WINTER 2014

ISSUE

The Film

22

NEW WAVE CINEMA

Sundance Institute’s Native Lab Fellowship is helping indigenous filmmakers reshape Hawai‘i’s cinematic arc. From a director who fought her way back to the top to a filmmaker who refused to let life knock him down, featured here are five journeys of life and Sundance.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES |

36

SOUNDING THE PŪ

Since 2009, ‘Ōiwi TV has been transforming the way viewers think about language, media, and indigenous identity in Hawai‘i. Tina Grandinetti sits down with co-founder Keoni Lee to uncover how the Hawaiian television station is utilizing technology to perpetuate the Hawaiian culture.

44

THE SHOW MUST GO ON

Editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden recounts the tale of how the Hawaii International Film Festival has grown to become the state’s largest arts event over the last three decades, bringing world-class cinema—and a bit of glamour—to the isles.

52

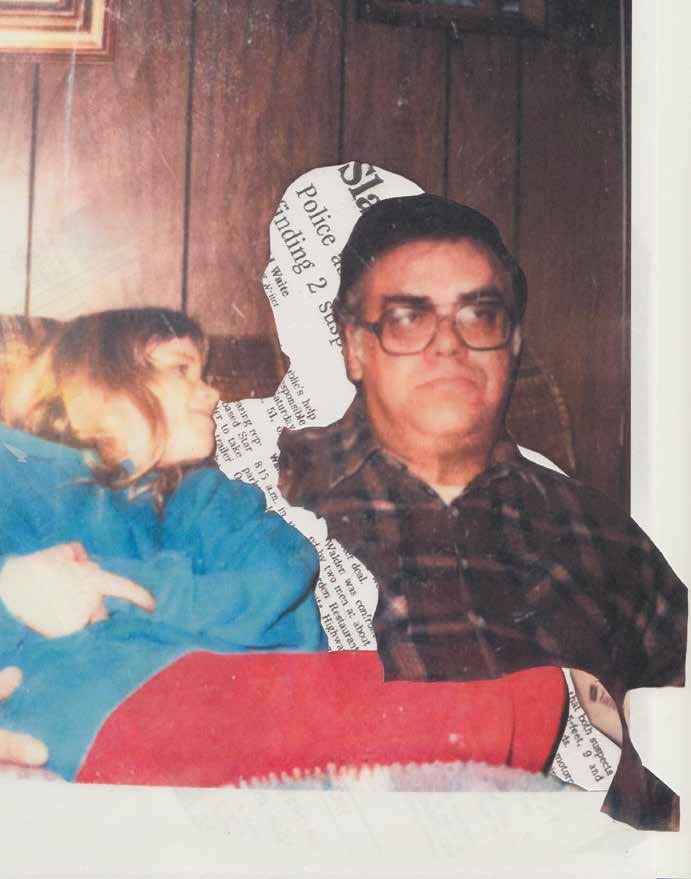

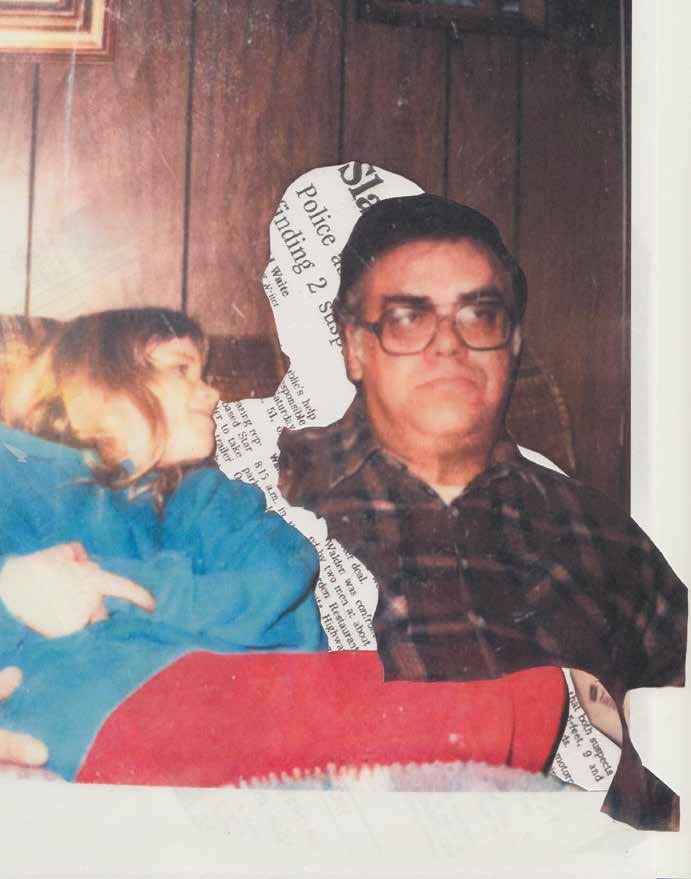

DRIVING FACTORS

In 1994, a murder at a Hawai‘i dock sent shock waves through the local film and television industry. Reporter James Dooley, who covered the beat in the years that followed, gives a rundown on the case that still remains unsolved.

56

A WRINKLE IN TIME

On what begins as a dark and stormy afternoon (eventually turning into a perfect day in paradise, as it so often does) our heroes find themselves caught in a wrinkle between space and time in this fashion editorial shot by John Hook and styled by Aly Ishikuni.

4 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Native Lab fellow ‘Āina Paikai shown at the Marine Education Training Center, home to the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

22

Showdown in Chinatown has inspired Hawai‘i auteurs for a decade. Shown here is the film challenge’s director, Cyrina Hadad.

EDITOR’S LETTER CONTRIBUTORS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

LOCAL MOCO: VICTORIA KEITH AND THE SAND ISLAND STORY

ARTS : UNDER THE BLOOD-RED SUN

ARTS : GORDY HOFFMAN

HOMECOMING: DANA LEDOUX MILLER

HAWAII FIVE-OH WELL

ARTS: CYRINA HADAD OF SHOWDOWN IN

80

MUSIC : STREETLIGHT CADENCE

82

MUSIC: AMY HĀNAIALI‘I GILLIOM & WILLIE K

96

A HUI HOU: MOVIE THEATERS LOVED AND LOST

STARFRUIT

STYLE : SURF BOUTIQUE

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

19

65 TV:

68

STATE OF FLUX

70

CHINATOWN

72

74

76 FOOD:

78

68

Streetlight Cadence serenades passersby.

80 74

Academy for Creative Media alum Dana Ledoux Miller in Los Angeles.

STARFRUIT DEVELOPERS

Starfruit is full of nectar, simple to juice, and abundant when in season, which makes it perfect for a caipirinha cocktail, as suggested by chef John Memering. Get the recipe at fluxhawaii.com.

Photographer John Hook captures this moment of Drew Seibert caught between space and time at The Nutridge Estate atop Tantalus. See the rest of the images on page 56.

There are few places in the world where film can be developed beachside. Luckily for us, Hawai‘i is one of them. Check out this behind-the-scenes clip by Philip Lemoine of Chris Rohrer processing images in his Volkswagen Vanagon at Irma’s surf break on O‘ahu’s east side.

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | FLUXHAWAII.COM | ON THE COVER:

WE MAY BE A QUARTERLY, BUT WE’RE BRINGING STORIES ALL THE TIME ONLINE. Stay current on arts and culture with us at: fluxhawaii.com facebook /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii instagram @fluxhawaii

EDITOR’S LETTER

Film is transformative. It can rouse those watching it—make them laugh, make them cry, make them fume—as well as alter those making it. Not only does it capture moments in time, it has the power to incite social change, heal the broken, and uplift the downtrodden (one might even call it miraculous). Film carries cultures over seas to shores far, far away; ultimately, it can show us “how we’re different but ultimately the same,” as producer Beau Bassett says.

The resounding theme of this issue is the importance of the story, the importance of our story, and the necessity of sharing it with the world. “Our society is broken right now,” ‘Ōiwi TV co-founder Keoni Lee says. “The more we can get people ... to be supportive of an indigenous worldview that emphasizes balance between other people and the environment, the better off we’ll be”—the better off the world will be. Thankfully, cinema in the isles is blossoming like never before. No longer content to let the world tell their stories for them, local filmmakers are reclaiming that which they hold so dear, seizing opportunity, and fighting against all odds to bring their narratives to screens both big and small.

While cinema is the focal point in this issue, we can’t forget about film in photography. The features and profiles in this issue were shot on a variety of black and white and color film, most of which were processed by hand in garages, studio apartments, even on the beach. Despite the collapse of the film industry, starting with Eastman Kodak’s bankruptcy filing in 2012 followed by the selling of its iconic film portion a year later, analog seems to be experiencing a renaissance, even if only in small circles. We remain optimistic about the evolution of the film industry into something new, subscribing to the view of media theorist Marshall McLuhan, who said, “Old technologies become today’s art forms.”

As we anticipate exciting new futures for film in Hawai‘i—both cinematic and photographic—I leave you with this quote by the late Roger Ebert, published in his last blog post in 2013: “Thank you for going on this journey with me. I’ll see you at the movies.”

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| FLUX

MAGAZINE |

HAWAII

Ara Feducia photographed ‘Ōiwi TV staff in action on Ektar 100 film, as recommended by Bobby Asato, owner of Treehouse. The staff was working on their second “Project Kuleana,” a music video promoting Hawaiian culture featuring a handful of the islands’ most prominent musicians. “Being around a group of people speaking in fluent Hawaiian was a learning experience,” she says. Another was predicting how the light changes throughout the day. “All in all, what I enjoy most about shooting on film is discovering how the candid shots will look after they’re developed.”

JONAS MAON

Jonas Maon shot the portrait of Streetlight Cadence using an expired roll of Kodak T-MAX P3200 black and white film.

“I’m totally not used to shooting with film, let alone shooting with film at night, so I was happy that Eric at Treehouse had recommendations for what I should try,” he says. “Using film definitely slows me down when I’m shooting since I don’t want to waste any frames, and it prompts me to not just rattle off shots like I would with a DSLR.” Call him nostalgic, but Maon appreciates the unique visual quality of film. “After all,” he says, “given the chance, I’d still prefer to pick up a book in print over an e-book.”

John Hook shot the portraits and fashion editorial in this issue with Kodak T-MAX 400 black and white film, Lomography 400 color film, and one roll of Kodak Portra. “With film, I had to get comfortable real quick and not waste,” says FLUX Hawaii’s photography director. “One of the portraits I shot, I showed up with only four frames left on the roll—don’t ask my why I didn’t bring more film—but we made it work.” Of developing, Hook says, “It’s like you’re playing a slot machine, or carrying someone else’s baby. I feel like somehow I’ll find a way to mess it up. But once the negatives come out developed, and you have frames visible on the roll and the exposure looks good, you feel like a rocket scientist.”

Aaron Yoshino shot the portraits of the Hawaii International Film Festival staff on Ilford Delta 400, and the portrait of ‘Ōiwi TV’s Keoni Lee on Fujifilm Neopan 400 (two of his favorite black and white films), all on his first camera ever, a Nikon FE. Yoshino also developed and scanned all his film and calls the process nostalgic. “It’s also time-consuming and kind of boring but in the best possible, Zen kind of way,” he says. Yoshino has been a freelance photographer for 16 years, the first five of which he shot analog. “If done correctly, shooting film is very similar to shooting digitally. It’s only unpredictable if you allow it to be.”

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| FILM |

CONTRIBUTORS

ARA FEDUCIA

JOHN HOOK

AARON YOSHINO

ABOUT THE DEVELOPERS | MASTHEAD

NATALIE NAKASONE

Natalie Nakasone developed the film shot by Jonas Maon from her home darkroom, Darkslide Laboratories, where she processes small custom orders of black and white film. “My darkroom has taken many different forms over the years—a college communal lab, an ex-boyfriend’s spare closet, a coworker’s kitchen sink,” she says. She graduated from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa with a BFA in photography and works as a freelance photographer and photo assistant, though her lab is her dream. “It’s the thing that all my jobs pay for, the thing that keeps me awake at night and gets me out of bed in the morning.”

CHRIS ROHRER

For this issue, Rohrer developed and processed all John Hook’s film in his Volkswagen Vanagon, which he converted into a darkroom. He has been collecting equipment with friends in hopes of opening a community darkroom, but since the van costs less, it does the trick for now. The film was processed out at the surf break Irma’s, where in the pitch-black of night, the beach essentially became the darkroom. Rohrer, who also shoots film photography, remains entranced by the medium.

“I’m pretty sure I’ve never heard people ‘oooh’ and ‘ahhh’ over a print coming out of an inkjet printer,” he says, “but seeing a photograph slowly develop has a kind of magic to it.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

FASHION EDITOR

Aly Ishikuni

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

COPY EDITOR

Andrew Scott IMAGES

Mark Ghee Lord Galacgac

Nick Joseph

Jonas Maon

Haren Soril

Landon Tom

Aaron Yoshino

Jonas Yun

CONTRIBUTORS

Matthew Dekneef Carmichael Doan

James Dooley

Beau Flemister

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Sarah Ruppenthal

Liza Simon

Naomi Taga

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns VP MARKETING & ADVERTISING keely@nellamediagroup.com

Bryan Butteling BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT bryan@nellamediagroup.com

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR

gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR

jill@nellamediagroup.com

Matt Honda CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Michelle Ganeku JUNIOR DESIGNER

INTERNS

Jourdan Au Young

Kaycee Macaraeg Carrie Shuler

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2009-2015 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

|FILM

|

UPDATE:

In our last issue, Jeff Mull wrote a piece about public solutions to address the issue of homelessness in Hawai‘i. At the time, two sit-lie bills, which would have made it a crime to sit or lie down on streets or sidewalks in Chinatown and Waikīkī, appeared to have stalled. The Waikīkī bill received a second life in September, however, when Mayor Kirk Caldwell signed the ordinance into law as part of his “compassionate disruption” campaign to end homelessness, along with two other bills that prohibit public urination and defecation. “These bills are saying number one, our sidewalks in our great district of Waikīkī are made to traverse on,” Caldwell said in a KITV story. While the city continues wrestling with viable solutions, including various Housing First initiatives and the establishment of a temporary homeless camp in Sand Island, we want to know what you think about the city’s attempts. What do you think should be done? Share your thoughts with us.

I am originally from Hawaii but now reside in San Diego. I was really happy to find a copy of your magazine. It reminded me about all the things I love about Hawaii, especially the story on Kimo [Kahoano]. I remember small kid days watching him on Hawaii Stars with Carole Kai. What it really reminds me of though is dinners at grandma’s house, when we’d all be tuned into the show. Everyone would potluck and bring the dish that eventually would become their specialty and that everyone would look forward to. It reminds me of my aunty’s sweet sour spareribs and my uncle’s special spaghetti mac salad. Even though I’m thousands of miles away from Hawaii, your magazine brought a piece of home to me here on the mainland.

Mahalo, James Bailey

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM LETTERS TO THE EDITOR | FILM |

@discotraveler “Afternoon #BigIsland coffee and @fluxhawaii reading. #bliss #rainydays #hawaii #fluxhawaii #magic”

WE WELCOME AND VALUE YOUR FEEDBACK. SEND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO: LISA@NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM OR MAIL TO FLUX HAWAII, 36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A, HONOLULU, HI 96817.

LOCAL

MOCO | VICTORIA KEITH |

THE SAND ISLAND STORIES

YOUTUBE IS GIVING VICTORIA KEITH’S 1980 DOCUMENTARY ABOUT SAND ISLAND A SECOND LIFE.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON | IMAGES COURTESY OF VICTORIA KEITH

Sand Island is a small island off the coast of O‘ahu that is connected to Honolulu by a four-lane bridge. It has gone by several monikers over the last few centuries—Sand Island is only the most recent, following Mauli Ola, Quarantine Island, and Ānuenue, or Rainbow Island. It has received its fair share of affections and abuses over its lifetime. To name a few, it has been home to Native Hawaiian fishing grounds; an internment camp holding Japanese Americans for a brief time during World War

II; and the location for our current wastewater treatment plant. By 1979, when documentary filmmaker Victoria Keith and her partner Jerry Rochford of Windward Video turned their cameras on it and its residents, it was called Sand Island, as crooned about in the opening song accompanying Keith’s grainy color film: “There’s an island, by the sea. Beautiful Sand Island, beautiful Sand Island.” It is an adaptation of “Beautiful Hawai‘i” by Sand Island resident George Cash, who lived there with family.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 19

I came upon The Sand Island Story in the comments section of a Civil Beat story about the August 2014 proposal to use a parcel of land on the island as a Housing First transition center for the homeless population being displaced by a newly passed sit-lie bill for Waikīkī. Shortly after, a friend posted the documentary to my Facebook wall. Somehow, this film that was over 30 years old had made its way to YouTube and was still raising awareness of a significant time in the island’s history. Here is what I learned: In 1979, a small, predominantly Native Hawaiian fishing community that had moved onto the public land, creating homes amidst what many considered dumping grounds, fought against being evicted by the state. They had been deemed squatters, and plans made for a park along the shoreline were moving forward. It is a story that is still hard to watch, regardless of whether or not viewers believe the community was legally entitled to its oceanfront residence.

Keith and Rochford were contracted by University of Hawai‘i to document the Sand Island happenings for a small project, but when they arrived, they knew they would be sticking around longer. “We got down there and met all the amazing people there, saw all the amazing things they had done to survive,” says Keith. “We went down there every day until the evictions, then a little bit afterwards.” A rough edit of the film was widely shared, and after receiving a grant from the Corporation of Public Broadcasting, Windward Video was also able to create a final 28-minute edit that aired nationally in 1981 on PBS and in Hawai‘i around the same time.

A few years ago, Keith donated the original footage of all of her work to ‘Ulu‘ulu, a project by the Academy for Creative Media at UH that preserves photography and film that relate to Hawai‘i’s people and its rich heritage. This includes every film she made as part of the Windward Video duo and on her own—such as Back to the Roots, a documentary about the culture surrounding taro and water and land issues affecting its future—along with 60 tapes of the raw footage from Sand Island. However, having been recorded on actual film, everything was aged; Two Green Valleys, the oldest documentary, had rotted on the shelves

and was missing large chunks of audio. (Filmed in 1975, Two Green Valleys was the first film she and Rochford made and was about successful grassroots efforts to prevent the eviction of farming families from agricultural land to make way for development within Waiāhole and Waikane valleys on O‘ahu.) She mailed the tapes to a studio in Kentucky to be restored, a complex process that includes putting the 1/2-inch reel-to-reel tapes in the oven at 200 degrees, and the results were dramatically improved digital renderings. “Because of that, I wanted to put Two Green Valleys up for the Waiāhole people,” she says.

Two Green Valleys became the second of numerous documentaries she uploaded to YouTube starting in early 2013; the first was The Sand Island Story. “I’ve always had people trying to get in touch with me, especially about The Sand Island Story,” says Keith, who still hears from people watching it for the first time, or rediscovering it. “They said that family had been in it and they hadn’t known about it until they saw it on YouTube.”

Keith got into documentary filmmaking after having two daughters and teaching at Castle High School. She returned to UH Mānoa to study journalism, and while she was there, worked with her former Castle students on a project that eventually turned into Two Green Valleys. She made the film with equipment borrowed from the department and edited at public libraries, which at the time, had three or four editing studios open to the community.

After 20 years of working second jobs and chasing grants to fund documentaries, Keith returned to teaching full time. She still keeps in touch with one of the familiar faces in The Sand Island Story, Puhipau, a man recognizable by his striking white beard who was then known as Abe Ahmad. After his experience at Sand Island, documented in an essay in the recently published book A Nation Rising, he decided to become a storyteller through film as well, joining forces with video producer Joan Lander, whom he met during the editing of The Sand Island Story, to form Nā Maka o ka Āina.

By early 1980, the homes on Sand Island were gone. Many of the island’s

nearly 400 residents chose to relocate beforehand; George Cash burned down his own structure before the Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources could destroy it. A handful of the community stayed even as their homes were bulldozed to the ground. Today, with the potential of a homeless population being relocated to a dirt lot alongside Sand Island’s main road, it all seems surprisingly relevant. Perhaps someone will record the story, captured in a series of 15-second Instagram posts, or, possibly, a 15-minute Vimeo video with its post-production funded via Kickstarter. Perhaps it won’t be documented at all. As for the story itself: Maybe Sand Island’s next chapter will be a surprising tale of success. Maybe, as others predict, it will be another black mark on the history of how Hawai‘i treats its most vulnerable community members. Whatever happens, until rising ocean levels slowly erase it from our shores, Sand Island will be there to meet our needs.

“It’s calling, calling to me. Beautiful Sand Island, beautiful Sand Island,” continues Cash’s song. “In the midst of all the garbage, mother nature made my home. By the shores of Sand Island, maybe won’t last too long.”

Visit fluxhawaii.com/sandisland to watch the documentary. To learn more about Keith’s documentaries, visit victoriakeith.com.

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Previous page: Victoria Keith interviews Native Hawaiian sovereignty activist LaFrance Kapaka-Arboleda for the 1987 documentary Hawaiian Soul . This page, above: Victoria Keith (second from left) and crew with taro grower Sam Mock Chew in Waipi‘o during the filming of Back To The Roots in 1994; below: Joan Lander and Puhipau record Keith’s interview of Kaua‘i lawyer Chris Kealoha for Hawaiian Soul , co-produced by Naomi Sodetani.

Previous page: Victoria Keith interviews Native Hawaiian sovereignty activist LaFrance Kapaka-Arboleda for the 1987 documentary Hawaiian Soul . This page, above: Victoria Keith (second from left) and crew with taro grower Sam Mock Chew in Waipi‘o during the filming of Back To The Roots in 1994; below: Joan Lander and Puhipau record Keith’s interview of Kaua‘i lawyer Chris Kealoha for Hawaiian Soul , co-produced by Naomi Sodetani.

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

NEW WAVE CINEMA

SUNDANCE INSTITUTE’S NATIVE LAB FELLOWSHIP IS HELPING INDIGENOUS FILMMAKERS RESHAPE HAWAI‘I’S CINEMATIC ARC.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN , TINA GRANDINETTI , KELLI GRATZ , AND LISA YAMADA

OPENING IMAGE BY ARA FEDUCIA | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Mystical, relatable, inherently valuable— films are cultural artifacts that are telling of language, traditions, and infrastructure. Much like the multilayered images that make up a film, the inner workings of the Sundance Institute’s Native Lab Fellowship are intimate, stimulating, and convey beauty in the early stages of development.

From a pool of more than a hundred participants representing native communities, only four artists are selected to participate each year. In the past few years, several artists from Hawai‘i have been among those chosen for the fellowship, including Ty Sanga, ‘Āina Paikai, Beau Bassett, Ciara Lacy, and Chris Kahunahana. (The first chosen participant was Nā‘ālehu Anthony, who co-founded ‘Ōiwi TV. Read about his journey on page 36.)

“They are engaged at a particular level of writing and are able to collaborate with various creative advisors that help them tell the best version of their story,” says Bird Runningwater, director of Sundance’s Native American and Indigenous Program. “We create our own safe environment so that the deepest, most developmental work can happen,” he says. “It’s cathartic, personal.” From there, it’s up to the artist to bring their projects to fruition.

Runningwater has always been intrigued by this sense of narrative formed through imagery. From being a youngster on the playgrounds of Native American reservations in New Mexico to a journalism student at the University of Oklahoma, he’s had to navigate his way through different cultures spanning thousands of years. “I’m

half Cheyenne, half Apache,” he begins. “I remember going back and forth from my mom and dad’s reservation, trying to figure out how I’m going to speak both Apache and Cheyenne. But it was this level of culture each side had that fascinated me and continues to inspire me today.”

Runningwater got his start working for the Ford Foundation, managing its global fund initiatives, and then for Fund of the Four Directions, a private philanthropic organization owned by the Rockefeller family, before taking the job at Sundance. “I was well aware of this inauthenticity running through media,” he says. “But I also knew it was possible to present an authentic perspective. Our goal at Sundance is to find original, authentic, individual voices that we can get behind, to find that something we haven’t seen, while maintaining a certain level of artistry about cinema.”

Since his appointment as director, he’s been able to slowly build the global network of filmmakers to include those from Hawai‘i, Alaska, New Zealand, and other areas of the world. “When I first came to Hawai‘i, I saw some really interesting talents,” he says. “I connected with so many people. Right now we’re supporting our former fellows Ty and Chris to develop their features, as well as Beau and Ciara’s documentary about the Hawaiian prisoners who are being housed in Arizona. For some reason, a lot of talent is coming out of O‘ahu. There’s something really rich happening there.”

Because of this growing cinematic culture, next fall the Sundance Institute plans to bring its Shorts Lab, a half-day workshop dedicated to empowering the next generation of filmmakers, to the Honolulu Museum of Art. “Hathaway Jakobsen [the museum’s chief advancement officer] and I came together and thought about what we could do to serve the native community here,” he says. “In the Shorts Lab, we are able to meld the Native Lab support, where fellows can talk about their projects and experiences through the lab, and in turn inspire others.”

In the pages that follow, read about the journeys of Native Lab fellows Kahunahana, Paikai, Lacy, Bassett, and Sanga.

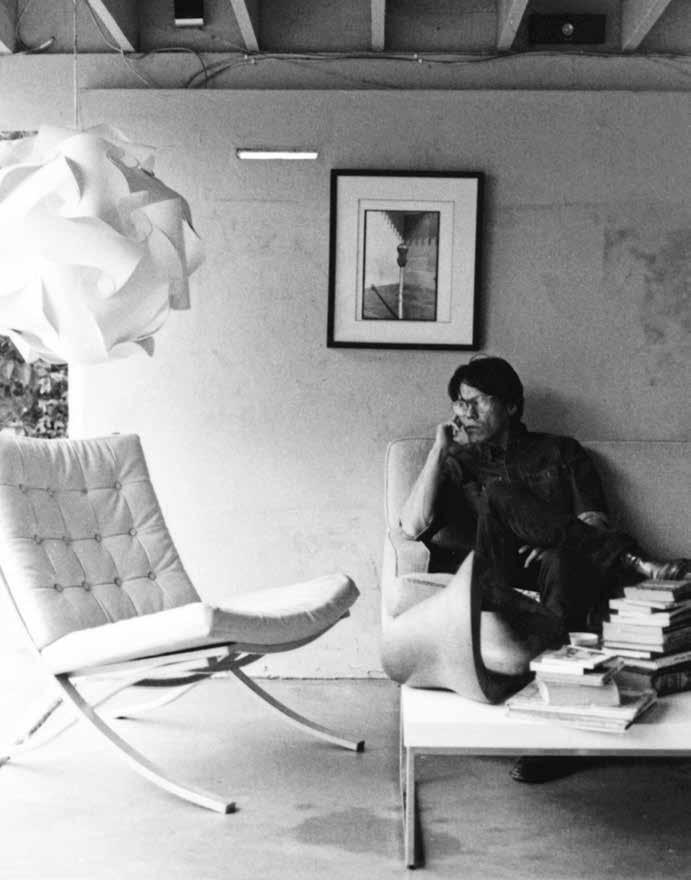

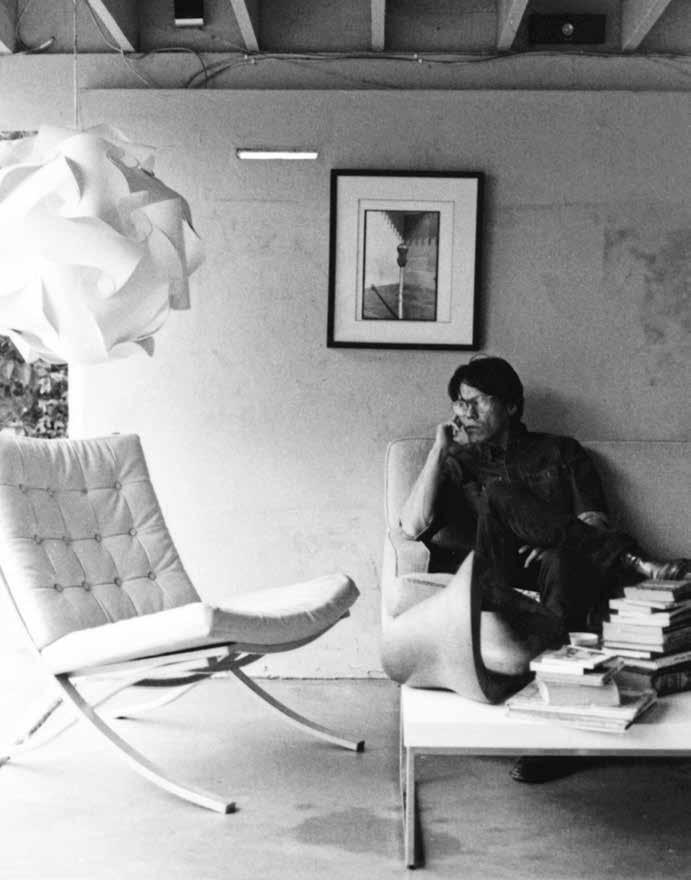

LAST MAN STANDING: CHRIS KAHUNAHANA

It’s the middle of a Tuesday, and Christopher Kahunahana orders another round of drinks at the Old Spaghetti Factory overlooking Honolulu’s Kaka‘ako waterfront. It’s a place long-forgotten by those without children, a self-contained universe replete with stained glass, a reconstructed trolley car, creaky wood paneling, and menu items dating back to Honolulu’s Frank Fasi administration. A place you think you know but you’ve got it all wrong about. “Brah, this place has cheap beer, AC, and look at the view,” Kahunahana remarks. “I used to work in a film lab right down the street.”

Handling chemicals in the dark room seems like a lifetime ago for Kahunahana. Most of Honolulu has a “Chris” story, and most of them were documented on nightlife blogs during the party renaissance that occurred in the city’s Chinatown over the last decade. After a childhood in Waimānalo and Kailua, the oldest of three siblings spent nearly a decade in San Francisco running a variety of clubs and galleries, then moved to New York, before making his way home in 2004 to open Nextdoor, an expansive night club on Honolulu’s Hotel Street with vaulting crimson brick walls, murals by visiting urban artists, and for most of its life, no air conditioning. When one co-owner left the business and another passed away in a tragic accident, Kahunahana found himself as the club’s sole owner, hanging on with low funds and lots of friends.

Check the old websites, and you’ll see Kahunahana running a club with liquor out of a backpack and a one-night license; zombie Kahunahana manning the door behind a repurposed church lectern; a beleaguered Kahunahana mopping a slippery dance floor after a famous DJ poured vodka down some club-goer’s hatch. For those who were in the scene, who unconsciously documented it in part because it was fleeting, it was the best city in the world. And it was Kahunahana’s disarming, self-effacing charm that made much of it happen, like a character out of fiction, or rather, animation. To see him as a filmmaker—a legitimate one with

“We had to interrogate if we identify ourselves as native artists, or as artists who happen to be native,” says Christopher Kahunahana of his experience with Sundance Institute’s Native Lab.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

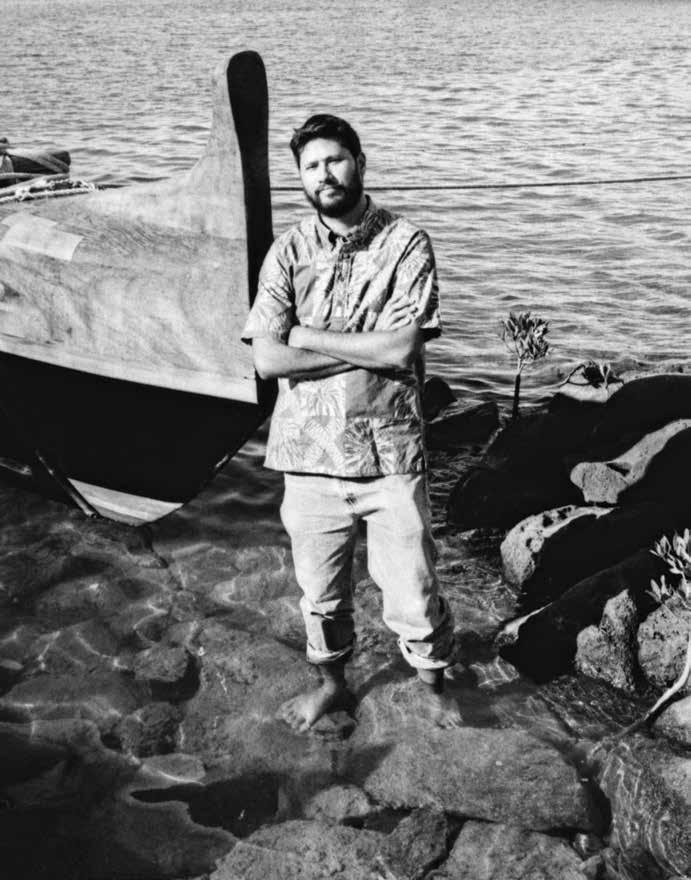

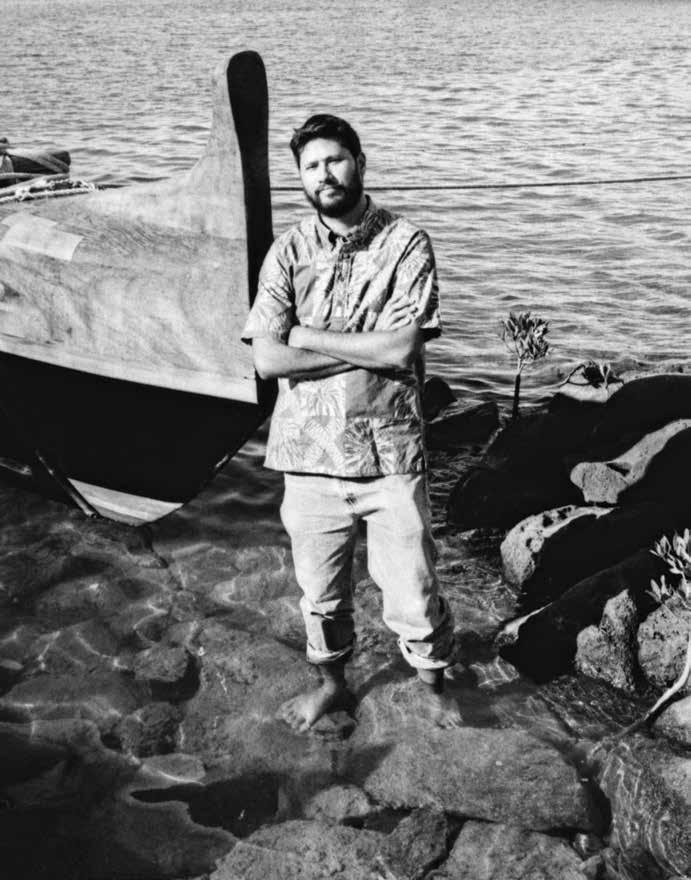

From comedic releases poking fun at local culture to everyday documentations of the Hōkūle‘a, ‘Āina Paikai’s “drama-dy” poses questions and plays with the future. Paikai is shown at the Marine Education Training Center, home to the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

From comedic releases poking fun at local culture to everyday documentations of the Hōkūle‘a, ‘Āina Paikai’s “drama-dy” poses questions and plays with the future. Paikai is shown at the Marine Education Training Center, home to the Polynesian Voyaging Society.

“First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.”

ambitions to take Hawai‘i’s cinema and Hawai‘i’s story to the world—is new to those who knew him from the parties and the scene.

But there was always another Chris, the guy in the daytime, who spoke quietly of Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman, who, when meeting strangers, introduced himself as a filmmaker. Kahunahana made eight films for Showdown in Chinatown, which originally took place at Nextdoor, a competition that gives local creators 24 to 72 hours to shoot and submit a short film based off a common theme. A few times, he won. Most often, he couldn’t make the deadline. “I could tell where I was artistically, even though they mostly sucked,” he says of the shorts. “I could see where my vision was headed and how I could become more refined.”

Then, opportunity struck. After he sold the club a year ago, Kahunahana began work on a script titled Lāhainā Noon, which takes its name from the local colloquialism for the summer solstice phenomenon when the sun passes directly overhead, leaving figures shadowless. The story follows a few local characters, as their shadows, acting as their subconscious forms, act out unspoken desires. This script, along with a feature-length one Kahunahana dubbed Karaoke Kings, became part of an application process that could further the dream; a chance at a fellowship with Native Lab. Sure enough, he and his screenplays were accepted.

Over the course of several weeks, Kahunahana was counseled by some of the best native filmmakers on the planet, such as Chris Eyre, who directed the 1998 movie Smoke Signals, and Runningwater, who has established native film labs around

the world. “When they said I was going to an Apache reservation, brah, I thought I was headed to a Hawaiian homestead for a workshop. They had us at this sciencefiction hotel in Mescalero [New Mexico] in the Inn of the Mountain Gods.” He was instructed to just take it all in, and later, to produce. “We had to really interrogate if we identify ourselves as native artists, or as artists who happen to be native,” he explains. The workshop shaped Lāhainā Noon, which premiered at the 2014 Hawaii International Film Festival. Kahunahana is currently developing Karaoke Kings, which he describes as “like Rocky but for karaoke in Honolulu,” about a guy trying to make his dreams happen. The truth is, being a club owner was a stepping-stone to the true vocation. Kahunahana has always been a filmmaker in waiting, and if he was authoring his own biography, Nextdoor might be a footnote, cited as the source of material for a new life of storytelling. But for filmmaking, there may have been no better a training ground. “This is more than just a film, it’s about managing, budgeting, running something with a lot of people,” he says.

Something about the story arc, about the redemptive capacity of arts and making hard work look fun, is reminiscent of Mahatma Gandhi’s famous counsel for agents of social change: “First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.” Kahunahana takes the last sip of his beer and amends it with experience: “Just keep showing up for long enough, and after everybody else self-destructs, you win!” he cackles with a gap-toothed grin. Then, he’s off to finish the last edits of the movie.

MOMENTS REIMAGINED:

‘ÅINA PAIKAI

His full name, Kamaninoka‘āina, meaning “the wind of the land,” was given to him by his father, who valued the importance of the land and all that it provides. “He wanted me to be like the wind,” ‘Āina Paikai says. “Free.” This free-moving mentality might be how Paikai is able to create such amusing and entertaining films, like Moke Action, a slapstick comedy about two guys looking to “scrap ova one broke slippah” (subtitled for the “Pidgin English challenged”), while remaining grounded in his identity. “I like to call it drama-dy,” he says. “It makes for an easy reaction for an audience.”

His name also appears as screenwriter, producer, and director alongside films including Nani Ke Kalo, which imagines what Hawai‘i would be like if the kingdom was returned, and The Great Heart of Waiokāne, a documentary about Edward Wendt, a Vietnam war veteran and advocate for Native Hawaiian rights who continues to battle Alexander & Baldwin over water diversions on Maui.

Historically, Paikai says film hasn’t been produced or told from an indigenous perspective. “I think it’s important to offer that perspective and insight,” the 30-yearold filmmaker says from the ‘Ōiwi TV headquarters in Honolulu, where he works as a photographer and editor. “I hope to make films that are impactful to Hawai‘i and worldly enough for all of us to enjoy.”

Paikai, who grew up in Pearl City, turned to video games and comic books as an adolescent looking for escape, and it was ultimately this fantasy realm that drew him into a career in media. He enrolled in the Academy for Creative Media at the

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27

University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and was captivated by the foreign films he watched in prerequisite classes. “Seeing films with the actors speaking different languages got me thinking about why there weren’t more films in Native Hawaiian,” he says. “That was really the spark.”

He quickly took to the indigenous filmmaking track under the wing of the late Merata Mita, a pioneering Maori filmmaker known for her work on Mauri (1988), Hotere (2001), and Boy (2010). “She always used to tell me, ‘Anyone can tell a story, but not in the proper way,’” he recalls. “She became one of my first mentors, and was the one who groomed Bird [Runningwater] into his current position. She even got me this job.”

He found further inspiration in indigenous movies like City of God (2002) and What We Do in the Shadows (2014), the kind of films that, he says, break the mold of what native movies are supposed to be. “The native film model … lacks authenticity. We are such a small group of peoples that it’s more than just being slid in as a minority group.” He began writing scripts in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, in the Native Hawaiian language, and quickly developed an approach to filmmaking that portrayed serious issues in a genuine but light-hearted way. One example is a workin-progress documentary he began while immersed in Native Lab. Out of hundreds of submissions, his script about the late George Jarrett Helm Jr., a Hawaiian activist and talented falsetto musician nicknamed “Da Frog,” was enough to win over the judging panel. “For me, he’s been a dedicated Hawaiian hero,” he says. “A lot of people don’t understand his story. He was a beautifully talented musician prior to his activism. I wanted to portray his love of

the land through his music. He overcomes his raspy voice, bullying from his brother, ultimately finding confidence for what he needed to do.”

Paikai is a fan of all genres, from dark depictions of humanity to comedic releases to everyday documentations such as that of Hōkūle‘a’s Worldwide Voyage, part of a series he’s helping ‘Ōiwi TV produce (he recently returned from documenting the leg of the trip from Tahiti to Samoa). He has an insatiable desire to pose questions, imagine scenarios, and play with the future. In his short film Blessed Assurance, he explores the question, “What if Hawai‘i ran out of gas? ” In it, a young man spends the day surfing, spearfishing, pounding poi, and walking everywhere because there are no running cars. Or, he poses in his film Nani Ke Kalo , if the Hawaiian Kingdom was reinstated, what would Hawai‘i be like in 30 years? According to Paikai’s imaginations, the language would be restored and only the elderly would speak English.

Asked if he’s ever surprised by how his films are received, he’s characteristically modest. “It’s for other people to define. If we keep the emphasis on the art, we can keep the integrity of film intact. My route is to keep putting stuff out there, and people will either enjoy it or not. Either way, it will help our culture along the way.”

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FOR VSP BOTTLE SERVICE, GUEST LIST AND GROUP RESERVATIONS: CONTACT INFO@ELEVEN44HAWAII.COM FIND US, FOLLOW US @ ELEVEN44HAWAII.COM

THE INCHES: CIARA LACY

Of all the plot narratives found in movies, there’s one that resonates with Ciara Lacy the most. “Oh, the comeback, right?” she says. “I’m a big believer in redemption. I don’t believe in waiting for somebody else to find our solutions. You have to find it yourself.” In discussing the comeback, it’s nearly impossible to avoid references to sports films. The now-famous locker room speech by Tony D’Amato, played by Al Pacino, in Any Given Sunday, immediately comes to mind: “We’re in hell right now, gentlemen. And we can stay here, get the shit kicked out of us, or we can fight our way back into the light. We can climb out of hell one inch at a time.” Emboldened, the team emerges from the locker room and goes on to win the game. While victory in real life is never quite as dramatic, the motifs in Any Given Sunday and such films are not unlike Lacy’s own.

Lacy grew up the daughter of a Native Hawaiian activist, and as a child, she remembers her mother hauling off her and her two siblings to protests and rallies. She remembers when her mother was arrested during the building of the H-3 freeway, where she and a few others had camped out in protest. “She just didn’t think it was right to build a freeway there, and when there’s something that doesn’t feel right, you do something about it,” says Lacy. “When I think back, I’ve definitely become like my mother in a lot of ways.”

As the valedictorian of her graduating class at Kamehameha Schools, Lacy was about as driven as they come. She went on to study psychology at Yale, receiving academic scholarships but still working three jobs to get by. The standout student, however, had other aspirations in mind. “I’ve always wanted to make music videos, ever since I was in high school,” says Lacy, who recalls sitting in her room entranced by directors like Michel Gondry, known as much for his music videos (a favorite of Bjork, The White Stripes, and The Chemical Brothers, among others) as his feature films (Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind). “But I didn’t tell anybody that’s actually what I really wanted to do in college,” she says. “I guess I was a little scared.”

After college, Lacy moved to New York, where she scrounged around the city

to make ends meet, temping, teaching SAT prep, even selling hot dogs. As fate (read: drive) would have it, she found a job with a small company that made rock ’n’ roll documentaries. “I would basically just prepare their Fedex packages, but I didn’t care, I was stoked,” she recalls. She later held jobs with Lion Television, where she worked on reality TV shows about wedding dresses and home security, and 44 Pictures, which produced large music productions, shooting concerts at Madison Square Garden and Radio City Music Hall. Her career was taking off. Then, a mysterious, debilitating illness brought her life to a jolting halt. She began getting pain in her hands, which she shook off as carpel tunnel. But then it got progressively worse, so much so that she was forced to move back to Hawai‘i. “I couldn’t carry my laundry, my purse, couldn’t work on a computer for a long period of time; I couldn’t really type; I could handle maybe one car ride a day,” she says, ticking off the painful symptoms delivered by what doctors called a careerending disease. “I was used to being independent. At 30, that’s when you want to be building your career … but here I was going to physical therapy, on painkillers, and no one could figure out what was wrong with me.” Doctors eventually diagnosed her with thoracic outlet syndrome, brought on as a result of a genetic malformation between her collarbone and rib and exacerbated by repetitive stress. “I was pretty depressed, I got fat, my attitude sucked. I just didn’t know what to do. I had my whole life back in New York.”

Lacy began seeing a physical therapist, one of her mother’s friends, who encouraged her to continue her work in film. “She threw out ideas all the time, and I was like, how am I supposed to do a documentary anyway when I can’t even carry a camera?” But eventually, one of those ideas stuck. “She told me about this very short piece done on these men dancing hula in an Arizona prison. I finally watched it,” Lacy recalls. “And I cried. … It was a really tough time for me, and in some crazy way, I thought—and this is gonna sounds nuts— but I had this thought of, oh, we could heal each other.”

The clip became the basis for Lacy’s feature-length documentary Out of State, as well as the platform for her application to

Native Lab in 2012, which Beau Bassett, a childhood classmate from Kamehameha as well as a Native Lab fellow, encouraged her to apply for. “I’d like to think that I’m openminded, that I’m progressive, but I had a lot to learn about my own prejudices going into making the film,” says Lacy, who applies this re-evaluation of herself to society as well. “Systems are often contextually based, so when our society changes, the way we approach things should change too, but that fluidity doesn’t always naturally happen.”

Today, Lacy is back at it, but this time at the helm, working daily with a crew of just two others to produce Out of State. Where her previous jobs entailed working on projects with structures and financing already in place, Out of State is a brand new experience, one that requires her to direct and produce, among the myriad of other tasks that go into bringing a documentary to life, like securing funding and distribution. It’s a project more than two years in the making, with production to wrap at the end of 2015. As Native Hawaiian filmmakers, Lacy and Bassett, who is helping produce the film, consider Out of State their “kuleana project,” one that both are willing to fight for. “It’s not something easy to do, but we are compelled to do it,” says Lacy. “Because how do you live if you don’t have hope? I think hope is what’s important to being human, and everybody deserves to have a little bit of that.”

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“How do you live if you don’t have hope?” wonders producer and director Ciara Lacy, who, despite suffering what she thought was a career-ending disability, is working to produce her first feature-length documentary.

“That’s one thing that is missing from Hawai‘i cinema, that voice that really makes it a point to say, ‘This is what’s so beautiful about this place; this is how we’re different but ultimately how we’re the same.’”

THE HUNT: BEAU BASSETT

In his dreams, Beau Bassett can see a boy—a younger version of himself—splashing through streams in Kahalu‘u on O‘ahu’s east side, where he grew up. He’s on the hunt, looking for the black and gold fish with which to fill his aquarium. “Ohhh, swordtails,” he recalls emphatically from the law offices of Pitluck Kido and Aipa in downtown Honolulu, where he works. “I still dream about them. They play out like films in my brain.”

Years later and Bassett is still on the hunt, but this time for narratives to produce. Bassett, who took part in Native Lab in 2008, fell into filmmaking by way of lawyering. “I got into law because I had all these ideas about social change that I wanted to see reflected, and I thought the law was the answer to fix it,” he says. After attending law school in 2005 and learning the process involved that actually leads to change, Bassett realized that policy was only as valuable as the populace makes it. “So much of our understanding and identities are formed not just by what’s in front of us physically but through media, and that was a big eye-opener.”

It was on a trip to Japan during his last year in law school that his future in filmmaking was affirmed. Wandering the streets of Tokyo, he saw a culture that had a firm grip on both its past and its present. He became fascinated by television programs similar to Soko Ga Shiritai on KIKU, which features everyday people

doing everyday things (abalone divers in Atami, turnip farmers in Shinanoji). “For it to be common to be able to turn on the TV and access that kind of information—where even the most modern Japanese young person who’s growing up in the city and creating their own identity can still tap into that traditional culture,” he says, “I thought how amazing it was to always have that informing their identity.”

It’s a notion that Bassett could easily identify with, growing up in the country but now living city life in Honolulu. “A lot of what inspires me is the constant tug at my spirit to address both needs, the old and new, the natural and synthetic,” says the Hawaiian-Chinese Bassett, whose childhood was marked by big family gatherings, fishing, and picking limu in front of his grandma’s house in Kāne‘ohe Bay. “I grew up loving it so much, and loving all the characters in my family really inspired me to want to tell the stories of my own family,” he says. “Then to meet different people and realize that every family is so different and yet we hold onto the same values—I feel like that’s one thing that is missing from Hawai‘i cinema, that voice that really makes it a point to say, ‘This is what’s so beautiful about this place; this is how we’re different but ultimately how we’re the same.’”

Bassett’s current project, Out of State, which he’s producing with Lacy, puts this challenge to the test. The film, which centers on Hawai‘i prisoners housed in Arizona correctional facilities who are learning to dance hula, is ultimately “about the ability

of culture and art, song, dance, chant, history, and religion to aid in rehabilitating the human spirit,” according to Bassett, “rehabilitating someone to find value in themselves.”

While he aspires to do more in local film, Out of State is about all he can manage between billable hours at the law firm. One can still dream though. With the islands’ freshwater resources changing before his eyes, Bassett is eager to do more in the medium he’s found most effective to preserve the areas that practically raised him. The limu he grew up picking, for example, is now long gone, choked out by foreign species. “A big part of my future is being more involved in preserving freshwater resources,” he says. “It’s really important to my upbringing that other people from the area be able to still experience that.”

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“So

much of our identities are formed through media,” says Beau Bassett, shown here in his downtown Honolulu law office, who got into filmmaking because he wanted to enact social change.

“When I got into filmmaking, I wanted to tell stories as messages,” says Ty Sanga, whose Emmy Award-winning show Family Ingredients will start its national run on PBS in 2015.

FINDING BALANCE:

TY SANGA

Ty Sanga is among a select group of filmmakers—Native Hawaiian or otherwise—who can call themselves Emmy award-winners. The food travel show pilot he directed, Family Ingredients, won a regional Emmy in 2014, and traces Hawai‘i’s family recipes back to their origins. His work has garnered praise from big-time film producers, critics, and audiences alike. His acclaimed Hawaiianlanguage short film Stones, which screened at Sundance in 2011, captivated audiences with its poignant portrayal of a couple living in isolation, struggling to accept newcomers. The noise from Sundance was undeniable.

Recently returned to Hawai‘i from graduate school at Chapman University in Orange County, California, Sanga couldn’t be happier to be back in the islands. Although the young filmmaker acknowledges that leaving the trappings of Hollywood, known as the filmmaking capital of the world, was tough, he realizes the importance of his return. Finding himself writing films solely about Hawai‘i, Sanga knew he needed to be in the place in which the stories were conceived; it was pointless for him to be anywhere else.

But contrary to all appearances, Sanga didn’t always want to be a filmmaker. His parents managed hotels in Hawai‘i, and he was headed in that route, studying travel industry management and working in hotels himself for five years. It wasn’t until he screened his first film at the Hawaii International Film Festival—Plastic Leis, about a young Hawaiian hula dancer’s struggle to find her roots—that he realized a career in film could be a reality.

As a child, Sanga spent the summers with his family in Los Angeles, where the disparities that existed between Hawai‘i and the mainland became apparent. “My cousins would tease me about my Pidgin accent, and it was there I really saw the differences in social and economic class,” he recalls. “But, my father would always tell me to be a proud Hawaiian … that I was Hawaiian first, then Filipino, and Chinese. When I got into filmmaking, I wanted to tell stories as messages.”

Sanga’s films tend to relay true experiences he had growing up in Hawai‘i,

eloquently weaving together heavy issues that face our islands while tapping into the lighter side of entertainment. His film Follow the Leader, about a boy growing up in Kalihi collecting basketball cards, “addressed racism and the divide between private and public schools,” says Sanga. Instead of straight historical storytelling, Sanga’s films are wandering narratives, echoes of legends, and thoughtful dialogue, spoken in native tongue by actors such as Moses Goods and Rava Shastid. They are inspired by the past but are retold in a way that reshapes our understanding of modernday society.

Part of what makes Sanga’s films so authentic is that they stray from the mainstream model. He credits his Native Lab fellowship, which connected him with Runningwater and other industry advisors, for giving him the tools to tell his stories the right way. “They want to invest in storytellers,” he says. “They want to help strengthen our voice and artwork and equalize the balance of what’s coming out of Hawai‘i besides Hawaii Five-0.”

Sanga speaks energetically about his current projects, including the continuation of Family Ingredients, which was recently picked up by PBS Hawaii to go national in May of 2015, as well as his documentary The Life of Pinky Thompson, the closing film at the fall 2014 Hawaii International Film Festival. “I have been working on it for four years, and I forgot how long documentaries take!”

Among his other works in progress is his feature film After Mele, which he began working on during his fellowship with Sundance. “It’s about my relationship with my father and brother. My father passed away when I was in high school, and growing up, we were disconnected from his side altogether. This film deals with what it means to be a native to Hawai‘i, what was expected of us, and how everything finds its balance.”

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

SOUNDING THE PŪ

‘ŌIWI

TV STRIVES TO HO‘O HAWAI‘I MEDIA, TECHNOLOGY, AND THE WAY WE RELATE TO OUR ISLAND HOME.

TEXT

TEXT

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 37

BY TINA GRANDINETTI | PORTRAIT BY AARON YOSHINO ON SET IMAGES BY ARA FEDUCIA

On a hot October day in Makiki, as the air begins to thicken with humidity, the noises of Ke‘eaumoku Street traffic are calmed by the bellow of the pū (conch shell). The staff of ‘Ōiwi TV gather outside their office and sing a mele as they look toward the hillsides that rise above the city.

E ku‘i e ka lono i o nā kai ‘ewalu, A lohea maka ka leo e ka nui manu Ua ala, ua laha, ua ‘ikea Ke aloha o nā pu‘u nui o Makiki ē

(Let the stories of Hawai‘i be heard Let them be heard by all Awake, widespread, and known Is the aloha of Makiki)

Since ‘Ōiwi TV went on air in 2009, its crew has worked in places many of us can only dream of, from the blinding white atolls of Papahānaumokuākea to the deep green hills of Fare Hape in Tahiti. But it is here, in a converted three-story house in Makiki, where the day-to-day work of this local production company happens. Schedule permitting, each workday begins with this morning piko, a kind of centering protocol that brings the staff together to oli and share some guiding mana‘o, or thoughts, for the day. The piko itself is a reminder that ‘Ōiwi TV is not your average production company, and the fact that it takes place in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, the native tongue of Hawaiians, is a statement that ‘Ōiwi is not just here to do things differently but to transform the way we think about language, media, and indigenous identity in Hawai‘i.

LOOKING THROUGH THE HAWAIIAN LENS

Hawai‘i’s relationship with film began in the years following World War II, when America’s paradisiacal darling began to grace the silver screen in South Seas films. Though the camera loves Hawai‘i—is perhaps, infatuated with it—historically, its relationship with kānaka maoli (Native Hawaiians) has been exploitative. For Hollywood, Hawai‘i is a backdrop, its people merely props for Western stories of love, adventure, and coconuts. More insidiously, the news media too readily turns to Native Hawaiians for headline stories of conflict (i.e. coverage of Representative Faye Hanohano’s outbursts at the state capitol; a Maui man’s rants to tourists on the beach; and Kamana‘ opono Crabbe’s dissenting letter to the very board he represents, the Office of Hawaiian Affairs), perpetuating a narrative plagued by negativity and deficit while ignoring stories of success and community.

For founders Keoni Lee and Nā‘ālehu Anthony, the idea for ‘Ōiwi TV emerged as a way to leverage the immense power of visual media and technology to change this paradigm and begin to tell Hawaiian stories from a Hawaiian worldview. ‘Ōiwi TV currently reaches more than 220,000 households via Oceanic Time Warner Cable’s Digital Channel 326 and engages a worldwide audience through its online and social media platforms. Lee and Anthony met as graduate students in Shidler School of Business at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa and completed their thesis project on the Polynesian Voyaging Society together. “We became good friends through that project, and when it was finished, we decided that one day we’d start something for the community,” says Lee.

“The idea for a Hawaiian television channel, a station for the nation, had been around for years,” he adds, “but in 2008, there was a perfect storm of opportunity.” Technology was getting cheaper, Kamehameha Schools was expanding its investments in the community, ‘Aha Pūnana Leo was partnering with KGMB to do Hawaiian language news segments, and Oceanic Time Warner Cable launched an interactive television program. Conditions were ripe to bring their vision to reality. Today, Lee and Anthony have come full circle, right back to

their graduate thesis project: ‘Ōiwi TV was asked to document the Polynesian Voyaging Society’s Worldwide Voyage onboard the Hōkūle‘a and Hikianalia. “It’s just another affirmation that we’re on the right path,” says Lee.

In the five years since going on-air, ‘Ōiwi has carved itself a unique position within the Hawaiian community. In addition to in-house projects like Nā Loea, which highlights masters in different areas of Hawaiian knowledge, ‘Ōiwi also contracts its services to clients looking to share their work through professional media. By using its platform to show that Hawaiian language and culture is thriving, ‘Ōiwi fundamentally challenges the dominant representations of Hawaiian people that too often devalue their knowledge systems and ways of being. “We get to tell the stories of our people,” says Lee, pausing for a second as if to savor that simple fact. “Hopefully, we’re the ones our community can trust to provide a fair and authentic representation of their stories.”

On top of the pressures faced by any production company in the cutthroat world of corporate media, ‘Ōiwi’s staff takes seriously the kuleana, or responsibility, of being accountable to community. That often means providing their services at deep discounts to community members who may otherwise not be able to afford high-quality, professional media and taking the time to meet with interview subjects beforehand, with cameras off, to answer all the “who yo’ maddah, who yo’ faddah, where you grad” questions that help us gauge an outsider’s positionality, genealogy, and relation to their work. But time and again, the folks at ‘Ōiwi seem to pull off this delicate balance. At this year’s Hawaii International Film Festival, ‘Ōiwi screened a documentary film about Hui Malama I Na Kupuna ‘O Hawai‘i Nei’s final repatriation of iwi (human remains) before the organization eventually disbands. The project presented unique challenges because the bones of kūpuna require a level of respect that is often difficult to maintain from behind a camera lens. “For Hui Malama to be able to trust that we would know how to act and tell such a sacred story was quite an honor,” says Lee.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The staff at ‘Ōiwi TV work on their “Project Kuleana” music video at UH Mānoa’s Center for Hawaiian Studies.

The staff at ‘Ōiwi TV work on their “Project Kuleana” music video at UH Mānoa’s Center for Hawaiian Studies.

“The more we can get people to be supportive of an indigenous worldview that emphasizes balance between other people and the environment, the better off we’ll be,” says ‘Ōiwi TV

Keoni Lee on the impact of normalizing the Native Hawaiian language.

founder

HO‘O HAWAI‘I

HO‘O HAWAI‘I

Like the sound of the pū at morning piko, ‘Ōiwi serves as a vehicle to amplify native breath and sound a call to bring people together. Recognizing that culture and worldview are codified in language, one of ‘Ōiwi TV’s main missions is to normalize ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i by making it heard. Roughly 25 percent of ‘Ōiwi’s programming is in ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i, but creating Hawaiian language content, especially with accompanying English subtitles, is time and cost intensive, and funding is limited. While Maori TV in Aotearoa receives nearly $50 million dollars annually in government funding, state funding is still a dream for ‘Ōiwi, despite the fact that Hawaiian is recognized as an official state language. “I’d like to see us at 51 percent or more Hawaiian language programming one day,” says Lee.

The staff at ‘Ōiwi envisions media as a way to extend the reach of ‘ōlelo beyond educational spaces like Hawaiian immersion schools and the university’s Hawaiian Studies program. While the academic world has achieved incredible success in language revitalization, people are beginning to realize that for ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i to truly thrive, it must be heard and spoken outside of the classroom: in government, at home, in the media, by Hawaiians and non-Hawaiians who live in Hawai‘i. Big Island native and immersion-school graduate Ku‘lei Bezilla works as a producer for ‘Ōiwi TV. “Education is one small sliver of a person’s life,” she says. “If language is limited to education, you’re going to learn it and never use it again, but if we can infuse ‘ōlelo into our media, we take one more step towards revitalizing and normalizing ‘ōlelo.”

Bezilla likens the role of Hawaiian media makers in language revitalization to producers of Hawaiian language newspapers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when Native Hawaiian nationalists produced their own newspapers during a time of intense political upheaval. In the years following the illegal overthrow and occupation of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the papers served as a fiber that bound together the political struggles of the nearly universally literate lāhui, or nation. As Hawaiian language began to embody the political power and struggles of Hawaiian nationalists, it became an increasing threat to the colonial project, eventually

prohibited from being spoken as a language of instruction in schools. These newspapers, however, served as repositories of information, and when language revitalization began in earnest after the Hawaiian cultural renaissance in the 1970s, the papers served as critical sources of knowledge for Hawaiian scholars across the islands. With 6.1 percent of Hawai‘i’s population speaking Hawaiian at home as of 2008, ‘Ōiwi TV is continuing the work of the revitalization movement on a new front. “We’re just perpetuating what our ancestors have been doing for so many generations—leveraging the media of our time,” says Bezilla. “We take this technology and ho‘o Hawai‘i it, or make it Hawaiian.”

Like their predecessors who painstakingly crafted stories letter by letter on newspaper presses, the folks at ‘Ōiwi are working to ho‘o Hawai‘i a foreign technology so that Hawaiian language and worldview can reach a wider audience of both native and non-indigenous people in Hawai‘i. “How you are related to the world and how you verbalize that relationship teaches you so much about your place in it,” says Lee. ‘Ōiwi’s commitment to ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i thus goes beyond numerical victories that show impressive increases in the number of Hawaiian language speakers. He adds, “Our society is broken right now, and the more we can get people—Hawaiian or non-Hawaiian—to speak the language and be supportive of an indigenous world view that emphasizes balance between other people and the environment, the better off we’ll be.”

NAVIGATING NEW WATERS

‘Ōiwi TV is not alone in its conviction that Hawaiian knowledge and values have something to teach the world. In 2013, when the Polynesian Voyaging Society launched Hōkūle‘a’s Worldwide Voyage to spread the message of mālama honua, or “to care for our Earth,” across the globe, ‘Ōiwi TV was chosen to document the journey, streaming videos via satellite from the very beginning of the journey through its final moments in 2017. “This was an opportunity to take what we do at ‘Ōiwi TV and put it on the mothership,” says Lee. And he means it literally. ‘Ōiwi traces its genealogy to the Hōkūle‘a in more ways than one. Co-founder Nā‘ālehu Anthony is

a certified captain for the voyaging society, and directed Papa Mau: The Wayfinder, a 2012 feature-length documentary about the legendary sailing master Mau Piailug. Hōkūle‘a’s first voyage in 1976 began a movement to revitalize and respect indigenous knowledge. “Hōkūle‘a raised the consciousness of Pacific Islanders,” says Lee. “Now we can speak truth to power and bring that message to the rest of the world.”

On the Hōkūle‘a and her companion wa‘a (canoe), Hikianalia, ancient and modern technologies carry these truths across oceans and airwaves. Cameras and computers have proven less resilient than the well-trained crew, less able to withstand the constant salt spray and sun. “It’s hard work, but it affords us this incredible opportunity to be a part of something so important,” says Justyn Ah Chong, a director of photography for ‘Ōiwi, who helped document the Samoa to Aotearoa leg of the voyage. “What other production company could bring cultural knowledge, professional skills, and be on the wa‘a the whole time?”

The marriage of ancestral oceanic knowledge and cutting-edge communications technology onboard the sailing vessels shatter outdated conceptions of indigenous cultures as static “museum” cultures. Reflecting on his own changing perspective, Ah Chong says, “When I was younger, I kind of fell for the myth that the Hawaiian culture and language were dying. Working for ‘Ōiwi, I see people restoring ahupua‘a, working in the lo‘i, speaking the language, sailing around the world, and I know that it’s thriving.” Hōkūle‘a’s worldwide voyage—and ‘Ōiwi’s role in it—dares us to critique the failures of modernity and its relationship to the earth and to imagine the possibility of another way of living on this planet. “The values intrinsic in being island people, in terms of living together as a community with limited resources … that perspective is something that the whole world could learn from,” says Ah Chong.

It is hard to say with any kind of certainty that the world is ready to listen to the Hōkūle‘a’s message of mālama honua, or that ‘Ōiwi TV will succeed in its efforts to normalize the Hawaiian language and worldview here at home. But on any given morning in Maikiki, the sound of the pū calling from an inconspicuous house on Ke‘eaumoku Street is a sound of hope.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

IT

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

THE SHOW MUST

GO ON

OVER THREE DECADES, THE HAWAII INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL HAS BECOME THE STATE’S LARGEST ARTS EVENT, BRINGING WORLD-CLASS CINEMA—AND A BIT OF GLAMOUR—TO THE ISLES.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | PORTRAIT IMAGES BY AARON YOSHINO

Myrna and Eddie Kamae giving the introduction of one of their documentaries at HIFF in 1988.

Myrna and Eddie Kamae giving the introduction of one of their documentaries at HIFF in 1988.

Together in the dark, watching a movie, remains one of our culture’s favorite ways to receive a story. For the last 34 years, the Hawaii International Film Festival, HIFF for short, has brought international storytellers to the islands and delivered a generation’s worth of narrative to the world. Despite the advent of film at our fingertips, attendance at the festival has not wavered.

There are as many approaches to running a film festival as there are film festivals. At least a half-dozen exist in Hawai‘i alone: the Waimea Ocean Film Festival, the Honolulu Rainbow Film Festival, the Maui Film Festival, the future Lanai Documentary Film Festival, to name a few. Internationally, there are thousands, some consisting of a weekend of obscure art house flicks for a few loyal attendees, others lasting weeks. HIFF, at 15 days (eleven days on O‘ahu and four on Big Island and Kaua‘i), is expansive in its breadth. Its organizers are dedicated to the mission of bringing the films of Hawai‘i, Asia, and Europe to the masses. It is among the oldest and most respected of its kind in the world, having made Honolulu one of the preeminent places to show film, alongside Berlin, Cannes, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Toronto, and Sundance.

Despite being renowned for selection and programming, with a catalog of films that now includes 178 unique showings, some of the films at HIFF are divisive. But even after viewing cinema bordering on smut or with a halfbrained narrative, audience members rarely feel ripped off. Part of the excitement of a film festival is its capacity to surprise. We purchase tickets knowing the crapshoot; knowing that on occasion, we might be transported to an alternate universe, a different time and place, another’s mind.

Amidst a labyrinth of mostly unoccupied commercial spaces between a Costco parking lot and the state’s largest movie multiplex is HIFF’s nerve center. It is here that the diverse team busily prepares for the annual event. Formerly an actual pineapple cannery, today, the area is composed of Dole Cannery, home to shops and chain fast-food joints, and the Regal Dole Cannery Stadium multiplex, where the majority

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

***

of HIFF’s films are shown.

I’m shown to the office of the festival’s director, Robert Lambeth, whose appearance belies his life as a man of vocational extremes. Anyone who can transition from the commune culture of Hawai‘i Island, where he managed the restoration of old theaters, to the highstrung money talk of London’s finance district, then land in Honolulu to run the state’s largest annual arts event, is a person who’s had more ambitious conversations than anyone outside politics. “You’re catching us in crunch time,” Lambeth says, as he and his predecessor and mentor Chuck Boller take a break to talk festival history. “I met Chuck years ago through theater restoration and worked with him for years prior to coming back. Part of the deal I struck when I came on board was that we need to get back to the neighbor islands,” Lambeth says. “And we’re doing our best. We don’t get nearly as much [financial support] as we once did from the counties, but we’re making it work. We’ve led the way in creating a system of independent theaters that would show art house films,” he says proudly.

Chuck Boller has remained integral to the festival as its director emeritus. Something about Boller’s tailored clothes, perfect diction, and bearded appearance give him the air of a man who runs a chocolate factory, which is not far off: To bring the magic of cinema to the masses, HIFF employs dozens of movie lovers who find themselves in more stable roles of administration. Like many festivals, HIFF is staffed in large part by “festival gypsies” (Boller’s term), the specialists who act as film shippers and programmers. “Nobody’s done more for Hawai‘i-Chinese relations than Chuck,” Lambeth tells me. He may be right. Boller is the sole foreign advisor for the Beijing Film Festival. In October, for the fourth annual China Night, HIFF flew in superstar actor Huang Xiaoming (who was in Los Angeles filming the latest John Woo film The Crossing) for a high-

end fundraiser. The event funded the scholarships of eight Hawai‘i-based film students to visit Shanghai and two select scholarships for students to participate in the American Pavilion of the 2015 Cannes Film Festival.

In addition to student development, HIFF is introducing entirely new narratives to the local community through the New Frontiers program, which focuses on Islamic communities. For the filmmakers invited to the festival in 2014, the diaspora of Islamic communities is less compelling than the narratives of individuals surviving and finding love in the modern world. This year’s New Frontiers program featured Hasan Elahi, a multidisciplinary artist whose work on the surveillance state has made him internationally famous, and Desiree Akhavan, who uses IranianAmerican identity only as a starting point in her feature Appropriate Behavior, a romantic comedy making an argument against coming out as bisexual to immigrant parents. “I’m always surprised when I meet someone who hasn’t heard of HIFF,” says Boller. Considering the expanse of films, discussions, programs, and community development, Boller’s incredulity is no surprise.

***

In the early 1980s, Hollywood production and financing shifted toward juvenile mass appeal. In the wake of the gritty realism of the 1970s, multiplexes were built across America, and studios reconfigured to capitalize on the staggering commercial success of George Lucas’ Star Wars. At the same time, the art of filmmaking was being taught in universities around the world. Women, indigenous people, and American minorities were picking up the craft. The idea of a documentary as a nonfiction narrative became realized. Movies had proven to be capable of highminded abstraction or pulp narrative; as transformative forms of fiction or

forgettable camp trash. Film had conquered the world.

Art house cinema and festivals were the reaction to the commercialism and uniformity that were becoming normative. It was in this climate that HIFF was created in 1981, starting off as an academic affair with ambition. The back pages of the inaugural catalog were even left blank for notes. Jeanette Paulson Hereniko, the festival’s founding director, recalls the early days when HIFF was held at the East-West Center: “When we started, every movie was free, and we promoted discussion of content over production. The East-West Center’s mission is to promote cultural understanding—we just added the ‘through film’ part. And over the years I saw such transformative things.” In 1985, she invited Zhang Yimou, famed filmmaker and director of the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening and closing ceremonies, on his first trip out of China. In 1986, Hereniko oversaw the co-screening of American and Vietnamese films of war.

“We brought Roger [Ebert] to Maui in 1985,” she remembers. “It was his first time meeting Asian film critics, and he took his first trip to Japan as a result of that.” Ebert also met Donald Richie, the esteemed Western critic and scholar of Japanese film and culture in the late 20th century. That initial trip was transformative for Ebert, who returned annually. It is well known that Ebert was more than a critic. Embedded in his weekly discussions of film were countless tricks for creative writers, the wonder of which inspired those in all fields of English language: art criticism, history, critical theory, creative writing, law. It was in Hawai‘i that Ebert was introduced to a decades-long appreciation of Asian and Asian-American film. It was here that he also fell in love with his wife, Chaz, Lambeth says. In 2011, cancer and surgery robbed Ebert of the ability to speak. What happened next was followed religiously by those devoted to his work. His blog, which was previously the site for decades’ worth

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Top: The staff that makes HIFF happen shown in the film festival’s headquarters at Dole Cannery. Bottom: Event photos from HIFF’s archives, which include appearances by Roger Ebert, John Ritter, Toni Collette, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, and Quentin Tarantino.

Top: The staff that makes HIFF happen shown in the film festival’s headquarters at Dole Cannery. Bottom: Event photos from HIFF’s archives, which include appearances by Roger Ebert, John Ritter, Toni Collette, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, and Quentin Tarantino.

“Nobody’s done more for Hawai‘i-Chinese relations than Chuck,” Robert Lambeth says of director emeritus Chuck Boller.

of criticisms, evolved into a discussion far beyond movies. He used film to relate the personal to the political in ways that are nearly impossible to duplicate. He returned to Hawai‘i one last time in 2012 and presented a discussion of film through text repeated by a computerized voice and his wife. “I think theirs is a beautiful love story,” Boller says. “It’s still very raw for her. We’re very proud to carry on this legacy. In 2015, we’re launching the Ebert Young Critics Foundation,” Lambeth adds proudly.

From Hereniko’s to Lambeth’s tenure, the technological changes to moviewatching have been immense. HIFF’s 2003 catalog has a full-page ad from the now-failed video rental store that says, “Make it a Blockbuster night.” The keiki of contemporary Hawai‘i will never know the experience of perusing for, renting, and ultimately paying late fees to watch a movie. Kids aren’t missing much from the last days of celluloid, either. Once decried, digital projectors have become both normative in the industry and built to approximate the same dreamy brightness of light projected through film. Boller shows me how one works. “Most people have no idea this is what a movie looks like,” he says, showing me a hard drive in a yellow, padded plastic hazmat case. “A few years ago, we got a film from India in one of these that was filled with water,” he says. “Other times, we’ve had the wrong film in the case, or it wasn’t digitally set for the projector and we can’t show it. We figure something out.” Nary a hair on his face is misplaced at the thought of disaster. For film festival organizers, it’s all in a night’s work.

Considering its focus on underrepresented communities, HIFF has shown many works of ethnographic proselytism with scores to settle. It was in the last decade that the festival became the true showcase for Hawai‘i’s diversity, whether through unrehearsed local voices or non-American blockbusters. A favorite short of 2004 was Amasian: The Amazing Asian, written and directed by Gerard Elmore, the story of a local boy who ate radioactive rice, enabling him to graduate early from high school and fly. The superhero defended the planet from an asteroid by defeating his nemesis Wai‘anae Man, whose powers were derived from magical slippers. That same year, HIFF’s most popular showings were

from Korea, a nation whose filmmakers have proven their superiority in all things dramatic and violent. If there was an award for making viewers recoil in terror and awe, it would have gone to Old Boy by director Park Chan-wook, the now-classic Shakespearean thriller-horror-gangster movie that inspired Spike Lee to do a nearly shot-by-shot remake a decade later. In 2006, HIFF played the horror-social commentary The Host to a packed audience made up primarily of the vibrant Korean community in urban Honolulu that frequents the halfdozen video stores off Ke‘eaumoku Street.

For films whose subject matter is Hawai‘i, HIFF has been the site of controversy. In 2009, the biopic Princess Kaiulani was met by protestors who decried its working title Barbarian Princess, as well as its title role being portrayed by a non-Hawaiian. Leading actress Q’orianka Kilcher subsequently gave a teary press conference with community leaders and now leads a life of activism. Princess Kaiulani tied for “Best Feature,” as voted by HIFF audience members. The 2012 feature The Land of Eb by Andrew Williamson stars exceedingly talented Jonithen Jackson, who plays a man not far from himself: Jacob, a Marshallese head of household with a sense of humor and penchant for filmmaking, living in an immigrant community of farm workers on Hawai‘i Island’s fertile slopes. The Land of Eb is reminiscent of foreign movies that follow the indignities of ostracized communities, in this case highlighting the immigrant experience mere miles away from the resorts and milliondollar homes being developed in Kona. Lambeth reflects: “Film tells us about our own community.”

HIFF has brought Hawai‘i out of the cinematic provinces. And for emerging local filmmakers, it is an institution: The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Academy for Creative Media (ACM), which fosters many young filmmakers who eventually end up showing films at HIFF, began in 2004 after years of planning and outlining under the guidance and diligence of its founding director, locally born Hollywood producer and director Chris Lee. What began with just a few select classes grew course by course. Since 2008, ACM has offered a creative media major at the university, with tenured professors, hundreds of graduates,

and three tracts in digital narrative, gaming animation, and critical studies.