WINTER Why W e love surf culture in h a W ai‘i THE SURF ISSUE DISPLAY UNTIL FEB. 1, 2013

32 N Hotel St. MON 8AM-10PM TUES-FRI 8AM-2AM SAT 10AM-2AM

www.manifesthawaii.com

Twitter: @THEMANIFEST

Free Wi-Fi

ONE OF THESE CUPS IS NOT LIKE THE OTHER

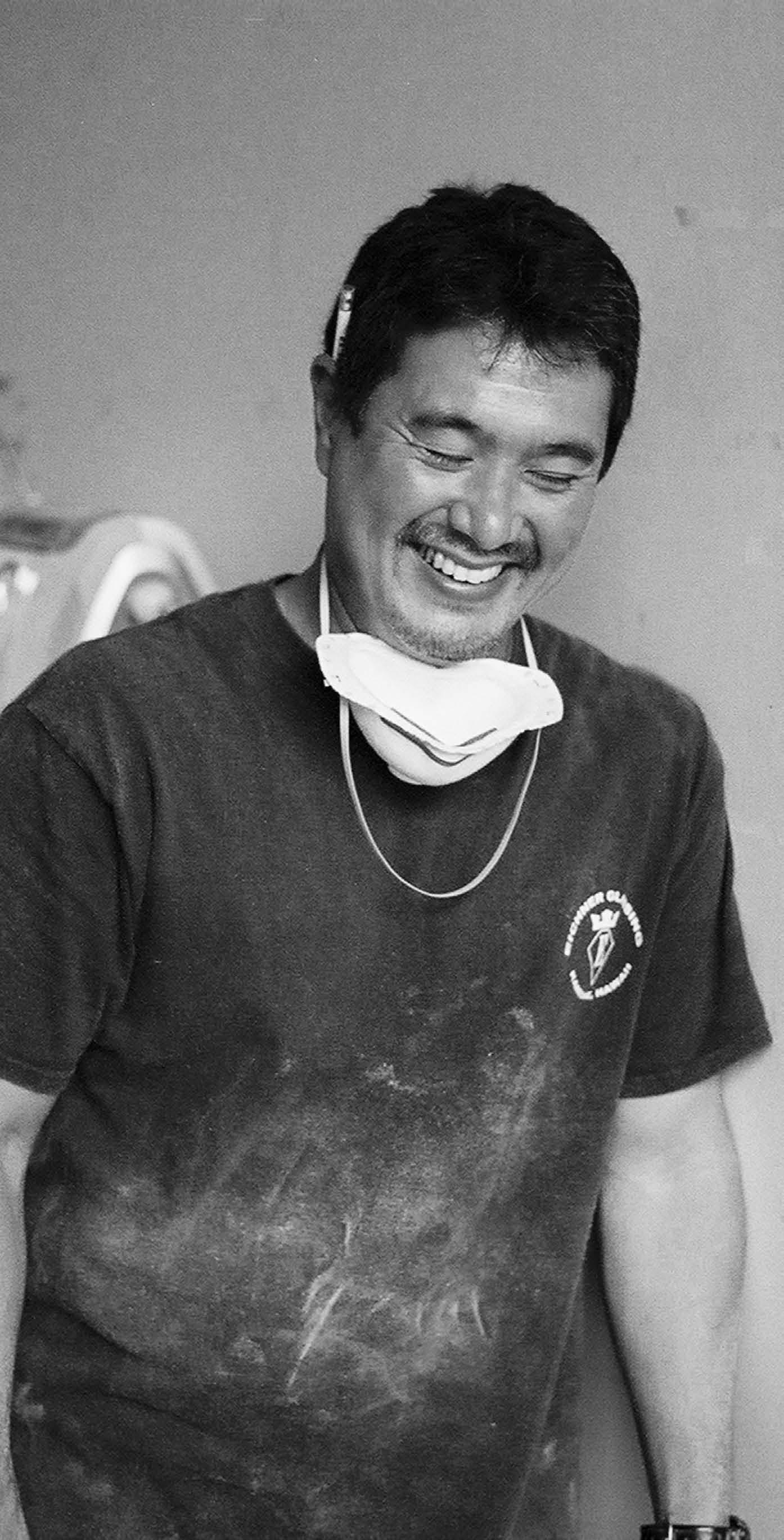

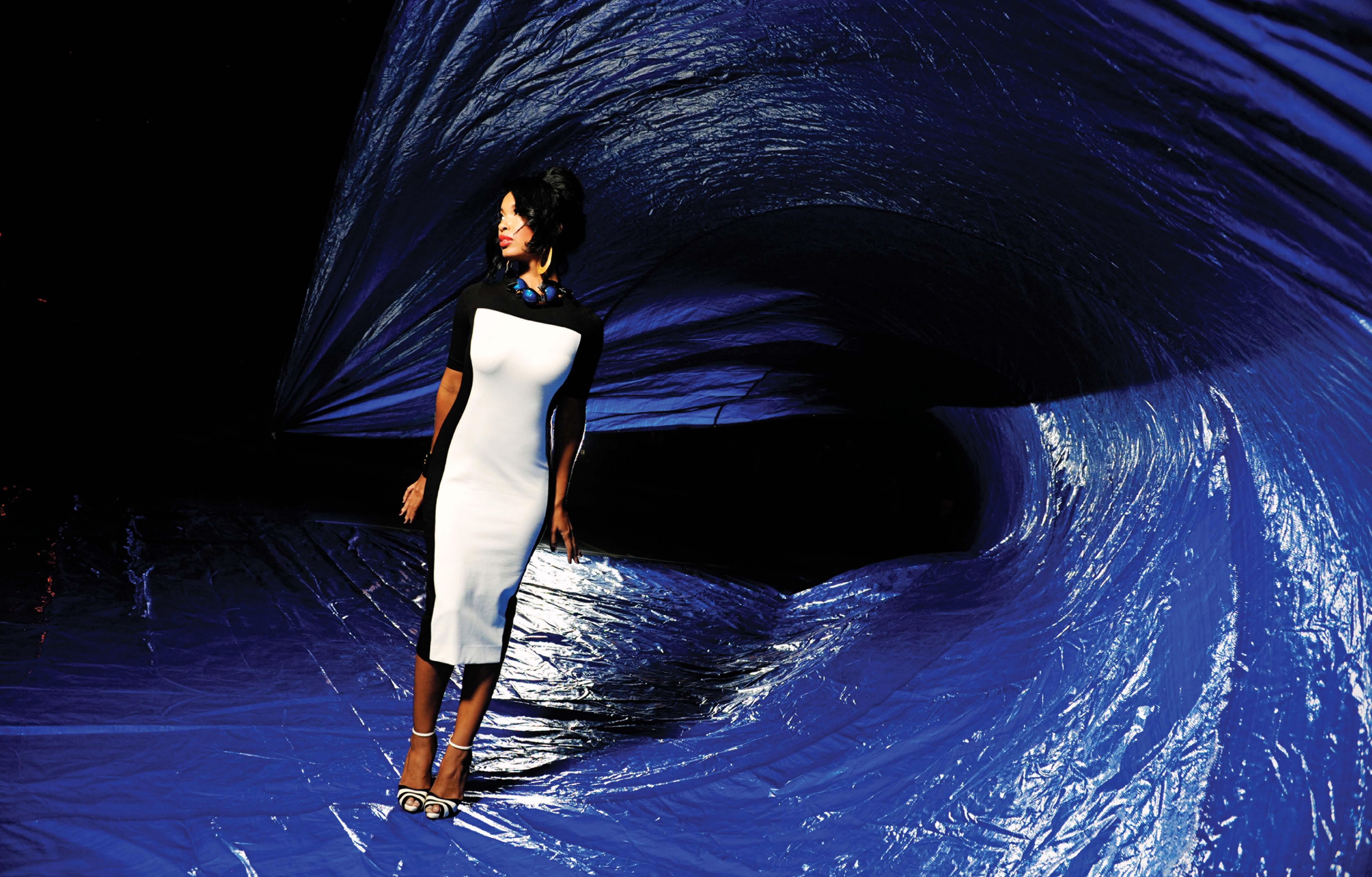

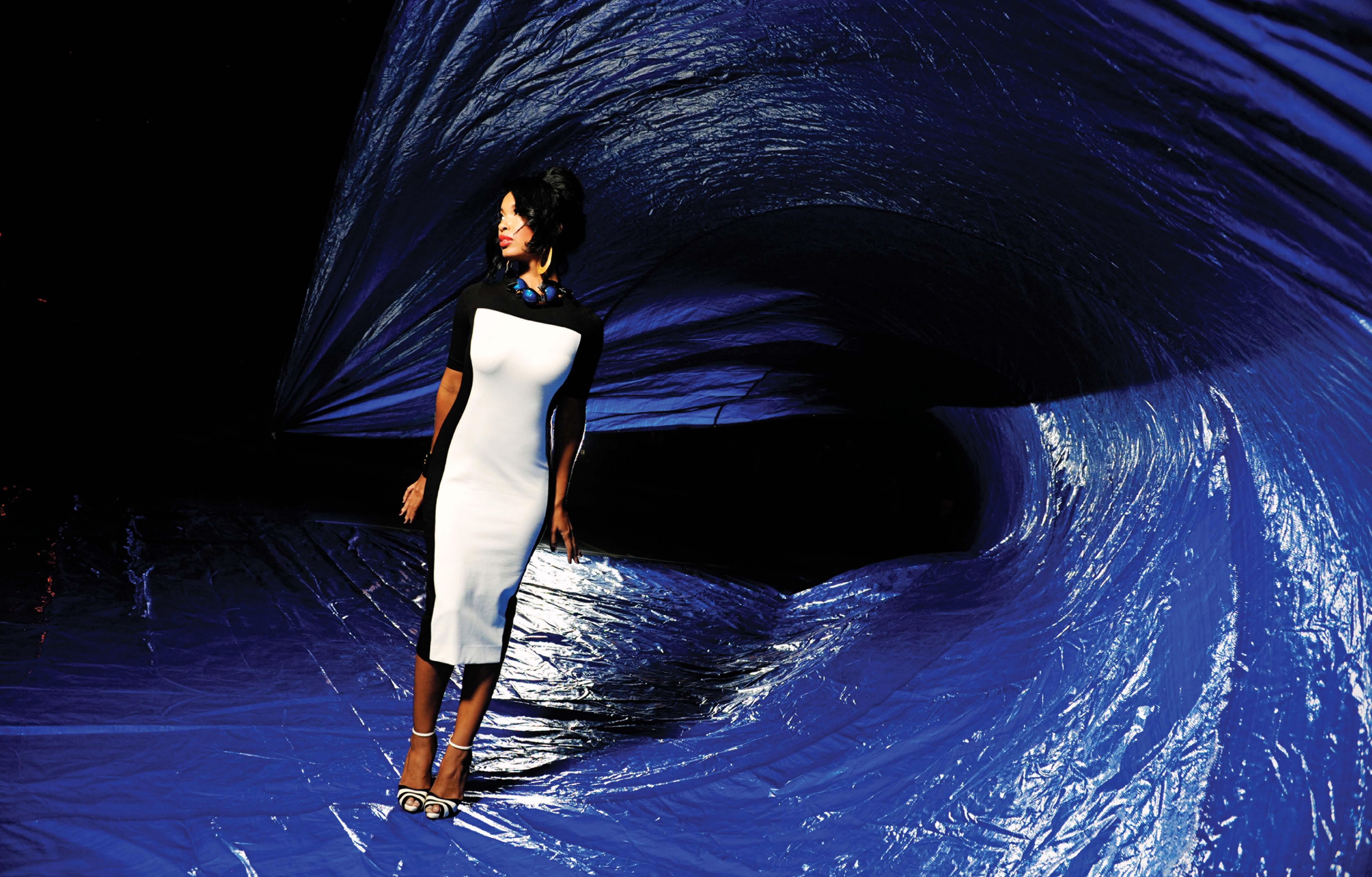

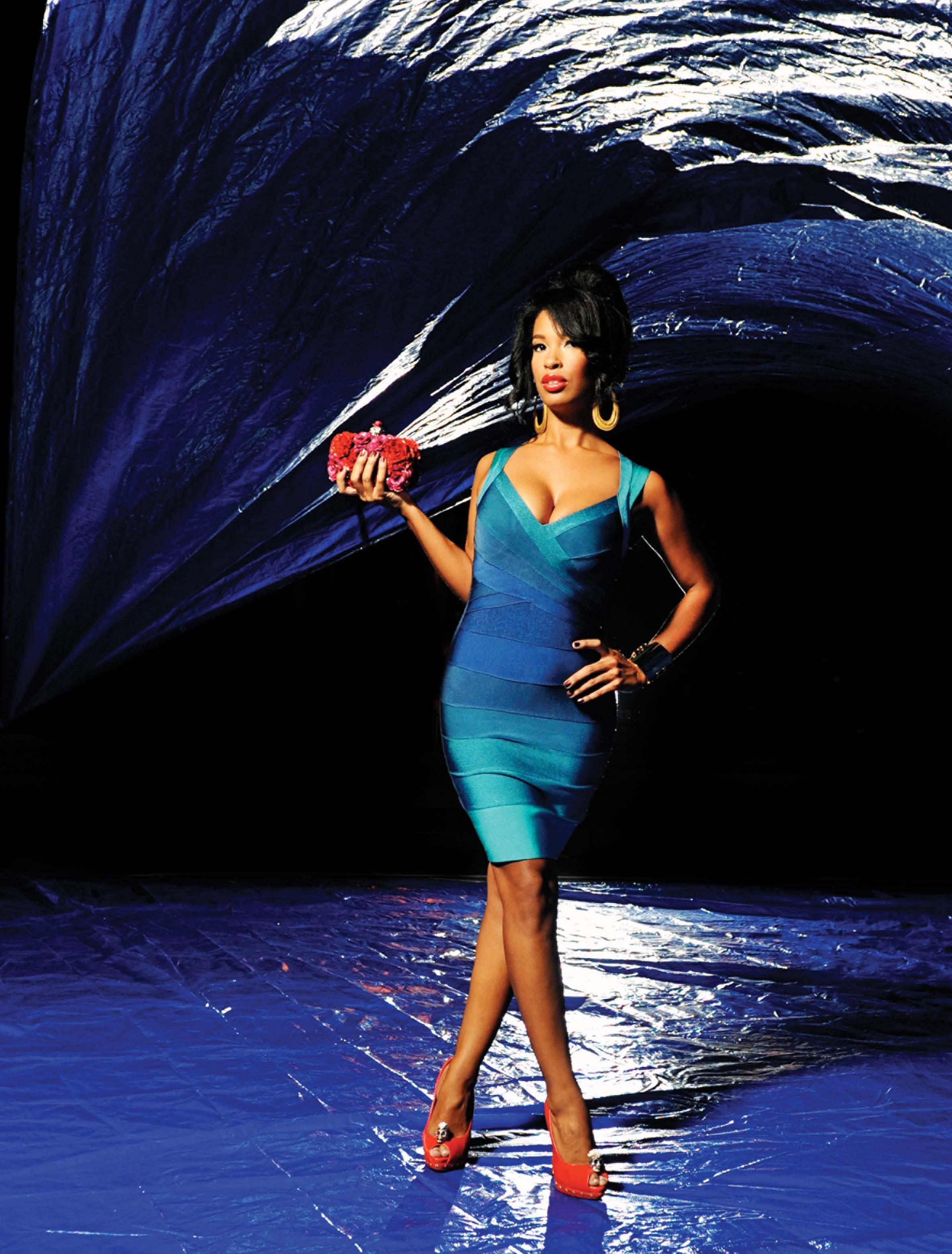

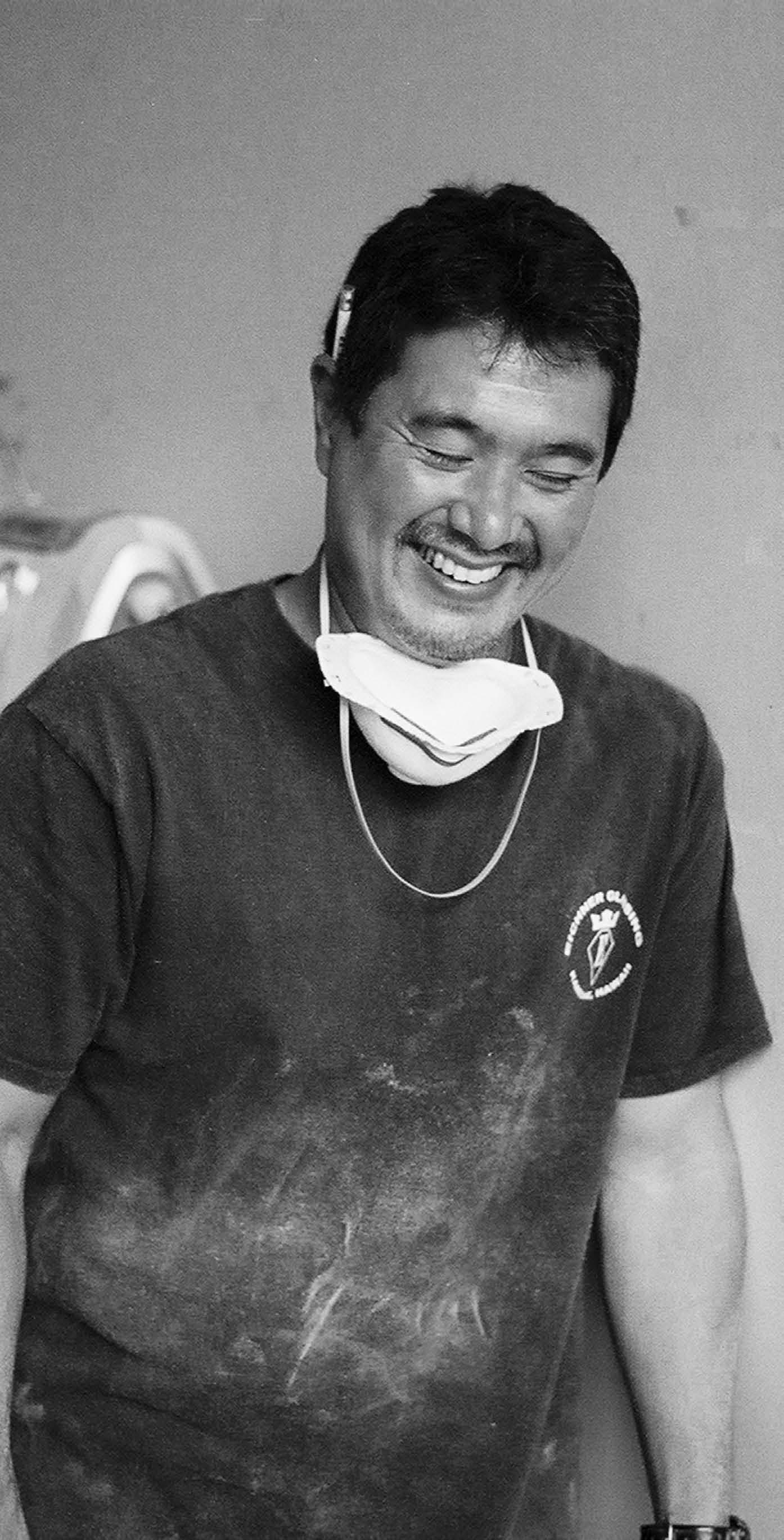

Wade Tokoro remains a fixture in the changing industry of surfboard shaping. Why We Love Surf Cu Lture in h a W ai‘i Inc I dents of a s hap I ng Voyage: CJ Kanuha | 30 s l Iced d own to sI ze: Wade To Koro | 34 t he g reat e qual I zer: In T he l I neup on o‘ahu’s s ou T h s hore | 36 paddl I ng In | 40 wa I k I ī k ī Beach Boys | 44 a lex f lorence: her Three sons and The sea | 46 Mon I z I s the n a M e | 48 l egends BuTTons KaluhIoKalanI, larry BerTlemann and JoCK suTherland | 50 stay I n s chool | 56 fash Ion: In The Blue | 60 PAGE 34 TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES 4 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY AJ FEDUCIA

Nat and Shaun Woolley’s screenprinting and art space in the historic North Shore building that was once the infamous dive bar The Sugar Shack.

edI tor ’s letter guest edI tors contr IB utors M asthead letters to the edI tor what the flux ?! | 20

A Br UTAL FALL

FLUXFILES : art | 22

Th E Woo LLEY BroT h E r S

FLUXFILES : art | 24

Z A k NoYLE

I n flux | 68

STA r TIN g PoINT: oN W IND FA rm S

I n flux | 70

oN Tr END : Pr INTS

I n flux | 74

Ar T oPENIN g S

VI ewf I nder | 80

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS 6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY J OHN H OO k

PAGE 22

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

Bruschetta of eggplant confit, herb goat cheese & basil aioli

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

Bruschetta of eggplant confit, herb goat cheese & basil aioli

Stay Handsome

Shown here: The Navigation printed shirt from Roberta Oaks, 19 N. Pauahi St. You can find more fun men’s prints like these online at robertaoaks.com.

Find more of A+A’s trending looks - printsonline, and get tips from the duo about what to look for when mixing prints.

B eh I nd T he s C enes WIT h J ohn hoo K

Go behind the scenes with photographer John Hook to see what comprises his life as a magazine photographer. Get insider looks on what it takes to make fashion editorials come to life, or what inspires him and goes on inside that kooky, genius brain of his.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | ONLINE 8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

FULL STORY ONLINE

Perfect for special and private events Birthday, Anniversary, Business,Wedding and Holiday Parties Offering Several Event Packages Standing Cocktail Receptions and Sit Down Dinners for Groups from 15 and up No Rental Fee For Information Contact events@brasserieduvin.com Brasserie Du Vin 1115 Bethel Street www.brasserieduvin.com Monday - Saturday 11:30 am - Late g g g g HOLIDAY SUBSCRIPTION SPECIAL: $10 for an annual subscription to FLUX (4 issues) That’s more than 60% off the cover price! GO TO: FLUXHAWAII.COM/SUBSCRIBE ENTER PROMO CODE: “HOLIDAY12” LIGHT SOMEONE’S FIRE THIS HOLIDAY SEASON… WITH AN ANNUAL SUBSCRIPTION TO FLUX HAWAII, YOUR SOURCE FOR ARTS AND CULTURE IN HAWAI‘I.

Up until I started this magazine, surfing has followed me all my life. Growing up, I would never have imagined my evening sundowns and dawn patrol mornings would be replaced by late afternoon meetings or early morning deadlines. Not that surfing ever claimed the space then either; I was never any good, really, but the ocean has its hold on all of us.

When I was in elementary school, I remember my dad pushing me on a bodyboard just inside of Straight Outs at Kewalo’s. I remember stepping on vanna for the first time paddling out to Bowls while trying to impress some intermediate-school boys (I also remember the excruciating four hours that followed with a plastic surgeon digging at the spines protruding from both heels and all 10 toes).

In high school, I remember feeling quite good about myself for handling a four-foot day at Rocky Point and watching the sun going down on a perfect session at Tracks. Surfing in college is something I’d be happy to forget: frigid California surf, scratchy seaweed filling murky water, being swept underneath the Huntington Beach pier and subsequently rushed to the ER after being skegged in the hindquarters. And upon returning from college, I remember having one of the best sessions ever with my uncles and cousins on a two-foot-nothing day at Second Holes.

I remember going out to Concessions by myself one time. It was just a foot high and onshore, but I had the whole spot to myself, rare even on days as bad as this one. What was most impressive that day was particularly how unimpressive it was. I’d been out on days where the conditions were as bad as this, but never completely alone,

out there in the choppy, gray sea. Looking back on growing up in the surf, and in putting together this issue, I realize that perhaps the greatest thing about surfing is that it connects us to each other, to friends, family, and often to complete strangers, which explains why, for me anyway, that one lonely surf session out at Concessions seemed so much less significant than that two-foot-nothing day with family at Second Holes. Surfing has this funny way of pulling groups of people together, when for a glorious few moments, nothing else matters. And it’s those interactions, good or bad, that make it unlike anything else in the world.

I am honored that it was surfing yet again that pulled together two of the industry’s best, Jun Jo and Jeff Mull, to collaborate as guest editors for this issue. Jun is a co-founder of In4mation, a lifestyle, action-sports retail brand, and a pro surfer that arose out of the famed Momentum Generation. Jeff, who grew up surfing on Kaua‘i and admittedly spent hours trying to learn how to cutback like Jun after watching his part in Taylor Steele’s Momentum, is the Hawai‘i editor of Surfer magazine, often considered the bible of the sport.

I don’t know if we’re in the best of times the sport has seen, as Jeff says on page 12, or in the worst, as Jun argues on page 14. All I know is that surfing will still be around should I ever choose one of these days to follow it back.

Enjoy.

Lisa Yamada Editor

| EDITOR'S LETTER

IT WAS ThE BEST oF TImES...

Guest editor Jeff Mull breaks down why there’s no better time than now to be a surfer.

If you’re the CEO of a major surf brand, it could be easily argued that these aren’t exactly the rosiest of times. But for the rest of us – the 99 percent if you will – there’s never been a better a time to be a surfer. Now, the critics among you will point to congested lineups, to the rise of the stand-up paddle boarders, perhaps, and there will invariably be those among you that decry that we’ve sold out, that surfing has become no better than … err … skiing. That somewhere along the way, surfing lost its soul.

But that’s not really the case. Now, right now, this very minute is the absolute best time in the history of the sport to call yourself a surfer. For those of you rolling your eyes, ask yourself this question: If you wanted to know exactly where the best place to surf is today, how long would it take you to figure that out? With the rise of Surfline and other livestreaming cameras, the power to sniff out the best waves on the island is literally at your fingertips. Gone are the days of driving around endlessly, checking dozens of lineups, losing hours of surf time on the road when you could be in the water. Think Rockies could be firing? Check the cam. Wonder if Kaikos is breaking now? Check the cam. Is Bowls crowded –OK, we don’t need a cam to know the answer to that one. Our forefathers would have flipped if they could literally check the surf from the comforts of their own homes. With the rise of the Internet, your probability of scoring just increased by 80 percent.

Still not convinced? Let’s take a closer look at technology. With the help of CAD machines, shapers are able to pinpoint specific dimensions down to the millimeter, essentially churning out hundreds of magic boards in the process. Lemons are now the exception to the rule. And for those of you who travel to the mainland and are forced to wear a wetsuit, you’re literally wrapping yourself in progress every time you surf. Just a few decades ago, wetsuits were so primitive and uncomfortable that you were either rendered hypothermic or were bleeding from chaffing by the time you came in. Today, thanks to rubber so soft, seamless and effective, surfers are uncovering gems of point breaks in places once deemed too frigid to pioneer. There are literally hundreds of lineups that have opened up because we’re now able to comfortably combat the elements.

For those of you who bemoan the crowded lineups of today, think about how you’d feel should you have been the last person to learn to surf. Think of all the times you’ve come in from a session, grinning from ear to ear, beaming happiness. Would you really want to deprive other people of that feeling? Yes, having to battle for waves can be less than civil at times, but that’s a reality of being a surfer today. Far be it from me, or anyone, to tell someone that by simply being in the lineup, they are ruining your session. You’re better than that. As a whole, we’re better than that. And if you agree with me, it turns out surfing still has plenty of soul left.

Now go surf.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Guest editor Jeff Mull is the Hawai‘i editor of Surfer magazine.

IT WAS ThE

WorST oF TImES...

Guest editor Jun Jo laments why today is the worst time to be a surfer.

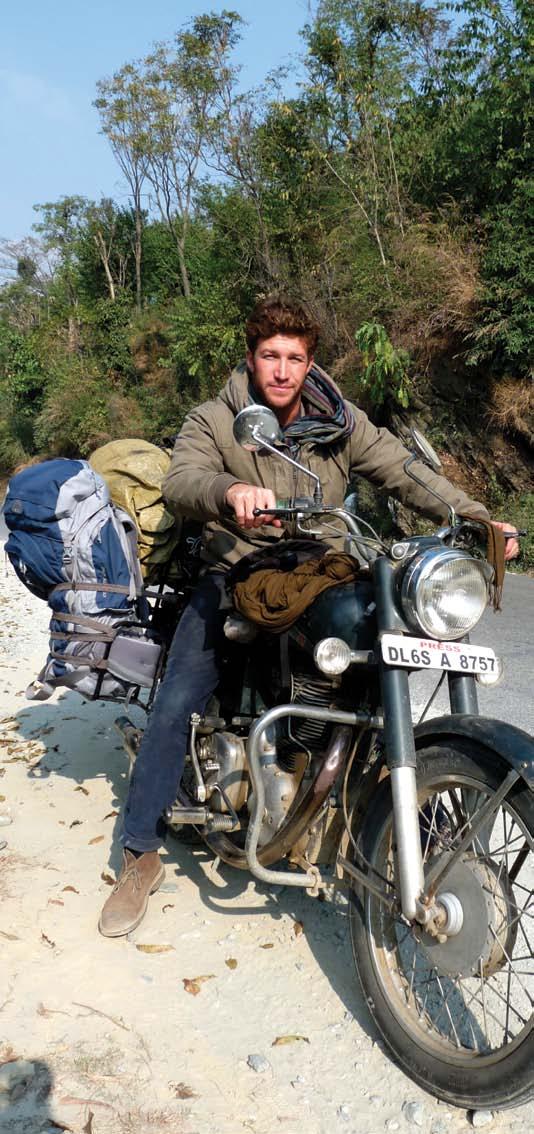

IMAGE BY k ENYU, IN A k ITA PREFECTURE, JAPAN

When I first started surfing, I was lucky to be part of a group that was pushing the sport to a whole other level, a movement called the Momentum Group. I just rode on the coattails of my friends, really – Kelly Slater, Rob Machado, Shane Dorian, Ross Williams, Conan Hayes, Taylor Knox – but we were part of a boom in surfing, an era that gave rise to big contracts and big money.

So it seems hypocritical to say now that we are in one of the worst times the sport has ever seen. But when I was a kid, you surfed because you liked what it represented; you were an individual, were anti-establishment. Today, it’s flipped. Surfing is in a fragile state in which the people that run surfing are all part of big, publicly traded companies. Private investment firms are investing in surf companies, and now you have people that are more corporate than the corporates in place. Billabong, which owns about a dozen other surf companies, is in financial disarray (see page 21 for how the industry giant got there); Volcom was recently bought out by French luxury and retail group PPR. What you end up with are people running the surf industry who have no idea of what’s happening on the ground. How can that be a good thing?

Surfing has reached the state of being a major sport, comparable to professional baseball, basketball, football, soccer, even tennis. It’s good in that you actually have a chance at making a living, supporting a family, buying a house. But in the same sense, you have kids dropping out of school to try to go pro as soon as they get a taste of young fame. Everyone seems to think that the pattern to elevate your surfing is to drop out of school or to be homeschooled. But more often than not, that kid is not going to make it.

These up-and-coming young surfers are being treated like they’re nothing more than a commodity. As soon as their time is up, when there’s no more potential for selling shirts or hats or stickers, they’re dropped just as quickly as they were picked up. What you end up with are kids with no education and diminished social skills.

But it’s not all bad. Because you also have guys like Zeke Lau, who stayed in school and led his surf team at Kamehameha to three consecutive state championships. He’s winning everything in sight and is probably one of the best Hawaiian surfers out there.

Ultimately, parents need to be careful to make sure their kids still enjoy being out in the water, because if they don’t, they’ll probably suck at it too. The best surfers in the world are the ones who have fun, and still are.

So what are you waiting for? Have fun, go surf.

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Guest editor Jun Jo is a co-founder of In4mation and a pro-surfer who came out of the Momentum Generation.

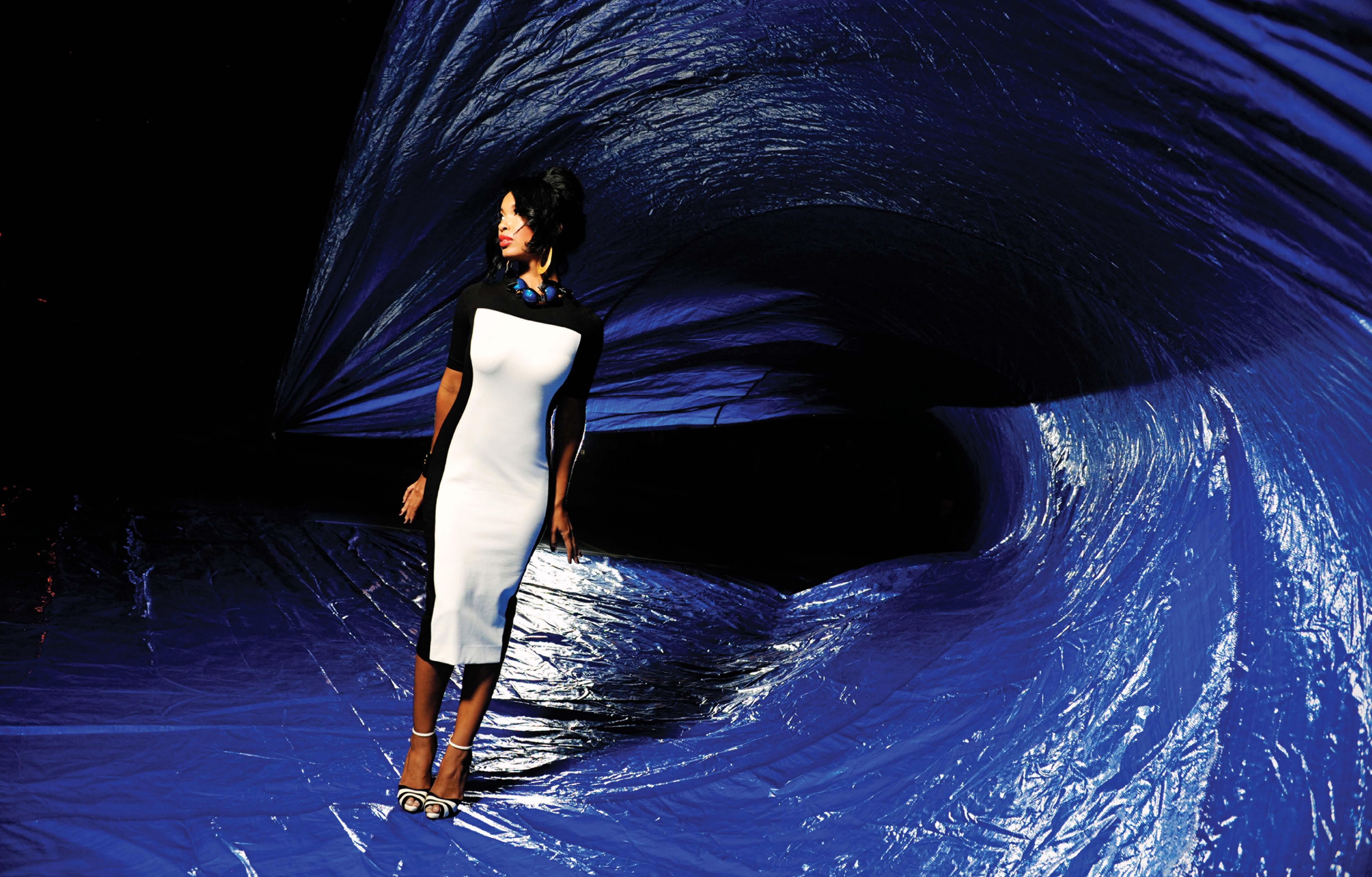

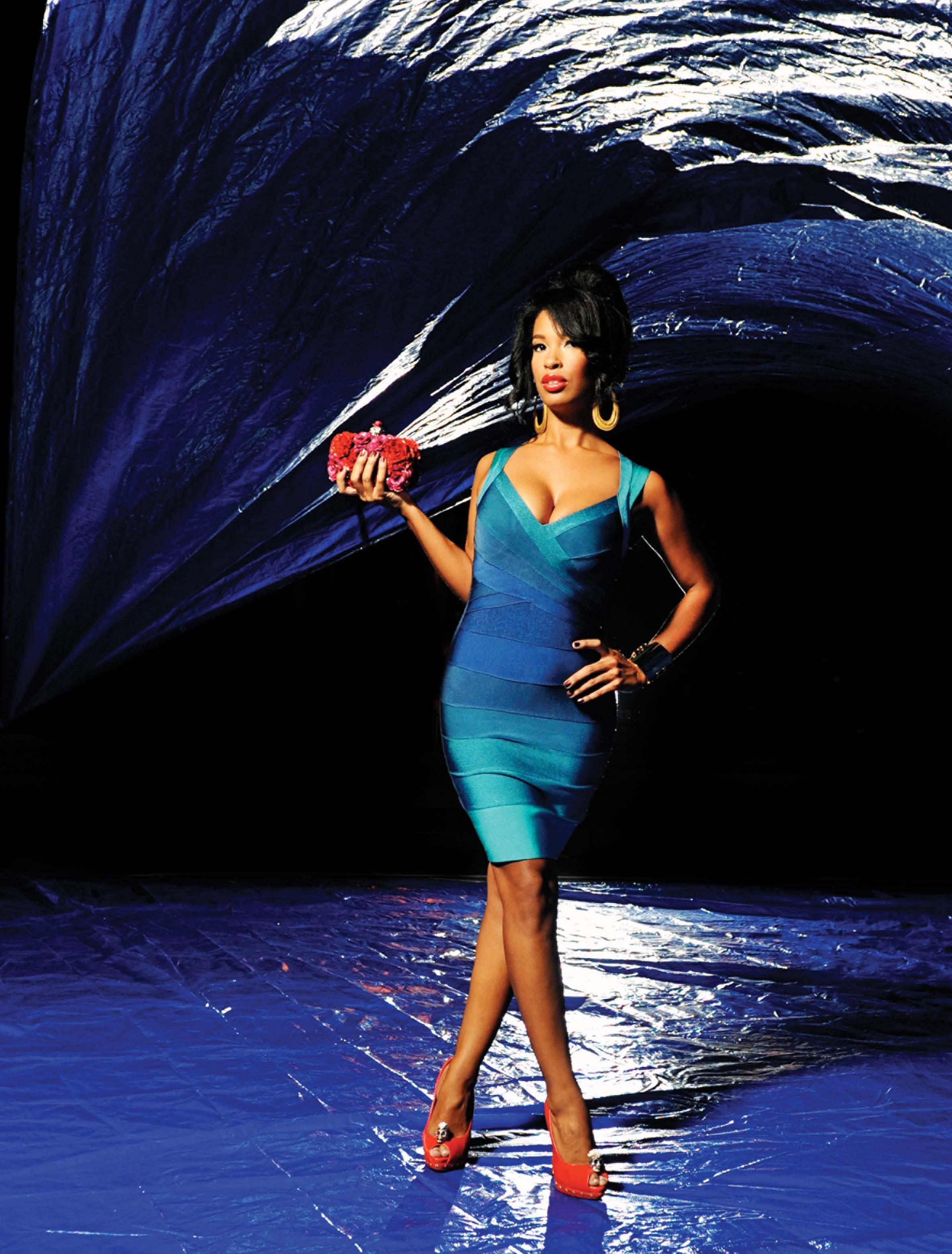

A+A

A LY I S h I k UNI AND Ar A L AYL o m A k E UP T h E STYLIST DU o A+A.

Though they have a wide set of interests, their unique perspective on fashion brings them together. Ishikuni is the co-founder of Art & Flea, which was voted “Honolulu’s Best Monthly Event” in 2011 by Honolulu Magazine and features vintage wares and handmade goods from more than 50 local vendors.

With more than a decade of experience in the design industry, Laylo brings a deft style to Nella Media Group as its creative director. Between deadlines, she serves as a lecturer at University of Hawai‘i and fronts the ambient three-piece band Clones of the Queen.

JohN hook

J oh N hook , W ho DESC r IBES h I m SELF AS A “P ro FESSI o NAL FUNT ogr AP h E r ,” h AS BEEN m A k IN g WAVES IN T h E P ho T ogr AP h IC C omm UNITY.

When he’s not capturing photo gold for FLUX, Hook captures magical moments with L’amour Photography and Dave Miyamoto & Company. This fall, he, his family and several friends who are part of the Analog Sunshine Recorders will travel 3,000 miles down the Pacific Coast Highway snapping film photos along the way to create Wake Up, We’re Here , a book of images that’s inspired by travel and the idea that we’re really all just visitors of one place or another.

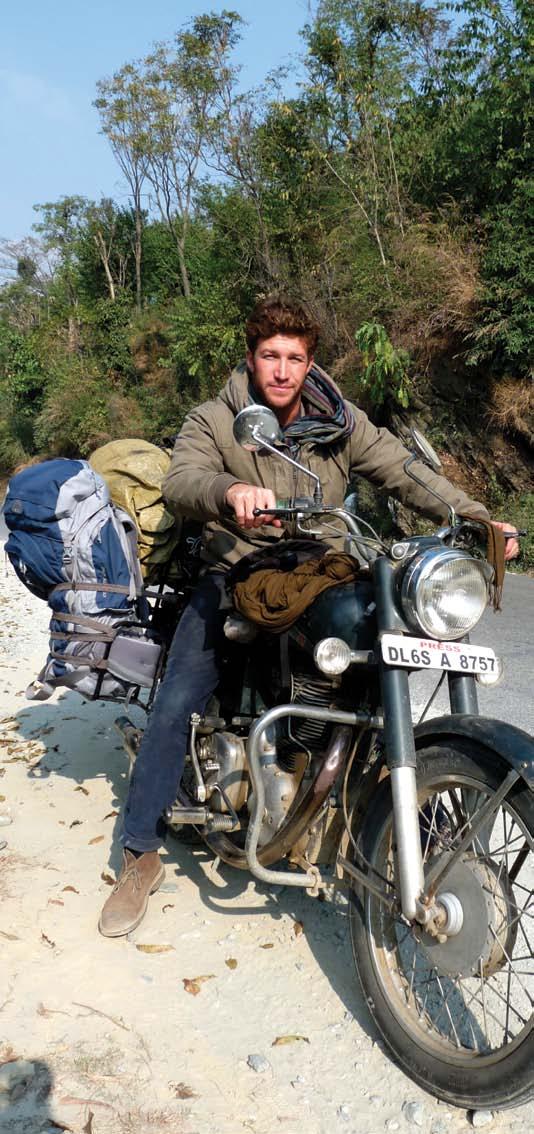

BEAU FLEmISTEr

B EAU F LE m ISTE r IS A W r ITE r F rom kAILUA , hAWAI ‘ I

Based in San Clemente, California, he is the managing editor of Surfing Magazine. He has had works published in various magazines across the globe and has traveled to more than 50 countries. He is finishing his first novel entitled, In the Seat of a Stranger’s Ca r.

ZAk NoYLE

Z A k No YLE IS AN o UTD oor P ho T ogr AP h E r WIT h A T r ULY UNI q UE PE r SPECTIVE o N SU r F AND SEA , C r EATIN g D r A m ATIC I m A g E r Y AND A r TFUL INTE r P r ETATI o NS o F T h E W or LD ’ S mo ST m A g NIFICENT o CEAN ENVI ro N m ENTS

Noyle is a senior staff photographer at Surfer magazine, and his clients include Red Bull, Hurley, Quiksilver, DC Shoes and Chanel. His images have been published in National Geographic, London Times and ESPN. Read our full profile on Noyle on page 24.

CONTRIBUTORS | 16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

FLUX hAWAII

Jason Cutinella PUBLIShEr

Lisa Yamada EDITor

Ara Laylo CrEATIVE DIrECTor

SENIor CoNTrIBUTINg

PhoTogrAPhEr

John hook

gUEST EDITorS

Jun Jo

Jeff mull

ImAgES

AJ Feducia

Lost and Found

Tammy moniz

Zak Noyle

Daniel russo

Aaron Van Bokhoven

CoNTrIBUTorS

ragnar Carlson

Beau Flemister

Sonny ganaden

Anna harmon

CoPY EDITorS

Anna harmon

Andrew Scott

AD DESIgNEr

Joel gaspar

CoVEr PhoTo

John hook

INTErNS

richelle Parker

matt gonzalez

Published by: Nella media group

36 N. hotel Street, Suite A honolulu, hI 96817

CrEATIVE

ryan Jacobie Salon

Timeless Classic Beauty

STYLIST A+A

mULTImEDIA

Director of Digital marketing

michael Pooley

WEB DEVELoPEr

matthew mcVickar

ADVErTISINg

Scott hager Director of marketing & Advertising scott@ FLUXhawaii.com

oPErATIoNS

Joe V. Bock

Chief operating officer joe@ nellamediagroup.com

gary Payne

Business Development Director gpayne@ nellamediagroup.com

Jill miyashiro National Account manager jmiyashiro@ nellamediagroup.com

general Inquiries: contact@ FLUXhawaii.com

2009-2012 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii. com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

MASTHEAD |

I am a super senior, who enjoys reading FLUX. However, I find the reading difficult to do at night or in poor light because the print is too small and very light. With a little correction, I think more people will enjoy the magazine. Thanks.

Ellie Yamaguchi Sent via email

Previously, our font has been Garamond point 9.35. Per your request, we have reformatted our font size to Garamond point 9.75.

Your nostalgia issue was perfect! It brought back so many good memories. Of camping, collecting sand crabs in buckets and Portuguese man o’ war in Styrofoam cups, of late-night fishing and roasting marshmallows over open fires – I even look back on the cold showers with fondness! I was happy to see kids are still getting out there and playing with yo-yos and flying kites, although I was sad to see that pogs weren’t included. If you ever need to do a story on pog collectors, I’m your guy.

Sincerely,

David Lee Honolulu

W E WE lcom E a N d valu E you R f EE dback. S EN d l ETTERS TO T h E E d ITOR v I a E ma I l TO l IS a@fluxhawa II CO m OR ma I l

TO flux h awa II , P.O. B Ox 30927, hONO lulu, h I 96820.

CORRECTIONS

In our fall Nostalgia issue, in “Mu‘umu‘u Days” by Paula Rath, we erroneously stated that her godmother Marion Murphy was of Murphy’s Bar and Grill fame. She was, in fact, the wife of John F. Murphy, who served as the vice president of Castle & Cooke and president of the Honolulu Symphony.

In that same issue, we incorrectly attributed John Hook as responsible for the images included in “#hiNostalgia: The Sweet Lie.” The images that were included were from an Instagram photo contest, in which Elisa Chang (@ swaggerlee) was named the winner. Photos from the following were also reprinted:

Via instagram: @a_nnnn_a @danicason @hilarizzle @icoopuh @itramonti @kahuku @karens_daughter @patricknevada @seanwconnelly @unrlhi @yukko_pen

Via email: Brent Akana Norman Ko

| LETTERS TO THE EDITOR FOLLOW FLUX ON TWITTER @FLUXHAWAII.

BAR 35 35 N. Hotel Street www.bar35.com Monday - Saturday 4:00pm to 2:00am 200 BEERS FROM AROUND THE WORLD PREMIUM COCKTAILS AND SPIRITS HANDMADE GOURMET PIZZA AND EUROFRIES DJS, LIVE MUSIC AND ENTERTAINMENT DAILY HAPPY HOUR 4:00 TO 8:00PM FOR PRIVATE EVENTS, RESERVATIONS AND BOTTLE SERVICE, INFO@BAR35.COM

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

A BRUTAL FALL

TEXT BY JEFF MULL

In the fall of 2012, the surf industry took a plunge, with some the industry’s biggest name brands in financial and organizational disarray. Here, we outline how two brands – Quiksilver and Billabong – got to where they are today.

qu I cks I lV er

1970

t he first pair of q uiksilver boardshorts are manufactured and sold in australia.

s urfers Jeff h akman and Bob Mc knight are granted the license to the company and begin selling boardshorts out of the back of a V w bus in c alifornia.

q uiksilver becomes a publicly traded company.

tom c arrol signs surfing’s first ever million-dollar contract with q uiksilver.

2007 1976 2008 1986 2009 1988 2005

q uiksilver purchases rossignol for $320 million.

t he g reat recession officially begins in d ecember.

q uiksilver sells rossignol for $147 million.

a s a result of the financial crisis, q uiksilver enters into an agreement with r hone, an international private equity firm, for a five-year deal that loans the company $150 million. additionally, q uiksilver enters a written commitment with Bank of a merica and ge c apital to refinance its existing a mericas facility in the form of a new threeyear $200 million asset-based credit facility.

2012

s & p lowers q uiksilver’s corporate credit rating to ‘B-’ from ‘B’ with a rating outlook of negative. according to reuters, “ t he outlook is negative, reflecting our view that weaker operating performance could continue over the next year, and our view that the company has less than adequate liquidity.”

IN OTHER NEWS THIS YEAR …

RIP CURL RECEIVES UNSOLICITED APPROACHES FROM SEVERAL INTERNATIONAL COMPANIES, EXPLORING A SALE FOR AS MUCH AS $500 MILLION. 1973

Billabong is founded in australia.

The Association of Surfing Professionals, surfing’s governing body, signs a termlease deal with newly formed ZoSea m edia, effectively privatizing the ASP.

BI lla B ong

acquires swell.

acquires r Vca and west 49.

reports sales of $1.7 billion

t he company begins being publicly traded on the australian s ecurities e xchange.

Billabong experiences a collapse in earnings.

acquires Von zipper. acquires e lement.

acquires kustom footwear and p almers s urf.

acquires n ixon.

2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 2008

acquires xcel wetsuits and tigerlily. acquires q uiet f light, d a kine and s ector 9.

Billabong announces sale of 48.5 percent of n ixon.

tpg, an american private-equity firm, offers to purchase Billabong at $3.30/share. Billabong rejects offer.

tpg makes another offer for the company, valued at $1.45/share.

Bain capital, a private equity firm founded by Mitt romney, reportedly makes a competing bid for Billabong, but subsequently walks away.

2009 2010 2011 2011-2012 2012 Jul 24 2012 feB 2012 sep 20 2012 oct 12 2012

tpg pulls out of reported takeover deal.

tpg pulls out of reported takeover deal.

Shaun and Nat Woolley cut their teeth surfing some of the world’s most famed lineups and are now transforming the sleepy Waialua town where their shop is located.

ROOm TO GROw

The Woolley Brothers

On a late September morning, in the sleepy town of Waialua on O‘ahu’s North Shore, Shaun and Nat Woolley are hard at work filling a last-minute order. In their office, the pair stands vigil over a massive screen-printing machine carefully churning out batch after batch of custom-designed tees. Their building, which was once a turn-of-the-century bank and then an iconic roadhouse bar, drips with history.

As lifelong surfers, they ask if I know whether or not a projected swell has begun to fill in, and I’m left with the feeling that they’re secretly yearning to postpone the interview and finish the rest of the order later. But I’m wrong. Instead, they invite me inside and we get to talking about how a pair of twin brothers have come to be so respected by their peers, helping reinvigorate a small town with a deep history, while still finding time to squeeze in a daily surf session.

As twins, both Shaun and Nat have always been close. Growing up on the North Shore, they cut their teeth surfing some of the world’s most famed lineups and were surrounded by a wealth of the world’s best surfers. Their youth was marked by days on end in the water, but when it came time to step into adulthood, the way they approached their respective career paths set them apart. Both held a keen interest in shaping surfboards and art and yearned to turn their passions into careers. Nat found work cutting boards for famed shaper Eric

Arakawa. Shaun hunted for a space to house his budding screen-printing business. But no matter what endeavor the other undertook, they were there to help each other.

In 2007, their separation ended when the brothers set up shop in the aforementioned building in Waialua. When the duo learned the dilapidated old structure was available, they quickly jumped at the opportunity –and it just as quickly consumed them, giving the brothers careers and sparking new life in the neighborhood. In this space, not far from where he shaped boards for Arakawa, Nat was able to focus on his art, which had gained a solid following over the past few years, and Shaun grew his screen-printing business.

“Growing up, we were around this place all the time. When we were groms, it was called the Sugar Bar. I’d guarantee you that some super heavy stuff went down right here. Right where we’re sitting right now. It changed hands a bunch of times and whenever someone left, they gutted it pretty hard. It was basically a place for homeless people to post up for a while,” says Nat. “When we took it over, man, it needed some work.”

From the outset, the brothers had a goal to transform this Waialua landmark. “We wanted this place to be something positive for the neighborhood. When the mill closed down, this place had become a little seedy with some drugs and homelessness. We wanted to turn that tide. We wanted to

be one little blade of green grass in a mud patch, and then hopefully another one would pop up. All we had going for us was psych. We didn’t have a lot of money, just a lot of passion. So we started to build it up from there and everything sort of worked out and has started to grow,” says Shaun. “I think that’s true of life. When you’re following something you’re really passionate about, good things seem to happen.”

Good things have been happening both for the Woolley Brothers and Waialua. Now flooded with both orders for boards and screen-printed tees, you’ll find that if the two brothers had a gripe (and trust me, they don’t) it would be that they’re not able to surf as much as they would like. “We still get in the water every day, but we’re not able to just drop it all and go surf when it’s good,” they say with a laugh. “Well, most of the time we won’t drop it all to go surf. But since we’ve opened up our shop, everything has gone really well. Not only for our business, but for the community as well. There’s a farmers market now, new restaurants … all sorts of rad stuff. We’ve come a long way, but there’s still plenty of room to grow.”

For more information, go to woolleybrothershawaii.com.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23 TEXT BY JEFF MULL FLUXFILES | ART IMAGES BY JOHN HOO k

ThROuGh ThE lOOKING GlaSS

Surf Photographer Zak Noyle

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | P ORTRAIT IMAGE BY J OHN H OO k

A conversation with surf photographer Zak Noyle usually goes something like this:

q UESTIo N : “HEY ZAK, YOU ABLE TO MEET UP ON [INSERT DAY]?”

ANSWE r : “HEY, I’M ACTUALLY IN [INSERT LOCALE] FOR THIS SWELL. CAN WE RESCHEDULE?”

Messages like these are common for Noyle, who has to be ready to pick up and go at the drop of a dime depending on when and where the surf’s good. “I’ve had to reschedule my dentist appointment six times this summer,” says Noyle. “They’ll call to remind me about my appointment, and I’ll be like, ‘Well, I’m in Tahiti right now. Can we reschedule for Monday?’ But still, there’s no guarantees … you have to be ready to go, passport out, bags packed.”

Despite coming from a family of photographers (his father is a well-known commercial photographer and his grandfather shot aerial photography during WWII), Noyle says he only seriously began delving into photography six years ago. In just a few years, he quickly established himself as the world’s premiere surf photographer. Whether you surf or not, looking at one of his shots quickly propels you into his watery world; deep walls of glass barreling clear overhead pull you in, while expansive landscapes punctuated by aerial maneuvers make you sit back in awe.

At just 27 years old, Noyle has a resume that reads like a seasoned pro: senior staff photographer at Surfer magazine; international ad campaign for Chanel’s Homme Sport fragrance; the Quiksilver in Memory of Eddie Aikau in 2009, which he describes as one of his most memorable moments to date. Though he wasn’t the first pick for the job, he was the only photographer willing to shoot in the water – the only one willing to come face to face with Waimea Bay’s gigantic 20-foot-plus waves.

“I had to ask myself, ‘Could I even dive a 30-foot wave, like, is that even possible?’” recalls Noyle, who had never

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25 FLUXFILES | ART

Surf photographer Zak Noyle has made a name for himself by getting up close and personal with some of the world’s deadliest breaks. Shown here, Damien Hobgood pulling in at Off the Wall.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Zak Noyle is the senior staff photographer at Surfer magazine and his clients include Red Bull, Hurley, Chanel and Quiksilver.

shot at Waimea before the contest. “I figured, Quiksilver is not going to let me die in front of 25,000 people … and it ended up being one of the greatest moments of my life, being front row and center watching the world’s best surfers ride these massive waves.”

It’s hard to contemplate how one goes from messing around in the small South Shore surf near where Noyle grew up to shooting some of the deadliest breaks in the world, including Pipeline on O‘ahu’s North Shore, Jaws on Maui and Teahupo’o in Tahiti. Though he’s surfed with his dad since he was 2 years old, Noyle believes it was swimming competitively while attending Punahou School that helped him excel as a surf photographer. “Swim practice was every day, where we had these long workouts, and I think that really helped me. … There are more and more surf photographers popping up all over the world, but I think having that swim ability helped me, because I could stay out longer, I can get out into the break a little easier.”

As experienced a swimmer as he is, sometimes nothing can prepare you for the ocean’s unpredictable power. Noyle recalls a scary close call while shooting at Off the Wall when it was breaking up to 10-feet

Hawaiian. “This wave landed right in front of me, and so I dove under. It’s very shallow, so I was just hovering there. And it just blew me up and ripped the camera out of my hand, broke the leash. I had gotten a really great shot of one of the surfers and that can’t be replaced. So I started swimming in, and I found the camera right before it hit the rocks. I tied on a new leash, swam back out, and it ended up being one of the best days of the year.”

As good as it ended up being that day at Off the Wall, it’s moments like these that convince Noyle he won’t be shooting surf photography forever. “I give myself another 10 years, tops. A lot of guys know that and end up standing on the beach, but I’m not going to be that guy. I don’t know what I’ll do. … I think Hawai‘i will always be home, but I’ve seen some amazing places, so you never know.”

For more information or to see more of Noyle’s work, visit zaknoyle.com.

Downtown's Sophisticated Lounge Daily Happy Hour EARLY Mon to Sat, 2 - 7pm LATE Mon to Thu, 11pm - 2am Handcrafted Cocktails, Wine + Beer Live Music Free Wi-Fi For private events and bottle service contact: info@bambutwo.com bambuTwo 1144 Bethel Street www.bambutwo.com Monday - Saturday 2:00pm to 2:00am

wh Y w E l O v E S u R f

C ulT u RE

IN

hawa I‘I

Sure, it may be arguable whether or not we’re experiencing surfing’s best of times or its worst, but one thing is for certain: There’s no better place to be a surfer than in Hawai‘i.

IMAGE BY JOHN HOO k

1) BEC au SE PEOP l E STI ll S ha PE BY ha N d...

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGES BY JOHN HOO k

INCI d ENTS O f

a S ha PING vOYaGE

With CJ Kanuha

The surfboard manufacturing industry has experienced a revolution in recent years that has split it into two opposing directions. On one end, some surfboard “designers” have chosen to adapt the milling techniques of advanced machinery, keeping surfboard design on the cutting edge and maintaining profitability ahead of what are derisively called “pop-outs,” sandwich-constructed epoxy boards made in China and Thailand and sold at big-box retailers. On the other end, some shapers have returned to the days before the industrialization of surfing in the ’70s and ’80s, when provincial crafting was the only way to produce a board and shapers had more in common with boat builders than industrial designers.

By the 1970s, the industry standard for producing a board originated with blanks made by California-based Clark Foam. By the 21st century, Clark Foam dominated the industry, with 80 percent of all surfboards originating as a Clark Foam blank. In 2005, the company abruptly closed up shop, causing a panic in the manufacturing industry. With the single biggest polyurethane surfboard blank manufacturer in the world halting production, shapers had a chance to think differently about crafting vehicles for impetuously dashing towards the shore.

Eventually, several old Clark Foam employees struck out to create US Blanks

and picked up where the monopolizing foam blank producer left off. But the ripple effect of the shutdown of Clark Foam was irreversible. Since 2006, the lineup now boasts boards made with carbon fiber, technologically advanced glassing, balsa, and Hawaiian woods koa and wiliwili, like the first ones ever ridden by Native Hawaiians.

In 1841, a 22-year-old New Englander named Francis ended up on the beach at Kailua-Kona on Hawai‘i Island a year after boarding a whaling ship to cure himself of being a wheezy homebody. He wrote a description of wave riding that remains valid several generations later:

I took a stroll down to the sea shore, where a party of natives were playing in the surf, which was thundering upon the beach. Each of them had a surf board, a smooth, flat board from six to eight feet long, by twelve to fifteen inches broad. Upon these, they plunged forward into the surf, diving under a roller as it broke in foam over them, until they arrived where the rollers were formed, a quarter of a mile from shore perhaps, when watching a favorable opportunity, they rose upon some huge breaker, and balancing themselves, either by kneeling upon their boards or extending themselves full length, they dashed impetuously towards the shore, guiding

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

A practice that goes back to Native Hawaiians, the craft of making surfboards is alive and well with Kailua-Kona-born CJ Kanuha.

themselves with admirable skill and apparent unconsciousness of danger, in their lightninglike courses, while the bursting combers broke upon each side of them, with a deafening noise. In this way, they amuse themselves hour after hour, in sports which have too terrific an aspect for a foreigner to attempt, but which are admirably adapted to the almost amphibious character of the natives.

- Francis Olmsted, Incidents of a Whaling Voyage, 1841

A practice that goes back to the first people to inhabit Hawai‘i, the craft of making surfboards is alive and well in the birthplace of the sport. CJ Kanuha is a force-ofnature type of guy: tall and broad hapa haole, gregarious, always talking, a physical presence on land and sea. He’s boys with half the island, the other half being either tourists or relatives. When we arrived in Kailua-Kona to surf with him, Kanuha picked us up in that neighbor island symbol of success: the moderately lifted 4WD Toyota truck with tunes and tint. Kanuha behaves like many professional athletes. Being very good at something that many of us wish we were good at, he moves through the world as though, at least physically, he’s not bound by the same rules of body, pain and intensity. A picture of him on a stand-up paddleboard 20 feet from the hot edge of molten lava bursting into the Pacific made him internationally famous a few years ago, as did his aggressive surfing style, which marked him as one of the best talents to come out of Kailua-Kona since Shane Dorian and Conan Hayes. All that youthful intensity changed a few years ago though, when Kanuha’s father was diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cruelly, his mother became ill the year after, and the tall surfer forsook a burgeoning career on tour, or alternatively as a rider on a variety of sponsored trips, to be close to his family.

Kailua-Kona is a weird place, like a mash up of the Kona that Francis Olmsted once strolled down and a 21st-century resort destination. Arriving at the beach in Kanuha’s lifted truck, we stepped out

into the blazing sun, the aquamarine of the ocean an overload on the brain. Kona has gorgeous beaches the way the rest of the state has problems. Under the shade, an uncle in vintage, blue, blocker shorts gently strummed his ‘ukulele in the calm, still hotness. On the road were dozens of knock-off Armstrongs checking their heart rate monitors under the mottled shade of kiawe trees or flying past us on carbon-fiber bicycles. The fact that they were exercising at the worst time of day proves a dead giveaway that they didn’t grow up eating Melona bars and catching the bus in front of the Banyan Store after school.

Kona has become the playground of famous one-percenters, like Paul Allen and Bill Gates, as well as numerous petit bourgeois billionaires with less famous names. “Brah, you should see the airport parking lot during Christmas time. The private jets are stacked wingtip to wingtip,” Kanuha tells me. When he’s not living the life of a professional surfer off tour, Kanuha sometimes gives lessons to the visitors through his company, Vanilla Gorilla Surf.

Though he was ill, Kanuha’s father encouraged his rambunctious son to turn his intense energy into making traditional surfboards. Kanuha has also been helped by the community of Hawaiian activistwatermen, who have always been a part of local surfing.

“I learned so much from Uncle Pohaku. He should have been named shaper of the year last year, but he’ll get it one day,” he says of professor Tom Stone, an educator at the University of Hawai‘i and an expert in pre-contact Hawaiian sports including surfing and papa holua sledding, the act of bombing down a grassy hill in a device that looks like a 10-foot-long scaffold with skids.

Kanuha’s most famous creation was a gorgeous shortboard-sized alaia he crafted in 2010 and donated to the annual Surf Industry Manufacturers Association Waterman’s Ball. On display at the silent auction, the board fetched nearly $10,000 from none other than Kelly Slater.

The day I went surfing with Kanuha, he brought out a beast of a board. When dry, the eight-foot kiko‘o, as its called in Hawaiian, displayed the remarkable properties of

Acacia koa, ranging from a straight deeprose uniformity to a curly blonde. Weighing nearly 100 pounds, the board was “too heavy for you!” as Kanuha remarked. On a waistto-shoulder-high day on a borrowed board, I attempted to line up inside of a coral head, playing it safe while triangulating the unfamiliar reef. Kanuha paddled past me and swung the trunk towards shore for a set wave. Wheeling around, the plank plunged itself straight towards the reef like a missile, and I ducked, half expecting its stern to break a few limbs as it shot up towards the sky. Then something special happened. Surfer and board emerged from the trough of the wave, with Kanuha fully erect on the back six inches of the board and cleanly navigating the shoulder-high face. An underwater bottom turn.

As we dried off, Kanuha told me about the board he’d just surfed on. “As my dad was getting sicker, he kept asking me about this board, when I was going to finish it. It was hard for all of us then. One day I just went at it, attacked the thing; did that instead of going out and punching someone.” His demeanor slowed. “He passed away a year and a half ago, just before I finished it,” he said. “Maybe you should keep it,” I replied, looking down at a yellow tail pad half destroyed by melted surf wax. “Nah. My dad wasn’t materialistic, and I’m trying not to be. Just gotta find the right buyer I guess.” And then, for the first time since meeting him 18 hours ago, he got quiet. “It’s just a board, man. There’s always more. Sometimes you gotta let things go.”

As the heat rose up from the road, we looked out on the water in the afterglow of a mid-day surf session, an impermanent act of escape. I stared out towards the lineup and saw several local kids bobbing in the sea, quietly waiting for an un-seeable energy born thousands of miles away in wind and celestial forces to rise up, crest and meet them. Then a boy caught a wave, and with admirable skill and apparent unconsciousness of danger, he impetuously dashed towards the shore.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Kanuha channeled his intense energy into hand crafting these gorgeous koa kiko‘o traditional boards.

Kanuha channeled his intense energy into hand crafting these gorgeous koa kiko‘o traditional boards.

Though technological advances have widened the playing field of surfboard shapers, Wade Tokoro remains the best in the business with his ability to fine-tune a board to a surfer’s needs.

2) ... a N d

h E d OESN'T

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGE BY AJ FEDUCIA

S l ICE d d O w N TO SIZE

Wade

Tokoro remains a fixture in surfboard shaping

In 2009, Dane Reynolds, often called the best free surfer (non-contest surfer) in the world, did what most would call crazy, taking a hacksaw to a gleaming white 6’1” Channel Islands Al Merrick shortboard and noisily sawing three inches off the back to leave a flat stump where the lovingly crafted tail once was. After which, he proceeded to connect perfectly timed airs in sweeping lines with the newly mangled equipment. In one fell slice, one of the most followed surfers in the world redefined what was cool in the water. Surfers across the seas thought, If it’s all about fun anyways, then there’s no reason not to attack your favorite board with a hacksaw. Though technology, and stunts like the one Reynolds pulled, are inciting surfers and would-be shapers to seek out innovative methods of surfboard design, Wade Tokoro’s methods remain constant.

“Guys have been going much shorter lately,” says Tokoro. “I was just out with Sunny Garcia for the last few days at Bowls, and he was digging his new 6’0”. A lot of these guys are trying to bring their performance up and are bringing boards down to as short as they can to get to that next level. Power surfing is still in, but to be competitive at the professional level, you need to be good all around. That means that I have to compensate by putting more volume in it.”

At his workspace in Kahalu‘u, Tokoro has shaped surfboards ridden by everyone from beginners to seasoned professionals and has constantly adapted his shaping to reflect the demands of his wave-riding customers. Tokoro has the look of a local Japanese surfer that could place him anywhere between 25 and 65 years old. When he tells me, “I’ve been shaping since 1985,” I think incredulously, That’s just not possible. “Surfing keeps you young, man! And what can I say, I love my job.”

As one of the state’s most popular shapers, Tokoro’s

boards are ordered by professionals visiting Hawai‘i that are looking for a local edge. Many of his orders come from guys surfing in the Triple Crown, and many more require him to shape full quivers, often putting in orders of up to eight boards at a time.

The work of shaping boards has become much easier with the advent of digital manipulation, which Tokoro and his crew have been using for over a decade. Computer Numerical Control (CNC) machines have become fully integrated into modern surfboard manufacturing, and have been used to mill exacting dimensions from stock blanks. The use of milling machines has taken Tokoro to other parts of surfing’s diaspora, like Japan and Brazil, where he’s taught shaping workshops. “It’s pretty easy now,” he says. “I can send some files over to them and get those guys going on how to both use the machine and do the fine tuning.” As the software and CNC machines have come down in price in recent years, the ability to make a world-class, highly tuned surfboard has become possible for even the most far-flung shapers.

In spite of the feasibility of crafting perfectly molded boards using the CNC, there are subtle nuances in board design that make Tokoro the best, namely his ability to fine-turn boards to meet the precise standards of his world-class surf clients. Referring to the “popouts” that have recently been introduced into the market, sandwich-constructed, epoxy boards made in dozens of places such as China, Tokoro says, “There’s no magic board for every person. So much depends on the person, skill level, fitness, height, weight and style of riding. Those are good if you’re still learning how to stand up and get down the face. But once you learn how to surf, you’re going to want to talk to a shaper, or get something that’s a better fit for you.”

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

In the congested South Shore lineup, what you do on land has no bearing on what happens in the water.

3) BEC au SE IT’S T h E GRE aT

EQ ual IZER

TEXT COMPILED BY JEFF MULL AND LISA YAMADA IMAGES BY JOHN HOO k

ON a N O v ERC a ST fall af TERNOON, T h E l INE u P ON O‘ahu ’S SO u T h S h ORE IS CONGESTE d . SE a TE d am ONG ITS fl O a TING ma SSES a RE S u R f ERS f RO m all wal KS O f l I f E.

In the water, there’s an unspoken code that everyone is forced to oblige. Out here, in the lineup, the rules and social hierarchies that forge society don’t necessarily apply; degrees become irrelevant, bank accounts provide no basis for big talk. Out here, what you do on land has no bearing on what happens in the water.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

People don’t care if you’re a millionaire or if you’ve been living on the beach for 10 years. It don’t matter, all people care about is the event they’re taking part in now, and how you are going to contribute to that.

“I progressed from bodyboarding to surfing out of high school. I found a board under my uncle’s house, an old single fin, 6’10” and I’ve been stuck on these boards ever since. It’s very seldom that I’ll go a whole week without being in the water, even when it’s small. When you surf with the same group of people and everybody’s got jobs and can only surf from four until lights out, you start to realize that everyone’s trying to do the same thing, which is trying to catch waves before the lights go out. There’s days at Bowls when it’s epic, beautiful, but it’s just too hard to catch a wave because everybody is trying to catch the same waves. And everybody is yelling at each other. It can get messy out there. Really it’s what you’re doing in the water at that moment that people will walk away with. People don’t care if you’re a millionaire or if you’ve been living on the beach for 10 years. It don’t matter, all people care about is the event they’re taking part in now, and how you are going to contribute to that.” – Trever Duarte, 29, Kāne‘ohe, at Rockpiles.

“This is the wave where I learned to surf. I surf Bowls all the time. I surf a few other places too, but Bowls is my favorite. I’m a student now at UH and we’re back in school, so I can’t spend all day every day out here, but I surf out here whenever I can. I’d say that the lineup definitely evens the playing field. Out here, it’s all about how good and how often you surf.” – Christian McDonald, 18, Honolulu, at Bowls

“I been surfing Marine Land and Kewalos since I was 12. I remember waiting on these big cement pylons, waiting for my mom to pick me up. That was 25 years ago, and surfing has been my release ever since. I always surf early in the morning, so it’s always with the same group of friends from all walks of life. You’re pulled together because of the waves and being out early in the morning. And it’s not because of a relationship, because you’re family or you work together – it’s just because you surf. I think for me now, because life is so busy – deadlines, managing hundreds of employees – it’s not about how long you surf, but as long as you get in the water and get your short fix. The whole purpose is to just enjoy what the environment allows you to enjoy. It’s a privilege.” – Brad Nicolai, 37, Kailua, at Kewalo’s.

PHOTO BY ZA k NOYLE.

“I’ve been surfing this wave since I was a kid. Bowls is definitely one of my favorite lineups. As a kid, this is where I learned to surf. I’ve spent a lot of time out here over the years, and that makes it easier to catch a few set waves. For a while, I was injured and wasn’t surfing too much, but now, I’m out here almost every day. Getting better, catching plenty waves. I can’t imagine not surfing out here.” – Billy Tom, 54, Waikīkī, at Bowls

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 39

C L o C k WISE F rom T o P :

4) BEC au SE

IT’S POSSIB l E

TEXT BY JEFF MULL | IMAGES BY ZA k NOYLE

Paddl ING IN

Big-wave surfers are changing and charging at notions of what was once thought impossible.

T h ERE’S a N u N d ENI a B l E C ha NGE u N d ER wa Y IN BIG- wav E S u R f ING.

This past October, on a freak, early season swell, guys like Ian Walsh, Shane Dorian, Mark Healey, Makua Rothman and Greg Long once again redefined the possible in bigwave paddle-in surfing by tackling Jaws with nothing more than a 10-foot gun and the paddle power of their own two hands. Previously, most people believed that because of Jaws’ immense power, speed and size, it could only be ridden with the assistance of a jet ski, with Laird Hamilton and a group of guys that came to be known as the “strapped crew” leading the tow-in push in the early ’90s. Two years ago, watercraft would have cluttered the lineup. Now, after what many are calling a historic, gamechanging session at Jaws, you’re not really pushing the limits of surfing unless you’re paddling.

IN T h E I mm E d I a TE af TER ma T h

O f T h E SESSION a T J aw S, T h E S u R f m E d I a wa S a B u ZZ

w IT h wha T T h ESE P addl E-IN S u R f ERS had a CCO m P l IS h E d

According to Maui’s Ian Walsh, a man at the forefront of the movement and pictured here, the session was indeed exceptional, but it by no means marked the peak of what’s possible. “We haven’t seen the limit yet. If the conditions allow it, I think we could see Jaws ridden even bigger,” says Walsh. “That was a big swell, but it was by no means the biggest. It was just really clean. But if we had those types of conditions with a bigger swell, I think you’d see people out there paddling it.”

Walsh says he is baffled by how fast his big-wave brethren are changing the game. “I just have to believe that this last swell was really monumental. I’ve never seen anything like it. It was just a perfect arena. Everything lined up perfectly.”

5) BEC au SE

O u R BE a C h BOYS a RE a CT uallY B eaC h BOYS

TEXT BY JEFF MULL | IMAGE BY ZA k NOYLE

f OR m ORE T ha N 100 YE a RS,

T h E BE a C h BOYS O f wa IK Ī K Ī hav E BEEN INSTR um ENT al IN T h E h ISTORY O f S u R f ING.

From the sunny shores of Waikīkī, tens of thousands – if not hundreds of thousands – of surfers found their footing on their first wave with the help of the Beach Boys. Although the Waikīkī of 1901 stands in glaring difference to the Waikīkī of today, the traits and characteristics of the Beach Boys remain the same.

At its essence, the life of the modern Beach Boy isn’t that unlike that of their legendary predecessors. From their stands in Waikīkī, the early Beach Boys, which included the likes of Duke Kahanamoku and George Freeth, acted as frontline ambassadors for Hawai‘i. For many tourists during the turn of the 20th century, including famed American author Jack London, the Beach Boys were the personification of the warmth, hospitality and aloha that have come to define the islands. In much the same manner as the originals, the Beach Boys of today pride themselves on their sense of aloha on land and their innate aptitude in the water.

“It’s a bloodline. It’s a real honor to be a Beach Boy,” says a man simply known as “Fats.” A modern Beach Boy with ample features and an even larger smile, Fats’ eyes light up when he talks about the Beach Boys of

old. “There’s been so many legendary Beach Boys,” he says, “but even today, we still get plenty legends. There’s been some changes over the years, but at the bottom, all real Beach Boys have the same characteristics. You really gotta love being down here at the beach, love working with people, and really know all the conditions. You gotta keep it simple, keep it real, and do it from the heart. You want to share the best of surfing to the visitors. That’s what it’s all about.”

Zane Aikau, nephew to Eddie and member of the Aikau surfing dynasty, was born into the Beach Boy lifestyle. For him, there’s nothing that can compare to this line of work. “A typical day for us is five hours of teaching surf lessons, two hours on the canoe, and two hour shooting da shit,” he says with a laugh. “But there’s a serious side to it, too. There’s a lot of people down here that we have to watch out for and keep safe.”

However carefree the life of a Beach Boy may sound on paper, the reality for many proves to be too taxing. According to Fats, you’ve got to pay your dues. “You can’t just show up and become one Beach Boy,” he says. “There’s duties you gotta do first. You gotta shag boards, get da people’s boards, put ’em up, get ’em set up. You can spend a year or two just doing that before you can become one instructor. In the summer, we’ll work 12hour days no problem. Plenty people come for just a few weeks or a month and realize that it’s not for them. But for me, there’s nothing else. I’ve been working here on the beach since the ’80s, and to me the best part about the job has always been, and I think will always be, seeing someone catch their first wave, seeing them look back at you with this huge smile. It’s the best.”

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

For Alex Florence, the ocean saved her life, helping her raise her three boys, John John, Nathan and Ivan.

For Alex Florence, the ocean saved her life, helping her raise her three boys, John John, Nathan and Ivan.

6) BEC au SE IT CONNECTS m OT h ERS

w IT h SONS …

Alex, Her Three Sons, and the Sea: A Typically Divine Family

TEXT BY BEAU FLEMISTER | IMAGE BY DANIEL RUSSO

al E x fl ORENCE IS a GO dd ESS. S h E IS ST u NNING a N d

P a RT-GO d a N d

ma YBE I mm ORT al

Her voice is soft, between a song and a whisper, and when angels hear her speak, they sigh. She was either born in New York, or in the sea, and then floated heavenward toward the presentday Mount Olympus otherwise known as the North Shore. She bore three half-god children, like some goddesses do, and then raised them on her own, like some women do. But then she kept her goddess figure after all three, which to this day confounds both gods and mortals alike. She is something special. But she is modest.

“The ocean saved my life,” says Florence. “The beach was like another parent — it raised my boys with me.” It did. Florence, her three boys and the ocean played many a day together as one big, golden, salty family. She taught each of her boys – 20-year-old John John, 18-year-old Nathan, and 16-year-old Ivan — to surf shortly before they could walk, but slightly after they could swim.

But goddesses on the North Shore are not like the goddesses of old. They are not

languid and disinterested and adorned in luxury like they used to be. Some goddesses, in our recession-prone tourist economy, are busy raising three boys and finishing school. Some goddesses must schlep their boys to Savers at 11 p.m. to buy them reasonably priced clothes. “Being a single mom,” she recalls, “sure, it’s hard. But my boys make me laugh. And we’ve always been together at all times, so we’ve shared it all: the tears, the laughs, the surf, the whole thing.”

Florence did not just teach her sons to surf some sissy, mortal wave, like Freddy Land or Chun’s, though. She taught them, then surfed, and still surfs with them, at the most deadly wave on Earth: Pipe. And she taught them sea-wisdom. She taught them to be bold. “Oh, sometimes they’d get scared,” she says. “Little boys do. But I’d say, ‘Suck it up, it’s not that cold,’ or, ‘it’s not that big.’”

Her three boys are now all professional surfers. The oldest, John John, competes on the World Tour and is revered by the best surfers in the world. He may receive fines in the future for an unfair, performance-enhancing advantage when the Association of Surfing Professionals judges discover that he is half-god. Florence remains modest. “It was survival,” she says with a laugh. “I took them to the beach all day to tire them out. When you’re surfing and swimming

and playing in the sand for 10 hours — it’s the best way to get them to go to bed.”

The wisdom of a goddess is infinite. Like some goddesses and most mothers, Florence is omnipotent. No, omnipresent, or one of those two anyway. Even before John John was on tour, once her boys got sponsored, she would travel and surf with them across the globe. Now, John John’s professional obligations just give her a perfect excuse to tag along. “It’s pretty simple,” she says. “When we surf together, we have fun. It’s incredible to share the sea with them. It’s something we will always have. It’s our bond.” She continues to surf with her boys. From ‘Ehukai to Rio de Janeiro, she shadows them. She guides them. And she doesn’t stop at the sea. She rides great frozen mountains and glides on four wheels over plywood and concrete with her boys, too (“I got my feeble-grinds down now!”). She’s even up in Kahuku these days sputtering about, hand on the throttle, engine screaming, spitting red dirt into the clouds. Alex Florence is amazing. She raised three beautiful and fearless half-god boys on her own. She loves them wholeheartedly, made countless sacrifices for their wellbeing, follows them to the ends of this Earth. Like a goddess should; like all mortals mothers do.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

Legendary big-wave surfer Tony Moniz never pushed his kids to surf. The love for the ocean developed naturally among his sons and daughter Kelia, who is now the face of Roxy.

Legendary big-wave surfer Tony Moniz never pushed his kids to surf. The love for the ocean developed naturally among his sons and daughter Kelia, who is now the face of Roxy.

7) … a N d faT h ERS w IT h dau G h TERS

Moniz Is the Name: Growing up in the Waves of Waikīkī

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON IMAGE COURTESY

OF TAMMY MONIZ

I f YO u a SK TONY m ONIZ, T h E OCE a N ITSE lf T au G h T h IS dau G h TER ITS wa YS.

Its waves guided her in paddling out, time in its breaks showed her how to walk the nose; its cerulean surf led her to love the sport as much as she does to this day.

But it’s the legendary big-wave surfer and dad who brought her to the beach. For about six months during Kelia Moniz’s hanabada days, the rising sun meant cramming into a 15-passenger van with her parents and four brothers, a dozen soft-top longboards strapped to the roof. Inside, the Moniz crew packed a pop-up tent, pots and pans for lunch, and an assortment of math and science textbooks – all the components necessary for the Waikīkī- and world-renowned Moniz clan to take their homeschooling right in front of Queens and Canoes. For this time, the kids learned to add and subtract on the sand while their parents set up the beach boy school Faith Riding Company, which now has four stands along the tourist-hungry frontlines.

“They were just rugrats, Waikīkī beach rats for a while,” says Tony. “We’re down at the beach and teaching surfing every day and all the boards are up there. No one did a land demonstration with them, or showed them how to pop up, like I do every day. It was like, here’s a board, go out and play.”

Now, at just 19 years old, Kelia is the face of Roxy, though she’s been traveling the world with the company for competitions and photo shoots since age 13. She’s the girl in the campaigns smiling with her toes on the nose in remote turquoise waters. Her four brothers are outstanding surfers as well, all four surfing competitively and one following in the footsteps of their father, passing on the stoke with every perfectly-timed push.

But Daddy Moniz is proud of the fact that he and his wife Tammy never, ever pushed them to pursue the sport. He waited for that love to grow roots on its own, right in the Waikīkī waves, just the way it worked for

him. Back in the early 1970s, Tony was biking to Waikīkī from Kalihi with his brother, ditching his sixth grade classes to surf. Long before then, you could already find him in the lineup at Waikīkī breaks, the youngest among a tight-knit crew of five including a brother and three cousins. This posse fostered both Tony’s competitiveness, which led him to beat them all in his first competition at the tender age of 8, and nurtured his love for the sport that he now claims is in his DNA.

And this DNA makes itself apparent in Kelia, a feisty, goofy-footed longboarder who can ride anything and who grew up taking on first longboards and then shortboards with her brothers on practically every South Shore wave. While she was already competing for Roxy on a shortboard by the age of 13, it’s free surfing and longboarding that have her heart, and what she returned to at the age of 16.

“She’s such a queen on the longboard. Her gift is the longboard,” says Tony, a determined, proud look on his tanned face. “When she paddles a longboard, she looks good. When she stands on a longboard, it’s, like, beautiful. It’s something that you can’t train someone to do. It’s like that person who picks up and plays jazz music. You can’t train someone that gifted natural ability. And that’s her on a longboard.”

Just as obvious in the Moniz DNA is – and there’s no other way to say it – the aloha spirit, which they wear with pride. There’s always a smile for you, no matter whether you’re a 9-year-old haole boy learning to surf or the auntie stopping by to say hello. “My dad’s reputation … I’ve been to so many places around the world, and ’til this day I’ve never gone to one place where people didn’t know him, and they always have such good things to say about him,” says Kelia, at a coffee shop in Manhattan Beach in California, where she’s based. “And that’s always something I want to do when I travel, is to meet people and always have them remember me for being a good person.”

It’s in the DNA.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 49

8) BEC au SE l EGEN d S STI ll

l I v E h ERE

Lost and Found:

When living legends are re-encountered in their own backyard

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON

IMAGES BY AARON VAN BO k HOVEN 1970S PHOTOS COURTESY OF THE LOST AND FOUND COLLECTION

“All you had to do was put the pictures in front of them. Because now they’re in their 50s or 60s, and you’re this guy who’s holding their past from their 20s, when like, they think they’re gods, you know? They didn’t even know any better. They didn’t know any better, they didn’t make money. They were just living the life.” – Doug Walker, creator of surf documentary Lost and Found.

The 1970s photos featured with these three living legends were discovered by California native and lifelong surfer Doug Walker at a flea market in Pasadena, California – 30,000

black and white negatives packed away in manila folders in three file boxes. Recognizing a treasure trove from his childhood era, he bought them all, learned that they were lost carbon copies from Surfing magazine dating from the ’70s through the ’90s, and toted them around California and out to Hawai‘i to track down as many people as he could who knew what the pictures meant. The results can be found in his documentary, Lost and Found. These are the photos and lives as defined by the surfers.

thelostandfoundcollection.com

BUTTONS k ALU h I ok ALANI

1976: 16 years old, free-surfing at Off the Wall. This is Buttons’ first photo in a surf magazine, when he was still just running away from home and living on the beach on North Shore to surf.

2012: 54 years old at Off the Wall. He runs Buttons Surf School and gives back to the community via surf lessons for disabled children whenever he can. He has eight children, nine grandchildren and lives with his wife in Waialua. He still surfs everything from Off the Wall to Backdoor to Waimea Bay –especially when there are 20-foot swells.

On running AwAy frOm hOme:

“Listen, when I was a kid, there was nothing here,” he says while walking down the narrow path to Off the Wall. “This path was here, there were three houses, old-school style. So when I was a kid, and I would run away from home, I’d come right here to this beach. Sometimes I’d go to Chun’s Reef. I had a tent, I had a hibachi. All my aunts and uncles would report back to my mom, ‘Oh yeah he’s OK.’ When the waves would get big, 20 foot, they would wash away all my camping stuff. It was amazing, growing up in Hawai‘i, brah.”

On cOming full circle:

“There’s an organization called Access Surf. I been taking people with quadriplegia, paraplegia, and autism kids surfing every first Saturday of the month for the last five years. I’m like the guru. I can take anyone surfing and get them up on a wave. For me, also, as being a recovering drug addict, I’m not embarrassed to say anything, it is what it is, you know. So today, for me, life is good. I got that 1-yearold girl and that 5-year-old son, and so it’s like full circle of life, you know? My life has gone around, and now today I give it to the kids that I think I can help and to give back to my kids, you know.”

LARRY

BE r TLE m ANN

1979: 24 years old, free-surfing Backyards at Sunset Beach. This was in the midst of Bertlemann’s pro career, during which he landed a record nine magazine covers between 1974 and 1984. The board he’s on was one he shaped and made the logo for – his Olympic rings represent breaks on five different continents.

2012: 57 years old, standing at Sunset Beach with Backyards in the background. Today, Bertlemann is “shaping boards and signing autographs” to get by, having taken on racing cars and martial arts before dropping off the map in the late ’90s. He has three children, seven grandchildren, and splits time between Town and North Shore. The combination of a pinched nerve in his vertebrae and an aneurism paralyzed the right side of his body in 2000, and only recently has he been able to body surf a gain.

On bOttOm turns:

“I could tell you, honestly, I haven’t seen anybody that can do a bottom turn like that yet,” says Bertlemann, looking at the shot while sitting in the sand at Sunset Beach. “That’s going so fast. That board is an 8-foot, 8-inch pintail that I had. But to make a turn that hard that low, you have to be going so fast.

On tOuring:

“I was third in the world in ’72. That was pretty cool. At 16, 17, I was third in the world. I didn’t know what the hell we were doing. They had a contest at Pacific Beach in California. I remember it very well because we had four hotel rooms, and we just trashed them all.”

On AeriAls:

“I was hoping that surfing would be in a whole other dimension by now. I mean, from when I first started surfing to when I left, surfing changed leaps and bounds. Everybody was doing these real long, drawn out turns, really slow style of surfing. Then I took all those lines, those figure-eight lines, and put them all into the pocket. That’s when I started flying. They said, ‘Flying is impossible,’ and I said, ‘Yeah, yeah right.’ If it wasn’t for skateboarding, I don’t think I would have flown. Because to do this maneuver, the aerial, it’s sort of backwards from surfing because you’re putting all your power on the bottom part and the turn, and by the time you get to the top you lost all of your power. If you try turning at the top part of the wave, you fly higher, but the board will get away from your feet. So what you gotta do is suck your legs in and let centrifugal force carry it across. And that’s how I figured it out, through skating.”

JOCK

SUT h E r LAND

1971: 23 years old, watching an amateur competition at Sunset Beach. Here, Sutherland was freshly returned from the Army. He had been ranked number one in Surfer magazine’s Surfer Poll right after he had enlisted in the U.S. Army and returned to North Shore to compete two years later.

2012: 64 years old, standing in front of Pipeline. Sutherland held the title of “Mr. Pipeline” throughout the ’70s, a name bestowed upon the break’s most progressive waveriders and also held by Gerry Lopez and Jamie O’Brien. He has been a roofer for 40 years, has two grown sons, and lives on the North Shore. Jocko’s, named after Sutherland himself, and Pipeline remain some of his favorite breaks.

On returning frOm the Army:

“Seeing the photos was a lot of bringing back the old memories. Like, I am 23 years old here,” says Sutherland, his finger on the photo while sitting at a picnic table at Pipeline. “I’d guess I’m thinking, somebody’s taking a picture of me and maybe I look kind of like a geek because my hair was dark,” he says, referring to his lack of sunbleached hair due to his recent stint in the Army. “And the way my eyes look, I probably had a beer or two.”

On his style:

“My style wasn’t a smooth flowing style, so to speak, and people wouldn’t call it awkward but they would call it unique. … Surfing will take out of your style any real awkwardness pretty quickly because of the way the wave works. Because I learned to switch feet when I was younger, sometimes I would be halfway into deciding, Should I switch feet for this one or should I go backside or grab the rail? So sometimes there would be a moment of – not doubt –but a moment of a noncommittal feeling, caught in the middle of something.”

On the s urfer POll:

“So in 1969, John Severson was filming us as part of this movie Pacific Vibrations … I think he wanted to pave the way for the selection of me as number one guy. I was supposed to be this so-called star of his movie like six months before the Surfer magazine poll was going to come out. Unfortunately for him, maybe, and for me, I didn’t know that he had an ulterior motive in bringing out the movie,” he says. Severson, the founder of Surfer, intended to build up to naming Sutherland top surfer in the world. “By the time the movie came out, I had already joined the Army. And so I’m in basic training and one of the company commanders comes down the street with a magazine with me on the cover, number one Surfer Poll, and the commander goes, ‘Is this you?’ And I said, ‘Yes, that’s me,’ knowing I was a marked man from then on. … They picked on me a little more thinking I was trying to escape something. I just wanted to do something honorable in my community.”

With surfing a state-sanctioned high school sport, students like Zeke Lau, shown here, are able to excel in the sport they're passionate about, while preparing for the future.

9) BEC au SE IT wa S h ERE, IN ITS BIRT h P laCE, T haT T h E SPORT O f

KINGS

wa

S f IRST

RECOGNIZE

d a S a N O ff ICI al h IG h SC h OO l SPORT

Stay in School:

Kamehameha Schools’ high school surf team is showing the state, and the nation, how it’s done

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGE BY ZA k NOYLE

In 2011, Hawai‘i became the first state to officially recognize surfing as a high school sport, although as with anything requiring legislation, the organized rules that will officially bring surfing to the competitive standards of other sports, like baseball, football, judo or canoeing, are still in development, and surfing, two years later, remains a club sport. But when the first official interscholastic high school contests happen as soon as the 2013 school year, Kamehameha Schools, and its surf team’s head coach, Lea Arce, will be there.

Hawai‘i is the spiritual birthplace of surfing, but for better or worse, California remains its hub. The first documented wave riders in California were Hawaiian princes. While on a world tour in 1885, Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole and brothers Edward and David Kawānanakoa stopped by Santa Cruz. Seeing waves breaking off the mouth of the San Lorenzo River, they spent a few days fashioning boards from redwood and caught a few sets in the frigid central coast waters. At the turn of the century, George Freeth, a one-quarter-Hawaiian lifeguard, moved from his home in Honolulu to Redondo Beach. He befriended novelist Jack London, who wrote of his experience surfing with the waterman, “Shaking the water from my eyes as I emerged from one wave and peered ahead to see what the next one looked like, I saw him tearing in on the back of it, standing upright with his board, carelessly poised, a young god bronzed

with sunburn.”

It was London’s description of surfing that first introduced many Americans to the activity. By the time The Duke was making movies about surfing in the ’20s and ’30s, surfing was a growing phenomenon, and the ancient Hawaiian sport has had a relationship with Hollywood ever since. Throughout the 20th century, Gidget, Miki Dora, three brothers from Hawthorne who called themselves the Beach Boys, and most of the touring professionals came from beach towns off the west coast of the North American continent.

When other non-arena sports like water polo, judo and even soccer were emerging as interscholastic athletic options for youth in the late ’70s and early ’80s, surfing was stereotyped as the activity of California slackers. Think of the Spicoli character in Fast Times at Ridgemont High, any character played by Keanu Reeves pre-Matrix, and Michelangelo from the Generation X-Y touchstone Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, whose stoked nasal phrasing, constant clowning, and vocal advocacy for ditching important missions in favor of post-session pizzas have become a tenet of our collective unconscious.

It was this sort of stereotyping that local surfing educators have had to combat. But like all stereotypes, the one of the slacker surfer kid is based in some truth. Part of the danger in allowing surfing to become an official, state-sanctioned sport has been fear that students will just stay in the water and allow their stoked vocabulary to be reduced to a grating staccato of dudes, likes and that was siiiicks

For local baby boomers who remember their peers ditching first and second period for south swells, and who now find themselves as school administrators, it is this sort of fate they have avoided for their students.

Since 1978, the California-based National Scholastic Surfing Association (NSSA) has had those dangers in mind. Requiring that students maintain a minimum 2.0 GPA, the NSSA now has more than 80 contests with students competing from all over California, Hawai‘i, Florida, the Carolinas and New Jersey, and has maintained a philosophy that academics and wave riding are not mutually exclusive.

Despite California’s love affair with surf culture, surfing still remains a club sport in the Golden State. Still, the level of competition remains high, with many high schoolers emerging from successful NSSA experiences to become professionals in some manner. With some students believing surfing to be their best shot for success, they are homeschooled to allow for mid-day surf sessions. Other students maintain their normal lives as high schoolers while given certain allowances by their school for competitive pursuits. It was partly this sports tradition that brought Lea Arce to California to study. “After I finished my masters in education in San Diego, I taught in Orange County for a year,” remembers Arce. “I saw how those California high school clubs organized themselves, and I kept in mind that I needed to do the same thing when I got back home.”

When Arce was hired at Kamehameha Schools Kapālama Campus, she got to apply both her academic and non-academic

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 57

training. “What we did was figure out all the things that took a lot of paperwork, like coaching, fundraising, liability, transportation and countless other things,” she says. Under Arce’s guidance, the team has won three state championships against its nine interstate rivals and has attended the NSSA Championships for four years. This past summer saw their best team result, fourth place behind powerhouse Southern California teams San Clemente, Newport Harbor and Huntington Beach. When the O‘ahu Interscholastic Association and Interscholastic League of Honolulu (which represent public and private school sports, respectively) figure out what Kamehameha Schools already has, Arce’s students will compete against surfers from all around O‘ahu, and hopefully neighbor islanders, in a statewide competition.

During surf team practice, Arce has the experience organized for her students. “We’re limited to a team of 25 kids, boys and girls. We have qualifiers at the beginning of the school year and start competing in October,” she explains. “These contests are a lot to put together, but thankfully Wendell Aoki, the president of the Hawai‘i Amateur Surfing Association, does a lot of that work. That means we can focus on getting our kids ready to compete.”

On a Saturday practice with the girls on the team, Arce takes on the role of both coach and maternal figure. When a female longboarder catches a knee-high wave, makes a clean bottom turn, and subsequently spends the rest of her time on the open face adjusting her swimsuit top, Arce admonishes loudly enough for all her girls to hear: “What’s the number one rule, ladies?” As they smile and hunch their shoulders, she answers for them, “Get a suit that keeps it all together!”

With Arce putting in double duty as a biology teacher and track and field coach, the coaching of the Kamehameha team is divvied up between several adults: professional surfer Jason Shibata, Waves of Resistance author Isaiah Walker, surf journalist Daniel Ikaika Ito, as well as numerous parents and other volunteers who do what is done in other youth sports: whatever it takes to get the kids competitive. They also bring their student-athletes to volunteer at various charities and fundraisers throughout the year as a way to give back and, when competing in California, tour the kids around college campuses.

In sports movies, the coach character is usually played one of two ways: as a rational, reliable, parental figure, or as a, well, more competitive type. Assistant coach Daniel Ikaika Ito falls into the latter category. A 1999 graduate of Kamehameha Schools, he is now

ThE roAD

To goINg Pro

(Is possible for just a small few, and is relatively short lived)

Jun Jo and Jeff mull present a completely unscientific map on the road to going pro.

6-8 years

win first menehune contest. creepy [insert brand] rep starts tossing you shades and stickers.

catch first wave.