13 minute read

Faltering growth

Kate harrod-wild specialist Paediatric dietitian, Betsi Cadwaladr university health Board

Kate harrod-wild is a paediatric dietitian with over 20 years of experience of working with children in acute and community settings. Kate has also written and spoken extensively on child nutrition.

Advertisement

faltering growth, previously known as failure to thrive (ftt) and also known as weight faltering, is the term used to describe infants and young children who fail to achieve expected growth for their age as measured by their weight and length or height and plotted on a suitable growth chart.

This can be identified by the weight crossing two centile spaces downwards, or where a difference of more than two centile lines between the weight measurement and length or height persists over several measurements. Sometimes dietitians will see children, particularly infants, in their clinics who have been referred because of a low weight. However, this is meaningless in most cases if not accompanied by a length or weight measurement, as the child may simply be small, and primary healthcare professionals need to ensure that length or height is measured where concerns regarding weight emerge. However, if both weight and length or height is below the 0.4th centile, then this is considered abnormal and investigations should be carried out to try and establish the cause.

On the UK 1990 growth charts that were used until the mid-2000s, about five percent of children would have an episode of growth faltering. However, on the newer WHO growth charts, based on the slower pattern of growth of breastfed babies to six months, only about 0.5% of babies are less than the 2nd centile at 12 months (1). Historically, ‘failure to thrive’ was divided into organic and non-organic. However, this is now considered to be unhelpful, as few children with faltering growth have organic disease. The evidence suggests that organic disease is unlikely in children who are asymptomatic and well on examination, so that investigations should only be used to rule out rare major conditions (see Table 1) rather than to identify a cause of the faltering growth (2).

Routine weight monitoring should identify most cases of faltering growth; it is recommended that this should occur during the first week as part of the assessment of feeding and at eight weeks, 12 weeks, 16 weeks, one year (usually around the time of immunisations), and whenever concerns are raised. However, a population study of children with weight faltering found that although children were identified at a mean age of 15.5 months, the slowing of their weight

table 1: Possible investigations to carry out in secondary care (2)

investigation indications Possible cause

Full blood count any persistent weight faltering anaemia, leukaemia Ferritin any persistent weight faltering iron deficiency urea and electrolytes any persistent weight faltering Renal failure, electrolyte abnormalities thyroid function tests any persistent weight faltering thyroid disease Coeliac blood tests any persistent weight faltering Coeliac disease mid-stream urine any persistent weight faltering urinary tract infection Chromosome analysis girls turner’s syndrome Chest radiograph infants under three months; history of chest infection Cardiac abnormalities; cystic fibrosis sweat test history of respiratory infection Cystic fibrosis Vitamin d levels solid diet is limited, dark skin Rickets

gain began in the early weeks and 50 percent had already crossed the screening threshold by age six months (3). Therefore, it is important that primary care health professionals, particularly health visitors, ensure that infants are weighed at the time of immunisations and that these are plotted in their primary health care record and action is taken where faltering growth is identified.

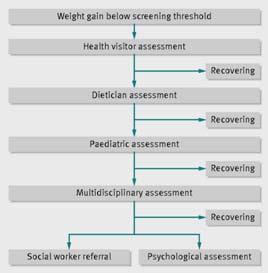

As shown in Table 2 (2), if slow weight gain is identified, the health visitor should carry out an assessment. This should include: • method of feeding; • number of feeds per day; • amount of time at the breast (and whether one or two breasts) or volume of formula taken; • for formula fed infants, the method of making up the bottle, the formula given, the type and size of teat; • any solids, number of times per day, foods given, amounts taken; • any feeding related problems - colic, constipation, vomiting, feed refusal; • any relevant psychosocial factors, e.g. maternal depression.

On the basis of this assessment, the health visitor should give any relevant advice and ask the mother to keep a record of fluids and foods given over a period of time, particularly if this unclear. The infant should be reweighed at a suitable interval. Optimal intervals and timings for measurement have not been formally established, but the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health suggest weighing no more than monthly before age six months, every two months aged six to 12 months, and every three months after one year (4). In practice, if there are concerns regarding weight gain, weight monitoring is probably going to occur more frequently.

If this does not improve the weight gain, then referral to the paediatric dietitian should be triggered. The paediatric dietitian will ask similar questions to the above but will do so in more detail. They will also ask about: • feeding history - milks taken, age at weaning (if relevant), any problems; • relevant medical history; • any siblings; • any history of atopy; • any relevant symptoms (see Table 3).

• Colic • Vomiting • Reflux • Choking episodes • Wheezing • Coughing • Eczema • Loose stools • Constipation

They will explore the infant and child’s diet in detail including the following: Breastfeeding - if the child is breastfed, the dietitian will want to know if the baby latches on well - is there any slurping? Do they come off the breast frequently? Does the baby feed from one breast or two? Does the Mother feel that the baby empties the breast?

Possible advice: • Ensure baby is latching on - signpost to breastfeeding counsellor. • Ensure baby empties one breast before offering the other. • If the mother produces lots of milk, consider expressing some milk before the start of the feed to ensure that the baby receives the energy rich hind milk. The dietitian will try to avoid adding in formula unless absolutely necessary; if the infant is old enough, energy dense solids could be added in as an alternative.

Formula fed - the dietitian will try to establish the number of feeds per day given, how much feed is made up, how it is made up and how much formula

is actually taken by the baby at each feed. The family should also be asked about the teats used and different formulas (if any) that have been tried and the reasons for switching. Families are not always very good at giving this information and this can make it difficult to establish how much the baby is actually taking. A calculation of how much the baby is taking in mls/kg should be made; on average, a baby preweaning should be taking approximately 150mls/ kg. Less or more than that is normal if the infant is thriving; caution should be exercised if the family contend that the infant is taking a lot more than 150mls/kg but is not gaining weight satisfactorily.

Possible advice: • If the actual amounts taken are unclear, then the parents should be asked to keep a record of actual amounts taken for three days. • If the amounts taken appear to be excessive, but weight gain is poor, it needs to be established if this is because the infant is vomiting. In this case, reducing volumes may actually help to reduce vomiting and improve weight gain. A pre-thickened formula (e.g. Aptamil AR, SMA

Staydown) or a thickener such as Infant Gaviscon or Carobel prescribed by the GP, may help reduce vomiting and increase weight gain. • If the amounts taken seem much less than needed for weight gain, the reasons for this should be established. A history of vomiting, colic or wheezing may suggest gastro-oesophageal reflux (GOR) and, again, a prethickened formula or a feed thickener may help. If these do not help, then medication may be needed; some

GPs may prescribe, but others may wish to refer to a Consultant Paediatrician in secondary care at this point. If it is not possible to improve volumes taken, then an energy dense formula (see

Table 4) or energy dense solids or both (depending on age) may be appropriate. Care needs to be taken to ensure that increasing the calorie density of the formula does not simply reduce the volumes taken.

Older baby or young child on mixed diet - it needs to be established which foods and textures the child is accepting. Amounts offered versus amounts taken need to be clarified. Also the family needs to be asked about how many times a day the child is offered food. Intake of fluids - which drinks does the child have, how often and whether from a bottle or cup needs to be known. At this age, the condition of dentition is also relevant and the family needs to be questioned about dental hygiene and visits to the dentist.

Possible advice: • Food needs to be offered at three meals and two to three snacks per day. • Food needs to be calorie dense - and in reality that means high fat. Food should be fried wherever possible and cheese, cream, oil and butter used to fortify foods. • Length of meals - meals should last no longer than 30 minutes; due to parental concerns regarding weight, in some households, meals can go on for an hour or two. • Food should be taken away without comment if not eaten. • Social eating - infants and young children should eat with the rest of the family wherever possible as social eating tends to improve intake. Every effort should be made to ensure that mealtimes are relaxed occasions. • Fluids - over a year, drinks should be given from a cup, not a bottle. Adequate, but not excessive fluids should be given during the day; that means a small cup with each meal and snack, but children should not be allowed to sip on drinks throughout the day as this affects appetite. • Wherever possible, food fortification should be used rather than nutritional supplements, as there is a danger that they may simply replace solid food. However, when asking parents to make changes, they can be useful to help manage parental anxiety. Wherever possible, they should be used on a short-term basis while food intake improves. • Home visit - wherever possible, a home visit and observation of a meal can be key to discovering the root of a child’s feeding problems. In many cases this is not practicable or possible.

However, liaison with the Health Visiting service may mean that a Health Visitor or Nursery

Nurse may be able to carry out the visit with a check list of observations to complete and report back to the Dietitian. Particularly for infants who have atopic conditions or who have parents or siblings with atopic history (eczema, asthma, hayfever, allergic rhinitis), consideration should be given as to whether poor growth

formula under one year/<8.0kg

sma high Energy infatrini (nutricia) similac high Energy (abbott)

over one year/>8.0kg

Fortini 1.0 multifibre (nutricia) Paediasure (abbott) Fortini Paediasure Plus (abbott) Frebini energy (Fresenius) Resource junior (nestle)

energy (kcals/100mls) Protein (g/100mls)

90 101 100 2.0 2.6 2.6

100 101 150 151 150 150 2.4 2.8 3.4 4.2 3.8 3.0

is caused by cows’ milk allergy. However, further discussion of food allergy is out of the remit of this article.

For most infants and young children, poor weight gain will be short-lived and they respond to simple advice on calorie density and behaviour modifications, a minority may need advice from other professionals: • Speech and Language Therapist - where problems with textures are identified or there are any concerns regarding swallowing. • Psychologist - particularly where parental anxiety is high and parents are finding it difficult to cope with their child’s eating behavior. • Paediatrician - if a child’s calorie intake seems to be adequate and they are still not putting on weight, or if there are concerns about possible medical conditions, the child should be referred to a Consultant Paediatrician for assessment and, if appropriate, investigations (Table 2). • Social Worker - historically it was felt that many children with faltering growth were suffering from abuse or neglect. Although this is now not the case, undoubtedly poor growth can be a symptom of emotional deprivation. Where a paediatric dietitian has any concerns of this nature, or sees clear evidence of major social problems, such as drug or alcohol abuse, they

should speak to their line manager and the child’s health visitor and/or GP as appropriate. Where concerns persist, the family should be referred to the social work team for assessment and this may result in a child being treated as a ‘child in need’ or entry on to the child protection register after investigation of the family’s circumstances. In some areas, feeding teams are available, containing a combination of some or all of these professionals. This is a more efficient way to deal with difficult feeding behaviours as there can be a single assessment and more streamlined signposting to the appropriate professionals.

Faltering growth can be very distressing for a family, especially for mothers, who are ‘programmed’ to feed their children. A sensitive, multidisciplinary approach can help families regain their confidence to feed their children. In most cases, relatively simple measures, along with reassurance, can restore a normal pattern of weight gain. Where this is not possible, a thorough assessment and a stepwise approach give the best chance of establishing the cause of the faltering growth. Even when this is not possible, the family need to have confidence that the dietitian will support them along the path to restoring normal growth and will refer them to the appropriate professionals to ensure that this occurs.

references 1. wright c, Lakshman r, emmett P, Ong KK. Implications of adopting the wHO 2006 child Growth standard in the UK: two prospective cohort studies.

Arch Dis child 2008; 93: 566-9 2. shields B, wacogne I, wright c. weight faltering and failure to thrive in infancy and early childhood BMJ 2012; 345 doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj. e5931 (accessed 8.10.14) 3. wright c, Birks e. risk factors for failure to thrive: a population-based survey. child care Health Dev 2000; 26: 5-16 4. UK Department of Health. Using the new UK-world Health Organisation 0-4 years growth charts: information for healthcare professionals about the use and interpretation of growth charts. Department of Health, 2009

(previously Nutramigen AA)

Nutramigen PURAMINO: effectively manages severe cow’s milk allergy (CMA) symptoms,1† for a difference that’s plain to see.

A new and improved hypoallergenic amino acid-based formula for severe CMA and multiple food allergies: Trusted and accepted1† 33% MCT oil to facilitate absorption of fat-soluble nutrients Certifi ed halal and kosher New look to distinguish from our eHF, Nutramigen LIPIL Find out more at www.nutramigen.co.uk/puramino

A solution for all your CMA needs

Reference: 1. Burks W et al. J Pediatr 2008;153:266–271. †This study was conducted with Nutramigen AA without MCT oil. IMPORTANT NOTICE: Breast milk is the best nutrition for babies. The decision to discontinue breastfeeding may be diffi cult to reverse and the introduction of partial bottle-feeding may reduce breast milk supply. Failure to follow preparation instructions carefully may be harmful to your baby’s health. Parents should always be advised by an independent healthcare professional regarding infant feeding. Products of Mead Johnson must be used under medical supervision. *Trademark of Mead Johnson & Company, LLC. © 2015 Mead Johnson & Company, LLC. All rights reserved. This material is for healthcare professionals only. EU15.509. January 2015