Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Adjacent Areas

edited by

Gregory P. Wilson

Department of Biology and Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture University of Washington Seattle, Washington 98195-1800, USA

William A. Clemens Museum of Paleontology University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-4780, USA

John R. Horner Museum of the Rockies Montana State University Bozeman, Montana 59717-0040, USA

Joseph H. Hartman

Harold Hamm School of Geology and Geological Engineering University of North Dakota Grand Forks, North Dakota 58202-8358, USA

Copyright © 2014, The Geological Society of America (GSA), Inc. All rights reserved. Copyright is not claimed on content prepared wholly by U.S. government employees within the scope of their employment. Individual scientists are hereby granted permission, without fees or further requests to GSA, to use a single figure, a single table, and/or a brief paragraph of text in other subsequent works and to make unlimited photocopies of items in this volume for noncommercial use in classrooms to further education and science. Permission is also granted to authors to post the abstracts only of their articles on their own or their organization’s Web site providing that the posting cites the GSA publication in which the material appears and the citation includes the address line: “Geological Society of America, P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140 USA (http://www.geosociety.org),” and also providing that the abstract as posted is identical to that which appears in the GSA publication. In addition, an author has the right to use his or her article or a portion of the article in a thesis or dissertation without requesting permission from GSA, provided that the bibliographic citation and the GSA copyright credit line are given on the appropriate pages. For any other form of capture, reproduction, and/or distribution of any item in this volume by any means, contact Permissions, GSA, 3300 Penrose Place, P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, Colorado 80301-9140, USA; fax +1-303-357-1073; editing@geosociety.org. GSA provides this and other forums for the presentation of diverse opinions and positions by scientists worldwide, regardless of their race, citizenship, gender, religion, sexual orientation, or political viewpoint. Opinions presented in this publication do not reflect official positions of the Society.

Published by The Geological Society of America, Inc. 3300 Penrose Place, P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, Colorado 80301-9140, USA www.geosociety.org

Printed in U.S.A.

GSA Books Science Editors: Kent Condie and F. Edwin Harvey

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

Cover: Acrylic painting copyright © 2013 Donna Braginetz; used with permission. A reconstruction of a latest Cretaceous Hell Creek ecosystem, in which a family of Triceratops drinks from the shores of a meandering river, while in the foreground the large marsupialform mammal Didelphodon vorax gets a good scratch and the aquatic salamander Opisthotriton kayi kicks up a plume of mud as it swims through the shallow waters. Flowering plants including members of the nettle family occupy the frequently flooded river banks, while trees including dawn redwood Metasequoia, Ginkgo, and Erlindorfia give structure to the woodlands.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Foreword

Gregory P. Wilson, William A. Clemens, John R. Horner, and Joseph H. Hartman

Introduction

John R. Horner

1. From Tyrannosaurus rex to asteroid impact: Early studies (1901–1980) of the Hell Creek Formation in its type area

William A. Clemens and Joseph H. Hartman

2. Context, naming, and formal designation of the Cretaceous Hell Creek Formation lectostratotype, Garfield County, Montana

Joseph H. Hartman, Raymond D. Butler, Matthew W. Weiler, and Karew K. Schumaker

3. Assessing the relationships of the Hell Creek–Fort Union contact, Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, and Chicxulub impact ejecta horizon at the Hell Creek Formation lectostratotype, Montana, USA

Jason R. Moore, Gregory P. Wilson, Mukul Sharma, Hannah R. Hallock, Dennis R. Braman, and Paul R. Renne

4. Magnetostratigraphy of the Hell Creek and lower Fort Union Formations in northeastern Montana

Rebecca LeCain, William C. Clyde, Gregory P. Wilson, and Jeremy Riedel

5. Carbon isotope stratigraphy and correlation of plant megafossil localities in the Hell Creek Formation of eastern Montana, USA

Nan Crystal Arens, A. Hope Jahren, and David C. Kendrick

6. A florule from the base of the Hell Creek Formation in the type area of eastern Montana: Implications for vegetation and climate

Nan Crystal Arens and Sarah E. Allen

7. A preliminary test of the press-pulse extinction hypothesis: Palynological indicators of vegetation change preceding the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary, McCone County, Montana, USA .209

Nan Crystal Arens, Anna Thompson, and A. Hope Jahren

8. Euselachians from the freshwater deposits of the Hell Creek Formation of Montana

Todd D. Cook, Michael G. Newbrey, Donald B. Brinkman, and James I. Kirkland

9. Diversity and paleoecology of actinopterygian fish from vertebrate microfossil localities of the Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation of Montana

Donald B. Brinkman, Michael G. Newbrey, and Andrew G. Neuman

10. Extinction and survival of salamander and salamander-like amphibians across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in northeastern Montana, USA

Gregory P. Wilson, David G. DeMar Jr., and Grace Carter

11. Temporal changes within the latest Cretaceous and early Paleogene turtle faunas of northeastern Montana

Patricia A. Holroyd, Gregory P. Wilson, and J. Howard Hutchison

12. A stratigraphic survey of Triceratops localities in the Hell Creek Formation, northeastern Montana (2006–2010)

John B. Scannella and Denver W. Fowler

13. Cranial morphology of a juvenile Triceratops skull from the Hell Creek Formation, McCone County, Montana, with comments on the fossil record of ontogenetically younger skulls

Mark B. Goodwin and John R. Horner

14. Paleobiological implications of a Triceratops bonebed from the Hell Creek Formation, Garfield County, northeastern Montana

Sarah W. Keenan and John B. Scannella

15. Mammalian extinction, survival, and recovery dynamics across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary in northeastern Montana, USA

Gregory P. Wilson

Foreword

For over a century, the Hell Creek and Fort Union formations and their constituent fossil biotas have captivated geologists and paleontologists alike. Much of the early research focused on exposures of these formations in the north-flowing tributaries of the Missouri River in northeastern Montana. Barnum Brown inaugurated these studies describing the Hell Creek Formation from exposures in the valley of Hell Creek, its tributaries, and adjacent areas in Garfield County. Then, in 2002, Geological Society of America Special Paper 361, The Hell Creek Formation and the Cretaceous-Tertiary Boundary in the Northern Great Plains: An Integrated Continental Record of the End of the Cretaceous (edited by Joseph H. Hartman, Kirk R. Johnson, and Douglas J. Nichols), was published. The majority of the chapters in that Special Paper presented new data and insights based on substantial research in western North and South Dakota. In its preface, the editors commented, “…we now realize that we have just begun to mine the information lode available on biotic patterns preserved in this part of the northern Great Plains” (p. v).

The papers in the present volume validate the editors’ prediction. Here, the emphasis shifts back to northeastern Montana to present the results of recent research in the type locality of the Hell Creek Formation. The majority of these chapters are products of research carried out as part of the Hell Creek Project (1999–2010) organized by John Horner, Museum of the Rockies, Montana State University (see Introduction). During this period, the project’s fieldwork was based at camps in the valley of Hell Creek. As the authorship of the following papers indicates, this field and laboratory research involved earth scientists from many North American universities and museums.

This volume brings together the results of some of the research completed under the auspices of the Hell Creek Project. The chapters stem from “Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation and Adjacent Areas,” a symposium organized by Joseph Hartman, Greg Wilson, John Horner, and William Clemens and presented at the Ninth North American Paleontological Convention held in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 2009. The current results of the project illustrate the impacts of refined and new methods and tools for research, such as stable isotope geochemistry, more precise radiometric age determinations, Global Positioning Systems, as well as morphometric analyses and studies of large databases. In tandem, the research questions have evolved to take advantage of the increased precision, quality, and quantity of the data, from determinations of paleoecologies to assessment of ontogenetic sequences, patterns of sedimentation, and basin-level intraformational correlations.

The introduction and the first chapter provide a historical perspective on the paleontological and geological field research that has taken place in the area. John Horner briefly introduces the conception and design of the Hell Creek Project, and William Clemens and Joseph Hartman pick up the historical thread farther back at the beginning of the twentieth century with the horn of Triceratops found by W.T. Hornaday and follow that thread forward to 1980, the Alvarez asteroid extinction hypothesis, and the years beyond.

The next four chapters focus on important aspects of the geology in northeastern Montana. Joseph Hartman and his coauthors describe the lithostratigraphy of a local composite section of the Fox Hills, Hell Creek, and Fort Union formations in the Flag Butte area of central Garfield County, and propose it as the

Wilson, G.P., Clemens, W.A., Horner, J.R., and Hartman, J.H., 2014, Foreword, in Wilson, G.P., Clemens, W.A., Horner, J.R., and Hartman, J.H., eds., Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Adjacent Areas: Geological Society of America Special Paper 503, p. v–vii, doi:10.1130/2014.2503(000). For permission to copy, contact editing@geosociety.org. © 2014 The Geological Society of America. All rights reserved.

lectostratotype for the Hell Creek Formation. To constrain the relative position of the Hell Creek–Fort Union formational contact, the Chicxulub impact ejecta layer, and the K-Pg boundary, Jason Moore and his coauthors apply lithological, geochemical, palynological, and geochronological analyses to a narrow stratigraphic interval in the lectostratotype section. Then, Rebecca LeCain and her coauthors report on their magnetostratigraphic evaluation of the local composite section in the Hell Creek Formation lectostratotype area, as well as a local composite section in the Biscuit Butte area, together spanning the uppermost Fox Hills Formation, the Hell Creek Formation, and the Tullock Member of the Fort Union Formation. And as a step toward a more robust system for intraformational correlation of fossil localities, Nan Arens and her coauthors present a carbon isotope chemostratigraphic curve through the Hell Creek Formation and across the K-Pg boundary into the Tullock Member of the Fort Union Formation.

The following two papers focus on the paleobotanical data from the study area. Nan Arens and Sarah Allen describe a megaflora from the lower Hell Creek Formation, comparing it with the well-studied floras from North Dakota and applying leaf physiognomy methods to it to reconstruct local paleoclimate. Then, Arens and her coauthors present a stratigraphic succession of palynofloras immediately across the K-Pg boundary that they use to test the “press-pulse” extinction hypothesis.

The last eight chapters provide new data and analyses of the vertebrate fauna from the study area. In the chapters by Todd Cook et al. and Donald Brinkman et al., the authors revise the fossil record of freshwater sharks, rays, and actinopterygian fish, respectively, from the Hell Creek Formation and the Tullock Member. They then discuss the paleobiogeographic, temporal, and paleoecological context of these data. The papers by Gregory Wilson et al., Patricia Holroyd et al., and Gregory Wilson investigate taxonomic diversity dynamics in salamanders and salamander-like amphibians, turtles, and mammals, respectively, leading up to, across, and following the K-Pg boundary. The results of these analyses, which incorporate relative abundance data, provide compelling evidence for a more complex K-Pg mass extinction scenario, a characteristic “survival” fauna, and a mosaic pattern of recovery. The dinosaur genus Triceratops is the focus of three papers in this section. John Scannella and Denver Fowler review the stratigraphic and historical context of 27 significant Triceratops localities, many of which have been excavated as part of the Hell Creek Project, and stress the importance of these data in evolutionary and ontogenetic studies and future targeted collecting. Mark Goodwin and John Horner describe a skull of a juvenile Triceratops from the Hell Creek Formation and reflect on how collector bias has led to under-representation of nonadult specimens in our collections. Sarah Keenan and John Scannella then provide a detailed evaluation of the taphonomy of a Triceratops bonebed and its implications for our understanding of the paleobiology of this common Hell Creek dinosaur.

In sum, we are very excited about the advances that are presented in this volume, but we echo the editors of Special Paper 361 in recognizing that the chapters in this volume are building blocks or starting points for additional research as we continue to mine a rich lode of geo- and biohistory data preserved in the strata bounding the K-Pg boundary.

Stratigraphic Conventions

We use the Tullock as a member of the Fort Union Formation following the convention of the U.S. Geological Survey. We use the acronym K-Pg to reflect the splitting of the Tertiary into the Paleogene and Neogene by the International Stratigraphic Commission.

Acknowledgments

We are tremendously grateful for financial support from Nathan Mhyrvold, the Kohler family, the U.S. Department of Energy (to JHH), the Energy & Environmental Research Center of the University of North Dakota (JHH), the University of California Museum of Paleontology, and others listed in individual chapters. We would also like to acknowledge assistance from the various federal and state agencies, community members, and landowners who have made this research possible. Specifically, we would like to thank the Bureau of Land Management (Gary Smith, Doug Melton), Charles M. Russell Wildlife Refuge (Bill Berg, Nathan Hawkaluk), Montana State Department of Natural Resources and Culture (Patrick Rennie), private landowners (McKeever, Engdahl, Hauso, Twitchell, Olson, McDonald, Trumbo, Bliss, Abe, Leo, and Virginia

Murnion, Isaacs, Burgess, Thomas, and Pinkerton families), the Hell Creek State Park staff (Mary Pat Watson, Jerry Hensley, Dave Andrus, Lilly Johnston, Hally McDonald), members of the business community of Jordan, Joe Herbold (The Office), Jim and Ed Ryan, the Hagemans, Clint and Deb Thomas, the Fosters and FitzGeralds, and Clyde and Lori Phipps. We are also indebted to the referees who critically reviewed the manuscripts and Edite Forman for her tour-de-force copyediting all of the manuscripts.

Gregory P. Wilson

William A. Clemens

John R. Horner

Joseph H. Hartman

Introduction

In 1998, I proposed a project to Nathan Myhrvold in which we would undertake what we believed would be the largest dinosaur (and associated paleontological specimens) collection effort in the United States, rivaling any of the expeditions of the 1800s. We named it the Hell Creek Project, and planned for an initial duration of five years. Our goal was to amass a huge, new collection of fossil remains from the Upper Cretaceous, Hell Creek Formation of eastern Montana, all of which would have precise geologic and geographic data. Nathan agreed to underwrite the majority of the field costs, and we then invited a number of primary researchers who we thought would best represent the various aspects of the project. The senior personnel included Bill Clemens (University of California, Berkeley, fossil mammals), Joe Hartman (University of North Dakota, fossil mollusks), and myself (Montana State University, dinosaurs). Each of us then invited other senior researchers including Nan Arens (then of University of California, Berkeley, paleobotanist), Mark Goodwin (University of California, Berkeley, dinosaurs), Jim Schmitt (Montana State University,

Creek base camp, 1 July 2000.

Horner, J.R., 2014, Introduction, in Wilson, G.P., Clemens, W.A., Horner, J.R., and Hartman, J.H., ed., Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Adjacent Areas: Geological Society of America Special Paper 503, p. ix–x, doi:10.1130/2014.2503(001). For permission to copy, contact editing@geosociety.org. © 2014 The Geological Society of America. All rights reserved.

Hell

stratigraphy and sedimentology), and Mary Schweitzer (North Carolina State University, biomolecules). Each senior-level person then brought in a number of graduate students. The project got underway during the summer of 1999, based at Hell Creek State Park on the southern shores of Fort Peck Reservoir in Garfield County. The base camp was set up to sustain more than 50 people, and support as many as four concurrent satellite camps. Boats and all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) were purchased, and use of a helicopter was donated by the Windway Capital Corporation of Sheboygan, Wisconsin. With boats, ATVs, and a helicopter we were able to collect large specimens from all areas of the study region. Nothing was inaccessible.

The helicopter was fitted with a high-resolution video camera with which we were able to create highresolution aerial transects, and track particular beds over large areas. Some areas were mapped using LIDAR (light detection and ranging), and all sites were placed into a high-resolution stratigraphic column.

At the end of the five-year period, we had amassed an enormous collection of specimens and data, mostly from the lower third of the formation, a unit that had previously been under-collected for logistical reasons. During those first few years, we also came to realize that mudstones contained remains that had also been, for the most part, ignored because of a perception of poor preservation. It was in the mudstones that we found numerous disarticulated, juvenile specimens of Triceratops

In 2004, with a grant from the Smithsonian Institution, we undertook a second five-year project (Hell Creek Project II) to mirror the first by continuing to amass large quantities of fossils and geologic data, but to do so from the middle and upper units of the Hell Creek Formation. We moved our base camp east and set up on the Twitchell Ranch, where we worked areas in northeastern Garfield County. So much material was found that the five-year project extended into eight years.

In the end, vast collections of plant, invertebrate, lower vertebrate, dinosaur, and mammal specimens had been collected. The Museum of the Rockies crews had collected more than 100 new specimens of Triceratops, and a dozen new specimens of Tyrannosaurus. So much material was collected that specimen preparation will likely continue for another decade. As a result, many of the papers presented here are preliminary, and data from this collecting effort will continue to be published for many years to come.

John R. Horner May 2012

The Geological Society of America Special Paper 503 2014

From Tyrannosaurus rex to asteroid impact: Early studies (1901–1980) of the Hell Creek Formation in its type area

William A. Clemens*

Museum of Paleontology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720-4780, USA

Joseph H. Hartman

Department of Geology and Geological Engineering, University of North Dakota, Grand Forks, North Dakota 58202-8358, USA

ABSTRACT

Over a century has passed since 1901 when W.T. Hornaday showed a fragment of a horn of Triceratops found in the valley of Hell Creek to H.F. Osborn at the American Museum of Natural History. The following year Osborn’s assistant, Barnum Brown, was dispatched to eastern Montana and began investigations of its geology and paleontology. By 1929, Brown had published a geological analysis of the rocks exposed in the southern tributaries of the Missouri River, named the Hell Creek Formation, and published studies of some of the dinosaurs discovered there. Parts of his collections of fossil mollusks, plants, and vertebrates contributed to research by others, particularly members of the U.S. Geological Survey. From 1930 to 1959, fieldwork was slowed by the Great Depression and World War II, but both the continuing search for coal, oil, and gas as well as collections of fossils made during construction of Fort Peck Dam set the stage for later research. Field parties from several museums collected dinosaurian skeletons in the area between 1960 and 1971. In 1962, concentrations of microvertebrates were rediscovered in McCone County by field parties from the University of Minnesota. Ten years later, field parties from the University of California Museum of Paleontology began collecting microvertebrates from exposures in the valley of Hell Creek and its tributaries. The research based on this field research provided detailed geological and paleontological analyses of the Hell Creek Formation and its biota. In turn, these contributed to studies of evolutionary patterns and the processes that produced the changes in the terrestrial biota across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary.

*bclemens@berkeley.edu

Clemens, W.A., and Hartman, J.H., 2014, From Tyrannosaurus rex to asteroid impact: Early studies (1901–1980) of the Hell Creek Formation in its type area, in Wilson, G.P., Clemens, W.A., Horner, J.R., and Hartman, J.H., eds., Through the End of the Cretaceous in the Type Locality of the Hell Creek Formation in Montana and Adjacent Areas: Geological Society of America Special Paper 503, p. 1–87, doi:10.1130/2014.2503(01). For permission to copy, contact editing@ geosociety.org. © 2014 The Geological Society of America. All rights reserved.

INTRODUCTION

From the discovery of dinosaurs in the valley of Hell Creek in 1901 to 1980, when a hypothesis of their demise as a consequence of an asteroid’s impact was proposed (Alvarez et al., 1980), studies of the Hell Creek Formation in northeastern Montana have contributed significantly in shaping paleontological and geological research. Today, Hell Creek is one of the streams empting northward into Fort Peck Reservoir, a section of the Missouri River dammed in the 1930s, and it is hundreds of miles from the nearest ocean. In contrast, some 67 m.y. ago, this area was part of the deltaic western coastline of a dwindling Western Interior Sea. Stretching from the Arctic Ocean to the precursor of the modern Gulf of Mexico, this sea bisected the North American continent through much of the Late Cretaceous.

The Hell Creek Formation occupies part of the western Williston Basin, an area of deposition since the early Paleozoic. It overlies the Fox Hills Formation, which is made up of the sediments deposited along the coastline of the retreating Western Interior (Bearpaw–Pierre) Sea. In the valley of Hell Creek, the basal strata of the Hell Creek Formation are largely sandy coastal deposits grading upward into beds of dominantly finer-grained siltstones and claystones. Large sandy channel deposits at various levels through the formation are traces of extensive river systems that traversed the area during the latest Cretaceous and earliest Paleocene. Very near the end of the Cretaceous, the sedimentary regime changed. The western Williston Basin became wetter, and locally swamps began to form. Lignites that developed in these swamps characterize the Tullock and overlying Ludlow Members of the Fort Union Formation (see Hartman et al., this volume). Locally, the Hell Creek–Fort Union contact is placed at the base of the stratigraphically lowest, laterally extensive lignite. Deposition of the precursors of these lignites began at different times in different areas throughout the region. In Garfield and McCone Counties, this contact has been shown to be time transgressive (Swisher et al., 1993; Arens et al., this volume, Chapter 5). Current estimates suggest the Hell Creek Formation was deposited during approximately the last 1.8 m.y. of the Cretaceous and, in some areas, the earliest Paleocene (Wilson, 2005; Wilson et al., this volume; also see earlier estimates in Hartman et al., 2002).

The history of research focused on the Hell Creek Formation and its biota prior to 1980 can be roughly divided into four periods: (1) early exploration (1901–1929), (2) evaluating coal deposits and building Fort Peck Dam (1930–1959), (3) new research programs (1960–1971), and (4) closer inspection (1972–1980). These intervals chart changes in emphases and technologies in field and laboratory studies as well as the emergence of new questions and areas of research.

For reference, throughout the chapter, we use the following acronyms, abbreviations, and locality designations.

Institutional Acronyms

AMNH—American Museum of Natural History, New York, New York, USA

AMNH-FI—American Museum of Natural History Fossil Invertebrates

AMNH-IP—American Museum of Natural History Invertebrate Paleontology

LACM—Los Angeles County Museum, now Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Los Angeles, California, USA

MRC—Missouri River Commission, USA

PWA—Public Works Administration, USA

UCMP—University of California Museum of Paleontology, Berkeley, California, USA

USACE—U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

USGS—U.S. Geological Survey

USNM—U.S. National Museum, Washington, D.C., USA

Abbreviations

kj—kilojoule

km—kilometer

k.y.—thousand years

m—meter

Ma—million years ago mi—mile

NALMA—North American land mammal age

Locality Designations

Locality designations beginning with the letter “L,” e.g., L0053, are from a locality numbering system for mostly continental molluscan localities in North America maintained by Joseph Hartman at the University of North Dakota. Locality designations beginning with the letter “V,” e.g., V72085, “D,” e.g., D7272, or “PB,” e.g., PB99023 are recorded in the UCMP catalog, which is available at www.ucmp.edu/science/collections .php. Locality designations beginning with USGS, e.g., USGS 8787, are recorded in USGS Mesozoic locality catalogs, housed at the USGS offices in Denver under the care of Kevin (Casey) McKinney (catalogs were formerly kept by the USGS at the U.S. National Museum, Washington, D.C.).

EARLY EXPLORATION (1901–1929)

Discovery and the First Years of Collecting

Dawson County in northeastern Montana was one of the last areas of the continental United States to be settled (Fig. 1). At the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, it was still an area of largely unplowed plains that had sustained the last large herd of American bison (Lepley and Lepley, 1992). In October 1901, William T. Hornaday, then director of the New

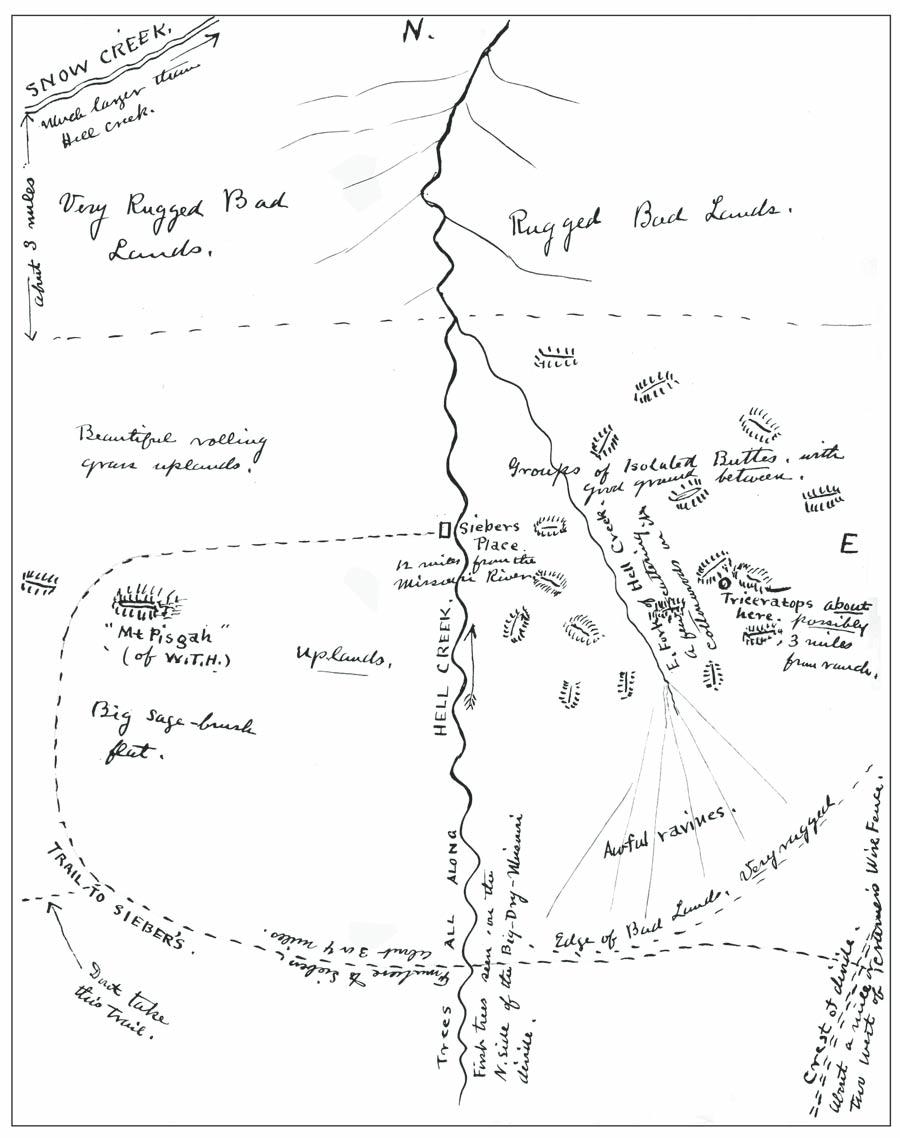

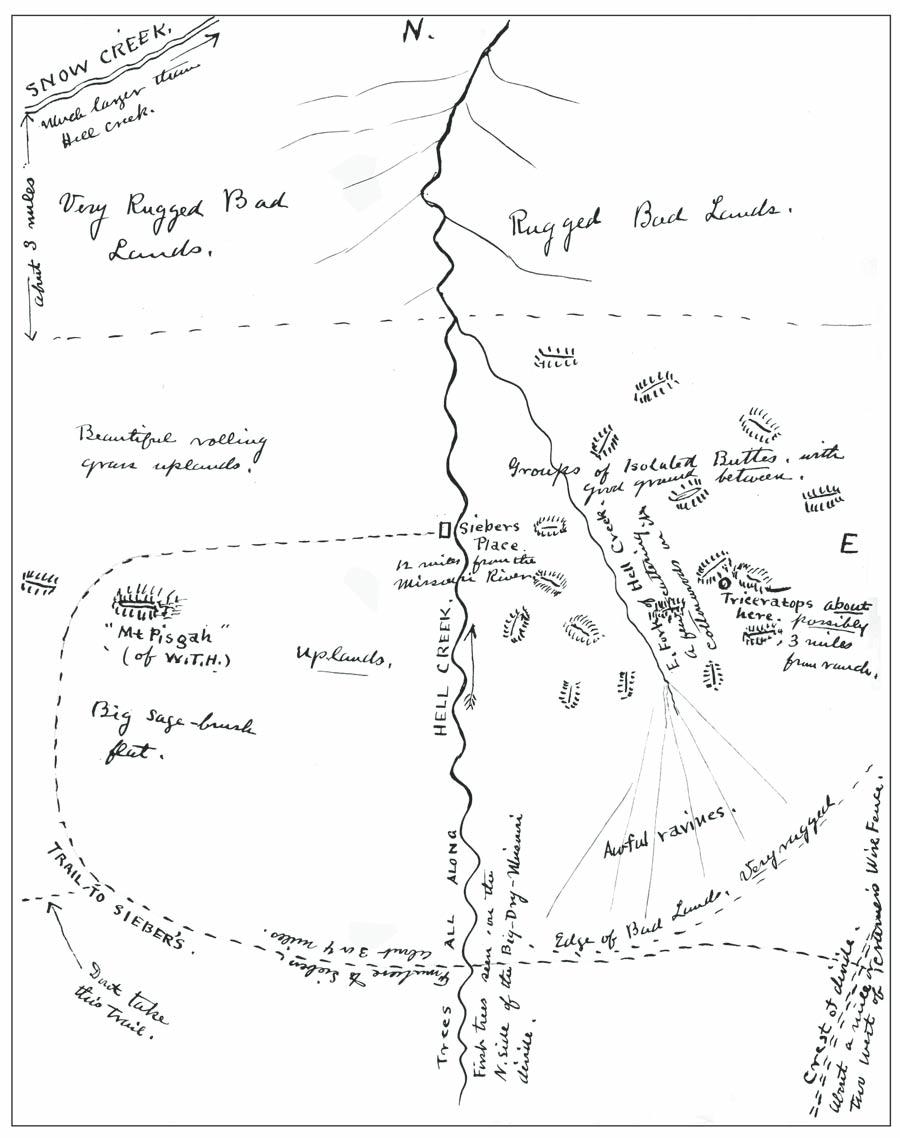

Figure 1. (A) A map of Dawson County published by Cram (1907) included a few landmarks and river tributaries. Towns and other settlements were concentrated in the valleys of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. In 1902, Barnum Brown began his fieldwork based at Miles City. He collected mollusks from outcrops along the Powder River near Hockett. These would be erroneously referred to in Whitfield’s (1903; AMNH-FI catalog) report on the “Hell Creek” fauna. Brown had little success collecting near Forsyth. Then he moved on through Jordan to the valley of Hell Creek. (B) In his first report on the Hell Creek Formation, Brown (1907) provided only a sketch map of the area he had prospected in northern Dawson County. In a footnote, he directed the reader to this more detailed and “very accurate” map of Dawson County published by E.S. Cameron (1907) to illustrate his study of the birds of the area. Abbreviations: CC—Crooked Creek; HC—Hell Creek; SC—Snow Creek; 7BC—Seven Blackfoot Creek.

York Zoological Society, returned to northeastern Montana. He joined L.A. Huffman, a pioneer photographer who had a studio in Miles City; Jim McNaney, a local cowboy; and others in Miles City. The group headed for the valley of Hell Creek, where they came across the cabin of Max Sieber, a former Texas cowboy who turned bison hunter and then became a wolf hunter. The group camped at Sieber’s place for two weeks (Fig. 2). During their stay, Sieber showed Hornaday a nearby area where vertebrate fossils were weathering out of the rock. Hornaday took three fragments of the nasal horn of a Triceratops, first intended for use as a paper weight (Brown, 1907), back to New York. On his return, he showed the fossil and Huffman’s photographs to H.F. Osborn at the American Museum of Natural History. Osborn considered them sufficiently interesting to include the valley of Hell Creek on the list of areas to be prospected by Barnum Brown the following year (Hornaday, 1925, p. 79–80).

In May 1902, Hornaday wrote to his long-time friend Jim McNaney asking him if he would guide Brown to Hell Creek:

A friend of mine who is connected with the American Museum of Natural History, here, wants to go out to Hell Creek to look for fossil bones, where I found some last October, and where M.A. Sieber found others, east of his ranch. He would like to go up for a week or ten days, flying light, to see if it would pay to make a stay of a month or so. (M.H. Brown and Felton, 1955, p. 89)

Barnum Brown traveled to Miles City later in 1902 (Fig. 1A). From here, he prospected to the northwest of Miles City near the town of Forsyth with little success. Similarly, his prospecting in the Powder River drainage to the south of Miles City was not very successful in terms of discovery of vertebrates, but continental mollusks were collected from the Tullock Member at a locality “below Hockett” (locality L0053, relocated by Hartman as L3960). In early July, equipped with a sketch map provided by Hornaday that showed the location of Sieber’s cabin (Fig. 3), Brown traveled northward to the town of Jordan and then on to Hell Creek. Here, he and his crew camped near Max Sieber’s now-abandoned cabin. His field crew included Dr. Richard Swan Lull, who would go on to a distinguished career in paleontology at Yale University, and Philip Brooks, a student from Amherst. Later, Brown recounted that after their arrival, while the cook was preparing supper, he walked a short distance up Hell Creek and located bones running into a hillside (Dingus and Norell, 2010, Appendix 2, p. 309–311). The partial skeleton preserved here would become the type specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex A detailed account of the techniques used in collecting part of this skeleton and recovery of two specimens of Triceratops in 1902 was given by Lull (in Hatcher, 1907, p. 182, 185–187; also see Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 106–109). Mollusks were collected from exposures of the Hell Creek Formation in the valley of Snow Creek, a tributary of the Missouri River to the northwest of Hell Creek, and described by Whitfield (1903). Collecting fossil vertebrates, mollusks, and plants kept Brown and his crew occupied for more than the projected “week or ten days” during the summer. Over 3 months elapsed between their arrival at Hell

Creek in July and the closing of camp and shipping of their extensive collections from Miles City in October (Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 88–93).

What was the impetus behind sending Brown to check reports of the discovery of dinosaurs in eastern Montana? At the beginning of the twentieth century, three American museums— the American Museum of Natural History in New York, the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and the Field Columbian Museum in Chicago, Illinois—were competing in building exhibits of vertebrate fossils, particularly skeletons of dinosaurs (Rangier, 1991). In the early twentieth century, field crews from all three museums were searching for dinosaurian remains in the Western Interior of North America. An expedition from the Field Museum in 1904 led by Elmer S. Riggs worked in southeastern Montana, near the town of Ekalaka. They secured some dinosaurian remains (Brown, 1907; Knowlton, 1909, p. 190) and an exceptionally well-preserved shell of a turtle, which served as the type specimen of Basilemys sinuous (Riggs, 1906). Earlier, Earl Douglass (1902), collecting for the Carnegie Museum, explored to the west of Hell Creek near the Crazy Mountains and discovered fragmentary dinosaur bones as well as mollusks. The search for exhibit-quality specimens of dinosaurs was not limited to these three museums. In 1895, S.W. Williston led an expedition from the University of Kansas into eastern Wyoming with the goal of collecting a skull of Triceratops for display at the university. Going to the valley of Lance Creek in eastern Wyoming, an area where J.B. Hatcher (1896) had collected a number of skulls of the beast, they found and collected a skull of Triceratops near the confluence of Lance and Lightning Creeks. Two years later, the skull was on display at the university. Two young men, Barnum Brown and Elmer Riggs, were members of that expedition (Kohl et al., 2004; Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 34–37).

After his very successful expedition to the valley of Hell Creek in 1902, Brown did not return to northeastern Montana in 1903. The staff at the American Museum of Natural History was deeply involved with the difficult preparation of the partial skeleton of the dinosaur that would be named Tyrannosaurus rex. That year Brown was occupied with fieldwork in Arkansas, South Dakota, and Wyoming. His prospecting in Jurassic deposits on the flanks of the Bighorn Mountains in Wyoming resulted in the discovery of dinosaurian remains in an area to which he would frequently return in subsequent years (Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 95).

In April 1904, W.H. Utterback (Fig. 4B) from the Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh, began his field season prospecting outcrops of the Judith River Formation exposed along the Musselshell River, which then formed the western boundary of Dawson County. He found this “a losing proposition” (Utterback, 1904a) and received permission from his boss, J.B. Hatcher (Hatcher, 1904), to turn his attention eastward to outcrops of what was then named the Laramie Formation or Beds. By August, he was at work in the area around Hell Creek. Here, his luck changed. Among the fossils he collected were two skulls of Triceratops (Utterback, 1904b, 1904c; Hatcher, 1907, p. 182), “good” material of hadrosaurs (Utterback, 1904b), and part of a jaw of

Figure 2. (A) In 1901, W.T. Hornaday surveyed the “Breaks of the Missouri . . . looking toward Snow Creek” (Brown and Felton, 1955, p. 89, their figure 39). The badlands forming the Breaks included outcrops of the Bearpaw, Fox Hills, and Hell Creek Formations. (B) The dugout at Max Sieber’s home on the bank of Hell Creek in 1901. From left to right: Max Sieber, L.A. Huffman, and W.T. Hornaday. The following year, Barnum Brown discovered the first skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex ~150 yards (300 m) upstream from the dugout. (L.A. Huffman photographs are courtesy of Coffrin’s Old West Gallery, Bozeman, Montana.)

Figure 3. Directions to the “fossil country” on Hell Creek. This map, sketched by W.T. Hornaday, shows the area where he and Max Sieber had collected parts of a horn core of Triceratops. This discovery led Barnum Brown to Hell Creek in 1902. “Mt. Pisgah,” shown on the map, was not a local name for a landmark. Hornaday probably added the biblical reference to Mt. Pisgah (Deuteronomy 34:1) to highlight his view of the significance of the discovery of remains of dinosaurs (see Hornaday, 1925, p. 62). The map is part of letter from Hornaday to Barnum Brown, 29 May 1902 (map courtesy of American Museum of Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology Archives, 2:3, Box 2, Folder 6).

4. (A) Prairie trail from Miles City to the Hell Creek badlands (B. Brown, 1902 expedition; photograph courtesy of American Museum of Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology Archives, 7:2, Box 3, page 7). (B) In 1904 and 1905, William H. Utterback, a preparator and collector for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, prospected for fossils in the valley of Hell Creek. During his 1904 field season, he collected a fragment of a jaw of Tyrannosaurus and two skulls of Triceratops. Here, he is shown preparing one of the skulls. (Photograph in Carnegie Museum of Natural History Vertebrate Paleontology Archives; used with permission.)

Tyrannosaurus (McIntosh, 1981; McGinnis, 1982). During the summer of 1904, Brown and his first wife, Marion, briefly visited the valley of Hell Creek and met Utterback (AMNH Annual Report, 1904; M. Brown, 1960). Before moving westward to prospect exposures of the Judith River and overlying Bearpaw Formations along the Mussellshell River, Barnum and Marion found a few specimens of dinosaurs but covered the bones in hopes of collecting them later (Brown, 1904).

Continuing the Search for Dinosaurs and Other Fossils, 1905–1910

As the beginning of the 1905 field season approached, Osborn (Fig. 5A) was writing his description and analysis of what would become the type specimen of Tyrannosaurus rex. Spurred by the possibility of finding more elements of this skeleton, Osborn sent Brown back to Montana. Utterback had returned to the valley of

Figure 5. (A) A young Henry Fairfield Osborn would later have oversight and provide funding for the explorations conducted by Barnum Brown in his studies in the Missouri Breaks (photograph courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library, image 333694).

(B) Barnum Brown (cropped from a vintage Como Bluff photograph, 1897; see Dingus and Norell, 2010, their figure 6). (Photograph courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library, image 17808.)

Figure

Hell Creek earlier in the spring of 1905. Finding that the drought of the previous year in Montana had continued and not discovering material worth collecting, he shifted his fieldwork to the south (Utterback, 1905). Brown arrived after Utterback had left and again set up camp near Sieber’s abandoned cabin (Fig. 6). Through the summer, Brown and his crew extended the quarry they had opened in 1902 (Fig. 7). Extensive quarrying, involving blasting the overlying sediments and using a horse-drawn scraper to remove the debris, yielded additional elements of the skeleton.

In July, Osborn (1905a) wrote to Brown, “I have been thinking a great deal about your work. I think you ought to spend the larger part of your time prospecting, taking in as large a radius of the country as you can, rather than quarrying and taking out specimens. I would rather pay another assistant to quarry.” Excavation of the partial skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex continued through the summer until late August and occupied most of Brown’s attention. Before returning to New York he was able to prospect north of the Missouri River, where he found a hind limb of T. rex He also worked to the east in the Missouri Breaks and became involved negotiations concerning collecting a hadrosaur skeleton that became known as “Sensaba’s Mule.”

The Sensaba family was not mentioned by Hornaday (1902) in his letter to Brown. It is clear, however, that they were early settlers in the valley of Hell Creek and were mentioned in Brown’s study of the Hell Creek beds (Brown, 1907). A plat map drawn up in 1914 (Fig. 8) shows that, at that time, the Sensaba (misspelled as Sensabi) family owned at least two cabins in the valley of Hell Creek. The western cabin was the beginning of the main Sensaba Ranch (Lester Engdahl, 1984, personal commun.). The eastern cabin would become part of the Elmer Trumbo Ranch. The Sensaba family had written to the AMNH offering to sell the hadrosaur skeleton to which they laid claim. Brown found time near the end of his field season in 1905 to casually inspect the skeleton. After some complex negotiations, the following year the skeleton was obtained for a much reduced price (see Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 106–111).

The activities in Montana of collectors from other museums had not gone unnoticed in New York. In October, at the end of the 1905 field season in Montana, Osborn wrote Brown, “It is evident that we have a good field for next season. In the meantime we must keep very quiet about it. I am tired of prospecting for the benefit of other Museums. Marsh’s epigram ‘don’t go duck hunting with a brass band’ is very appropriate” (Osborn, 1905b).

Barnum Brown returned to Montana in the summer of 1906 and continued collecting and prospecting. That fall, in New York, he turned his attention to preparing his report on the Hell Creek beds. He remained in New York through the summer of 1907 and completed his manuscript, which was published in October (Brown, 1907). In this paper, Brown discussed and illustrated geological observations made in the valley of Hell Creek and, to the east, in the valleys of Crooked and Gilbert Creeks. He also commented on the geology of areas approximately 10 mi (~16 km) north of the Missouri River. Brown made only passing reference to exposures of the Hell Creek Formation in the valley of Big Dry Creek.

One of the challenges that Brown faced in preparing his report was the lack of detailed, accurate maps of the area he was exploring. After the Lewis and Clark expedition, the Missouri River became a major route of transportation into western Montana. By the late 1800s, river steamers traveled the river past the Missouri Breaks. The Missouri River Commission’s (1892–1895) map of the course of the river (Fig. 9) shows in detail the relationships of mouths of tributary drainages but depicts only the areas immediately adjacent to the Missouri River. In contrast, beyond the banks of the Missouri, early maps of the northern part of Dawson County appear to be generalized sketches. Brown (1907, p. 825) was acutely aware of the situation, “[t]his area is unsurveyed and all published maps are inaccurate in name, course and size of most of the streams.” He made a sketch map (Fig. 10) to accompany his report. In a footnote to his paper (Brown, 1907, p. 825), he referred the reader to “a very accurate map” that had just been published by Cameron (1907) as part of his study of the birds of Custer and Dawson Counties (Fig. 1B). Although an improvement over Brown’s and other maps (e.g., Cram’s [1907] map; Fig. 1A), it still suffered from inaccuracies and lack of detail in depiction of the areas studied by Brown. In the following decade, with increased settlement of the Missouri Breaks and areas to the south, surveys began to produce plat maps (e.g., Fig. 8), which much more accurately depicted the courses of tributaries of the Missouri and recorded land ownership.

During the summers of 1906, and then 1908, 1909, and 1910, Brown was drawn eastward from the headwaters of Hell Creek. He shifted his work to the valleys of Crooked Creek and Gilbert Creek (Fig. 10). Even farther to the east, in the summer of 1908, Brown discovered and, with the assistance of Peter Kaisen, collected another skeleton of Tyrannosaurus on the eastern side of the valley of Big Dry Creek near the mouth of Bug Creek. This site is now in McCone County (Fig. 11, no. 24). Brown and Kaisen returned to the area in 1909 (Brown, 1933). In 1910, with the completion of collection of a hadrosaur skeleton discovered the previous year, Brown moved his fieldwork north to Alberta (Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 131–132). Here, he would spend several years collecting from exposures along the Red Deer River. For more detailed and illuminating accounts of Barnum Brown’s fieldwork along the Red Deer River and surrounding area, see Dingus (2004, chapter 6) and Dingus and Norell (2010, chapters 5–7).

Description and Analysis of the Vertebrate Fossils Discovered by Brown and His Associates

Osborn, Brown, and Lull studied and published analyses of some of the fossil vertebrates discovered in the Hell Creek Formation between 1902 and 1910. Osborn’s publications (e.g., 1905c, 1906) and development of a spectacular exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History (Osborn, 1913) focused attention on Tyrannosaurus rex. Lull (1903) described a skull of Triceratops collected in 1902. Brown’s (1906, 1908, 1933) work on dinosaurs included a description of Ankylosaurus and recognition of a new family of armored dinosaurs.

Figure 6. (A) A view of the valley of Hell Creek looking downstream. The photograph was taken from the bluff containing Barnum Brown’s Tyrannosaurus quarry (quarry 1) looking toward the north and the area where Max Sieber had a cabin, dugout, outbuildings, and corrals (black arrow). Construction of the house, partly hidden in the grove of cottonwood trees to the left of the creek, was started by Albert and Olga Engdahl in 1916. Photographs in the American Museum of Natural History archives show that in 1902 and 1905, Barnum Brown set up his camps around this grove of cottonwoods (Clemens, personal collection, 1984). (B) Barnum Brown working in quarry 2 in 1902. A description of collecting this and other partial skeletons from the area was given by Lull (in Hatcher, 1907, p. 182, 185–187; also see Dingus and Norell, 2010, p. 106–109). Quarry 2 yielded a mandible and postcranial elements of Triceratops, American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) specimen number 971. (Photograph courtesy of American Museum of Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology Archives, 7:2, Box 3, page 4.) (C) Looking eastward at quarry 2. Here, unlike quarry 1, the vertebrate fossils were preserved in siltstones. Almost 80 yr of erosion have not greatly modified the quarry. Lester Engdahl, seated at the quarry’s edge, and his parents settled in the valley of Hell Creek. Lester’s recollections of local oral histories were invaluable in tracing the course of Barnum Brown’s work in the area. Beginning in the 1960s, he also greatly facilitated LACM and UCMP field research (Clemens, personal collection, 1984).

Figure 7. (A) Quarry 1, the type locality of Tyrannosaurus rex, in 1905, when Barnum Brown reopened the quarry (photograph courtesy of American Museum of Natural History Library, image 18172). (B) Enlargement of part A to more clearly show the size of the quarry and excavation with a horsedrawn scraper. (C) Looking eastward across the valley of Hell Creek in 1984 at the site of quarry 1. The section in the face of the hill, which Barnum Brown dubbed Sheba Butte, is 33.5 m (106 ft) thick and dominantly composed of cross-stratified, fine- to medium-grained sandstones (Fastovsky, 1987). Almost 80 yr of erosion have removed most traces of Brown’s extensive quarry (Clemens, personal collection, 1984).

Figure 8. Prepared in 1914, this plat map of T. 21 N., R. 36 E. documents the beginnings of settlement of the valleys of Hell Creek and Snow Creek. The “Sensibi” (the cartographer’s misspelling of the family name Sensiba) and McDonald cabins were present in the area of the valley of Hell Creek, where, in 1902 and 1905, Barnum Brown centered his quarrying. Here, he opened three quarries. Excavation at quarry 1 (Q1), the type locality of Tyrannosaurus rex, was not completed until 1905. At quarries 2 and 3 (Q2, Q3), he collected parts of skeletons of Triceratops in 1902. The quarter-sections containing these quarries are marked. The plat map is in the Garfield County Courthouse and was copied with the help of Jo Ann Stanton, deputy clerk and recorder.

Figure 9. The mouths of Hell Creek and Snow Creek (Paradise or Little Snow) were “well” located on Missouri River Commission maps (Missouri River Commission, 1892–1895, plates 2, 76, 77). The latitude and longitude ticks and relative placement of the confluences of tributaries to the Missouri River to the northeast of Round Butte were not considered in the construction of reconnaissance maps prepared by Hornaday (Fig. 3 herein) or by Brown (Fig. 10A herein).

Figure 10. (A) Part of Barnum Brown’s sketch map (1907, his figure 1) modified with enhanced names of some tributaries to the Missouri River. The symbols indicate the locations of some sites where material was collected in 1902, 1905, and 1906. Comparison with the Missouri Commission map (Fig. 9) or a modern U.S. Geological Survey topographic (Fig. 11 herein) shows that, relative to Round Butte and the abrupt northward deflection of the Missouri River just downstream, the mouths of Snow Creek and Hell Creek have been placed too far to the northeast. In contrast, the locations of the fossil localities shown along the individual tributaries are appropriate given the scale of the map. (B) This is part of a map, labeled “Original Sketch Map of Hell Creek, Mont.[,] Mr. Barnum Brown – Am. Mus. Nat. Hist.,” found in the AMNH Vertebrate Paleontology Archives. It is a copy of the published map (Brown, 1907, his figure 1) apparently annotated by Barnum Brown. It includes symbols identifying the material collected: + = Triceratops, = Tyrannosaurus, = Trachodon, = Ankylosaurus (a clearer key has been added). We have numbered the localities (see Fig. 11 for an explanation). The map is not dated. Inclusion of the location of the second skeleton of Tyrannosaurus between Rock and McGuire Creeks (locality 24), which was discovered in the summer of 1908, indicates that it was prepared later that year or more recently. (Map courtesy of American Museum of Natural History, Vertebrate Paleontology Archives.)

Figure 11. Barnum Brown’s (1907, his figure 1) locality map (in part) rectified to a modern U.S. Geological Survey base map. Locality numbers were added by us to refer to map locations plotted by Brown. Underlined numbers are localities added on the map annotated after the 1908 field season (Fig. 10). Symbols on Brown’s unpublished map (+ = Triceratops, = Tyrannosaurus, = Trachodon, = Ankylosaurus) are given by the following numbers: Localities 1 and 2 are localities on Seven Blackfoot Creek that yielded material of Triceratops (see Fig. 10B). Fossils of Triceratops were also found at locations 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 12, 15, 16, 17, 18, and 23; fossils of Tyrannosaurus were found at locations 3, 24, and 25; Trachodon (Edmontosaurus) material was found at locations 7, 9, 13, 14, 19, 21, and 22; and Ankylosaurus was found at location 20.

W.H. Hornaday did not lose interest in the consequences of bringing the fragmentary horn of a Triceratops to the attention of his friend, H.F. Osborn. Among his many interests, Hornaday was very active in the field of conservation, particularly in the preservation of bison, which had been hunted almost to extinction. He published a number of widely read books and articles and was not reticent in writing about the scenery in and around the valley of Hell Creek and the fossils discovered there (e.g., Hornaday, 1924, 1925, 1931). His article on “The BadLands of Hell Creek,” republished in “A Wild-Animal RoundUp” (Hornaday, 1925, p. 54–80), includes an L.A. Huffman photograph of Max Sieber’s cabin, dugout, and the outbuildings around his home.

Throughout his fieldwork, Brown and his crews collected a variety of other vertebrates, invertebrates, and fossil leaves from

the Hell Creek Formation, the overlying lignites, and the Fort Union Formation. Among the vertebrate fossils they collected and described were well-preserved skeletons of Champsosaurus from the lignite beds (Brown, 1905b). The discovery of several genera of turtles, crocodiles, and “fish” was noted in a summary list of vertebrates (Brown, 1907), which was revised by Brown (1914) after completion of his fieldwork in the area.

In 1906, Brown and his field crew collected a few mammalian teeth from exposures of the Hell Creek Formation in the valley of Crooked Creek. They discovered another locality that yielded mammals in the valley of Gilbert Creek (AMNH Annual Report, 1906). A photograph shows Peter Kaisen and Edward Frich at work “washing mammal dirt through sack” (AMNH photograph 785–18184 [79E-3–11]). Decades later, applications of a much more refined technique of underwater screening would

Clemens and Hartman

greatly enhance the samples of mammals and other microvertebrates from the Hell Creek Formation and the Tullock Member. Simpson (1927, 1929) described the collection of mammalian fossils made by Brown’s crew in the valley of Crooked Creek and the “Cameron Collection,” which was reported to have come from “the vicinity of Forsyth, Montana, and Snow Creek” (Simpson, 1927, p. 1).

Invertebrate Paleontology

In 1902, in addition to collecting dinosaurian material, Brown and his field crews collected other fossils from outcrops of the Hell Creek Formation in the valley of Hell Creek and adjacent areas. New species, based on poorly preserved specimens of freshwater mussels (Unionoidea) from the Hell Creek Formation, were described by Whitfield (1903) as coming from Snow Creek (Fig. 11). Brown’s field notes concerning his mollusk and plant collections are woefully meager, but most of these fossils are identified with lot or locality labels that appear to help sort them logically into faunules or florules. The specimens in the 1902 collections can be assigned to Hell Creek lots 19 and 612 (Figs. 12A–12B). Whitfield (1903; Fig. 12C) reported these lots of fossils as

“being 120 feet [36.6 m] above the Pierre Shales.” Some snails in these lots were assigned to already named taxa of various geological ages, but they actually came from the Hockett locality in the Powder River drainage (Hartman, 1998). Other species, such as Corbicula subelliptica (Meek and Hayden, 1856), have not been found subsequently in the Hell Creek Formation. Whitfield (1903, p. 483) provided some sedimentological information, “[t]he fossils were found imbedded in a fine-grained gray clay, and are extremely friable and difficult of extraction, so much so, that it has been nearly impossible to free any of them from the matrix without an almost complete exfoliation and breaking up of the shell; only a few of them are sufficiently well preserved and perfect enough for illustration” (Figs. 12A–12B). This type of preservation is typical of shell accumulations found on the surface of well-lithified outcrops of Hell Creek Formation.

Through their later field seasons, Brown and his crews found significant beds of freshwater mussels, documented by large collections of well-preserved specimens. Whitfield’s 1907 paper on new and rephotographed species was based on specimens collected in 1906 (lots 709, 710, 718; localities L6876, L6874, L6877). These lots were collected from horizons 180 ft (54.9 m), 80 ft (24.4 m), and 300 ft (91.4 m) above the “Pierre Shales,”

Figure 12. (A) Exterior view of AMNHFI 35805 with a green diamond indicating that it is the holotype of Proparreysia verrucosiformis (Whitfield) figured by Whitfield (1903). (B) Interior view of AMNH-FI 35805 that was originally numbered 9625. The underlined “Arial italic” number 19 identifies the shell as part of Brown’s lot 19 (Locality L6875).

(C) Robert Whitfield (Merrill, 1924, p. 533, his figure 104) described and interpreted Barnum Brown’s collections of mollusks, primarily mussels from the Hell Creek Formation. In doing so, he established the foundation of its freshwater molluscan paleontology.

respectively, as reported in Whitfield (1907) and AMNH-IP records. Thus, Brown provided Whitfield and others with the opportunity to contemplate the stratigraphic distribution of mollusks in the Hell Creek Formation, if not their geographic or sedimentary contexts. Their biostratigraphy, however, remained unexamined until recently (Hartman, 1998).

Additional molluscan fossils were collected by Brown in 1909, lot 765, which AMNH-IP records show as coming from “120 feet [36.6 m] above Pierre Shales (locality L6898).” One additional labeled collection of mollusks exists (lot 757; locality L6899), but the time at which the specimens were collected and at what horizon are unknown. Two other localities with the existing lot numbers (709, 710) were reported from different lithologies, suggesting that different samples were taken from the same horizon or from nearby localities (localities L6900 and L6901, respectively). Brown also reported taxa of mollusks from the Hell Creek Formation not noted by Whitfield, presumably because the fossils were not actually collected. He (Brown, 1907, p. 834) stated that he “invariably found . . . waterworn fragments of bones and shells” in “river-sorted gravels” in sandstone intervals in the upper part of the formation and reported a locality near “Mr. Oscar Hunter’s fence near Crooked Creek (locality L1156).” Mollusks from the overlying Fort Union Formation are relatively uncommon. Brown’s experience in the “Fort Union? lignite beds” bears testament to their rarity with only “a few indeterminable casts of shells” being found in a lignite associated with chert (Brown, 1907, p. 835; locality L6180).

The significance of external sculptural patterns of unionoid shells was first recognized by Pilsbry (1904) immediately following the description of “Unios” by Whitfield. Pilsbry noted Whitfield’s tendency to correlate the new finds with the Laramie forms and stated that, “the radial V-like beak-sculpture of at least part of them shows that there is nothing in the supposed relationship of the Laramie forms to any surviving North American Unios. They belong to the Hyriinae of Simpson’s arrangement, and are only referable to Unio in a Lamarckian sense” (Pilsbry, 1904, p. 12). On the same page, Pilsbry went on to note that the name Unio browni Whitfield was preoccupied, and the new species “maybe called Parreysia barnumi,” after Barnum Brown, and included within the hyriniids.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, paleontologists used continental mollusks to interpret general time units, with the fossils thought of in the most quasi-evolutionary terms. Expressions such as “Laramie aspect,” “Fort Union fauna,” and “Wasatch fauna,” along with similar references to formations became confusing, de facto chronostratigraphic terms. White’s (1883; see Table DR1 in GSA Data Repository1) “tabular view” of North American continental fossil mollusks clearly delimited a Laramie Period fauna that included the majority of the continental mollusks then known for North America. In doing so, a

1GSA Data Repository Item 2014025, Tables DR1–DR4, is available at www .geosociety.org/pubs/ft2014.htm, or on request from editing@geosociety.org or Documents Secretary, GSA, P.O. Box 9140, Boulder, CO 80301-9140, USA.

tremendous thickness of western interior strata would be part of the discussion concerning the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. Whitfield (1903, 1907) described new species, identified additional taxa, and, also compared some fossils with more modern taxa, thus giving a sense of an evolutionary relationship between Cretaceous and modern unionids. Like many studies to follow, Whitfield’s study was local in scope, faunal in nature, and limited to comparative taxonomic diagnoses. As an AMNH paleontologist, however, he was the hands-on choice to examine the discoveries made by Brown in Hell Creek country. He was impressed by the morphologic similarity of the “Laramie” mussel species to those that lived in the inland waters of North America and made direct comparisons to the modern North American mussel fauna (see Table DR2 in the GSA Data Repository [see footnote 1]). Whitfield (1907, p. 624) stated, “Considering all the similarities between these Laramie fossils and their representative species in the Mississippi and Ohio water-sheds, I venture to state that these further western waters of the Laramie times were the original home of much of the Unio fauna of these more eastern recent localities.” Although of limited interest to many, this connection between Cretaceous “Laramie” and present mussel faunas would remain a consistent mindset among students of molluscan evolution and nomenclature (Watters, 2001; see Hartman and Bogan, 2009).

Although brief in length, Whitfield’s (1903, 1907) reports on Brown’s collections set the foundation for all later studies of Hell Creek continental mollusks. The fact is, however, few paleontologists explored continental mollusks for their potential to resolve problems of correlation, what would become known as Lazarus taxa, environmental landscape reconstruction, or their evolutionary patterns. Some aspects of their nomenclatorial complexity and comparisons to modern faunas were considered, with Whitfield (1903, 1907) making bold statements about the history of relationships that would be echoed in modern literature (Watters, 2001).

In 1914, C.F. Bowen of the USGS collected mollusks from the Hell Creek Formation in Garfield County (localities L2589–L2593) that were reported by Stanton (1916; Hartman, 1984). Although the strata and localities were not otherwise discussed, the area of the localities, Porcupine Dome southwest of Jordan, was included in Bowen’s (1915, plate X) geologic map and assigned to the Lance Formation. Unlike the fauna described by Whitfield, Bowen’s collection included species of Sphaerium as the only identifiable bivalves (Hartman, 1998).

In 1915 and 1916, A.J. Collier conducted field studies of the lignite resources of Sheridan, Daniels, Roosevelt, Valley, Phillips, and Blaine Counties, all north of the Missouri River in northeastern and north-central Montana (Collier, 1918, plate 1). He was assisted by W.T. Thom Jr., R.F. Baker, H.R. Bennett, E.T. Conant, and Barnum Brown, who collaborated with Collier in the field in 1916. In the present study area, mollusks were collected by Collier from Hell Creek strata in Valley County (localities L1794–L1797). Collier (1918) reported the faunules at these localities on the basis of identifications provided by J.B. Reeside Jr. (Fig. 13)

Figure 13. J.B. Reeside Jr. (1889–1958). In 1912, he began his career in the U.S. Geological Survey as a graduate student summer employee. All of the activities that he would pursue with professional vigor began with participation in field parties under the direction of C.J. Hares in the lignite fields of northwestern South Dakota and southwestern North Dakota. Reeside would soon be mentored by Stanton in the identification of fossils, replacing Stanton’s role after graduation (see also Dane, 1961).

and presented additional details on the lignite resources of part of this area in his report on the Scobey coal field (Collier, 1925). This report contains information relevant to the determination of the stratigraphic position of some of the molluscan localities noted previously (Hartman, 1984, 1998). The bivalve fauna represented by these collections is again relatively limited. Along with the sphaeriids, the faunules included species of Plesielliptio and a more highly sculptured species of Proparreysia from one locality (locality L1794).

Pilsbry (1921) followed his earlier interpretation with a paragraph-long assessment of the fossil record of North America, ending with the Laramie mussels:

The records for Triassic Unionidae are as yet few; but the wide separation of localities, the presence of several species and their considerable diversity in shape and sculpture in each area, may permit the inference that Triassic North America possessed a large and varied Naiad fauna of South American type, Hyriinae and Mutelidae. The next fauna of these mussels of which we have any definite knowledge is that of the Jurassic in Colorado and Wyoming. Here the South American types

have entirely disappeared, and in their place are distinctively Holarctic Unioninae, in which the beak sculpture when known is of the concentric type [footnote]. These were probably immigrants from Asia. Similar forms occur more abundantly in the Laramie. (Pilsbry, 1921, p. 31–32)

In the footnote, Pilsbry introduces Proparreysia for the “special group, near Parreysia or a subgenus thereof” that includes “[c]ertain Uniones described by Whitfield . . . from the Montana Laramie, [that] have sculpture recalling Diplodon, but more like the Asiatic Parreysia “ (Pilsbry, 1921, p. 32). Subsequently, a number of Hell Creek Formation species would be assigned to this new taxon.

Returning to northeastern Montana in 1921, Thom, Dobbin, and Stanton collected mollusks from the Hell Creek Formation in the northern part of the Jordan coal field in western Garfield County (localities L2396–L2399; see Hartman, 1984, 1998). In their report on the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in eastern Montana, Thom and Dobbin (1924) included their stratigraphic and general paleontological interpretations, along with concerns over reported occurrences of a shark and the “brackish” molluscan species Corbicula subelliptica in the upper beds of the formation. Problems typical of molluscan studies are that the specifics of the discoveries were never published, and only species with umbonal or dorsally directed postumbonal sculpture (e.g., Plesielliptio and Quadrula) were collected. No more highly sculptured species were included in their collection. During the same field season, the only bivalve collected by Frank Reeves was also a sphaeriid from the Hell Creek Formation in Fergus County (L2376). The first identifiable molluscan material from the Tullock Member of the Fort Union Formation was collected by Collier in 1927, in the first year of his study of the geology and coal resources of McCone County (Collier and Knechtel, 1939). Reeside (1928) reported a “Lance” age for a fossil assemblage including Unio gibbosoides Whitfield, Campeloma multilineata Meek and Hayden, and Tulotoma thompsoni White. This age assignment is in keeping with the then-current species diagnoses for these taxa (Hartman, 1998). Although where these fossils were found has not been specifically determined, all three taxa are very likely assignable to new Paleocene species on the basis of other collections known from the area (for the snails, see Hartman, 1984, 1998).

Paleobotany

Early studies of the Hell Creek Formation yielded only a few fossilized leaves, stems, and fruits. These were identified by Knowlton (Fig. 14A) and reported by Brown (Brown, 1907, p. 842). In 1908, Brown recovered a collection of leaves from “clays between middle and basal sandstones and in association with a skeleton of a dinosaur.” The leaves were identified by Knowlton (1909), who interpreted them as indicative of an Eocene age. These data did not play a major role in the then-current discussions of the “Laramie problem.” At that time, Calvert’s (1912) paleobotanical research on floras from other parts of the western interior was influential. Subsequently, in 1929, the appointment

of Roland Brown (Fig. 14B) to the staff of the USGS led to major and long-lasting changes in the pattern of paleobotanical research in the uppermost Cretaceous and Paleocene formations of northeastern Montana.

Geology, Stratigraphy, and the “Laramie Problem”

During most of the first two decades of the twentieth century, the Missouri Breaks and areas to the south were part of Dawson County. Garfield and McCone Counties, which were cut out of Dawson County, were not organized until 1919. Paleontological and geological research in the Missouri Breaks and adjacent areas in what was then Dawson County was advanced, apparently semi-independently, by Barnum Brown and, particularly after 1910, members of the USGS. At that time, a widely discussed research question was the determination of the position of what was then termed the “Cretaceous-Eocene boundary” in geological sections in the western interior. This complex question was often dubbed the “Laramie problem.”

The roots of the Laramie problem extend back into the nineteenth century with the pioneering studies of the western interior

(Waage, 1975). These included the early studies by Meek and Hayden (1862) and Hayden (1869) that differentiated between the underlying Cretaceous beds and overlying Tertiary lignites (Fig. 15) in the Great Lignite Basin (Williston Basin). Because of the similarity of certain continental fossil mollusks, from time to time in their earliest papers, Meek and Hayden confused the equivalency of Cretaceous strata (Judith River beds) with those of the “Lower Eocene” Fort Union Group. As their research matured, these uncertainties were removed in later papers.

In these early studies, the Laramie was often considered to be a unit including a conformable series of Cretaceous, brackish water grading into continental, often lignitic sediments (White, 1883). The top of the Laramie was placed at a hypothesized major unconformity marking a global interval of uplift, erosion, and/or lack of deposition of sediments separating the Cretaceous from the Eocene.

In a contribution to discussions of the Laramie problem, Stanton and Knowlton (1897) reviewed the invertebrate (molluscan) fauna and flora of the “Ceratops” beds, locality by locality, throughout Wyoming and in parts of Colorado and Utah. They noted, “[u]ntil a few years ago it was the custom to include in

Figure 14. (A) Frank Knowlton (1860–1926). Knowlton was a paleobotanist on the staff of the U.S. Geological Survey. He was a friend and scientific adversary of T.W. Stanton in their differences on interpretation of the ages of the flora and fauna, respectively, across the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary (see Dall, 1911). (Source: U.S. Geological Survey Photo Archives, Knowlton, F.H., Geologist, no. 434 portrait, 25 June 1889.) (B) Roland W. Brown, whose paleobotanical research in the western interior played significant roles in documenting Cretaceous and Paleogene floras, as well as in the debates surrounding recognition of the Cretaceous-Paleogene boundary. (Photograph from Mamay, 1963.)

Figure 15. An early interpretation of the geology of Garfield County by F.V. Hayden (1869) based on his mapping of the area with U.S. Army Corps of Topographical Engineers.

the Laramie all of the beds between the Fox Hills and Wasatch formations” (Stanton and Knowlton, 1897, p. 155). In their analyses, individual localities were local lithostratigraphic sections they had visited, where fossils were identified and compared by assemblage presence (or absence) in order to draw conclusions concerning biostratigraphic correlations. Succinctly, they stated that the Laramie and allied formations, “first known as the Lignite series, included the coal-bearing strata of the Upper Cretaceous with the lower Tertiary or Fort Union strata and was all regarded as Tertiary in age. Later, the Laramie was differentiated by King as the uppermost division of the conformable Cretaceous series, and the Fort Union group ultimately associated with the lower Tertiary, although still regarded by some as belonging to the Laramie series. The Laramie as thus characterized was supposed to be very sharply circumscribed” (Stanton and Knowlton, 1897, p. 127–128).

In tracing the course of stratigraphic research in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it is important to remember that, although practiced in Europe, American geologists did not consistently make a distinction between lithostratigraphic and chronostratigraphic units. For example, Wasatch could refer to a lithostratigraphic unit, the Wasatch Formation, or a chronostratigraphic unit, the “early Eocene” (Fig. 16). As used in these early studies, “early Eocene” was approximately a temporal equivalent of the Paleocene Epoch, which was not widely recognized by stratigraphers until decades later. Wasatch was not correlative with the early Eocene or Wasatchian North American land mammal age as currently recognized. Additionally, there were disagreements about the proper criteria for defining and recognizing the chronostratigraphic boundary between the Cretaceous and Eocene. Some workers focused on recognition of a conform-

able sequence of strata capped by a hypothetical widespread unconformity marking the boundary (e.g., Cross, 1909). Others cited paleontological evidence and interpretations of the age of strata as the bases for their interpretations (see Hartman, 2002). Although attempts at sweeping generalizations were made, at the beginning of the twentieth century, the geology of only a few areas in the western interior had been studied in detail. This would change, particularly as the results of an increasing number of field studies by the USGS became available.

A full review of the history of discussion and dispute over the Laramie problem is well beyond the scope of this paper. Here, we focus on the impact of the paleontological and geological data that came from the work of Brown and members of the USGS on Cretaceous and Tertiary sections in what was then Dawson County and adjacent areas. The first publications based on the collections that Brown made in 1902 presented systematic descriptions and analyses. Brown (1905b) described two new species of Champsosaurus, Champsosaurus laramiensis and Champsosaurus ambulator. The partial skeletons that served as their type specimens came from sites ~100 yards (91.4 m) apart horizontally and at stratigraphic levels differing by only 6 ft (0.91 m) in the “lower strata of lignite, above the Ceratops beds.” These lignitic strata were described as part of the “Laramie Cretaceous exposures on Hell Creek” (Brown, 1905b, p. 3).

Whitfield’s systematic studies of the molluscan faunas sampled by Brown in 1902 (Whitfield, 1903) and 1906 (Whitfield, 1907) have already been discussed. Very probably all these fossil mussels came from what is now recognized as the Hell Creek Formation and are of Cretaceous age. Molluscan material is rarely preserved in strata in the lower part of the Tullock Member. In neither of his publications did Whitfield (1903, 1907) consider the relationships of the “Laramie” (Cretaceous) Hell Creek Formation molluscan fauna to that of the Cretaceous “Ceratops beds” (Lance Formation) of Wyoming. On one hand, his failure to discuss this topic seems strange, as discussions of the Laramie problem had been raging since the late 1800s. The Hell Creek molluscan fauna would have provided a perfect segue into the fray. Whitfield, however, may have felt out of his element. He had not been part of arguments over the Laramie problem, and, at the time of writing his papers, Brown had yet to publish his views on the stratigraphy of the formation.

Barnum Brown’s study of the Hell Creek beds (Brown, 1907) provided a stratigraphic analysis of the geological section exposed along Hell Creek, its tributaries, and adjacent areas in the Missouri Breaks. As advertised in the subtitle of this paper, he also contributed to discussions of the Laramie problem with considerations of “their relation to contiguous deposits, with faunal and floral lists and a discussion of their correlation.” Brown made reference to his observations in eastern Wyoming of the “Converse County beds of Wyoming” or “Ceratops beds of Converse County, Wyoming,” now recognized as the Lance Formation. His introduction to these beds came in 1895 when he was a student at the University of Kansas and collected in this area on a summer field trip directed by S.W. Williston (Kohl et al., 2004;

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

Stella istui sohvassa ja teki nuoranpätkään merimiehensolmuja.

Hän katsahti äkkiä puhekumppaniinsa:

"Kuvittelen, että usko on paljon syvempää."

Ashurst tunsi taaskin halua näyttää ylemmyyttään:

"Kuvittelette niin, mutta tarve saada 'verta verrasta' on syvimmällä meissä kaikissa. On sangen vaikea tunkeutua sen tunteen pohjaan saakka."

Tyttö rypisti hämillään kulmakarvojaan.

"Pelkään pahoin, etten ymmärrä teitä."

Ashurst jatkoi itsepintaisesti:

"Ajatelkaahan, eivätkö uskonnollisimmat ihmiset ole löydettävissä juuri niiden joukosta, joille tämä elämä ei ole antanut kaikkea, mitä he ovat siltä pyytäneet? Uskon hyvyyden, koska itse asiassa on hyvä olla hyvä."

"Uskotte siis hyvyyden?"

Kuinka kaunis Stella olikaan juuri nyt — oli helppo olla hyvä hänelle!

Ja Ashurst nyökkäsi päätään ja sanoi:

"Kuulkaahan, tahdotteko näyttää minulle, kuinka tuollainen solmu tehdään?"

Kun tytön sormet koskettivat Ashurstin sormia heidän käsitellessään yhdessä langanpätkää, nuorukainen tunsi olevansa rauhoittunut ja onnellinen. Ja mennessään levolle hän koetti

tahallaan kiinnittää ajatuksiaan Stellaan, kietoa itsensä tytön kauniiseen, viileään, sisarelliseen ilmapiiriin kuin jonkinlaiseen suojelevaan viittaan.

Seuraavana aamuna hän kuuli, että oli päätetty lähteä junalla

Totnesiin ja syödä välipalaa Berry Pomeroy Castlessa. Yhäti tietoisesti etsien menneisyyden unohdusta hän istuutui muun seuran mukana vaunuihin, Hallidayn viereen, selkä hevosiin päin. Ja heidän ajaessa rantatietä hän näki äkkiä lähellä mutkaa, josta tie kääntyi asemalle, sellaista mikä oli saada hänen sydämensä seisahtumaan.

Megan — Megan itse! — käveli vähän matkan päässä kulkevaa jalkapolkua, yllään vanha hame ja pusero ja päässä pyöreä lakki, katsellen ohikulkevia kasvoihin. Vaistomaisesti Ashurst vei kätensä kasvoilleen peittääkseen ne ja perustellen liikettään sillä, että oli pyyhkivinään tomua silmistään. Mutta sormiensa lomitse hän saattoi yhä nähdä tytön, joka ei kävellyt entiseen vapaaseen maalaistapaansa, vaan epäröivän, hylätyn, säälittävän näköisenä, kuin isännästään eksynyt pieni koira, joka ei tiedä, onko sen juostava eteenpäin vai taaksepäin vai minne. Kuinka tyttö oli tullut tänne asti? Minkä tekosyyn hän oli keksinyt matkalleen? Mitä hän toivoi saavuttavansa matkallaan? Joka kierroksella, jonka pyörät pyörähtivät kuljettaen Ashurstia kauemmas tytöstä, hänen sydämensä nousi yhä rajummin vastarintaan, huusi hänelle, että hänen on pysähdytettävä vaunut, laskeuduttava maahan ja mentävä tytön luo. Kun vaunut kääntyivät rautatieaseman tienmutkassa, ei hän voinut enää hillitä itseään, vaan avasi vaununoven ja mutisi: "Olen unohtanut jotakin. Jatkakaa matkaanne — älkää odottako minua. Tulen seuraavassa junassa. Yhdytän teidät linnan luona."

Hän hyppäsi maahan, kompastui, kääntyi, pääsi taas jaloilleen ja käveli edelleen vaunujen vieriessä ihmettelevät Hallidayt mukanaan edelleen.