5 minute read

Gyppos

JON KEMSLEY

They had already pitched up by the time I arrived on Monday and so I missed the drama of their forced entry. I’d been phoning round all morning for a gardener after some rather pointed remarks from both sides and I was running a little late. “We have new neighbours,” says Mandy. “Come and see.” I looked down and saw two enormous caravans, a large truck, a smaller truck, and a rusty hatchback with one of its hubcaps missing. There was a dog tied to a signpost and, off in the far corner, another dog asleep on a blanket. Three or four adults engaged in a vigorous discussion and four, maybe five, children running around shoeless in the dirt.

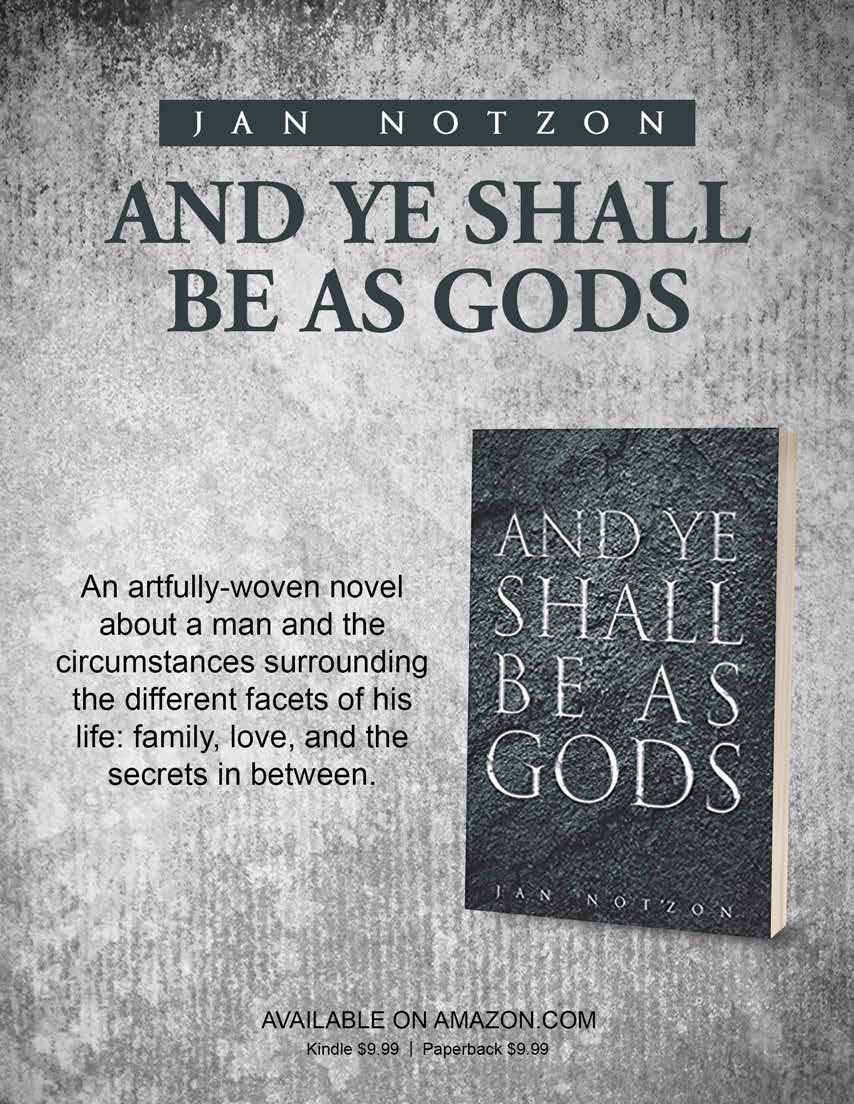

Advertisement

“Mummy, mummy,” says Bob, pawing the window, “it’s the circus.”

“It’s disgusting,” says Sue. Sue is having an affair with Tony who is married. She shakes her head. “It shouldn’t be allowed.” “But it’s not,” says Tony. “Yes, well, it shouldn’t be. That’s all I’m saying.” Sue slaps Tony on the arm.

“Breeding like rabbits,” says Philippa, who has three of her own. “I know, it’s disgusting,” says Sue. My phone was on the desk beside me for the rest of the day as I struggled to meet deadlines. I’d left messages with several companies but nobody was calling me back. And so it went. On Tuesday we observed our new neighbours rolling empty oil drums across the concrete to clear a parking space for one of the trucks. Nobody could remember where the oil drums had come from but there were certainly a lot of them. We looked down and disapproved. “Where’s the pony?” asks Sue suddenly. “What pony?” asks Tony. “There was a pony. A little one.” Sue raises her left hand just so high. “There wasn’t a bloody pony.” “There was. It was on the back of one of the trucks.” Tony sniggers. “Maybe they had it for breakfast.” “Don’t be horrible,” says Sue. The pony eventually appeared from behind a clump of bushes and trotted over to the children to be petted. The weather was holding and the adults were busy setting out deck chairs and canopies and cooler boxes. On Wednesday we saw them swing the larger of the caravans around on its wheels to move it into the shade of our office block. The children hugged themselves and jumped up and down as the men heaved and spat and the women crossed their arms and pursed their lips.

“I walked past there earlier,” says Philippa, spraying herself with perfume. The perfume carries her perspiration across the office. “Terrible smell.”

Tony frowns. “You can’t smell them from the street.” “Okay, no, but it looks pretty smelly in there.” Philippa winks at Mandy. “Not the sort of thing you’d want to live next door to.” “How’s your garden coming along?” asks Mandy. By now I’d received calls from two firms both of whom were unable to offer the kind of clearance I had in mind. A third had messaged with a figure I was unwilling to part with and a note suggesting that I’d be very lucky to et cetera et cetera. There had been more comments over the fence and the situation was starting to wear me down. Thursday arrived without incident but the topic of conversation had not changed.

“It’s not a campsite,” says Bob, “it’s a scrapyard.” Bob works on cars in his spare time and has one up on bricks outside his house. “Nice,” says Tony. “I wonder how long they’ll last.” “What do you mean?” asks Sue. “Before they get moved on.” Tony shrugs. “Sooner or later they always get moved on.”

“Leaving their mess behind,” says Philippa. “And one or two kids,” says Bob, poking Philippa in the ribs. Mandy is back at the window. “Oh, look, something’s happening. Come and see.”

Something was indeed happening. The adults were folding chairs and carrying them back into the caravans and the children were running about gathering up their toys. An older man with his shirt open to the waist appeared to be directing the operation. Soon all of the various items consisting a life on the move had been packed away and everyone was inside with doors and windows closed. One of the girls ran back out to retrieve a doll and then disappeared inside the smaller caravan.

“They had a fire going last night,” says Tony. “And pop music.” He scowls. “Bloody racket.” Tony owns a large pair of speakers and an extensive collection of heavy rock records. “Mind your language,” says Philippa. “Your kind of people,” says Bob. “Invite them over for dinner.” Tony frowns. “Not bloody likely.” “Language,” says Philippa. A couple of minutes later a blue van with an orange light on its roof trundled up a side road and onto the broken tarmac. It circled round and came to rest in front of the caravans. The window on the passenger side was rolled down as the older man with the open shirt emerged from one of the trucks. He waved his arms about and then shrugged and pointed off in the direction of the gate. The window was rolled back up and the van circled slowly back round before departing. “Told you,” says Tony. And then they were gone. The plot would remain unsold for the next eighteen months, by which time it would have established itself as a popular site for dog-walking and fly-tipping. And my neglected garden would come to resemble a wildlife sanctuary: ivy climbing the brickwork to trouble the adjoining properties, sparrows darting into the brambles for insects that buzzed and settled, larger creatures rustling unseen in the tall grass. I would eventually get around to having it all paved over.

Jon Kemsley has been published in Ellipsis, Ginosko, the Fiction Pool, New World Writing, Neon, and others. He lives and works on the south coast of England, listens to old jazz records, and occasionally remembers to call his brother about whatever it was he promised to do the last time.