3 minute read

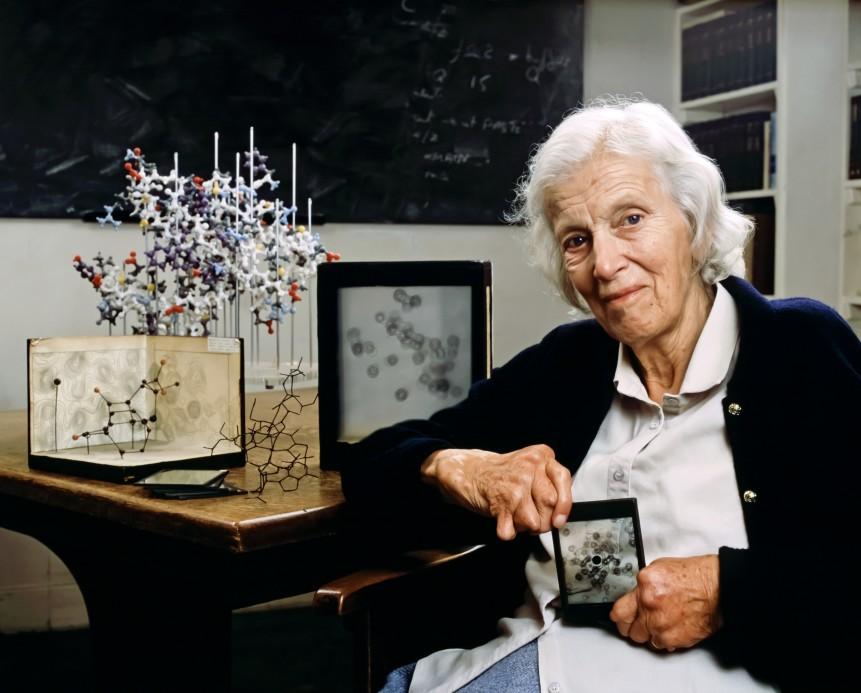

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin was born in Cairo on the Twelfth of May 1910 and died in Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire, England on July 29 1994 (aged 84). Cairo was where her father, John Winter Crowfoot, was working in the Egyptian Education Service however he moved soon afterwards to Sudan, where he later became both Director of Education and Antiquities. Dorothy visited Sudan as a girl in 1923 and acquired a strong affection for the country. After his retirement in 1926, her father gave most of his time to archaeology, working for some years as Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and carrying out excavations on Mount Ophel, at Jerash, Bosra and Samaria.

Her mother, Grace Mary Crowfoot (born Hood), was actively involved in all her father ’ s work and became an authority in her own right on early weaving techniques. Furthermore, in her spare time, she was a botanist who drew the illustrations of the official Flora of Sudan. Dorothy Crowfoot spent one season between school and university with her parents, excavating at Jerash and making mosaic pavements. She enjoyed the experience so seriously that she considered giving up chemistry for archaeology. She had three sisters: Joan Crowfoot Payne, Diana Crowfoot Rowley and Elisabeth Crowfoot.

Advertisement

She went to the Sir John Leman School, Beccles, from 1921-1928 and by the end of her school career, she had decided to study chemistry and possibly biochemistry. She went on to study at Oxford and Somerville College from 1928-1932.

She became interested in chemistry and in crystals at about the age of 10 and said that “[she] was captured for life by chemistry and by crystals,” and for a brief time during her first year, she combined archaeology and chemistry, analysing glass tesserae from Jerash with E.G.J. Hartley. After attending a course about crystallography, she decided to research X-ray crystallography, following compelling advice from her tutor, F.M. Brewer.

She spent most of her working life as Official Fellow and Tutor in Natural Science at Somerville, responsible mainly for teaching chemistry for the women ’ s colleges. She became a University lecturer and demonstrator in 1946, University Reader in X-ray Crystallography in 1956 and Wolfson Research Professor of the Royal Society in 1960.

During her PhD years, in 1934, Dorothy first visited a consultant about pain in her hands. He observed ‘ulna deviation – ’a hand deformity caused by swelling in the knuckle joints, and prescribed rest, which Dorothy put off finishing some experiments. In 1938, aged 28, with a blossoming research career, an infection triggered Rheumatoid arthritis. She described that she “found … [she] had great difficulty and pain in getting up and dressing. Every joint in [her]

body seemed to be affected.” After a few weeks ’treatments at a specialist clinic, Hodgkin returned to the lab. There she found her hands had been so affected that she could no longer use the main switch of the x-ray equipment required in her experiments. Undeterred, she had a long lever made and carried on with her research.

In 1941, Dorothy was aware of the urgent and secret wartime effort to refine the use of antibiotics by determining the structure of penicillin and wrote of being “irresistibly drawn to inject myself into the situation”; she proceeded to solve the structure in 1945 – coinciding with the end of the Second World War. The structure of vitamin B12 and organisational insights into various proteins followed. Of all the vitamins, vitamin B12 has the most complex (also the largest) chemical structure; this essential nutrient helps the body’ s nerve and blood cells remain healthy and helps to create the DNA in our cells. Then, in 1969, when Dorothy was in her late 50s, she finally got the measure of insulin.

For her work, she was awarded The Nobel Prize in Chemistry (1964), The Copley Medal (1976), The Royal Medal (1956) and The Lomonosov Gold Medal (1982). She is an inspirational figure because she persevered and didn’t let anything stand in the way of doing what she had always wanted to do. She followed her childhood dreams, overpowered her disability, and as a result, made many significant contributions to the field of science which have helped other scientists ever since.

By Maya 7G