21 minute read

Nutrition & hydration

NUTRITION AND HYDRATION IN THE ELDERLY

Nutrition plays a vital role in the health of older adults, yet one in seven 65-year-olds and over are estimated to be malnourished.3 The importance of good nutrition and hydration in our ageing population can’t be stressed enough. Here, we look at the challenges faced and consider positive interventions for improving nutritional status.

Advertisement

The world’s population is ageing. By 2050, a quarter of Europeans are expected to be over the age of 65,1 and this age group already comprises 18% of the UK population.2 Many elderly people are failing to sufficiently meet their nutrient requirements through dietary intake, and an estimated 46% of those in long-term care facilities face current or impending dehydration.4 The need for ensuring adequate nutrition and hydration in the elderly is recognised by the World Health Organisation as an issue of paramount importance,5 particularly since the current COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated such problems.

The UK’s National Diet and Nutrition Survey data reveals that older adults are consuming high amounts of free sugars and saturated fat, whilst daily average fruit and vegetable consumption is below the recommended five a day. Furthermore, this age group often fails to consume adequate amounts of oily fish, total energy, vitamin D, riboflavin, iron, B6 and B12.1,2 Inadequate intakes of various nutrients, coupled with the unique daily challenges that prevail as we age, highlight the need to promote healthy dietary habits among the elderly.

THE IMPORTANCE OF NUTRITION AND HYDRATION IN OLDER ADULTS As we age, we are typically less mobile and muscle and bone mass decrease. Subsequently, basal metabolic rate decreases. However, maintaining a nutrient-dense diet is still of critical importance. Adequate nutrition can prevent, modulate, or ameliorate many age-related diseases and conditions and, as such, adequate nutritional status can benefit the health and quality of life for older adults.6,7

Malnutrition is associated with longer hospital-stay duration, cognitive impairment, hypotension, infections and mortality, whilst prolonged malnutrition can cause further deterioration of nutritional status due to lack of interest in eating.6,8 Some nutrients are also particularly important for maintaining optimum functioning of the immune system, in which changes occur as we age.1 Furthermore, malnutrition has been associated with depression in older adults; suicide rates are twice as high amongst 80- to 84-year-olds than in the general population.9

Although older adults tend to be more vulnerable to underconsumption in institutional care, obesity is more prevalent in free-living older adults and can contribute to existing health conditions, such as being less mobile, sarcopenia and frailty.1,10 Additionally, dehydration can lead to functional impairment and dizziness and subsequently increased risk of falls,

Kelly Fleetwood MSc ANutr

Kelly is a Registered Associate Nutritionist and Brand Manager in the food industry. Alongside improving the nutritional profile of well-loved food brands, Kelly offers freelance consultancy, with specialist areas in nutrition for vulnerable groups, the gut microbiome and nutrigenomics.

www.kellylightnutrition.co.uk

kellyinthekitchen

kitknutrition

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

The food industry also has a role to play in the nutritional status of older adults; making packaging easier to open and to read . . . for example, can help negate food avoidance.

alongside prolonged hospitalisation stays, pressure sores and constipation.3,11 Nutrition and hydration in older adults, therefore, requires sufficient attention.

NUTRIENTS OF PARTICULAR SIGNIFICANCE Research suggests that some nutrients are of particular significance for older adults: • Protein requirements are a highly debated aspect of nutrition in the elderly and consumption is important for functions such as maintaining muscle mass, wound healing and illness recovery.6 • Vitamin D plays a role in preserving muscle mass, strength and physical function,12 alongside calcium for preserving bone mineral density and fracture prevention.6 • B6, folic acid and B12 all play a role in homocysteine metabolism – elevated homocysteine levels are associated with cardiovascular disease, impaired cognitive function and dementia.6 • Fibre is important for preventing constipation and for providing an overall enhancement of the gut microbiome – bacterial diversity and beneficial bacteria decline as we age, so fibre may offer a novel solution to many aspects of health in the elderly.1,3,9 • Omega-3, due to its anti-inflammatory properties, protects against heart disease and helps those who have already experienced a

heart attack. Omega-3 may help to alleviate symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis alongside preserving eye health, preventing cognitive decline and improving immune function.13 • Furthermore, magnesium, selenium and calcium might be important nutrients in treating and/or preventing sarcopenia, though more research is needed in this area.14

CHALLENGES FACING OLDER ADULTS As we age, we experience many physiological changes that affect the way we perceive, consume and digest food. Firstly, poor vision and changes in taste and smell of food can hamper preprandial food cues and lessen the appeal of food.8 Alongside swallowing difficulties experienced by many older adults, reduced saliva and thus a dry mouth can also occur (known as xerostomia), which can ultimately lead to avoidance of certain foods, particularly those which are hard or sticky.6 Additionally, use of multiple medications can induce nausea and affect appetite, exacerbated by a deregulation of hormones ghrelin, leptin and cholecystokinin, which can often occur in older adults.1,6,15 There can also be a reduction in gastric acid secretion, as well as slower gastrointestinal motor function and food transit, resulting in prolonged postprandial satiety and, hence, reduced food intake.1,6 Furthermore, absorption, storage, distribution and utilisation of certain nutrients can become limited and can be the case for vitamin D, B vitamins, iron and calcium.3,13,15

The ability to stay sufficiently hydrated also becomes more difficult as we age. This is in part due to reduced renal function, which can impair fluid balance, and a reduced thirst sensation, which is more prominent in those with Alzheimer’s disease or stroke.17 Cognitive impairment can mean that some older adults forget to drink, whilst incontinence and the need for toilet assistance can lead to anxiety surrounding drinking.17

In addition to physiological changes, older adults are more likely to receive a low income and live alone, both of which are associated with compromised food intake.1 The ability to source and cook food also becomes more difficult due to loss of dexterity and strength, further jeopardising the likelihood of adequate nutrient consumption.

IMPROVING NUTRITION AND HYDRATION A multifaceted approach is required in order to improve nutritional and hydration status in older adults. It is particularly important to pay attention to those residing in long-term care, sheltered housing and hospitalised patients. Prevalence of malnutrition and dehydration are believed to be up to 50% higher in such environments due to increased likelihood of cognitive and functional impairment, as well as health conditions that place additional demands on the body and a reliance on others for care.3,15,18 As such, it is recommended that relevant staff are trained to recognise the importance and detection of malnutrition and dehydration in the elderly and work to prevent its occurrence.

There is some disagreement surrounding a gold standard measure of malnutrition in hospitalised patients, hence further research in this area would be beneficial;8 however, BMI, haemoglobin and total cholesterol are useful biomarkers.19 Signs of dehydration include dry mouth, lips and tongue, sunken eyes, dry and inelastic skin, drowsiness, confusion, hypotension and concentrated urine.16

To encourage increased food intake, mealtimes should be taken alongside other residents, as research suggests social atmosphere can enhance the enjoyment of food in older adults.6 Positive interventions include the following: • Food should be varied and palatable for older adults who have sensory ailments, and involvement in food preparation where possible may help stimulate appetite.6 • Meal deliveries for those in sheltered housing can alleviate challenges in sourcing and cooking food. • Providing preferred and constant available fluids and assistance with drinking could help ensure older adults are adequately hydrated.16 • Any nutrition education programmes should incorporate a positive, realistic attitude towards food and mealtimes, to help ensure longer-term success.20 • Incorporating elements of physical activity and resistance training may further enhance positive outcomes.10

THE ROLE OF THE FOOD INDUSTRY AND RESEARCH The food industry also has a role to play in the nutritional status of older adults; making packaging easier to open and to read (by featuring a sizeable font, for example) can help negate food avoidance.6 In terms of diet composition, it is most widely suggested that the Mediterranean diet is most suitable for meeting the nutrition requirements of older adults.4 Supplement products may be of benefit to some older adults when food intake is limited, although this requires support from qualified healthcare professionals and can be expensive.18

More research is needed to identify appropriate elderly-specific requirements of certain nutrients.21 Most macro- and micronutrient recommendations for older adults are currently the same as those for younger adults, despite indications that requirements may change as adults age. For example, vitamin D requirements may be higher in the elderly due to reduced sunlight exposure,6 and protein requirements may be higher than those currently provided. More randomised controlled trials of sufficient quality will be beneficial in improving our understanding of associations between nutrition and health in older adults.

CONCLUSION Nutrition and hydration are important factors in the health and quality of life of older adults. This population group is faced with several physiological and socioeconomic challenges that make malnutrition and dehydration more likely. As such, better awareness, detection and preventative measures are required in settings where such conditions are most prevalent. The food industry might also play a role in making food preparation more accessible to the elderly, and further research on elderly-specific nutrient requirements will be beneficial.

Bessie Brumble RD

Bessie is a fulltime Specialist Diabetes Dietitian in the NHS, with an interest and background in mental health. She is currently studying for her postgraduate diploma in Diabetes, which she hopes will lead onto a Masters.

bessiedietitan

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

CHOLESTEROL: THE GOOD, THE BAD . . . OR THE ‘LOUSY’

Working with patients with raised cholesterol levels can be challenging. This article gives an overview of cholesterol and its impact on the body, along with recommendations and dietary interventions for reducing CVD risks.

Cholesterol is a type of fat also known as a lipid. The waxy substance plays an important role in the body for the production and structure of cell membranes, steroid hormones, bile acids for fat absorption and vitamin D.1,2 To transport around the body, lipids attach to proteins forming lipoproteins. There are different types of cholesterol, defined by their different structures and actions within the body. Arguably, the most commonly referred to are lowdensity lipoproteins (LDL) and highdensity lipoproteins (HDL).

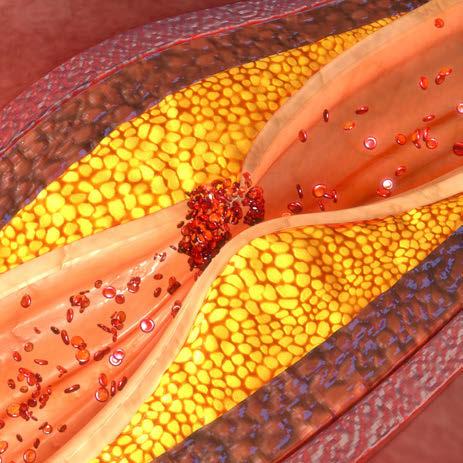

LDL are referred to as the bad or ‘lousy’ cholesterol. They have large lipid molecules, which provide for the actions named above, and deposit excess in the arteries. This depositing then results in the formation of atherosclerotic plaque, commonly termed to patients as the furring up of the arteries, which contributes to cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). On the other hand, high density lipoproteins (HDL) are often referred to as good or healthy cholesterol. They have a much larger protein molecule and a main function to transport cholesterol away from the cells and out of the arteries and to the liver. Here they can be broken down and removed from the body.3 Another type of cholesterol is triglycerides, which will be mentioned later.

As we rely on cholesterol for a range of important bodily processes, it should come as no surprise that the body is able to produce it. This rather complex process occurs mainly in the liver and intestines. And whilst I’m not going to go into the detail of the pathways, I will tell you that the process is sensitive, easily disrupted by hormones, lifestyle and other physiological variables. A clinical example of cholesterol disruption can be seen in insulin resistance (commonly seen in Type 2 diabetes and polycystic ovarian syndrome), whereby the body’s cholesterol absorption efficiency is low and synthesis high, resulting in abnormal levels.2

High cholesterol (or abnormal lipids) causes a significant impact on public health through increased risk of CVD, a leading cause of death in the UK. Abnormal lipids are commonly asymptomatic, posing the threat that many people can live without awareness or intervention for many years.

It is documented that deaths from CVD have hugely declined since the 1980s, but this is thought to be due to advances in medical care.4 In the UK, selective screening in people identified as at risk (based on age, weight and comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes) is recommended. Table 1 shows cholesterol targets from NHS Choices.5

This is just a guide. The levels aimed for might be different and individuals should ask their doctor or nurse what their levels should be.

Table 1: Target levels for cholesterol5

Result

Total cholesterol

HDL (good cholesterol)

LDL (bad cholesterol)

Non-HDL (bad cholesterol)

Triglycerides

Healthy level

5 or below 1 or above 3 or below 4 or below 2.3 or below

SACN recommendations on saturated fats and health (2019)4

S.24 It is recommended that: • the dietary reference value for saturated fats remains unchanged: the [population] average contribution of saturated fatty acids to [total] dietary energy be reduced to no more than about 10%. This recommendation applies to adults and children aged five years and older. • saturated fats are substituted with unsaturated fats. More evidence is available supporting substitution with PUFA than substitution with MUFA.

S.25 This recommendation is made in the context of existing UK Government recommendations for macronutrients and energy. S.26 It is recommended that the Government gives consideration to strategies to reduce the [population] average contribution of saturated fatty acids to [total] dietary energy to no more than about 10%.

Risk managers should be mindful of the available evidence in relation to substitution of saturated fats with different types of unsaturated fats and ensure that strategies are consistent with wider dietary recommendations, including trans fats.

DIETARY INTERVENTIONS

Dietary cholesterol

As mentioned above, the cholesterol producing pathway in the body is sensitive. A common thought is that our cholesterol levels are a direct reflection on the cholesterol that we eat; however, this isn’t quite true. Cholesterol-containing foods such as eggs, shellfish, meat and dairy are understood to only contribute to around 15% of the cholesterol found in a person’s blood.6 It’s thought that on average we consume less than 300mg/day, which Heart UK recommends is the dietary cholesterol limit for people with CVD risk factors. For people with familial hypercholesterolemia (genetic high cholesterol), the recommendation is lowered to 200mg/day. To put it in to perspective: • Chicken, pork and fish are generally lower than 100mg per 100g serving. • One small egg serving is around 185mg. • Prawns are around 210mg per 140g serving. • Offal varies, however liver and kidneys are higher per 100g serving than shellfish.7

Dietary fat

Although dietary cholesterol does not have a significant impact on blood cholesterol, dietary fat does. In 2019, the Scientific Advisory Committee on Nutrition (SACN) reviewed the evidence between saturated fats and health outcomes in the general UK population. This backed the historic view that reducing saturated fats reduces the risk of CVD and coronary heart disease events, lowers total cholesterol, LDL and HDL cholesterol and also improves indicators of glycaemic control. SACN recommends saturated fat (SF) is limited to 10% total daily fat intake in people over five years old. All other fats should come firstly from polyunsaturated and secondly monounsaturated sources. SACN also advises government towards public health policies that enable the population to meet the recommendations. See box above.

Fibre

Strong evidence suggests that increased intakes of total dietary fibre, particularly from grains, are cardioprotective. Oat bran and isolated

β-glucans have been associated with lower total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, triacylglycerol concentrations and lower blood pressure.8 NHS Choices agrees with the beneficial effect of fibre for cholesterol and overall CVD risk reduction. To achieve the recommended daily intake of 30g, dietary sources to include are: wholemeal bread, bran and wholegrain cereals, fruit and vegetables, potatoes with their skins on, oats and barley, pulses, nuts and seeds.9

Cholesterol-lowering products

Current national guidance does not recommend plant stanols and sterols in the prevention of CVD.10 This is contrary to much evidence in their support. For example, the British Heart Foundation reports that there is evidence to support an 8-12% cholesterol reduction, but that plant stanols and sterols are not recommended in guidance as there isn’t the evidence for reduced risk of heart attack and stroke.11 I often have patients wanting to start these products and after providing the evidence, would advise them to speak with their GP and request for bloods to be monitored.

EXERCISE AND ACTIVITY Keeping active is another huge factor in supporting healthy cholesterol levels. Being active increases HDL and reduces LDL.12 The Government recommends a minimum of 150 minutes of moderate intense activity or 75 minutes of intense activity per week for adults. Recommendations for young adults and children differ.

Triglycerides (TG) are stored in our body fat and are understood to be very responsive to our lifestyle. A person with high TG, high body fat and low activity levels is likely to find behaviour change to address these areas will result in significant TG reduction. Nutrition considerations also include following fat swap guidance (above), reducing added sugars and moderating alcohol.13

MEDICATION INTERVENTIONS Cholesterol is more complex than lifestyle behaviours alone. Statins are the most common drug prescribed to lower cholesterol. They are incredibly effective in reducing CVD risk by reducing LDL cholesterol by 30-50%, reducing triglycerides and increasing HDL. Based on their action on the full lipid profile, statins are widely recommended to people at risk of CVD.14 In my experience, it is very common that patients have heard scare stories and feel stigma towards statins. This regularly results in people not accepting the therapy. Helping to remove the stigma and providing education on the physiology of cholesterol can result in increasing acceptance.

CONCLUSION When working with clients with raised cholesterol, it is vital to remember that the reason for management is to reduce CVD. Cholesterol is one element of CVD risk and where dietary intervention isn’t responding, there are successful medications available to add an additional layer of support.

Ursula meets:

BELINDA MORTELL

Healthcare Development Manager, Danone Nutricia Accountant

BDA England Board Member

Ursula Arens RD

Belinda and I shared paths for a year on the BDA Communications and Marketing Committee: she chairing with competence; I attending with interest. But that was five years ago. Today we meet phone-to-phone. The world has changed and we have changed, but it is lovely to catch up and hear about Belinda’s unusual dietetic career, which started in accountancy.

“I did maths and extra maths at A-level. Careers advice from a teacher matched with my own ambitions to be earning £££s, made this profession an obvious choice,” she said. Belinda chose to study in Edinburgh, which offered fast track certification, and then enjoyed a few accountancy jobs in Stevenage and London. “It was working for Unilever that gave me a taster into the world of food.”

Then to Dublin, because Dublin was where her husband got a job. “I had been thinking about there being more to life than financial accounts. I considered possible health careers and discovered the degree in Human Nutrition and Dietetics offered at Trinity College. This was a difficult course with lots of medicine modules, but I was lucky in that two places were reserved for ‘mature’ students. I had to jump several hurdles of several fierce interviews, and was lucky to be offered a place.”

Belinda graduated with both a degree and her firstborn. “My final student placement was on a renal ward, which did not match feeling great in the late stages of pregnancy. On one occasion I had to leave because of feeling queasy. I will always remember the words of a kind colleague. She said that feeling unwell during pregnancy never required an apology.”

Another spousal job move allowed her to enjoy some time in Gibraltar and, in any case, two small children kept her busy. But North Wales was home, and after many years away, Belinda was thrilled to return. In order to work as a dietitian, she had to obtain HCPC registration, which required the submission of forests of paperwork and took nearly a year. The time and complexity of registration was a frustration. Belinda was able to do some basic dietetic support work for Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board at Wrexham Maelor Hospital, and so was already part of the team when her HCPC registration was granted.

The first dietetic job was a steep learning curve. Belinda got some time in lots of different clinical sections and was always very busy. “There never seemed to be enough time to get to the bottom of the daily to-do list,” she said. Having gained promotion to band 6, Belinda then took on two service improvement projects, looking at weight control support and care homes. “It was interesting to get deeper insights into these areas, but I felt frustrated that there was then little opportunity to enact changes, because, of course, it is all linked to the availability of funding.” The role of dietitians in individual counselling

Ursula has a degree in dietetics and currently works as a freelance writer in Nutrition and Dietetics She enjoys the gifts of Aspergers.

Our F2F interviews feature people who influence nutrition policies and practices in the UK.

REFERENCES Please visit: nhdmag.com/ references.html

INSPIRED BY BREAST MILK

Breast milk is best for preterm infants and offers an array of benefits.1 However, when breast milk is not available or is in limited supply, a preterm formula that is nutritionally closer to breast milk offers the best alternative.2

Over 60 years of research in preterm nutrition

Breast milk has inspired the development of the prebiotic blend scGOS:lcFOS (9:1) • 90% short-chain galacto-oligosaccharidess (scGOS) • 10% long-chain fructo-oligosaccharides (lcFOS)

ScGOS/lcFOS (9:1) is an extensively researched prebiotic compound3

30 clinical trials 55 publications

Benefits of scGOS/lcFOS demonstrated in clinical trials in preterm infants

Reduces the prevalence of clinically relevant pathogens5

Results in significantly softer stools and increased stool frequency4

Significantly reduced stool viscosity and accelerates gastrointestinal transit time6

Stimulates growth of bifidobacteria4 May improve enteral tolerance7

Nutriprem 1 and 2 contain prebiotic oligosaccharides to support gut health4–7

Scan the QR code to learn more about the benefits of prebiotics in a preterm formula Healthcare professional helpline 0800 996 1234 nutricia.co.uk @NutriciaHCPUK

IMPORTANT NOTICE: Breastfeeding is best. Nutriprem human milk fortifier, nutriprem protein supplement, hydrolysed nutriprem, nutriprem 1 and 2 are foods for special medical purposes for the dietary management of preterm and low birthweight infants. They should only be used under medical supervision, after full consideration of the feeding options available including breastfeeding. Hydrolysed nutriprem, nutriprem 1 and 2 are suitable for use as the sole source of nutrition for preterm and low birthweight infants. Refer to label for details.

for those with obesity has been reduced, and there is much greater use of commercial group support organisations. Targeting and effective use of dietetic time validates this decision, but we both feel sad that while population obesity trends continue to boom, dietetic expertise is channelled mainly into complex cases and bariatric surgery procedures.

In 2017, Belinda noticed a job advert for an industry post requiring dietetic expertise. There were two augurs of fate supporting her application. It was her 40th birthday and the post was in North Wales. “I was delighted, after several rounds of interviews, to be offered a job with Danone Nutricia.” Going into a sales job supporting specialist nutritional products allowed her to use her dietetic expertise, but perspectives were very different from her previous NHS job. “Of course, I know lots of dietitians in the area. But working in industry means that you have moved to the other side of the table,” said Belinda. After lots of training, Belinda started in the Early Life Nutrition division. She is now Healthcare Development Manager for Danone Nutrition, and enjoys the balance of contacts with both researchers and healthcare practitioners, supporting both towards improving nutrition care to those at risk of malnutrition.

Belinda is looking to start a Masters degree in Research, to look into prescription practices for nutritional products. Current systems balance budget-holder restraints and clinicalpractice judgements, but are there better ways to target nutritional products within funding limits? Should dietitians have greater controls over these products? Belinda has many questions and perhaps after her Masters project, she will be able to promote evidenced answers.

Dietitians need to become more confident and assertive, and good practice is about having expertise and sharing this with colleagues. Being an active member of a professional group is one way to do this and Belinda is currently on the England Board of the BDA. “There have been some changes to representation within the BDA, to the current system of a greater diversity of directors, bringing in a wider base of expertise,” she said. Because the England Board represents such a large geographic terrain it is a challenge to pull together cohesive themes. “But the England Board has a great mix of expertise, and I am sure we will produce some good projects to advance the profession.”

Belinda has a brisk can-do-ness about her, and she obviously enjoys the financial risks and benefits that industry projects allow. Of course, most dietitians love numeric detail and being highly organised problem-solvers. But Belinda, more so: the accountancy heart still beats loud.