Water, Wells and Waste

in Bampton and Weald

by Alistair Wray and Paul Ader

September 2024

SUMMARY

This publication looks at how water has shaped the development of Bampton and Weald, bringing opportunities and challenges.

It looks in detail at how local families have accessed water and disposed of wastewater and human waste, and the evidence supporting this and finally how communities banded together to obtain improved water supplies, address growing pollution challenges and secure wastewater treatment facilities and how our water and the services it provides must be safeguarded.

We hope that you enjoy this publication and the insights it brings. It links to other Bampton Community Archive publications which are referenced.

We were going to include a section on flooding challenges but given the amount of material we have obtained, that is for another time.

Thank you to all who have provided information and agreed to be interviewed for this exhibition and the related publication, in particular to Jo Lewington and Janet Rouse for their long memories and overall guidance.

CONTENTS

Chapter 1

WATER: A BLESSING OR CURSE

Chapter 2

WELLS AND PRIVIES - HOUSEHOLD PROVISION

Chapter 3

MUNICIPAL WATER AND SEWAGE: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

Alistair Wray

Retired Fellow of the Institution of Civil Engineers and a Member of the Chartered Institution of Water and Environmental Management, with a background of more than 45 years in international development and infrastructure service provision, including water supply and wastewater, in the UK, the EU and over 30 countries worldwide. Alistair has enjoyed collating information for this exhibition and publication on water shaping our local environment and the roll played by wells and privies.

Paul Ader

Paul has over 40 years of experience in accountancy, business analysis, training, change management, and sense-making. From 2007 to 2012, he played a key role in national reforms to the process of certifying the cause of death. Lessons from these reforms led him to adopt a complexity-informed approach to change that starts with the way people make sense of their lived experience. Between 2013 and 2021 he led and mentored use of this approach in 9 countries, including Lebanon, Pakistan, Afghanistan, South Sudan, the UK, and the USA.

At the start of the Covid pandemic, Paul decided to work closer to home. Since then he has had part-time roles with the Community & Wellbeing Team at West Oxfordshire District Council, Active Oxfordshire, and Citizens Advice West Oxfordshire.

Paul has an active and growing interest in local history. He also helped start the Shill Brook Catchment Partnership to inform and activate community engagement on sewage pollution, flooding, and river environment.

Water Shaping the Local Environment:

The development of Bampton and Weald, with its proximity to the Thames flood meadows, was strongly influenced by water and watercourses and the opportunities and risks they bring. Giles, in The History of the Parish and Town of Bampton, 1848, describes all this enthusiastically.

“The climate of Bampton is considered to be remarkably salubrious, owing in great measure, to the gravelly nature of the soil. The water is also excellent, except in situations where it is exposed to contamination from decayed vegetable-matter. Fish abounds, not only in the river, but also in all the brooks; and the fine flavour which they possess, is thought to be a strong proof of the healthiness of the air. The soil of the northern part of Bampton (..) abounds in clay, which renders the cultivation of the land more difficult and its profits less ample, but the soil of that portion of the district which lies in the plain, is a continued stratum of gravel covered by a thin surface of vegetable mould. It is tolerably fertile and susceptible of a high degree of cultivation, except where it is exposed to the annual inundation from the river.”

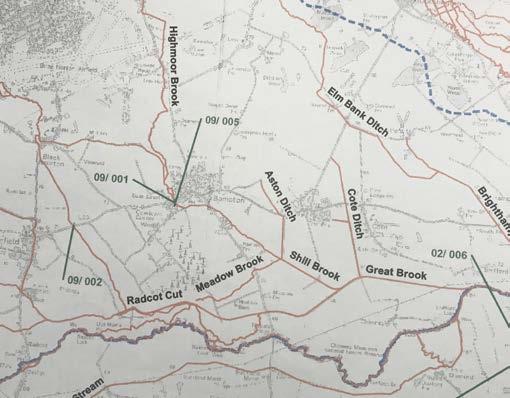

Bampton and its watercourses

Bampton

Bampton and other nearby villages were in fact built on slightly raised areas of ground to benefit from the surrounding fertile soils but reduce flood risks. The History of the County of Oxford: Volume 13, Bampton Hundred, 1996 provides useful references on how the townships of Bampton and Weald developed and were defined in part by Shill Brook and Highmoor Brook and also by roads south to crossing points over the Thames (pages 8-10.) It also mentions the importance of river transport from the early Middle Ages and the possible existence of an artificial watercourse west at the Deanery down to the Great Brook and on to the Thames at Shifford although this had been backfilled by the end of the Middle Ages. Another influence on the development of the town may have been the alignment and importance of holy pilgrimage sites including the Lady Well, the Deanery Chapel (a two story chapel within the present Deanery, St Mary The Virgin Church, which has variously been dedicated to St. Beornwald, St John with St Mary and then St Mary, and finally to

St Andrews Chapel next to the Beam and others (page 12.) The Lady Well at Ham Court was known for its supposed healing properties in the late 18th century and its probable importance as a religious site much earlier and its association with eye ailments suggests connections with the cult of St. Frideswide.

However, despite some prosperous farms and various religious buildings, the town remained small (a 17th century population of around 500 with 100 houses, growing in fits and starts to about 1,700 and 390 houses by the mid-19th century which, although this dropped to 1,104 in 1921, has been increasing steadily since - population 2,564 in the 2011 census). This and more recent housing developments place growing demands on water and watercourses.

While the soils, water and topography created productive areas for farming, drainage has always presented difficulties on the heavy clay and

there are numerous accounts of flooding and the importance of maintaining drains and ditches. The History (1996) under sections on Economic History and Local Government refer to court presentations in the 15th and 16th centuries on the failure to scour ditches and watercourses (page 44), and, while the Thames Valley Drainage Acts of 1871 and 1874 made provision for drainage improvements, flooding and poor drainage often continued to make farming difficult (Deanery Farm in 1876 blamed the failure largely of defective drains laid a year earlier which could not cope with two excessively wet seasons (page 31). These “scouring” responsibilities, shared between riparian land owners and tenant farmers and the management of the waterways were and still are contentious. Jim Buckingham, who from 1968 worked for the Thames Conservancy, which then became Thames Water, then later the National Rivers Authority and now is the Environment Agency, tells us of his previous responsibilities of “maintaining rivers, cutting weeds and clearing trees, responding to floods, blocked rivers, as well

as reading river gauges and depth markers, and working over a large area, just a small part of which included Shill Brook, Highmoor Brook, Radcot Cut, Great Brook and a section of the Thames, which were most local to home”. He has numerous stories of past flood events, as do many residents of Bampton and Weald, including from the recent 2007 flood. Some improvements have been made since, but more are needed, including the ongoing need by those responsible to ensure that ditches and drains are effectively “scoured” to ensure that they are effective.

Mill Green, January 2007

Bridge Street, 21st July 2007

Mill Green 2007

Water Contributing to the Local Economy

The productive farming land and proximity of brooks supported the establishment of mills from an early time. In 1086 4 mills were recorded in the Manor of Bampton; one was presumably the later corn grist mill to the north of Mill Bridge (now Bridge Street) which was demolished by 1899. Another was attached to Bampton d’Oilly Manor. There are various records of the leases and rents charged for these mills over the centuries (see The History, 1996, page 31). Oxfordshire Mills by Wilfred Foreman (1983) also makes passing reference to various mills in and around Bampton including by Highmooor Brook, and in Black Bourton (at Mill Farm and still visible), and lists the 14 millers in the Bampton Hundreds in 1280, of which 3 had the name Miller! The names of other houses along Shill Brook recall the past existence of mills, as does Mill Green in Bampton.

Fisheries are also mentioned in old records including one near the Deanery where there were fishponds, and at Ham Court, and also attached to Bampton d’Oilly Manor (The History, 1996, pg32,) and presumably Fishers’ Bridge on the Buckland Road takes its name from these activities. As Giles (1848) recalls fish abounded in the brooks. Older residents can also recall that fish were once plentiful and there is a nice account of crayfish present provided by John Pullman (courtesy of Jo Lewington) below. These stories visually illustrate the loss of life in our streams from pollution and mis-management.

Whitsun 1932, Ethel Townsend taking in bread after flooding

Crayfish- Memories from John Pullman

Crayfish are strange private angry creatures - and I will always associate them with summertime in Bampton.

This book and others on mills and their widespread influence on Oxfordshire’s development can still be explored and obtained online.

My parents Anna and David lived on Mill Green for twenty years from 1993, in a cottage surrounded by water. Shill Brook ran along the back of the house, and down the side of the garden. My family visited often and my three young daughters and I soon discovered the stream was full of life. We’d see fish hiding in the shade of the banks as they swam against the current. But crayfish were the highlight. You’d rarely see them in the daytime, but wait for twilight, then shine a torch down into the water and the stream’s bed would come alive. The grey/ green creatures like small lobster, one claw bigger the other, would scuttle around, trying to hide from the light. It was easy to scoop them up with a net.

You’d pick them up by the shell to avoid their snapping claws and then drop them in a bucket

of stream water. They weren’t big - an inch or two long - but strange enough to scare a child; like tiny prehistoric creatures with mottled shells and many legs. They’d often fight amongst themselves, and if you left them in the bucket overnight, you’d wake up to find several missing. We learned that crayfish are cannibals - especially the North American signal species we found here.

Once or twice we tried cooking them. Catch a bucketful, put them in the freezer for an hour to send them to sleep, then drop them into a pan of boiling water for a few seconds. The shells instantly turned pink. Leave them to cool and peel off the shell to find the meat. It was tasty, but a lot of work for not much reward. Still, it felt special to eat a sandwich made with something you caught in the stream. My girls are adults now, and my parents moved elsewhere in Bampton after being flooded twice. Shill Brook has changed, and when I walk along it these days I never see crayfish.

Mill Farm, Black Bourton

Tanning was probably another important economic activity in Bampton and Weald which benefited from nearby livestock (skins of sheep and pigs, and hides of cattle), easy access to water (Shill Brook) and bark from trees (the name Weald means woodland). Tanning then was a messy business involving washing off blood, dung and dirt by a stream, removal of flesh and hair, and then soaking of the leather in pits containing urine and lime.

of the water for dressing alum leather (all in The History; 1996; pg31). For more information on tanning and the making of leather goods including gloves in Bampton, please see the excellent Archive publication on The Tanning Industry in Bampton by Miriam James and Jo Lewington. As noted, probably the most compelling evidence of this old industry now exists in names with a disproportionate number of “Tanners” among local inhabitants, and indeed the adoption of the name “Tannery Gardens” for a new housing development.

Other local names also tell us more about past activities that might have impacted on the watercourses and lives locally. For example, Moonraker Lane was once called Slaughterhouse

You can imagine that the pollution and health hazards from this industry were significant. Although there is limited evidence of this industry today, there are references to fellmongers, leather dressers and glovers in the town in the 17th and 18th centuries and possibly tanning pits to the west of the Market Place, probably behind Rosemary House, uncovered later in the 19th century, and there was an advertisement in 1799 for a house near there that comments on its suitability for a fellmonger and on the excellence

Chapter 2 WELLS AND PRIVIES - HOUSEHOLD PROVISION

The Role played by Wells and Privies

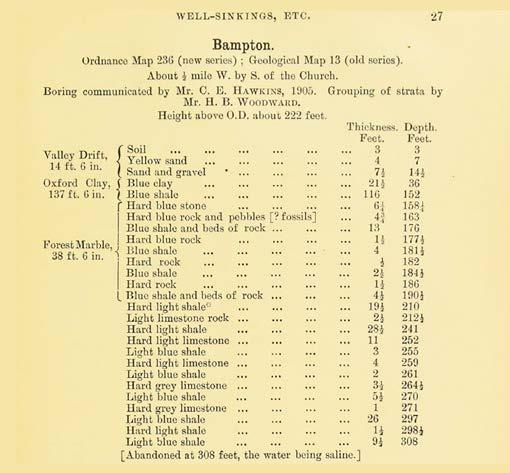

Bampton and Weald are characterised as an area of gently rolling clay vale (Oxford Clay) overlain with superficial alluvium deposits (Valley Drift) which increase in depth to the south, forming low-lying meadowland nearer the Thames that is subject to regular winter flooding (Will Fenton; Mapping Bampton; 2023).

Records and a Survey of Our Wells

Information on wells has been obtained via online literature searches, from the Ordinance Survey map published in 1899 and from existing publications in the Bampton Community Archive, and posts on the “Memories of Bampton” website, supplemented by a survey distributed to older properties in

Lane, and names like Mill Green, Fishers Bridge, and Sandford Field must link to past water uses.

The above briefly illustrates how water has impacted lives locally over the centuries, and so now to dig deeper into how past Bampton residents have accessed it for drinking and household use and how we have returned it to the environment and sometimes failed to keep this essential resource and ecosystem safe.

The geology of Oxfordshire (Map from Oxfordshire Geology Trust)

The area is intersected by brooks, notably Shill Brook, and sustains a high groundwater table. This lent itself to the construction of hand-dug wells that tap into the shallow, unconfined aquifer. The wells were typically stone-lined with the water hand-drawn or fitted with a hand-pump. Records of such wells go back centuries (Giles, 1848) and their design remained little changed over time until they gradually fell into disuse with the arrival of piped drinking water supplies. How have these wells supported life in our village in past times and shaped people’s lives?

At the same time, it is also important to consider the related challenges in the disposal of human waste (night soil) and how this was dealt with. A growing population and pollution issues led in time to the provision of municipal piped water supplies and mains drainage systems, with different challenges and these are dealt with in the next chapter.

11

the Bampton and Weald area. Conversations with older residents, including members of the Bush Club, have also yielded valuable memories and anecdotes. A total of around 50 wells were mentioned in response to the survey or in conversations with residents of Bampton and these are summarised with short notes in Table 1 included at end of this chapter. Many wells, while remembered, no longer exist, having been capped, often for safety reasons, or built over due to house extensions and the like. This table is not exhaustive but it is intended to give a sense of the wide-spread distribution and use of these wells and water pumps in the village and provides a framework for telling some of their stories.

Where feasible we have also included notes here and in Table 1 of the existence of privies, as the limited volumes of water obtained from using wells

Tanning Industry in Bampton

meant that a separate method of disposing and collecting human waste was required. What in fact is a privy? Its definition is of a toilet located typically in a small shed outside a house (and also implies something secret or secluded). By their nature, many have not survived but there are still a few great examples locally!

Well Construction

The wells in Bampton and Weald were typically hand dug in the upper layer of sand and gravel deposits to access the shallow sweet groundwater in the upper aquifer, typically just 10-15 ft (3-5m) below the surface, and were lined with stones for stability. Below this is a thick layer of impermeable Oxford Clay which for practical purposes limited the depth of wells. There is some evidence that underground streams flow at this interface and some wells tapped into these streams. Deeper still, below the clay, there are layers of hard rock and shale where water is again encountered.

Building these shallow hand-dug wells was often a mix of technical skills and risk management. Typically, a wooden frame of hard wood, such as oak, was placed on the ground and 2 or 3 layers of stones placed on top, and the earth dug out from under the wooden frame which sinks under the weight. Further layers of stone were then added and more earth dug away, and the well progressively deepened until water was encountered. Jo Lewington has a great account of the reconstruction of her well at Sandford Cottage and also how this well was used in the past, shared between two cottages.

Jo Lewington’s well at Sandford Cottage:

The shaft of the well was built with stones and the top above ground was built up with large flag stones. My well is about 15 ft deep maximum. When I repaired my well last summer I dug down until I came to the original wooden frame – still intact. It has only a couple of feet of water in it, but I have never known it to go dry. It was used by the inhabitants of Sandford Cottage until water came in ‘mains’ in the 1950s. The water was pulled up by buckets attached by a sort of dog-lead-clip attached to the end of a pole. Mrs Whitlock (next-door) could be heard collecting 2 buckets full at 6 in the morning and another 2 buckets at the end of the day. She said it was known to be “the best water in Bampton”. It was tested annually for free by the local authorities (quite different to nowadays when we have to pay to ensure our water is fit to drink). I remember there were always tiny black flatworms on the inside of the buckets which came up with the water. They didn’t bother us. We did no filtering or boiling. I do not remember if Mrs Whitlock collected more on washing days but both Sandford Cottage and Brook Cottage next door have steps going down to the brook, which I have always assumed were for us to do our washing. My well was in use in 1952 when my mother bought my cottage. It needed clearing out in 1989 when I came back, because it had not been used for the 30+ years that I had been away. It was fairly silted up and some of the upright flags around the top had collapsed. On 2 occasions, dogs have fallen in and had to be rescued. The first time, I went down the well with a ladder and pushed the dog up from underneath (no harm done). On the second occasion, with a hysterical owner at the top, and me being older, I had to call in a chap from Sandford Field and send him down – again no harm done. Now I have restored, de-silted, and built up the well for the second time. I have replaced the large flagstones around the top and I don’t think anything could fall in.

I was intrigued by the reference above to the steps going down to Shill Brook to facilitate clothes washing. There are also suggestions that these steps and other access points known as “dipping holes” were used by local folk to clean poultry and flush clean the intestines of pigs which were then used to make sausages and/or chitterlings. It is worth recalling that most households had chickens in the backyard and a pig or two, and that a near-

by running supply of water was most convenient.

Jo Lewington’s interview with Vera Elward on “Her Whole Life in Bampton”, now on YouTube, makes

reference to this context towards the end of her interview.

Jo Lewington’s Well - interior

Steps down to the Shill Brook

A well that is inside the kitchen of Castle View farmhouse

Jo Lewington’s Well - exterior

Richard McBrien of Cobb House offers us further insights into wells and their reconstruction!

The well at Cobb House:

We found this well several years ago, after doing some landscaping work. It is flask-shaped, which is apparently quite common, with dry stone wall construction, so that water seeps in from the sides as well as appearing at the bottom. We had it dug out manually a further 1.5 metres or so by a rather eccentric company that specialises in this sort of thing - https://www.wellmasters.co.uk.

They are very interesting in their own right. We now use the well to water the garden. We also have a filled-in well in the cellar too.

I have added a few extra notes of my own following a visit: This well is about 4m deep and now has a glass cover and light, and is fitted with an electric pump to fill a tank for garden irrigation. The old hand pump is still attached to the adjacent garden wall. Richard mentions the role of underground streams and a possible intriguing link is that when the Deanery used their well to fill their pond a while back it caused the Cobb House well to run dry which was a first in

memory, so perhaps these wells are inter-connected via an underground stream?

The digging of hand dug wells and their restoration was and still is a skilled but fraught business as WellMasters website explains, and as some of our local well stories illustrate. WellMasters is a small family business that can trace its involvement with hand dug wells back to 1821 and they still dig, reinstate and maintain these wells and hand pumps and associated fittings, and are keen to promote this aspect of our water heritage.

Well Digging - Extracts from the WellMasters website www.wellmasters.co.uk.

Traditional well digging was a hard and dangerous job but it was relatively well paid; not unsurprisingly as there was a reported death ratio of 2 in 5, but without well diggers people had no water, so demand was high. Wells were ubiquitous but there are no official records of hand dug wells. Nevertheless, whether digging or restoring or cleaning a well you always end up with a cold bum. Near the bottom and often even after just a few metres from the top, water enters the well and trickles down the sides of the well walls. Typically, well linings are open-jointed with the stones or bricks just placed on top of each other, although the top 1-2 m of lining is often mortared to stop surface water run-off from contaminating the well. Some recent 20th century wells have used curved fired bricks but usually they are made from normal rectangular engineering bricks set at an angle on top of each other. With around 272 bricks per meter of well the current cost is about £250/m for the bricks alone. Wells are on average 100cm diameter so inevitably you find that when bending down your bum touches the sides pretty much most of the time, which means a wet and cold bum. This is not exactly a perk of the job! Hence, the well-known expression (?) “It’s Colder than a Well Diggers arse”. Just don’t ask!

Another aspect that is oft forgotten is that wells need cleaning as with age and neglect the flows in and out of the well are reduced, hence well scrubbers were needed. They would come in 5-10 years after the well had been dug and every 10 years after that to clean/scrub the well to ensure that it was safe to drink. After the First Wold War well diggers became less available and well scrubbers were often children (perhaps this was an alternative to cleaning chimneys!), and during the wars, many women became well cleaners because most of the men who had dug or specialised in wells were not around. Later, after WWII mains water started to become much more widely available and the need for this job started to die out.

And so to continue, well restoration and their maintenance can be a fraught business.

Story of Sam and Adrian Smart’s Well at 1, Primrose Cottages:

About 30 years ago (early 1990’s), Sam and Adrian noticed that their lawn showed a circular dead patch near the front of their house and discovered the outline of an old well lining and started to investigate. One thing led to another and following some excavation of the old well shaft and retrieval of all sorts of the usual well debris such as old bottles, china etc. they came across some WWII munitions including a hand grenade and various bullet clips. Interesting stuff and they thought, just like I would, why not put this on the mantelpiece! Later on though someone suggested that this should be checked out and the police were called. Huge excitement in a quiet village in the 90’s for our local PC who called the bomb disposal unit and said hand grenade was exploded in an adjacent field. Yes, it was alive! Was this just a Home Guard conscript happily disposing of his WWII obligations down a handy well? Any thoughts? The well now looks good with new lining and frame added to the top. There is another old well linked to this property that used to serve an old livestock building, and in total the four Primrose Cottages shared two wells between them.

Cobb House Well hand pump

Cobb House Well and cover

Cobb House well - interior

Excavating Smart’s well

Emergency services at Smart’s well

Adrian recalls that even when piped water supply arrived it consisted just of a single shared standpipe in front of the cottages. There were also two privies at the back shared between two cottages each.

Nigel and Jane Wallis’ Well at 2 Castle Mews:

Nigel’s interest in wells was stimulated by seeing a pamphlet on “Building a Well Safely” from the Centre of Alternative Technology, Machynlleth near Aberystwyth. Knowing that the water table is quite high locally he had to try it out.

Also, Nigel’s grandfather was a dowser and so Nigel had grown up seeing this skill being used, and he did use dowsing (a pendulum in this case) for this job to check on the best site although as Jane observes one does not really need to be a dowser to find a good well site in Bampton. Jane is also interested in the spiritual and healing aspects of dowsing. So these interests run in the family. They built their first well at 2 Castle Mews; the well is still there and the new owners continue to use it.

They found that the gravel layer starts 2-3ft down and water table is at 5-6ft depth. A wooden ring was initially laid at the bottom of a shallow dug circular hole (any wood is suitable for this type of construction). Then the first few layers of bricks are placed on top of the ring, mortared and allowed to set. The ground underneath is then excavated and the mortared ring sinks. This technique provides protection for the digger. Quite a few fossils were encountered during the excavation. Mortared engineering bricks were used in the construction right from the base to the top, hence the well walls are effectively waterproof, and the water enters from the bottom of the well.

Once the well reaches the required depth, it is capped and a manhole cover inserted, for future access. The hand pump, which is lift or suction design, was offset from the well (see photo). Waders are also clearly an essential part of the modern well digger’s kit!

What is a suction hand pump and how does it work? The diagram below illustrates a suction pump typical of the hand pumps that we have found here, and similar to that used by Nigel. The maximum lift is about 7-8m and the pumping cylinder is above the ground for easy access for maintenance, so is well suited for Bampton’s environment. The suction pipe can be installed in a borehole casing but, given the high water table and strata here, it was typically placed directly into a hand-excavated well to draw up the water. One disadvantage of this type of pump is that it may need to be “primed” by adding water to the cylinder if the suction valve starts to leak over time. This can often occur with the old leather piston seals.

The Well at the Allotments on Bridge Street:

When a well was suggested for the allotments on Bridge Street, the same construction technique was proposed as for the well at 2 Castle Mews. The photos available show the whole construction process.

First, a circle of wood was laid on the ground to mark the size of the well and where it was to be situated. Then, the initial part of the ‘hole’ was dug out without the wood circle in position, and once it got to a depth where it would have been unsafe to continue without supports to stop the earth falling in on the digger, the wood circle was placed into the hole and the brickwork placed on top. A few courses of mortared bricks were built on the wooden circle and then it was undermined to allow it to sink down further and then the whole process repeated once the mortar had hardened in the first courses - it was then repeated again and again until it got to the desired depth.

Exploding of WWII ordinance Smart’s well

Nigel and Jane’s well construction

Nigel and Jane’s well excavation

Nigel and Jane’s completed well

Allotment well excavation

Allotment well excavation

As the digging goes on, the diggers have to descend to the bottom of the well and the last digging was done in very wet conditions, especially as here the well is adjacent to Shill Brook and is about the same depth as the bed of the brook. A small pump had to be used to remove the water in the well during the last stages of work. Again mortared engineering bricks were used here as at 2 Castle Mews, and an offset suction hand pump was installed. In total, Nigel estimates that the well cost around £1,000, covering the cost of engineering bricks and mortar, and the pump purchase. A simple water testing kit was used at the end to check the quality of the water obtained and it was good.

Plenty of debris was encountered during the excavation of this well, certainly in the first three feet, as it was probably the site of an old midden, and also included excavated material from the adjacent brook. The work was undertaken in 2015 and involved and was shared between all those with an allotment on Bridge Street. “It was a very gratifying job, and everyone seemed to enjoy it and had a sense of achievement when the well was finished and the hand pump attached. The well always has a plentiful supply, even in long periods of dry weather and of course is free”. However, this spring 2024, the allotment holders had to rally around again to arrange for the repair of

the pump as priming no longer worked, and a new valve needed to be installed. This was quite a challenge but the pump now woks again the sense of team work continues.

The high water table and alluvial soils in Bampton and the Weald meant that the siting of these shallow dug wells was not too critical, but the inflow to some wells was enhanced by deliberately siting them to tap into underground streams and by their design. An example of well-siting linked to an underground stream is perhaps the three wells located in a line from Yew Tree Cottage on Church View, to Thatched Cottage and Tudor Cottage, both on Church Street. The well at the back of Yew Tree Cottage no longer exists as it was covered over as it coincided with the footings of a kitchen extension but Jackie Wheeler notes the diagonal line from this well to the one to the rear of Thatched Cottage, where there is an existing hand pump that is connected by a lead pipe to an old well below the basement. The cottage is currently under renovation but the previous owner (Mrs Linnet Sanguine and before that, her parents) used the hand pump to fill a tank adjacent to the hand pump in their conservatory in which she kept goldfish.

Probably an underground stream in turn links to a splendid example of a stone-lined well in the conservatory of Tudor Cottage, which has been restored and has a glass cover. This is of a kettle (or flask) well design where the well diameter expands towards the base to enhance water inflow. It is also notable that the water in this well is clearly flowing.

While accessing ground water is clearly not too problematic in Bampton, dowsing skills are still handy to locate the most productive sites whether using a pendulum or metal rods or twigs to find water in the ground or locate leaks. I have been given two L-shaped copper rods that perhaps belonged to Nigel or another dowser. If interested in finding out more about this, have a look at British Society of Dowsers website (www.britishdowsers. org), for both practical water dowsing and also the health related aspects of dowsing. Past visits to Bampton from various dowser groups have identified strong energy lines in the water that is flowing under the village. Despite the interest in the existence of underground streams in Bampton, I have to date not been able to locate any old maps of these streams but the search continues.

Hand and machine drilling techniques for wells have evolved over time particularly where deeper wells are required (see the next chapter on the development of our village piped supplies). But we have an interesting example of combining old and new technologies in the well sunk recently at Westbrook House.

Allotment well excavation

Allotment well maintenance

Allotment well in operation

Tudor Cottage Well

Thatched Cottage hand pump

Westbrook House Well; Nick Thorpe:

This is a good example of more modern well digging. This new well is in the garden of Westbrook House. It was drilled in December 2020 and the installation completed in April 2021, and it is now used for garden irrigation. It was sunk using simple percussion drilling technique and a cutting tool. The borehole depth drilled is 5.5m and is capped by a manhole cover. The suction tube is inserted into the borehole and connected to an off-set electric pump which draws the water to a tank. Irrigation controls control pumping and ensure that the garden is irrigated as and when required and automatically cuts off when rain is detected thus saving electricity and manage the use of water. Rather different to the traditional open wells of days past!

Tudor Cottage-Well interior

Nick Thorpe Well drilling

Nick Thorpe - irrigation using well

Shaping Lives - Wells and Privies

Water is essential for all life and how we have accessed safe drinking water, and indeed the safe disposal of our waste, has crucially shaped lives in the past. Collecting safe water was time consuming (and still is in many parts of the world) but the use of simple hand-dug wells transformed lives in Bampton over past centuries and for many their use continued to shape the daily pattern of family life here up until the 1950’s. Well water would have been drawn up by hand in buckets or large water bags and later using hand pumps, of which examples can still be seen.

Table 1, at the end of this chapter, summarises some of the wells that have been remembered and discovered in Bampton and Weald but there would have been many others that are now forgotten or have been covered over by house extensions. The Ordinance Survey map of 1899 shows various locations either labelled as wells (41) or pumps (55) where a hand pump had been added, and many of these also feature in Table 1. In practice, all households would have had to have some form of access to well water, and the distribution of wells and pumps throughout the village would have been extensive. If you could afford it and had the space, a well would serve a single household but many wells were shared between adjacent cottages, and of course, the larger houses often had several wells for both the house and garden, as did local farms serving the farmhouse, livestock and farming activities. While many villages in the 18th and 19th centuries would have also had a village well (or wells) for communal use, there is no evidence of such in Bampton – more on this later on!

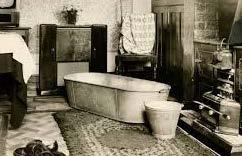

The collecting of well water by hand meant the volumes used by households were limited to essential drinking, washing and cooking uses, and human waste disposal was done via pit latrines in gardens or privies and organised night-soil collection. Given the nature of privy structures, much less evidence remains of these but we have tried to develop this narrative in parallel with the use of wells, and, later on, as water use increased, so did the use of septic tanks and eventually sewer systems. But first, how did Wells and Privies shape past lives in Bampton and Weald!

The Bampton Archive Publication; The Way It Was, by Freda Bradley; published Bampton, 2001, provides a wonderful starting point from not so many years ago!

Our house- when I was three, my family moved from Lavender Square to what is now Bushey Row. We moved into one of the first of twelve council houses built; six were in New Road, numbers 1-6, and six in Bushey Row (which was then also called New Road), numbers 7-12. This would have been 1930; we were in number 11. There was a stone sink but no running water. All the water for cooking and drinking had to be carried from a pump over a well, which was situated in front of the middle two houses that was the supply of six houses. We had a very big rain water butt outside, which was used for washing hair and bathing. The water was heated in the copper (in the scullery which had a fire underneath to heat the water), then in came the old tin bath and we all had to go through. This happened once a week, but I can assure you we weren’t dirty. Mum made sure of that; we got washed down every night before going to bed (ref: Page 6; The Way It Was).

There was only one lavatory down the garden. When I was three, I would go with my gran when she had to go, and sit in the corner on a three –legged milking stool. Granny wore combinations, which was a long sleeved vest and long johns, an all-in-one under garment. It had a flap at the back that buttoned at the waist and she used to take this down to do her “business”. Shop bought lavatory paper in those days was little square sheets of paper, sort of slippery, not soft, with the trade name Izal. But most people improvised by tearing newspaper into squares and making a pad of them, which would then have a hole pierced in one corner, and a piece of string passed through and tied in a loop and then hung on a nail on the wall (ref: Page 4; The Way It Was).

As sewerage did not come to Bampton until the 1950’s, it was all bucket lavatories, which had to be emptied every week. The buckets were stood at the side of the road on Wednesdays, and the man who did this was Horace Morse. He came around with his horse, pulling a round tank on wheels into which he emptied the buckets, and then this was spread on the farmers’ fields. He also collected the ashes and rubbish in a high-sided square cart on a Thursday, and he emptied all this along the sides of Gog Lane.

My brother used to like to go with Horace on the cart, because he loved animals and to be able to help with the horse was just what he liked. One day he was late getting home and Mum was quite worried. She said “where on earth have you been till this time?” His answer was “Up in ‘orace’s ‘orse’s bedroom”, which was the loft above the stable. The horse was stabled at the Old Forge. It is used as a garage now, and the double doors are still there. (ref: Page 10; The Way It Was).

We have collected numerous other lovely stories and memories of having and using these wells (and privies!) extending back to the 1940’s that offer great insights into how these services have shaped lives.

Don Rouse’s story about bath time

This brings me on to a really lovely subject. The home copper. Monday was Wash Day. And then Wednesday or thereabouts the copper would be used to boil up all the scraps, vegetable peelings and cabbage stems and all the rest of it for the pigs and chickens. Then on Saturday you hoped that mum had cleaned the copper out properly, because it was bath day whether you needed it or not. Dad set the copper going again.

And I remember to this day there was three of us in the bath, my elder brother and myself and my sister in the tin bath in front of the fire - when we had washed and needed to rinse off the water had got very chilled so dad filled a tall white enamel jug from the copper and poured nice hot water pour over our heads. I can feel it to this day. Lovely!

Tom Tanner remembers being put in the bath directly after his mum finished the wash because the copper

Farmyard with buckets

Madeline Read and water pump

was emptied into the bathtub while it was warm. So Don, what do you recall about those suds? “It didn’t matter because the clothes were scrubbed with Lifebuoy Soap and so were you”

David Rose; Wells and Privies at Windsor Cottages:

David was born October, 1943 at 4 Windsor Cottages, Broad Street and recalls the water supply for all 5 cottages was provided by a shared well behind numbers 3 or 4, which had a hand pump on top. This was no longer used once piped water supply became available and was later capped and covered over due to recent house extensions. David remembers how in cold weather the pump used to freeze up and his mother used to heat a kettle to unfreeze it. And also how people nearby already on mains water used to have to collect water from the well when their supply failed. Many households only connected up to mains water when the sewer network was installed.

All five Windsor cottages had a privy in their rear gardens. These were some distance from the well given the length of these gardens. This row of privy structures fortunately still exists as they are listed although they now serve different uses. The adjacent Victoria Cottages had a similar servicing set up with a shared well and a line of privies at the rear of their gardens (which are visible on GoogleMaps). Windsor cottages were built and owned by the Benfield family, which might account for them having similar servicing arrangements.

David recalls that night soil was collected was once per week by Horace Morse and his horse, a large dray called Snowball, and a cart. It was taken to Gog Lane, just off the Aston Road and spread on fields there, which accounted for some sizable vegetables. Horace used to live nearby in Rose Cottage, between Windsor and Victoria Cottages. There are many stories about Horace and his cart.

David also remembers that in those days there were allotments at Calais Dene and there were many open wells in these allotments (also recalled by Tom Tanner).

The auction catalogue for the Benfield Estate of 22 September 1982 provides further evidence of the continuing existence of outside WCs (privies) in many properties in Bampton in the 20th century through its descriptions and the lot diagrams, and this includes 2-4 Windsor Cottages, Broad Street; 1 and 2 Belgrave Cottages and 1,2,4 and 5 Bourton Cottages, all in Church Street.

A similar arrangement also served 1-4 Albion Place cottages on Bridge Street, adjacent to Cheyne Lane, where there is a line of well-preserved privies, which are also listed, at the back of their gardens and can be accessed from a doorway in Cheyne Lane, including one that retains the original toilet seat structure. These cottages most likely also had a shared well located in the back gardens.

Madeline Read and cousin (Bathtub)

Gran bathing Frank Hudson back of Castle View

Tin bath tub

Windsor cottages privies

Albion Place Cottages privies

Albion Place Cottages - privy detail

More Memories of Well and Privies from Ron Amos:

I used to live at 2 Primrose Cottages in Weald until 1960 when I got married. The restored well previously mentioned was used by Nos 1 and 2, and there was another well at the other end for Nos 3 and 4. There was no mains water, gas or electricity supply to these cottages until 1957 when mains sewerage came to Bampton. Flush toilets were introduced a bit later when the cottages were bought by Count Munster who lived at Bampton Manor. The cottages are all individually owned now. I would imagine that only properties that had a well still being used during the above period were the more isolated cottages like the ones at Primrose Lane. When I lived there, I recall that a young girl who lived at No 4 fell down their well and her father had to go down to get her out.

You also asked about the toilets at Primrose Cottages. There were two blocks behind the cottages each having a shed containing a fire place to heat water in the copper. Next to this were two toilets back to back containing a wide seat with a toilet bucket beneath; these were considerably bigger than a normal one with a carrying handle and a side handle. Most of the houses in Bampton had these before 1957 when the mains came. Some with large families would dig a trench in their garden and bury the waste and when full, dig another pit. Years ago there were quite a few families in the village with up to 12 children so you can see what a problem that was.

The buckets usually had to be put outside your premises to be emptied once a week, in our case on Tuesday morning when a man called Horace Morse would come with a horse drawn tank on wheels to empty them. I imagine he must have taken several days to get all round Bampton. I must tell you a joke about Horace that someone made up. A chap saw Horace poking a stick in the tank of sewage and asked what he was doing. Horace said “I had my jacket hanging on this hook and it fell in”. The chap said “Well, it was an old one”, to be then told “’I’m not worried about the jacket but my lunch was in the pocket”. (Ed: It is funny how ubiquitous these tales are!)

There have been a lot of changes since I was born here. Hope this has been helpful to you, Ron.

If you are observant when going around Bampton and Weald, a number of circular walled flower beds can be spotted in gardens around the village which would have been old well structures (Bushy House, Chantry House and Well House for example), and Spring Cottages in Primrose Lane which had a nowburied shared well at the front, but had another well still visible in the rear garden as a raised circular flower bed. These glimpses all show the once widespread use of wells, both individual and shared, supported by the other information we have gathered (Table 1).

The larger houses and farms relied on very similar systems for their water and waste disposal, while often having multiple wells. Weald Manor offers a useful comparison.

Weald Manor – from conversations with Rosemary and Michael Pelham, and Sylvia Nicholson: There were at least two wells at this property, one in the kitchen and another in the orchard but probably others.

Sylvia who still lives in the Lodge to Weald Manor worked at the Manor for 30-40 years, initially as a nanny for Major and Rosemary Colevile and then returning later, after a spell spent working for Witney Blankets, as a cook for Rosemary and Michael Pelham. Sylvia recalls the well near the kitchen where the kitchen maids used to pump the water up from the well into a tank that fed the boiler which also provided water for kitchen use. In those days there were 6-7 staff at the house (4 in kitchen and house and 3 outside). She thought the Manor was served by the sewer network for a while before being connected to the piped water mains because of the wells. She also recalls the night soil collection system and there is still a small doorway in the wall along Weald Street where the buckets of night soil were collected by the ubiquitous Horace Morse.

Rosemary also recalls these wells and the well in the orchard which still exists and is stone-lined with a wire mesh cover over it for safety. There is a story that a tractor driven by Christopher Collett once went into this well when it was more a farmyard. The previous Manor gardener, Francis Shergold, used to look after this well and the gardens. There is some evidence of other wells in the gardens and stable area. Rosemary and Michael also explained how water shaped the past and current layout of Weald Manor - storm drains collected rainwater from either side of the house and channelled it under the road (Bridge Street) and into the Ham Court drainage ditches (this was once a ford across the road). To the south corner of the property, there is an old 19th century lake which is fed by springs to this day. On the opposite side of the estate by Weald Street there is a water retention pond for managing runoff from Weald and for controlling a steady discharge under the road and into Shill Brook. It is fascinating how water and its management have shaped the development of this property.

Chantry House Well Flower bed

Spring Cottages - Well flower bed

Weald Manor Well in orchard

The farms around the village also often had multiple wells. Colin Rouse recalls three wells at Backhouse Farm in and around their yard, mainly used for livestock watering. These were all shallow with hand pumps attached, and interestingly there was one by their backdoor that was fitted with an electric pump and this was used to cool milk. Water from the well was pumped up to a tank and then channelled down through a heat exchanger with the milk running down the outside and the cooling water on the inside. The base for this well/ pump structure still exists, although the use of this technique ended in the early 60’s. Deanery Farmhouse and Home Farm are among others also reportedly to have had two or more wells for the farmhouse and their yards.

8. There were 6 thatched cottages in the yard (all were one-up-one downs) which had no sink; just a chair inside the door with a bucket of water for drinking (presumably this was drawn from the well at the top of the yard opposite the Tanner/Butler cottages). There was a row of privies at the end of the garden. Just beyond that there was the Brook, and there was a “dipping hole” for accessing water for the garden and general cleaning purposes (preparing chitterlings etc), similar to the other dipping holes in Bampton alongside the Shill Brook.

The Hazards of Wells

But what about water and waste provision in the poorest and most deprived areas in Bampton and Weald, such as Slaughterhouse (Moonraker) Lane, Rosemary Lane and Workhouse Yard in Weald? By their very nature and subsequent site development, very little physical or documentary evidence exists but some long memories can help. Janet Rouse refers to an earlier exchange with Vera Elward (see her Archive interview “Her Whole Life in Bampton”) who recalls life in Workhouse Yard, Weald during the 1920’s and its various resident families (then the Hunt, Poole, Tanner/Butler, Dewe and Collett families, plus a next generation of the Hunt family), Vera was born there and left in 1931, aged

There are numerous local stories of people and children falling down wells and needing to be rescued, such as the earlier mention of the girl falling down a well at Primrose Cottages and having to be rescued by her father, and wells being capped for safety reasons. Perhaps the saddest story is of a carter who used to work for Castle View Farm. He used to live down Cheyne Lane just on the far side of the bridge over Shill Brook. One morning he failed to turn up for work and after a search was carried out, he was found drowned, having fallen down the well that was just outside the wall of Castle View farm which was near the gates now leading into Brook House. This was in about 1941. Subsequently this well was capped.

Steve Radband also recalls that there was a well in their garden in New Road which his father filled in and capped when he was a kid so as to avoid the risk of the children falling into it. There must be many other wells that were capped for similar reasons.

Interior of door for night soil

Weald Manor, night soil door in wall in Weald Street

Weald Manor Lake fed by springs

Home Farm

The Lady Well

There is a reputed local holy well known as “The Lady Well” located at Ham Court and its location is shown on the 1899 Ordinance Survey map. Sadly, although this well seems to have been restored in the mid-19th century, it was later covered again following landscaping work in the 1970’s when excavation waste apparently buried the well.

Location aside, there are various stories associated with this well that we should summarise. It was also called St Frideswide’s Well after the saint who was said to have escaped a proposed marriage by sailing or rowing up the Thames and hiding in Ham Court, and its waters were said to be a cure for eye infections that was linked to the cult of St Frideswide, who according to twelfth century legend, cured a blind girl of Bampton. The Well’s existence is described in some detail by Giles (1848; pages 66-68) below.

Legend of the Lady Well (Giles, 1848)

In the time when the Roman Catholic church prevailed throughout Europe, almost everything was, by reason of some legendary tale, made an object of sanctity or superstition to the people. Wells and fountains, in

particular, were objects of reverence to the Christians, as they had been to the Pagans before the Christian Religion was established. The nymph of the “Grotto” of the “River” or the “Fountain” was displaced and one of the Saints of the Church, the Holy Virgin, or perhaps even Christ himself was installed as the tutelary Guardian of the pure element, which ministers so largely to the uses and necessities of mankind.

In the parish of Bampton are two “Holy Wells”.

Concerning one of these from which a field beyond Cote House on the road to Shifford is still called “Holy well field”, no legend has been recorded but the other has been rendered famous by tradition and its reputation has come down almost to our own times. It is distant about 200 yards from the northern wall of the castle and is so thickly covered with bushes, that a stranger could with difficulty find it without a guide. The field, which lies between it and the Castle, seems to have been formerly used as tilting-area in which the garrison assembled for tournaments and other exhibitions. It is quadrangle, and surrounded by a moat, which is of lesser dimensions than that which protects the Castle itself. In the hollow ground formed by the crumbled sides of the moat, and near its western angle, the ancient well is situated.

The water is still of the most pellucid clearness, sweet to the taste, though much neglected, full of fallen leaves and haunted by vermin. The spot is sufficiently secluded to account for the sacred character which it bears and to have called forth those feelings of superstition or enthusiasm, which were common in the Middle Ages. The stone work with which the sides of the Fountain are protected from the weight of earth and trees, whose roots penetrate through the crevices, is still in tolerable preservation though four or five hundred years have probably passed away, since it was erected. The little nook has in fact, under the patronage of “Our Lady of the Well” been hardly touched by the ruthless hands of the spoiler, before whom the massive Castle and its out works have almost entirely ceased to exist. Tradition informs us that the Fountain first attracted the notice of the neighbouring peasants by the healing nature of tis waters. The cattle of the neighbourhood were thought to be more free or disorders than those which fed on other pastures and in process of time its virtues were found to apply to the peasants themselves. The piety of the church took a hint from the admiration and

credulity of the people and it began to be credibly reported that Our Lady the Virgin delighted to haunt the place, and perform her personal ablutions in the miraculous Well. When this report was sufficiently propagated the inhabitants of the adjoining villages flocked thither in large numbers bringing with them their children and relatives to be dipped in the Well as a certain cure for every species of disease. This practice which we may be sure was accompanied with the payment of some fee or compensation to the guardians of the sacred place continued for many centuries and almost even to the present day. It is only thirty three years since the death of an old inhabitant of the town, Elizabeth Skinner, who had known many children having fits and other diseases carried many miles to be cured of their complaints, by being immersed in the “Lady Well”.

The present generation, however, have ceased to avail themselves of the medicinal properties of these waters which have either lost their virtue or are eclipsed by the superior abilities of the Medical Practitioners to whose charge the health of Bampton is consigned.

The well was restored and inaugurated in 1848 and for a number of decades after that it was reported that the water of Lady Well was used to bathe eyes and found to do them a lot of good. “People used to come from miles around to use it”. This practice continued into the twentieth century according to J.L. Hughes-Owen, 2005, who interviewed a number of elderly parishioners on the subject and noted that

“….all were agreed that the water from the spring was believed to possess remarkable curative properties in respect of complaints of the eye. Several of them told me that when as children, they suffered from that painful affliction of the eye known as a ‘stye’, their mothers would

take them down to Ham Court to bathe the infected eye. And they were unanimous in their testimony to the effectiveness of the treatment.”

Later in the 19th century the well became more associated with the Virgin, and in 1886 it seems to be referred to as “Good Queen Anne’s” well. Perhaps more associated with shrewd marketing by the clergy of Bampton? Although the current owner, Matthew Rice, has made several attempts to detect and find this well, it remains to be uncovered and reinstated, but there is still some hope that we can unearth these secrets. Certainly, Jim Buckingham recalls this well which was lined with flagstones so you could walk down to it and bath in it like a small swimming pool. The previous owner of Ham Court had had it dug out and it was seen both by Jim and his brother Joe, but as mentioned above it was later filled in. Something to be further explored?

Was

there a Village Well?

Several people have asked whether there was a village well, perhaps in the Market Square, and this might have been expected perhaps in a village the size of Bampton, but no evidence exists. There is a depression in front of Thornbury Flats that suggests there might have been a well there but this is more likely settlement from where the old garage tanks were located. J.L. Hughes-Owen (2005) in his “The Bampton We Have Lost” publication does provide some insights into why a village well was never built.

The Battle of the Well, paraphrased from J.L. Hughes-Owen’s “The Bampton We Have Lost”

For long the Chief Fire Officer of Bampton Fire Brigade, had lobbied the Parish Council for an adequate water supply in the Market Square. It was in the days before Bampton had a mains supply and he warned the Council of the risk of a serious fire in the Square, and the Council in 1901 finally decided that a well should

1899 map showing location of Lady Well

be sunk in the ground to the east of the Town Hall, and the Clerk was instructed to obtain tenders for the work. General approval of the scheme was expressed locally. However, soon there were whispers that a certain influential resident, Squire Southby of Bampton House, who resented not being consulted about the well, had decided to oppose the scheme and organised a petition against it. The Council decided to defy the Squire, and still go ahead, but as a matter of courtesy, informed Witney Rural District Council of the project. Not to be beaten, Southby was busy behind the scenes and persuaded the Rural District Councillors to oppose the scheme and claim the power to veto the well. Eventually the Parish Council caved in and opted to drop the project although for a while there remained some bitter feelings locally.

The Parish Council minutes of February 1902 provide some fascinating insights into how contentious this issue was but in the end the idea was dropped.

The End of Privies and Night Soil Collection

The night soil collection service provided by Horace Morse continued into the 1950’s although with the provision of piped water supply in 1906 and water supply improvements in subsequent years, an increasing number of houses abandoned their privies and started using flush toilets and constructed septic tanks and soakaways for the treatment of wastewater. However, Horace and his large dray horse, Snowball, remained familiar sights in the village collecting night soil from the remaining houses on a weekly basis.

horse:

So Horace was a little chap with a bit of a squeaky voice. I’m pretty sure he collected buckets on Monday, Wednesday and Friday and ash on Tuesdays and Thursdays. He had two different types of vehicles, but the same horse. Right. So he was going around with his horse with this two-wheel tanker for the buckets. The tanker was almost the width of the road. You could tell who was of the plusher fraternity and who was of the poor fraternity because when the rich people put their buckets out to be collected they would sprinkle the contents with ashes to stop the smell. But the poor people would just put the News of the World over the top because it was a rather large newspaper. The buckets were slightly oval in shape and capable of holding perhaps 5 gallons.

Don also recounts the story of Horace’s jacket in his own words:

In those days, we would go home to lunch. My Dad had one these baby Fordson tractors with a big long tank and a radiator and when we went home for lunch after hoeing or digging potatoes in the fields about 6 of us boys would sit on the tank like riding a horseour feet on the wide mud guards. We went from Gog Lane up to New Road where we all lived, had lunch and went back to fields. We had just pulled into the gateway to Gog Lane and there was Horace and he had his arm up to his elbow in muck. Dad said to him, “Horace, what on earth are you doing?” Horace said “My blinkin’ jacket’s fell in here”. Dad replied: “Don’t worry, Horace, I’m about your size, I’ve got a spare one you can have”. “Ah”, Horace says, “it ain’t that, it’s that my sandwiches are in the pocket”.

However, the need for improved wastewater disposal was becoming ever more apparent and it took prolonged negotiations and campaigning for mains drainage to be finally installed in the village. Marjorie Pollard, OBE (1899-1982) of the Deanery, who was a County and Rural District Councillor was instrumental in making this happen and long wanted Horace to take his cart and horse down to London and dump the waste in the streets as part of the protest over poor living conditions in the village. Main drainage did eventually come in 1958 but it was really the death of Mr Morse that made main drainage an imperative. The end of an era!

Mrs Jackson, who was Horace’s daughter, often spoke of her father’s work with the night-soil cart, collecting night-soil from around the village.

Tempted to Install a Well?

Can I put a well in my garden UK? Do I need permission for a well? It depends on how much water you think you’ll need! A private land holder can draw 20,000 liters per day of water from a well without an abstraction license. That is equivalent to 133 full baths or around 11,429 pints of beer, so quite a lot, especially as the average UK household uses around 350 liters of water per day, so like Nigel Wallis and Nick Thorpe and the allotment owners at Bridge Street, it might be worth considering.

Don Rouse recalls Horace Morse and his

Horace Morse -collected night soil Mon, Wed, and Fri, and ashes Tues, Thurs

Horace Morse with Snowball

Chapter 3 MUNICIPAL WATER AND SEWAGE: PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE

Introduction

The Witney Gazette reported on 6th June 1891 that Bampton was known, locally, as a very healthy place to live with many people living long lives. This reputation was attributed to the gravelly nature of the soil and the excellent quality of the water.

While the article may be exaggerated to contrast the rural idyll of Bampton with the urban problems of Witney, it is not clear that the quality of the water was as good as it was claimed to be.

Legislation to clean rivers increased the contamination of wells

If the water quality in Bampton was indeed excellent it would have started to change quite quickly after the Thames Conservancy Act of 1866 banned the new flow of sewerage into rivers. Since this was before the introduction of regular municipal collection of night soil, people had to dig and use more cesspits – many of which were

intentionally designed to have porous walls and, as such, allowed liquid waste to seep out and contaminate well water. Contamination from seepage would have been a particular problem in Bampton because of the porous nature of the gravelly soil and the high-level of the local water table.

In seeking to address one problem, rivers full of sewage, the Thames Conservancy Act, created or exacerbated another problem, contaminated well water.

Having said this, the Thames Conservancy Act was perhaps an inevitable consequence of a series

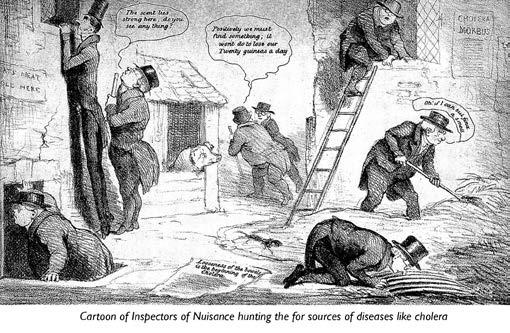

of social and health-related issues and changes starting in 1831 when Cholera Morbus first arrived in the UK and, over a 2-year period, killed 31,000 people.

From cholera to public health and sanitation

The cholera epidemic happened during a period in which large numbers of people were moving to cities to take advantage of jobs created by the industrial revolution. This change increased the number of urban poor who lived in small, cold, damp homes often infested with lice and vermin in areas where there was little or no attempt to empty cesspits or remove putrefying carcasses or other waste.

While we do not know how many cess pits were used in Bampton, we know that 3-5 of them were located in the garden that was opposite #1 Queen Street. Tom Tanner who lives in a house built on the garden in the 1970s says that the cess pits were used by all the residents at the Lavender Square end of Queen Street.

At the start of the 1800s every house would have a cesspit or share one with their neighbours. These were brick chambers, perhaps 6 feet deep and about 4 feet wide. Where possible they were located in the back garden away from the house, but in the centre of cities and in other crowded areas it was more common to have a cesspit in the basement under the household or in shared spaces between houses. Cesspits were often purposely made porous so that the liquid content slowly seeped away and capacity for solid waste was maximised. Even so, they needed to be emptied occasionally and this unenviable task was left to socalled ‘night soil men’ or ‘nightmen’.

Cesspits worked reasonably well until the introduction of piped and pumped water supply and the consequent uptake of water closets –particularly amongst what were referred to as the middle class – from the 1850s onwards. When these water closets were flushed they created surges of waste and increased the level of water making the cesspits overflow. This made the cesspits smell more and, because medical theory at the time held that diseases were caused by “miasma”, the

airborne transmission of poisonous smells, people thought that they were at increased risk of catching cholera or typhoid.

This is where Edwin Chadwick comes into the story. Edwin was a lawyer, social activist and an advocate of utilitarianism – a philosophy which encouraged actions that ensured the greatest good for the greatest number.

In 1832, Edwin Chadwick was appointed secretary to a royal commission that was formed to investigate the effectiveness of the existing Poor Laws and, through this, he started to investigate the economic and health impact of poor sanitation within cities. Edwin Chadwick’s Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain published in 1842 led to introduction of the Nuisance Removal and Diseases Prevention Act in 1846 and subsequent Public Health Acts which, in turn, paved the way for the installation of piped water supplies and sewerage systems. Chadwick is thus the person most responsible for the eventual provision of sewerage systems across the country.

Cess pits, also known as cess pools, or if located directly under a privy as a latrine pits, are different from sceptic tanks.

An early version of a sceptic tank was created in 1881 by adding inlet and outlet pipes to a cess pit below the surface of the water. This created a water seal and enabled the use of anaerobic action to separate liquid from solid. The separated wastewater is allowed to drain away into a type of soakaway (called a drainage field). Sceptic tanks grew in popularity from the early 1900s, particularly in rural locations with no mains drainage.

Local problems with the quality of water

The newspaper articles below and opposite, published in December 1904 and November 1905 refer to issues with the quality of water in wells in Bampton and to samples of the water being sent away for analysis. These articles point the way to the next part of the story: the work of the Bampton Water and Gas Company to dig wells and lay pipes to provide clean water to the whole area.

A pure water supply for the town has become inevitable ever since the inhabitants had to cut off their sewage from the river, and to practically bury it on their own premises. Pure water from private wells under such sanitary conditions as prevail in Banton at the present time is practically impossible. And doubtless a public supply of really pure water will be a great boon to the inhabitants.

Witney Gazette – 24th December 1904

Private investment in supply of piped water rescued by District after 9 years

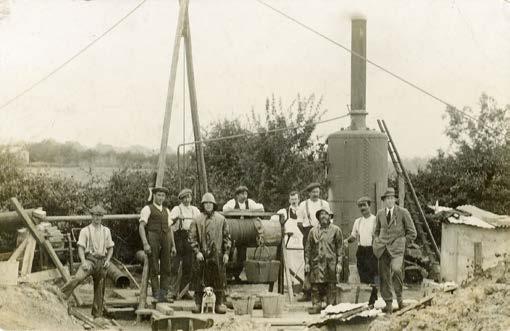

The Bampton District Water and Gas Company wrote to the Witney Rural District Council in December 1904 requesting permission to open the roads in Bampton and Aston to lay pipes to supply both water and gas. This permission was granted in advance of digging a well on land to the south of the Aston Road circled on the map above and shown as the location of the “Witney R.D.C Water Works” Water Tower.

The water company’s borehole on this site was sunk to 308 feet through 14½ foot of topsoil, sand and gravel, 137½ feet of clay and then 156 feet of forest marble and other hard rock. After all this work, the borehole had to be abandoned because the water found at the bottom was saline and undrinkable. The company’s management team must have been quite desperate at this point because they had already started to purchase and layout the gas and water pipes they were going to install.

While the newspaper article refers to the well as 100-foot deep, other sources say that it was, in fact, a sump well with a diameter of 8 feet and a depth of 26 feet and was fed from an adjacent borehole that had been sunk through rock to a depth of 125 feet. The water was pumped from the well at a rate of 6,000 gallons per hour.

Joy Lovejoy who moved into the Bungalow on the site of the well in the early 1960s with her husband, has given us the photograph opposite. This came from a member of drilling crew shown in the picture. While the photograph says 1914 on the back, it may have been earlier unless it is a picture of work carried out after the Water Company had been taken over by the Rural District Council.

Fortunately, the company was able to find an alternative source of water. This was in a field on Station Road in Lew about one and half miles outside Bampton. The well and pumping station were situated alongside the Highmoor Brook on an acre of freehold land purchased from a Mr T. Cripps of Aston.

As shown opposite, this new source of water was described in the Witney Gazette in glowing terms – however, it is possible that this was intended to encourage people to consider signing-up to use the water. More of which, later.

We think that the water and gas pipes were laid in the central part of the village during 1905 and that, the additional pipes required to bring the water from the new well, were laid from August 1906.

The water pumped from this well was taken along 2½ miles of 6-inch delivery-mains pipe to a 15,000-gallon water tank in the tower at the site on Aston Road. This tank was 16-foot square, 9½ foot deep and mounted on 33-foot-high columns.

In February 1907, the company announced a grand opening (see page 42) to take place in March and, to encourage new customers, the company offered to ‘lay on services’ free for the first 100 customers. It is not clear whether this offer was for free water or for free installation of pipes to their property. It is probably the latter. However, the company also

agreed to install 6 fire hydrants and to supply water for use by the Fire Service without any charge. If you know where these fire hydrants were (or are) located, please let us know.

All in all, the water works took two years to complete and cost several thousand pounds. If this was £2,500, the equivalent today would be £250,000.

Private supply of water rescued by the public sector

Having got off to what appears to have been a flying start, a comment in 1908 (copied below), a flurry of comments in 1912-13 and detailed reporting of a public inquiry in February 1913 suggests that things were actually somewhat murky.

While we do not know how many customers stopped taking water, a few years later, the Bampton and District Gas and Water Company went into liquidation and was purchased (or perhaps ‘bailed out’) by the Bampton Parish Council using a loan of £866 from the Rural District Council. The interest on this loan was financed by the addition of a Special Rate. Imposition of this additional cost created a number of protests (one of which is included on page 43); this sound similar to the debates today about rates charged by Thames Water and the bailing out of private sector companies.

The Rural District Council needed to get permission from the Local Government Board to secure/provide the loan. This involved a Public Inquiry which was held on Tuesday 18th February 1913 and reported at length in the Witney Gazette. While the details do not need to be repeated, there are three points of particular interest.

• Despite the positive spin put on the provision of piped water when it was introduced in 1907, it was only taken up by 60 houses. This represented 350 people out of a population of 1,000.

The remaining 650 people still obtained their water from shallow wells. Most of these wells were loosestone walled lined and not water-tight lined. As such they were not protected from surface pollution or the effect of soak-away cesspits.

• The 350 people connected to the mains used an average of 12 gallons of water per person per day. This compares with an average today of around 38 gallons (142 litres) per person per day.

• In the period leading up to the enquiry the Water Company’s well and borehole on the Station Road site had started to dry up and they had to dig a second well. This was dug to 82 ft and provided the additional water needed to supply all 1000 residents at 12 gallons per day. We are not sure if this work was carried out before or after the water works were taken over by the district or, indeed, whether it achieved its target of 12,000 gallons a day before it closed in the 1930s.

While mains water was available to most of Bampton by 1907 – even though it was only taken up by about a third of the population - it appears to have taken another 7 years to extend the pipes to Weald. It would be interesting to know whether the pipes that the Bampton Parish Council had described at a meeting in 1905 as “lying around at the edge of the roads” were left in situ for the whole of the intervening period. While this seems unlikely given that there were complaints about people falling over the pipes in the dark, it is not out of the question!

The first excerpt from the Medical Health Officer’s (MHO) Report in 1935 for the Witney Rural District shown opposite makes it clear that even though the well(s) at Lew had been improved after they were taken over by the Council in 1913, they started to fail from 1921. Despite this, they were kept in operation until 1934 when, as shown by the newspaper report below and the second excerpt from the MHO’s Report, a decision was taken, after a period of drought, to consolidate local village water supplies at the water works in Worsham just north of the A40 near Minster Lovell.

Although supply was moved to Worsham in the 1930s and the pumping station closed, the well at Lew continued to supply low-pressure non-potable water to Bampton Cemetery as shown in the photograph.

We do not know how long Bampton’s water supply came from Worsham but think that it probably now comes from the Farmoor Reservoir.

Sewers date back to 3,500 BCE and, later, were used in a very advanced way by the Romans; these were primarily intended to act as storm drains taking surface water from urban areas and rural towns and villages to the nearest stream or river. However, human waste, animal waste (e.g. from horses used for transport) and waste products from industry were left in the streets to be ‘cleaned’ by storms, these drained with the surface water into the rivers. While the dreadful state of the rivers was widely recognised in the past, as it is again today, it took the arrival of Cholera Morbus in 1831 for action to be taken. (see page 37)

Liverpool City Council led the way with the installation of a sewerage system starting in 1848 and finishing in 1859, this doubled life expectancy. However, in other places the legislation, on its own, was not enough. In London, it took foul smells, popularly known at the time as “The Great Stink” from the Thames River flowing past the Houses of Parliament to persuade MPs to act.

The Great Stink of 1858

Hot weather and the use of thousands of water closets created an ungodly stench lasting two years, caused by the putrefaction of sewage caught in the tidal reach of the river. Sessions of Parliament (located at the riverside) were only made bearable by hanging sheets soaked with lime of chlorine from open widows.

Historical aspects of wastewater treatment.

Cooper (p19)