THE APOCALYPSE ISSUE

KLEIN’S RISING TIDE

LDS PREPPERS

ZOMBIE NATION

REAL LIFE ON FAKE MARS

18

WHAT THE FLUX?!

Could This Be the End?

Make sense of the apocalypse when it hits. 20

LOCAL MOCO

Futurist James Dator

FLUX FILES

24

BOOKS: Klein’s Rising Tide 26

THE END

FOOD: LDS Preppers

BOOM TO BUST

Annie Koh tells a true tale of billion-dollar ghost towns and thriving bankrupt cities. 34

NET PROPHET

Mary Babcock’s textile art forewarns the fallout of a consumerist culture.

38

ZOMBIE NATION

As mindlessness continues to spread like a virus, Lisa Yamada looks at how one community college program is attempting to inoculate this disease of the brain. 44

YOU DON’T KNOW SHIT

Where do our feces go, and how should we do the deed if the world as we know it ends? Anna Harmon traces doodoo disposal in the islands from ancient times to apocalyptic futures.

If our poop seeps into our water, touches our food, or piles up and festers, it can kill us. But it can also give back to a natural cycle with rich nutrients that are food for microorganisms and fertilizer for plants.

WHAT THE FLUX?!

Quiz: What Apocalypse Survivor Are You? As civilization crumbles, how will you fare?

FLUX FILES

FOOD:

Frankie and the Fruit Factory

ARTS:

Kapa Artist Roen Hufford

THE BEGINNING

Artists of Hawai‘i 2015

REAL LIFE ON FAKE MARS

Mars suddenly seems within reach, with NASA planning to launch its first mission to the red planet in the 2030s. Anna Harmon talks to the six-person HI-SEAS crew playing interstellar house on Mauna Loa. 60

THE MIRACLE OF FISH

With ancient fishponds neglected for centuries, overrun by development, and burdened by a labyrinth of laws, Sonny Ganaden explores how these humble areas have become the geographic and metaphoric site of cultural revolution.

INTO THE WOODS

Hawai‘i’s mountainous regions are filled with a bounty of edible plants—you just have to know what to look for.

RISE OF THE MACHINES

Many of the world’s foremost minds, including the likes of Elon Musk, Bill Gates, and Stephen Hawking, warn of the rise of a sentient machine. Carmichael Doan ponders what the future of the human race will look like as humanity becomes increasingly dependent on its machines, and as advances in robotics grow with increasing swiftness.

WAYS TO SURVIVE THE DIGITAL APOCALYPSE (NOW)

Who says the apocalypse has to be bloody? Emojis and malware; #nofilter selfies and NSA surveillance; Twitter feeds and

cyber wars—the digital apocalypse is a friendly face with very real, very unfriendly consequences that are affecting how we interact with our surroundings. Zoe Vorsino explains how to deal with it all.

POST-APOCALYPTIC PRODUCT ROUNDUP

Whether you’re figuring out how to survive in a post-apocalyptic world or you’re trying to make the current one you live in a little greener, these products from Bokashi Bucket, KH Studio, and Lono Transpo can be helpful for achieving both.

THE MEN INNOVATING WASTE MANAGEMENT

With funding provided by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, Andrew Whitesell and Christopher Chock of Beaumont Design, a company based out of the Manoa Innovation Center, are helping to solve the problem of pumping poop in developing countries. Their sleek design is called the fecal sludge Omni-Ingestor.

FIND

ON THE COVER:

Shown on the cover, Lucie Poulet and Annie Caraccio record data for the Hawai‘i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation research program. Since October 2014, a crew of six has been simulating life on Mars on Mauna Loa’s eastern slope for Mission III, which is focused on crew cohesion. NASA is preparing to launch its first mission to the red planet in the 2030s. Image by Ross Lockwood, courtesy of the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

EDITOR’S LETTER

| APOCALYPSE |In the months leading up to the year 2000, humanity braced itself for Y2K, the computer glitch that would bring a world increasingly reliant on technology to its knees. It was thought that since computers process only the last two digits of a year, systems would revert back to the year 1900. Networks would fail, economies would collapse, and mass chaos would ensue.

It was easy to get caught up in the frenzy that followed. Better safe than sorry, right? My father dedicated an entire room in our house to the cause. I’m sure there were generators and batteries and other disaster-kit essentials, but the food is what I remember most. Cans of chili and soup, bags upon bags of dried beans and rice, dozens of boxes filled with dehydrated potatoes, vegetables, and meat—all stacked neatly on industrial wire racks, the kind you can buy at Costco. He even made kits filled with batteries and food and disbursed them to many of our friends and family.

As we all know, the end never came, and most people went about their usual New Year traditions, popping their leftover supply of fireworks, drinking ozoni soup, or watching football.

Doomsday predictions have been made since the beginning of humanity. They date as far back as 634 BCE, when the Romans feared their 120-yearold city would be destroyed. Hippolytus of Rome, Sextus Julius Africanus, and Irenaeus all anticipated Jesus’ return and the world’s end in 500 CE. Fastforward to 1284, the date Pope Innocent III predicted the world’s end, which he calculated by adding 666 years to the date he assumed Islam was founded. The Millerites calculated it would happen sometime between 1843 and 1844; Halley’s comet provoked doomsday fears in 1910; David Koresh and his Branch Davidians anticipated (and saw) their ends in 1993. In 1997, Marshall Applewhite convinced 39 people to ingest phenobarbital to leave their bodily containers and hop aboard the alien spacecraft that trailed the Hale-Bopp comet; 2012 stoked apocalyptic fears (and end of the world parties) as a result of the Mayan calendar.

Why does the idea of apocalypse so often consume us? Perhaps it’s not so much that the collective end of the world is so frightening, but rather, our own end that terrifies us so. Man’s nature is to control, but since the future cannot be controlled, we can only do our best to prepare for it.

If this issue has taught us anything about apocalypse, it’s that when the world ends, Hawai‘i will be ready. Bestowed with a bounty of natural resources, Hawai‘i stands to be a model in preparing for a more sustainable future. As such, just as the Hōkūle‘a travels in a worldwide voyage to mālama honua, or care for our Earth, so too must we “engage all of Island Earth,” as encouraged on Hōkūle‘a’s website, “practicing how to live sustainably, while sharing, learning, creating global relationships, and discovering the wonders of this precious place we call home.” Yes, I know, it’s a heavy burden to bear, living in this island paradise, but as the world continues to look toward the heavens, gazing out into the stars and wondering about Earth’s end, we do our best to look down, and prepare for the beginning.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor lisa@nellamediagroup.com

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

ARTS & CULTURE

DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Mark Ghee Lord Galacgac

Jonas Maon

MASTHEAD | APOCALYPSE |

CONTRIBUTORS

James Charisma

Stuart Coleman

Le‘a Gleason

Kelli Gratz

Annie Koh

Lindsea Wilbur

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER

mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns

MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Carrie Shuler

MARKETING & CREATIVE COORDINATOR

SPECIAL THANKS TO: Hawai‘i Research Center for Futures Studies

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Matt Honda CREATIVE & INNOVATION DIRECTOR

Michelle Ganeku DESIGNER

INTERN

Rachel Halemanu

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2009-2015 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

CONTRIBUTORS | APOCALYPSE |

STUART COLEMAN

Three things I’d want to have during an apocalypse: My surfboard, my laptop plus a solar-powered generator, and a boatload of my friends heading for a remote island.

Stuart Holmes Coleman is a writer, speaker, and environmental activist. Of interviewing author Naomi Klein and her husband Avi Lewis on page 24, the Surfrider Foundation Hawai‘i manager says, “They are dealing with the heaviest environmental challenges to our planet, yet they remain lighthearted and down to earth. It was challenging to convey the seriousness of these problems without pushing the story over the edge with a doomsday outlook.” Coleman is the author of Eddie Would Go, Fierce Heart and a recipient of the Elliot Cades Award for Literature. He has received several writing fellowships and served as writer-in-residence at St. Albans School in Washington, D.C. Coleman has taught writing, literature, and leadership at Punahou and ‘Iolani schools, the University of Hawai‘i, and the East-West Center.

LE‘A GLEASON

Three things I’d want to have during an apocalypse: My dog, a flashlight, and an extra pair of slippers.

Le‘a Gleason is a Big Island native who found journalism while attending the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. About writing the story on humble Big Island kapa maker Roen Hufford on page 72, Gleason says, “There was a moment when Roen said, ‘I’m really not that talented.’ I like to think that maybe, if I wrote the story just right, she’ll read it and realize how precious her gifts are and what a service she is doing for others by sharing her craft.” Gleason is passionate about nonfiction storytelling, and also enjoys spending time with her dog, performing at open mic nights and in community theater shows, dancing, and teaching yoga.

ANNA HARMON

ANNA HARMON

Three things I’d want to have during an apocalypse: My boyfriend, a sharp knife, and cabbage seeds.

Anna Harmon is the managing editor for FLUX Hawaii and has been contributing to Nella Media Group publications since 2010. The apocalypse theme of this issue is largely the result of her urging. “It’s an irresistible topic,” she says. “Apocalypse inspires innovation but also paints horrifying scenarios. I’ve spent years reading dystopian novels and tallying up the things bringing us closer to the end. For this issue, I wanted to learn about conditions building up to such a scenario both locally and globally, and if it were to pass, what will get us through in a post-doomsday Hawai‘i.” She learned that you can ferment things with your spit (page 86), that hiding in lava tubes can protect you from radiation (page 54), and what to do about doodoo (page 44). “All in all, this issue gave me a huge appreciation for what I have today.”

I recently read the article “Do You See Me,” and I was fascinated by how our race defines us here in Hawai‘i. It inspired me to write on how being a child of divorce has defined me. Growing up with divorced parents, there have always been two completely different sides to my personality. I know lots of other teens and kids with divorced parents, all with varying opinions on the matter. Some see it as a detriment and some see it as a blessing. It’s not something I’m ashamed of, but rather simply a trait of mine as normal as where I live or what school I go to. It is rough having divorced parents—two sides constantly barking in your ear with polar-opposite advice is confusing. There are great benefits of having divorced parents, though. You get double the birthday and Christmas presents; since they rarely agree on things, there is no chance they share a gift. If one parent says no, there is a chance the other will say yes, and you gain a stepfamily, which means more people to love and have fun with. There is no doubt that I often wonder what my life would be like if my parents weren’t divorced. However, being a child of divorced parents defines me, for better or worse.

Isaiah Palmero

Congratulations to you for your wonderful article on mixed race families in Hawai‘i. I’m a Swiss/French/English male married to a Hawai‘i-born Chinese female. We have a daughter, 31, who lives in Washington, D. C. In 1998, struck by the beauty of Hawai‘i’s hapa children, I published a book of photos of my daughter, her friends, and many others. Rainbow Kids was unique in that it identified the ethnicity of each child. Frank DeLima kindly contributed an introduction. While not a bestseller, it sold fairly well here and on the mainland. And I had a lot of fun presenting it to President Obama (through his sister), Tiger Woods, and Britney Spears (I received a “thank you”). It has also been a lot of fun watching the kids grow into adulthood. Congratulations, again! We are looking forward to many more issues of Flux Hawaii.

Richard Fassler

@kianamosley: “when the mailman delivers this kind of beauty... @fluxhawaii you’ve outdone yourselves... Again.”

THE END

COULD THIS BE THE END?

The world as you know it is in disarray. But could it be the apocalypse? When doomsday hits (or maybe it already has!), use this flowchart to make sense of what scenario you are experiencing. Good luck!

Made in collaboration with Hawai‘i Research Center for Future Studies

Design by Michelle Ganeku

ARE THEY IN MOBS?

DOES THE ILLNESS SEEM CONTAGIOUS?

DO MOST SEEM SICK?

DO THEY INTERACT WITH TECH MORE THAN HUMANS?

QUARANTINE YOURSELF, AND FIND A BOAT.

PANDEMIC

MOST LIKELY CAUSES: HUMAN EXPERIMENTATION OR ASSHOLE EXPLORERS.

RED HILL OR OTHER LEAK. DRINK CACHED OR BOTTLED WATER.

IS IT FROM THE DRINKING WATER? BONUS!

CAN YOU SEE ANY PEOPLE AROUND?

ARE THEY FLEEING?

IS IT FROM DRONES OR ROBOTS?

STOCK UP ON SUPPLIES AND MAKE THINGS LAST.

GOVERNMENT COLLAPSE

LOOKS LIKE THE U.S. DOLLAR COULDN’T HOLD UP TO MASS DISCONTENT AFTER ALL.

NO ELECTRICITY OR MASS CHAOS? AN ELECTROMAGNETIC PULSE JUST WIPED OUT ALL ELECTRONICS.

START

DO YOU SEE ANY ANIMALS?

DO YOU HEAR A STEADY HUM?

IS IT BECAUSE OF A CREATURE YOU’VE NEVER SEEN BEFORE?

GO ANALOG, OR BEFRIEND A ROBOT.

TECHNOLOGICAL TAKEOVER

OR HAS THIS ALREADY HAPPENED?

OR A TECHNOLOGICAL OVERTHROW.

COULD HAVE BEEN A MASSIVE SOLAR FLARE.

HAS THE WEATHER OR TEMPERATURE BEEN CRAZY?

DO YOU HAVE ELECTRICITY?

ARE CORN AND INVASIVE PLANTS THE ONLY VEGETATION YOU SEE?

IS IT SURPRISINGLY COLD AND DARK?

FROM A HIGH VANTAGE POINT, DOES IT LOOK LIKE BUILDINGS ALONG THE COAST ARE GONE?

IS IT BECAUSE IT’S NIGHTTIME?

DUDE. EVERYTHING IS FINE.

STOCK UP ON SUPPLIES AND FIND SHELTER.

ENVIRONMENTAL COLLAPSE

IT MAY HAVE BEEN MOTHER NATURE, OR IT MAY HAVE BEEN TIME TO DIVEST IN FOSSIL FUELS.

WHAT IS HAPPENING? PACK YOUR BAGS FOR MARS.

BLACK SWAN

THIS SCENARIO INCLUDES: ALIEN INVASION AND VOLCANIC SUPER-ERUPTION.

According to the recently retired James Dator, who served as the director of the Hawai‘i Research Center for Futures Studies since its founding in 1971, we are living in a period when one way of life is coming to a crashing halt and a chance for new beginnings is arising.

THE MAN OF FUTURES

FOR

JAMES DATOR, ONE OF THE FOUNDING FORCES BEHIND FUTURES STUDIES, APOCALYPSE IS BUT A NEW BEGINNING.

TEXT BY LINDSEA WILBUR IMAGES BY JONAS MAONTake a deep breath and pause for a moment: Think about a future, any future. I hope, dear space-time traveler, it does not weigh heavily upon you. Perhaps you are filled with trepidation at the prospect of an utterly unknown yet apocalyptic forecast. On the other hand, you could feel energized, focused, and present enough to face whatever may come your way.

What you just experienced when you thought about a future, and why it sprang to mind, is the passion and profession of James Dator, who has made it his business and life’s work to study and explore how humans think about the future. “For most people, I believe, the apocalypse is much more frightening and terrible than I imagine,” Dator says. “I do think we are living in a period where one way of life is coming to a crashing halt and so a chance for new beginnings is arising.”

Throughout his life, Dator has contributed greatly to the theory and practice of a field called “futures studies.” That extra “s” at the end of futures signifies a belief in alternative futures—meaning that there is not one, but rather many possibilities that we can’t fully imagine. The future, and the apocalypse, were things Dator pondered even as a child, when Anglican theology, as well as the grand theories of history from the likes of St. Augustine, Joachim of Flora, St. Thomas, Oswald Spengler, Karl Marx, and Arnold Toynbee, held his attention. “They all tried to explain the purpose of life, which fascinated me,” he says.

Since arriving to Hawai‘i during the summer of love in 1969, with the purpose of teaching political science at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, Dator has been a sort of intellectual godfather for generations of young futurists, serving as director at the Hawai‘i Research Center for Futures Studies (HRCFS) since 1971. Before that, he taught on the subject in the College of Law and Politics at Rikkyo University in Tokyo, as well as introduced what is often considered the first undergraduate course on the future while at Virginia Tech.

He has cultivated a formidable global network that ranges from the Pentagon to off-grid anarchist communes. But nowadays, the octogenarian prefers to keep to his peaceful condo overlooking Waikīkī, imagining futures both ridiculous and reasoned, the most pressing of which include pondering the predicaments of energy, environment, economy, and governance.

“The apocalypse is a sudden end to the world as we know it, either the ushering in of a new world or as providing an opportunity to create a new world,” he says.

Earth has already endured many apocalypses in the past billions of years.

Dator points out that the only difference is the unprecedented influence that humans have on the planet. Scientists and theorists describe this as the Anthropocene Era, the

time period when humanity, as a natural, geological force, has made a significant impact on the Earth.

So what of the end of the world as we know it? “For the last 200 years, people and organizations knew exactly what the future was supposed to be—what the future of life was—and that was continued economic growth, sometimes called progress, sometimes called development,” Dator says. “But that world, that image, is now highly problematic. I think the driving forces of it have come to an end, and … it’s absolutely essential that people, individually and collectively, scan the alternative futures that are before us and develop a new, preferred set of futures for themselves and their communities.”

Hawai‘i

is on the front lines of climate change, according to author and activist Naomi Klein, who was invited to Hawai‘i as a visiting scholar at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.FLUX FILES | BOOKS |

KLEIN’S RISING TIDE

AUTHOR-ACTIVIST

NAOMI KLEIN ON CAPITALISM, CLIMATE CHANGE, AND THE PROMISE OF HAWAI‘I.

TEXT BY STUART COLEMANILLUSTRATION

BY ARA FEDUCIA“Climate change changes everything,” author-activist Naomi Klein told a packed house at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Campus Center in February. “We’re in a suicidal phase of the fossil fuel economy and the most extreme forms of extraction.”

Like an apocalyptic vision, Klein described the evils of current energy practices: fossil fuel companies cutting off mountain tops for coal, spilling millions of gallons of crude oil into the ocean through deep-sea drilling, and contaminating drinking water through hydraulic fracking.

Only in her mid-40s, the Canadian writer sounded more like an Old Testament prophet as she railed against the corruption and greed of the powerful oil companies— huge corporations that she strongly believes are destroying the planet. Toward the end of her sobering talk, Klein rallied the huge crowd, saying how people have the power to stop these extraction companies and their growing control over government: “Now we need to fight, and we can’t afford to lose.”

Invited to Hawai‘i as a visiting scholar (she served as the Dai Ho Chun

Distinguished Chair in the UH College of Arts and Sciences), Klein’s visit couldn’t have been more timely. Just weeks before, the UH Board of Regents had voted to support a plan to divest from fossil fuels, a measure many universities around the country are beginning to take.

Along with teaching a seminar at the university, Klein and her husband, documentary filmmaker Avi Lewis, gave a series of provocative talks around Honolulu discussing climate change and her new book, This Changes Everything: Climate vs. Capitalism. In it, Klein writes about the rise of what she calls “Blockadia,” wherein ordinary citizens step in to fight the failings of their government, and, in particular, fossil fuel extraction by the world’s largest and most profitable oil, gas, and coal companies. “The rise of Blockadia is, in many ways, simply the flipside of the carbon boom,” she writes, further describing it as a popular uprising against the “new and amplified risks associated with our era of extreme energy (tar sands, fracking for both oil and gas, deepwater drilling, mountaintop removal coal mining).”

Putting herself on the front lines of the climate change movement, Klein has become a leader in the fight against the Keystone XL Pipeline. The controversial pipeline would carry Canadian tar sands oil (what Al Gore called “the dirtiest fuel on the planet” during a 2014 appearance at UH) across the middle of the country, exposing pristine prairies, forests, and waterways to devastating oil spills. A Canadian with American roots, Klein believes both countries will suffer disastrous environmental consequences if the Keystone Pipeline is built. She has joined many demonstrations around the world, including a 2011 protest outside of the White House in Washington, D.C. that resulted in her arrest. Despite a hard-fought and seemingly uphill battle, Klein believes the combined efforts of the Blockadia movement and her fellow “climate warriors” are finally paying off.

“Obama vetoed the Keystone Pipeline today,” Klein tells me when we meet on a warm evening in Waikīkī, waves lapping

at the shore just steps from where we are sitting. “The only reason this happened is because people got together to stop it and made this happen.”

Klein seems to have an almost prophetic sense of timing. Her first book, No Logo, came out right before the World Trade Organization (WTO) riots in Seattle, and it soon became a bible for the anti-globalization movement. Her second book, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism, was published in 2008 during the financial crisis. In the midst of the chaos, Klein explained how emergency bailouts were used to systematically override democracy and to enrich those corporate and banking elites responsible for the collapse.

Klein’s new book, This Changes Everything, was published in September, just weeks before the largest climate march in history. More than 400,000 people took to the streets of New York, demanding action on climate change. Similar protests took place around the world; in Hawai‘i, more than 200 people marched through Waikīkī with signs declaring, “The Seas Are Rising and So Are We!”

Hawai‘i, Klein says, has a high degree of ecological consciousness, placing it on the front lines of climate change, especially in terms of clean, renewable energy. “But I don’t have to tell you that the profit motive is getting in the way of what the people want in Hawai‘i,” says Klein, referring to HECO’s glacial pace in embracing renewable energy and its possible takeover by NextEra, a resource energy company seeking to ship natural gas to the islands.

“It’s insane and massively dangerous, and it’s also expensive,” she says.

As a mother and activist, Klein believes people are capable of profound change. But as an author and political analyst, she knows all too well how powerful elites will not give up their power unless the people demand it.

“It’s a historical moment for Hawai‘i,” Klein says. Will Hawai‘i heed Klein’s prophetic forecasts, stepping up to lead the clean energy revolution, or will it sit back and suffer the consequences of climate change and sea level rise? Either way, it’s our choice.

LDS PREPPERS

ACROSS THE ISLANDS AND THE GLOBE, MEMBERS OF THE MORMON CHURCH DO THEIR BEST TO PREPARE FOR THE WORST.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMONIMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

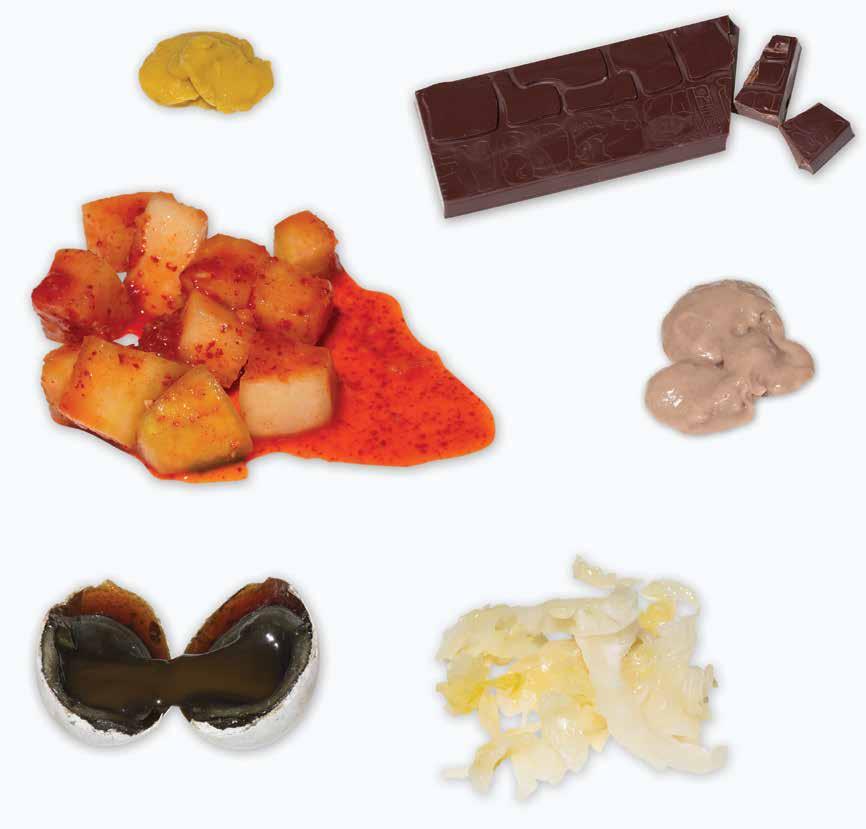

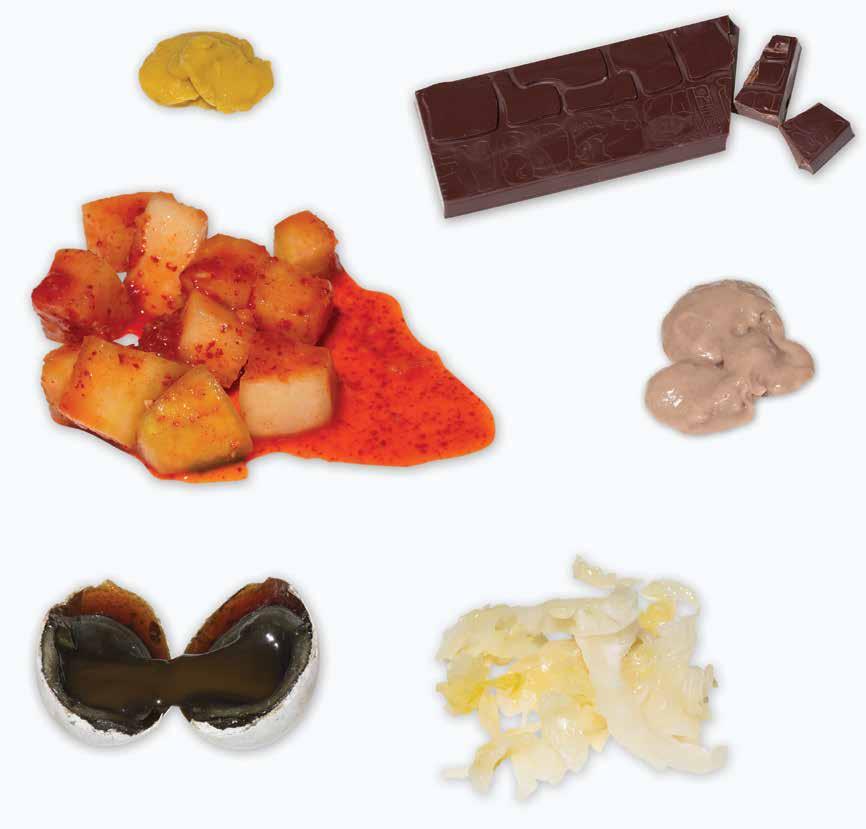

“Sarah, there’s someone here for family planning,” calls out a man sitting behind a counter at the entrance to the LDS Bishop’s Storehouse, a food pantry for members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on O‘ahu who are struggling to make ends meet. Just off Kalihi Avenue, the storehouse is tucked away in a squat building on the far end of a nearly empty parking lot. Sarah Barientos, a petite woman wearing a T-shirt and carrying a clipboard, greets me and leads me through double doors into a quiet, well-lit storage room that seems larger than the building would allow. A table at its center is covered with a grid of order forms for preserved goods, and floor-to-ceiling stacks of canned, dried, and boxed food line the walls. This is the Honolulu Home Storage Center, formerly known as the LDS Cannery, where members of the church and general public can buy Mormon-brand bulk foods at absurdly low prices ($2.75 for 5-1/2 pounds of hard red wheat and $9.75 for a pound of canned apple slices good for 30 years, folks).

Mormon families from Utah to Moloka‘i are encouraged to have a three-month supply of food, water, and money, with a goal of at least a one-year supply. “[The prophets’] revelation that heavenly Father had given them … tells us it’s important for us members to seek out self-reliance,” Barientos explains. “For me personally, [food storage] is just in case something should happen. Like, I use my own experience when I lost my job back in 2010 due to a work-related injury.” Today, she is a full-time volunteer at the center. An enthusiastic and sincere woman, Barientos bubbles over with excitement about getting the word out about the location, which is unknown even to some members on O‘ahu. Plus, Barientos declares, “This is open not only to the members, but also to the public. It’s the cheapest prices. The church actually pays for the shipping costs.”

While some Mormon families do not have a storage because it seems outside their budget or lifestyle, and a lack of landfall disasters has lulled nearly everyone in the islands into a sense of safety and comfort,

At Honolulu Home Storage Center, members of the Mormon church and general public can buy bulk foods at low prices in preparation for a day of reckoning.

they are reminded to prepare by way of an annual fair held at Brigham Young University-Hawai‘i, as well as occasional ward gatherings, when families sort disaster kits, toss out expired items, and make lists of what they need. Barientos maintains social media accounts for Honolulu Home Storage Center, including an Instagram account where she shares recipes featuring items from its rotating three-month supply.

Throughout the years, calls for members to heed warnings from the Book of Revelations—think plagues, wars, and famine in the time before the coming of Christ—rise and fall. Ezra Taft Benson, a portentous prophet (all Mormon presidents, who are believed to have direct contact with God, are considered prophets) who survived the Great Depression and was president of the church from 1985 until he passed away in 1994, was a fiery promoter of self-reliance and home storage.

At a general conference in 1965, he warned: “Should the Lord decide at this time to cleanse the church—and the need for that cleansing seems to be increasing—a famine in this land of one year’s duration could wipe out a large percentage of slothful members, including some ward and stake officers. Yet we cannot say we have not been warned.” In 2002, a letter from the First Presidency (the governing body of and highest ranking quorum in the church) took a decidedly softer approach to the encouragement of home storage: “Members should be prudent and not panic or go to extremes in this effort. Through careful planning, most church members can, over time, establish both a financial reserve and a year’s supply of essentials.”

For members like Barientos, any prophetic doom and gloom is accepted with a pragmatic air and a smile. Sure, pestilence or famine may arise. But more likely, the

economy will dip or a Matson strike will cause others to rush Costco, and there Barientos will be, alongside other prepared members, ready to support the community. “We have aquaponics, we’re trying to do all that,” says Barientos of a garden she maintains with her husband. After she lost her job, she says that she realized the importance of cultivating her own food, something her mother had done when Barientos was growing up. “We grow tilapia. … I think we may have enough now for maybe a six-month supply. And if things did come really bad, apocalyptic, I would be able to help my neighbors and my family, you know?”

The Honolulu Home Storage Center is located at 1120 Kalihi St. Follow them on Instagram @honoluluhomestoragecenter.

BOOM TO BUST

FROM BILLION-DOLLAR GHOST TOWNS TO THRIVING BANKRUPT NEIGHBORHOODS.

TEXT BY ANNIE KOH ILLUSTRATIONS BY MARK GHEE LORD GALACGACIn our visions of post-apocalyptic cities, part of the horror is what happens when economies fail, when direct deposit vanishes and bartering of goods is the only means of exchange.

But the inverse, when wealth pours into a city without restraint, can be just as alarming. Take, for instance, London, a city wracked by over-investment. Money from newly minted Russian gas magnates and Gulf State heirs has set the overheated property market to boiling, while deadening the street life of some of the area’s most historic neighborhoods (not to mention,

hurting the restaurants and shops). Critics bemoan the eerie emptiness of London’s urban core, which is suffering from a distinct lack of people even as apartments are snapped up as investment assets by domestic and foreign buyers. An estimated 22,000 properties in London are uninhabited or “long-term empty.” Swanky districts like Kensington are strikingly dark at night, and London’s One Hyde Park, possibly the most expensive residential building in the world, has primarily absentee owners.

Nightmares of desolate boomtown cities circle the globe. The western city of Ordos is China’s most famous ghost city, built to house more than a million people, yet with only 2 percent of the buildings filled. Throughout the country, dozens of new cities have been built in a frenzy fueled by property speculation and municipal governments’ push for revenue. Though the rows of apartment complexes have found domestic

Honolulu’s collapse of urban life may not come in Great Depression-style financial conflagration, with stockbrokers tumbling down with the Dow Jones. It may instead come humming in on wire transfers, a flood tide of capital that erodes livelihoods with each long-term empty apartment it buys.

investors, many of the apartments remain empty. Even bustling Manhattan is dotted with strangely silent voids, what one real estate appraiser called “the equivalent of bank safe deposit boxes in the sky that buyers can put all their valuables in and rarely visit.”

Maybe no one wants to live in rainy London or Inner Mongolia, but surely this cannot be true for the ocean-front city of Honolulu, consistently ranked high in livability indexes? Alas, remember Kawamoto, the garish billionaire who left million-dollar properties to rot in Kahala? The giant pool of money sloshing around in the global economy has already brought blight to these shores. Imagine our city as an investment portfolio instead of a place to live, where neighborhoods echo only with the footsteps of the property manager coming by to tour the tomb-like bank vault of security alarmed apartments. Honolulu’s collapse of urban life may not come in Great Depression-style financial conflagration, with stockbrokers tumbling down with the Dow Jones. It may instead come humming in on wire transfers, a flood tide of capital that erodes livelihoods with each long-term empty apartment it buys.

On the other hand, what happens when the real estate market tanks, and money marches out of a city? In 2008, images of foreclosed houses dominated the news. People walked away from

underwater mortgages, leaving the homes to scavengers and squirrels. But when investment vanishes and land ceases to have market value, other values can flourish. The most famous contemporary example is Detroit, which declared bankruptcy in 2013 after its economy was decimated by the collapse of the American auto industry. Today, the city is an epicenter of urban agriculture, with some remaining residents turning abandoned lots over to vegetable production.

This model isn’t new. In the 1970s, an era of massive disinvestment in American cities reached its height in New York City after President Gerald Ford refused to bail out the municipality, and the city slashed its operating budget. Landlords began torching their buildings rather than pay for upkeep, resulting in a wave of insurance-claim arson. In the literal and figurative ashes of the South Bronx, of Harlem, of countless residential neighborhoods, individuals and community organizations began planting.

The first community garden in New York City’s Lower East Side was established in 1973 by a group of hippies who started digging without permission in a city-owned lot. By 1995, there were 75 gardens growing in just the 33 blocks from 12th Street and Houston between Avenues A and D.

In Argentina, the economic collapse of 2001 was precipitated by multinational banks “[whisking] $40 billion in cash out

of the country in the dead of night” as Argentine’s currency began to plummet. Widespread layoffs and factory closures resulted in massive unemployment. But at one men’s suit factory, the seamstresses decided that they didn’t need to wait around for an economic revival, and waltzed back in to restart their sewing machines. Their example of a factory takeover inspired hundreds of worker collectives across Argentina, and even in Europe and the United States, where, in the depths of the most recent recession, workers staged sit-ins in factories in Chicago to keep production lines active.

In one dystopian scenario of postpeak Honolulu, the “haves” hoist their shotguns to guard houses they’ve worked hard to acquire, and the “have-nots” scrounge through the stale contents of mini bars in vacant resorts. In another future after economic collapse, all those empty timeshares become apartments for the formerly houseless, and hotel kitchens turn into community hubs where people bring fish, breadfruit, guava, and kalo to cook together. In the absence of financial capital, wealth could be redefined with different metrics: the land, water, and people right here with us.

NET PROPHET

MARY BABCOCK’S TEXTILE ART FOREWARNS THE FALLOUT OF A CONSUMERIST CULTURE.

TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ | IMAGES BY JONAS MAONAs the Great Pacific Garbage Patch continues on its path of destruction, the Hawai‘i-based textile artist Mary Babcock, a slim, relaxed woman with marks of the sun on her face walks along a long, flat beach near her home in Kailua, picking up discarded rope and netting on the sand. After she’s gathered everything available, she returns home to her studio, where she sets to work on another large-scale tapestry made from bundles of netting strewn about like mermaid hair.

“When I think about how much plastic is dumped in the water, it really makes me feel ill,” Babcock says. “We consume so much as a culture that it feels suicidal and homicidal. My work is about bringing awareness to materials and using materials that otherwise would be thrown away.”

Babcock’s fascination with fishing nets began in 2005 while she was living in Oregon, a place she calls her “heart space.” After graduating with a BFA in painting from the University of Oregon, Babcock took some time off to figure out what she really wanted to do. It wasn’t until she met a man who had started a net-recycling program along Oregon’s coast in order to keep fishermen from dumping nets into the ocean

that she found her calling. “I asked him if I could have any, and he showed me a room full of these gorgeous nets,” she recalls.

Though she experienced the coast while in Oregon and grew up near it in Rochester, New York (where she is originally from), Babcock didn’t have an immediate relationship with bodies of water until she moved to Hawai‘i. What she knew about the liquid elements came from faraway views of the ocean, clouded in hues of gray and dark brown, and from stories her parents told about a polluted Lake Eerie catching fire. But when she got the opportunity to move to Hawai‘i for a teaching position, she began seeing the changing moods of the ocean, from calm to angry, and water suddenly became an integral part of her life. “I learn about my own human psyche when I watch the water,” she says.

She was blown away by the colors of Kalama Bay, just down the street from her home in Kailua. Its swirling blues and greens became inspiration for a series of woven works entitled Hydrophilia I and Hydrophilia II (hydrophilia, in medicine, is the ability to combine with or attract water), both of which explore human engagement with each other and nature. “We name things that we care for, and the act of naming is also a connection to things,” she says. In naming one of her works “Kalama 2,” Babcock pays homage to the beach she walks regularly. “It helps me see the connection to place and [brings] attention to the public of what needs to happen there.”

Salvaging discarded materials from the ocean for more than a decade has made a lasting impression on her art and her teaching philosophy. In her classes at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where she is an associate professor in fiber and performance arts, Babcock helps students engage with their surroundings by looking at artists who are using recycled products and social spaces. The many layers of plastic woven together in this mixed media are a vessel for all that she wishes to convey: the current ecological state, the personality of the ocean, fishermen’s labor, and meaningful human connections.

Babcock’s improvisatory sensibility might have something to do with her upbringing: Her homemaker mother taught her how to sew at a young age, and her father, a naval architect and camera designer, fostered in her an adaptability and curiosity that led her to a career in the arts. “My grandparents came from Ireland to escape the potato famine, and my mother was constantly fixing my clothes and using what was available instead of buying it new,” she says. “So I grew up with this notion of, we can’t make it back like how it was, but we can try to repair it, and it won’t be perfect, but to be in love with it anyway.”

Her current work in progress, entitled Breaking Ground, is a large wax paper installation resembling a frozen waterway debuting at the Maui Arts and Cultural Center in August. It was inspired by the Buddhist concept of groundlessness, the way “the world is always shifting, moving,” Babcock explains. “It is only our concepts that over and over again attempt to force a kind of false permanence and solidity on something whose nature is otherwise. It is about the quiet fracturing of false ideologies that happens gradually and naturally under the light of awareness.” Looking to work with as many found materials as possible, Babcock found her niche as a forwardthinking environmentalist, artfully mending the old and discarded into the new and whimsical. “The interesting thing about mending something is that the scar is still there,” she says. “In reclaimed materials, there’s this memory that it was different at one point.”

Mary Babcock is represented by GalleryHNL, located in the Gentry Pacific Design Center, 560 N. Nimitz Hwy. For more information, visit galleryhnl.com.

“We can’t make it back like how it was, but we can try to repair it, and it won’t be perfect, but we can be in love with it anyway,” says artist Mary

here at

with discarded nets she utilizes in her work.

Babcock, shown Kailua Beach

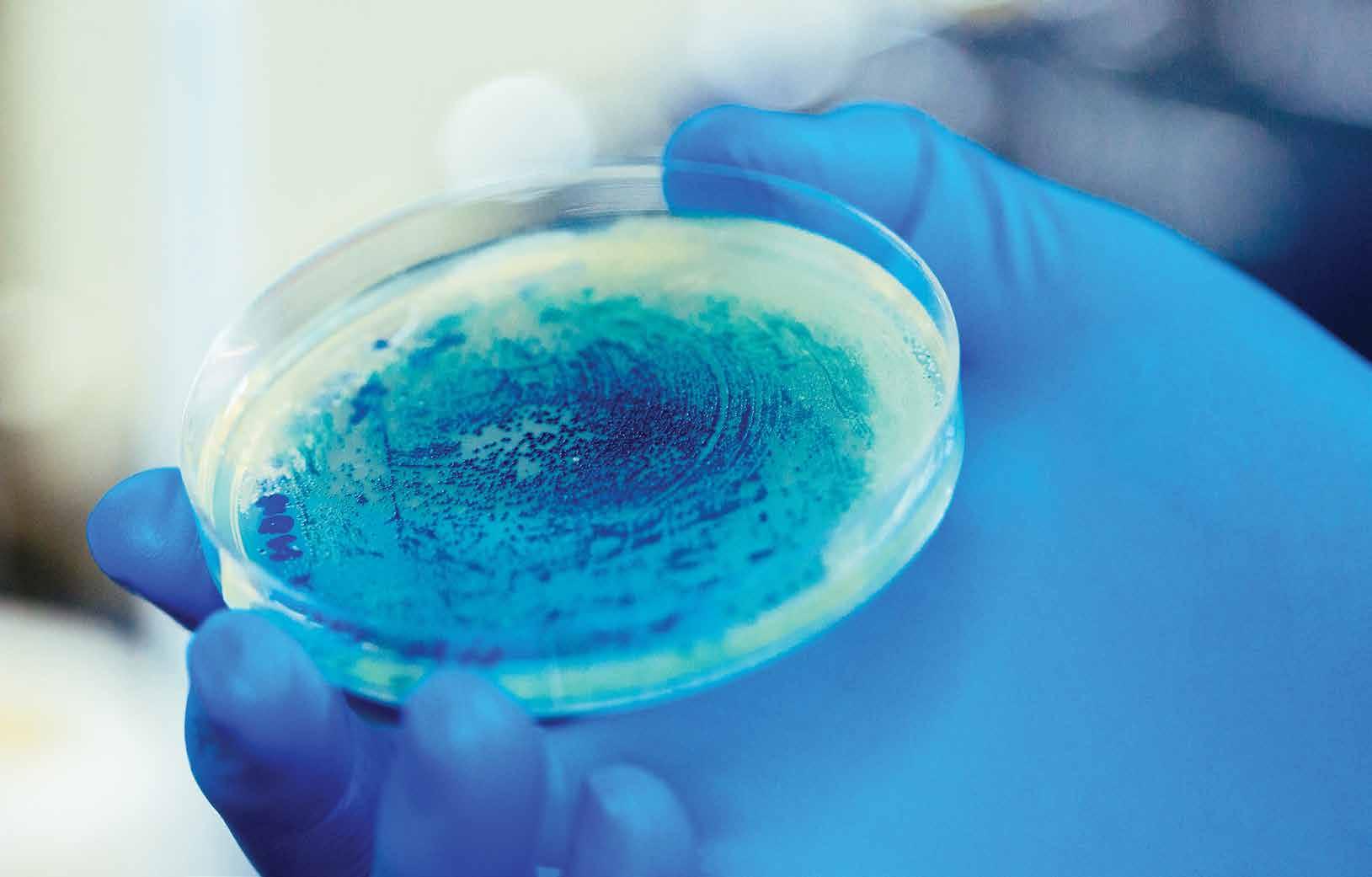

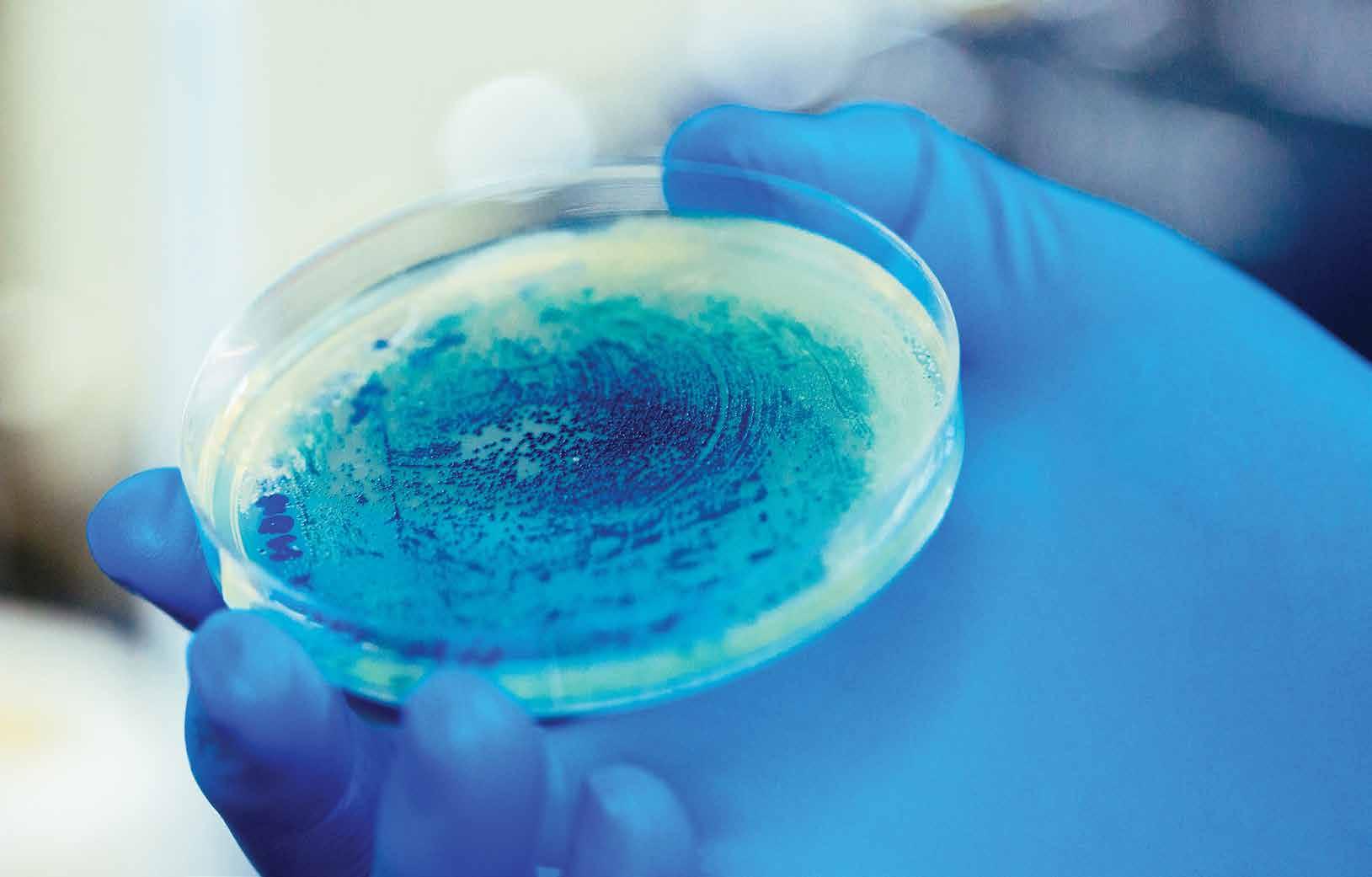

“Just because something involves a lot of complex ideas, that doesn’t mean you should just disregard it because it sounds scary or you think it’s not natural,” says researcher Robin Ka‘ai, who found his calling in molecular biology while enrolled in KCC’s STEM program.

ZOMBIE NATION

WHAT HAPPENED TO CRITICAL THINKING? WHAT HAPPENED TO THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD? ONE PROGRAM INOCULATES MINDLESSNESS.TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | IMAGES BY JONAS MAON

Year 2025: No one knows for sure what caused the virus. Or how it spread so quickly. It seems to have arisen from major metropolitan centers, those densely populated cities where a waning trust in science and technology left residents vulnerable. The infected idle mindlessly until provoked, then, like zombies, they gnash, snarl, lunge, and claw until their attention is drawn elsewhere. The disease continues to spread.

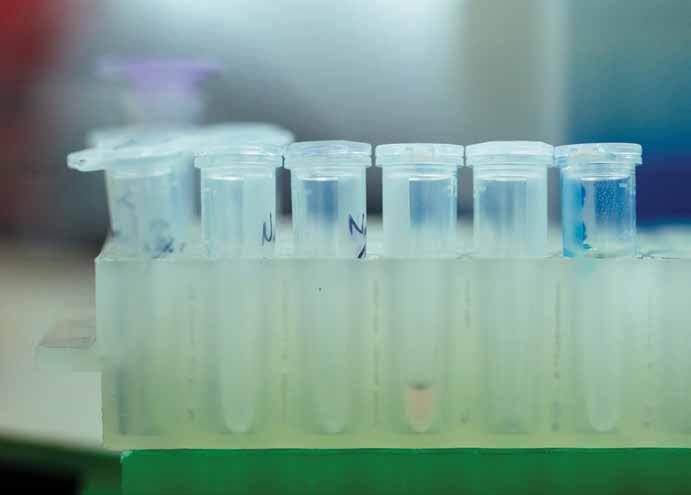

Year 2015. It’s nearing midnight and all is relatively quiet at Kapi‘olani Community College (KCC). There’s a low hum coming from the fluorescent lighting in a laboratory where undergraduate Robin Ka‘ai is waiting for DNA to be processed. It’s part of a project he’s been working on for nearly a year, one that attempts to create a more economical way to build antibodies by using genetically modified viruses. “What took me a year to work on is literally a clear drip of water in a tube,” Ka‘ai says. “You don’t know what’s in there until you stick it in this machine, and you see the DNA is present. If it is, you get to see a nice band on the computer, and you might have been successful.”

In addition to attacking viruses that make you sick, antibodies are used as a diagnostic tool for a multitude of things, including HIV and pregnancy tests; they’ve also recently been used to treat certain types of cancers, though the high cost of these types of treatments (some in the hundreds of thousands of dollars) results in many insurance companies refusing to cover them. “One person gets sick, but you can crash an entire family if you’re talking about paying $100,000 a year for these antibody treatments,” Ka‘ai says. “You’re killing the livelihood of an entire

family because it’s so expensive to produce antibodies. So this was our way of asking, what if we could convince the E. coli bacteria that you normally find in cat poop to make [these antibodies]? … You would bring down the skill sets required to people who work in an entry-level microlab instead of a specialized facility.”

Complex projects like these are common in KCC’S STEM program. Established in 2005 with a $1.2 million National Science Foundation grant, the program’s purpose is to enhance the quality of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (hence, STEM) instruction. Another project Ka‘ai worked on following his antibody project, for example, involved using micro-algae that he genetically modified using an ultrasound and micro-bubbles to create a high-output, low-maintenance method to produce protein-based drugs for industrial use. The resulting data was sent to University of Calgary for further research on insulin production. Ka‘ai acknowledges that the research he and other students have done can be hard to understand, but that that shouldn’t deter people from trying to wrap their brains around it. “Just because something involves a lot of complex ideas … that doesn’t mean you should just disregard it because it sounds scary or you

think it’s not natural,” he says.

Ka‘ai wasn’t always a scientist. He grew up on O‘ahu’s west side, graduating from Wai‘anae High School in 2003. A month after, he enlisted in the Army as a healthcare specialist, a “fancier way of saying combat medic,” he says. In 2007, he deployed to Iraq, then Kuwait, but became increasingly dissatisfied with the level of care he was able to provide to the soldiers in his unit. “It would be one of me with 40 other people on a convoy, and it was this impartial lottery anytime there was a mass casualty,” he says. “Two of you will get really good care, and the others will get whatever else I can give you. … I got interested in healthcare because I wanted to help people, but it just turned into me buying you time before you could go to someone who could actually help you.”

After he was discharged in 2009, Ka‘ai decided he needed to ramp up his skill

set in order to exceed what he saw as the limitations of being an EMT. He decided to go into nursing and was accepted into programs at KCC and University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. Meanwhile, he had enrolled in a microbiology class at KCC taught by Professor Matthew Tuthill, who pushed Ka‘ai to look beyond what he thought were his limitations. “That was by far the most influential thing I had happen to me at KCC,” Ka‘ai says. “That someone told me … to have the confidence to get to where [I know I] can go, not just where [I think I] have to stop.” Ka‘ai soon came to the realization that instead of building his own skill set, he could help advance everyone else’s as well; he could, in fact, advance an entire field.

Ka‘ai withdrew his candidacies from both nursing schools, choosing instead to dive into STEM’s biotechnology and molecular science pathway, where he

learned cutting-edge research and gained recognition after winning awards at competitions around the country, including top honors at the John A. Burns School of Medicine’s annual Biomedical Sciences and Health Disparities Symposium for his presentation on the use of phage display to produce antibodies against Campylobacter jejuni. It was the first time a community college student had ever won the award. “I hate that biotech at KCC flies under the radar when it should be exalted as this bastion of research in the Pacific,” he says. “I’ve been up to the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, and the level of research they do there is comparable with some of the stuff that we do right here.”

The question of how far to take science is one that Ka‘ai has seen played out in the story of Henrietta Lacks, a poor, black tobacco farmer whose cancer cells were, without her knowledge,

“We create the tools to allow technology to move forward. We’re not always equipped to handle the philosophical side, and that’s where other stakeholders have to come to the table and figure out what’s best for society,” says Professor Matthew Tuthill.

biopsied by researchers at John Hopkins University shortly before her death in 1915. Researchers later discovered the aggressive cancer cells were immortal, meaning that they could thrive eternally in a lab. Today, Lacks lives on through these HeLa cells, as they are called. They remain the most widely used cell line in research, cited in more than 74,000 scientific studies, and have provided insight leading to breakthroughs in vaccines (polio, for one), cancer and AIDs research, in vitro fertilization, and genetics. Despite the multi-billion dollar industry that sprang up as a result of HeLa cells, Lacks’ descendants can’t afford healthcare, a conundrum leaving Ka‘ai to wonder: How far do you push science for the betterment of everyone else, when it means allowing those like the Lacks family to fall by the wayside?

Tuthill says it’s an ethical question that science can’t answer. “We create the tools to allow technology to move forward. We’re not always equipped to handle the philosophical side, and that’s where other stakeholders have to come to the table and figure out what’s best for society.”

A lot of times, Tuthill says, dialogue about science, especially regarding things like genetic modification, can get extremely heated. “When it gets emotional, you can’t

talk to someone rationally about it,” he says. “I try to get students to think more critically and evaluate the data they’re seeing and let them make their own decisions rather than someone else making the decision for them.”

Ka‘ai agrees: “We sit in our meetings and argue with each other all the time, but it’s that dialogue that’s important. It’s a more open-ended way of approaching these problems.” Instead, Ka‘ai continues, there’s an intense mistrust in science that’s going to drive a lot of our problems in the future. “If it’s that important to you, go out and get an education. Change policies, educate your community about what that impact is having on them. That’s how you defend Hawai‘i.”

Doing just that, Ka‘ai, who transferred to UH after receiving his associate’s of science degree from KCC in 2012, will graduate this summer with a bachelor’s degree in molecular cell biology. He hopes to go on to get dual degrees as a doctor of medicine and doctor of philosophy (referred to as an MD-PhD) and become a research physician. “I’m not the smartest person that came out of Wai‘anae, I know that for a fact,” he says. “But if I could get this far, someone better than me could make it much further.”

The heart of Chinatown since 2005

The heart of Chinatown since 2005

“The realization we’re going to have to return to is that doodoo and water don’t mix,” says Kanoa O’Connor, who is studying how ancient Hawaiian populations managed their excrement.

YOU DON’T KNOW SHIT

TRACING DOODOO ON THE ISLANDS FROM ANCIENT TIMES TO APOCALYPTIC FUTURES.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON | IMAGES BY JONAS MAONUp shit creek. When shit hits the fan. Don’t give me that crap. Don’t be an asshole. What a brownnoser. You’re such a turd. I’ve got a shitload of work, OK?

We use poop as a dirty word all the time. But we also rarely speak of it. When I started this story, I knew nothing about poop. My interest began with horror reports of bacteria on attack, algae blooms, Ala Wai canal going septic, cesspools leaking into bays and causing sores that wouldn’t heal. I wanted to know where my shit went, and what it meant when my shit went wrong. Because it can go wrong. If our shit seeps into our water, if it touches our food, if it piles up and festers, it can kill us. But it can also go the right way, giving back to a natural cycle with rich nutrients that are food for microorganisms and fertilizer for plants. In case of apocalypse, if we don’t know what to do with our excrement, we may very well be up shit creek. So I had a mystery to solve. Where does our doodoo go, exactly, and what will we do with it if the world as we know it ends?

MAKING DIRT

It’s 9 a.m. at Kenny’s Diner in Kalihi. Across from me in a semi-circle booth sits Kanoa

O’Conner, a large man with curly hair nearly as voluminous as his booming voice. After our waitress stops by our table with a slice of rainbow cake, coffee, and a chicken sandwich with fries, we get down to talking dirt. “To me, Hawaiians had to be super clean,” he says. “You’re not going to have a million people living here [if] you’re not.”

O’Connor has earned the nickname of “doodoo boy” from the professors at the Hawaiian Studies department at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, where he is pursuing his master’s degree. After earning his bachelor’s from Stanford University in environmental engineering with a focus in wastewater management, he realized he had little knowledge of how his ancestors handled the same thing in ancient Hawai‘i. Now, he is trying to solve the mystery of poop, searching through everything from missionary documents to ‘ōlelo no‘eau, or traditional proverbs.

Early on, he discovered an article by O.A. Bushnell, “Hygiene and Sanitation Among the Ancient Hawaiians,” published in 1966 in the Hawaii Historical Review. It is one of the only academic pieces that explores how the far-flung population handled its bodily functions and protected its streams and springs from contamination. “Out of respect for the gods, the Hawaiian refrained from polluting their abodes,” Bushnell writes. “Out of fear for himself, he was most careful to keep his body’s parts, or its wastes, and his personal possessions from falling into the hands of the dreaded sorcerer.” Poop, Hawaiians believed, carried mana, or life force, and was considered an

extension of oneself. In one mo‘ōlelo, or story, a jealous sorcerer from Lāna‘i travels to Kaua‘i to steal the excrement of powerful prophet Lani-kaula. He brings it back to Lāna‘i, where he sets it on fire. Lani-kaula senses what has happened right away, and realizing he is going to die, orders that he be buried under stone knives so his bones are not used for fishhooks.

But using the bathroom was, realistically, a daily chore. Mary Kawena Pukui compared the sanitation practices of ancient Hawaiians to that of cats: They buried it all the time. O’Connor theorizes that the way poop was disposed of varied by location and social status. “The ali‘i had a special retainer (servant) that would collect their doodoo inside a calabash, and then in the cover of night, go take care of it for them,” O’Connor says. “That wouldn’t have happened for a maka‘āinana (commoner), because you would have had to take care of your own shit.”

In another mo‘ōlelo, a chief gets diarrhea while traveling along a path and stops to relieve himself. A runner passes by, and the chief asks him how it was back at his starting point. Very wet and full of fish, the runner tells him. It’s not until the chief returns to his retainer and passes along the news that he realizes the runner’s answers were a joke about his poop, not the weather.

“Even though we have this understanding of these social constructs [in ancient Hawai‘i], sometimes that might not have even been true,” says O’Conner. “Sometimes an ali‘i would have plopped down by the side of the road and done his

business.” Generally, he says, if you were out fishing, you went in the ocean; if you were traveling along a path, you stepped off to the side and dug a hole; if you were living in a dry, volcanic area, you most likely had a designated communal lua, or hole in the ground, since digging an individual one every time would be nearly impossible.

According to O’Connor, ancient Hawaiians had a bounty of language to describe the act and product of defecation. Kūkae is commonly used today, but according to O’Connor, the more appropriate words that were used were honowā, which refers not only to poop but also what is inside of your intestines, and hana lepo, which literally means to make dirt. “We had an understanding of the connection of poop and dirt,” O’Connor says.

But digging holes, as he has tested, isn’t convenient. “It’s so easy to flush,” says O’Connor, who remedies this with his own methods for conserving water. “I don’t flush anymore when I pee, and people get angry at me. … To me, something like a composting system really does solve all the problems, but it doesn’t solve the easiness problem. I don’t know if you can ever solve the easiness problem and the healthy-for-the-land-andwater-and-people problem, too.”

In a post-apocalyptic wasteland, O’Conner theorizes, “The realization we’re going to have to return to is that doodoo and water don’t mix.”

SANITIZING SLUDGE

“Basically, I’m trying to figure out where my poop goes,” I tell Markus Owens, the public relations officer for Honolulu City and County’s Department of Environmental Services, when we meet at Sand Island Wastewater Treatment Plant. A tall, broadshouldered man who moved to Hawai‘i to play baseball at UH in the 1970s, he takes a coach’s encouraging tone as he works me through the complexities of pumping stations, the technology for fixing cracks in pipes, and the work that goes into getting our poop out of our way.

When someone flushes a toilet back in Pālolo Valley, excrement and several gallons of previously clean water travel into pipes, where they flow downward along with sewage from other toilets, showers, and sinks. This is also joined by water—a lot of it, if there has

been a storm—that seeps through flaws in the pipe, which can introduce contaminants lingering in the ground like dieldrin, used as a termite pesticide before being banned in the 1980s. This concoction arrives to the Ala Moana pumping station, then is sent along to the Sand Island Wastewater Treatment Plant. Here, the poop water is screened for trash like tampons and gravel, then piped into what looks like a giant mixing bowl. Egrets flock overhead as a massive wand slowly churns the dark gray water. The point of this tank is to separate solids and fluids. Ferric chloride and polymer (which cause the gray color) are added to help speed up this process. Effluent, as the water is now called, is then run under two sets of UV panels to neutralize most remaining microorganisms (by far the most energy intensive part of the process, Owens estimates that it costs close to $5 million annually to operate). Then, the water is discharged a mile and a half out from land, 240 feet below the ocean’s surface.

The solids that settle in the tank—made up of dying bacteria and fiber from poop and toilet paper, along with contaminants like metals and chemicals from cleaning products or prescription pills—are now called sludge. This is treated, thickened, heated, dried, and then turned into pellets the size of rabbit dung in a giant white globe operated by Synagro. These pellets, deemed biosolids, are used as fertilizer by commercial farms, landscapers, golf courses. At the time this article was written, anything not reduced to a small enough size—usually about 7 percent of solid matter—was sent to the landfill, along with the rest of the solid waste created by eight of Honolulu City and County’s nine other treatment plants (La‘ie composts its own). Annually, this adds up to about 200,000 tons. However, if everything went according to plan during an April 2015 test run, this is all now trucked over to H-Power, where it will be burned as part of our state’s sustainable energy plan. Manmade power to da max.

However, issues arise with our modern sewer system in several ways. If sewer pipes fail or overflow, groundwater can be contaminated with feces—a danger that has caused overseers to flush raw sewage into canals emptying into the ocean instead. Also, the system requires hundreds of gallons of freshwater to be removed from their watersheds each day and turned into

wastewater. Finally, if a large disaster wipes out any of our ocean-side treatment plants, those connected to it can expect to see sewage flowing out of manholes, pump stations, and even their own toilets—a health hazard of watershed proportions.

Hawai‘i’s first modern sewer facility was the Kaka‘ako pumping station, a charming lava rock building with large paneled windows that still rests, now retired, just off Ala Moana Boulevard. Built in 1900 in the trend of sewer management coming out of Europe, its job was to pump untreated sewage into the ocean. “The solution to pollution is dilution” became the rule in all kinds of pollution management. Water was the perfect diluent, hence the primary dumping ground. The Environmental Protection Agency was finally founded in 1970 and the Clean Water Act widely recognized in 1972, inspired by such things as rivers catching fire.

Built in 1928, Wahiawā Wastewater Treatment Plant is the oldest in Hawai‘i, as well as the only one on the island that discharges into a freshwater body, Lake Wilson. For this to happen, the water receives tertiary treatment, the highest level of treatment after primary and secondary, before being considered recycled. On the other hand, the Sand Island plant, which was opened in 1976, only performs primary treatment of wastewater, one of the last in the country allowed to do this. In 2010, the EPA issued a decree requiring Honolulu City and County to upgrade this plant and the Honouliuli Wastewater Treatment Plant to perform full secondary treatment, as well as fix pipe leakage by 2035. Both plants have completed 381 of 484 milestones, but the conversions of the wastewater treatment plants loom ahead.

While this may bring to mind an everexpanding network of underground pipes around the islands, our sewer systems are limited to urban areas. Hawai‘i, in fact, has the largest number of cesspools in the nation—about 90,000 total. If someone poops in Pūpūkea, for example, at a house connected to a cesspool, the doodoo water doesn’t go on a long-distance journey; instead, it is sent down into an underground hole or well, where solids settle and water leeches out through the wall, filtered by layers of earth and plant roots.

This is a much simpler, cheaper route,

Lauren Roth Venu at her original Living Machine project, which was fabricated from a repurposed shipping container to serve as a mobile ecological wastewater treatment demonstration system. It is now owned and operated by Partners In Development and located at the Makiki Nature Center.

WAYS WE HANDLE OUR POOP

WET SYSTEMS

CESSPOOL : an underground well into which wastewater flows. Solids settle to the bottom and water leeches out through sides, where it is further filtered by soil, microbes, and plant life.

SEPTIC TANK : an underground enclosed tank where solids settle and are anaerobically digested. Water typically flows into a drain field.

SEWER SYSTEM : a network of pipes and pumping stations take wastewater from toilets, sinks, and showers to a centralized wastewater treatment plant.

DRY SYSTEMS

COMPOSTING TOILET : a dry toilet in which human waste is composted.

BUCKET TOILET : a rudimentary composting toilet in which waste is layered with peat moss or sawdust, then disposed of in a compost pile.

LUA : in Hawaiian, a hole in the ground used as a toilet.

but one that can backfire. Cesspools inundated by overuse aren’t able to give the matter appropriate settling time, causing wastewater to seep into the ocean or groundwater. Last year, spurred by ocean contamination along the coasts of Maui and O‘ahu, the Department of Health proposed an amendment that banned new cesspools and required existing ones to be converted to septic tanks (encased underground tanks that perform primary treatment) when the homes were sold, but it did not go over well. The majority of Maui, in fact, does not have access to a sewer system. Its three county-owned wastewater treatment plants all produce some recycled water, but the county is still determining the direction to take its poop since centralized systems mostly mean draining water into the ocean. Maui is a much drier island than O‘ahu, and wastewater is wasted water.

In early 2015, two bills were introduced to state congress that requested funds to research water scalping, which involves pulling wastewater early in a sewer journey and sending it to a more localized treatment center that would refine the water to a recycled level, again for local use. When I asked Owens if his department thought they were promising, he said yes, but that there were concerns. The department appreciates efficiency and knows scalping would decrease the amount of water processed at the plant. However, they hesitate because with less water in the system, poop moves more slowly and begins to ripen, releasing methane gas and nitrogen that could corrode the pipes if they are not resized. (This is the cause of Kaka‘ako’s methane stink, since there isn’t enough water to consistently keep things moving through pipes scaled for a larger population). The other thing? Cost. All of the money that is paid in sewer fees by property owners already goes straight into maintaining the system. They know the uphill battle that would surround adding another dollar to that monthly sewer fee to fund such research. There is no budget to plan for the future.

This is personal—we don’t want to pay for shit we no longer understand.

FEEDING LIFE

“I was essentially shipped here with the container,” jokes Lauren Roth Venu, a tall woman with a tomboy tone. We are at the Makiki Nature Center, standing beside a repurposed 4-foot-wide by 8-foot-deep shipping container called the Living Machine, outfitted with solar panels and a blue paint job. Once wastewater reaches a certain level in the center’s septic tanks, it is flushed into the shipping container. Here, it moves through different sandy-bottomed compartments populated with plant life, fish, microbes, and snails. “Waste is food for living things,” says Roth Venu. Microbes render nitrogen into a usable form for the plants, and fish dine on solids. As the water runs through its wetlands journey, it becomes more oxygenated and poopfree. When it is sent out for irrigation, it is recycled water.

Roth Venu oversaw this container at its first stop, the old slaughterhouse on Fort Wheeler Road in ‘Ewa, where it treated water used to wash the facilities and holding pens. She populated it with native plants and koi. In 2006, she founded Roth Ecological Design International, and today she consults on and oversees a variety of projects in state and abroad. “The city is constantly just putting out fires and doesn’t have time for long-range planning,” says Roth Venu, who serves on the board of the State Water Commission and is on the committee that advises the Department of Health on their water reuse guidelines.

“I like the idea of mimicking the watershed,” she says of the natural flow of water from mountain to ocean. “If we can maintain and manage our water within the watershed, including our service, then there is no net in and out; we’re not diverting.”

Take Makiki Nature Center, for example, where water is treated on-site before being used for irrigation, entering the ground and making its way down the mountain. This model can be expanded to entire communities within watersheds. An easy place to start is at home with a rainwater catchment and gray-water system. She has also been in strategic planning sessions with

regulators about onsite systems within highrises that would treat water to be reused for flushing toilets or maintaining coolant systems, instead of it having to be piped in and out. While poop would still be sent to a centralized system, any sludge from a septic tank could theoretically be pumped and composted.

In June 2014, Roth Venu finished an onsite wastewater system at the Kaiser Permanente Medical Office in Kona. Here, primary treatment takes place in septic tanks, after which water flows through an outdoor constructed wetland, rendering it clean enough to be used for irrigation. A nurse thought the flowers from the wetland were so pretty that now, once a week, its operator clips blooms that are delivered to patients.

If apocalypse were to arise, this facility actually may have its shit somewhat figured out. But what about the rest of us? “I would say you probably shouldn’t flush toilets,” Roth Venu says. “You probably should go to a compost toilet. I don’t think we’d have the luxury of using water that way.”

“You’re writing about poop? Do you know about the humanure handbook?!!!” a friend texts me excitedly. Now in its third self-published edition, The Humanure Handbook envisions a world of humanure compost heaps that are the boon of gardens. It features drawings of composting toilets that make readers giddy. It also confirms what ancient Hawaiians observed, O’Connor knows, state and county departments are facing, and Roth Venu is trying to solve: Water and doodoo should not haphazardly mix. When apocalypse hits, a new system will have to be agreed upon, one requiring creativity and native intelligence. If you find you have survived the end of the world, grab a bucket for your bowel movements, start a compost heap far away from your stream, and make do with dirt, you lucky little shit.

THE BEGINNING

36–40: THE LEADER

You are a born leader. You are calm in crisis and see what everyone has to offer. Where you lack sympathy, The Moral Compass steps up to the plate.

29–35: THE MORAL COMPASS

Without you, a group would fall to pieces. You listen to concerns, think the best of everyone, and know right from wrong. You and The MacGyver have a love-hate relationship.

21–28: THE MACGYVER

You can whip up a flotation device with just a pincushion and monstera leaf. Your innovations constantly surprise the group and solve problems that would confound everyone else. The Muscle often comes in handy for your schemes (which can also go awry).

14–20: THE MUSCLE

You, my friend, are strong and swift. Your survival instinct is powerful, but you may be a little hotheaded. In this case, turn to your friend The Gatherer for some calming kava.

6–13: THE GATHERER

You know where to find young ho–‘i‘o, mountain apples, and wild ginger. Your lack of social skills and hermit ways actually come in handy, since you can spend long amounts of time alone in nature.

REAL LIFE ON FAKE MARS

A CREW OF SIX PLAY INTERSTELLAR HOUSE FOR A NASA-FUNDED RESEARCH PROJECT ON MAUNA LOA.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON IMAGES COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA

As

NASA prepares to launch its first mission to Mars in the 2030s, Hawai‘i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation crews have been simulating life on the red planet on Mauna Loa’s eastern slope. Shown here is Angelo Vermeulen, wearing the MX-B simulated spacesuit. Photo by Yajaira Sierra-Sastre.Crewmember Zak Wilson enters a brightly lit airlock, where plants grow in coffee cans hung on pegs, and residents flock to feel natural sunlight. He steps into a bright yellow HAZMAT suit and zips it up, entirely encased as he looks out through its clear plastic mask.

He opens a heavy door, stepping out with another HAZMAT suit-encased crewmember onto red, rocky terrain. They venture into a nearby lava tube, take notes, map out its unique features, then walk back to their home—for now, a bright white dome appearing as a mere dot along the slopes of Hawai‘i Island’s Mauna Loa.

In the last few years, Mars has suddenly appeared within reach of human grasp. NASA plans to launch its first mission to the red planet, a short-term research trip, in the 2030s. In 11 years, Mars One, a private venture, expects to have deployed a crew of four to begin colonization, filming a reality TV show as they go. But those who know most about what life on Mars may really be like are crewmembers who have spent stints holed up in habitats in the Canadian Arctic, Russia, Utah, or Hawai‘i Island for various Earth-based projects researching habitation on Mars.

Since October 2014, six “astro-nots,” including Wilson, have been living in a dome on Mauna Loa’s eastern slope, a location selected for its strong resemblance to Mars’ extraterrestrial terrain (barren red landscape, shield volcanoes, lava tubes). These six sojourners are the crew of Hawai‘i Space Exploration Analog and Simulation (HI-SEAS) Mission III, one of four missions funded by NASA, ranging in length from four months to a year. The first mission was an independent phase that focused on food—what the crew ate, how they made it. The current series of three is focused on crew psychology, with five institutions, including

University of Michigan and John Hopkins University, collecting data on what causes fissures or cohesion within the group. Mission III is the longest yet, ending June 12, 2015. Crewmembers include a combat veteranslash-microbiologist, an aerospace engineer, and an intelligent-robotics researcher. All were chosen for their astronaut-like backgrounds and personalities. They live daily life as if actually surviving and researching on Mars.

The things they experience, and the difficulties they encounter, will directly impact protocol and plans for NASA’s pending mission. Principal investigator Dr. Kim Binsted, a professor at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, is focused on how the different crews of each of the missions develop relationships and effectiveness over time. One thing that she is on the lookout for is symptoms of a third quarter effect, when it has been theorized that crewmembers will experience depression and lethargy.

Another factor impacting the crew is the 20-minute delay in communications with “Earth” that astronauts on Mars will encounter. (It will be the first time in human space travel that this will occur.) “There is a really strong tendency for communication breakdown between an isolated team and the crew at home,” Binsted explains, and the delay will only exacerbate that. Frustrations may arise, miscommunication could proliferate, and dangers to the crew would increase. On an already challenging host planet with lower gravity, dangerous solar flares, and lack of easily accessible food or water, this could mean mission incomplete. But if this research does what it aims to do, such human complications may be prevented.

Beyond missions or objectives, what HISEAS also shows is the reality of daily human life on Mars. Crewmembers exercise with resistance bands, clean their compostable toilet, play board games, attempt repairs with a 3-D printer, conduct individual research projects. Each gets a single, eight-minute shower per week (the minimum found necessary in order to maintain morale). Much of the day is dedicated to meals. The crew lives off a food stock similar to what NASA would provide, including freeze-dried meals, dried fruits and vegetables, potato flakes, flour, powdered milk, and canned meats, as well as the occasional fresh produce grown under LED lights on loan from the Kennedy Space Center. They bake bread in the toaster oven and take turns making meals. Holidays are celebrated with inventive feasts.

While recording a virtual tour of the habitat, crewmember Jocelyn Dunn introduces the cramped kitchen this way: “Here we are in the HI-SEAS kitchen. It’s really the heart and soul of the mission.” On a hot plate to her right, a gumbo prepared by Wilson simmers away.

FLUX HAWAII GROUND CONTROL TO HI-SEAS EXPLORERS.

We asked crewmembers to imagine that they got called on a real-life mission to Mars. The following is our correspondence.

You just got the exciting news that you’re taking a real-life, one-way trip to Mars. What three things do you bring?

Jocelyn Dunn: Slippers, MacBook Pro, and Chapstick.

Zak Wilson: A 3D printer—I could manufacture parts on my own instead of having to wait for a resupply.

Neil Scheibelhut: Camera, iPad crammed with games, cowboy hat, and boots. If I had to only take one of those, it would be the hat.

What is one thing you will miss about Earth?

Dunn: Besides people, I would miss going to the beach. Even while here on simulated Mars, I yearn for the feeling of the sun warming my skin and for the refreshment of swimming in the ocean.

How do you expect to get that all-essential H20 on a planet with no reservoirs or running water?

Scheibelhut: There are actually many, many ways to obtain and reuse water. Besides reusing water brought along on the trip to Mars, urine can be cleaned and reused. In addition, water can be extracted from other forms of waste, like paper products. Once astronauts reach Mars, it will actually be easier. The polar ice caps found on Mars have literally tons of water that can be melted, cleaned, and consumed. Ice can also be found within the soil and extracted. And, in the rare case when water cannot be extracted from the soil, the soil itself can be used to create water. The red color we see all over Mars is due to the presence of large

amounts of iron oxide. Through a series of chemical reactions, the oxygen trapped in the soil can be united with hydrogen (which is also plentiful on Mars in other forms) to create water.

What are you going to do to manage waste?

Lenio: Anything organic should be composted and reused as soil. I’ve been using a type of anaerobic composting system called Bokashi to turn our food waste back into soil, and have been successfully using it to grow new food for us.

Hollywood glamour of interstellar life aside, what do you think day-to-day life will actually be like?

Wilson: I think a large amount of time will be spent on maintenance and other fairly mundane tasks like tending to gardens. The level of technology required to sustain humans on Mars is quite high, and the consequences for a systems failure is potentially catastrophic. Large gardens would be required to permanently sustain people on Mars, particularly without

resupply from Earth.

Unlike Earth, Mars doesn’t have a magnetic field or dense atmosphere to deflect most solar flare radiation. How do you plan to survive the threat of solar flares?

Sophie Milam: One of the standard practices for astronauts in danger of solar flares is something our early ancestors would have agreed on: If danger is coming, run and hide in a cave. On a spaceship or space station there isn’t a cave per se, but there is a very solid, very small area specially reinforced to protect astronauts from harmful radiation. Around our habitat, there are systems of lava tubes and caves that are analogous to real Martian terrain. Astronauts on Mars will have to position their habitats close to these kinds of structures and outfit them as a kind of emergency shelter.

Back to planet Earth. Having been part of HI-SEAS, would you sign up for that oneway trip to colonize Mars with Mars One?

Allen Mirkadyrov: Probably not. I have

many responsibilities to other people who depend on me, so I could not consciously volunteer for an inevitable death.