THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

This short book is a personal recollection to celebrate thirty years of Bampton Classical Opera. Its character is, I hope, cheerfully anecdotal and is far from being an academic study – that weightier version remains to be written. Produced to accompany a 30thanniversary exhibition at the Bampton Community Archive, this account is unashamedly Bamptoncentric, but also touches on many activities of the company across England. Demand on space means that many who deserve honourable mention are omitted, and what may seem surprising is that only a handful of the many musicians whose skill and enthusiasm have brought us such success are named. Our website currently lists 27 conductors, 16 directors and 103 solo singers, to say nothing of the many who have sung in choruses or the hundreds who

have played for us in a variety of orchestras – our largely locallydrawn Orchestra of Bampton Classical Opera, the periodinstrument Bampton Classical Players, the London Mozart Players and CHROMA, as well as other groups. We have identified and promoted numerous outstanding young musicians at an early stage in their careers. If you glance at the websites of, for example, conductors Edward Gardner and Christian Curnyn, directors Alessandro Talevi and Harry Fehr, singers Rebecca Bottone, Paul Carey Jones, Alessandro Fisher and Benjamin Hulett – to name just a small handful - you will realise how Bampton musicians have gone on to outstanding national and international careers, something of which we are immensely proud.

I’m often asked, “How did it all start?”, and that is the best place to begin.Alessandro Fisher (Count Bandiera) in Salieri’s The School of Jealousy, 2017

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

“O ruddier than the cherry!”

“What a brilliant idea. ‘Bring a chair’, said the ticket. That way you couldn’t complain of a sore backside. Mind you, there were the surroundings to distract from any discomfort: the Deanery Garden in Bampton is a really beautiful place for outdoor music. A courtly hedge makes a natural set and behind the audience the house seems to hold the sound in –the acoustics were amazingly good.”

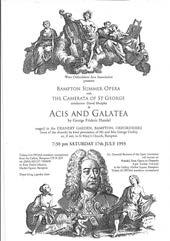

Giles Woodforde, writing the first press review (Oxford Times, 23 July 1993) for what was then called Bampton Summer Opera, opened with a flourish, picking out several crucial aspects of our first opera which remain true thirty years later. When preparing a simplystaged opera at the Deanery in 1993, we decided to save the expense of providing seating and so create a more relaxed and welcoming event (“accessible” would be current jargon, not a term

much used in the 1990s). A lovely lawn, a sunny evening, the swifts swooping overhead and glorious baroque music: surely just the right ambience for sprawling on a homely garden chair rather than on a hard plastic one from the village hall.

Besides, there was little purpose investing in infrastructure for what was intended as a one-off event. Handel’s glorious pastoral ‘serenata’, Acis and Galatea, composed in 1718 for Cannons, the

Handel, Acis and GalateaThe beautiful Deanery and garden

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

of the 1st Duke of Chandos, was our repertory choice – one of the most affecting and consistently performed of all English ‘operas’.

As with many of life’s better inventions, Bampton Summer Opera came about in response to a wifely nudge. Gilly French (a full-time chemistry teacher) had modest ambitions as an operatic soprano, but somehow the casting call from Covent Garden never arrived… She longed to sing Handel’s Galatea, but we realised we would have to put it on ourselves. We had recently enjoyed an open-air concert in a lovely Gloucestershire garden, which encouraged us to think along similar lines. We were aware of the grander opera at Garsington Manor, the other side of the county, but that was already established as a larger affair, with a smart dresscode which we were disinclined to emulate.

I had recently joined the committee of West Oxfordshire Arts Association which at that time hoped to become more broadly based than its remit of the visual arts: an al fresco music event was readily seized upon as an event which might delight both the local community and attract others from outside.

Trevor Milne-Day was Chairman and helped steer the project

through months of planning, committee discussion and at times disagreement.

Gilly and I were confident we could gather musicians to sing and play, but there were a host of other problems and issues to be solved. A suitable venue, publicity, tickets, lights, music stands, scenery and costumes? And – the biggest question, of course – how would

costs be covered?

Several in Bampton, especially members of the active Drama Group, offered advice, expertise and contacts. Whilst considering several venues, the lovely Deanery garden easily won - and being adjacent to the capacious medieval St Mary’s Church, we would have a wet-weather venue if required. The Deanery owners, George and Deirdre Dudley, were quick to agree, and there seemed to be a precedent of opera having being held there under a previous owner in the 1960s. We tried out the acoustics on the spacious lawn which indicated that we should perform facing the house, with the splendid curved yew hedge behind, forming an embracing backdrop. We didn’t consider building a stage, reckoning that the beauty of the garden and its appropriateness to the ‘pastoral’ myth of Acis and Galatea required no scenery other than a few focal props. One of these was an old shop mannequin that I transformed

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

into a pseudo-classical statue with papier-mâché: we christened her ‘Barbie’, and she went on to ‘perform’ in several of our early operas and even qualified for a biography in the 1997 programme booklet – “she is noted for her geological flexibility”. Elegant period costumes for the soloists were hired at some expense, with the non-acting chorus simply lined up in black.

Gilly and I set about finding singers. We selected a London friend, bass Peter Johnson, as the raging Cyclops Polyphemus, and tracked down two young tenors for the lyrical shepherd roles of Acis and Damon – John Virgoe and Howard Branch. A chorus of 13 were mostly friends and amateur singers, and we gave walk-on parts to Amy Mills and Christopher Allinson, children of Bampton friends. For the small orchestra, our friend Felicity Cormack, whose multi-tasking talents continue to be put to use to this day, contacted a recently-

formed Thames Valley ensemble, the Camerata of St George, who were players on ‘period’ rather than modern instruments. The invitation letter to players cheerfully stated that “We can offer travelling expenses, overnight accommodation and evening meals but unfortunately no fee will be available” – although, in the end, musicians were paid £50

each. Philip Needham was stage director and David Murphy was conductor. Jonathan Katz played harpsichord, which we hired from Gobles in Oxford, a somewhat risky undertaking given that there was no protection from the sun.

naturally concerned about costs, but Trevor led a successful fundraising drive including a £500 grant from the Joyce Grenfell Memorial Trust, a wonderful small charitable trust which has remained loyal to us ever since.

The date was fixed for a single performance in the Deanery garden on Saturday 17 July. WOAA was

Trevor persuaded several local businesses to donate to our cause –Abbey Properties, Burford Garden

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Centre, Castle Vineyards, Red Lion Bookshop in Burford and Sherlocks Dry Cleaning. A number of Bamptonians became our first ‘Friends’, including Rosemary Colvile and Susan Phillips. Many others locally helped with aspects of administration, production and front-of-house, including Libby Calvert, Sarah Edwards, Tom Freeman, David Mills, Richard

Morby, Wendy Nichols, Ernest Rosengard, Pat Smith and Margaret Williams. A jolly bar was provided by Bothy Vineyard at Frilford Heath. The programme leaflet was typed at home and photocopied, although the poster was half word-processed – these were very early days for home publishing. To add an educational element we invited Donald Burrows, Professor

of Music at the Open University and a renowned Handel scholar, to give a lecture in the WOAA gallery the previous week.

Fortunately the weather was fine and there was no need for recourse to the church. Woodforde’s review mentions approvingly the interruption of a “jet-powered roar from nearby Brize Norton airbase” which accompanied the slaying of Acis with “a cardboard stone” (I still remember constructing that somewhat impotent prop). The Dudleys’ prize collection of rare peacocks, corralled in their nearby enclosure, behaved themselves. Galatea’s final aria was rather drowned out by a spectacular pair of massive Roman candles which we used to represent the “bubbling fountain” into which the dead Acis is transformed – in 1993 it was surprisingly difficult to acquire fireworks outside November, and these had to be handed over to us discreetly in a brown paper bag in a Bicester car-park in the middle

of June. We remembered to ensure that the church clock chimes and carillon were safely turned off. To this day, friends who sang in the chorus still smile at Woodforde’s dismissal of them as “lacklustre”. We had lessons to learn, certainly, but nor did we expect a “next time”. The audience was cheerful, the ambience was nicely relaxed, and we received warm and favourable comments around the village. One gentleman reckoned it was “the best evening of his life.” The event was even financially successful. Tickets were £10 and there was a modest profit of £832, a great relief to WOAA who had offered to underwrite the event.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

shall take up residence in this picturesque

Soon we were being asked “what are you doing next?” and there was clearly some expectation of continuing. Although Gilly and I still did not anticipate a life sentence, our positive experience in 1993 encouraged us to think further. We realised we would now have to venture out alone as some on the WOAA committee did not relish long-term involvement. Fortunately most helpers stayed with us and Trevor continued as a significant source of help.

What to perform now that Gilly had accomplished her Galatean ambition? We realised that the modest demands of eighteenthcentury music made it more to our taste and budget than larger, later operas. We wanted to ensure that we would attract audiences, and felt that if we offered standard ‘canonic’ repertory like La Traviata or Carmen, which are widely available elsewhere, why would people come to Bampton instead? And so –gradually, although not consistently

– we found ourselves seeking out more obscure repertory, mostly from the period c1740-c1810.

Our next choice was a Mozart comic double-bill and arose from the discovery of an appealing CD of L’oca del Cairo in the Philips Complete Mozart Edition. This virtually unknown work dates from Mozart’s maturity, 1783-4, two years before his great opera buffa, Le nozze di Figaro. L’oca del Cairo (The Cairo Goose) was intended to be a three-act opera, but Mozart despaired of the weak and pretentious libretto and so discarded the project, not even quite completing the first act. What survives however is music of great inventiveness, including a wonderful extended finale scene for seven soloists and chorus which anticipates the amazing achievement of Figaro.

As the work was incomplete and unpublished, we needed to use the orchestration and edition made by

Erik Smith, as recorded on the CD: we tracked down Erik in London, and he became an enthusiastic ally. The one act only lasts about 45 minutes and needed a performance partner: we found an ideal one in Mozart’s short and delightful singspiel (that is, a spoken play with music), Der Schauspieldirektor - The Impresario, a comedy about the trials of an opera manager dealing with the rival charms of a fading soprano Madame Goldentrill and the rising young diva Ms Warblewell.

Many aspects of our enterprise now began to evolve. The most alarming shock came early when we discovered that the Dudleys were selling the Deanery - we anxiously waited to learn if a new owner might be persuaded into hosting our production. In January Mrs Dudley telephoned to say that they had a buyer – a London couple “with a daughter who plays the piano” and an “unusual” name – Ferstendik. That news was remarkable as said daughter, Joanna, was in my A level

“I

village - it’s time to have some fun”

Elvira, in Gazzaniga’s Don Giovanni

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

history of art class at the London school where I was teaching. Her parents, Linda and Peter, discovered they had little chance of escaping becoming an opera venue, even if not quite written into the house purchase covenants. They were still hosting the opera 25 years later.

Another unwelcome discovery was the need for a Public Entertainments Licence from WODC – initiating me into the joys of legalistic form-filling. The PEL process generally involved a cheerful advance visit from the local policeman, the posting of a planning application at the Deanery gate, and a site inspection by the fire officer – who decided that the official escape route from the garden should be via a narrow and obscure opening on the far side of the house between two bushes, which the gardener had to trim to reach the required dimensions. Fortunately the bureaucracy later became much easier.

Many aspects developed, although there was still no staging or canopy. We hired portaloos for the first time - somewhat basic plastic cabins, lined along the entrance pathway; labelling them as for ‘sopranos and altos’ and for ‘tenors and basses’ seemed to cause confusion for some in the audience, and they were unlit once it went dark. We needed a much larger band of 24 players, again ‘fixed’ for us by Felicity: the wind section grew to include flutes, oboes, clarinets, bassoons, horns, trumpets and timpani, that is, a full ‘classical’ orchestra which we grandly called the Westminster Players, as several had links with Westminster School. For the chorus we invited the local Burford Singers, although as rehearsals were of necessity in London this proved a little inconvenient. Soloists included again Gilly and John Virgoe, and we also introduced soprano Amanda Pitt. Amanda (‘Milly’) was to become a regular at Bampton, singing a further 12 roles over many years. The non-singing

Impresario role was performed with characteristic aplomb by Trevor, a stalwart of the Bampton Drama Group. Our first-year conductor and director had moved to Italy, and we now asked Guy Hopkins: he continued conducting for us until 1999. I decided to make my first attempt at directing (my parents had met on the amateur stage and as a child I had regularly helped paint scenery) - I had plenty of ideas, but perhaps not much expertise. I chose a loosely thirties dress style, which would be cheap and easy to manage, and I located the opera ‘at the seaside’: this required a tower in which the lovelorn girls of the plot had been incarcerated by the boorish Don Pippo. Somehow I managed to construct the top part of a lighthouse in our own tiny back garden, but it was a very ramshackle affair. Alan Allinson and David Mills, the fathers of our two 1993 walk-on children, were

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

now persuaded into acting, playing workmen on their tea-break, and we still recall and laugh at how they spectacularly, if unintentionally, became entangled in uncooperative deckchairs. We hired an Oxfordshire Punch and Judy show (and operator) to create a seaside atmosphere, and Gilly’s childhood teddy-bear, June Blenkins, made her operatic debut. In addition to helpers from the first year, we added Peter Williams manning the lights, and the in-house bar was run by Ian Smith, Jacky Allinson and Pauline Smith: Jacky and Pauline (and soon also Gaynor Cooper) became established as amongst our most regular and valuable helpers right up to the present. Pat Smith and Margaret Williams wielded the make-up. Most of our previous supporters kindly maintained their financial interest, and we acquired further modest sponsorship from local and national businesses. The programme also records a fundraising raffle, with themed prizes including a goose, not from Cairo

but from Peach Croft Farm in Radley – the BBC Music Magazine announced “the opera does not go as far as the goose’s entry, but there’s a chance to win a live one in a raffle after the show.” At least the goose (not alive!) no longer had to compete with the Dudley’s peacocks.

Gilly and I took the important decision to translate these Mozart comedies into English, determined that comic operas would be understandable to our audience and raise some laughs. We wrote a new script for the spoken texts of the Impresario as if the sparring singers were auditioning for roles in the Cairo Goose which was performed after the interval, and together we enjoyed the challenge of fitting rhyming couplets to the musical numbers. This far-from-easy task proved to be another starting point for the future.

The Oxford Times sent a new critic, Helen Peacocke, who thought the

event was “quintessentially English” and felt “privileged to have attended this rare performance”. The weather on 16 July was beautifully sunny, the roses bloomed,and we were all congratulated for the “hours of effort that had gone into perfecting the performance”. We were delighted also that the two respected British opera magazines, Opera and Opera Now, both gave the performance advance mention, initiating a vital relationship with these publications which continues today.

A further inauguration in 1994 was a vocal concert of Advent and Christmas music in St Mary’s on 17 December, undertaken in association with the Friends of St Mary’s to raise funds for the restoration of the church spire. We were grateful to the vicar, the Rev’d Andrew Scott, for permission, and the gorgeous acoustic of our magnificent Norman and 14th century church, enhanced the vocal effect.

1995 was the tercentenary of the death of England’s earliest operatic master, Henry Purcell, and we decided to mark this with a performance of his magnificent Dido and Aeneas, an early masterpiece of English opera.

Already aware of our increasing workload, we invited an outside professional group, the Mayfield Chamber Opera Company, directed

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

by the acclaimed lutenist Michael Fields. Some of our previous singers were still involved, but the main roles went to outstanding professionals Evelyn Tubb as Dido, John Hancorn as Aeneas, and Jane Haughton as Belinda. Gilly was ‘second witch’, styled as if suffering a ‘bad-hair day’, and very scary she looked too. Michael, whose own multi-faceted career had begun as a folk and rock musician in California, led a small group of baroque players, himself playing on the impressive archlute and theorbo. A vitally new important figure was Ian Chandler who now took on lighting. Ian had been i/c lighting at the Wyvern Theatre, Swindon, and quickly became adept at the hugely laborious task of trailing cables around the large Deanery garden, working long hours in the blazing sun. Ian is still with us in 2023 and his creativity knows no bounds: he has been an absolute linchpin of nearly all that we’ve done since.

The performance was held later in

the summer, on 19 August. Once again, the sunshine was glorious, but the date coincided with national celebrations to mark the 50th anniversary of VJ Day. There was no concern about the weather but, as Helen Peacocke recounted: “What everyone overlooked was the possibility of passing aircraft disrupting the performance on their return from VJ Day celebrations. At the very moment Nick Fowler drew breath to begin his aria… an entire squadron of aircraft flying in formation passed over the area. Nick struggled gallantly, but the competition from overhead drowned out Purcell’s gentle melodies completely.” In fact the squadron was no less than the spectacular Red Arrows: Peter Ferstendik immediately telephoned Brize Norton airport – a return fly-over was planned an hour later, but Brize Norton cheerfully diverted them. What power we wielded!

Bampton Summer Opera continued with a December event, although

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

our name began to feel somewhat unseasonal. We now selected 21 December as the regular date, the shortest day of the year and the feast-day of Bampton’s own obscure Anglo-Saxon saint, Beornwald, whose probable shrine is in the north transept. In 1995 we chose the delightful and popular Christmas opera Amahl and the Night Visitors, by the then-living composer Gian-Carlo Menotti (1911-2007). We performed it in the composer’s arrangement for two pianos, played by Guy Hopkins and myself, requiring the expensive hire of concert grands and a fair amount of strenuous pew shifting. The opera had been originally written for television in 1951, and in our simple updated production, which involved hanging a lot of purpledyed laundry around the arches of the church, Amahl’s down-atheel mother was watching an old black-and-white television. Amahl, written for a boy soprano, was ably sung by young Nicolas Moodie, son of friends from Northampton.

The Three Kings were played by Leigh Melrose, Richard Ireland and Matthew Sharp, and the Mother by Lindsay Richardson, a very strong cast. We staged Amahl again in 2019, with another fantastic cast.

Gluck’s well-known Orpheus and Euridice was our 1996 summer opera choice, given on an exceptionally hot July day when the heat made the afternoon dress rehearsal severely testing. I began to fall in love with this great composer’s lyrical writing, leading later to several other rarer works by him, and especially his majestic Paris and Helen in 2021. Indeed, from 1997 we resolved to concentrate only on rarities, a policy which has happily led to widespread praise from the press and has continued to intrigue and educate our audiences. A catalyst for this was a recent Royal Festival Hall concert by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment, one of the foremost ‘period’ instrument bands. This intriguing programme, entitled

‘Opera in Mozart’s Vienna’, included music by Storace, Gazzaniga, Paisiello, Salieri and Martin y Soler, and we went on over the coming years to tackle operas by all these neglected composers. That OAE concert included a scene from Giuseppe Gazzaniga’s Don Giovanni, which we realised would ideally suit our forces and budget: we naughtily imagined that some audience might come expecting Mozart and be surprised to discover something new. We performed it in 1997, inviting Standlake resident

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Henry Herford, a baritone of national status, to create the role of the Don’s long-suffering servant Pasquariello. We borrowed unwieldy staging platforms from nearby Cokethorpe School to improve sightlines, and much to the relief of our orchestral players, a sheltering tent was supplied by our lighting technician Ian. Our audiences had been growing, and so we persuaded our Deanery hosts to allow two consecutive evenings, thus giving better value for our performers’ hard work in rehearsing. The pattern of Friday and Saturday performances has continued ever since. Finances were much eased by obtaining a £5000 National Lottery grant – in those days a simple application process, and a development which gave us much more confidence for the future.

It seemed there was no shortage of rare repertory to explore, and future prospects began to excite. In 1998 we ditched the name ‘Summer’ and became ‘Bampton Classical

Opera’, referencing the period of European music in the second half of the 18th century. For a logo we adapted one of the splendid stone Ionic capitals (classical in a different sense of the word) which were ornaments in the Deanery garden.

We commissioned a completion from Oxford musicologist Simon Heighes of Thomas Arne’s supremely inventive but fragmentary 1740 setting of Alfred (the original source of Rule, Britannia!) and my own art-historical interests in the Anglo-Saxon period were exploited in recreations of the monumental Ruthwell Cross and visualisations

of the lovely ‘Alfred Jewel’ from the Ashmolean Museum. Alfred was sung by tenor Michael Powell, living in nearby Crawley, Amanda Pitt played Queen Eltruda, and Michelle Harris the spirited Prince Edward. An appealing cameo scene of historic British kings and queens was cheerfully played by friends from the Drama Group - Pat Smith,

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Kate Elliott (also a delightful dancer in several of our early productions), Alan Allinson and John Smith. By now Pauline Smith, then helped by Pat Smith, was well established dealing with wardrobe – a total of 29 costumes for this production.

The best of these early productions (1999) was the ‘sentimental comedy’ Nina by Giovanni Paisiello (1740-1816), the 73rd opera by this once hugely successful composer. Michelle Harris, a thrilling performer, returned in the title role. I set Nina in a 1930s sanatorium, as the title character is la pazza per amore – the girl driven mad by love. The orchestra involves Italian zampogna – small bagpipes – and finding a player proved a challenge. Eventually we tracked down a French bagpiper, but his bagpipes weren’t quite authentic and were alarmingly loud, and we could only achieve a satisfactory balance by making him perambulate the garden at great distance from the stage. We borrowed a magnificent,

gleaming 1934 green Rolls-Royce which was parked in front of the stage, ‘owned’ by Nina’s uncaring father, the Count, a role suavely taken by Henry Herford. Other singers, already mainstays of our company, were Amanda Pitt and Justin Harmer.

By the time we reached the end of the century, we could enjoy a

warm sense of achievement, even though artistic standards were not always entirely secure. Our constituency MP, Shaun Woodward, hosted a smart fundraising dinner at Sarsden House in 1999, and we began to work harder on cultivation of money and contacts. Most importantly the national press was showing interest. A few days after our Alfred performance, I was

telephoned by the critic Roderick Dunnett, then writing inter alia for the Independent. He was effusive about what we were attempting to achieve, with plenty to praise but also sensible and very helpful criticism. Roddy remains a powerful advocate for our work, revelling in our repertory and our singers. Soon the Daily Telegraph booked a photo-session and Gilly and I had to wield a large scenery flat across the Deanery garden. The subsequent full-page picture article, by the critic Rupert Christiansen, was subtitled ‘the summer festivals that combine meticulous musical standards with truly idyllic surroundings’ and our photograph took precedence over a number of illustrious rivals. That we could feature alongside Garsington, Holland Park, Grange Park and Longborough provided us with heightened confidence, but we also realised that serious press coverage set the bar high for the future and that our standards were now critical.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

The new decade saw energetic experimentation and discovery, with steadily improving standards and expansion to other venues and festivals. Our friend Mary Henderson, who had sung in our Acis and Galatea chorus, was headmistress of Westonbirt School, near Tetbury in Gloucestershire, and

she invited us to perform there in 2000. Westonbirt is a magnificently impressive Victorian mansion of 1864-74, built in a Jacobean style for George Holford, whose vast wealth came from shares in the London water company. Around it stretch 28 acres of terraced and landscaped gardens, whilst outside

its gates is the famous Arboretum which was originally part of the estate. The exterior terrace of the Orangery (the massive room used as school hall and theatre) provided a perfect setting for open-air opera, facing the gardens with the ornate house behind.

“What on earth do they think they are up to? What is happening, why all that noise?”

Ofelia, in Salieri’s Trofonio’s CaveAudience picnicking at Westonbirt School

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

We decided that our millennium opera at Bampton itself would be something special, a setting of The Comedy of Errors, composed in Italian (Gli equivoci) by the AngloItalian composer Stephen Storace (1762-96): this choice later led us to a love affair with Stephen and his famous soprano sister Nancy, who created the role of Susanna in the premiere of Mozart’s Figaro in 1786. The libretto, skilfully adapted into Italian from Shakespeare’s play, was by Mozart’s famous collaborator, Lorenzo da Ponte: we used a singing translation back into English by Arthur Jacobs. Nevertheless we feared that such an esoteric choice might be unwise when trying to establish a new venue in Gloucestershire, and so for Westonbirt we chose Mozart’s Così fan tutte, also written by Da Ponte. Somehow we found ourselves with a Westonbirt date in July just a few days before Storace at Bampton. Both operas were rehearsed simultaneously in London and conductor Simon Over worked

on both. I directed the Storace and one of the Così singers, Robert Batemen, took on the Mozart. The latter was deemed a success, and we added Westonbirt to our regular venues. For several years we perhaps overstretched

ourselves by putting on different operas at Westonbirt and Bampton but at least we spread the dates to opposite ends of the summer. When rehearsing at Westonbirt we billeted the singers in the sixth form centre, with Gilly and our trustee Damian Riddle managing the catering in the domestic science kitchens. We always got plenty of exercise traipsing across the huge estate.

A significant step in 2000 was becoming a limited company and a registered charity “to advance education for the public benefit by the promotion of the arts, in particular but not exclusively the art of opera”. Although this brought with it many time-consuming legal obligations, it meant that we were now ‘properly’ constituted with a Board of Directors and, most beneficially, it enhanced the opportunities for raising grants from charitable trusts and foundations – from then on, every year, I have settled down to long weeks of

writing elaborate grant applications to supplement the vital donations made by our growing number of generous and loyal ‘Friends’. The millennium year also saw an increase in concert activity: we put on a Lent concert in Bampton church, and in the autumn we were invited to give a recital to mark the restoration and re-opening of the peaceful 18th-century Baptist Chapel at Cote, just a couple of miles away and in the care of the Historic Chapels Trust. In December we gave an Advent concert in the famous Norman church at Iffley on the edge of Oxford, and Gilly conducted our second Messiah for St Beornwald’s Day at Bampton. Our schedule was beginning to become busy and to dominate our personal lives, fortunately happily (well, usually).

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

The Comedy of Errors (only the second-ever production in England) had proved a casting nightmare, requiring ‘twin’ baritones and ‘twin’ tenors. The baritones proved fairly easy and we found two excellent ‘twinable’ singer-actors, Mark Saberton and Thomas Guthrie, who continued performing for us for several years. Tenors, a rare species at the best of times, proved trickier: we lost one from our first pairing, and then one from our

second pairing, but eventually our final twins of Benjamin Hulett and David Murphy proved more enduring. In a smaller role was 19 year-old Nicholas Merryweather, who matured into a wonderful and breathtakingly comic singer, performing eleven further roles with us over many years. A nonsinging role went to 8 year-old Rosa French, Gilly’s niece, the first of several appearances for us; Rosa later trained as an actor

and magnificently recited the commentary in our 2021 ‘pandemic’ performances of Gluck’s The Crown (La corona). Comedy was very well received and reviewed in the national papers, especially by Roddy Dunnett (“Bampton’s production put scarcely a foot wrong”) and Robert Thicknesse, and these laudatory reviews led to an invitation to revive it the following

March at the Bath Shakespeare Festival in the magnificent Theatre Royal. Our Bampton scenery was too small for such a large stage, and so we agreed on a semi-staged performance, in modern dress. Dealing with a large professional theatre proved a steep learning curve for us, and it was inevitable that there were problems to iron out. We now had a different

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

conductor, the young Australian Alexander Briger (nephew of Sir Charles Mackerras), and diary clashes necessitated some cast changes from the previous year. Even so, one new tenor failed to learn the music in time: we had to sack him and find a replacement just three days’ before, no easy task for an opera that no-one in the country had sung. The performance was deemed a great success and the Festival director wrote: “thank you all so much – and for being wonderfully calm in the face of adversity!” We were warmly invited to return with another Shakespeare production when we could.

A significant London performance was our next goal. For our 10th season in 2002 we selected the stunning Baroque former church of St John’s Smith Square, a famous high-profile venue. Built in 1710 by the maverick Baroque architect Thomas Archer, it was bombed out in World War II but later restored as a concert hall. Its magnificent

Corinthian columns and splendid chandeliers have framed our London performances ever since. We first appeared there with Mozart: what we titled ‘Waiting for Figaro’ was an enhancement of our 1994 Mozart double bill, now with the addition of a further unfinished opera, Lo sposo deluso. We learned that St John’s has a gloriously warm acoustic but is not always kind to English diction. We placed the orchestra on the stepped platforms of the stage behind the action, an arrangement with which we’ve stayed ever since, despite the problems it causes for singers with restricted visibility of the conductor. Gilly persuaded Edward Gardner, a young up-and-coming conductor, to take on our performances – we little guessed that he would go on to become music director of Glyndebourne Touring Opera, then of English National Opera and now principal conductor of the London Philharmonic Orchestra, as well as significant European posts.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

We returned to the Bath Shakespeare Festival in March 2004 with our Dad’s Armyinspired interpretation of Salieri’s Falstaff, a late and gloriously funny masterpiece by this much maligned composer; we had given the UK première in Bampton the previous summer. We were also invited to the niche English Haydn Festival in Bridgnorth, Shropshire

where we staged our first Haydn opera, L’infedeltà delusa. Haydn’s operas are often passed over, but the music and orchestration are always wonderful and surprising, and L’infedeltà was to reappear in our schedules with several different casts and venues through until 2007. This small-scale opera requires a cast of only five and we hoped would make a conveniently

portable production. The first conductor was Jason Lai (then Assistant Conductor with the BBC Philharmonic); Fiona Hodges, the wife of my school friend Chris Hodges (who was soon to become our Chair) produced a set of beautifully colour-balanced period costumes displaying her skills in historic corsetry. We rehearsed in just a week in London and set off to

Shropshire in a hired van driven by our adorable friend from Radcot, Anne Hichens, who recalls “I got a few double takes when they saw a grey-haired old lady in the getaway van.” Anne, a wonderful source of warm memories about our history and who, with husband Andrew, has sung in many of our choruses, goes on to report:

“We had been warned that the

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

verger of the church at Bridgnorth was a menace. All went well until the interval when the audience were to have dinner in a tent outside. The food had been delayed and we should have started the second part some time ago when Jason, the conductor, said softly to himself, ‘it will affect the production if the delay goes on much longer’. The verger rounded on him and shouted that he was arrogant and pushy…. Jason was appalled and turned to go into the church. I was next to him and thought ‘Oh God, he’s going to cry - if he does there will be no second part of the opera’, so I rushed after him, grabbed his shoulders, swung him round and said hard into his face ‘You know who you are, you know you’re going to be a great conductor and you know that that little man is nothing at all. You wouldn’t give him the thought that you even listened to him, now, would you?’ He took a deep breath and the show went on.”

A more fruitful high-profile festival

emerged when we were invited to the 2005 Buxton Festival, a long-established feature in the UK operatic calendar. Buxton is blessed with a magnificent Edwardian Opera House, a masterpiece by Frank Matcham, one of the greatest theatre designers. Our now established reputation for rare repertory fitted closely with the Festival’s own profile and pursuit of the recherché. The invitation necessitated a major shift in our ambition and working methods. We selected to perform The Barber of Seville – but not (of course!) the famous Rossini version. Ours was Paisiello’s earlier setting from 1782, once triumphantly successful across Europe until Rossini’s setting knocked it off its perch. Our modest locally-produced scenery would hardly be suitable for the large stage, but we were introduced to the wonderful designer Nigel Hook. Nigel’s infectious humour and inventiveness matched the Bampton ethos well and the Barber proved to be one of the funniest

and best performed of all our productions. It was Nigel’s brilliant idea to set it in a 1960s caravan at a grotesque English seaside holiday camp “of timeless ghastliness: (The Times). We engaged a

marvellous and energetic young cast including Rebecca Bottone, Paul Carey Jones, Adrian Dwyer and Nicholas Merryweather, and with two performances at Bampton before swiftly moving to Buxton,

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

we reached an impressive total audience of 2500. Costumes were by Pauline Smith, who happily drew on her own youthful experience as a Redcoat at Butlins Barry Island and Minehead. It was also a pleasure to work at Buxton with the operaloving lighting designer John Bishop.

We went on to give three further operas in later Festivals: Georg Benda’s Romeo and Juliet (UK première) in 2007 and Cimarosa’s The Italian Girl in London in 2011, both benefitting from collaborations with Nigel Hook and John Bishop. Our fourth production there was in 2012 with Marcos Portugal’s The Marriage of Figaro,

but thereafter changes in the Festival management and financial cut-backs curtailed Buxton’s interest in us. Our visits there were always fascinating, especially the slick rigour of the backstage crew, and we always had a good sociable time. I gave pre-performance talks as well as to the Festival Friends, and these were very well supported.

However the trips were always pressurised, especially for Anthony Hall and Mike Wareham driving the van, with all the logistics of props, set and costumes which had to be offloaded from the theatre back into the van overnight. Pauline recalls costume problems for Romeo and Juliet (which opened at Buxton a few days ahead of the Bampton

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

performances): “I took Romeo’s trousers in too much and had to make a new pair in the bedroom of a dreadful hotel where the owner was like Basil Fawlty – I just made them in time for the dress rehearsal although he had to have a pin in them even then!”

Other venues began to supplement

our core from time to time. In 2006 we took Martín y Soler’s La capricciosa corretta (which we naughtily subtitled The Taming of the Shrew, despite its lack of Shakespearian context) to the theatre at Headington School, and the following year (our busiest on record) we revived L’infedeltà delusa for the Wantage Concert

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Club in the Parish Church, and for the Thaxted Festival, Essex. We also took it to the tiny theatre at Buscot House, just the other side of the Thames from Bampton, where we performed it as a surprise at the Diamond Wedding party of our patron Sir Charles and Lady Mackerras – a particularly happy and special occasion.

There was yet another Haydn performance that summer at a venue which soon became a favourite: Wotton House (Wotton Underwood) in Buckinghamshire. This came about through the persistence of Gilly who charmed its owner David Gladstone to add us to his well-established summer recital series. Wotton is a noble Baroque house built 1704-14 by an unknown

architect, with an expansive estate later reshaped with lakes and classical temples by Capability Brown. Like so many country houses of its scale and declining state of preservation, it had once been doomed: it was within a fortnight of demolition when, in 1957, it was rescued at the eleventh hour and bought (for £6000) by one Elaine Brunner, who was only

on a trip past in search of columns to grace a swimming pool. It is a wonderful rescue story – operatic in itself – and well recounted in Ptolemy Dean’s obituary of Mrs Brunner in The Independent, 9 April 1998, available online. Elaine’s daughter April married David Gladstone and the couple inherited the house in 1998, continuing the laborious restoration of house and

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

grounds, and eventually revealing the amazing ‘tribuna’ (entrance hall) by the maverick architect Sir John Soane (1753 - 1837), which had been obscured in an interim restoration.

David is a retired diplomat, formerly High Commissioner to Sri Lanka and later responsible for establishing the first British Embassy in Ukraine. Erudite and civilised, he and April fostered their delightful concert series over many years in the grand salon at Wotton, selecting artists of calibre as well as nurturing emerging musicians: it was the Wigmore Hall of Buckinghamshire. Black tie evenings opened with welcome drinks before the concert, and a handsome dinner afterwards.

Presenting opera at Wotton was no easy task as the elegant space was severely restricted, especially as audiences for our operas tended to be at the maximum. Although L’infedeltà delusa was first presented there with only

piano accompaniment, our later productions were with small instrumental ensembles, usually of

and they were always well received. The post-performance dinners were an opportunity to network, and

extraordinary and beautiful Arts and Craft house by Edwin Lutyens near Stockbridge in Hampshire. Here the owners, John and Camilla Hunt, asked us to give a similar small opera performance in their handsome panelled ball-room at an annual summer house-party: Arne’s Judgment of Paris in 2010 was followed by other one-act works in our repertoire by Handel, Philidor and Gluck.

period instruments, who had to be arranged around the margins of the tiny stage. We went on to give six further operas, all rarities by Handel, Arne, Haydn and Mozart,

we made some valuable contacts amongst the discerning audiences. One of these was to lead to a further sequence of country-house performances at Marsh Court, an

A rather different enterprise developed with education performances at Queen’s College, the girls’ independent school in London’s Harley Street where I taught history of art. Gilly was adamant that she did not want a project which was condescending to young singers, but rather a substantial effort which would enable the teenagers to develop their voices and confidence. We began in spring 2002 with a selection of scenes from The Marriage of Figaro, and later that year some of the girls augmented

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

the chorus in Mozart’s ‘Waiting for Figaro’ at Westonbirt and St John’s Smith Square, enabling them to work with and learn from some outstanding experienced musicians. One teenage soprano from that time, Caroline Kennedy, went on to train as a singer and later took roles in several Bampton productions, most recently in 2019 as the maid Bettina in Storace’s Bride & Gloom, a role which well suited her quirky and vivacious comedic skills.

Subsequent productions at Queen’s enabled talented teenagers singing the major female roles to work as equals alongside male professionals, unfailingly raising the girls’ standards. Best were Mozart’s charming juvenile opera Apollo and Hyacinth in 2007 and especially Schubert’s rarity The Conspirators (Die Verschworenen) which we staged in the school hall in March 2009. Gilly conducted both these operas and the visiting professionals were Edmund Connolly and Tom Raskin, who were so kind and supportive in their mentoring of the

youngsters. Men teachers enthusiastically added the lower voices to the otherwise teenage chorus.

Schubert’s score is a complete joy and was to impress and influence Arthur Sullivan. We were delighted that Opera magazine sent a leading reviewer (Igor Toronyi-Lalic) and his thoughtful comments remain as one of Bampton’s loveliest reviews:

“The result was intermittently scrappy and confused, yet still also a joy. Few of the period opera companies, who spend so much time and effort trying to recover the original feel of a work through elaborate academic digging, come close to conjuring up the atmosphere of authenticity of these performances. Schubert and his friends would surely have felt at home with Bampton’s small production … so full of warmth, personality and camaraderie, all charmingly fraying at the edges. The young, raw voices were the highlight.”

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Staging opera in the Bath or Buxton theatres has advantages of comfort - no chill breeze to unsettle the audience, no unexpected gusts of wind to topple the precarious scenery (or worse, a mirror, as happened at Bampton in 2002), no suspicious raindrops to panic the violins and cellos, no thunder-claps when there is no percussion marked in the score. As Richard Bratby cheerfully explained when reviewing us in The Spectator in July 2022:

“Audiences bring their own picnics and chairs and sit there in GoreTex and pac-a-macs, munching away throughout. We were advised that the opera would move to the church if it rained, though I suspect it would have taken a Thames valley tsunami to shift this crowd.”

With our garden performances, the weather has certainly sometimes taken its toll, but it’s miraculous how rarely we have had to shift into our indoors alternative. In the 1990s the problem was more

likely to be extreme heat and sun –indeed Bampton audiences used to threaten to plan family weddings on our opera weekends because we were so blessed by fantastic sunshine. This may have been an arrangement with the Almighty brokered by one of our original Board members, the Rev’d Martin Seeley (now a Bishop, but sadly no longer on our Board). However I remember feeling increasingly tense at Westonbirt in 2002: as we reached the driving energetic finale of Mozart’s Cairo Goose I became uneasily aware of darkening skies and distant rumbling thunder. Was our conductor, Edward Gardner, also aware of this as there appeared to be a definite hastening of pace in the final pages? It was just as well – about 30 seconds after the last chord, the deluge hit like the crash of a massive cymbal, and everyone dived for cover. Ed later protested he was quite unaware of the threat, and that his accelerando was purely musical.

At Bampton itself we managed a whole decade without serious weather problems. If the evenings were chilly, they could be alleviated by a supply of local council emergency blankets of which we were the temporary guardians. The first weather casualty only came in 2003, with the second evening of Falstaff, but the audience seemed happy enough to be crammed into St Mary’s church, dry and with excellent acoustics. We had such a full house that some were seated in the choir stalls behind the action, and we instructed the cast (who had had no rehearsal in the church) to be flexible and to turn to face them from time to time, and everyone seemed very happy. Anne Hichens relates a story about tenor (and master comedian) Mark Wilde:

“he was dressed as an American airman, singing ‘She revels in my pain…’ just as Elvis Presley would have…. But later making a fast exit round the pillar, slipped on the flags and fell straight at me, sitting

“Unseen, invisible, spirits ineffable, you cause the thunder crash, you cause the lightning flash!”

Trofonio, in Salieri’s Trofonio’s Cave

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

on the feet of the medieval crusader lying there - as he approached along the floor I grabbed the mirror to prevent a further accident, and he and I ended up five inches from the floor staring into each others’ eyes.”

Our next indoors performance was not until July 2007, when we performed Georg Benda’s lyrical but curious setting of Romeo and Juliet, another UK première. As mentioned above, we had preceded the Bampton performances with two at the Buxton Festival, and we had glorious Pre-Raphaelite sets by Nigel Hook and elaborate Victorian costumes by Pauline Smith (helped by Jean Gray and Fiona Hodges). All should have been well: by the time we reached Bampton a few days later, the production was well sung in, and our Thursday evening dress rehearsal in the garden was accompanied by serene warmth and calm skies. As Juliet sings at the opening: “She too is silent, the singer of the night, a peaceful silence has descended on all creation.”

The ‘make-do-and-mend’ nature of the church performances worked well, and the wartime costumes hired and made by Rose Martinez were a treat.

However by the next morning, the performance day, that peaceful silence was shattered: the sky was barely visible, and we were all sharing with Juliet “the fear

which creeps upon me in the darkness.” The rains began, and quickly developed into a monsoon of unforgettable dimensions. Within hours Bampton was marooned as an island with the roads in and out virtually impassable – indeed many residents were flooded out of their homes that day. But The Show Must Go On, of course, even if in the church and without the scenery which was too hefty and soaked to move. All the cast were staying in the village, but by midafternoon we realised that only a random handful of our orchestral players could reach us from outside. With no viable orchestra the only solution was for conductor Matthew Halls to play on the church piano, a far from perfect instrument and of course untuned. To make matters worse there was soon a total power cut. Fortunately candles were appropriate to our Victorian concept, and we gathered as many as we could and placed them around the church. Playing the piano without adequate

illumination would have been challenging, but a resourceful member of the audience drove his car down the churchyard footpath to the porch and rigged up the piano with a light powered from his car battery.

It became a spellbinding performance, especially the extraordinary funeral music which dominates the third act – “These candles were divinely meant to lead her to the altar.” The ‘dead’ Juliet (soprano Joana Seara), in a cascading Victorian wedding dress, was carried solemnly on a bier by four black cowled monks around the church - an intense and moving experience, still often mentioned by the few who were lucky enough to see it (only about 30 people could make it to the performance). This being an eighteenth-century setting of Shakespeare it resolves unexpectedly with a happy ending: as Romeo (sung by tenor Mark Chaundy) is about to swallow the poison, Juliet’s sleeping draught

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

wears off and she murmurs his name. Romeo exclaims ‘Oh God!’ (it must be admitted, that’s not a great line) - and at that very second the Almighty did indeed intervene and electric light was restored to the church. As Romeo goes on to say: “Is this a miracle? Or only a dream?” The second evening,

when the flood waters were even higher, we kept to the atmospheric candlelight, even though by then electricity was restored.

Another memorable church performance was Salieri’s The School of Jealousy in 2017: again, perfect weather for the Thursday

dress rehearsal, but torrential rain on performance days. Despite the rain many in our hardy audience made use of the available tents in the garden, determined that their picnics should not be spoilt. Jacky Allinson and friends moved the all-important bar indoors, and St Mary’s became the only church in

Christendom with a licensed bar in the Children’s Corner. But we even needed a marquee indoors as thieves had recently stripped the lead from the aisle roof, and we didn’t want the drinks to get watered down!

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Many 18th century operas incorporate an on-stage storm which has always felt like tempting fate. We conjured up a magnificent storm, whipped up by the god Apollo, no less, in Gluck’s Philemon and Baucis in 2016, which we set in a spartan low-cost airport, but the funniest was probably that in Paisiello’s Barber of Seville. At Bampton the enclosing Deanery hedge was studded with a multitude of plastic ‘Seville’ oranges, and as Paisiello’s stirring storm music gradually grew in intensity, the backstage crew started throwing oranges from behind the hedge onto the stage.

Dr Bartolo’s two redcoat servants, Mr Sprightly and Mr Lively (played with terrific panache by David Murphy and Jonathan Sells, and who earlier had sung an outrageous snoring and sneezing duet), now wrapped up against the ‘weather’ in sou’westers and pac-a-macs rushed on to catch the cascading oranges in fire-buckets – the inspiration was the 1960s TV contest It’s a

Knockout. Nigel Hook’s gloriously crazy holiday-camp caravan was built with a number of boobytrapped features and so began cheerfully ‘misbehaving’ – washing line billowing, window curtains twitching, lights fizzing, flower box collapsing, TV aerial rocking – it may all sound innocuous but was hilarious. The scene caused unexpected problems at the Buxton Festival, however, where we found that the oranges gently rolled down the raked stage and into the unsuspecting orchestra pit. Fortunately the discovery was made before any orchestral players suffered headaches, and we replaced the oranges with a collection of hastily-purchased softer and less mobile teddy-bearsperhaps not as apt or as funny, but a typically surreal Bampton touch.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

“Prima la musica e poi le parole”

First the music and then the words –title of an opera by Salieri

I’m frequently asked: how do we find our rarities? In 2018 I tried to answer this for an article published in Classical Music magazine entitled ‘Lost and Found’: as the sub-title explained, Bampton ‘has dedicated itself to dusting down forgotten

works and presenting them in fresh new colours before today’s intrepid audiences.’ I’ve mentioned above our unfamiliar versions of Barber of Seville, Don Giovanni, Marriage of Figaro, Falstaff and Romeo and Juliet, and to these we might

add Bertoni’s Orfeo and Isouard’s Cinderella (both UK premières). Bampton has long been committed to undermining the glib adage that “operas are forgotten for good reason.” The risk-adverse programming strategies of most

Sisters’ Jenny Stafford and Aoife O’Sullivan fight it out in Cinderella, 2018 (photo AH)

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

companies seem to pander to cautious audiences, reluctant to venture beyond the tried and tested. How limiting that seems –and we are thrilled when, as often happens, our public report that “it is such a wonderful opportunity to hear and learn about unknown operas: Bampton Opera gives us this – no-one else does – thank you!”

How do we set about “refreshing the parts that other companies cannot reach”? Usually we reach first from our bookshelves for our well-thumbed copies of Amanda Holden’s Viking Opera Guide and The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. From those, often in tiny print or in footnotes, we might learn of obscurities which intrigue

us. La pazza giornata, ovvero Il matrimonio di Figaro’, the 1799 setting of the Marriage of Figaro story by the Portuguese composer Marcos Portugal (1762-1830) was one such exciting discovery in the smallest print in Groves. CDs can also often be a starting point: the Italian record label Bongiovanni has offered many fascinating rarities,

and the recent recordings by the German orchestra L’arte del Mondo have led us to Salieri especially, including our 2023 choice, La Fiera di Venezia.

Selecting a rarity is one thing, but obtaining music for it, if unpublished, is challenging. The internet often produces wonders,

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

since original manuscripts from, for example, the extensive collections of the Austrian National Library or the Saxon State and University Library in Dresden can be accessed so easily from our computer screen. For Portugal’s Figaro (performed at our home venues 2010 and revived at Buxton), we easily located Dr David Cranmer, an English musicologist at the Universidade Nova in Lisbon and

the acknowledged expert on this obscure composer. David was already engaged, along with his students, on a major project to edit manuscripts by Portugal, and happily had funding to do so. After a couple of years collating the different manuscript sources, we eventually received the neatlyedited score and were able to prepare the first performances anywhere since its Venice première

in 1799-1800. Whilst it was rather like looking at Mozart through the wrong end of a telescope (although probably Portugal did not know the famous original version), it again proved fascinating to encounter a familiar operatic plot transformed through different music. It’s gratifying that other productions elsewhere have followed, including one in New York by On Site Opera in Bampton’s English translation.

We often commission our own music edition; editors Brian Clark and Peter Jones have (separately) produced several works for us, including Gluck’s Philemon and Baucis which used a manuscript in the Royal College of Music. For The Philosopher’s Stone, which was jointly composed by a team of musicians in Mozart’s circle who a year later helped create The Magic Flute, we were supplied with scores

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

by Prof. David J. Buch (University of NorthernIowa), who had recently created a performing edition. The Hampstead Festival got to it just ahead of us in 2001 with a concert performance but we gave the UK staged première.

Sometimes our audiences are caught unawares. After a performance of Gazzaniga’s Don Giovanni at Westonbirt, a perplexed man protested that he had recordings at home and “I haven’t recognised a single note all evening”, clearly not realising that we were not performing Mozart. Usually however our audience is well prepared: a precious personal memory is sitting at the Deanery in 2008 with our then patron, Sir Charles Mackerras. It was our UK première of Ferdinando Paer’s 1805 opera Leonora, a powerful anticipation of Beethoven’s version composed a few months later (and which eventually mutated into the famous Fidelio). Mackerras had conducted the Beethoven frequently

and could barely contain his excitement as he spotted various motifs which Beethoven had ‘borrowed’ from Paer.

We’re always delighted when critics acknowledge the enterprise of our repertory, such as Alexandra Coughlin, writing in The Spectator in July 2015 about Salieri’s Trofonio’s Cave. “Oxfordshire’s Bampton Opera is pretty much guaranteed to produce a show you won’t have seen before.” Most gratifying was how our reputation led our 2019 production of Stephen Storace’s Gli sposi malcontenti (performed under the title Bride & Gloom) to be selected as a Finalist in the Rediscovered Works category of the 2020 International Opera Awards. We were the only UK company in our category and up against major foreign contenders – although we didn’t win, it was a proud honour (and, besides, the pandemic meant that the glitzy awards ceremony was relegated to being a rather dull online evening).

E poi le parole - throughout we’ve been determined to perform in English, so that our audiences can be engaged fully in what they see and hear. There are of course powerful arguments for original language opera – although the whole thorny issue of language has been modified in recent decades by translated surtitles in theatres, fine when they work, irritating when they’re ‘out of sync’ or incorrect. But, especially in comedy, reading a surtitle can awkwardly anticipate a visual gag on stage, thus ruining the impact of musical synchronisation. Bampton translations aim to project an appeal which might win over even determined lovers of original language opera. Whilst some singers regret the loss of the ease of Italian text, it is generally much quicker to memorise and rehearse in English.

Occasionally our operas have used existing English translations, but usually our rarities need to be translated from Italian, German

or French. With The Cairo Goose in 1994, Gilly and I discovered that the challenge of translating an opera was intellectually enjoyable, although stressful and timeconsuming. Neither of us can claim to be polyglots, but musical translation is like a crossword puzzle, fitting words into awkward spaces dictated by pitches and beats. Whilst sincerity and truth of meaning are crucial, most important are placing stresses in the right places and using vowels which suit the flow of music and the voice. Especially in comedies, rhymes reinforce humour, as any G&S fan would agree. Sometimes, we must admit, what we produce is more a ‘version’ than a ‘translation’ but this enables entertaining production-specific flavour.

Figaro’s ‘catalogue’ aria in The Barber of Seville lists his Spanish travels in Castliglia, la Mancia and Andalusia – but in our holiday-camp version:

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

“First of all I tried out singing, but the press reviews were stinging, so I packed my bags and chattels, ran away to fight new battles.

I began at Barry Island, Bognor Regis was the second. Next I went to work at Minehead, but they found me too refin-ed, so I got a job at Filey, didn’t work so tried Pwhelli.

Some were lovely, quite delightful, but the others were really frightful.”

In recent years, Gilly has mostly taken over the translation task entirely, and her witticisms and rhymes are clearly hugely endearing – like our venues, the libretto is often one of the main draws for regular audiences. Recently she excelled with Haydn’s Il mondo della luna (‘Fool Moon’), which she peppered with at least 14 rhymes for ‘moon’, from ‘baboon’ to ‘spoon’, and contrived to introduce mentions of Apollo Eleven and the Sea of Tranquility. Perhaps it was not a translation for the purist, but it was wonderful fun to sing and clearly delighted our audiences.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

since a gay Robe an ill Shape may disguise,

Paris, in Arne’s Judgment of Paristext by Congreve

Staged opera needs to bring music and language into a communicative relationship with setting, costumes and acting. Whilst the earliest Bampton operas barely used scenery and the garden setting of the Deanery sufficed, as we upped our game, we had to be more ambitious, although this has a massive impact on constrained budgets. With open-air opera there are no helpful theatre wings in which to conceal furniture and actors, and scene changes are challenging to effect. From 2000, with additional venues, the issue of design became more complex: the Deanery, Westonbirt and St John’s are widely diverse. In a traditional opera theatre, conductor and orchestra are in a ‘pit’ in front of the stage, but we’ve never dared introduce bulldozers into the Deanery garden! Here we place the orchestra in a tent ‘stage left’ (that’s to the right as audience see it). At our other regular venues we now place the players behind the stage, but that creates challenging

scenic issues. At the Deanery there’s also the problem of masking the central gap in the hedge – vital for entries and exits, but an irritation when the audience can see right through to the backstage area behind.

Our first set of any complexity was for Comedy of Errors. Mindful of the location of the Shakespearian story in Ephesus, I wanted a loosely Arabic look, and was thrilled when the Laura Ashley shop in Regent Street, London, donated their discarded window settings of elegant pierced Moorish-style arches, made from MDF, painted a glittery deep red and with inset panels of coloured Perspex. Adding some matching red striped curtains in the arches from Pauline Smith’s extensive fabric collection, mounting the arches around some platforms, all set on a stage painted like a chess board, created a charming all-purpose environment which worked well despite the different scenes required in the plot.

The necessity of a much larger set at Buxton has been mentioned above. Nigel’s Barber caravan was built for us by Rose Bruford College (a theatrical college) in Sidcup, and I remember the excitement of it being unloaded at Bampton from the delivery lorry. At this time we began to benefit from the arrival in the village of Mike Wareham and his willing involvement -

“And

When each is undressed, I’ll judge of the best, For ‘tis not a Face that must carry the Prize.Mike Wareham (2009)

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Mike is a man of hugely diverse talents who had already built up considerable experience in operatic stage management and prop construction for another small company. He became site manager, organising everything from marquees and signs to portaloos, but he was also busy creating props and scenic additions, especially Figaro’s lawnmower, complete with a rotating red-andwhite spiral ‘barbershop’s pole’. Mike’s handiwork was brilliantly in evidence the following year, in La capricciosa corretta. I set the production in Naples in classical Roman times, which opened up many comic possibilities. Mike triumphed with a ‘mosaic’ panel (based on the famous original ‘Cave canem’ from Pompeii) in which the eyes of the depicted guard-dog flashed red and his jaws emitted smoke. This being yet another opera with a storm scene (the main character declares “I’ve a horrifying notion something bad’s about to start!”), Mike contrived a

huge revolving panel which revealed Mount Vesuvius, no less, and which Ian’s lights made spectacularly erupt.

By 2007 Mike was joined by another skilful village resident, Anthony Hall. Together they billed themselves as ‘Bampton Scenic Workshops’ and, although they didn’t always agree on the best way to load the back of van, the collaboration was fruitful and multifarious. They were even persuaded (perhaps with some reluctance) into costume, as monks carrying Juliet’s bier in Romeo and Juliet, and as French revolutionary soldiers in Leonora in 2008. The set for Leonora was one of our best home-builds, constructed around massive tower-like blocks donated by English Touring Opera – we took a van down to the Peacock Theatre in London to load them up late at night after the end of their Magic Flute. In their recycled Bampton guise they were doublefaced, and we revolved them in the interval, with attractively

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

distressed brickwork in the first act, damp prison stone in the second. Act 2 also incorporated a working ‘guillotine’ which Mike built in his garden, alarmingly visible over the wall to passers-by on Bampton’s Bridge Street. Mike loved the challenge of making something work: his contribution of a framed sailing ship painting as the centrepiece in Nigel’s wonderful (and ghastly) Trafalgar Square hotel for Cimarosa’s The Italian Girl in London was a classic. In yet another operatic storm scene, the ship on this innocuous-looking picture began to rock and crash amongst its painted waves with delightful comic Captain Pugwash-like effect.

Bampton Scenic Workshops

flourished with charming sets for Haydn’s Le pescatrici in 2009, with colourful Italian water-front fishstalls and a full-sized boat that glided across backstage, and for The Marriage of Figaro in 2010. By now construction was taking place in a massive barn lent by Andrew

Hichens at his farm in nearby Radcot. The Figaro set was very beautiful, especially in the garden by moonlight, and was constructed around a series of large pierced Islamic panels, donated to us by the Tate Gallery.

Mike stepped down from active strenuous scenic service in 2012, but fortunately Anthony was poised to take over and, with the able help of Trevor Darke, produced robust and immaculately measured sets from 2013 to 2018. For the surrealist Magritte setting for Mozart’s convoluted La finta semplice in 2013 Anthony also became a master of helium-inflated balloons, so that we could ‘fly’ Magrittean bowler hats above the set. Anthony’s scenic triumph came with Salieri’s Trofonio’s Cave in 2015 when the audience greeted the scenery ‘reveal’ at the transition between the acts with enthusiastic applause, as a handsome Edwardian bookcase smoothly rotated to reveal a perfect copy of Dr Who’s Tardis.

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

The 2016 ‘Arne-Air’ low-cost airport, and especially its post-interval transformation into the interior of a plane, complete with hostess trolley and a bifold-doored aircraft loo, was another Hall/Darke triumph.

Closely involved with sets are furniture and props, mostly stored in a rented container and garage in Bampton: strange and evocative collections of oddities. Pauline has scoured Bampton garages for strange things like chains, baskets, huge needles, tankards and “goodness knows what else”. Sourcing props is usually great fun! Haynes of Challow is often worth a visit – the origin of the antique wheelchair which we used in L’infedeltà delusa and recycled in 2022 in Fool Moon. Ebay is wonderful, producing anything from plastic fish to bouncing cupcakes. The loft of our garage at home is crammed with crates containing bouquets of artificial flowers, vintage telephones, crockery, baskets, weapons, umbrellas,

oranges and snowballs. We have a set of air-hostess life-jackets, given us by Monarch Airlines, and used to devastating comic effect in a complete ‘safety routine’ by the rival goddesses Venus, Juno and Pallas in Arne’s glorious trio, “Turn to me, for I am she!” (The Judgment of Paris). Our newest Master of Properties is Andrew Collier, husband of our Vicar, Janice (who continues a warm welcome to us for our use of the church) – Andrew’s enthusiasm for handicraft is infectious. For Fool Moon he constructed a magnificent giant magnet and a signpost on the ‘moon’. Some props need to be borrowed such as a 12 footlong alphorn for Gluck’s Il parnaso confuso or, most memorably, a full-size and frighteningly authentic Dalek for The Philosopher’s Stone. The latter was built by an Oxfordshire undertaker, Chris Potter, who also operated it – in the dress rehearsal we discovered that he couldn’t see under stage lighting, and we had to choreograph a dancer to be always in front of him,

and to add a projecting safety lip around the margins of the stage to avoid accident.

The labour of sourcing and creating costumes is immense. In the past Pauline Smith and Fiona Hodges (as

volunteers) have borne the brunt of this, and we’re delighted that, after a few years using external costume professionals, Pauline returned to us last year with Fool Moon, ably assisted by Anne Baldwin. Pauline has a brilliant sense for

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

colour, and how to lift costumes with accessories. Not surprisingly her chief vexation is when singers’ measurements prove incorrect: last year a carefully manufactured coat was completely wasted when it transpired that the singer

was several sizes smaller, whilst meanwhile she was also having to cope with the growing ‘baby-bump’ of a soprano across the two months of our performances. We store several hundred costumes upstairs in the Village Hall, and from time

to time, we have a necessary cull to make room for new ones. Pauline is always on the lookout for useful additions to the collection, some of which she acquires through her volunteer work at the Bampton Community Shop. Pauline and

Anne are currently engaged in cataloguing our collection, whilst keeping an eye on the perennial problem of rapacious moths –perhaps we should install that Dalek to exterminate them. Except Daleks don’t climb stairs!

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

SpectatorI have reached my last page, and yet barely mentioned the past decade which has seen many of our strongest productions and finest casts. Bampton’s unique exploration of superb rarities by Gluck, Haydn and Salieri deserves greater emphasis, along with our appearances at London’s Wigmore Hall and Oxford’s historic Holywell Music Room. Also important is our Young Singers’ Competition which, biennially since 2013, has encouraged and supported singers aged 21-32 and their pianists. And there are so many incredible musicians who deserve much more than a passing mention throughout this account!

Clearly a longer history needs to be written, in which to acknowledge our long-standing Board of Trustees, our honorary Patrons, and our wonderful friends in Bampton and Westonbirt who help with frontof-house, accommodation for musicians, back-stage and a myriad of other essential tasks. Vital to our existence are those who

financially support us with such generosity and loyalty, even from as far away as Australia and the USA. Writing this account has reminded us of how those joining the Bampton community have happily inherited involvements associated with their house - the Ferstendiks at the Deanery were a good example of this and, when they eventually sold the house in 2020, Nicki and Eric Armitage warmly took on the opera. Opposite their gates is Cobb House, where Louise and Viv Robinson generously hosted many Friends events and post-performance parties; when they moved on, Pippa Harris and Richard McBrien enthusiastically continued the hospitality. On the other side of the village, Marina and Chris von Christierson are long-term supporters and hosted a memorable fundraising event with an appearance from our Patron, Dame Felicity Lott. Rosemary and Mike Pelham at Weald Manor have let us rehearse there frequently, and it was a joy to stage Handel’s

Clori, Tirsi e Fileno in their beautiful gardens last September. Marie and Rupert Dent, and Sarah and Nigel Wearne have warmly hosted postperformance parties, and recently we’ve held lovely garden parties for our volunteers at the Vicarage.

There’s a famous humour book by Hugh Vickers entitled Great Operatic Disasters and I cannot resist concluding with mention of a couple of ours. In 2015 Ukrainian mezzo-soprano Anna Starushkevych, first prizewinner of our inaugural Young Singers’ Competition, gave a superbly engaging performance as Ofelia in Trofonio’s Cave at the Deanery in July. She then returned to her homeland to see her family, but found herself stuck in Kyiv with visa problems, unable to return to the UK for the Westonbirt and London performances. We requested the intervention of our local MP (who just happened to be the then Prime Minister!), but even so the Foreign Office still failed to process the

“giddily exciting, propelled by wit, charm and bags of joy”

The

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

visa in time and we had to resort to some rather complex (albeit successful) cast substitutions for the later performances. Another no-show was at our St John’s Smith Square performance of Romeo and Juliet in 2007: on the day our ‘Friar Lorenzo’ found himself grounded in Amsterdam with cancelled flights. We were hopeful he would just make it back in time for the performance, but at 7.20 pm there was still no sign – I was hastily costumed and went on stage for Act 1 (when fortunately it was a speaking role only) with a crib text conveniently secreted in Lorenzo’s prayer-book. Our singer just made it back to London at the very end of the interval: I gratefully handed over the costume and the audience was spared my inadequate singing in Act 2.

The Times once called us “the epitome of music in a garden, and exceptional value for money.” We have maintained a remarkable reputation for the quality of our work and the pleasure we provide

audiences. This booklet and the exhibition will be all worthwhile if you feel encouraged to come along to a performance and discover why The Spectator described us as “giddily exciting, propelled by wit, charm and bags of joy.”

THIRTY YEARS OF BAMPTON CLASSICAL OPERA

Operas performed at Bampton

‘W’ indicates also at Westonbirt

‘SJSS’ also at St John’s Smith Square London; * indicates UK première or staged première

1993 Handel, Acis and Galatea

1994 Mozart, The Impresario and The Cairo Goose

1995 Purcell, Dido and Aeneas

1995 Menotti, Amahl and the Night Visitors

1996 Gluck, Orpheus and Euridice

1997 Gazzaniga, Don Giovanni (also at W, SJSS, 2004)

1998 Arne, Alfred

1999 Paisiello, Nina

2000 Storace, The Comedy of Errors (also at Bath and W, 2001)

2001 Mozart, Henneberg, Schack, Gerl and Schikaneder, The Philosophers‘ Stone*

2002 Cimarosa, The Two Barons of Rocca Azzurra (also at W, SJSS, 2003)

2003 Salieri, Falstaff* (also at Bath, 2004)

2004 Haydn, La vera Costanza

2005 Paisiello, The Barber of Seville (also at Buxton)

2006 Martìn y Soler, La capricciosa corretta (also at Headington)

2007 Benda, Romeo and Juliet* (also at Buxton, W, SJSS)

2008 Paer, Leonora* (also at SJSS)

2009 Haydn, Le pescatrici (also at W, SJSS)

2010 Portugal, The Marriage of Figaro* (also at W, SJSS, and at Buxton 2012)