6 minute read

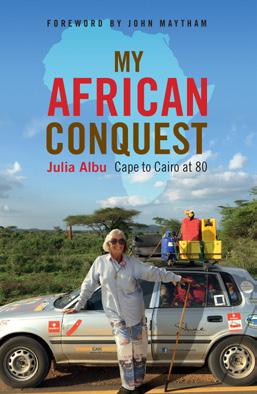

MY AFRICAN CONQUEST: Cape to Cairo at 80

80-year-old Julia Albu is an adventurer with a difference – she’s an octogenarian. At an age when most people are happy to put up their feet, Julia drove south to north across Africa in her trusty Toyota Conquest she named Tracy.

Her adventure began when she called in to her favourite radio show with a zany, half-baked idea: “Next year I’m going to be 80 years old. My car will be 20 years old. Together we’ll be 100. We’re going to drive to London.” At the time, she had no idea that it would lead her to the adventure of a lifetime.

“And what route are you going to take?”

“I have no idea. I think I’ll keep to the right.”

From helping push a 30-year old Toyota bakkie up a precipitous mountain pass in Malawi to being “adopted” by the riotous ex-pat

South African community in Dar es Salaam and being fed mildly hallucinogenic “herbs” by her Ethiopian driver-guide, nothing deterred 80-year-old Julia from her quest to drive through Africa from the Cape to Cairo.

She travelled through 10 African countries, from South Africa to Egypt (and beyond). Julia was accompanied by a series of companions who added texture to her travels: three of her four grownup children, her son-in-law, and at least one person who began as a complete stranger and ended up as a friend for life.

Reminiscing about her long and interesting life along the way, and maintaining a bright and upbeat outlook regardless of the circumstances, Julia proves that you’re never too old to tackle that bucket list.

In this excerpt, Julia recounts her journey from Bahir Dar to Lalibela, Ethiopia, with her maverick guide, Lucky.

23–29 NOVEMBER 2017

Lucky continued to be a challenge, doing things like suddenly stopping the car and jumping out, then getting down in the middle of the road to do push-ups; he constantly made muscles and yelled at me to take photos of him (‘Look at me! Very handsome!’), rather like a child trying to get attention, and if he saw that I was more interested in our surroundings, he would literally jump right in front of my face to get my full focus.

Another of his whims was to stop in some of the smallest and busiest villages, then leave me in the car while he went off and had coffee with (I assume) friends or family members. Then he’d jump back in and roar off down dirt roads in clouds of dust, with me holding my knees and yelling, ‘Stop, Lucky!’

While Lucky drove, wafts of dagga waved over me, giving me that giggle you get from sitting next to someone who starts his day with it, although Lucky kept insisting that I was the high one. At one point he even accused me of drinking – I am generally as sober as a judge, and in fact our whole family seldom touches alcohol (aside, of course, from what goes into our Christmas pudding and the accompanying brandy butter). When I asked him outright, ‘Lucky, what are you smoking?’ he told me it was a medicinal herb, and even got me to chew on some hedge or other. I think I did get slightly high then, which I didn’t notice until he encouraged me to walk along a wall overlooking a valley miles below. Thinking back, I suspect we were both high for most of the time, actually.

Again and again, on the 310-kilometre drive to Lalibela, I regretted not having someone with me (but not Lucky!) with whom I’d be able to share the experience without having to say a word. Every inch of the mountain passes and the plains seemed to be under sorghum; I never knew it grew in so many colours, from shades of white to autumn hues. Below in the valleys were clusters of houses. Trains of donkeys loaded with hay were guided by women and children carrying their own bundles, while schoolchildren made their way through the dust in their pristine uniforms. In some cases, the donkeys were more heavily laden than any I’d never seen – I was ready to phone the SPCA but one of my hosts assured me that although the people worked the donkeys hard, they were looked after. The people in this beautiful country also worked harder than anything I’d ever seen, with the children being taught from about the age of seven to tend to the cattle.

They had a brilliant system, where the younger children went to school in the morning, and in the afternoon learnt about tending to the animals, while the older children did the opposite. In this way, everyone got an education and also learnt to take care of a family. Apart from the frequent tea stops, we shot on. At one stage we saw winding down the road towards us a group of women with such amazing hairstyles that we screeched to a halt and I (sort of) leapt out of Tracy frantically waving suckers, pens and chocolate biscuits. They shyly came over to us and although we couldn’t really communicate because of the language barrier, we quite happily got along in smiles, the international language of friendship.

One of the women was carrying a rather grubby-looking bundle which she lay on the ground and opened, producing some rather unsavoury-looking edible. She indicated that she wanted to share it with me. Not wanting to be rude, and with knees crackling like a breakfast cereal, I crouched down and, to surrounding applause, ate god knows what. Somewhere along the road Katherine had booked us into a church hostel. Staying in the monasteries in Ethiopia was wonderful – they were warm and safe, and with hot running water. And of course every church was decorated with abundant and colourful murals, frescos or paintings. This one, although very spartan, was very clean. It was full of backpackers, so I was shown to a small but clean room with a balcony looking at the mountains. I was told that there was a gentleman waiting for me and went downstairs to find a good-looking man with lovely manners who introduced himself as Professor Abebe Zegeye. He lived in the relatively nearby town of Woldia with his partner Rachel Browne, who was originally from Cape Town, he told me, and he invited me to stay with them there.

The next morning I came down and found Professor Zegeye sitting waiting for me again, but this time with three of his learned colleagues. They’d heard I had a problem, these wise and earnest men told me with quiet concern; they had heard that I needed something sorted out.

They were the most cosy, charming men who would do anything to help a damsel in distress (that damsel being me). They were to become my guardian angels and as such I christened them Matthew, Mark, Luke and John. I poured out my heart to them, telling them of my problems with and concerns about my guide, Lucky.

The solution, they said, after much backwards and forwards between the four of them, was to simply pay him what I owed him, plus his bus fare back to Addis Ababa. I agreed, but I didn’t want to just sack Lucky, because the bush telegraph was frighteningly efficient and I had my reputation to look after; and, anyway, I needed him to get me to Woldia.

So I was stuck with my troublesome guide for the time being. •

READER GIVEAWAY Silver Digest has two copies of Julia Albu's My African Conquest: Cape to Cairo at 80 to give away to our readers. To stand a chance to win one, send an email to info@silverdigest.co.za with My African Conquest in the subject line.