FALL 2014

36

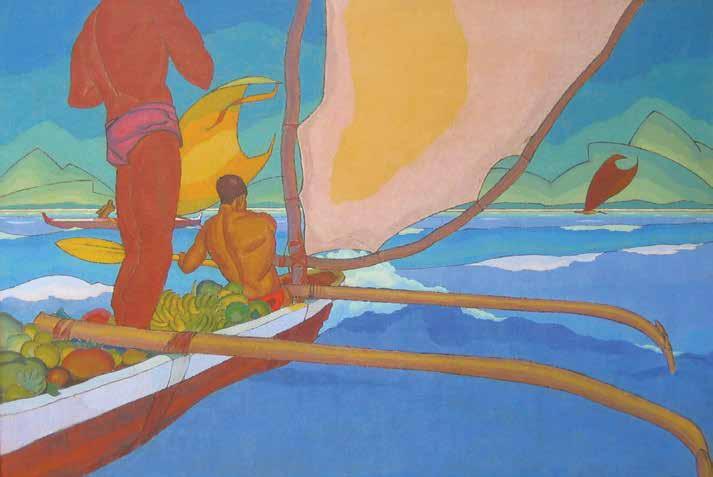

STARSHIP HAWAI‘I

Less than two centuries ago, Hawai‘i was a sovereign nation. Community discussions during the last year indicate that it may one day regain that status, but many questions remain. Editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden wonders, does Pacific science fiction have the answers?

TABLE

OF CONTENTS | FEATURES |

44

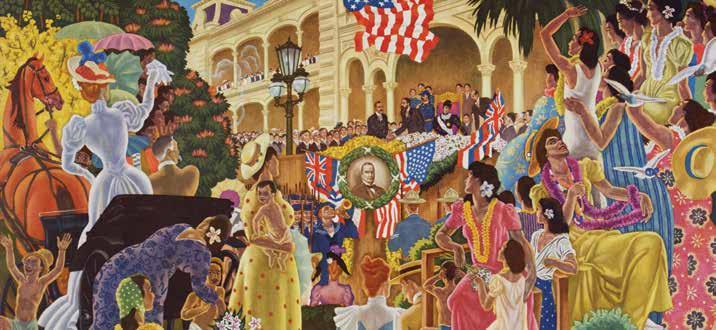

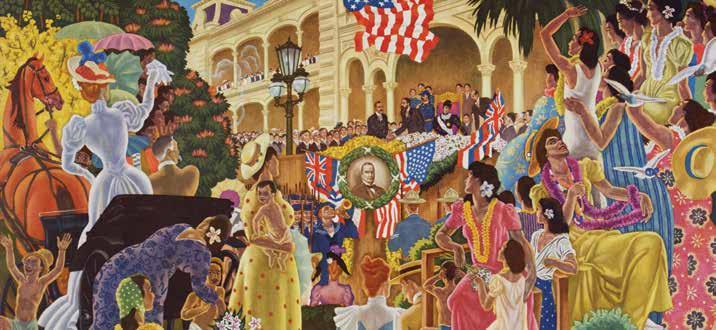

A GOLDEN LINEAGE

Creators Satoru Abe and Alma McGoldrick helped shape the landscape of visual arts in Hawai‘i in the 1970s. Today, they remain devoted to making more, making better, making of and for Hawai‘i.

62

ORCHID RUNNERS

Given the diversity and brilliance of orchids, it is ironic that the flowering scene is largely comprised of elderly fanatics. Surging out of the primordial vortex of naturalists, however, is a new breed of hobbyists, arriving with fresh energy and vigorous exuberance.

“A lot of his work has innuendos. Try look. To me, he’s a voyeur,” painter Harry Tsuchidana says about his friend Satoru Abe, one of Hawai‘i’s most inexhaustible creative forces.

68

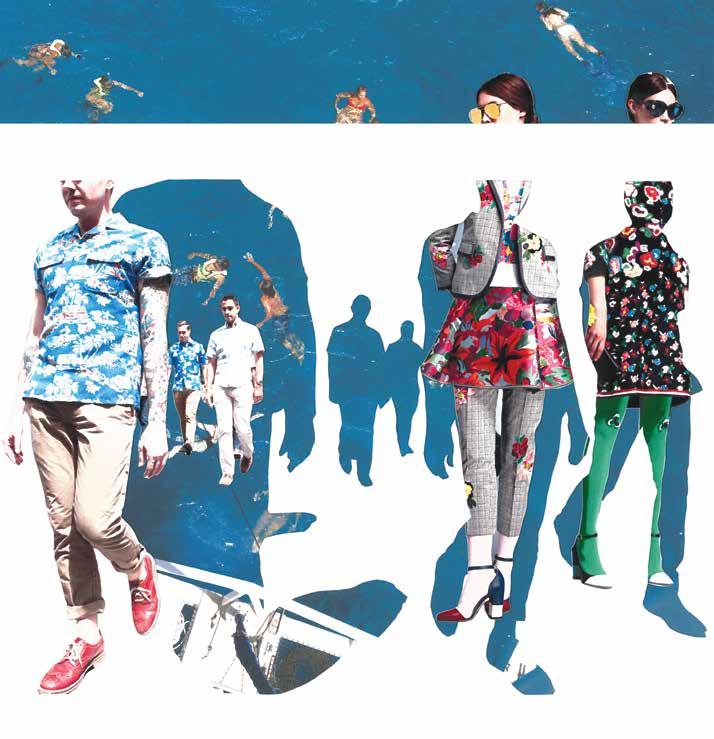

ALOHA FRIDAY

Born in the 1960s out of a spirit of rebelliousness and personal style, Aloha Fridays set the tone for the look that has come to define Hawai‘i. Collagist Landon Tom pieces together how the casual work wear still inspires the dress of today.

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

52

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

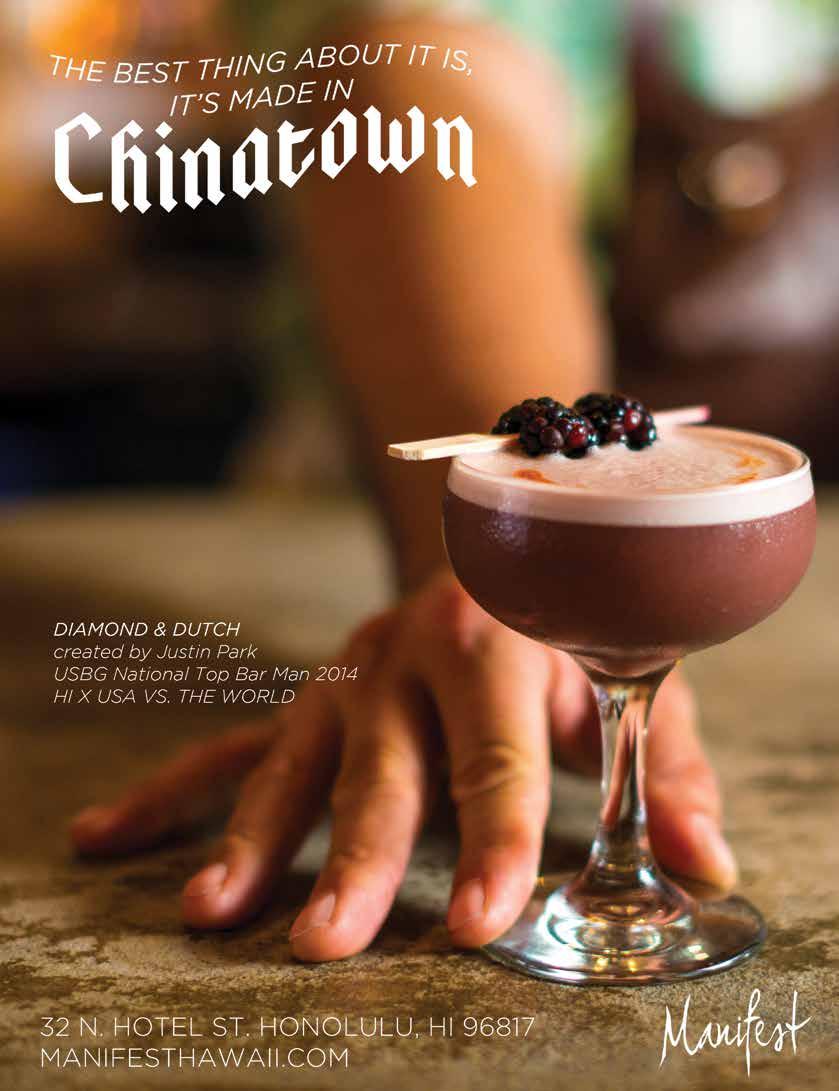

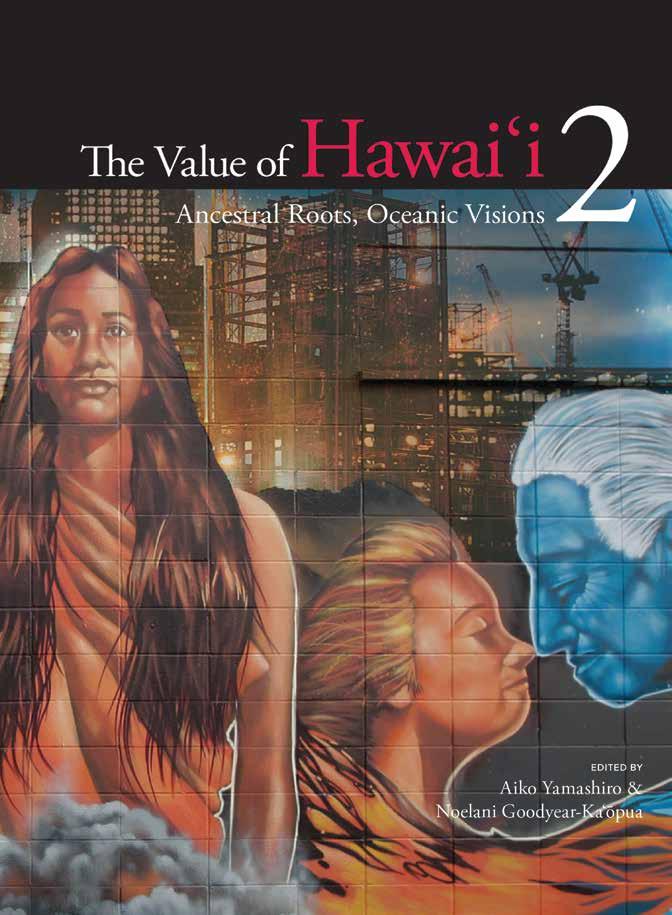

LETTER CONTRIBUTORS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 20 WHAT THE FLUX?! LET’S TALK ABOUT IT 22 LOCAL MOCO: KIMO KAHOANO FLUX FILES 25 DESIGN: SHEINFELD RODRIGUEZ A+D 28 ART: GAYE CHAN CULTURE INFLUX HOMECOMING 77 CONFETTI SYSTEM LIFESTYLE 80 LOOKBOOK: MOD SPACE 82 STATIONARY STATIONERY 90 A PERFECT DAY ON MAUI FOOD 84 ‘ULU: AN ENDURING LOVE AFFAIR 86 SHELDON SIMEON’S MIGRANT MAUI 88 JUSTIN PARK: THE HOMETOWN HERO VIEWS IN FLUX BOOKS 92 KILOMETER 99 94 THE VALUE OF HAWAI‘I 2 ARTS 96 ART DECO HAWAI‘I COMMUNITY 98 PUBLIC SOLUTIONS FOR HOMELESSNESS 100 CONFRONTING GHOSTS 108 GUIDES 28

EDITOR’S

Gaye Chan’s Eating in Public projects look to recreate the commons, where food and knowledge are freely shared.

84 25

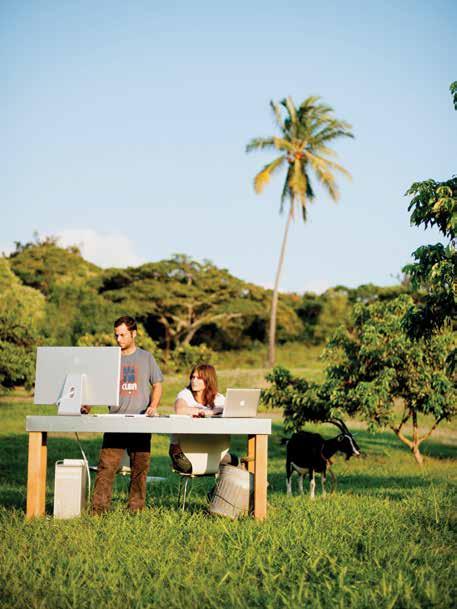

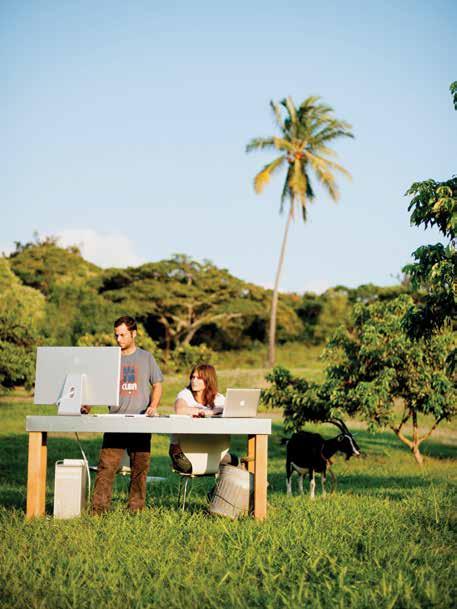

3D-design duo Sheinfeld Rodriguez A+D live off the grid on a farm in Holualuoa.

BACK TO OFFICE CRUISING ALONG

To celebrate the Aloha Friday issue online, we will be sharing some never-before-seen film photos by Alma McGoldrick (1970s photographer extraordinaire, whose story is on page 46). Joining it are a blog series documenting the ranges of alternative transportation on O‘ahu (aptly named Cruising Along) and a collection of the freshest “back to office” supplies from local shops around Honolulu.

ON THE COVER:

On the cover is a photograph taken by Alma McGoldrick from the 1970s. “I can’t remember what the model’s name was, but shots of these pretty girls and flowers kept me busy when I didn’t have fashion assignments,” says McGoldrick, who made a living shooting for local designers in Hawai‘i from the 1960s through 1980s. Read about the intrepid photographer on page 46.

Also featured is custom hand-drawn lettering by University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa design professor Chae Ho Lee. “The lettering I did for Aloha Friday was inspired by English Roundhand calligraphy from the 17th century,” says Lee, whose lettering process begins with sketches and is then refined digitally. “The lettering tries to reflect a flowing easiness yet refined appearance.”

10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | FLUXHAWAII.COM |

WE MAY BE A QUARTERLY, BUT WE’RE BRINGING STORIES ALL THE TIME ONLINE.

Stay current on arts and culture with us at: fluxhawaii.com facebook /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii instagram @fluxhawaii

EDITOR’S LETTER

| LISA YAMADA |

Five and a half years ago, I launched FLUX Hawaii during what’s now known as the Great Recession of 2009, the nation’s worst since the Great Depression in the ’30s. Of course, starry-eyed with optimism, this was of no matter. I was convinced that the market would bear a magazine of this kind—the kind that told stories others wouldn’t; the kind that reflected Hawai‘i’s vibrant culture both past and present; the kind that derided perceptions of lackadaisical living and instead promoted a people and place always moving forward, never stagnant— constantly in flux.

Of course, everyone around me balked. Traditional media scoffed. My biggest supporters were also my harshest critics. The magazine, which I consider an extension of myself, has been called despicable, fluffy, frivolous, irreverent, violent, and shocking.

Yet here we are, five and a half years later, about to take this show on the road, with distribution expanding nationwide and to Japan. Looking back at a folder on my desktop labeled “My Future,” filled with ideas, budgets, competitive analyses, marketing strategies—all the essentials of business planning 101—I found an early version of a media kit from February 2009 that noted our vision: “At the very center of the Pacific, Hawai‘i serves as a place of influx, as a bridge between the East and West. Given this unique positioning, our vision is to reorient both how our city, as well as the rest of the world, conceives of our islands.” While we’ve evolved and

grown up a lot over the years, our vision remains the same.

This Aloha Friday issue is reflective of our journey. Born in the 1960s, during a time when aloha attire was not allowed in the workplace, Aloha Fridays became a movement that grew out of a spirit of rebelliousness and personal style, popularized by those who wanted to promote Hawai‘i’s burgeoning fashion industry, as well as buck social norms. The people featured in this issue, who capture this spirit, found success by doing things their way, against all odds.

Making FLUX Hawaii what it is today could not have happened anywhere else. The support of people we’ve met along the way— who eventually turned into friends who turned into staff—is why FLUX Hawaii is possible. This place, the loneliest, most isolated landmass in the world, is teeming with opportunity, with swerve and verve, with those who were crazy enough to take the leap.

As we move into exciting new stratospheres, my hope is that you, Hawai‘i, will keep doing what you’re doing. Our future depends on it.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada EDITOR

lisa@nellamediagroup.com

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

FASHION EDITOR

Aly Ishikuni

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

COPY EDITORS

Cole Tanigawa-Lau

Andrew Scott

IMAGES

Mark Ghee Lord Galacgac

Harold Julian

Sarah Forbes Keough

Tommy Shih

Haren Soril

Megan Spelman

Landon Tom

Aaron Van Bokhoven

Aaron Yoshino

MASTHEAD

CONTRIBUTORS

Carmichael Doan

Beau Flemister

David A.M. Goldberg

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Jennifer Meleana Hee

Mitchell Kuga

Jeff Mull

Sarah Ruppenthal

Bianca Sewake

Liza Simon

Haren Soril

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns VP MARKETING & ADVERTISING keely@nellamediagroup.com

Bryan Butteling BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT bryan@nellamediagroup.com

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Matt Honda CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Louis Scheer JUNIOR DESIGNER

INTERNS

Michelle Ganeku

Torrey Seabolt

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2009-2014 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| FLUX HAWAII MAGAZINE |

“Someone recently told me, ‘There’s a difference between authentic and real; someone real will tell it like it is, no matter the outcome,’” says Kelli Gratz, reflecting on her interview with Alma McGoldrick on page 46. “For me, it wasn’t her resumé, nor the occasional profanity, that made Alma real, it was the interstices caught at moments of contemplation.” Gratz, who holds an English literature degree from University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, combines her passion for creative writing with the offbeat side of culture and travel.

“I love visiting artists’ studios,” says Mitchell Kuga, who profiled New York-based, Honolulu-born Nicholas Andersen of Confetti System on page 77. “There is so much information in what goes on behind the scenes, and in some ways, I find the experience more honest and powerful than the work displayed behind glass.” A freelance writer and waiter from Honolulu currently based in Brooklyn, Kuga is an editor of SALT, a newspaper about food and pain in New York City.

“I’m certainly not the first fanboy nerd to grow up and find himself writing about community,” says Sonny Ganaden, who wonderes if sci-fi can help us address Native Hawaiian sovereignty issues on page 36. “I understand there are ways of discussing inequality outside of blame and victimhood, so I focus on the dreamers and artists making a difference and having fun with it.” The lawyer, writer, and artist was the lead writer for the Native Hawaiian Justice Task Force Report in 2012 and was recently selected as an Orvis Artist in Residence through the Honolulu Museum of Art.

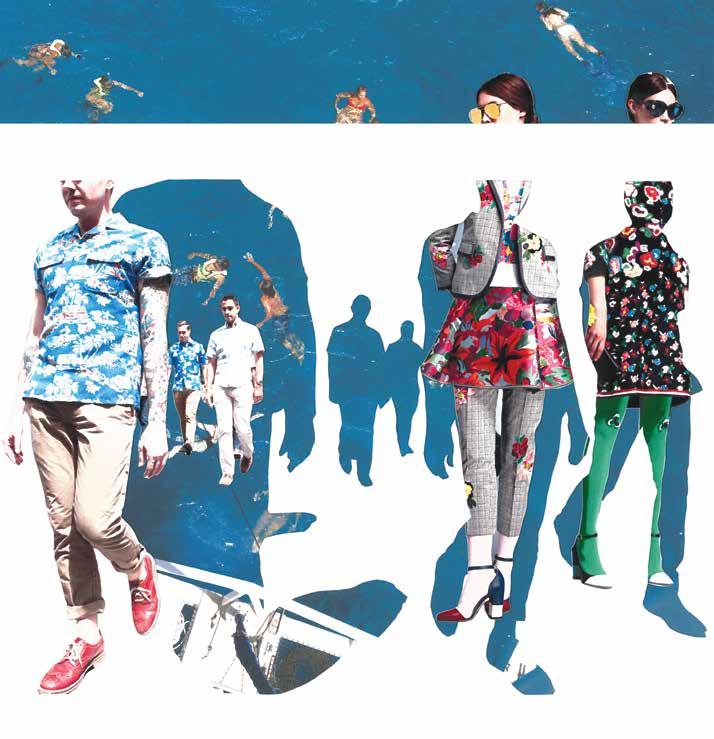

“I wanted to use imagery of factories in Hawai‘i coupled with modern fashion accessories like bags and shoes to remind us of some of the processes involved in creating these accessories,” says Landon Tom, who created the Aloha Friday-inspired collages on page 68. Growing up in ‘Aiea listening to his parents Beatles and Jimi Hendrix records, Tom’s first interaction with art came when he cut and pasted concert flyers together for his Operation Ivyinfluenced punk outfit, The Ex-Superheroes. Eventually the time-killing hobby would become the backbone of Tom’s visual art.

CONTRIBUTERS | ALOHA

|

FRIDAY

KELLI GRATZ

SONNY GANADEN

MITCHELL KUGA

LANDON TOM

HERE

WE GO…

@SpyHI “Congrats to @NellaMediaGroup for taking @FLUXHawaii international. I’m very happy…they’ll represent Hawaii well.” << We are only as good as the people we portray in our pages.

@DJDELVE “NEW YORK FASHION WEEK IN SEPTEMBER WITH THE @FLUXhawaii CREW!” << We’re as stoked as you are to take this show on the road!

@NonPareil99 “this issue screamed #renaissance done right. great vision; good works! #nostalgic for #ThenAndNow” << @NonPareil99 got nostalgic with our Fashion Issue from spring 2013 and so did we.

@supercw “New @FLUXhawaii on my desk looking amazing as always love the Marilyn Monroe photoshoot at Michael Laughlin’s house thumbs up up up” << It’s good to be loved by you.

SMALL SPACES IN HONOLULU

As housing prices continue to rise, the need to be creative with what you’ve got is becoming increasingly essential. We asked our readers to share their small-butperfect quarters, be it boat, cottage, or downtown apartment. Spaces had to be 800 square feet or less. Here are a couple of our favorites:

Tricia Beaman’s 540-square-foot Kaimukī living space is brightened with natural light. What she fancies about going small? “It forces you to live simply and surround yourself with only the things you love.”

In Gavin Murai’s 99-square-foot working studio in Kaka‘ako’s Lana Lane, everything is built to be space-efficient yet functional. His favorite item within? “The surfboard quiver. It’s like a tie rack; there’s something for every occasion.”

SUMMER JAM

We kicked off summer and the release of our Consumption issue with a jamming workshop by Monkeypod Jam’s Aletha Thomas. With jam-infused cocktails and bites, mixed and made by Hasr Bistro, the summer truly couldn’t have been any sweeter. Subscribe now to FLUX Hawaii and stay in the know about subscriberonly events and workshops.

18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM LETTERS TO THE EDITOR | ALOHA FRIDAY |

WE WELCOME AND VALUE YOUR FEEDBACK. SEND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO: LISA@NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM OR MAIL TO FLUX HAWAII, 36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A, HONOLULU, HI 96817.

WHAT THE FLUX

LET’S TALK ABOUT IT: LANGUAGE AND MULTILINGUALISM IN HAWAI‘I

“Just cuz you know Pidgin doesn’t mean you cannot know English. It’s like da more languages you know, da more power to you, right?”— Lee Tonouchi, Da Pidgin Guerilla

While we love to think we live in a world of equality, discrimination—conscious and unconscious— based on language still happens every day. Decades ago, the general consensus was that English was aligned with success and bilingualism stunted the brain, and thus the use of

native tongues was strongly condemned. Instead, today, research is emerging that positively correlates bilingualism and the empowerment of knowing a language with being able to effectively communicate with one’s broader communities. Take, for example, Hawai‘i Pidgin, a dialect that developed among plantation workers out of the need to communicate between numerous linguistic backgrounds. Since its inception, Pidgin has been deemed a “crude” way of speaking. But in the broader scheme, this multilingual mode allowed for the incorporation of many languages and cultures and is a tactic some argue as the best way to move ahead in the world today, where more than 50 percent of the global population is said to use more than one language in everyday life. Here, we expound upon the power of language, and the more-power-to-you potential of multilingualism in Hawai‘i.

Let the nays be heard: 1890s

A professor at Cambridge University reports that second-language acquisition halves spiritual and intellectual growth.

1895

An excerpt from the first biennial report of the Bureau of Public Instruction of the Republic of Hawaii after the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy states, “The gradual extinction of a Polynesian dialect may be regretted for sentimental reasons, but it is certainly for the interest of the Hawaiians themselves.” One year later, English is made the only medium of instruction in all schools, and children are soon punished if they are caught speaking Hawaiian.

2004

In a journal article entitled, “Da State of Pidgin Address,” Lee Tonouchi, who holds a master’s degree in English and is a fervent Hawai‘i Pidgin activist, tells of when he was handed a note at Big City Diner that read: “[Hawaiian Creole English] is a badge of ignorance and illiteracy. … Grow up and have some respect for the language of Shakespeare and Milton,” about his Pidgin short story “Ben the Betrayer.”

2010

A researcher from The University of British Columbia finds that in an ESL classroom in a public Hawai‘i high school, Micronesian students are strongly discriminated against by fellow students.

2013

The state of Hawai‘i is sued for making it too hard to apply for a driver’s license for those with limited English proficiency. (Shortly thereafter, tests—though not manuals—are made available in 12 languages other than English.)

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Let the yays be heard:

1820s

King Liholiho sends out Hawaiians to teach the written language in the country districts.

1984

Hawaiian language-immersion preschools are opened. According to Hawaiian language expert Helen B. Slaughter, participating in Hawaiian language immersion gives students the message that they can be proud of who they are as Hawaiians.

1993

Study done of a Wai‘anae second-grade class determines that by speaking Pidgin with their teacher, students are able to articulate their knowledge, which facilitates their interest and improves their writing in standard English.

2006

Hawai‘i’s Office of Language Access is established to help the state develop plans to provide interpretation services and translated documents in languages other than English.

2011

Research by professors from University of Georgia and College of William and Mary finds that bilingualism and creativity are positively correlated—the more fluently bilingual, the more creative the student.

2013

A Time Magazine article states that “a multilingual brain is nimbler, quicker, better able to deal with ambiguities, resolve conflicts and even resist Alzheimer’s disease and other forms of dementia longer.”

FAST FACTS

28%

The percentage of Hawai‘i’s population that speaks another language at home (7% higher than the U.S. rate), according to the 2010 U.S. Census.

600,000

The number of Pidgin speakers who count Pidgin as their first or second language in 2012.

15

The number of Hawaiian-languageimmersion, English-Hawaiian bilingual, and Native Hawaiian culture immersion public charter schools in Hawai‘i.

1920

The year that Hawai‘i Pidgin, composed of languages including English, Hawaiian, Cantonese, and Japanese became the dominant dialect among plantation children.

1978

The year that English and Hawaiian are announced as the official languages of Hawai‘i.

6%

The amount of Hawai‘i’s population that is said to be linguistically isolated (no one 14 or older speaks English in the home) in 2008.

Percent breakdown of second languages spoken at home (Age 5 and older)

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, 2006-2008 American Community Survey

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 21

TAGALOG 17.7% JAPANESE 16.7% ILOCANO 15% CHINESE 9.5% SPANISH 8.4% HAWAIIAN 6.1% KOREAN 6% OTHER PACIFIC ISLANDER 4.2% SAMOAN 3.6% VIETNAMESE 2.3% OTHER 10.5%

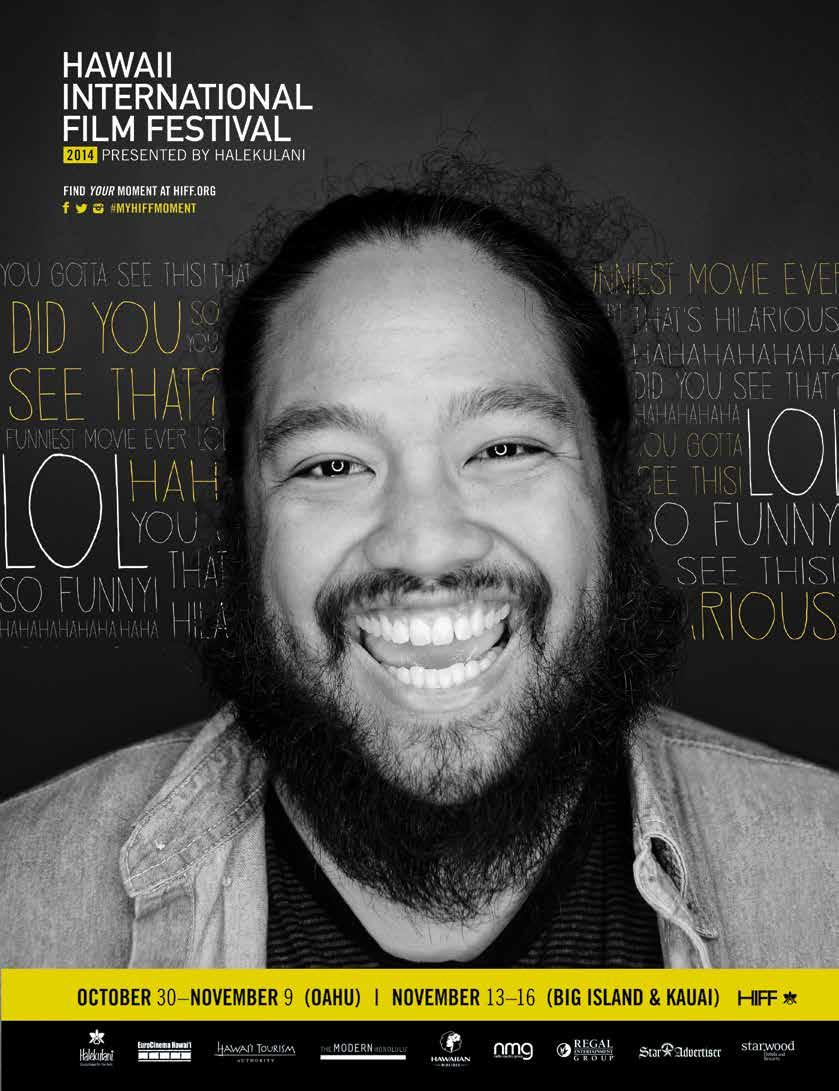

“I still get requests for ‘Aloha Friday.’ And when that happens, I will sing it. Because this song is the song of the people,” says Kimo

of his legendary tune.

Kahoano

LOCAL MOCO

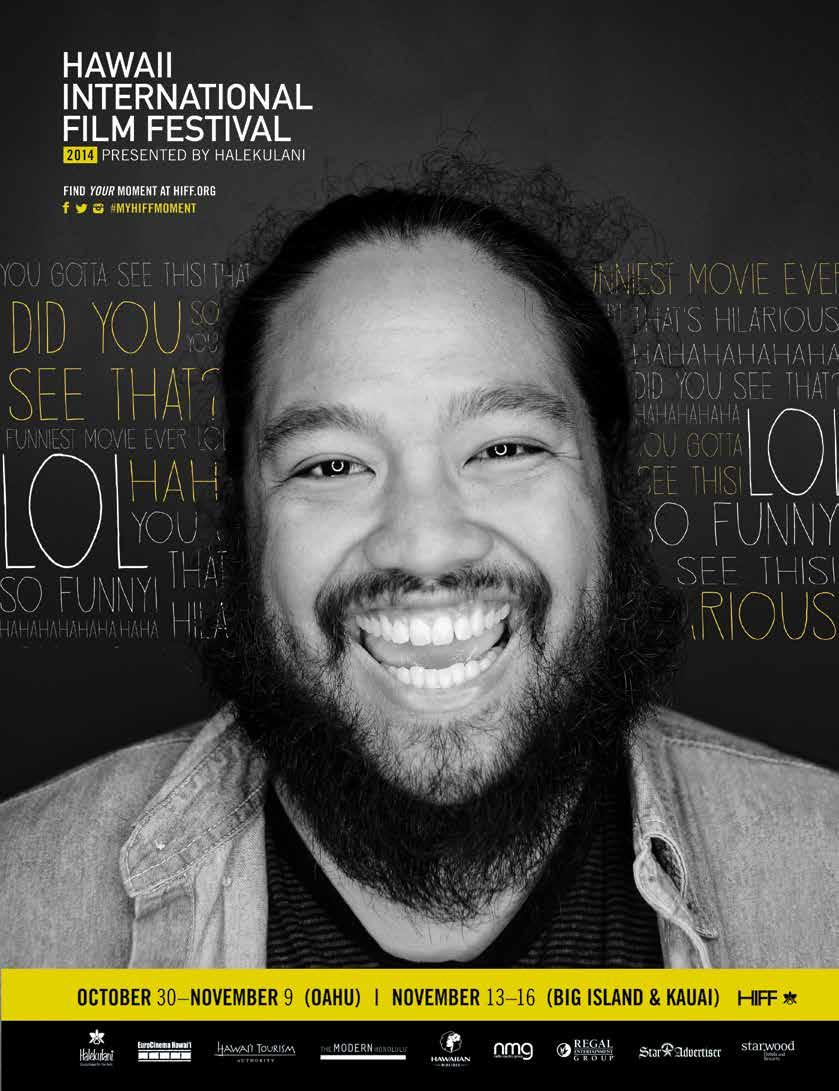

| KIMO KAHOANO |

IN THE KEY OF KIMO

ALOHA FRIDAY, THE PEOPLE’S SONG, AS SUNG BY THE LEGENDARY EMCEE

TEXT BY LIZA SIMON | IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

As I walk through Waikīkī, I savor the irony of heading to talk story with a man who often works on balmy Sunday afternoons like this one even though he gave Hawai‘i its most tuneful tribute to weekend recreation—a jaunty little lyric called “Aloha Friday.” That man, who crooned the hit 33 years ago, is Kimo Kahoano. Today, he is hosting a hula event. Of course he is. In addition to being one of the isle’s major radio and television personalities, he is Hawai‘i’s pre-eminent emcee, an ever-enthusiastic impresario for everything from funky canoe-club fundraisers to the mega-spectacle of the Merrie Monarch competition. He’s in high demand for his ineffable presence. And that novel little ditty from decades past remains part of his cred.

“Wherever and whenever I am on stage, I still get requests for ‘Aloha Friday.’ And when that happens, I will sing it. Because this song is the song of the people. It’s not just my song,” he proclaims while on break from his duties. While he admits (with my nudging) that this Sunday would be a good day for his favorite game, golf, he says the years have taught him that while he is on the job he should simply enjoy becoming an “extension of the surrounding community.” With that, he strums his air ukulele and croons: “It’s Aloha Friday/ No work ’til Monday …” Hula notables and uniformed hotel employees pass us by and flash smiles and shakas, prompting

Kahoano to comment that Hawai‘i’s TGIF celebrations can take place on any day of the week: “It’s pau hana time. It’s about working hard, whenever we can, doing all we have to do, but still finding time to go enjoy. That’s the local story,” he says.

That local story, as Kahoano calls it, is also a story that was mostly absent from Hawai‘i’s stage performance until a period known as the Hawaiian Renaissance revived not only native cultural tradition but also inspired artistic innovation. “Aloha Friday” was the product of this era, Kahoano explains.

As the Renaissance got rolling in the 1970s, Kahoano was already an established fire-knife dancer and choreographer in Polynesian revues at the glitziest Waikīkī showrooms. However, with change in the air, he jumped to KCCN radio, joining a bunch of new DJs emboldened to make their broadcasts into a sonic boom of local identity. He also joined the storied scene at Territorial Tavern in downtown Honolulu, playing music in a band to packed houses of local fans alongside the rising kings of local satire, Booga Booga. “Crazy stuff, but we loved it because it showed in a common-sense way who we are,” Kahoano says. In 1981, his bandmate Paul Natto approached him saying he had written a humorous song; Natto suggested they go record it.

In the basement of an ‘Aiea home surrounded by sound equipment, Natto

first picked out the melody of “Aloha Friday” for Kahoano. In the spirit of the era, Kahoano let it rip, dredging up his acting skills from performance training he’d received as a Kamehameha Schools student. He improvised between choruses, making up a monologue about a bruddah who is off work and cruising for chicks but ends up shelling out his credit card to cover rounds of drinks for other guys. On top of the quasi-rap, Kahoano added in a hook of “Doobie-doobie-doo”—scat singing sampled straight from Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night”—and then, to finish it off, he and Natto boosted the tempo with the beat of Hawaiian country music. All in a single take.

The song scored plenty radio airplay in Hawai‘i and California. “Lucky that corporate approval of playlists wasn’t around then,” Kahoano says. Just the other day, the godfather of Aloha Friday says, he heard it played by request on a local radio station. Kahoano clasps his hands together as if in prayer and laughs, “I am humbled that there’s something for everybody and for every generation in that song.”

Find Kahoano on—what else—Fridays, broadcasting live from 6–8 a.m. at iheart.com/live/am-940-6087.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23

THE NATURE OF IT

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON | IMAGES BY MEGAN SPELMAN

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

3D-DESIGN DUO SHEINFELD RODRIGUEZ A+D

FLUX FILES | ART |

Four days a week, at 5:30 a.m., a family of three—father, mother, and 4-year-old son—wake up before the sun to practice yoga with a man who pioneered the discipline in the United States. Afterwards, on weekdays, Daniel Sheinfeld and Loomis Rodriguez, the father and mother, head off to work on various architecture projects around the Big Island before meeting up at a small rented space to work on their collaborative design projects. Next is where their story fully veers off the beaten path— when they come home, their family life is illuminated only by a single solar-powered bulb and a sky full of stars.

“Once you taste what it is to sleep without having any buzz of electricity around you, and the possibility of taking a shower while watching the stars every single night … ” Sheinfeld gushes about living off the grid on a farm in Holualoa before switching topics to the couple’s creative aspirations. Sheinfeld is a highly energetic, tech-enthused Venezuelan who dreamed of living at the epicenter of bustle, New York City, where Rodriguez is from. But instead, four years ago, the two jumped at the chance to move off the grid from Honolulu’s Chinatown to a friend’s 15-acre farm with their then-11month-old son. The three now call home a shed converted into a bedroom and living space, surrounded by goats, sheep, organic produce, a starry sky, and not much else. “True description, we have one light in our bedroom sparked by a single solar panel,”

Bracelets fashioned by Sheinfeld Rodriguez A+D printed on a 3D printer.

he says. They only recently got a muchawaited solar-powered fridge.

The husband and wife seem to have endless energy and creativity; they spend hours each day churning through various phases of Sheinfeld Rodriguez A+D projects, particularly industrial design and jewelry. Their current focus: jewelry inspired by biomimicry, one-off pieces that are essentially wearable sculptures. “Our inspiration is almost completely organic and based in nature, but the way we create it is completely opposite,” he says. They examine the molecular and genetic structure of organisms, the framework and tiny pieces that come together to make a whole. “Instead of just making jewelry that looks exactly like a pineapple, we analyze the pineapple genetically. … From the core of nature we take that essence and transfer it into these beautiful pieces,” he explains.

Their next line will examine the makeup of water, creating jewelry inspired by how it flows along the human body. They already have their sights set on a 3D scanner, so that such a piece can be designed exactly for your neck, your wrist. Already, their jewelry involves complex coding and design, which they then translate into a resin prototype printed with their 3D printer, one of the most sophisticated models in Hawai‘i, a Form 1 by Formlabs, at their space in Holualoa. From there, they send out the prototype to be 3D-printed as a wax mold, which is then cast in precious metals like gold and

silver (they hope to be able to do all this themselves by next year). Once the piece is returned, they make any final refinements with generator-powered tools back on the farm. The result is a signature Sheinfeld Rodriguez A+D design, a highly technical, highly customized, but organic-inspired work of art.

Sheinfeld celebrates a globalized, online world, which has enabled him, for example, to collaborate with a Londonbased Pakistani architect on code-generated holographic prints; a world in which they can live on an island in the middle of the Pacific but have access to advanced technology and clients around the world. On the other hand, he loves that his family has a direct connection to organic produce, nature in abundance, and friends such as one who makes organic honey from 70 hives on the shared land. Of his life off the grid and the relief it provides from his technology-driven creation, he says, “You get really connected to the earth. I don’t think we would be able to do it otherwise, because we would go nuts.”

Find select Sheinfeld Rodriguez A+D creations at Big Island Gallery M3LD, 74-5617 Piwei Pl. For more information, visit sheinfeldrodriguez.com.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“An elderly woman came up to me and told me, ‘This is the party I’ve been waiting for my whole life,’” says UH

Mānoa art and art history department chair Gaye Chan about a recent Digger’s Dinner, where food and knowledge are freely shared.

TAKE, LEAVE, WHATEVAS

GAYE CHAN’S EATING IN PUBLIC

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

It is nearly impossible to overstate the influence Gaye Chan has had on the arts community in Hawai‘i. As chair of the department of art and art history at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, she has prodded countless students to pursue their ideas, identities, and conceptions of art. In her own work, she interrogates what it means to engage in dynamic communities, testing the boundaries of politics and economy. She confronts what those in the art and academic worlds consider normative leadership styles. She throws the most interesting potlucks in Hawai‘i. She has gained enough followers on Instagram to denote a letter: 14K and counting.

At the first public Digger’s Dinner, held in March 2014 at the Commons Gallery in the heart of UH Mānoa, all of Chan’s recent experiments regarding art and community were tested. A proponent of rules in art, Chan laid out the requirements for participating in the potluck: “Participants’ contribution must be primarily made from ingredients that they have either grown, hunted, fished, foraged, bartered, found, been gifted, or stolen. Digger’s Dinners are exercises in recreating the commons, where food and knowledge are freely shared. Participants will be asked to introduce their dish and where the ingredients came from. Any leftovers will be freely distributed the next day.”

TAKE: Act without shame.

LEAVE: Share without condition.

WHATEVAS: Trust without apology.

Most participants were game to the rules of a potluck in an academic art gallery. But there was a big difference between the event and often stuffy contemporary art shows: People were happy! The space was packed with current and former students, university people, defiantly non-university people, and members of the community who had heard about the party on the radio, read about it in the paper, or were tagged in an Instagram post. In lieu of an art show, when the tropical heat makes a joke of layered fashion and kitschy sales of Hawaiiana make contemporary art sales feel like a struggle, contributors stood in a long line to share their recipes and the myriad ways of overcoming the rules. Of course the sound system was a jerryrigged art contraption that didn’t work, but no matter, the food was delicious. Some questions went unaddressed over the microphone: Is this a potluck or an art show? Is this an attack on capitalism or a promotion of locally grown food? An incitement to petty theft? Chan, the orchestrator, seemed happy with the ambiguity. “An elderly woman came up to me during the event and showed me the newspaper clipping from the arts section of the paper,” she remembers. “She told me, ‘This is the party I’ve been waiting for my whole life.’”

The idea for the Digger’s Dinner developed organically over the last several years of Chan’s artistic practice. Years prior, Chan and her partner, Nandita Sharma, a professor of sociology at UH Mānoa, lived and worked out of a home in the Enchanted Lakes neighborhood of Kailua, where they began to call their communal art/sociology/anarchy experiments “Eating in Public.” In a strip of grass abutting a fenced-off lake for Enchanted Lake residents, they planted papaya trees. Weeks later, they engaged in a public, old-school battle via signage in front of their trees with the reluctant groundskeepers who were employed by the landowner, Kamehameha Schools. Eventually, the papaya trees were cut down and the fence extended out to the sidewalk—the public space lessened by two feet. But not all was lost: Two weeks after the trees were felled, the Enchanted Lake neighborhood assisted in creating a communal garden near where the trees had stood. “Most of us are suburbanites and don’t know a thing about farming, so there were crazy ways of harvesting,” she says. “We eventually put signs up on how to take, what herbs are used for, even recipes.”

It feels fresh, but Chan is careful to explain that she is not engaged in neologism. She is continuing the work of those over the last several centuries who

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 29

FILES | ART |

FLUX

Gaye Chan takes inspiration from 17th-century commoners who engaged in activist planting at the outset of the private-property revolution. “We’re not exactly continuing the work of the diggers, we are the diggers,” she says.

Gaye Chan takes inspiration from 17th-century commoners who engaged in activist planting at the outset of the private-property revolution. “We’re not exactly continuing the work of the diggers, we are the diggers,” she says.

have challenged capitalism’s capacity to ensure equitable lives. Blending the anti-authoritarian and the academic, Chan cites 17th-century commoners as her inspiration: serfs who were pushed off communal land at the outset of the private-property revolution and became farmers engaged in activist planting. As private-property owners divvied up plots and divested those without inheritance of land, public terrain became increasingly ornamental, unconnected to the necessities of food, water, building materials, and heating. Some of the displaced farmers formed the Diggers, whose signature act was to plant edible foods on their recently expropriated land. “We’re not exactly continuing the work of the diggers, we are the diggers,” Chan says. “We are continuing the same project: the return of our commons.”

Eating in Public includes other projects with similar reach. For the last several years, members have built seed stations and placed them in public places throughout Hawai‘i and abroad: schools, libraries, community centers. By last count, there are approximately 880 seed sharing stations located across the islands. There may be more, created by autonomous cells of diggers. An online gallery tour shows them to be quite cute. Painted with hokey plants, plastered with stickers, they are the opposite of what might be considered contemporary fine art, the type of thing a fine artist might use as inspiration.

By respecting this existing culture, Chan and her loose group of collaborators have highlighted the capacity of contemporary art to cast a light on the practices of ordinary lives. For local reference, one does not need to reach back to pre-contact Hawai‘i to find communities who bartered goods and services outside of modern capitalism. Most folks do some sort of trade: babysitting for a ride for a dinner for a place to crash for a week with friends. The barter economy (or hook-up economy) is the social lubrication of personal debt that ties many of us to each other, especially in lower socio-economic and artistic communities. Today’s Hawai‘i is also filled with the types of people who wouldn’t ordinarily consider

themselves contemporary artists: hula dancers, aunties who make costumes for hālau, uncles who work on sustainable gardens, and crafters who fill Honolulu’s Blaisdell Arena for annual fairs.

For Chan, Eating in Public is only a portion of a life in contemporary art. While on sabbatical during 2013 to develop her work and spend time with her ailing father, she took to Instagram. A lifetime of thinking about photography, content, and composition was at play immediately. Taking note of musician John Cage’s ideas considering the boundaries of art, she devised a couple for herself: no filters, nothing but pictures from her phone. Before long, a discarded orange peel on cracked asphalt became a metaphor for depression, a defaced political sign became a symbol for protest, and countless images of people showed life as it is in Hawai‘i and the places she travels. “I like to take photos of nothing,” she says blithely of what may be the medium that has made her most famous. A closer inspection reveals that the images are in sets: a series of fence images, a series of fruits, a series of people covering their faces awkwardly, plenty of coincidences, another medium with which to test theories of art and community.

There is a danger in giving some definition to an individual who is adept at defining her own work. As an ideating leader in a community of artists, it can be said that she is concerned with delimitation—the ways to transcend the boundaries created by political, economic, and aesthetic systems. In a TEDxHonolulu talk last year, Chan concluded with a directive: “If you like our ideas, contact us. Better yet, don’t contact us. Take them and run as far, smart, and fast as you possibly can.”

For more information or to keep up with Chan’s projects, visit nomoola.com.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

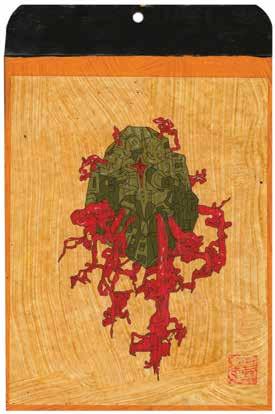

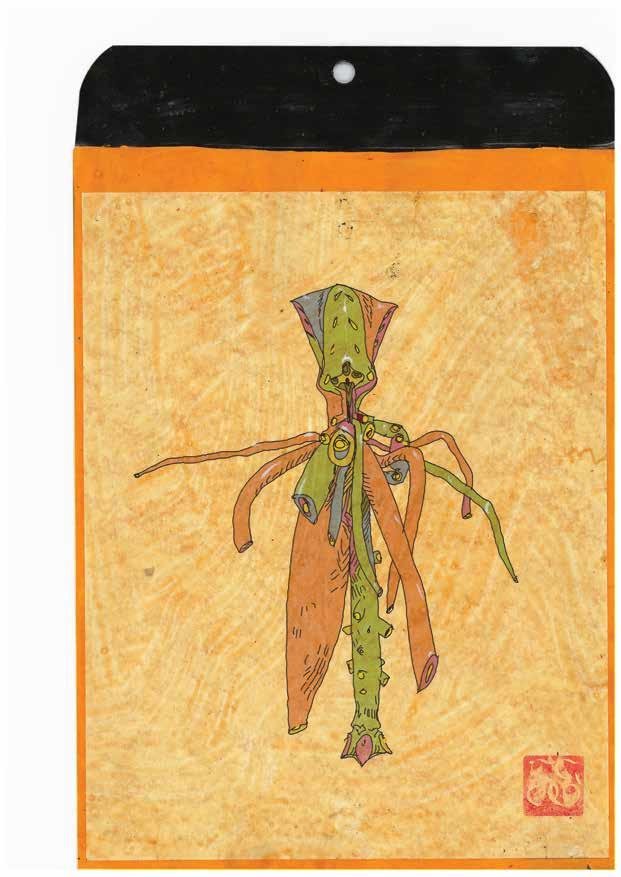

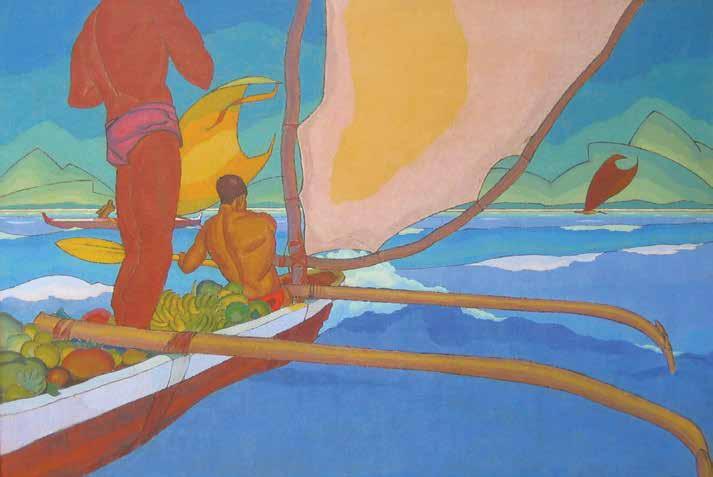

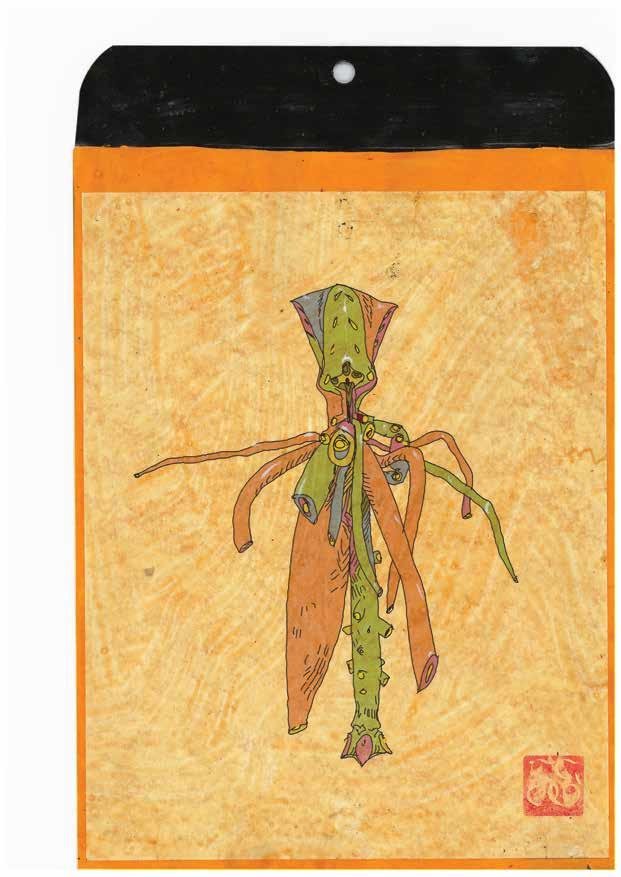

“Year 7,750, The Wu‘ugone Seed City within the Houdese Womb-World,” 2014, Solomon Enos. Pencil and digital. Opposite: “Year 31,009, A Light-Blood Class Human Seed Ship in transit to the Abūchato‘onalūpapa System via Dream-Space,” 2014, Solomon Enos. Acrylic and digital.

“Year 7,750, The Wu‘ugone Seed City within the Houdese Womb-World,” 2014, Solomon Enos. Pencil and digital. Opposite: “Year 31,009, A Light-Blood Class Human Seed Ship in transit to the Abūchato‘onalūpapa System via Dream-Space,” 2014, Solomon Enos. Acrylic and digital.

STARSHIP HAWAI‘I:

IS SCI-FI THE ANSWER?

RE-ENVISIONING HAWAI‘I’S

TRAUMATIC PAST PROVIDES A NEW HOPE FOR THE FUTURE.

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK ARTWORK COURTESY OF SOLOMON ENOS

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 37

“I think to change things on the consciousness level, we need to get somewhere mystical,” says Solomon Enos, whose recent body of work is inspired by his Native Hawaiian heritage as well as the science fiction of his generation.

What’s more sci-fi than Hawai‘i? The earth created anew from the depths; an imprisoned queen deposed by a violent oligarchy that derived power from afar; a language nearly lost; night marchers; night rainbows; the most technologically advanced military scattered across an improbable archipelago; multicultural dystopian inequality; and from the highest peak, the last place on the planet where we can truly see the stars.

One hundred twenty-one years ago, Hawai‘i was a sovereign nation. Community discussions during the last year indicate that it may one day regain that status. This process will only succeed if it incorporates the complex legal and cultural arguments crafted by the most progressive minds in the Pacific, and maybe, the fantastical images of Pacific art. Considering the history of Hawaiian leadership, this process will be peaceful despite great contention and will acknowledge the transience of our moment in time and space.

The current political system warrants the metaphors of science fiction. What would happen if an endogenous political system was developed in a lush tropical environment, overthrown by the hegemony of military and industry, and reestablished over a century later? We are about to participate in a great adventure. We are about to experience the awe and mystery that reaches from the inner mind to—the outer limits.

THE EMPIRE STRIKES

The events of the 1970s in Hawai‘i, now collectively referred to as the Hawaiian Renaissance, are still vividly remembered. When the U.S. Department of the Interior held informal listening sessions throughout the islands in the summer of 2014 to hear, among other things, what the community thought of federal recognition for a Native Hawaiian government, most testifiers set their phasers to kill. The hearings were, by many accounts, a wreck. The overwhelming majority of testifiers, most of whom were Native Hawaiian, voiced a deep sense of distrust of the federal government. And no wonder: The community is overrepresented in homeless populations, the criminal justice system, and negative health indicators, the imbalanced socio-economic conditions common to indigenous communities around the world. The Department of the Interior has since held hearings with Native Hawaiians throughout the continental United States. The response has been the same: ‘A‘ole, no, to federal recognition. There are valid reasons to advocate for federal recognition, all of which have been argued to death since the introduction of the Akaka bill 15 years ago. The current protections afforded to Native Hawaiians in housing, health care, education, employment, and culture through the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, the Department of Hawaiian Homelands, Kamehameha Schools, and other smaller organizations have been under constant attack from lawsuits based on state and federal equalprotection laws. Federal recognition would both preserve state-funded institutions providing support to Hawaiians and extinguish claims of nationhood. For most who have testified, it isn’t worth it.

An op-ed co-written by Ilima Long, Jon Osorio, and Andre Perez in the Honolulu Star-Advertiser titled “It’s an international rights issue, so U.S. must step back” sums up many of the arguments: “These actions violated our rightful existence under international law in the 1890s, and now violate our collective right of self-determination and individual human rights,” the activists wrote. “The Department of the Interior and the State of Hawai‘i should not

attempt to influence or interfere with the nation-building that has been ongoing among kanaka for the past 30 years.” In advocating for a sovereignty movement that is peaceful, they requested simply that the federal and state governments do not interfere with a process that grows at its own pace and according to its own ideals. “We do not want just any governing body,” they concluded. “We want the restoration of our independent government and we deserve nothing less than that.” What this governing body might look like once the process is completed is as yet unknown, but sci-fi helps reimagine the past, as well as the future.

THE FORCE IS WITH YOU

That speculative fiction has real relevance to our discussion of subjective politics should come as no surprise. Author Junot Diaz has been extolling the merit of genre narratives in the wake of his 2007 Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao, which follows the tribulations of a sci-fi-loving Dominican nerd in New Jersey and Santo Domingo. “Without our stories, without the true nature and reality of who we are as People of Color, nothing about fanboy or fangirl culture would make sense,” he says in a podcast in 2013. “What I mean by that is, if it wasn’t for race, X-Men doesn’t make sense. … If it wasn’t for the history of colonialism and imperialism, Star Wars doesn’t make sense. If it wasn’t for the extermination of so many Indigenous First Nations, most of what we call science fiction’s contact stories doesn’t make sense. Without us as the secret sauce, none of this works, and it is about time that we understood that we are the force that holds the Star Wars universe together.”

The possibility of alternate universes makes absolute sense to some in the sovereignty discussion. In Hawai‘i’s small contemporary art circles, Solomon Enos is something of a celebrity. He works as fast as he speaks and has been known to sketch complex murals with a brush on a stick in minutes. Though much art in Hawai‘i is sold in galleries aimed at the visitor market, Enos is one of a handful of local painters making a living as an indigenous artist without pandering to outsiders’

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 39

concepts of native culture. But Enos’ work also sells in tourist markets: His paintings line the halls of Aulani, the Disney resort, and several Waikīkī hotels. He has illustrated books, prints, and paintings for businesses and community groups. “I’ve loved Frank Herbert, Ursula K. Le Guin, Kurt Vonnegut for years now,” Enos says of his inspiration. “They created worlds, what-if narratives.” Having grown up with both the mo‘olelo of his grandmother and the science fiction of his generation, his paintings can be as beautifully grotesque as H.R. Giger’s (who inspired, among other things, the noir look of Aliens) or as eerily romantic as Alan Lee’s Lord of the Rings illustrations. “I figure by looking back at our narratives, there’s a lot of my, and our, reality that depends on the same sort of what-ifs. I’d say this is a sort of activist escapism. When I put the book down, I can engage with the world in a better way.”

Over the last two decades, Enos’ most ardent passion has been Polyfantastica , a science fiction-inspired narrative that spans 40,000 years of Hawaiian history. He has completed nearly 400 images representing centennial vignettes, which are the prospective book covers for a narrative that reaches far into the future. “At that point, good guys and bad guys become moot,” he says. “We’re in the process of uploading it all online to make the narrative accessible and workable by anyone with a computer. It’s been a garage project, but we’re getting to a critical mass now.” Enos’ hope is that other Pacific sci-fi buffs will assist in the project and fill in the narratives he has begun to illustrate—an activist fan-verse, a Polynesian sort of Dungeons and Dragons

Enos lets his what-if scenarios play out with his recent Human Seed Ships series. In dozens of paintings, he imagines a Hawai‘i where Polynesians never encountered Captain Cook in 1776 and the archipelago goes undiscovered by the rest of the world until a global apocalypse. When ships do wash up in Hawai‘i, they are filled with the corpses of environmental refugees and hyper-modern technology. “Then these Hawaiians are affected not by disease, but by fear, the things we’d have to flush out of our system if we were contacted or not,” he explains. The resulting paintings are fascinating. With

Enos’ skill as a draughtsman and painter, they are Salvador Dalí-level trips that draw from the Polynesian-centric world to create a pantheon of characters. “What does nationalism mean in the future? What about sovereignty? I’m trying to be as long-viewed as possible. I think to change things on the consciousness level, we need to get somewhere mystical. We knew we could navigate to islands because we knew they were there. Now we have to navigate through the current future. It’s not American or Eurocentric. As much as I love Lord of the Rings, I realize we need our own way of telling things. One-third of the world is the Pacific Ocean. It’s time we hatched our avatars, our origins, our crazy.”

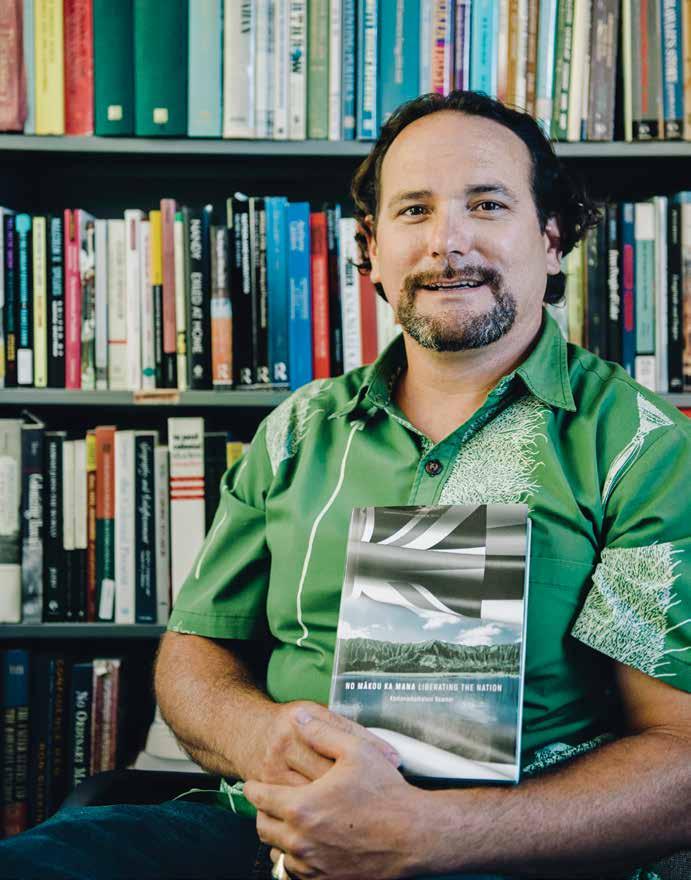

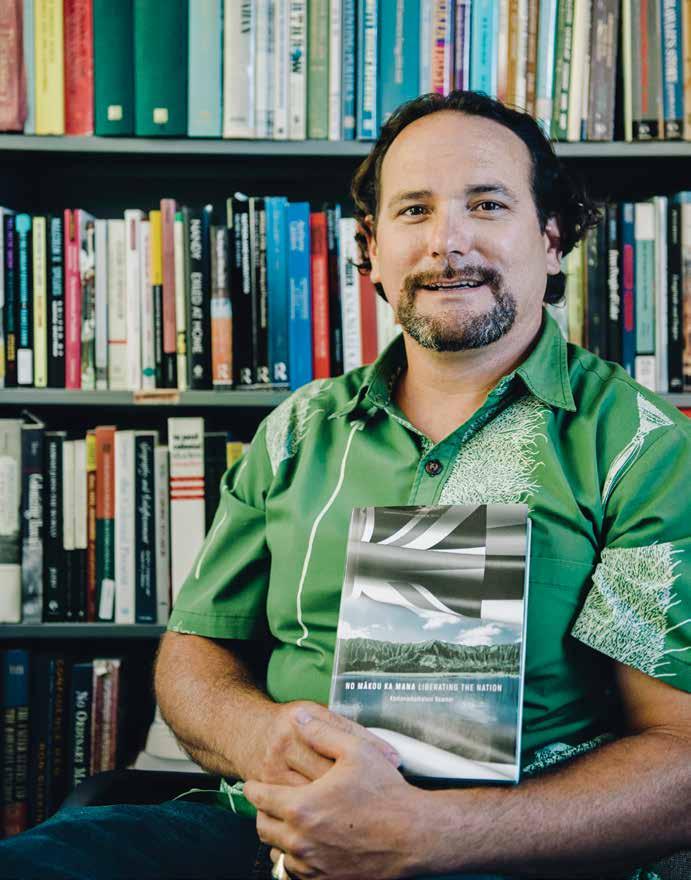

A NEW HOPE

“The sovereignty discussion of the last year has been as spirited as it’s been in decades,” professor Kamanamaikalani Beamer tells me at his office in University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Hawaiian Studies building, “but I’ve never been as optimistic.” Beamer’s new book, No Mākou ka Mana: Liberating the Nation, discusses the intelligent and creative ways in which the ruling ali‘i of the Hawaiian Kingdom engaged with aggressive foreign powers, blending Hawaiian governance with ideas from the West. It also diligently explores ways in which natives were at times complicit in 19th-century imperialist agendas.

“No Mākou ka Mana is not concerned with what missionaries or foreigners did for or to Oiwi (natives), but rather what Oiwi did for themselves, in the midst of depopulation and constant threats of colonialism,” he writes in the introduction. “I believe that living cultures are dynamic and always in a state of change. I believe the dichotomies of the traditional and modern, with all their connotations, are false. They compose the conceptual shackles that preserve European hegemony and often reinscribe links between the colonizer and the colonized, occupier and occupied.” Many of the people Beamer researched were non-Hawaiian patriots for the Hawaiian Kingdom. Though imported labor and capitalism played a role in racial and economic stratification, the citizens of the kingdom were enfranchised people with

universal suffrage, all races cooperating in government—so thoroughly different from the governments of that era.

In lieu of a deep textual analysis of a little-known anti-annexation letter signed by Queen Lili‘uokalani, which she addressed to the British government, Beamer presents it in its original form. “It’s a gorgeous letter, isn’t it?” he says with wonder. “Probably not written in her hand, but it’s clearly her thoughts. Something like that, it’s best to just present it directly,” he says.

The letter articulates what residents of this archipelago, Hawaiian and nonHawaiian alike, have accepted as an inconvenient history. This is now taken as fact: The kingdom resisted takeover using peaceful, diplomatic means; the United States did not execute a valid treaty of cession or annexation, as was required in 1898 for an annexation to be valid under international law. Beamer spares no criticism of the provisional government that took over the kingdom in a series of events that, by modern analysis, was a takeover supported by the American military—the men who formed a Republic as megalomaniacal grabbers of empire.

The takeover was as much cultural as it was political. The way Beamer describes it, annexation was akin to a Star Trek temporal disruptor bomb, the kind that warps the space-time continuum, destroying past, present, future, everything. After annexation, Native Hawaiians experienced the taking of land by non-native peoples under quasilegal arrangements supported by racism and xenophobia, resulting in a collective downward social mobility in their own homeland. But throughout this experience, the record kept in Hawaiian was tight, like a time capsule that has taken a century to open, and academics in Hawai‘i and throughout the nation have been accessing decades of communal dialogue. The translations are chilling in their prescience and erudite analysis of global political events. “It wasn’t until I was fluent [in Hawaiian] that I could get it,” says Beamer, pointing to a Honolulu newspaper clipping from the 1890s taped to his office door that discusses the annexation. “‘News from America’ is what this part translates to. Their readership realized that America was a foreign place. It’s part of why I structured this mo‘olelo this

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“Year 31,009, A Smell-Thought Class Human Seed Ship in transit to the Huāpajitu Nebula via Dream-Space,” 2014, Solomon Enos. Acrylic and digital.

“How do I, as a native person, work with the tools around me? I’m a family man and come from entertainers, farmers, activists. But here I am using an iPad in air conditioning,” says

Kamanamaikalani Beamer, whose new book No Mākou ka Mana is out now.

By refusing to see Hawaiian leaders merely as passive victims, Beamer comes to grips with the need for modernity, for future-thinking, and for mediating value systems in an inhospitable universe.

way: to tell the story of Hawaiians doing things their way, in their own voices.”

By relying on the narrative of history, Beamer eschews the patchy inadequacy of American jurisprudence to highlight substantive equality and effectuate justice. The sovereignty conversation has painfully moved past America’s problematic, possibly intractable, issues with race. The equal protections afforded by the state and American constitutions, for which a civil war was fought and countless Americans marched in the streets decades ago, have proven inappropriate tools to remedy a problem rooted in political history. The movement that was the impetus for the civil rights era, community organizing directed at specific empowered targets, and the critical legal scholarship that developed as a result over the last several decades—these are indeed helpful. This organizing influenced the world: from the Māori land march of 1975 to South African apartheid resistance to the environmental and sovereignty movements in Hawai‘i.

“We haven’t yet contextualized Hawai‘i in terms of pacifist struggles around the world, but that’s exactly what this was. This was one of the first non-colonized, non-European modern nations in history. And it’s a story about myself as well,” notes Beamer. “How do I, as a native person

navigating this space, work with the tools around me? I’m a family man and come from entertainers, farmers, activists. But here I am using an iPad in air conditioning.”

Beamer and his colleagues have used technology to both archive and research original documents, many of which are in ‘Ōlelo Hawai‘i. By referring directly to native voices, No Mākou ka Mana adds to the literature written in the intervening decades since occupation, the basis of which reconstruct a historical framework. By fully articulating the rich legal, cultural, and social history of the nation of Hawai‘i prior to overthrow, the academic work of Haunani-Kay Trask, Jon Osorio, Noenoe Silva, and dozens of others become the foundation upon which to rebuild a nation. By refusing to see Hawaiian leaders merely as passive victims, Beamer comes to grips with the need for modernity, for future-thinking, and for mediating value systems in an inhospitable universe.

The community of social-justice nerds agree. A course titled “Political Science Fiction” at UH Mānoa uses the Star Trek universe to discuss the fluidity of identity and political systems. Bryan Kamaoli Kuwada, an English-department PhD candidate who concentrates on Hawaiian translation, recently published “Of No Real Account,” a fantasy adventure story featuring Hawaiian mythology, in the

literary journal Hawai‘i Review. “Sci-fi’s a way to get past the whole crabs in a bucket, pulling each other down while trying to get out metaphor,” he says at a Hawaiian sovereignty event over the summer. “That’s old. We need new stories. Plus this kind of writing is actually fun.”

Though fictional, Enos’ paintings and Kuwada’s stories speak to the trepidation some feel about the future of a Hawaiian state and its relationship with America. No one is sure how this will work out. But the arts community has answers that are at least more interesting than temporal politics, with creative ideas about the worlds we should inhabit rather than the dismal one we do. With so much of our modern lives regarding communication and technology predicted decades ago by science fiction, it is possible, necessary even, to apply the same utopian fantasy to political systems.

Nerds know how the story ends: Not without struggle, the destructive, inequitable rulers are defeated. Peace and order eventually reign throughout the galaxy. Our heroes are explorers who embark on intrepid missions of peace. Optimistic adventure takes precedent over conquest, as do exploring new worlds, seeking out new life and new civilizations, going where no one has gone before.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 43

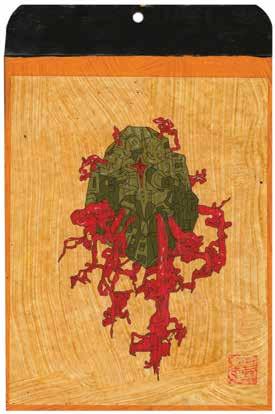

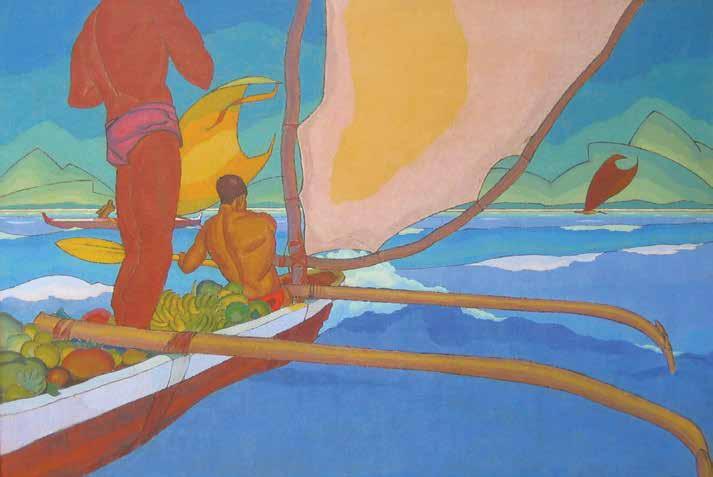

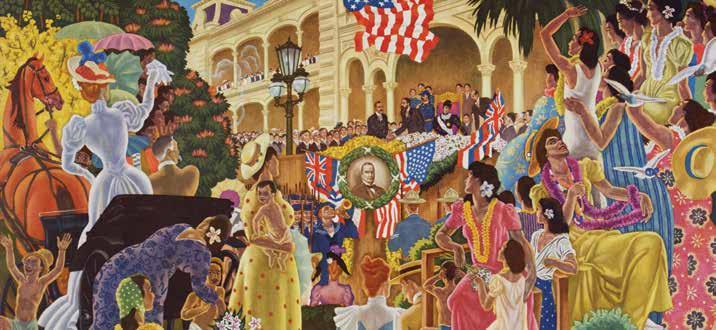

A GOLDEN LINEAGE

CREATORS SATORU ABE AND ALMA MCGOLDRICK HELPED SHAPE THE LANDSCAPE OF VISUAL ARTS IN HAWAI‘I IN THE 1970S. TODAY, THEY REMAIN DEVOTED TO MAKING MORE, MAKING BETTER, MAKING OF AND FOR HAWAI‘I.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

“I’ve always enjoyed working with natural materials. Nature, above anything else, is my greatest love,” says Alma McGoldrick, whose enduring images shaped the way people viewed fashion in the islands.

PORTRAIT OF A LADY

AFTERNOON TEATIME WITH LEGENDARY

CAMERAWOMAN ALMA MCGOLDRICK

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

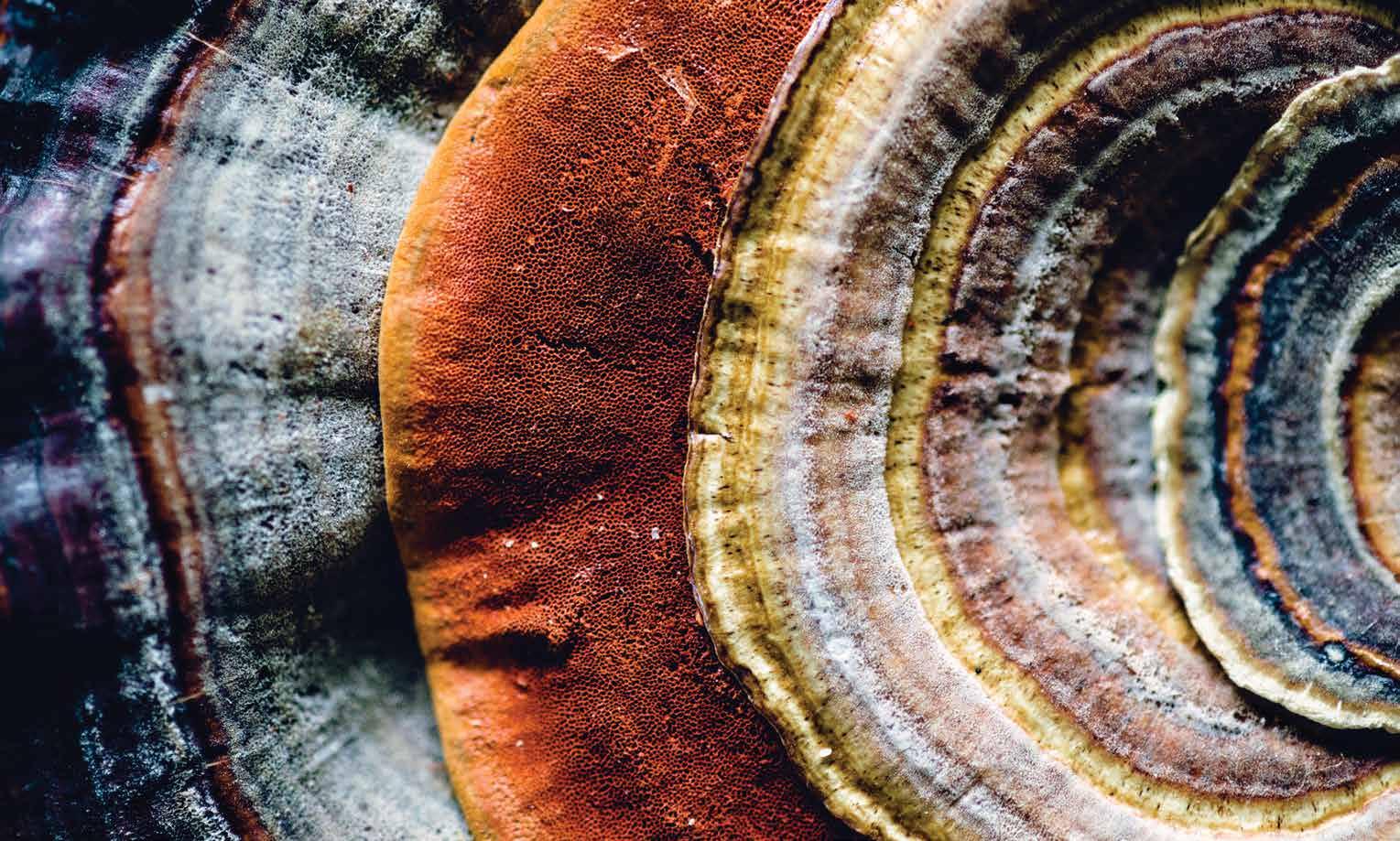

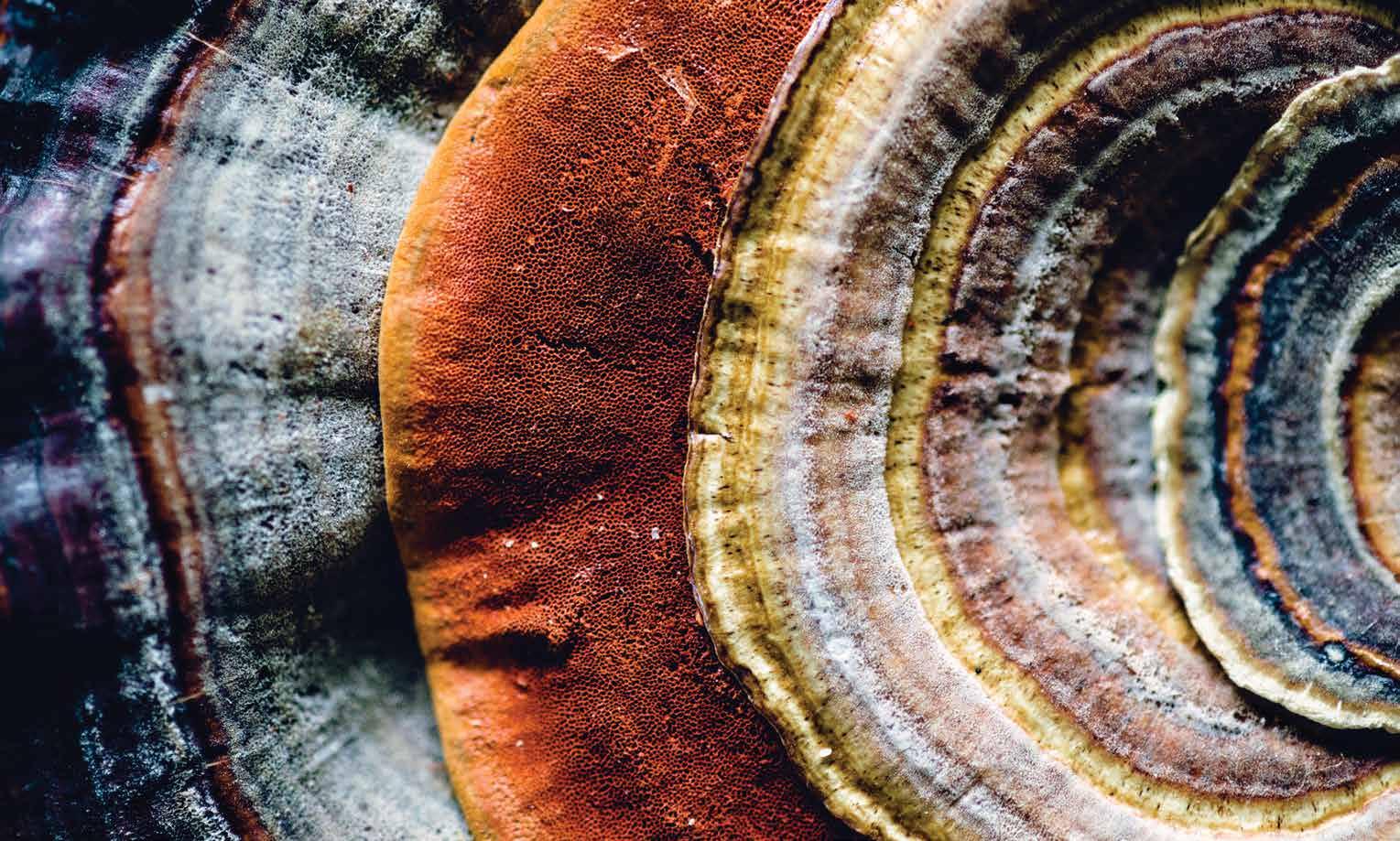

Even in her mid-80s, Alma McGoldrick still hikes to collect the fungus for her exquisite hand-made jewelry.

Even in her mid-80s, Alma McGoldrick still hikes to collect the fungus for her exquisite hand-made jewelry.

“Would you like some sugar?” Alma McGoldrick says in typical British fashion: in the middle of a sentence, over a pitcher of tea. She muddles fresh mint just picked from the balcony of her home in Kailua, where she has lived for the past 30 years, and mixes it into the brew. Good books and interesting small antiquities crowd the walls and shelves, and binders filled with aged snippets of a young, blond Englishwoman gripping a flashgun and Rolleiflex cover the tabletop as afternoon tea commences. “I have about an hour to spare before my Bocce ball practice,” she says. “For years, it’s been hard to get a good team together because everyone either moves away or dies on me,” she says with a laugh. “But now we finally have one, so it makes it competitive.”

Her strong British accent and racy argot are easily explained by her upbringing in Surrey County, England. Her dress, however, can be likened to her travels: loose-fitting harem pants from the Arabian Peninsula and a black top made in Southeast Asia, complemented by a gorgeous, hand-made fungus necklace from her jewelry line Tree Shells, which is what she calls the fungi she sources from the Hawai‘i rainforests. “I’ve always enjoyed working with natural materials,” says McGoldrick. “Nature, above anything else, is my greatest love.”

Naturally then, her stories extend far beyond the shores of Kailua beach to the banks of the Middle East and Europe, where she worked as a staff photographer for the Women’s Sunday Mirror, a subsidiary of the London Daily Mirror. “The year was 1955, and it was the most exciting time of my life,” she recalls. “I got all the fun jobs—photographing Salvador Dalí, Prince Aly Khan, Arlene Dahl, Gina Lollobrigida. I covered a sheikh’s marriage to his fourth wife and a pre-Lenten festival in Cologne. I even went to a nudist island off of Germany.”

Before this, McGoldrick worked as an elementary school teacher with a penchant

for natural beauty. “I hated teaching!” she says with a gasp. “I knew it wasn’t for me, but everyone kept telling me to stick it out, so I did the two years to get the certification and then quit right then and there.” She enrolled at the Guildford School of Photography and did freelance work before she went to the Mirror. Two years later, in 1957, she came to Hawai‘i on the arm of her first husband, Joseph McGoldrick, whom she had met when he was head of U.S. Navy intelligence in Europe. “I fell in love with the rich and ethnic differences it offered. My favorite location was Sandy Beach. Models’ hair would go flying up in the air, and there was a nice light that bounced up from the water’s edge.”

As McGoldrick’s photography career grew, changes in consumerism and new feminine ideals were causing major shifts in fashion photography. The elegant, submissive prude gave way to the single girl who loved adventure. And right at the forefront of this revolution was the grande dame herself. “For quite a long time, I did pin-ups,” she says of the bikini-clad women she photographed. “I would take them to Pacific Business News, and the editor took what he liked. Then the women’s libbers got to them, and they stopped running them. I remember an article that was written about me saying, ‘What does this woman do every morning to excite businessmen in Hawai‘i?’”

Her photography career waned in her 50s when her focus shifted from capturing images to raising her two children, traveling, and jewelry design, an interest that had been piqued during a photo session years before. “My friend had given me macramé necklaces for a shoot I did, and my daughter saw them and loved them,” she says. “At the time, I didn’t have any macramé, but I had some extra fungus from a collage I did so we used that instead.”

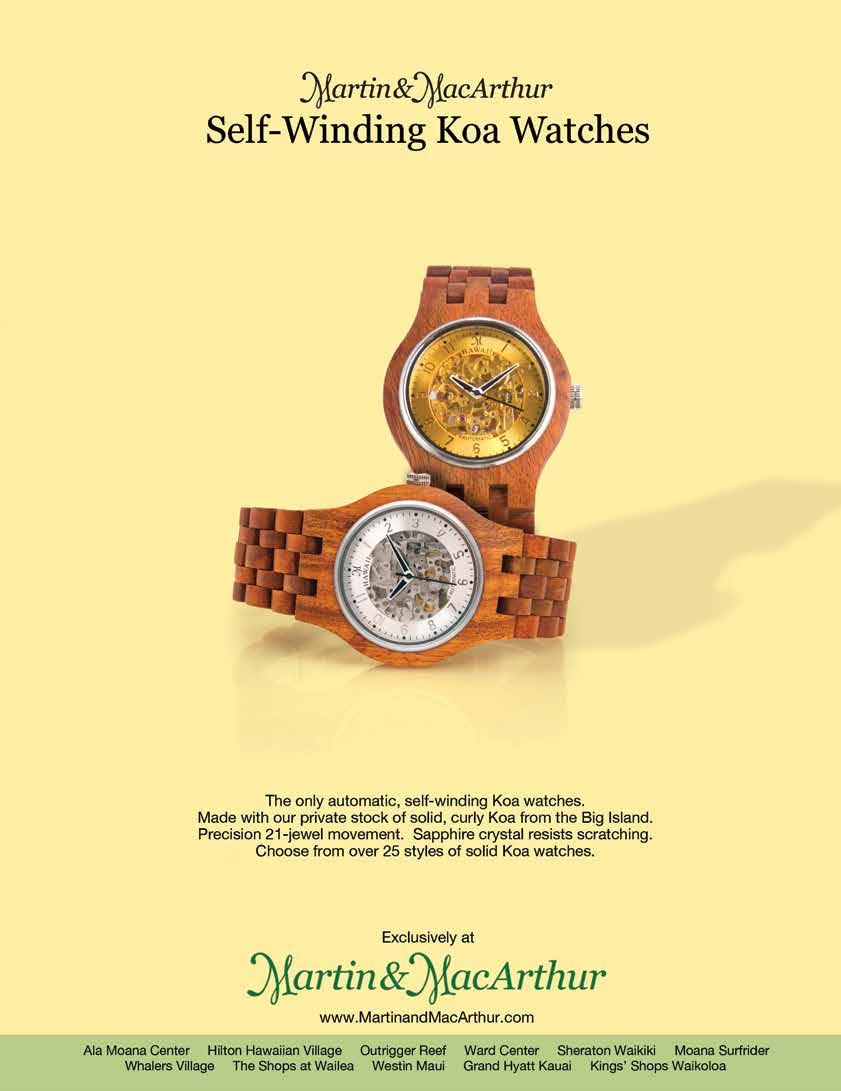

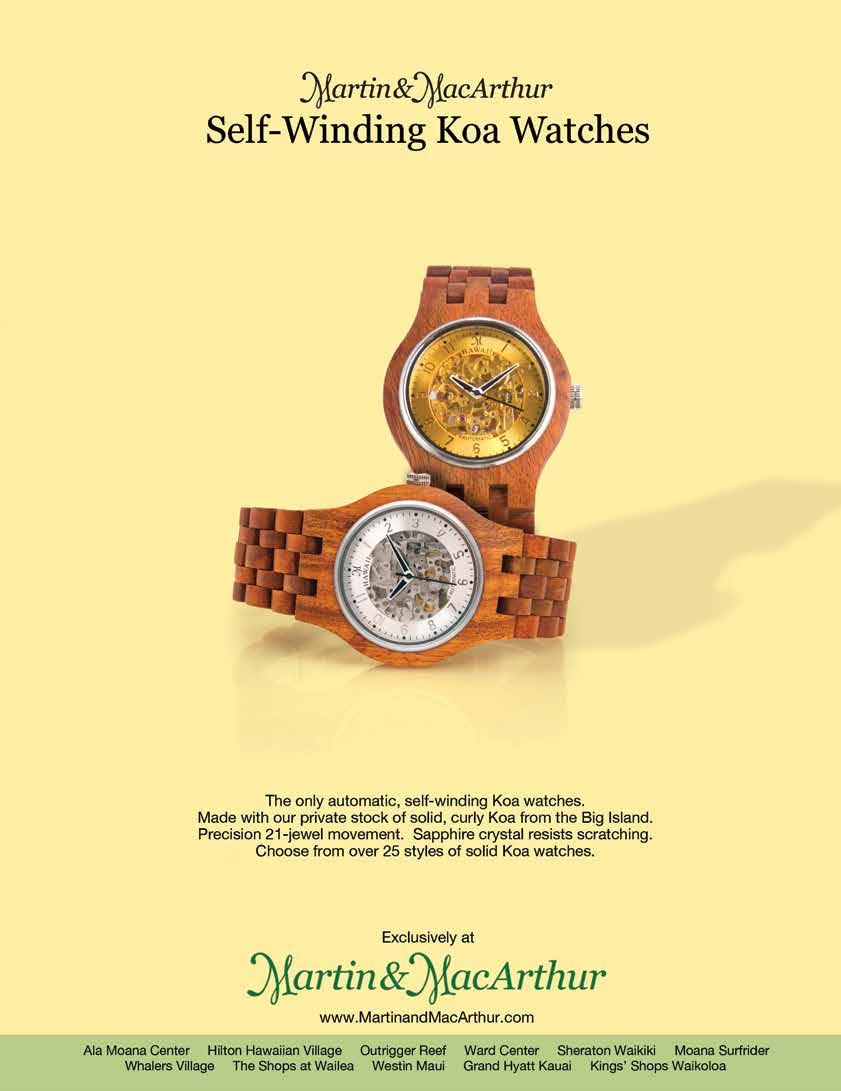

Now in her mid-80s, McGoldrick is determined to keep doing what she’s always done: snorkeling (at least) twice a week, trespassing through private property to get

“just the right color of fungi” needed to fulfill orders from Martin and MacArthur, and perfecting her savasana and downwarddog poses. “I don’t shoot anymore, except for my photo club,” she says. “It’s quite pathetic actually, but we do try to get out there every once in a while.” While she professes that navigating through the murky waters of old age can be tiresome (severe vision loss in one eye, a fractured vertebrae, and peripheral neuropathy), the rambunctious trailblazer in the trenches of Beirut or Kathmandu still shines through.

Looking through archives of contact sheets, cover shots, and one-pagers of gorgeous models posing in alohawear by Tori Richards, Malia, and Nali‘i, you can’t help but wax nostalgic for the Hawai‘i of then. From the folds, she pulls out an old Honolulu Magazine cover featuring a young model, topless but for an array of colorful flowers. A faint smile brightens her face. “My favorite portrait has to be this one,” she says. “It took forever to get the flowers to stay put in the right places.” She looks at the image, hands it to me, than moves on to the next. Her energetic conversation tells of a successful life, a life far from over. For McGoldrick, nature continues to fuel her fire, extending outward to the tips of her fingers, energizing whatever she touches—be it a camera body or bracket fungi—and rendering it beautiful.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 49

As changes in the

our website to view

including

new feminine ideal arose in the ’60s, photographer Alma McGoldrick’s images shifted from the elegant, submissive prude to the single girl who loved adventure.

Visit

more of McGoldrick’s work,

this shot she took of beads of papier maché by Baba Kea for Honolulu Magazine, as well as never-before-seen film scans.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

IN SEARCH OF SATORU

A REFLECTION ON THE INFLUENCE OF ONE OF HAWAI‘I’S MOST INEXHAUSTIBLE

CREATIVE FORCES

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 53

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

“There’s a number 10 thread that goes through art history, a thin line that goes from one generation

to the other—like Rembrandt, Picasso, all different works of art. I always wanted to be part of that and strive for it.

Does the world put Satoru into

that?

We don’t know yet, because time is the judge.”

—Harry Tsuchidana

On a warm Saturday morning, a steady stream of people trickles in and out of Satoru’s Art Gallery, a plain two-story walk-up behind Old Stadium Park in Mo‘ili‘ili. News of the gallery’s imminent closure after nearly a decade has gotten around, and patrons, friends, and family have come to pay their respects to the beloved artist, browse the immense collection of his sculptures and paintings, and of course, purchase.

The gallery’s namesake, Satoru Abe, pauses to take a picture with a woman. In front of them stands a wooden sculpture about two feet high with bronze petals flowering from the top; beneath it, the $20,000 price tag has been covered with a red dot. After a cursory glance around the gallery, I count five more red dots below similar pieces less than an hour into the opening. “Who do I make the check out to?” asks a man dressed in slippers and shorts. When I first asked Satoru for an interview on his influence as one of Hawai‘i’s most prolific artists, he humbly declined. “No, no, I talked too much already,” he says. And he has talked plenty. Google “Satoru Abe” and his life is in plain view: how he grew up in Honolulu

as a Japanese American; how he, at the age of 22, “saw the light” while working as an assistant pasteurizer at Dairyman’s (now Meadow Gold); how he struggled as an artist to make ends meet in New York and met the love of his life, Ruth, while they attended Arts Students League; how he, upon his move back to Hawai‘i in 1950, rose to acclaim with the Metcalf Chateau, his gang of local boys that included Tadashi Sato, Bumpei Akaji, Bob Ochikubo, Jerry Okimoto, Edmund Chung, and James Park, all of whom have since passed but were pivotal in introducing abstract expressionism (the playfully rebellious form that arose in New York City after WWII) to Hawai‘i; how he honed his artistic ability at New York’s Sculpture Center and returned to Hawai‘i in the ’70s; and how he, over the next four decades, would become one of Hawai‘i’s most beloved—and most commissioned— artists of all time, passionately devoted to his work and to the work of others.

And since a man cannot be all things to all people, I talked to four of those who know Satoru best about the influence of Hawai‘i’s most renowned of artists. Slowly, an impression began to emerge.

SATORU: THE FRIEND

“His work, it’s like a multiple orgasm,” 82-year-old painter Harry Tsuchidana tells me. “Because he get lot of things going on in it. Mine, I have one orgasm; after that you smoke.”

For those who know Tsuchidana, conversations like this are typical. In the 180 minutes I spend at his home studio in Salt Lake, our talk runs the gamut of hysterical to obscene. We talk about astrological signs and how they’re excellent conversation starters; how he learned to draw by tracing comic books and that he’s older than Batman by seven years but younger than Superman by ten; and how the work that will stand out most after Satoru has passed will be cock. “Chicken?” I ask sincerely. “No, penis!” he says with a high-pitched snicker. I can’t tell if he’s joking or not. Then he says, quite seriously, “When one dies, people gonna focus on some work that was so different from the

rest and that was it. … A lot of his work has innuendos. Try look. To me, he’s a voyeur. Of course,” he says, reflecting, “I’m reading into it.”

Tsuchidana first encountered Satoru by happenstance on his first day living in New York. “‘You guys was rejected’— that was my opening line to them,” says Tsuchidana, who remembered Satoru’s and sculptor Jerry Okimoto’s names after they had applied for Corcoran Gallery of Art’s biennial exhibition in Washington, D.C., where Tsuchidana had been working as a janitor. “I never did meet them before; I just saw them and felt intuitively that these were the guys—what’s the chance, yeah?” Just as Satoru and Okimoto were about to walk away from the young hassler, Tsuchidana called out, in true local fashion, “‘I know Sugar’—that’s Tadashi Sato—so they came back and said, ‘Oh Sugar, he’s at 109th Street,’” where all the artists were living at the time.

Tsuchidana was the youngest of the bunch. By the time he got to New York to pursue art in 1956, the boys from the Metcalf Chateau were already securing their spots in the art world. Satoru worked tirelessly on the third floor of Dorothea Denslow’s Sculpture Center while gaining prominence through group shows around the city (including a sculpture exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art); in 1963, he was awarded a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship.

Roving New York with Satoru and the others, Tsuchidana was privy to some of the city’s finest galas, like the opening of the Guggenheim in 1959, and to meeting celebrity collectors like Burgess Meredith, who came to Tadashi Sato’s apartment to look at art. Mostly, though, the lives of the artists comprised of playing cards, drinking from time to time, and talking about anything other than art. “You remember Willie Mays, the baseball player?”

Tsuchidana says. “[Satoru] was so intrigued by him.” “Why?” I ask. “Well, because he was the best.” This support system for a bunch of Asian guys from Hawai‘i proved essential for their growth as artists in a place that occasionally alienated them. Periodic bouts of prejudice were combated by potluck dinners with the gang.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

for inquiries: 808.728.6143 dson808@gmail.com @dson_woodinc Wood, Inc. custom handcrafted furniture by DAE W. SON woodinchi.com

“All of his art is about growth, the things around us like the moon, the trees, the roots,” says Abe’s only daughter Gail Goto, who has shared her father’s

home since 1988.

Kaimukī

Even in their 80s, Harry Tsuchidana and Satoru Abe are still creating new works every day. “I always believe that if you create continuously, you evolve,” says Tsuchidana, shown

in his Salt Lake studio.

Tsuchidana moved back to Hawai‘i in 1959 after receiving the John Hay Whitney fellowship, which granted him $2,500 (roughly $20,000 today) to further his studies in art. By this time, his paintings had evolved from abstract figures to studies in balance inspired by “Mondrian’s horizontal line,” a style he continues today. When Satoru returned to Hawai‘i in 1970, he was a well-established artist. “It was a perfect time for him, just ripe for him to have commissions,” says Tsuchidana, referring to the establishment of the State Foundation on Culture and the Arts and its Art in Public Places program, which dedicated 1 percent of construction costs for new state buildings to the arts. Because of this, Satoru’s sculptures grace many of the state’s most prominent buildings, including Honolulu International Airport, Aloha Stadium, and dozens of public schools and colleges.

Decades later, Satoru and Tsuchidana are still creating work every day; Satoru, grinding and soldering in his garage in Kaimukī; Tsuchidana, up at 3 a.m. to draw and paint at his apartment in Salt Lake, where dozens of large canvases fill one room and what must be tens of thousands of drawings neatly stored in plastic bins and Longs plastic bags fill another. “I always believe that if you create continuously, you evolve. Bumpei Akaji once said to me that I’m producing too much, but I don’t feel that way. The fact that I draw every day—I’m all greased up.” He and Satoru both.

SATORU: THE FATHER

“The bridge column, National Geographic, the Smithsonian—he always reads that cover to cover,” Gail Goto, Satoru’s only daughter, tells me from the kitchen of the Kaimukī home she has shared with her father since 1988. “J-dramas—we always watch our J-dramas together.” Around us is evidence of a life spent in support of other artists. Satoru’s work, which overflows from bookshelves and bathroom closets, sits alongside pieces he’s bought from friends (an enormous wood vase by Jerry Okimoto, small ceramic pots by Toshiko Takaezu) and aspiring artists (a portrait of Satoru painted

by Kamea Hadar, a trail of ants on canvas by Otto) alike, filling just about every spare space of their home.

Since Satoru was forced to forfeit his driver’s license the previous week, on his 88th birthday, Goto has become the unofficial chauffeur for her dad’s busy schedule, taking him to an art opening at Kapi‘olani Community College’s Koa Gallery, yoga on Thursdays, art drop-offs around town. The relationship between father and daughter has strengthened over the years; Goto remembers growing up as the only child of an artist father, which was like anyone with a parent preoccupied with an all-consuming job would. Even when he wrote letters to his daughter while she was in architecture school, he would sign it, “Satoru.” “I guess he didn’t know his place in my life then. It was just ‘Satoru,’ not ‘Dad.’ … You feel a little shortchanged when you’re younger, but as you get older, you realize that’s why he’s good at what he does, because he devoted all of his effort into doing what makes him what he is.” What he is, Goto realizes now, is kind. “He always thinks about other people. And sometimes that, in my viewpoint, shortchanges him, but from his standpoint, he doesn’t feel like he’s being disadvantaged. He used to tell me, ‘Gail, in life, it’s better to be taken advantage of than to take advantage of people.’”

Her father’s kindness was in no shortage when it came to Ruth, the love of Satoru’s life. The budding romance began while they were attending Art Students League in 1948, and despite being an artist herself, “everything my mom did was in support of my dad,” says Goto. They moved back and forth between New York and Hawai‘i before eventually settling down in a Quonset hut in Mākaha after Satoru received a grant from the Hawai‘i State Foundation on Culture and the Arts in 1970. “My mom said those were the best years of her life,” Goto recalls. “Large acreage, farming, and the outdoors— my mom loved going to Pokai Bay and swimming.” But not soon after they moved, Ruth suffered an aneurysm, then a stroke, and the other debilitating effects that come with trauma to the brain. Now, it was Satoru’s turn to support his wife, which he would do for the next 13 years. “It was

really hard on my dad because he was the one solely taking care of her,” says Goto. “I think he really missed her when she got ill and passed on.”

As we talk, Satoru is busy in the garage, working on his latest commission for a residential tower in Kaka‘ako. “All of his art is about growth, the things around us like the moon, the trees, the roots,” says Goto of what she refers to as “additive art.” “It’s about the addition of stuff, reusing and fashioning the drop-offs—what he calls the cutouts—into new sculptures. … What he has is something that we all want to be and do, and that’s to be better.”

SATORU: THE SUBJECT

“The piece that Satoru has in his yard,” John Morita begins, referring to a large bronze sculpture originally meant for a Hiroshima memorial. “That is …” he trails off before nodding his head solemnly and giving a thumbs-up. “It’s got all the elements: sophistication, size, significance, all intertwined—friendship,” he says of what he calls one of Satoru’s few political pieces, a departure from his mostly noncontroversial subject matter.

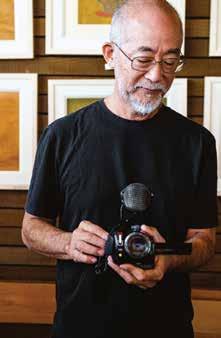

Morita, who studied photography and printmaking in San Francisco, knows a thing or two about political art. He spent years documenting the First Palestinian Intifada, an uprising against Israeli occupation in the region, in the 1980s. Mainly though, art to him is about telling a story, a notion he has remained fervently dedicated to regardless of the medium or message. One of his ongoing projects is documenting an artist family in San Francisco—for more than 40 years.

Morita’s fascination with Satoru’s story began in 2008 after he attended a gallery opening Satoru arranged for his friend, the late Jerry Okimoto. He became curious about the kind of person who would be entrusted with the selling of 16 of Okimoto’s ceiling-high wooden sculptures, for which he took no commission. “The family thought Satoru was the only person who could sell it for them,” Morita says. And he did. “The state foundation purchased a couple, the city purchased a couple, his friends purchased a couple—I think he’s got only a few left that

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 59

SATORU: THE SELLER

SATORU: THE MAN

haven’t sold.”

Since then, Morita has spent nearly every Saturday for the past six years visiting Satoru’s gallery, capturing the comings and goings of the diverse group of people who pass through. He has trailed Satoru at art openings, award ceremonies, and his home, casually pointing a handheld camcorder in the direction of anyone who might have a provocative clip. The 106-minute rough-cut edit of a documentary is shaky at times, but the picture that emerges in Morita’s years-long slice very clearly portrays a man who cares in earnest about the success of the people around him. In the video, Satoru is seen giving a critique to a young girl’s drawings of elephants, purchasing the work of his mentor Isami Doi, going the extra mile for a friend. “I have to sand about 20 pounds more,” Satoru is seen saying as he grinds away at a 90-pound clam sculpture made by Okimoto. “Lots more grinding to do to get it finished so I can sell it for him.”

Walter Dods, the former chief executive of First Hawaiian Bank, has close to 100 Satoru Abe pieces in his personal collection. This includes one of the artist’s most iconic, which he can enjoy every day: Placed at the crossroads of commerce at the corner of King and Bishop streets, “Eternal Garden,” five large tree-like sculptures fashioned from bronze, sits in front of First Hawaiian Center, where he still has an office with a view. It’s kittycorner from a piece by Bumpei Akaji and by no accident. Across the street, in Bishop Square, is a work by English sculptor Henry Moore, while another by Bernard Rosenthal stands at the Bank of Hawaii building. “I wanted to get the local boys back in balance,” says Dods. Despite the many pieces that fill his home and office, as well as the Honolulu Museum of Art partnership gallery in the lobby of First Hawaiian Center, which he established, Dods initially had to be dragged “kicking and screaming” into the art world. “I was a Saint Louis High School grad who had no culture in my background,” says the Kuli‘ou‘ou-raised Dods. But once his friend Wesley Park forced him to take a look, he couldn’t turn his eyes away.

“The work of this group was forged under the stress and fire of the Second World War,” says Dods. “I hope other groups replace them, but it’s hard to find that. … In terms of sculpture, I’d say Satoru was one of the top three or four to come out of Hawai‘i and just a special human being.” For Dods, it’s essential that the arts continue to be supported. “Art and culture is the soul of a community. … You have your social problems—housing and homeless are critical issues—but I don’t see them as mutually exclusive [with art]. … Hawai‘i lacks a vibrant arts and culture community, but what we do have is special, and we need to nurture it.”

Two weeks after Satoru initially declined my interview request, he’s finally ready to talk. “The birth certificate says that I was born 88 years ago, but for me, life started 66 years ago, in 1948, when I said I gon’ be an artist,” he says. “The first 10 years, all struggling. I don’t know what I doing, basically, but lot of emotion in the work. And the composition was poor; the technique and the colors were poor. But after that, one day I realized that I’m very unique, that if I don’t create these things, they’ll never be existing in the world. So that’s the ego that keep me going. Today, I make things without preconceived ideas. I just pick up the metal and wood and start. Along the way, your sensibility comes into play. But when I finish the work, I still surprise myself, and that’s my biggest joy.”

Despite his age, the artist continues to work with vigor. “I think I’m good for two more years,” says Satoru, who long thought he would die at 88, a most auspicious number. “I reach 88, so now I’m getting greedy; I want 90.” With a recently renewed passport good until 2024, Goto suggests her father will be here until he turns 98. “No, no, no, I’m not up for the Guinness World Record. I don’t want my last years to be—” he says, making a choking face. “See for me, if you’re not productive, doesn’t make sense living. … But little secret, I think, is you can almost live as long as you want to. If your mind is there, I think you can.”

Ten years from now, it’s hard to say with certainty what the art scene in Hawai‘i will look like or what legacy Satoru will leave behind. All this is of little importance to Satoru. Despite a lifetime dedicated to the arts, at the end of it all, Satoru wants to be remembered simply “as a good man.” If the last six decades is any indication, when we all look back in the years to come, what we see will be great.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

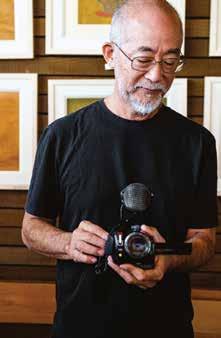

Storyteller John Morita has been documenting Abe for nearly six years.

ORCHID RUNNERS

A NEW EVOLUTION OF ORCHID ENTHUSIASTS TAKES ROOT AND BREATHES LIFE INTO THE SEDATED SCENE.

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

TEXT BY CARMICHAEL DOAN | IMAGES BY AARON VAN BOKHOVEN

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 63