Beirut’s Iconic ‘Egg’ Cracks Open!

Abstract

This newspaper edition is distributed in honor of The Egg, a landmark near and dear to many generations of Lebanese. It familiarizes the unfamiliar with the life story of this iconic building, preparing them for its revival. Through archival images, testimonies, in-depth research, and opinions, readers will embark on a journey of rediscovery of a beloved war-era monument.

This accompanies a larger Capstone project, which focuses on the adaptive reuse of the iconic building. As readers navigate through the various articles, they will develop a sense of closeness to The Egg, becoming sympathetic to its life experience. They will learn about the importance of preserving the memories that structures such as The Egg and others alike hold.

One will come to understand how the adaptive reuse of The Egg not only honors its historical significance but also transforms it into a vibrant community space, bridging the past and present while fostering a collective sense of identity and resilience.

By considering events of the past, we can better understand the future, create the vital form through the vast reservoir of memory, and transform the narrow boundaries of lived experience into wider environments of shared experience.

Inside today’s SCRAMBLE

Abstract • Growing Up Beirut • An Open Wound • ‘Save the Egg’ • Cracking the Egg • Memory is Absolute • Golden Days Gone • Towards an Architecture of Memories • A Word From the Designer • Opinion • Reviews • A whole lot of great images!

Growing Up Beirut

For the curious kid looking out the window

Lebanon. It’s home to a spirited population and some of the world’s natural and cultural wonders, universal generosity and a fervent desire to pour olive oil on everything. The country, one infamous for its involvement in modern conflict, has constantly promised me refuge, community, and home, of the type unrivaled elsewhere. Growing up in the capital, Beirut, meant that traffic was no stranger, but rather a chronic circumstance that came to foster an obsession with people-watching, building-gazing, and wondering about the story behind each bullet hole in every old, worn facade. Said daily musings are what exposed me to Lebanon’s urban landscape of buildings, both old and new, while encouraging me to look inward for this research; as a child, I recall plenty of time spent in Martyr Square’s Place Des Etoiles, a cobblestoned space where children rode their bicycles and market vendors sold Lebanese souvenirs and delicacies. As time went on, I watched its perimeter turn into a construction zone, with buildings being demolished and built anew, much like the memory of what once was. Today, Place Des Etoiles is a redefined ghost town of societal abandonment. Watching this landscape be reengineered instilled my newfound curiosity in one of the site’s defining features, popularly known today as the Egg.

The Egg is a living testament to the complex and under-documented history of Lebanon, at least in recent times. With many stories about the Civil War transmitted through word of mouth by older generations to younger ones, they become layered with biases and preconceptions and grow further and further

from the truth, while the ongoing gentrification of Beirut despite climbing poverty rates is compounding the erasure of Lebanon’s heritage, both physical and intangible.

Lebanon’s war-torn landmarks undoubtedly shape the country’s divided historical narratives, especially regarding its 15-year Civil War. In Beirut, architecture offers a tangible account of political events and conflict, as its buildings hold individual and collective memories, and tell stories of the city’s people and governments. Although some may argue that the preservation of war-era landmarks is essential for honoring historical memory and promoting reconciliation, the adaptive reuse of war-torn buildings presents a middle ground and an opportunity for designers to help reconstruct ambiguous historical narratives, aid others in understanding how memories are experienced in the built environment, and encourage people to rightfully reclaim public space. The Egg is used herein as a case study of a war-torn structure that, given its proximity to defining political events of Lebanon’s history, could serve as a medium for a commemoration and honoring of the past as well as for envisaging a way forward.

Photo from ground floor of The Egg by teongeron91

Photo of author and their mother in lively Martyr’s Square, 2003

Atmospheric rendering of the Egg basement by author

An Open Wound

In the heart of Beirut, Lebanon near Martyrs’ Square, a place so full of life it was on every postcard, sits a peculiar building. A relic from what might feel like another world. Built as a cinema between two large towers, all three comprising what was meant to be the largest mall in the Middle East, the City Center.

Its walls decay, but if those walls could speak…

Any person who takes a close look can read my story in every crack, hole, and crevice. Once upon a time, I was filled with tears and laughter. Men and women alike would come, fill up the bleachers in my soap-shaped interior, and marvel at the latest in cinema. You still can see from the carvings inside my shell where the screen used to be. It wasn’t there for long. Soon after my opening, war took over. The laughs stopped and were instead replaced by tears.

As you can see from the hundreds of bullet holes piercing my exterior, my tough shell was perfectly suited to protect our soldiers. Some would say my brutalist design was in fact a preservative cover. At some point, when Bechara el Khoury street became the ‘Green Line’, life as we once knew it had changed suddenly. The city center, once vibrant and full of life, turned into a no-man’s land. I was not fated to just be a strange Egg, right in the middle of where East and West Beirut meet. With no allegiance except to those who shelter inside me. I was scarred. The platforms that carry me crumbling at the edges. The levels underground beneath me flooded.

The war passed. I remained erect. So did my neighboring tower. But as the privatization of Downtown Beirut began, my fate became unknown. You can tell when you look at my southern facade. You question how it is so perfectly vertically sliced. You start to wonder what was there before, and where it went. It was simply demolished. My connecting tower, which bore witness to my whole life, was stripped away from me, leaving me incomplete. I stood alone. Now an even more peculiar thing, oddly shaped, in the midst of what was turning into a neighborhood for the rich and elite. Eventually, my facade was boarded up.

Following years of controversy surrounding the ongoing reconstruction/gentrification of my neighborhood, my time inevitably came.. I had accepted my fate. Uninhabited for decades. Forgotten, I thought. Yet the threat of my demolition troubled some. A campaign in MY name. ‘Save The Egg’. And that they did.

Years and years of standing idle. Watching as my neighbors got restored, as new shiny buildings began to pop up, as former battlefields turned into spaces of joy and gathering, and as heavy construction suddenly sounded like ‘Allahu Akbar’. Yet I remained. As I’d been for decades.

There were moments when I felt little rushes, like when they held art exhibitions. It fueled my soul. When rebels would sneak in, using my cold concrete interior to host their gatherings, their spirit, like the candles they’d bring, lit me up inside.

Suddenly, I felt a bigger shift. A collective pulsation of the hearts of those who took to the streets demanding justice.

‘Save the Egg’

Their violence did not hurt me. Not when they kicked off my boards. Not when they stepped all over me, under me, inside me. Not when they covered my exterior in graffiti. Not once. I was proud to be the ground on which they could stand. Depend on. My facade, now fully exposing my platforms, became a coveted spot during the 2019 Revolution. My roof, a panoramic view of the masses. My walls; canvases for expression. For artists to paint the feelings that their words can’t capture. A permanent, physical testament of their resistance, their discontent. They even coined a term; the ‘Eggupation’.

Lectures, meetings, exhibitions, and parties, all began taking place. I was given a new purpose. A purpose attributed to me not by my architect, but by my occupants.

Then came 2020. Pure, total destruction. Hundreds of thousands left homeless. A city in ruins. No (functioning) government to pick up the pieces. No justice for victims and their families, four years later. Their scars – physical and emotional – persist, whereas mine aren’t so visible. For years, I’ve been decaying. My color, fading. My platforms, crumbling. With all that, I stood. That pulsation I mentioned – it quickly died. A country, known for its resilience, left hopeless.

Now, I feel frozen in time. Nothing happened. Nothing seems to be happening, will anything happen? With the country? With me?

When you see and experience all that I have, you inevitably learn that good or bad, change is a constant. I, myself, have not changed. I have simply aged.

Photo by Anthony Saroufim showing the impact of bullets on the exterior shell of The Egg, 2015

Cracking The Egg

The construction of the Egg was interrupted by the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War in 1975, a deeply sectarian one that remains a taboo topic but also continues to permeate several aspects of Lebanese society. Children do not learn about the war at school as there are no official, reliable accounts of its events, and yet the militias that were formed during it persist in their hold over the country, although in a thinly veiled attempt to paint themselves as legitimate political actors.

For over ten years, the Egg was in the front row of the demarcation line, also known as the Green Line 1), which marked the site of a 15-year conflict between Muslim and Christian communities in East and West Beirut. Thousands died, and much of Beirut’s infrastructure was destroyed. Many of the concrete buildings in the city were converted into makeshift bunkers. After old Beirut was destroyed, the Egg was, inexplicably, the last building standing in the wreckage, emerging as a symbol of resilience and a sentimental relic of Lebanon’s prime years.

During country-wide protests in 2019 and 2020 in response to a multi-pronged crisis, academics, artists, and activists made use of the Egg as a center for dialogue and communal learning which sparked hopes for a revival of the

space that is untainted by political or religious affiliations. However, there was no such revival. In an increasingly worsening socioeconomic climate, activism fatigue took over, and the discontent experienced by demonstrators is immortalized (for now) through protest slogans scribbled and graffitied on the walls of the structure (fig.3).

The Egg is only 1.43 kilometers from the epicenter of the August 4, 2020 Port Explosion in Beirut, which was deemed “one of the most powerful artificial non-nuclear explosions in history.” The blast’s radius reached up to 10 km and completely destroyed the surrounding neighborhood, yet once more, remarkably, the Egg was spared with little to no visible damage.

Since then, it has remained devoid of human contact as the population’s hopes have been destroyed once more. This was brought on by the country’s circumstances getting worse and a dire economic crisis. The Egg has been reused by the current socio-political scenario, serving as both a window of hope for a contemporary and revolutionized Beirut that is currently empty, and a reminder of the horrors of Lebanon’s past.

Golden Age Gone

After the Civil War, the severely damaged Egg remained intact but inaccessible to the general public, as if it had been frozen in time. Local government officials and developers threatened to demolish the Egg several times every few years, but activists constantly intervened to save it, launching various campaigns like 2009’s “Save the Egg” initiative to encourage its conservation and repair. In her book “The Insecure City: Space, Power, and Mobility in Beirut,” Kristin V. Monroe observes that the large-scale postwar reconstruction of Beirut’s city center inadvertently erased more architectural and historical ruins than almost two decades of fighting, which underscores the challenges of reconciling the past with the present. She claims the quote, “They’ve rebuilt the stones but they have not rebuilt the people,” resonates with the popular sentiment that postwar reconstruction prioritizes infrastructure and profit over social repair.

In a similar vein, Aseel Sawalha, cultural anthropology professor, outlines the public opinion of two groups who were, for all intents and purposes, “excluded from [participating] in defining the future of the city” – the first group, which consisted of “intellectuals, historians, architects and social scientists,” had some power in voicing and conveying their discontent. The second, less powerful group, which included “displaced families, local residents, and long standing tenants,” also voiced their opposition, but, ultimately, both groups stood powerless against government control and enforcement. The city center turned into “an empty space, a placeless space, and a hole in the memory” as described by Elias Khoury, a Lebanese writer. Salwaha notes that “city residents were incapable of protecting one of their childhood sites but insisted on witnessing, documenting, and mourning its destruction, [with the] publication of these nostalgic accounts in daily newspapers [allowing] personal narrative to

enter the public sphere and [transforming] private memories into acts of collective remembering.”

Through her recounts of public reaction, it becomes apparent that even the deconstruction of the built environment can create a coming-together of memories, which in turn helps solidify the historical narrative around what might soon disappear.

A key player in the rebuilding of Beirut after the war was Solidere, which came about after the Lebanese government turned to a private real estate holding company that was granted expropriation rights over central Beirut. This was a controversial, unprecedented development in Lebanese history, and some denounced the company’s actions as an unlawful infringement on property rights. “Writers deemed Solidere responsible for the dismantling of Beirut’s past and for the erasure of its residents’ memories.” Indeed, citizens expressed “the common concern that Solidere’s plan was designed as if the area had no history, and its residents had no emotional or spatial attachment to its urban spaces.” Through this, we can understand how the reconstruction of post-war cities often neglects the most valuable input, which tends to be the ones of the people.

In examining the layers of Beirut’s architectural history, insights from scholar and urbanist Robert Saliba into a revised master plan to be implemented by Solidere in his article about Conservation Design Strategies in Postwar Beirut become significant, with the Egg having been included as one of the retained buildings. The master plan 4), revolving around visual, physical, and functional permeability, adds a layer of complexity to the Egg’s significance, placing it within the larger context of Beirut’s urban planning.

Memory is Absolute

In the intricate dance between memory, history, war, and architecture, Beirut emerges as a focal point where they all converge, contributing to the shaping of the city’s narrative and identity. As French historian Pierre Nora has suggested, “memory and history, far from being synonymous, appear now to be in fundamental opposition.” While memory seems to be rooted “in the concrete, in spaces, gestures, images, and objects,” history seeks to distill the past into a coherent narrative – in other words –“memory is absolute, while history can only conceive the relative.” Beirut bears witness to this dialectic, where buildings like the Egg serve as tangible stores of memory amidst the ambiguity of history. Thus, the adaptive reuse of war-torn structures becomes paramount in anchoring collective memory in the present physical landscape. These structures, filled with the reverberations of previous existences and conflicts, provide a contrasting perspective to the ceaseless progression of time.

They take on the role as conduits for the social histories of their neighborhoods and surrounding communities, changing in tandem with the everyday rhythms of the city. These structures, with their roots deeply embedded in warfare, stand as testament to resilience and endurance. The adaptive reuse of such

buildings transcends mere preservation; it is an act of defiance against the erasure of memory, a reclaiming of rootedness amidst flux. In a chaotic landscape like Beirut, the adaptive reuse of war-torn buildings becomes not only a means of architectural revitalization but also an intentional, deliberate act of remembrance, forging a link between past and present, memory and history.

Additionally, Lebbeus Woods, an unconventional and experimental architect and artist, establishes a critical dialogue around the devastation caused by war and subsequent principles guiding post-war reconstruction. Woods emphasizes the inadequacy of merely restoring cities to their pre-war state, pointing out the impossibility of returning to a ‘normal’ that has been irrevocably dismantled. Woods has studied the connection between architecture and socio-political developments and stresses the significance of preserving historical embodiment while addressing existential remnants of the war, saying that “the post-war city must create the new from the damaged old. This echoes the Egg’s evolution from a recreational center to a socio-political hub and site of resistance, challenging the notion of reverting to the pre-war status quo.

Towards an Architecture of Memories

Nowhere has [the Lebanese Civil War] been a more central concern than in the arts. Architects and urbanists have debated the role of architecture, urban design, and heritage preservation in healing the wounds of war.

Lebanese photographer Anthony Saroufim’s project, which envisions the transformation of the Egg into a colossal camera obscura, is a captivating exploration of the intersection between architecture, history, and photography. His project serves as a compelling visual narrative that delves into the essence of the Egg as a witness to Beirut’s complex evolution. Saroufim’s approach recognizes the building as an active participant in the city’s unfolding chaos, becoming resigned to various roles throughout its existence. By utilizing existing bullet holes as optical devices and integrating magnifying lenses into the damaged areas, Saroufim transforms the scars of war into a visual connection with the past 5). It seamlessly integrates the transformation of architecture with the preservation of authenticity, the scars of war, and a historical narrative, offering a unique perspective on the Egg’s role in Beirut’s ever-changing story. This emphasizes the importance of the role we [designers] play in projecting our collective memories, consciousness and cityscape.

Spectators at The Egg Cinema via An-Nahar newspaper

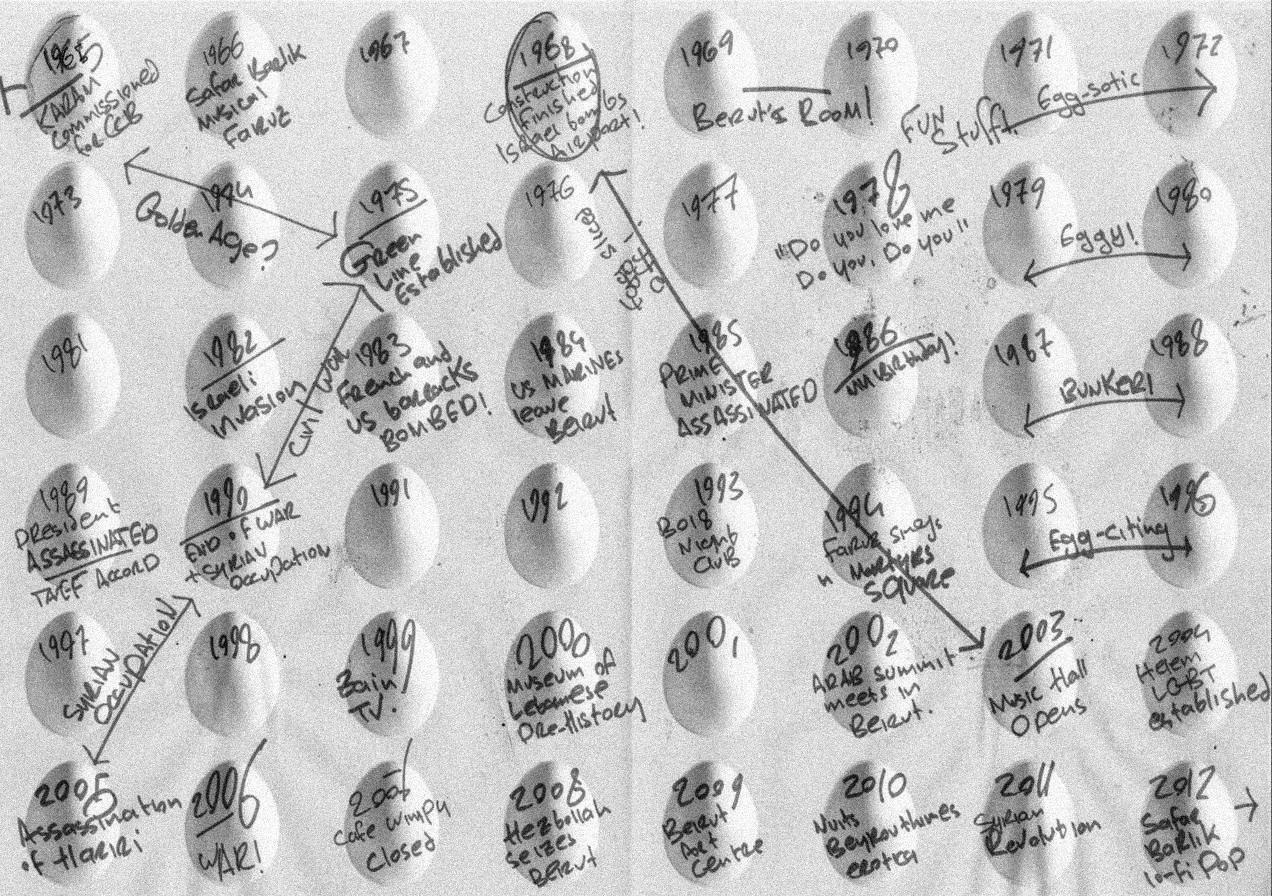

Illustration of the historical timeline of The Egg by Khaled Sedki

Martyr’s Square during an Independence Day paravde revolution, 2019 via Atlas Obsucra

The journey of the Egg allows us to grasp the differences between preservation and adaptive reuse in navigating Lebanon’s complex historical narrative. While the preservation of war-era landmarks holds significance in honoring memory and fostering reconciliation, the Egg’s evolution demonstrates the potential of adaptive reuse to bridge the gap between past and present.

As we continue to grapple with Beirut’s layered history and the challenges of post-war

reconstruction, the Egg serves as a compelling reminder of the need for creative approaches to heritage preservation. Its transformation into a space of activism and contemplation underscores the power of architecture to facilitate dialogue and community engagement.

Looking ahead, the Egg invites us to explore new possibilities for commemorating the past while embracing the dynamism of the present. As Beirut continues to evolve, the Egg stands as a beacon of resilience, sparking conversations

about memory, identity, and the transformative potential of architecture in shaping our shared future.

This essay is an invitation for people to see war-torn buildings not solely as a reminder of destruction but as an opportunity for progress and the comingtogether of communities for a collective remembrance of the past.

From the Designer

What to expect

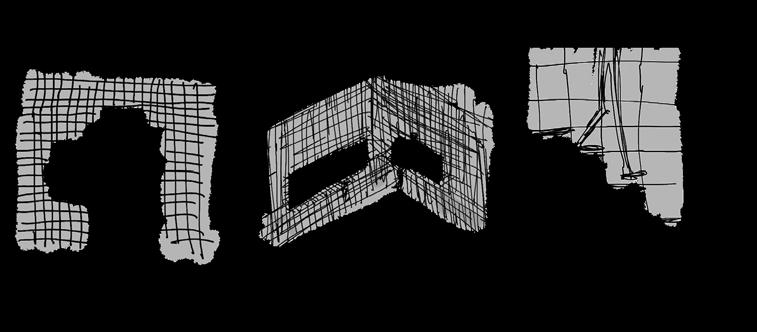

This project embraces the potential for adaptive reuse of war-torn infrastructure while paying homage to the historical significance of the Egg, an unfinished cinema building in Beirut, Lebanon. Rooted in the building’s war-era narrative, the design proposed herein seeks to breathe new life into its spaces, simultaneously honoring its past and envisioning its future.

Central to the design approach is the transformation of the Egg into a community space where not only is its original function as a cinema reinstated, but its prior utilization as a space for clandestine nightlife is also legitimized. Both of these programs are carried out through a versatile three-dimensional

grid system, akin to scaffolding. The grid’s adaptability allows for fluid reconfiguration, respecting the authenticity and architectural integrity of the structure while accommodating diverse functions and serving as a testament to the building’s resilience amidst societal and political turbulence.

By day, the space caters to the diverse needs of the community, while by night, it transforms into a nightlife spot that deviates from the growing trend of VIP rooms, bottle service, and guest-list-only venues in the city. Within the Egg’s walls, partygoers share an experience of cultural and sonic exploration that knows no hierarchy or special treatment, a significant

occurrence in a country where “wasta” (the closest English translation of which is “nepotism”) runs rampant.

The materials for the project are consciously selected, reflecting Lebanon’s resourcefulness and resilience. Recycled glass, salvaged from the debris of the 2020 explosion, adorns the nightclub’s roof, symbolizing renewal amidst devastation, while the labyrinthine nature of the grid system invites visitors to lose themselves in the structure, fostering a sense of discovery. Symbolically, the labyrinth also embodies the project’s ethos — a testament to the intricate layers of history and culture waiting to be unearthed within the Egg’s enigmatic shell.

Opinion

How should we design?

Starting a design project means starting an obsession.

An obsession grounded on discovery.

Becoming so enthralled by those discoveries that they may become more interesting than the project itself.

I believe that any ‘good’ design must bloom from a seed planted during the ‘obsession phase.’ Whatever form that obsession may take.

A meticulous study of the all-encompassing whole provides an opportunity for a part to stand out. That part is the seed, and it is rarely a given.

Every built entity has many layers beneath what the eye can see, and it is our job as designers to unearth those layers and amplify them.

An obsession creates intention.

Intentionality is the basis of design.

A designer must make choices.

A choice without intention is not a choice, it becomes convention.

From all that I’ve learned, the most elemental thing is that I learned how to see.

We are not just designers. We are researchers, explorers, and adventurers. We must wear all our hats.

We are not the drivers. We are the vessel.

DAILY HOROSCOPE

Aries(March 21-April 19): With Mars energizing your sign until June 9, you’ll be driven to turn your dreams into reality. Focus on creating a solid plan to manifest your vision effectively. Be mindful of how you assert yourself, ensuring you don’t inadvertently alienate others on your path to success.

Gemini(May 21 - Jun 19):

Embrace a surge in team spirit. While you may desire to connect with everyone individually, remember, your network is your net worth, so curate your social interactions wisely. Be mindful of your social media activity; aim for posts that inspire rather than provoke, avoiding rash decisions that could lead to unwanted attention.

Leo(Jul 23 - Aug 22):

Embrace adventure, Leo, as Mars ignites your ninth house of expansion until June 9. Seek out new experiences and opportunities for growth, whether through travel, learning, or mentorship. Embrace your restless spirit with courage, but remember to make well-calculated decisions rather than impulsive ones.

Sagittarius(Nov

Taurus(Apr 20 - May 20): Listen to your body’s signals at this time. Prioritize your well-being over social obligations; it’s okay to opt for solitude when needed. Engage in activities that nurture your spirituality and creativity. Allow suppressed emotions to surface, and confront them with courage and compassion. Avoid unhealthy coping and focus on healing from within.

Cancer(Jun 21 - Jul 22): Get ready to make your mark, Cancer, as Mars ignites your ambition and drive for success until June 9. Take advantage of this fruitful phase to pursue your professional goals with determination. Stay focused on your own path and avoid getting distracted by competition. Keep pushing forward.

Virgo(Aug 23 - Sep 22): Make a decisive move, Virgo, as Mars energizes your eighth house of intensity until June 9. In all matters, you’re ready to commit wholeheartedly

Scorpio(Oct 23 -

“It was our third date, the last time we walked into this big concrete shell. I still remember the movie that was playing. I never imagined I would come back. We are going into our fifty third year of marriage, entering it with the fondest memories of our past through the revival of this space that was so near and dear to our hearts. Although it looks so different, the energy and atmosphere that exists inside the Egg is unlike any other. I will admit, I normally have an aversion to these renovation projects, because they never quite understand the significance of the space. I’m not sure how to describe it, but it felt like it was still under construction. We took our seats, had a great laugh, and walked out feeling like our younger selves, falling in love all over again for the first time.”

Leila, 80 years old.

“It was crazy!!! I think I lost myself over 10 times in that maze. Then I kept on noticing that one column with the trippy graffiti, so every time I got there, I knew I was getting closer to the bathroom. I felt like I was in three places at once. The Room had an amazing vibe going. Whenever I started feeling too small, I would walk in and the world around me just shrunk a little bit, and I felt a bit bigger. And then I walked into The Escape, and that was a whole other story. My friends and I were running around like little kids, turning every corner to see if there was something waiting on the other side. This will definitely become our regular Saturday night spot. It was a space devoid of hierarchy and exclusivity, redefining Beirut’s nightlife. It was an unforgettable cultural, uniting, and sonic experience. Oh, and most importantly, there was never a line at that bar.”

Karim, 23 years old.

Zodiac illustrations by Spiros Halaris

ACROSS

LITERATURE IMAGES

Bold, John, Peter Larkham, and Robert Pickard, eds. Authentic Reconstruction: Authenticity, Architecture and the Built Heritage. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2024. http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781474284073

Haugbolle, Sune. “Spaces of War, Spaces of Memory: Popular Expressions of Politics in Postwar Beirut.” In Contested Mediterranean Spaces: Ethnographic Essays. NED-New edition, 1., 77–91. Berghahn Books, 2011. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j. ctt9qd7zm.11

Larkin, Craig. “Reconstructing and Deconstructing Beirut: Space, Memory and Lebanese Youth.” Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper No. 8, (2009). https://citeseerx.ist.psu. edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi

Mager, T. Architecture RePerformed: The Politics of Reconstruction (1st ed.). Routledge, 2015. https://doi-org. libproxy.newschool.edu/10.4324/9781315567761

Mango, Tamam. “Solidere: the battle for Beirut’s Central District.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Department of Urban Studies and Planning, 2004. http://hdl.handle. net/1721.1/30107

Monroe, Kristin V. The Insecure City: Space, Power, and Mobility in Beirut. Rutgers University Press, 2016. http://www. jstor.org/stable/j.ctt1b67ws4

Musbahi, Moad. “Asl.” AA Files, no. 76 (2019): 16–23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27124565

Nora, Pierre. “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire.” Representations, no. 26 (1989): 7–24. https://doi. org/10.2307/2928520

Reder, Emeraude. « Désinvestir la mémoire : le cas d’étude du musée Beit Beirut », Confluences Méditerranée, 2020/1 (N° 112), p. 193-206. DOI: 10.3917/come.112.0193. URL: https://www. cairn.info/revue-confluences-mediterranee-2020-1-page-193.htm

Rogers, Sarah. “Out of History: Postwar Art in Beirut.” Art Journal 66, no. 2 (2007): 8–20. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/20068529

Salaame, Dounia. “On Memory and Commemoration in Beirut: The Holiday Inn in Bloom.”

Saliba, Robert. “Historicizing Early Modernity — Decolonizing Heritage: Conservation Design Strategies in Postwar Beirut.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements Review 25, no. 1 (2013): 7–24. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23612198

Salaam, Assem. “The Reconstruction Of Beirut: A Lost Opportunity.” AA Files, no. 27 (1994): 11–13. http://www.jstor. org/stable/29543890

Sawalha, Aseel. Reconstructing Beirut: Memory and Space in a Postwar Arab City. Austin: University of Texas Press, May 2010. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7560/721876

Seungkoo, Jo. “Aldo Rossi: Architecture and Memories.” Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering, May 2003.

Traboulsi, Fawwaz. “Chronology.” In A History of Modern Lebanon, 253–60. Pluto Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j. ctt183p4f5.21

Woods, Lebbeus. War and Architecture = Rat i Arhitektura. Princeton Architectural Press, 1993. https://www.are.na/block/2844797

https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/92693/caption-this https://issuu.com/sedki/docs/beiruts_egg https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/beirut-egg-lebanonprotests

https://blfheadquarters.com/2018/04/23/modern-architecture-inlebanon-city-center-movie-theater-10-12-april-23-2018/ https://www.designboom.com/architecture/anthony-saroufim-theegg-camera-obscura-beirut-02-16-2016/

https://www.spiroshalaris.com/projects/elle-zodiac

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AaYVIrFafBM

https://www.flickr.com/photos/tongeron91/49669173796/in/ photostream/

Most of the other imagery is produced by the author. The images are mostly taken from some interesting articles, projects, and posts about the Egg.

This newspaper edition serves as a tribute to The Egg, highlighting its storied past and promising future. Yet, The Egg is just one of hundreds of architectural gems scattered across Lebanon, each with its own unique history and significance. Lebanon is a country rich in cultural and architectural heritage, offering an abundance of sites that tell the story of its resilience, diversity, and beauty.

We encourage readers, whether familiar or unfamiliar with Lebanon, to delve deeper into the nation’s architectural wonders. By exploring these treasures, one can gain a greater appreciation for Lebanon’s past and the vibrant potential of its future. Let this edition be a gateway to discovering the beauty and depth of Lebanon’s architectural landscape, inspiring a deeper connection and a desire to learn more about this remarkable country.

Reflecting on my undergraduate journey at Parsons, I’ve encountered various challenges and breakthroughs, particularly during the thesis process. Initially resistant to the structured process, I gradually embraced the value of community and sharing ideas, despite my inclination towards perfectionism and keeping my process personal. Throughout the semester, I faced setbacks and moments of self-doubt, but ultimately found inspiration in revisioning my project, particularly in regards to the Egg.

At the outset, I aimed for meticulous planning and adherence to timelines, only to realize that creative processes are often unpredictable. As I delved into my project on the Egg, I initially hesitated to intervene, viewing it as a precious relic untouched by time. However, with guidance and critique, I shifted my perspective, recognizing the importance of reimagining the space as a dynamic environment for collective exploration and remembrance.

One of my key successes was redefining the project’s program to respect the Egg’s history while inviting engagement and discovery. Moving forward, I am eager to explore aspects such as lighting and structural detailing to further enhance the experience of the space. Despite the semester’s challenges, I am motivated to continue this journey, embracing the opportunity for further growth and innovation in the future.

KHABSA

«DELICIOUSLY ABSURD COMEDY FEAST!»

-rotten tomatoes

-an-nahar

«WHO KNEW CHAOS COULD BE THIS FUNNY?»

-l’ orient le jour

STARRING

ROLA BEKSMATI

ABBOUDY MALLAH

JUNAID ZEINELDIN

PRESENTS

B2 FLOORPLAN