Vol. 1 Issue 3 New York London Hong Kong Philippines

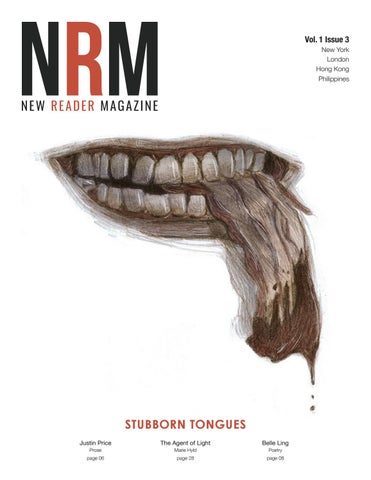

STUBBORN TONGUES Justin Price

The Agent of Light

Belle Ling

page 06

page 28

page 08

Prose

Marie Hyld

Poetry

Vol. 1 Issue 3 New York London Hong Kong Philippines

STUBBORN TONGUES Justin Price

The Agent of Light

Belle Ling

page 06

page 28

page 08

Prose

Marie Hyld

Poetry