21 minute read

Dr. Todd Capistrant: What is OMM?

OMM: What is it? And, more importantly, what can it do for me?

By Dr. Todd Capistrant S o you want to see a doctor? You found one but their degree says D.O.? What’s a D.O.? Doctors of osteopathy, or D.O.s, have been around for a long time. Osteopathy was first developed by Dr. A.T. Still in 1892. Dr. Still was a pioneering physician who believed the structure of the body was directly connected to the function of the body and its organ systems. Alteration or disruption of the body’s structure could lead to illness. Therefore, correcting the body’s structural issues could improve the overall function of the body and a person’s health.

Advertisement

Today there are more than 137,000 practicing doctors of osteopathy in the United States. By the year 2030, 20% of all physicians in the United States will hold the D.O. degree. In fact, many people in the United States have seen a D.O. and did not realize they were seeing a fully licensed and trained physician with a “different” degree. The training of M.D.s and D.O.s is very similar and quite rigorous. One main difference about doctors of osteopathy is that during their medical school training they learn the basic principles of osteopathic manipulative medicine.

What is osteopathic manipulative medicine, or OMM? This designation represents the part of osteopathic medicine that a D.O. would use to diagnosis and address the altered structure of a patient’s body. Osteopathic manipulative medicine is a specialty in and of itself. Just as all physicians learn about the heart, we have cardiologists who specialize even further in disease of the heart. Similarly, all D.O.s learn about OMM, but there are D.O.s who focus their practice on treating the musculoskeletal system. Some of these doctors have even done additional residency training in what is called osteopathic neuromusculoskeletal medicine, or ONMM.

The OMM provider is a specialist in the structure and function of the body as seen through the musculoskeletal system. All aspects of the body from the soft tissue, bones, joints, and fluids are vital to a normal functioning person, and the OMM specialist has many techniques to employ to help correct issues in these tissues of the body. Some

of the techniques used are very subtle, and some are much more direct and at times painful.

What issues can be addressed by OMM? Any musculoskeletal complaint, not just pain, can be evaluated by a physician working with OMM. OMM is a model of thinking that provides the D.O. physician with a vast tool kit that can be applied to any age patient, from newborn to the elderly. Some of the common issues seen in an OMM department are back and neck pain, muscle strains or sprains, headaches, or pain in the limbs such as carpal tunnel or plantar fasciitis. Any muscle sprain or strain can be evaluated with OMM. In infants, colic or difficulties feeding or latching can be addressed using OMM techniques and theories. In addition to addressing pain complaints, OMM can be used to address decreased range of motion caused by illness or injury. Many athletes seek the help of OMM for maximizing performance and improving body function.

If you are interested in learning more about what osteopathic medicine represents or what OMM can address, you can visit www.osteopathic.org.

Dr. Capistrant specializes in osteopathic manipulative medicine and is certified by the American Board of Family Medicine. He is a member of the growing OMM department at the Tanana Valley Clinic in Fairbanks.

Music Man

Mike Stevens plays the harmonica on the banks of the Kuskokwim River in Bethel in spring 2019. Courtesy of Healing Through Music and Dance Program.

Every student gets a harmonica when Mike Stevens comes to town. Students in Nenana try theirs out. Eric Filardi photo

Harmonica virtuoso Mike Stevens helps young people express their emotions in a creative and healing way. He does it by handing them each a harmonica. It isn’t long before they are telling their own compelling stories through music.

“It’s pretty simple actually,” Stevens said. “It’s human. It’s not staring at a screen or looking into your phone or watching too much TV. It’s connecting with kids and community.

“And it makes me feel good.” The internationally known musician, who is originally from southern Ontario, has performed hundreds of times on stage at the famous Grand Ole Opry. But 20 years ago, that star trajectory took a detour after he visited a remote village in northern Labrador and encountered young people sniffing gasoline. Since then he has dedicated his life to reaching out to young people, especially in remote communities. He founded the nonprofit ArtsCan Circle and now links creative artists with atrisk youth to build skills and self-esteem through art and music. His focus has been on rural communities in Alaska and Canada.

Stevens has been the subject of two feature film documentaries and is the recipient of Canada’s Medal of Honor. His “Healing Music and Dance” program is now sponsored by the Bethel Community Services Foundation. Since 2013, Stevens has regularly toured Alaska’s Western, Interior and North Slope regions. At each community he focuses on his most important audience — teens and their own music. He encourages artistic expression of feelings and helps them give voice to the otherwise inexpressible. Often it is the beginning of recovering from trauma. The musical storytelling skills he shares promote self-esteem and creative self-expression. Kids learn to listen.

And it all starts with putting a harmonica in the hands of a child. The power of music Stevens confesses right away that he can’t read a note of music. He has a condition called synesthesia, which allows him to see and hear colors as specific notes.

“I hear music in color,” he said. “I just make it up based on how I feel.” Helping teens find healing, affirmation through art, music By Kris Capps Alaska Pulse

Left, harmonica virtuoso Mike Stevens shows students how to use a Looper. Stevens travels with this case filled with harmonicas. Kris Capps photos

Then he starts with a demonstration. Kids shout out an emotion and he plays it on the harmonica: happy, sad, scared, angry, nervous. The audience is delighted at his musical interpretation. Before long they are experimenting with that harmonica themselves.

Follow-up visits are important, and Stevens always looks forward to returning to rural communities.

“That is the key, really,” he said. He thought back to how the government used to handle situations in remote communities of his home country of Canada.

“Whenever a big ‘problem’ came up, the media jumped on it, and the government would have a bunch of people who had never even been in the community dream up some plan to fix it, then spend a whole bunch of money on it. Then the money ran out and nothing changed and nothing got fixed.

His repeat visits are not about instant fixes. They are about building relationships over time.

“It does work,” he said. “Against all odds, it really does work.”

An instrument of success He has been a frequent visitor at Nenana City School, for example. Nenana is a small community about 50 miles south of Fairbanks on the Parks Highway. Many teens attend the school from all over the state and live at the Nenana Student Living Center.

“Mike Stevens showed our students how harmonica music can be used to express our inner feelings, and the power of this expression in helping to cope with situations requiring resiliency,” said Eric Filardi, a teacher at Nenana City School. “His captivating and energetic personality is immensely supportive of our kids and invites them to take safe risks in their comfort of performance.” Stevens is an expert at convincing children and teens that anyone can play the harmonica. He shows them how to do it.

What Stevens shares, according to Filardi, is how to be inventive, resourceful and imaginative with that harmonica. Those are skills needed to succeed today and in the future, he said.

Stevens also donated a Looper to Filardi’s classroom. The Looper records sounds and allows students to compose their own music, incorporating traditional and beat-boxing techniques. Those students create their own sounds — a wolf howling, whistling of the wind, a beautiful bird call and the crackling of a fire, created by crumpling a piece of paper close to the microphone. When using the Looper, students are learning technology and also acting as a team to create a story and a

Mike Stevens and Nenana students show off their harmonicas. Kris Capps photo

— James Menaker, director of the Fairbanks Summer Arts Festival

piece of music.

It’s not unusual for students to spontaneously start dancing in traditional indigenous style or a blend of break dancing with traditions, while another student sings and others drum physically or electronically.

One by one, students are drawn into creating their own music, and one by one their faces fill with smiles at the result. The harmonica master praises them.

“That’s how you tell a story,” he tells them. “You don’t need words. You’re telling a story with sound right now.” ‘I’m very lucky’ The harmonica, along with Stevens’ enthusiasm, is a powerful tool of change. “He has the ability to connect with young people who have been marginalized in our society and draw out of them the reality of their thoughts and dreams and emotions,” said James Menaker, director of the Fairbanks Summer Arts Festival. Stevens was a frequent guest artist with the festival.

Sometimes it is that small harmonica that breaks through a long built-up wall of resistance.

At one village in 2018, teachers suggested he would be wasting his time trying to work with certain teens. Other adult professionals had been unable to “reach” these children.

“He showed them how to create their own language using music and express in song what words did not have the power to convey,” Menaker said. “He played and they played and they played together and they began dancing, pulling out traditional dances that they had not performed in years and years. The teachers’ eyes popped open and their jaws hit the floor as they shared that they had never seen anything like this before.

“He is a shining example of what happens when you are able to awaken the inner artist of young men and women: community transformation,” Menaker said.

Sometimes Stevens thinks about what life would be like if he hadn’t taken that trip to Labrador and met those kids huffing gas.

“I’d probably be living in Nashville,” he said “I’d probably be a lot more famous and have a lot more money.

“But ya know what? There’s a lot of ways of measuring wealth, and the only time I would ever reflect that way is if I was feeling sorry for myself for a second. Pretty soon, I slap myself.

“I get to play an instrument I love, for a living,” he said. “I’m very lucky.”

Reach columnist/community editor Kris Capps at 459-7546.

In search of some shut-eye

Lab aims to shed light on nighttime slumber troubles By Kyrie Long Alaska Pulse R ooms in the Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Sleep Disorders Center don’t look like a traditional hospital setup. In one, a bed dominates the floor, with an armchair and sofa off to the right-hand side and an attached bathroom on the left. The tones of the room are warm brown, and a television is mounted on the wall across from the bed. “This is actually the room we use for pediatric patients or someone who has a caregiver that would need to stay with them,” said Andre Keller, director of respiratory care and the sleep lab. “So the caregiver can stay on the couch and stay overnight with the patient.”

The lab is a four-bedroom facility set up four years ago to help patients in their quest for a regular restful night of sleep.

Some patients prefer to sleep in an armchair, as well. Sometimes a patient has a heart or respiratory condition, or trouble sleeping in a bed.

While Keller noted this arrangement isn’t preferable, it is an option for those who are more comfortable that way.

Basically, the staff try to accommodate the patient’s situation, according to Dr. Clay Triplehorn, medical director of the facility. If they need to do something to gather the information, even if they have to make different decisions, that’s what they try to do, he said.

“We try to work around the patient to

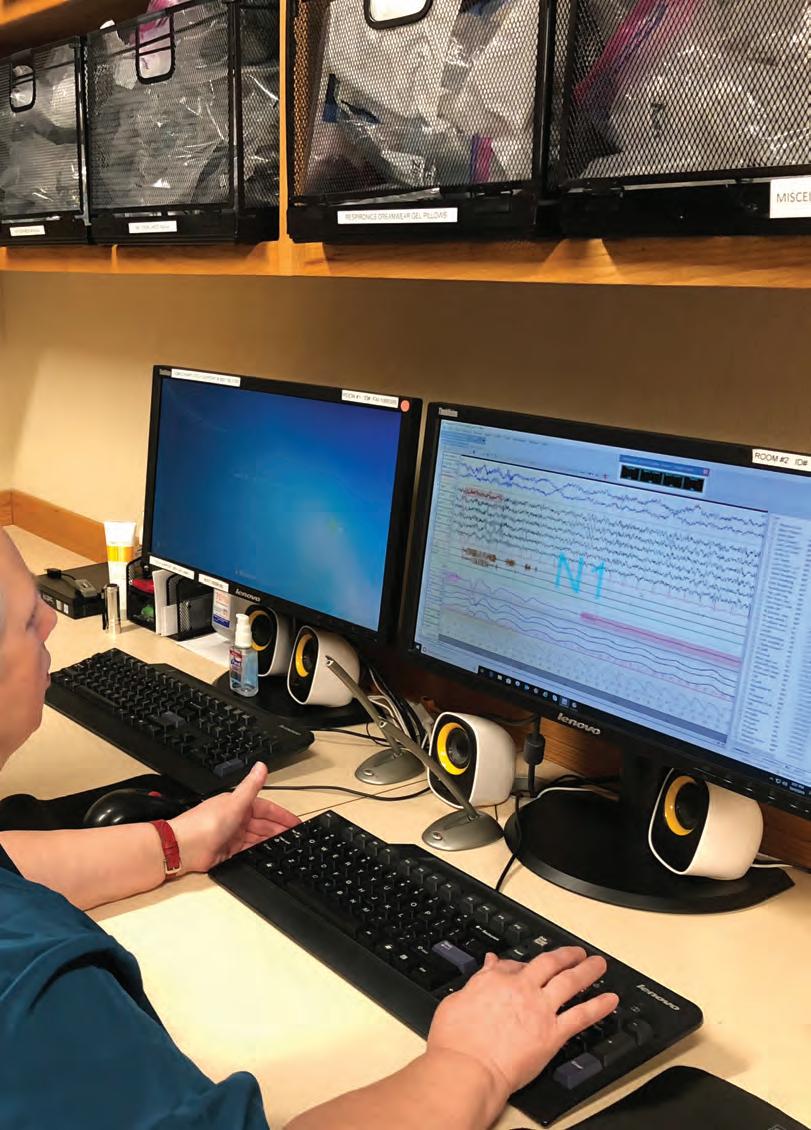

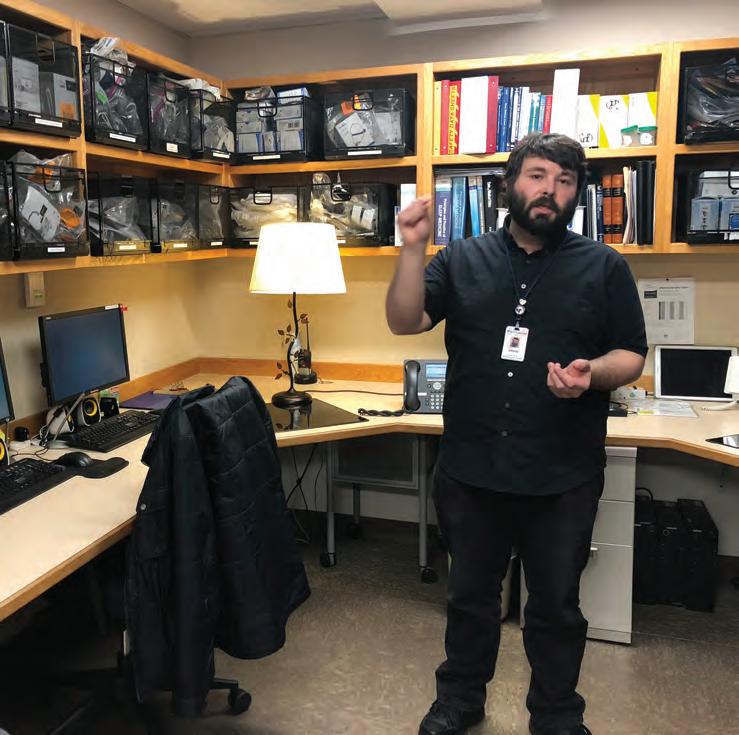

Left, Andre Keller, director of respiratory care and the sleep lab, and Elizabeth Davis, a day sleep technician, demonstrate how their system works, bringing an older sleep study up on the monitor to explain how they mark different stages of sleep. Above, this head box is where all the wires connected to patients are hooked up. Not every connector is used, but this device helps monitor the body, including heart rate, while patients of the sleep lab rest overnight. Kyrie Long photos

make it happen, because if we’re trying to make patients follow our rules, people aren’t automatons. People are individuals, they do what they want to do,” said Triplehorn, “and so the more we try to meet peoples’ needs the better off we are.”

Sleep tech In a separate room with four computer monitors, Keller explains how the sleep lab works.

The lab has four beds with four computers. In each bed is an acquisition PC, which gathers data as the patient sleeps. Everything is hooked up to a head box, which is dotted with tiny wire connectors. The patient is hooked up to various wires that monitor brainwaves, heart rate, respiratory effort, airflow and oxygen levels. The four computers in the rooms are connected to four work stations, where technicians see the data in real time and score it.

“Scoring” means they mark sections of the data feed, according to Keller, determining what stage of sleep the patient is in and any “obstructive events,” such as sleep apnea and oxygen desaturation. The room with the work stations has various CPAP face masks in baskets above the desk space. CPAP is short for Continuous Positive Airway Pressure and the masks push air to the patient to keep airways open. The lab carries around 45 types of masks, and Keller noted that the technology is improving from year to year.

Generally people arrive for a polysomnography, more commonly called a sleep study, after they first visit Tanana Valley Clinic. There, Triplehorn said, they clarify what the patient’s priorities are. From there, sometimes, it’s decided that the patient will need to visit the sleep lab.

The Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Sleep Disorders Center at 1701 Gillam Way is separate from the main hub of the hospital where patients can go to have sleep studies conducted. One of the four rooms is shown at right. Bottom, Andre Keller explains how the monitoring stations allow lab staff to keep an eye on patients during their studies. Kyrie Long photos

People are usually scheduled to arrive around 8 p.m., according to Keller. The process of getting the wires attached for monitoring takes 30 to 45 minutes, while paperwork is about 10 to 15 minutes. From there patients tend to head to bed from 9-10 p.m. Some patients do stay up a bit later, depending on their usual schedule.

“The key thing is that we do need enough data. So we do need patients to fall asleep by about 11, midnight, something like that so we can have enough data to give Dr. Triplehorn a good study,” Keller said.

Why study sleep? “The challenge is, with sleep, it’s not just the technical stuff, right? It’s not just coming in, getting a sleep study,” Triplehorn said. “It’s me talking to you, me doing a physical exam, we’re hearing your story, and then we use the technical stuff to actually help piece that apart, to try to figure out what’s going on.”

People come to the clinic for a variety of reasons: They see sleep apnea patients frequently; they see veterans who have

trouble sleeping; sometimes people walk or talk in their sleep; and sometimes it’s as simple as recurring headaches at night. In his experience with sleep disorders, Triplehorn said, it is never one thing and there is never one fix. The best approach, he said, is a really broad approach, looking at mental health issues, heart issues, neurological issues and coming up with a plan to address everything.

“In my mind ... in our population up here, that’s the best approach and that works pretty well,” he said.

The Fairbanks Memorial Hospital Sleep Disorder Center may be only 4 years old, however, the hospital has been working with patients on sleep-specific issues since the 1990s.

If you want to think about sleep, according to Triplehorn, it’s somewhat like looking at why you need to breathe or eat.

“If you don’t sleep, your physiology rapidly declines, but not in seconds or minutes like if you stop breathing, or days to weeks like if you stop eating or drinking,” he said.

Sleep deprivation can lead to issues like having trouble regulating temperature, blood pressure, emotions and even declining cognition. Long-term sleep deprivation can also increase risk for cognitive disorders like Alzheimer’s and even cancer. That’s why Triplehorn says it’s important to study sleep.

“The challenge has been … it’s only been in the last maybe 15 to 20 years where we’ve actually had the technology, where we can actually look at sleep and actually see how it impacts our lives, how it impacts our health and physiology,” he said. “That’s only been in the last two decades.”

For human beings, Triplehorn said, a lot of times the importance of things a lot of times has to do with how you can look at it.

So the fact that we weren’t able to look at sleep in any really meaningful way scientifically, people tend to minimize how important sleep is,” he said.

Even growing up, Triplehorn said, it was considered no big deal to sleep five or six hours a night.

“But we’re actually finding that that’s not true, and that actually sleep is an extremely part of our physiology — both short term and long term.”

Contact staff writer Kyrie Long at 459-7510.

North WiNd Behavioral

Caroline Atkinson MA, LPC Licensed Professional Counselor Cathy Johnson RN, MSB, ANP Advanced Nurse Practitioner Elizabeth Kraska MA, LPC Licensed Professional Counselor

1867 airport Way Suite 215 FairBaNkS, alaSka (907) 456-1434 Fax (907) 456-1481

Services include: individual, couples and family therapies and medication management. Hours: Monday–Thursday 9:30 a.m. – 5 p.m. • Most Insurances Accepted • www.northwindbehavioral.com North Wind Behavioral Health offers outpatient treatment for anxiety, depression, PTSD, mood disorders, ADHD and other behavioral health challenges.

The explorers are making a New Year resolution is to get healthier. Can you help Katlin find her way to the soccer field?

New Year’s Healthy Resolution Maze

Baxter Mercer, assistant chief at the Tri-Valley Volunteer Fire Department, was honored with a community service award at the No One Left Behind ceremony in 2019. He celebrates with Denali Borough Mayor Clay Walker and his wife, Renee Mercer. Kris Capps photo

Giving blood turns into lifesaving measure for donor

By Kris Capps Alaska Pulse E very seven or eight weeks, Baxter Mercer, 67, makes an appointment to drive more than 100 miles to Fairbanks to donate blood at the Alaska Blood Bank. One day, that visit actually saved his life.

In 2014, he went in for his usual visit and got turned away because his heartbeat was below 50 beats per minute. “That was weird,” his wife, Renee Mercer, said as she recalled that day. “Usually, it’s over 60 beats per minute.” It was time to visit a doctor. “They could not get an accurate reading, so they hooked a monitor up to him for two days,” she said.

A few days later, just after he responded to an emergency ambulance call with Tri-Valley Volunteer Fire Department in Healy, the doctor called and told Renee her husband needed to come to Fairbanks immediately. The doctor also ordered him not to drive.

Too late. He was already on the road, driving an ambulance north to Fairbanks, delivering two accident victims to Fairbanks Memorial Hospital. With that done, he prepared to drive the ambulance back to Healy. He called his wife to let her know he would soon be heading home.

That’s when she told him to go directly to the hospital’s heart center instead. To his own surprise, he ended up having a pacemaker installed that same morning.

Suddenly, there was an explanation for symptoms that he earlier attributed to routine fatigue, stress or aging. If not for that regular stop to donate blood, he might not have discovered his urgent need for a pacemaker. The outcome could have been deadly.

“I keep harping about modern technology, and now I probably owe my life

Blood Bank of Alaska locations Anchorage 1215 Airport Heights 907-222-5600 8920 Old Seward Highway, Suite C 907-222-5630

Juneau 8800 Glacier Highway, No. 236 907-222-5680

Wasilla 1301 Seward Meridian Parkway, Suite H 907-357-5555

Fairbanks 3010 Airport Way 907-456-5645 More info: www.bloodbankofalaska.org/

Baxter Mercer has donated more than 5 gallons of blood at the Alaska Blood Bank. His wife, Renee, is proud of him. Photo courtesy Renee Mercer

to modern technology,” he said.

A ‘really valuable person’ Courtney Reynolds, supervisor at the Alaska Blood Bank, was a technician that day when Mercer was not allowed to routinely donate blood. When he returned later and shared the news about his pacemaker, the staff felt honored, she said. They knew that their evaluation that day led to his continued good health.

“If we’re able to not only save a life through donating but also by making sure they are healthy, we’re doing a good job,” she said.

Baxter Mercer is one of the blood bank’s regular donors and has contributed more than 5 gallons of blood so far. “You can donate six times per year,” Reynolds said. “Every donation is one pint or 500 milliliters. It takes eight donations to make one gallon. So it takes well over five years to donate 5 gallons.”

Everyone has their own reason for donating blood, according to Reynolds. “Some had a family member who needed blood and they came in,” she said. “For some, their parents did it, so in high school they started and never stopped.”

Mercer said he donated blood a few times back in Laramie, Wyoming, but decided to donate regularly after a local VISTA volunteer arranged a blood drive in Healy many years ago.

“I thought ‘Why not?’ “ he said. “It sounds like a good idea. So I went to Fairbanks and found out where I could do it.”

The Alaska Blood Bank is located at 3010 Airport Way.

“The second time I went, they told me I was a really valuable person,” he recalled. They told him his blood type is O-negative.

That made him a universal donor. These donors have the ability to help anyone in need of a blood transfusion. Red blood cells from O-negative donors can be transfused to anyone, regardless of that person’s blood type.

“Even newborn babies,” Mercer said. “I happened to fall in that category too, so I thought that was a good idea.”

During subsequent family reunions, Mercer discovered that four or five of his cousins were also O-negative. Some of them are also regular blood donors. “My cousin Roy in Tulsa, Oklahoma was up to 23 or 28 gallons,” Mercer said. “He started as soon as he got out of high school.”

Mercer plans to stick to his donation schedule.

“As long as they’ll keep taking it, I’ll keep donating,” he said.

So you want to donate blood? The Alaska Blood Bank regularly hosts blood drives for organizations or businesses.

“Every business can run a blood drive that is six weeks long, or a month long, and they can come in and donate at their convenience,” Reynolds said.

On rare occasions, the blood bank will put out a call for donors when supplies run critically low.

If you decide to donate blood, here’s what you should do to prepare: Eat well leading up to the day of donation and drink lots of fluids.

“We want you to be extremely hydrated,” Reynolds said. “We’ll be taking some good minerals out of your system and we want you to have plenty for yourself as well.”

Reach columnist/community editor Kris Capps at 459-7546.