5 minute read

Landmark Opinion Finds Public School Funding Inadequate

Continued from page 9

Governor, and the Secretary of Education) were initially successful in having the suit dismissed on preliminary objections. The Pennsylvania Supreme Court, however, reversed and remanded. After the remaining preliminary objections were denied, the parties engaged in two years of discovery before proceeding to trial.

At issue was the Petitioners’ contention that low-wealth districts, “which frequently serve higher need students, are not on a level playing field with higher-wealth districts, such that the current funding system violates equal protection principles.”3 Pennsylvania’s Constitution has contained provisions for a public school system since 1776, with the “thorough and efficient” language first adopted in 1874.4

The Education Clause of the Pennsylvania Constitution guarantees students a “full or complete system of public education that is effective in producing students who, as adults, can participate in society, academically, socially, and civically, which thus serves the needs of the Commonwealth.”5 To determine whether the current system meets that requirement, the Court found that “the appropriate measure is whether every student is receiving a meaningful opportunity to succeed academically, socially, and civically, which requires that all students have access to a comprehensive, effective, and contemporary system of public education.”6 While the state need not provide a uniform system state-wide, to pass constitutional muster, opined the Court, the educational opportunity provided needs to be “comprehensive, effective, and contemporary.”7

For the legal historians, the Court outlined the Commonwealth’s constitutional history regarding the Education Clause, including our forebearers’ thoughts on the value of public education, like this one from Governor George Wolf in 1830: Of the various projects which present themselves, as tending to contribute most essentially to the welfare and happiness of a people, and which come within the scope of legislative action, and require legislative aid, there is none which gives more ample promise of success, than that of a liberal and enlightened system of education, by means of which, the light of knowledge will be diffused throughout the whole community, and imparted to every individual susceptible of partaking of its blessings; to the poor as well as to the rich, so that all may be fitted to participate in, and to fulfil all the duties which each one owes to himself, to God, and to his country. The constitution of Pennsylvania imperatively enjoins the establishment of such a system. Public opinion demands it. The state of public morals calls for it; and the security and stability of the invaluable privileges which we have inherited from our ancestors, require our immediate attention to it.8

Having outlined why the suit could be brought, the Court turned to consideration of how to determine whether a constitutional violation had occurred. Unsurprisingly, the parties disagreed on what criteria should be considered by the Court. The Respondents argued that only the “inputs” a district provides should be considered in evaluating the constitutionality of the system, as the “outputs”, i.e. – test scores and other quantifiable metrics – involve multiple factors outside of the school’s control, such as the student’s home life. The Petitioners argued that both are relevant and meaningful.

The Court rejected an outputs-only analysis and engaged in a thorough examination of both factors, finding that without doing so “there would be no way to gauge the adequacy of the system, and whether it is working to provide the opportunity to succeed to all students.”9 Analyzing both, the Court found that students in certain Pennsylvania schools are not receiving a meaningful opportunity to succeed.

Underfunded Schools Are Deficient

While the Court expressly stated it took no pleasure in pointing out the deficiencies of the system,10 it systematically and unflinchingly laid bare both the realities facing districts and the holes in the Respondents’ arguments. It elected not to comment on a controversial line of questioning from counsel for the Senate President Pro-Tempore wherein he seemingly scoffed at standards mattering for students entering certain professions, asking a witness, “What use would someone on the McDonald’s career track have for Algebra 1?”

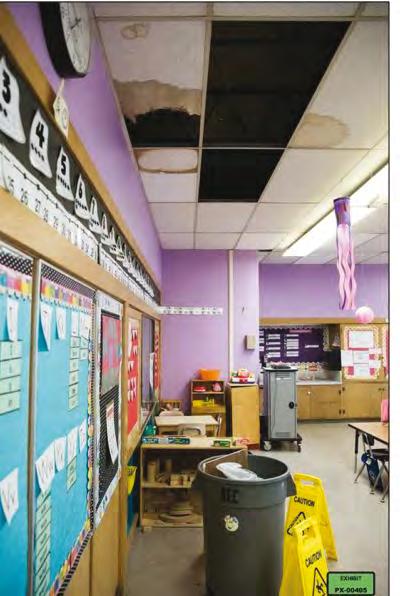

The question went viral – although any reference to it was absent from the Court’s analysis.11 It was hardly needed to make the Court’s point. Instead, the Court imbedded charts of hard data and photographs of crumbling, overcrowded schools introduced during the trial to illustrate its findings.

The Legislative Respondents argued that there was no evidence that “low-wealth school districts lack the basic instrumentalities of learning, again noting that several Petitioner Districts have recently revised their curricula and purchased new materials, including textbooks and online instructional tools.”12 They asserted that no evidence was presented that any such district “lacks desk, chairs, tables, or writing materials.”13

To the contrary, the Speaker asserted that “not only are lowwealth districts in Pennsylvania, including Petitioner districts, able to offer a basic education to their students, they offer opportunities that go far beyond.”14 Any evidence of insufficient funding, the Respondents asserted, was specious.15 The President Pro-Tempore also asserted that districts are not spending their funding in a cost-effective manner or were maintaining large balances16 in an attempt to undercut the Petitioners’ causation evidence. The Court rejected these arguments.

Five Prongs Of Adequacy In Education

The Court reviewed five inputs it found critical to any determination of the constitutional adequacy of the school system: 1) funding; 2) courses, curricula, and other programs; 3) staffing; 4) facilities; and 5) instrumentalities of learning.

Regarding funding, the Court found that “low-wealth districts cannot generate enough revenue to meet the needs of their students, and the pot of money on which Legislative Respondents allege they sit is not truly disposable income.”17 It found that studies and formulas employed by the state to analyze and rectify funding issues establish “the existence of inadequate education funding in low-wealth districts”.18

On the topic of the large fund balances highlighted by the Respondents, the Court found that balances are required by state rules and are not actually “expendable dollars.”19 The Court went on to state that balances were also advisable to enable the district to continue to operate when funding is delayed, there are unexpected expenses, and to obtain loans. At least one such balance was earmarked for sewage system repairs, and another was planned to replace infrastructure and technology. Several districts had almost zero balances in their accounts, and but for recent temporary COVID funding, would have had a negative balance, or were only in a better financial position due to “draconian” cuts they made.20

A parade of broken promises or illusory offerings filled the Court’s analysis of the courses and curricula offered by low-wealth districts. Electives are not offered, teachers are simultaneously teaching different levels of the same subject at the same time in the same classroom, or are teaching different courses simultaneously, and students are unable to take courses because of limits on enrollment due to space or money.21 Courses are cut when temporary funding runs out.22 Elective courses like art and music are cut or are often canceled because the school lacks adequate staffing for the day and moves those teachers to core subjects.23

Curriculum fails to meet state standards because the district lacks the money, personnel, and time to revise them.24 AP classes are out of reach because districts are forced to charge parents in the poorest district in the state for the cost of the course.25 Advanced classes are also out of reach for students because districts lack the resources to prepare students for AP work, from elementary school on.26

The Court also outlined a lack of reading specialists, psychologists, behavioral interventionalists, tutors, after school programs, support services, and high-quality pre-K, to name a few.27 Of note, the Respondents did not deny the importance of programs like athletics, art and music, and other educational programs which the Petitioner districts lack.

Continued on next page

Offers:

• Comprehensive outpatient evaluations conducted by a therapist trained in substance use disorders.

• A range of outpatient group counseling options for teens and adults.

• Individual counseling.

• Trauma Services.

• Critical support for family members.

• Specialized addiction program.

• Prevention and education programs.

• Recovery support for alumni.