THE Stewardship ISSUE

Understanding Hawai‘i’s Climate Crisis

The Village: Bumpy Kanahele’s Nation of Hawai‘i at Pu‘uhonua o Waimanalo

Holistic Healing at Ginger Hill Farm

While controversy rages on about agriculture-zoned land used for residential development, a few passionate farmers on Maui are showing the rest of the state what’s possible.

Sink or Swim | 30

The conversation regarding climate change is a developing issue being held on global transactional stages, in classrooms, and increasingly, in the arts. Writer Sonny Ganaden talks to native Hawaiian attorney Mililani Trask, along with other indigenous persons of the Pacific, all of whom are offering real, and at times contentious, solutions about how to react to rising waters.

Changing o ne’S Traje CTory | 36

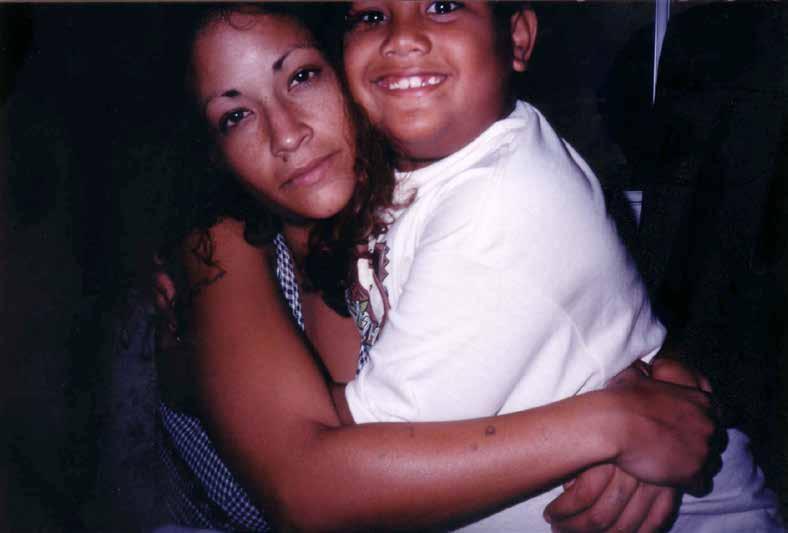

Despite a tumultuous childhood surrounded by homelessness and drug addiction, Keoni Rivera recalls how foster care and family eventually came to change his life and explains why amendments to its current state are necessary. Photography by John Hook.

Sowing SeedS of Con T rover S y | 42

Despite the potential to make a crooked but sizable profit on gentleman farms, a few farmers are using their land for what it was intended—cultivating thriving crops. Photography by Matt Alvarado.

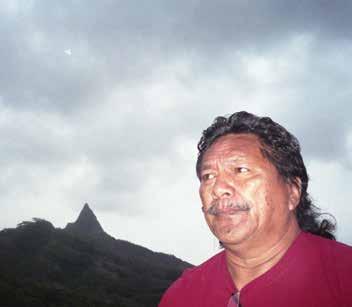

The v illage | 48

Bumpy Kanahele, Head of State to the Nation of Hawai‘i at Pu‘uhonua o Waimanalo, is fostering a community dedicated to the perpetuation of Native Hawaiian practices and values. Writer Beau Flemister and photographer Jun Jo go off the grid to tour the sprawling 45 acres of land given to Bumpy by Governor John Waihe‘e in 1994.

m aking PeaC e aT g inger h ill farm | 55

At Ginger Hill Farm, located on the “green belt” of Hawai‘i Island’s Kona coast, internationally recognized artist Mayumi Oda and her son Zachary Nathan encourage holistic health, peacemaking, and organic farming. Photography by AJ Feducia.

l e f i T f ê T e | 60

Get healthy! Get active! Take care of your body in today’s most on-trend looks in this fashion editorial styled by Aly Ishikuni and Ara Laylo and photographed by Chris Rohrer.

Thorben Wuttke celebrates woodworking as an artist’s trade by bringing together artisans specializing in wood and metal work at his co-op space Oahu Makerspace.

edi Tor ’S le TT er ma ST head

Con T ri BUTor S le TT er S To T he edi Tor

whaT T he flUX?! | 15 IS UP WITH GMO?

lo C al mo Co | 18 WALLY “FAMOUS” AMOS

FLUXFILES : ar T | 20

SEAN CONNELLY

FLUXFILES : de S ign | 22

OAHU MAKERSPACE

FLUXFILES : m US iC | 26

MARK KOGA

in flUX

ge T healT hy ! | 69

FOOD: GREENS & VINES

a + a on T rend | 72

viewfinder | 80

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

Bruschetta of eggplant confit, herb goat cheese & basil aioli

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

Bruschetta of eggplant confit, herb goat cheese & basil aioli

ON THE COVER

ARTiculations: Carolyn Mirante

Owner/director of the Gallery of Hawaii Artists blogs on arts and culture in Hawai‘i and elsewhere, with topics like fanfare for the movie Spring Breakers and the newest exhibitions at LACMA.

BEHIND THE SCENES

Le Fit Fête

Go behind the scenes of our Le Fit Fête fashion editorial. From stylist’s pulls to hair and makeup magic, check out how this fashion editorial comes to life in this exclusive video edit by Haren Soril.

We may be a quarterLy, but We’re bringing stories aLL the time onLine. Stay current on arts and culture with us at: website: fluxhawaii.com facebook: /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii

When I was growing up, my family would go camping every year at Bellows Beach Park. I remember getting stung—and the excruciating pain that followed—by a nasty Portuguese man o’ war one year. The little sucker had wrapped his stringy blue tentacles around the length of my arm. After that, I was determined that no one experience that kind of pain, so every time when we went camping, I made sure to comb the campsite’s broad beaches for man o’ wars, gingerly picking them up between chopsticks and dropping them into a 7-Eleven Styrofoam cup until it was filled to the brim. Just doing my part, for the good of beachgoers everywhere.

Putting this, the Stewardship issue, together, I’ve come to realize that the idea of stewardship is a complex one. It’s not simply a matter of doing what’s right, because for many, “right” is relative. I assumed I was being a good steward years ago, protecting all those people from the wrath of the man o’ war; the jellies, I’m sure, would beg to differ.

Not even halfway through the year, and already protests have spilled into the streets of Hale‘iwa, shoving matches have been caught on tape at the State Capitol, outbursts have erupted in the legislative session—all in the name of what’s right. The war on GMO, the debate about energy, the fight for land-use—I believe the emotions and actions attributed with these issues stem from a place of good, of a genuine interest to

see that Hawai‘i is lively, beautiful, and secure for future generations. Some call it naivety, I call it eternal optimism.

Stewardship can take many forms—including of land, of each other, and of ourselves—still, there is such a thing as “right,” absolutely. There is a right way for responsible stewardship, and we only have to look to the ancient Hawaiians for guidance. Their establishment of the kapu controlled when and how resources were used. Senator J. Kalani English, in a bill to establish a commission to manage the state’s natural resources wrote this in 2007: “As the native Hawaiians used the resources within their ahupua‘a, they practiced aloha (respect), laulima (cooperation), and malama (stewardship), which resulted in a desirable pono (balance). This is sound resource management where the interconnectedness of the clouds, forests, streams, fishponds, sea, and people is clearly recognized. … Through sharing resources and constantly working within the rhythms of their natural environment, Hawaiians enjoyed abundance and a quality lifestyle.”

We surely will never agree on all things, at all times, but I would hope to find middle ground somewhere on this trembling landscape we call home.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada EditorFLUX HAWAII

Jason Cutinella PUBLISHER

Lisa Yamada EDITOR

Ara Laylo

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

SENIOR STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

FASHION

EDITOR

Aly Ishikuni

ONLINE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Matthew Alvarado

AJ Feducia

Jun Jo

Jonas Maon

Chris Rohrer

CONTRIBUTORS

Beau Flemister

Jeff Mull

Keoni Rivera

Sarah Ruppenthal

Naomi Taga

COPY EDITORS

Anna Harmon

Andrew Scott

INTERNS

Marcela Biven

Keoni Rivera

Haren Soril

Chanel Wayne

COVER PHOTO

Matt Alvarado

BEAUTY

Ryan Jacobie Salon

Risa Hoshino

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Keely Bruns VP Marketing & Advertising kbruns@ nellamediagroup.com

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock Chief Operating Officer joe@ nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne

Business Development Director gpayne@ nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro National Account Manager jmiyashiro@ nellamediagroup.com

General Inquiries: contact@ FLUXhawaii.com

Published by: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

2009-2012 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii. com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

MATT ALVARADO

M ATT A LVARADO IS A COMMERCIAL AND DESTINATION WEDDING PHOTOGRAPHER BASED ON M AUI WHERE HE LIVES WITH HIS 2-YEAR - OLD SON , M IKAEL , AND HIS WIFE , C HANELLE .

He is the owner and principle photographer of Beloved Photo Boutique. When not on photo shoots, Matt enjoys bodybuilding, cooking, Jesus, firearms, and good whiskey, though not necessarily in that order. Matt was born and raised in Texas. He is proud of it.

BEAU FLEMISTER

B EAU F LEMISTER IS A WRITER FROM K AILUA ON O‘ AHU ’ S EASTSIDE .

Currently based in San Clemente, California, he is the managing editor of Surfing Magazine. He has had works published in various magazines across the globe and has traveled extensively to more than 50 countries. He is finishing his first novel entitled In the Seat of a Stranger’s Car

CHRIS ROHRER

C HRIS R OHRER IS AN ANALOG PHOTOGRAPHY ENTHUSIAST WHO SPENDS HIS FREE TIME IN A VAN , FLYING A KITE , OR BROWSING THE I NTERNET FOR WOLF PICTURES

Chris is currently an active member of the Analog Sunshine Recorders and the Surf Kook Surf Club.

SARAH RUPPENTHAL

S ARAH R UPPENTHAL IS AN AWARD - WINNING JOURNALIST, FREELANCE WRITER AND INSTRUCTOR AT U NIVERSITY OF H AWAI ‘ I M AUI C OLLEGE

Her stories have appeared in FLUX Hawai‘i, Wailea Magazine, Maui Nō Ka‘Oi Magazine, Maui Weekly, The Maui News, Green Magazine Hawai‘i, and a number of other local publications. Ten years ago, she left the misty metropolis of Seattle to thaw out under the sunnier skies of Hawai‘i. Today, she lives on the North Shore of Maui with her husband and 135-pound “puppy,” Odie.

I think this was a GREAT fashion issue. And I do not typically feel like Hawai‘i Fashion issues hit it, but this one did. There were many people I hadn’t heard about, and that is great! I loved that it wasn’t just an overuse of the words “trendy, chic, haute” (I read that a lot here and always wish that it would be more sophisticated all around). You folks have raised the bar for fashion coverage in Hawai‘i. Great job to you and the entire team for a fantastic issue.

Much aloha,

Ari Southiphong

Andy South

W E WE lco ME and valUE yo UR f EE dback. Send letter S to the editor via email to li S a@fluxhawaii.com or mail to flux h awaii, P.o. Box 30927, h onolulu, hi 96820.

Re: Some Things Gold Can Stay, a story by Beau Flemister about Hawaiian bracelets

I recall Beau telling me quite a few years ago, fondly, that one of his childhood memories was of my bracelets clinking and clanging as I would come in each night to tuck him in. About three years ago, the clanging started to annoy me. I wore four gold Hawaiian bracelets and never took them off. I ran with them, showered with them, slept with them. For some reason the clanging, the clatter, the banging on my wrists, had become obtrusive. I began to take all but one off—the one that said “Eme Lina” on it and was engraved with “Love Kyle and Beau 5-13-84.” The bracelets had suddenly become a nuisance. Until…Beau told me he was writing an article about Hawaiian bracelets. “I think you’re really gonna like this one, Mom.” I got the magazine today. I am proudly wearing all four bracelets again. Now each time they clatter, bang, jingle, slide, and get caught on one another, I will lovingly think of the impact that sound had on Beau. The bracelets are back—a queen has risen.

Amy Stein CORRECTIONS

We incorrectly printed the name of Chris Sy’s artisan bread company. It is called simply, Breadshop. You can find out more about what’s called the “best bread in Hawai‘i” by visiting breadsbybreadshop.com or on Twitter @breadshophnl.

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

IS UP WITH GMO?

Most people probably don’t realize they’re already eating genetically engineered foods— and have been since the mid-1990s. It’s estimated that more than 60 percent of all processed foods on supermarket shelves—you know, those familiar things you reach for regularly like chips, cookies, pizza, and ice cream— contain ingredients from engineered soybeans, corn, or canola.

Despite this, the concern about genetically engineered foods has reached fever pitch as of late with countless pages of information being disseminated on both sides and from around the world. “These crops have failed to provide significant solutions,” stated the National Farmers Union in Canada. “Their use is creating problems—agronomic, environmental, economic, social, and (potentially) human health problems.”

On the other hand, Mark Tester, a research professor at the Australian Centre for Plant Functional Genomics at the University of Adelaide, reasoned, “If the effects are as big as purported, … why aren’t the North Americans dropping like flies? GM has been in the food chain for over a decade over there—and longevity continues to increase inexorably.” Meanwhile, the headlines continue to read like science fiction. Of the thousands of headlines clamoring about the newest in GMO, we pulled five of the most relevant that show how we got here, and where we are headed.

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

IS UP WITH GMO?

HEADLINE THE NEED MODIFICATION HELL NO

“BIOTECH PAPAYAS A THREAT”

Honolulu Star-Bulletin September 11, 2004

To combat ringspot virus, which threatened to wipe out Hawai‘i’s papaya production.

Local USDA plant virologist Dr. Dennis Gonsalves developed a genetically modified papaya variety that was resistant to ringspot: the Rainbow papaya. Similar to how vaccines can improve immunity against diseases in people, he used the ringspot virus to inoculate papaya trees and create the new version.

Russell Ruderman, owner and operator of Island Natural Chain on the Big Island, said in a report by KITV that while GMO saved crops, it also “cut prices, stunted testing on traditional breeding, and fueled a negative perception. … For better or for worse, we took our whole papaya industry and put it into this category of foods that people are boycotting across the country.”

“GMO TARO PITS HAWAIIANS AGAINST SOME SCIENTISTS”

Honolulu Advertiser

April 3, 2007

“MONSANTO CORN CAUSES TUMORS IN RATS, STUDY FINDS”

Global Post September 19, 2012

“DON’T FEAR THE FRANKENFISH”

The Atlantic March 22, 2013

To protect taro from widespread modern plant disease.

To resist herbicides and repel pests in order to increase crop yield.

Researchers intended to insert resistant genes from rice, wheat, and grapes, which would ultimately alter the basic structure of the plant that many consider culturally sacred.

Roundup Ready sweet corn produced by Monsanto (one of the largest suppliers of herbicides in the world) is genetically modified to repel pests and withstand glyphosate, an active ingredient in herbicides such as Roundup, allowing farmers to spray their crops to kill weeds while leaving the corn unharmed.

“What we’re really angry about is that the biotech industry has turned this into a genetic modification issue,” said Hawaiian activist Walter Ritte, who believes the issue is about preserving the purity of the taro rather than the scientific merits of genetic modification. “This is about us protecting our family member,” he said in a 2007 article in the Honolulu Advertiser.

In a study where rats were fed Roundup Ready corn for two years, French scientists reported that both females and males developed cancer and died at higher rates than controls. The study, published in the Food and Chemical Toxicology journal, included pictures of mice with large tumors as evidence of their research.

To satisfy the world’s insatiable desire for fish and to fight world hunger.

AquaBounty Technologies’ AquAdvantage enables salmon to grow to market weight in about half the time of a regular North Atlantic salmon.

In a letter to FDA Commissioner Margaret Hamburg, environmentalists and consumer groups implored her to evaluate the worst-case scenario if GE salmon were introduced into the market: that it would escape the confines from which it was raised and “inflict unknown consequences on the environment.” Their evidence, according to the LA Times, leans heavily on the Trojan Gene effect, which states that a specific genetic advantage (in this case, AquaBounty salmon’s ability to grow faster) “enables it to outcompete unaltered salmon, leading to their demise.”

STATUS LET’S GO

Ken Kamiya, who has been growing papaya in Hawai‘i for 40 years, said he was forced to cut down half of his orchard in the 1990s because of the ringspot virus, as did many of his fellow farmers. He began growing genetically modified papayas in 1998 and credits the transgenic papaya with saving the local papaya industry.

Virtually all of the papaya available in Hawai‘i is locally grown, and nearly 90 percent of that is genetically modified. Rainbow papayas have been sold in Hawai‘i since 1998, Canada since 2003, and Japan since 2012.

“Just because there is research on a particular product does not mean it will end up as a commercial product,” wrote Stephanie Whalen, the president and director of the Hawai‘i Agriculture Research Center, in a 2008 editorial in Honolulu Magazine that opposed a moratorium on genetic engineering of taro. “Any real-world application of genetic engineering of taro would require the cooperation and support of local taro growers and significant funding from the public sector.”

Research on native Hawaiian taro remains halted, though researchers continue to conduct lab tests on a Chinese variant of taro. The moratorium on research on native Hawaiian taro expires this year.

Immediately after the results were published, a torrent of criticism rained down on the study, calling it a “statistical fishing trip” that used questionable methods, tumor-prone rats and poor statistical techniques. An article by Steven Salzberg in Forbes summed up one of the report’s major flaws: “There’s no dosage effect. In other words, if Seralini [the lead researcher] is right and GM food is bad for you, then more of it should be worse. But the study’s results actually contradict this hypothesis: Rats fed the highest levels of GM corn lived longer than rats fed the lowest level.”

William Muir, author of the Trojan Gene hypothesis and animal science professor at Purdue said his work is being misrepresented by opponents of GE salmon, who don’t get any bigger than ordinary salmon. According to an article in the LA Times, Muir stated, “The data conclusively shows that there is no Trojan Gene effect as expected. The data in fact suggest that the transgene will be purged by natural selection. In other words, the risk of harm here is low.”

Monsanto introduced its sweet corn seed in 2011, and it was quickly approved for planting by the USDA since the seed’s traits were previously approved for other crops in 2005 and 2008. Today, 88 percent of all the corn in the United States is genetically modified. Roundup Ready crops also include soybeans, alfalfa, cotton, sugar beets, and canola.

With the FDA’s determination that GE salmon won’t threaten the environment, it’s likely that GE salmon will be available at grocery stores nationwide. Whole Foods and Trader Joe’s have already announced they would not sell the Frankensalmon.

LOCAL MOCO: THE COOKIE MAN

Wally “Famous” Amos lives life making cookies and bringing smiles to alight the hearts of anyone he encounters.

TEXTBY BEAU FLEMISTER | IMAGE BY JOHN

HOOK

“I haven’t grown up yet,” says Wally “Famous” Amos. “Growing up has no meaning. Grow up to what? Grown ups are people that stop having fun. They take life too seriously and forget to laugh about it. What’s the point of being serious?”

Wally’s got a good point. He’s got a T-shirt on that says, “Chocolate’s a vegetable!” He’s 77, looks 60, laughs like a 20 year old, and smiles like a newborn babe. Wally’s got the kind of smile that God practices in front of the mirror, and calls it doing his best “Wally.” Because sometimes, even God forgets how much sugar you added to that first flawless batch. But Wally hasn’t. Wally is The Cookie Man. But was he always?

Wally Amos was born in Tallahassee, Florida. If you’re wondering how easy that was for an African American in the 1940’s South, I’ll tell you: He got to New York City by age 12. Quite a change in scenery for a young boy, but it was there that he fell in love... with cookies, of course. His kind Aunt Della, whom Wally lived with at the time, would bake him chocolate chip cookies, a delicacy he was never granted before then. “It was an incredible experience,” says Wally. “Just watching her and realizing that she was baking cookies just for me. The love that she put into a gift like that—a gift that I could taste—just to please me, there was something about that experience that was life changing.”

But the cookie man was still a boy, and would be for another 30 years. After a youth spent shining shoes, he joined the Air Force, then became a manager at Saks Fifth Avenue. When he tired of Saks, he became a gopher in the mailroom of the William Morris talent agency. But we talked about

Wally’s smile already, so it should come as no surprise that he was promoted to agent in less than a year. He represented the likes of Marvin Gaye, The Supremes, Helen Reddy, and Simon & Garfunkel. About that time, around 1970, Wally finally started baking his own cookies. He even started using them as a calling card at the agency, the most delicious of icebreakers. Wally’s cookies were so delicious, in fact, that his purpose in life seemed destined to a higher calling. He left the talent agency and opened Famous Amos Cookies in 1975, the first shop in the world to specialize solely in chocolate chip cookies.

His label changed a few times since then, but that’s merely a footnote; the thrill is never gone for Wally. “Everything about chocolate chip cookies pleases the deepest part of me,” he says beaming. “People have a relationship with chocolate chip cookies more than any other cookie in the world because a chocolate chip cookie represents all the good things in life, like love, kindness, gentleness, feeling good. The chocolate chip cookie embodies those things.”

Sometime along the way, something extraordinary happened. Getting a taste of the islands in his Air Force days, Wally returned to Hawai‘i for good. “There’s nothing like this place,” Wally says. “I love the people, the spirit, the mana, man! There’s that gentleness, that aloha spirit that people here express for one another that you can feel, smell, and taste.” Like cookies. A chain of eight small, blissfully sweet cookies in the middle of a big blue sea.

Since then, he’s co-authored 10 books, served as the National Spokesperson for Literary Volunteers of America, and launched a foundation for child literacy in Hawai‘i called “Read It Loud.” And, of

course, he’s kept baking, his newest label called Wamos Cookies. But has the taste changed after all these years? “You can’t fool your mouth,” says Wally with a laugh. “If it tastes good, you’re gonna know it! It’s also the original recipe,” he says, with a glint in his eye.

When Wally bakes cookies, God takes notes. Not to steal his secret recipe or anything, but because that kind of unwavering passion is hard to find. That kind of continual newness Wally has for each day is hard to replicate. Like the perfect cookie; like Wally’s smile.

Find the taste that put a smile on Marvin Gaye’s face at The Sheraton Princess Kaiulani Hotel in Waikīkī or at wamoscookies.com

With a smile like that of a newborn babe, Wally “Famous” Amos continues to make people smile after nearly 40 years in the cookie business.

With a smile like that of a newborn babe, Wally “Famous” Amos continues to make people smile after nearly 40 years in the cookie business.

Sean Connelly’s A Small Area of Land addresses the way land is objectified in Hawai‘i today. “That’s contrasted with the way, traditionally, our culture treated land, which felt more of a familial relationship to it,” he says.

a Small area of land

SEAN CONNELLY“Whoever controls the land, controls the future of Hawai‘i.”

At just 28 years old, Sean Connelly can already consider himself a landowner, of a “small area,” to be exact. The 32,000 pounds of land he owns, he has molded, compacted, formed, and set on display at ii Gallery, a small space in Kaka‘ako. Connelly chose the location with intent—the gallery sits on land owned by Kamehameha Schools, the largest private landholder in the state. Much in the same way that Connelly is trying to control his own small piece of land, molding it into an unnatural form, this “architectural intervention,” as he calls it, titled A Small Area of Land, addresses the way land is objectified in Hawai‘i today. “That’s contrasted with the way, traditionally, our culture treated land, which felt more of a familial relationship to it,” he says. “Traditionally, it was cared for.”

For as long as he can remember, Connelly has been fascinated by land. Growing up, he split his time between his dad’s side in Kahalu‘u and his mom’s side in Kalihi, all at once lulled by the lush greenery of the Windward side and disenchanted by Honolulu’s ugly urban core. “When I applied for college, my essay about why I wanted to become an architect was because I wanted to make Hawai‘i a more beautiful place,” says Connelly, who holds a doctorate in architecture from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “Now, I’m less concerned with making things pretty for the sake of saving Hawai‘i in terms of its beauty because I know there are much deeper issues than just aesthetics.”

Since then, Connelly has been active in creating a more sustainable

future for Hawai‘i. While at UH, he cofounded Sustainable Saunders, a group that retrofitted Saunders Hall with more energy-efficient devices. After graduation, he worked at KYA Design Group to help develop an environmental baseline for the Hawai‘i Department of Transportation Airports Division. Now, Connelly says he is interested in issues related to environmental degradation, and specifically, how urban developments have diminished the productivity of Hawai‘i’s watersheds, the area from mountain to ocean known as the ahupua‘a. “When you look at the watershed itself on a map, all of the stream areas within it are zoned as urban or agriculture. This is really bad for the environment because we essentially destroy the function of the stream, which is to filter the rainwater draining into the ocean. This eventually creates a lot of pollution and runoff.”

Connelly believes that understanding the watershed—basically a rock with living things on it—can ultimately help us to better integrate with our environment. “The goal with architecture and building has always been to replicate nature, ever since the Greeks,” he says. “I’ve been studying a lot about geomimicry and how design can mimic geological processes. The idea behind geomimicry is that a building moves slower than biology but faster than geology, so it’s like the place we live can become this middle ground between the living and the non-living.”

These ideas, as complex as they are, come together rather simply in a mix of dirt, sand, and water. Though, as with

anything artistic or political, in which things are often not as they seem, many of the elements that make up the towering monolith that is A Small Area of Land are symbolic of something else. The broad face of the sculpture is angled ever so slightly, reflecting the angle of the moon facing the rising sun as it was on August 6, 1850, the day that the Kuleana Act, which privatized land in Hawai‘i, was signed. “My brotherin-law has a native plant nursery, and while restoring the stream there, he uncovered an ancient lo‘i terrace,” he says. “But it’s angled differently, counterintuitive to the natural flow of water.” Turns out, the angle reflected the Spring Equinox, acting like something of a compass for the ancient Hawaiians.

“I think that’s more meaningful than throwing on like a kalo decal and is something we can bring back into the way we generate forms,” says Connelly, who hopes one day to see this type of building design come to fruition with an architecture firm of his own. It’s a long road ahead before that comes to pass, but Connelly will soon be one step closer to fulfilling that vision when he attends Harvard in the fall to receive his master’s in real-estate development.

After the installation closes, the dirt and sand will be given a third life, used for an urban garden directly behind the gallery. Because as with all things, restoration and reclamation are critical components of Hawai‘i’s future.

Thorben Wuttke’s Oahu Makerspace is a collaborative community of wood and metalworkers where knowledge is shared and design is elevated.

converSation Piece

Honolulu Furniture Company and Oahu Makerspace

The most memorable piece is the conversation piece. Defined by character and outlasting vision, it begs to tell a story. Who makes it? Where does it come from? What does it represent? Designers—the creators—have always been given the responsibility to spark genuine interest.

For a woodworker conscious of his or her medium’s origins, the story begins much in advance of the design process and well into the origins of the wood itself. Thorben Wuttke, founder of Honolulu Furniture Company, has gained recognition for his company’s attention to a question we often forget to ask about conversation pieces: Where do we get our resources and how is our furniture made? His furniture is crafted with locally sourced sustainable wood, either naturally felled or reclaimed from deconstructed houses. And though koa has been the wood of choice of Hawai‘i-based crafters, Wuttke opts for monkeypod, which is the most readily available and sustainable wood source found in Hawai‘i. It’s also more durable and termite-resistant than koa.

“About 95 percent of wood is imported,” Wuttke says. “Hawai‘i is not very diverse in terms of wood for building houses, but for furniture, it is.” Wuttke credits much of his company’s sustainable philosophy to Re-use Hawaii, saying, “They got me started on the idea of building furniture from reclaimed

materials, and if it weren’t for their service of deconstruction, it would be too difficult for us to do it ourselves.” With each piece of reclaimed or repurposed wood, the process preserves the character of old wood for another generation.

Leading by example, Wuttke aims to celebrate woodworking as an artist’s trade by bringing together artisans specializing in wood and metal work at his co-op space Oahu Makerspace. To truly use what is around you, you must also recognize that people are valuable resources. The Makerspace is a collaborative community of crafters renting shared spaces from Wuttke in his Kaka‘ako warehouse, where woodworkers share knowledge and equipment with those taking design and construction to the next level. It’s the tangible reality of the idea that two heads are simply better than one. Collectively, we’re able to tell a better story.

For more information on Honolulu Furniture Company, visit honolulufurniturecompany.com.

THE MAKERS

H E iko G RE b

Artist, wood and metal sculptures

Originally from Germany, here by way of San Francisco, Heiko Greb is not a traditionally trained woodworker but instead has a background in genetics. From woodcarvings to more conceptualized pieces of metal, Greb’s creations arise from his completely self-taught talents. “I grew up on a semifarm where we made our own firewood,” says Greb, who has been at the Makerspace for just a few months now. “Eventually, skill with a chainsaw led me to think differently about wood being just a log in the garden, and I started carving. I found that I liked it and was good at it. It just fell in my direction.”

M ic H a E l PR aTT

Michael Pratt Woodworking, furniture and cabinets

One of the elder and much more experienced gentlemen in the Makerspace, Michael Pratt is a third-generation furniture and cabinet maker originally from Saratoga Springs, New York. There, he worked many years as a general contractor and gained a reputation for his styling of Victorian restoration. Pratt moved to Hawai‘i in 2009 after spending 12 years in Florida. A bad motorcycle accident caused him to seek warmer temperatures. “Going into my forty-sixth year of woodworking,” he says, “I still love what I do. Woodworking is my passion and fortunately my job.” His most recent project: sliding wall partitions for a house on O‘ahu’s North Shore.

Ma H o S H aW

Wood-and shell-inlayed jewelry boxes

Maho Shaw’s roots of woodworking go back 10 years. Her father was a carpenter, and together they built houses in Japan. Today, Shaw has taken these skills to minute proportions, working on small jewelry boxes often inlayed with wood and shell details. Shaw has worked out of Oahu Makerspace for just over a year, and you can find more of her treasures, like her koa boxes, at Nohea Gallery.

kR i ST in bR o W n

Mae Brown Furniture, furniture

Kristin Brown’s background is in business and marketing, but she has always been interested in furniture refurbishing. She approached

former co-owner of Honolulu Furniture Company Doug Gordon for a possible apprenticeship, and two years later, Brown now operates as Mae Brown Furniture from the same location she apprenticed in. “A lot of people buy materials from Re-use Hawaii,” she says. “I don’t think anyone buys new lumber. We all buy salvaged—it has a lot more character.” Currently in her workspace: lots of mahogany for a yoga studio in Kaka‘ako.

b ill R E a R don

Heavy Metal Inc, furniture

Since 1998, Bill Reardon has worked with a slew of alloys, from aluminum and stainless steel pipes to bronze and copper-nickel.

Originally from New York, Reardon got his first taste of metalwork doing sanitary pipe fittings, which he ended up in for 12 years. When he moved to Hawai‘i, he worked as a Pearl Harbor welder. Back then, creating furniture was a side project, but today, it is his forte. On welding functional art, Reardon says, “It’s a lot nicer than piping. I can do it all sitting on a bench, and the pace is different. You get to work with all types of equipment, and each job still has its challenges.” And on working in a collaborative space, Reardon affirms the upside: In front of him is a pair of sleek aluminum table legs, ready to be polished and placed with a monkeypod slab that Wuttke has been working on. “I get to work on projects and draw off almost everybody.”

R E id S H i GEMUR a

Ho‘okani Music Company, musical instruments

Reid Shigemura knows wood and sound. In his corner of the space, which he has occupied for just a few months, several inprogress ukuleles are indicative of Shigemura’s specialty in musical instrument repairs and building. His ukuleles are made of spruce and mahogany, also known as tone woods, which are more commonly used for guitars than they are for ukes. For the past 15 years, Shigemura has honed his woodworking skills first taught to him by his father, a violin and ukulele maker. After working at Harry’s Music Store for more than 13 years, Shigemura recently left to pursue his own projects, one of which is Ho‘okani Music Company.

For more information on Oahu Makerspace, visit oahumakerspace.com.

For as long as he can recall, music has been a part of Mark Koga’s life; rhythms, beats, and chords follow him like a shadow. Mark shown with vocal and acting coach James Macarthy.

the muSic inSide

Mark KogaIt’s just past 4:30 on a Tuesday afternoon in Downtown Honolulu, and Mark Koga stands in a recording room with his eyes closed. He’s wearing a faded black tank top and a pair of red khaki shorts that match his red shoes. The room is completely quiet, almost awkwardly still. Strapped across Mark’s body is an acoustic guitar, and around him sits a kick drum and a family of speakers. Breaking the silence, Mark opens his mouth and sings the tune to his latest song, belting out a few words from the chorus with special emphasis on each vowel. As the final words ring out, Mark slowly opens up his eyes and looks at his voice coach, James Macarthy, for approval. The coach nods his head.

At this point, it suddenly occurs to me just how different Mark is from the rest of his peers. When other 17-year-olds are filling their days dreaming of surfing, football, and cute girls, nearly every waking minute of Mark’s life is spent focusing on music. Rhythms, beats, and chords follow him everywhere, like a shadow. His mind is never quiet; it’s as if a symphony of potential songs are constantly simmering away inside

of him. Slowly, the rhythm mixes with the beat, the drums come alive, and chorus sprouts life. Each element thickens until a song is born. For as long as he can recall, the music has always been there.

Nearly a decade ago, Mark picked up his first instrument, the cello. “My mind has always been focused on music,” says Mark. “Even when I was 4 years old, I started playing the cello. At first, like any kid, I wasn’t into taking music lessons, but then I fell in love with it.” By the time he was 11, Mark’s interest had turned from classical to modern. He began showing interest in the bass guitar, and through a fortuitous string of events, Mark was introduced to the local punk scene in Honolulu via the band 86 List’s lead singer Josh Hancock, who agreed to show Mark a few chords.

“Josh sat down with Mark for a few sessions, and he picked it up really fast,” recalls Mark’s father, John. “The next thing I know, Josh is calling me up and asking if it’s okay if Mark fills in at one of their shows. I was sort of shocked because he just learned to play the bass, but now a

punk band wants him to play in one of their shows. Not to mention the show was gonna go on until late, and it was a school night, and he was only 12. But I talked to my wife and it seemed like Mark, who had always gravitated towards music, had a real opportunity to be a part of something that he was passionate about, so we said yes.”

According to Josh, the speed in which Mark picked up the bass was baffling. “Not long after teaching him a few chords on the bass, he was subbing in for our bass player. He was only 12 or 13 at the time, and he was playing with us at all these shows. We even opened up for Bad Brains together. How many 13-year-old kids are on stage opening up for an iconic punk band like Bad Brains?”

Mark had become immersed in the punk scene in Honolulu, and whether he knew it or not at the time, his life had just changed. Music was his true north and would guide him forward. But as Mark moved into the depths of his teenage years, he began feeling that something was amiss inside of him. Although it felt impossible to pinpoint, he knew that

something seemed misaligned in his head. His passion for music had never been stronger, but his ability to navigate himself through everyday situations was waning.

After struggling to fit in with his classmates, Mark jumped around to different schools on the island. Eventually finding the interactions unbearable, Mark was pulled from school by his parents, and he was later diagnosed with having Asperger’s syndrome, a mild form of autism that makes it difficult for people to navigate social situations.

“I had felt that there was something wrong with me by the time I entered the eighth grade. I wasn’t sure what it was, but the doctors said it was OCD and ADD. It wasn’t until I watched a movie about a pro surfer, Clay Marzo, who had Asperger’s, that it really hit me. He was describing it, and I was like, ‘That’s exactly what I have… that’s exactly how I feel.’” The doctors later confirmed Mark’s self-diagnosis and he began taking medicine to combat the effects. Still, Mark says he continues to struggle in social situations. “A lot of people think that

when you have Asperger’s, it means you don’t want to be social. That couldn’t be further from the truth. I really want to be social, but it’s not easy for me.”

But while Mark speaks openly about his struggles interacting with others, he doesn’t want Asperger’s to define him. That’s not who he is. Music is who he is. And when he’s on stage playing, his angst washes away with every chord he strikes and every note he sings.

Currently, Mark has his own band, slightly reminiscent of Green Day and aptly dubbed Koga, and has been playing shows throughout the city. “When I get on stage now and start playing, I don’t feel awkward at all. It all sort of just goes away. But when I have to interact with the crowd, it becomes a lot more difficult for sure. I’m working on that. My voice coach is also an acting coach and he’s teaching me how to interact on stage with the crowd. It’s all acting, I guess.”

Mark is adamant that no matter what happens, music will be a constant in his life. In fact, Mark has recently begun trying to wean himself off his medicine and is

now even questioning the validity of his diagnosis in the first place. (This comes, interestingly enough, with American Psychiatric Association’s decision to remove Asperger’s syndrome from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Psychiatric Disorders.) “I want to get off the medicine,” Mark says, with newfound clarity. “I’m sick of it making me feel so numb.”

In the coming months, Mark is set to release his first album and when he talks about it, his eyes light up. “I can’t imagine being in a situation where I wasn’t playing music all the time. It’s not like I can stop. I really couldn’t even if I wanted to. It’s a part of me, and it always will be. It’s who I am.”

Musical mentors like Josh Hancock of the 86 List have helped Mark cope with what doctors diagnosed at the time as Asperger’s syndrome.

Indigenous peoples are becoming increasingly involved in the conversation of climate change and thus, in ways for Hawai‘i to achieve energy independence.

S in K or S wim

the water S will ri S e , une Q uall Y.TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Regarding climate change, there has been a muddling of two primary issues by many critics: the first being that climate change is real and policy will have to be developed to react to the human cost of changing environments, the second that maybe we should do something about it by developing new forms of energy. This is a developing conversation being held on global transactional stages, in classrooms, and increasingly, in the arts. What has changed in the 21st century is that indigenous peoples have a voice in the discussion, and are offering real, and at times contentious, solutions about how to react to rising waters.

You don’t need an article in a magazine to tell you that climate change is real, and that there are consequences to it. Political scientists since the First World War have argued that the great conflicts of the globe have, and will continue to be, fights over essential resources such as petroleum.

Since 1988, Station ALOHA, a research buoy and base north of O‘ahu, has been collecting data. What marine scientists are finding is alarming. In just 22 years, Station ALOHA indicates that sea surface temperature is rising, that the ocean is getting saltier and more acidic, and that flow from the island’s streams is down. Colder waters in the ocean hold more carbon dioxide, and there’s less cold water. The natural system is being affected at the base of the food chain, where the terapod shells of zooplankton are corroding.

The trade winds that have brought water to the Pali are changing too; clouds are shallowing, delivering less rain in the upper watershed, decreasing 6 percent per decade over the last several decades. According to marine scientists, wet areas

are going to get wetter, and dry areas are going to get dryer, as we have intensified the water cycle. We can expect more episodic heat events during the summer, which will spike demand on emergency facilities as we try to escape the oppressive hotness by cranking up the AC, causing longer daily draws on the electrical grid. The Pacific is due to experience more hurricanes (of which we’re apparently overdue), and more intense storms.

More bad news: Hawai‘i is the most oil-dependent state in the United States. Annually, residents pay nearly seven billion dollars for petroleum-based energy. Though there was much talk at the federal level about making climate change a priority, there has been little action. In January, President Obama delivered his second inaugural address and said, “Some may still deny the overwhelming judgment of science, but none can avoid the devastating impact of raging fires and crippling drought and more powerful storms.” So it was a shocker when the 2013 budget came in silent on what Obama will do to aggressively reduce

carbon pollution by the biggest emitters like power plants and automobiles. Regarding dealing appropriately with the effects of climate change, both in human resources and in making strident moves towards energy independence, we are, it appears, on our own.

Part of the chill on intense action at the federal level has to do with advancements in hydraulic fracturing, known as “fracking,” in which large amounts of fresh water combined with sand and other substances are blasted at high pressure down wells drilled into deep layers of shale to get oil. The development of fracking in continental America means that the United States will likely have oil resources for several decades into the future. These conversations made their way to Hawai‘i, where several legislators pushed bills and hearings to discuss fracking, which had many advocates scratching their heads. “Aloha, legislative geniuses, there’s no oil under the Hawaiian Islands,” says native Hawaiian attorney Mililani Trask.

A little good news: Hawai‘i is slowly becoming more efficient as annual oil consumption is going down. Modeled largely after California’s lofty ambitions, Hawai‘i is one of 23 states to commit to reducing greenhouse gases. Acts have been passed in recent years for tax credits, portfolio standards, and a fee on imported energy. Unfortunately, those fees have been siphoned off to the state general fund. By 2030, Hawai’i has the goal to attain 40 percent of energy consumption from renewable sources such as wind, solar, and geothermal. There has been some political advancement. Wind energy is proliferating across the islands. In 2009, a federal and state tax incentive for solar panels caused a number of businesses to install dark glass on the roofs of homes across the island chain, most being legitimate, and some, fly-bynight operations bent on cashing in on the green bubble. It is the debate over geothermal, however, that has become the topic of much friction.

CLIMATE REFUGEES

The State of Hawai‘i has a model for what may happen when the waters rise:

Micronesia. The waters of the central Pacific, due to scientific forces too complicated to discuss in this article, are rising at a greater rate than in other parts of the planet, which has led to an increase in the high tides and watermarks for many islands there. And already, in the confederated states of Micronesia, indigenous populations lost much of their land, and by extension, their culture, after nuclear testing in the Pacific; the sort of history that has peace activists getting wild-eyed and yelling at television screens. This loss of culture has been exacerbated by climate change.

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Professor Tarcisius Kabutaulaka, Ph.D., has been primarily interested in those human, cultural stories of climate change.

In April 2013, he spoke to Hawaii Public Radio about possible change to the term “climate crisis” regarding what his countrymen are facing. “Climate change is a reality that will give rise to migration,” Kabutaulaka explains. “Both within countries and without countries. Thus far, it’s been within countries in Micronesia, from places like the Caroline Islands to Bougainville. Migrations out of the Pacific have been happening as a result of socio-economic issues. Outmigration results in people moving to urban centers, former territories, or, here in Hawai‘i.” This is happening right now. The President of Kiribati has been making some stunning speeches recently, explaining that if his people are to leave their flooding homeland, they must do so with dignity.

Swap “out-migration” for “refugee” and you have a nearly identical sociological model for the displacement that is caused by war: that of a people being pushed off of a homeland because of the ravages in the countryside; families and individuals leaving for urban centers hoping to find work, services, and a viable future. Like the way that refugees from Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia were forced to flee devastated homelands in the 1960s and 1970s, creating an Indochinese diaspora across the Western world, just slower. The threat is less that indigenous peoples will cease to live, but that centuries of cultural development will be absorbed into a western Americanized monoculture. Those who don’t succeed

risk ending up homeless and jobless. It is completely appropriate to be freaked out by all of this. In Hawai‘i, it means the alteration, and arguably the destruction, of cultural activities near the shore. That is a lot of culture to drown. All this bad news, of which the vast majority of us are incapable of having any control over, can make even the most ardent of advocates want to respond by taking a nap.

The response from students has been, in large part, poetic. In the spring of 2013, a conference called Waves of Change, organized by poet and Ph.D. candidate Craig Santos Perez and others at the University of Hawai‘i, attempted to tackle both the scientific and humanistic challenges facing indigenous peoples of the Pacific. It was a gorgeous usualsuspects list of potluck peacenik activists, the type of students that would have ended up on Nixon’s COINTELPRO watch list in the 1960s, or a no-fly list in the early 2000s. Over drinks and an organic potluck, organizers coined the term “climate colonialism,” and chanted amongst themselves: “Remember. Recommit. Resist.”

H EAT, W ATER , AND P OWER

The voice of indigenous peoples has been moving toward the center of the ecological debate in recent decades. Indigenous scholars and academics offer differing perspectives on environmentalism, which in Hawai‘i has, at times, been on the opposite side of the aisle from those advocating for Native Hawaiian rights.

Some scholars are discussing the cultural ramifications of energy independence primarily by looking to the past. Native Hawaiian scholar Kalei Nuuhiwa recently discussed her research into belief systems regarding Akua and Pele in particular at a symposium in April 2013. Her work has not been limited to the chants, which were dutifully recorded throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but extended to the discussions that Hawaiians had in Hawaiian language newspapers that once flourished a century ago. “The two things that geothermal require are heat and water,” she said in speech that alternated between Hawaiian, Pidgin, and academic English.

Native Hawaiian attorney Mililani

has been an outspoken proponent for responsible clean energy use; that is, evaluating what resources are available and maximizing their efficiency.

Trask

“Wherever she travels, things grow,” Nuuhiwa explains of Pele. “There is a whole episode in which we can expect Pele to move in her activities. It has to do with the flow. She must continue to make earth. As long as the earth is hot, where you see heat, that is her place. If you put a house there, she will consume it.” She went on to describe a chant that delineates the boundary of Pele, beginning on Hawai‘i Island in Ka‘u and ending at the sea in Puna. “That is her realm. As long as we allow her to do her thing there, we’re good. If we go into that realm, we are crossing the boundary of kanawai [law].”

Innnovations Development Group (IDG) is a corporation that is claiming to let Pele do her thing while providing firm energy, the type that is more reliable and non-dependent on fickle sunlight or wind power. There has been a single geothermal power plant on Hawai‘i Island since 1993, run by Puna Geothermal Ventures. That plant delivers up to 30 megawatts of firm, renewable energy to Hawaii Electric Light Company for distribution to Hawai‘i Island customers, providing nearly 20 percent of Big Island’s electricity needs. It is the only commercial geothermal power plant in the state. IDG would like to create another plant, using what its Indigenous and Community Advisor Mililani Trask calls a “native-to-native” business model. IDG’s commercial, which could be seen replaying during breaks of the recent Merrie Monarch hula competition and celebration, shows the text “culturally appropriate, socially responsible, economically equitable,” while prominent Hawaiian cultural advocates voice their support for the project.

The Trask family has a backstory familiar to most residents of Hawai‘i. The Trasks have been at the forefront of Native Hawaiian advocacy from well before statehood through Hawai‘i’s era of McCarthyism, during which several family members were red-baited for discussing the functional equality of Hawaiians as individuals and as a people. Mililani Trask is often introduced by way of her sister, Haunani Kay-Trask, whose scholarly critique of militarism and tourism has influenced countless

activists over the last several decades. A brief digression: Whatever one thinks of the complexity of Haunani’s advocacy, the depth of her work outside of strict advocacy cannot be denied. As a poet, her work will live on in the future, equaled by Carolyn Forché and Pablo Neruda for the gorgeous lyric connections between the personal and the political; their humanism overpowering the overwrought analysis of the present; to live as long as there is a reason to recite prose regarding hegemonic power in the Pacific.

Mililani is one of the lawyers of the family. I speak with her on the lanai of a home above the Nu‘uanu cemetery that IDG uses as its corporate headquarters, with Honolulu spread out under a tropical sky before us. As the former Vice Chair for Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization based out of The Hague, Netherlands, she has argued for fundamental human rights and indigenous self-determination with some of the most articulate peace and justice advocates in the world. She has studied with Mother Teresa. She has represented Native Hawaiian political groups since the 1980s. She keeps her shades on for our interview.

Judgments as to whether Mililani Trask is a saint, or, as has been said of her recent advocacy for the Public Land Development Corporation, something else entirely, are beyond this article. What is certain is that she is a lawyer. “I was a human rights advocate, not a businesswoman,” she explains. “We have the best opportunity of nearly anywhere in the world to become energy selfsufficient. The approach thus far has been American, continental,” Trask says. “We don’t need billions of dollars for an undersea cable. Moloka‘i and Lana‘i could be independently served, and not subservient to O‘ahu’s energy needs. We know how to do it.”

In making the ideological connection between electrical power and sociopolitical power, Trask makes some surprising statements: “We have seen more movement out of the military than out of the state in terms of renewable energy. That’s because they realize that energy is a matter of national security.

There is no real strategic plan in the state regarding energy. There is no chapter discussing how to make this happen in the law.

“Go back 25 years, we were excited about phones with buttons on them,” she says. “Technology has changed, and we must evolve with it. We have steps to do this. We have identified the indigenous resources available to us.” She then explains to me the fundamentals of a geothermal power plant using the table that separates us and a few coasters. A much more sophisticated explanation was created by IDG for presentations across the state and to investors. The process seems simple enough: Water goes in, creates steam heated by the earth, steam turns a turbine, and the water is put in pools to cool. We get firm power. It is a system that has been developed significantly in Italy, Iceland, and the Philippines. “When we proceed, we must find a balance between advocacy and business practices,” Trask says. “As Hawaiians, we retain the selfdetermination to manage our own resources, with our own values. The time is now.”

I make the mistake of asking Mililani Trask a question she does not like. When I ask how this advocacy fits in with relation to her previous work in peace advocacy, she was not quiet in responding, “What are you getting at?” flushing a pair of mynah birds from the ledge next to me where they were resting. “Yes, this is about peace. Peace arises out of silence. Peace also arises out of a fair allocation of resources.” I quietly look across the lanai, towards the rising sea. I get the sense that this conversation is just getting started.

Foster care can change the trajectory of a child’s life like it did for writer

chan G in G the tra J ector Y

how fo S ter care and famil Y chan G ed one Y oun G man ’S life for the B etterTEXT BY KEONI RIVERA PORTRAIT IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

the beginnings - - -

When I close my eyes and visualize some of the oldest images among the depths of my memory, I’m pulled to one of the first places that I called home—Sand Island Beach Park. It’s a foggy and fragmented recollection, but still one of the most vivid I hold of the place: There is a concrete draw guiding a runnel of grey water somewhere. I’m kneeling outside a small brick building, and I can hear the sound of a shower inside but hold no concern for it; my focus is on the soapy water sliding down the length of the gutter. This activity—this water watching—was an activity I immersed myself in every chance I got, whenever I heard the shower start up, for as long as I was allowed.

My memories of Sand Island act as a reservoir in some ways, each of the fragmented memories I’ve clung to over the years framed by water. I hold a memory of jerking upright one night, overcome by a powerful fear of the downpour that bombarded the tarp of our small, blue ridge tent, and turning to see my younger brother, mother, and father stretched out fast asleep on either side of me, unbothered by the rain. I hold another of my brother dancing on the shore near the ruins with his arms outstretched, and feeling the foamy ebb of a wave slipping between my toes, cooling them. Even in my last memory of the island, water made itself known to me, keeping the memory so clean and clear that years later, I can easily revisit

it. The memory is of the night things changed, when we would no longer call Sand Island home. I remember we were caught in the headlights of a police car and told by the man driving it to leave and never come back. The sting of the man’s words shrouded me in a sadness that left me naked to feel the sting of the thick, wet air and dewy grass that tickled the bottom of my bare feet. Soon after, I remember a drive—in whose car, I cannot say—to look at the apartment unit we would be moving into.

Homelessness is an issue I will always be connected to on some level because I lived it. Here in Hawai‘i, it is estimated that more than 40 percent of the homeless population are families with children just like we were. Of these individuals, 25 percent are thought to be children under 18, with many under the age of 6. For the first half of my life, I was a young nomad, moving from place to place, home to home, person to person, never knowing what “home” really entailed. My early life was tumultuous and unstable at times, yes, but unlike so many other children in similar situations, I was fortunate to be held inside my family, never once drifting into the unknown. Then when I was 12, I was blessed with good fortune once again: I was given a permanent and stable place of refuge when my grandmother took me

and loved me both as grandparent and foster parent.

the miDDLe

If the walls of our apartment could talk, I shudder to imagine what they would reveal. This two-bedroom unit in Palolo housing would be the first apartment my mother, brother, and I would call our own. Tucked behind its doors and windows is the space in which most of my memories regarding my mother’s struggle with drug addiction were born. The crippling nature of it took her prisoner and held my brother and me always at an arm’s length from her. We’d often see her only in passing, moving quickly out the front door to later return and enclose herself again in the deepest recess of the apartment—her bedroom. Then there were the times when a fight with her boyfriend would have them both stumbling and wrestling into the living room; furniture would be broken, glass shattered, and our screams, yells and cries would ring through the apartment, push out the windows and diffuse into the valley. Sometimes, when I’d have the courage to, I’d look down our hill to the small park across the street and see people frozen in their tracks with their heads turned, others leaning up against the fence with their fingers laced between the chain links, all eyes glued to our house imbibing the dramatic chaos of our domestic spectacle.

Between the ages of 5 and 12, I shuffled between family members six times. The last move would happen halfway through seventh grade when my brother and I were taken to live with my grandmother. We were staying at my father’s in Kāne‘ohe when my grandmother called to have us move back to Palolo, where she lived just a few buildings down from my mother. “I felt that I could take better care of you folks,” my grandmother recalls, “and the bottom line is I wanted you guys with me because I love you.” I remember my brother and I climbed into her white Nissan Sentra, he in the backseat, I in the front, with heavy hearts. As we drove down the H-3, I remember lethargically watching my

grandmother’s hand caress the steering wheel, like I always did, when she turned to us and said, “I made baked spaghetti.” With those words, I could feel some of my unhappiness fall away. I already felt better.

The move with my grandmother would become our first taste of what stable and good living was like, and for both my brother me, it was a strange and foreign routine to transition into. Having our clothes washed and meals prepared every day would often leave us feeling uncomfortable. I would also, on many an occasion, find myself suddenly drenched in surprise and awe when she remembered things like our friends’ names, television shows we liked to watch, or our favorite foods. The reality that this parental figure took an interest in and noticed our personal idiosyncrasies was, in the beginning, a baffling and strange phenomenon. In addition to caring for us and harboring the natural worries that come attached to raising children, my grandmother worked full time. When we first moved in, she worked morning and afternoon shifts at 7-Eleven, though every now and then she would have to pull a double shift and work into the night. With so much on her plate, my grandmother was always exhausted; seeing her well-rested is a sight I’ve been privy to only a handful of times. Despite her constant fatigue, however, she did whatever possible to ensure our happiness. I remember one summer, after having worked eight consecutive days, she drove us around the island on her one day off for the simple reason that she felt it was something we wanted to do. Despite this solidifying family dynamic, we lived a very much hand-to-mouth existence. To make it possible for us to even get by without going hungry, my mother would give my grandmother most of her food stamps every month. After five years at 7-Eleven, my grandmother would leave making the same pay she had coming in: minimum wage.

Since my grandmother lived in a one-bedroom unit, she let us have her bed much of the time and would sleep on the couch in the living room. Sometimes, if she worked the morning shift, we

would be woken for a minute or two by the whine of her hair curler because she would use the vanity table at the side of the bed to get ready. When she worked afternoons, she would prepare a homecooked dinner the night before and leave it in the refrigerator for us to warm up the next day. “I enjoyed taking care of you guys,” my grandmother said. “When Papa was alive and mom was little, I enjoyed caring for my family—cooking, cleaning, washing clothes—and I enjoy doing those things for you.” When my brother and I would come home from school every day, we’d look in a marble composition book my grandmother used to relay short daily messages to us that would read something like: “Dinner in fridge. Eat at dinnertime on table. Pau at 10. Love GM,” and, depending on how hungry we felt, we’d sometimes eat far earlier than we were supposed to, and never at the dinner table, always in the living room in front of the television. Old habits, I guess.

Once my grandmother became our permanent foster parent, our extremely tight financial situation was given some slack. Foster parents receive $529 per month per child from the state, but this rate has not changed since 1990 and does not translate well when one considers the rate of inflation over the last two decades. Judith Wilhoite, a family advocate at Family Programs Hawaii, in a testimony to pass legislation that would increase the monthly stipend, stated: “Per the Hawaii State Data Center, the cost of a basket of food to be prepared at home in 1990 was $24.71. In 2011, the cost for that same basket of food was $53.75. That cost alone has risen 100% while the reimbursement has not budged.” Judith Clark, executive director of Hawai‘i Youth Services Network goes on to say: “Families that generally want to provide this care are telling workers that they cannot afford to take on a foster child because of the amount that they themselves would have to contribute to the care. The issue is that the funds provided do not cover the actual costs for caring for the child.”

In our case, my grandmother, who made minimum wage at the time, would have very little money left over to buy food or other necessities after the rent and electricity were paid. Though the stipends weren’t much, when we got them, they made a substantial difference for our small family of three. Up until the introduction of foster care and the financial assistance it provided, my grandmother spent many nights worried whether there would be enough food to last the length of the month.

the enD anD noW

By the close of 2003, my brother and I had lived with my grandmother for more than six months. We had grown used to the small apartment and become accustomed to the new routine and stable lifestyle. It shielded me from the emotional perturbations that had perpetually plagued me in the past—now, I felt at peace. Before long, I would learn that luck would hold us, once again, in its good graces. Before the coming of the new year, Child Protective Services became involved, and although those words always struck fear into my brother and me whenever we heard them, within the context of our new circumstances, it would bequeath something beautiful: opportunity.

At this point in time, in the legal sense and on paper, my brother and I were still in my mother’s custody. This was also when CPS decided to take action: They traveled to my mother’s apartment with the intention to remove us immediately from her care and place us with foster families. But after learning we had been living with my grandmother, they decided it would be best if the arrangement were left untouched, and instead they began paving the avenue that would make a life living with my grandmother legally permissible. In the weeks that followed, my grandmother attended classes and workshops, met with social workers and lawyers, all the while caring for us and working full time. On January 24, 2004, my grandmother was named our legal foster parent and the three of us could live comforted by the reality that the arrangement had finally been legally bonded. From then on, truly,

my brother and I enjoyed a stable and conventional adolescence into adulthood with grandma.

***

As the Hawai‘i foster care system stands today, when a foster child reaches the age of 18, he ages out. This means he is no longer under the protection of foster care and, from that point on, is rendered ineligible for program benefits like the monthly stipend, which, for many foster families, are absolutely essential for their survival. In situations like my own, where a foster parent earns very little income and depends on this outside help, aging out of the system might mean suddenly having to support oneself, and in some cases, being forced out onto the streets. This is an unfortunate reality for young adults, who, the day they turn 18, are pushed out to face the darker side of the real world. In March 2010, Erwin Viado Celes, a young man who had been in the Hawai‘i foster system for 14 years, aged out. He left his foster family and moved between homes in Wai‘anae, Mililani and Waipahu. Six months later, he was found dead—he had hanged himself. “Each year, more than 100 children age out of the system without permanent family and connections,” says Laurie Tochiki, president and CEO of Epic Ohana, an organization designed to help foster children transition out of foster care. Nearly 2,800 children are in the Hawai‘i foster care program with up to 120 of them aging out each year.

For these reasons, I stand in the light of amazement every day at how extremely lucky I have been. As precarious and shaky as my early life was, things were always held together by an unbroken string of love— not once did I feel unloved, even when living with my mother. This affection from everyone who has ever cared for me has resulted in the life I live today, and it is a good one. I harbor no resentments against the past; instead I look back on it with a deep appreciation and gratitude because it has taught me valuable lessons about real life. Today I look to the near future, to the coming year when I’ll earn my degree from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, with nothing but zeal, happiness and an everpresent awareness of my good fortune.

Today, I continue to live with my grandmother. She is still working full

time, of course, except now she is at Walmart, earning much more than she was at 7-Eleven. We live in a twobedroom apartment not far from the old one-bedroom place. Sometimes, on my way home, I see my mother and my grandmother’s old apartments and become lost, just for a moment, in quiet nostalgia. My mother is doing very well, too. She works at a small store in the countryside called Tropical Farms and is fighting, one day at a time, for her recovery. Interestingly, our relationship has grown into one more akin to friendship than that of mother and child. Her own relationship with my grandmother, she says, “Has never been this good—ever.”

Foster care can change the trajectory of a child’s life in positive ways, as it has done with mine. The system isn’t perfect, but there are those who continue to engage in an ongoing battle for its betterment with legislation proposing improvements like extending coverage from age 18 to 21 or coordinating stipends with inflation. These endeavors are complemented by organizations like Epic Ohana, which help transition foster children into the real world. These forces seek good things for children who need them, and because I was once one of those children, I hold great admiration and gratitude for these advocates and hope to return the favor by lending my voice and shedding light on a social issue that they dedicate their lives to improving.

When I close my eyes and visualize the most significant turning point in my life, I am pulled, always, to when my grandmother became my foster parent. It’s not a foggy or fragmented memory, but vivid and clear, like a raindrop that has been pulled fresh out of the sky. It plunges me into the past where the glint of my grandmother’s bracelet and her promise of baked spaghetti still resound deeply. When I return to the present, I feel overwhelmed by gratitude because my family can finally begin mending itself back together.

The issue of ag-lot developments has grown heated, and only a mere handful engage in legitimate farming activities. There are, however, some who are doing it right, like Dave DeLeon, shown here.

S owin G the S eed S of controver SY

thou S and S of acre S of a G ricultureZ oned land are fre Q uentl Y mi S mana G ed , re S ultin G in a ri S e of G entleman farm S, million - dollar home S that ta K e advanta G e of tax credit S and other B enefit S S u PP o S edl Y re S erved for actual farmer S. de SP ite the P otential to ma K e a S i Z a B le P rofit, a few lone farmer S are cultivatin G thrivin G orchard S, not B ecau S e the law tell S them to , B ut B ecau S e it ’S the ri G ht thin G to do .

TEXT BY SARAH RUPPENTHAL IMAGES BY MATT ALVARADOEven for an urbanite, it’s easy to see the virtues of an agrarian lifestyle. Farming is a direct departure from the rat race; it’s a simpler pace of life, an opportunity to live off the land, a noble profession. All romantic notions aside, it is also incredibly hard work. But for those up to the strenuous labor and long list of chores, Hawai‘i is a field of dreams, a place where one can celebrate a bucolic lifestyle just a stone’s throw away from the accoutrements of urbanization.

Across the state, thousands of acres of land are zoned specifically for agricultural use. But don’t be too quick to envision a herd of cattle grazing lazily in lush pastures or spiky rows of pineapples stretched across an open field. Farming has taken on a new form in Hawai‘i. Of these thousands of acres, there are scores of two-acre agricultural subdivisions within designated “ag-zoned” districts.

Ostensibly, these so-called farm dwellings are intended to preserve viable agricultural uses of land in perpetuity. However, if you ask anyone familiar with local real estate, they are likely to tell you that many of these properties were clearly not designed to be large- or small-scale farming operations. Rather, they were designed to satiate the demand for developable land in Hawai‘i’s highly coveted rural areas, often allowing million-dollar homes to litter the landscape for a pittance.

Because while these ag-lot developments do afford homeowners an opportunity to don a farmer’s hat and harvest crops in their own backyards—with the added bonus of reaping a profit and enjoying state and county agricultural tax benefits—many owners of such ag-zoned lots do not farm, nor do they have any intention to do so. Ever. The

issue has become so controversial, in fact, that even bona fide farmers are being denied agriculture land-use designations that would give them tax credits and other benefits.

In Maui County in particular, the issue of ag-lot developments has reached fever pitch. Here, there are more than 1,000 residential lots within designated agricultural subdivisions. Of these properties, it is estimated that a mere handful engage in legitimate farming activities. Instead, you might find a million-dollar estate with a horse or two on land slated for agricultural use, hence the cynical term, “Gentleman’s Farm.”

It’s not as if the rules are unclear.

As explicitly stated in the Maui County Code, “The term ‘agricultural use’ shall mean lands actually put to agricultural use adhering to acceptable standards to produce crop [or] specific livestock. …

‘Actually put to agricultural use’ shall be deemed to be when crops are actually in cultivation, and farm management efforts such as weed or pruning control, plowing, including housing, fencing and water facilities for livestock and pasturing of animals are clearly evident. It does not include nor apply to areas used primarily as yard space, setbacks, or open landscape

associated with residential use planted with fruit and ornamental trees, flowers and vegetables primarily for home use.”

The regulations may be straightforward, but some argue that it’s not economically feasible—that it’s close to impossible, even—to farm on a four- or two-acre lot, especially those sited on infertile land.

As such, it’s argued that this infertile land is being incorrectly designated as agricultural, or put another way, might be more responsibly utilized. This idea, as well as the confusion resulting from the decidedly ambiguous nature of state land-use laws, has ignited a fierce debate among state and county lawmakers, and reclassifications and moratoriums on future ag-lot developments are being considered.

While the debate’s focus thus far has been squarely fixed on non-operative gentleman’s farms, there are those who are cultivating the land they live on according to the letter and spirit of the law. These few residential farmers across the state are doing it right, and for all the right reasons.

T HE H OUSE ON H AIK ū H ILL

When Dave and Hiroko DeLeon bought their home in the East Maui agricultural subdivision of Haikū Hill nearly two decades ago, they decided to give their backyard a serious makeover. The result? Some might say sour, but for the DeLeons, it’s unquestionably sweet. “My wife doesn’t have a green thumb,” says Dave. “It’s chartreuse.”

Judging from the thriving citrus grove in their one-acre backyard, he isn’t exaggerating. Hiroko is visiting family in Japan when I drop in, but the fruits of her labor are evident in her absence. As we tour the leafy expanse of the property, two dogs trail behind us, pausing to sniff at a squashed mango in the grass, tails wagging happily.

It’s hard to imagine that this dense greenery was once a fallow pineapple field that gave way to a tangled thicket of coarse shrubs and forest grass. “We literally created this from the ground up,” he says with a laugh. “The only problem now is that we are running out of room.”

Instead of a swimming pool or

“These trees are like my children. I’ve known them all since they were seedlings,” says Dave DeLeon, whose one-acre backyard now brims with fresh fruits galore.

and