32 minute read

News

Tabitha Ward RD

Tabitha is a Senior Dietitian in Weight Management. She is also a freelance health writer.

Advertisement

TabithaWardRD

To book your company's product news for the next issue of NHD call 01342 824073

BARIATRIC SURGERY REDUCES

COVID-19 SEVERITY

In recent months, researchers have identified obesity as a risk factor for developing more severe COVID-19, which may require hospital admission, time in intensive care and ventilator support. But a new study published in Obesity Surgery, has found an association between bariatric surgery and clinical outcomes for COVID-19, suggesting that previous weight-loss surgery could affect the severity of outcomes.

The systematic review looked at 9022 patients from three retrospective studies. Researchers looked at hospital admissions in those with COVID-19, as well as the risk of mortality in those who have had bariatric surgery versus those who had not. Results showed a significantly lower risk of hospital admissions in those who had previously had bariatric surgery, compared with those who had not. There were also fewer cases of mortality in those who had previously had bariatric surgery.

These results suggest that previous bariatric surgery is associated with a lower rate of mortality and hospital admissions in patients with obesity who became infected with COVID-19. However, there was a risk of bias in this study for confounding and selection. Larger studies are, therefore, needed with better quality data.

For more information, visit: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11695-020-05213-9

PROMOTIONS OF UNHEALTHY FOODS RESTRICTED FROM APRIL 2022

The UK Government has outlined a plan for a ban on the promotion of food and drinks high in fat, salt or sugar in retailers, both instore and online from April 2022. The new rules come following the antiobesity strategy of July 2020. The restrictions have been designed to support the nation into making healthier food choices.

What do the new measures include?

• Retailers will be prohibited from offering multibuy promotions such as ‘BOGOF’ or ‘3 for 2’ on unhealthy products. • Stores will not be allowed to feature unhealthy foods in key locations. • Free refills on soft drinks will be prohibited in the eating-out sector. • Restrictions apply to medium and large stores (over 2000 square feet).

More information at: www.gov.uk/government/news/promotions-of-unhealthy-foods-restrictedfrom-april-2022

SACN STATEMENT ON NUTRITION AND OLDER ADULTS

The Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) has recently released a statement on nutrition and older adults living in the community and the impact on healthy ageing. The last report of this nature was carried out by COMA back in 1992. Since then, the UK population has changed dramatically and there is an increasing number of older adults, with one in five people now aged 65 years and over.

The statement reports on the National Diet and Nutrition Survey (NDNS) and provides an overview of the evidence up until February 2019. It reports that adults aged 65 to 74 and 75 years and over exceeded maximum recommendations for intakes of saturated fat, free sugars and salt. They also failed to meet the recommendations for fruit and vegetables, fibre and oily fish. Not dissimilar to the trend of the overall UK population.

In terms of nutritional status, the statement shows some evidence for low micronutrient intakes of vitamin D and folate, particularly in women aged 75 and over.

SACN also looked at BMI using the NDNS data and found that a high percentage of older adults were living with overweight or obesity, with 87% of men and 68% of women aged 65-74 living with overweight or obesity. In contrast, the prevalence of underweight in older adults was low: just 7% of men and 3% of women aged 75 years and over. In those aged 65-74, less than 1% of men and 3% of women were underweight.

To check out the full report, go to: www.gov.uk/government/publications/sacn-statement-on-nutrition-and-older-adults

FOOD PATTERNS PARTLY DOWN TO GENETICS

A recent study at King’s College London has shown that food intake patterns are partly due to our genetics.1 The study, published in the journal Twin Research and Human Genetics, was the first comprehensive investigation looking into the contribution of genes and the environment on the variation of dietary indices. The responses of food frequency questionnaires (FFQ) from 2590 female twins, including both identical and non-identical twins, were analysed.

Results showed that identical twins were more likely to have similar scores across dietary indices, compared with non-identical twins. This was also the case when other factors, such as body mass index and exercise levels, were taken into account. This study suggests that food and nutrient intake, as measured by nine dietary indices, is also partly under genetic control.

As the study looked at female twins only, with an average age of 58, future research is needed to look at a more varied population to see if the findings are similar.

1 Mompeo O, Gibson R, Christofidou P et al (2021). Genetic and Environmental Influences of Dietary Indices in a UK Female Twin Cohort. Twin

Research and Human Genetics,1-8. doi:10.1017/thg.2020.84

Ruth James RD MSc SENr MBA

Ruth was previously a Clinical Gastro Dietitian and NHS Manager. She is now a Registered Sports Nutritionist who is passionate about helping elite and recreational sports people realise their full performance potential.

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

NUTRITIONAL CONSEQUENCES OF THE COVID-19 PANDEMIC

Nutrition has been recognised as an important factor in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, with obesity seen as a key risk for severe illness. The implementation of restrictive public health measures has increased the challenges facing healthy eating, physical activity and mental resilience. This article explores these key nutrition themes, which are often interrelated.

The impact of poverty from job and economic uncertainty and the effect of school closures on children’s food intake, have been highlighted during the pandemic. The crisis has also emphasised the critical role of nutrition in immune health. Dietitians and nutritionists are in a pivotal position to address these issues, either in a clinical setting in ITU or in long-COVID clinics, by influencing and helping the disadvantaged and advising food providers. Tackling misinformation in the media is another key issue we can try to address.

OBESITY One of the risk factors for severe COVID-19 is obesity (a Body Mass Index >40). A meta-analysis of 75 international studies examined the association of excess weight across the COVID-19 spectrum, from infection to death. It found that individuals have more than double the likelihood of going into hospital if they are obese and 50% more likelihood of dying. This may be due to the impact of overweight on cardiorespiratory and lung functioning, as well as on immune dysfunction.

Obesity can also influence the development of hypertension, diabetes, stroke, atrial fibrillation, kidney and liver diseases and overall heart failure. These comorbidities cause reduced pulmonary function, functional capacity and respiratory system compliance, along with reduced β-cell functioning and increased insulin resistance. These can limit proper immune responses to viral exposures and increase a patient’s difficulty responding to common COVID-19 therapy such as ventilatory support.

The lockdown during the first wave of the pandemic is known to have already led to quarantine weight gain, so it is expected that we will see another negative impact during the second and third waves. Moreover, mental health issues have been exacerbated in both overweight children and adults, due to self-isolation, disruption of usual weight control strategies, stress and stigmatisation. This has focused a spotlight on obesity as a global health problem, along with the associated risks of deprivation, poverty and ethnicity.

For more on the impact of COVID-19 on obesity see Emma Berry’s article in NHD February, issue 160, p8.

THE IMMUNE SYSTEM AND COVID-19 Whilst attention has focused mainly on vitamin D in enhancing the immune system and reducing the risk of infections, other vitamins, trace elements, amino acids and fatty acids have also been implicated.

Vitamin D, zinc and selenium seem to be particularly important in antiviral immunity. Immune cells

have the vitamin D receptor, some immune cells produce the active form of vitamin D, and vitamin D, zinc and selenium all support antigen presenting cells, T cells and B cells to function. Zinc has been shown to inhibit the RNA polymerase required by RNA viruses, like coronaviruses, to replicate and spread. Clinical deficiencies in zinc and selenium compromise the immune system and can increase the rate of infection. Zinc supplementation has been shown to decrease risk of mortality with severe pneumonia in some settings. Limited emerging evidence suggests low zinc or selenium status could be linked to more severe COVID-19, but more research is needed.

Low vitamin D status is associated with increased risk of COVID-19 infection, as well as hospitalisation. Observational data show that up to 80% of people admitted to hospital with COVID-19 are deficient in this vitamin compared with 20% in the population. Interestingly, vitamin D deficiency is also more prevalent in individuals living with overweight and obesity compared with individuals of normal weight. Some research suggests that deficiency prevalence is 25% to 35% with overweight and obesity.

The complications of obtaining sufficient vitamin D are further exacerbated by the global quarantines, isolation and stay-at-home orders. For many, especially older individuals in nursing homes, as well as for ethnic minorities who more commonly live in densely populated areas, these measures include little or no movement outside their homes. When combined with the typical Western diet high in processed foods that lack vitamin D, these restrictive lockdown measures can impair one’s ability to obtain sufficient vitamin D needed to maintain or boost immune functioning. This, in turn, could reduce the ability to prevent or fight COVID-19 in susceptible individuals.

Currently, there is a lack of scientific evidence to recommend vitamin D for prevention of COVID-19, but research is ongoing. As a precaution, to ensure good bone and muscle health, and in consideration of more limited exposure to sunlight in the pandemic (due to isolation), vitamin D supplements for the general population are recommended (400 IU [10 µg] per day), particularly in winter months, with caution against doses higher than the upper limit (4000 IU/d; 100 µg/d).

There may be an association between seasonal upper respiratory tract infections and low vitamin D status. In a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of individual participant data from randomised controlled trials, vitamin D supplementation reduced the risk of acute respiratory tract infections (ARTI). However, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in these studies.

RACE AND ETHNICITY Recent reports suggest that racial and ethnic minorities have experienced an increased rate of infection, as well as a disproportionate amount of negative COVID-19-related outcomes compared with white individuals. The increased risk of COVID-19 transmission continues to highlight the health disparities experienced by these minority groups and can be related to social determinants of health, socioeconomic and educational input; healthcare access; racial discrimination and biological factors. Biologically, racial and ethnic minorities experience a higher rate of comorbidities that may negatively affect COVID-19 outcomes, including morbid obesity, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, liver and kidney diseases and HIV and respiratory issues including asthma and chronic obstructive respiratory disease.

Factors that may cause disproportionate vitaminD deficiency in darker-skinned individuals include reduced ability to synthesise vitamin D from the skin because of the darker pigmentation, as well as reduced levels of vitamin D-binding protein, which transports vitamin D in the body for activation and functioning.

FOOD INSECURITY AND POVERTY The coronavirus pandemic has led to food shortages, increased food prices and loss of income for many. Uncertainty around BREXIT negotiations and the economic fallout have complicated issues further. The lack of consistent access to nutritious food sources is associated with chronic physical and mental health problems.

Food banks have seen exponential growth in need over the last year. Child hunger remains a huge issue – over a million new schoolchildren signed up for free school meals last September, bringing the total to 2.5 million.

EMOTIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL PROBLEMS Working at home, home schooling and childcare, job insecurity and the threat of COVID-19 itself, have all caused an increase in mental health issues in the general community, with even harsher effects experienced by people with existing mental illnesses and mood disorders.

The pandemic has had especially “strong and wide-ranging” effects on people with anorexia and bulimia nervosa, for example when people stockpile high-risk foods out of fear of food supply disruption, people with bulimia face intense urges to binge. Anxiety around food availability can also be a triggering environment for individuals with eating disorders, creating an urge to starve, while lack of social support and the inability to access food consistently can disrupt regular meal plans.

Studies on food insecurity and eating pathology have heightened concern about the impact the added effect of the pandemic may have on the eating behaviours of children and adolescents.

SHOPPING AND CONSUMER BEHAVIOUR The pandemic has acted as a catalyst for online growth and home delivery for food products and this is set to continue. Online grocery doubled its market share in December 2020. More than six million households in the UK tried online shopping last year, largely due to the physical restrictions in place. Shopping online may become the new norm. Also, the pandemic has made people focus on things which will make them feel they are contributing more to the welfare of the planet and “food with a purpose”.

Local foods that have a story and are environmentally friendly are on the rise. More consumers want to know where their food comes from and how it impacts not only their health, but the health of their communities and the environment.

Convenience is still important and home meal kits and fresh food delivered to your door will continue to grow in demand. Companies will not only try to make nutritious food more accessible, but they will be more open and transparent about what ingredients they use and how their food is prepared.

The coronavirus pandemic has had a significant impact on consumer eating habits. More convenience products and canned foods with longer shelf lives are being purchased. The consumption of alcohol and confectionery has also increased, but the consumption of fresh fruit and vegetables has declined.

THE IMPACT OF BREXIT Although about 52% of the UK’s food needs are currently met by domestic production, the remainder is heavily dependent on imports from European Union countries. The UK’s reliance on the EU is especially acute in the horticulture sector, with about 40% of vegetables and 37% of fruit sold in the UK being imported from EU countries. At this time of year, outside of the British growing season, the country’s dependence on Europe is even more stark, with practically all of UK tomatoes, lettuces and soft fruit coming from the Netherlands and Spain.

Because affordability is the major determinant of consumer behaviour, food price inflation is likely to drive down demand for fruit and vegetables – especially by low-income households.

END NOTES The impact of COVID-19 has caused a lot of interest in foods that can positively affect health, such as immunity boosters and foods to combat stress. Dietitians and nutritionists should capture this momentum, as they have a huge role to play in providing the evidencebased facts and advising on the treatment of obesity during and beyond this pandemic.

More research is needed to investigate the impact of vitamin D supplementation and other antioxidants on COVID-19 risk and disease-related outcomes in otherwise healthy individuals.

The low-FODMAP diet has become a key dietetic intervention for the management of IBS, which affects 11% of adults.1 This article summarises what’s involved in the low-FODMAP diet and outlines some alternative therapies to consider when the diet is inappropriate for an individual.

FODMAP stands for fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols. It involves a three-stage approach to symptom management: 1 Restriction (where FODMAP intake is minimal) 2 Reintroduction (where FODMAPs are reintroduced to individual tolerance) 3 Long-term maintenance (where individual tolerance levels are adopted and tolerated FODMAPs are consumed again)

Clinical studies show that a lowFODMAP diet can significantly improve gastrointestinal symptoms, abdominal pain and quality of life in people with IBS.3 In fact, as many as 50-80% of people with IBS achieve adequate symptom relief following a low-FODMAP diet.4 FODMAPs draw water into the small intestine via osmosis and are fermented by gut bacteria in the large intestine, which can lead to IBS symptoms such as diarrhoea, wind, bloating and abdominal pain.4

The BDA guidelines state that the low-FODMAP diet is a secondline intervention that should be used following first-line advice to control symptoms.5 First-line advice should cover general healthy eating and lifestyle, limiting gut stimulants such as caffeine, fat and spicy foods, along with fibre modification based on the individual’s symptom profile and current diet.5,6

Clinical use of the diet has increased significantly since its inception at Monash University, Australia in 20042 (following years of research into the individual components of the diet). However, it is important that nutrition professionals are aware of potential downsides of this diet,7 and that IBS management is not a one-size-fits-all intervention.

NUTRIENT INTAKE People with IBS have a poorer quality baseline diet.8 Restricting certain foods and food groups during the FODMAP elimination stage increases the risk

Table 1: Types of FODMAPs (This list shows examples and is not exhaustive)

Oligosaccharides: fructans and Wheat, rye, lentils, chickpeas, baked beans, onion, galacto-oligosaccharides garlic

Disaccharides: lactose Lactose containing cow’s milk, sheep’s milk, goat’s milk, yoghurt, ice cream, soft cheese

Monosaccharides: excess fructose Honey, apples, mangos, cherries, pears, watermelon Mushrooms, cauliflower, some artificial sweeteners (sorbitol, mannitol)

Frances Ralph RD

Frances is an experienced Freelance Dietitian and Health Writer. Her specialist areas include gut health and the management of irritable bowel syndrome, including the lowFODMAP diet.

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

AYMES Shake Compact LessisMore

More protein, and more flavour!

A serving of great-tasting AYMES Shake Compact now contains up to 15.4g protein1, meeting ESPEN Guidelines2 for protein from ONS in just 2 servings. And all for less than £1!

With the addition of NEW Ginger flavour, patients can enjoy a wider range of flavours, supporting those suffering from taste fatigue or dealing with changes in taste.

ENERGY (KCAL) 315 - 320 PROTEIN (GRAMS) 15.0-15.4

Suitable for children (6yrs+)3 and adults

NEW!

ORDERFREEOFCHARGESTARTERPACKS FROM AYMES.COM ORCALL CUSTOMERSERVICE 08006785145

of a nutritionally inadequate diet.7 Restricting FODMAPs involves many food groups, including grains, dairy and fruit and vegetables, which could reduce intake of many macro- and micronutrients.9

Studies researching this have found reduced intake of key nutrients, such as carbohydrate, fibre, iron and calcium during the restriction phase of the diet.9 However, one 2019 study showed that when low-FODMAP dietary advice was delivered by a specialist dietitian, intake of most nutrients was not significantly impacted.8 NICE guidelines recommend low-FODMAP advice is only given by suitably qualified professionals,6 such as Registered Dietitians.

Key considerations to maintain nutritional adequacy of the restriction phase include: • ensuring appropriate food substitutions and proper reintroduction; • recommending low-FODMAP milk alternatives which are fortified with calcium (and other micronutrients); • ensuring fibre intake is optimised, eg, low-FODMAP fruit, vegetables, oats, wholegrains and fibre supplements; • special care taken in groups who already restrict certain foods, for example vegans, or those at higher risk of nutrient deficiency or malnutrition.

DIET DIVERSITY/QUALITY Exclusion diets, such as the low-FODMAP diet, can become repetitive due to so many restrictions. They may also decrease in quality and diversity, which can negatively impact the diversity of the gut microbiome.10

A 2019 study assessed the quality and diversity of the diet during FODMAP restriction (as instructed by a specialist dietitian) and found that diet quality, but not variety, was significantly reduced versus control diet.8 While the lowFODMAP diet can lead to symptom improvement, the risks of a long-term low-quality diet may lead to other health issues in the future.

MICROBIOME Fermentation of the prebiotic FODMAPs (fructans and galacto-oligosaccharides) by gut bacteria in the large intestine can lead to symptoms in people with IBS. However, this process is also important to feed and grow the gut microbiome.

Studies have shown a negative impact of a low-FODMAP diet on the gut microbiome, such as a significant reduction in faecal bifidobacterial concentrations.11 The significance of this for long-term gut health and symptoms in people with IBS is not known. As dysbiosis is common in IBS, it is concerning that the therapeutic diet could potentially worsen it. In one study, however, the addition of a specific multistrain probiotic ameliorated the negative impact of the low-FODMAP diet on gut flora.12

Other important considerations are the diversity and fibre content of the diet, ensuring FODMAPs are increased to tolerance following the restriction phase, to allow maximal prebiotic fermentation without significant symptoms.

COMPLEXITY The sheer complexity and number of foods that need to be restricted during the low-FODMAP diet (carbohydrates, fruits, vegetables, dairy products and most processed foods) can make it difficult to follow. Patients report it as “demanding”.13 Healthcare professionals must assess the educational level and ability of patients to understand and follow the diet. Stress also plays a key role in IBS via the gut-brain axis (GBA),14 so, following a difficult diet may add to this burden.

If necessary, the diet can be simplified for individuals, starting, for example, with single group exclusions such as lactose or wheat, or by cutting key FODMAP foods in the diet and building up as required until symptoms are satisfactory.15 However, these approaches are less well studied and may not provide such significant symptom reductions.

DISORDERED EATING A 2015 systematic review found greater prevalence of eating disorders in people with gastrointestinal disorders (including IBS). When these disorders are controlled by diet, this may be associated with symptoms and anxiety, which may involve the GBA.16

Prior to commencing a low-FODMAP diet, it is good practice to screen for past or present eating disorders, or disordered eating patterns. The dietitian should consider the role of the GBA and food beliefs on IBS symptoms. The low-

FODMAP diet is not intended to lead to weight loss and this may indicate excessive restriction or fear to reintroduce foods.

For patients with disordered eating, psychological therapies (discussed below) are more appropriate.7

RESOURCES The low-FODMAP diet requires commitment in terms of time, food preparation and the additional expense of free-from alternatives.17 This should be assessed and patients should be supported to minimise these difficulties. This can involve providing quick and easy recipes, cheap foods that are naturally low in FODMAPs (eg, potatoes and rice), lists of ‘safe’ preprepared foods (such as the King’s College London Suitable Foods booklet18) and smartphone apps (such as Monash or Food Maestro) that make the diet easier to follow.

ALTERNATIVES TO A LOW-FODMAP DIET Before considering alternative therapies, it is sensible to check whether first-line advice has been implemented and whether lower FODMAP load (without full restriction diet) is appropriate. It is also advisable to review current medications and, in collaboration with a patient’s GP, trial symptom-specific medications such as an antispasmodic for the control of diarrhoea. Other alternative therapies are discussed below.

Probiotics

Probiotic therapy is an interesting, yet sometimes controversial area of IBS management. A 2018 meta-analysis of 53 studies found that specific multistrain probiotics were effective for managing overall IBS symptoms,19 although more research is needed in this area. Current UK20 and US21 guidelines do not recommend probiotic use for the treatment of IBS due to limitations in the current evidence base. Regardless, probiotics are often desired by patients and considered safe. If trialled, they should be taken for four weeks at manufacturers’ guidelines20 whilst monitoring symptom response.6

Psychological and lifestyle therapies

Non-diet therapies can be helpful in the management of IBS symptoms alone or alongside dietary advice as part of a holistic management plan. NICE guidelines recommend increased activity (if levels are low) and use of regular relaxation techniques.6 Psychological therapies with best efficacy in managing IBS symptoms include cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and gut directed hypnotherapy, although others can also provide benefits, such as talking therapies and stress management.22 NICE recommends psychological intervention for those with refractory IBS (no response to diet, lifestyle or medication after 12 months).6

When compared with the low-FODMAP diet in randomised controlled trials, both a 12-week yoga programme and gut-directed hypnotherapy have been found to be equally effective.23,24 These should, therefore, be considered for patients who are unsuitable for or unwilling to input dietary advice to avoid risks discussed here. NHS availability is poor, so patients would usually be required to selffund these options, which can limit their use. Recent advances in technology have made them more accessible, such as free yoga on YouTube and apps that offer gut directed hypnotherapy (such as Nerva). However, these may differ from interventions used in the clinical trials.

CONCLUSION The low-FODMAP diet is an evidence-based dietary approach to IBS management, which is becoming widely used. It should only be delivered by suitably trained Registered Dietitians.25 The diet may not be suitable for all patients and may carry risks. Many of the risks can be mitigated with proper dietetic input and reintroduction of excluded foods. For clients who should not or cannot follow the low-FODMAP diet, non-diet therapies provide good alternative options, providing they are accessible.

More research is required into which patient groups best suit different interventions and also combinations of interventions for more holistic treatments (diet plus lifestyle/psychological). A holistic approach encouraging the patient to selfmanage their symptoms is essential to proper long-term symptom control.

To end on a quote from Peter Gibson, one of the founders of the diet: “Clinical wisdom is required in utilising the low-FODMAP diet.”7

HISTAMINE INTOLERANCE AND LONG COVID

This article outlines recent discussions around histamine intolerance and some long COVID symptoms.

Histamine is a chemical that is both made by the body and found in certain foods. It is an inflammatory substance produced by cells during an infection. It encourages an immune response to help fight off infection, thus is important to the human body.

HISTAMINE INTOLERANCE Approximately 1% of the world’s population has a histamine intolerance.1 It arises through an increased availability of histamine in the body and decreased activity of the enzymes that break down histamine. Histamine intolerance can cause symptoms such as diarrhoea, headache, asthma, rhinitis, hypotension, arrhythmia, hives, itching, flushing and other conditions.1 Symptoms can occur after a few hours up to a few days.2 These symptoms are similar to those reported by long COVID sufferers. Anecdotally, some who have tried a low-histamine diet claim it reduces their symptoms.

LONG COVID Long COVID is also referred to as ‘post-COVID syndrome’. It is defined as, ‘symptoms that develop during or following an infection consistent with COVID-19, continue for more than 12 weeks and are not explained by an alternative diagnosis’.3

Recently, scientists have been discussing the role of mast cell activation syndrome (MCAS) in COVID-19.4 Their theory is that long COVID symptoms could be triggered by MCAS, where the mast cells release histamine in response to a viral infection.5 Despite a lack of evidence around histamine intolerance and long COVID, some medical doctors are now suggesting trialling a lowhistamine diet to see if it improves symptoms.6

DIAGNOSIS OF HISTAMINE INTOLERANCE To date, there is no reliable test to diagnose histamine intolerance, also known as an adverse reaction to ingested histamine. Diagnosis is usually made through history and a three-step dietary adjustment.7 This would include the use of a food and symptom diary.

It has been suggested that the ‘gold standard’ for diagnosing a histamine intolerance is to have a clinical assessment with a medical doctor who is experienced in histamine intolerance (or MCAS). This may include other tests to exclude other conditions. This should be followed by a low-histamine diet for four weeks under the supervision of a Registered Dietitian. It is then recommended that a double-blinded placebo-controlled provocation test is carried out with histamine to establish its effects,1 normally done under medical supervision. However, there is currently no procedure for performing such tests.7

WHAT IS A LOW-HISTAMINE DIET? A low-histamine diet can be restrictive and time-consuming. Reports from the long COVID community suggest that people have struggled to adhere to it, alongside their debilitating symptoms. In addition, histamine levels in food can have a significant variation and are subject to the age of the food, the storage time and how food has been treated.7 This can cause issues establishing

Elaine Anderson RD

Elaine is a Freelance and NHS Dietitian with over 12 years of experience in a variety of areas. She has a personal interest in long COVID having had experience of it herself. In addition to her NHS work, Elaine runs Care 4 Nutrition, a workplace health and nutrition consultancy. She can be contacted via email: carefornutrition@ gmail.com or via social media.

care_4_nutrition

care4nutr

care4nutrition

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

Table 1: Examples of high-histamine foods1,8,9

High histamine foods

Cured, tinned/canned, processed meats such as Fish such as tuna, sardines, mackerel, herring salami, fermented sausage, fermented ham Fermented dairy such as aged cheese (Gouda, Camembert, Cheddar, Swiss, Parmesan) Soured dairy such as buttermilk

Fermented soy products such as miso and soy sauce Pickled/fermented vegetables such as sauerkraut Oranges, bananas, tangerines, pineapple, grapes Aubergine, spinach, broad beans and strawberries White and red wine vinegar, pickles, dressings Coffee, cocoa/hot chocolate, green tea containing vinegar, yeast extract Peanuts Alcohol

Citrus fruit, strawberries, pineapple Alcohol Tomatoes and tomato products Histamine-releasing foods9* Spinach Chocolate

*It is worth noting that there is still no evidence that histamine-releasing foods have a clinical significance.9

actual histamine content in foods. Table 1 gives examples of foods high in histamine. There are many food lists available on the internet and many have conflicting advice.

Some studies report that certain medications and alcohol can inhibit the enzyme diamine oxidase (DAO). This enzyme helps break histamine down in the body. Further research, however, is needed in this area.9

WHY IT IS IMPORTANT TO WORK WITH A DIETITIAN One of the main reasons for working with a dietitian is to ensure a balanced diet with adequate nutrients is being achieved. The lowhistamine diet can be extremely limiting and frustrating. The hope is that the diet may not be forever. Some individuals may be able to tolerate a certain amount of histamine in their diet after a period of time. Many may also need medications such as antihistamines or mast cell stabilisers to help manage symptoms, although further research is needed in the area.4

CONCLUSION Despite the lack of evidence around histamine intolerance and long COVID, healthcare professionals should respect a patient’s decision to trial a low-histamine diet, particularly when other treatments are still lacking. Some may have already tried lowering histamine-containing foods and may well have seen a benefit, but they will need additional support to ensure their diet is adequate. Dietitians can help decrease the possibility of long-term restrictive diets, which can lead to poor health outcomes and a reduced quality of life.7

MALNUTRITION AND THE GROWING IMPACT OF COVID-19

Malnutrition continues to be a complex global problem with multiple consequences for the individual. This article provides an overview of malnutrition and explores the growing impact of COVID-19.

The term ‘malnutrition’ includes both the deficiency and excess of macro- and micronutrients (i.e. energy, protein, vitamins and minerals).1 This can be expanded further to describe two broad common terms: 1 Undernutrition – includes stunting (low height for age), wasting (low weight for height), underweight and micronutrient deficiencies 2 Overweight/obesity – obesity and diet-related noncommunicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases (heart attack and stroke), some cancers and diabetes2

In the UK, it is estimated that over three million people are affected by undernutrition with 1.3 million over the age of 65 years.3 The term ‘malnutrition’ is often used synonymously with ‘undernutrition’, which will be the focus of this article.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)1 defines malnutrition in terms of undernutrition using the following criteria: • A BMI of less than 18.5kg/m2 • Unintentional weight loss greater than 10% in the last three to six months • A BMI of less than 20kg/m2 and unintentional weight loss greater than 5% within the past three to six months

CONSEQUENCES OF MALNUTRITION The effects of malnutrition are widely researched and broadly associated with frailty, sarcopenia and poor health outcomes.4 Malnutrition is complex and can affect the function of every organ system in the body.5

Muscle function

Loss of muscle and fat due to weight loss can affect mobility with an increasing risk of falls. The muscles of the heart and lungs can also be affected leading to a reduced cough which may delay recovery from respiratory tract infections.

Joanna Injore RD

Joanna is an experienced Dietitian who has worked extensively in the NHS. She works at Macmillan Cancer Support and is the owner of JI Nutrition providing private 1:1 nutritional consultations and bespoke services for businesses.

www.jinutrition.co.uk

ji__nutrition

JInjore

Gastrointestinal function

Nutrition is needed to preserve the gut function and chronic malnutrition

Figure 1: Malnutrition – a problem of deficiency and excess

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

Undernutrition

Malnutrition

Overweight/obesity

At-risk groups

Adults over 65 years (particularly those in care homes)

Adults with long-term conditions, eg, diabetes, renal disease, chronic lung disease3

Adults with chronic progressive conditions, eg, cancer or dementia3

Substance misusers

Social risk factors

Social isolation

Poverty

Anxiety or low mood, which can limit appetite and interest in food

Limited access to culturally appropriate meals, eg, whilst in hospital or care home

Physical risk factors

Difficulty eating due to poor dentition, poor oral hygiene or illfitting dentures Impaired swallow function or painful swallow due to treatment or disease Anosmia (loss of smell) or dysgeusia (taste changes) leading to a reduced appetite

Physical limitations causing difficulty in preparing meals

Reduced mobility or access to obtain food Physical side effects of disease or treatments, eg, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea or pain

can cause changes in villous architecture and intestinal permeability, causing reduction in the colon’s ability to reabsorb water and electrolytes.5

Immunity and wound healing

Malnutrition can increase the risk of infection due to reduced cell-mediated immunity and impaired wound healing is well documented.5

Psychosocial effects

Malnutrition can result in psychosocial effects such as depression, anxiety, poor body image, altered sleep patterns, isolation and self-neglect. The wider burden of malnutrition in terms of costs to health and social care is significant. Malnourished adults have prolonged hospital stay, present more regularly to their GP and make up 30% of hospital admissions.6

RISK FACTORS FOR MALNUTRITION Table 1 illustrates the common risk factors for malnutrition divided into three categories: particular at-risk groups, social and physical factors.6

Disease-related malnutrition is multifactorial as a result of the treatment of the disease or the disease itself, which causes the following to occur: 1 Reduced dietary intake 2 Reduced absorption of macro- and or micronutrients 3 Increased dietary requirements due to increased energy expenditure

Some of the social and physical factors can also be present, further compounding the risk of malnutrition. Malnutrition, for example, is highly prevalent in older patients with cancer who are undergoing anti-cancer treatments such as chemotherapy.

THE IMPACT OF COVID-19 Malnutrition has been an ongoing global issue but, unfortunately, this has been compounded by the emergence of COVID-19.

COVID-19 has stimulated a global social, economic and medical crisis and presents a real threat to nutritional status, particularly in the most vulnerable groups such as children and older adults. In January 2021, the UK entered its third lockdown, which, yet again, presents further enforced social isolation. Adults over 65 years of age are already in the at-risk group for malnutrition and for severe effects of COVID-19 with poor prognosis.7

Ongoing guidelines to stay at home will continue to limit this particular group’s access to a wide variety of food creating challenges for individuals to maintain a healthy diet.8 The impact of ongoing social isolation is likely to induce negative emotions such as stress, sadness

and distress, all known to be associated with reduced motivation or desire to eat,6 further compounding the risk of malnutrition. Limited regular contact with friends or family may also mean that possible signs and symptoms of malnutrition, such as weight loss, loss of appetite and fatigue, may go unnoticed.

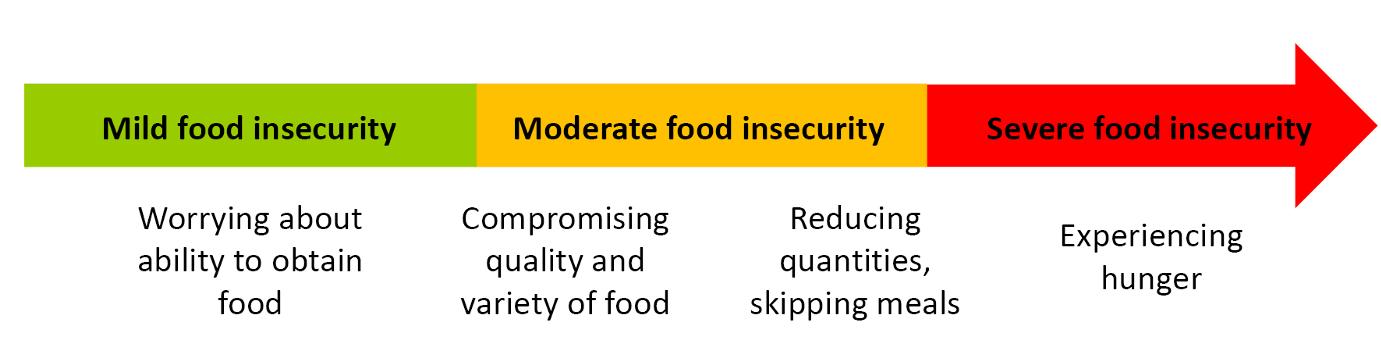

The economic effect of COVID-19 has been hard hitting, with a surge in redundancies and an increasing rate of unemployment posing a real threat of food insecurity. Food insecurity is a ‘limited access to food due to lack of money or other resources’.9 The level of food insecurity can be measured by the Food Insecurity and Experience Scale (FIES) which ranges from worrying about obtaining food to experiencing hunger (see Figure 2).

A recent study10 has illustrated that COVID-19 has exacerbated food insecurity for vulnerable groups such as the unemployed, adults with disabilities, families with children and members of the black, Asian and other minority ethnic groups (BAME).10 These groups are not only experiencing food insecurity due to limited income, but also due to environmental factors such as poor availability in the shops or being unable to go out due to self-isolation.10

The COVID-19 virus has appeared to disproportionately affect low income and ethnic minority groups, which, along with the greater risk of malnutrition, may be contributing factors to poorer outcomes and severe disease.11

SUMMARY Malnutrition continues to be a huge global problem and, with the ongoing impact of COVID-19, is likely to affect more of the population. The risk of malnutrition is already complex and multifactorial without COVID-19, but the pandemic has created new problems of food insecurity for those already vulnerable to health inequalities. So now more than ever it is vital that we identify those at risk of malnutrition. Malnutrition should continue to be a consideration for all healthcare professionals and usual practice should be adapted to allow screening to take place remotely or by patients or carers themselves.

www.NHDmag.com

Make the most of your NHD Community!