Homesteader

Your Guide to Rugged Outdoor Lifestyles

Introduction to Homesteader magazine

Hi! I’m Karli (left) and I am an animal lover, equestrian and outdoor enthusiast. I love hiking with my dogs, paddle boarding and traveling. I also have 3 horses and compete in a variety of events but still enjoy a relaxing trail ride.

I’m Rachael, (right) I’m a homesteader, a business owner, a mother of two toddlers, a wife, and now a magazine content editor. I enjoy foraging, herbal medicine, fishing and I love drinking tea. Cottage-core, grandma hobbies and garden life describes me best!

Homesteader is created by locals, for locals and focused on outdoor lifestyles that are popular in New England. In this magazine we focus on local farming, gardening, preserving & natural remedies, recipes sustainable living, and explorations of the outdoors. We thought we’d share our passions as we know there are many others in New England who share the same interests. We hope you enjoy and learn something new reading our magazine.

Homesteader

~ Your Guide to Rugged Outdoor Lifestyles ~

President and Publisher

Jordan Brechenser jbrechenser@reformer.com

Content Editor

R achael Morin rachaelmorin5078@gmail.com

Copy Editor

Gen Louise M angiaratti gmangiaratti@reformer.com

Sales Executive

K arli Knapp kknapp@reformer.com

Sales Manager Lylah Wright lwright@reformer.com

Digital Marketing Manager Ahmad Yassir ayassir@benningtonbanner.com

Homesteader Magazine is a publication of

70 Landmark Dr., Brattleboro, VT vtnewsmedia.com

Cover photo submitted by:

Dutton Berry Farm, Farmstand & Greenhouse

Tomatoes locally grown and available at Dutton Berry Farmstand & Greenhouse. Locations include: 2083 Depot Street, Manchester, VT; 407 VT-30, Newfane, VT & 308 Marlboro Road, Brattleboro, VT. See their ad on page 19.

Bears, beets, ‘Battlestar Galactica’

By Rachael Morin

Composting methods and how to choose

By

Rachael Morin

Children’s book creates future mushroom foragers

By Chris Mays

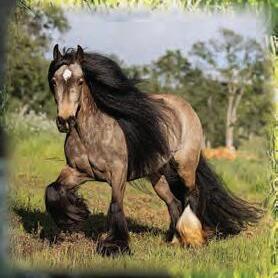

Do you love horses?

Equine Affaire is the event for you

By Allison A. Rehnborg

What qualifies as a homestead? By

Rachael Morin

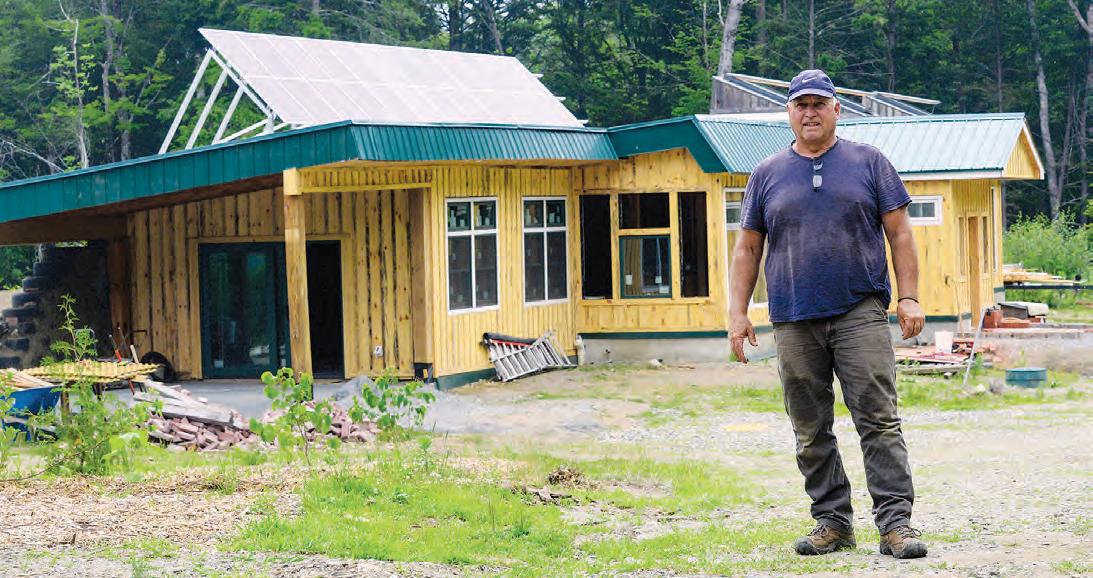

Earthship: Vermont’s entirely off-grid home will not run out of water, doesn’t pay electric bills and stays warm year-round

By

Alexander Belogour

12 22 14 18 25 28 30

Invasives - what can you do about them?

By Henry Homeyer

Vehicles for the homesteader By

Alexander Belogour

By Rachael Morin

Prescribed fire part of school curriculum By Bob

Audette

Sporting dogs and foxtails

By

Rachael Morin

Sign up for our free newsletter to stay informed on all things Homesteader by visiting newenglandhomesteader.com

Bears, beets, ‘Battlestar Galactica’

By Rachael Morin Homesteader Magazine

If you’ve seen the show “The Office,’’ you are well aware of how Dwight Schrute is always talking about how to escape unscathed from a bear attack, how fond he is of the above title-mentioned action series, and how he somehow manages being a beet farmer despite working a 40-hour work week.

TV series pranking scenes aside, it can be of encouragement to fans and nonfans alike that Schrute, in all his quirky glory, had it absolutely right to be interested in these root vegetables. One can find both welcome respite from a day at the office and unparalleled nourishment in a designated area of your humble backyard garden.

Not only does working soil in your hands reconnect you to our Mother Earth’s naturally occuring electric charge — a healthful therapeutic practice called “grounding” or “earthing” — but it produces these amazing little rainbow-colored edible roots if you know the steps to growing your own.

HOW DO I GROW BEETS?

Waiting for spring is actually the hardest part. “I’m always thinking one step ahead, like a carpenter that makes stairs,” says Schrute’s colleague Andy Bernard.

Beets are incredibly easy to grow. One of the first things in my garden, usually as the soil just begins to thaw and warm in the sun, they are directly sown at half-inch depth. For New England, that’s usually mid-March to early April.

HOW DO I KNOW WHICH ONES TO PULL?

“That’s a ridiculous question,” Schrute tells frenemy Jim Halpert.

The tiny reddish purple stems make them easy to tell apart. A best practice is to sow in rows, so that as they grow, you can tell which little seedlings are intentional versus volunteer weeds. Once they get to be about 1.5 to 2 inches high, thin them out a bit, so you can ensure space enough to grow the beautiful root that will adorn your table.

Other than being absolutely striking in highly pigmented color when cross-sectioned, they can be used for a number of ailments, for dye-

ing easter eggs, and reducing stress and anxiety. Let’s get into the layman terms of what makes them good for you (in moderation.)

Beets, “Why are you the way that you are?” (Michael Scott)

Here are some good things beets contain:

1. High in fiber that feeds the healthy bacteria in your gut and assists your colon in getting rid of stored up toxins that naturally happen as we go about our daily diets.

2. Uridine, a substance which helps maintain normal dopamine levels (a happy chemical) and helps regulate brain health.

3. Nitrates: Through a chain reaction, your body changes nitrates into nitric oxide, which helps with blood flow and blood pressure. Beet juice may boost stamina to help you exercise longer, as well as improve blood flow and help to lower blood pressure, some research shows.

4. Antioxidants: Beets contain a powerful antioxidant (a phytonutrient called betalain) that may be able to help your body fight off the conditions that cause inflammation. This means that it also prevents hair loss and reduces skin damage.

BEETS, Page 8

Roasted beet and goat cheese salad

A summertime favorite to start your meal off right Ingredients:

• 4-5 medium beets, tops trimmed and scrubbed

• 3 tablespoons olive oil

• 1/2 small red onion, thinly sliced vertically

• 2-3 sprigs of rosemary

• 1 bulb of garlic

• 1/2 cup coarsely chopped walnuts, toasted if desired

• 1/2 cup crumbled goat cheese

• salt and pepper to taste

Note: When selecting your ingredients from the market, make sure you get good and hearty beet greens. We’re going to show you another recipe to use for those greens on the next page.

1. Clean beets & remove leaves (put aside for the next recipe).

2. Place cleaned beets in a foil wrap with olive oil, garlic cloves, salt and pepper (add a few sprigs of rosemary for a great flavor and aroma).

3. Roast beets at 400 degrees on a baking sheet for 45 minutes, or until fork tender.

4. Roast walnuts in 400-degree oven until toasted, about 10-15 minutes.

5. Allow to fully cool down, peel, slice into bite-sized pieces.

6. Add roasted and chopped walnuts, roasted garlic cloves, fresh-squeezed lemon juice, salt and pepper (toss lightly).

7. Top with crumbled goat cheese & thinly sliced raw red onion.

8. Put in the fridge to chill.

9. Serve as a starter or a refreshing side.

RACHAEL MORIN — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Beet leaves sprout through the soil, reaching for the sun.

RECIPE & PHOTOS SUBMITTED BY JESSICA BRECHENSER

Sauteed beet leaves with pancetta

A savory side that will steal the show

Ingredients:

• 2 shallots, chopped (substitute red onion if desired)

• beet leaves and stems, washed, chopped big

• 1/2 pound pancetta diced into 1/2-inch pieces (bacon will work too, just cut bacon bigger, about 1 inch)

• 2 tsp apple cider vinegar

• grilled bread of choice (ciabatta or baguette work best)

• salt and pepper to taste

1. Preheat grill or get griddle heating for bread.

2. Dice pancetta and start in a nice hot pan.

3. Add shallots to the pan with pork belly, sauté for 3-5 min on medium/high heat (no need to drain the rich fat or add any additional butter or oil).

4. Put your bread on the grill now.

5. Add minced garlic until aromatic, about 1 minute.

6. Add beet leaves and stems. Cook until just wilted. Add salt and pepper to taste.

7. Add 2 teaspoons of apple cider vinegar. Cook for 1-2 minutes and serve over with grilled bread of your choice (baguette in photo).

RECIPE & PHOTOS SUBMITTED BY JESSICA BRECHENSER

WANT YOUR RECIPE FEATURED?

Go to newenglandhomesteader.com to submit the recipe and photos of you and your loved ones making delicious food!

From greens to root, fresh beets are a fantastic dish to star at your next dinner.

Beets

from page 7

Once harvested, you can store them in a cool, dry place. I like to use an old wooden apple crate, with a cloth liner, filled with fine sand. Root vegetables keep very long this way, so you can put your harvested carrots and turnips in there too. If storing in the basement, just make sure you run a dehumidifier. If you need more insight on what area of your home is best suited, you could give “Bob Vance,

Vance Refrigeration,” a call. So go sow your beets, and while you watch them grow in anticipation for the good health ahead, let us all be thankful that we don’t have one more thing drawing the bears to the backyard, or do we? Maybe you’ll see that the beets do, in fact, eat the bears.

Eat a beet and wait three hours, its effects start to happen that quickly: “To give you a reference point, … somewhere between a snake and a mongoose. And a panther,” so says Schrute.

JORDAN BRECHENSER — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Composting methods and how to choose

By Kia Cating

Homesteader Correspondent

I’ll be the first to admit I had always found the topic of composting to be a bit overwhelming, especially as a beginner gardener. Sure, I understood the basic principles of utilizing waste to create a nutrient-rich soil amendment, but when it came down to deciding how much time and effort to dedicate to the process, I was stumped. In friends’ and neighbors’ gardens, I’d seen everything from large, steaming heaps to elaborate, foul-smelling concoctions.

For those of you who may be in a similar position to me, good compost consists

of four essential ingredients: greens, browns, water and oxygen. The “greens” refer to nitrogen-rich organic material such as vegetable and fruit scraps, coffee grounds, grass clippings, and manure. The “browns,” or carbon-rich organic material, include fallen leaves, straw, woody materials and cardboard. Combine it all in the right proportions with enough moisture and oxygen, and voila! You’ve got yourself some fine fertilizer. When it was time to start composting for myself, I asked my friends for advice and did my best to sift through countless articles online detailing various composting methods. As I

began to better understand the processes behind composting, I slowly narrowed my search for the “best” method based on my own specific needs. Because choosing the right composting method can be a daunting task, let’s look into just a few of them:

Passive composting: As the name might suggest, this is the easiest way to get started with composting. Simply collect your greens and browns, place them in a pile or bin, and let nature do its thing. This method doesn’t require much turning or aeration, which is a plus for folks with busy schedules. The downside? Your heap will require at least a

year, sometimes two, before you have usable compost.

Active composting: This method requires a little bit more work and consistency than passive composting, but will yield usable compost much faster. Active, or hot, composting entails turning over your compost pile or bin at least once a week in the summer months. Consistent aeration accelerates decomposition and leads to a hotter compost pile. The higher temperature of your pile will help kill pathogens, bug larvae and pesky weed seeds.

Vermicomposting: aka, worm composting! This method uses worms to break down organic matter into

RACHAEL MORIN — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Passive composting at Hawks Hollow Homestead, a two-bin method to alternate years and allow swine manure to cool down for raised bed use.

nutrient-dense fertilizer. This makes for a great indoor option if limited space and cold weather are factors. This method does require that you pay more attention to moisture control. You also have to avoid composting certain items that aren’t good for worms.

Bokashi composting: This is another great indoor method that utilizes fermentation to break down organic waste. It gives you the ability to compost a wider variety of organic materials, including meat, dairy and citrus, which are usually not recommended for traditional composting. Bokashi does require specific microorganisms and more regular maintenance than a heap or bin, but it is quick — within a matter of weeks, you can have usable compost.

Happy composting from one beginner to another!

Layers: pig manure, leaves, straw, coffee grounds, tree debris and green kitchen food scraps that are not used as chicken treats. No citrus, meat or dairy used.

PHOTOS BY RACHAEL MORIN — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Children’s book creates future mushroom foragers

By Chris Mays Homesteader Magazine

“Mason Goes Mushrooming,” a new children’s book showcasing mushrooms for beginner foragers, brings readers through four woodland adventures with the main character and his dog Buddy in Vermont.

Melany Kahn’s book is inspired by foraging with her family and Hilltop Montessori School workshops she has lead. The author described herself as “a second-generation forager,” as she learned from her late parents, well-revered painters Wolf Kahn, who died in March 2020, and Emily Mason, who died in 2019.

“When I was growing up, my parents took me on fantastic treasure hunts for delicious wild mushrooms,” she writes in a message to future foragers in the book. “They taught me which mushrooms we could safely eat, and which ones were inedible and could lead to a stomach ache, or might even be poisonous.”

Her mother would tell her, “When in doubt, throw it out,” and, “Always check with us.”

A pop-party for what would have been Wolf’s 95th birthday and Kahn’s book launch is happening 5 to 6 p.m. Tuesday at the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center.

Kahn said the book is about her son and being in the woods.

“My children also love to forage in the woods,” she writes. “Mushroom hunting is a wonderful way to connect to nature. You can pick mushrooms to examine, smell, touch, or make spore art.”

During an interview/foraging session on Hilltop Montessori’s outdoor campus, Kahn pointed out how mushrooms can be used for “amazing Thanksgiving decoration tables.”

“You can pick up a whole log of them and make your whole Thanksgiving arrangement around what you can find in the woods,” she said. “And children, of course, love that.”

Kahn said many mushrooms can be eaten but they’re not “choice,” or capable of giving one “a

Melany Kahn talks about the different mushrooms that could be locally found in the woods. Kahn wrote a children’s mushrooms, called “Mason Goes Mushrooming.”

PHOTOS BY KRISTOPHER RADDER — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

culinary moment.” On the walk, she picked up a type that taste like shrimp and put them in a bag to cook up later.

“The first thing that you always want to do when you pick a mushroom is look underneath it,” she said, picking one up and showing a spongy texture in its pores. “I like to say that nothing on a mushroom is an accident. So everything that you see is a characteristic.”

Foragers develop what Kahn calls “mushroom eyes.” They start seeing mushrooms all over the woods, she said. Groups on Facebook and online can help with identification.

The book includes four recipes. Kahn recommends cooking every mushroom including those from the store.

“Mushrooms are filled

with all sorts of microbes and things,” she said. “Just hit them with a little heat. Get rid of that stuff.”

Her book focuses on morel, chanterelle, black trumpets and lobster mushrooms. They have identifying characteristics that are very unique, she said.

“No other mushroom looks like the black trumpet,” she said.

Ellen Korbonski, who illustrated the book and lives in Harlem, attended New York University with Kahn.

“Mason Goes Mushrooming” is each one’s first book.

Early in the COVID-19 pandemic, Kahn invited Korbonski to Vermont for Christmas.

“I came in one morning and she was drawing a bird with a watercolor brush,” Kahn recounted. “And I was

like, ‘Wow, you can just do that.’ It was beautiful.”

Kahn told Korbonski about her idea for a children’s book, and they began working on it together. Green Writers Press in

Brattleboro is publishing the book and Springfield Printing Corp. in Vermont printed it.

More information can be found at masongoesmushrooming.com.

KRISTOPHER RADDER — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Do you love horses? Equine Affaire is the event for you

By Allison A. Rehnborg Equine Affaire Marketing Coordinator

A New England mainstay for more than 25 years, this incredible four-day fair is guaranteed to elevate the equestrian experience for equine enthusiasts of all ages. Bring the whole family and find out why Equine Affaire is North America’s premier equine exposition and equestrian gathering!

This event will take place Nov. 7 to 10, at the Eastern States Exposition in West Springfield, Mass.

Whether you’re new to the horse world or a lifelong fan, there’s something for everyone to explore at Equine Affaire. From educational clinics to exciting competitions to engaging activities, you could spend a whole day — or four — celebrating your love of horses with family and friends.

Enjoy hundreds of educational clinics, seminars and demonstrations about all aspects of horses, from riding and handling to behavior, care, feeding and more. In between clinics, visit the Breed Pavilion and the Horse & Farm Exhibits, where you can meet-and-greet with dozens of beautiful horses of a variety of breeds, types and colors, including horses for sale and adoption.

Little ones will love the Equine Fundamentals Forum, a special area featuring educational exhibits, handson activities, and kids’ crafts. With more than 300 vendors spread out across multiple buildings, the trade show is the perfect place to get a jumpstart on your Christmas shopping lists. You’ll also enjoy picking out yummy treats from an amazing array of fair foods available in the food court.

Crown your day at Equine Affaire by attending a spectacular nighttime performance:

“Fantasia,” a musical celebration of the horse! Sponsored by Equine Medical & Surgical Associates, “Fantasia” is a stunning theatrical showcase of talented riders, gorgeous horses and fabulous music.

This year’s event will feature acts that will inspire your dreams, bring tears to your eyes, and remind you of all the reasons you fell in love with horses. With just three evening performances, happening Nov. 7 to 9, get your tickets early before they sell out.

General admission tickets

and “Fantasia” tickets are on sale now at equineaffaire. com. Tickets are $18/day for adults or $55 for a fourday pass. Children’s tickets are available for $10/day for children ages 7 to 10. Children 6 and under are admitted for free. Tickets for “Fantasia” range from $16 to $27. Please note that the Eastern States Exposition charges for parking.

Find out more about Equine Affaire by visiting equineaffaire.com.

PHOTOS

FeaturedClinicians:

GuyMcLean (QuietwayHorsemanship) sponsoredbyCustomEquineNutrition

ChrisIrwin (HorseThink,Mind YourHorse)

TikMaynard (Eventing & Behavioral Training)

RyanRose (General Training &Trail)

NorthAmerica’s Premier EquineExposition & EquestrianGathering

NOV.7–10,2024

W.SPRINGFIELD,MA

EasternStatesExposition

• AnUnparalleledEducationalProgram.

• The LargestHorse-Related TradeShowinNorthAmerica.

• TheMarketplaceConsignmentShop

• TheFantasia (sponsoredbyEquineMedicalandSurgicalAssociates) Equine Affaire’s signaturemusicalcelebrationofthehorseonThursday, Fridayand Saturdaynights.

• Breed Pavilion,Horse & FarmExhibits,HorsesforSaleandAdoption Affaire

• NEW! BreedBonanza —A uniqueundersaddleclassshowcasingthebestfeatures ofhorsesfromallbreeds!

• Drive A Draft —Learntoground-drive a drafthorseinthisfascinatingexperience withgentlegiants!

• EquineFundamentalsForumand YouthActivities Educationalpresentations, exhibits,andactivitiesfornewridersandhorseowners,young & old.

• NEW! StagecoachRides Enjoy a horse-drawnstagecoachridearoundthe fairgroundsandseeEquine Affairelike neverbefore

• The VersatileHorse & RiderCompetition (sponsoredbyChewy) —A fast-paced timedandjudgedracethroughanobstaclecoursewith$5,500atstake!

• GreatEquestrianFitnessChallenge Showoffyourmusclesinoneofourfun barnyardOlympicevents!

• Andmuch,muchmore!

LaurenSammis (Dressage)

TraciBrooks (Hunter/Jumper)

BarbraSchulte (Cutting,SportsPsychology)

BethBaumert (Dressage)

MarcieQuist (Driving)

DanielStewart (Jumping,SportsPsychology)

BenLongwell (Vaqueroand Ranch)

IvyStarnes (EasyGaitedHorses)

MaryMillerJordan (Mustangs,Liberty)

Solange (StableRiding)

CelisseBarrett (MountedArchery)

Sam&KellieRettinger (DraftHorses)

MiniDovesEquestrianDrillTeam (MiniHorses)

RenegadeDrillTeam (Drill Teams)

RebeccaPlatz (MiniObstacleCourses)

CopperHillVaultingTeam (Vaulting)

Additionalpresenterstobe announcedsoon!

What qualifies as a homestead?

By Rachael Morin Homesteader Magazine

It’s all the hype lately on almost everyone’s social media feeds: swanky and manicured raised beds, moon gates, shire-esque rolling hills dotted with sheep and livestock guardian dogs.

There’s a magical thing happening and this generation is returning to the ways of our grandparents because — shocker — they had it absolutely nailed down.

Simplicity at its best, everyone is turning to homesteading. There are infinite benefits to growing your own food, protein sources and medicine, but the reality is that you don’t have to make it look like something out of The Hobbit.

Cottagecore aesthetic is dreamy, but it’s not the only way to achieve a self-sustaining lifestyle. It is possible to just do the best with whatever is on hand. You can take the things lying around, and with enough ingenuity and creativity,

you can spend little to nothing on the lifestyle that will provide.

There’s incentive to that way of life in Vermont, and something that not everyone is even aware of. If you live permanently on your property year-round, or at the very least, 182 days of the year, you qualify as a homestead in the little Green Mountain State. It does not matter if you are at the end of a picturesque dirt road or on a main interstate.

Depending on your education system and the amount of students therein, your property taxes are going to be less than/different than if someone were to be renting the very same property to tenants. You do not have to have a single thing growing in a garden, or a jar of canned-yourself peaches on the shelf.

Visit tax.vermont.gov to see if your property qualifies as a homestead.

PHOTOS BY RACHAEL MORIN & KARLI KNAPP - HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Henry Homeyer | Notes from the Garden:

Invasives - what can you do about them?

By Henry Homeyer Homesteader Correspondent

I’m lucky. Unlike many houses built in the 1800s or early 1900s, mine had no invasive plants when I bought it in 1970, probably because it was built as a Creamery, or butter factory. Decorative plants were not needed. Most older houses are plagued with plants brought from Asia or Europe by well-meaning people who did not know that once imported, those handsome plants might not have any predators that could keep them under control. Most of our native insects will not eat foreign plants.

Plants including Japanese knotweed, Asian bittersweet, goutweed, purple loosestrife, yellow pond iris and multiflora roses have thrived in New England – and all are nearly impossible to get rid of, once established. Unfortunately, I now have four of the six mentioned above. But no Japanese knotweed or bittersweet, thankfully (they are two of the worst).

Multiflora roses just showed up on my property last year, probably by birds that dropped seeds. It is easy to see roses growing in your woods or fields, or even in a garden bed and pass it by as “just a rose.” But the roses we love don’t just appear.

The multiflora rose was introduced from Asia in the 1860s as a vigorous ornamental rose and as a source of rootstock for grafted roses. In the 1930s it was widely introduced as erosion control and alongside highways – a mature planting is so dense

it can prevent cars from going over median strips. But the birds liked the rose hips – their seed pods – and it escaped cultivation.

So, what am I doing to eliminate it on my property?

I am digging it out. Most effective for one or two year old plants, I am using a curved, single-tine hand tool called the CobraHead (www.Cobrahead.com) to carefully excavate the roots until I can lift the plant out.

First, I dress appropriately: jeans, long-sleeved shirt, a hat with a brim, and heavy winter leather work gloves. This culprit wants to hurt anyone trying to uproot it. I cut off the branches, just leaving a foot or so to grab onto when pulling it out. Then I loosen the soil and pull weeds around it. The roots radiate outward from the stem like spokes on a bike. I loosen each root and tug gently when they are small enough to remove.

I do not burn brush anymore because of global warming, and don’t want any errant seeds to escape, so I cut up the branches and brought them to our town recycling center. I put them into the trash, going to the landfill, along with the roots. It took me about an hour to remove and cut up one plant – and I have several. But this plant can grow 10 feet or more in a year and strangle trees or shrubs.

I’ve read that just cutting back the stems to ground level will stimulate the roots to send up new shoots everywhere, causing a bigger problem. There is no easy answer.

PHOTOS SUBMITTED BY HENRY HOMEYER

Buckthorn Multi-flora rose hips

Invasive plants are always difficult to remove – usually a scrap of root can generate a new plant – or several.

Buckthorn is another invasive that is common along streams and at the edge of fields. Like multiflora rose, cutting it down stimulates the roots to send up new shoots. The best way to eliminate it is to starve the roots: Take a pruning saw and cut through the bark and the green layer of cambium beneath that. Go all the way around the trunk, then repeat six inches above the first cut, and repeat. This will not kill the tree until the third year, but this slow death will not stimulate the roots to grow. Best done in winter or fall after leaf drop.

Since buckthorn are often multi-stemmed, it can be difficult to use that method. Do it up high enough that you can get your saw in between the stems. But I’ve done it, and it works.

Purple loosestrife is bloom-

ing now in swamps and wet places – it is gorgeous, but outcompetes many of our native wetland plants that feed pollinators and other animals. Like many invasives, it produces huge numbers of seeds, and these seeds don’t all germinate the next springmany stay dormant for years. I’ve read that multiflora rose seeds can stay viable up to 20 years – a good reason to clear plants out when young.

My approach to purple loosestrife is to dig out new, young plants. I recognize them by their square stem, the leaf shape and the color of the stem, which is often reddish. But for big established plants, I just use a curved harvest knife to slice off the foliage once or more each summer. This prevents seed production, and reduces plant energy.

As regular reader of this column know, I only use organic techniques in the garden. This means no chem-

icals, including herbicides. From what I have read, most herbicides will not kill the invasives mentioned in this article. They will set them back considerably, depending on the age of the plant and the dose of the chemical. But learning to recognize all the invasives is best. And if one

appears on your landscape, get rid of it immediately! And remember, persistence is important

Henry Homeyer is the author of 4 gardening books and lectures at garden clubs and libraries. He lives in Cornish, N.H. His email is henry.homeyer@comcast.net.

PHOTO SUBMITTED BY HENRY HOMEYER

Purple loosestrife

Trout in the everchanging rivers and streams

By Rachael Morin Homesteader Magazine

A year since the flooding of 2023, the destruction has been on everyone’s minds.

So many households were misplaced, and in the days following, community-minded people came together to rebuild, reopen and get things back into some semblance of working order.

We’re the lucky ones. We have neighbors to help us, and I, for one, can’t help but think about how as the year has gone on, we’ve picked back up the lives that we put on hold to help others.

Thinking about all of those animals who have to search for new feeding grounds, breeding waters and shelter, trout kept popping into my head. I thought I’d ask the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Service about this potentially annual disaster.

Shawn Good, fisheries scientist of the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department, took the time to talk about native trout species, the river’s changing landscape and the significance of stocking fish.

Q: What’s the healthiest population of native trout species?

A: There are only two trout species native to Vermont: 1. lake trout, and 2. brook trout.

Brook Trout are the most widely distributed across the state and populations are doing very well in watersheds that are intact and healthy.

Q: How does the river’s changing landscape impact where you are stocking? What’s it doing to native populations?

A: Quality aquatic habitat is crucial to our landscape’s ability to support wild trout populations. Changing land uses and degradation through developing, road and culvert construction, etc., can harm stream environments and trout habitat, making them unsuitable for wild trout.

So, a lot of our work focuses on habitat protections and restoration when possible.

Q: For Vermont as a whole, why do we stock fish and what’s significant about it being done during springtime?

A: This is a common question we get often. There are a number of reasons we stock fish, but the primary one is to provide fishing opportunities. Stocking decisions (species, numbers, locations) are made based on fish population and habitat assessment data collected by department fisheries biologists.

Most trout stocking done in streams and rivers focuses on areas where habitat has been degraded and cannot support wild reproduction to sustain trout populations. The vast majority of streams and rivers, and trout populations across the state are not stocked — they are healthy and wild.

We have a Trout Management Plan that guides our stocking activities. To answer the second part, ‘Why do we stock in the spring?’ Spring is a natural time when anglers start looking to spend more time outdoors after a long winter. Traditionally, in Vermont, spring trout season

sees a large bump in fishing activity, so this is when we want to ensure the stocked stream sections have fish.

It’s also when conditions are most conducive to trout stocking. Water levels and

stream flows are good, and water temperatures are low, so this ensures good trout survival so the fish can be caught by anglers.

Q: Are hatchery/fishery stock sterile or part of the breeding population? How does a fish become sterile?

A: In recent years, we have switched over to stocking triploid (sterile) trout. These fish cannot reproduce, which limits their impacts to any wild trout in a stream if there’s overlap in wild population and stocking sites. Sterilization of hatchery trout happens after the fertilization period in the hatchery. Sterile trout are called ‘triploids’ because they have an extra set of chromosomes, which is what makes them unable to reproduce. During normal development, the third chromosome is discarded from the developing egg, but in the hatchery, eggs can be put under pressure or heat at a specific time in the egg’s development, forcing the egg to retain the extra chromosome.

Q: What’s the average lifespan of a stocked fish?

A: The lifespan of hatchery trout isn’t expected to be any different than most wild trout (3 to 4 years for brook trout, 5 to 6 for brown trout, 3 to 5 for rainbow trout) if they were in quality habitat. However, stocked trout tend not to live as long because they either 1. get caught and are harvested soon after stocking, which is the purpose of stocking them as I mentioned earlier, or 2. they can’t live in the environment they are stocked into because water temperatures get too hot or habitat is degraded.

Q: Are stocked fish similar to their native cousins in where they reside as it relates to river topographical/ temperature preference?

A: Yes, stocked fish that don’t get caught and harvested can sometimes ‘hold over’ if the stream provides the water temperatures, habitat and food resources necessary for survival. They generally revert to the same behaviors as wild trout.

PHOTOS SUBMITTED BY VERMONT FISH & WILDLIFE

Vermont Fish & Wildlife stocks brook, brown and rainbow trout into water all around the state to provide public fishing opportunities. Check out the department’s fish stocking page to find a stocked stream near you.

EARTHSHIP:

Vermont’s entirely off-grid home will not run out of water, doesn’t pay electric bills and stays warm year-round

By Alexander Belogour Homesteader Magazine

The power could be out on John Grant’s road in Westminster, but he’d never notice; his house, too, will never even run out of water. That’s because, for the past five years, Grant has been constructing a type of entirely self-sustaining off-grid home known as an Earthship.

Grant used to work in the timber industry, but he is now fully devoted to transforming his 12-acres into any homesteader’s dream property with seemingly endless solar power, rain-collecting water systems and efficient heating and cooling abilities that don’t require a traditional fireplace or AC unit.

Just about a year ago, Grant was in the process of erecting a dozen 455-watt bifacial solar panels, which he bought at a scratch and

dent sale for around 10 cents a watt; the usual cost of just one panel is $450. Since he last made headlines for his Earthship, he hosted a community informational event at his property, which drew in over 60 interested locals — way more than he had initially expected.

Grant said he takes pride in teaching others the six principles of Earthships: heating, cooling, water, waste, electricity and food — all six of which are combined, considered and incorporated in some way into his home.

In Grant’s home, all the electricity he uses comes directly from his solar panels. He doesn’t even have a contract with Green Mountain Power.

The front facade of his home faces south and consists of several large windows. It’s important that these windows face south so that they can capture the greatest possible amount of

solar energy, which heats the home in the winter and grows his food in his indoor garden.

“In the wintertime, when the sun is at its lowest apex, the sun will reach through the southern-facing greenhouse glass windows and heat up the soil behind the concrete wall at the back of the house. The sun charges the building up. It’s a solar thermal battery,” said Grant.

Grant’s house was built by first leveling a sloping hill on the property and using the excess soil to fill a retaining wall bounded by over 700 tires, which will later be sealed and buried in selfmade Vermont adobe: a natural concoction of hay, water and clay dirt.

The solid mass of earth retained by the tires is positioned at the north side of the house and reaches all the way up to the roof of the building. Underneath the solid mound are three cisterns

that can collect up to 4,500 gallons of rainwater runoff from the metal roof and custom-fabricated 6-inch gutter. On top of his roof sit the 12 solar panels.

Grant said he wasn’t going for any particular decor style or theme, but that he just wanted to have fun building and make his house about function.

“It’s about our activism, which is the sense of climate and the reality of trying to educate people about alternatives to housing, which is so important in our day and age,” said Grant.

A recurring theme throughout the property is thriftiness and resourcefulness. Grant initially logged his property but is now building his house and 3,000-squarefoot barn, which he finished out of the wood he harvested. He also recently finished a heavy rustic-style door with oak from his property. Now, Grant has started the

process of reforesting some parts of his property with Catalpa, Cedar, Dogwood and other trees.

A main highlight of his property is his water collection system, which lies under his concrete floor and foundation.

Water from Grant’s roof goes directly into three 1,500-gallon cisterns. When he needs water, his solar system will pump water through a water organization module filter to be used in the sink or shower. Grant said all of his black water gets flushed out into his septic field, but he does something especially unique with his gray water — water that does not contain human waste.

“The gray water, which is the water I use to take a shower, brush my teeth and wash my clothes, is actually all interconnected underneath my brick patio and dumped out in the top of my indoor garden, which is coated in a pond liner,” said Grant.

His indoor garden system mimics a natural aquifer and holds water in place for his plants to use. Grant plans to plant lemon, banana and avocado trees among household herbs and spices year-round. He also has a chicken coop outside and might consider buying some land-clearing goats to keep down bramble.

Some issues Grant has faced in his home include humidity. His dirt berm at the back north end of his house traps in the water, which, by hydraulic force, seeps back up through his concrete floor. He is currently in the process of fixing the issue by spreading pond liner over his berm to minimize the amount of roof runoff it can hold.

Buried underneath the northern dirt berm, six long culverts, through convection, naturally draw in and cool the warmer outdoor air. Grant says these tubes bring in some unwanted outdoor humidity. However, the Earthship is heavily insulated, with 7 inches of insulation on the ceiling alone to keep warm air and cold air in during winter and summer, respectively, and Grant said the tubes may have been a flaw of overengineering from being initially developed in the southwest where he studied the design of the home. His house otherwise naturally maintains a temperature of 70 degrees Fahrenheit year round.

Grant said he has learned by making mistakes, and also through lots of YouTube videos. He has taught himself how to do woodworking and carpentry for his kitchen cabinets, and for future library bookshelves and barn door room dividers.

Earthship

His house is also equipped with all the modern appliances of a normal house, such as a fridge, water pumps, freezer, stove and washing machine — all powered by Grant’s solar panels.

Based on his current power consumption and lifestyle, Grant estimates that he could live in his house for three days without needing sunlight to power his solar panels, but he looks forward to an efficient solar energy storage system being invented in the future.

“I did all of this by myself; this whole project was done by myself, minus cranes and an excavator,” noted Grant.

Some might find Grant’s project to be a daunting one, especially with all the imaginable complexities of building a home from the ground up, but Grant does not think so.

“I was an arborist by training; my whole life and career was working with trees. I didn’t know anything about solar or what I was doing here. I used YouTube. Literally. I’m now amazed that people will pay Green Mountain Power; all of it is so simple, black wire here, green there and red here, even a dummy like me could do it.

“I definitely recommend not having a full-time job. It’s a lot of work and some expense. I’ve saved a lot of money by doing a lot of this myself. But I mean, that’s not realistic for everybody. Go slow and be resourceful,” said Grant.

Grant pointed to a small scrap pile, which he said was all his waste from five years of effort. He then pointed to a heaping pile of bricks he said he got for $150 and all of his live-edge siding, which cost him $600. Overall, Grant said he wants to complete both his house and barn

John Grant of Westminster West talks about the Earthship home that he is building on his property. Earthships are designed to behave as passive solar earth shelters made of both natural and upcycled materials such as soil-packed tires.

for just under $250,000. His house is 2,500 square feet, and he says he managed to build it for $65 per sq. ft.

“In terms of homesteading,” says Grant, “I don’t even know when the grid goes down. I don’t know when

Fromsmallimprovementstobigprojects,you wantyourhometobeaspecialplaceforfamily andfriendstoenjoy. We’reheretohelp!

Weoffersitevisits,estimates,take-offs,free deliveryandthebestsolutionsforyournext project.Withdecadesofexperienceandreal-world knowledge,wecanofferadviceandalevelof servicefewotherscanmatch.

434Route100,Wilmington (802)464-3022

551Route30,Newfane (802)365-4333

people have outages. Water is not an issue for me. I have more water than we can ever imagine.”

Grant plans to be done with his Earthship in November, just in time to invite his family over for Thanksgiving dinner.

KRISTOPHER RADDER — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Vehicles for the homesteader

All things powersports at Central Vermont Motorcycles

By Alexander Belogour Homesteader Magazine

Vermonters and out-ofstaters alike share one thing in common — the love for nature, and many take to four wheels to work in or experience the outdoors.

The busiest times of the season for four-wheeling and outdoor power sports are spring — right when the snow melts and outdoorsmen arise from winter slumber to tend to property maintenance — and right before fall, when hunters prepare to trek into the wilderness with a new machine or complimenting accessory.

For staff at Central Vermont Motorcycles in Rutland, these two times of the

year are when the shop is most active, and Eric Bearor, the general manager, says he loves helping both Vermonters and out-of-staters find their perfect vehicle.

Bearor, who manages the business, one of the largest snowmobiling, ATV and UTV dealerships in the state, says homesteaders, hunters, fishers and property managers all share a similar desire to add power to their profession. Many come into the shop to do just that.

When customers walk into the store, at 360 West St. in Rutland, Bearor says most choose from two of the three main vehicle segments, those being utility vehicles, sport vehicles and the in-between option of sport-utility vehicles.

— SPONSORED CONTENT — VEHICLES, Page

UTILITY VEHICLES

By far, most people come to Central Vermont Motorcycles to shop for their selection of utility vehicles. Two of the most popular vehicle sellers are Can-Am & Polaris.

“A utility machine which is geared towards farming and property maintenance,” says Bearor, “they are machines to use around your house and property. They usually have a box on the rear of the vehicle to carry anything from firewood, tools and all other kinds of stuff there.”

Bearor says that most people will end up going with a utility machine because it serves many versatile purposes. From hunting to fishing and property management, a utility machine can handle a plethora of tasks.

One of the most common tasks utility machines find themselves enlisted in is hunting.

“Again, utility machines have the bigger box in the rear. You can put the deer in the back. You can throw your fishing gear in there and you can also get to wherever you need to go to do your outdoor activities with just a little bit more functionality. I’d say that probably 75% of our customers go towards the utility side of things, especially in our area, Vermont.”

One of the aspects of utility machines that makes them so user-friendly is their adaptability to any circumstance, as they can be easily customized.

PHOTO SUBMITTED BY CENTRAL VERMONT MOTORCYLES

2025 Polaris Ranger

PHOTO SUBMITTED BY CENTRAL VERMONT MOTORCYLES 2024 Polaris RZR XP

Typically, any one machine comes into the shop as a stock-issued purchase, but with a little careful planning, customers can access any utility vehicle to perform specialized tasks.

“Typically, a machine comes pretty basic, as kind of an open cab-type unit. So, the first thing a customer would do is put a roof and windshield on it. But then after that, they typically add a winch package, so they can pull trees and logs, or, you know, anything out with a winch on the front.”

For hunters, Bearor says gun racks are essential; loggers prefer chainsaw holders, and almost all riders enjoy having a large storage box on the back of their machines. Customers can also

request different tool holders of all sorts — most opt in for rakes, shovels and just about any other mount one could think of.

Convenience, too, is a big selling point for utility vehicles.

“Most of this stuff is easy to put on and taken off very quickly. They make it very versatile to swap out. So if you’re doing trail maintenance one day, you can throw on the accessories that you need for trail maintenance, and then if you’re going hunting the next day, you can swap it all out, and you can put your gun racks in there, and whatever else you may need for hunting on there,” says Bearor.

Bearor says second-homeowners make up the bulk of his utility vehicle clientele.

“They’ll buy pieces of property, and then once they

own the property, realize how much time it takes to maintain large amounts of property. So then, they end up buying a side-by-side so they can get to the part of their property that they need to tend to very quickly.”

Bearor says Vermonters also make up a good portion of customers but that they typically buy vehicles on the lower end of the price range.

Bearor says prices for utility vehicles can start at $12,000 and go all the way up to $55,000 with all the fancy electronic bells and whistles — screens, stereo and even GPS.

“It’s not needed,” says Bearor. “Vermonters who are skilled in their profession will save on those additions.”

SPORT VEHICLES

Sport vehicles are, just as the name suggests, designed for sport, and in the world of

four-wheeling, sport typically means the ability to go fast.

“Sport machines are made for trail riding. So, there is a very small box on the rear to carry. The box can fit a cooler and maybe a couple of small tools, but it is more geared towards trail riding. There’s a little bit better suspension when compared to utility vehicles, so it can soak up bumps and is really made to go fast,” says Bearor.

Bearor says Vermonters buy most of his sports vehicles, the mix being 70% in-state sales to 30% out-ofstate sales.

He says typically, out-ofstaters will buy sports vehicles in their home states and then use out-of-state trail systems.

“We don’t have a really good trail system here for the sport machines. There are trails that you can ride,

but you basically have to take them out of state to New Hampshire, Maine to really be able to get full use out of a sport side by side,” Bearor added.

SPORT-UTILITY VEHICLES

In between the two choices lies a third option: the sport-utility vehicle.

“The sport-utility segment is between a utility and a sport machine,” notes Bearor. “It has a small amount of suspension under the cab. You can also get a small box that’s in between the sport and utility sizes, so you can use it for tools and do a little bit of work, too, but you can also play-ride with the machine as well; that’s really what the machine is meant for. It does a little bit of both other segments but just doesn’t do it superiorly well in either or segment, but it’s made to do both.”

HOMESTEADER

Sport utility vehicles make up a smaller fraction of sales when compared with plain sport and utility vehicles.

SNOWMOBILES, ELECTRIC VEHICLES

When snow touches the ground in late November or December, Bearor says that a feverish rush tends to flood into the veins of snow sports enthusiasts, called “snow fever.”

“You have a very small window to ride your snowmobile, so you have to be ready when it starts to snow. These customers who are snowmobilers get very excited about snow. They’re very passionate about riding snowmobiles.”

Also entering the market, albeit at steep price points, are new electric four-wheelers. Central Vermont Motorcycles has sold a few electric side-by-sides to out-of-state second-homeowners, but

$55,000 make the vehicles challenging to sell.

Bearor thinks the vehicles have good future appli-

when prices start to come down with the possibility of rebates or other incentives.

— SPONSORED CONTENT —

PHOTO SUBMITTED BY CENTRAL VERMONT MOTORCYLES 2024 Can-Am Defender X-MR

Learning by burning: Prescribed fire part of school curriculum

By Bob Audette Homesteader Magazine

With temperatures approaching 90 degrees, four blue-hatted firefighting students with hoes and rakes tried to stay ahead of a fire in a field near Chesterfield Elementary School.

“They are the future of the fire service,” said Chesterfield Fire Chief Rick Cooper, who was on hand with several local volunteer firefighters and fire trucks to support the students from the Cheshire Career Center in Keene.

The four students, juniors and seniors, are all interested in firefighting, either as volunteers in their hometown or as professionals.

“It’s hard work, but it’s fun. And hot,” said Cody Hatt, a junior from Swanzey, during a break in training on April 14. “Practice makes perfect.”

Hatt, who is volunteer in his hometown, said if he decides to become a firefighter, he wants to stay local and maybe work in Keene.

“My plan is to go to Southern Maine Community College for the fire science program and hopefully become a full-time firefighter,” said Seamus Howard, of Keene, who’s father served as Keene’s fire chief for eight years.

Aidon Doucet, of Rindge, said it’s awesome to have the experience of working on a real fire while being supported by firefighters from around the region.

Students from Keene, N.H., High School Cheshire

controlled wildfire at the Chesterfield School as part of the

PHOTOS BY KRISTOPHER RADDER — HOMESTEADER MAGAZINE

Career Center Fire Science Class had a

students’ Basic Forest Fire Training.

“I was thinking about being a volunteer firefighter or going into the military,” he said.

Doucet plans to take the emergency medical services program at Franklin Pierce University following graduation from Conant High School in Jaffrey.

The year-long fire science program through the Cheshire Career Center is presented in collaboration with the New Hampshire Fire Academy.

Firefighter I certification allows students to join local volunteer fire departments and is one of the certifications necessary for employment for those working toward a firefighting career.

The course covers many different aspects of firefighting, including protective equipment, forcible entry, ladders, search and rescue, ventilation, fire suppression and hazardous materials training.

“Today they’re learning how to deploy hose lines and learning how to do scratch lines,” said David Jones, who assisted career center instructor Graham Gritchell with the hands-on training. “They’re going to learn how to do mop up, both wet and dry mop up, and learn safety procedures.”

“They’ve been working on their Firefighter One certification throughout the year,” said Gritchell. “Today is specifically for their New Hampshire basic forest fire module.”

Before the end of the school year, the students will also take an EMT course through the career center, he said.

Burning the field is not just about training, said Chesterfield Principal Sharon D’Eon, but also about the school’s curriculum related to the environment.

She said carefully managed burns help recycle nutrients, reduce invasives, and maintain field habitat for wildlife.

“Students in grades K through 8 will all participate in at least one lesson with their classroom teachers to learn about the science behind controlled burns, their value in preventing megafires, and the historical use of controlled burning by Native Americans, including the Abenaki in our area,” states information from the school. “They will then get to observe the changes before and after the burn.”

In 2017, Chesterfield School purchased a 23-acre lot adjacent to its facility and established an Outdoor Education Committee.

Learning about indigenous peoples both past and present, is also part of the curriculum. Seventh and eighth grade Social Studies teacher, Jay VanStechelman, led his seventh graders in the construction of a wigwam at the edge of the field this past fall, trying as much as possible to follow Native building practices.

Rich Holschuh, tribal monitor for the Elnu Abenaki, and Melody Walker Mackin, member of the Vermont Commission on Native American Affairs, and member of the Elnu Abenaki Tribe, have also been supporting the Chesterfield School’s study of indigenous peoples of the region.

Holschuh, who was on hand for the burn, said burning fields has a long history with indigenous peoples.

“This is an indigenous land management practice,” he said. “When the first settlers showed up here, the land around the Retreat Meadows in Brattleboro was all cleared already due to the fire practices. It’s important to know this isn’t something new. ”

Sporting dogs and foxtails

By Rachael Morin Homesteader Magazine

Sticky burs, impalement, bucks in rut, bears … Some of the most accomplished hunting dogs in the sporting group have undergone many hours of training, trials and tribulations. They learn when to react in action to a loud explosion of the gun, when to veer right, or left, when to retrieve. The dog can follow every command, every cue, and still not be prepared for the subjects in question.

Avoiding unsuspecting porcupines in the brush or woods is challenging enough, but what about that hidden enemy known as foxtails? It’s quite a job for a responsible handler to be on the lookout for Alopecurus (the scientific name means “fox tail”), Bromus madritensis (foxtail brome), Hordeum jubatum (foxtail barley) or Setaria (foxtail millets) after every hunt or woodsy excursion.

The grasslike weed is mostly found in the western half of the U.S., but

with changing climate and varying conditions, it can grow throughout the northeast as well.

These grasses are identified by the awns, or tiny hairlike structures, that hold each seed to the stalk. These awns can burrow through a dog’s skin just like a porcupine quill, into a lung, through the nose canal and into the brain, all of which can be fatal, but hopefully the owner’s diligence and awareness prevents such a fate.

Foxtail types include:

1. Bristlegrass

2. Yellow or green foxtail

3. Canada wild rye

4. Giant foxtail

5. Cheatgrass (aka bromus tectorum, drooping brome or downy brome)

6. June grass

7. Creeping foxtail

8. Timothy grass

9. Awns/grass awns/ grass seed

According to West River Valley Vet services: “Grassawn diseases and ailments are a real problem for hunt-

ing canines, but any dog can come in contact with these plants when running or walking through tall grass because they are quite widespread throughout North America, especially from May through December. Dogs with long ears and coats may be more likely to pick up the barbs.”

Prevention methods include keeping the dog’s fur

short during the fall, or sticking to a paved or clearly worn trail. When checking for ticks at the end of your walk or hunt, pick any and all plant debris off of the dog. Better safe than sorry in the morning.

Keep your family couch potatoes and working dogs safe this season: Keep a close eye for plants like this.