THE

ISSUE

Sunday: Kahana Kalama Incase of Emergency: Moses Aipa

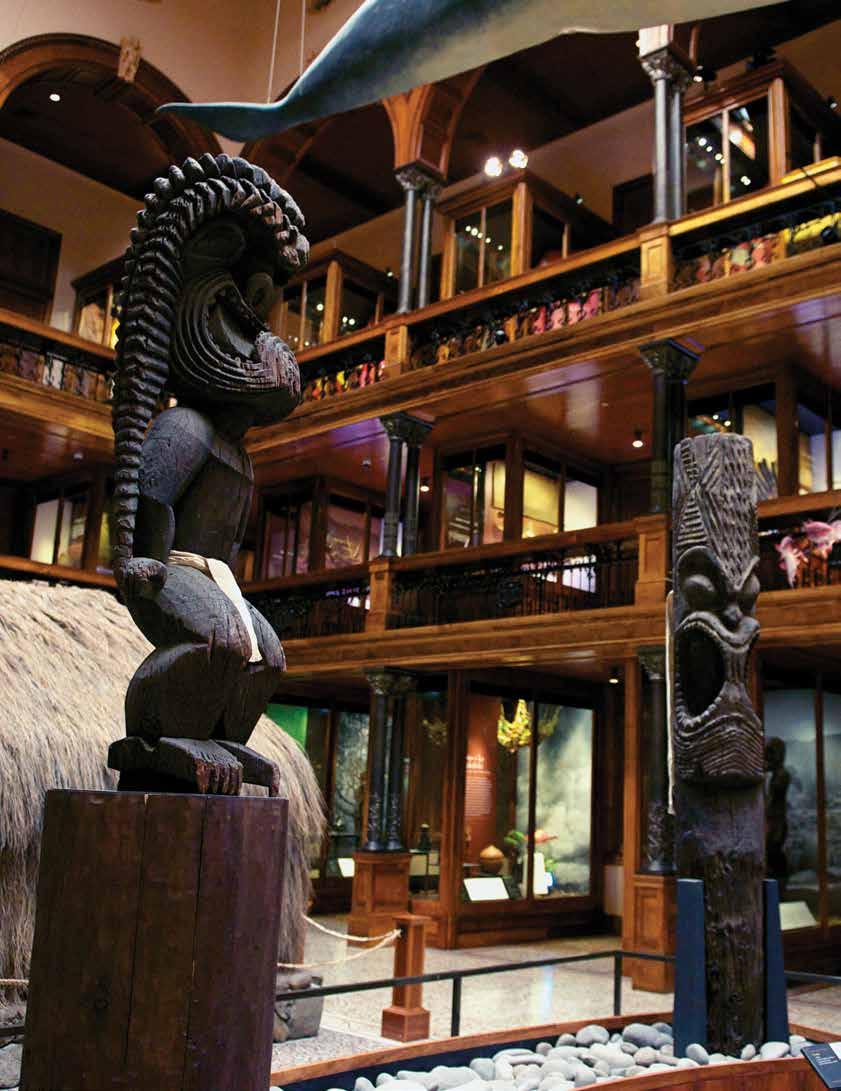

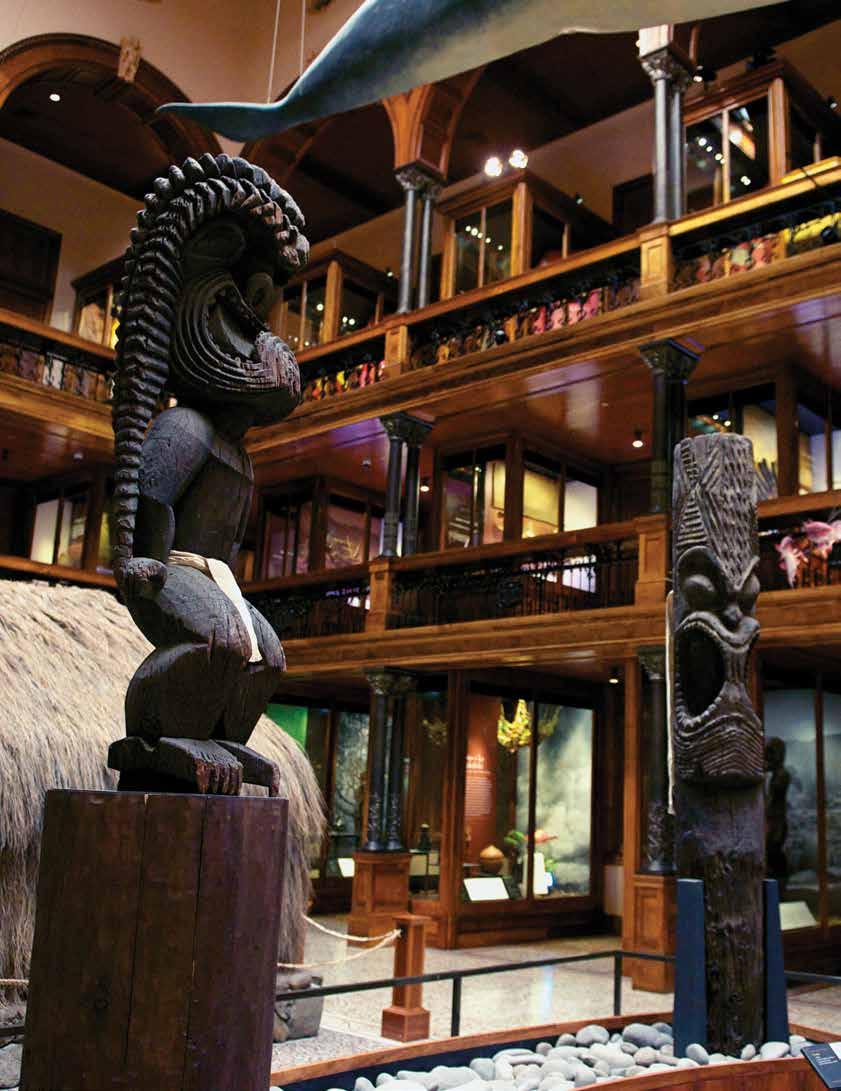

Last Statues of Kū

Local

Lanai and

Tabura WINTER DISPLAY UNTIL FEBRUARY 1, 2014

Homecoming

Aloha

The

Two

Boys:

Adam

An AvAtA r WA lks into A Whiskey B A r | 30

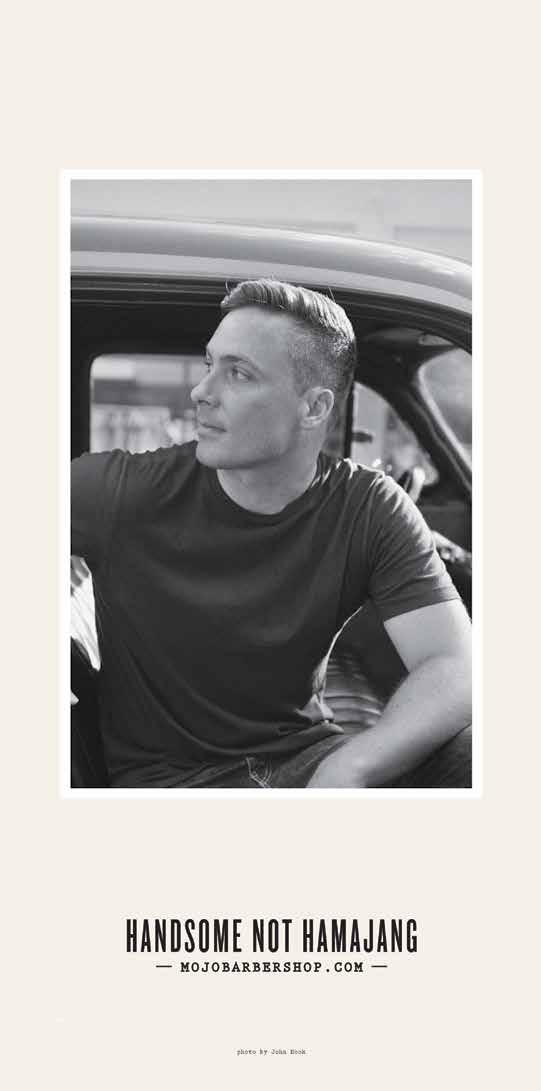

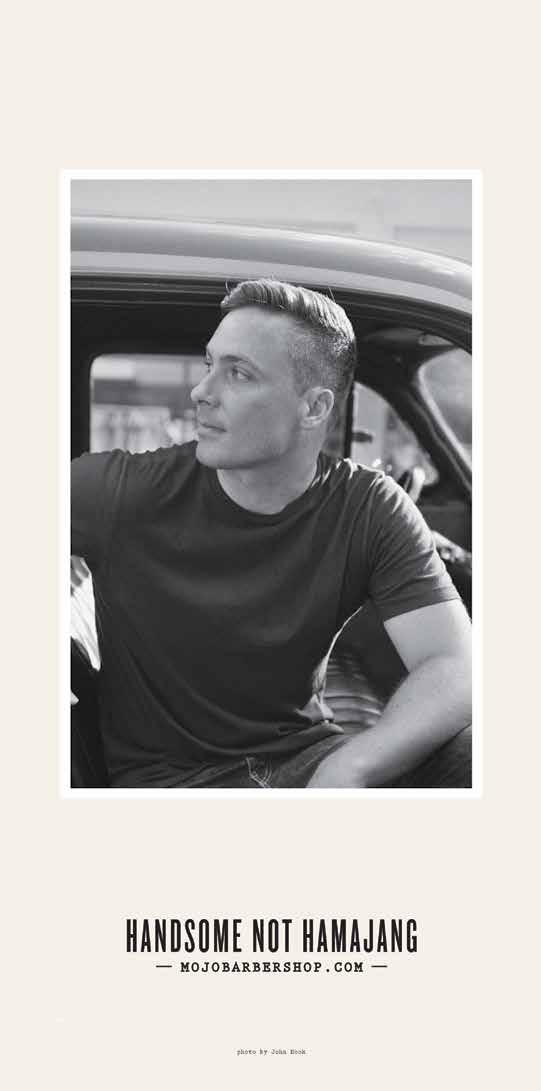

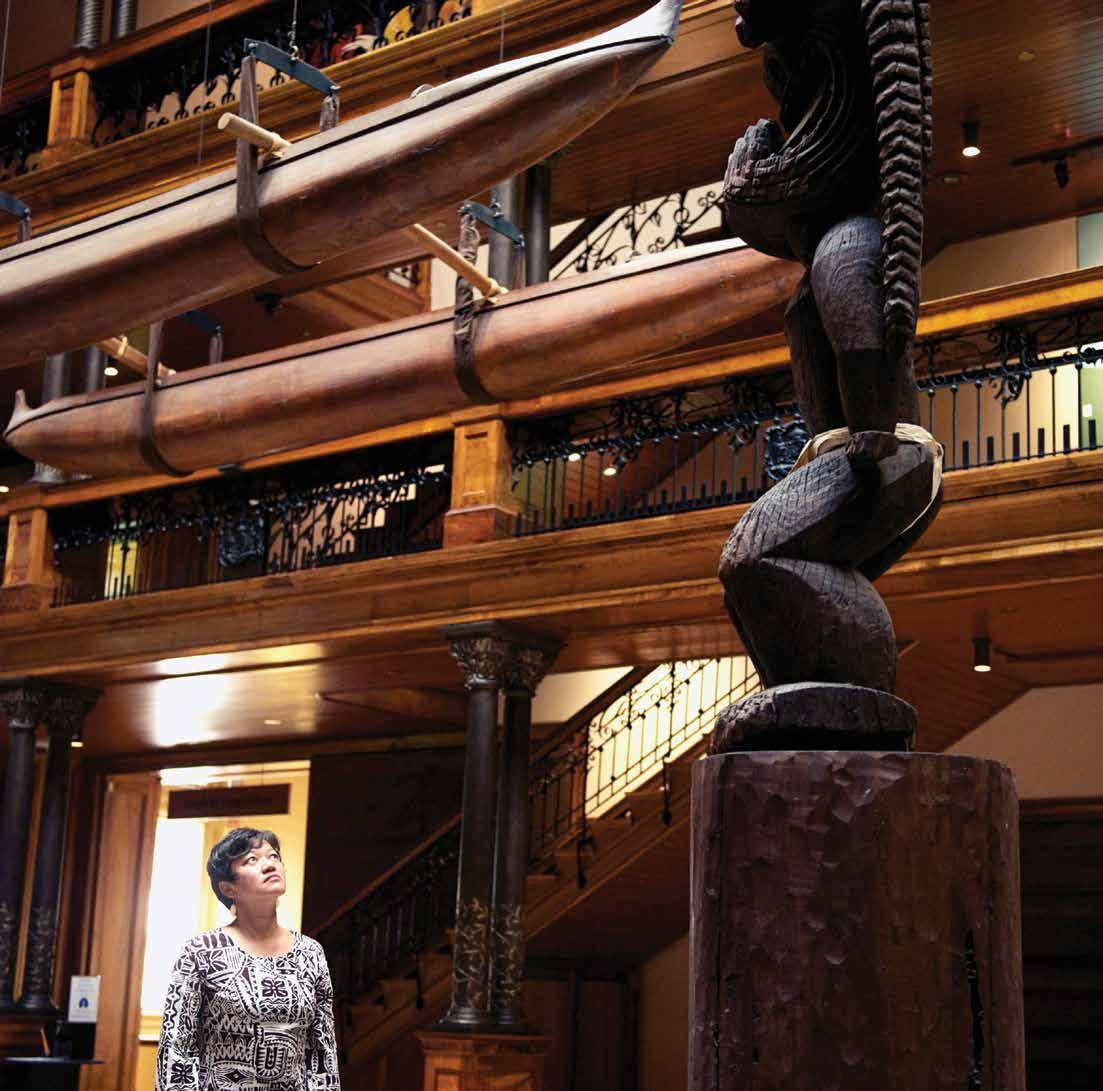

Kahana Kalama, founder of lifestyle boutique

Aloha Sunday, brings a little aloha to San Diego. Photography by John Hook.

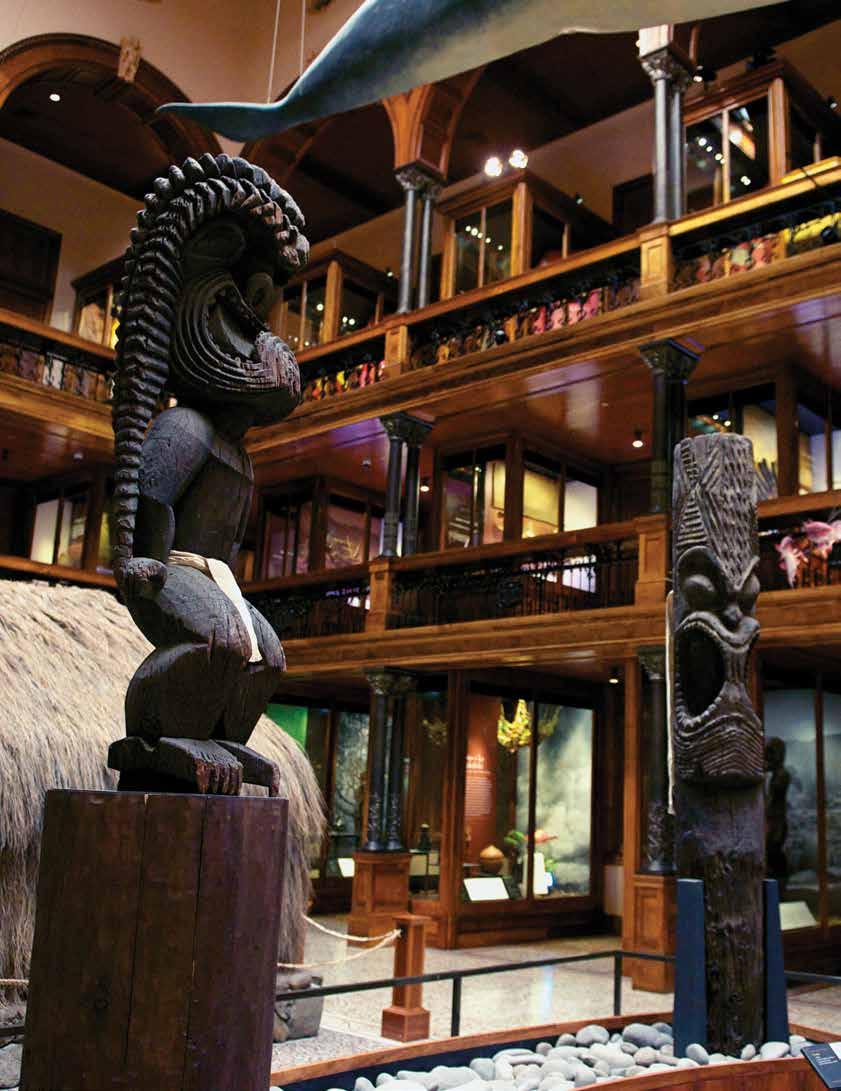

stA nding o ut from the CroW d | 34

Ryan Kingman, co-founder and VP of marketing at Stance, stands out from the crowd with uncommon threads. Photography by John Hook.

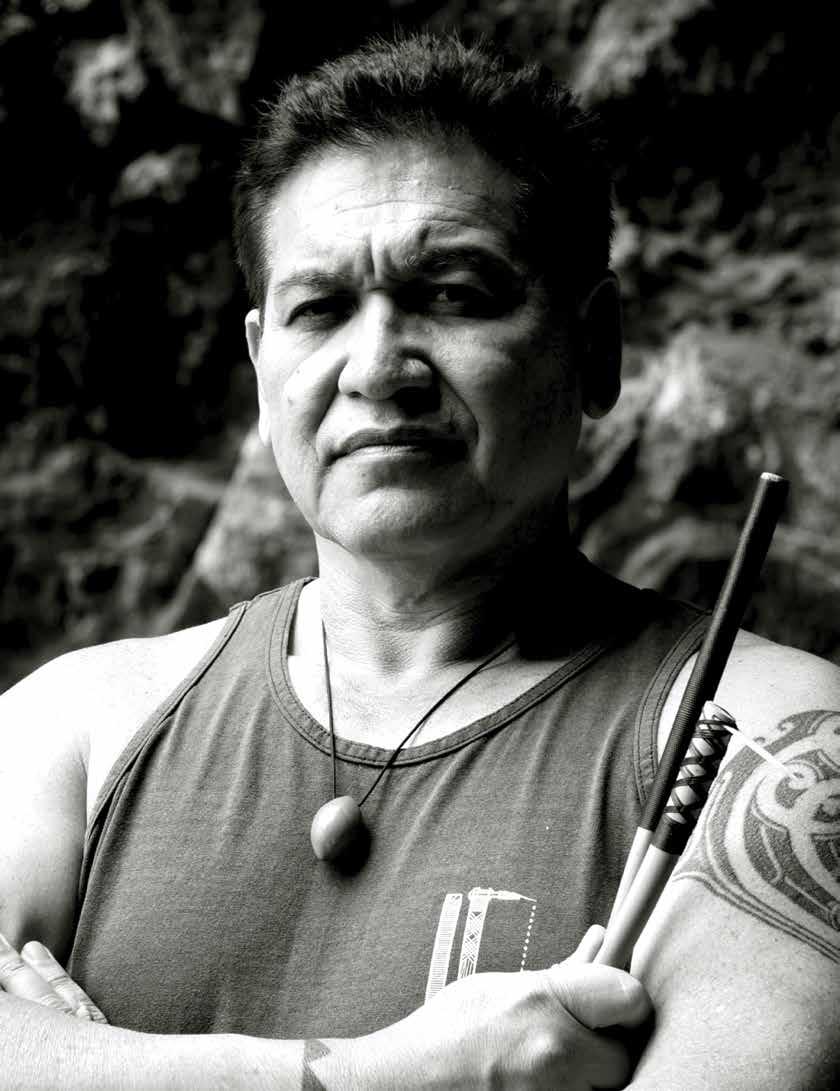

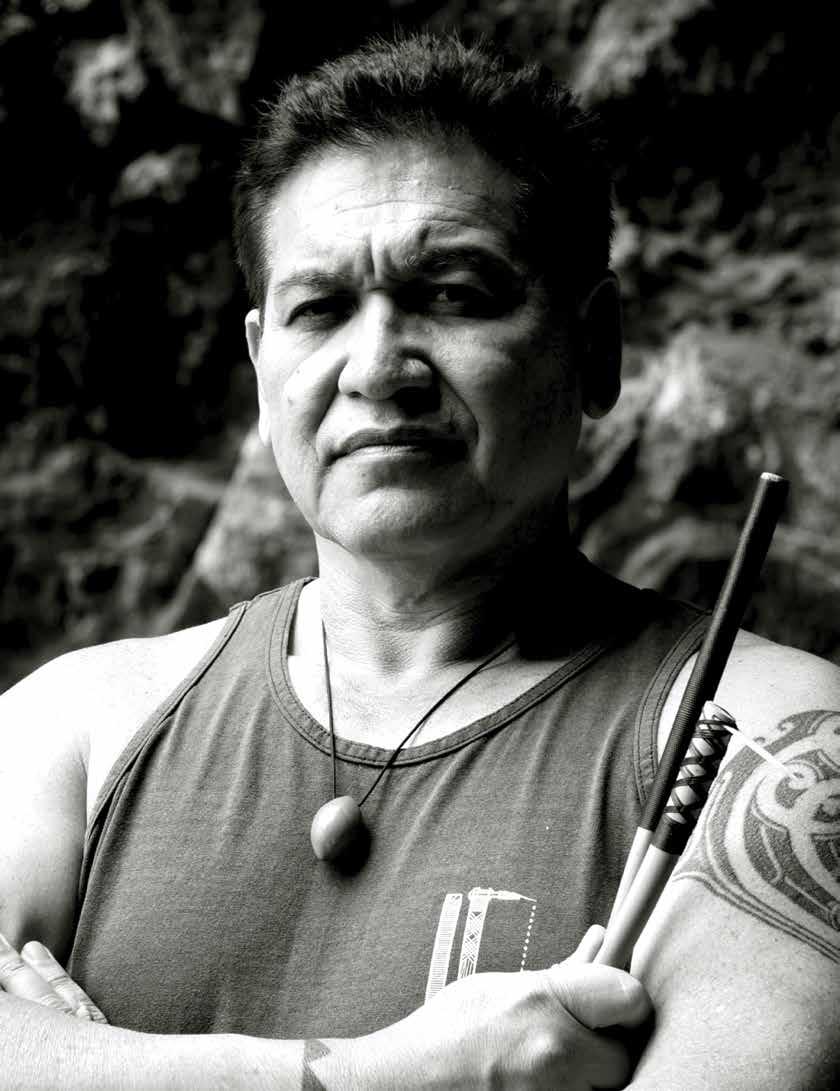

i nC A se of e mergen C y | 38

Moses Aipa, senior creative brand director of Incase, ensures a better experience through good design. Photography by Geoff Mau.

t he sW eet l ife | 40

Jay Kinimaka Muse, owner of Lulu Cake Boutique in New York, whips up sweet delights in celebration of love, life, and everything that comes with it. Photography by Bailey Roberts.

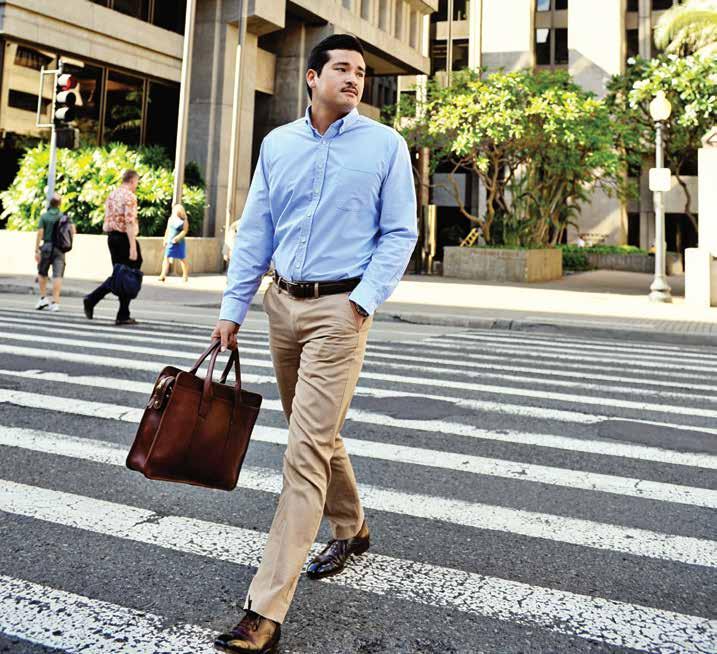

tWo lo CA l Boys | 44

Aloha Plate’s spectacular win on The Great Food Truck Race was like something out of a Hollywood movie. Editor Lisa Yamada recounts how the astonishing real-life experiences of brothers Adam and Grant “Lanai” Tabura got them there.

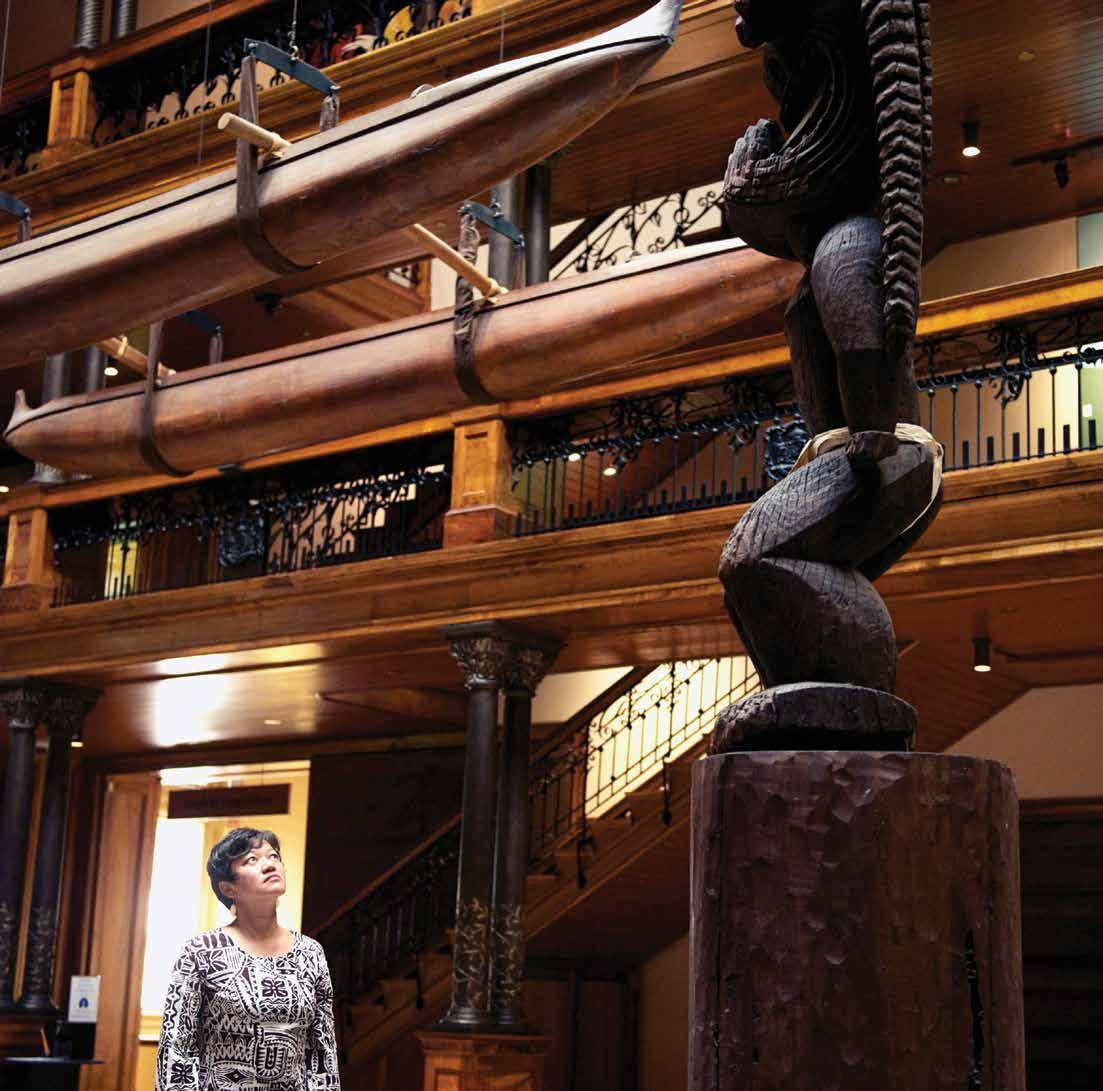

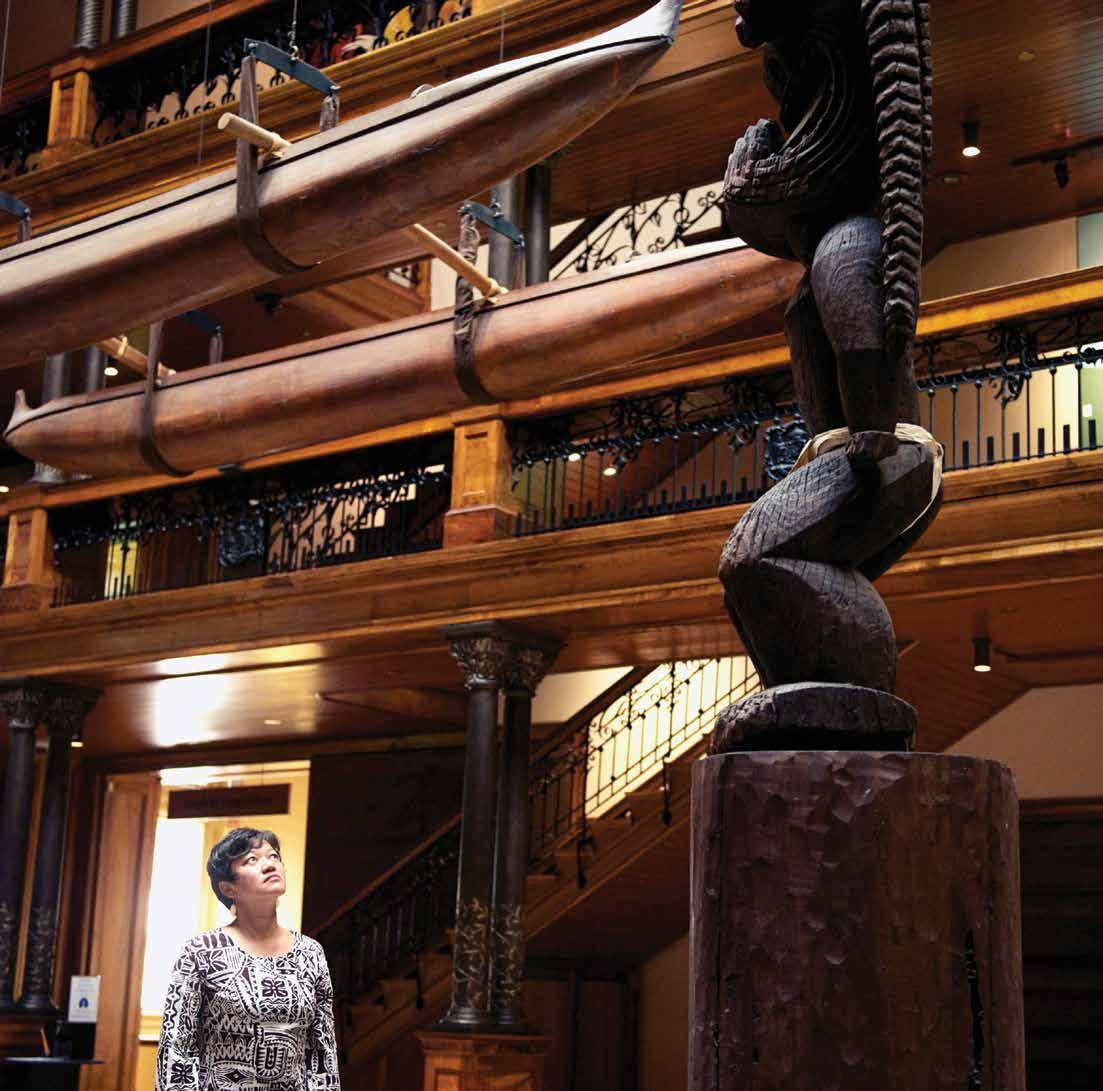

t he lA st stAtues of ku | 50

Three years after the last remaining Kū statues made their appearance at Bishop Museum, the community remains engaged in a dialogue regarding art, religion, and reverence for history. Sonny Ganaden explains how their return may be inevitable.

f ourteen m onths of stories | 56

After spending fourteen months traveling through fifteen countries, Tina Grandinetti returns home to the familiar shores of Honolulu, and reflects on the stories she heard along the way.

tA ke m e to your l e A der | 64

A space-age fashion editorial styled by Aly Ishikuni and photographed by Haren Soril.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES 6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

PAGE 44

Adam and Lanai Tabura overlook Manele Bay, where Adam saved a man from drowning, sparking a chain reaction of events that would send the brothers on a culinary journey across the nation.

Artist Jared Yamanuha works on cuttings for his first solo show, which explores the theme of omiyage, the tradition of bringing gifts back home for family and friends from one’s travels.

editor ’s letter

Contri B utors

m A sthe A d letters to the editor

W h At the flu X?! | 19

HOMELESSNESS

lo CA l mo Co | 23

ALOHA STADIUM

TAKES FLIGHT

FLUXFILES : A rt | 26

JARED YAMANUHA in flu X

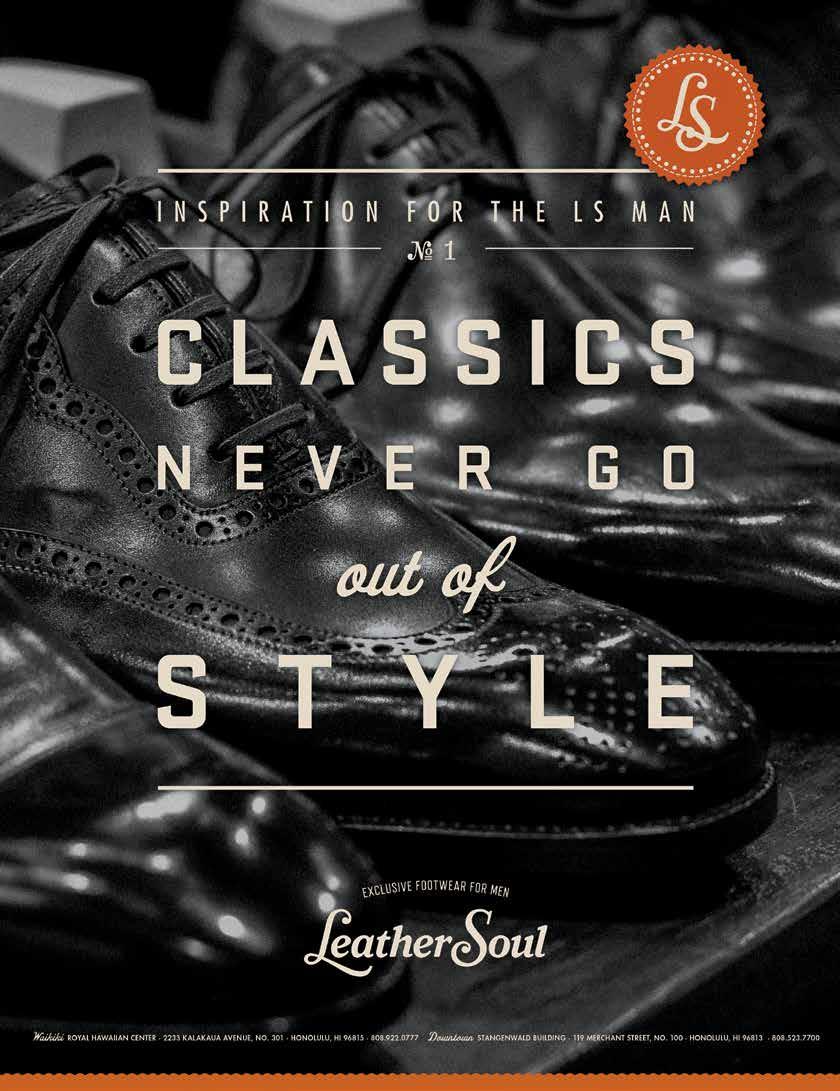

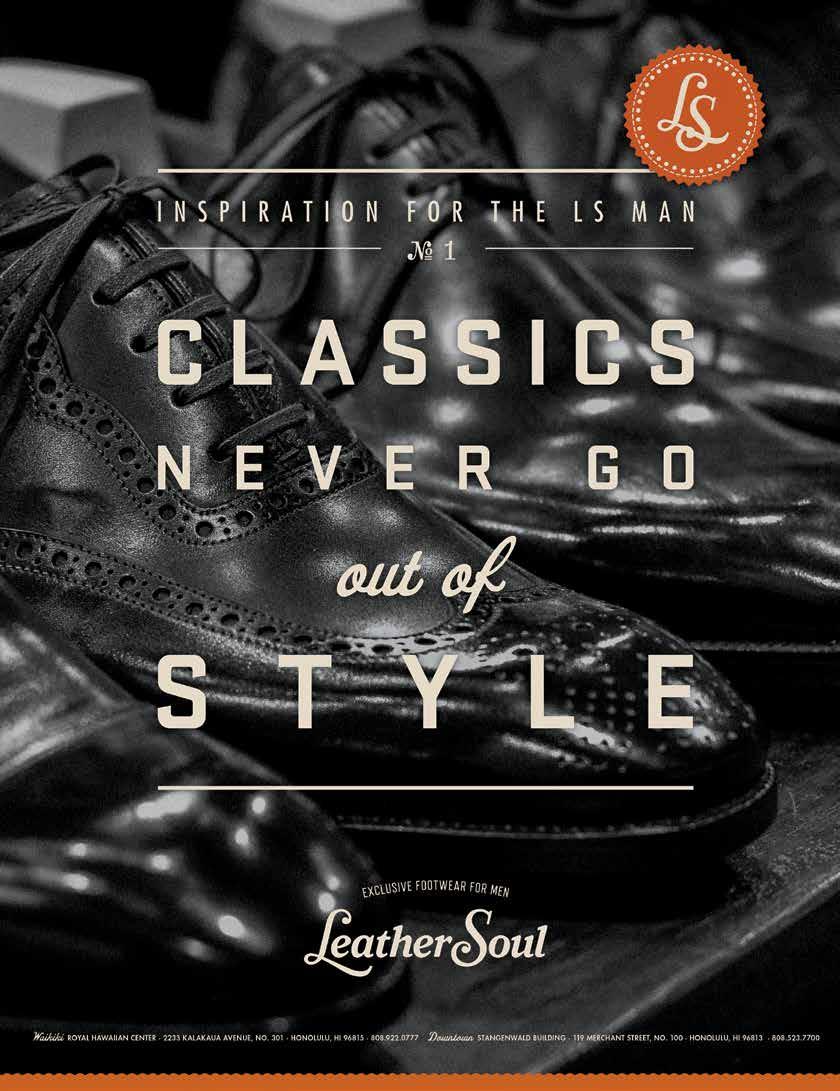

FASHION : le Ather soul style | 71 THE OXFORD SHIRT

trend | 74 ESSENTIAL ALOHA

the W hiskey thief | 76

l A st look | 80

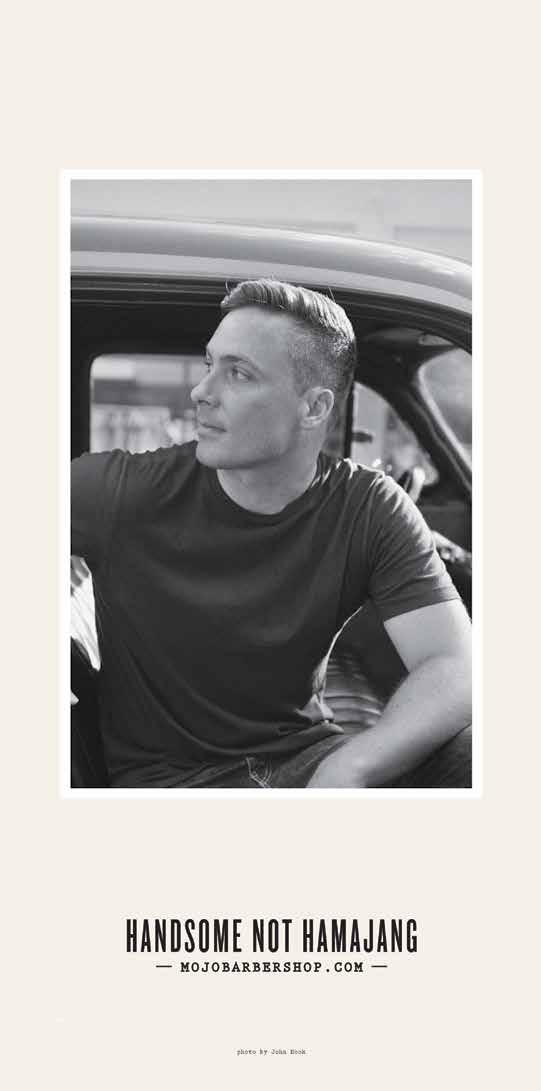

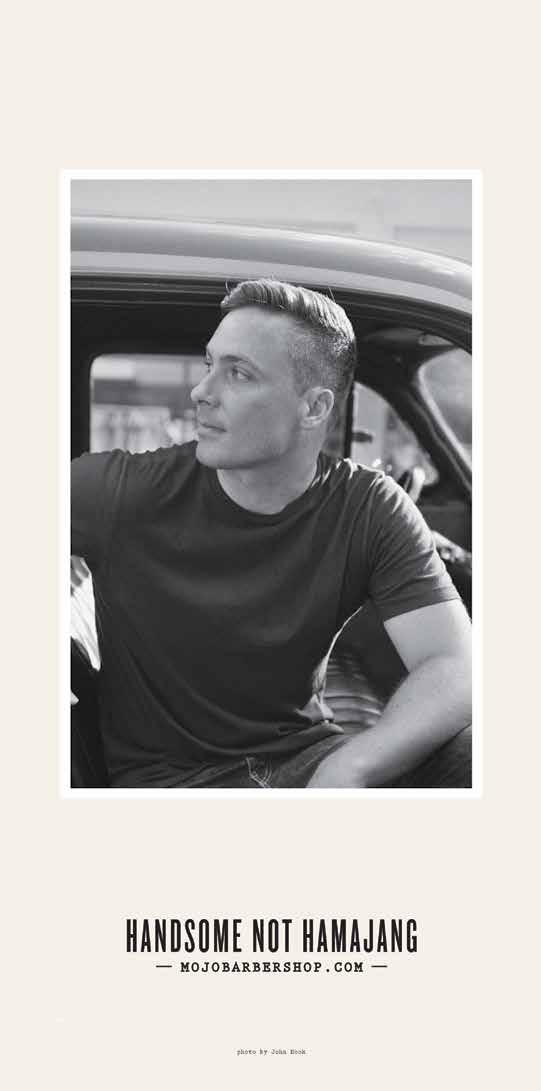

TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS 8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

PAGE 26

ON THE COVER

Photographer John Hook spent the day with Kahana Kalama to capture this shot of the Kailua-born owner of Aloha Sunday, a lifestyle brand and boutique based in San Diego. Read about how Kahana’s experiences growing up on the Eastside continue to inspire him today on page 30.

WIN THIS TABLE

All you have to do is purchase an annual subscription to FLUX Hawaii, and you will be entered in a drawing to win this side table, handcrafted by Dae W. Son out of monkeypod wood and reclaimed metal. The table also features laser-engraved artwork by Lucky Olelo. Retail value: $700.

DRAWING DETAILS:

Deadline to subscribe is January 13, 2014. Each subscription purchased will count as one entry. You may enter as many times as you like. All current subscribers will be automatically entered. Any additional subscriptions purchased will count as additional entries.

To subscribe: fluxhawaii.com/subscribe Enter “wood” in the promo code to receive 62% off an annual subscription!

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FLUXHAWAII.COM 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

We may be a quarterly, but W e’re bringing stories all the time online. Stay current on arts and culture with us at: website: fluxhawaii.com facebook: /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii instagram @fluxhawaii

This issue celebrates anyone who has ever left Hawai‘i, repatriating and welcoming them home within the pages of this magazine.

If you’ve ever spent an extended amount of time away from Hawai‘i, you’ll understand the burden of the many who have left, who long to return home—to the stillness of our islands, the beauty of our people, the comforts of our food—but who remain abroad for the sake of opportunity, economical, professional, or otherwise.

Jay Kinimaka Muse, a Kamehameha graduate who has lived in New York for more than eighteen years, commented on a recent visit to Honolulu: “I felt like a foreigner in Hawai‘i. Although I knew I belonged and I’m from there, I was hurt at the disconnect I had with the island.” On his trip back home, however, the bakery owner was “awakened by the aloha spirit” more than he had ever been before, prompting thoughts of a return, someday, back to the islands.

From those who live elsewhere to those who have traveled around the world—whether for a two-month culinary competition in the national spotlight or a fourteen-month sojourn of self-discovery—Hawai‘i inspires everything they do, the spirit of aloha emanating whether they are conscious of it or not. No matter where one goes in the world, people everywhere are fascinated with Hawai‘i. From Minnesota to Myanmar, faces alight in smiles after hearing one is from Hawai‘i; complete strangers gush about how much they love the place we are so lucky to call home despite their never having been there (maybe they saw a postcard depicting Waikīkī Beach or remember a scene from Blue Hawaii).

It’s undeniable: Hawai‘i is a special place. We will continue to advocate for preserving the Hawai‘i the world knows and loves while seeking to create an innovative Hawai‘i for the future, a Hawai‘i to come home to.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor

| EDITOR'S LETTER

FLUX HAWAII

Jason Cutinella PUBLISHER

Lisa Yamada EDITOR

Ara Laylo CREATIVE DIRECTOR

SENIOR STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

FASHION EDITOR

Aly Ishikuni

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

ASSISTANT DESIGNERS

Haren Soril

Mitchell Valenzuela

IMAGES

Tina Grandinetti

Kapulani Landgraf

Jonas Maon

Geoff Mau

Justin Park

Bailey Roberts

Tommy Shih

Haren Soril

Sean Yoro

CONTRIBUTORS

Gary Chun

Beau Flemister

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Tiffany Hill

Mitchell Kuga

Tiffanie Wen

EDITORIAL INTERNS

Alden Antonio

Kaui Awong

Chris Gaspar

Hirona Ogawa

Kai Rilliet

Kim Yagi

COVER PHOTO

John Hook

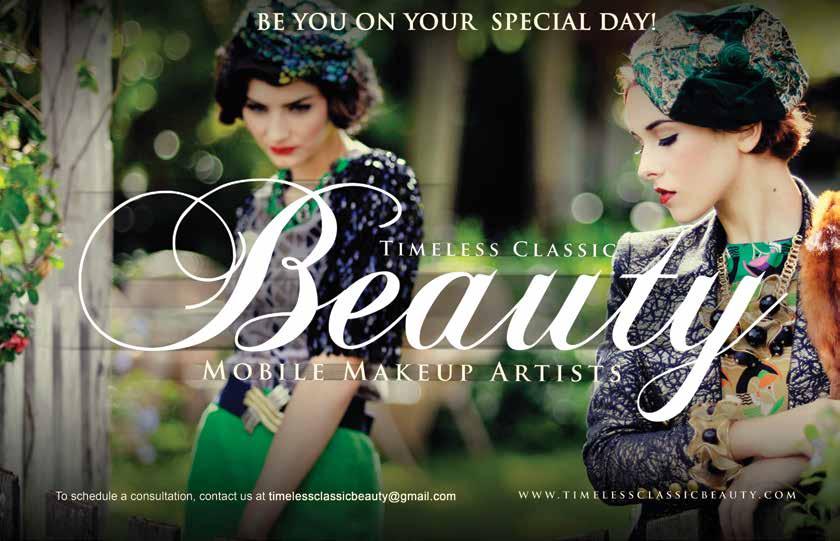

BEAUTY

Dulce Apana, Timeless Classic

Beauty

Lena Scanlan, J Salon

COPY EDITORS

Anna Harmon

Andrew Scott

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Keely Bruns

VP Marketing & Advertising kbruns@nellamediagroup.com

Bryan Butteling

Account Executive bryan@nellamediagroup.com

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

Chief Operating Officer joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne

Business Development Director gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro

National Account Manager jill@nellamediagroup.com

General Inquiries: contact@FLUXhawaii.com

Published by: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

2009-2013 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii. com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

MASTHEAD |

BEAU FLEMISTER

B EAU F LEMISTER IS A WRITER FROM K AILUA ON O‘ AHU ’ S EASTSIDE C URRENTLY BASED IN S AN C LEMENTE , C ALIFORNIA , HE IS THE MANAGING EDITOR OF S URFING M AGA z INE

He has had works published in various magazines across the globe and has traveled extensively to more than fifty countries. He is finishing his first novel entitled In the Seat of a Stranger’s Car.

TINA GRANDINETTI

T INA IS A WRITER AND WANDERER WHO RECENTLY SPENT FOURTEEN MONTHS TRAVELING THROUGH COUNTRIES IN A SIA , THE M IDDLE E AST, E UROPE , AND THE P ACIFIC

She is back in Hawai‘i pursuing graduate studies in indigenous politics at UH Mānoa, hoping that a mountain of books might help her to make sense of the questions she accumulated during her travels. Tina highly recommends taking some time to live out of a backpack, eat foods you don’t recognize, and listen to stories in languages you can’t understand.

MITCHELL KUGA

M ITCHELL K UGA IS A FREELANCE WRITER AND WAITER FROM M OANALUA , CURRENTLY BASED IN B ROOKLYN

He is an editor of SALT, a magazine about food and pain in New York City. Interests include doughnuts, yoga, beer, Spam, and kale. Books are cool too. He is eating an egg salad sandwich with jalapeno chips as he writes this. He’ll move back to Hawai‘i, eventually.

HAREN SORIL

H AREN S ORIL IS A FASHION AND ADVERTISING PHOTOGRAPHER BASED IN H ONOLULU

Born and raised on the island of Maui, Haren became inspired to do photography by his dad’s hobby of taking portraits of his mom. Since then, Haren has extended his infatuation with portraits to fashion and wants to someday be as great as his idols Steven Meisel and Patrick Demarchelier. Currently a graphic design student at UH Mānoa, he plans on expanding his creative knowledge to conquer the editorial fashion and advertising world.

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | CONTRIBUTORS |

I came across your recent issue of FLUX while eating at Pig and the Lady. This is the first time I ever heard of your magazine, so I didn’t know what to expect. The photos were very lovely and the best I have seen. I then came across the 442nd story and was so happy to learn the history of the lost battalion. I was a year old when my older brother died while he was serving in the 442nd (which I only found out two years ago from my other brother), so thank you for sharing their story. I will keep this magazine as a memory of him and send to my family.

If I could recommend editorial or an issue featuring a cooking guide for people who shop at farmers markets. I go to these markets and see all these wonderful fruits and vegetables, but I don’t know what’s the best way to cook it. It would be easier if I had a computer, but some people love learning from books.

Linda from Kailua

Be on the lookout for our spring 2014 issue, hitting newsstands February 2014, which will showcase local food producers and purveyors, along with some of their favorite recipes.

Currently I’m in Honolulu for the first Hawaii Fashion Month. Your magazine is beautiful and I’m reading your Heritage issue now. The cover photo is amazing, and the “Warps in Time” article fascinating. I am surprised your magazine isn’t featuring any of the fashions from the amazing local designers in photo layout “Adorned Lineage.” There is some exquisite designer resort wear made locally, which also supports the Hawaiian economy. Perhaps your magazine will feature some of these designers’ work in the future.

Giovanna

Melton Los Angeles

That’s a great suggestion. Tune in to our next issue of FLUX, which will include a section dedicated especially to our local designers. Local designers, if you would like to be considered for this special feature, send lookbooks and inquiries to the editor, lisa@fluxhawaii.com.

W E WE lcom E a N d valu E you R f EE dback. Send letter S to the editor via email to li S a@fluxhawaii.com or mail to flux h awaii, 36 n h otel St., Suite a , h onolulu, hi 96817.

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | LETTERS TO THE EDITOR |

FOLLOW FLUX @FLUXHAWAII

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

House made kabocha ravioli w/ sage brown-butter, balsamic cipolini onion, toasted pumpkin seed

Sous-vide duck breast, cherry gastrique & braised kale

House made kabocha ravioli w/ sage brown-butter, balsamic cipolini onion, toasted pumpkin seed

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

Combating the Complexities of Homelessness

T EXT BY T IFFANY H ILL

Homelessness is a broad, complex issue, one without a single panacea to providing stability and roofs over the heads of the more than 6,300 homeless people on O‘ahu.

There are an estimated 6,335 homeless people on O‘ahu. This number fluctuates, but the harsh reality is that these people—children, veterans, those who need mental health services or drug rehabilitation—do not have homes. Home is the street corner, the beach park, the bus bench, until they’re told to move along only to settle in at the next corner, the next beach park. The fight to end homelessness is being waged on many fronts by the city and state governments, local churches, and tenacious nonprofits with small staffs and smaller budgets. Here are five people making a difference when it comes to finding permanent shelter for those who have nothing to come home to.

WHAT

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

Homeless

Combating the Complexities of Homelessness

DARRICK NAKATA

Assistant pastor, Cedar Assembly of God

“The homeless aren’t homogenous. There’s a diverse mix: families that just lost their house, people with drug problems, people who have been homeless for years.”

When nonprofit workers and policy makers talk about the homeless on O‘ahu, Darrick Nakata understands their struggles better than most. The 57-year-old was homeless for three years, before going into the Next Step Shelter in Kaka‘ako, where he stayed from 2008 to 2010. Today, Nakata does outreach work with those who are now where he was, building relationships with the women and men living on the street by sharing his experiences. He also ministers to them through his work with the Cedar Assembly of God. He encourages them to visit the church, but also a shelter. “It’s nice to have a place where you can put your things,” he says, especially because of the city’s increased sidewalk sweeps. But the goal once they’re in shelters is to eventually leave and become self-sufficient, just like he did.

PAMELA MENTER

Former executive director, Safe Haven

“We see magic happen here at Safe Haven. Housing itself is treatment; we help them get stabilized.”

For the past eighteen years, Safe Haven, a temporary shelter with twenty-five beds, has been giving women and men a place to stay and providing case management, psychiatric and medical services, job skills training, and permanent housing placement. It’s based off the national Housing First model, in which homeless are given housing first and then given treatment for mental illness and/or substance abuse. The city unveiled plans to further expand the program this May. Safe Haven is part of the organization Mental Health Kōkua, and its staff go into the community weekly, often developing a rapport with their future clients for three to six months before admitting them into Safe

Haven. Menter says the mission of Safe Haven is to help those who are both mentally ill and chronically homeless while simultaneously breaking down the stigma of those in need of mental health services.

COLIN KIPPEN

State homelessness coordinator

“We could be more effective if we look at housing. … The problem is, we’re not just a local [housing] market, we’re an international market. And that drives up the prices.”

Colin Kippen has a lot of reports passing across his desk. Kippen was appointed the new homelessness coordinator this June. He says the target is the chronic homeless population: those who have been homeless for more than a year, or who have had three episodes of homelessness in a year. Both the city and the state are developing better intake assessments and referrals for services so that no funding gets wasted, he says. To Kippen, the biggest issue is affordable housing, or the lack of it. The state estimates that Hawai‘i needs 30,000 affordable units, many of which need to go on O‘ahu. One of his top priorities is working with the legislature, developers, and existing landlords to create low-cost housing. That’s how you will keep people off the streets, he says. “The population I’m worried about are the homeless who are not able to get into housing, but there’s also a population that’s right on the edge of homelessness.”

CARLOS PERARO

Consultant, C. Peraro Consulting

“Hawai‘i is unique because of the large number of unsheltered homeless we have.”

To decrease homelessness, it’s important to know just how many people are homeless. Consultant Carlos Peraro co-authored an independent report, released this September, on the number of unsheltered homeless individuals. (The state does one, too.)

Volunteers canvassed O‘ahu one night in January, asking people where they slept the

previous night, as well as collecting their names, sex, age, veteran status and any disabilities. They gathered the information of 1,465 people (out of a total of 6,335 of homeless people, including those who are in the shelters and transitional housing). It’s a number even higher than previously reported by the state, but that number is likely higher. Because of mental illness, less-experienced volunteers, and hard-to-find homeless individuals, Peraro says it’s reasonable that there are hundreds of additional unsheltered people with which volunteers didn’t speak. One hypothesis, he says, is simply the weather: Many Mainland communities deal with inclement seasons, whereas Hawai‘i doesn’t. “Here, the homeless don’t necessarily have to go to shelters,” he says. The study also highlights that many of the chronic, unsheltered homeless are living along the Wai‘anae Coast and in the downtown area.

DARRYL VINCENT Chief executive officer,

U.S. Vets Hawai‘i chapter

“The number one cause of homelessness is poverty. With veterans, there’s no difference, but there’s less propensity to ask for help.”

An estimated 10 to 15 percent of the homeless population, both locally and across the nation, are veterans. For the past decade, Darryl Vincent, CEO of the Hawai‘i chapter of U.S. Vets, has been working to decrease that statistic. The local chapter has a 100-bed transitional housing in Barbers Point, where veterans can spend up to two years at no cost, getting drug and mental health treatments, job training, and permanent housing placement. U.S. Vets helps homeless veterans across O‘ahu and is the only organization with that specific mission. Most of the clients are men, many of whom served during the Vietnam War. However, Vincent is seeing an increase in clients who served during the Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts. “Our demographic has changed within the past years,” he says. But the purpose has remained the same.

Darrick Nakata understands the struggles of homeless better than most. The 57-year-old was homeless for three years, before going into the Next Step shelter, shown here in an article from FLUX’s first issue in 2010. Today he does outreach to homeless as the assistant pastor of Cedar Assembly of God and encourages them to visit the church, but also a shelter.

LOCAL MOCO: FLYING

DAY

The boys of Aloha Stadium voyage to Long Beach for the Red Bull Flugtag event. And beyond.

BY BEAU FLEMISTER

On a clear day in Long Beach, a bright yellow, Victorianstyle home sprouting balloons from its chimney plummeted into the sea from a thirty-foot runway. Five minutes later, four zombies, faces green with death, shoved a miniature Queen Mary ocean liner off the ledge, the fifth zombie hanging precariously to the bow. After that, a flimsy UFO saucer pushed by breakdancing Martians went off the ledge, followed by a dental student riding a four-foot-tall molar on wheels.

I MAGES

T OMMY S HIH

|

BY

Then everything went silent. And a voice boomed, accompanied by subtle ukulele plucks. Ua mau / ke ea o ka ‘āina / i ka pono. God’s voice. Bruddah Iz’s voice. Though no one knew the language, a crowd of 100,000 went weak at the knees, the words rattled their bones and bubbled in their chests. It was a voice not from the million-dollar speaker system, but from the heavens themselves.

A craft approached the Red Bull Flugtag platform, a double-hulled voyaging canoe a la Hōkūle‘a, floating on Bruddah Iz’s song. The sight of it was mystical, in the sense that One-Eyed Willie’s pirate ship in The Goonies was mystical. It was a craft so regal and legendary it had to have sailed 3,000 miles in from O‘ahu, guided by a map of stars and wind patterns and ocean currents and cloud clumps and legends and shark fins.

“In German, flugtag means ‘flying day.’ But for us,” says Richard Chan, pausing carefully to deliberate, “it’s just another reason to party.” Since its inception in Austria in 1992, Red Bull Flugtag has pitted competitors against each other to see who can build the best human-powered flying machine. None of the contraptions exactly “fly” though; mostly, Red Bull Flugtag is about camaraderie, being on a

team, and trying not to make a complete ass of one’s self.

Chan is the team captain of the first ever team representing Hawai‘i in Red Bull Flugtag. Dubbed “Aloha Stadium”—derived from the nickname for their seven-bedroom house in Kapahulu that they share—the crew consists of Chan, Takeru Tanabe, Kekoa Eskaran, Erik Beattie, and Chris Tseu. “There’s always shenanigans going on at our house,” says pilot Tanabe. “And just like the actual stadium holds big events, we always hold huge, fun parties at our house.” The five have known each other since high school (Tanabe and Chan since fourth grade), nearly a decade ago, and have bonded over their love for the ocean, their love of taking air-drops at Sandy Beach, and their ability to never take life too seriously.

In preparation for the event, the team spent nights after work constructing the craft. Luckily, building came natural: All have trade backgrounds, from carpentry to construction to HVAC. And when it came down to it, falling over the ledge of a thirty-foot pier in front of a gawking audience was basically just another day at Sandy’s.

On the day of the event, with the whole world watching, a king in a red and yellow feather cloak stood upon the craft

and braced himself while a crew of four pushed the canoe down the runway. It barely made it over the platform before the mainsail collapsed, the king falling through the canopy, the craft nose-diving like a shot-down duck. It was a fate similar to the fate of many that day, a fate that could be compared to lemmings jumping off cliffs to their deaths.

The thing about lemmings, though, is that their purported mass suicides are a misconception. Rather, their deaths many times are simply the result of miscalculated migratory behavior. So maybe—just maybe—the boys of Aloha Stadium had sailed over to Long Beach, and their three-second jump was just part of their passage back home—a brief migratory hiccup. Because if the laws of gravity tell us anything, it’s that what goes up, must come down, and those that leave Hawai‘i, will always return.

Immediately after the king fell with the canoe, the others in the crew followed him in, four separate gainers off the Red Bull runway, because like lemmings, or Goonies, or decade-old friends, where one goes, the others follow.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

A king falls. Team Aloha Stadium’s double-hulled canoe entry at the Red Bull Flugtag event takes the plunge at the Long Beach harbor.

Jared Yamanuha’s artwork for his first solo show, Omiyage, will “re-gift” familiar food brands as reconceptualized works of art.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

iconic omiYaGe of hawai‘i Jared Yamanuha

A longstanding tradition in Hawai‘i is to bring back little gifts for family and friends that share a small portion of one’s extensive travels across the Pacific. They’re usually in the form of omiyage , a Japanese cultural practice of buying food gifts (usually snacks) that we think best represent the region we’ve visited.

Hawai‘i has a rich collection of omiyage itself, the result of our multicultural and ethnic mix. Omiyage also happens to be the title and subject of Jared Yamanuha’s first solo show, opening in November at The Human Imagination with the help of local collector Dean Geleynse and artist John Koga, both of whom Yamanuha met while on assignment for FLUX. Displaying a new approach and sensibility to his art, Yamanuha will take familiar food brands of the islands and “re-gift” them as reconceptualized works.

“For this show, I’m ‘visiting Hawai‘i,’” Yamanuha says, “and the final photographic objects are gifts that are ‘made in Hawai‘i.’”

Local folk will be familiar with the logos Yamanuha has meticulously worked with his X-acto swivel-blade knife over the course of a year and a half—a series of Hawaiian Sun juice labels, the front page of a Longs Drugs Sunday advertising tabloid, a box

of Hawaiian Host chocolates, mochi from Nisshodo Candy, and manju from Two Ladies Kitchen in Hilo.

Yamanuha gravitated to photography to express himself early on, citing the American photographer William Eggleston as an initial influence on his photo work. His first art show, a collection of digital photographs of everyday objects and landscapes, took place in 2009 and was displayed at the former Borders Books & Music in Ward Center. On display were images Yamanuha found visually interesting: a shadow cast on a wooden deck, city lights shining through a broken screen window, a cluster of handmade signs and advertisements, the view of a sunset through an airplane window. The following year, Yamanuha showed at Borders again. This time around, he presented a set of digitally manipulated picture collages assembled into mandalalike shapes.

It was Geleynse who first recognized Yamanuha’s burgeoning talent after purchasing one of the mandala images from the 2010 show. It was also Geleynse who later commissioned Yamanuha to cut patterns into a photo of the Leonard’s Bakery logo, the first of the dozen pieces that now make up Omiyage.

After seeing that initial Leonard’s Bakery piece, Geleynse says he became “intrigued by Jared’s obsessive, detailed hand-cutting patterns, but also by the relationship and connection to iconic Hawaiian brands that we all can identify with in some way or another.”

Working on photo prints that are usually ten-by-fifteen inches, Yamanuha lets the shape of a particular logo design speak to him about how to cut into it while keeping the proportions. The results of his flowing cuts give an additional vibrancy and life to the familiar island designs. “It’s a celebration of the visual culture of Hawai‘i,” says Yamanuha. “Those that have seen the pieces I’ve been working on, I’m happy that they immediately get what I’m doing here. They see what this place means to me and the importance of food-related gifting. With the concept of omiyage, I’m representing these re-worked images back to the people of Hawai‘i.”

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27 TEXT BY GARY CHUN FLUXFILES | ART IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

an avatar wal KS into a whi SK e Y B ar

K ahana K alama , founder of life S t Y le B outi Q ue aloha S unda Y, B rin GS a little aloha to S an die G o .

T EXT BY B EAU F LEMISTER

I MAGES BY J OHN H OOK

While I wait in a whiskey bar in North Park, San Diego, a mustached bartender in a bow tie and suspenders slides over my drink. On the walls glow bottles of aged bourbons and expensive scotch and the stereo blares a notso-popular-but-totally-awesome Beatles song. I’m on-ly slee-eeeping… It’s the kind of bar where you know the whiskey sour will be the real kind (with egg whites) without having to ask. The shuka-shuka, shuka-shuka shake of mixed drinks sounds like maracas, pervading seven separate conversations. The bar is a song.

And then a man walks in and the seas part. The shuka-shuka ceases, and everyone watches as the specimen moves through the room. A woman glances at the man while talking to her date, coughs, and her Old Fashioned spurts from her nose. The man is distractingly handsome. Six-feettwo-inches, chiseled, effortlessly dressed. A Polynesian avatar. This man is Kahana Kalama. He sits down beside me. I should’ve worn a different shirt.

Kalama, born and raised in Kailua, owns a shop called Aloha Sunday a couple blocks down the street from this bar. It’s been there for three years now. His shop fits well in the hip and walkable urban community of North Park the same way this craft-cocktail whiskey bar does. Which is to say that his shop, this bar, and other outfits and restaurants share an ethos with the town. What’s that mean?

“The ethos?” says Kalama. “Well, I just

really like personal, thoughtful people, the conscientious customer. The customer that really digs into a product and doesn’t want to buy something just because everyone has it, but more because it has a story, and they vibe with that story behind the product.”

A burly man with long, wild hair recognizes Kalama, cuts in, and asks about his store and family. The guy looks like he’s in either a biker gang or a metal band— or both—but nonetheless is crippled by Kalama’s smile.

Kalama’s product is not only a store but a brand as well. Primarily a men’s clothing line, carrying blazers, denim, aloha shirts, and more, Aloha Sunday is also kind of sort of a surf shop. “For the surfer that’s growing up or finding himself in professional positions,” he says. Kalama was also a professional surfer once, touring the world after graduating from Point Loma in San Diego, so he kind of sort of knows his shit.

But Aloha Sunday isn’t your runof-the-mill, Quik-through-Volcom surf shop. “We’ve got some surf necessities— boards and wetsuits—but we’re more of a men’s store. Basically anything you’d use in everyday life.” “Anything” includes, but is not limited to: facial scrubs, face masks, moisturizers, coffee, soaps, candles, toothpaste, throw pillows, aftershave, more candles, cufflinks, sling shots, space pens, and tree swings. All are premium products, with some imported from Italy and Japan,

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

Kahana Kalama’s carefully curated lifestyle boutique, Aloha Sunday, remains inspired by his experiences in Hawai‘i and growing up on O‘ahu’s Eastside.

Carrying candles and cufflinks, sling shots and space pens, Aloha Sunday is more than the average surf shop, with an assortment of premium men’s products.

and all cut-and-sew made in America. The clothing: classy, well-fitting stuff (for a surfer), but affordable, comparatively. “I wanted to manufacture products in a way that I’m proud of,” he says. “Some people might say that it’s a trend, but there’s an authenticity in it and it’s that authenticity that spawns other trends.”

An eavesdropping bartender cuts in and asks Kalama if he knows so-and-so. Kalama’s presence is that magnetic. The personification of “comfortable in his own skin.” Every word is intentional, calculated, authentic. And, how did a local kid from Kailua get into this racket? “I was kind of that kid that grew up surfing and skating, but didn’t really hang out with the skaters and surfers,” says Kalama, who hung out more with the graphic designers, the guys in ad firms, charities, and nonprofits. He started working with the brands that he surfed for. He stayed in San Diego. “And then I moved up here to North Park and found a bunch of kids just like me.”

I ask Kalama how San Diego had helped to inspire his brand, presuming how fashion seems to catch on to Hawai‘i a little later than some places. He corrects me. “Really, all my experiences come from Hawai‘i as a

kid. I grew up on the Eastside and kids over there hated on town for being so crowded. But me, I loved going over there and seeing how they dressed. The Japanese tourists and old Midwest couples with the matchymatchy aloha prints, the international costumes—I got a kick out of it,” he says. “Not to mention, when I was young, I was super small. And whenever there was a dress-up function, I had nothing to wear, so I’d have to wear my dad’s stuff, which of course was always so huge on me. All I ever wanted was some good-fitting clothes.”

I ask if he is planning on living in North Park forever. If there is a chance for an Aloha Sunday, back home. He nods, absolutely. “I love change; it’s part of why I came here in the first place. And a lot of why I’m doing this up here is to inspire the little me’s back in Hawai‘i. Like, don’t feel bad for not being a moke! Don’t worry about that, just do what you’re good at, care what you’re passionate about, and there’s a lot that can come out of it.”

We finish our drinks and leave the bar. As we’re exiting, a woman walking in looks up at Kalama and trips on her own feet. And I’m thinking about a new tree swing purchase.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

The issue of ag-lot developments has grown heated, and only a mere handful engage in legitimate farming activities. There are, however, some who are doing it right, like Dave DeLeon, shown here. Ryan Kingman, co-founder and VP of marketing at Stance, sits in the company’s new warehouse, which will be a Fantasy Factory of sorts to house their growing business.

S tandin G out from the crowd

r Y an K in G man , co - founder and v P of mar K etin G at S tance , S tand S out from the crowd with uncommon thread S.

T EXT BY B EAU F LEMISTER

I MAGES BY J OHN H OOK

This ain’t grey sweat suits and white tube socks / This is black leather pants and a pair of Stance…

There is nothing particularly poetic about this lyric, besides that it rhymes, but do you know who rapped that? Jay-Z did. “Stance,” by the way—or, “a pair of” them—are socks. Originally, and still presently, socks are made for skaters, snowboarders, surfers, and those of that culture. There is gravity behind this lyric though because Jay-Z is one of the most successful musicians and celebrities on the face of the earth. No other surf-skate-snow brand has ever had a celebrity of that nature give them a shout out in a lyric.

When I ask Ryan Kingman, co-founder and VP of marketing at Stance about this fortuitous, recent lyric, he is modest and blushes like a praised adolescent. He’s got a great smile. He also hints that Jay-Z ain’t the only card they got up their sleeve.

But who the hell is Ryan Kingman?

Let’s start with what he was doing before he was co-founder of a sock company whose business has tripled every year and is invested in by Jay-Z. What does that career path look like? Kinda like a crazy person’s. “When I was younger, I had a billion odd jobs,” says Kingman. He did. He worked at Tower Records, did masonry and construction in the summers, popped in at Subway for a day and California Pizza Kitchen for a few months, fixed signs at the Honolulu Zoo, cleaned cars for a rental

company, parked cars as a valet (and it’s common knowledge that valet parking is the gateway to greatness). “Now that I look back, it’s pretty pathetic,” says Kingman with a laugh. “Like, wow, I was a drifter.”

So before Ryan’s colorful resume during his 20s, and way before he became a super successful VP of marketing, surely he was a Punahou grad who went on to Stanford, majoring in business marketing, right? Nah. Ryan grew up in Maunawili. And Kahala. And Kailua. And Hawai‘i Kai. He went to Le Jardin, then Maunawili Elementary, then Our Redeemer, then got kicked out, then moved to Kaimuki Middle, then went back to Our Redeemer, got kicked out again, wound up at Kalaheo High for a year, then, “I baaaaarely graduated from Kaiser High School by passing a test that I may have cheated on,” admits Kingman.

I get the feeling that the successful sock VP may have been a handful when he was younger. Somewhere toward the end of his tumultuous 20s, Kingman left O‘ahu for a change. “I remember my dad came to visit me while I was living with some friends in a haunted house in Hawai‘i Kai. During this time I was partying a lot, and my dad told me I should clean up my act and come to the mainland to try something new. I moved to Costa Mesa and got my first job in the skateboard industry, but, like, at the bottom of the barrel of the industry.” Literally. His first job was scraping off the excess paint from the bottom of skateboard decks.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

With its bold graphics and unconventional prints, Stance has seen its business triple every year, part of the growing billion-dollar sock industry.

But Ryan kept at it, worked his way up, and became the team manager for the skateboard brand Element, his first viable career path. He ended up working for Element for more than ten years, becoming their marketing director and eventually director of global marketing. Then in 2010, he got a phone call from a friend. “He told me that they had a position opening up for a company they were creating. I was like, ‘What is it?’ and he tells me, ‘A sock company.’ Instantly, I thought, ‘Aww, socks? Whaaat?’ But I was flattered and I thought about how no one had done socks yet, so I made up my mind.”

Along with four other creative surf and skate industry brand-quitters (including Skullcandy founder Rick Alden and former Reef president John Wilson), Kingman would help to change the way the world in general thought about socks, which have grown into a nearly $3 billion industry. Since its inception, Stance has tripled its business every year and can be found globally in twenty-five countries and sold

in large retailers like Nordstrom and Foot Locker, as well as boutiques and surf shops.

Still. Besides being neat-looking, functional, and worn by young surf and skate icons like John John Florence and Nyjah Huston, how did this company get so…big? I mean, it’s just socks.

“Stance has grown quickly because of our obsessive focus on one product category,” says Kingman. “Socks have always been an afterthought for bigger brands. At the end of the day, we wanted our brand to be synonymous with socks, like how Levis is with denim, Nixon with watches, Reef with sandals. For us, and as a brand, socks were a new form of expression for the consumer. It was the last little bit of real estate on the body—everything else had been done.”

One might call Ryan Kingman’s success a Cinderella story (if they hadn’t already known he was a former valet). Kingman is a hip and humble family man now, even if he does still have that smile as mischievous as his youth. Kingman attributes his success to a few different factors. “I think from

an early age, I’ve had a strong work ethic because of working construction in Hawai‘i and the respect you learn living there. I’ve also had some great mentors throughout my life, like Mark Oblow for my career, and my wife, of course, keeps me in line. And then my kids—because of them, I want to do everything I can to give them every opportunity. But when it comes down to work, I’ve learned there’s two things that can get you anywhere: personal networking and resourcefulness. If you’re a good problem solver that finds solutions, you can do anything.”

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

While his aesthetic has evolved from surf designs to something more universal, Moses Aipa, senior creative brand director of Incase, remains inspired by his ethnically diverse background.

mo

inca S e of emer G enc Y

Walking into Incase HQ in downtown San Francisco is like walking into an iPhone—it’s all clean lines and curved edges, with windows overlooking the hustle and bustle on Mission Street from a thirdstory view. The scene below is chaotic on this particular Tuesday afternoon, but inside the office, it’s organized and surprisingly low-key, with an undercurrent of intense productivity much like the signature smart phone itself.

This is fitting of course, since the company, which was founded in San Francisco in 1997 and has collaborated with everyone from fashion designer Mara Hoffman to pro skateboarder Paul Rodriguez, has designed accessories exclusively for Apple for more than ten years. If you’re an Apple addict, chances are you’ve run across one of the company’s cases, backpacks, or messenger bags designed to encase iPhones, iPods, iPads, or MacBooks.

At the helm of Incase’s creative arm is a Hawai‘i native, 32-year-old Moses Aipa. After growing up in Kailua, Aipa moved to the Bay Area in 1998 to attend the University of San Francisco, where he took classes in graphic design. “When I was a senior in high school, I applied to colleges in California to break out of Hawai‘i. Initially I was looking for a school that had a surf team,” he says. Despite the fact that it was one of the only colleges he applied to without a surf team and that he had never been to San Francisco before, Aipa decided to attend USF at his parents’ urging.

T

EXT BY T IFFANIE W EN

MAGE BY G EOFF M AU

It proved to be a wise decision. In his senior year, he got freelance work for Incase through a friend as a graphic designer, creating a series of brochures. He continued to grow with the company, taking on various roles, gaining experience and getting his “hands on everything” along the way. Today he’s the senior creative brand director for one of the world’s largest producers of cases for Apple products, managing several design teams and guiding the overall aesthetic for the company.

While his aesthetic has evolved from the surf designs he experimented with in his early days of school (his uncle Ben Aipa is an ex-pro surfer turned board shaper and his cousin Akila Aipa is currently a pro surfer) to something more universal, he says he’s still influenced by growing up in Hawai‘i’s melting-pot culture and his own diverse background. When asked what constitutes his ethnic makeup, he answers without taking a breath, “I’m a quarter Hawaiian, quarter Portuguese, quarter Korean, and the rest is parts Irish, German, American Indian, and Chinese.” So what food does he love the most? “Japanese,” he says, then quickly corrects himself: “And Hawaiian.”

While he occasionally gets out to surf in nearby spots like Pacifica or Stinson Beach, he doesn’t have that much time, what with traveling to places like China, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, and Germany for Incase. Which, other than meaning he has the most envious job on the planet, also inspires his

aesthetic and means that he can “use and experience and live the products, and see how others are getting a piece of them too.”

Those products include upcoming designs for spring 2014, which will include cut-and-sew leather iPhone cases to match the premium nature of the iPhone 5s and distinguish Incase from other tech and lifestyle brands that manufacture plastic protective cases. “Zagging when everyone else is zigging,” as Aipa puts it. Also coming down the pipeline will be a series of accessories for the various iPads, meant to help people make use of the portability of the devices, which he says often get stuck at home.

Eventually, Aipa hopes to become more portable himself, establishing a bi-coastal lifestyle and splitting his time between California and Hawai‘i. Until then, he’ll continue making sure good design is just a phone call away.

S e S ai P a , S enior creative B rand director of inca S e h Q in S an franci S co , en S ure S a B etter ex P erience throu G h G ood de S i G n .

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 39

I

Since 2001,

and

the S weet life

J a Y K inima K a mu S e , owner of lulu ca K e B outi Q ue in new Y or K, whi PS u P S weet deli G ht S in cele B ration of love , life , and ever Y thin G that come S with it.

TEXT

BY MITCHELL KUGA

IMAGES BY B AILEY R OBERTS

For someone who has lived in New York City for more than eighteen years, Jay Kinimaka Muse, the owner of Lulu Cake Boutique, is incredibly modest. Though he’d never use that word. “Isn’t that the least modest thing you could say?” he says, sitting in Lulu Cake’s small storefront in Scarsdale, New York, about a twenty-minute train ride from Manhattan. His is a modesty that approaches self-effacement. Even though he’s the sole founder of Lulu Cake Boutique, Muse shows up second on the website’s list of chefs. He’s rejected numerous pitches from networks to star in reality television shows. And when he turned down an appearance on Rachel Ray to attend his Kamehameha High School reunion in October, he mostly told classmates that he’s been “working at a bakery.”

“I’m not shy,” says Muse, who is 40 years old. “I just don’t think it’s important to talk yourself up. It’s not who I am. I guess if you feel good enough in your heart you don’t have to broadcast it. It’s probably a Hawai‘i thing.”

“Working at a bakery” means being in charge of more than 200 employees who handcraft, package, and sell anywhere from 100 to 200 wedding cakes a week, in addition to creating smaller bites like retro Twinkies and cookies infused with Maui potato chips. When Muse founded Lulu Cake Boutique in 2001, instead of competing with other wedding cake companies, he created his own market: unconventional, organic, farm-to-table cakes. All the flour used is

organic, unprocessed, and unbleached. “It’s the taste aspect,” Muse says, while acknowledging that the cakes are still made with all the caloric splendors that compose a mouthwatering dessert. “But if you’re going to have butter, why not have real butter from a farm upstate?”

The results are wedding cakes that look, feel, and taste like international productions. Chocolate is sourced from Africa, vanilla from Portland, and honey from a beekeeper on a rooftop in the Bronx. Muse has visited most of the vendors, including the one in Africa, to establish a connection with small-business owners.

“That’s what it’s all about. There should be a story behind everything we eat,” he says. Hawai‘i also gets a fair nod. Coffee extract is produced via beans from Waialua Estate, and the coconut custard featured in the Coconut Dream is actually homemade haupia custard. “The Jewish people go crazy over it,” says Muse. Similarly veiled, the fruit in the Passionately Kissed—vanilla cake, passion fruit curd, white chocolate— is actually lilikoi. Another top seller features macadamia nut brittle. (An attempt with li hing mui didn’t go over as well.)

On the business end, Muse maintains a standard of aloha spirit. Even though he is currently the only Hawaiian in the company, he taught the staff “pono,” a concept they employ whenever there are disagreements amongst coworkers or customers. A portion of all proceeds are donated to breast cancer

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 41

Jay Kinimaka Muse has been infusing local flavors like haupia, lilikoi,

even li hing mui into his unconventional, organic, farm-to-table wedding cakes and sweet delights at his New York bakery, Lulu Cake Boutique.

foundations, and Muse has personally delivered cakes to children at the Make-AWish Foundation. He is currently pushing to get their building solar-powered.

“It’s just part of the culture I grew up in,” says Muse, a ’91 Kamehameha High School graduate. “We care greatly about the soil that we leave behind for future generations. We try our best to eliminate our footprint. We’re not perfect but we try.”

Muse left the islands to attend University of Southern California. Unfulfilled with screenwriting, he moved to New York in 1995 and went to law school at Columbia University. He’s been a New Yorker ever since. “As a hobby,” he and a bunch of friends opened a string of restaurants on a newly gentrified stretch of Amsterdam Avenue. After Columbia, Muse went to culinary school. He opened Lulu Cake Boutique a few months before 9/11.

Running the bakery through that period felt therapeutic to Muse, who watched the towers collapse through the kitchen window of his apartment on Central Park West. “For whatever reason that event was so catastrophic beyond belief that I still haven’t processed it. It was like a movie,” he says. From Scarsdale, where many bankers who work on Wall Street live, business took

off. “During wars, during recessions, during hurricanes, people always seek comfort in sweets,” says Muse. A few years later, Lulu Cake thrived through the recession, due in part to its position as a luxury product. (Wedding cakes start at $1,000.) Another reason is the dependability of celebration— people will always get married, and what better way to celebrate than with sugar? “I can confidently say it’s recession proof,” Muse says.

Lulu Cake Boutique is expanding internationally soon to Shanghai and Australia. Despite the success Muse knows he wants to settle back home in Hawai‘i.

In his 20s, transfixed by the intoxicating nightlife and creative grit of 1990s New York, Muse thought he’d be a New Yorker for life. But the city has changed dramatically since, and a recent trip home crystallized where he wants to spend his life post-retirement.

The realization didn’t arrive in a quiet moment on the beach, but behind the wheel of a car on the traffic choked streets near Ala Moana. After waiting a few seconds behind a truck after the light had turned green, Muse honked his horn. He switched lanes further down the road, and unintentionally pulled up next to the truck at a red light.

The guy in the truck had his window down. He gave Muse a bewildered look. Muse rolled his window down to apologize.

“I felt like a foreigner in Hawai‘i,” he says. “Although I knew I belonged and I’m from there, I was hurt at the disconnect I had with the island and felt envious of my classmates who are part of the culture there. I was also awakened by the aloha spirit more than I ever had been.”

At a Local Motion store, while in pursuit of apple butter pies he’d been hearing about, Muse struck up a conversation with the manager. After telling him he was heading back to New York, Muse was handed free stickers and T-shirts. The stranger even offered to deliver the pies to Muse’s house after they arrived later that afternoon.

“You know what? This is something you don’t find anywhere else in the world,” says Muse. “The energy, the spirit, it envelops you. You understand why people move to the islands—it’s the beauty of the land, but it’s also the beauty of the people. It all came to me.”

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

“The energy, the spirit, it envelops you. You understand why people move to the islands—it’s the beauty of the land, but it’s also the beauty of the people,” says Jay Kinimaka Muse.

two local BoYS

A story about brothers Adam and Grant “Lanai” Tabura’s spectacular ascendance on Food Network’s The Great Food Truck Race.

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | Op ENING MAGE BY J OHN H OOK

Prologue

There’s this movie that you may have seen called Slumdog Millionaire . The protagonist, Jamal Malik, finds himself in the hot seat, just one question away from winning 20 million rupees on India’s Who Wants To Be A Millionaire . His life experiences have led him to this point, stories from growing up an orphan in the slums of Mumbai giving him the answers he needed right when he needs them. Team Aloha Plate’s spectacular win on Food Network’s The Great Food Truck Race bears uncanny similarities to this sleeper hit in an almost too unbelievable to be true sort of way, even down to the spontaneous breaking out of singing and (hula) dancing in the streets. Except Aloha Plate’s ascendance wasn’t the work of any kind of script, but because of the astonishing real-life experiences of Adam and Grant “Lanai” Tabura. This is the story of two brothers and how their growing up on the island of Lāna‘i helped them understand the meaning of aloha and enabled them to do the kinds of things you usually only hear about in movies.

ChaPter 1: A DAM TABURA SAVES A LIFE

When Adam Tabura was 17, he saved a man’s life. It was four days after graduation, and like any teen wanting to prolong the trepidation that comes from thinking about the future, Adam was hanging out with friends at Manele Bay. Suddenly, he heard a man calling for help. Without hesitating, Adam jumped in and swam out 300 yards to where the man was drowning, pulled him in, and resuscitated him. Grow -

ing up on the island of Lāna‘i, Adam was used to visitors getting into trouble in the bay, the calm waters deceptive of the high surf that can hit at any moment. “Then I went back to my corner because it wasn’t a big deal,” says Adam. But to the couple, it was. Two weeks later, Adam came home to find his mom talking on the phone to Dale Proctor, the man whom Adam saved from nearly drowning in the bay. He wanted to repay Adam for saving his life.

“I didn’t know what I wanted to do with my life, but my mom was like, ‘Adam, you gotta take a risk and get off the island.’ We always grew up cooking, because can you imagine growing up on a small island, where you can’t just go to Jack in the Box or Foodland? We literally had to create everything. Cooking always brought us together growing up, and it stills brings us together.” Eventually, Adam decided he wanted to go to culinary school, and Dale, in his gratitude, would help to make that possible, paying half the cost of his tuition.

“Jumping in, it was just something I did, kind of like changing a tire,” says Adam.

“[Dale] didn’t take it like that. He took it like I was his hero.”

That knee-jerk reaction by Adam and the subsequent gratitude he was shown by Dale would forever intertwine the fates of the two men and send Adam on a culinary journey around the nation.

ChaPter 2:

L ANAI TABURA ROUNDS UP A CITY

In 2011, Lanai Tabura spearheaded the largest disaster relief fundraising campaign Hawai‘i has ever seen. Just two months after the Japan earthquake and tsunami, the Aloha for Japan campaign would raise $6

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

For Adam and Lanai Tabura, shown here with their family, growing up on Lāna‘i helped them understand the meaning of aloha and enabled them to do the kinds of things you usually only hear about in movies.

million for the survivors of the disaster.

The story of this incredible feat, however, begins on the island where Lanai grew up. The son of a single mom and the oldest of four brothers, Lanai learned how to take care of others before learning to take care of himself. “We grew up really poor, on welfare, and since I’m the oldest and my mom had to work, I practically raised my brothers—cooked for them, fed them. If it wasn’t for my grandparents’ half-acre garden in our backyard, I don’t know if I would’ve survived, eating-wise, anyway.”

Despite the comfort of a close-knit family, Lanai’s aspirations proved too great for the small-town confines, and the big city lights of O‘ahu beckoned. He moved to Honolulu to attend Hawaii Pacific University on a volleyball scholarship, which he lost a year later after becoming fascinated with and immersed in the world of radio. By 19, Lanai would become a household name. Locals in their 30s and 40s may remember the smash hits “Rice Rice Baybee,” “Me So Hungry,” and “I’m a Filipino,” parodies of popular tunes sung by the 3 Local Boys (made up of Lanai and fellow radio personalities Jimmy “Da Geek” Bender and “da Kruzah” Alan Oda). The album was played across the state and the mainland, eventually selling more than 100,000 units. “We were the social media back then,” says Lanai. “We had two out of every three teens listening to us at one point in Hawai‘i.” Lanai would go on to found the Hawaiian and reggae radio station 98.5, which would become an overnight success. By the time he was 30, Lanai owned three homes, drove a Mercedes, and was living the dream. Then “I lost it all,” he says. “Lost all my homes, lost the station, lost all my money, lost my fiancée of seven years, as a result of being stupid, partying too much—you name it, I did it.”

Broke, filing for bankruptcy, Lanai began seeking out what to do next with his life. He began meeting with people he’d built relationships over the years, mentors like Mike McCartney, currently the president of the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority; Pono Shim, a kahu known for his ideals of pono and aloha and president of Enterprise Honolulu; Raymond Noh of Noh Foods.

“I’m out to dinner with Raymond,” recalls Lanai, “and he tells the people we’re with, ‘You know this guy, he can bring people together that don’t know each other, that don’t like each other, don’t speak

English—it’s amazing.’” A few weeks later, he finds himself sitting in Shim’s office, the kahu telling him, “‘Lanai, I bet you help everybody.’ And I go, ‘Yes, that’s probably my biggest downfall. Everybody always wants something from me.’ And he goes, ‘That’s a gift, you know, helping people.’”

A month later, Lanai found himself in a room with the owners of local clothing companies Barefoot League, Fitted, In4mation, Buti Groove, and HiLife, posing the question of how these local brands can figure out a way to work together instead of against each other and in a way that’s mindful of the culture of Hawai‘i. Over the course of six months, Lanai and the ten owners met monthly, taking field trips to places like Bishop Museum to learn about traditional Hawaiian clothes making or to visit Daniel Anthony to learn how to pound pa‘i‘ai. The day before they were to meet Anthony, the tsunami hit Japan. “Everyone wants to cancel the meeting,” Lanai recalls. But he convinced the owners to show up to the Sand Island spot where they were to receive the lesson from Anthony. As soon as they all arrived, with tensions high over the effects of the tsunami, the ten owners start arguing immediately. Over the past six months, they had been talking about creating one brand as a collaboration project between all the brands. “I tell everybody, ‘You know what, you guys have been arguing for an hour already, let’s just stop, continue this later, everybody hug each other.’ So they stop, sit down, Daniel gives a great message about working together—eh, they had such a good time pounding. … Then we look up, and every boat in Honolulu is on the horizon. Because of the tsunami, they had to move all the boats out.” Lanai doesn’t recall exactly who said it, but someone suggested doing something for Japan. “So I said, ‘Brah, lets share some aloha for Japan.’”

That day, they collectively come up with the Aloha for Japan logo, and by week’s end, 10,000 shirts had sold. To date, with the help of Pono Shim, Mike McCartney, and 160 local organizations including banks, schools, media outlets, and restaurants, the campaign has raised just under $10 million for Japan relief and sold upwards of 50,000 shirts.

“Growing up on Lāna‘i was really the backbone of who we are,” says Lanai. “We grew up in a tight family, and everything that we’ve done in our lives has been based around aloha. My mom, as a single parent,

showed us what aloha was; our grandparents showed us what aloha was. We didn’t realize what it was when we were younger, but as we got older we realized it was aloha.”

ChaPter 3:

A DAM AND L ANAI SHARE ALOHA

ACROSS THE NATION

After zigzagging across the nation, covering more than 5,000 miles in two months, Grant Lanai Tabura, Adam Tabura, and Shawn Felipe have found themselves in a moment purely bittersweet. A crowd of Hawai‘i-ans nearly 200 deep managed to track the trio down to the nation’s capital, when someone decided that the singing of Hawai‘i Aloha would be appropriate for the moment. The flurry of activity ceased, Adam put down his knife, Lanai lowered his megaphone, and all three emerged from the sunshine-yellow truck that had carried them across the nation. Impromptu, in unison, voices rung out:

E Hawai‘i e ku‘u one hānau e O Hawai‘i, O sands of my birth Ku‘u home kulaīwi nei

My native home

‘Oli nō au i na pono lani ou I rejoice in the blessings of heaven

E Hawai‘i, aloha ē

O Hawai‘i, aloha.

E hau‘oli na ‘opio o Hawai‘i nei

Happy youth of Hawai‘i

‘Oli ē! ‘Oli ē!

Rejoice! Rejoice!

Mai nā aheahe makani e pā mai nei Gentle breezes blow Mau ke aloha, no Hawai’i

Love always for Hawai‘i.

It was a risky move for team Aloha Plate, stopping in the midst of competing on Food Network’s The Great Food Truck Race, considering even a few idle minutes could mean the difference between going home with $50,000 and going home empty handed. The pause, however, made no difference; it merely provided a moment to relish in what was already certain victory for team Aloha Plate.

That “chicken skin moment,” as Lanai calls it, tells the story of why Aloha Plate emerged as victors of The Great Food Truck Race. It’s a spectacular culmination of what

After their win on The Great Food Truck Race, Lanai and Adam Tabura will work on franchising the Aloha Plate brand, as well as on projects like Cooking Hawaiian Style, shown here. Image by Jonas Maon.

After their win on The Great Food Truck Race, Lanai and Adam Tabura will work on franchising the Aloha Plate brand, as well as on projects like Cooking Hawaiian Style, shown here. Image by Jonas Maon.

they experienced time and time again over the course of the show. “O Hawai‘i, O sands of my birth / My native home / Love always for Hawai‘i.”

“There’s a huge community of Hawaiians on the mainland called ‘Frozen Ohana,’” says Adam. “Think about it, if you’re living on the mainland for ten years, haven’t seen nobody, and someone says, ‘Eh, some Hawai‘i boys going show up down the road with food,’ trust me, you’ll go. That’s what’s crazy about the mainland— the aloha up there is way more tight. Because there’s less of them, they stand together stronger.”

In its fourth season and continuing to capitalize on the food truck craze, The Great Food Truck Race sent eight teams scrambling across the country, challenging competitors along the way to see who could cook and sell their way to the top. The race passed through eight states, starting in California, then Oregon, Idaho, South Dakota, Minnesota, Illinois, Maryland, and Virginia before ending in Washington D.C. In each state, teams navigated through the unfamiliar cities, attempting to find high-trafficked areas and good places to park (the key to any food truck’s success); drum up a crowd; and maneuver through “truck stops” and “speed bumps,” abrupt challenges given to the teams by host Tyler Florence. Some of these challenges included having to stop selling and move locations despite long lines of waiting customers or losing access to their car (which forced Lanai to run five blocks to the grocery store in order to restock on supplies).

Though all the teams struggled to deal with these physical challenges, the cooking challenges thrown at Adam were handled with ease. When teams had to harvest their own potatoes in Idaho, Adam and Lanai harkened back to their childhoods in the garden on Lāna‘i, growing sweet potatoes and cabbage on their grandparent’s farm. When teams were faced with butchering an entire buffalo carcass, Adam was able to swiftly slice through the carcass in just minutes because he grew up hunting deer, butchering them daily in the restaurants he worked at on Maui and Lāna‘i. When teams were given “unusual” ingredients like geoduck (known in Hawai‘i at sushi bars as mirugai, or giant clam) or Spam—well,

that one’s obvious. And no matter where team Aloha Truck pulled up to, there were always people waiting. “We’d call one person to tell them where we were going, then when we show up to the site, 200 people would be waiting, playing ‘ukulele, waving Hawaiian flag,” says Adam. “You see that, and you want to cry.” In many of the states Aloha Plate traversed to, entire hula halau would show up; musicians would jam; people would set up pop-up tents and talk story for hours. In Minnesota, Matt Camera, a Hawai‘i transplant who formed a Facebook support page for homesick locals called “Frozen Ohana,” organized a block party that continued on until midnight even after the day’s competition was over at 7 p.m.

Team Aloha Plate did so well that producers couldn’t help but think negatively. “Someone in line came up to me and said, ‘Eh, the producers think you’re cheating!’” says Lanai. “They were wondering how we get all these people here.” The dumbfounded producer even asked if they were flying the crowds in.

The show is also where the fates of Adam and Dale Proctor would once again intertwine. Shawn Felipe, the third member of team Aloha Plate who was responsible for driving the food truck across the country, shared Adam’s story during casting at the beginning of the show, which ended up being one of the major reasons they were chosen. Though Adam stayed in touch with the man whose life he saved, the communication between the two had dwindled over the years. But after Aloha Plate’s arrival in San Francisco, where Dale had first brought Adam to be a special guest at a banquet he was being honored at, Adam gave Dale a call. At many of the stops during the competition, Adam had a personal connection with that locale. Portland was where he went to culinary school (made possible by Dale), Minnesota is where Dale’s daughter lived (though they missed each other due to conflicting traveling schedules), and their final stop in Maryland brought Adam face to face with Dale’s two sons and grandchildren. “I got to meet all the grandchildren, and shake the hand of his oldest son who I had never met. His son was just in shock, like, ‘You saved my dad?’

“I never asked [Dale and his family] for anything, and they always wanted to be

a part of my life, but I kept them out of it because it was just a good deed,” Adam continues. “And now I realized that this was such a good opportunity to connect with these people, that the good God is making this circle based off of me saving him.”

ePilogue

Currently the Tabura brothers are working to franchise the Aloha Plate concept across the nation with a slew of trucks and brick-and-mortar restaurants. They are also working with 7-Eleven in Hawai‘i and Japan to create a line of Aloha Plate foods, including a bento and musubi, in which a portion of the proceeds from sales will go to SupportMyClass.org, a program that helps fund out-of-pocket expenses teachers incur in public schools. (A teacher in Nānākuli, for example, buys slippers for the kids to use because if they arrive to school shoeless, they get sent home.)

“Ultimately, we want to just keep producing Hawai‘i and letting the world know there’s a lot of aloha to share,” says Adam. “After going inland, I really felt some of these places are so messed up, so they appreciated where we were from. My biggest thing after traveling: I think people here in Hawai‘i need to be more aloha themselves. I hate when I hear people say they’re Hawai‘i this or that, but they don’t put off a good spirit.”

Lanai continues: “Everyone puts themselves into categories and talks about how their culture is ‘Hawaiian’ or ‘Japanese’ or ‘Filipino,’ but if you really think about it, we’re all the same. We all ran with our slippers on our hands to go faster, we all ate li hing mui or shave ice. That wasn’t Hawaiian, Japanese, or Filipino—that was Hawai‘i. ... Yes, aloha is the Hawaiian way, but aloha is the responsibility of all of us.”

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 49

the laSt StatueS of Ku

TEXT BY S ONNY G ANADEN | IMAGES BY J OHN H OOK

In 2010, the three remaining statues of Kū, the Hawaiian god of war, fishing, and masculinity, stood at Bishop Museum in Honolulu, the last in the world of their kind. Two had traveled across the ocean, on loan from the British Museum in London and the Peabody Essex Museum in Boston, to join the third at Bishop Museum’s newly renovated Hawaiian Hall. Three years past the statues’ homecoming, the two since shipped back to their permanent homes in London and Boston, a community remains engaged in a dialogue regarding art, religion, and reverence for history. If there existed such a thing as a Nation of Hawai‘i, the Kū ki‘i (statues) that reside abroad would be amongst its national treasures. Their return may be inevitable.

reach, as if the statues will be back next week. What Kahanu describes as miraculous was in fact the result of hard work by her office, the staffs of several institutions, funders, and a Hawaiian community united by shared history.

The ambitious idea of bringing statues to Honolulu from abroad was raised in a presentation by Kahanu at an exhibit of Oceanic art in Paris in 2008. “At first, the other museums weren’t convinced that the community would be supportive of the exhibit,” she says. “Another museum director had come here in previous years and seen discussions in which the community was certainly not unified.”

You have probably seen Kūkailimoku, also known as Kū, the war god, the snatcher of kingdoms. He is usually depicted with his arms to his side, knees bent for battle in a cubist, angular carving. His head is roughly the same proportion as his body, with an animalistic grimace, flared nostrils, and huge eyes. “Ours and the other two that visited are carved from ‘ulu [breadfruit],” Noelle Kahanu, project manager of Bishop Museum, tells me. “There is a fourth that has survived that is twenty-nine inches, also with the British Museum. The others are all around seventy-seven to seventy-nine inches.”

It takes lots of work to bring two 800-pound war gods from Britain and Boston to Honolulu. “The Bishop is the repository of much of Hawaiian history, of our ali‘i. It’s just miraculous that this even happened,” says Kahanu. As she speaks, I notice that her office has become the unofficial storage for the 2010 Kū exhibit, despite the end of its run three years ago: a four-foot cardboard cutout of the statue that returned to the British Museum is stacked against the door, posters of the event line her walls, and all the press materials are within

Kahanu assuaged these concerns by meeting with numerous Hawaiian scholars, historians, artists, and advocates. With soft skills and eloquent letters, she pressed for the exhibit. “Were you to seriously consider this request,” she wrote, “women would prepare wauke and pound kapa for his malo, men would craft chants in his honor. It would mean sending Hawaiians to Massachusetts, so that they may ready Kū for his trip, making clear to him that his return would only be temporary. It would mean readying Hawaiians at dockside, chanting his arrival. It would mean his being enveloped once again in his elements, standing alongside his brethren. But what would it mean to the Hawaiian community? … They survived the overthrow of their religion, they survived colonialism, war and destruction, they survived ignorance, racism and marginalism. When gathered, in solidarity, these Kū remind us that the essence forever remains.”

The letters worked. Bishop Museum settled on the title E Kū Ana Ka Paia: Unification, Responsibility, and the Kū Images for the exhibit and, with much fanfare, opened Hawaiian Hall in the summer of 2010 for a variety of groups, halau, and curious individuals. The Kū ki‘i were joined by other artifacts and items that once represented the Kingdom and culture of pre-contact Hawai‘i. Kahanu made good on

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 51

This Kū statue above is one of only three remaining in the world. The community remains engaged in dialogue about their return to Hawai‘i.

her letter as well. The statues were lovingly dressed for the season of Kū, with malo made by women with roots in Wai‘anae: Maile Andrade, Dalani Tanahy, and Kawai AonaUeoka. Discussions were had in the halls of the museum. The statues also inspired the work of several artists: David H. Kalama, Jr. spent fifty-four days drawing the statues in high contrast with charcoal; Solomon Enos and Meleanna Meyer worked on a large painting of a figurative being representational and reverent of the ki‘i.

“The return of the statues was difficult, but we had to respect that they were loaned to us,” Kahanu says. “At the Peabody Essex, he is a major component of their exhibit— celebrated. At the British Museum, there are no plans for him, though that one is beautiful. Unlike the others, his back is fully carved in what I think look like French braids. One woman came to the exhibit with a similar hairstyle. She told me, ‘My grandmother called this the hair of kings. I didn’t know what she meant at the time.’”

the snatCher oF KingDoms

The importance of Kū in the context of

Hawaiian history cannot be overstated. As part of a pantheon of Hawaiian gods including Lono, Kanaloa, and Kāne, Kū’s origin harkens to the Māori homeland of Hawaiki, and representations of him are vestiges of a state religion and a complex political economy that developed in Hawai‘i over a thousand years. In A Shark Going Inland Is My Chief, author Patrick Vinton Kirch, local haole and Berkeley professor of archaeology, deftly blends academic discussions of artifacts with the work of native Hawaiian scholars and the transcribed mo‘olelo (stories) of old Hawai‘i. This approach is fairly new. Historically, the oral histories of indigenous peoples, which acknowledge human emotions, passions, and ambitions, have rarely been taken as truth. By accepting that both the academy and the oral historians have veracity, Kirch and his numerous colleagues (many of whom have worked in the halls of Bishop Museum) have attempted to draft a record of the settling, populating, and developing of the Hawaiian islands prior to Western contact.

As Kirch describes, “[B]y the early seventeenth century on Hawai‘i and Maui, newly innovated cults of Kū and Lono (the Hawaiian variants of Tu and Rongo) had become central to the power strategies

of ‘Umi [a king of Hawai‘i Island] and Kiha-a-Pi‘ilani [a king of Maui], and their successors.” A rigid hierarchical system was in place. “Kū became the deity of human sacrifice, representing the king’s divine right to exercise force. The red-feathered image of Kūkailimoku (Kū, the Snatcher of Kingdoms) became the personal deity of the king. … This was the power strategy of materialization, of pomp and circumstance and ritualized display, all of which served further to widen the social chasm between the king, his nobles, and the common people.”

After initial Western contact, it took mere decades for the Hawaiian political system to fall apart. Captain Cook encountered this complex political structure, and by misjudging it, died at its hands. Hawaiians fared similarly. As had been experienced by other indigenous peoples, populations were decimated by disease, and endogenous political systems were bastardized by capitalism. This experience now goes by many names: colonialism, tragedy, progress, inevitability, and history.

Kū, the god of war, had a heyday in those years of first contact, used by Kamehameha the Great as part of his strategy of unifying

David H. Kalama, Jr. spent fifty-four days drawing the last remaining three Kū ki‘i in the world when they were on display at Bishop Museum in 2010.

“We are no less than any other culture, so why should we settle for the antiquity argument? It was contemporary human hands that did the damage. Our hands should fix it,” says cultural practitioner

Keone Nunes on the damaged Bishop Museum statue. Image by Kapulani Landgraf.

the islands. In Kamehameha’s final years, he retired to the ancient royal compound of Kamakahonu on the island of his birth, Hawai‘i Island, to practice the religion that supported his use of violence as a form of state power, which granted him rights as a god-king. When he died in 1819, the feathered gods died with him. A year later, in part as a result of massive population loss, all temple images of Kū and Lono were ordered to be burned by Ka‘ahumanu, the King’s favored consort.

It was into this traumatized, spiritual vacuum that the first missionaries in leaky ships arrived from Boston in March of 1820. The Thurstons, Binghams, and other missionary families were aghast at the sight of the various depictions of Kū ki‘i that were left, emblematic violations of God’s second commandment, that one about false idols. That Kū ki‘i were replete with carved genitals and what could be interpreted as horns made it all the worse; traditional Christian depictions of the lord have never been sexual or morally ambiguous. For missionaries and the newly converted monarchy, part of the systematic soul-saving throughout the archipelago meant but one thing for the remains of centuries of delicately carved images, the work of thousands of artisans and believers: They had to go.

“We aren’t sure how they were secreted away,” says Kahanu. To violate an order from an ali‘i in that era could mean death. The historical record is sparse. One captain’s record indicates he got a statue as a gift from a chief, which then ended up at the British Museum in 1839. The statue in Boston just mysteriously showed up in 1846. Bishop Museum’s ki‘i returned after it was likely taken as a curiosity by a missionary, a member of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM). “We do know some things about them, that they were carved between 1820 to 1840. It’s possible that there were thousands of them throughout the islands,” says Kahanu. “From accounts of the 1820s, hundreds of statues like these were burned. The only way these three survived is because they left.”

the emasCulateD goD

The themes of emasculation, and of addressing it, were big in Hawai‘i in 2010. The E Kū Ana Ka Paia exhibit coincided with the second ‘Aha Kāne Men’s Conference, where hundreds gathered to consider issues of health, wellness, and what it means to be an indigenous man in 21st century

Hawai‘i. Widely respected tattoo artist and cultural practitioner Keone Nunes was one of hundreds who participated. “It was a very important event for all of us, because it caused a self-examination,” he says in retrospect of the exhibit.