Policy

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://textbookfull.com/product/the-nigerian-rice-economy-policy-options-for-transfor ming-production-marketing-and-trade-kwabena-gyimah-brempong/

More products digital (pdf, epub, mobi) instant download maybe you interests ...

Micro Irrigation Engineering for Horticultural Crops Policy Options Scheduling and Design 1st Edition Goyal

https://textbookfull.com/product/micro-irrigation-engineeringfor-horticultural-crops-policy-options-scheduling-and-design-1stedition-goyal/

Marketing Database Analytics Transforming Data for Competitive Advantage 1st Edition Andrew D. Banasiewicz

https://textbookfull.com/product/marketing-database-analyticstransforming-data-for-competitive-advantage-1st-edition-andrew-dbanasiewicz/

Climate Change and Future Rice Production in India A Cross Country Study of Major Rice Growing States of India K. Palanisami

https://textbookfull.com/product/climate-change-and-future-riceproduction-in-india-a-cross-country-study-of-major-rice-growingstates-of-india-k-palanisami/

Using R for Trade Policy Analysis R Codes for the UNCTAD and WTO Practical Guide Massimiliano Porto

https://textbookfull.com/product/using-r-for-trade-policyanalysis-r-codes-for-the-unctad-and-wto-practical-guidemassimiliano-porto/

The Political Economy of Normative Trade Power Europe

Arlo Poletti

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-political-economy-ofnormative-trade-power-europe-arlo-poletti/

New Trends in Process Control and Production Management: Proceedings of the International Conference on Marketing Management, Trade, Financial and ... Slovak Republic and Tarnobrzeg, Poland 1st Edition

Bohuslava Mihal■ová https://textbookfull.com/product/new-trends-in-process-controland-production-management-proceedings-of-the-internationalconference-on-marketing-management-trade-financial-and-slovakrepublic-and-tarnobrzeg-poland-1st-editio/

The Roman Agricultural Economy Organization Investment and Production 1st Edition Alan Bowman

https://textbookfull.com/product/the-roman-agricultural-economyorganization-investment-and-production-1st-edition-alan-bowman/

Loss and Damage from Climate Change Concepts Methods and Policy Options Reinhard Mechler

https://textbookfull.com/product/loss-and-damage-from-climatechange-concepts-methods-and-policy-options-reinhard-mechler/

Screen Media for Arab and European Children Policy and Production Encounters in the Multiplatform Era Naomi Sakr

https://textbookfull.com/product/screen-media-for-arab-andeuropean-children-policy-and-production-encounters-in-themultiplatform-era-naomi-sakr/

THE NIGERIAN RICE ECONOMY

POLICY OPTIONS FOR TRANSFORMING PRODUCTION, MARKETING, AND TRADE

EDITED BY KWABENA GYIMAH-BREMPONG, MICHAEL JOHNSON, AND HIROYUKI

The Nigerian Rice Economy

IIFPRI

Thi book is published by ch e Universiry of Perrnsylvania Press (U PP ) on behn lf of the Internacional Food Policy Resea rch lnsti rure (IFP RI) a pare of a joint-publicacion series Books in the series prese nt research on food securi t y a nd eco no mic devdopmenc with the aim of reducing poverty and elimin at in g hunger a nd malnua·icion in developingnacions. They a re the produce ofpeer-reviewed IFPRI research and a re elected by murual agreement between th e parties for publication under the joint IFPRI-UPP imprint.

The Nigerian Rice Economy

Policy Options for Transforming Production, Marketing, and Trade

Edited by Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima

Publi sh ed for the International Fo od Policy Research Institute

PENN

University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia

Copyright © 2016 International Food Policy Research Institute.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Any opinions stated herein are those of the author( s) and are not necessarily representative of or endorsed by the International Food Policy Research Institute.

Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112 www.upenn.edu/ pennpress

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN 978-0-8122-4895-l

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima Chapter 2

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong and Oluyemisi Kuku-Shittu

Chapter

Hiroyuki Takeshima and Oladele Samuel Bakare Chapter

Hiroyuki Takeshima

Michael Johnson and Akeem Ajibola

Paul A . Dorosh and Mehrab Malek

Chapter 8 Economywide Effects and Implications of Alternative Policies

Xinshen Diao, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima

Chapter 9 Transforming the Rice Sector

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima

Appendix A A Brief Chronology of Nigeria's Political History 211

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima

Appendix B The Linear Expenditure System Model

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong and Oluyemisi Kuku-Shiccu

Appendix C Additional Tables to Chapter 3

Hiroyuki Takeshima and Oladele Samuel Bakare

Appendix D Supply Response Analysis

Hiroyuki Takeshima Appendix E

Appendix F A Stylized Rice Tariff Model

Paul A. Dorosh and Mehrab Malek

4.7 Number of varieties released in Nigeria and Asia by National Agricultural Research Institutes and other sources

4.8 Annual investment in irrigation in selected countries and Nigeria

4.9 Share of irrigated area among all rice areas in selected countries

4.10 Growth in nominal rate of assistance to agriculture, selected West African countries, 1960-2004

4.11 Urea-to-paddy (kg) price ratio in selected countries and Nigeria

5.1

5.2 Key indicators of efficiency and profitability of smallversus large-scale rice milling

6.1 Effect of policies on national output by types of miller and rice (million MT)

6.2 Effect of policies on shares in national output by types of miller and rice (percent of total rice output)

6.3 Effect of policies on zonal output by types of rice

6.4 Effect of policies on change in employment by miller and rice type (percent change from base)

6.5 Effect of policies on changes in employment shares by miller type (as percent of national employment in the rice milling industry)

6.6 Effect of different miller strategies on total output by miller and rice type (percent change from base)

6.7 Effect of different miller strategies on total output by zone (percent change from base)

6.8 Effect of different miller strategies on total employment in the milling industry by miller and rice type (percent change from base total)

7.1 Rice imports by Nigeria and world rice exports to Nigeria, 2008-2012

7.2

7.3

7.4 Import prices, import tariffs, exchange-rate premiums, and wholesale prices of rice, 1980-2013

7.5 Nigeria's rice imports, tariffs, and market prices, 2008-2013 173

8.1 Assumptions and targets of alternative scenarios applied in the Nigerian economywide multimarket model simulations 187

A.I A brief chronology of Nigeria's political history, 1960-2013 211

B.la Demand for major commodities by zone (North Central and North East) 217

B.lb Demand for major commodities by zone (North West and South East) 218

B.lc Demand for major commodities by zone (South South and South West) 219

B.2 Own- and cross-price elasticities of demand for food in Nigeria 220

B.3 Estimates of own-price elasticity 221

B.4 Average and marginal budget shares and income elasticities 222

B.5 Sample statistics of consumption (national, urban, and rural) 223

C.l Major soils and rice ecologies 225

C.2 Major known rice pests in Nigeria 226

C.3 Major pathogens causing diseases of rice in Nigeria 226

C.4 Some weed species among lowland rice in Nigeria 227

C.5 Weed species status at some lowland experimental sites of the National Cereals Research Institute, 2008 and 2009 228

D.l Rice production and irrigated rice area responses in Nigeria (pseudopanel double-hurdle model/Tobit) 232

D.2 Reported production costs for rice (US$ per hectare) 234

D.3 Rice research expenditure in selected countries 235

D.4 Producer price of rice and fertilizer price in selected countries and Nigeria 236

E.l Annotations and symbols for rice milling model equation ( 1) 240

E.2 Milling output by miller sector and zones 245

E.3 Use of superior and common paddy varieties by major zone in the baseline scenario 246

E.4 Estimation of average transportation costs from Lagos port 248

E.5 Average transportation and marketing costs between and within states, respectively (naira/MT) 249

5.4 Comparison of the rice price structures in Nigeria, Thailand, and Bangladesh 123

5.5 Evolution of modern rice mills, yields, and net exports in India 133

7.1 Rice imports by Nigeria and world rice exports to Nigeria, 2008-2012 161

7.2 Rice imports by Nigeria and world rice exports to Nigeria by country, 2010 and 2011 162

7.3 Benin's total rice trade and rice exports to Nigeria, 2006-2011 163

7.4 Rice imports by source of data

7.5 Nigeria's nominal and real exchange rates, 1990-2013

7.6 Nigeria's domestic and import parity rice prices and rice imports , 2005-2013

7.7 Nigeria's monthly rice imports, COMTRADE and NBS/ customs data, 2010-2013 175

8.1

8.2

8.3

8.4

8.5

E.1 Baseline data of average state prices for paddy, local, and imported rice in Nigeria, 2012

E.2

F.l

ABS

ADP

AfRGM

ATA

C&F

CGE

COMTRADE

Acronyms and Abbreviations

average budget share(s)

Agricultural Development Project

African rice gall midge

Agricultural Transformation Agenda

cost and freight

computable general equilibrium

United Nations Commodity Trade Statistics Database

CPI consumer price index EA

enumeration area

economywide multimarket

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

statistical databas e of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations

Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development

free on board

gross domestic product

Growth Enhancement Support program

International Food Policy Research Institute

International Institute of Tropical Agriculture

International Monetary Fund

International Rice Research Institute

LES

Linear Expenditure System

LGA

LSMS-ISA

MBS

MRM(s)

MT

NAERLS

NARI(s)

NBS

NCRI

NEEDS

NERICA

NRA

NSS

O&M

OFN

ppm

PPP

PrOpCom

R&D

RMM

RYMV

S&T

SAPs

SCPZ

SSA

USDA

WARDA

WDI

local government area

Living Standards Measurement Study-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture

marginal budget share(s)

modern rice mill(s)

metric tons

National Agricultural Extension and Research Liaison Services

national agricultural research institute(s)

National Bureau of Statistics

National Cereals Research Institute

National Economic Empowerment and Development Strategy

New Rice for Africa

Nominal Rate of Assistance

National Seed Service operations and maintenance

Operation Feed the Nation

parts per million

purchasing power parity

Promoting Pro-poor Opportunities in service and Commodity Markets

research and development

rice milling model

rice yellow mottle virus

science and technology

structural adjustment programs

staple crop processing zone

Africa south of the Sahara

United States Department of Agriculture

West Africa Rice Development Association (now Africa Rice Center)

World Development Indicators of the World Bank

Foreword

In recent decades, Africa south of the Sahara has become increasingly reliant on rice imports. This is the result of globalization, urbanization, and diet change, as well as slow transformation and modernization of domestic agricultural sectors in many parts of the region. Because rice is an important source of diet and income, the increase in importation has become a symbol of the food security challenges facing many African countries. Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with the largest economy. It also has the largest rice production area in Africa, comparable in size and diversity to many Asian countries. However, despite ever-growing demand and a long history of government efforts, its rice sector remains vastly underdeveloped, and the country is one of the largest rice importers in the world.

The Nigerian Rice Economy assesses the policy challenges and opportunities for transforming and expanding Nigeria's rice economy. The authors discuss the rice economy's evolution, structure, and agroecological constraints, as well as policy issues related to consumption, production, milling, and trade, each substantiated by rigorous quantitative analyses. The book provides indepth insights into focused areas, including the effects of rice price policy on distribution, production technology constraints, optimal milling sector structure, trade policy effectiveness, and economywide implications of key rice sector interventions. The authors also suggest options to improve the rice sector.

Achieving rice self-sufficiency in the short term, as envisaged by the Nigerian government, may be too costly in terms of required resources and social costs. Price and trade policies alone may be ineffective in inducing private-sector responses, as these policies are often stymied by limited supply responses, cross-border leakages, limited market integration, and low

substitutability of imported rice with local rice. High rice prices can rather significantly hurt the majority oflow-income consumers. But policymakers can transform the rice sector, and there is room for improved policy. Production technologies and market infrastructure improvement are at the center of an effective rice development strategy that includes reducing production costs, raising sector competitiveness, and enhancing the biophysical potential of Nigerian rice.

Shenggen Fan Director General, IFPRI

Acknowledgments

This bookis the result of the collaboration and act ive upport of many individual s on cwo continent -Africa and North America- either in reviewing previous d cafts, in sharing input during·the presencacion of preliminary findings at various venues, or in encouraging the completion of the book. For this, we are grateful.

In particular, we wish to thank various Nigerian officials, including the minister of agriculture and rural development, Dr. Akinwumi Adesina; Dr. Olumuyiwa Osiname, the chair of the Rice Value Chain Development Team of the Federal Ministry of Agricultural and Rural Development (FMARD); and Dr. Hussaini, director of the Planning, Research and Statistics Division ofFMARD, for providing important insights into Nigerian conditions. We also greatly appreciate the staff from Agricultural Development Projects, Fadama Development Offices, the National Bureau of Statistics, and the Nigeria Customs Office for providing various secondary information and facilitating authors' fieldwork.

We are indebted to the intellectual support and guidance from various other senior researchers at the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), includingJawoo Koo, Bart Minten, Tewodaj Mogues, and Ephraim Nkonya. We are grateful to Gershon Feder, the chair of the IFPRI Publication Review Committee, for providing invaluable suggestions and constructive criticisms along various stages of the writing of this book. We are also indebted to Marco Wopereis (Africa Rice Center) and Randy Barker for their guidance in identifying experts in Nigerian agronomy, as well as for sharing important insights into general rice-sector issues. We are also indebted to two anonymous reviewers , as their invaluable inputs greatly improved the manuscript.

We are particularly grateful to the excellent research support of Angga Pradesha and Amarachi Utah at IFPRI headquarters in Washington, DC, and

oflan Masias and Hyacinth Edeh, both at IFPRI's Nigeria Strategy Support Program (NSSP) Abuja office. We are also grateful for the efficient administrative and logistical support provided to us by staff in Abuja at both IFPRI and its host institution, the International Fertilizer Development Institute. They made sure our travel plans and appointments occurred in a timely, safe, and secure fashion.

The feedback from participants at various venues in Africa proved especially valuable. Among these are an IFPRI-NSSP conference in Abuja, Nigeria (2013); a seminar at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture campus in Ibadan, Nigeria (2013); a seminar at the Institute of Food Security in Makurdi, Nigeria (2013); a presentation at the Third Africa Rice Congress in Yaounde (2013); and the IFPRI Dissemination Workshop in Accra, Ghana (2015).

The completion of the book would not have been possible without the financial support of a number of donors. Among these, core support was provided by the Nigerian mission of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID /Nigeria). Other financial support was indirectly provided by the Policies, Institutions and Markets research program of CGIAR and the Japanese government through its bilateral funding to IFPRI. A number of individuals among the donor community in Nigeria also deserve mention, as they provided both technical and strategic support along the way These include Howard Batson and Alefia Merchant ofUSAID / Nigeria, and Atsuko Toda of the Abuja office of the International Fund for Agricultural Development.

Finally, we would like to thank the director general ofIFPRI, Dr. Shenggen Fan, for providing continuous encouragement toward the completion of this book.

The views expressed in this book do not necessarily reflect the views of IFPRI, the National Cereals Research Institute, or the donors. The authors are solely responsible for all errors.

RICE IN THE NIGERIAN ECONOMY AND AGRICULTURAL POLICIES

Kwabena Gyimah-Brempong, Michael Johnson, and Hiroyuki Takeshima

0ver the pa t few decades, rice has become one of the .leading food staples in Nigeria, surpas ing ca sava in food expenditure . Throughout this period, consumption has increased faster than production, resulting in a growing dependency on imports. By 2014, about half of the rice consumed in Nigeria was imported. As the most populous country in Africa south of the Sahara (SSA), Nigeria has quickly become the leading importer of rice on the continent and, more recently, in the world.

This growing dependence on rice imports is a major concern of Nigeria's government, and since the early 1980s numerous programs have been implemented to encourage domestic rice production and achieve rice self-sufficiency (or at least to reduce the growth in imports). In particular, rice featured prominently in the Agricultural Transformation Agenda (ATA), which had guided the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development (FMARD) in Nigeria under the administration of President GoodluckJonathan as the central agenda of the country's agricultural policy.1 The ATA included major investments and programs related to rice production, processing, and marketing. Trade policies (import tariffs and even import bans) have also been used in an attempt to slow the growth in imports, with import tariffs on milled rice increasing to 110 percent beginning in 2013.

In spite of these policies, the Nigerian rice sector has yet to be transformed into a more productive one that can compete with foreign imports. This situation is not unique to Nigeria and applies to the rest of SSA, where the sector's slow growth has puzzled many international donors and research communities (Otsuka and Larson 2012). As one of the largest producers and consumers of rice in SSA, Nigeria has been at the center of this puzzle.

The principal objective of this book is to review and assess the potential for Nigeria to transform its domestic rice sector to become competitive with

I This book was written when Nigeria was under President Jonathan's administration. Throughout the book, rice policies or the policy framework mentioned are those that had been implemented during this administration, unless otherwise specified.

imports . We assess the policy alternatives for bringing about this transformation and also briefly discuss the opportunity costs of achieving such competitiveness. In particular, three key strategies that have recently been adopted by the government are examined in more detail with regard to their potential long-run welfare implications for transforming the rice economy and making domestic brands competitive with imports:

1. Introducing public-sector interventions to stimulate paddy production through the dissemination and adoption of better seeds and other modern inputs.

2. Improving the postharvest processing and milling sectors to promote premium and high-quality local brands of rice.

3. Introducing import tariffs to help protect the domestic rice sector.

This chapter assists readers to gain a better understanding of how Nigeria arrived at its recent policy framework for agriculture and the rice sector in particular. The chapter first describes the evolution of rice imports and the growing imbalance between production and consumption. It then presents a brief overview of Nigeria's economy and recent history, the basic structure of the agricultural sector, and a summary of recent key rice policies. Finally, the chapter describes the key set of questions asked in this book and how each chapter addresses them from different perspectives on the rice sector in Nigeria.

Nigeria's Rice Trade in a Global Context

Nigeria has become the world's biggest importer of rice within the last ten years. As Table 1.1 shows, Nigeria's share of global rice imports has risen from 7 percent in the early years of the 21st century to 8.2 percent over the most recent five years for which data are available (2008-2012). Among the top rice importers, Nigeria is followed closely by the Philippines, Iran, Indonesia, and the European Union. The bulk of rice imports to Nigeria come from Thailand, Vietnam, and India, who together supply about 60 percent of the rice traded in global markets.

The reliance on global rice markets raises serious concerns for policy with regard to ensuring food security and maintaining a healthy balance of the country's foreign-exchange reserves. This is especially true when faced with a dramatic rise in prices, as occurred during the recent 2008 food crisis. For rice in particular, prices rose by about 255 percent between 2007 and 2008, even higher than in the last major food crisis in 1974, when they increased by 200 percent (Headey and Fan 2008).

Source: United States Department ofAgriculture international database (USDA 2013)

As in 1974, the experience of the 2008 food crisis led many governments of net importing countries in the developing world to reduce their vulnerability to price shocks by striving for self-sufficiency in rice production. Nigeria is no exception. In the aftermath of the most recent crisis and rising consumer preference for imported rice, the Nigerian government has set a goal of making the country self-sufficient in rice production. The perception among Nigerian policymakers is that the increasing trend of rice imports is fiscally and politically unsustainable, as it threatens the country's food security by displacing local production, draining scarce foreign-exchange reserves, and making the country a hostage to any volatility of supply in global markets (Adesina 2012).

Despite this, domestic demand for rice has continued to grow at an even faster pace in Nigeria and elsewhere in Africa since the global food crisis of 2008. As Table 1.2 shows , rice consumption in Nigeria increased by about 8.4 percent per year in the most recent period (2010 to 2012) compared to 5.3 percent for the rest of SSA. Lower global rice prices, increased household incomes, and continuing growth in urban populations may explain this most recent upturn in the trend in rice imports.

Another factor explaining the increased demand has been a preference for imported rice among urban consumers due to its higher quality with respect to swelling capacity, taste, and grain shape and cleanliness (Bamidele, Abayomi, and Esther 2010; Lanc;on et al. 20036). Local rice, on the other hand, is often broken, not polished, and contains scones and other debris. Finally, the

TABLE 1.2 Average annual volume and growth rates of milled rice supply in Nigeria and the rest of West Africa and Africa south of the Sahara (SSA), 1980-2013

Source: United States Department ofAgriculture international database (USDA 2013).

removal of input subsidies, price supports, and protective import barriers in the aftermath of structural adjustment programs of the 1980s and 1990s also played a key role by exposing the lack of competitiveness oflocal rice production in terms of technologies, costs, and milling efficiencies relative to imports (Moseley, Carney, and Becker 2010).

As the demand has accelerated, no country in the region has been able to match this through domestic production. In Nigeria, imports have increased the fastest, at 20 percent per year on average during the last three years for which data are available, 2010-2012 (Table 1.2).2 Local production has not grown as fast. In Nigeria, local rice production grew by only about 2 percent per year over the last three years. This is much lower than the average 5.4 percent in the rest of the countries in West Africa. 3

2 While it is possible that some imports to Nigeria may be reexported to neighboring countries such as Niger, Chad, and Cameroon, this is difficult to confirm given scanty data on informal cross-border trade. But we expect these shares to be small given the sheer size of the Nigerian market relative to these other countries. We note that there is a difference between market demand and consumption, as the latter includes both market demand and subsistence production for own-consumption.

3 In this book, West Africa comprises Benin, Burkina Faso, Cote d'Ivoire, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Togo.

In an effort to reverse the current trend of rising imports, the Nigerian government recently introduced a number of key policies and investment strategies. These include the provision of improved seeds, subsidized fertilizer, mechanization services, and incentives for private-sector investments in irrigation. At the macro level, rice import tariffs were increased in order to discourage imports and encourage domestic production. Improvements in paddy production, rice processing, and marketing have also been encouraged with the support of public-sector reforms and investments.

The recent policy reforms have included deregulating seed and fertilizer markets and establishing private-sector marketing corporations to help coordinate supply and demand and set grades and standards for many agricultural commodities. Physical investments have also been made to establish staple crop processing zones (SCPZs) that have been intended to encourage the clustering of food-processing industries, including rice milling, in proximity to raw materials and end markets.

A Brief Overview of Nigeria's Economy and History

The Nigerian economy is the largest in Africa, having recently overtaken South Africa after rebasing its gross domestic product (GDP) in 2014. It makes up twothirds of all economic activity in West Africa and one-fifth in SSA. In 2012, Nigeria's GDP was $180.9 billion in constant 2005 US dollars (Table 1.3). The country also has the largest population in the region. For every two people living in West Africa or for every five people in SSA, one is a Nigerian.

In recent years, the country has continued to experience steady and positive economic growth and is becoming one of the fastest growing economies in the region. As Table 1.3 shows, GDP growth rates have averaged about 7 percent or more per year, and per capita growth has been about 4 percent over the last decade, faster overall than the average per capita GDP growth for West Africa or SSA (Table 1.4).

The irony for Nigeria is that despite the positive economic growth, it remains-due to its sheer size and high poverty rate-home to most of the poor and hungry living in West Africa. It has one of the highest incidences of poverty, with 62 percent of the population living on less than $1.25 (purchasing power parity [PPP]) a day in 2010. In contrast, Mali, which has a lower per capita GDP, reported a poverty rate of 50.4 percent in 2010. In Ghana, the poverty rate was less than half the rate in Nigeria during the same year (Table 1.4).

In addition to poverty, the prevalence of hunger is also high. The proportion of underweight children of less than five years of age in Nigeria fell only

TABLE 1.3 Selected socioeconomic indicators for Nigeria, 1995-2012

Select economic indicators GDP (constant 2005

billion US$)

(constant 2005 US$)

(constant 2005 billion US$)

Select social indicators

five (%JC

Source: World Development Indicators of the World Bank (2014).

Notes: GDP =Gross domestic product; NA =not available; PPP =purchasing power parity. •About 90 percentof the value of industry is from thepetroleum sector. bA composite index calculated by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) using three measures: the prevalence of undernourished children, prevalence of adult undernutrition, and child mortality rate See von Grebmer et al. (2013) for more details on this index cror prevalence of undernourished children, this is 1993-1997, 1998-2002, 2003-2007, and 2008-2012

TABLE 1.4 West Africa selected indicators, 2012

Source: World Bank (2014).

Note: GDP= gross domestic product; NA = not available; PPP"' purchasing power parity;SSA"'Africa south of lhe 'Sahara. , , ) For 2001 ,the ratios for Cole d'Ivoire arefor 2002,for Ghana 1998, a·nd for Nigeria2004;(2) For 2010,the ratios for Coted'Ivoire are for 2008,forGhana2006,and for Senegal 2011. bFromvon Grebmer et al. (2013),variousyears:for2000, average between 1998 and 2002; for 2010, average between2008 and 2012.

marginally between 2000 and 2010, from 24.7 percent to 24.2, respectively. The comparable rates for Mali and Ghana dropped sharply during the same period (Table 1.4).

The structure of the Nigerian economy, its institutions and macroeconomy, and sociopolitical history can all partially explain the dichotomy between positive economic growth with no change in the incidences of poverty and hunger. Relatively low investment in and poor performance of agriculture may have led to such a dichotomy. The sector not only contributes the most to GDP, it employs over two-thirds of the working population in Nigeria, and therefore it is of critical importance for food security, rural incomes, and poverty reduction.

Research has shown that many African countries that rely heavily on agriculture for their GDP have experienced more equitable growth and poverty reduction whenever overall economic growth was agriculture led (Diao et al. 2010). In the case of Nigeria, a study using macroeconomic modeling underlines this finding by showing how potentially larger gains in incomes and poverty reduction are likely when fiscal policies are targeted at stimulating growth in the agricultural sector (Akanbi and Du Toit 2011). Until recently, however, Nigeria's economy relied heavily on petroleum production and exports to generate growth.

Based on the most recent estimates from the World Bank's World Development Indicators (WDI) database, the agricultural sector appears to have grown quite rapidly since the beginning of the 21st century. As shown in Table 1.4, the sector grew at an average annual rate of 6.4 percent between 2002 and 2012. 4 However, the growth has been driven mainly by an expansion in area planted to staple crops, as yields have changed little over the same . d 5 per10 .

Moreover, growth in the agricultural sector has not been a pro-poor oneit has had little effect on the welfare of a majority of the poor in Nigeria because the agricultural subsector(s) driving the growth may have weaker linkages with the households and locations most affected by poverty, such as those that are net purchasers of food (Diao et al. 2010). Additionally,

4 Recent estimates by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), which is the principal agency oversee in g the natio nnl statistics o f Nige ria, report a 4.5 and 5.1 percenc growth in constant 1990 na ira terms during the second llJl d t hird q ua rters of 2013 , respectivel y (Nige ria, NBS 2013b). Thus , the growth has somewhat slowed down in 2013.

S For rice , foe example, average yields have actually declined over time in Nigeria from a h igh of2.1 metr ic tons (MT)/ha in the 1980s to 1.5 MT/ha afte r the turn of rhc century (ba sed on FAO2014).

insufficient investments have been made into basic infrastructure and social services (such as education and health) in rural areas in tandem with che growth in the agriculture sector (see Dim and Ezenekwe 2013). Evidently the many years of neglect of agriculture, basic infrastructure, institutions, and services in the past have taken a toll. The neglect is visible in the state of disrepair, unreliability, and inefficiencies of basic infrastructure that exists in many parts of the country.

A key factor chat has challenged Nigeria's ability to manage its agricultural development agenda, including rice, is its status as a major petroleum exporter. Inevitably, therefore, the negative effects of the so-called Dutch Disease syndrome-a condition in which a boom in export earning does not translate into broad-based growth in the rest of the economy-come into play. Also referred to as a "resource curse," this affects countries that export a single resource commodity that leads to rising foreign-exchange earnings, either due to a price boom in global markets or a substantial increase in export volumes due to global demand.

The accompanying increase in export revenue and foreign-exchange reserves leads to an appreciation of the domestic currency and makes food imports (in addition to other goods and services) cheaper (Oyejide 1986). In the process, it undermines che competitiveness of domestic production of both tradeables and non-tradeables such as food staples. The situation can be made worse if increases in government revenue generated from the export earnings are not effectively transferred to other sectors of the economy. This is a reality that Nigeria has had to grapple with throughout its history since the discovery oflarge petroleum reserves.

Nigeria's resource curse occurred more as a result of poor governance and inherently weak institutions that existed in managing the petroleum sector and government revenues generated from it (Robinson, Torvik, and Verdier 2006; Sala-i-Martin and Subramanian 2013). Nigeria has struggled throughout its history in forming strong democratic institutions and transparent processes for governing its petroleum sector. The country is made up of several ethnic and religious groups, each with its own distinctive language, culture, and history. The country's diversity often makes it difficult to have a unified state; in this context, coordinated governance becomes more challenging.

Additionally, while the country's three-tier federal system of governance (i.e., a national, state, and local level) was intended to allow for greater autonomy and co avoid conflict across its various social groups and regions, it has instead encouraged rent-seeking behavior and politically motivated behavior

over the control of government revenues and resources at the national level. This is because over 90 percent of the government's revenue is generated at the top tier from petroleum exports. As a result, local and state authorities have to rely heavily on the federal government for much of their capital expenditure needs. Without sufficient transparency and accountability in place, such a vertical fiscal imbalance introduces a higher risk for rent seeking and other politically motivated behavior in the allocation of revenues, especially during a petroleum boom (Gboyega and Shukla 2011; Diao et al. 2010; Robinson, Torvik, and Verdier 2006).

The combination of a large and diverse population, varying degrees of resource endowments, and generally poor transparency and accountability of governing institutions has contributed to a difficult and turbulent political history for Nigeria. Table A.I in Appendix A provides a very brief chronology of this history. Fortunately, a more stable macroeconomic environment has been created over the past decade, and major reform efforts to improve public financial management, infrastructure and services, and transparency and accountability in the petroleum sector have been introduced (Gboyega and Shukla 2011). The efforts seem to be paying off, with signs oflow inflation, a steady supply of foreign-exchange reserves, and stable exchange rates (Table 1.3). Demand for rice, however, has continued to grow, fueled by economic growth

Importance of Agriculture and Evolution of Rice Policies

The discussion above shows that agriculture plays a dominant role in Nigeria's economy. The role of agriculture as a key source of employment, food security, and rural incomes is primarily due to the richly endowed and diverse agroecological landscape in Nigeria straddled by two of Africa's major rivers, the Niger and Benue (Figure 1.1). Freshwater resources are relatively abundant in Nigeria due to these two major rivers and other large bodies of water. Large swaths ofland serve as river basins along these two rivers, locally referred to as fodamas, which are particularly suitable for rice production. Periodically, however, water access can be affected by droughts and/or floods (Kuku-Shittu et al. 2013).

Nigeria's agricultural landscape can be broadly broken down into three major agroecological zones: humid, subhumid, and semiarid. The most commonly grown agricultural crops in the humid zone of the south are tree crops (e.g., cocoa, oil palm, plantain, and rubber); root crops (yam, cassava, and

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

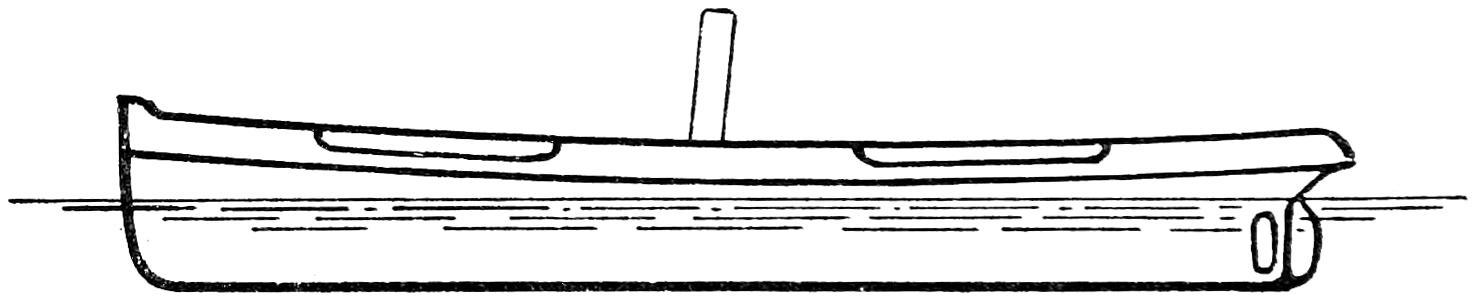

tons, was launched in December of 1907, and is one of the most notable productions of recent years. She is spar-decked throughout, with magnificent lines and a handsome appearance, whilst retaining the more conventional stem-plus-bowsprit. She has exceptional accommodation, all connected by corridors and vestibules with no fewer than a dozen state-rooms for guests. She is driven by two sets of triple-expansion engines actuating twin-screws, which, to minimise vibration, are at a different pitch, and run at varying speeds. She can carry sufficient coal to allow her to cruise for 6,000 miles, and both in internal and external appearance is as handsome as she is capable.

From a Photograph By permission of Messrs Camper & Nicholson, Ltd

With the capabilities of which the motor has shown itself to be possessed, the future of the steam yacht is perhaps a little uncertain. Economy would seem to indicate that the former has numerous merits in that it enables sail power to be utilised more readily, and thus may arrest the fashion which is advancing in the direction of steam. For long passages the extreme comfort which is now obtainable in the modern liner leaves no choice in the matter. To keep up a steam yacht for the usual summer season of four months is a very serious item of expenditure. If we reckon £10 per ton as the average cost—and this is the accepted estimate—it will be seen that such a yacht as the Wakiva, for instance, leaves but little change out of £10,000 per year, and for this expenditure most men would expect to get a very large return in the way of sport and travel. Whether or not a like proportionate return is made, at least in giving employment to thousands of shipbuilding and yacht-hands, this special branch of sea sport is deserving of the high interest with which it is regarded.

CHAPTER XI

THE BUILDING OF THE STEAMSHIP

W� propose in the present chapter, now that we have seen the evolution of the steamship through all its various vicissitudes and in its special ways, to set forth within the limited space that is now left to us some general idea of the means adopted to create the great steamship from a mass of material into a sentient, moving being.

Around the building of a ship there is encircling it perhaps far more sentiment than in the activity of almost any other industry. Poets and painters have found in this a theme for their imagination not once, but many times. Making a ship is something less prosaic, a million times more romantic, than making a house, for the reason that whilst the ship, as long as she remains on the stocks, is just so many thousand tons of material, yet from the very moment when she first kisses the water she becomes a living thing, intelligent, with a character of her own, distinct and recognisable. In the whole category of man-made things there is nothing comparable to this.

Fig 2 “THREE ISLAND,” TYPE

Fig. 3. TOP-GALLANT FORECASTLE TYPE.

Fig 4 TOP-GALLANT FORECASTLE TYPE, WITH RAISED QUARTER-DECK

Fig. 5. EARLY “WELL-DECK” TYPE.

Her genesis begins when the future owners resolve to have her built. Before any plans are drawn out there must first be decided the dimensions, the displacement and the general features which she is to possess, whether she is to be a slow ship, a fast ship, engaged in passenger work, cargo-carrying, on the North Atlantic route, for the

East through the Suez Canal, and so on; for all these factors combine to determine the lines on which she is to be built. Before we progress any farther, let us get into our minds the nine different types which separate the generic class of steamships. If the reader will follow the accompanying illustrations, we shall not run the risk of being obscure in our argument. Fig. 1, shows the steamship in its elementary form, just a flush-decked craft, with casings for the protection of the engines as explained on an earlier page. This represents the type of which the coasting steamer illustrated opposite page 134 is an example. This casing in the diagram before us is, so to speak, an island on the deck, but presently it was so developed that it extended to the sides of the ship, and, rising up as a continuation of the hull, became a bridge. At the same time a monkey forecastle and a short poop were added to make her the better protected against the seas. This will be seen in Fig. 2. This is known as the “three-island” type for obvious reasons. It must be understood that on either side a passage leads beneath the bridgedeck so as to allow the crew to get about the ship. But from being merely a protection for the bows of the ship, the monkey forecastle became several feet higher, so that it could accommodate the quarters of the crew, and this “top-gallant” forecastle, as it is known, will be seen in Fig. 3. At the same time, the short poop or hood at the stern has now become lengthened into something longer. But in Fig. 4 we find the lengthened poop becoming a raised quarter-deck—that is, not a mere structure raised over the deck, but literally a deck raised at the quarter. This raised quarter-deck was the better able to withstand the violent force of the sea when it broke over the ship. In Fig. 5 we have a still further development in which the topgallant forecastle is retained as before, but the long poop and the after end of the bridge are lengthened until they meet and form one long combination. This is one of the “well-deck” types, the “well” being between the after end of the forecastle and the forward end of the bridge-deck. This well was left for the reason that it was not required for carrying cargo, because it was not desirable to load the ship forward lest she might be down at the head (which in itself would be bad), whilst at the same time it would raise the stern so that the propeller was the more likely to race. But in the modern evolution of

the steamship it is not only a question of trim and seaworthiness that have been taken into consideration, but also there are the rules and regulations which have been made with regard to the steam vessel. Now, this well-space not being reckoned in the tonnage of the ship (on which she has to pay costly dues) if kept open, it was good and serviceable in another way. Considered from the view of seaworthiness, this well, it was claimed, would allow the prevention of the sweeping of the whole length of the ship by whatever water that broke aboard the bows (which would be the case if the well were covered up). If left open, the water could easily be allowed to run out through the scuppers. But this type in Fig. 5 is rather midway in the transition between the “three-island” type and the shelter-deck type. The diagram in Fig. 6 is more truly a well-decker, and differs from the ship in Fig. 5, in that the one we are now considering has a raised quarter-deck instead of a poop. She has a top-gallant forecastle, a raised quarter-deck and bridge combined, and this type was largely used in the cargo ships employed in crossing the Atlantic Ocean. It is now especially popular in ships engaged in the coal trade. The advantages of this raised quarter-deck are that it increases the cubic capacity of the ship, and makes up for the space wasted by the shaft tunnel. By enabling more cargo to be placed aft, it takes away the chance of the ship being trimmed by the head.

Fig. 7 shows a “spar-decker,” which is the first of the threedeckers that we shall now mention. This was evolved for the purpose of carrying passengers between decks. It has a continuous upper deck of fairly heavy construction, the bridge deck, of course, being above the spar deck. In Fig. 8 we have the “awning-decker,” which has a continuous deck lighter in character than the last-mentioned type, and like the latter, the sides are completely enclosed above the main deck. Because of this lightness of construction, it is not customary to add further erections above that are of any weight. Its origin was due to the desire to provide a shelter for the ships employed in carrying Oriental pilgrims. Later on this type was retained in cargo-carriers. Finally, we have the “shade-decker” as in Fig. 9, which is provided with openings at the side for ventilation. This type is so well known to the reader from posters and

photographs, that it is scarcely essential to say much. But we may remark that the lightly constructed deck fitted between the poop and forecastle is supported by round stanchions, open at the sides (as shown herewith), but sometimes closed by light plates. It is built just of sufficient strength to provide a promenade for passengers, or shelter for cattle, on the upper deck. This is still a very popular type for intermediate and large cargo steamers.

THE BUILDING OF THE “MAURETANIA.”

Showing Floor and part of Frames. From a Photograph. By permission of the Cunard Steamship Co.

With these different types before us, we may now go on with our main subject. Having settled the question as to the type and character of the steamship to be built, the next thing is to design the

midship section, which shows the general structural arrangements and scantlings of the various parts. In the drawing-office the plans are prepared, and the various sections of the ship worked out by expert draughtsmen attached to the shipbuilding yard. This necessitates the very greatest accuracy, and the building is usually specially guarded against those who might like to have an opportunity of obtaining valuable secrets. The plans having been worked out on paper, there follows the “laying off” on the floor of an immense loft, called the “mould floor,” where the plans are transferred according to the exact dimensions that are to be embodied in the ship. In many cases the future owner insists on a wooden model being submitted in the first instance, by the builder, so that a fair idea may be obtained of the hull of the proposed ship.

Each vessel is known at the shipbuilder’s by a number and not by her name. The keel is the first part of her to be laid, which consists of heavy bars of iron laid on to blocks of wood called “stocks,” and the line of these slants gently down to the water’s edge, so that when, after many months, the time arrives for the launching of the great ship, she may slide down easily into the sea that is, for the future, to be her support. After these bars have been fastened together, then the frames or ribs are erected, the ship being built with her stern nearest to the water, and her bow inland, except in the few cases (as, for example, that of the Great Eastern), where a vessel, owing to her length in proportion to the width of the waterspace available, has to be launched sideways. These ribs are bent pieces of steel, which have been specially curved according to the pattern already worked out. Let us now turn to the accompanying illustrations which show the steamship in course of construction. These have been specially selected in order that the reader might be able to have before him only those which are of recent date, and show ships whose names, at least, are familiar to him.

THE “GEORGE WASHINGTON” IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION.

Showing Framing from the Stern

From a Photograph By permission of the Norddeutscher Lloyd Co

The photograph opposite page 286 represents the Mauretania being built on the Tyne. This striking photograph shows the floor and the double cellular bottom of the leviathan in the foreground; whilst in the background the frames of the ship have been already set up. Some idea of the enormous proportions may be obtained from the smallness of the men even in the foreground. The next illustration represents the Norddeutscher Lloyd liner, George Washington, and exhibits the framing of the ship and bulkheads before the steelplating had been put on. The photograph was taken from the stern, looking forward, and one can see already the “bulge” which is left on either side to allow for the propeller shafts. Opposite page 290 is

shown the bow end of the Berlin (belonging to the same company) in frame, and on examining her starboard side it will be seen that already some of her lower plates have been affixed. Finally, opposite page 292 is shown one of the two mammoth White Star liners in course of construction. This picture represents the stern frame of the Titanic as it appeared on February 9th, 1910. No one can look at these pictures without being interested in the numerous overhead cranes, gantries and scaffolding which have to be employed in the building of the ship. The gantries, for instance, now being used at Harland and Wolff’s Belfast yard are much larger than were used even for the Celtic and Cedric, and have electric cranes, for handling weights at any part of the berths where the ships are being built. Cantilever and other enormous cranes are also employed. Cranes are also now used in Germany fitted with very strong electromagnets which hold the plates by the power of their attraction, and contribute considerably to the saving of labour.

Whilst the hull of the ship is being built, the engines are being made and put together in the erecting-shop—which also must needs have its powerful cranes—and after being duly tested, the various parts of the engines are taken to pieces again and erected eventually in the ship after she has been launched. After the frames and beams are “faired” the deck-plating is got in hand. Besides affording many advantages, such as promenades and supports for state-rooms, the deck of a ship is like the top of a box, and gives additional strength to a ship. The illustration opposite page 292 shows the shelter deck of the Orient liner Orsova The photograph was taken looking aft, on August 1st, 1908, whilst the ship was being built at Messrs. John Brown & Co.’s yard, Clydebank. The photograph is especially interesting as showing the enormous amount of material which has to go to the making of the steamship. But even still more significant is the next illustration, which shows one of the decks of the Lusitania whilst in course of construction. To the average man it seems to be well-nigh impossible ever to get such masses into the water.

BOWS OF THE

“BERLIN”

IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION.

THE “BERLIN” JUST BEFORE HER LAUNCH.

From a Photograph By permission of the Norddeutscher Lloyd Co.

After the plates have been all fastened by rivets to the frames, and the outside of the ship has been given a paint of conventional salmon pink, the time approaches for her to be launched. During her building the ship has been resting on the keel blocks where her centre touches, but her bilges have been supported by blocks and shores. These latter will be seen in the illustration of the Mauretania already considered. As the day for launching approaches, so also does the anxiety of the builders increase, for at no time in her career is the ship so seriously endangered. On the day of the launch the weight of the vessel is gradually transferred from the stocks on which she has been built, to the cradle, being lifted bodily from the keelblocks by means of an army of men driving wedges underneath her bottom. This cradle is constructed on the launching ways, and the

ship herself, being now “cradle-borne,” is held in place only by a number of props called “dog-shores.” At the right moment the signal is given for these to be knocked aside, and at the first symptoms of the ship in her cradle showing an inclination to glide, the bottle of wine is broken against her bows by the lady entrusted with so pleasant an honour. With a deep roar the ship goes down the ways, and as soon as the vessel becomes waterborne the cradle floats. The ship herself is taken in charge by a tug, whilst numerous small boats collect the various pieces of timber which are scattered over the surface of the water Two or three days before the launch, the cradle which has been fitted temporarily in place, is taken away and smeared with Russian tallow and soft soap. The ways themselves are covered with this preparation after they have been well scraped clean. In case, however, the ship should fail to start at the critical moment after the dog-shores have been removed, it is usual now to have a hydraulic starting ram (worked by a hand-pump) under the forefoot of the ship. This will give a push sufficiently powerful to start the great creature down her short, perilous journey into the world of water which is to be her future abiding-place.

But it can readily be imagined that such a ponderous weight as this carries a good deal of impetus with it, and since in most cases the width of the water is confined, precautions have to be taken to prevent the ship running ashore the other side and doing damage to herself—perhaps smashing her rudder and propellers, or worse. Therefore, heavy anchors have been buried deep into the ground, and cables or hawsers are led from the bows and quarters and attached thereto, or else to heavy-weights composed of coils of chain, whose friction over the ground gradually stops the vessel. Not infrequently the cables break through the sudden jerk which the great ship puts on them, and the anchors tear up the slip-way. Perhaps as many as eight cables may be thus employed, each being made fast to two or three separate masses of about five to fifteen tons, but with slack chain between so that only one at a time is started. As soon as the ship has left the ways, all the cables become taut, and they put in motion the first lot of drags. Further on, the next lot of drags receive their strain, then the third, so that no serious jerk may have been given, and the ship gradually brings up owing to the

powerful friction. Lest the force of the ship going into the water should damage the rudder or the propeller, these, if they have been placed in position, are locked so as to prevent free play. After this the ship is towed round to another part of the yard where her engines are slung into her by means of powerful cranes. The upper structures are completed, masts stepped and an army of men work away to get her ready for her builders’ trials. Carpenters are busy erecting her cabins, painters and decorators enliven her internal appearance, and upholsterers add the final touches of luxury to her saloons and lounges.

STERN FRAME OF THE “TITANIC,” FEB 9, 1910

From a Photograph By permission of Messrs Ismay, Imrie & Co

Turning now to the illustration facing page 290, we see the Norddeutscher Lloyd Berlin just before she was launched. The anchors and cables which will be dropped as soon as she has floated will be seen along her port side, and the platform for her christening is already in place. In the illustration facing page 294,

which shows the launch of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company’s Araguaya, we have a good view afforded of the ship as she is just leaving the ways and becoming water-borne. The other illustration on the same page shows the launch of one of those turret-ships to which reference was made in an earlier chapter. In the picture of the Berlin will be seen the system of arranging the steel plates in the construction of the ship, and the rivets which hold them in place.

From a Photograph By permission of Messrs Anderson, Anderson & Co

ONE OF THE DECKS OF THE “LUSITANIA” IN COURSE OF CONSTRUCTION

One of the most important events of the ship’s life is her trial trip. Before this occurs the ship’s bottom must be cleaned, for a foul underwater skin will deaden the speed, and give altogether erroneous data. The weather should be favourable also, the sea calm, and the water not too shallow to cause resistance to ships of high speed, while a good steersman must be at the helm so as to keep the ship on a perfectly straight course. Around our coasts at various localities are noticeable posts erected in the ground to indicate the measured mile. To obtain the correct data as to the speed of the ship, she may be given successive runs in opposite directions over this measured mile; a continuous run at sea, the number of revolutions being counted during that period, and a continuous run past a series of stations of known distances apart, the times at which these are passed being recorded as the ship is abreast with them. For obtaining a “mean” speed over the measured mile, one run with the tide and one against the tide supply what is

required. During these trials, the displacement and trim of the ship should be as nearly as possible those for which she has been designed. But besides affording the data which can only show whether or not the ship comes up to her contract, these trials are highly valuable as affording information to the builder for subsequent use, in regard both to the design of the ship herself and the amount of horsepower essential for sending her along at a required speed. The amount of coal consumption required is also an important item that is discovered. This is found as follows: Let there be used two bunkers. The first one is not to be sealed, but the latter is. The former is to be drawn upon for getting up steam, taking the ship out of the harbour, and generally until such time as she enters upon her trial proper. This first bunker is then sealed up, and the other one unsealed, and its contents alone used during the trial. After the trial is ended, the fires being left in ordinary condition, the second bunker is again sealed up, and the first bunker drawn upon. By reckoning up the separate amounts it is quite easy afterwards to determine the exact quantity which the ship has consumed during a given number of knots in a given time. Finally, after every detail has been completed, the ship is handed over to her owners and steams away from the neighbourhood of her birth. Presently she arrives at her port, whence she will run for the next ten or twenty years, and before long she sets forth with her first load of passengers, mails and cargo on her maiden trip across the ocean. To begin with, she may not establish any new records for speed; for a ship takes time to find herself, and her officers to understand her individualities. “Know your ship” is one of the mottoes which an ambitious officer keeps ever before him, and if this is true on the navigation bridge, it is even still more true down below, where the engines will not show their full capabilities for several passages at least.

LAUNCH OF THE “ARAGUAYA ”

From a Photograph By permission of the Royal Mail Steam Packet Co

LAUNCH OF A TURRET-SHIP.

From a Photograph By permission of Messrs Doxford & Sons, Sunderland