THE WAR & PEACE ISSUE

Barca Takes on GMO

DMZ Hawai‘i: In the Shadow of the Beast

In a Soldier’s Arms

Parallel Universes: Syria & Shangri La

SPRING DISPLAY UNTIL MAY 31, 2014

PACIFIC PACIFISM | 28

In the wake of the Inouye era of federal spending in Hawai‘i, editor at large Sonny Ganaden examines the relationships between the American military, tourism, and corporate interests.

I N THE S HADOW OF THE BEAST | 34

Visiting several sites of militarization around O‘ahu, Tina Grandinetti embarks on a “DeTour” with DMZ-Hawai‘i/Aloha ‘Āina, an organization that unearths the military’s heavy footprints upon Hawai‘i’s historical, social, and geographical landscape.

I N A S OLDIER’S A RMS | 41

Kelli Gratz unfurls the story of one flag that holds the weight of the bonds forged in times of war and peace and tells the tale of military heroism of a father and his sons.

PARALLEL UNIVERSES | 46

For centuries, travelers have waxed poetic about the surprising lushness of Syria, but with war raging on in the country, Shangri La collections manager Maja Clark explores how the museum’s collection of Syrian interiors may hold the key to preserving a rich cultural legacy.

A GIRL L IKE JANET M OCK | 52

In her new memoir, Janet Mock redefines what it means to be transgendered in the midst of rapidly changing societal norms, from growing up in a hostile Honolulu to finding herself in New York City.

H OLY WAR | 56

For thousands of years, war has been fought in the name of the church; at the same time, the church has been a symbol of peace. Here, a fashion editorial styled by Aly Ishikuni that acknowledges this dichotomous history of the church. Photography by John Hook.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES 4 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY JONAS MAON

PAGE 28

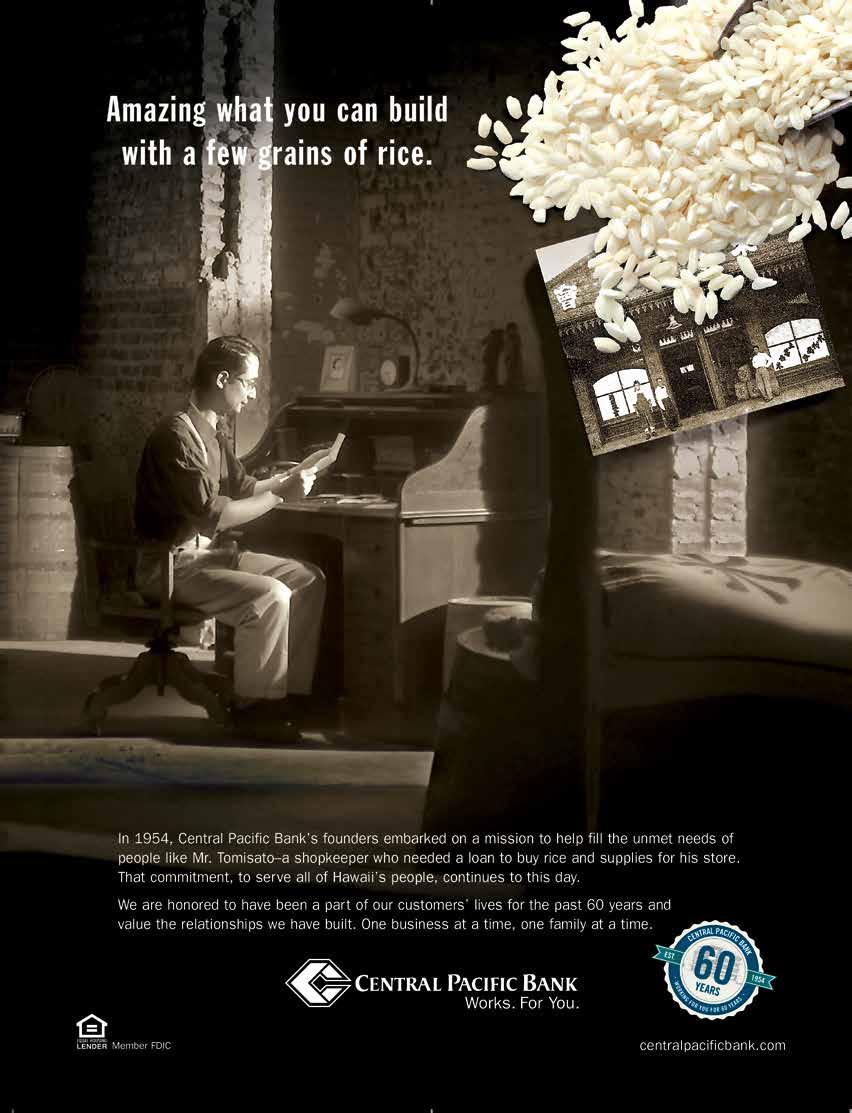

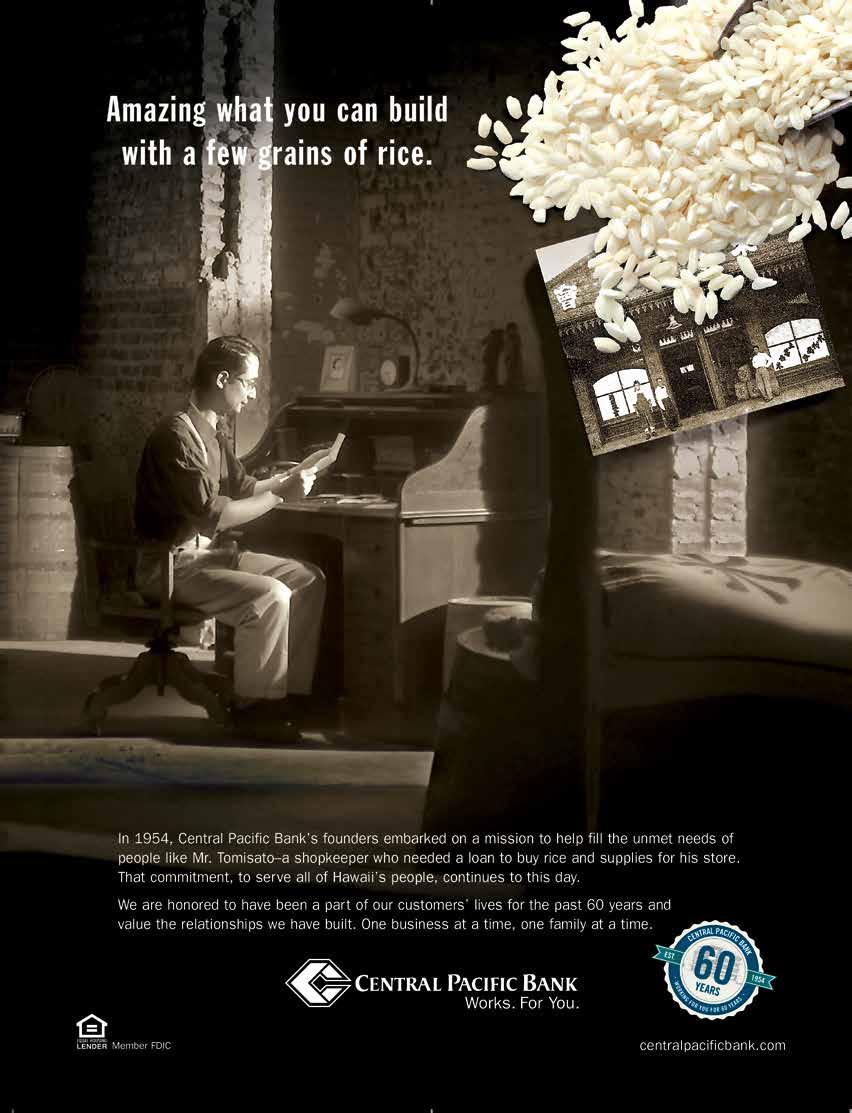

Vernadette Gonzalez’s new book Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawaii and the Philippines discusses the role of tourism in society’s general acceptance and celebration of militarism in Hawai‘i.

Kaua‘i-born professional surfer and MMA fighter Dustin Barca has inadvertently become the face of the anti-GMO movement in Hawai‘i. “I’m not a religious person,” he says, “but I feel like I’m on a mission from God.”

EDITOR ’S LETTER

CONTRI BU TORS

MASTHEAD

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

WHAT THE FLUX?! | 17

REEFER MADNESS

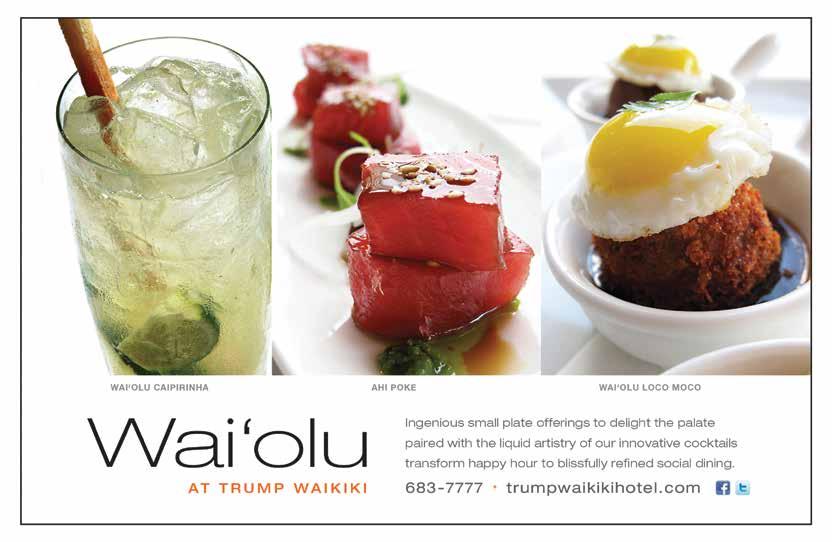

LOCAL MOCO | 21

DUSTIN BARCA TAKES ON GMO

FLUXFILES : ART | 24

TOY SOLDIER: KENNY LUI

FLUXFILES : M U SIC | 26

UNIFICATION DAY: NERVE BEATS

IN FLUX

B OOKS | 63

CHAS SMITH’S WELCOME TO PARADISE

MCC U LLY ’S TRENDIN G TRIFECTA | 66

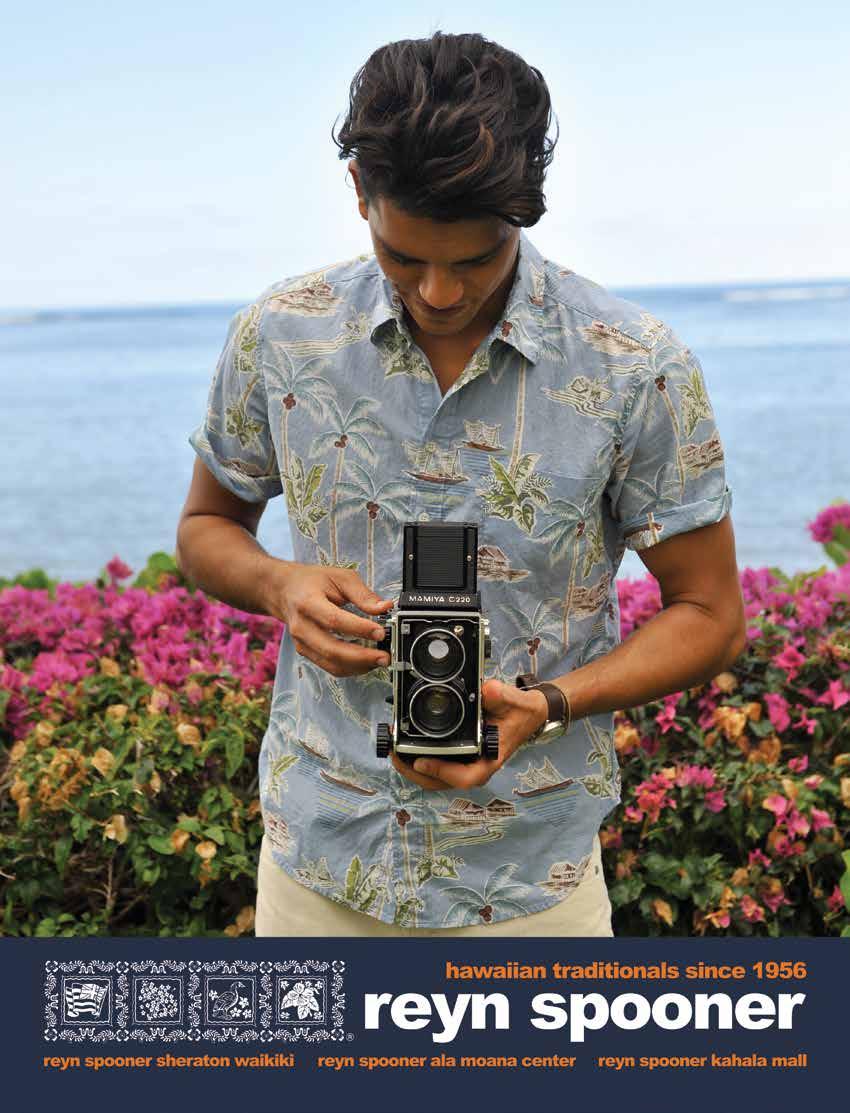

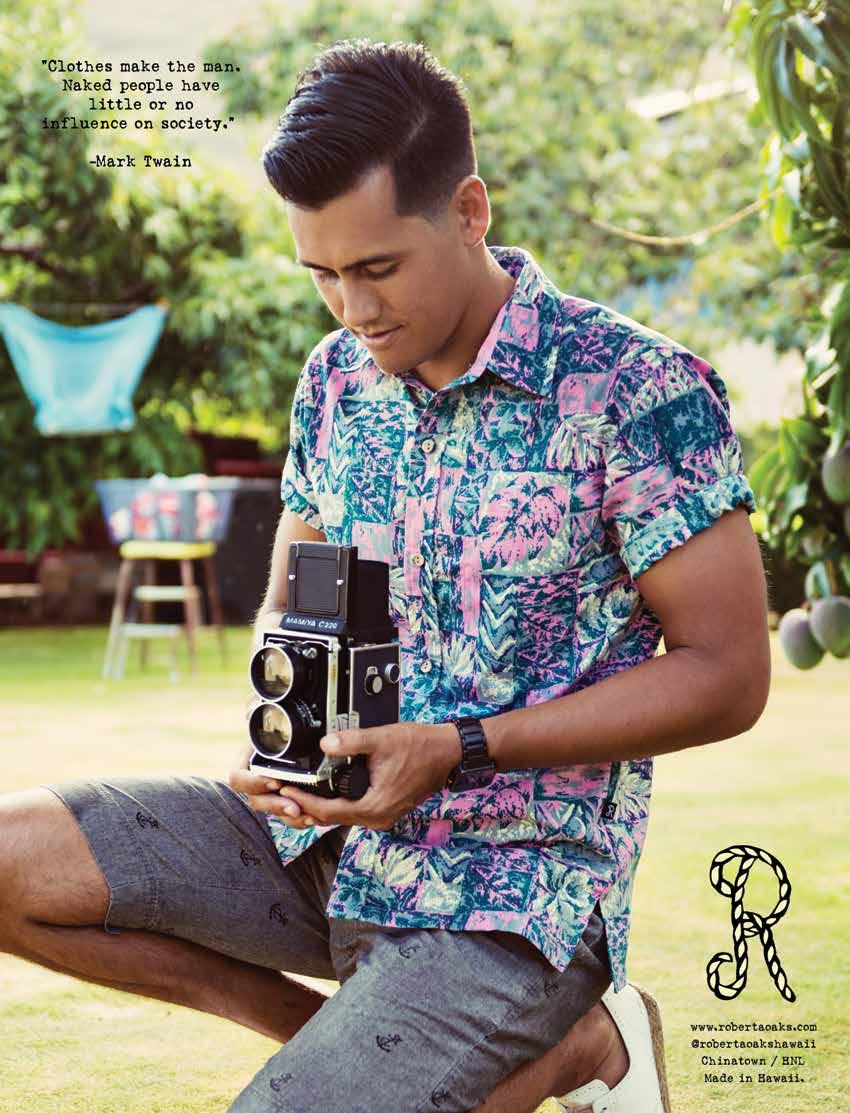

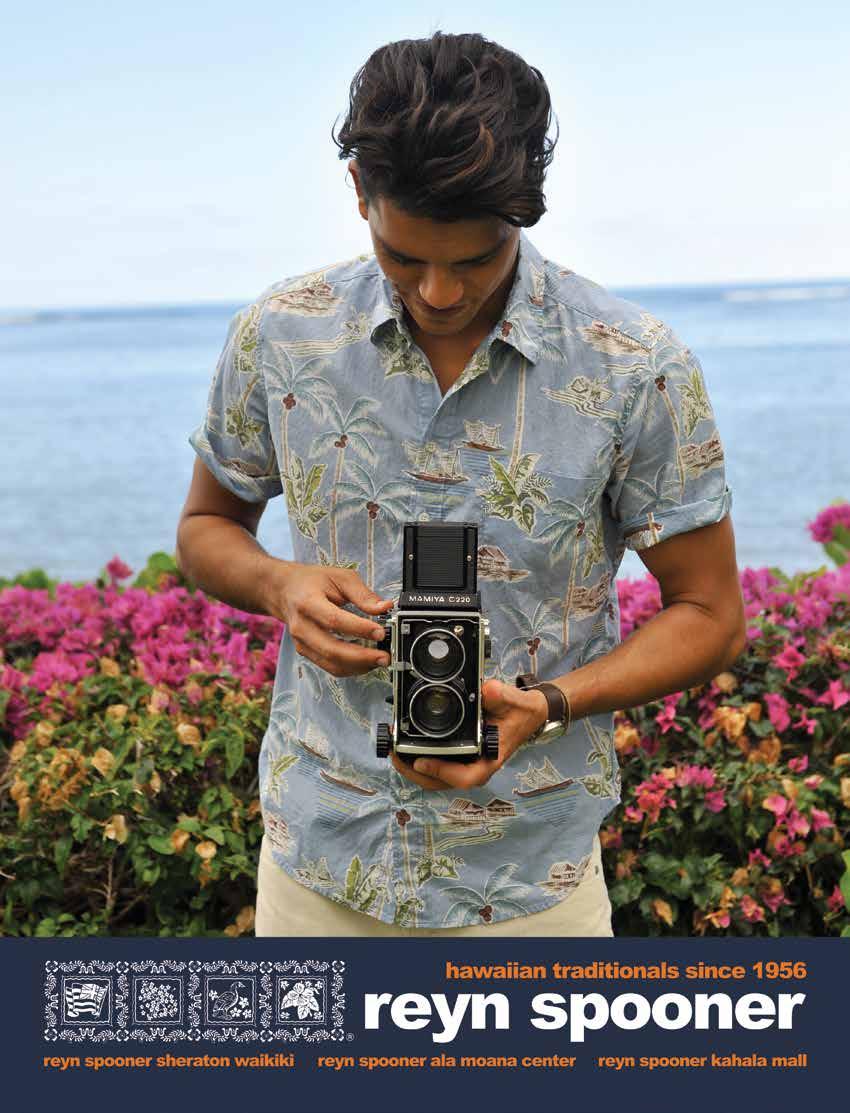

LOCAL FASHION | 68 AT THE SHOPS

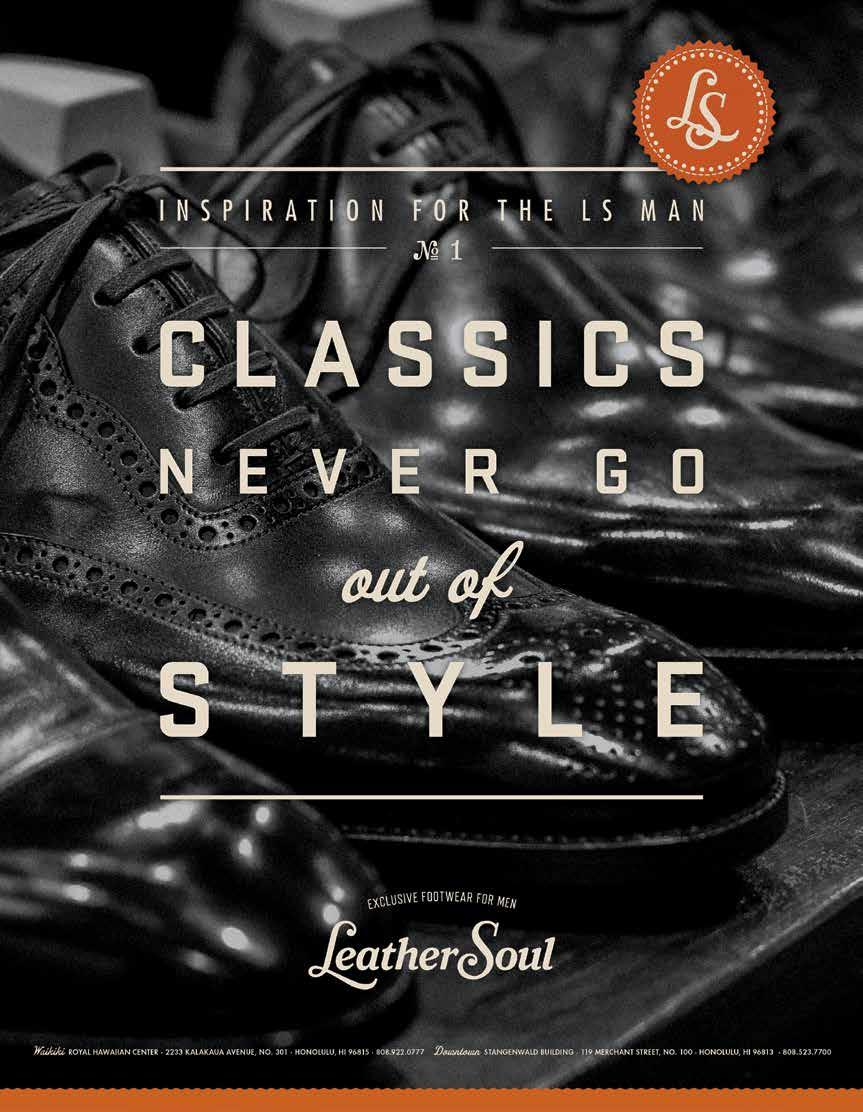

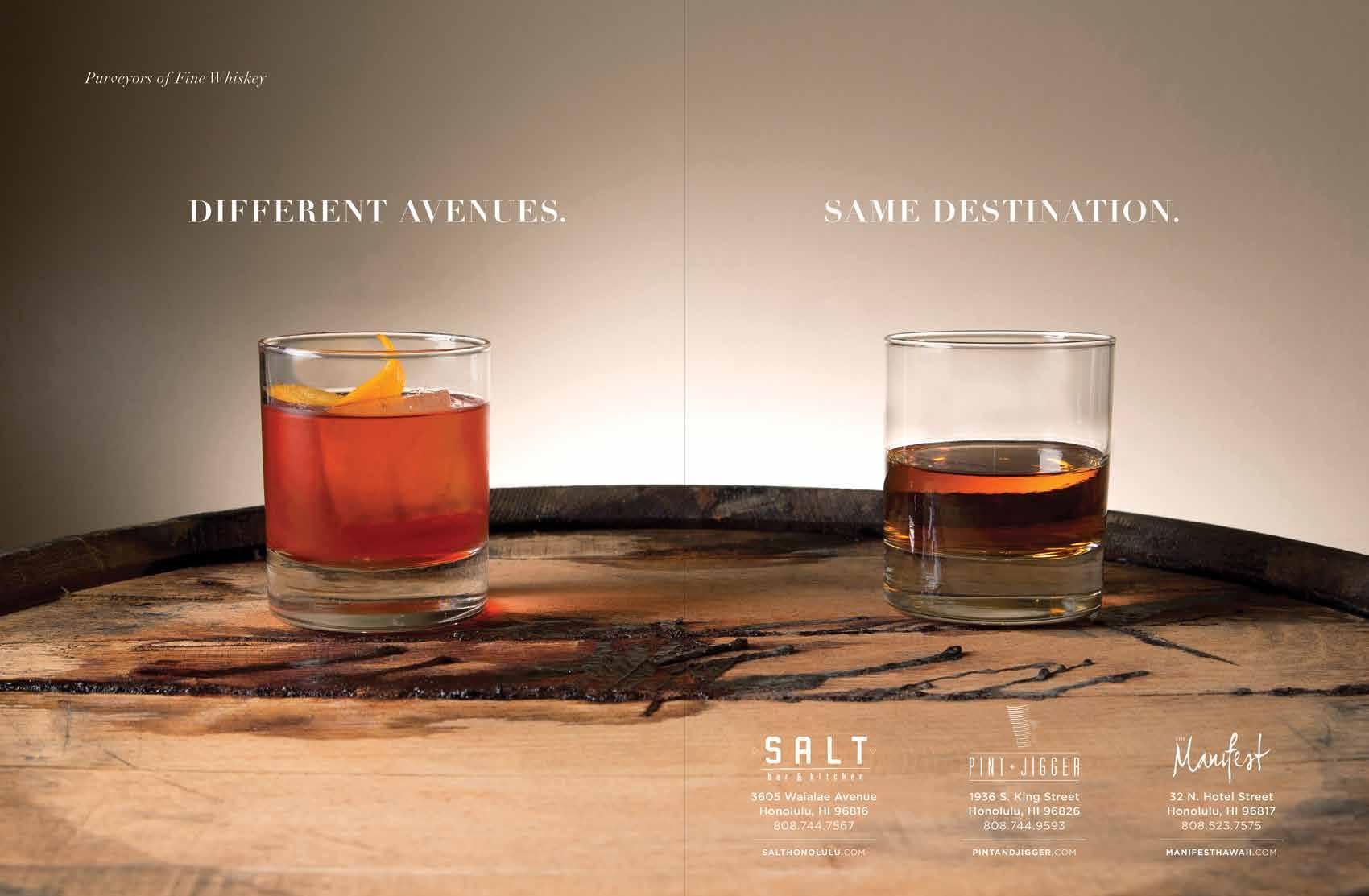

LEATHER SO U L STYLE COLU MN | 72 THE OLD FASHIONED

FOOD | 74 MW RESTAURANT

LOOKIN G B ACK | 80

TABLE

CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS 6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | IMAGE BY ANNA HARMON

OF

PAGE 21

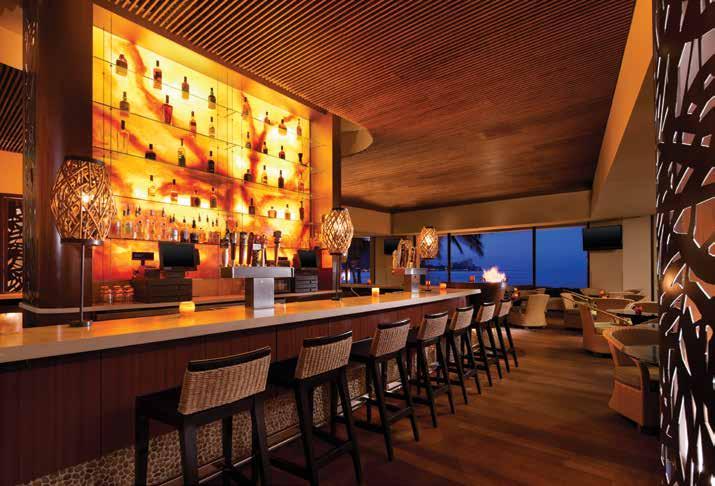

HOUND & QUAIL

Our local fashion editorial “At the Shops” (page 68) was shot at Hound & Quail, a curiosities shop owned by Travis Flazer and Mark Pei. Find out more about the shop and its owners online at fluxhawaii.com.

ON THE COVER

Photographer John Hook captured this image of Haylee Kam for a fashion editorial shot at e Cathedral of St. Andrews. Go online to see behind the scenes edits from this shoot.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FLUXHAWAII.COM 8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

FULL STORY ONLINE

WE MAY BE A QUARTERLY, BUT W E’RE BRINGING STORIES ALL THE TIME ONLINE. Stay current on arts and culture with us at: WEBSITE: FLUXHAWAII.COM FACEBOOK: /FLUXHAWAII TWITTER @FLUXHAWAII INSTAGRAM @FLUXHAWAII

for inquiries: 808.728.6143 dson808@gmail.com @dson_woodinc Wood, Inc. custom handcrafted furniture by DAE W. SON woodinchi.com

“Shame on you.”

“You are a disgrace to the LGBT community.”

“Bigot.”

e judgment of House Representative Jo Jordan in light of her vote against the passage of SB 1, the bill that would legalize same-sex marriage, was swift and without reserve. After news of the openly gay representative’s treacherous stance went viral, thousands of comments spewed in from locals and those around the nation in the comments sections of articles and on Jordan’s Facebook page, the above a few of the tamer of remarks. Some compared Jordan to the KKK or Nazis.

In the days that followed Jordan’s coming out against the bill, speculations of her motivations were made. “Was your fifteen minutes of fame worth it?” wrote one commenter on Facebook. Some accused her of being politically motivated, pandering to a religious or conservative voting public in hopes of reelection; others thought she had gone insane. Many called her a coward.

“I contemplated on standing up here today,” Jordan said in her testimony on the House floor two days after her public opposition of the bill, “because I stood up on Wednesday. See, three days ago, very few people knew me. And after I stood up on this floor on Wednesday and spoke … I became blasted. When you talk about body blows and coming with battle wounds and scars, anybody sitting or standing on this floor is not going to take what I’m going to take. … I have to be impeccable with my word, and I can’t go back now. I’m sorry to say with a heavy heart, it’s still in opposition.”

For weeks prior, the state had been divided, its people at war with each other and with ourselves. While many were entirely convinced, some were undecided. Christians wrestled with lifelong beliefs. At least one in the GLBT community was not convinced (though clearly, as evidenced by her introduction of HB 6, a measure relating to same-sex marriage, religious freedoms, and licensing, Jordan was not simply opposed to same-sex marriage).

Much of this issue, our War and Peace issue, developed as a direct response to the tensions that boiled over in the days leading up to SB 1’s

passage, but there were other issues as well that brought on this squall of intense energy. In the last few months of 2013, thousands marched in the fight against GMO; hundreds protested against development of North Shore and Kaka‘ako; dozens cried foul in what they deemed a race-based acquittal of Christopher Deedy; one took a sledgehammer to homeless shopping carts.

I don’t know Jordan, and repeated requests for an interview went unanswered. As such, I can’t presume to know what prompted her decision, or what prompts anyone, for that matter, to fight for what he or she believes in. But there is something to be said of Jordan’s action, of standing by her word in the face of public ostracism, of a consideration of the communityat-large in sacrifice of her own personal freedoms. “It’s not given to people to judge what’s right or wrong,” Leo Tolstoy wrote in War and Peace. “People have eternally been mistaken and will be mistaken, and in nothing more than in what they consider right and wrong.” We all have our battles, our own wars to wage. “We must develop and maintain the capacity to forgive,” as Martin Luther King, Jr. put it so eloquently. “He who is devoid of the power to forgive is devoid of the power to love. ere is some good in the worst of us and some evil in the best of us. When we discover this, we are less prone to hate our enemies.” War can consume a person, ensnarl one’s soul in bitterness and unforgiveness—but only if you let it.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor

EDITOR'S LETTER | 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

FLUX HAWAII

Jason Cutinella PUBLISHER

Lisa Yamada EDITOR

Ara Feducia CREATIVE DIRECTOR

SENIOR STAFF

PHOTOGRAPHER

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

FASHION EDITOR

Aly Ishikuni

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Shirley Lam

Jonas Maon

Iouri Podladchikov Toshi Sato

Daniela Voicescu

Dallas Nagata White

CONTRIBUTORS

Maja Clark

Eric Cordeiro Beau Flemister

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Anna Harmon Jeff Mull

Samson Reiny Toshi Sato

EDITORIAL INTERNS

David Jordan

Vincent Van Der Gouwe

COVER PHOTO

John Hook

BEAUTY

Dulce Apana, Timeless Classic Beauty Kayla Iwamoto, J Salon

COPY EDITORS

Anna Harmon Andrew Scott

WEB DEVELOPER Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Keely Bruns VP Marketing & Advertising keely@nellamediagroup.com

Bryan Butteling Account Executive bryan@nellamediagroup.com

Kai Rilliet

Strategic Marketing Coordinator kai@nellamediagroup.com

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock Chief Operating Officer joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne Business Development Director gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro

National Account Manager jill@nellamediagroup.com

General Inquiries: contact@FLUXhawaii.com

Published by: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

2009-2013 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii. com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

MASTHEAD |

MAJA CLARK

J OINING THE STAFF AT S HANGRI L A IN 2003, M AJA C LARK SERVES AS THE COLLECTIONS MANAGER , RESPONSIBLE FOR THE OVERALL MANAGEMENT OF ACCESS TO AND RECORDKEEPING FOR S HANGRI L A’ S COLLECTIONS , INCLUDING I SLAMIC ART, HISTORICAL AND INSTITUTIONAL ARCHIVES , AND ARCHITECTURAL ELEMENTS

It is from this unique position that Clark explores the “Parallel Universes” of Shangri La and the current crisis in Syria on page 46. Clark holds a BFA from e Cooper Union’s School of Art, a graduate certificate in museum studies, and a master’s degree in library and information science from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. She is a member of the Academy of Certified Archivists.

KELLI GRATZ

P ROWLING THROUGH Q UIRKY GALLERIES OR SCOURING MARKET STALLS IN S OUTHEAST A SIA , K ELLI G RATZ HAS A DESIRE TO SEE DIFFERENT CULTURES AND EXPLORE OFFBEAT PATHS

She returned home to Hawai‘i, where she was born and raised, after working most recently as a writer, editor, and styling assistant for Harper’s Bazaar Singapore. For Gratz, an adventure is never out of the question. In this issue, she unfurls a tale of military heroism between a father and his sons for “In a Soldier’s Arms,” page 41.

ALY ISHIKUNI

A LY I SHIKUNI IS THE COFOUNDER OF A RT +F LEA , WHICH FEATURES VINTAGE WARES AND HANDMADE GOODS FROM MORE THAN 60 LOCAL VENDORS EVERY MONTH IN THE O UR K AKA ‘ AKO AREA

e idea for Art+Flea took root when she and a few others sold off remnants of Ishikuni’s former line of deconstructed vintage mu‘umu‘mu, Mechekawa Vintage, with a garage saletype market. e University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa marketing major has a unique eye for putting together looks that inspire and evoke emotion from even the most fashiondisinterested, and did so for this issue’s fashion editorial “Holy War,” page 56.

DANIELA VOICESCU

D ANIELA V OICESCU IS A B ELGIAN FASHION PHOTOGRAPHER

She worked as a fashion model for ten years before moving behind the camera and now makes fashion, editorial, and advertising photographs. A regular contributor to Disfunkshion magazine, Voicescu’s work has also been published in Waikiki magazine, HILuxury, Estero Magazine, and FLUX Hawaii. She brought an international perspective to “At the Shops,” a fashion editorial featuring all local wares, on page 68.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | CONTRIBUTORS |

I have lived on the mainland for nearly ten years now, and when I come home I too feel like a stranger, like the New York baker you featured in the Homecoming issue. I moved to Portland because of better work opportunities (and because it’s impossibly expensive to buy a home and raise a family in Hawai‘i), but now am wondering, at what cost? It used to be that when you came home for holidays, things were always the same and people were always doing the same things. But now, Honolulu is growing at such a rapid pace—Chinatown is vibrant (though still smelly), Kaka‘ako will soon be unrecognizable (though now smelly)—I’m worried I will soon not be able to recognize the city, nor will the city recognize me. Mahalo for reorienting my perspective.

Matt Klein

Portland, OR

FLUX READE R S UR VEY

RE SULT S

After being in print for more than four years, we at FLUX are so grateful to you, our readers, without which none of what we do would be possible. After combing through the results of our reader survey, we realize how diverse our readers are. ey come from all walks of life. “FLUX keeps me aware of what’s going on out ‘there,’” wrote a 72-year-old woman from Kailua. “I’m a visual person so I appreciate the ‘simplicity’ of your magazine. ere is power and strength in FLUX without being so in your face. A class act.” A young man interested in “art,” “bodyboarding,” “hiphop,” and “living” even invited us to attend his graduation next year, where he will receive his master’s degree.

But the one thing all our readers have in common is their love of local culture. “More local designers, artists, and food sources,” wrote on reader; “local grassroots efforts and events,” went another; “keep the

#FLUXFACES

Congrats to two of our #FLUXfaces model search winners, Haylee Kam and Leilani Etherton, who are featured in our fashion editorial “Holy War,” page 56. Over the course of seven days, we received more than 500 submissions, but we are always looking for fresh faces. So if you are interested in pursuing a career in modeling, or just want to spend the day in some fabulous outfits with some fabulous people, submit a selfie and tag #FLUXfaces and @fluxhawaii.

same well-written articles that have focused on important local people and issues”—and the list goes on. But resoundingly more than anything else, readers wanted more local food stories. With that in mind, we will continue to bring you the same coverage you have come to know and love but will also be adding more food coverage, including reviews of new restaurants, recipes from local chefs, sustainable food systems, and “perhaps more food stories for those picky vegetarians,” as one young female reader suggests. We are truly lucky to live Hawai‘i. Nowhere else in the world do residents love their home as much as they do here in the islands. ank you for reading and for your continued patronage of FLUX Hawaii.

Congrats to alia Dijos who won two roundtrip tickets on Island Air for filling out our reader survey.

W ELCOME A N D VALUE YOU R FEEDBACK. SEND LETTER S TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO LI S A@FLUXHAWAII.COM OR MAIL

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM | LETTERS TO THE EDITOR | FOLLOW FLUX @FLUXHAWAII

WE

TO FLUX H AWAII, 36 N H OTEL ST., SUITE A , H ONOLULU, HI 96817.

WHAT THE FLUX ?!

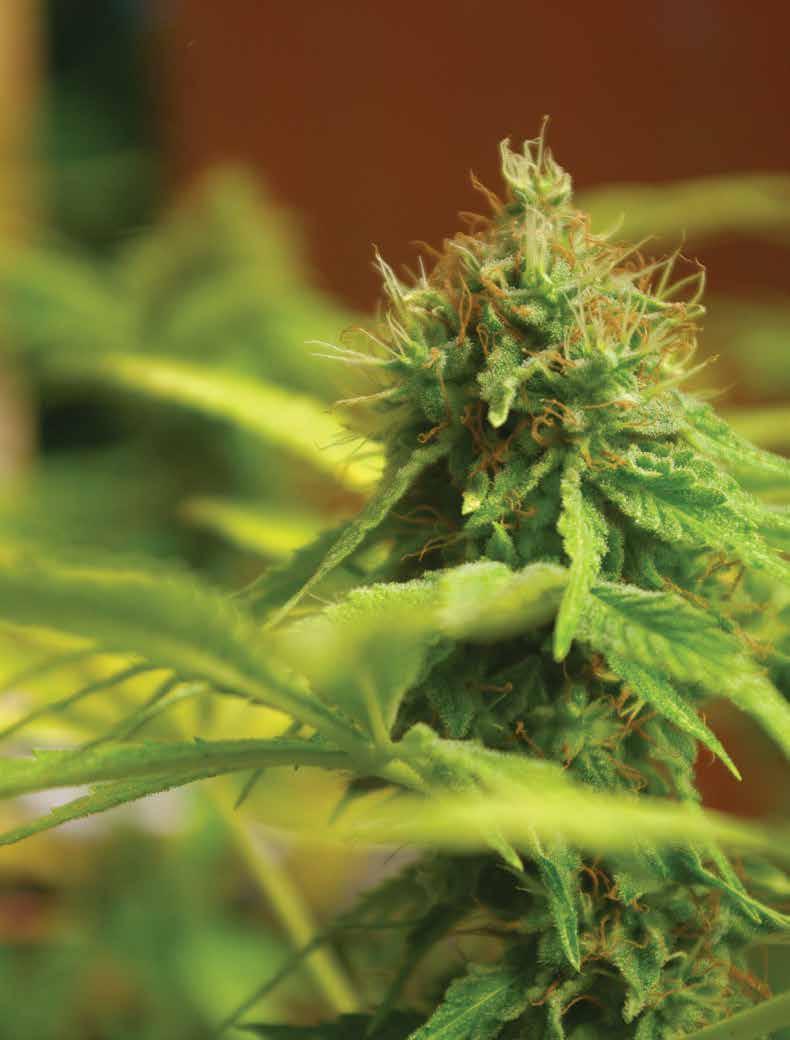

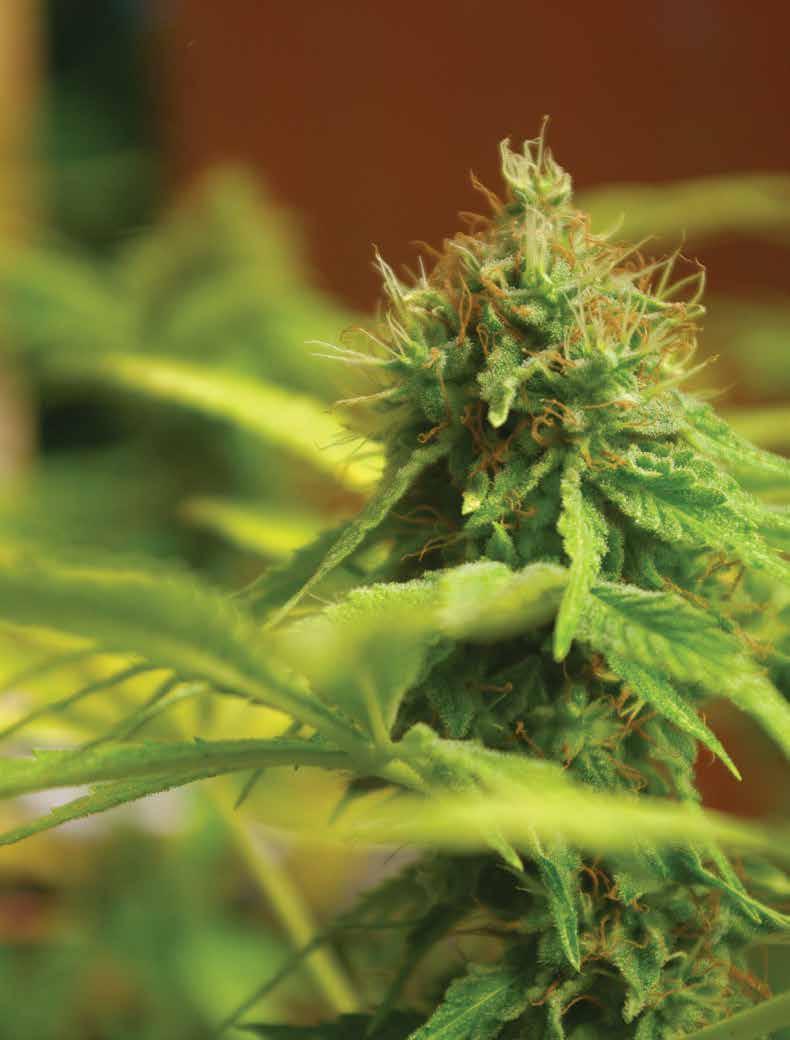

Reefer Madness

Hawai‘i has long had a love affair with marijuana. In 1978, Don Ho slurred his way to the top of local radio charts with “Who is the Lolo (Who Stole My Pakalolo?).”

In 1979, Rolling Stone called pakalolo “Hawaii’s No. 1 crop, above sugar and pineapple.” Decades later, a new generation of kids hung out in basements and garages lulled by Humble Soul’s “Pakalolo Sweet” and skanked at reggae bashes to Natural Vibrations’ “Maryjane,” the skunky cloud of smoke hovering over it all.

Today, Hawai‘i, like the rest of the nation, remains in a state of reefer madness. Last year, Hawai‘i lawmakers killed bills that would have decriminalized and legalized marijuana. While the road to cannabis legalization remains hazy, access to medicinal marijuana may become easier for the more than 12,000 Hawai‘i residents partaking in pakalolo for any one of the approved conditions (cancer, chronic pain, Chrohn’s disease, epilepsy, glaucoma, HIV or Aids, multiple sclerosis, or nausea).

Hawai‘i is among the 20 states plus Washington D.C. to have legalized medicinal marijuana, but dispensaries are not allowed, which House Speaker Joe Souki called “a gap in the law” at the opening of the 2014 legislative session on January 15. (A recent poll by QMark Research, commissioned by the Drug Policy Action Group, found that 78 percent of Hawai‘i voters support a dispensary system for medial marijuana patients). Marijuana use remains illegal under federal law, but it seems a change in the tide is underway for the first time in decades. Here is a look at some of the most fervent debate on the topic.

LIGHT UP

For the first time in 44 years, Americans favor legalizing the use of marijuana, with 58 percent in favor according to a Gallup poll (it was 12 percent in 1969, when Gallup first asked the question).

SNUFF OUT

In that same Gallup poll, 39 percent were against legalizing the use of marijuana (as opposed to 84 percent in 1969).

“Addiction is addiction is addiction.”

LIGHT UP

“With this one medication,” Missy Miller said in an article in Reuters, referring to a specialized strain of marijuana known as Charlotte’s Web, “it’s stopping their seizures or dramatically reducing their seizures.” Miller’s 14-year-old son Oliver suffers from epilepsy and experiences hundreds of seizures a day.

SNUFF OUT

“Less than 5 percent of medical marijuana users around the country have cancer, HIV, or glaucoma,” wrote former U.S. Representative Patrick Kennedy in the forward of Reefer Sanity: Seven Great Myths About Marijuana . “Marijuana destroys the brain and expedites psychosis,” Kennedy told the Washington Post in January 2013. “In terms of neurobiology, there’s no distinction between the quality and types of drugs that people get addicted to. That’s why they call it a gateway drug. Addiction is addiction is addiction.”

BLACK MARKET

ENDORSEMENT

We should not be locking up kids or individual users for long stretches of jail time when some of the folks who are writing those laws have probably done the same thing.

LIGHT UP

Proponents of marijuana legalization got their biggest endorsement when President Obama said in an article in The New Yorker: “As has been well documented, I smoked pot as a kid, and I view it as a bad habit and a vice, not very different from the cigarettes that I smoked as a young person up through a big chunk of my adult life. I don’t think it is more dangerous than alcohol. … We should not be locking up kids or individual users for long stretches of jail time when some of the folks who are writing those laws have probably done the same thing.”

SNUFF OUT

“I think that pot, marijuana for medical purposes is understandable, but I don’t think that it should be legalized for recreational purposes because it has been proven to prevent people from their full potential,” said Miss Universe 2012 Olivia Culpo to HuffPost Live. “I don’t think that’s a good thing for society. If we’re trying to move things forward, a drug like marijuana does the opposite. It will slow things down.”

Regulation is necessary to ensure that consumers are protected and that legitimate businesses have an opportunity to participate in the market.

LIGHT UP

“One of the lessons from Prohibition is that we need effective regulations. … Regulation is necessary to ensure that consumers are protected and that legitimate businesses have an opportunity to participate in the market. Regulation is a framework to support the market, not an attempt to stifle it,” wrote Garrett Peck in The New York Times.

SNUFF OUT

UCLA drug policy expert Mark Kleiman estimates the retail cost of recreational marijuana could skyrocket to between $482 and $723 per ounce as a result of regulations and taxes—58 percent higher than what it would regularly be. “That’s a big problem,” Kleiman said in an article in Forbes. “The legal market is going to have a hard time competing with the illegal market, but a particularly hard time competing with the untaxed, unregulated sort-of-legal market.”

MONIES

In Colorado, a 25 percent state tax on recreational-use pot purchases is expected to generate $67 million.

LIGHT UP

A 2010 report by Harvard economics professor Jeffrey Miron estimates the U.S. government could generate a combined $17.4 billion savings from enforcement of prohibition and tax revenues were marijuana to be legalized. In Colorado, a 25 percent state tax on recreational-use pot purchases is expected to generate $67 million. Here in Hawai‘i, a report by University of Hawai‘i professor David Nixon commissioned in 2013 by Drug Policy Action Group estimated $9 million could be redirected annually to state and county governments as a result of decriminalizing marijuana.

SNUFF OUT

Opponents of marijuana legalization refute purported monies gained from taxes on pot. “Sadly, however, we know that vice taxes rarely pay for themselves,” said Kevin Sabet, director of Smart Approaches to Marijuana, in a story on CNN. “The $40 billion we collect annually from high levels of tobacco and alcohol use in the U.S. are about a tenth of what those use levels cost us in terms of lost productivity, premature illness, accidents and death.”

1969 12% 68% 0 20 40 60 80 2014 1969 84% 39% 0 20 40 60 80 2014 PUBLIC OPINION

MEDICINAL USE

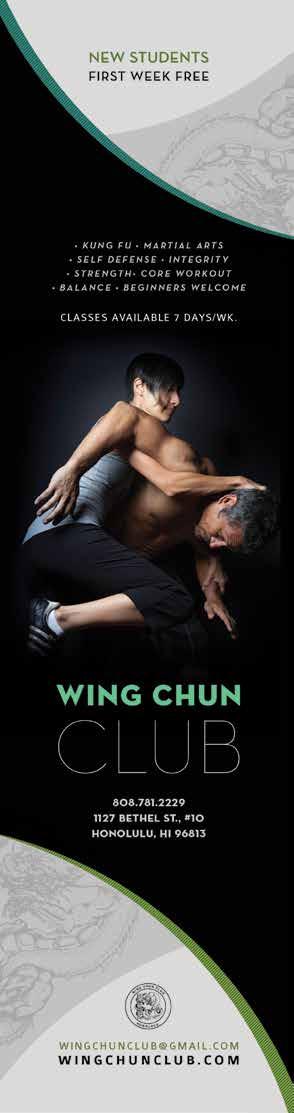

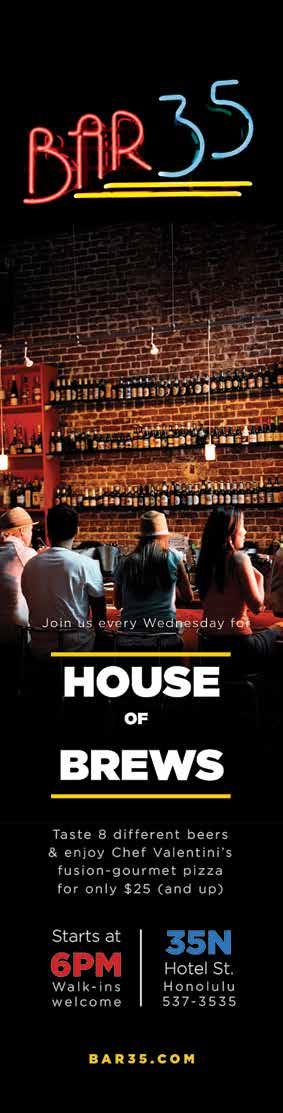

LOCAL MOCO: DUSTIN BARCA

e Kaua‘i surfer and

NNA H ARMON

fighter

takes on GMO

In December 2012, all eyes were fixed on Pipeline for the last jewel of the Vans Triple Crown, the Pipe Masters. Waves were firing, videos streaming live, thousands of onlookers crowding the beach. en, from the distance, a man approached carrying a sign, a young surfer by his side. As he walked along the water, the words became legible: “Monsanto’s GMO food poisons families.” at man was Dustin Barca. Speaking of a march he led this year in support of Kaua‘i’s bill regulating GMO companies, Barca says, “I wanted to make such a big noise that it went around the world.” And thus, the shot was fired.

In a place often called paradise, where crops can grow unimpeded by brutal cold or harsh seasons, a war is raging with direct implications for the people who call Hawai‘i home. It will determine whether we grow hardy pesticide- or pest-resistant crops that are widely exported from and possibly engineered here; if the land will be used to farm organic and sustainable food resources for its people; or if there is any way to find a safe and sane balance. ere are leaders and fighters, unconcerned and undecided, funders and instigators, but until recently, on the anti-GMO side, there have been few alliances between Hawai‘i’s people, farmers, activists, and organizations.

T

EXT BY A

| OP ENING IMAGE BY J UN J O

“ at’s been my goal since the beginning is bringing all the islands together and linking that chain,” says Barca, the 32-yearold professional surfer and MMA fighter from Kaua‘i who has unexpectedly stepped into the pro vs. anti GMO ring. Barca sees his movement as peaceful, a Ghandi-like uniting of consciousness and love to expel GMO and its corporations from Hawai‘i and move the islands toward a sustainable future. “I understand these companies, their whole thing is business numbers. I grew up in the surfing world, I know how numbers works. I know how business works. ey’re getting the most out of everything they can about Hawai‘i. It’s our job to see the bigger picture. It’s our job to see something wrong and say, ‘Hey that’s wrong, that’s not good for our kids or the future of where we live.”

As he says this, Barca is seated on a stool on the second story of the Oakley house, where he is the house manager, watching surfers catching waves at Off e Wall. As he talks, his palms are open, his elbows bent, and he swings his arms slightly, as if he’s warming up for a fight in his subconscious. On the shift from being a surfer and fighter averse to attention to being able to speak in front of thousands about regulating and expelling GMO companies, he says, “I’m not a religious person, but I feel like I’m on a mission from God.”

But it wasn’t always this way. Even from an early age, Barca was angry and quick to throw a punch. “I used to go to the police station all the time in Hanalei when I was in elementary school,” he says with a laugh. “I was a pretty bad kid. I just didn’t have a dad so I had no direction.” In tenth grade, Barca dropped out of high school. “ ey wanted to put me on Ritalin and stuff in school, and so I ended up moving to the North Shore and following my dream of becoming a pro surfer.” He became one of a handful of kids from his Kaua‘i crew, along with Bruce and Andy Irons, to make it big, but instead of establishing a name for himself for his style, he fought so much that his surf sponsorships were revoked. “At that point, I just put my head down and started

putting all my energy into surfing instead of trying to prove I was somebody,” he says. Along the way, to get in shape for surfing, Barca began taking jiu jitsu and was enamored with the humility and “the way that people carry themselves,” a stark contrast to the ego and pomp of the surf world. “ e fighting side of my life has probably helped me more than anything to become a better man and human being,” Barca says. “ e things you learn from jiu jitsu ... Every time you do it, you are rehumbled and have to leave your ego at the door. It’s the perseverance of going beyond what my mind thinks I can do.” ough MMA can be a humbling experience, it’s certainly not without its fair share of violence. His second fight ever was at the Blaisdell arena, where he pummeled the favored Hawai‘i opponent so intensely that the fight was called in the second round.

But Barca’s bout was only just beginning. In 2007, while in France for a surf competition, someone showed him Zeitgeist, an online conspiracy theory documentary. “It exposed the government and the banks and the connection between all the corruption in the world,” he says. “I went on this crazy run of information where I just went looking in the wormhole of the messed up part about our world.” at’s when GMO came into his purview. Over the next three years, Barca dug through YouTube clips, documentaries, Wikipedia sites, literature, and news. He went to rallies, became inspired by prominent activist Walter Ritte and his focus on ‘ohana, culture, and sustainability.

“Ever since I seen him talk,” Barca says, “I was like, wow I gotta frickin’ do something. What am I going to do, just sit around and watch this shit go on?”

Since then, Barca has become a leader in the anti-GMO movement, recognizable by the large megaphone he holds at events and his fighter’s stance paired with a calm intensity. He has gone from erratic posts on social media channels set up to support his surfing and MMA careers to, in 2013, coordinating March in March, which consisted of demonstrations on all five islands that GMO crops are grown (O‘ahu, Kaua‘i, Maui, Moloka‘i, and Lāna‘i). At the

march on Kaua‘i, his grandmother walked almost four miles barefoot in the rain with thousands of other attendees.

In the time since Barca has gotten involved, Kaua‘i has passed legislation that requires companies to disclose the pesticides being sprayed on crops and any experimental crops being farmed on the island, though the county is now being sued over this legislation by DuPont, Syngenta, and Agrigenetics Inc. Hawai‘i Island just passed legislation banning all GMO except for the rainbow papaya, but it is yet to be seen if this will stand.

At the most recent Pipe Masters, Barca repeated his silent walk in front of tens of thousands during the final day of the competition, blocking the view for many of Kelly Slater getting barreled. is time, the sign read, “Kamehemeha Schools Evict Monsanto.”

“Basically, [Kamehameha Schools] said, ‘find us the solution,’ so that’s what we’re doing. We’re trying to find somebody who is ready to do high level farming, or who wants to back financially a high level-farming trip. We’re working on business plans for the businesses. … We want to have all the eggs lined up for the opportunity when we have it,” he says. His personal farming dreams start with circulatory livestock farming—plots of land being grazed by cattle, rotating to chickens who fertilize the land with their feces, to organic farming the nutrient-rich soil area until it’s time to bring the cattle back. “I see a lot of my future is going to be in farming. Hopefully I don’t have to get into politics, but a lot of people want me to possibly run for mayor because my intentions are right. I think for me, the future is going to be in a lot of building sustainability in Hawai‘i.”

But all that aside, what it boils down to for Barca is this: “I’m the sorest loser—I don’t see myself losing this fight. No way.”

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Last year, Barca organized marches on all five islands that GMO crops are grown. On his home island of Kaua‘i, legislation passed that required companies to disclose pesticide use and any GMO crops being farmed.

IMAGE BY JUST N ZERN.

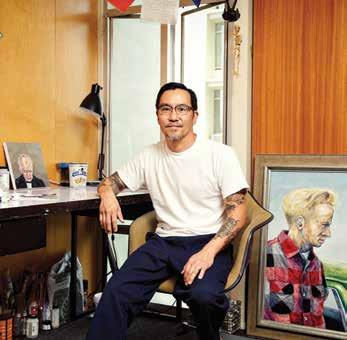

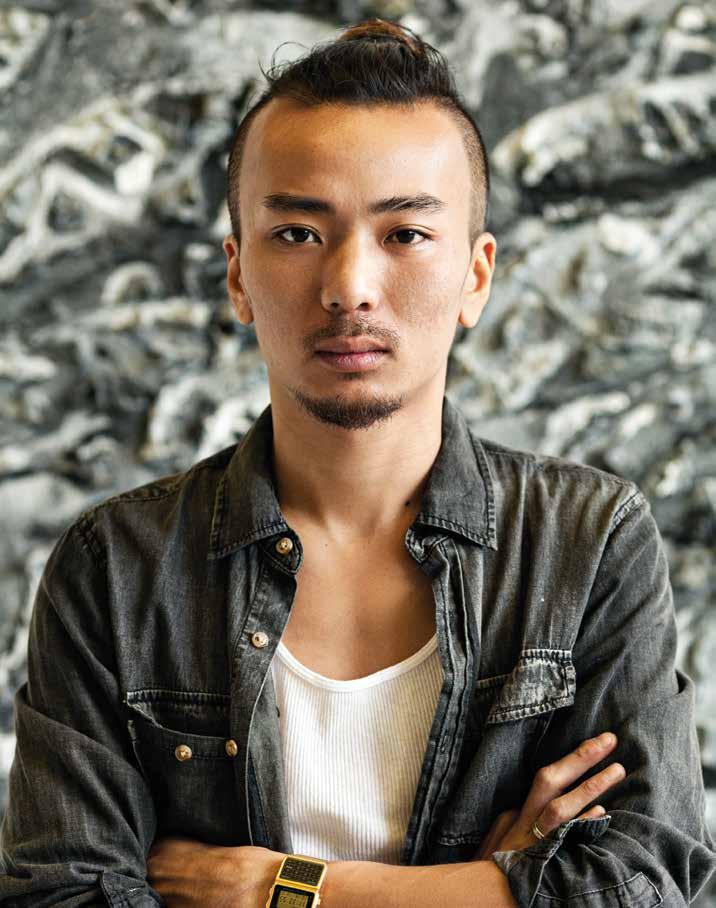

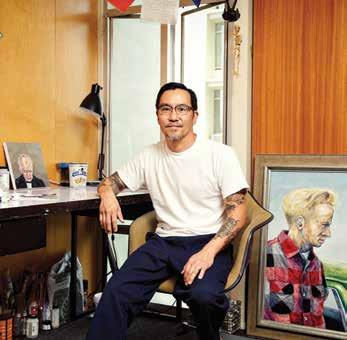

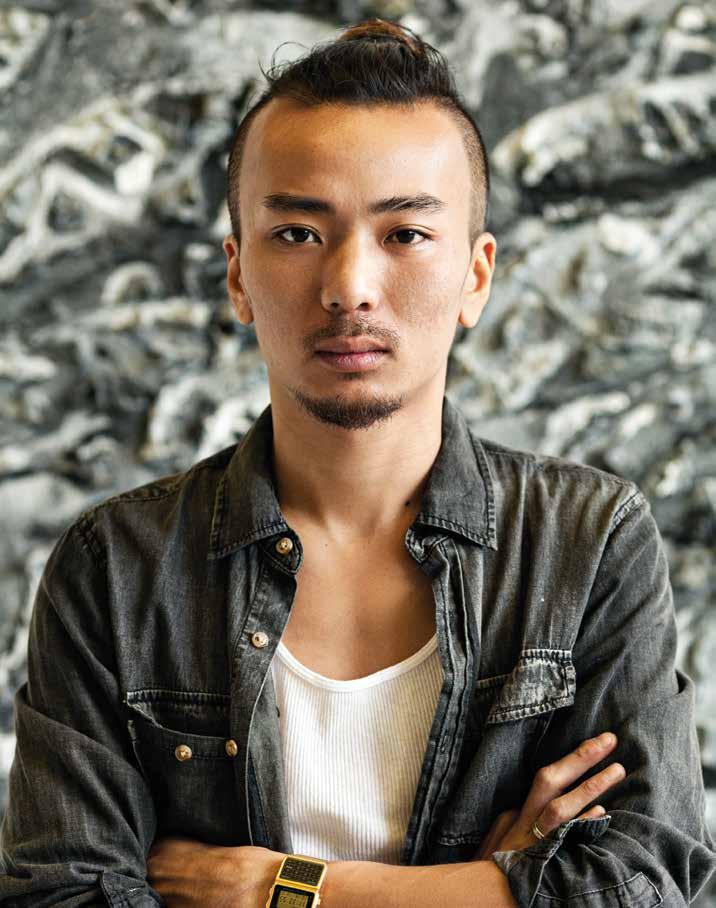

“I want to use my art to make people think about the war, and maybe myself also,” says Kenny Lui, who has been utilizing plastic Army men in his work for the past three years.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

THE TOY SOLDIER

Artist Kenny Lui

Pressed up against the plastic bag that held them, 35 little toy soldiers gazed out at the surrounding scene. From their view next to the dishwashing soap and beef sticks, they could see a half dozen Spam musubis warming under a glow of light and a lanky figure making its way toward them.

“Each time I do a project, I need at least ten bags of Army men,” says Kenny Lui, who collects the two bags remaining on the convenience store shelf. “Each 7-Eleven only has like two or three bags, so I have to make couple stops. … I can probably order them online, but when I want to do art, I just do it. I don’t plan anything.” Lui, a painting major at University of Hawai‘i, has been using plastic Army men in his work ever since he stumbled across an old can filled with them while cleaning out a storage room at Nu‘uanu Elementary three years ago.

“A lot of people have asked me if I’m from any of the war zones because I’m doing art about war,” says Lui, who’s originally from Hong Kong. “But this is just what I’m interested in. I want to use my art to make people think about the war—and maybe myself, also—and to have to feel it.” Lui says that much of his work is, however, influenced by Reem Bassous, a drawing and painting instructor at University of Hawai‘i who draws on memories of growing up in Beirut during the Lebanese Civil War in her art. Although Lui didn’t grow up near any conflict zones, his work appears forlorn, as if he’s struggling with some internal strife. From far away, Lui’s paintings appear as a wash of textures. Once up close, the shapes of the plastic toy soldiers can be made out, but they are drowned in paint, their limbs cut but continuing to grasp for something far out of reach or struggling to crawl somewhere in hopes of escape.

It’s hard for Lui to identify his reason

for being fascinated with the toy soldiers, but perhaps he sees a little of himself in each figure. Perhaps these toy soldiers are, as English novelist and pacifist H.G. Wells suggested, a way to avoid actual warfare whether in his own life or elsewhere. “How much better is this amiable miniature than the Real ing!” Wells wrote of playing with toy soldiers in Little Wars. “Here is a homeopathic remedy for the imaginative strategist. Here is the premeditation, the thrill, the strain of accumulating victory or disaster—and no smashed nor sanguinary bodies, no shattered fine buildings nor devastated country sides, no petty cruelties … that we who are old enough to remember a real modern war know to be the reality of belligerence. is world is for ample living.”

Lui will work on a large-scale painting for the 2014 Bachelor of Fine Arts exhibition at UH Mānoa, opening April 27 and on display through May 16. For more information, visit hawaii.edu/art. To keep up with Lui, follow him on Facebook /kennylui808.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25 IMAGE BY JO NAS MAON TEXT BY LISA YAMADA FLUXFILES | ART

Nerve Beats performed a onenight-only meditation on King Kamehameha’s unification of the Hawaiian Islands. A mural by Dee

shown opposite, accompanied the performance.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Oliva,

UNIFICATION DAY

Nerve Beats

“ e undering Cannon: It was during this voyage that Kamehameha witnessed the power of western weapons and began acquiring both muskets and the knowledge on how to use them. Kamehameha was not the only chief to change Hawaiian warfare with the use of guns, but no other chief used them to such great effect. ese weapons would give Kamehameha the upper hand in his entire campaign.”—Eric Cordeiro, “Unification Day, a meditation on the unification of the Hawaiian Islands”

Since forming a year ago, Nerve Beats have not wasted any time getting down to doing exactly what they want to do, how they want to do it. “ e status quo is a form of brainwashing,” says Travis Wiggins, the band’s guitarist. He, along with bassist Corby Plumb and drummer Jack Tawil make up Nerve Beats—a purposeful and recalcitrant punk trio of sorts constantly challenging themselves to resist a mental death.

Last year, over the course of 11 months, Nerve Beats composed a one-night-only performance project titled Unification Day. Inspired by American saxophonist Ornette Coleman’s “Civilization Day,” Unification Day presents the band’s meditation on specific events from King Kamehameha’s life, spanning from his birth to his successful campaign to unify the Hawaiian Islands. e 17-minute-long instrumental performance was presented at Kaka‘ako gallery SPF Projects alongside a mural created by Dee Oliva and a historical context written by this author. “ e song writing in this

band has always been nonfiction, either about artists or musicians we love,” says Wiggins. “We’ve all been fascinated with the history of Hawai‘i, so this was a way to challenge ourselves.”

e band acknowledges the sensitivity of having Native Hawaiian history interpreted through haole eyes. “While some may consider our methods arrogant or irreverent,” they write in their pamphlet explaining the performance, “[t]his is simply a way to present history … as something alive and interesting. … e sounds are meant to tell stories, portray characters and elements as well as form a narrative arc.” e entire performance was recorded and the band plans to release it online in the near future, as well as on vinyl this year.

Before Nerve Beats, all three musicians were busy putting on underground, all-ages shows or playing in other bands. “I’ve wanted to work with Jack since seeing him play in At Sea and Corby was in my favorite local band, Herbivorous Men,” says Wiggins. “After Harshist came home from tour, I knew it was time.” Tawil continues, “I know it sounds cheesy, but the chemistry was just there from the beginning.”

By using just a guitar, bass, and a three-piece drum kit, Nerve Beats produce music that combines the free jazz of Han Bennink and the revolutionary punk of e Nation of Ulysses. is relationship between free jazz and rock and roll is not without precedent. Punk progenitors MC5 played with free jazz legend Sun Ra; the dissonant sound of “no wave” (a play on

the then-popular new wave style of music in the 1970s) could not have happened without German saxophonist and clarinetist Peter Brötzmann’s Machine Gun to lead the way. “European free jazz and its radicalism was more art-focused,” Corby explains. “We draw from that but we are not the first to do it.”

is spring, Nerve Beats will release a full-length album recorded by local producer Joey Green. ey previously released an E.P. produced by Green last fall, and both releases will be put on vinyl. Recorded in Portland at e Waiting Room, the fulllength record will feature their Unification Day performance in its entirety on one side and a collection of original songs on the other. Along with the recording, the band has just completed a West Coast tour and has another in the works. “We can fit everything into the trunk of a sub-compact car easily,” jokes Tawil. is minimalist approach is both aesthetic and pragmatic. Wiggins says it best, “We jam econo, man.”

By not limiting their creativity, Nerve Beats have brought together seemingly conflicting sources of inspiration. e band seems content with doing justice to their muses and little else. “We are not conceited enough to worry about any legacy the band has,” says Wiggins. Plumb adds, “It’s not like we are doing Piss Christ or something.”

For more information, visit nervebeats. tumblr.com. To listen, visit nervebeats. bandcamp.com.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27 TEXT BY E RIC C ORDEIRO FLUXFILES | MUSIC IMAGE BY S HIRLEY L AM

With the United States military pivoting towards Asia, debates regarding Hawai‘i’s relationship to war will be renewed over the next several decades.

PACIFIC PACIFI S M

THIN K ER S IN HAWAI ‘ I CONTEXTUALI Z E

THE RELATION S HI PS B ETWEEN

AMERICAN MILITAR Y, TOURI S M , AND

COR P

ORATE INTERE S T S.

EXT BY S ONNY G ANADEN

In the wake of the Inouye era of federal spending in Hawai‘i, the United States military has a renewed strategy in the Pacific. With a pivot towards Asia, and in consideration of the Trans Pacific Partnership and forthcoming RIMPAC exercises this year, debates are renewed regarding pacifism and war—debates that have occurred at the signing of constitutions, on the beaches of Kaho‘olawe, in the arched spans of the H-3 highway, and recently at protests throughout rural Hawai‘i.

e connections between the expansive militarization of Hawai‘i, tourism, and the interests of American multi-national corporations aren’t only being made by Guy Fawkes-masked anarchists or halfbaked online conspiracy theorists but by the brightest minds in modern Hawai‘i.

eir thoughts will frame the debate of the archipelago’s relationship with war in the next several decades.

When Senator Daniel Inouye passed away in 2013, eulogies commemorated his deep concern for economic wellbeing. As the chairman of the Senate Committee on Appropriations, Inouye steered billions of dollars to the state over the long course of his illustrious career, shaping the present contours of modern Hawai‘i. “Incalculable” was the descriptor used in his obituary in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser. e savvy, quiet way that Inouye steered mass federal military investment to programs ranging from the Polynesian Voyaging Society to education is truly incalculable. Brian Schatz, hand-picked by Governor Neil Abercrombie to assume Inouye’s seat, was

given the monumental task of maintaining those investments. In the race for U.S. Senate this November, one can only hope the debates between Schatz and current U.S. Representative Colleen Hanabusa will raise the issues of perpetual military growth in the islands.

Rest assured, the U.S. military is not going anywhere. O‘ahu military installations include Navy bases at Pearl Harbor and Camp H.M. Smith, Hickam and Bellows Air Force bases, Army hubs at Fort Shafter and Schofield Barracks, and the Kāne‘ohe Marine Corps Base; Hawai‘i Island has the 132,000-acre Pōhakuloa Training Area; and Kaua‘i hosts the Pacific Missile Range Facility at Barking Sands. Together, these represent the largest collection of military personnel and equipment in the world.

According to the 2014 federal budget, annual spending across the archipelago as a result of military-industrial complex is estimated at $8.8 billion. is includes $2.4 billion in contracts for construction, supplies, and services, generating some 102,000 local jobs. In the wake of decades of opposition to the Marine base in Okinawa, as many as 2,700 Marines and their families are planned to be relocated by 2026, prompting Governor Abercrombie to offer state land and capital in Hawai‘i as a way of developing initiatives to house additional troops and minimizing Pentagon investment. is summer, for the first time in its 43-year history, the biennial Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) war games on O‘ahu will include China and Brunei along with the other 23 participating nations. Debates continue regarding the resumption of livefire training in Mākua Valley and the tons of

unexploded ordnance on the “target island” of Kaho‘olawe.

Prior to stepping down as Secretary of State last year, Hilary Clinton called this rearming a “pivot to the Pacific.” In January of 2014, admiral Harry B. Harris, head of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, called Hawai‘i the “gateway to America’s re-balancing in the Pacific” in a speech at the Hawaii Military Partnership Conference. What it boils down to is this: the containment of the military and corporate interests of China. Journalists and academics have noted a growing nationalism in Japan and China and the use of increasingly masculine language of valor, patriotism, and honor, eerily reminiscent of Western Europe a century ago and what the historian Margaret MacMillan calls “toxic nationalism.” What is truly terrifying are the threats of a 21st century Cold War and the versions of hell that go along with the rhetoric: proxy wars, mutually assured destruction, national resources squandered on preparation for battles that no one shows up to. e opposition to those 20th century realities shaped an American generation. None of this is without concern to pacifists who have voiced opposition to militarism in the islands for over a century. e history of American military is inscribed in the history of Hawai‘i and is reiterated in entire sections of state and university libraries; stories that rival anything fictionalized in Russian literature. College courses discuss the Reciprocity Treaty of 1887, in which King Kalākaua was forced to cede Pearl River Lagoon (as Pearl Harbor was called then) to the United States in exchange for duty-free sugar (the result of the aptly named Bayonet Constitution),

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 29

T

OP ENING IMAGE BY D ALLAS N AGATA W HITE

the bombing of that lagoon-turned-military base by Japan, and the expansion of that site to create U.S. Pacific Command. is expansion has quietly increased in recent years. Hawai‘i’s most recognized living pacifist, Haunani Kay Trask, addressed this in her essay in e Superferry Chronicles, which chronicled the 2007 Superferry debacle and the historical connections between the military and corporate interests that led up to it. “Euphemistically called a transformation in military documents, it is nothing less than the largest military land grab since World War II,” wrote Trask. “In terms of percentage of land controlled by the military, O‘ahu is on par with Guam, Okinawa, and other colonial military outposts.” Today, in Hawai‘i, the military controls nearly 231,000 acres—that’s 5.6 percent of total land area in the state.

“It is on the Big Island, however, that the greatest land theft in half a century is taking place under the guise of the Army’s claim that it needs 98,840 acres of ‘contiguous land’ in order to carry out maneuvers,” wrote Trask. “ e military already controls 109,000 contiguous acres at the Pokakuloa Training Area. If, and when, its long-term plans for Pohakuloa are accomplished, it will have increased its control of Hawai‘i land by almost 50 percent in one fell swoop.” e military has not yet acquired all the land it sought, but debate continues regarding the use of depleted uranium shells and the degradation of endangered species, reminiscent of Kaho‘olawe’s battles 30 years prior.

THE WAR STORIES WE TELL

Modern academics are presenting new lenses with which to view Hawai‘i’s contentious military history. After a decade of academic research, American studies professor Vernadette Vicuna Gonzales recently published Securing Paradise: Tourism and Militarism in Hawaii and the Philippines. Growing up in the Philippines and the United States, she reflects on her own youthful admiration of American valor in family trips to see military installations. “My father, a World War II buff, brought the whole family to the rotunda where MacArthur—the archetypal Joe—was buried,” she writes. “ e photograph was souvenir proof not merely of a family holiday but also of a middle-class American leisure practice that was simultaneously an

act of identification with militarized U.S.Philippine relations.”

In her research, however, Gonzalez found an entirely different picture of the American military. “Somehow, violent U.S. interventions have been absorbed into an alternative narrative of American benevolence: once-rival Japan has been transformed by virtue of nuclear annihilation, occupation, and reconstruction into a cooperative ally; the trauma of the Vietnam War is today rearticulated as an economic victory for capitalism; and the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation carries out the neoliberal dictates of Washington, D.C. in the region it comfortably refers to as the site for its ‘Pacific Century,’” referring to the ideology that the 21st century would be dominated by countries in the Asia-Pacific region.

e heart of Gonzalez’s historical analysis lies in the ways the military quite literally paved the way for tourism in the Pacific, and in that the continued presence of the military in both the Philippines and the former nation of Hawai‘i are based, in part, on the stories we recite to ourselves of valor and sacrifice at the sites of violent death turned photo opportunities. e narratives of American bravery and local death at places like Bataan and Pearl Harbor were, and still are, used to facilitate the expansion of tourist economies.

It was these narratives of martial heroics, Gonzalez argues, that former Philippines President Ferdinand Marcos (a deflective title—Marcos was in fact a dictator) used to propel his ascendancy, allying himself with the liberating Americans while smoothing out critiques of authoritarianism. In her critique, lionized Inouye does not go unscathed either. But for Inouye, of course, the history of the war was plainly seen. A folded shirtsleeve and a left handshake that crossed his body were ample reminders of what he and his peers in the highly decorated 442nd Infantry Regiment sacrificed for America.

Gonzalez also deconstructs that great, expensive victory of the Inouye era: the H-3 Freeway. “Like many colonized economies, Hawai‘i first systematically built roads to facilitate the extraction of capital,” she explains. “As a modern scenic highway distinct from territory-era roads, the H-3 was born under the joint aegis of defense and tourism [and] represented another moment in a centuries-long process of dispossession and dislocation

that was being actively contested on many fronts in the 1960s and 1970s.” at the construction of the highway took 38 years and resulted in the charting of much nearly forgotten cultural history (though that is also contested) is claimed as something of a victory for those who advocated for an adherence to the state’s requirement to document the environmental and cultural sites the highway traversed.

Gonzalez breaks down the confrontation in Hawai‘i-specific terms: “ e emergent Native sovereignty movement’s presence in the 1980s and 1990s catapulted [the H-3] into the public eye and amplified what began as a spontaneous action into a longterm occupation that prioritized indigenous cosmology as the defining term of the latest anti-H-3 action.”

In Securing Paradise, the scholarship is dogged, the coverage ample, and the index beyond reproach. But Gonzalez acknowledges that certain elements of her argument are missing, namely that of pacifism as a morality play. “It is actually the rare politician that asks, “Do you want to live in a militarized state?’” she says. “Just asking that question is a significant risk to a political career. And if you’re a political animal, to survive here, you have to be militaristic. ey see the only ways to funding as the ones that Inouye that shoveled the path to.”

PROTESTING ON THE STREETS OF KAUA‘I

e connections between anti-corporate battles and military battles are not always apparent, i.e. what does militarization have to do with genetically engineered crops? What does war have to do with labor organizing? Where Gonzalez connects militaristic influence to tourism and its subsequent effect on inequality, Christine Ahn, visiting senior fellow of the Oakland Institute and co-chair of Women DeMilitarize the Zone, relates militarism to attacks on labor and local laws that protect consumers and the vulnerable. Her main source of contention is the secretive Trans Pacific Partnership, a massive trade agreement between 12 countries that make up approximately 40 percent of the world’s economy, which the Obama administration is currently attempting to fast track through Congress.

“‘ is is not mainly about trade,’” writes Ahn in an article she titled “Open Fire and

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

At the heart of professor Vernadette Gonzalez’s new book is the way the military has paved the way for tourism in the Pacific and how its continued presence is based on stories of valor and sacrifice embedded in monuments and museums.

IMAGE BY JONAS M AON

Open Markets,’ quoting Lori Wallach of Public Citizens Global Trade Watch. “‘It is a corporate Trojan horse. e agreement has 29 chapters, and only five of them have to do with trade.’ More than 600 corporate lobbyists representing multinationals like Monsanto, Cargill, and Wal-Mart have had unfettered access to shape the secret agreement, while Congress and the public have only seen a few leaked chapters.”

Ahn amends columnist omas Friedman’s quote, “ e hidden hand of the market will never work without a hidden fist,” with her own analysis: “ e AsiaPacific Pivot, a one-two neoliberal-militaristic punch, packs both,” she writes. Cleverness granted, these high-minded political market discussions could mask how the Trans Pacific Partnership might play out around the world. It is already happening on the streets of Hawai‘i.

Over the summer of 2013, Hawai‘i Island and Kaua‘i became the surprising ground zero for the largest populist protests on the islands since the 1970s, where in the wake of the sugar industry’s demise, large agribusiness quietly took control of fertile soils to test their products. After simmering for several years, the discussion of pesticide use and GMO labeling for the public came to the fore, and residents of Kaua‘i took to the streets with handmade signs in support of a bill to disclose pesticide use, report genetically engineered crops, and create buffer zones between pesticidesprayed fields and public areas like schools, hospitals, and homes. “I do not believe Bill 2491 is the correct and legal path,” Kaua‘i Mayor Bernard Carvalho pled to his colleagues on the county council after they passed the bill. “We are not placed in these positions to be a hero or pave the way for other communities.”

Part of the beleaguered mayor’s argument was that challenging corporate interests was a recipe for diminished funds. To enforce new laws would mean admitting that the counties are doing a shoddy job of enforcing current state and federal environmental laws, in part because of egregious understaffing. e Kaua‘i county council disagreed and overrode the mayor’s veto.

In January, three of the five corporate agribusiness giants growing on Kaua‘i foreseeably struck back. DuPont, Syngenta, and Agrigenetics Inc. filed suit in federal court, claiming the Kaua‘i law unconstitutional.

e lawsuit against Kaua‘i represents more than audacity. Cases could drag out for years, taxing county corporation counsel’s ability to handle the filing, research, and cold-blooded litigation tactics of well-funded multinational corporations, forcing counties to spend untold sums on outside law firms.

It is of note that the mere threat of suit from multinational corporations impinges on democracy. is is how militaristic and corporate intimidation works at the state and local economic level—through confidential memos and concerned phone calls from the attorneys, in which democratic decisions are presented as wars of attrition more than cunning, battles over bottom lines rather than communal mores. When local leaders see themselves limited to two bad choices— to either rebuke their constituencies or to face the economic wrath of diminished federal funds or corporate power—the edifice that produces these choices needs restructuring. ese false dilemmas will continue to get people onto the streets of Hawai‘i, resetting local democracy with creativity and homemade signs. To quote Martin Luther King, Jr., “Demonstrations have a creative effect on the social and psychological climate that is not matched by the legislative process.”

Corporations did not always have this sort of power. Until three decades ago, governments could pass laws to protect citizens, the environment, and domestic firms with little threat of outside legal challenge. Corporate “rights” to sue governments for public interest regulations that may hamper their investments first appeared in little-known bilateral investment treaties. Twenty years ago, corporate lawyers embedded them in the North American Free Trade Agreement. ey now proliferate in investment agreements and even some national investment laws.

ese corporate rights are the crux of the Trans Pacific Partnership. “Yet the TPP excludes China, which has become the second largest economy in the world and is poised to outpace the U.S. economy in a matter of years—a fact that is none too pleasing to U.S. elites accustomed to unrivaled hegemony,” writes Ahn. “By increasing U.S. market access and influence with China’s neighbors, Washington is hoping to deepen its economic engagement with the TPP countries while diminishing their economic integration with China.” is integration

hits home: A significant number of goods pass through Honolulu Harbor on the way to the U.S. mainland, waters controlled by U.S. Pacific Command.

What can be missed in these numbers of troops, investments, and construction projects are the democratic choices those numbers represent. By looking to the past, skeptics like Trask, Gonzalez, Ahn, and the protesters of recent years articulate alternate choices for the future of Hawai‘i. Albert Einstein’s 20th century observation continues to have 21st century application: You cannot simultaneously prevent and prepare for war. To argue that economic aggression, inequality, and war are not intrinsically tied is to disregard the lessons of history.

A hike overlooking the Kāne‘ohe Marine Corps base on the east side of O‘ahu is an appropriate site to consider a contentious future. Ascending to World War II-era pillboxes that once held gun emplacements in preparation for potential invasion, hikers can trace the footsteps of soldiers who cleared a path to overlook the base and expansive valleys below. At one hollowedout bunker is a spray-painted American flag with Xs replacing stars. Around the flag are the names of countless locals, NonAligned Movement lovers, and passers-by, adorning the abandoned fortification with new mythology. On a surprising number of days, the Ko‘olau Mountains and the trade winds collide in clouds; slanting rays dapple the contours of the roads and trees below. As if lined by silver, the peaks rise up like old religious paintings meant to signify providence, grace, or the company of ghosts. If we continue down the same path, the future of Hawai‘i may look much like its past, a rusted bunker now the site of travel and photo opportunities, evidence of a war no one showed up to.

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 33

IN THE S HADOW OF

THE B EA S T

KY LE K A J IHIRO AND TERR Y K E K O ‘ OLANI RETRACE THE FOOT P RINT S OF MILITAR Y

P RE S ENCE IN THE I S LAND S OVER THE COUR S E OF MORE THAN A CENTUR Y.

T EXT BY T INA G RANDINETTI

I MAGES BY J OHN H OOK

“Everywhere

you look in Hawai‘i, you see the military. Yet in daily life relatively few people in Hawai‘i actually see the military at all. It is hidden in plain sight.”—

Kathy

E. Fergusen and Phyllis Turnbull, Oh, Say, Can You See? The Semiotics of the Military in Hawai‘i

e military in Hawai‘i is so ever-present and familiar that, for the most part, we no longer see it carved into the landscape and folded into our social fabric. Yet the military controls about 231,000 acres, or 5.6 percent of total land area in the state, occupying a staggering 24.6 percent of O‘ahu. Military personnel, retirees, and their dependents constitute roughly 17 percent of the population, and the military is one of our largest industries, second only to tourism. Talking about the military in Hawai‘i means talking about our economy, our patriotism, and often, our friends and family. But it also means talking about dependence, violence, imperialism, and occupation. Longtime local activists Kyle Kajihiro and Terri Keko‘olani are working to

push these uncomfortable topics into popular discourse and propel a more critical discussion of militarization through their work with Hawai‘i Peace and Justice and DMZ-Hawai‘i/ Aloha ‘Āina. (DMZ is derived from the acronym for “demilitarized zone.”) On a breezy December morning, they take me on what they call a “DeTour,” visiting several sites of militarization around O‘ahu and making visible the military’s heavy footprints upon our historical, social, and geographical landscape.

From the beginning of the tour, Kajihiro, whose unassuming smile is well recognized among the activist community, proudly traces the genealogy of their work back to the people’s struggles on Kaho‘olawe and in Kalama and Waiāhole-Waikane in the 1970s. Keko‘olani, affectionately called “Auntie Terri” by many, was a member of the fifth landing on Kaho‘olawe— she acted alongside other kanaka maoli (Native Hawaiian) activists in direct defiance of the U.S. military. “ e whole idea of a beautiful island like Kaho‘olawe devastated by bombing over almost 50 years,” she says, “brought me into this whole thing of, ‘Why does the military have this power and the ability to destroy islands?’”

| FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

Longtime activists Kyle Kajihiro, Terry Keko‘olani, and Andre Perez are bringing to light the military’s effect on Hawai‘i’s historical, social, and geographical landscape.

We don’t come here to disturb their stories but to remember that all of Hawai‘i su ff ered that day and to imagine a future where this can be a memorial for peace rather than war.

THE SCENE OF THE CRIME

e first stop on our tour is ‘Iolani Palace, standing stoically amidst the morning rush in Downtown Honolulu. “We come to the ‘Iolani Palace to talk about this as the symbolic heart of Hawai‘i’s sovereignty, and also as the scene of the crime, where the overthrow took place,” says Kajihiro.

On the lawn, under the shade of a towering tree, Kajihiro points to the building’s western facade, telling how King David Kalākaua built the extravagant palace, complete with electricity, to demonstrate that the kingdom was a modern, civilized nation in an age when imperialism was devouring much of the world. He recounts the unfortunate course of political events that led to the overthrow: the Reciprocity Treaty of 1875, which allowed sugar to flow tariff-free to the United States and cemented Hawai‘i’s ties to the United States; the Bayonet Constitution, which increased the power of the white minority while disenfranchising Asian immigrants and poor Native Hawaiians; the second Treaty of Reciprocity, which granted the United States exclusive use of Pearl Harbor; and finally, the coup d’état that stole Lili‘uokalani’s crown, imprisoned her within the palace walls, and began an illegal occupation that continues today.

Kajihiro points toward Mililani Street, where troops from the USS Boston marched to from Honolulu Harbor and aimed Gatling guns at the palace, providing

the muscle for the overthrow. “ at was the beginning of the broken relationship between the U.S. and Hawai‘i,” says Kajihiro. “Now there was a military act that violated Hawai‘i’s sovereignty in order to support a regime change.”

Before we leave, Keko‘olani flips through a binder she brought with her. In it, there is a photo of her great-great-grandfather Charles Peleohalani Keko‘olani and his signature, among thousands of others, scrawled onto an 1897 petition against the annexation of the Hawaiian Kingdom. When talk of annexation spread across the islands after the overthrow, the people of Hawai‘i launched a petition, gathering over 38,000 signatures, accounting for 90 percent of Hawaiian nationals. e Kū‘e Petition was hand-delivered to Washington D.C. and succeeded in blocking Senate ratification of the pending Treaty of Annexation between the United States and the provisional government. “ e people, and my own ancestors, were successful with the Kū‘e,” says Keko‘olani. Of course, success was short-lived. Without any kind of formal agreement to prevent annexation, the islands were seized in a unilateral— and thus illegal—decision by the United States. Over the course of a century of Americanization and assimilation, the memory of the petition and the people’s resistance was forgotten—until University of Hawai‘i professors Noenoe Silva and Nalani Minton brought copies back to O‘ahu in 1998.

As we pass a Japanese tour group snapping photos of the palace, Kajihiro adds, “ is is the big lie we’ve been told growing up in Hawai‘i; that Hawai‘i willingly became a part of the United States. It all hinged on a military action.” Looking back towards the palace, he adds, “ ose guns that landed in 1893 have only morphed into all the warships and drones and bases, everything else that we have in Hawai‘i today.”

THE HE‘E OF U.S. IMPERIALISM

Our tour continues up Halawa Heights to a large but rather inconspicuous building perched along the ridge behind a barbed wire fence: the headquarters of the United States Pacific Command, the oldest and largest of the unified military commands projecting U.S. power and interests over the Pacific. Senator Inouye, champion of Hawai‘i’s military economy, appropriated $90 million for the high-tech building, which oversees a region encompassing 36 countries, half the world’s population, and one-third of U.S. trade. From here, we can see Pearl Harbor in its entirety, fingers of water running across a wide, flat plain.

“Kalekoa Kaeo [a Hawaiian Studies professor and activist] likens the military to a giant he‘e (octopus). e PACOM headquarters are its brain, its nervous system,” says Kajihiro as Keko‘olani holds up a map of the PACOM region. “ e NSA station in Wahiawa is one of its many

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

Kyle Kajihiro and Terry Keko‘olani, shown in front of the giant “golf ball” radar that sits at Pearl Harbor, liken the military to a giant he‘e, or octopus, whose tentacles stretch over Hawai‘i and across the Pacific.

Kyle Kajihiro and Terry Keko‘olani, shown in front of the giant “golf ball” radar that sits at Pearl Harbor, liken the military to a giant he‘e, or octopus, whose tentacles stretch over Hawai‘i and across the Pacific.

Behind Leeward Community College, Andre Perez’s Hanakehau Learning Farm juxtaposes the negative impacts of militarization in Hawai‘i with a hope for the future.

Behind Leeward Community College, Andre Perez’s Hanakehau Learning Farm juxtaposes the negative impacts of militarization in Hawai‘i with a hope for the future.

eyes.” Its tentacles stretch far beyond the harbor below us, farther than Schofield Barracks in the distance or Mākua Valley on the other side of the Wai‘anae Range. PACOM’s tentacles reach out to Pōhakuloa Training Area on Hawai‘i Island. ey are wrapped firmly around Guam, where the U.S. military controls one-third of the territory, and extend to Okinawa, where massive protests have been held in opposition to the U.S. military presence. ey penetrate New Zealand-Aotearoa, where peace activists used a sickle to puncture a large, white golf ball radar station, like the one sitting in Pearl Harbor. ey entangle the Republic of the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, the Philippines, South Korea, and hundreds of other locations. All of these places benefit economically from the U.S. military presence but hold a long list of grievances as well including environmental contamination, land struggle, violence and crime around military bases, and economic dependency.

“Small places become important for projecting power,” says Kajihiro. “ ey are easy to maintain and dominate without the friction of resistance.” And the military does indeed dominate here in Hawai‘i, where it is nearly impossible to imagine an economy void of the billions of federal dollars brought here by defense spending. As America’s gateway to Asia and the Pacific, Hawai‘i projects and protects U.S. power and interests across the globe, tying those diverse struggles intrinsically to our islands.

THE BELLY OF THE BEAST

At Pearl Harbor, the quiet, formal air of PACOM is replaced by a chattering rush of aloha shirt-clad tourists. “At one point we decided that at the heart of the issue is Pu‘uloa, Pearl Harbor,” says Kajihiro, “and that we had to unlock that story and sort of explain how it has a grip on Hawai‘i and our imagination about this place.” As we walk along the manicured waterfront path, Keko‘olani, whose grandfather received a purple heart as a firefighter on the day of the attack, says softly, “When we come

here, we always remember and respect the people who lost their lives on December 7. We don’t come here to disturb their stories but to remember that all of Hawai‘i suffered that day and to imagine a future where this can be a memorial for peace rather than war.”

We pause at a bronze model of O‘ahu placed at the center of an elegant stone circle that subtly echoes our voices. Kajihiro and Keko‘olani call Pearl Harbor by its oft-forgotten name, Ke Awalao o‘ Pu‘uloa, or “the many waters of the long hill.” e syllables reverberate as we repeat them together with a few curious tourists. Not long ago, Ke Awalao o‘ Pu‘uloa was the breadbasket of O‘ahu, a fertile estuary supporting as many as 36 fishponds. We run our fingers over the model of O‘ahu, feeling the dips and valleys of the watershed that runs into the harbor. At its most productive time, Keko‘olani tells me, “the fishponds of Pu‘uloa made the land momona (fat) and brought a time of peace to O‘ahu.” Since nearly the beginning of the United States’ relationship with Hawai‘i, however, Pu‘uloa was eyed as a valuable military asset. e drive to expand U.S. naval power across the Pacific through the exclusive use of Pu‘uloa was met with deep resistance from Hawai‘i’s people and was among the factors that led American interests to force Kalākaua to sign the Bayonet Constitution under the threat of violence, thereby setting the stage for the overthrow.

Today, Pearl Harbor is toxic, a Superfund site with more than 700 individual contaminated sites (though you can still find some impoverished families fishing its waters beneath signs warning of contamination). “We don’t even think about the days when Pu‘uloa provided food for us, but imagine if it could still do the same today,” says Keko‘olani. is legacy of enclosure and abuse of the ‘āina is perhaps one of the most contested and challenged aspects of the military in Hawai‘i. Resistance movements have fought military expansion on Kaho‘olawe, where 50 years of bombing have made 90 percent of the island inaccessible; in Mākua, which remains littered with

unexploded ordinances; in Pōhakuloa on Hawai‘i Island, a live-fire training area saddled between Mauna Kea, Mauna Loa, and Hualalai; and in Waikane, where residents waged a battle against proposed jungle warfare training in 2003.

Finally, we reach the building that houses the recently revamped museum exhibit. Wartime music plays on surround sound, punctuated by sounds of gunfire and explosions. We walk past interactive video displays, photographs, and countless replicas of weaponry. e exhibit originally told a largely Navy narrative of sneak attack and eventual triumph, but when the museum was redone in 2010, it conveyed a more inclusive narrative accounting for the perspective of local people who shared in the trauma of that infamous day and addressed the American bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. “Still,” says Kajihiro, “certain perspectives are privileged, while others are marginalized.” A new section was added to tell the Native Hawaiian story. When we walked past the displays, they were physically blocked by people seated on benches immediately in front of the placards, a reminder that those most heavily affected by the military are still largely ignored by it.

THE FUTURE: KU‘E AND KUKULU

In Waiawa, behind Leeward Community College, just a few steps from the waters of Pu‘uloa, we find a dirt road driveway marked by a faded Hawaiian flag waving in the warm breeze. At the end of the driveway are the beginnings of a small farming venture: a row of young coconut trees, some vegetables, a few chickens, papaya trees, an emerging lo‘i kalo, and an ahu (stone alter or shrine) nestled in one corner of the property. Every demilitarization tour ends here, at Hanakehau Learning Farm, where Native Hawaiian activist Andre Perez is working the land and seeking to provide a place of community and action for his people and lāhui (nation). “ e purpose of ending here at the farm is to juxtapose the negative-impact experience of the tour with hope for the future,” says Perez, “and to show that despite heavily

I strategically fight and protest against things like militarization, but now I realize that it’s equally important to fight for things, to build and create things that are meaningful, longlasting forms of power.

militarization, there are kīpuka (variation or change of form, as an opening in a forest) of change for reclaiming and restoring of the Hawaiian lands.”

Perez’s story is important to the narrative that DMZ-Hawai‘i/Aloha ‘Āina strives to tell, because his life, like many other Hawaiian men, at one point included military service. After graduating from high school, Perez was accepted to University of Hawai‘i at Hilo but couldn’t afford to attend. e military offered a way off the island and a path toward financial security, so Perez enlisted and served eight years. “I wasn’t aware of U.S. imperialism, capitalist agendas. I just did my job. I hung out with a hardcore group of Hawaiian guys and local braddahs. e biggest motivator in the military is the loyalty and camaraderie with your buddies.” Roughly 54 percent of the military-controlled land in the state rests on the crown lands of the Hawaiian nation, and Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders are dramatically overrepresented in the United States military. “We’re at the bottom of the socio-economic ladder—it funnels us into the military,” says Perez, who worked on counter-recruitment efforts with Kajihiro in local high schools.

Upon his discharge from the military, Perez spent three months on the beach in Wai‘anae. at time was really significant for me,” says Perez. “I saw real struggle and survival amongst Hawaiians. Entire families are living on the beaches in

tents and shanties, houseless in their own homeland while military personnel get free housing on our land. Military personnel living off-base also drive up the rent for local people. Oftentimes, owners would rather rent to military personnel because they can pay more.” In Wai‘anae, living out of his truck, he says, “I went through a pretty quick decolonization process. I started to see the contradictions.” In 1998, he applied for a job as a live-in caretaker on Kaho‘olawe, and spent the next seven years rehabilitating the land from a halfcentury of military bombing.

On Kaho‘olawe, Perez worked on native-plant resotoration and met key leaders within the Hawaiian community. “ rough my connections on Kaho‘olawe I got to meet my mentors. It threw me right into this mix of cultural practitioners and activists. I got to know all of them.” Among them were activists like Skippy Ioane and Palikapu Dedman, who, like him, had served in the military before becoming leaders within the Hawaiian community. “A conscious vet is a powerful activist,” says Perez. “If you want to experience elements of American racism, you can find it right in the military. A good part of the military is poor, disenfranchised people of color. It’s a way to provide for their family and contribute to society, but it’s not hard for them, and for us, to see the contradictions.”

When Perez finally decided to leave

Kaho‘olawe and return to O‘ahu, he became active in the movement for Hawaiian sovereignty. “Kaho‘olawe was a springboard that taught me that there was more,” he says. “If you’re gonna talk about militarism and demilitarism you cannot talk about it without talking about sovereignty and the occupation.” As he looks out upon his three-acre plot, Perez talks about the balance he has struck between kū‘e, meaning “to oppose or resist,” and kukulu, meaning “to build.”

“I strategically fight and protest against things like militarization, but now I realize that it’s equally important to fight for things, to build and create things that are meaningful, long-lasting forms of power.”

Hanakehau Learning Farm represents, perhaps, an image of what awaits us on the other side of demilitarization. Alongside potted kalo awaiting a home in the lo‘i still being dug out of the earth, his kids’ trampoline stands in the red dirt. “If I create somewhere like this, I create a space we control,” he says, “a little kīpuka of Hawaiian critical consciousness that is in the shadow of militarization, in the belly of the beast, but serves as a beacon of hope for the future.”

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

IN A SOLDIER’S ARMS

One flag holds the weight of bonds forged in times of war and peace.

EXT BY K ELLI G RAT Z

At night, artillery units would fire rounds of parachute flares, popping them free of their aluminum tubes. ere were millions of them. Illuminating the night’s sky, they would eventually litter the ground and sea. Under the glow of the harvest moon, a pair of hands found me, one of the millions of flares, and cut my round edges along four straight lines; the gold fringe and plastic stars were sewn on later. White linen, stained red and blue—these are the colors I bear. e colors of justice, freedom, and equality. e colors of war and bloodshed.

e 19-year-old trained combat medic hadn’t been in country for a month when he wandered into the shop. I remember the day he came in. He stood tall, his breathing loud and arms folded. ey called him “Doc.” He sounded excited—pleased with having found something he recognized. Minutes later, we were out the door, the warm waves of wind pulling at my loose threads. We didn’t know it at the time, but I would later carry the souls of his loved ones in my arms. ey would lay outstretched in my lap, and rest their heavy heads on my shoulders.

PORTRAIT

T

IMAGES BY J OHN H OOK

Clockwise from top: Battle flag flies over Que Son Valley, Vietnam, July 1968; Nainoa wearing dad’s 25-year-old uniform, 1991; Allen having morning coffee on Dragon Base, Que Son Valley, February 1968; Nainoa’s Ranger graduation, Fort Benning, Georgia, March 2004; deployment ceremony, Fort Lewis, Washington, September 2004; Nakoa heading out on a convoy escort mission, Iraq, 2009.

“I was on a convoy and I wanted to buy something for my mom for Christmas, so we stopped at a random shop on Highway 1 on the coast of the South China Sea in the province of Quang Tin, in what was known as I Corps,” Doc said. “I saw a Chinese-looking brocaded vest, and then I saw it. I had no thoughts about what I was going to get. I bought the flag.”

Before Doc, I had never seen death. en the explosions started. e rockets, the mortar. It sounded like a wave moving from the land to the sea. It was January 1968, and communist forces of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army launched the Tet Offensive, a series of surprise attacks that would turn into one of the largest military campaigns against South Vietnam and the United States. e first phase began January 31, 1968. irteen cities in central South Vietnam were under fire that morning. A hundred more cities would follow. e first of my threads unraveled that day and continued to spool out over each foot of ground we walked. “ at year, 15,000 Americans were killed. It was the bloodiest year,” Doc said. “It marked a turning point in the war.”

Five months later, on Mother’s Day, two NVA troops advanced into an old French fort at Ngok Tavak, a forward operating base straddling the western jungle of Vietnam and Laos. A small group of marines were securing the area and conducting reconnaissance while a Special Forces camp a few kilometers north in Kham Duc evacuated. Guided by the waning midnight moon, Doc and his fellow soldiers of the Recon Team Snoopy, 2nd Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment defended themselves from the NVA as they threw exploding satchel charges and opened mortar fire.

“ ose of use who survived the battle, we had this commitment to each other to never forget and to do whatever we could to help the families of those who died in combat,” Doc said. “For 40 years, they had no

clue. e army’s position was that they were missing. But we knew, and so we had this duty to stay in touch, and once their bodies were found, to go to their service and present the flag.”

I’ll always remember the color: the earth, a dark red, stained by the blood of 13 Americans. Among the Ngok Tavak’s survivors was Doc, who had followed the burnt path of a napalm strike until reaching a safe location where helicopters would take him to the Special Forces camp at Kham Duc. I wrapped around him tight as he waited, holding a radio close to his chest. e voice of first lieutenant Fred Ransbottom came through the speakers. “We’re all wounded. We’re killing them as they come through the door.” at was the last thing he heard from his men.

I carried two souls out that day, one in each arm. e first was Fred; the second was Skip Skivington, Doc’s best friend. I would return almost 38 years later to the Kham Duc battlefield with Bill Wright and Dickie Hites of the Joint Prisoners of War, Missing in Action Accounting Command, where they would find remains of the fallen buried under layers of ash and dirt. at night, as I looked toward the sky, I saw the moon eclipsed, first full and bright, then shadowed by a slow blink. It was the first time I saw Kealiihokuhelelani, the chiefly moon that travels the heavens.