WHERE ARE THE WOMEN?

I made this collage from cutouts of the flagship publication of NOSTRA magazine, released in spring 2023 with the theme “21st Century Feminine.” This collection of poems, art, and short stories described the contemporary female experience from many angles, frequently alluding to the quiet sorrows and anxieties of women under pressure.

Inspired by the collection, I created the collage as a final assignment for my music appreciation course, which required us to visually depict a music performance. I selected a wordless viola piece called “Calm Panic,” composed and performed by Sixto Franco. Franco is a viola performer from Spain who specializes in chamber music—a classical genre defined by intimate group performances of warm, harmonic tunes. “Calm Panic,” however, is a dissonant and volatile piece, unlike typical chamber music. The bitter yet intimate melody fluctuates between turbulence and tragedy. To me, the piece expresses the daily symptoms of anxiety—sometimes at a weary, lingering baseline, and sometimes an explosion that is quickly suppressed.

Reading the NOSTRA magazine, I saw student pieces voicing the same quiet turmoil. They sought answers to the fears of loneliness, passing time, reproductive battles, and growing up. Women’s experiences, though too diverse to universally define, may have at least one common thread: calm panic amidst great pressure. The pressure contains, pushes, restricts, and chokes. Sometimes, the pressure seeks to silence too—and yet, it manifests into the collection of creativity seen before you.

This collage was made possible by the illustrations of graphic designer Becky Gipson and editors Emma Allen, Liv Tanaka-Kekai, and Mika Nijhawan. I am also grateful for the artistic work of contributors Ainsley Anderson, Khira Hickbottom, Ella Jeffries, Winna Xia, and Emilia Long.

Listen to Sixto Franco’s “Calm Panic” here:

Read the Spring 2023 NOSTRA publication here:

Dear NOSTRA readers,

In 1886, Josephine Louise Newcomb donated $100,000 (today worth 2.7 million) to the Tulane Board of Administrators. This donation helped establish the first degree-granting coordinate college for women in the United States: Newcomb College. Women’s colleges provided potential opportunities for future employment in a world where few options existed for women. Further, Josephine Louise specified that the educational institution that would be built should emphasize the teaching of skills related to the “practical side of life,” to provide women the resources to generate their own income.

This year’s issue asks simply: what does our labor mean? As women, non-binary and trans students, queer people, disabled people, and people of color, what does it mean for us to enter the workforce? We have grown up in a world defined by an unprecedented expansion of supply-chain capitalism, a decline in union membership, and the lingering effects of the 2008 recession. As Newcomb Scholars we are tied to the ongoing legacy of Newcomb College; exploring what our labor means is not just an intellectual exercise, but a deeply personal and urgent inquiry into our collective well-being and liberation.

We acknowledge our unique positionalities based on our gender, race, religion, nationality, and citizenship status which both provide us with opportunities and limit us. We recognize the generative power of capitalism and pull from feminist scholars who remind us that our economic system is not a totalizing force. Rather, it is a heterogeneous project. The editors of this magazine reiterate the need to understand how labor-capital relationships are defined by colonial histories, war, racism, sexism, and other systems of oppression.

As more doors open up for marginalized people to enter the workforce, we ask our readers to think about the ways our identities are mobilized–and weaponized–for the sake of a machine seeking seemingly unregulated growth. Will capitalism offer us equality? We affirm that although our economic system intimately shapes our lives and histories, we exist in a position of privilege as students at an elite university in the Global North. Keeping this in mind, we simply suggest to our readers a better world is possible.

NOSTRA was created to acknowledge and foster knowledge production outside of the traditional confines of academia. The editors of this magazine believe that art can serve as a vehicle for collective empowerment; on every page is the opportunity to challenge dominant narratives, dismantle oppressive structures, and envision alternative futures. The following poems, essays, and pieces of artwork touch on important aspects of economic life and gendered labor. We aim to create a space for ideas and radical thought to be shared through art. NOSTRA means ‘ours’ in Latin: a place to tell our stories, share our histories, and remind ourselves of the power of community and collaboration.

– NOSTRA Co-Editors-in-Chief Liv (’24), Mika (’25), and Ella (’26)

7

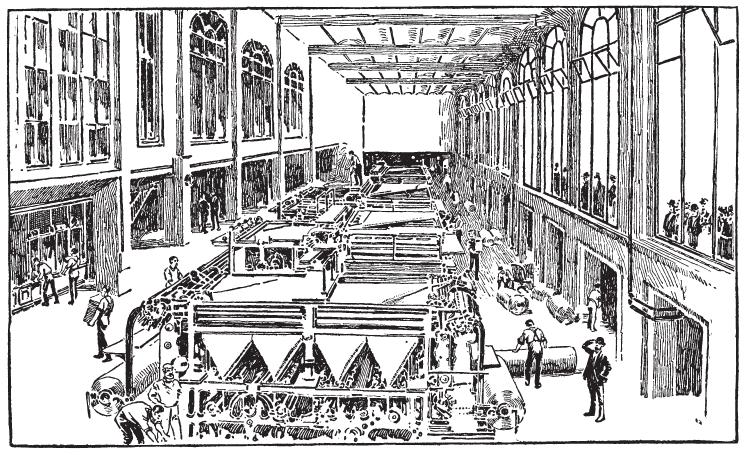

By Emily Maran and Ngoc Diep (Alice)The cover features collage by Rebecca Gipson featuring a vintage engraving of a 19th Century Steam propelled crane.

“Nostra” means “ours” in Latin. That is what we, the editors of this magazine want it to be: ours. A place of collaboration, elevation, and celebration of creative feminist works by Newcomb Scholars.

Editors

Liv Tanaka-Kekai (’24)

Mika Nijhawan (’25)

Ella Jeffries (’26)

Graphic Designer

Rebecca O'Malley Gipson (’21, *26)

Contributors

Zoe Friese

Emily Maran

Mary Evelyne White

Yubin Lee

Kate Alley

Ngoc Diep (Alice)

Amara Termes

Janey McGowan

Abigail Huddleston

Carlotta Harold

Lillian Milgram

Catarina Vazquez

Hilary Ouellette

Malai Harrington

Liv Tanaka-Kekai

Mike Nijhawan

NOSTRA is published by Newcomb Institute of Tulane University. NOSTRA is an annual production of the Newcomb Institute.

Address all inquiries to NOSTRA

Newcomb Institute | Tulane University The Commons, Suite 301 | 43 Newcomb Place

Orleans, LA 70118 | Phone: 1-800-504-5565

The issues that affect us, as students and as Scholars, are expansive. As a feminist magazine, we aim to include narratives from a variety of different perspectives and to tell stories outside the cultural hegemony. While we do not get the opportunity to put every submitted piece in the print magazine, the following works are also worth sharing. The two essays below are informative and thought-provoking, both for different reasons. Scan the QR codes to read more on our website!

Access to abortion and access to higher education are inextricably linked for those who can get pregnant. Further, the criminalization of abortion will have adverse consequences on women’s education, and therefore, future earnings and job perspectives. The response to the overturning of Roe v. Wade from American universities was varied, with Tulane notably taking a neutral stance. This essay explores the consequences of the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization on the Tulane population and the University’s response.

This essay explores the multifaceted experience of studying abroad, particularly the contrast between idealized perceptions and harsh realities faced by international students. The author challenges romanticized notions of the “American Dream,” and grapples with the loss of connection to the country they were born in. The piece delves into themes of alienation, dichotomy, identity, and FOMO (fear of missing out).

As a feminist organization, it is part of our ethos to create a magazine that is inclusive to all. We understand that written text is not always accessible to all people who may want to engage with it. For this reason, we created a more accessible version that is available online. The online magazine has text-readable image descriptions and utilizes Atkinson Hyper-legible font; Atkinson Hyper-legible is a typeface specifically created to be more legible for readers who are partially visually impaired. To access this version, scan the QR code.

“What are you knitting?” I’m asked, Nearly every time I crochet in public. My hands forming a structure of stitches For the sake of creating.

“I wish I knew how to do that,” I’m told, jealously, As I construct a garment skillfully, Only thanks to hundreds of mistakes And years of learning For the sake of creating.

“Can you make me a blanket?” I’m asked, After working on one of my own for six long months, Its growth consuming my days and nights For the sake of creating.

“I love it!” I’m told, delightedly, As my loved one opens their gift Made from my hands And my love And my labor For the sake of creating Both a piece of art And a smile on their face

“Have you ever thought about selling those?” I’m asked, As I sit and crochet at the end of my day, Unraveling my own worries And stitching together quiet threads For the sake of creating.

“People would pay so much for one,” I’m told, As if I haven’t thought that my labor Is worth something other than my own joy But where would that joy go If I assigned a price To a piece of my soul in textile form That I stitched together For the sake of creating

“My grandma taught me how to do that!” I’m told, “But I forgot,” they say, regretfully. Mine taught me too, and each stitch connects me to her And to every woman before me who has created For the sake of creating.

seventy-five majors

sixty-seven minors a forest of different careers that i am lost in.

with each tree its own path its own future

will i find my labor of love? enticed by the whispers of wealth swayed by my parents and peers

my own thoughts like stones my comfort my dictator my demise

what do i love enough to do for the next fifty years?

what do i love enough to fully devote myself to?

will it pay my bills?

embracing the frustration the confusion the uncertainty of it all

until i find my labor of love but as time trickles by she comes to me. she burrows into my heart and stays.

a purpose a passion a new life

the pull of motivation the exhilaration of epiphany and so i have found my labor of love.

“I don't want to go to school anymore,” I, the straight-A (almost) brightest student in the class, said, putting my head on my grandma's thigh with tears and sweat after a random school day.

That day, my teacher told us that school was not born for pursuing a passion, gaining knowledge, satisfying human curiosity, or any urge to learn. Ironically, school is a labor factory, and we are no more than a “perfect" or “defective" item. We are but “good” or “bad.”

Have you seen the film The Matrix (1999)? It proposed that humans live in a delusional world, as AI forces us to drain energy from our brains to become batteries. Have you seen yourself and humanity reflected there? We are living in The Matrix. School is the training program to optimize our battery life.

We are batteries fueling a system indifferent to our dreams.

From childhood, we're pushed toward "lucrative and stable" jobs instead of our passions. Creativity and love fade as we train for sensible careers.

Both my father's and mother's families encouraged me to pursue STEM and business studies because they were supposedly lucrative, secure career paths. And as a Vietnamese-Chinese born in a developing nation, Vietnam, that path is no longer a “should" but a big “MUST," or else you would be labeled as “useless," “failure," or “bad product."

At school, we learn skills to get stable jobs rather than pursue what we love and desire. Career advice is: “Don’t follow your passion; tolerate work that pays.” It’s realistic yet ironic advice.

For instance, they tell us: If you love creativity, consider marketing. If you love numbers, try teaching or computer science. If you love drawing, forget “unrealistic” careers like fashion or graphic design; choose architecture! If you love psychology, study business instead.

This platitude bombarded me daily, strangling my true aspirations. I loved writing with an intensity beyond reason. If I lost my hand, I’d learn to write with the other. If I lost both hands, I’d use my mouth, feet, or neck by any means I had to write. I was born to write, and I will use my whole life writing to capture the most blessed or tragic moment of human life!

I devoured fiction in primary school and have written compulsively since fourth grade. But writing supposedly leads to unlucrative, unstable jobs. What could I do—journalism, professional writing, secretarial work? My passion was deemed worthless, and I had to hide away my love as the most embarrassing thing in the world.

The most tragic moment was seeing my dad tear out my books and force me to throw them in the trash by myself.

Little did he know that I wrote that to overcome the cheating of my grandpa on my grandma.

Little did he know that those were the escape from the reality of my grandma crying every night and me sleeping next to her, trying to pretend to be asleep while holding my tears.

Little did he know that David—my delusional friend in the book I’m writing—and I were on good terms, and we were on the way to kill the villain to secure the world. To secure me from the rigid reality that writing is over-imaginative and unrealistic.

That night, I lost more than words on paper; I lost the piece of my soul that longed to be loved for my gift. Does this resonate with you—having your passion torn away the same way?

We sacrifice decades chasing someday dreams, only to watch our passion and vision wither behind dull paperwork. We retire with broken bodies and spirits, too drained to pursue long-denied dreams.

Who profits from this exploitation? The elite and privileged capitalists need us on the hamster wheel, toiling to enable their indulgent lifestyles. We generate power for everyone except ourselves—batteries robbed of light.

We must reclaim our right to inspired, purposeful lives. The matrix of mediocrity cannot contain our collective creative energy! My burning inquiry continued from Vietnam to America and then to Tulane University. I cannot abide by such systemic exploitation. We are made to be dead batteries while our humanity lies marginalized and unused! We value more than a battery or a source of labor!

Our dreams matter. Our stories matter. We matter!

Education provides sources to answer this question that compels me, and I’m still seeking it day to night, from books to practices, from the strangest dreams to the most realistic life.

What about you?

In the 1991 film Daughters of the Dust, Julie Dash creates a cinematographic space for Black women to be featured in ways previously never seen on screen by focusing on leisure time and the creation of the homeplace by and for Black women. As bell hooks explains, Black women use the making of homeplace as a form of resistance against the white patriarchal world, creating a space of care, safety, and warmth. She states:

Black women resisted by making homes where all black people could strive to be subjects, not objects, where we could be affirmed in our minds and hearts despite poverty, hardship, and deprivation, where we could restore to ourselves the dignity denied us on the outside in the public world.1

Daughters of the Dust exemplifies the creation of homeplace as a site of resistance through its centering of Black women’s domesticity and leisure time, memory and myth, and migratory realities. Not only does Daughters of the Dust depict the creation and maintenance of a homeplace, the film actively creates a sort of collective homeplace through the creation of an intimate, safe space for Black women on-screen. As bell hooks states, her “primary guides and teachers” in life were Black women, an idea that is evident in Daughters of the Dust: Nana Peazant is the matriarch of the family, and men generally take a back seat in the film.

Daughters of the Dust depicts the safety and warmth of the homeplace created by the Black women on the island, allowing scenes of rest, leisure, and

fun to take up space in the film. There are many scenes of the women dancing, singing, running, and just being playful on the beach; laughter often mixes with the background music in the film, becoming a part of the soundtrack itself. The film also purposefully focuses on the preparation and consumption of food and the celebration, relaxation, and leisure time that happens on Sundays. As Dash explains, “you don’t work on a Sunday, the day you’re saying goodbye to your greatgrandmother.”2 In one scene specifically, the women sit on the beach, shucking corn and preparing crab to eat. Although this is domestic labor, there is a sort of leisure in this scene: many of the women are lying down, many are talking, and there is a restful warmth to their cooking and food preparation. In an interview with Julie Dash, bell hooks says: “how many films do we see where the black folk are holding dirt in their hands and the dirt is not seen as another gesture of our burden?”3 The film allows Black people, Black women, to simply be, eating food, playing on the beach, doing each other’s hair, and working on the land without it being seen as the enemy or a kind of struggle. This is beautifully contrasted with scenes of pain, heartbreak, extreme sadness, and intimate moments between the women, detailing their collective and individual traumas. However, these grief-filled scenes also highlight the care and love created through domesticity and homeplace—there is a certain kind of safety in being able to share one’s sadness and troubles. One scene, in which Nana Peazant holds Yellow Mary as they touch foreheads (see fig. 1), emphasizes the warmth created through this sharing of grief and trauma.4 As bell hooks writes, the homeplace “was about the construction of a safe place where black people could affirm one another and by doing so heal many of the wounds inflicted by racist domination.”5 Yellow Mary can return home, be cared for, and have a break from her labor, a form of labor that she is subjected to because of racist and sexist structures.

Daughters of the Dust also depicts how homeplace is migratory and how Black people, especially women, create moveable homeplaces. One of the Ways in which Black women create these mobile

Fig. 1. Still from Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust. 1 bell hooks, “Homeplace (a site of resistance),” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, (Boston: South End Press, 1990,) 384. 2 Julie Dash, “Dialogue between bell hooks and Julie Dash,” in Daughters of the Dust: The Making of an African American Woman’s Film, (New York: The New Press, 1992,) 43. 3 Ibid, 42. 4 “Nana Peazant and Yellow Mary Touch Foreheads,” Daughters of the Dust, directed by Julie Dash (1991), Kanopy.homeplaces is through the collection of small keepsakes. Nana Peazant adds a lock of her hair to a small pouch (see Fig. 2), explaining that her mother gave it to her, with her own hair in it, before she was sold away.

Nana Peazant says: “There must be a bond, a connection, between those who go North and those who remain, between us who are here and those who are across the sea. A connection! We are as two people, the last of the old and the first of the new.”6 The physical remnants that Nana Peazant compiles create this connection; further, the hair acts almost as a seedling for the making of a new homeplace somewhere else. Nana Peazant cannot “physically make the journey north,” so she “send[s] her spirit with them” instead. 7 Her spirit, connected to the roots the family has established on the island, creates a moveable homeplace and a bond. This mobility is another site of resistance in the homeplace because the ability to create a safe space, especially when entering somewhere saturated with whiteness, is radical in its resistance to white patriarchal structures. bell hooks writes that “working to create a homeplace that affirmed our beings, our blackness, our love for one another was necessary resistance.”8 However, there is also pain and fragility in that mobility and the structures that require it. Dash speaks about the immense trauma that comes from having only small keepsakes to remind oneself of home and family: “if all you ever saw of your mother was a lock of her hair, that’s all you had, and that’s what you had to hang on to for the rest of your life…”9 Dash paints a picture of immense grief and sorrow that arises from not ever truly knowing your mother, and therefore your home. Even the title, Daughters of the Dust, emphasizes how there is a tenuous nature to the homeplace—and yet, even in the face of that fragility, Nana Peazant and other Black matriarchs create strong homes, and places of

love, tenderness, and healing.

The homeplace that Nana Peazant and other women create is also a site of resistance against white patriarchal structures because of the enduring African traditions and stories they uphold, such as the memory/story of Ibo’s Landing. These memories, stories, and myths are also a vital part of migratory homeplaces. As Dash says, “Without myth and tradition, what is there?”

10Just like Nana Peazant’s pouch of hair, memories and myths act as seedlings for creating homes in new places. These collective memories and traditions also resist the hegemonic whiteness and racist structures that attempt to erase African and Black realities and stories. The story/memory/myth of Ibo’s Landing “helped sustain the slaves, the people who were living in that region,” Dash suggests.11 In Daughters of the Dust, Eula is seen telling the story of Ibo’s Landing to the Unborn Child, passing on the memory/story, and planting that seedling of homeplace even before the child is born.

Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust does not just showcase the resistance created by and healing power of Black women’s homeplaces; it actively creates a space of resistance, safety, and healing, a kind of collective homeplace for its viewership—specifically Black women. bell hooks, in her interview with Julie Dash, spoke about the impact of Daughters: “Yesterday I interviewed a young black woman, a graduate student, and she said, ‘This was our paradise that we never had.’ And I found that exciting, because … you were giving us a mythic memory.”12 The film’s creation of a collective memory for Black women is a form of resistance against the white patriarchal world, creating space for Black female joy, storytelling, and leisure. Also, the film has a noted lack of whiteness; hooks writes, in “Homeplace (A Site of Resistance),” about how her home was a reprieve from whiteness, and white power and control13 Daughters of the Dust creates homeplace for Black women in its decentering of whiteness as well. Furthermore, the emphasis in the film is almost completely on the women, something that Dash speaks about in her interview with hooks:

Where the camera is placed, the closeness. Being inside the group rather than outside, as a spectator, outside looking in. We're inside; we're right in there. We're listening to intimate conversation between the women, while usually it's the men we hear

6 “Nana Peazant Monologue,” Daughters of the Dust

7 Dash, “Dialogue between bell hooks and Julie Dash,” 29.

8 hooks, “Homeplace,” 387.

9 Julie Dash, “Dialogue between bell hooks and Julie Dash,” 33.

10 Dash, “Dialogue between bell hooks and Julie Dash,” 29.

11 Ibid.

12 Ibid, 30.

13 hooks, “Homeplace,” 383.

Fig. 2. Still from Julie Dash’s 1991 film Daughters of the Dust

to intimate conversation between the women, while usually it's the men we hear talking and the women kind of walk by in the background. This time we overhear the women. So it's all from the point of view of a woman—about the women—and the men are kind of just on the periphery.14

The intimacy of Daughters of the Dust invites the viewer to be a part of the homeplace created in and by the film. The film envelops the viewer, almost in the way Nana Peazant holds Yellow Mary, touching foreheads (fig. 2), in a caring, loving, motherly manner.

When I tell people that I'm in a cross-stitching group, there is a response that I am all too familiar with. The laugh that quickly devolves into the realization that I am telling the truth. The confusion as to why a teenager would be interested in a hobby typically relegated to the realm of grandmothers. The "I wish I had that kind of time."

I bite my tongue as an instinctual desire to derail the train I know is already chugging along in their brain tells me to explain. To tell them that for thousands of years, women and girls have used their needlework as a way of interpreting the world around them.

Everything inside me wants to yell about the beauty of Navajo basketry and Hmong story cloth and Kuna appliqués. That if they took a moment to examine this art form before deeming it as rinky-dink domestic women's work, they would begin to understand the ways that women have used this medium to express themselves and their views of the world around them.

I want to scream that needlework serves as an artistic representation of the lives of women who existed below the strata of eliteness that is typically displayed in fine art. That our understanding of colonial forced assimilation practices is informed by studies of the needlework created by Aboriginal Australian girls during the 1840s. That a 19th century imprisoned woman named Agnes Richter would speak of injustice by embroidering her straight jackets in a German dialect that has been lost to time. That an enslaved Black woman named Lizzie Hobbs Keckley stitched her way out of slavery by selling quilts, eventually going on to work as a seamstress for Mary Todd Lincoln and creating quilts centered on themes of liberty and equality. That suffragettes would embroider their signatures on handkerchiefs, a means of inserting their name into the artistic narrative of history when their signature with pen and paper had little political bearing.

I want to say that in a world where women have been pigeonholed into domestic life, we have still taken the mediums used to confine us and made them into works of art that expand our influence in the world. That we have time and time again proven that feminine arts can become feminist art.

They aren't listening, but if they were I would tell them of the ways that we continue to stitch into the present day. Of our group's master crocheter. Of the woman who taught me to cross stitch. Of the embroiderer who never ceases to make me laugh. Of the unbelievable community that this silly little handicraft has created. Of the fact that this time and effort is not wasted because it allows us to make art and foster community and change our worlds one stitch at a time.

In the end, I merely tell them:

"We

meet on Tuesdays from 3 to 6 at the Labyrinth Cafe"

Through the eyes of a paramedic:

Your baby’s heart is now beating on its own, but they’re not breathing. I promise you we will do everything we can.

Your mother is no longer breathing. We are doing it for her. I promise you we will do everything we can.

Your son is dead. I promise you we did everything we could.

We speak these phrases – these words – to people with such fluency amidst disaster.

We watch as a person’s entire world becomes stricken with grief as we formulate sentences of simplistic letters.

We look into the eyes of loved ones and promise that we will try to save their person’s life because we are only human just like them – our promise to try is the best that we can give.

We promise and we pray and we hope and tomorrow we will see their souls in the skies and their faces in the clouds with you, even if they're not our human.

Because,

As a woman, I have held the hands of parents with pleading eyes and made a commitment to try.

As a woman, I have carried a child in my arms covering their eyes so they wouldn’t see their mother deceased on the floor of their living room.

As a woman, I have held a mother against my chest as her world collapsed because she will never hear her son say “I love you” again.

As a human, I have promised we will do everything we can.

I am learning to smile and mean it

Finally letting that warmth fill me up

Because sometimes the world is too beautiful to let it just pass by

Warm summer nights on my balcony overlooking the cemetery

I find so much peace in the passage of time

Small acts of remembrance immortalize all of those who came before Allowing me to imagine all of the futures that I could write

In an instant, I realize that I am filled with hope and curiosity

No longer chained to feelings of hopelessness and grief

Time stands still as I realize how deeply I have fallen in love with this life

I look around and I am surrounded by joy

Caught off guard, hot tears threaten to spill from my eyes

And I know that this is what they meant by happy tears

Marking the passage of time and an acknowledgment of fear, These tears defy everything that this world raises young women to be The vulnerability of this moment resonates through to my core

Standing in the hazy twilight air

I sway back and forth in the gentle embrace of memories

Pride envelops me

And I know that something within me has finally settled I am struck by the knowledge that when a cold world tried to harden me, I never resigned to its violence

You did not break me

No one ever will

I vow to show myself kindness

To give myself grace

I promise to hold myself close

To find empathy for my younger self

Forgive her mistakes

And walk into tomorrow knowing it is a new day

Something so simple has never meant so much

And I watch as a tiny crack begins to spread

Weaving its way across everything that I have ever known The wall holding back a lifetime's worth of love and loss shatters

I finally understand

I have never been much for wanting In reality, I was just too scared to admit that I had anything to lose I tricked myself into my own complacency Always running the party line…

I have never been much for wanting But I want this…

I want this life…

This love…

I crave it in a way that I have never needed anything before

I am falling in love with the sun and am learning to worship the moon Asking myself crazy questions like, What if the wind really just is trying to tell us something we don’t know how to hear?

I don’t know, Maybe it always was…

Calling out to anyone who would listen

Begging us to open our hearts

To let the world come crashing in To feel it all

Without hesitation

And to stop looking back

As I get better at listening to the universe

I hope that I learn how to run into tomorrow with open arms

Embrace love in a way that I have never even imagined possible And find a peace so profound that even my worst days will feel small in comparison

For the first time, I believe I will find this And if not, I will build it

Because inch by inch will eventually become miles

And one day when I am no longer surprised by the sound of my own laugh I will wake up in this life I have fought so hard for And I will know to thank the girl I am today

For this will always be my greatest labor of love

In 1886, Josephine Louise Newcomb made a groundbreaking contribution of $100,000 to the Tulane University administrative board, paving the way for the establishment of the H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College.1This endowment marked the birth of the first degreegranting coordinate women’s college in the United States, championing both academic excellence and practical life skills for women.2 With a vision that extended beyond mere literary pursuits, Newcomb aimed to equip women with tools for success in the real world. One such endeavor was the introduction of pottery craftsmanship as a means of providing women with practical employment opportunities.3 However, regardless of its noble intentions, this mission encountered numerous obstacles along the way. Students at Newcomb College faced restrictions in fully embracing pottery craftsmanship, and the employment landscape post-graduation was limited primarily to the Newcomb Pottery Enterprise. Moreover, the early stages of the college were marked by predominantly male leadership. Despite its challenges, the story of Newcomb College serves as a testament to the evolving landscape of women's education and vocational pursuits, urging us to delve deeper into the complexities of gender equality and opportunity in academia, the workforce, and beyond.

Newcomb's aspiration to educate women in potterymaking was hindered by the college's prohibition on female students participating in clay throwing— an essential technique involving shaping clay on a spinning wheel. This hands-on process, deemed "unladylike" due to its physicality and messiness, was reserved for men, reinforcing gender norms that equated certain activities with masculinity.4 By denying women the opportunity to engage autonomously in this fundamental aspect of pottery-making, Newcomb College confined them to more passive roles, perpetuating societal constraints on women's participation in traditionally maledominated crafts, and straying from the college’s mission of enabling middle-class women to support themselves through pottery sales. Students, termed "decorators," worked within an arts and crafts framework at Newcomb College. This label, while adequate, didn't empower them for independent commercial endeavors.5

1 DD. B. V. Blarcom, "A Brief History of H. Sophie Newcomb Memorial College, 1887-1919: A Personal Reminiscence," Friends for Newcomb College, 1995.

2 "The Letters of Josephine Louise Newcomb," Josephine Louise Newcomb Letters Project, accessed February 11, 2023.

3 "Newcomb Arts & Crafts." New Orleans: Newcomb College.

4 "Newcomb Pottery," Newcomb Art Museum, accessed February 11, 2023.

Arguably, this did not take away from the women’s artistry since the respected art form at the time was the applied motif or surface treatment of the pieces, rather than the industrial clay shapes themselves. Yet, the ongoing recognition afforded to Joseph Meyer6, an early potter for the Newcomb Pottery Program, and George Ohr7, another notable craftsman associated with Newcomb, undermines the contributions made by female students. In many digital galleries, these male potters who threw pieces for the class receive just as much credit for Newcomb pottery pieces as the female students who designed them. This practice dismisses the woman’s role in the pottery’s initial development and only credits her with the final adornments. For example, the Princeton University art museum webpage that talks about its Newcomb pottery exhibits labels photos as “Newcomb Pottery, Lillian Anne Guedry (decorator); Joseph Meyer (potter)” or “Newcomb Pottery, Harriet Coulter Joor (decorator); Joseph Meyer (potter)”.8 The Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service even credits a Newcomb pottery piece on its website as “Unknown decorator; Joseph Meyer, potter.”9 The sidelining of women's contributions to pottery, relegated as mere decorators, perpetuates gender stereotypes and denies them due recognition for their artistic endeavors as the minds that dreamt up the pieces. Specifically, these “decorators” directly instructed Joseph Meyer, explaining the structure and shape they wanted their pots to be. Rather than breaking new ground, these practices inadvertently reinforce old norms, limiting economic mobility and illustrating the marginalization of women's labor under capitalism notwithstanding efforts for independence and expression.

Graduates of the Newcomb Pottery Program encountered another significant obstacle: they lacked crucial clay construction skills, limiting their job opportunities. Without mastery of this essential skill, their income-generating potential remained untapped. This left them dependent on employment within the confines of Newcomb College, particularly within the Newcomb Pottery Enterprise. Essentially, they were cornered into working for the college, unable to fully explore other avenues for their talents and skills. O ther groups besides Newcomb existed,

5 Gardiner Museum, "Women, Art, and Social Change: The Newcomb Pottery Enterprise," YouTube video, 2015.

6 S. Saward, "Joseph Fortune Meyer," 64 Parishes, February 8, 2019.

7 Ohr-O'Keefe Museum of Art, "George Ohr," Ohr, January 14, 2021.

8 The Trustees of Princeton University, "Women, Art, and Social Change: The Newcomb Pottery Enterprise," Princeton University Art Museum, accessed February 11, 2023.

9 Smithsonian Institution. “Newcomb Pottery: Vase.” Smithsonian Institution. Accessed March 23, 2024.

Vase, 1897. Daffodil design.

Underglaze painting with glossy glaze. UNKNOWN DECORATOR; Joseph Meyer, potter. On loan to the Newcomb Art Gallery from Ruth Weinstein Lebovitz. (Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service)

like the Saturday Evening Girls10 or the Rookwood Pottery Company,11 which created a space where women could work designing pottery in the style of the arts and crafts movement, but these pottery enterprises were mostly in the North. While admirable enterprises, they were far enough from Louisiana that any Newcomb Pottery student hoping to work locally was practically obligated to stay at Newcomb. As a result, a pipeline was formed where Newcomb Pottery as an academic program served as employee training for the Newcomb Pottery Enterprise. While it was active, Newcomb Pottery hired back about ninety of its graduates, who went on to produce approximately seventy thousand pieces of work to sell through the college.12 As a model industry providing opportunities for women, the Newcomb Pottery Enterprise did a great job of creating employment, but as a school trying to prepare women to be more self-sufficient, Newcomb College failed due to the highly limited scope of opportunities available to its graduates.

On top of all that, the initial lack of female instructors, coupled with a predominantly male pottery-throwing team, created a dearth of female faculty members in a program tailored for women artists. However, whether intentional or not, the college rectified the situation with its practice of hiring back its own graduates. Notably, Sadie Irvine, a 1906 Newcomb College alumna, eventually joined the faculty after honing her craft as a pottery artisan, as did Ida Kohlmeyer, another alumna in painting and sculpture.13 Observing women in influential roles within the Newcomb Pottery Program served as a source of inspiration and encouragement for female participants. One of Sadie and Ida’s students, Donna Frances Swigart Vella Steg, recorded an oral history with the Newcomb archives where she spoke about her time studying painting and etching at Newcomb, and the influence of her female role models in the arts. Ms. Frances said, “I had had Sadie Irvine for four years, and then I was very close to Ida Kohlmeyer… I knew those women were just

10 "The Art World," Girls' Club Establishes Pottery and Ultimately Makes It a Financial Success: Wright, Livingston, Free download, Borrow, and streaming, JSTOR, September 1, 1917.

11 Art Of Estates, "The History of Rookwood Pottery in Cincinnati Ohio," Art of Estates, February 7, 2023.

12 "History of Newcomb College," History Of Newcomb College | Newcomb Institute, accessed February 11, 2023.

as powerful as anybody else.”14 Despite the scarcity of female leaders in the department compared to men, Ms. Frances found motivation in seeing her female teachers’ commitment level and the respect they received. However, for the first few classes of Newcomb College art students who graduated before Ms. Frances, the faculty composition did not reflect the idea that women could pursue vocational opportunities in this profession.

The mentorship bond between Irvine, Kohlmeyer, and Frances emphasizes the importance of up-and-coming professionals visualizing themselves in respected, influential positions within their fields– something Newcomb College took a minute to realize.

The Newcomb College pottery program aimed to train students not only as artistic designers but also as industrial producers. However, the fact that the women graduating from Newcomb College had an understanding of how to put their aesthetic knowledge to profitable use did not mean that there was a breadth of opportunities for them to do that. Relying on male potters and employment within the Newcomb pottery enterprise, the women who participated in the Newcomb College pottery program found themselves significantly constrained in their ability to achieve self-sufficiency upon completing their studies.Women benefited from the Newcomb pottery enterprise and served as role models for subsequent generations of Newcomb Pottery Students, though this speaks more to Newcomb College as an equitable workplace than as a pre-professional school. In essence, the narrative of the Newcomb Pottery Program unveils not only the program's flawed inception but also its lasting implications for women's educational and vocational opportunities. It serves as a microcosm of the broader societal challenges women face in pursuing autonomy and recognition in their chosen fields, urging us to reflect on the persistent barriers to gender equality in the workforce and the ongoing imperative to dismantle them.

13 “Ida Kohlmeyer," Smithsonian American Art Museum, accessed February 11, 2023.

14 Willinger, B., & Tucker, S. "The Letters of Josephine Louise Newcomb." Josephine Louise Newcomb Letters Project. Accessed February 11, 2023.

This past semester, I took ANTH 3090: Menstruation: Biology + Culture with Dr. Katharine Lee. As part of the course, we were given the opportunity to complete an independent project. We spent the first part of the class learning about reproductive biology, and I was surprised to learn how much I did not know about my body. Though I took biology and anatomy courses in high school, little time was spent on the reproduction unit, so this was the first time I learned how ovulation works and how different sex hormones influence our cycles and our bodies.

Estrogen, progesterone, Luteinizing Hormone (LH), and Follicle Stimulating Hormone (FSH), the female sex hormones, drive the menstrual cycle and impact the female body in a myriad of ways1. Even small imbalances or sudden changes in these levels can give rise to disorders such as Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) or Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD), which can significantly impact quality of life if untreated2. Oftentimes, it seems that ovulation is viewed as a separate process from menstruation since it is internal and invisible, but the hormones involved in ovulation are integral to our experiences as menstruators. For my final project, I wanted to learn more about ovulation and also to understand how the birth control pill, which twenty-five percent of women aged fifteen to forty-four who use contraception take daily, affects sex hormones3. Additionally, I wanted to explore the social narrative of the birth control pill and how the media that we interact with every day influences our contraception choices and ultimately the processes occurring in our bodies.

I have always been a visual learner and retain information better when it is presented in an engaging, creative way. When ovulation and hormone cycles are presented in textbooks and journals, it is often through dense, difficult-to-understand text and confusing flowcharts that are only accessible to a small number of people. I wanted to come up with a way to present this information in a manner that is engaging, memorable, and readable to anyone who wants to learn. Despite not having experience with sculpture, I decided that this would be the best way to convey my findings. I spent time sketching preliminary ideas and decided to incorporate clay into my piece as I have a background in ceramic work. Thus, I decided to make a giant, uterus-shaped ceramic structure. I worked with Professor Ina Kaur, a ceramics professor in the studio art department, who allowed me to come into her class to work on my piece and guided me through the construction process. Usually, ceramic pieces are glazed after the initial bisque firing in the kiln. Instead, I decided to collage the entire surface and then add items that are related to menstruation, pregnancy, and female cycles.

The collage materials include journal articles, news articles, text from online health sites, and social media posts that portray birth control pills positively or negatively. This is the type of information many menstruators interact with regularly, and it may influence their views on certain methods of contraception, especially when they are performing causal research to learn more about birth control pills for personal use. I conducted searches across different platforms using the same keywords: “The birth control pill,” “Birth control pill effects,” “Birth control pill negative/cons,” and “Birth control pill positive/pros.” I performed these searches in the Google, Microsoft Bing, and Ecosia search engines, across Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok, and on the CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC websites. Additionally, I searched for journal articles and books that aligned with these keywords. I selected the first few results from each search, screenshotted and printed out sections of the material, and divided my findings into two categories: media that negatively portrays hormonal birth control and media that positively portrays hormonal birth control. I split my sculpture in half and decided to have one side depict “natural” hormonal cycles and menstrual processes and used materials that reject birth control pill use on this side. The other side depicts hormonal cycles as they would be affected by the combination pill and includes materials that support birth control pill use. I used wires and beads to map each side’s respective hormone cycles and referenced class materials and outside sources to understand the differences between them. The uterine tubes and fimbriae are made out of menstrual product packaging, and other items such as pregnancy tests, tampons, and birth control pill packets are also included on the surface.

Birth control pills allowed menstruators to enter the workforce, have been used to treat menstrual disorders, and grant users choice and opportunity in their daily lives. It is also important to remember that these pills were first tested on people who lacked agency and who could not give informed consent, such as low-income women seeking infertility treatment in free clinics, patients in mental hospitals, prisoners, and women in housing projects in Puerto Rico4. The pill was first sold under the guise of regulating menstruation, as contraception was not legally available to everyone in the United States until the Eisenstadt v. Baird Supreme Court ruling in 19725. Though legal, the birth control pill remains a highly politicized topic today, and we regularly interact with a variety of contradicting, influential perspectives on the pill from many different sources. To make the best choices for ourselves, we must demystify the process of ovulation, understand how the pill affects sex hormones, and recognize how the media that we interact with can shape our experiences as menstruators and beyond.

1 Eric P. Widmaier, Hershel Raff, Kevin T. Strang, and Arthur J. Vander. Vander's Human Physiology: The Mechanisms of Body Function. (New York: McGraw-Hill Education, 2014).

2 Ibid

3 Danielle Cooper, Preeti Patel, Heba Mahdy “Oral Contraceptive Pills” In StatPearls (Treasure Island: StatPearls Publishing, 2022)

4 Nelly Oudshoorn, Beyond the Natural Body: An Archaeology of Sex Hormones (London: Routledge, 1994).

5 Eisenstadt v. Baird, 405 U.S. 438 (1972).

“You ain’t free, I ain’t free and our freedom is only going to come from being in community, building, fighting, and taking risks. It is risky. But what is the alternative exactly? Just staying on this lonely, isolated, deeply depraved path to nowhere and then we die having done nothing, lived nothing?”1

The modern woman is a lucky one–she can go to the office, work her 9:00-5:00, and come home in time to tuck her children into bed. As Sheryl Sandberg, former Chief Operating Officer of Meta, wrote in her book, she can lean in 2 By leaning into her ambitions, she can have it all: a rewarding career and a happy family. Those of us privileged enough to be afforded an elite university education and later be awarded a “high-skill” job have reached the pinnacle of success inside and outside the home. For the first time, over 10% of Fortune 500 CEOs are women, and the C-suite of Raytheon and Lockheed Martin have three and four women, respectively.3 Now–more than ever before–women are in the room when the U.S. Department of Defense decides to drop bombs. Hallelujah!

Ido not take this reality lightly, in fact, I am angry. I am angry all the time. This bit of fabricated existence being offered to us is just that: an ideal, a falsehood, a fabrication. Maybe if you are white enough, able-bodied enough, and palatable enough, these doors will open for you. But, Sheryl Sandberg is not leaning into anything. For many of these lucky women, they get to transfer care work and homemaking to another woman: a housekeeper or a babysitter. bell hooks points this out in her essay “Homeplace (A Site of Resistance),” writing that many of the black women she looked up to as a young girl made their living by tending to white people’s homes, specifically washing clothes, cooking dinner, and watching their children.4 Without a doubt, the vocational opportunities I–and maybe you–have access to have grown. However, in the process of gaining entry to boardrooms and executive teams, women have “leaned in” to exploit gendered labor. Home-making has been outsourced, oftentimes, to other women who are poorer and browner.

1 Dr. Ayesha Khan (@wokescientist), “At some point people in the west will realize…” Instagram photo, March 24, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C45zBquO59H/?igsh=MXJzZ3R4Y2w1OTlnZA%3D%3D.

2 Sheryl Sandberg, Lean In: Women, Work, and the Will to Lead (London: WH Allen, 2013).

3 Elting, Liz, “New Year, New Glass Heights: Women Now Comprise 10% Of Top U.S. Corporation CEOs,”Forbes, January 27, 2023; “Executive Leadership,” Lockheed Martin, accessed March 25, 2024, https:// www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/who-we-are/ leadership-governance.html; “Our Leadership,” Raytheon, accessed March 25, 2024, https://www.rtx.com/ who-we-are/our-leadership.

4 bell hooks, “Homeplace (A Site of Resistance)” in Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics. (Boston: South End Press, 1990).

By Mika NijhawanThe zero-sum game of gendered labor means a worker is never merely a worker. Workers bring all the expectations regarding their gender, race, religion, etc, to their workplace, whether that be an office or a factory floor. They are expected to perform their identity: individuals working on an oil rig must be strong, while a prostitute must be sensuous.5 Women are performing gender every day, but this performance takes on new meanings in markets across the globe. In Threads, sociologist Jane Collins points to U.S. corporate executives moving their industrial plants abroad as they believed women in the Global South have exceptional sewing abilities. Moreover, the women were expected to already have the sewing skills they would need for their jobs.6 Managers of the plants also believed they could pay these workers less since they were women–their wages were “supplemental” to the family income as women are not viewed as breadwinners. As anthropologist Anna Tsing frames it, the exploitation that these female garment workers experience in sweatshops is made possible by constructed gender identities. On the one hand, they were given these jobs because of their gender, but this same non-economic factor limited the wages they were paid.7

So, with all this in mind–the context of neo-liberal feminism and late-stage capitalism, and the differences between gendered labor in the Global North and South–what does our labor mean? And how will our generation fit into the broader history of women’s labor movements?

Women deserve freedom, but this freedom will not be found through market integration. Philosopher Elizabeth Anderson argues that the market affords us a specific freedom to choose between a multiplicity of goods without having to ask for permission.8 These market-orientated conceptions of freedom, that you have choice, to choose not only between a variety of goods but a variety of lives and careers, is made possible through the subjugation of those outside the imperial core. Virginia Woolf wrote, “A woman must have money and room of her own if she is to write fiction.”9 And fuck! I do want women to be financially independent and free; I want women to write fiction and poetry, sing songs, and even fill out Excel

5 Anna Tsing, “Supply Chains and the Human Condition,” Rethinking Marxism, 21, no. 2 (2009): 159.

6 Jane Collins. Threads: Gender, Labor, and Power in the Global Apparel Industry. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003.

7 Anna Tsing, “Supply Chains and the Human Condition,” Rethinking Marxism, 21, no. 2 (2009): 159.

8 Elizabeth Anderson, “The Ethical Limitations of the Market,” Economics and Philosophy, 6, no. 2 (October 1990): 179–205.

9 Virginia Woolf, A Room of One’s Own, (London: Penguin, 2004).

the perception of individuals as rational, narrowly selfinterested agents that seek to maximize their personal well-being.

spreadsheets if that is what they want! But it’s hard to do any of these things if your stomach is growling. And yet, I hesitate to accept what the market and market-value system says will liberate me. Work and wealth will never be an appropriate substitute for community and care.

The idea that women’s liberation will come from climbing the corporate ladder is a pretty, liberal lie. While it may be achievable for some, conforming and assimilating to the illusion of capitalist hegemony is a lonely journey leading to nowhere.10 Even more concerning, who are we stepping on to climb this ladder? Our life in the imperial core is unsustainable for the rest of the world. Those with over 1 million USD in wealth make up 0.7% of the world’s population but have a combined wealth of 111.8 trillion USD: 45% of the world’s total.11 This makes me angry, and it should make you angry too.

Iam angry at capitalism, at the patriarchy, at war, at colonization, at labor-capital relationships, at prisons, at the girl in my international relations class who said America is not an empire. I am angry because I love the world, and for me, love and anger run parallel. I love the children in Gaza under rubble and Nex Benedict, the nonbinary, indigenous student killed in Oklahoma. I know I love them because I miss them.

In an interview in the ‘90s, bell hooks said, “Where I stand spiritually is, steadfastly, on a path about love.”12 The path is risky, hard, and hurtful. I do not know the workers who make my clothes or harvest my food, I just know the storefront. They are disguised and hidden away by seemingly banal terms like “outsourcing” and “supply chains.” I am pissed I live in a world consumed by man-made crises: death counts from natural disasters exacerbated by government ineptitude and famines caused by ideas surrounding who is worth saving and who is not. I am pissed I live in a world so enslaved to the gender binary that seeing trans and nonbinary people love themselves, living free of hetero-patriarchal structures, is unthinkable and unacceptable to most. I am academically concerned with issues of women’s liberation, but more than this, I am intellectually concerned. I see no purpose in learning about power structures and economic hegemony in university classrooms if we are not attempting to dismantle them. Intellectual understanding goes further than academic; I am not intellectualizing these concerns away. Instead, I attempt to embody them. Radical awareness of the exploitation of

women across the world informs the actions I take to ensure our liberation.

When we ask questions about the homo economicus and the role of women in economic life, which women are we concerned with? When we discuss the liberation of women, which women are we addressing? Are we concerned with the murdered and indigenous women in the United States? Or, the women on sweatshop factory floors in Sri Lanka? I can acknowledge the difference between myself, a brown, queer woman in the Global North, and other women throughout the world, while still recognizing that the construction of the borders that divide us is inherently violent. It is a privilege to live a life of illusion in the West; that Sheryl Sandberg, and maybe you and I, can choose to enter the circles of power that ensure the domination of the world’s periphery. But empires will not be dismantled by people focusing on their corporate careers and equality will not be achieved through a boardroom of women.

By pretending all women–and all workers–are created equal under capitalism, we perpetuate capitalist fantasies.13 Global capitalism is big, messy, and disjointed. It is expansive and heterogeneous; histories, kinship networks, gender, religion, and citizenship status, are all leveraged to create diverse systems of labor mobilization throughout the world.14 Capitalism cannot be taken a priori as its structures are generated from social relations.15 Thus, if we accept capitalism as a fundamental truth, we have already conceded defeat. While capitalism paints itself as a system maximizing efficiency, in reality, it is precarious. It is unstable and generative, and workers are active agents who navigate and negotiate their roles within these systems.16 From this messiness and chaos, alternative political realities can emerge.

Iwant a fulfilling job and I hope to one day have a family. I hope the sea will rush up to destroy the Western empire, and we will build a new world. In the meantime, I hope we choose to use our labor to create community, form pockets of hope, and care for our neighbors and friends. I am angry, but I know caterpillars become butterflies, so I believe in transformation. I am angry, but I know trees share nutrients through their intertwined roots, so I believe in community.17 Again, and again, we prove to each other that even though love is risky, it is also relentless and unending. Again, and again, we prove to each other transformation is possible: another world is possible.

10 Dr. Ayesha Khan (@wokescientist), “At some point people in the west will realize…” Instagram photo, March 24, 2024. https://www.instagram.com/p/C45zBquO59H/?igsh=MXJzZ3R4Y2w1OTlnZA%3D%3D.

11 Davies, et al. “Estimating the level and distribution of global wealth, 2000–2014.” Review of Income and Wealth, 63 no, 4 (2017): 731–759.

12 Hsu, Hua. “The Revolutionary Writing of bell hooks” New Yorker, December 15, 2021.

13 Society for Cultural Anthropology, “Gens: A Feminist Manifesto for the Study of Capitalism.”

14 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Anna Tsing, “Supply Chains and the Human Condition,” Rethinking Marxism 21, no. 2 (2009): 159.

17 Peter Wohlleben, The Hidden Life of Trees: What They Feel, How They Communicate (Harper Collins Publishing, 2017).

Although the following three poems do not explicitly adhere to the theme, we–the author and editors–like to consider them to have undertones of labor. The labor of love that people who are socialized as women feel in platonic and romantic relationships. We subconsciously internalize the idea that love, in its many forms, should intertwine itself into how we approach the world as opposed to how we interact.

We are taught to say “yes” when we want to say “no” in an attempt to please others. We are taught to smile. Smile more.

We are taught to give and then give more. We are taught to behold ourselves for others.

Overall, we bear the burden of the labor of love more than any creature.

Here, take my mind use me until every hour is blue and every night is white. Look at me, and see what I’m trying to say what words fall short of, what colors haven’t been made. Yet until I’ve been gifted and protected by your heart I’ll confess a million things. One being the strongest day or moment or hour until it closes its eyes in defeat.

I wish I could go back. Instead of helping you help me tear flesh and life from my pulsing carcass, without comprehension nor sympathy.

I wish I could reclaim flashes of lights—red, blue, black and tell myself to run not speak. To refrain from painting you a gorgeous color of love.

I wish I could love myself without dismissing you from my mind. And I wish I could seek comfort in your embrace for longer than a second because I need a lifetime.

Your face encompasses me with no objection nor inquiry.

What if I could look at you for years? when you’re not close, there is not a fiber than can help breathe life into an illustration of you in my mind. An illustration as nearly as beautiful as a hair on your head or a singular cell of your being.

Your eyes hold me in clouds of pink and tears of yellow. They open as curtains, happily pushing apart from each other with no goal in mind except

becoming one within itself—true as windows seep into the light of bliss and the crescent of infatuation

Your lips break apart in a captivating shape to reveal your smile.

Your gorgeous smile that I commit to memory in the reality that soon, too soon, I will not be able to appreciate the careless motions in front of me as a star is in awe of its appreciators and mortals are grateful for the stars they can and can not see. And so with every embrace and every thought of you, my soul tugs at wander-some hues of crimson and rose and tiny flutters of wings sprouting, inching up my throat.

And my animate state of longing for a life we can not place together and a place we should not dare name but only watch whisk us aimlessly in hopes that we collide just for a day just for a dream.

The mountain hears us coming

Bending pools of sky

Gathering head-hanging daffodils

As he parades with a gentle gait

We teeter between ridges and vales

Like a rich vibrato

Until a meadow shows us mercy

At the entrance a carcass sprawls

A red rib bug buffet

And I think of the time I saw a hearse

At the carwash

Getting the ULTIMATE CLEAN PREMIER

For $26.99

It was the outermost layer of a nesting doll

Each innard also slathered in shine

Formaldehyde, wood polish, car wax

My, how death is now so clean

We no longer rot on the prairie

Stink and spoil

So, I putter in the pasture

And do not think to listen for the dinner bell

For if I lie down in the dandelions

And crush my shadow

Tight at high noon

Outstretched in the evening

It will finally know

How big and small at once it feels to be me

Dear readers,

What does success mean to you? Fulfillment? Achievement?

As I come to the end of my time at Tulane, these are the questions I’ve been reflecting on.

I was your typical high-achieving student in high school: I was the president of the Model UN club, I took AP classes, I was involved in local politics, I sang in the choir… Four years since my graduation in 2020, I’ve continually taken stock of what I was like during those years. That story of an ambitious teenager who studied her way to Tulane isn’t the whole narrative, though. During my sophomore year, I had a major health crisis that led me to complete the second semester online. I did school from my bed as I managed crippling migraines, the early stages of an autoimmune disease, and family issues. The next year, I decided to study abroad in Denmark. While it was a wonderful time, the part that I usually omit is that during the spring, I had to come home for medical care that I couldn’t receive abroad. Of course, my senior year was cut short by COVID-19.

However, none of that stopped me from leaving my small hometown in Pennsylvania for college.

My freshman year was fairly unremarkable in the grand scheme of things. I became a WTUL apprentice, a Newcomb scholar, and a class representative. I was happy and excited for the future. Sophomore year, I started to do even more. I took on responsibility with fervor because, in my mind, it was what I was supposed to do. I was diagnosed with ADHD and started medication for it, and I–again–was happy and content. Looking back two years on, I wish I was still that version of myself.

Junior year was a different story. The cracks in my ambition started to become apparent. The fall of 2022, I struggled with a great deal of personal turmoil and I kept telling myself to push through, because I was experiencing anguish to the greatest degree I had so far in my short life. The thing no one tells you about your worst experiences, however, is that they’re bad because of a lack of comparison. That fall, I stopped participating in nearly everything I had once been a part of. I even considered taking a leave from school, but I told myself that it would get better.

It didn’t. The thing no one prepares you for in college is that life continues on. One bad thing happening doesn’t prevent more personal tragedy. One of the lessons I have learned from these experiences is that sometimes, you can’t push through. Rather, radically accepting your circumstances is the best way to move forward and cope. This was a lesson that I’ve been learning over a number of years now, and it’s shifted the way I’ve looked at my time in college. I am not the person I thought I would be freshman year, and that’s okay.

My time in Newcomb, while not always perfect or easy, has taught me innumerable lessons in female friendship, selfadvocacy, and humility. My time at WTUL granted me organizational skills and taught me how to be a truly collaborative leader. TUCP taught me how to compromise and look at the big picture. No matter how I end college, I learned lessons from all of the people and organizations that I have spent time with here. In the end, although I’m ending college in a way that a past me would have perhaps been disappointed in, I know just a few things. My wisdom to impart is this:

1. The goalposts are forever moving. Success doesn’t always come as planned, and holding yourself to the standard of someone in ideal circumstances does nothing to make you feel better.

2. Being alive in and of itself is fulfilling. Surviving despite the odds is a gift.

3. The greatest achievement is happiness in spite of everything you have been dealt.

Thank you,

Liv Tanaka-Kekai, Class of 2024

Liv ( ’24) - Co-Editor-in-Chief and Production Manager

Liv Tanaka-Kekai is a senior from St. Paul, Minnesota majoring in Linguistics with a minor in Music. Upon graduating, she plans on taking a gap year, exploring her hometown, and studying for the LSAT. At Tulane, she has been involved in various things like digital history internships and the radio station WTUL. In her free time, she assists in teaching ESL to both youth and adults, spending time with her cat (Chuck), and cooking.

Mika ( ’25) - Co-Editor-in-Chief and Creative Director

Mika Nijhawan is a junior from Boulder, Colorado, majoring in Economics. She is currently spending the year abroad at the London School of Economics (LSE). At Tulane, she is on the Executive Board of various organizations, including the Indian Association and Women in Politics; while in London, she has been spending her time teaching debate at a local primary school, planning events with the LSE DJ Society, and exploring the music and art scene. You can find her on LinkedIn (linkedin.com/in/mika-nijhawan/) or sitting outside reading The New Yorker.

Ella ( ’26) - Co-Editor-in-Chief and Content Director

Ella Jeffries is a sophomore from Seattle, Washington, majoring in Political Science with minors in English and Economics. In her free time, she enjoys writing (particularly poetry), dancing, and going on Audubon walks. In addition to working on NOSTRA, Ella is the fundraising chair for Club Ace, a hip-hop dance group, a member of Phi Alpha Delta Pre-Law Fraternity, and a TIDES peer mentor. Outside of Tulane, she has pursued her interest in local politics by interning in campaign fundraising for elected officials in Washington State.

A special thanks to Newcomb Institute, Dr. Aidan Smith, and Rebecca Gipson for all their support in

H. Sophie Ne wcom

Memorial College

H. Sophie Ne wcom

Memorial College