Adaptive Experiments for Policy Choice

Phone Calls for Home Reading in Kenya

Bruno Esposito Anja SautmannPolicy Research Working Paper

Policy Research Working Paper

Adaptive sampling in experiments with multiple waves can improve learning for “policy choice problems” where the goal is to select the optimal intervention or treatment among several options. This paper uses a real-world policy choice problem to demonstrate the advantages of adaptive sampling and propose solutions to common issues in apply ing the method. The application is a test of six formats for automated calls to parents in Kenya that encourage reading with children at home. The adaptive ‘exploration sampling’

algorithm is used to efficiently identify the call with the highest rate of engagement. Simulations show that adaptive sampling increased the posterior probability of the chosen arm being optimal from 86 to 93 percent and more than halved the posterior expected regret. The paper discusses a range of implementation aspects, including how to decide about research design parameters such as the number of experimental waves.

This paper is a product of the Development Research Group, Development Economics. It is part of a larger effort by the World Bank to provide open access to its research and make a contribution to development policy discussions around the world. Policy Research Working Papers are also posted on the Web at http://www.worldbank.org/prwp. The authors may be contacted at asautmann@worldbank.org.

The Policy Research Working Paper Series disseminates the findings of work in progress to encourage the exchange of ideas about development issues. An objective of the series is to get the findings out quickly, even if the presentations are less than fully polished. The papers carry the names of the authors and should be cited accordingly. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/World Bank and its affiliated organizations, or those of the Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent.

Segura,AdamMcCloskey,andKellyW.Zhangwereextremelygenerousinsharingtheirexpertise.WethankKathleenBeegle, DanielBj¨orkegren,EstherGehrke,AndrewFoster,MaximilianKasy,DavidMcKenzie,RobertPless,andseminarparticipants attheWorldBankandRochesterUniversityforhelpfulcommentsandfeedback.Thefindings,interpretations,andconclusions

itsaffiliatedorganizations,orthoseoftheExecutiveDirectorsoftheWorldBankorthegovernmentstheyrepresent.Allerrors areours.

Theuseofexperimentsinresearchoneconomicdevelopmentandpolicyrepresentsoneofthebiggestmethodologicalinnovationsineconomicsinthelastfewdecades.Forresearchthattestspolicyinterventionsand programs,thehopehasbeenthatrigorousexperimentscanleadtobetterpolicydecisions.Inthiscontext, thelearninggoalofapolicymakersuchasagovernmentorNGOmaybecharacterizedasfollows:they wouldliketoimproveacertainoutcome,sayineducationorhealth,andarelookingtoidentifythebest (leastexpensive,mosteffective)policytoaffectthisoutcome.Wecallthisa“policychoiceproblem”for short.

Randomizedcontroltrials(RCT)astheyarefoundineconomicsandrelatedfieldsaretypicallyaimedat identifyingcausaltreatmenteffectsandestimatingtheseeffectsaspreciselyaspossible,anddesignchoices likeequal-sizedtreatmentgroupsandre-randomizationorstratificationsupportthisgoal.Butthisapproach toexperimentaldesignisnotideallysuitedtoinformapolicychoiceproblem.Toseewhy,notethatsample sizesthatdeliverthepowertostatisticallydistinguishtheeffectsizesinmultipletreatmentarmsfromzero (andeachother)quicklygrowlarge.Yetfortheobjectiveofchoosingandimplementingonlyoneofthe testedpolicies,precisetreatmenteffectestimatesforlow-performingoptionsarenotactuallyneeded;expost, someofthesampleassignedtothesearmscouldhavebeenputtobetterusetodistinguishthetreatment effectsinthehighest-performingarms.Thisisparticularlydetrimentalifthesampleissmallorthereare budgetandtimeconstraintsthatpreventprolongedexperimentation.

Whentheexperimentcanbecarriedoutintwoormorewaves,theresearchdesignforpolicychoicecan, inmanycases,beimprovedbyusingadaptivesampling.Theobjectiveinthepolicychoiceproblemis tomaximizetheaverageoutcomeattheendoftheexperiment,orequivalently,minimizeexpectedpolicy regret,thatis,theexpectedlossfromselectingasuboptimalarm.Choosingthearmwiththehighest outcomeafterrepeatedexperimentationisaspecialcaseofthemulti-armedbanditproblemwithapure “exploration”motive,butno“exploitation”motive(Bubecketal.,2009;Audibertetal.,2010).Efficient learningmeansadaptingtheassignmentofexperimentalunitstotreatmentarmsbasedonwhatwaslearned inearlierwaves.1 Thebestadaptivelearningstrategyforpolicychoicetendstoassignalargershareof thesampletohigher-performingarms.Thishelpstodistinguishthesearmsfromeachotherwhilespending lesseffortonlow-performingarms.Inpractice,researchersusesamplingalgorithmsthatapproximatethe optimalstrategytoreducecomputationalburden.

Thispaperputsadaptivesamplingforpolicychoicetothetestbyapplyingittoareal-worldpolicychoice

1Thisistrueformanydifferentlearningobjectives,includingbutnotlimitedtopolicychoice.Itholdsalsoforlearning goalsthatusuallymotivatestandardRCTs,suchasefficienthypothesistesting:itistypicallynotoptimaltorandomlyassign equalsamplesharestoalltreatmentarmsinlaterwaves,seee.g.Tabord-Meehan(2018).

problemineducationtechnology.Thegoalisthreefold:addressingconceptualandpracticalchallengesin implementingadaptiveexperimentsinpolicysettings,studyingperformanceofanadaptiveresearchdesign inashorttimehorizonwhereasymptoticperformanceguaranteesmaynotapply,and,lastbutnotleast, informingtheactualpolicychoiceproblemathand.

Theexampleweuseisanexperimentonusingphonecallswithinteractivevoiceresponse(IVR)technology todeliverregularshortreadingexercisesdirectlytoparentsinKenya.Thecallsareintendedtoencourage parentstoreadwiththeirchildrenathome,apracticeknowntoimprovelanguageacquisitionandfluency (Mayeretal.,2019;Yorketal.,2019;Knaueretal.,2020).TheimplementerwasNewGlobe,anorganization thatbothsupportspublicschoolsandoperatesitsowncommunityschoolsinseveralcountries,includingthe BridgeKenyaprimaryschoolsinoursample.FacedwithmanyoptionsforIVRcallandexercisedesigns, NewGlobewaslookingtodecidewhichcallformat(ifany)theyshouldrollouttoallparents.

WeusetheIVRexperimenttodiscussindetailhowtoapproachdesigningandconductinganadaptive experimentforpolicychoice–fromestimationapproaches,tothealgorithmused,toresearchdesigndecisions, forexampleaboutsamplingandsamplingsize.Inourexample,wetestedsixdifferentIVRcalloptionsduring thethirdtermofthe2020schoolyear.Theexperimentwasdesignedtoidentifythecallformatwiththe highestlevelofengagement,measuredasthenumberofIVRcallsinwhichtherespondentstartedthereading exercises,andtotestwhetherIVRcallscanincreasereadingfluency.Thecallscross-combinetwodelivery formatsfortheexercises–parent-ledvs.IVR-ledreading–withthreedifferentwaysofmatchingexercise contentstothechild’sreadinglevel,motivatedbyevidencethattargetedinstructioncanimproveoutcomes especiallyinthetailsofthedistribution(Banerjeeetal.,2007;Muralidharanetal.,2019;Dossetal.,2019).

Inordertoefficientlyidentifythearmwithhighestcallengagement,theexperimentusesaversionofthe explorationsamplingalgorithmproposedbyKasyandSautmann(2021a)toassignexperimentalunitsto treatmentarms.ExplorationsamplingisaBayesianbanditalgorithmthatwasshowntoperformwellin bothrealandsimulatedexperimentsforpolicychoiceandsharesattractiveasymptoticefficiencyproperties forbest-armidentificationofasetofsimilaralgorithms(Russo,2020;Qinetal.,2017;Shangetal.,2020; KasyandSautmann,2021b).Toourknowledge,therearetodateonlythreepolicychoiceexperimentsthat haveusedit:anapplicationintheoriginalpaper,atestofanSMS-basedinformationcampaigninIndiato reducethespreadofCovid-19(Bahetyetal.,2021),andatrialoncontraceptiveuptakeinCameroonthat isongoingatthetimeofwriting(Atheyetal.,2021).InsteadofaBernoullioutcomewithaBetapriorasin theoriginalpaper(andmanymulti-armedbanditsettings),weuseahierarchicalbinomialmodeltoobtain assignmentsharesandparameterestimates.

TheIVRexperimenthasonlytwoexperimentalwavesandtheoutcomedistributionismorecomplexthan assumedintheoreticaltreatmentsofBayesianbest-armalgorithms.Wearethereforeparticularlyinterested

howadaptivesamplinginfluencestreatmentassignment,performance,andestimationresults.Wefindthat afterjustonewave,thereissufficientlearningsothatadaptivesamplingleadstoasubstantialshiftinthe assignmentshares:basedonthedifferentcallsuccessratesineacharmafterwave1,weobtainedsample allocationsharesforwave2thatvariedbetween0%and39%.Afterwave2,weestimatea93%probability thatthebestcalldesignforengagementusesparent-ledreadingexercisesanddeliversthesameintermediatelevelexercisestoallstudents.Inthisarm,parentsengage–meaning,theystartthereadingexercises–with 8.40%probabilitypercall,comparedto3.93%intheleastsuccessfularm.Thearmwithsecondhighest engagement(7.43%)hasonlya5%probabilityofbeingoptimal.Expressingtheexpectedpolicyregretin termsofaverageengagementprobability,theselectedtreatmentarmhasanestimated0.02%expectedloss frompotentiallymakingasuboptimalchoice,comparedto1.27%-4.49%fortheotherarms.

Eventhoughtheexperimenttargetedcallengagement,wealsoestimatethetreatmenteffectsonoral readingfluency(ORF),usingexamscorescollectedbytheimplementer.Althoughthedataisnoisy,wefind thatthearmwiththehighestlevelofengagementleadstoestimatedincreasesinORFof1.68correctwords perminute,equivalentto0.065standarddeviationsofthebaselinedata,withacredibleintervalbetween 0.13and3.21.Theprecisionofthisestimateispartlyduetothelargesampleassignedtothebestarm.

TheresultsoftheIVRexperimentspeaktoanimportantpolicyquestion:whethertherearelow-cost, automatedmethodsofincreasingtheprobabilitythatparentsreadwiththeiryoungchildren,andwhat theirbestdesignmightbe.EspeciallyduringtheCovid-19pandemic,itbecameclearthatthereisan unfilledneedforsustainedlearningathomeandreachingchildreninfamilieswithlimitededucationaland technologicalresources.Personalcallshavebeenshowntobehighlyeffective(Angristetal.,2020b),butmay requiresignificantofresources.Theexperimentshowsthatmass-deployedIVRcallscanincreaseparental involvementinthechild’sschoolingbutthatthecalldesignmatterssignificantlyforuptake.

Beyondthesefindings,themaincontributionsofthispaperareanevaluationofthemeritsofusing adaptivesamplingforpolicychoice,andadetailedguidetoimplementation.2 Inparticular,weusesimulation approachestoexaminetheperformanceoftheexperimentandunderstandtheimpactofdifferentdesign choices.Inafirstexercise,wecompare‘expost’theexplorationsamplingdesignwithanalternativedesign withequal-sized(stratified)treatmentarms,akintoa“standard”RCT,usingsimulatedsamplesdrawnfrom theexperimentalobservations.Thisshowsthatadaptiveassignmentinonlyonewaveachievedmeaningful reductionsinuncertainty–fromonaverage86%probabilitythatthechosenarmisoptimalintheRCTto 93%probabilitywithexplorationsampling–andreducedposteriorexpectedpolicyregretbymorethanhalf from0.05percentto0.02percentengagementprobability.

Thenexttwoexercisescarryout‘exante’simulationsbasedontheoutcomemodelinordertodetermine 2Thiscomplementstheexcellentpractitioner’sguideonadaptiveexperimentsbyHadadetal.(2021).

thegainsfrom(a)conductingtwoexperimentalwavesinsteadofone(non-adaptive)wavewiththefull sample,and(b)addingasecondwaveafterhavingobservedtheoutcomesofthefirst.Theseareexamples ofsimulationsaresearchermightconducttodeterminetheresearchdesign,akintopowercalculations.In case(a),thepredictedreductionsinexpectedregretseemplausibleforspecificparametervector,buttheflat priordistributionsofthetreatmenteffectparametersdonotprovideagoodbasisforsimulatingthegains fromadaptivity;researchersmayinsteadchoosetofocusonspecificparametervalues,notleasttoreduce computationalburden(akintopowercalculationswhereaminimumdetectableeffectsizeisimposed).In case(b),wherethewave-1posteriorscanbeusedtosimulateparameterdraws,“agnostic”simulationsdo better,buttheyappeartostillsomewhatunder-predictthegains.

Aswegoalong,wediscussmanydetailsofimplementationandexperimentaldesign,suchasformulating andvalidatingtheBayesianmodelsfortreatmenteffectestimation,calculatingtheexpectedposteriorpolicy regretofeacharm,andwritingapre-analysisplan.Weaddressquestionssuchaswhenanadaptiveexperimentispossibleandwhenitmaybemostvaluable,andapproachestocorrectingestimatedtreatmenteffects andconfidenceintervalsforsamplingbiasandthe“winner’scurse”thataffectsthetreatmenteffectestimate ofthebestarm(e.g.MelfiandPage,2000;Andrewsetal.,2021).Wealsospendsometimediscussingthe trade-offsthatwereinvolvedinchoosingthetargetedoutcome.

Theconstraintsonthisexperimentarerepresentativeofthedecisioncontextsinwhichpolicymakers workday-to-day.InNewGlobe’ssituation,withalimitedbudgetandonlyoneschooltermavailabletotest IVR,manyorganizationsmightdecideagainstanexperimententirely—butourtrialshowsthatadaptive samplingmethodscanenablerigorouslearningevenwhentheparametersofexperimentaldesignareseverely constrained.Thesolutionsweproposecanhelpinformfutureadaptiveexperimentsforpolicychoice,in EdTechaswellasmanyothercontexts.

Thenextsectionintroducestheconceptsbehindadaptivesamplingforpolicychoice,showinghowthe samplingalgorithmusedisdeterminedbytheobjectiveoftheexperiment,describingtheexplorationsamplingalgorithm,anddiscussingtheuseofBayesianestimation.Italsolaysoutsomeconsiderationsfor choosingparametersoftheresearchdesignsuchasthenumberofwaves.Section3discussesthepolicy background,interventions,andexperimentaldesignoftheIVRexperiment,includingthechoiceoftargeted outcome,highlightinglessonsforadaptiveexperimentsingeneral.Section4discussesthedataanddetails themodelsusedforestimation,includinghowtoderivetheprobabilityoptimalandtheexpectedpolicy regret,quantitiesusedintheexplorationsamplingalgorithm.Section5presentstreatmenteffectestimates forparentalengagement,showstheassignmentsharesbasedontheseestimates,anddiscussestheimpact onreadingfluency.Finally,section6picksupthequestionofresearchdesignagain.Intheconcretecontext oftheIVRexperiment,wefirstshowhowtheadaptiveandanon-adaptivedesigncompare‘expost’in

simulatedsamplesfromtheexperimentaldata,andthendemonstratehow‘exante’simulationscanbeused todecide,forexample,onthenumberofexperimentalwaves.Section7concludeswithashortdiscussion.

Thissectiongivesanoverviewovertheuseofadaptivesamplingforpolicychoiceandtheexplorationsampling algorithmproposedbyKasyandSautmann(2021a).Westartwiththe“basicingredients”foranadaptive experiment:theobjective,analgorithmthatbuildsonthedatafromeachwavetoadaptivelyallocateunits totreatmentarms,theestimationapproach,andconstraintsthatdeterminewhetheranadaptiveexperiment isfeasible.ThecorrespondingfeaturesoftheIVRexperimentaredescribedindetailinsections3and4.

Thissectionalsodiscussesthegainsfromadaptivevs.non-adaptivesamplingoraddingadaptivewaves, andhowthesegainscanbecalculatedinsimulationstochoosethenumberofexperimentalwaves.Wereturn tothisinsection6,buildingonthedatacollectedinKenyaandtheestimationresultsinsection5.Tobegin with,however,weassumethatthereare t =1,...,T exogenouslygivenconsecutivesampledraws(waves)of size Nt availablefortesting.

Objective. Inthecanonicalpolicychoiceproblem,thereare K> 2policyoptions–ortreatmentarms–labeled k =1, 2,...,K.Eacharmhasunobserved(stationary)averageoutcome θk,andthepolicymaker wantstoimplementthearmwiththehighestaverageoutcome.Formally,let k(1) =argmaxk θk bethetrue bestarm,and k∗ thearmthatischosen.Wecalltheloss(perunit)fromimplementingasuboptimalarm k thepolicyregret,∆k = θk(1) θk.Expost,thepolicymakerwillselectthearm k∗ thathasthehighest averageoutcome,orlowestpolicyregret,basedontheobserveddata.

Itisassumedthattheoutcomesoftheexperimentalunitsareobservedattheendofeachperiod t.This meanswecanlearnfromwave t andadjusttheallocationofunitstotreatmentarmsinwave t +1,i.e. useadaptivesampling.Inthepolicychoiceproblem,thepolicymaker’swantstoimplementanadaptive samplingstrategythatmaximizeswelfare,thatis,minimizestheexpectedpolicyregretfromthefinalchoice giventhetrue(unobserved)vectorofaverageoutcomes: E[∆k∗ |θ].Adaptivityincreasestheefficiencyof learningforagivenobjectivebyover-samplingsomearmsbasedonwhatwaslearned,attheexpenseof otherarms(andotherobjectives).

Remark:OtherObjectives. Largeliteraturesconsidersamplingforspecificlearninggoals.

Theclassicalmulti-armbanditproblem(MAB)considerstheobjectivetomaximizeaverageoutcomes duringtheongoingexperiment,orequivalentlytominimizein-sampleregret,whichintroducesthewellknownexploration-exploitationtrade-off(e.gLaiandRobbins,1985;BubeckandCesa-Bianchi,2012).The policychoiceproblemofchoosingthearmwiththehighestaverageoutcomecanbeseenasaspecialcase

oftheMABproblem,wheretheexperimenterhasno“exploitation”motive(Bubecketal.,2009;Audibert etal.,2010).Closelyrelatedtothe“pureexploration”problemofpolicychoiceistheproblemof“bestarm identification”(BAI),tothepointthattheyareoftentreatedasinterchangeable.Here,theexperimental designaimstoeitherminimizetheprobabilityofchoosingasub-optimalarmafteragivennumberofwaves (the“fixedbudget”setting),orminimizetheexpectednumberofwavestoachieveagivenlevelofcertainty aboutwhicharmisoptimal(the“fixedconfidence”setting(GarivierandKaufmann,2016);seee.g.Lattimore andSzepesv´ari(2020)foranexcellentandin-depthoverview).

Eveninnon-adaptiveexperiments,commonsamplingtechniquessuchasstratificationandre-randomization aimtomaximizepowertodetectadifferencebetweentreatmentandcontrolgroup(AtheyandImbens, 2017).3 Adaptivestrategiescanfurtherincreasepowerforparticulartests(Robbins,1952).Forexample, Tabord-Meehan(2018)proposesanadaptivestratificationprocedureforatwo-stageexperimentwiththe objectiveofminimizingthevarianceoftheestimatorfortheaveragetreatmenteffect.

ABayesianBanditAlgorithmforPolicyChoice. Althoughtheallocationofexperimentalunitsto armsforagivenexperimentoflength T isafinitedecisionproblem,determiningtheoptimalallocation exactlyiscomputationallyprohibitivelycostly.4 IntheIVRexperimentthisisthecaseevenwithjustone adaptivewave(seealsosimulationsinsection6).Thishasledtothedevelopmentofvariousheuristicsfor treatmentassignment.

TheexplorationsamplingalgorithmusedhereisaBayesianbanditalgorithm:itstartsfromaprior overthemodelparameters–withidenticalpriorsforthe k treatmenteffects–andupdatestheparameter distributionsastheoutcomesofeachwave t areobserved.Theposteriordistributionforthearm-specific θk isusedtocalculatetheposteriorprobabilitythat k isthebestarm, pk t =Prt(k = k(1))andthe(posterior)

expectedpolicyregret Et(∆k).In t +1,thealgorithmassignsexperimentalunitstoarm k withsampling shares

ExplorationsamplingisamodificationofThompsonsampling,whichdirectlyusestheprobabilities pk

minimaxdecisioncriterion.However,Banerjeeetal.(2020)arguethat(some)randomizationimprovestheabilitytoconvince diverseandpotentiallyadversarialaudienceswitharangeofpriors.Theargumentisrelevantforadaptivedesignsaswell: reducingthesamplesizeofsomearmsinfavorofotherarmsislikelytobethewrongdecisionunderatleastsomepriorsabout thetrue

,andthereforeanadaptiveexperimentislessconvincingtoanadversarialaudiencethananon-adaptiveexperiment.

regret(Thompson,1933).ComparedwithThompsonsamplingandotheralgorithmsthattargetin-sample regret,explorationsamplingshiftsmeasurementeffortawayfromthebestarm,increasingexplorationand decreasingexploitation.Thisisbecauseweneedtolearnnotonlyaboutthebestarmbutalsoitsclose competitorsforefficientpolicychoice.Atthesametime,itshiftsmeasurementefforttowardsthehigherperformingarmscomparedtoanexperimentwithuniformassignment(i.e.,equalsamplingshares1/K), becauseinformationaboutthelow-performingarmsisunlikelytoberelevant.

ForthecaseofBernoullidistributedbinaryoutcomeswithaBetaprior,KasyandSautmann(2021a,b) showthatexplorationsamplingbalancesthesamplingallocationinthelimitat T →∞ betweenthesuboptimalarms,yieldingconstrainedoptimalposteriorconvergence(subjecttothesamplingshareofthebest armconvergingtoapre-selectedproportion).IntheBernoullicase,posteriorexpectedregretconvergesat thesameratebecauseregretisboundedby1.SeveralBayesianbest-armalgorithms–appliedtospecific outcomedistributions–havebeenshowntohavethisproperty(Qinetal.,2017;Russo,2020;Shangetal., 2020).5 Eachheuristichasitsownmerits,butexplorationsamplingisappealingforitssimpleformthat doesnotrequireatuningparameter,itsconvenienceforbatchsettings(waveslargerthan1unit),andits motivationbasedonsamplingthebestarmfromtheposteriorfor θ withtherestrictionofneverassigning thesamearmtwiceforincreasedexploration.6 Theexistingtheoreticalperformanceguaranteesapplyonly asymptoticallyandforspecificoutcomedistributions.However,KasyandSautmann(2021a)demonstrate thegoodperformanceofexplorationsamplingforexpectedpolicyregretintheBeta-Bernoullicaseinsimulationsbasedonpre-existingdataandforposteriorconvergenceinanexperimenttestingdifferentenrollment methodsforanagriculturalextensionservice.Wealsousesimulationsinsection6toassessthegainsfrom explorationsamplingoveruniformassignment.

IntheIVRexperiment,theprimaryobjectivewastoidentifythebestarmmeasuredbytheparents’ engagementwiththeIVRcalls.Wethereforeusedexplorationsamplingon6/7thofthesample.Asecondary goalwastounderstandwhethertheIVRcallshaveaneffectonreadingability.Thedesignthereforeincluded a(fixed)controlgroupof1/7thofthesampleforidentifyingthetimetrendinreadingfluencyandestimating treatmenteffects(seesections3and4).Designsthatcombineadaptivetreatmentarmswithacontrolgroup

5Allare“top-two”algorithmsbasedonexpendinggreatermeasurementeffortonthecurrentbesttwoarms,withatuning parameter β determiningtheallocationbetweenthemaswellasthelimitsampleshareofthebestarm.Russofirstproposed threealgorithmsandestablishconstrainedoptimalposteriorconvergenceforafamilyofoutcomedistributions:Top-TwoProbabilitySampling(TTPS),Top-TwoValueSampling(TTVS),andTop-TwoThompsonSampling(TTTS).Top-TwoExpected Improvement(TTEI)byQinetal.(2017)modifiestheexpectedimprovementalgorithmforGaussianoutcomes.Theauthors alsoshowthatthealgorithmisasymptoticallyoptimalinthefixed-confidencesetting,whichrequiresthatthelimitallocation isattainedinfinitetime.Shangetal.(2020)proposeaversioncalledTop-TwoTransportationCost(T3C)thatislesscomputationallydemandingthanTTTSandappliestoalargersetofoutcomedistributionsthanTTEI,andproveoptimalityof bothTTTSandTTEIinthefixedconfidencesettingforGaussianoutcomes.Finally,theyestablishposteriorconvergencefor TTTSforNormalandBernoullidistributedoutcomes.

6Thompsonsamplingisequivalenttotakingsimpledrawsfromtheposteriorwithoutprohibitingrepeatassignments.TTPS andTTVSdeterminetwo“top”candidatearmsineachwaveandrandomlyselectthefirstwithprobability β andthesecond otherwise,makingthempoorlysuitedforbatchallocation.TTEIisspecifictonormallydistributedoutcomes.Exploration samplingisclosesttoTTTSandT3Candwith β =0.5allthreeconvergetothesamelimitallocation.

arealsousedbyBahetyetal.(2021)andAtheyetal.(2021).

Estimation. IntheIVRapplication,wefocusonBayesianestimationtoobtainfinalparameterestimates. InKasyandSautmann(2021a),theoutcomeofeacharm k isBernoullidistributedwithaBetaprior,sothat theposteriorsafter t haveclosedforms.IntheIVRexperiment,wegeneralizetheapproachandestimate Bayesianhierarchicalmodelswithschool-specificeffectsandaBinomialoutcomedistribution(Normalfor readingfluency),describedindetailinsection4.TheBayesianapproachwithupdatingbetweenwavesis internallyconsistent7 andnaturallyproduces pk t thatweneedforexplorationsampling.Bayesianinference isvalidwithadaptivelycollecteddata.

However,usersmaybeinterestedinfrequentistinferenceabouttheparameterestimates.Frequentist estimatesthatdonotaccountforthedatabeinggeneratedbyanexperimentforpolicychoicearesubject topotentialbiases(MelfiandPage,2000;Xuetal.,2013).First,observationsfromanadaptiveexperiment ceasetobeiiddraws–intuitively,adaptivityintroducessamplingbiasbecauserandomfluctuationsinearly observationsinagiventreatmentarm k affecttheweightoftheseobservationsintheoverallsampleassigned to k (bychangingtheassignmentsharesofthisarminfuturewaves).Second,inferenceonthebestarmout ofaset,wheretherankingisbasedonthetreatmenteffectestimates,createsanupwardbiasandinvalidates standardconfidenceintervalsevenwithnon-adaptivesampling(Andrewsetal.,2021).

Inferencefromadaptivelysampleddataisanactivefieldofresearch,withparticularfocusonalgorithms targetingin-sampleregret,whichexacerbateselectionbiasbyquicklyfocusingonhigh-performingarms. Adaptivelyweightedestimatorscancorrectsamplingbiasandproduceasymptoticallynormalestimators (Hadadetal.,2021;Zhangetal.,2021).Andrewsetal.(2021)proposecorrectionsforthe“winner’scurse” whenestimatingtheaverageoutcomeofthehighest-performingarmthatapplytoasymptoticallynormal estimators.Toourknowledge,therearetodatenoapproachesthatcanprovideconfidenceintervalswith correctcoveragefortheoptimalarminanadaptiveexperimentinamodelwithrandomeffectsasweused intheIVRexperiment.However,insection5weestimateafrequentistBinomialmodelforengagementand illustratehowtheestimatesareaffectedwhen(a)applyingtheweightsproposedinZhangetal.(2021)to restoreasymptoticnormalityandthenapplyingthewinner’scursecorrectionbyAndrewsetal.(2021).

Remark:HybridAlgorithms. Giventheproblemswithinferenceinadaptiveprocedureswherelow-performing armsareunder-sampled,recentapplicationshaveusedmodifiedalgorithmsforahybridgoalof(frequentist) estimationaswellasregretminimization.Forexample,the“temperedThompson”algorithminCaria etal.(2020)usesaconvexcombinationofThompsonsharesand1/k equal-sizedshares.Anothercommon

7Inprinciple,updatingtheposteriorfromanyearlierwavewiththedatacollectedafterwardsshouldleadtothesame posterioroutcomedistributionat t,includingre-estimatingthemodelwithallthedatacollectedandtheinitialprior,whichis inpracticethemethodweuse.

modificationistoimposealowerboundonthesamplingshareineacharm(“clipping”,appliede.g.inAthey etal.(2021)withexplorationsampling).Suchmodificationscanbecombinedwithsettingasideasample shareforoneexperimentalarmandinparticularacontrolgroup,seeforexamplethe“control-augmented” ThompsonsamplingalgorithminOffer-Westortetal.(2021).

Animportantdecisionforresearchdesignsinpracticeisthesizeoftheexperimentalsample N .The MABliteratureoftenassumesthatexperimentalunitsarrivethroughanexogenousprocessandcanbeused costlesslyforexperimentation,oftenindefinitely.Inpractice,researchersusingadaptiveexperimentsneed todecidehowtosplitthesampleintowaves,orhowmanywavesoffixedsizetoconduct.Weapproach thesequestionsintwosteps,byfirstdiscussingconstraintsthatdelineatethespaceofpossibleexperimental designs,andthenoutlininghowtoassessalternativeswithintheseconstraints.

ConstraintsonAdaptiveExperimentalDesigns. Theuseofmultiplewavesimposessomeconstraints onthesetofpossibleadaptiveexperimentaldesigns.Weoutlinetheseherebriefly,partlytoillustratewhen adaptivedesignareinpracticefeasible.

Totaltime Dmax available. Duetoexternalconstraints,suchasfundingtimelinesordeadlinesforoperational deliverables,themaximaldurationofanexperimentistypicallylimited.8 Comparablewaves. Mostbanditalgorithmsassumesomeformofstationarity,e.g.thattheobservationsin allwavesrepresentiiddrawsofthepotentialoutcomesinthepopulation.Forefficientlearningacrosswaves, thetreatmenteffectsmustbestationaryandanytimetrendsmustbecommontoallarms.Annualcohorts ofstudentsorbatchesofsurveyparticipantsrecruitedatrandommayfulfilltheseconditions,bute.g.job seekersinaseasonalindustryatdifferenttimesoftheyearlikelydonot.

Lengthofawave d Tocompleteawave,theinterventionmustbeadministeredinfull,outcomechangesin responsetothetreatmentsmusthavemanifested,andpost-interventionoutcomemeasuresmustbecollected beforethestartofthenextwave.Thisdetermineswaveduration d

Together,theseconstraintstypicallyimposealimitonthenumberofwaves T max.Ifthepolicyenvironmentchangesrapidly,dataiscollectedinatime-consumingsurvey,ortheavailabletimedoesnotinclude twocomparableperiods,onlyone“wave”maybepossible, T max =1.Ontheotherhand,ifawavetakes onlyhoursordaysanddataareautomaticallyrecorded,manywavesmaybepossible,e.g. T =10inBahety etal.(2021)or T =17inKasyandSautmann(2021a). Otherconstraintsmaylimite.g.themaximumsamplesizeperwaveorthetotalsample N max.IntheIVR experiment,duetotimeandcomparabilityconstraints,thechoicewaseffectivelyonlybetweenconducting 8Suchalimitisareasontousepolicychoicealgorithmsthatminimizeexpectedregretaftertheexperiment,ratherthanan algorithmthatsimplycontinuesindefinitelyandtargetsin-sampleregret.

oneortwoexperimentalwaves.TheavailablesamplewasthefullpopulationoffirstgradersintheBridge Kenyaschoolsinterm3of2020,seesection3.

ChoosingtheResearchDesign. Evenifconstraintsnarrowdownthedesignspace,theexperimenter maystillneedtodecidewhethertouseadaptivesamplingandchoosesamplesize,wavesize,andnumber ofwavestorun.Anaddedconsiderationisthatevenforagivensamplesize N ,therearesomecoststo conductingtestinginwaves.

Per-waveImplementationCosts. Maintainingtheinfrastructurefordatacollectionandinterventionsforall treatmentarms,includingthehumancapitalcostsofmanagingtheexperiment,addsfixedcosts ct perwave, ontopofanyper-unitcosts ck i (whichmayvarybytreatmentarm). CostofDelay. Eachnewwaveaddsdelayuntilthegainsfromtheexperiment–theaverageestimated treatmenteffectofthebestarm–arerealizedforallpotentialbeneficiaries.

Balancingthesecostsaretheefficiencygainsfromadaptivity.Itiscomputationallyinvolvedtoestimate thesegains,andsotheresearchercantypicallyonlyconsiderasmallnumberofdesigns.Here,webriefly discusstwosituationsthatwillfrequentlyariseinpractice.First,experimentersoftenhaveafixed N availableandhavetodecidewhetherandhowtodividethesampleintowaves.Second,theexperimenter mayneedtodecideattime t whethertorunanadditionalwavein t +1.

Thiscouldbesetupasasimpleoptimizationproblem.Forexample,considerchoosingthenumberof waves T ∈{1,...,T max} forgivensamplesize N ,sothatthewavesizeis Nt = N/T (assumingequalsizedwavesforsimplicity).Wewouldexpectmoreefficientlearningwithmorewavesandmorechancesto adapt,andindeedthesimulationsinKasyandSautmann(2021a)withdatafromthreeexistingexperiments showhowsplittingthesampleinto2,4,and10wavesmonotonicallyshrinkstheexpectedpolicyregret. Inpractice,however,themarginalgainsarelikelydecreasingin T 9 Moreover,thegainsmustbeweighed againstthecost.Theexperimentermightsolve

Thesecondtermpenalizesthecostofincreasing

ofthenumberofbeneficiaries

totheimplementationdelay.

,discountedby

growsandthewavesizeshrinks,itbecomeshardertoimplementthe adaptivealgorithmfaithfully,andtheactualassignmentsharesmaydiffersubstantiallyfromtheexplorationsamplingshares

9Thisisatleastinpartduetoindivisibilityissues.As

t ,especiallyifthesampleisalsostratified(seealsosection5).Withmanytreatmentarms,insmallwavessomearmsmay notbeassignedatall,updatingaboutthesearmswillproceedslowlyintermsof t,andtheassignmentsharesmayremainfar fromoptimalforalongperiodoftime.

t N

Inthesecondsituationwedefined,waveshavefixedsize Nt andtheexperimenterneedstodecidewhen toendtheexperiment.Inadditiontotheper-waveanddelaycostsgivenby ct and δT +1,increasing T incurs qk t Nt timestheperunitcost ck i foreachexperimentalarm.10 Inexchange,theexperimenterobserves additional Nt unitsineachwave t

Ineachcaseabove,theresearcherneedstoestimate E(θk∗ )asafunctionoftheresearchdesign.Since closedformsarenottypicallyavailable,theseprojectedgainsfromadaptivityhavetobeobtainedfrom simulations.Thisrequiressimulatingnotonlyexperimentaloutcomesunderdifferentrandomsampledraws, butalsothedifferentsamplingpathsthatarisefromadaptivity.Theexperimenteristypicallyrestrictedto comparingonlyafewhypothetical θ andasmallnumberofpossibleresearchdesigns.Weillustratesuch simulationsinthecontextoftheIVRexperimentinsection6.

OurapplicationforadaptivesamplingforpolicychoiceisanEdTechinterventionthatusesinteractive voicecallingaimedatencouragingparentstoreadwiththeirchildren.Theimplementingorganization (“theimplementer”)isNewGlobe,theparentofBridgeInternationalAcademies.Atthetimeofthestudy, NewGlobeoperated112privateprimaryschoolsalloverKenya.11 TheKenyanschoolyearusuallyhasthree termsthatstartjustafterNewYear’sandendlateOctober.DuetoCovid-19,the2020terms2and3 tookplace1/3-3/19and5/10-7/16of2021(withthe2021termscompressedinto7/26/21-4/2/22).All Kenyanschoolsattheimplementingorganizationhadintroducedoralreadingfluency(ORF)assessments forthefirsttimeinthemidtermandendtermexamsofterm2of2020.

Theimplementerwantedtomakeadecisionaboutwhetherandhowtouseinteractivevoiceresponsecalls (IVR)toencourageparentstodoreadingexerciseswiththeirchildren.Readingwithachildathomehas benefitsforlanguageacquisitionandfluency,evenincontextswhereparentsthemselvesmayhavelimited readingskills(Mayeretal.,2019;Yorketal.,2019;Knaueretal.,2020).Kenyanschoolswereclosedforpartof 2020duetoCOVID-19,highlightingthebenefitsofdevelopingeffectivehomeinterventionstargetingreading andnumeracy.12 Morebroadly,parentalengagementisanimportantdeterminantofchildren’slong-term successinschool.Recentresearchhasshownthatrelativelylight-touchinterventionssuchaspersonalized

10Itmayalsoreducethenumberofbeneficiariesbytheadditionalexperimentalsubjects.

11TheschoolsfollowBridge’sspecificteachingmodelandchargefees;thesefeesarelowerthantypicalprivateschoolfeesand similartotheadministrativecostsofpublicschools.

12Priorresearchhasshownthatparentalengagementinterventionscancounteractthedetrimentaleffectofextendedperiods outofschool(e.g.KraftandMonti-Nussbaum(2017)).Acombinedtextmessageandphonecallinterventionwasabletoreduce learninglossduringCOVID-19-relatedschoolclosuresinBotswana(Angristetal.,2020a).

textmessagesincreaseparentalengagement,whichinturnimprovesearlyliteracyoutcomes(Yorketal., 2019;Dossetal.,2019).Forolderchildren,parentalengagementalsoincreasesparents’informationabout attendanceandperformanceatschoolandimprovesoutcomesthroughthischannel(Berlinskietal.,2021; BergmanandChan,2021;Bergman,2021;Bettingeretal.,2021).

Whilemanyparentcommunicationinterventionsrelyontextmessages,parentalliteracybarriersand lengthrestrictionslimittextmessagingasatooltodeliverreadingexercises(ICTworks,2016).Theimplementeralreadyroutinelyusestextmessagingtocontactparentswithinformationabouttheirkid’sschooling, andcollectsphonenumbersandconsentforthispurpose.However,towhatdegreethesemessagesarereceivedandreadbyparents,andwhethertheyleadtobehaviorchange,isonlyincompletelyknown.Inan earliertrialwiththesameimplementerinNigeria,whichusedtextmessagestoencourageparentstousea WhatsApp-basedquizplatform,almostnoneofthemessagerecipientsengagedwiththequizzes(Sautmann, 2021b).

Phonecallsprovideanalternativethatmaysustainhigherratesofengagementandallowslongerinteractionsandbetterinstructionsforhomeexercises.Personalcallshavebeenshowntobeeffectiveforincreasing parentalengagement(KraftandMonti-Nussbaum,2017),butarecostlyandtimeconsumingforteachers. IVRcallsarepre-recordedandautomated,designedbyrecordingasetofmodulartextsnippetsandjingles thataresequencedinresponsetolistenerinputthroughthekeyboardorthroughspokenword.Thereisto datelimitedevidenceontheeffectivenessofIVRforimprovingearlyliteracy.Asmallpilotwith38familiesinruralCˆoted’IvoirereportsencouragingqualitativeresultsontheuseofIVRtofosterphonological awarenessinlow-literacyenvironments(Madaioetal.,2019).

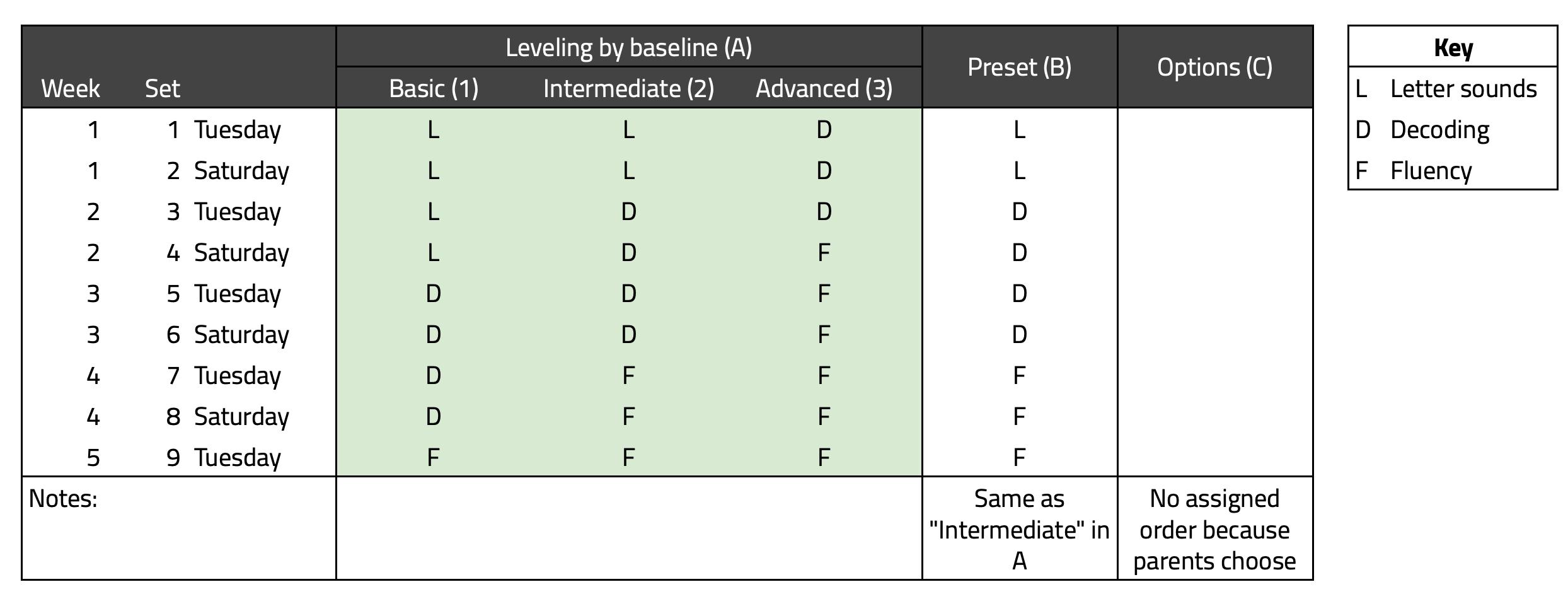

Duringpilotinganddiscussionspriortotheexperiment,itwasdecidedtotestsixIVRcallvariants.All treatmentarmsconsistoftwiceweeklycallstotheparents’phone.TheIVRdeliversasequenceofreading exercises,eitherbasedonlettercombinationsorwordsthattheparentnotesdownduringthecall,orbased onpassagesfromthechildren’sterm3homeworkbook.Anexperimentalwavecontains9setsofcalls(see below),andeachcallcontains4differentexercises.Theexerciseschangefromcalltocall.Beforeeach wave,weconductedaphonebasedopt-outprocedurethatexplainedthecallsandalsoallowedparentsto changetheenrollednumber.Thefullinterventiondesign,calllogictrees,andsamplerecordingsoftwoof theinteractivecallscanbefoundinanonlinesupplement(Sautmann,2021a).

AllIVRrecordingswerecreatedbyafemaleKenyanvoiceartistandeditedbythevoicecallprovider, Uliza.TheIVRsystemmakesmultiplecallattemptsandalsoallowstheparentto“flash”Uliza’snumber, meaningthattheycancallthenumberataconvenienttime,andthesystemhangsupandimmediatelycalls

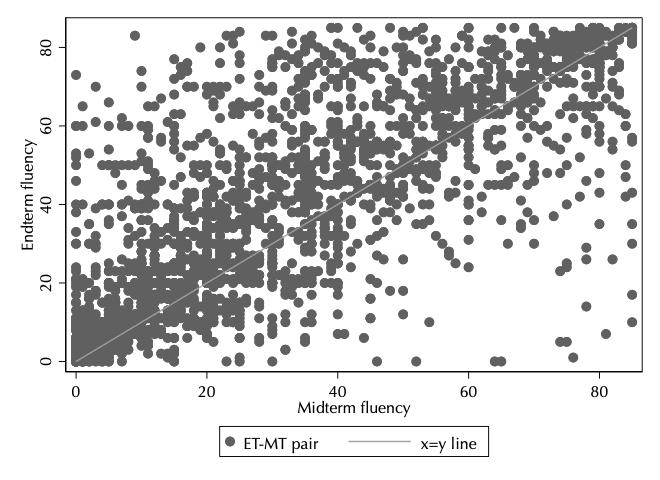

Figure1:Term2midtermandendtermoralreadingfluencyscores,inunitsofcorrectwordsperminute, asusedforexerciselevelassignment.Theleftpanelshowsthatindividualstudentscoresareonlynoisily correlated.Therightpanelshowsthatthereissomemovementfromhigherlevelingcategoriestolowerones, aswellassmallbutsignificantnumbersofstudents“skipping”frombasictoadvancedlevel.For22.5% studentsinoursample,scoreinformationwasmissing.

back.ThisisacommonmethodinKenyathatavoidscallingchargestotheparents.

Weusedthreedifferentwaysofchoosingadifficultylevelfortheexercises,andtwodifferentdelivery formats,describedindetailbelow.Wecross-combinedthe3x2interventionstocreatethe6treatment arms.Inselectingthetestedinterventions,theaimwastocreatetreatmentvariationsthatweregenuine “contenders”forhavingthegreatestimpactonhowoftenparentsreadwiththeirchildrenathome.

Varyingexerciseleveling. Baselineinformationonoralreadingfluency(ORF)fromterm2showed highvariationinreadingscores,inlinewithothercomparabledataindeveloping-countrycontexts(for instance,seeMuralidharanetal.,2019).Inthepresenceofsuchvariation,priorevidencehassuggested thattherecanbebenefitstolevelingremedialprograms(see,e.g.,Banerjee,Cole,Duflo,andLinden, 2007;Banerjee,Banerji,Berry,Duflo,Kannan,Mukerji,Shotland,andWalton,2017),andthatcustomized EdTechinterventionscouldbenefitthelowestachievingstudentsthemost(deBarrosandGanimian,2021; Dossetal.,2019).

However,ouranalysisofORFscoresshowedthattheavailabletestdataareverynoisy(asseeninfigure1) and22.5%percentofthesampleweremissingatthestartofwave1.Thereisreasontobelievethatthereis selectionbiasinnon-missingscores(seealsobelow).Thiscouldmakelevelingbasedonobservedorimputed pastscoresineffectiveorevencounterproductive.Analternativeistoleverageparents’knowledgeoftheir child’sreadingskillsandletthemchoosethedifficultylevelduringthecall.Butparentsmaybeunableto accuratelyassesstheirchildormaychooseapoorlysuitedexercise,perhapsbecausetheythemselvesare notsecurereadersorbecausetheirviewoftheirchildistoooptimistic.Acallthatallowschoicealsotakes

longer,andparentsmaystopusingthesystemiftheyfinditfatiguingorchallenging.

Basedontheseconsiderations,threeinterventionvariantswerechosen,(A)levelingonactualorimputed baselinescores,(B)providingthesamesequenceofintermediate-levelexercisestoallkids,and(C)giving parentsachoiceofexercisesfromamenu.ArmAusesobservedfluencyscoresfromtheendofterm2and assignsstudentswithfluencyscoresof0-29intothe“basic”group,30-64intothe“intermediate”group,and 65+intothe“advanced”group.Thesecutoffswereusedpreviouslyinasimilarcontext(seePiperetal., 2018).Studentswithmissingscoresareassignedtheirclassmedian.Wholeclasseswithmissingscoresare assignedtotheintermediategroup(whichalsohappenstobethefullsamplemedian).Theexactexercise sequencesinthebasic,intermediate,andadvancedgroupsaredescribedindetailinAppendixA.ArmB assignsallstudentstotheintermediategroup,whileArmCallowsparentstopickoneexercisetype(from basicletters,tolettercombinations,toadvancedtextpassages)outofasetofthree.

Varyingdeliveryformat. WealsotesttwoformatsthatusetheIVRfunctionalityindifferentways.In thefirst,thevoicecallexplainstotheparenthowtodothereadingexercisesandasksthemtocarrythem outwiththeirchildafterthecall(T1).Inthesecond,theIVRasksparentstoputthecallonspeakerphone, andthengoesthroughtheexerciseswiththeparentandchildonthecall(T2).

Apriori,eitherapproachmightworkbetterfordifferentreasons.Inbothcalltypes,theparentisasked totakenotesontheexercisesduringthecall.Theparentisinstructedtopointtothewrittenlettersor wordswhiletheIVR(ortheparent)reads,andthenagainwhilethechildreads.However,inT1,theparent maynotpronouncelettercombinationscorrectlyfrommemory.Shemayalsolistentotheexercisesduring thecallbutthennotcarrythemoutwiththechildlater.Ontheotherhand,T2maycausedifficultyifthe phone’sspeakerispoorortheIVRmovestoofastforthechildorisnotresponsiveenough.Allpartiesmay bemoremotivatedwhenthechildandparentpracticetogether,ratherthanfollowinginstructionsfroman unknownanddisembodiedvoice.

A“standard”RCTofIVRforhomereadingwouldlikelyconsistofextensivepiloting,carryingoutpower calculationstodeterminesamplesizeandnumberoftestedinterventionarms,randomizingatthecluster (school)level,andthenadministeringanIVRprogramforatleastafullschoolyear,possiblyaccompanied byahomesurveyandindependenttestsofreadingfluency.Basedonthebudgetfordeliveringanddeploying messages,thesizeofthesample,andtheavailablestafftime,suchacomprehensivestudywasnotfeasible forNewGlobe.Atthesametime,attheoutset,itwasnotevenknownwhetherparentswouldlistentothe messagesatall,andthereistoourknowledgenoexistingguidanceonhowbesttodesignsuchcalls.In

suchasituation,NGOsandpolicymakersmightresorttosimplynotusingexperimentalmethods.They mightconductaninformalpilot,implementtheprogramatscale,andthen“tinker”withitafterroll-out, orconversely,simplyabandontheidea.Adaptivesamplingcouldofferasolutionthatenablesarigorous experimentandmakesthemostofthelimitedsampleandtimeavailable.Theimplementersawasan attractivefeaturefromanethicalperspectivethatevenduringtheexperiment,alargershareofparticipants benefitfromthehigher-performingtreatmentarms.

Objective. Inconversationsabouttheexperiment,ontheonehand,theimplementerwantedtoidentify the“best”IVRcallvariant,andontheother,theywantedtoverifythatIVRcallswithreadingexercises actuallyhavepositiveeffectsonreadingfluency.Thishybridgoalwasareasontokeepacontrolgroupthat receivednointervention.Atthesametime,itsuggestedtouseadaptivesamplingtochoosebetweenthe sixcallformats.Wediscusshowthenotionofthe“best”IVRcalltranslatedintothechoiceoftargeted outcomebelow.

Constraintsontheexperimentaldesign. Theimplementerwasabletosetasideonlyonefirstgrade cohortandonetermoftheschoolyearfortestingtheIVRcalls,bothduetootherongoingstudiesanddue totheimplementer’sinternalcost-benefitassessment.

TheKenyanschooltermis10weekslong,splitequallyinto5weeksfromstarttomidtermexamsandfrom midtermtoendtermexams.Readingtestsareconductedaspartoftheseexams,providinganadministrative sourceofdata.Moreover,therhythmoftheschooltermfromstarttomidtermandfrommidtermtoendterm issimilar.Forexample,parents’attentiontotheirchild’sschoolworkmayincreaseclosertotheexams.

Relativetothecostpercall,thecost(intermsofbothmoneyandtime)ofdevelopingsequencesofreading exercisesandrecordingthemishigh.13 Therewasalsoconcernthattoomanycontactattemptsfromthe schoolcreatefatigueinparents,especiallywithpilotprogramsthatmaynotyetbeoptimallydesigned.For bothreasons,anexercisesequencecoveringonehalfofthetermwaspreferredtorunningtheinterventions forafullterm.

Jointly,theseconstraintsreducedthespaceofpossibleresearchdesignstoconductingoneortwoexperimentalwavesinthefirstandsecondhalfoftheterm,withthetotaloffirstgradersenrolledthatyearacross allschoolsastheavailablesample.

Outcomemeasurement. Theavailableoutcomevariablesweretake-upoftheIVRcalls,orcallengagementforshort,andoralreadingfluency(ORF)scorescollectedbytheschool.Measuresforbothoutcomes

13Theexercisesweredevelopedbytheimplementertogetherwiththeresearchteam.Dozensofsoundsnippetswererecorded byavoiceartisthiredbyUliza.Afirstsetofexerciseswaspilotedwithasmallsampleofparentsinanolderagegroupbefore completingalltheexercisesandrecordings.

wereprovidedbytheimplementer,withrandomIDnumbersreplacingparents’phonenumbersandthe child’snameandschool.

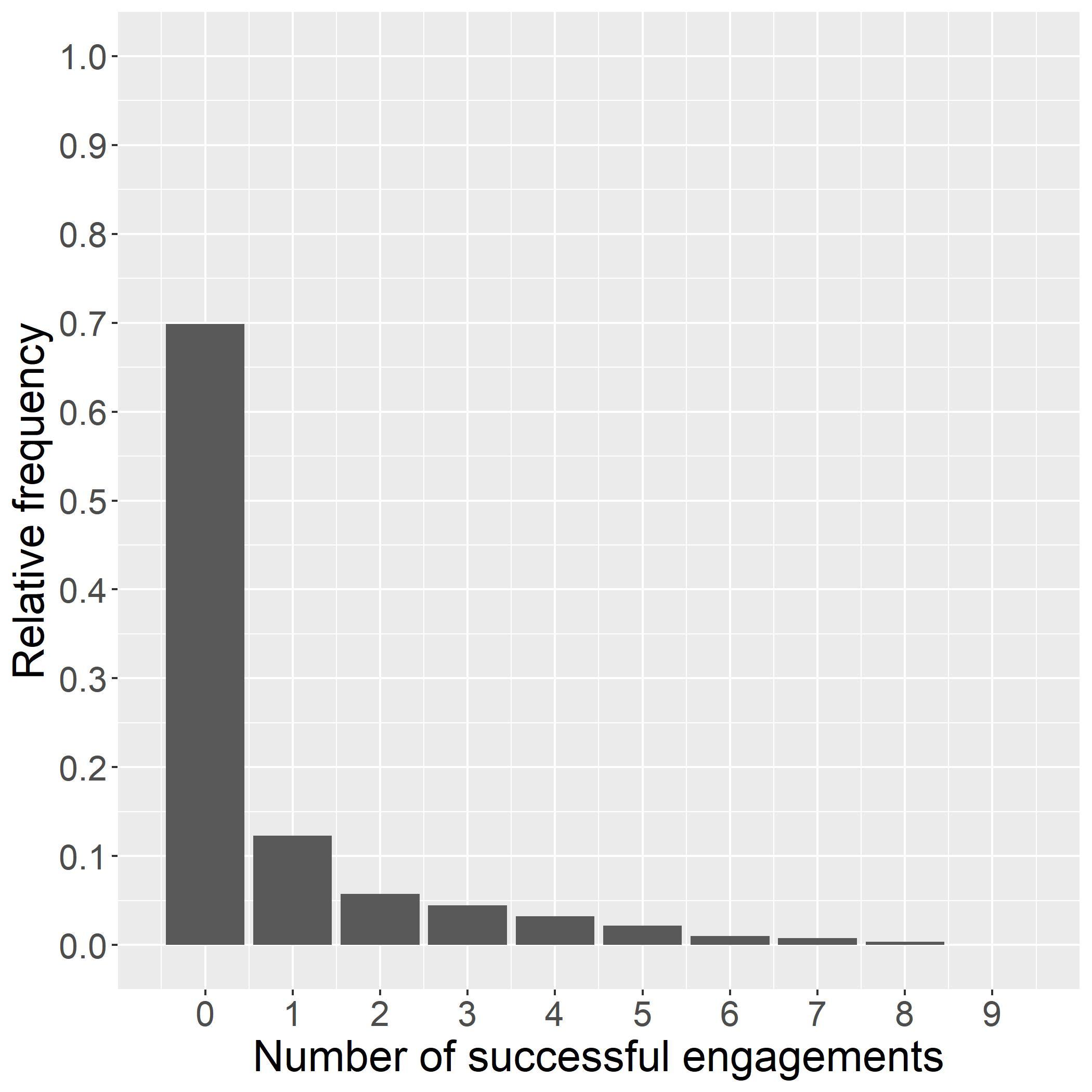

WeuseIVRproviderrecordstomeasureengagementwiththecalls,thatis,whetherthecallrecipient actuallystartstheexercises.Uliza’srecordsshoweverycontactwiththeparent’sregisteredphonenumber, alongwiththelengthofeachcallinseconds.Wedefineacallassuccessfuliftheparentstartedthefirst exercise,whichrequirestappingaphonekeytoconfirm.Wedefineaparentashavingengagedinoneofthe twiceweeklyexercisesetsiftheIVRmadeatleastonesuccessfulcallinthatset.Sincethereare9exercise setsperwave,engagementcantakevaluesbetween0and9.Callrecordsareavailableimmediately,and theyarecompleteandaccurate.

Theimplementermeasureschildren’sORFscoresduringthemidtermandendtermexaminationperiods. In2-3hourperiodssetasideforthefluencytest,ateacherexamineseachchildbycountingthenumberof wordsonalistthatachildcanreadcorrectlyinoneminuteoftime(seeRodriguez-Seguraetal.(2021)for theuseofthismeasuretoassessreadingandliteracy).Theteacherthensubmitsthescorestotheschool’s graderecordsystem.ORFscoresrangebetween0and85correctwordsperminute(cwpm)basedonthe lengthoftheprovidedwordlist.14

ThereareanumberofissueswithORFmeasurement,whichwerepartlyrevealedonlyafterwave1of theexperimenthadalreadystarted.Figure1showsthehighvariationinORFscoresbetweenmidtermand endterm.Amongthenon-missingscores,anunusuallyhighproportionaremultiplesoffive,andinsome classrooms,thereareimplausiblymanyveryhighscores.Inaddition,ahighpercentageofscoresaremissing orsubmittedlatetotherecordingsystem:ORFscoreswereavailableforonly73.5%-88.9%ofchildren dependingontheexam.15 Teacherreportsonwhyagivenscoreismissingareoftenambiguous.Overall, thedataqualityforORFscoresisfairlylow.

TargetedOutcome. Inordertouseadaptivesampling,itisnecessarytodefineanoutcomemeasure thatdecideswhichisthe“best”arm,whichinturndetermineswhichtreatmentarmswillbesampled more.Inmanysettings,thisisnotstraightforward,giventhatmultipleindicatorsrelatedtothedesired outcome(s)aretypicallyavailable.Here,theimplementerwantstoincreaseparents’engagementintheir children’seducationingeneral,becauseparentalengagementisknowntohavepositiveeffectsonchildren’s performanceinschool;atthesametime,thecallsexplicitlyencourageasetofreadingexerciseswiththeaim

14Theimplementerchoosesastandardized,grade-appropriatewordlist,trainsteachersandprovidesequipment.Themeasure caninprinciplerangefromzerotoover200,butforfirstgradersitistypicallynotabove120.

15Thetotalshareofscoresthataremultiplesof5is36%,andtheobservedscoredistributionsshowunusualheapingeven whenaccountingforcensoringat0and85.Teacherssometimesdelaysubmissionorentirelyfailtosubmitexamscoresfortheir class.WedescribethepatternsofmissingnessandsuspectedroundinginmoredetailinAppendixBinTablesA.1andA.2. Partofthereasonthattheproblemsofmissingandroundedscorespersististhatatelementaryschoollevel,thesescoresdo notaffectthestudent’sprogressionintothenextgrade,nordotheyaffecttheteacher’sevaluation.

toimprovereading.Callengagementmeasureswhetherparentslistentothereadingexercises,butwedo notobservetheinteractionstheyhavewiththeirchildren.Asdiscussedabove,ORFscoresareanimperfect measureofthechild’sreadingability.

Inprinciple,bothcallengagementandORFscorescouldbeusedtocreateacombinedoutcomemeasure. Moreover,ifthereisa(known)relationshipbetweenthetwomeasures,e.g.highercallengagementimplies greaterreadingimprovementsandthereverse,thenanadaptiveexperimentcouldequivalentlytargeteither outcome.16 Apriori,weconjecturedthatcallengagementispositivelycorrelatedwithreadinggains.First, someoneactuallylisteningtotheexercisesisanecessaryconditionforthechild’sexposuretotheseexercises. Beyondthefirstcoupleofcalls,asimplemodelofmarginalreturnsalsosuggeststhatparentsaremorelikely toengagewiththecallsiftheyfeelthatthechildlearnssomethingandtheyplanonactuallydoingthe exercises.However,therecouldbereasonsthatcallengagementandORFarenotaligned:anyincreasein readingabilityisacombinationof(i)thechild’s exposure totheexercises,and(ii)conditionalonexposure, howeffectivelythedeliveryandcontentoftheexercisesinthisarmimprovereading(efficacy ofthearm forshort).Treatmentvariants(T1)and(T2)couldpotentiallyhavedifferentexposure,conditionalon observedcallengagement,andthetreatmentarmdesignchoicesregardingleveling(A,B,andC)may exhibitdifferencesinefficacy.

Withoutanyconstraints,theimplementermighthavechosenthebestarmbasedonaweightedaverage ofORFandengagement.However,wewereunabletodetermineassignmentsharesinwave2basedon themidtermORFscores.17 Thegradingdaywasmovedduringwave1andtookplaceafterthestartof thesecondhalfoftheterm.Duetothesubmissiondelaysdescribedabove,ORFscores“tricklein”for severalweeks,andevenaftertheendoftheterm,morethanaquarterofthemidtermdatawasmissing(see TableA.1).Thechoiceinpracticewasthereforetoeitherexclusivelytargetcallengagementinanadaptive experiment,startthesecondwavelateandwithincompletedataforsomeformofadaptiveassignmentbased onORFscores,orconductanexperimentwithuniformassignment(orabandonthetest).

Inthisdecision,itplayedarolethateveninthebestcaseoftimelyandaccurateORFmeasurements, anyeffectsofIVRcallsonreadingabilitywerelikelytobeonlyincompletelyrealizedbytheendofthetrial intervention.Comparableearly-readinginterventionsmeasureeffectsafteraninterventionperiodofseveral monthsorawholeschoolyear(Dossetal.,2019;Yorketal.,2019).Moreover,cumulativeeffects–e.g. duetohabitformation–arelikelytoaccrueforasignificantperiodoftimeafterinterventionend,soitis

16Thisrelationshipwouldneedtobeestablished,e.g.frompilotdata.Cariaetal.(2020)makereferencetotheliteratureon statisticalsurrogates–measurableorshorttermoutcomesthatcan“standin”forhardertomeasureorlonger-termoutcomes–toarguethatadaptiveexperimentscouldtargetshort-termoutcomestoachievehigherwelfareinthelongterm;seealsoAthey etal.(2019)foraproposaltocreate“surrogateindices”frommultiplevariables.

17Initially,weplannedtouseadaptivesamplingtotargetORFscores.Thechangeisdocumentedinthepre-analysisplan, see(Sautmann,2022).

unlikelythattheimpactsofthetreatmentwerealreadyfullyrealizedbytheendoftheterm.

Basedontheseconsiderations,itwasdecidedtoexclusivelytargetcallengagement.Ultimately,the implementervaluedparentalengagementsufficientlytofocusonmaximizingcallresponserates,ratherthan attemptingtochooseatreatmentarmbasedonverynoisyeffectestimatesoffluencygainsandrisking inconclusiveresults.Anotherwaytoviewthisdecisionistomaximizelearningaboutwhicharmhasthe highestcallengagementrates,attheexpenseoflearningmorepreciselywhicharmhasthegreatestORF gains.Whilethissolutionmaynotbeoptimal,itreflectsanotherrealityofpolicychoice,thatpolicymakers sometimeshavetomakedowithimperfectdata.

SampleandRandomization.

Wedeterminedthesampleusingthephonenumberonrecordforthe parent.18 Wedropped2schoolsthathadfewerthan5students,and2schoolswithveryinflatedORF scores,leavinguswith108schoolswith3,163uniquestudent-phonenumbercombinations.

Wefirstrandomlyassignedhalfofthesampletowave1and2(1,581and1,582phonenumbers,respectively).Wedidnotformallyassessthebestsamplesplitbetweenfirstandsecondwave,butsmall-sample simulationssupportequal-sizedwaves(seesupplementofKasyandSautmann(2021a)).Beforethestart ofeachwave,parentsreceivedanintroductorycall,followedbyatextmessageconfirmingenrollmentand explainingproceduresforoptoutandforswitchingphonenumber.Someparentsoptedoutexplicitlyand somephonenumberswereinvalid,leavingasampleof1,494inwave1and1,384inwave2.

Therandomizationwasstratifiedattheschoollevel.19 Inwave1,theassignmentsharesforthe6treatment armswereequally1/7;inwave2,weusedtheassignmentsharesgivenbyexplorationsampling,keeping1/7 ofthesampleasacontrolgroupineachwave.Duetoindivisibilities,thetotalsharesareclosebutnotequal tothetargetedshares,asshowninTable2insection5.

EstimatingORFeffects. Inmanyapplications,outcomesotherthanthetargetedoutcomeareofinterest totheexperimenter.Here,weestimatetheeffectsofthetreatmentsonORFwithreadingfluencyexam scoresobtainedaftertheexperimentwascompletedtolearnwhetherthetreatmentarmwiththehighest engagementseesincreasesinchildren’sreadingperformance.Wealsobrieflydiscussthepossibilitythat therearedifferencesinhowengagementwiththecallstranslatesintoreadinggains,whichmightimplythat thecallformatwiththehighestcallengagementmaynotbetheformatwiththehighestreadinggains.

18Theimplementerhasparentalconsenttousethisphonenumberforschoolrelatedcommunications.Basedonenrollment datafromthestartofterm3,werandomlyselectedonestudentIDformeasurementinthefewcaseswhereseveralstudent IDswereassociatedwiththesameparentalphonenumber(likelysiblings).Phonenumbersandschoolsarede-identifiedbythe implementerbeforesharingwiththeresearchers.

19Wealsostratifiedassignmentonwhethertheopt-incallorconfirmationtextmessagewereanswered.Forexample,inwave 1,alargeproportionofthesample(796studentIDs)neitheroptedinnorexplicitlyoptedout.However,theextensive-margin results(AppendixC.4)showedthatmostnumbersansweredthephoneatleastonceduringtheexperiment,andsoweignore thisintheestimation.

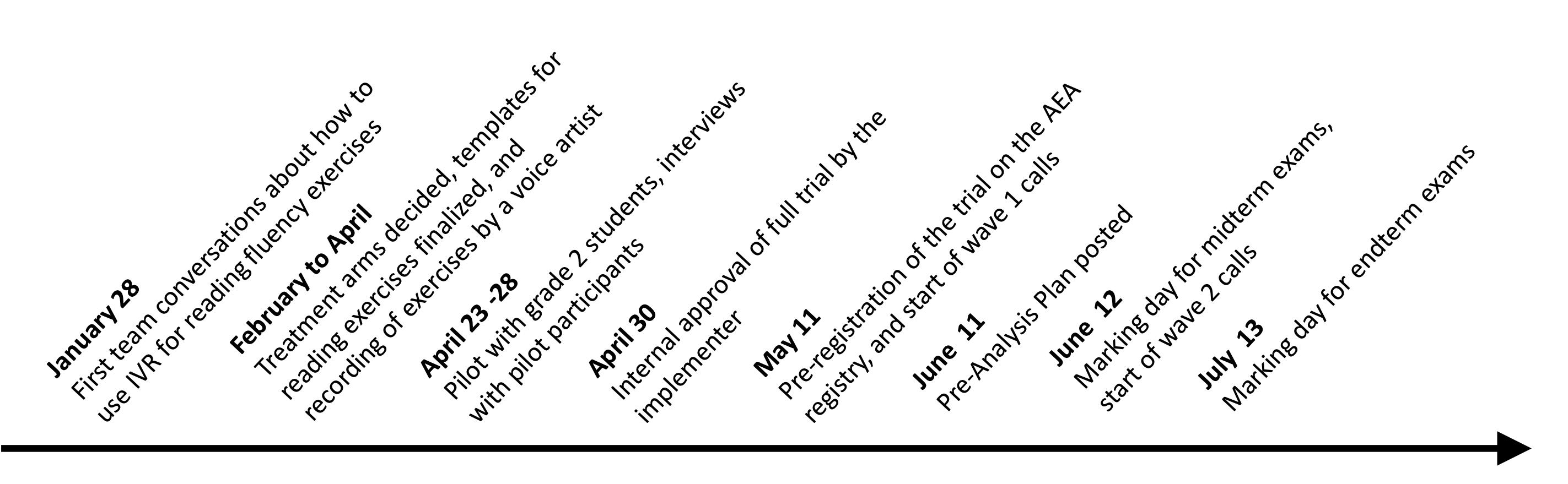

Figure2:Timelineforthestudy.

ImplementationandPre-Specification. Figure2showsthattheIVRexperimentwascarriedouton averyshorttimeline.Developmentandimplementation,includingdesigningthereadingexercisesand recordingandprogrammingthecallsforalltreatmentarms,werecompletedinthreemonthsuptoApril30. Theresearchteamdevelopedthestatisticalmodelforparentalengagementandcarriedoutthetreatment assignmentduringwave1(termstartMay11tomidtermexamonJune12),andthemodelforestimating readingfluencyduringwave2(midtermtoendtermexamJuly13)andafter.Thishasdownsides;for example,notenoughpilotdatawasavailabletoimproveourpriorse.g.aboutschoolrandomeffects,and whilethefirstwaveoftheexperimentwasongoing,newinformationwasstilllearned,suchasthedelay toobtainingORFscores.Thetimelinealsoshowsthattheexperimentwaspre-registeredpriortothefirst wave,butbythetimethepre-analysisplanwasfiledonJune11(beforestartofwave2),theplansforthe experimenthadchangedsignificantly.Ingeneral,shorttimewindowsandincompleteinformationinthe experimentaldesignphasemaymakeadaptivesamplingmoreattractive,butwillalsomakepre-specification morechallenging.

Remark:Pre-AnalysisPlansandTrialRegistration. Aquestionfortheresearchcommunitywillbewhether adaptivepolicychoiceexperimentsshouldbesubjecttothesamenormsofregistrationandpre-specification as“standard”experimentsforcausaleffectestimation.20 Afullanalysisoftheincentivesatplayrequires alargerbodyofevidenceonthemethod,butapriori,theneedfor pre-specification seemslesspressing: dependingoncontextthereisoftennospecificincentivetodemonstratetheeffectivenessofonetreatment armoveranother;themetricofexpectedpolicyregrethasnoestablishedcut-offsakintop-valuesfor conventionalsignificancelevels;and,mostimportantly,afterthefirstadaptivewaveitisnotpossibleto changethetargetedoutcomeortheestimationapproach,creatingcommitmentbeforethedataisfully 20Resultsshowingsignificanteffectsoftenhavehighervaluetobothresearchersandpolicyorganizations,whichcontributes toissuessuchasdatamining,thefiledrawerproblem,publicationbias(e.g.,AndrewsandKasy,2019)andsoon,familiarfrom theliteratureonresearchtransparency(ChristensenandMiguel,2018).

known.Theoppositeistruefortrial registration:policychoiceexperimentsarelikelytobeusedtolearn abouttheeffectivenessofmanydifferentpolicyoptionsforthesameoutcome.Adaptivetrialsmayinform preliminaryworkwherelesssuccessfulinterventionsareneverimplementedortestedatscale.Thefiledrawer problemseemsparticularlysalientinthecontext.Infact,anaturalextensionofadaptivesamplingacross wavesistoincorporateexistingevidenceintothepriorsthatinformtheresearchdesignofnewexperiments (seee.g.PouzoandFinan,2022).Thisformofiterativelearningrequiresacompleterecordofallprior evidencegatheredonthetreatmentsunderconsideration.

ThissectiondescribeshowweestimatetreatmenteffectsonparentalengagementandORFmeasures,and howtheengagementestimatesareusedforadaptivetreatmentassignmentandfinalarmchoice.Wealso commentonthemodelingchoicesandimplicationsforpolicychoiceexperimentsmoregenerally.

4.1 TheModelsforCallEngagementandOralReadingFluency

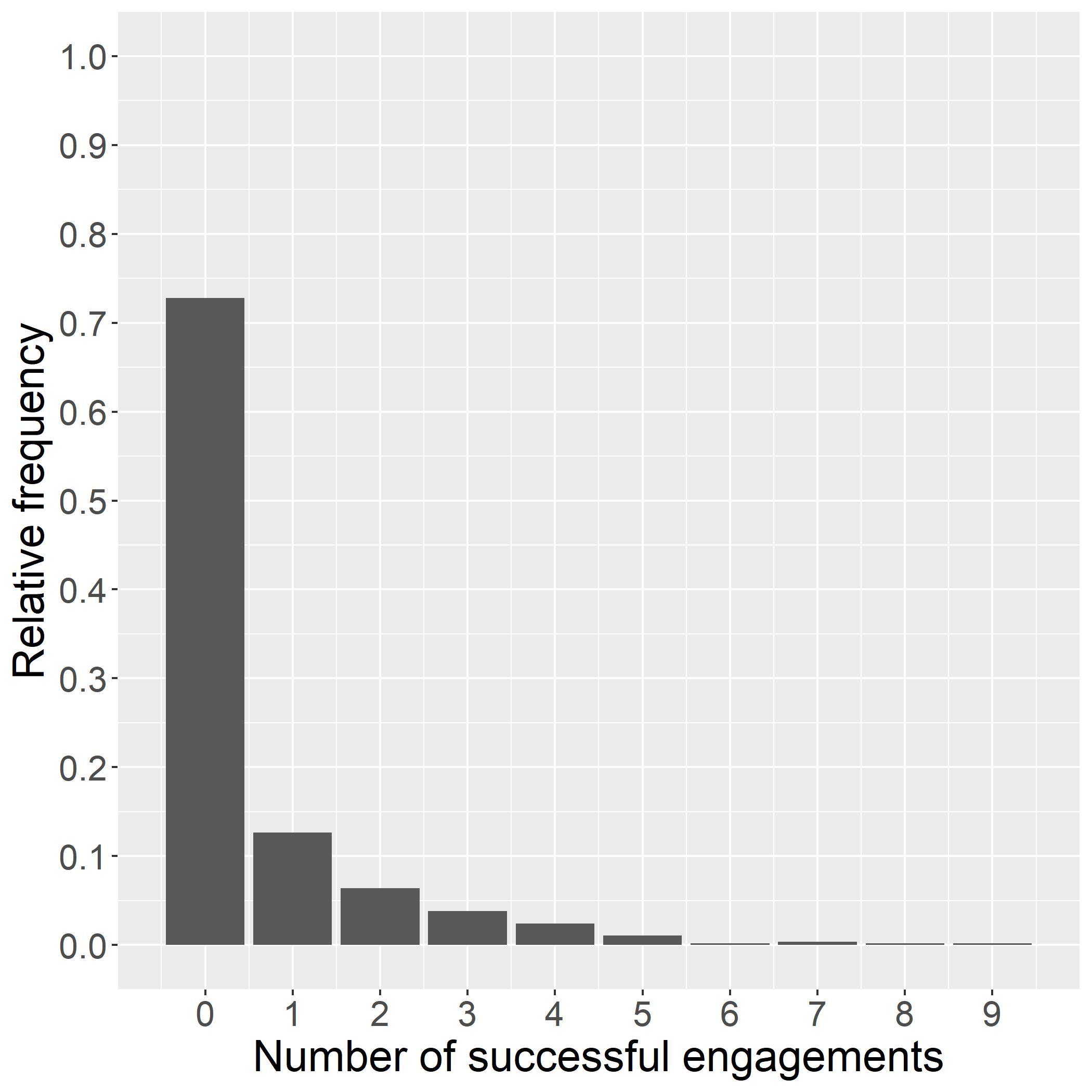

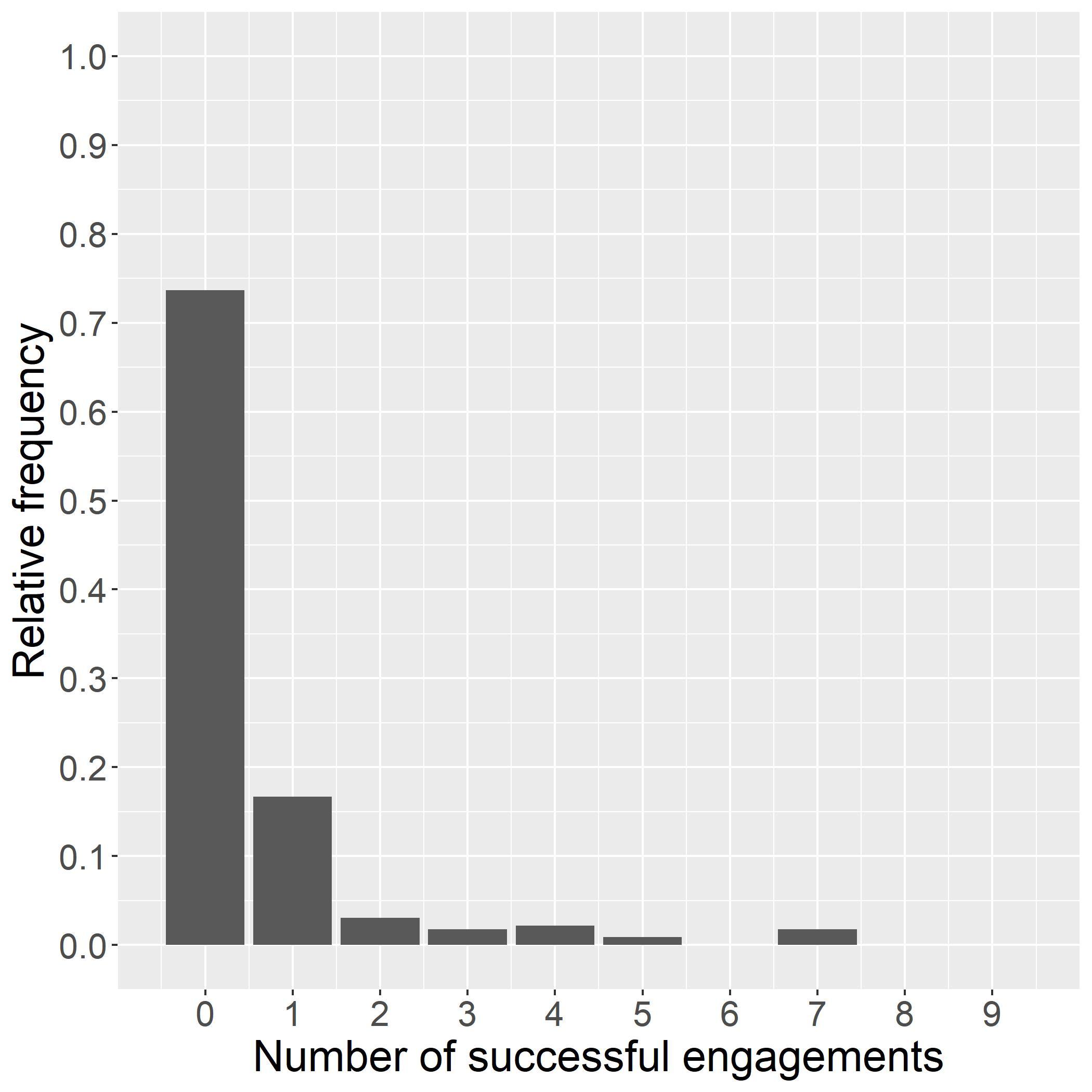

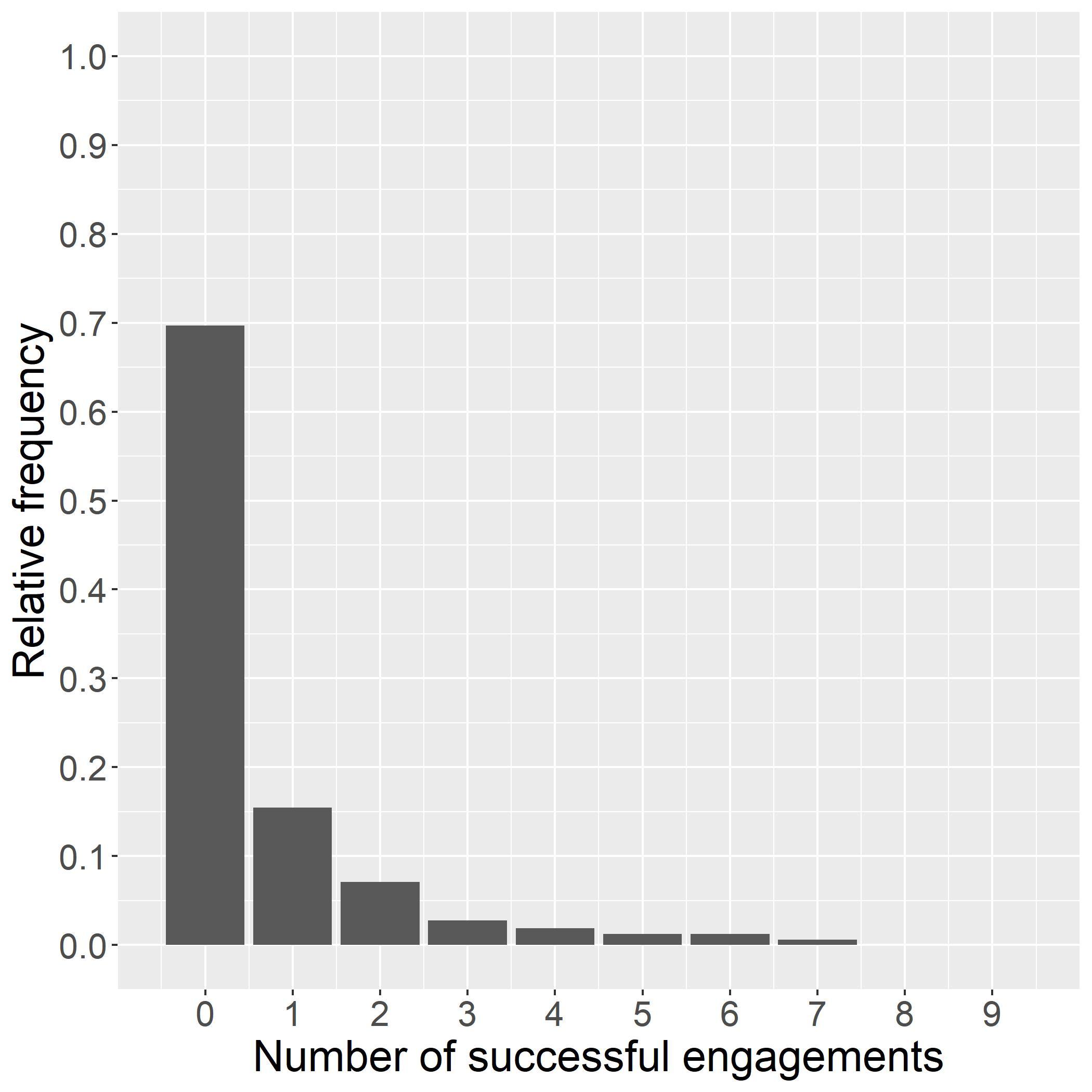

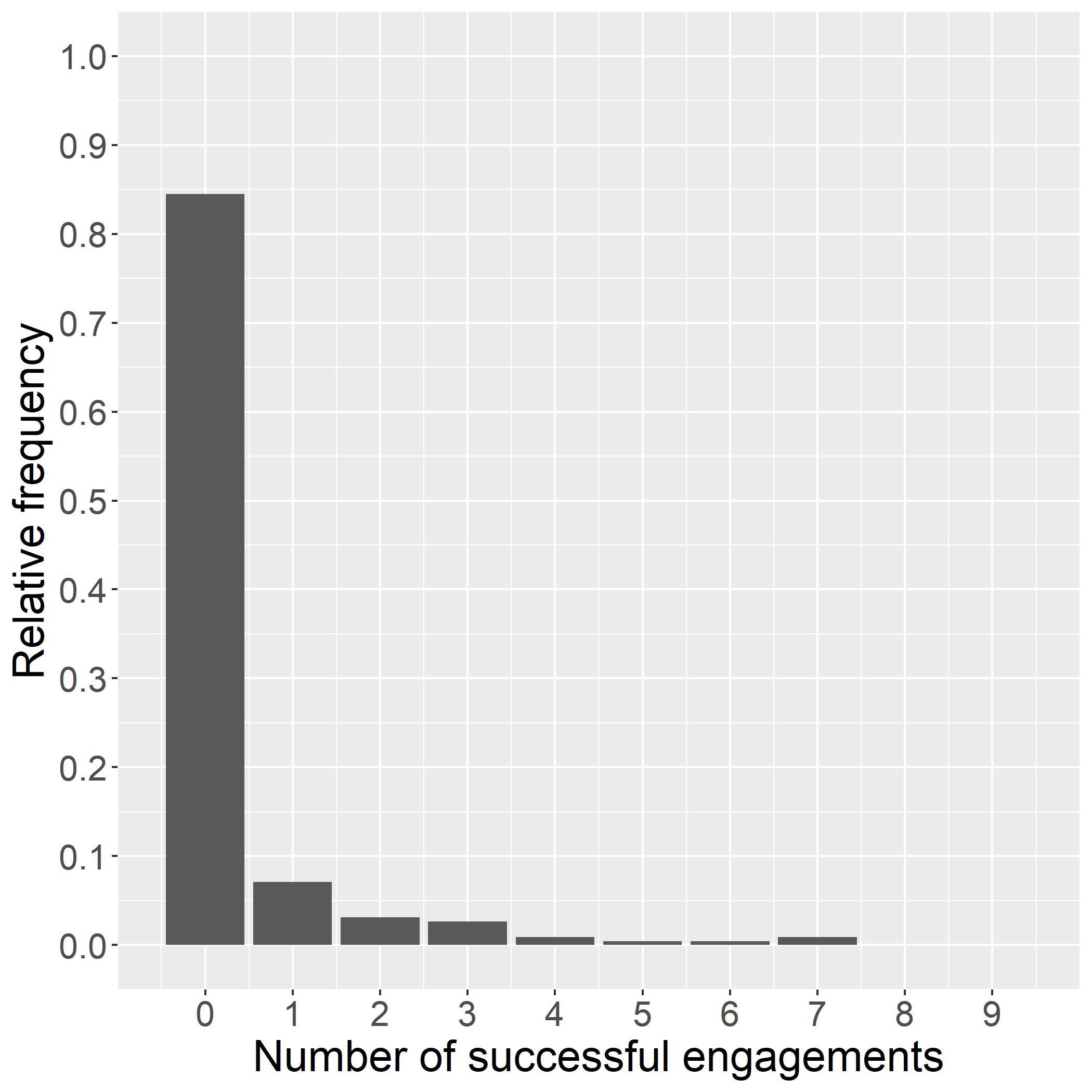

CallEngagement. Let Z sk i bethenumberofsuccessfulcallstoaparentofchild i inschool s allocated totreatmentarm k ∈{1,..., 6}.Weassumethatpotentialengagementisstationaryacrossthetwoterms andforsimplicitysuppresstheindexforwave t.Nocallsweremadetothecontrolgroup,sowerestrictthe sampletoenrolledphonenumbersinthe6treatmentarms.Weassumethat Z sk i isadrawfromaBinomial distributionwithatmost9successesandaverageprobabilityofengagement θsk ∈ [0, 1].Thisismotivated bythedistributionoftheobservednumbersofsuccessfulengagementsineachtreatmentarm,shownin AppendixC.1.Wemodeltheaverageengagementprobabilitywithahierarchicallogisticregressionmodel withschoolrandomeffects.Thus,wehave

informationinthismodel–theonlyindividual-levelinformationwehave–becauseoftheproblemswith missingandnoisydataoutlinedearlier.

Wedonothavemuchpriorinformationonexpectedengagement,soweuseanon-informativeimproper prioron

Thehyperparameters

describetheaverageengagementprobabilityineachtreatmentarm andthearm-independentvarianceoftheengagementprobabilityacrossschools.Each

isarealizationof theaveragesuccessprobabilityspecifictotheschoolandtreatmentarm.

Whileourmainestimatesfocusontheaveragenumberofcallsperphonenumber,inappendixC.4wealso reportestimatesoftheextensivemarginoftake-up.Theseusebinarylogitmodels,withtheonlychangeto themodelabovethattheoutcomehasaBernoullidistributionwithprobabilityofsuccess

Remark:ModellingTreatmentEffects. Themodelisagnosticaboutpotentialinteractioneffectsanduses dummiesforalltreatmentarms.Acommonapproachtoestimatingtheeffectsofcross-randomizedinterventionsistoimposeadditionalstructure,e.g.byassumingadditiveeffectsoftheinterventionvariantsT1/T2 andA/B/C.However,notethatthisimposesconstraintsacrosstreatmentarmsthatmayinterferewith efficientlearningiftheunderlyingassumptionsareincorrect.Conversely,ifitisknownthatthetreatment effectshaveaspecificstructure,theoptimalassignmentshareschange,asobservationsfromonetreatment armprovideinformationaboutotherarms,andtheefficiencypropertiesofalgorithmssuchasexploration samplingarenotknowninthissetting.

OralReadingFluency. OurestimationoforalreadingfluencyusesORFscoresfromthreeperiods:the endtermexamofterm2(E2),andthemidtermandendtermexamsofterm3(M3,E3).Thismeanswe captureallstudentspre-treatment,wave-1studentsintwoperiodsposttreatment,andwave-2students inoneperiodposttreatment(providedtheirORFscoreisnotmissing).WeuseaBayesianapproachfor consistencyandbecauseBayesianinferenceisvalidevenwithadaptivesampling.

Remark: Notethat,unlikeforcallengagement,weexpectthatORFscoresincreaseovertimeindependently oftheintervention,asstudents’readingabilityimprovesoverthecourseoftheschoolterm.Thecontrol grouphelpsdistinguishthepuretimetrend,capturedby

,fromanycommoneffectsoftheIVRcalls onORF.Inpurepolicychoiceexperimentswithstationaryoutcomes,acontrolgroupisnotneeded.But samplingacontrolgroupandincludingaperiodrandomeffectinthemodelcanbeusefuliftheoutcome targetedforadaptivesamplingisexpectedtovaryovertime,evenifthetreatmenteffectshavethesame distributionacrosswaves.

ModelFitness. Weconductstandardchecksonthedistributionofpredictedoutcomesforthecallengagementandtheoralreadingfluencymodeltovalidatewhetherourmodelsarecorrectlyreplicatingthe characteristicsoftheobservedoutcomevariable.Wealsocheckthesensitivityofourresultstodifferentprior distributionspecifications.Forthecallengagementmodel,weselectfourdifferentpriordistributionsfor βE k (βF k forORF):(i)anormaldistributioncenteredon0andvarianceequalto100,(ii)aT-Studentdistribution with1degreeoffreedom,mean0andvarianceequalto100,(iii)anormaldistributioncenteredon0and

varianceequalto1,and(iv)aT-Studentdistributionwith1degreeoffreedom,mean0andvarianceequal to1.Next,wefollowthesameapproachwith κE (κF forORF)andtestthefollowingpriordistributions: (i)ahalfnormaldistributionwithmean0andvarianceequalto100,(ii)aninverse χ2 distributionwith 1degreeoffreedom,and(iii)ahalfT-Studentdistributionwith1degreeoffreedom,mean0andvariance equalto1.Inallthesecases,theresultsarenotaffectedbytheselectionofthepriordistribution.Given thelargesamplesize,thelikelihoodisdominatingtheprior.

Inwave2,wewanttousetheExplorationSamplingalgorithmproposedinKasyandSautmann(2021a)to assignexperimentalunitstotreatmentarms.Doingsorequirescalculatingtheprobabilityoptimal pk t after eachwave.InthepolicychoicemodelinKasyandSautmann,theoutcomeisbinary,therearenocovariates, andtheparameterofinterestissimplythearmmean θk withaBetaprior.Theposteriorsusedtoderive pk t thereforehaveaclosedform.Here,weestimateageneralizedlinearmodelthatallowsforaschool-specific averagecallsuccessrate;appropriateifweexpectoutcomestovarysignificantlybetweenclusters(suchas schools).However,thisimpliesthattheexpectedoutcomeinarm k, θk = ET [θsk|k],dependsontherandom effects(notethat θsk isthere-scaledexpectationofcallengagement Z sk i ).Moreover,wesampletheposterior distributionofallparametersusingMCMCwhichrequiresmanynumericaldraws.

Inordertosimplifythecalculationof

,weusethat

ifandonlyif

>β

.Inourmodel,this isthecasesince

isstrictlyincreasingin

E .Thisimpliesthat

foranyrealizationoftheschooleffect

orthedispersion parameter

Pr

andthereforewecansimulatetheprobabilitythatarm

(4)

Attheendof

school-specificsuccessprobabilityundertheoptimaltreatmentarm).

Theexpectedprobabilityofasuccessfulengagement θk = ET [θsk|k]andtheexpectedregret ET [∆k]cannot bederivedfromthedistributionofthe {βE k } alonebecauseofthenon-linearinverselogittransformation logit 1(x)= e x 1+ex 23 Wethereforedrawfromtheposteriordistributionsof κE and βE andthestandard normaldistributionof ηE s tocalculatethesuccessprobabilityineacharmandschool.Thenweaverageover these θsk drawstoobtain θk aswellas ET [∆k].

Remark:Predictingprobabilityofsuccessandpolicyregretwithschool-leveleffects. Bydrawingtheschool randomeffectsfromthenormaldistribution,weimplicitlytakean“out-of-sample”approachthatignores thedistributionofrealizedrandomeffectsinthestudentsample.Thisisinformedbythefactthatwedid notfindimportantdifferencesbyschoolsize,suchasacorrelationbetweenaverageORFscoresandsize.We thereforetreatnewgenerationsofstudentsasrandomdrawsfromthedistributionofschoolrandomeffects. Analternativewouldbetotreattheschoolrandomeffectsaspersistentandcombinetheposteriorsofthe schoolrandomeffectswithassumptionsabout(future)classsizestoobtaintheexpected(future)engagement probabilityandregret.Theuseofexpectedregretbasedonpredictedtreatmentoutcomesasthedecision criterionrequiresmakingexplicitwhatassumptionsareusedtomakepredictions.

Remark:Heterogeneity. Relatedly,ourapproachtocalculating pk t restsonthemonotonicityofthe θsk in βk Theapproachdoesnotapplywhen“preferencereversals”occur.Asasimpleexample,supposearm k hasa strongeffectinsomeschoolsandnoneinothers,whereas k hasamoderateeffectinallschools.Inthiscase, itdependsonthetreatmenteffectdistributionwhicharmhasthehighestaveragetreatmenteffect;here,for example,thesizeofthedifferentschools.Ifsuchheterogeneityisexpected,theresearcherneedstoestimate thedistributionof θk i moreflexibly,forinstancebyallowinginteractionsbetweencovariatesandtreatment, inwhichcasederivingboththeprobabilityoptimal pk t andexpectedregret ET [∆k∗ ]requiresassumptions aboutthecovariatedistributioninthepopulation.Notealsothatpreferencereversalsimplythattreatment k isoptimalforsomeschools,whereasforothersitis k ,inotherwords,theunconstrainedoptimalpolicyis specifictoeachschool.TargetedpolicychoiceisdiscussedbrieflyinKasyandSautmann(2021a),andCaria etal.(2020)describeatargetedadaptiveexperimentusingtheirproposedtemperedThompsonalgorithm. Targetinghastheadvantagethatwedonotneedto“trade-off”strataforwhichdifferentpoliciesareoptimal, butitisnotalwayseasytoimplementinreal-worldcontexts.

Asdiscussed,treatmenteffectestimatesfromadaptivelycollecteddataaresubjecttosamplingbias,and focusingontheeffectinthebestarmleadsto“winner’scurse”.Correctionsforthesesourcesofbiasare rapidlyevolvingfieldsofresearch.

Toourknowledge,thereisnomethodyetavailabletocorrectforadaptivesamplingbiasinmodels withrandomeffects,butthereexistweightingapproachesforarangeofsettingsthatmakeestimators asymptoticallynormal(Hadadetal.,2021;Zhangetal.,2021,2020).Inparticular,thesquarerootinverse propensityweightingproposedbyZhangetal.(2021)–whichinoursettingcorrespondstoweights 1 qk t forobservationsinarm k —appliestom-estimatorsincludingBinomialGLM.Usingtheseadaptiveweights resultsinanestimatorthatisasymptoticallynormal.Insection5.3,weexaminehowtheseweightsaffects pointestimatesandconfidenceintervalscomparedtoanunweightedBinomialGLMestimate.

Inaddition,Andrewsetal.(2021)havedevelopedcorrectionsforthe“winner’scurse”thatarisewhen estimatingthetreatmenteffectinthebestarm.Weconstructconfidenceintervalswith“unconditional coverage,”whichallowvalidinferenceontheeffectofIVRcallsonengagementwhenthebestcallformat isimplemented(butregardlesswhichofthesixformatsthatis).24 Thesecorrectionsrequirenormally distributedestimates.FollowingasuggestionbyHadadetal.(2021),weusetheadaptivelyweightedBinomial GLMestimatesasinputsintothesecorrectionsandshowhowthischangesthepointestimatesandconfidence intervals(section5.3).TheseapproachesarenotdirectlycomparabletotheBayesianestimateswithrandom effects,buttheyallowustogainsomeintuitionabouthowthetreatmenteffectestimateschange.Tworecent softwarepackagesmakeiteasytoapplythe“winner’scurse”corrections(Shreekumar,2020;Bowen,2022).

5.1 CallEngagement

Table1presentsestimatesofthetreatmenteffectsfromBayesianBinomialGLMmodelsasspecifiedin Equation(2).Weshowboththeestimatewithonlywave-1dataandwithdatafrombothwaves.The tablereportsthemeansand,inbrackets,the95%highest-probabilitydensity(HPD)intervalsoftheposteriordistributions.25 Ahighercoefficientisassociatedwithagreateraverageprobabilityofsuccessful engagement.26

Onemaydebatewhetherconditionalorunconditionalcoverageisappropriate.Inanexperimentthatcomparesdifferent

Notes:

Valueofzeroliesoutsideofthe95%credibleinterval.Wesimulate4independentMarkovchainsof4,000 posteriordrawseachanddiscardthefirst2,000aswarmup. Theremaining8,000drawsareusedtogeneratetheposterior distributionsofthecoefficients.TheSplit-R ofeveryposteriordistributionisbelow1.01andtherearenodivergent transitions.

Table2:Treatmentallocationinwaves1and2.

Wave1Wave2

TreatmentTarget%Actual%Num.Target%Actual%Num. studentsstudents

T1A14.28%14.12%2117.44%8.45%117

T1B14.28%14.73%22039.26%40.46%560

T1C14.28%13.86%20728.45%26.81%371

T2A14.28%14.32%2140.89%1.01%14

T2B14.28%13.72%2059.68%8.53%118

T2C14.28%15.13%2260.00%0.00%0

Control14.28%14.12%21114.29%14.74%204

Notes:treatmentarmsampleallocationonwaves1and2.Target%showsthetargettheoreticalshares ofeachtreatmentarm.Observed%showstheactualtreatmentallocationafterrandomizationwith stratification.Num.studentsisthenumberofstudentsineachtreatmentarm.

Theestimatesfromwave1inTable1wereusedtodeterminetheexplorationsamplingsharesforwave2. Table2showsthetheoreticalsamplesharesineachtreatmentgroup,aswellastheassignedsampleshares afterstratifyingbyschool,bothforwave1andwave2.Explorationsamplingreducedthesamplingshare assignedtotreatmentsT2AandT2Ctozerooralmostzero.Moreover,T1AandT2Breceivedonlyslightly over8%ofthesample.ThebulkoftheallocationwenttoT1BandT1C(asidefromthecontrol).These arebothcallswheretheIVRinstructstheparenttoleadreadingexercises,butinBthesameintermediate exercisesequencingisusedforall,whereasinCtheparentcanchoosetheexercises.

Column(1)inTable1showsthatsomedifferencesintreatmenteffectsalreadyemergedinwave1,which ledtothedifferencesintreatmentassignmentinwave2.Thefullsampleestimateincolumn(2)bothshows slightlydifferentpointestimatesandsignificantlytighterHPDintervals,especiallyforthehigher-performing treatments.Figure3displaysthetreatmenteffectposteriordistributionsafterwave2,correspondingtothe estimateincolumn(2)ofTable1.Theshapeofthedistributionsshowsthatthehighertreatmenteffects areestimatedwithsignificantlygreaterprecision.ThisallowsafinerdistinctionbetweenT1A,T1B,and T2B.Afterwave2,T1Bisthetreatmentarmwiththehighestlevelofengagement,withapointestimate of

Table3providesadditionalinformation.Columns(1)and(2)showtherawnumbersofattemptedengagementsandshareofsuccessfulengagements(dividingthenumberofsuccessfulcallsbythenumberofcall attempts).Columns(3)to(5)arebasedontheposteriorofthetreatmenteffectvector βE .Themeanand standarddeviationineacharmreplicatetheestimationresultsincolumn(2)ofTable1andshowoncemore thathighermeansareassociatedwithlowerdispersionoftheestimate.Column(5)showstheprobability optimal

2 foreacharm k.TheposteriorprobabilitythatT1Bistheoptimalchoiceisover93%;three

Notes:thefigureshowstheposteriordistributionofparentengagementcoefficientsafterwave2.Greatervalues areassociatedwithahigherprobabilityofasuccessfulengagement.Theverticalbarmarksthemedianofeach posteriordistribution.Theshadedareasindicatethe95%credibleintervals.Atotalof8,000posteriordraws sampledfrom4independentMarkovchainswereused.

Figure3:Posteriordistributionsofparentengagementcoefficients.

arms(T1C,T2A,andT2C)haveessentiallyzeroposteriorprobabilitythattheydeliverthehighestlevelof engagement.ArmT1A,parent-ledreadingwithleveledexercises,hasthesecondhighestengagementrate of7.43%,buthasonlya5.24%probabilityoptimal.

Thelasttwocolumnstransformtheposteriorestimatesintoanaverageprobabilityofsuccessfulengagementforeacharm, θk,andreporttheexpectedpolicyregretbasedontheprobabilityofengagement,the objectiveofinterest(seesection4).ThisstatisticshowsthatimplementingT1Bwouldleadtoanexpected lossintermsoftheprobabilityofasuccessfulcallofonly0.02percentagepoints.Fortheothertreatment arms,thelossrangesbetween0.99ppand4.49pp.Theseexpectedlossesareequivalenttolessthan1%,12%, and53%ofthehighestestimatedsuccessprobabilityinarmT1B(of8.40%).

Inordertolookmoreintoparents’decisiontoanswerthebiweeklyIVRcalls,wealsoanalyzetheextensive marginofengagement.AppendixC.4showsestimatesfortheprobabilityofanysuccessfulengagement (i.e.,whethertherecipientstartedthereadingexercisesinanyofthecallsreceived)andtheprobabilityof answeringthephoneatleastonce.TablesA.6andA.7reportthecoefficientestimatesandthecorresponding treatmentarmaverages.Thearmshadnearlyidenticalinitialresponserates:infivearmsatleastonecall wasansweredwith84.1%-86.6%probability,andtheresponseratewasonlyslightlylowerinT2A(81.7%). Theshareofphonenumberswithatleastonesuccessfulengagementvariessomewhatmoreacrossarms, andisparticularlylowinT2C,wheretherateisonlyabouthalfofwhatitisinotherarms.However, T1A,T1BandT2Bhavenearlyidenticalengagementprobabilities.Itisinstructivetoalsocomparethe

Table3:Callengagement:treatmenteffectestimatesafterwave2. RawnumbersPosteriorsof

E Average engagement

k

ArmCallShareMeanSDProb.SuccessPost.exp.policy attemptssuccessfuloptimal pk t prob. θk regret ET (∆k) (1)(2)(3)(4)(5)(6)(7)

T1A2, 9527.28%-2.630.095.24%7.43%0.99%

T1B7, 0208.40%-2.490.0793.19%8.40%0.02%

T1C5, 1936.47%-2.780.080.00%6.49%1.93%

T2A2, 0525.95%-2.890.110.00%5.86%2.56%

T2B2, 9077.05%-2.670.091.57%7.15%1.27%

T2C2, 0343.98%-3.320.130.00%3.93%4.49%

Notes:(1)Acallattemptisascheduledcalltoaparent,9perwave(notcountingrepeatedattemptsandcall backs).(2)Thesharesuccessfulisthepercentageofcallattemptsinwhichtheexerciseswerestarted.(3-4)The posteriormeanandstandarddeviationof βE werecalculatedfromatotalof8,000posteriordrawssampledfrom4 independentMarkovchains.(5)TheprobabilityoptimaliscalculatedasinEq.4.(6)Theaverageprobabilityof successiscalculatedasinEq. ??.(7)Theposteriorexpectedpolicyregretistheexpectedlossfromchoosingthis arm,expressedintermsoftheprobabilityofasuccessfulcall,afterobservingbothwavesoftheexperiment.

“probabilityhighest”foreacharmbasedontheextensivemarginestimates,reportedincolumn(2)ofTable A.7.Theseprobabilitiesaretheanalogoftheprobabilityoptimalincolumn(5)ofTable3(asthesecan becalculatedforanyoutcomeinanyexperiment,regardlesswhetheradaptivesamplingwasused).These probabilitiesneverexceed35.3%.Thepointestimatesandprobabilityhighestindicatethatthesixcall formatsaremuchlessclearlydifferentiatedbasedontheprobabilityof“anyengagement”thanbasedonthe overallcallengagementrate.Thissuggeststhattheintensivemarginmatters,anddifferencesinresponse ratesemergemoreclearlyasparentslearnaboutthecallsanddecideaboutcontinuedengagement. Oneinterpretationoftheresults,comparingAandBarms,isthatlevelingexercisecontentinthissetting isnotvaluable–perhapsbecauseofthenoisyandoftenmissingORFscoresusedforleveling–oratleastnot valuedbyparents,whomayperceivetheexercisesastooeasyortoodifficult.BothCarmshaverelatively lowcallengagementrates.Itisworthnotingthattheoptiontochoosebetweenexercisesincreasesthe lengthofthecall,whichmaydiscouragethelistener.ThecallsuccessrateinT2Cisparticularlylow,and weconjecturethatthisisbecausethelistenerisnotonlyaskedtochoosewhichexercisestoplay,butthe IVRherealsoaddressesthechilddirectly.This“gamification”aspectmayleadtheparenttoworryabout overlylongcallsinwhichthechildskipsaroundbetweenexercises.BetweenT1andT2,theposteriormeans suggestthatT1armshaveslightlyhigherengagementrates,perhapsbecausethe“listennow,practicelater” formatallowstheparentmoreflexibility.

ThesamplingsharesinTable2andthenumbersofattemptedandsuccessfulengagementsinTable3 alsodemonstrateapropertyofadaptivesamplingthatisattractiveinthecontextofpolicychoice:the

reassignmentoftreatmentarmsharesinlaterwavesmeansthatalargerpercentageofparticipantsbenefit fromthetreatmentarmswithbetteroutcomes.Here,thismeansmorestudentsgetIVRcallswithhigh engagementlevels.Attheendofthisexperiment,27.10%percentofstudentsparticipatedinT1Bcompared toonly7.85%inarmT2C.

Eventhoughtheadaptivesamplingalgorithmwasgearedtowardslearningaboutcallengagement,wewould alsoliketoestimatetreatmenteffectsonreadingfluency.ORFmayincreasedirectlyifparentsregularly carryouttheactualexercisesdeliveredwiththeirchildren,improvingtheirreading.Thecallsmayalso increaseparents’awarenessoftheirchild’sreadingabilitymoregenerally,leadingthemtoexpressinterest andencouragereadingpracticeinday-to-dayinteractions.

Table4presentsestimatesfromtwodifferentsamples.Column(1)inbothpanelsshowstheestimated treatmenteffectsonORFscoresusingonlythesampleofstudentswithcompletescoreinformationinall threeexams,whereascolumn(2)usesallstudentsforwhomwehaveatleastonetreatedandoneuntreated examscore.Figure4showstheposteriordistributionsoftheORFcoefficientscorrespondingtoPanelAof Table4,panel(a)forthebalancedpaneldataandpanel(b)fortheunbalancedpaneldata.

Inbothsamples,theORFtreatmenteffectsshowninPanelAaresmallandestimatednoisily,ranging from0.90to1.90correctwordsperminute.Bycomparison,inthecontrolgroup,ORFincreasedonaverage by1.62cwpmand2.92cwpminthefirstandsecondhalfoftheterm,respectively.Overall,goingfrom column(1)tocolumn(2),thetreatmenteffectstendtobeestimatedlarger,althoughwithsimilarcredible intervals;despitethemuchlargersampleintheunbalancedpanel,theprecisionoftheestimatesdoesnot increasemuch,perhapsduetothestudent-levelrandomeffects.Inthebalancedpanel,thecredibleinterval forallsixcoefficientsincludes0.However,theunbalancedpanelestimateforthearmwiththehighestcall engagement,T1B,indicatesanincreaseinfluencyby1.68cwpm,andthecredibleintervaldoesnotinclude zero.NotethatT1Bhasarelativelylargeshareofthesamplebecauseoftheuseofadaptivesampling,and thereforetheeffectonfluencyismorepreciselyestimatedinthisarmthaninothers,eventhoughthemean estimatedORFeffectsareslightlylargerinsomeotherarms.Thelargersamplesizeinthetreatmentarms chosenforimplementationisanadvantageofadaptivesamplingfortheestimationofnon-targetedoutcomes.

Inordertotestwhethersimplyreceivinganycallshasaneffectonfluency,wepoolthesixtreatment groupsinPanelB.Inbothsamples,theHPDintervalsdonotinclude0,andtheeffectis1.31cwpminthe balancedpaneland1.53cwpmintheunbalancedpanel.

Itisworthemphasizingoncemorethatthefluencyestimatesareonlyindicative,becauseofthelow dataqualityandbecausetheeffectsofanytreatmentwouldhavelikelybeenincompletelycaptureddue

Notes:thefigurespresenttheposteriordistributionoftreatmenteffectsafterwave2.Theverticalbarmarksthemedianofeach posteriordistribution.Theshadedareasindicatethe95%credibleintervals.Atotalof8,000posteriordrawssampledfrom4 independentMarkovchainswereused.

Figure4:PosteriordistributionsoftreatmenteffectsforORFscores. totheshortexposureandtheone-offmeasurementofORFimmediatelyaftertreatment.Thatsaid,the estimatessuggestthatanIVRinterventionforparentalengagementintheirchildren’sreadingwillhavea positiveimpactonchildren’sreadingskills.Thisisanencouragingfindinggiventherelatively“lighttouch” ofthisintervention.Basedontheestimatesfromtheunbalancedpanel,itismorethan95%likelythat implementingthearmwiththehighestengagement,T1B,whichasksparentstocarryoutafewsimple readingexercisessequencedthesameforallchildren,willleadtopositivereadingfluencygains.Whilethe effectsofthe4.5-weekinterventiontestedhereweremoderate,itstandstoreasonthatexposureforthefull termoreventhefullschoolyearwillgeneratelargereffects.Theprogrammayalsoleadtocontinuedjoint readingbetweenparentsandchildrenafterthecallsend.

Aremainingquestionishowthetreatmenteffectsonfluencycomparebetweenthedifferentarmsand whethercallexposureandefficacyvarysignificantlystronglysothatoneofthearmswithlowercallengagementcouldbemoreeffectiveforreadingoutcomes.Unfortunately,theanswerishamperedbythequality ofthedataandtherelativelysmalleffectsizes.FromFigure4,thereissignificantoverlapinthecredible intervalsofallarms,evenforthetreatmentarmswithalargeshareofobservations.Togetasenseof theuncertainty,TableA.4inAppendixCshowsthe“probabilityhighest”andtheexpectedregretforeach armbasedontheposteriordistributions oftheORFmodel.TheprobabilitythatT1Bleadstothehighest possiblereadinggainsamongthesixarmsliesbetween12%and20%accordingtotheseestimates.T1B generatesaposteriorregretof0.94cwpminthebalancedpaneland1.14inintheunbalancedpanel.Inthe balancedpanel,T1Bisthearmwiththelowestposteriorregret.Intheunbalancedpanel,armT2Bhas thelowestposteriorregret,with0.92cwpm.WhiletheprobabilityoptimalishigherthanforT1Bforthree arms(T2A,T2B,andT2C),itisbelow26.3%forallofthem,andthedifferenceinexpectedregretisless than0.24cwpm.

Thelowprobabilityoptimalforthearmswithlowestregretreflectsthenoiseintheseestimates.Notealso

Table4:ORFscoresestimates.

PanelA:Treatmenteffects

BalancedPanelUnbalancedPanel (1)(2)

(Constant)46.90∗ 46.54∗ [43 98;49 92][43 76;49 31]

T1A0 901 29 [ 1 26;3 09][ 0 70;3 30]

T1B1 601 68∗ [ 0 04;3 26][0 13;3 21] T1C1 080 91 [ 0.72;2.92][ 0.79;2.59]

T2A1.401.85 [ 1.01;3.81][ 0.42;4.04]

T2B1 411 90 [ 0 75;3 55][ 0 12;3 92]

T2C1 321 79 [ 1 06;3 71][ 0 49;4 05]

PanelB:Pooledtreatmenteffects

BalancedPanelUnbalancedPanel (1)(2)

(Constant)46 91∗ 46 63∗ [43 87;50 02][43 77;49 49]

Pooledtreatment1.31∗ 1.53∗ [0.08;2.52][0.34;2.69]

Num.obs.54696701 Num.students18232439

Notes:Reportingmeansand95%HPDintervals(insquarebrackets)of theposteriordistributionsoftreatmenteffects. ∗ :zerooutside95%credibleinterval.Wesimulate4independentMarkovchainsof4,000posterior drawseachanddiscardthefirst2,000aswarmup.Theremaining8,000 drawsareusedtogeneratetheposteriordistributionsofthecoefficients. TheSplit-R ofeverycoefficientisbelow1.01andtherearenodivergent transitions.

thatT2AhasahigherprobabilityoptimalthanT2Binboththebalancedandunbalancedpanel,highlighting thatthearmwiththehighestprobabilityoptimalmaynotalwayshavethelowestpolicyregret.Thiscan occurifsome“unlikely”statesoftheworldhaveveryhighregretrealizationsandoccursmoreoftenwhen thebestarmisfairlyuncertain.

Overall,basedontheseresultsthereissignificantuncertaintyaboutwhicharmhasthehighestORFgains. Thereisnostrongevidencethatchoosingapolicybasedonmaximalcallengagementissystematicallyat atensionwithalsoincreasingoralreadingfluency,butwecanalsonotconcludethatthetwooutcomesare definitelyaligned.Iftheimplementerwouldliketorevisethedecisiontotargetengagementonlyandlearn whichcallformatmaximizesORFgains,additionaltestingwouldlikelybeneeded.