PROLOGUE

THE COMET’S TAIL SPREAD ACROSS the dawn, a red slash that bled above the crags of Dragonstone like a wound in the pink and purple sky.

The maester stood on the windswept balcony outside his chambers. It was here the ravens came, after long flight. Their droppings speckled the gargoyles that rose twelve feet tall on either side of him, a hellhound and a wyvern, two of the thousand that brooded over the walls of the ancient fortress. When first he came to Dragonstone, the army of stone grotesques had made him uneasy, but as the years passed he had grown used to them. Now he thought of them as old friends. The three of them watched the sky together with foreboding.

The maester did not believe in omens. And yet…old as he was, Cressen had never seen a comet half so bright, nor yet that color, that terrible color, the color of blood and flame and sunsets. He wondered if his gargoyles had ever seen its like. They had been here so much longer than he had, and would still be here long after he was gone. If stone tongues could speak…

Such folly. He leaned against the battlement, the sea crashing beneath him, the black stone rough beneath his fingers. Talking gargoyles and prophecies in the sky. I am an old done man, grown giddy as a child again. Had a lifetime’s hard-won wisdom fled him along with his health and strength? He was a maester, trained and chained in the great Citadel of Oldtown. What had he come to, when superstition filled his head as if he were an ignorant fieldhand?

And yet…and yet…the comet burned even by day now, while pale grey steam rose from the hot vents of Dragonmont behind the castle, and yestermorn a white raven had brought word from the Citadel itself, word long-expected but no less fearful for all that, word of

summer’s end. Omens, all. Too many to deny. What does it all mean? he wanted to cry.

“Maester Cressen, we have visitors.” Pylos spoke softly, as if loath to disturb Cressen’s solemn meditations. Had he known what drivel filled his head, he would have shouted. “The princess would see the white raven.” Ever correct, Pylos called her princess now, as her lord father was a king. King of a smoking rock in the great salt sea, yet a king nonetheless. “Her fool is with her.”

The old man turned away from the dawn, keeping a hand on his wyvern to steady himself. “Help me to my chair and show them in.”

Taking his arm, Pylos led him inside. In his youth, Cressen had walked briskly, but he was not far from his eightieth name day now, and his legs were frail and unsteady. Two years past, he had fallen and shattered a hip, and it had never mended properly. Last year when he took ill, the Citadel had sent Pylos out from Oldtown, mere days before Lord Stannis had closed the isle…to help him in his labors, it was said, but Cressen knew the truth. Pylos had come to replace him when he died. He did not mind. Someone must take his place, and sooner than he would like…

He let the younger man settle him behind his books and papers. “Go bring her. It is ill to keep a lady waiting.” He waved a hand, a feeble gesture of haste from a man no longer capable of hastening. His flesh was wrinkled and spotted, the skin so papery thin that he could see the web of veins and the shape of bones beneath. And how they trembled, these hands of his that had once been so sure and deft…

When Pylos returned the girl came with him, shy as ever. Behind her, shuffling and hopping in that queer sideways walk of his, came her fool. On his head was a mock helm fashioned from an old tin bucket, with a rack of deer antlers strapped to the crown and hung with cowbells. With his every lurching step, the bells rang, each with a different voice, clang-a-dang bong-dong ring-a-ling clong clong clong.

“Who comes to see us so early, Pylos?” Cressen said.

“It’s me and Patches, Maester.” Guileless blue eyes blinked at him. Hers was not a pretty face, alas. The child had her lord father’s square jut of jaw and her mother’s unfortunate ears, along with a disfigurement all her own, the legacy of the bout of greyscale that had almost claimed her in the crib. Across half one cheek and well down her neck, her flesh was stiff and dead, the skin cracked and flaking, mottled black and grey and stony to the touch. “Pylos said we might see the white raven.”

“Indeed you may,” Cressen answered. As if he would ever deny her. She had been denied too often in her time. Her name was Shireen. She would be ten on her next name day, and she was the saddest child that Maester Cressen had ever known. Her sadness is my shame, the old man thought, another mark of my failure. “Maester Pylos, do me a kindness and bring the bird down from the rookery for the Lady Shireen.”

“It would be my pleasure.” Pylos was a polite youth, no more than five-and-twenty, yet solemn as a man of sixty. If only he had more humor, more life in him; that was what was needed here. Grim places needed lightening, not solemnity, and Dragonstone was grim beyond a doubt, a lonely citadel in the wet waste surrounded by storm and salt, with the smoking shadow of the mountain at its back. A maester must go where he is sent, so Cressen had come here with his lord some twelve years past, and he had served, and served well. Yet he had never loved Dragonstone, nor ever felt truly at home here. Of late, when he woke from restless dreams in which the red woman figured disturbingly, he often did not know where he was.

The fool turned his patched and piebald head to watch Pylos climb the steep iron steps to the rookery. His bells rang with the motion. “Under the sea, the birds have scales for feathers,” he said, clang-a-langing. “I know, I know, oh, oh, oh.”

Even for a fool, Patchface was a sorry thing. Perhaps once he could evoke gales of laughter with a quip, but the sea had taken that power from him, along with half his wits and all his memory. He was soft and obese, subject to twitches and trembles, incoherent as often

as not. The girl was the only one who laughed at him now, the only one who cared if he lived or died.

An ugly little girl and a sad fool, and maester makes three…now there is a tale to make men weep. “Sit with me, child.” Cressen beckoned her closer. “This is early to come calling, scarce past dawn. You should be snug in your bed.”

“I had bad dreams,” Shireen told him. “About the dragons. They were coming to eat me.”

The child had been plagued by nightmares as far back as Maester Cressen could recall. “We have talked of this before,” he said gently. “The dragons cannot come to life. They are carved of stone, child. In olden days, our island was the westernmost outpost of the great Freehold of Valyria. It was the Valyrians who raised this citadel, and they had ways of shaping stone since lost to us. A castle must have towers wherever two walls meet at an angle, for defense. The Valyrians fashioned these towers in the shape of dragons to make their fortress seem more fearsome, just as they crowned their walls with a thousand gargoyles instead of simple crenellations.” He took her small pink hand in his own frail spotted one and gave it a gentle squeeze. “So you see, there is nothing to fear.”

Shireen was unconvinced. “What about the thing in the sky? Dalla and Matrice were talking by the well, and Dalla said she heard the red woman tell Mother that it was dragonsbreath. If the dragons are breathing, doesn’t that mean they are coming to life?”

The red woman, Maester Cressen thought sourly. Ill enough that she’s filled the head of the mother with her madness, must she poison the daughter’s dreams as well? He would have a stern word with Dalla, warn her not to spread such tales. “The thing in the sky is a comet, sweet child. A star with a tail, lost in the heavens. It will be gone soon enough, never to be seen again in our lifetimes. Watch and see.”

Shireen gave a brave little nod. “Mother said the white raven means it’s not summer anymore.”

“That is so, my lady. The white ravens fly only from the Citadel.” Cressen’s fingers went to the chain about his neck, each link forged from a different metal, each symbolizing his mastery of another branch of learning; the maester’s collar, mark of his order. In the pride of his youth, he had worn it easily, but now it seemed heavy to him, the metal cold against his skin. “They are larger than other ravens, and more clever, bred to carry only the most important messages. This one came to tell us that the Conclave has met, considered the reports and measurements made by maesters all over the realm, and declared this great summer done at last. Ten years, two turns, and sixteen days it lasted, the longest summer in living memory.”

“Will it get cold now?” Shireen was a summer child, and had never known true cold.

“In time,” Cressen replied. “If the gods are good, they will grant us a warm autumn and bountiful harvests, so we might prepare for the winter to come.” The smallfolk said that a long summer meant an even longer winter, but the maester saw no reason to frighten the child with such tales.

Patchface rang his bells. “It is always summer under the sea,” he intoned. “The merwives wear nennymoans in their hair and weave gowns of silver seaweed. I know, I know, oh, oh, oh.”

Shireen giggled. “I should like a gown of silver seaweed.”

“Under the sea, it snows up,” said the fool, “and the rain is dry as bone. I know, I know, oh, oh, oh.”

“Will it truly snow?” the child asked.

“It will,” Cressen said. But not for years yet, I pray, and then not for long. “Ah, here is Pylos with the bird.”

Shireen gave a cry of delight. Even Cressen had to admit the bird made an impressive sight, white as snow and larger than any hawk, with the bright black eyes that meant it was no mere albino, but a truebred white raven of the Citadel. “Here,” he called. The raven spread its wings, leapt into the air, and flapped noisily across the room to land on the table beside him.

“I’ll see to your breakfast now,” Pylos announced. Cressen nodded. “This is the Lady Shireen,” he told the raven. The bird bobbed its pale head up and down, as if it were bowing. “Lady,” it croaked. “Lady.”

The child’s mouth gaped open. “It talks!”

“A few words. As I said, they are clever, these birds.”

“Clever bird, clever man, clever clever fool,” said Patchface, jangling. “Oh, clever clever clever fool.” He began to sing. “The shadows come to dance, my lord, dance my lord, dance my lord,” he sang, hopping from one foot to the other and back again. “The shadows come to stay, my lord, stay my lord, stay my lord.” He jerked his head with each word, the bells in his antlers sending up a clangor.

The white raven screamed and went flapping away to perch on the iron railing of the rookery stairs. Shireen seemed to grow smaller. “He sings that all the time. I told him to stop but he won’t. It makes me scared. Make him stop.”

And how do I do that? the old man wondered. Once I might have silenced him forever, but now…

Patchface had come to them as a boy. Lord Steffon of cherished memory had found him in Volantis, across the narrow sea. The king —the old king, Aerys II Targaryen, who had not been quite so mad in those days—had sent his lordship to seek a bride for Prince Rhaegar, who had no sisters to wed. “We have found the most splendid fool,” he wrote Cressen, a fortnight before he was to return home from his fruitless mission. “Only a boy, yet nimble as a monkey and witty as a dozen courtiers. He juggles and riddles and does magic, and he can sing prettily in four tongues. We have bought his freedom and hope to bring him home with us. Robert will be delighted with him, and perhaps in time he will even teach Stannis how to laugh.”

It saddened Cressen to remember that letter. No one had ever taught Stannis how to laugh, least of all the boy Patchface. The storm came up suddenly, howling, and Shipbreaker Bay proved the truth of its name. The lord’s two-masted galley Windproud broke up within

sight of his castle. From its parapets his two eldest sons had watched as their father’s ship was smashed against the rocks and swallowed by the waters. A hundred oarsmen and sailors went down with Lord Steffon Baratheon and his lady wife, and for days thereafter every tide left a fresh crop of swollen corpses on the strand below Storm’s End.

The boy washed up on the third day. Maester Cressen had come down with the rest, to help put names to the dead. When they found the fool he was naked, his skin white and wrinkled and powdered with wet sand. Cressen had thought him another corpse, but when Jommy grabbed his ankles to drag him off to the burial wagon, the boy coughed water and sat up. To his dying day, Jommy had sworn that Patchface’s flesh was clammy cold.

No one ever explained those two days the fool had been lost in the sea. The fisherfolk liked to say a mermaid had taught him to breathe water in return for his seed. Patchface himself had said nothing. The witty, clever lad that Lord Steffon had written of never reached Storm’s End; the boy they found was someone else, broken in body and mind, hardly capable of speech, much less of wit. Yet his fool’s face left no doubt of who he was. It was the fashion in the Free City of Volantis to tattoo the faces of slaves and servants; from neck to scalp the boy’s skin had been patterned in squares of red and green motley.

“The wretch is mad, and in pain, and no use to anyone, least of all himself,” declared old Ser Harbert, the castellan of Storm’s End in those years. “The kindest thing you could do for that one is fill his cup with the milk of the poppy. A painless sleep, and there’s an end to it. He’d bless you if he had the wit for it.” But Cressen had refused, and in the end he had won. Whether Patchface had gotten any joy of that victory he could not say, not even today, so many years later.

“The shadows come to dance, my lord, dance my lord, dance my lord,” the fool sang on, swinging his head and making his bells clang and clatter. Bong dong, ring-a-ling, bong dong.

“Lord,” the white raven shrieked. “Lord, lord, lord.”

“A fool sings what he will,” the maester told his anxious princess. “You must not take his words to heart. On the morrow he may remember another song, and this one will never be heard again.” He can sing prettily in four tongues, Lord Steffon had written… Pylos strode through the door. “Maester, pardons.”

“You have forgotten the porridge,” Cressen said, amused. That was most unlike Pylos.

“Maester, Ser Davos returned last night. They were talking of it in the kitchen. I thought you would want to know at once.”

“Davos…last night, you say? Where is he?”

“With the king. They have been together most of the night.”

There was a time when Lord Stannis would have woken him, no matter the hour, to have him there to give his counsel. “I should have been told,” Cressen complained. “I should have been woken.” He disentangled his fingers from Shireen’s. “Pardons, my lady, but I must speak with your lord father. Pylos, give me your arm. There are too many steps in this castle, and it seems to me they add a few every night, just to vex me.”

Shireen and Patchface followed them out, but the child soon grew restless with the old man’s creeping pace and dashed ahead, the fool lurching after her with his cowbells clanging madly.

Castles are not friendly places for the frail, Cressen was reminded as he descended the turnpike stairs of Sea Dragon Tower. Lord Stannis would be found in the Chamber of the Painted Table, atop the Stone Drum, Dragonstone’s central keep, so named for the way its ancient walls boomed and rumbled during storms. To reach him they must cross the gallery, pass through the middle and inner walls with their guardian gargoyles and black iron gates, and ascend more steps than Cressen cared to contemplate. Young men climbed steps two at a time; for old men with bad hips, every one was a torment. But Lord Stannis would not think to come to him, so the maester resigned himself to the ordeal. He had Pylos to help him, at the least, and for that he was grateful.

Shuffling along the gallery, they passed before a row of tall arched windows with commanding views of the outer bailey, the curtain wall, and the fishing village beyond. In the yard, archers were firing at practice butts to the call of “Notch, draw, loose.” Their arrows made a sound like a flock of birds taking wing. Guardsmen strode the wallwalks, peering between the gargoyles on the host camped without. The morning air was hazy with the smoke of cookfires, as three thousand men sat down to break their fasts beneath the banners of their lords. Past the sprawl of the camp, the anchorage was crowded with ships. No craft that had come within sight of Dragonstone this past half year had been allowed to leave again. Lord Stannis’s Fury, a triple-decked war galley of three hundred oars, looked almost small beside some of the big-bellied carracks and cogs that surrounded her.

The guardsmen outside the Stone Drum knew the maesters by sight, and passed them through. “Wait here,” Cressen told Pylos, within. “It’s best I see him alone.”

“It is a long climb, Maester.”

Cressen smiled. “You think I have forgotten? I have climbed these steps so often I know each one by name.”

Halfway up, he regretted his decision. He had stopped to catch his breath and ease the pain in his hip when he heard the scuff of boots on stone, and came face-to-face with Ser Davos Seaworth, descending.

Davos was a slight man, his low birth written plain upon a common face. A well-worn green cloak, stained by salt and spray and faded from the sun, draped his thin shoulders, over brown doublet and breeches that matched brown eyes and hair. About his neck a pouch of worn leather hung from a thong. His small beard was well peppered with grey, and he wore a leather glove on his maimed left hand. When he saw Cressen, he checked his descent.

“Ser Davos,” the maester said. “When did you return?”

“In the black of morning. My favorite time.” It was said that no one had ever handled a ship by night half so well as Davos

Shorthand. Before Lord Stannis had knighted him, he had been the most notorious and elusive smuggler in all the Seven Kingdoms.

“And?”

The man shook his head. “It is as you warned him. They will not rise, Maester. Not for him. They do not love him.”

No, Cressen thought. Nor will they ever. He is strong, able, just… aye, just past the point of wisdom…yet it is not enough. It has never been enough. “You spoke to them all?”

“All? No. Only those that would see me. They do not love me either, these highborns. To them I’ll always be the Onion Knight.” His left hand closed, stubby fingers locking into a fist; Stannis had hacked the ends off at the last joint, all but the thumb. “I broke bread with Gulian Swann and old Penrose, and the Tarths consented to a midnight meeting in a grove. The others—well, Beric Dondarrion is gone missing, some say dead, and Lord Caron is with Renly. Bryce the Orange, of the Rainbow Guard.”

“The Rainbow Guard?”

“Renly’s made his own Kingsguard,” the onetime smuggler explained, “but these seven don’t wear white. Each one has his own color. Loras Tyrell’s their Lord Commander.”

It was just the sort of notion that would appeal to Renly Baratheon; a splendid new order of knighthood, with gorgeous new raiment to proclaim it. Even as a boy, Renly had loved bright colors and rich fabrics, and he had loved his games as well. “Look at me!” he would shout as he ran laughing through the halls of Storm’s End. “Look at me, I’m a dragon,” or “Look at me, I’m a wizard,” or “Look at me, look at me, I’m the rain god.”

The bold little boy with wild black hair and laughing eyes was a man grown now, one-and-twenty, and still he played his games. Look at me, I’m a king, Cressen thought sadly. Oh, Renly, Renly, dear sweet child, do you know what you are doing? And would you care if you did? Is there anyone who cares for him but me? “What reasons did the lords give for their refusals?” he asked Ser Davos.

“Well, as to that, some gave me soft words and some blunt, some made excuses, some promises, some only lied.” He shrugged. “In the end words are just wind.”

“You could bring him no hope?”

“Only the false sort, and I’d not do that,” Davos said. “He had the truth from me.”

Maester Cressen remembered the day Davos had been knighted, after the siege of Storm’s End. Lord Stannis and a small garrison had held the castle for close to a year, against the great host of the Lords Tyrell and Redwyne. Even the sea was closed against them, watched day and night by Redwyne galleys flying the burgundy banners of the Arbor. Within Storm’s End, the horses had long since been eaten, the dogs and cats were gone, and the garrison was down to roots and rats. Then came a night when the moon was new and black clouds hid the stars. Cloaked in that darkness, Davos the smuggler had dared the Redwyne cordon and the rocks of Shipbreaker Bay alike. His little ship had a black hull, black sails, black oars, and a hold crammed with onions and salt fish. Little enough, yet it had kept the garrison alive long enough for Eddard Stark to reach Storm’s End and break the siege.

Lord Stannis had rewarded Davos with choice lands on Cape Wrath, a small keep, and a knight’s honors…but he had also decreed that he lose a joint of each finger on his left hand, to pay for all his years of smuggling. Davos had submitted, on the condition that Stannis wield the knife himself; he would accept no punishment from lesser hands. The lord had used a butcher’s cleaver, the better to cut clean and true. Afterward, Davos had chosen the name Seaworth for his new-made house, and he took for his banner a black ship on a pale grey field—with an onion on its sails. The onetime smuggler was fond of saying that Lord Stannis had done him a boon, by giving him four less fingernails to clean and trim.

No, Cressen thought, a man like that would give no false hope, nor soften a hard truth. “Ser Davos, truth can be a bitter draught, even for a man like Lord Stannis. He thinks only of returning to

King’s Landing in the fullness of his power, to tear down his enemies and claim what is rightfully his. Yet now…”

“If he takes this meager host to King’s Landing, it will be only to die. He does not have the numbers. I told him as much, but you know his pride.” Davos held up his gloved hand. “My fingers will grow back before that man bends to sense.”

The old man sighed. “You have done all you could. Now I must add my voice to yours.” Wearily, he resumed his climb.

Lord Stannis Baratheon’s refuge was a great round room with walls of bare black stone and four tall narrow windows that looked out to the four points of the compass. In the center of the chamber was the great table from which it took its name, a massive slab of carved wood fashioned at the command of Aegon Targaryen in the days before the Conquest. The Painted Table was more than fifty feet long, perhaps half that wide at its widest point, but less than four feet across at its narrowest. Aegon’s carpenters had shaped it after the land of Westeros, sawing out each bay and peninsula until the table nowhere ran straight. On its surface, darkened by near three hundred years of varnish, were painted the Seven Kingdoms as they had been in Aegon’s day; rivers and mountains, castles and cities, lakes and forests.

There was a single chair in the room, carefully positioned in the precise place that Dragonstone occupied off the coast of Westeros, and raised up to give a good view of the tabletop. Seated in the chair was a man in a tight-laced leather jerkin and breeches of roughspun brown wool. When Maester Cressen entered, he glanced up. “I knew you would come, old man, whether I summoned you or no.” There was no hint of warmth in his voice; there seldom was.

Stannis Baratheon, Lord of Dragonstone and by the grace of the gods rightful heir to the Iron Throne of the Seven Kingdoms of Westeros, was broad of shoulder and sinewy of limb, with a tightness to his face and flesh that spoke of leather cured in the sun until it was as tough as steel. Hard was the word men used when they spoke of Stannis, and hard he was. Though he was not yet five-and-thirty, only a fringe of thin black hair remained on his head, circling behind

his ears like the shadow of a crown. His brother, the late King Robert, had grown a beard in his final years. Maester Cressen had never seen it, but they said it was a wild thing, thick and fierce. As if in answer, Stannis kept his own whiskers cropped tight and short. They lay like a blue-black shadow across his square jaw and the bony hollows of his cheeks. His eyes were open wounds beneath his heavy brows, a blue as dark as the sea by night. His mouth would have given despair to even the drollest of fools; it was a mouth made for frowns and scowls and sharply worded commands, all thin pale lips and clenched muscles, a mouth that had forgotten how to smile and had never known how to laugh. Sometimes when the world grew very still and silent of a night, Maester Cressen fancied he could hear Lord Stannis grinding his teeth half a castle away.

“Once you would have woken me,” the old man said.

“Once you were young. Now you are old and sick, and need your sleep.” Stannis had never learned to soften his speech, to dissemble or flatter; he said what he thought, and those that did not like it could be damned. “I knew you’d learn what Davos had to say soon enough. You always do, don’t you?”

“I would be of no help to you if I did not,” Cressen said. “I met Davos on the stair.”

“And he told all, I suppose? I should have had the man’s tongue shortened along with his fingers.”

“He would have made you a poor envoy then.”

“He made me a poor envoy in any case. The storm lords will not rise for me. It seems they do not like me, and the justice of my cause means nothing to them. The cravenly ones will sit behind their walls waiting to see how the wind rises and who is likely to triumph. The bold ones have already declared for Renly. For Renly!” He spat out the name like poison on his tongue.

“Your brother has been the Lord of Storm’s End these past thirteen years. These lords are his sworn bannermen—”

“His,” Stannis broke in, “when by rights they should be mine. I never asked for Dragonstone. I never wanted it. I took it because

Robert’s enemies were here and he commanded me to root them out. I built his fleet and did his work, dutiful as a younger brother should be to an elder, as Renly should be to me. And what was Robert’s thanks? He names me Lord of Dragonstone, and gives Storm’s End and its incomes to Renly. Storm’s End belonged to House Baratheon for three hundred years; by rights it should have passed to me when Robert took the Iron Throne.”

It was an old grievance, deeply felt, and never more so than now. Here was the heart of his lord’s weakness; for Dragonstone, old and strong though it was, commanded the allegiance of only a handful of lesser lords, whose stony island holdings were too thinly peopled to yield up the men that Stannis needed. Even with the sellswords he had brought across the narrow sea from the Free Cities of Myr and Lys, the host camped outside his walls was far too small to bring down the power of House Lannister.

“Robert did you an injustice,” Maester Cressen replied carefully, “yet he had sound reasons. Dragonstone had long been the seat of House Targaryen. He needed a man’s strength to rule here, and Renly was but a child.”

“He is a child still,” Stannis declared, his anger ringing loud in the empty hall, “a thieving child who thinks to snatch the crown off my brow. What has Renly ever done to earn a throne? He sits in council and jests with Littlefinger, and at tourneys he dons his splendid suit of armor and allows himself to be knocked off his horse by a better man. That is the sum of my brother Renly, who thinks he ought to be a king. I ask you, why did the gods inflict me with brothers?”

“I cannot answer for the gods.”

“You seldom answer at all these days, it seems to me. Who maesters for Renly? Perchance I should send for him, I might like his counsel better. What do you think this maester said when my brother decided to steal my crown? What counsel did your colleague offer to this traitor blood of mine?”

“It would surprise me if Lord Renly sought counsel, Your Grace.” The youngest of Lord Steffon’s three sons had grown into a man bold but heedless, who acted from impulse rather than calculation. In

that, as in so much else, Renly was like his brother Robert, and utterly unlike Stannis.

“Your Grace,” Stannis repeated bitterly. “You mock me with a king’s style, yet what am I king of? Dragonstone and a few rocks in the narrow sea, there is my kingdom.” He descended the steps of his chair to stand before the table, his shadow falling across the mouth of the Blackwater Rush and the painted forest where King’s Landing now stood. There he stood, brooding over the realm he sought to claim, so near at hand and yet so far away. “Tonight I am to sup with my lords bannermen, such as they are. Celtigar, Velaryon, Bar Emmon, the whole paltry lot of them. A poor crop, if truth be told, but they are what my brothers have left me. That Lysene pirate Salladhor Saan will be there with the latest tally of what I owe him, and Morosh the Myrman will caution me with talk of tides and autumn gales, while Lord Sunglass mutters piously of the will of the Seven. Celtigar will want to know which storm lords are joining us. Velaryon will threaten to take his levies home unless we strike at once. What am I to tell them? What must I do now?”

“Your true enemies are the Lannisters, my lord,” Maester Cressen answered. “If you and your brother were to make common cause against them—”

“I will not treat with Renly,” Stannis answered in a tone that brooked no argument. “Not while he calls himself a king.”

“Not Renly, then,” the maester yielded. His lord was stubborn and proud; when he had set his mind, there was no changing it. “Others might serve your needs as well. Eddard Stark’s son has been proclaimed King in the North, with all the power of Winterfell and Riverrun behind him.”

“A green boy,” said Stannis, “and another false king. Am I to accept a broken realm?”

“Surely half a kingdom is better than none,” Cressen said, “and if you help the boy avenge his father’s murder—”

“Why should I avenge Eddard Stark? The man was nothing to me. Oh, Robert loved him, to be sure. Loved him as a brother, how often

did I hear that? I was his brother, not Ned Stark, but you would never have known it by the way he treated me. I held Storm’s End for him, watching good men starve while Mace Tyrell and Paxter Redwyne feasted within sight of my walls. Did Robert thank me? No. He thanked Stark, for lifting the siege when we were down to rats and radishes. I built a fleet at Robert’s command, took Dragonstone in his name. Did he take my hand and say, Well done, brother, whatever should I do without you? No, he blamed me for letting Willem Darry steal away Viserys and the babe, as if I could have stopped it. I sat on his council for fifteen years, helping Jon Arryn rule his realm while Robert drank and whored, but when Jon died, did my brother name me his Hand? No, he went galloping off to his dear friend Ned Stark, and offered him the honor. And small good it did either of them.”

“Be that as it may, my lord,” Maester Cressen said gently. “Great wrongs have been done you, but the past is dust. The future may yet be won if you join with the Starks. There are others you might sound out as well. What of Lady Arryn? If the queen murdered her husband, surely she will want justice for him. She has a young son, Jon Arryn’s heir. If you were to betroth Shireen to him—”

“The boy is weak and sickly,” Lord Stannis objected. “Even his father saw how it was, when he asked me to foster him on Dragonstone. Service as a page might have done him good, but that damnable Lannister woman had Lord Arryn poisoned before it could be done, and now Lysa hides him in the Eyrie. She’ll never part with the boy, I promise you that.”

“Then you must send Shireen to the Eyrie,” the maester urged. “Dragonstone is a grim home for a child. Let her fool go with her, so she will have a familiar face about her.”

“Familiar and hideous.” Stannis furrowed his brow in thought. “Still…perhaps it is worth the trying…”

“Must the rightful Lord of the Seven Kingdoms beg for help from widow women and usurpers?” a woman’s voice asked sharply.

Maester Cressen turned, and bowed his head. “My lady,” he said, chagrined that he had not heard her enter.

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

photographic magnitudes. For the Magellanic Clouds, M 33, and N.G.C. 6822, these were obtained from published star counts. For M 31, 51, 63, 81, 94, and N.G.C. 2403, they depend upon unpublished counts, for which the magnitudes were determined by comparisons with Selected Areas. For the remaining nebulae, the magnitudes of stars were estimated with varying degrees of precision, but are probably less than 0.5 mag. in error.

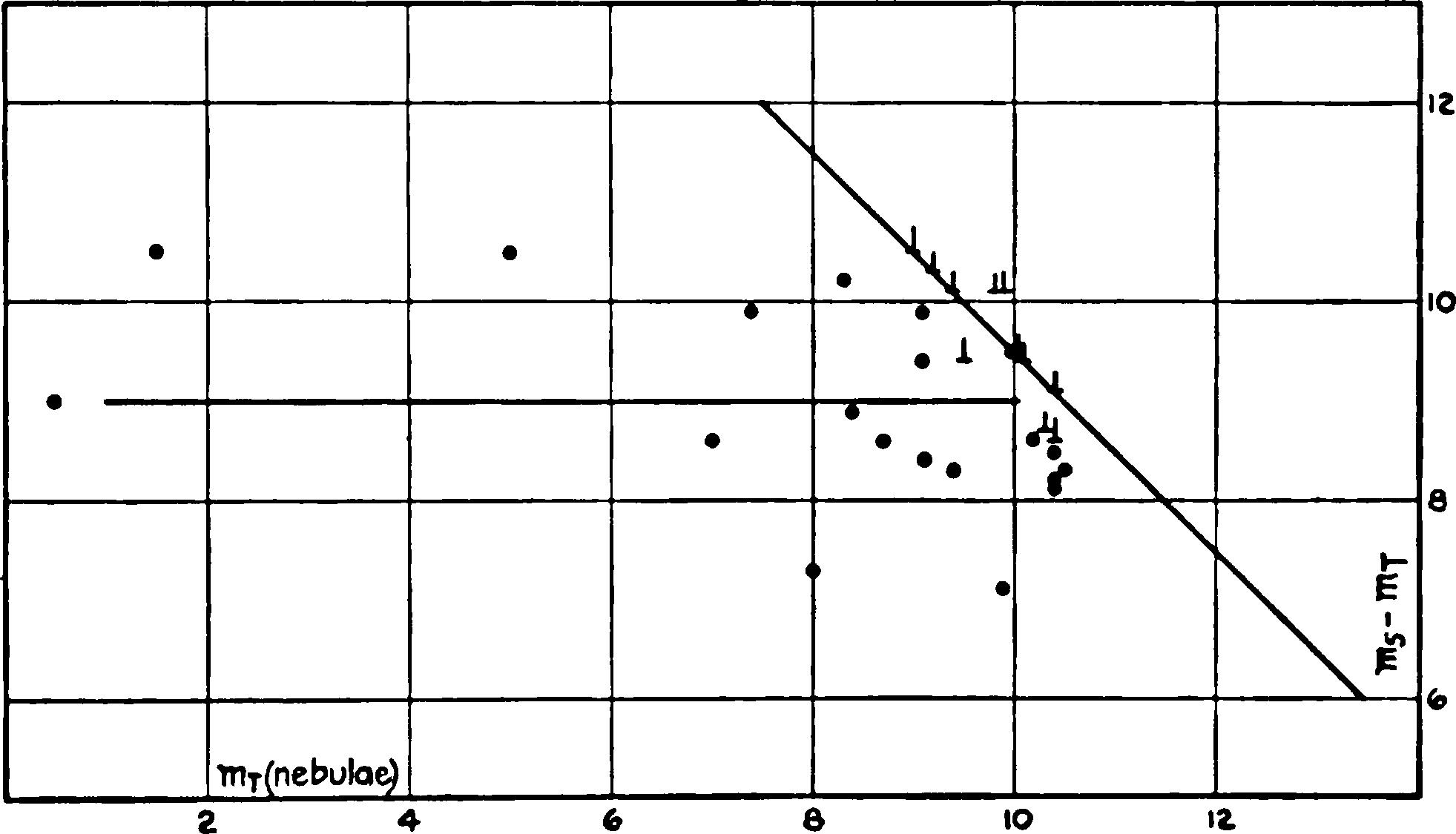

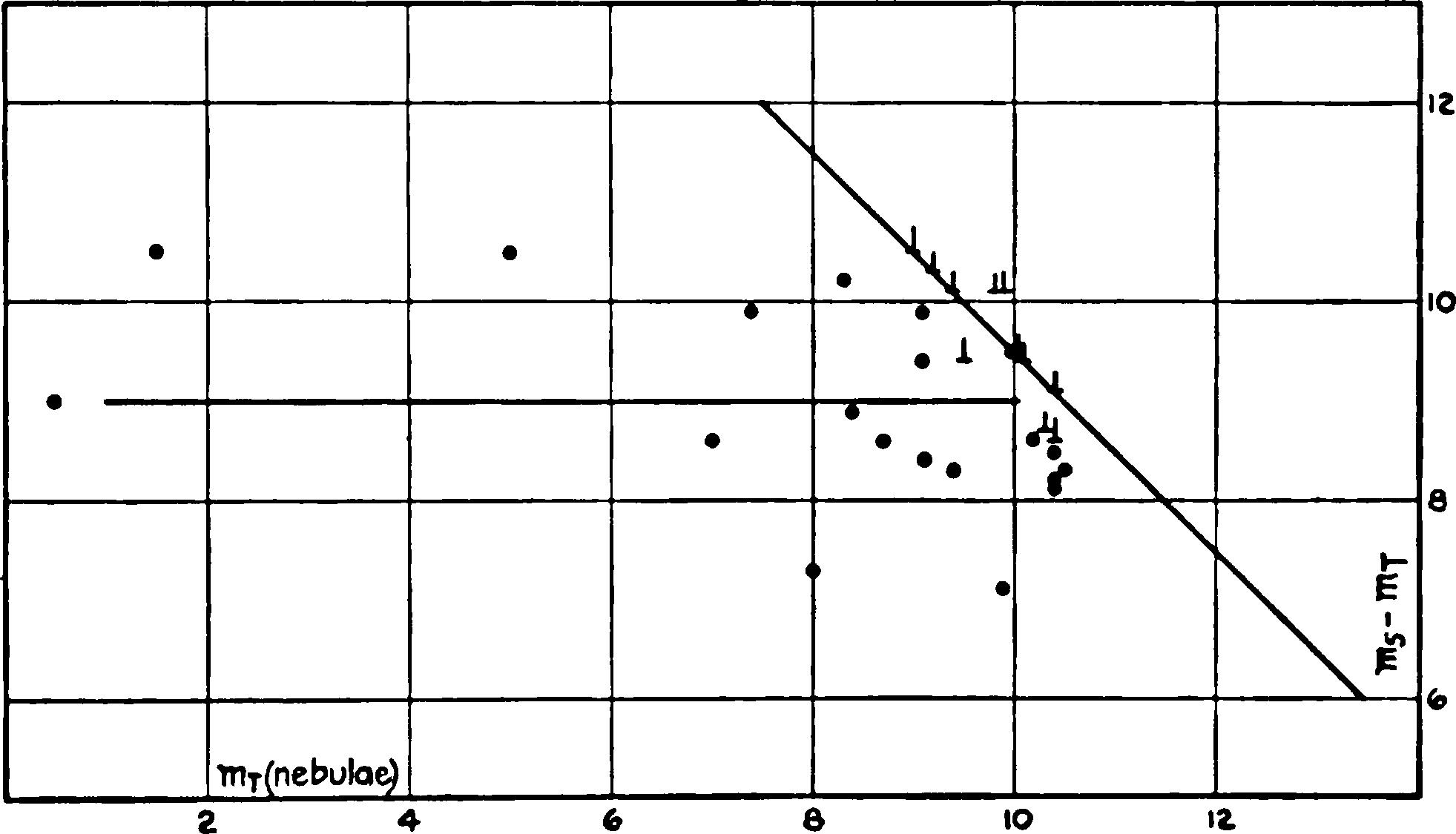

F��. 10. Relation between total magnitudes of extragalactic nebulae and magnitudes of the brightest stars involved Differences between total visual magnitudes of nebulae and the photographic magnitudes of the brightest stars are plotted against the total magnitudes The dots represent cases in which the stars could actually be detected; the incomplete crosses represent cases in which stars could not be detected, and hence give lower limits for the magnitude differences. The diagonal line indicates the approximate limits of observation, fixed by the circumstance that, in general, stars fainter than 19.5 probably would not be detected on the nebulous background.

The sloping line to the right in Figure 10 represents the limits of the observations, for, from a study of the plates themselves, it appeared improbable that stars fainter than about 19.5 could be detected with certainty on a nebulous background. Points representing nebulae in which individual stars could not be found should lie in this excluded region above the line, and their scatter is presumably comparable with that of the points actually determined below the line. When allowance is made for this inaccessible region, the data can be interpreted as showing a moderate dispersion around the mean ordinate

The range in total magnitudes is sufficiently large in comparison with the dispersion to lend considerable confidence to the conclusion. The total range of four, and the average dispersion of less than 1 mag., are comparable with those in Table XV and in Figure 7, and agree with the former in indicating a constant order of absolute magnitude.

The mean absolute magnitude of the brightest stars in the nebulae listed in Table XV, combined with the mean difference between nebulae and their brightest stars, furnishes a mean absolute magnitude of –15.3 for the nebulae listed in Table XVI. This differs by only 0.2 mag. from the average of the nebulae in Table XV, and the mean of the two, –15.2, can be used as the absolute magnitude of intermediate- and late-type spirals and irregular nebulae whose apparent magnitudes are brighter than 10.5. The dispersion is small and can safely be neglected in statistical investigations.

This is as far as the positive evidence can be followed. For reasons already given, however, it is presumed that the earlier nebulae, the elliptical and the early-type spirals, are of the same order of absolute magnitude as the later. The one elliptical nebula whose distance is known, M 32, is consistent with this hypothesis.

Conclusions concerning the intrinsic luminosities of the apparently fainter nebulae are in the nature of extrapolations of the

results found for the brighter objects. When the nebulae are reduced to a standard type, they are found to be constructed on a single model, with the total luminosities varying directly as the square of the diameters. The most general interpretation of this relation is that the mean surface brightness is constant, but the small range in absolute magnitudes among the brighter nebulae indicates that, among these objects at least, the relation merely expresses the operation of the inverse-square law on comparable objects distributed at different distances. The actual observed range covered by this restricted interpretation is from apparent magnitude 0.5 to 10.5. The homogeneity of the correlation diagrams and the complete absence of evidence to the contrary justify the extrapolation of the restricted interpretation to cover the 2 or 3 mag. beyond the limits of actual observation.

These considerations lead to the hypothesis that the nebulae treated in the present discussion are all of the same order of absolute magnitude; in fact, they lend considerable color to the assumption that extra-galactic nebulae in general are of the same order of absolute magnitude and, within each class, of the same order of actual dimensions. Some support to this assumption is found in the observed absence of individual stars in the apparently fainter late-type nebulae. If the luminosity of the brightest stars involved is independent of the total luminosity of a nebula, as is certainly the case among the brighter objects, then, when no stars brighter than 19.5 are found, the nebulae must in general be brighter than absolute magnitude mT – 25.8 where mT is the total apparent magnitude. On this assumption, the faintest of the Holetschek nebulae are brighter than –12.5 and hence of the same general order as the brighter nebulae.

Once the assumption of a uniform order of luminosity is accepted as a working hypothesis, the apparent magnitudes become, for statistical purposes, a measure of the distances. For a mean absolute magnitude of –15.2, the distance in parsecs is

DIMENSIONS OF EXTRA-GALACTIC NEBULAE

When the distances are known, it is possible to derive actual dimensions and hence to calibrate the curve in Figure 6, which exhibits the apparent diameters as a function of type, or stage in the nebular sequence, for nebulae of a given apparent magnitude. The mean maximum diameters in parsecs corresponding to the different mean types are given in Table XVII. For the elliptical nebulae, values are given both for the statistical mean observed diameters and for the diameter as calculated for the pure types.

Spirals at the last stage in the observed sequence have diameters of the order of 3000 parsecs. Assuming 1:10 as the ratio of the two axes, the corresponding volume is of the order of 1.4×109 cubic parsecs, and the mean luminosity density is of the order of 7.7 absolute magnitudes per cubic parsec as compared with 8.15 for the galactic system in the vicinity of the sun. These results agree with those of Seares who, from a study of surface brightness, concluded that the galactic system must be placed at the end of, if not actually outside, the series of known spirals when arranged according to density.19

TABLE XVII

MASSES OF EXTRA-GALACTIC NEBULAE

Spectroscopic rotations are available for the spirals M 3120 and N.G.C. 4594,21 and from these it is possible to estimate the masses on the assumption of orbital rotation around the nucleus. The distances of the nebulae are involved, however, and this is known accurately only for M 31; for N.G.C. 4594 it must be estimated from the apparent luminosity.

Another method of estimating masses is that used by Öpik22 in deriving his estimate of the distance of M 31. It is based on the assumption that luminous material in the spirals has about the same coefficient of emission as the material in the galactic system. Öpik computed the ratio of luminosity to mass for our own system in terms of the sun as unity, using Jeans’s value23 for the relative proportion of luminous to non-luminous material. The relation is

Mass = 2.6 L. (9)

The application of this method of determining orders of masses seems to be justified, at least in the case of the later-type spirals and irregular nebulae, by the many analogies with the galactic system itself. Moreover, when applied to M 31, where the distance is fairly well known, it leads to a mass of the same order as that derived from the spectrographic rotation:

MASS OF M 31

Spectrographic rotation 3 5×109 ☉ Öpik’s method 1.6×109

The distance of N.G.C. 4594 is unknown, but the assumption that it is a normal nebula with an absolute magnitude of –15.2 places it at 700,000 parsecs. The orders of the mass by the two methods are then

MASS OF N.G.C. 4594

Spectrographic rotation 2.0×109 ☉

Öpik’s method 2 6×108

Here again the resulting masses are of the same order. They can be made to agree as well as those for M 31 by the not unreasonable assumption that the absolute luminosity of the nebula is 2 mag. or so brighter than normal.

Öpik’s method leads to values that are reasonable and fairly consistent with those obtained by the independent spectrographic method. Therefore, in the absence of other resources, its use for deriving the mass of the normal nebula appears to be permissible. The result, 2.6 × 108 ☉, corresponding to an absolute magnitude of –15.2, is probably of the right order. The two test cases suggest that this value may be slightly low, but the data are not sufficient to warrant any empirical corrections.

NUMBERS OF NEBULAE TO DIFFERENT LIMITING MAGNITUDES

The numbers of nebulae to different limiting magnitudes can be used to test the constancy of the density function, or, on the hypothesis of uniform luminosities, to determine the distribution in space. The nebulae brighter than about the tenth magnitude are known individually. Those not included in Holetschek’s list are: the Magellanic Clouds, the two nebulae N.G.C. 55 and 1097, between 9.0 and 9.5 mag., and the seven nebulae N.G.C. 134, 289, 1365, 1533, 1559, 1792, and 3726, all between 9.5 and 10.0 mag.

A fair estimate of the number between 10.0 and 11.0 mag. can be derived from a comparison of Holetschek’s list with that of Hardcastle, an inspection of images on the Franklin-Adams charts and other photographs, and a correlation between known total magnitudes and the descriptions of size and brightness in Dreyer’s catalogues. It appears that very few of these objects were missed by Holetschek in the northern sky—not more than six of Hardcastle’s nebulae. For the southern sky, beyond the region observed by Holetschek, the results are very uncertain, but probable upper and

lower limits were determined as 50 and 20, respectively The brighter nebulae are known to be scarce in those regions. A mean value of 35 leads to a total 295 for the entire sky, and this is at least of the proper order.

The number of nebulae between 11.0 and 12.0 mag. can be estimated on the assumption that the two lists, Holetschek’s and Hardcastle’s, are about equally complete within this range. They are known to be comparable for the brighter nebulae, and, moreover, the total numbers included in the two lists for the same area of the sky, that north of declination –10°, are very nearly equal—400 as compared with 408. The percentages of Holetschek’s nebulae included by Hardcastle were first determined as a function of magnitude. Within the half-magnitude interval 11.0 to 11.5, for instance, 60 per cent are in Hardcastle’s list. If the two lists are equally complete and, taken together, are exhaustive, the total number in the interval will be 1.4 times the number of Holetschek’s nebulae. The latter is found to be 50 from smoothed frequency curves of the magnitudes listed in Tables I–IV. The total number north of –10° is therefore 70. This can be corrected to represent the entire sky by applying the factor 1.75, which is the ratio of the total number of Hardcastle’s nebulae, 700, to the number north of –10°, 400. In this manner a reasonable estimate of 123 is obtained for the number of nebulae in the entire sky between 11.0 and 11.5 mag. Similarly, between 11.5 and 12.0, where 50 per cent of Holetschek’s nebulae are included in Hardcastle’s list, the total number for the entire sky is found to be 236.

The greatest uncertainty in these figures arises from the assumption that the two lists together are complete to the twelfth magnitude. The figures are probably too small, but no standards are available by which they can be corrected. It is believed, however, that the errors are certainly less than 50 per cent and probably not more than 25 per cent. This will not be excessive in view of the possible deviations from uniform distribution where so limited a number of objects is considered.

Beyond 12.0 mag. the lists quickly lose their aspect of completeness and cannot be used for the present purpose. There

are available, however, the counts by Fath24 of nebulae found on plates of Selected Areas made with the 60-inch reflector at Mount Wilson. The exposures were uniformly 60 minutes on fast plates and cover the Areas in the northern sky down to and including the –15° zone. The limiting photographic magnitudes for stars average about 18.5. The counts have been carefully revised by Seares25 and are the basis for his estimate of 300,000 nebulae in the entire sky down to this limit.

Approximate limiting total magnitudes for the nebulae in two of the richest fields, S.A. 56 and 80, have been determined from extrafocal exposures with the 100-inch reflector. The results are 17.7 in each case, and this, corrected by the normal color-index of such objects, gives a limiting visual magnitude of about 16.7, which can be used for comparison with the counts of the brighter nebulae.

The various data are collected in Table XVIII, where the observed numbers of extra-galactic nebulae to different limits of visual magnitude are compared with those computed on the assumption of uniform distribution of objects having a constant absolute luminosity. The formula used for the computation is

where the constant is the value of log N for mT = 0. The value —4.45 is found to fit the observational data fairly well.

The agreement between the observed and computed log N over a range of more than 8 mag. is consistent with the double assumption of uniform luminosity and uniform distribution or, more generally, indicates that the density function is independent of the distance.

The systematic decrease in the residuals O – C with decreasing luminosity is probably within the observational errors, but it may also be explained as due to a clustering of nebulae in the vicinity of the galactic system. The cluster in Virgo alone accounts for an appreciable part. This is a second-order effect in the distribution, however, and will be discussed at length in a later paper.

TABLE XVIII

Distances corresponding to the different limiting magnitudes, as derived from formula (8), are given in the last column of Table XVIII. The 300,000 nebulae estimated to the limits represented by an hour’s exposure on fast plates with the 60-inch reflector appear to be the inhabitants of space out to a distance of the order of 2.4 × 107 parsecs. The 100-inch reflector, with long exposures under good conditions, will probably reach the total visual magnitude 18.0, and this, by a slight extrapolation, is estimated to represent a distance of the order of 4.4×107 parsecs or 1.4×108 light-years, within which it is expected that about two million nebulae should be found. This seems to represent the present boundaries of the observable region 3 of space.

DENSITY OF SPACE

The data are now available for deriving a value for the order of the density of space. This is accomplished by means of the formulae for the numbers of nebulae to a given limiting magnitude and for the distance in terms of the magnitude. In nebulae per cubic parsec, the density is

This is a lower limit, for the absence of nebulae in the plane of the Milky Way has been ignored. The current explanation of this phenomenon in terms of obscuration by dark clouds which encircle the Milky Way is supported by the extra-galactic nature of the nebulae, their general similarity to the galactic system, and the frequency with which peripheral belts of obscuring material are encountered among the spirals. The known clouds of dark nebulosity are interior features of our system, and they do not form a continuous belt. In the regions where they are least conspicuous, however, the extra-galactic nebulae approach nearest to the plane of the Milky Way, many being found within 10°. This is consistent with the hypothesis of a peripheral belt of absorption.

The only positive objection which has been urged to this explanation has been to the effect that the nebular density is a direct function of galactic latitude. Accumulating evidence26 has failed to confirm this view and indicates that it is largely due to the influence of the great cluster in Virgo, some 15° from the north galactic pole. There is no corresponding concentration in the neighborhood of the south pole.

If an outer belt of absorption is assumed, which, combined with the known inner clouds, obscures extra-galactic nebulae to a mean distance of 15° from the galactic plane, the value derived for the density of space must be increased by nearly 40 per cent. This will not change the order of the value previously determined and is within the uncertainty of the masses as derived by Öpik’s method. The new value is then

ρ = 9×10–18 nebulae per cubic parsec. (12)

The corresponding mean distance between nebulae is of the order of 570,000 parsecs, although in several of the clusters the distances between members appear to be a tenth of this amount or less.

The density can be reduced to absolute units by substituting the value for the mean mass of a nebula, 2.6×108 ☉. Then, since the mass of the sun in grams is 2×1033 and 1 parsec is 3.1×1018 cm,

ρ = 1.5×10–31 grams per cubic centimeter. (13)

This must be considered as a lower limit, for loose material scattered between the systems is entirely ignored. There are no means of estimating the order of the necessary correction. No positive evidence of absorption by inter-nebular material, either selective or general, has been found, nor should we expect to find it unless the amount of this material is many times that which is concentrated in the systems.

THE FINITE UNIVERSE OF GENERAL RELATIVITY

The mean density of space can be used to determine the dimensions of the finite but boundless universe of general relativity. De Sitter27 made the calculations some years ago, but used values for the density, 10–26 and greater, which are of an entirely different order from that indicated by the present investigations. As a consequence, the various dimensions, both for spherical and for elliptical space, were small as compared with the range of existing instruments.

For the present purpose, the simplified equations which Einstein has derived for a spherically curved space can be used.28 When R, V, M, and ρ represent the radius of curvature, volume, mass, and density, and k and c are the gravitational constant and the velocity of light,

Substituting the value found for ρ, 1.5×10–31 , the dimensions become

R = 8.5×1028 cm = 2.7×1010 parsecs, (17)

V = 1.1×1088 cm = 3.5×1032 cubic parsecs, (18)

M = 1.8×1057 grams = 9×1022 ☉. (19)

The mass corresponds to 3.5×1015 normal nebulae.

The distance to which the 100-inch reflector should detect the normal nebula was found to be of the order of 4.4×1075 parsecs, or about ¹⁄��� the radius of curvature. Unusually bright nebulae, such as M 31, could be photographed at several times this distance, and with reasonable increases in the speed of plates and size of telescopes it may become possible to observe an appreciable fraction of the Einstein universe.

M���� W����� O���������� September 1926

1 Contributions from the Mount Wilson Observatory, No 324

2 These are the two Magellanic Clouds, M 31, and M 33

3 Bailey, Harvard Annals, 60, 1908

4 Hardcastle, Monthly Notices, 74, 699, 1914.

5 This estimate by Seares is based on a revision of Fath’s counts of nebulae in Selected Areas (Mt. Wilson Contr., No. 297; Astrophysical Journal, 62, 168, 1925).

6 “A General Study of Diffuse Galactic Nebulae,” Mt. Wilson Contr., No. 241; Astrophysical Journal, 56, 162, 1922.

7 The classification was presented in the form of a memorandum to the Commission on Nebulae of the International Astronomical Union in 1923. Copies of the memorandum were distributed by the chairman to all members of the Commission. The classification was discussed at the Cambridge meeting in 1925, and has been published in an account of the meeting by Mrs Roberts in L’Astronomie, 40, 169, 1926 Further consideration of the matter was left to a subcommittee, with a resolution that the adopted system should be as purely descriptive as possible, and free from any terms suggesting order of physical development (Transactions of the I A U , 2, 1925) Mrs Roberts’ report also indicates the preference of the Commission for the term “extragalactic” in place of the original, and then necessarily noncommittal, “non-galactic.”

Meanwhile K Lundmark, who was present at the Cambridge meeting and has since been appointed a member of the Commission, has recently published (Arkiv für Matematik, Astronomi och Fysik, Band 19B, No 8, 1926) a classification, which, except for nomenclature, is practically identical with that submitted by me Dr Lundmark makes no acknowledgments or references to the discussions of the Commission other than those for the use of the term “galactic.”

8 Problems of Cosmogony and Stellar Dynamics, 1919.

9 N.G.C. 4486 (M 87) may be an exception. On the best photographs made with the 100-inch reflector, numerous exceedingly faint images, apparently of stars, are found around the periphery. It was among these that Belanowsky’s nova of 1919 appeared. The observations are described in Publications of the Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 35, 261, 1923.

10 “Early” and “late,” in spite of their temporal connotations, appear to be the most convenient adjectives available for describing relative positions in the sequence. This sequence of structural forms is an observed phenomenon. As will be shown later in the discussion, it exhibits a smooth progression in nuclear luminosity, surface brightness, degree of flattening, major diameters, resolution, and complexity An antithetical pair of adjectives denoting relative positions in the sequence is desirable for many reasons, but none of the progressive characteristics are well adapted for the purpose Terms which apply to series in general are available, however, and of these “early” and “late” are the most suitable. They can be assumed to express a progression from simple to complex forms.

An accepted precedent for this usage is found in the series of stellar spectral types There also the progression is assumed to be from the simple to the complex, and in view of the great convenience of the terms “early” and “late,” the temporal connotations, after a full consideration of their possible consequences, have been deliberately disregarded

11 Publications of the Lick Observatory, 13, 12, 1918.

12 Hβ is brighter than N2. Patches with similar spectra are often found in the arms of late-type spirals N.G.C. 253, M 33, M 101. The typical planetary spectrum, where Hβ is fainter than N2, is found in the rare cases of apparently stellar nuclei of spirals; for instance, in N G C 1068, 4051, and 4151 Here also the emission spectra are localized and do not extend over the nebulae

13 Monthly Notices. 74, 699, 1914.

14 Annalen der Wiener Sternwarte, 20, 1907.

15 Astronomische Nachrichten, 214, 425, 1921.

16 Publications of the Lick Observatory, 13, 1918.

17 Since C is constant for all nebulae in a given class, the linear relation between Δ log d and C for the different classes is something more than a mere geometrical relation arising from the observed equality of the mean mT in the various classes.

18 This is apparent even among the observed classes Referring to formula (3), mT + 5 log b will be constant in so far as Ce + 5 log (1 – e) is constant The following table indicates that the latter term is approximately constant throughout the sequence of elliptical nebulae. The values of Ce were read from the smooth curve in Fig. 6.

19 Mt Wilson Contr , No 191; Astrophysical Journal, 52, 162, 1920

20 Pease, Mt Wilson Comm , No 51; Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 4, 21, 1918

21 Pease, Mt Wilson Comm , No 32: ibid , 2, 517, 1916

22 Astrophysical Journal, 55, 406, 1922

23 Monthly Notices, 82, 133, 1922.

24 Astronomical Journal, 28, 75, 1914.

25 Mt. Wilson Contr., No. 297; Astrophysical Journal, 62, 168, 1925.

26 The latest and most reliable results bearing on the distribution of faint (hence apparently distant) nebulae are found in Seares’s revision and discussion of the counts made by Fath on plates of the Selected Areas with the 60-inch reflector. When the influence of the cluster in Virgo is eliminated the density appears to be roughly uniform for all latitudes greater than about 25°.

27 Monthly Notices, 78, 3, 1917.

28 Haas, Introduction to Theoretical Physics, 2, 373, 1925.

Text notes:

Transcriber’s Notes

1 For the HTML version, page numbers of the original printed text are displayed within braces to the side of the text. The numbers have been remapped to start at page 1.

2 Footnotes have been renumbered and moved to the end of the paper

3. Tables have been moved to avoid splitting paragraphs. In some cases the tables have been reconfigured or split in order to work better with e-readers. As a result, page numbers may not be accurate for tables and adjacent text.

4. Some of the mathematical equations were created using TeX notation that was converted into SVG images via the tex2svg function in MathJax. The Tex notation is contained in the plain text version.

5 Except as mentioned above every effort has been made to replicate this text as faithfully as possible, including non-standard punctuation, inconsistently hyphenated words, etc.

6 The original printed text is available from HathiTrust at: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.b3805680 (see pg 353).

7. The outline “CLASSIFICATION OF NEBULAE” starting on page 3 lists N.G.C. 2117 as a type E7 nebula. The version of this paper printed in Contributions from the Mount Wilson Observatory No. 324 lists N.G.C 3115. Otherwise the papers are essentially identical.

*** END OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EXTRAGALACTIC NEBULAE ***

Updated editions will replace the previous one—the old editions will be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG™ concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you charge for an eBook, except by following the terms of the trademark license, including paying royalties for use of the Project Gutenberg trademark. If you do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the trademark license is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and research. Project Gutenberg eBooks may be modified and printed and given away—you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE