Self Made 2nd Edition Tara Isabella Burton

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/self-made-2nd-edition-tara-isabella-burton/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Hide and Seek The Psychology of Self Deception Neel

Burton

https://textbookfull.com/product/hide-and-seek-the-psychology-ofself-deception-neel-burton/

Superannuation Made Simple 2nd Edition Noel Whittaker

https://textbookfull.com/product/superannuation-made-simple-2ndedition-noel-whittaker/

Clinical Atlas of Small Animal Cytology and Hematology, 2nd Edition

Burton

https://textbookfull.com/product/clinical-atlas-of-small-animalcytology-and-hematology-2nd-edition-burton/

South Africa Culture Smart The Essential Guide to Customs Culture 2nd Edition Isabella Morris

https://textbookfull.com/product/south-africa-culture-smart-theessential-guide-to-customs-culture-2nd-edition-isabella-morris/

Crushing Over My Best Friend s Older Brother Forbidden

1st Edition Tara Brent Brent Tara

https://textbookfull.com/product/crushing-over-my-best-friend-solder-brother-forbidden-1st-edition-tara-brent-brent-tara/

BASICS Design Barrier Free Planning Isabella Skiba

https://textbookfull.com/product/basics-design-barrier-freeplanning-isabella-skiba/

Fated Maid Intergalactic Fated Mates 4 1st Edition

Athena Storm Tara Starr Storm Athena Starr Tara

https://textbookfull.com/product/fated-maid-intergalactic-fatedmates-4-1st-edition-athena-storm-tara-starr-storm-athena-starrtara/

The Self-Sabotage Behavior Workbook 2nd Edition Candice

Seti

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-self-sabotage-behaviorworkbook-2nd-edition-candice-seti/

Gilded Cage Complete Series Box Set 1st Edition

Isabella Starling

https://textbookfull.com/product/gilded-cage-complete-series-boxset-1st-edition-isabella-starling/

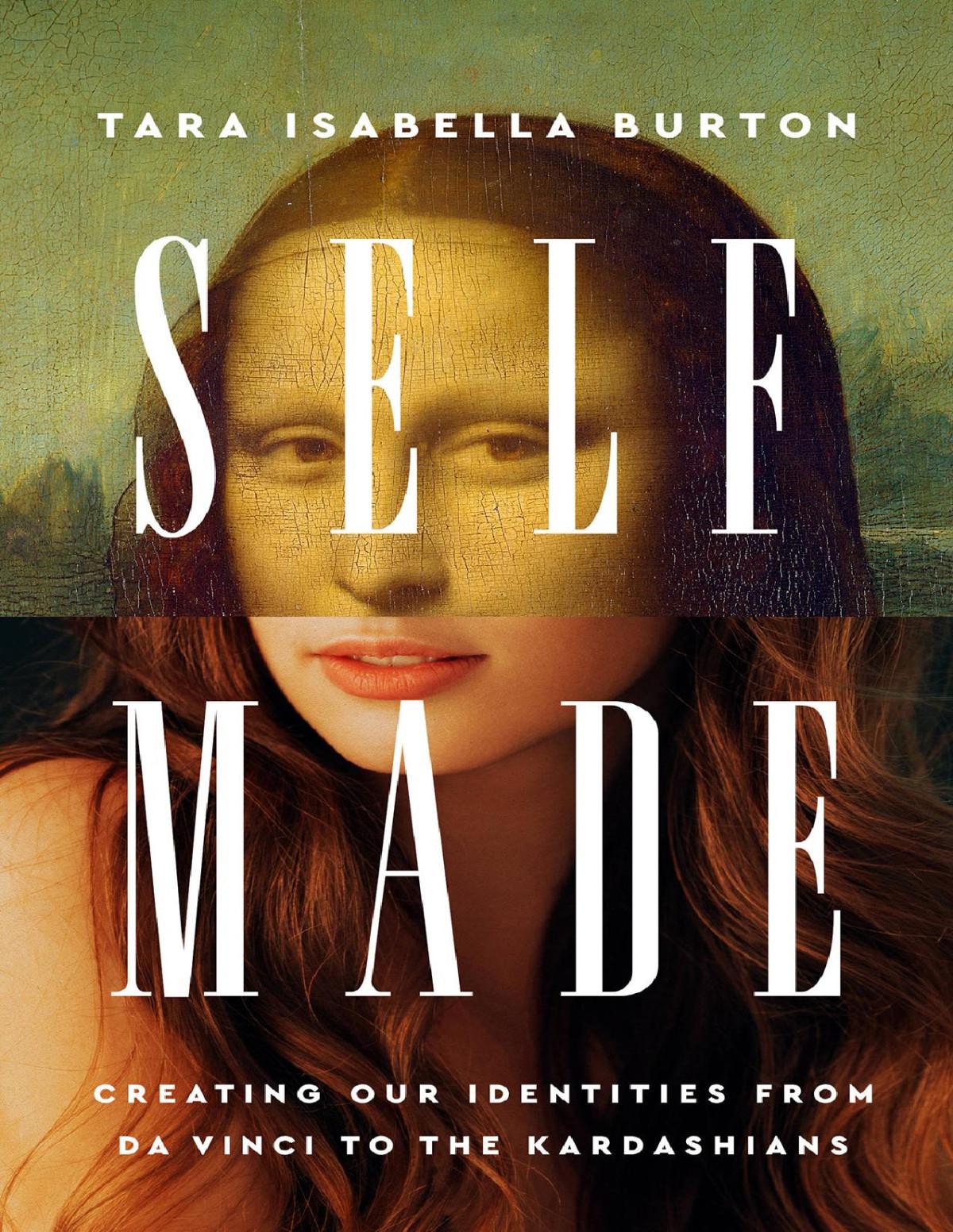

Copyright © 2023 by Tara Isabella Burton

Cover designby Pete Garceau

Cover images: Mona Lisa/Public domain,Photographof woman© iStock/Getty Images

Cover copyright © 2023 by Hachette Book Group,Inc.

Hachette Book Groupsupports the right to free expressionandthe value ofcopyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers andartists to produce the creative works that enrichour culture.

The scanning,uploading,anddistributionofthis book without permissionis a theft ofthe author’s intellectual property. Ifyouwouldlike permissionto use material fromthe book (other thanfor review purposes),please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank youfor your support ofthe author’s rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue ofthe Americas,New York,NY 10104 www.publicaffairsbooks.com @Public_Affairs

First Edition: June 2023

Publishedby PublicAffairs,animprint ofPerseus Books, LLC,a subsidiary ofHachette Book Group,Inc. The PublicAffairs name andlogo is a trademark ofthe Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureauprovides a wide range of authors for speakingevents. To findout more,go to

www.hachettespeakersbureau.comor email HachetteSpeakers@hbgusa.com.

PublicAffairs books may be purchasedinbulk for business,educational,or promotionaluse. For more information,please contact your localbookseller or the Hachette Book GroupSpecialMarkets Department at special.markets@hbgusa.com.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not ownedby the publisher.

Library ofCongress Cataloging-in-PublicationData has beenappliedfor.

ISBNs: 9781541789012 (hardcover),9781541789005 (ebook)

E3-20240118-JV-PC-VAL

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright Dedication

INTRODUCTION: HOW WE BECAME GODS?

one – “STAND UP FOR BASTARDS”

two – “SHAKING OFF THE YOKE OF AUTHORITY”

three – “A SNEER FOR THE WORLD”

four – “WORK! WORK!! WORK!!!”

five – “LIGHT CAME IN AS A FLOOD”

six – “THE DANDY OF THE UNEXPECTED”

seven – “I SHALL BE RULING THE WORLD FROM NOW ON”

eight – THE POWER OF IT

nine – “YOU BASICALLY JUST SAID YOU WERE”

ten – “DO IT YOURSELF”

eleven – “BECAUSE I FELT LIKE IT”

EPILOGUE: “HOW TO BE YOURSELF”

Acknowledgments

Discover More

Notes

Praise for Self-Made

ForDhananjay,whochallengesanddelightsmedaily

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

INTRODUCTION: HOW WE BECAME GODS?

IN JANUARY 2020, HIGH-END FITNESS CHAIN EQUINOX DEBUTED

one of its most lavish advertising campaigns, titled “Make Yourself a Gift to the World.” Produced by marketing studio Droga5, the billboards and posters featured implausibly beautiful, artistically rendered young men and women evoking mythological demigods of ages past. In one poster, a powerful-lookingwomaneasily lifts two men, Samsonstyle. In another, a shirtless man lies on a funeral dais, attended by frenetic worshippers. According to Droga5, the campaign is supposed to depict “divine characters as god-like ‘gifts to the world’ in moments and situations that reflect their selfworshipasservinga larger purpose to humanity.”1

The campaign’s commercial takes this theme of divine selfobsession even further. Retelling the story of Narcissus—the infamously beautiful Greek demigod who fell in love with his own reflection in a pond and subsequently drowned trying to reach him—the film turns the myth’s moral warning on its head. Self-obsession, a campily costumed narrator tells us, turns Narcissus into “a gift not just for him to treasure, but a gift that brought the whole world pleasure.” (This Narcissus survives and starts a dance party.) With a wink to the viewer, the narrator asks us: “Does that not make self-obsession the most selflessact ofall?”

The message of the advertisements is clear. Join an Equinox gym—where prices start at $250 a month and membersare lockedinto yearlongcontracts—andyoutoo can become God’s gift to the world, or maybe even a kind of god yourself. “We’re targeting individuals dedicated to becoming the very best they can be,” Equinox’s chief marketer told one

skeptical journalist. “We believe that when you become the best version of yourself, you radiate outward and contribute more to the worldaroundyou.”2

The ad campaign—like many of Equinox’s high-fashioninspired commercials—is, of course, deliberately transgressive and more than a little tongue-in-cheek. But the worldview it represents—that shaping yourself, through both muscular discipline and aesthetic creativity, is the highest calling imaginable—is not limited to Equinox or even to the wider boutique wellness culture. Rather, the idea that we are self-makers is encoded into almost every aspect of Western contemporary life. We not only canbut shouldcustomize and create and curate every facet of our lives to reflect our inner truth. We are all in thrall to the seductive myth that we are supposedto become our best selves.

In the economic sphere, we valorize self-made men and women. Entrepreneurs like Apple founder Steve Jobs and media mogul Oprah Winfrey rose from humble or deprived backgrounds to become billionaires or celebrities. These figures—our culture tells us—took control of their destinies through some combination of skill and good old-fashioned grit. Refusing to accept the circumstances into which they were born, they decided for themselves the lives they would lead. The narrative of the man (or woman) who pulls themselves up by their bootstraps, and who therefore deserves the fortune and fame they achieve, is a foundational part of the capitalist American dream. This myth, in turn, has shaped how Americans—and those across the globe whose ideologies are shaped by American cultural hegemony—think about,andlegislate,our wider economic system.

But the fantasy of self-creationis also integral to our wider culture. We live, after all, in a social-media-saturated era where more and more of our most notable celebrities are “influencers.” They present not only their work but their meticulously curated personal lives for public consumption and private profit. Even those of us who aren’t necessarily

looking to land a brand partnership or to post sponsored content on our Instagram pages are likely to have encountered the need to create or cultivate our “personal brands.” More and more of us work to ensure that our social media presence reflects the way we want others to see us, whether we’re using it for professional reasons, personal ones,or a mixofthe two.

Our cultural moment—in the contemporary Englishspeaking world, at least—is one in which we are increasingly called to be self-creators: people who yearn not just to make ourselvesa gift to the worldbut to make ourselves,period.

Our economic, cultural, and personal lives are suffused with the notion that we can and should transform ourselves into modern-day deities, simultaneously living works of art to be admired by others and ingeniously productive economic machines. If we have ultimate control over own lives, after all,whynot use thisto our advantage?

At the core of this collective project of self-creation lies one vital assumption. We can find it everywhere from Equinox’s clarioncallto become divine narcissists to the nowubiquitous life coaches and personal growth classes that claim they can help us self-actualize or “become who we reallyare.”

That assumption? That who we are—deep down, at our most fundamental level is who we most want to be. Our desires, our longings, our yearning to become or to acquire or to be seen a certain way, these are the truest and most honest parts of ourselves. Where and how we were born, the names, expectations, and assumptions laid upon us by our parents, our communities, and our society at large? All these are at best incidental to who we really are, at worst actively inimical to our personal development. It is only by looking inward—by investigating, cultivating, and curating our inner selves—that we can understand our fundamental purpose in this life and achieve the personal and professional goals we believe we were meant to achieve.

Taken to its logical conclusion, this assumption means that we are most realwhen we present ourselves to the world as the people we most want to become. Our honest selves are the ones we choose and create. We can no longer tell where reality ends and fantasy begins. Or, as one of history’s most famous self-creators, the writer and consummate dandy Oscar Wilde, notoriously put it: “Give [a man] a mask, and he willtellyouthe truthfromanother point ofview.”3

From this perspective, self-making isn’t just an act of creativity, or even of industry. It’s also an act of selfexpression: of showing the world who we truly are by making the worldsee us as who we want to be. Self-creation, inother words,iswhere artificialityandauthenticitymeet.

The storyofSelf-Madeisthe storyofhow we got here.

IT IS THE story of some of modern history’s most famous and eccentric self-makers: from Renaissance geniuses and Civil War abolitionists to Gilded Age capitalists and Warhol’s Factory girls. These luminaries didn’t just transcend their origins or circumstances; they also charted a new path for others to do the same. But the history of self-makingwas also written by some of the modern era’s most notorious charlatans: unscrupulous self-help gurus, con artists, and purveyors of what circus impresario P. T. Barnum called “humbug.” These charismatic upstarts understoodone of selfmaking’s most fundamental principles: that self-invention was as much about shaping people’s perceptions of you as it was about changinganythingabout yourself.

Self-Madeis also the story of how the social upheavals and technological transformations of the early modern period helped usher in two parallel narratives of what self-making looked like. In one—largely European—narrative, self-making was something available to a very particular, very special

kind of person. A natural “aristocrat,” which is to say not necessarily someone of high birth but rather of graceful wit or bulging muscles or artistic creativity, could use his innate ability to determine his own life to set himself above the common bourgeois herd. In another—predominately American—story, self-making was something anyone could do, so long as they put in sufficient amounts of grit and elbow grease. Conversely, if they failed to do so, that meant they were lacking on an existential as well as pragmatic level. These two narratives, more similar than they might at first glance appear, converged in the twentieth century, with the rise of Hollywood and a new image of what mass-market stardom—simultaneously innate and self-taught—could look like.

AS WE SHALL see, both of these narratives ultimately come from the same place: a radical, modern reimagining of the nature of reality, humans’ place in it, and, even more significantly, of who or what “created” humanity to begin with. Our faith in the creative and even magical power of the self-fashioningselfgoeshandinhandwiththe decline inbelief in an older model of reality: a God-created and God-ordered universe in which we all have specific, preordained parts to play—from peasants to bishops to kings—based on the roles into whichwe are born.

The philosopher Charles Taylor famously characterized this intellectual transition as a shift into a secular age. We have moved away from spiritual belief and enchantment and toward (perceived) rationality. We have entered an era of what he calls“expressive individualism,” or the sense that our internal image of ourselves has become a kind of compass for who we really are. And I agree with Taylor’s ultimate diagnosis that expressive individualism dominates how we

think about ourselves in modern life. But I disagree that this shift represents a move from a religious worldview to a secular one.

Rather, I believe we have not so much done away with a belief in the divine as we have relocated it. We have turned our backsonthe idea ofa creator-God,outthere,andinstead placed God withinus—more specifically, within the numinous force of our own desires. Our obsession with self-creation is also an obsession with the idea that we have the power that we once believed God did: to remake ourselves and our realities, not in the image of God but in that of our own desires.

This sense that there might be something magical, even divine, about our hunger to become our best, wealthiest, or most successful selves is not a new one. Even the most atheistic accounts of human existence, like those of Friedrich Nietzsche, make room for something special, something distinct, even something enchanted in the human will. Yet plenty of other accounts—like the New Thought spiritual movement that animated and legitimized so much of Gilded Age capitalism with the idea that thinking hard enough could bring you wealth or riches—treated human desire as not just a powerful force but an explicitly supernatural one. It was a way in which human beings connected with a fundamental energy inthe universe, one directedtowardour ownpersonal happiness and fulfillment. In each version of the narrative, however, our humandesires—to strive, to seek, to have, to be —double as the animating power: that against which our materialandsocialrealityisjudged.

In this way, we might say, we have become gods, no less than Equinox’s Narcissus. And, as the guilt-tripping, get-offthe-sofa-and-into-the-gym subtext of Equinox’s advertisement suggests, self-creation has become something that all of us are not just encouraged but required to do. All of us have inherited the narrative that we must shape our own path and place inthislife andthat where andhow we were bornshould

not determine who and what we will become. But we have inherited, too, this idea’s dark underbelly: if we do not manage to determine our own destiny, it means that we have failed in one of the most fundamental ways possible. We have failedat what it meansto be humaninthe first place.

FROM ONE PERSPECTIVE, this story of humanself-divinizationis an empowering tale of progress and liberation from tyranny and superstition. It is the story of the brave philosophes of the European Enlightenment who dared to stand up to the abuses and the excesses of the Catholic Church and corrupt French monarchy. It is the story of the rise of liberal democracy in Europe and the founding of the United States on the ideal that all of us have a right to liberty and the pursuit of happiness. It is the story of the American dream espoused by figures like Frederick Douglass and Benjamin Franklin—that withenoughhardwork anda bit ofgrit anyone from any race or class could become a self-made man. It is the story, too, of the liberation of other marginalized people, particularly of the queer writers and artists, from Oscar Wilde to Warhol muse Jackie Curtis, who foundinthe promise of artistic self-creation relief and reprieve from a world that alltoo oftendeemedthemunnatural.

This narrative is true, at least in part. Certainly, many of the writers, artists, and thinkers profiled in this book have made heroic efforts toward making a better and more equal world.

But it is also true that this new idea of self-creation has, as often as not, been used by its proponents to divide those who had the “right” to shape their identities (generally speaking, white, middle-class men who sought an upper-class life) from those who didnot (minorities,women,the genuinelypoor).

InEurope,where what I callthe “aristocratic” strainofthe self-making myth took hold, the power to self-create was largely understood as something innate. Special people—the dandies and possessors of bon ton, or grace—were born with it, but most of the ordinary rabble did not possess it. This strain found its zenith in the personality cults of twentiethcentury protofascist and fascist leaders like Gabriele D’Annunzio and Benito Mussolini, who peddled the fantasy of superhumanspecialness to a populationalltoo willingto treat their neighbors as subhuman. In America, where the “democratic” strain of the myth took hold, self-creation soon became a handy way to discount the poor and suffering for simplynot workinghardenough.

Inbothcases, the promise of self-makingfunctionedless as a straightforward path to liberation than as a means of preserving the status quo. It helped to legitimize the uncomfortable truth that, even as society was changing to allow some people to define their own lives, others were relegated to the status of psychic underclass: incapable of self-makingdue to either innate inferiority or else plainmoral laziness. It will not be lost on the reader that the majority (though by no means all) of the prophets and paradigms of self-making featured in this book—at least until the twentieth century—are white andmale.

ULTIMATELY, OUR HISTORY of self-creation is not an inspiring tale of unremitting progress. But I do not think it is a tragic narrative about culturaldecline andthe dangersofmodernity, suchas we have seeninthe accounts ofrecent culturalcritics from Philip Rieff to Carl Trueman. Rather, Self-Made is an account of how we began to think of ourselves as divine beings in an increasingly disenchanted world and about the consequences—political, economic, and social—of that

thinking. These consequences have both liberated us from some forms of tyranny and placed us into the shackles of others. It is a story,inother words,about humanbeings doing what we have always done: tryingto solve the mystery ofhow to live as beings both dazzlingly powerful and terrifyingly vulnerable, thrust without our consent into a world whose purpose andmeaningwe maynever be able to trulyknow.

“What a piece of work is a man!” Shakespeare’s Hamlet mused, sometime around 1600. “How noble in reason! How infinite in faculty!… In action how like an angel! In apprehension how like a god!” And, at the same time, he is nothingbut a “quintessence ofdust.”

More than four hundred years later, we’re still wrestling with Hamlet’s contradictions, asking ourselves what it means to be our “true self” anyway.

Self-Madeisthe storyofone ofour stillimperfect answers.

“STANDUPFORBASTARDS”

ON APRIL 8,1528, A WORSHIPPER STOLE A SACRED RELIC FROM aNurembergcorpse. The actwasnotanuncommonone.AllthroughoutmedievalEurope,devoteeshadoftengoneto extremelengthstosecurethebonesorotherbodypartsoffavoredsaints.Therehadbeen thetwelfth-centuryBritishbishopwhohadallegedlybittenoffapieceofMaryMagdalene’s handwhile genuflectingbefore it ona visit to a Frenchmonastery AFrenchmonk,three centuriesearlier,hadspentafulldecadeundercoveratarivalmonasterytosecuretheskull ofSainte-Foy.

But the luscious, S-shaped lock of golden hair one mourner surreptitiously sliced that Aprilbelongednottoanysaint,or eventoanyoneparticularlyholy. Rather,itbelongedto thenotoriouspainter,printmaker,anddevastatinglygood-lookingbonvivantAlbrechtDürer.

By the time of his death, Dürer had become one of the most famous artists of the European Renaissance And his funeral proceedings were worthy of the celebrity he had become Within three days of Dürer’s death, his body was exhumed, allowing his many admirers to cast a wax death mask of the alluring face one contemporary had lauded as “remarkable inbuildandstature andnot unworthy of the noble mindit contained.”1 The lock of hair—cut by an anonymous mourner—was ultimately delivered into the hands of Dürer’sfriendandsometimerivalHansBaldung,whoheldontoituntilhisdeath

The writers, too, were honing their elegies German humanist poet Helius Eobanus Hessushadstartedworkonaseriesoffunerarypoems,declaimingofthelatepainterthat “all who will be famous in your art will mourn / this is the honor that they owe you.”2 Admirers began to make and disseminate copies of the unremarkable family history that Dürer—like many members of Nuremberg’s merchant class—had composed And Dürer’s closefriend(andpossiblelover)WillibaldPirckheimercomposedanepitaphforthegrave: “WhateverwasmortalofAlbrechtDürer,”hewrote,“iscoveredbythistomb.”

Whatwasn’tmortalaboutDürer,though,wastheimageheprojected. Dürer didn’tjust haveanastoundingtalentforpaintingandprintmaking.Healsopossessedanextraordinary knack for self-promotion. Alongside his myriad saints and expertly rendered Madonnas, Dürermadeahabitofpainting,andpromoting,himself

In medieval Europe, such self-aggrandizement would have been unthinkable Medieval artists were traditionally anonymous. They were craftsmen, often working in collective guilds, whose output—the stonemasonry above a (church) door, the stained glass of a (church)window,theimagesofsaintson(church)wallfrescoes—wasdesignedtoreflectnot individual glory but rather the majesty of the earth’s true creator: God. Credit for one’s work was superfluous at best, suspiciously prideful at worst. One early “copyright” case from 1249, in which two competing Dominican friars claimed authorship of a popular theological tract, was settled by stripping both authors’ names and publishing the text anonymously.3 Self-portraitswereexceedinglyrare. Atmost,anartistmightdepicthimself asahumbleworshipperinthebackgroundofareligiousscene.ThenDürercamealong.

Dürer’sself-portraits—heproducedthirteen,amixtureofpaintings,drawings,andprints —are masterpieces of self-veneration, luxuriating in the beauty, and the glory, of his own finelyrenderedimage Ineach,Dürerappearsinelegant,evenaristocraticraiment(never mindthathewasbornamiddle-classgoldsmith’sson).Ineach,helingerswitheverycareful brushstrokeonthedelicateshapeofthosespiralingcurls,anaestheticsocentraltoDürer’s

public persona that contemporaries jokedthat he might be too busy to take commissions becauseoftheamountoftimehespentonhishair.4 EvenwhenDürer depictedhimselfin the background of religious scenes, he called attention to his presence, taking the thenunprecedentedstepofaddingtothesceneacartellino,alittlesign,tomakesuretheviewer knewexactlywhohewas

Dürer didn’t merely present himself as an aristocrat, however. Rather, he evoked somethingevenmoreambitious:agod.Drawingontheiconographyofreligiousartinwhich hehadbeensteeped,Dürercreatedself-portraitsthatdepictedhimselfas,essentially,Jesus Christ. For example, in Self-Portraitatthe Age ofTwenty-Eight(1500), Dürer reveals himselfnotinprofilebutfacingstraighton,aposetraditionallyreservedfor GodtheSon Hishair,goldeninotherportraits,ishererenderedadarkhazelnuttomatchathenpopular (ifforged) “eyewitness” account ofJesus’s owncoloring.5 Dürer’s index finger andthumb areraised,asJesus’swouldtraditionallyhavebeen.ButwhileJesus’sfingersoftenspelled outthelettersICXC,anacronymforJesusChrist,Dürer’sseemtobespellingouthisinitials, AD,ashisownsubstitutecartellino Thosesameinitialsappearalongsidethepainting’sdate totheleftofthehead,makingadistinctvisualpun:“1500AD”AnnoDomini,theyearofour Lord,isalsotheyearofAlbrechtDürer,comingintohisown.

Dürer’s“AD”wasn’t just hissignature,however. It also became hisprofessionalcalling card,anearlyattemptatwhatwemighttodaycallpersonalbranding.Dürerusedhisinitials to sign not only his paintings but also, more importantly, the prints he designed. He cautionedwould-be plagiarists against claimingcredit for his work: “Beware,youenvious thievesofthelaborsandingenuityofothers;keepyourthoughtlesshandsfromthisworkof art.”6 Unlike other printmakers at the time, Dürer eventually took the extra step of purchasinghisownprintingpress,givinghimcreativecontroloverthewholeoperationand allowinghimtosharehisworkfarmorewidelythaneverbefore.

Fromdesigntoimplementationtodissemination,Dürerwasincompletecontrolofhowhe presentedhimselfandhisworktohisaudience Andthataudience,furthermore,wasn’tjust Godoreventheclergyandworshippersofaspecificchurchpayingforhispieces Rather, Dürerknewhehadtheopportunitytocommandtheattentionofthewholeworld.When,in 1507, a patron pressured Dürer to speed up work on a time-consuming Nuremberg altarpiece,hisreplywasdismissivelycurt:“Whowouldwanttoseeit?”7

Albrecht Dürer hasbeenhailedasmanythings: one ofthe Renaissance’sfinest artists, the inventor of the selfie, the world’s first celebrity self-promoter But what he truly pioneered,inhislife andhiswork—andthe two were never easilyseparable—wasa new andambitiousvisionoftheself.Thatis,atleast,forselvesthatresembledAlbrechtDürer. Dürerrecognized,asfewearlierartistshaddone,thepotentialforconsciousself-creation, theplacewherecreativeself-expressionandpursuitofprofitmightmeet.Dürerdidn’tjust makeart;hetransformedhimselfintoaworkofart Heforgedapersonalitythatsustained and advertised his work, even as his work—constantly emblazoned with his trademark advertised the man. Dürer-the-artist, Dürer-the-portrait, and Dürer-the-advertiser all mutuallyreinforcedoneanother.

ButDürerrecognizedsomethingelse,too.Tocreateyourself,tofashionyourpersonality and your public image and your economic destiny—and Dürer never doubted that these were allinextricablylinked—wasto adopt a kindofgodliness,to displace a God-centered view of the universe with one that saw the individual, and particularly the creative individual,asdivine Whatevermagic,whateverenchantmentexistedintheworld—whether itcamefromGodornatureorsomenebulouslydefinedbeinginbetween—itwasuptothe cunninggeniustoharnessitandmakeitservehispurpose.

IT WOULD BE easy to conclude—and no doubt he would want us to—that Dürer was a singular geniusinthisregard,thatheandhisknackfor personalbrandinghadsprungup,

fully formed, in fifteenth-century Nuremberg to rock the Renaissance world. The truth, however, is a little bit more complicated. Dürer’s talent for self-invention—and his understanding of himself as a divine self-inventor—was inextricable from the changing societyinwhichhelived.

Dürerwas,afterall,aRenaissancemaninthemostliteralsenseoftheterm Hewasan artistworkinginathrivingmercantilecityatatimewhenthrivingmercantilecitiesallover WesternEuropewererethinking—atleastforcertainrelativelyfortunateclassesofpeople (that perpetualcaveat)—what societymight looklike andwhat newkindsofpeople might forgepathstosuccessandsplendor init. Throughoutthefifteenthandsixteenthcenturies all over the Europeancontinent, artists, philosophers, scholars, andpoets were wrestling withprofoundcultural,social,andeconomicchanges.

MostofthesechangeswillbesofamiliartograduatesofanyelementaryschoolEuropean historycurriculumastoborderonnarrativecliché:JohannesGutenberg’sinventionofthe printingpressinthe1450sandthesubsequentwidespreadproliferationofliteracy;therise of trade and craftsmanship and the re-centering of European cultural life from churchadjacent farmland to newly prosperous cities; the burgeoning development of an urban, middle,mercantileclassandthesocialmobilitythatwentwithit;therenewalofinterest(by people other than monks, at least) in Greco-Roman thought and with it the optimistic worldview traditionally called“humanistic,” as theology andphilosophy alike turnedaway fromtheprofoundsuspicionofworldlyattainmentthatmarkedsomuchofmedievalthought Hoarilyfamiliar(andinsomecasesoverlysimplistic)thoughthesenarrativesmaybe,they neverthelessarehelpfultocontextualizeDürerasamanofhistime.Moreimportant,they illustratewhyandhowourhistoryofself-makingstartshere,withasinglequestion,onethat notjustDürerbutawholehostofRenaissanceartists,philosophers,poets,andstatesmen werewrestlingwithtogether,aquestionthatwouldcometorevolutionize,andperhapseven define,themodernworld

The question? How do we understand, let alone explain, men like Dürer? Or, more broadly,howcanwemakesenseofmen(anditwasusuallymen)whoseemnottofitinto society’srigidexistinghierarchies?Howdowe,asasocietyaccountfortheself-mademan: themanwhosedestinycamenotfrombirthorblood,butratherfromsomemysterious,and perhapsevenmagical,qualitywithinhimself?

In an era of unprecedented social mobility, this question was particularly relevant All through Europe’s flourishing city-states, particularly on the Italian peninsula (here, the GermanDürerwassomethingofanoutlier),therecouldbefoundmenwho,ifnotquiteas flamboyant as Dürer, were nevertheless using their creative and intellectual talents to transcend the social strata into which they had been born. They were peasants turned craftsmen,orelsecraftsmenwhoseskillhadpropelledthemintoevenhighersocialspheres, perhapsevenintothecompanyofroyaltyorpopes LeonardodaVinci—theillegitimateson of a notary and a peasant—found himself patrons among the dukes of Milan and king of France Goldsmith’ssonDürerproducedcommissionsforHolyRomanemperorMaximilian I. Plenty of Renaissance Italy’s most prominent artists—da Vinci, of course, but also architectLeonBattistaAlbertiandpainterFilippoLippi—werebastards:menwithnolegal parentandthusnoclearlydefinedsocialplace.

Andit wasn’t just artists either. Clever would-be scholars like Poggio Bracciolini—born virtuallypennilessasanapothecary’sson—couldshowupinFlorencewithfivesilversoldiin theirpocketsandbe“discovered”bywealthypatronsinneedoflibrariansorcourtscholars, workingtheir wayupthroughsecretarialranks to become wealthyandwell-connectedin theirownright.BythetimeofBracciolini’sdeathin1459,hehadbecomeoneofFlorence’s wealthiestmen,havingmarried,attheageoffifty-six,aneighteen-year-oldheiress.

Thisnewclassofmenwasnotmerelyself-madeinthecolloquialsense—theonewemost commonlyusewhenwetalkabouta“self-madebillionaire”or a“self-madeentrepreneur” who has, despite the absence of family wealth or privilege, succeeded in becoming an economic success—although, inmany cases, they did indeed do just that They were also self-makers:peoplewhosepersonalcreativequalitiesseemedtogivethemlicensetomold

not just the art (or poetry, or philosophy) they produced but also their public personality and, through it, their destiny. Self-making was always a double act, simultaneously the constructionofaselftomovethroughtheworldandashapingofthatself’sfortune.

THIS RISE OF these self-made men wasn’t just a social question, however It was also a theological one. Self-creation—as Dürer’s cheeky rendering of himself as Jesus rightly suggested—was a challenge to a deeply rooted religious view of the cosmos, steeped in centuriesofmedievalChristianthought Afterall,wasnottheactofcreation—ofthenatural world, of human beings, of their lives and destinies—the foundational prerogative of God himself?

Certainly, to the medieval Christian mind, God was not just the creator of the natural worldbutalsothecreator andsustainer ofthesocialworld. Indeed,thedistinctionwould havebeenunthinkable Thenaturalworldandtheworldofhumanlifewereconsideredto be one cohesive whole, in which each being had its God-given place and God-given role

Animal life, peasant life, the life of kings—all these echoed and reflected one another to God’sglory,sustainedbythe God-orderednaturallaw that boundallthingstogether. The thirteenth-century philosopher-saint Thomas Aquinas, for example, characterized human governmentandartisticproductionalikeasmerelyaninstantiationofthenaturalprinciple that“thepowerofasecondarymoverflowsfromthepowerofthefirstmover.”The“planof governmentisderivedbysecondarygovernorsfromthegovernorinchief,”while“theplan of what is to be done in a state flows from the king’s command to his inferior administrators.”Hewrotethattheactofcraftsmanship“flowsfromthechiefcraftsmanto theunder-craftsmen,whoworkwiththeir hands,”for “alllaws,insofar astheypartakeof rightreason,arederivedfromtheeternallaw.”8

What that meant, practically speaking, is that God had also determined the shape of humanlife,includingrank,blood,andstation Medievallifeandlaw,byandlarge,treated human beings not as isolated individuals but as members of the family, the class, the community,andthelandintowhichtheyhadbeenborn.Self-making,ofanykind,wouldhave beenanonsensicalpropositiontothemedievalmind.Humanbeingshadalreadybeenmade, fearfullyandwonderfully,bytheir creator,aspartofaholisticandcomplexunity,working towardadivinepurposethattranscendedanythinganindividualhumancouldunderstand A mancouldnomorecreatehimselfthanhecouldcreateafrog,aflower,oratree

HOW, THEN, TO account for the self-made man, a figure who seemed to not just shatter societalexpectationsbutoverthrowthelawofnatureitself?Overthefifteenthandsixteenth centuries,Renaissancediscourseabouttheself-mademan—theartist,thescholar,andthe lowbornupstartalike—begantocoalescearoundananswer,onethatpreservedthevision ofa God-ordereduniverse andyet made roomwithinit for a special kindofperson. This individualcouldatonceleapfrogthesocialorderandyetremainsafelywithintheconsoling paradigm of a society God had determined Different writers and thinkers used slightly differentterminologytodescribesuchaperson—the“truenoble,”the“makerofvirtue” buttheoneinmostcommonusetoday,andthemostaptforourpurposes,isthegenius.

Genius, as it was used in the Renaissance by figures from Petrarch to Boccaccio to Erasmus,alreadydenotedtwovitalqualitiesoftheself-mademanthetermsoughttodefine and explain. First, the word itself suggested that such a person’s power had a divine or supernatural origin The Latin word geniusoriginally referred to a guardian that might attend or inhabit a human being A person possessing genius wasn’t just intelligent or talented,inotherwords Rather,theyweretouchedbysomethingfargreater

Second, genius suggested a connection to the faculty of creative thought, that very ingenium,or ingenuity,thatDürer wassoanxioustodefend. Whatever madethegeniusa genius—whatever power animated a Dürer or a da Vinci or a Poggio Bracciolini—it had somethingtodowith,specifically,thehumanpowertoreflect,orimitate,thatdivinefaculty ofcreation9

HowcouldRenaissancesocietyincorporatesuchanovel,forcefulfigure?Theanswerwas aspecificrhetoricalmovethatgavethegeniusadeterminedplaceinsociety,notasaselfmadeselfexactly,butasaspecialscionofGod,someonewhocouldclaimahigherandpurer lineagethanthatprovidedbytheirearthlyfather.Thosewhotranscendedthesocialorder hadtobeunderstoodasacoherentpartof,ratherthanatransgressionagainst,aworldin whichGodhadorderedallpeopleandallthings

The apocryphal stories of Renaissance genius—whether told by self-declared geniuses themselvesorbytheirhagiographicbiographers—tendtofollowasimilarpattern.Geniuses were coded, metaphorically and rhetorically, as the contemporary equivalent of GrecoRoman demigods: mythological figures like Hercules or Achilles conceived by a liaison betweenagodandamortalwoman.Theybelonged,inotherwords,toahigheraristocracy.

Thegeniusmighthaveahumblefather—or,indeed,inthecasesofsomanyRenaissance geniusbastards,nolegalfatheratall—buthis“real”father,morallyandspirituallyspeaking, hadtobeunderstoodasdivine.Thegenius’ssocialmobility,therefore,likethatofthefairytale peasant who discovers he is secretly a prince stolen away from the castle of birth, rested upon the assumption that he had already been marked out by God’s transcendent authority.Hissuccesswasnotbecausehehadtranscendedortransgressedagainstsocietal order but simply because he was acting according to his superior nature and being recognizedasaresult

The genius as demigod became a common rhetorical trope in Renaissance life The Mantuanpainter Andrea Mantegna, most famous for his depictions of life at the court of Gonzaga,oftenreferredtohimselfinLatinas“Aeneas”—anotherfamousdemigodandhero oftheAeneid.InonememorialportraitofDürer,theDanishartistMelchiorLorckaddeda captionlaudingtheartistas“onewhomMinerva[Romangoddessofwisdom]broughtforth fromherownbosom”10 And,inarareChristianizedexampleofthetrope,theNuremberg sculptorAdamKraftwasapparentlysofondofpromotinghimselfasakindofsecondAdam thebiblicalone,thatis—thatinordertopleasehim,hissteadfastwifestartedreferringto herselfasEve 11 Thoughthe idea of a “secondAdam” hadtraditionally beenone usedto describe Jesus Christ, Kraft—like Dürer—hinted that the Renaissance genius might well deservetoappropriatesuchatitle.

Narratives about the precocious childhoods of perceived geniuses were also often preposterouslyembellished,heighteningthe sense thatthese figures’overwhelmingtalent wassupernaturalinnature. JustastheinfantHerculesfamouslyslewsnakeswhilestillin hiscradle,thepainter LeonardodaVinciwassaidbybiographer (andnotedexaggerator) GiorgioVasaritohavesooverwhelmedhismentor,AndreadelVerrocchio,withtheforceof histalentthattheoldermangaveuppaintingentirely (Vasarialsotellsasimilarstoryabout Michelangelo and his mentor.) Lorenzo Ghiberti’s fifteenth-century biography of the thirteenth-centurylowbornpainter GiottodiBondonefollowsasimilar narrative: anolder painter,Cimabue,issoimpressedbytheyoungfarmboy’sdrawingofasheeponaslabof stone that he whisks the boy away at once to serve as his apprentice. Central to each narrative is the notionthat the genius’s power is totally innate andentirely unteachable Indeed,humanmentorswhotrytoteachtheseboysskillsareusuallyshownupbytheforce oftheirpupil’snaivepower Geniusmustcomefromsomethingoutside,andbeyond,human endeavor.

Now, writers of these accounts did not literally believe inliaisons betweenthe GrecoRomangodsandhumanbeings,orindeedintheexistenceofGreco-Romangodsatall.We are still, after all, discussing an era strictly defined by a Christian worldview. But the ChristianityoftheRenaissancewasaratherdifferent,andperhapsmorefluid,onethanthe

medieval worldview that preceded it. The more explicitly theological language of God as creatorwasoftenusedsidebysidewithmetaphoricallanguagedepictingeitherNatureor Fortune—mysteriousandimpersonalforces—asagoddess,onewhoimpartsherwilldirectly byimbuinggeniuseswithsomeofherpower.

Renaissance geniuses were a little bit like Renaissance bastards, liminal figures of mysterious parentage who could not be easily slotted into an existing social system In England, one of Shakespeare’s most magnetic villains, King Lear’s illegitimate upstart Edmund,made the parallelsexplicit. He excoriatesthe “plague ofcustom”that condemns himtoinferioritytohislegitimatebrother,declaimingthat“thou,Nature,artmygoddess.” He concludes: “Stand up for bastards”12 The language (metaphorical or otherwise) of divine origin solved some of the problem of the genius By understanding geniuses as analogous to aristocrats, Renaissance thinkers were able to incorporate these seemingly anomalousfiguresintoaworldstillgovernedbydivinelaw.

A MAJOR FEATUREofRenaissancedebatesanddialogues—onethatreflectedjusthowfraught the question was at the time—was the relationship of what we might call traditional aristocracyto that new aristocracyofgenius. Asthe Renaissance scholar Albert RabilJr. points out in his extremely worthwhile book on the theme, the question of true nobility becameamainstayofhumanistdialogues;throughoutthefifteenthcentury,atleasteleven treatises were published on that point, each one featuring heated debate between proponents of the older model of nobility and of this new one. In Buonaccorso da Montemagno’s 1429 “Dialogue on True Nobility,” for example, the lowborn advocate for geniusarguesthat“theproperseatofnobilityisinthemind,whichnature,thatempressof allthings,bestowsonbirthonallmortalsinequalmeasure,notonthebasisofthelegacy derivedfromtheirancestors,butonthebasisofthathighrankthatispeculiartodivinity.”13 Nobility,heinsists,“doesnotcomefromfamilybutfrominnatevirtue.”Hisown“desirefor knowledgewasinfusedinme…bynature,sothatnothingseemedmoreworthyofmytalent thanpursuit ofthe knowledge ofthe good”14 Montemagno leavesthe questionopen—the dialogue ends before it is formally decided—but it’s the flashy upstart who gets the last word.Acontemporarypoemonthetopic,byCarloMarsuppini,celebratesthose“well-born noblethoughtheyeatoffearthenware/andbelongtoanunknownfamily.”15

We find similar imagery in another treatise by the lowborn Greek bishop Leonard of Chios,himselfaself-mademan For thecharactersinLeonard’sdialogue,theidealmanis born“withwisdomashismotherandfreewillashisfather,”possessedofthenobilitythat “arisesfromthe rootofvirtue asthoughitsstrengthhadsprungfrominnate principlesof nature.”16 Commenting on the Greek philosopher Aristotle’s argument that desirable qualities for happiness include “good birth,” Leonard’s interlocutor insists that Aristotle could not possibly have been referring to aristocratic lineage but “rather moral birth, becausetheformerinvolvescorruptionofblood,thelatterthemostgracefulcharacter.”17

Notable ineachofthese textsisthe delicate balance the authorsmust strike between affirmingthestatusquo—aworldlargelydefinedbyaristocraciesofbirth—andaccounting forthisnewclassofpeoplefindingtheirplaceinit.Thelanguageof“truenobility”andthe imageryofthedemigodserveausefuldoublepurpose Geniuseshavethecapacitytomake themselvespreciselybecause theyhave beenchosenbyGodto do so Theyare a special few,afavoredfew,andtheirself-authorshipislimitedandproscribedbydivinewill.

Evenmoreambitiousandexplicitaboutthesuperiorityofthearistocracyofgeniuswas the1440dialogue“OnTrueNobility,”writtenbyPoggioBracciolini,theFlorentinearriviste we encounteredearlier. Bracciolini uses “virtue” to describe the quality we’ve elsewhere discussed as genius, but it is clear from his context that virtue does not simply mean a capacity for right moral action Rather, Bracciolini treats it as something innate and

embedded in the personality of the “true noble,” regardless of the circumstances of his birth.“Virtue,”Braccioliniwrites,“mustbegraspedbyakindofdivinepowerandfavorand bythe hiddenmovement offate,andcannot be gainedbyparentalinstruction.”18 Human parents, in other words, are of little use when it comes to this divine inheritance As Bracciolini insists, “Childrendo not inherit either vices or virtues fromtheir parents; the authorandmakerofvirtueandnobilityisthepersonhimself.”19

Inthis,Bracciolinigoesevenfurtherthanhiscontemporaries,pointingtoaquestionthat will continue to underpin the entire history of self-creation Is the self-made man merely lucky,blessed,chosenbyeitherapersonalGodorimpersonalnaturetomakehisfortunate wayinanotherwiseorderlyworld?Orishe,asBracciolini’slanguagesuggests,theauthor of his selfhood, someone whose free choice, will, desire, and effort all work together to create his identity and destiny? Is the self-made man like a Hercules or an Aeneas, a demigodchildunder the paternalauthorityofastronger deity? Or ishe like the Christof Dürer’s infamous self-portrait, fully, splendidly, anddangerously divine of his ownaccord? Does he have a preternatural, even magical, ability to achieve the economic and artistic goalsGodhaspreordainedfor him,or doeshismagiclie inhisabilityto choose hisgoals himself?

BY AND LARGE, Renaissance authors dealing with the twin questions of self-creation and geniustendedtowardtheformer,moreconservativeapproach.Thegeniusisaspecialkind ofperson,tobesure,butheisararecase:anaccounted-forexceptiontothegeneralrules thatgovernthesocialorder.

ButoneRenaissancehumanist,GiovanniPicodellaMirandola,wentmuchfurther,taking anambitiousapproachtothe projectofself-creationthatwouldprefigure muchlater,and more explicitly ambitious, models of self-making. A thoroughly unorthodox figure, Pico blendedhisChristianhumanismwithJewishkabbalah,Arab philosophy,Classicallearning, andahealthydab ofthe occult. Picodidn’tjustargue thathumanbeingswere capable of self-invention, or even that self-invention was a morally desirable thing. Rather, in his “Oration on the Dignity of Man,” composed as an introduction to a longer philosophical lecture,Picoarguesthatself-creation—theactive,willedimitationofGod—ispreciselythe qualitythatmakesushuman Theabilitytodetermine whowe are andtodecide our own placeinthedivinecosmosisGod’sgifttous.

PicomakeshiscasebyretellingthecreationstoryofthebookofGenesis.AsintheBible, Godcreatesvariouselementsoftheworldinorder.Butinthisversion,theactofcreationis so taxing that God, in essence, uses up his mental “seeds.” So, he decides to create a singular creature without any kind of seeds, and thus without any kind of inheritance or obligation He makes man In Pico’s telling, God, in creating Adam, is essentially making anothergodtotakeover “Adam,”Godannounces,“youhavebeengivennofixedplace,no form of your own, so that you may have and possess, according to your will and your inclination,whateverplace,whateverform,andwhateverfunctionsyouchoose.Divinelaw assignstoallothercreaturesafixednature.Butyou,constrainedbynolaws,byyourown freewill,inwhosehandsIhaveplacedyou,willdetermineyourownnature”20

Pico’s“Oration”wasneverdelivered Thelongerprojectitwasplannedtoprecede—afull ninehundredtheologicalthesesheintendedtopresenttohisphilosophicalcontemporaries —provedcontroversial.Seventhesesweredeemedoutrightheretical,sixmoreofconcern, andPicopromptlyfledRome for France. Butthe sentimentsthe “Oration”containswould haverepresentedamongthemoststrikingandpotentiallytransgressivevisionsoftheselfmade man in the Renaissance world Pico wasn’t just allowing for true nobility, or moral birth, or other mechanisms withinwhichto fit humanwill into a God-orderedsystem He wassayingthathumanbeingsshoulddecidethesystemforthemselves.Andwhilethatgift, inhistelling,doesindeedcomefromGod,PicosuggeststhatGod—whohas,afterall,used

upallhisenergycreatingtheworld—isnomorepowerfulthanwemightourselvesbecome. InPico,nolessthaninDürer,thepowertofashionourselvesholdswithinitthepromiseof dethroningGodhimself.

PicoandDürerbothanticipateoneofthemajortensionsthatwillrecurthroughoutthis historyofself-creation: the relationshipbetweenhumanself-creatorsandGod,or at least our ideas about God Already, this first flowering of ideas about modern self-creation coincideswithaperiodinhistorymarkedbyagrowingsuspicionoforganizedinstitutional religionandtheideaofanauthoritativecreator-God.Inthecenturiestocome,theideaof the self-creator as a kind of successful Lucifer—overthrowing God’s creative power and seizingthethronehimself—willcometotheforefrontevenasbeliefinsuchaGod,andthe political system predicated on that belief, recedes. Pico and Dürer are extreme among Renaissance theorists of genius, but their vision of the self-maker as a new god for an increasinglygodlessagewilloutlivethem

BUT A SECOND setofunresolvedquestionslurksatthemarginsofthisnarrative:questions about authenticity, truth, and performance. It’s all very well and good to say that some people are geniuses, chosen by God to have special fates that transcend their economic station. But how exactly do we tell who these geniuses really are andwhether we might ourselvesbeone?Canitbeascertainedfromhowtheycarrythemselves,howtheypresent themselves,howtheybehaveinpublic?And,ifso,cangeniusbeimitatedbythosewhowish toimprovetheirstationinlife?Andifgeniuscanbesosuccessfullyimitatedbythosewho are willingto fake it until they make it, thenwhat is the difference betweenthe divinely chosenself-makerandthearrivistewhodecidestodispensewithGodandnaturealtogether andsimplychoosehimself?

FromtheRenaissancetotheRegencyera,fromthestagesoffindesiècletheaterstothe trading floors of the American Gilded Age, whenever we find a cultural obsession with “divine” self-makers, we are likely to also see anequally fervent obsessionwithwhat we might today call the cult of self-help: manifestos andguides that purport to helpordinary peopleconvincetheirpeersthattheybelongtotheranksofthefavoredfew.

But defining genius was only one piece of the puzzle. At the same time that many Renaissance writers were negotiating the genius’s precise social status, they were also workingoutadifferentquestion:howtomakepeoplethinkthatyouwereagenius.Among the mostnotable handbookstothiskindofartisBaldassare Castiglione’s1528 bookThe Courtier:aguideforthosewhowishedtoserveinaristocraticcourtslikeCastiglione’sown duchy of Urbino The book—an extended series of dialogues between characters who double as stand-ins for a variety of Renaissance views—features a number of debates, including several on the nature of true nobility and whether the virtuous and talented lowborn are as desirable as courtiers as the biological aristocrats. Yet one of the most significantpassagesinthebookdoesn’tdealwithbirthatall.Rather,itdealswithanother mysterious—and difficult to translate—quality, one Castiglione refers to as “sprezzatura,” oftentranslatedintoEnglishas“lightness”or“nonchalance”

Sprezzatura, we learn, is one of the most important qualities a courtier can have. As Count Ludovico, one of Castiglione’s interlocutors, puts it, sprezzatura “conceal[s] design andshow[s]thatwhatisdoneandsaidisdonewithouteffortandalmostwithoutthought.”21 ThefigurativetalentsofaGiottooraninfantdaVincimaybeobviousfromthetimethey’re outofthecradle Fortherestofus,Castiglionesuggests,itisnecessarytosimplygivethe impressionthatwhateverwedoisaseasyforusasitwouldhavebeenforoneoflife’smore favoredfew.LookinglikeyoutriedtoohardwasasunfashionableatCastiglione’scourtasit wouldbe today at a modernFashionWeek party, a surefire signthat youweren’t one of God’snoblebastards.

Ludovicogoesontobeevenmoreexplicitabouttheconsciousimitationofgenius. “We mayaffirmthattobetrueartwhichdoesnotappeartobeart;nortoanythingmustwegive greater care than to conceal art,” he insists, praising the example of “very excellent orators”who“strovetomakeeveryonebelievethattheyhadnoknowledgeofletters,and… pretendedthat their orations were composedvery simply, andas ifspringingrather from nature and truth rather than from study and art.”22 Lying at least the delicately artful, little-white-liekind—isintegraltoself-making. Inorder tobecomewhowewanttobe,we firsthavetoconvinceotherpeoplethatwearewhatwearenot.

TheCourtier, therefore, represents the final strand woven into the tapestry of selfmaking:thedevelopmentofasenseoftheselfasanartisticprojecttobepresentedtothe outside world, as well as shapedfromwithin Fromanoutside perspective, at least, how couldanyonetelltheauthenticgenius(theoneGodornaturechose)fromtheartificialone (theonewhowasjustthatgoodatpublicself-presentation)?Evenatthisearlyjuncture,the figure of the successful, talentedself-made manwas doggedby its perpetual shadow: the cannyself-presenterwhomanagedtoconvincepeoplehewaswhohewantedtobe.

TheRenaissancemythosofgodlikenobility—thatnature,orGod,orfortunehadadopted certainluckyfiguresastheirown—wenthandinhandwiththemorecynicalpromisethatit waspossibletojustpretendthatyouwereoneofthem YoumightnotbedaVinci—ofwhom Vasaribreathlesslywrotethat“whateverheturnedhismindto,hemadehimselfmasterof withease”—but,bymakingthingsappeareasy,youcouldgiveoffthatimpression,atleast forawhile.23

TheCourtiercallsuponitswould-be geniusesto payactive attentionto the art ofselfcultivation CountLudovicoexhortshislisteners“toobservedifferentmen [and]goabout selecting this thing from one and that thing from another. And as the bee in the green meadowsiseverwonttorobtheflowersamongthegrass,soourCourtiermuststealthis grace fromallwho seemto possessit”24 Sure,maybe genius itselfcannot be learnedor taught,butitsoutcome—earthlysuccess—could,Castiglionesuggests,bereplicatedthrough carefulstudy,meticulousobservation,andthatmostunfashionableofqualities:hardwork

CASTIGLIONE’S HANDBOOK WASwildlypopular,andnotjustamongactualcourtiers.By1600, the book had been reissued a staggering fifty-nine times in Italy and had also been translatedintoGerman,Latin,Spanish,French,English,andPolish.25 Butitwasnottheonly Renaissance handbook to suggest that dissembling—cultivating how others see you, regardless of the actual truth—might be necessary for success In 1513, Florentine statesmanNiccolòMachiavellihadpublishedThePrince,aguidebookforrulers,inspiredby hisownexperienceofupheavalanddivisionamongtheMedicifamilywhohadoncebeenhis patrons.

If TheCourtieradvocated the odd white lie—a concealment of effort here, a carefully calibratedgesturethere—thenThePrinceespousedacodeofstraight-upmendacity “One canmakethisgeneralizationaboutmen,”Machiavelliscoffed “Theyareungrateful,fickle, liars,anddeceivers,theyshundangerandaregreedyforprofit;whileyoutreatthemwell, theyareyours…butwhenyouareindangertheyturnagainstyou.”Aprincewhowantedto remain in power had to be constantly presenting the right face to the world, inspiring alternativelyawe,gratitude,andfear. Hismorality(or lackthereof) wasirrelevant. What mattered was the part he was willing to play: sometimes a prince should “be a fox to discoverthesnares,”atothertimes“aliontoterrifythewolves”26

Wearealongway,here,fromthevisionofacohesiveanddivinelyarrangednaturalorder as envisioned by Thomas Aquinas and other doctors of the medieval church. Nature, for Machiavelli,isbrutalandmeaningless.Theprince’sroleistochooseatwillfromamongthe varyingbeastsoftheforesttofindatemporarymodelforhismaneuvers.Theidealquality

ofaprince,forMachiavelli,isnotgeniusassuchbutratherwhathecallsvirtù—awordhe uses not to meanvirtue inthe moral sense but rather manly effectiveness (the termalso suggests“virility”).Aprinceshouldbendfortunetohiswill.

OtherRenaissanceauthorsusedfeminineimagerytoconceiveofnatureorfortuneasa mother,the protective parentofthe chosengenius Butfor Machiavelli,itwasthe role of themanofvirtùtotakefortunebyforce,anacthedescribesusingtheviolentmetaphorical language of rape “Fortune is a woman,” he insisted, “andif she is to be submissive it is necessarytobeatandcoerceher.Experienceshowsthatsheismoreoftensubduedbymen whodothisthanbythosewhoactcoldly.…Beingawoman,shefavorsyoungmen,because they are less circumspect andmore ardent, andbecause they commandher withgreater audacity”27

Machiavelli’sguidance,evenmorethanCastiglione’s,perhapsevenmorethanPico’s,isa death knell for the worldview of divine order that our Renaissance thinkers sought to sustain. In the centuries to come, we will see a radical reimagining of the relationship betweendivine law,naturallaw,andthe socialorder. Nolonger wouldthe self-made man havetobefittedintoanexistingsystem.Instead,thesystemwouldbefittedtohim.

“SHAKINGOFFTHEYOKEOFAUTHORITY”

IT WAS THE LATE SIXTEENTH CENTURY AND MICHEL EYQUEM DE Montaigne hadone burning question:Whyonearthdidhehavetowearclothes?TheFrenchauthorwasnotparticularly fond of covering himself up. Throughout the more than one hundred essays (a genre he basicallyinvented) Montaigne wrote inhislifetime,he alludedfrequentlyto hisdesire for bothmetaphoricalandliteralnakedness

InthebriefintroductiontohisEssais,writtenin1580,Montaignepromiseshisreaders totalhonestyanddisclosureofwhohereallyis. Rather thantryingtoimpressthem“with borrowedbeauties” or pretty phrases,he promises that “hadI livedamongthose nations which(theysay)stillliveunderthesweetlibertyofnature’sprimitivelaws,IassureyouI would easily have painted myself quite fully and quite naked”1 Nakedness, for the rhetoricallyflamboyantMontaigne,suggestshonesty,trustworthiness,and,perhaps,ahint oftransgression.

Amonghisgleefullyfreewheelingessays,ontopicsfromthe nature ofknowledge tothe structure of politics, Montaigne frequently turns the subject to both nudity and bodily functions. He remarks wryly, for instance, onthe emperor Maximilian, who “wouldnever permitanyofhisbedchamber”toseehimonthetoiletandwould“stealasidetomakewater asreligiouslyasavirgin.”2 Montaignegoesontoinformthereaderthat“Imyself…[am]so naturallymodestthiswaythatunlessattheimportunityofnecessityofpleasure,Iscarcely evercommunicatetothesightofanyeitherthosepartsoractionsthatcustomordersusto conceal”3 In another essay, Montaigne meditates upon the “indocile liberty” of the male member

But it was clothing—and the seemingly arbitrary way people wore it—that obsessed Montaignemost.Inoneessay,straightforwardlytitled“OntheCustomofWearingClothes,” heinviteshisreadertowonderalongwithhim“whetherthefashionofgoingnakedinthese nationslatelydiscovered”—bywhichhemeanswhathiscontemporarieswouldhavecalled theconquestoftheNewWorld—“isimposeduponthembythehottemperatureoftheair orwhetheritbetheoriginalfashionofmankind?”4 Afterall,hemarvels,eveninhisnative Europe, fashions for clothing differ. And other animals don’t wear any clothing at all, regardlessofthetemperature.

Hisconclusion?Thatwehavedevelopedakindoflearnedhelplessnessasaresultofsocalledcivilization:“Asthosewhobyartificiallightputoutthatofday,”hewrites,“soweby borrowed fashion have destroyed” our ability to walk about uncovered Ultimately, Montaignedecides,itisnotdivineorder,thelawsofnature,or thedictatesofreasonbut “customonly”thatdetermineswhatpeoplewear—oriftheywearanythingatall.5

The sheer arbitrariness of clothing is a theme Montaigne returns to again in another essay,onedescribingsumptuarylaws: aseriesoflegalcodes,popular acrossRenaissance Europe,thatsoughttolegislatewhatpeopleworeaccordingtotheirsocialposition These lawswerelargelythoughnotexclusivelydesignedtolimittheopportunitiesofaburgeoning middle class to spend their newfound wealth on aristocratic fashions. In England, for example, only knights and lords could wear ermine or sable, furs traditionally associated with aristocratic heraldic symbols. In sixteenth-century Milan, artisans and other middleclass workers were forbidden to wear silk and could wear gold only in the form of a necklaceworthundertwenty-fivescudi.6 InMontaigne’sownFrance,hereports,“nonebut

princes shall eat turbot, shall wear velvet or gold lace.”7 Theoretically, the role of the sumptuarylawswastopreserveakindofvisualordertothesocialcosmos,thesamevision of well-ordered universe we discussed in Chapter 1. In that vision, the aristocrats, the merchants,andthepeasantswerealleasilydistinguishablefromoneanother Ataglance, you could tell who belonged where in the fabric of the universe How you presented yourself,atleastintheory,showedafundamentaltruthaboutwhoyoureallywere,atruth rootedinyoursocialstationandtheclassintowhichyouhadbeenborn.

Montaignefoundallofthatridiculous.“’Tisstrange,”heremarks,“howsuddenlyandwith howmucheasecustomintheseindifferentthingsestablishesitselfandbecomesauthority.” Montaigne’s issue wasn’t just with the restriction of certain clothing to certain classes Rather,itwaswithaconceptthatwillbecomecentraltoour understandingoftheroleof self-makersinanincreasinglydisenchantedworld:custom

ForMontaigne,customisn’tjustharmlesstradition.Rather,it’swhatwe’releftwithwhen we stop seeing the social world as inextricably connected to the natural one, or to the supernatural one. Custom suggests that the reason we do things—cut our hair, wear clothing,performcertainactions—isnotbecauseweoughtto,orbecausesodoingispartof whatwewerecreatedtodobyGod Rather,wedothingssimplybecausewealwayshave, with no particularly good reason behind our actions Our social lives, and the rules that governthem,aresimplyarbitrary.

Throughouthisessays,Montaigneasksthesamequestionoverandover:“Wherearewe todistinguishthenaturallawsfromthosewhichhavebeenimposedbyman’sinvention?”8 Overandover,hecomestothesameconclusion Mostseemingtruthsorlawsabouttheway things are, especially whenthey come to our social lives andidentities, are not innate or God-given but mere accidents of history. Which means, Montaigne tantalizingly suggests, thatwehavethepowertochangethem.

THISWIDER PHENOMENON,whatIwishtotermthedisenchantmentofcustom,wouldcometo define the entire social, philosophical, scientific, and intellectual movement—often consideredunder the umbrella termofthe Enlightenment—thatwouldshape the nextfew centuriesofEuropeanthought FromMontaigne’stimeuntiltheFrenchRevolutionin1789, WesternEurope—particularly,thoughnotexclusively,FranceandGermany—wouldwrestle with an intellectual shift that would definitively dispense with a God-ordered view of the cosmos.

TheEnlightenment,broadandvariedthoughitwas,wouldultimatelyheraldavarietyof major revolutions,bothideologicalandquite literal,acrossthe continent. It displacedthe moralandpoliticalauthorityoftheCatholicChurch(alreadyunderthreatacrossEuropeby the success of the Protestant Reformation), as well as religious institutional power more broadly Itwouldusherinthedevelopmentofnewpoliticalconceptslikenaturalrights,and with them a growing demand for political systems that could sustain them. And—most relevant to our story—it would mark a transformation in the cultural understanding of humanbeingsandhumandestiny.Humanbeings,thisnewphilosophyheld,hadnotjustthe powerbuttherighttoshapetheirownlives.

ArecurrentthemeoftheEnlightenmentnarrativeisthis:Ahumanbeing(or,atleast,one of certain kinds, classes, and gender) must untether himself from all those elements of custom—birthandblood,tobe sure,butalsoreligioussuperstitionandunexaminedsocial mores—that alienate him from his true, natural state. It is only in that state—a kind of metaphoricalnakedness,ifyouwill—thatmancouldbetrulyhimselfandtrulyfree.

Historians sometimes refer to the Enlightenment as an age of reason, defined by philosophers’ obsessionwiththe triumphof rationality over passions or feelings (oftenin contrast with their successors, the Romantics) Such an assessment—for a variety of reasons too long to get into here—is rather reductionist But it’s fair to say that the

Enlightenment was anera where people understoodthemselves as triumphingover if not exactlypassion,thenatleastsuperstition.Itwasanagewherethementalcapacitiesofthe individualwereunderstoodasmorepowerful,morecorrect,and,well,justplainbetterthan theunexaminedandprejudicialassumptionsofthesocialcollective,beitking,community,or church

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in his 1784 essay on what, exactly, enlightenmentwassupposedtobe,famouslydefineditas“man’semergencefromhisselfimposedimmaturity.”9 The unenlightened,bycontrast,were depicted—like toddlersofthe time would have been—as grasping at “leading strings” to guide them in their parents’ direction DenisDiderotandJeanLeRondd’Alembert’sEncyclopedia,likewise,celebrated thebirthofwhattheysawasanewera“fulloflight,”inwhichcannyphilosopherswouldat last“shakeofftheyokeofauthority.”10 Tradition,mores,custom,prejudice—allthesewere dirty words for Enlightenment thinkers. Another philosopher, the Marquis de Condorcet, claimed that the goal of his (rather ambitious) Sketch for a HistoricalPicture ofthe ProgressoftheHumanMindwas“toremovethetruenatureofallourprejudices”11 The EnglishphilosopherJohnLockemarveledthat“thereisscarcethatPrincipleofMoralityto benamed,orRuleofVertuetobethoughton…whichisnot,somewhereorother,slighted and condemned by the general fashion of whole Societies of Men, governed by practical OpinionsandRulesoflivingquiteoppositetoothers”12

The enlightened man, unlike his forebears, recognized that the social imaginary into whichhehadbeenbornwasmerelyamatterofchance.Hecouldjustaseasilyhavebeen bornintoadifferentsociety,evenadifferentcountry,withcompletelydifferentcustomsand rules.

At itsmost extreme,the Enlightenment rejectionofcustommeant rejectingthe idea of nationality altogether as something embarrassingly parochial Eighteenth-century French philosopherDiderot,forexample,wrotealettertohisScottishcontemporaryDavidHume, approvingly assuring him that “you belong to all nations, and you will never ask an unfortunatepersonforanextractfromhisbaptismalregister”—information,inotherwords, abouthisplaceofbirth.13 “Ipridemyself,”Diderotwenton,“onbeing,likeyou,acitizenof thatgreatcity:theworld.”14 Theenlightenedmanhadtobe,inotherwords,cosmopolitan: unrootedinany particular way of life. When, for example, the German-bornFrenchpoet Georges-LouisdeBärcelebrated“MyCountry”inalaudatorypoemaddressedtothesame, the object of his affection was not a single nation but rather the whole world, broadly conceived “Icomewithoutachoice,intothisworldperverse,”hewrote “ThereIam,thusI am,citizenoftheuniverse/I’macosmopolitan,like[thephilosopher]Diogenes/Iembrace inmyloveallofhumanity.”15

Once we had beenchildren, the argument went, content to live under the authority of custom, under the paternalistic power of a king, a church, a country, a God. Moral and intellectual adulthood, however, demands that we sever our leading strings altogether, to facetheworldnaked,untethered,alone

YOU MIGHT BE wonderingwhatI’mdoingtalkingaboutnakednessandauthenticityinabook that purports to be, at least inpart, about fashionable dandies and artificial self-makers. What is authentic, after all, about Albrecht Dürer’s meticulously rendered, product-heavy curlsortheluxuriousfurshewearsinhisportraits?Whatisauthenticaboutthestiffsuitsof BeauBrummell,thegreencarnationsofOscarWilde,orthepreternaturallyfulllipsofKim Kardashian?

ButitispreciselythisEnlightenmentobsessionwithclearingawaycustominpursuitof our true, authentic, and naked selves that makes later concepts of self-creationpossible Theideathatwecan,andindeedshould,shapeourlivesaccordingtothedestinieswewant

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation (“the Foundation” or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the United States and you are located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project Gutenberg™ mission of promoting free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg™ works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the Project Gutenberg™ name associated with the work. You can easily comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg™ License when you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States, check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing, distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any other Project Gutenberg™ work. The Foundation makes no representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any country other than the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg™ License must appear prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg™ work (any work on which the phrase “Project Gutenberg” appears, or with which the phrase “Project

Gutenberg” is associated) is accessed, displayed, performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase “Project Gutenberg” associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg™ trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg™ electronic work is posted with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms will be linked to the Project Gutenberg™ License for all works posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg™ License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg™.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project Gutenberg™ License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary, compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg™ work in a format other than “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other format used in the official version posted on the official Project Gutenberg™ website (www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original “Plain Vanilla ASCII” or other form. Any alternate format must include the full Project Gutenberg™ License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying, performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg™ works unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing access to or distributing Project Gutenberg™ electronic works provided that:

• You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from the use of Project Gutenberg™ works calculated using the method you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed to the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, but he has agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in Section 4, “Information

about donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation.”

• You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg™ License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg™ works.

• You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of receipt of the work.

• You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free distribution of Project Gutenberg™ works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work or group of works on different terms than are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing from the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the manager of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project Gutenberg™ collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may contain “Defects,” such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or other

medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGESExcept for the “Right of Replacement or Refund” described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project Gutenberg™ trademark, and any other party distributing a Project Gutenberg™ electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH

1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you ‘AS-IS’, WITH NO OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS

OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone providing copies of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works in accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg™ electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses, including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this or any Project Gutenberg™ work, (b) alteration, modification, or additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg™ work, and (c) any Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg™

Project Gutenberg™ is synonymous with the free distribution of electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the assistance they need are critical to reaching Project

Gutenberg™’s goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg™ collection will remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure and permanent future for Project Gutenberg™ and future generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at www.gutenberg.org.

Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a nonprofit 501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal Revenue Service. The Foundation’s EIN or federal tax identification number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by U.S. federal laws and your state’s laws.

The Foundation’s business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to date contact information can be found at the Foundation’s website and official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation