stark, McLean, Hettinger, Williams and Divide.

22 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

Angler Snags Record-tying Paddlefish

Tyler Hughes of Mandan snagged a record-tying 131pound paddlefish on May 3 in the Yellowstone River southwest of Williston.

The North Dakota Game and Fish Department has confirmed that the 74-inch paddlefish tied the record from 2016 by Grant Werkmeister of Williston.

The two fish are the heaviest caught and documented in North Dakota. The season was open to the harvest of paddlefish from May 1-15.

Fish Challenge Open

North Dakota is home to a wide variety of fish species and the state Game and Fish Department fisheries division works hard to stock waters across the state for angler enjoyment.

CHALLENGE

To encourage exploration of the state’s fisheries, anglers fishing in North Dakota are invited to complete the third annual Fish Challenge found on the Department’s website at gf.nd.gov.

New this year, anglers can choose to complete the Rough Fish Challenge by catching a bullhead, carp and sucker.

In addition, anglers can complete last year’s Sportfish Challenge by catching a bluegill, walleye, bass and trout, or the inaugural Classic Challenge requiring a northern pike, yellow perch, smallmouth bass and channel catfish.

Either way, the process is simple – snap a photo of each and submit your entry on the North Dakota Game and Fish website, gf.nd.gov, now through Aug. 15.

Anglers who complete a challenge will receive a decal and certificate.

Celebrating Wetlands

May was officially American Wetlands Month. Considering the Prairie Pothole Region in North Dakota has the highest density of wetlands in the world, celebrating these waters that benefit wildlife and humans could happen any month.

“Wetlands provide many uses for wildlife, especially ducks, as they offer breeding pair habitat, brood habitat, migration habitat,” said Mike Szymanski, North Dakota Game and Fish Department migratory game bird management supervisor. “With the cover surrounding wetlands, they’re also very important for other wildlife species such as pheasants, deer and other migrating shorebirds and water birds.”

While the state has lost nearly 60% of its wetlands over time, North Dakota remains the duck factory of North America.

“We are centered in the Prairie Pothole Region, and in the United States portion of the Prairie Pothole Region, North Dakota has about half of the breeding ducks,” Szymanski said.

To learn more about wetlands and the ecological goods and services these habitats provide, check out the NDO Webcast on the Department’s website and gf.nd.gov.

NORTH DAKOTA GAME AND FISH

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 23

Hands Off Baby Animals

The North Dakota Game and Fish Department offers a simple message to the well-intentioned who want to pick up and rescue what appear to be orphaned baby animals this time of year: don’t touch them. Whether it is a young fawn, duckling, cottontail rabbit or a songbird, it is better to leave them alone.

Often, young animals are not abandoned or deserted, and the mother is probably nearby. Young wildlife are purposely secluded by adults to protect them from predators.

Anytime a young wild animal has human contact, its chance of survival decreases significantly. It’s illegal to take wild animals home, and captive animals later returned to the wild will struggle to survive without possessing learned survival skills.

The only time a baby animal should be picked up is if it is in an unnatural situation, such as a young songbird found on a doorstep. In that case, the young bird can be moved to the closest suitable habitat.

People should also steer clear of adult wildlife, such as deer or moose that might wander into urban areas. Crowding stresses animals and can lead to a potentially dangerous situation.

In addition, motorists are reminded to watch for deer along roadways. During the next several weeks young animals are dispersing from home ranges, and with deer more active during this time, the potential for car deer collisions increases.

Healthy Burn

Historically, wildfires would naturally burn periodically across North Dakota prairies to rejuvenate native grasses. The North Dakota Game and Fish Department has been using prescribed burns for decades to do the same thing on wildlife management areas.

On April 24, Department staff conducted a prescribed burn on a 25-acre native grass planting at MacLean Bottoms WMA.

“This was planted about 10 years ago and it was getting quite a thatch layer of old dead grass and litter,” said Levi Jacobson, Department wildlife resource management supervisor. “This prescribed burn will clean that up, while also helping to reduce the cool season invasives such as Kentucky bluegrass and smooth brome.”

Jacobson and crew held a safety meeting before the burn to go over the exact plan for the fire, and then jobs, equipment and locations were assigned to each person. And because weather conditions that day allowed for a safe burn, it moved forward as planned.

“We notified the local authorities, such as the fire department, sheriff’s office and state radio. We also notified any close neighbors so if they saw smoke, they’d know what was going on and didn’t get alarmed.”

A week or two after the burn, thanks in part to timely rains, the 25 acres was already greening up and looking healthy.

“This will benefit wildlife by bringing in a little more diversity to this grass stand. Once these cool season invasives come in, they kind of take over and create a monoculture. And that really limits the fawning and brood rearing and just overall reproduction for wildlife,” Jacobson said. “We’re hoping with the burn, it’ll invigorate those native grasses that we planted a few years ago. So, with less competition, those things should thrive this year and really produce.”

24 ■ ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024

BACK CAST

I’m standing in native mixed-grass prairie with my head tilted back like a child trying to catch snowflakes.

I’m not playing, though, but looking for the composer of what scientists describe as a haunting, hu-hu-hu winnowing sound. As difficult as it is to spot the highflying bird, it’s even harder to remember the bird’s name, despite being reminded most springs by the very person who is just feet away scanning the sky with binoculars.

Wilson’s snipe, she says.

Duh, I mumble.

What I do remember is the winnowing sound is made by air rushing over the snipe’s outspread tail feathers as males dive to defend territories and attract mates.

The chunk of prairie we’re occupying this spring morning shoulders up against The Nature Conservancy’s 7,000-plus acre Davis Ranch, which is dubbed as one of the largest

By Ron Wilson

By Ron Wilson

critters. I’ve always found it hard not to live vicariously through these folks when I’m around them, wondering what it would be like to be them, to do what they do, go where they go and see what they see.

Sometime in the late 1990s, I spent a summer day trailing a young biologist in the North Unit of Theodore Roosevelt National Park as he wandered the rugged up and down looking for bighorn sheep released into the park in winter. We spent much of the day hiking and glassing likely hideouts, eating lunch out of our backpacks in pretty country and talking. I asked him if he’d bumped into any rattlesnakes, not knowing the answer would be 22, including the one that bit him on his hand earlier that summer a mile from his vehicle and several miles from Watford City where he was eventually treated by medical staff. And his obvious answer to my obvious question was, yes, it hurt.

Where we fish in Montana in summer, we see the random bear. Most of them are black bears, but there’s the occasional grizzly, including a young one that ran through camp as we were unloading gear. I bring this up because when I hear something crashing around in the woods on a stretch of river that I believe to have to myself, my thoughts immediately land on something big and hairy in the bushes.

Last summer, big and hairy turned out to be four researchers noisily bushwacking through the riverside underbrush looking for signs of a particular duck that spends the bulk of its life in salt water but is said to inhabit swift-moving streams during nesting season and summer.

Dressed in chest waders, and loaded down with heavy backpacks and tools, the most talkative of the four said they were researching harlequin ducks, a colorful and a seemingly wildly out-of-place bird in these parts that I was familiar with thanks to field guides and nature TV.

While we briefly visited about the weather, the beauty of the forest and the river that runs through their summer “office,” I got the feeling their search for signs of harlequins nesting in the thick streamside vegetation was slow going at best.

I wished them luck in parting, not adding that I’ve fished this stretch of river for 14 summers running and have yet to lay eyes on a harlequin. Yet, in all fairness, I spend little time as possible hacking around the underbrush because that’s not where the trout live, so who knows what I’ve missed.

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

Wilson’s snipe.

ND OUTDOORS ■ JUNE 2024 ■ 25

North Dakota Outdoors Magazine

North Dakota Game and Fish Department

100 N. Bismarck Expressway

Bismarck, ND 58501

To renew your subscription or change your address, call 701-328-6300 or go to gf.nd.gov/buy-apply.

Game and Fish Department fisheries personnel went into the spring walleye spawn with a goal of about 50 million eggs. While some eggs were collected from fish from Stump Lake, the majority of the nearly 70 million in total were taken from walleyes from Lake Sakakawea. Fisheries personnel began taking eggs from fish on April 25, which is the long-term average date for taking eggs on the big lake where this photo was taken.

connect with us gf.nd.gov/connect

PHOTO BY ASHELY PETERSON.

Setting mist nets.

Setting mist nets.

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

The paperwork that comes with assessing the crappie population in Jamestown Reservoir.

RON WILSON is editor of North Dakota OUTDOORS.

The paperwork that comes with assessing the crappie population in Jamestown Reservoir.

The camera’s intelligent eye detection auto focus system tracked this sharp-tailed grouse/ prairie chicken hybrid through the grass until it was close enough to capture this image.

The camera’s intelligent eye detection auto focus system tracked this sharp-tailed grouse/ prairie chicken hybrid through the grass until it was close enough to capture this image.

By Ron Wilson

By Ron Wilson