SHAKAS: A FIELD GUIDE

THE WEATHERMAN: GUY HAGI

THE ALOHA OF VALETS

SHAKAS: A FIELD GUIDE

THE WEATHERMAN: GUY HAGI

THE ALOHA OF VALETS

34

What is it like to tell the forecast in a place with the best weather on the planet? Guy Hagi has the story.

OF CONTENTS | FEATURES |

40

For locals and visitors alike, valets set the pace for experiences to follow. Beau Flemister writes about what it means to be a great valet in a state that celebrates its aloha hospitality.

Hawai‘i is one of the most popular places in the world to get married. Sonny Ganaden takes a look into the booming business of island-style matrimony.

54

Though karaoke traces its roots to Japan, it is in Hawai‘i that the pastime is perhaps most beloved. Le‘a Gleason explores how karaoke is waking up sleepy Hilo town for both young and old, breaking boundaries and connecting residents with each other.

A showcase of locally designed, islandinspired looks by Jeffrey Yoshida, Tutuvi, S.Tory Standards, Roberta Oaks, Virginia Paresa, and Language of the Birds.

Makiki Community Library remains the only volunteer-run library in the islands.

Roger Bong’s Aloha Got Soul vinyl record label shares music that might otherwise be forgotten.

Tokunari Fujibayashi comes from 12 generations of a Japanese textile-designing family and began weaving and dyeing under his father’s tutelage in fourth grade.

LETTER

THE FLUX?! THE SHAKA FIELD GUIDE

NEW YORK CITY

KINFOLK 94’S JEREMIAH MANDEL

SHOP TALK : MORI BY ART AND FLEA FOOD 84 THE MANGO : RECIPE BY VIA GELATO’S MELISSA BOW ITINERARY 86

NEW YORK CITY HANYA YANAGIHARA’S A LITTLE LIFE

KAUA‘I’S HANAPĒPĒ TOWN 90

EXPLORE : KAUA‘I’S TARO KO

RAP’S HAWAI‘I, OUR HAWAI‘I

Want to broaden your shaka vocabulary?

Rayton Lamay explains the different types of shakas and shows you how to accurately position thumb and pinkie for maximum aloha appeal.

Go behind the scenes of our fashion shoot. Venture with the FLUX Hawaii crew from Nu‘uanu’s Pali Lookout to Waimānalo, and see all that country living has to offer.

Whip up a mango sorbet for your next dinner party to go with the deceivingly simple mango cheesecake recipe on page 84. Find the sorbet recipe online at fluxhawaii.com.

Post a picture of your shaka in the wild and tag it with #fluxshaka @fluxhawaii on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter for a chance to win a shaka prize pack, which includes a Kona Brewing Company longboard and a $100 Hawaiian Island Creations gift certificate. Contest runs from August 17, 2015 to August 31, 2015.

“Am I doing this right?” Shown on the cover is Rayton Lamay, who shows us on page 21 the slight nuances in the international symbol of aloha—the shaka. Born and raised in Lāna‘i City, Lamay is the first in his family to graduate from college, obtaining an associate’s degree in the music and entertainment learning experience program, or MELE, from Hawai‘i Community College in June 2015. The aspiring comedian, who does a mean impression of Governor David Ige and Manny Pacquiao, represents everything we love about Hawai‘i: drive, ingenuity, humor, sincerity. Follow him on Instagram @rayraylamay.

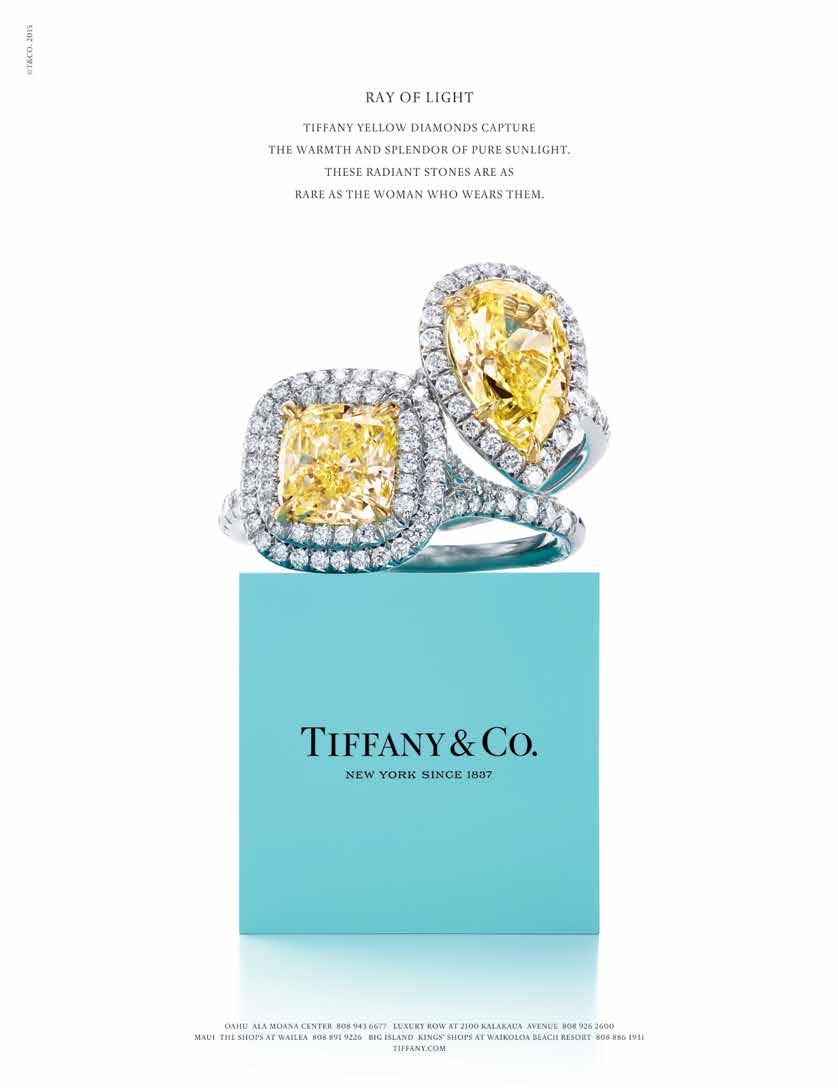

During the Industrial Revolution, charms, often cast by master goldsmiths, were considered a sign of wealth. As technology advanced and jewelry became massproduced, the popularity of these trinkets added onto bracelets or necklaces grew among the middle class, peaking in the United States after World War II, when soldiers brought charms home from European cities. Today, they have become the gift du jour at young girls’ birthday parties the world over.

When I first thought about doing a charm-themed issue of FLUX, I imagined the stories we’d feature would be those enchanting countenances filled with an oh-soendearing, magical quality; akin to a charm bracelet, each story would be one that exhibited a unique facet of Hawai‘i. The stories were meant to fill us with the same warm, fuzzy feelings we get when we pass through small towns and remark, “Oh isn’t that sweet.” The problem, I began to realize, was that I don’t know anyone above the age of, say, 10 who actually wears charm bracelets. And if they do, the ones they wear are often only fanciful from afar. Up close, it’s easy to see their tawdry nature.

The story of these charms is ultimately the story of Hawai‘i, a destination enjoyed by the wealthy in the early 20th century, when air travel to the islands first became possible. In post-WWII years, Hawai‘i became a mass-marketed destination presented as a “paradise” filled with aloha spirit and natives whose hips swayed in unison with palm trees. Tourists returned home with plastic lei and fake-grass hula skirts. Subsequently, residents and increasingly savvy visitors backlashed, calling for a more authentic Hawaiian experience. Cue pancake tours at our favorite hole-in-the-wall breakfast joint and double-decker busses pulling up at the farmers market. This year, the number of visitors to Hawai‘i is expected to climb to a record 8.5 million, up 2.5 percent from last year.

Try as we might, we can’t seem to shake the image that has defined us for more than half a century. Hawai‘i is the most beautiful place in the world, but it has its fair share of problems, too: Homelessness has reached monumental proportions; affordable housing for young adults is the worst in the country; traffic is only slightly better than in Los Angeles and San Francisco; we live in a place rated as the worst state to make a living and the worst place to do business.

And yet, in spite of it all, local people—from valets to weathermen to surfers to senior citizens—still find reasons to smile in a place Anthony Bourdain calls on his recent trip to the islands for his CNN show, Parts Unknown, “both the most American place left in America (in the best and worst senses of that word) and the least American place (in only the best sense).” Resilient, perhaps a bit bullheaded at times, we find some way to climb to the top of the only list that matters: the one about our quality of life. Charm can be a fleeting concept, but there’s something enduringly charming about the kind of people who love even when it doesn’t make sense, who share an evershrinking piece of paradise wholeheartedly and without pretense. After all these years, after decades of being the backdrop in someone else’s movie, we’re finding the best way to remain charming is to be ourselves, the kind of people who, upon closer inspection and despite Hawai‘i’s shifting landscape, stay golden.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor lisa@nellamediagroup.com

WHAT DO YOU FIND CHARMING ABOUT HAWAI‘I?

“This is the only place in the world where I felt like I belonged, the place I can proudly call my home.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

ARTS & CULTURE

DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Mike Caputo

Mark Ghee Lord Galacgac

Jonas Maon

Zak Noyle

Meagan Suzuki

“No matter where you are, a Spam musubi is never a far drive away.”

CONTRIBUTORS

James Charisma

Beau Flemister

Le‘a Gleason

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Travis Hancock

Mitchell Kuga

Shivani Manghnani

Meagan Suzuki

Coco Zickos

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Carrie Shuler MARKETING & CREATIVE COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Matt Honda CREATIVE & INNOVATION DIRECTOR

Michelle Ganeku DESIGNER

INTERNS

Brad Dell Jackson Groves

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

“Of the many small communities in Hawai‘i, you can belong to more than one.”

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

©2009-2015 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

Beau Flemister, who worked as a valet for 15 years in Hawai‘i, lets us in on a little secret: “A valet will do just about anything for a $20, will damn near bury a body for a $50.”

But, it’s not just about the tips, he explains in his story about the charm of local valets on page 40. The editor-at-large of Surfing Magazine, Flemister also set his novel, In the Seat of a Stranger’s Car, within this service industry. In June, he set out on an eight-month trip around the world with his wife visiting reindeer tribes in Mongolia, sea gypsies in Burma, and vampires in Romania. Keep up with him on Instagram @planestrainsballandchains.

Travis Hancock is a writer, skateboarder, and university lecturer from the North Shore of O‘ahu.

He likens his four-story ride with Javier “Javi” Fombellida, Hawai‘i’s last elevator operator, featured on page 25, “to a trip to the Jazz Age, revolutionary Cuba, and a haunted house all in one.” Hancock, who also wrote about the rainbow of meanings behind the shaka, describes himself as a “basic haole throwing superfluous basic shakas.”

JONAS MAON

JONAS MAON

As a creative lead with ARIA Studios, Jonas Maon has captured his fair share of weddings, and in doing so, has crossed paths with his fair share of valets.

Shooting for our valet story on page 40, Maon says, “It was interesting to watch them in action, particularly when the cars started streaming through. While it was difficult for me to get shots at times (they were still working!), it was probably more difficult for them to stand motionless and smile while their coworkers zipped around, attending to their guests.” Maon, who dabbles in film and editorial photography, tends to be a night owl, but will get up early for a corned beef or adobo fried rice omelet.

My first purchase of this magazine was the spring ’15 Identity issue. Lovely photography and thought worthy articles. My only comment is with the article starting on page 43 titled “Check all that apply.” Very happy to see the issue acknowledging and reporting multiracial identities when filling out forms. Please note, however, “Jewish” is not an ethnicity, it is a faith.

Sharron Blanchette via Facebook

I got the [Apocalypse] issue of FLUX in the mail today, and it really looks spectacular. Not that it doesn’t always look great but I really liked this issue and wanted to let you know. I always get inspired when I see a nice magazine, so once the youngin’ goes to sleep tonight, the sketchpad will come out.

Brian Baldwin via Facebook

OR MAIL TO FLUX HAWAII, 36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A, HONOLULU, HI 96817.

Congrats to @green_eggs_n_spam for winning our #fluxidentity Instagram contest. She writes of her photo above: “My #fluxidentity is an educator—in part, an educator in what many deem to be a failing public school system in Hawaii, trying to give students with special needs tools others may not consider them worthy of, or don’t believe they are capable of using correctly so that they may determine their own futures; and also in part as a full-time single mother striving to be, in many ways, someone her daughter is proud to call her mother.”

“My #fluxidentity is that I live in a special place that wants to stay the same but is constantly being pulled, shaped, and reinterpreted by all these varied ideas of what Hawaii is and should be. It’s most times beautiful, and other times a heartbreaking loss. The constant clash between the unified voice of the native cultures and this push to develop every inch of land on islands that have finite, physical boundaries is frustrating. … How do we keep moving forward without overdoing it? How do we keep moving forward without getting stuck in the past? Change is inevitable, true, but there should always be a way to achieve this with style, grace, and respect to where we stay.”—@djdelve

“Having bills with @flashee808 we decided all the answers to this @fluxhawaii issue are F) Go to Grama house” –@nicoleforever

PINKIE AND THUMB INFORM THE LANGUAGE OF THE ISLES.

Island locals know that the meaning of the shaka has evolved, diversified, and proliferated far beyond hang-loose territory.

But where did the gesture originally come from? Was it whalers signaling the sight of a whale fluke? Surfers tilting back beer cans? Car salesman David “Lippy” Espinda with his ofttelevised “shaka, bra!” trademark in the 1970s? Or was it thanks to a man from Lā‘ie named Hamana Kalili, who lost an index, middle, and ring finger in an accident at the Kahuku Sugar Mill in

Found in abundance throughout the islands and the standard by which all others are compared, this shaka can mean “aloha,” “mahalo,” or “right on,” with unbounded potential for additional meanings. It is often rotated from side to side for added effect. Also known as “da reglah kine shaka.” No ack, K? Shoots.

A widespread, playful shaka known to proliferate in social media images, especially selfies, this one is “liked” for its apparent increase in cuteness. It achieves the pleasing symmetry of the standard shaka, but at three-quarters the size. It’s a really cute shaka.

the 1940s and spent his days kicking kids off the North Shore sugar train so regularly that they used the shaka to signal that the coast was clear? However it was born, the now-ubiquitous shaka can convey a rainbow of meanings with just a flick of the wrist. These are some of the more common types of shakas you may encounter on an average day in the islands.

Endemic to Maui, this inverted shaka follows the basic shaka’s construction, but with less rigidity. Thumb and pinkie effectively curve upwards in a smile-like fashion, signaling increased relaxation and carefree living.

The largest shaka achievable by any individual. At twice the size of the basic shaka, all connotations are exactly doubled, thus doubling the feelings in the recipient.

Nearly imperceptible to anyone not born and raised on the Garden Isle, this shaka is, for all intents and purposes, just a waving hand angled horizontally with fingers slightly spread. The only microscopic feature distinguishing it is the minute, skyward curvature of pinkie and thumb. This shaka also reportedly appears in ultra-rural or otherwise supremely chillax regions of the islands.

This shaka may take any variation, so long as it is held up and rotated from side to side for an uncomfortably long time. Found flying solo or in groups, this shaka endures a snail-paced panning shot by KHON 2 cameramen night after night, accompanied by awkward smiles and gradually wandering eyes, and overlaid with an unending ‘ukulele outro played by island favorites Keola and Kapono Beamer.

Any variation of the shaka performed by the 44th president of the United States of America, or his kin.

This shaka reflects the simultaneously casual and stuffy aloha attire sported by Hawai‘i’s business professionals. Its telltale sign is a bonecrunchingly tight grip sometimes accompanied by light knuckle sweat. Most commonly found in Honolulu’s business district, this shaka is an old standby in corporate photo ops and legislative signings.

Although people have drawn shakas of all kinds for a very long time, this dumbed-down illustrated version seems to have been derived from the old Hang Loose surfing company logo. Occasionally sans one finger, this shaka is exploited for a variety of marketing purposes—from Mickey Mouse cartoons to local clothing companies.

The shaka that says, “Am I doing this right?” while the flash of a disposable camera goes off, illuminating a sunburnt and feebly constructed wad of curled fingers that will convey to friends back home all the pleasures enjoyed on a 10-day, Mai Tai-fueled debauchery.

Would that you may never behold this most devastating of shakas. Firm, resolute, and haunting, this stab of a shaka hits you in the gut when, for example, you speed by someone attempting to cross a busy street and then dare glance in your rear view mirror, only to find said someone throwing up a blaring gesture of sardonic mahalos. So shame!

Typically displayed fo’ da boys during beachside tailgating sessions, this loose shaka uses a low scooping technique. When demonstrating this shaka, its Heineken-suckling practitioners draw wide, lock-kneed stances and slightly tilt their chins up.

Beware: This shaka can shift directly into an uppercut punch when/if da boys feel threatened.

TIME TRAVELING HONOLULU IN JAVIER FOMBELLIDA’S BLAISDELL LIFT

At the decommissioned Blaisdell Hotel, Javier “Javi” Fombellida mans the levers of the last public hand-operated elevator in the islands. Seen from the Fort Street promenade, posted on a stool in a bird-cage-style elevator with a book in his hand, Fombellida looks like a statue.

In many ways, he recalls artist Jodi Endicott’s sculpture What’s Next, which rests a few blocks away near Bishop Street and King Street, depicting a seated man reading his newspaper, waiting for a bus that never seems to come. That sculpture was installed in 2000, the same year Fombellida became an elevator man.

“This job takes patience, a lot of patience,” Fombellida says, gesturing around

the empty lobby of the building that is now home to a hodgepodge of businesses, including a law firm, music studios, and various annexes of Hawaii Pacific University. In the first half of 2015, he reports reading between 40 and 50 books. At the age of 77, he sports a gray pencil mustache and trademark flat cap, a look that places him somewhere between the present and 1912, the year the hotel was built. While some of us mourn Honolulu’s turbulent past and others plot its auspicious future, Cubanborn Fombellida is perfectly content to go up and down, sometimes hundreds of times in a single day. He left Cuba in 1967 because, well, “Castro,” as he succinctly puts it. “He wanna kill me, I wanna kill him,” he says. So he hopscotched from Cuba to Miami to Connecticut, where he worked as a machinist for almost two decades before taking his family on a permanent vacation to Hawai‘i. Then, 15 years ago, he applied for the elevator job after seeing a listing in the local paper.

Most of the time, he serves businessmen and HPU students, but, he says, “We have crazy people every day here. Crazy people, drunk people, schizophrenics. Before, we had a psychologist on the second floor, and

people came for that. But sometimes the people are so dirty I say, ‘Take the stairs, man.’ I’m bold. That’s the way I am. That’s why I am so far away from Cuba.”

In Fombellida’s cage, he’s woven decorative lights into the ceiling bars. We step in and he puts some old jazz on his radio. “You’ve already gone back in time,” he says, then yanks on the levers, and we jerk up to the fourth floor. He pulls down on the levers, and we descend. Passing each mid-floor section in the elevator shaft exposes a different colorful mural, a blur of birds and tropical landscapes— Fombellida’s handiwork.

“One time the elevator died, well a couple times, between floors,” Fombellida recalls. “One day with a lady inside. I had to use the stool and push her out to the third floor right there.”

Suddenly, we are in a dim yellow wash of faded fluorescent lighting, the basement. There’s a rat trap set on the floor, and perched right outside the elevator door is Fombellida’s fake stuffed rat. We poke around the musty corridors. He points out an otherwise inconspicuous plumbing pipe running along the ceiling. “That’s where the old building manager hanged himself,” he mentions. Incidentally, it’s also where Fombellida rigged up a witch costume on a pulley system so that he could tow it into visitors’ faces on Halloween. But what might seem macabre to some is just mischief to pass the time for Fombellida. “Sometimes I see ... things, but I don’t believe in ghosts,” he says. “I always say it’s a shadow, or the light, or somebody’s probably there. Sometimes I want to see something, to make me a believer, you know?”

Although he’s too cynical to be haunted by the supernatural, Fombellida respects the past enough to question a time in which people no longer talk to each other in elevators. “Everybody looks down,” he laments. And yet, Fombellida is contemporary enough to own a smartphone. He uses it to stay connected with people he meets through his work. “They tell me, ‘I’m going to be married,’ ‘I have a baby,’ ‘I miss you, Javi.’ I love that.” He takes his phone out of its holster and holds it up, explaining that there are three generations represented here. “Three steps—the elevator, me, and this phone. I’m right in the middle.”

“It’s like a Polaroid when you’re waiting to get the image to come out. The first time I did indigo, I felt like I was dreaming,” says Donna

Miyashiro, who tends to a vat of Hawaiian indigo dye at Lana Lane Studios in Kaka‘ako.IMAGE BY JONAS MAON

Both as a plant and in the dye vat, indigo takes on a life of its own. “I remember one night when [the plants] were kind of big, I went to look out and I thought I killed them. But they actually sleep at night,” says Donna Miyashiro, a tiny woman from ‘Aiea with enough humble exuberance to fill the narrow dye room of Hawaiian Blue, located in Lana Lane Studios in Kaka‘ako. Miyashiro grows the Hawaiian indigo that she and founder Tokunari Fujibayashi use to dye her sewn creations and other items like stained shirts or toe socks—anything they can get their hands on, really—in the courtyard of her home. Her dog likes to take morning naps in the shade of the indigo leaves.

Known for producing the deep hue of a twilight sky or workman denim, indigo can also make for the washed-out blue of faded jeans or the shoreline of Lanikai, depending on the vat and the amount of times a garment is dipped into it. For Miyashiro and Fujibayashi, these lighter shades are a chance to reflect the gradients of the Pacific Ocean. “It’s such a cool process because when we dip, it comes out like a light yellow or beige and the oxidation brings out the color,” Miyashiro says. “It’s almost like a Polaroid when you’re waiting to get the image to come out. The first time I did indigo, I felt like I was dreaming.”

Standing next to her is Fujibayashi, a tall, lean man whose enthusiasm takes a different form, expressed in heartfelt but brief statements and an insistence that you experience the process yourself. The 12th generation of a Japanese textile-designing family, he began weaving and dyeing under his father’s tutelage in fourth grade, and now teaches workshops at the University of Hawai‘i, where he researches Hawaiian

indigo, or Indigofera suffruticosa (which is different than Japanese indigo, Polygonum tinctorium) and medicinal crops. “We’re seeking dyes better for the people’s skin,” he explains, contrasting these with chemicaland oil-based dyes now predominately used for black and blue garment colors. Natural indigo, he says, has antibacterial benefits, and turmeric is good for the liver. One of Hawaiian Blue’s products is a kitchen towel that Miyashiro sews from linen, which also has antibacterial properties, that they dip-dye a light, ocean-hued blue.

In the Hawaiian Blue dye room, jars of dried indigo paste occupy shelf space alongside a stained-blue door. A bag of shriveled turmeric root rests on a ledge lining the rear wall. In a far corner, indigo fermenting in a plastic trashcan awaits its next feeding of sake (Japanese rice wine) and honey. “The indigo is considered a living being and needs to be fed,” Miyashiro explains. “The sake helps facilitate fermentation.” To get to this point, Miyashiro, under Fujibiyashi’s guidance, waited for the perfect time to cut fresh indigo leaves, which she then soaked, sifted, skimmed, reduced to a paste, and mixed with water infused with wood ash to control alkalinity.

Just like every vat before it, this round of indigo will be eagerly and tenderly cared for until it is ready to offer up its unique blue. Appropriately, each gets its own name. “We start off with ai because Tokunari is from Japan and ai is the word for blue,” says Miyashiro. “This vat’s name is Aimi, which means beautiful blue.”

Hawaiian Blue products are available at Fishcake, located in Honolulu at 307 Kamani St.

“Vinyl helps ensure that this music will be heard decades from now,” says Roger Bong, whose Aloha Got Soul record label and blog reintroduces listeners to Hawaiian funk from the ’70s and ’80s.

“Vinyl helps ensure that this music will be heard decades from now,” says Roger Bong, whose Aloha Got Soul record label and blog reintroduces listeners to Hawaiian funk from the ’70s and ’80s.

FLUX FILES

When Roger Bong discovered DJ Muro’s Hawaiian Breaks digital album in 2010 featuring ’70s disco and funk music from a variety of Hawai‘i artists, he was instantly hooked. Some of the songs he recognized, but others were completely unknown. Muro was somewhat of a mystery himself, known as one of the “Kings of Diggin’” in the record-collecting world. His specialty was hip-hop, but his collection spanned all music, including an incredible assortment of ’70s Hawaiian funk that Muro compiled in a mixed album.

Bong set out to recreate the track list for the album, identifying individual song titles and artists for those, including himself, who may have stumbled upon the hour-long mix and were curious about who sang what. “It became this scavenger hunt I found myself on, along with a handful of other like-minded individuals who were looking to identify the songs,” says Bong, who, after a year of researching, listed his findings online in a new blog he called Aloha Got Soul. The website became a repository of sorts for other albums that Bong uncovered.

For Bong, who had a passion for music and writing, this new project was the perfect fit. At the time, Bong had just graduated from the University of Oregon with a bachelor’s degree in journalism. In high school at Mililani, he played guitar and drums, even writing a handful of original songs for a few indie bands he played in. Then one day, a friend brought his auntie’s record collection to Bong’s house to listen for samples to loop. Bong started buying records to sample, then ones that he simply enjoyed: soul, jazz, funk, R&B. “Four years later, when I first heard the Muro mix, it was a perfect combination of two things I loved: soulful music and Hawai‘i,” he recalls.

Today on the site, Bong continues sharing relatively unknown ’70s and ’80s Hawaiian soul, groove, and funk music from his expanding collection. He also features interviews with old-school local musicians like Steve Maii (who composed the 1983 song “Catching A Wave”), Robin Kimura (of the ’70s funk band Greenwood), and Norm Winter (of Radio Free Hawaii).

Five years in, Aloha Got Soul became more than a blog when Bong decided that rather than just write about great vinyl, he would make some himself. He reached out to fellow musician Mike Lundy, who had sung two of the tracks on Hawaiian Breaks. Bong had interviewed Lundy as part of a story for the blog in 2013, and reconnected with him about reissuing two of Lundy’s singles from The Rhythm of Life LP on 7-inch vinyl under the Aloha Got Soul record label—35 years after their original release. The two-song vinyl debuted earlier this year to fanfare at release parties in Honolulu, London, and Chicago. Collectors ranging from vinyl enthusiasts frequenting Hungry Ear Records in Mo‘ili‘ili to teenagers in London’s Peckham neighborhood scooped up copies from the limited run of 500. “Rog, I can’t believe this,” Bong recalls an incredulous Lundy telling him at the event. “We never had a release party back in 1980 when the LP came out. But now it’s official.” Buyers from places including Japan, Spain, France, Brazil, Taiwan, China, and Canada—where Bong says fans had heard about the music through Aloha Got Soul or through other sources—ordered the vinyl online. “It’s like the music is getting a second chance,” he says. In November, he plans to release all nine songs from Lundy’s The Rhythm of Life

“Vinyl helps ensure that this music will be heard decades from now,” Bong explains. “It is literally a record of something, a physical document archiving a piece of sound … To listen, all you need is a needle to the groove.”

For more information, visit alohagotsoul.com.

The Makiki Community Library, fueled by the “spirit of rebellion found in its founding political figures,” according to director Harold Burger, lives on as the only volunteer-run library in the state.

The Makiki Community Library, fueled by the “spirit of rebellion found in its founding political figures,” according to director Harold Burger, lives on as the only volunteer-run library in the state.

DESPITE DECADES OF UPS AND DOWNS, HAWAI‘I’S ONLY VOLUNTEER-RUN LIBRARY REMAINS A FIXTURE IN MAKIKI.TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ

IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

In 1976, during his second term as mayor of Honolulu, Frank F. Fasi and Assemblyman Neil Abercrombie, who represented MakikiMānoa, saw their dream for a public library set on the grounds of the Makiki District Park become a reality. Today, the “People’s Library,” as it’s called, is a community icon. The all-white concrete exterior shimmers in the sunlight like a beacon of hope, fueled by the “spirit of rebellion found in our founding political figures,” says Harold Burger, the director of the Makiki Community Library, who sits on the nine-person board that manages the space.

The tract of land that the library now shares was originally the site of the Experiment Station of the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association, which opened in 1895. It operated as a research center until the 1970s, when the land was turned over to the City and County of Honolulu to be developed into Makiki District Park. Determined to meet the needs of the budding district, Fasi committed resources to repurpose the Sugar Planters’ Association’s administrative building as an independent, city-sponsored library for the community, to be run by the Friends of Makiki Library. Two stories high, with partitions rendered in wood and concrete, it now houses a collection of more than 30,000 donated books ranging from mass-market paperbacks to children’s collections to rare first-edition finds. Today, the library is a platform for community outreach, holding monthly events like family movie nights, astronomy viewings, poetry slams, and workshops on civic processes. It remains the only volunteer-run library in the islands and is open just three days of the week—unlike staterun libraries, which are open five or six days a week and have paid employees. It endures on a minimal budget of about $1,000 a month afforded by donations and grants.

Because of its unique standing as an onagain off-again city-funded library, the location has had its ups and downs over the decades. While Fasi was in office, it was a welcomed addition to the neighborhood and a resource well used by curious residents looking to satiate their appetites for knowledge or for quiet study areas. But after Fasi completed his term and Abercrombie, who was elected to state congress, headed to Washington D.C., the library fell into the hands of the state and was severely mismanaged, according to Burger.

Despite the community’s request for the library to become an integrated part of the state library system, political disagreements resulted in the building being transferred back to the purview of the City and County Department of Parks and Recreation.

In 1996, the library closed due to a lack of funding required to bring it up to code, and it remained off-limits to the public for three years. Abercrombie, meanwhile, secured a $100,000 congressional appropriation for renovations of the building, including an upgraded electrical system, new windows, a fire escape, an elevator, and a special needs lift for the mezzanine, and in 1999, its doors were again opened to the community. But the library’s woes were far from over. In 2007, city funds dried up once more. The library sat closed for a year, its books sold off or given to other libraries, until Mayor Mufi Hannemann returned the renovated library to the Friends of Makiki Library (now called Friends of Makiki Community Library). Since reopening in 2009, thanks to volunteer staff and donations, the library has rebuilt its collection and issued nearly 2,000 free library cards. “We have 150 people who come in regularly, and schools in the area come in periodically to clean the place,” Burger says.

The movement to fortify and incorporate the neighborhood’s only library has gained broad momentum since its reopening. In 2013, the state dedicated $250,000 to study the feasibility of a new building for an official public library for the district. Old Makiki, with its 1960s-era cinderblock walk-up apartments, churches, and storefronts, is transitioning into a new Makiki, with highend commercial properties and brilliant restoration projects like the updated Kewalo Apartment Buildings. In the midst of it all, as the densely populated neighborhood continues to grow, Makiki’s library will remain a platform for community outreach and wherewithal. “It’s the spirit of volunteerism here in Hawai‘i that has made this work this long,” Burger says. “We have a number of people that spend their time, energy, and money to make sure this area doesn’t suffer from lack of opportunity.”

Makiki Community Library is located at 1527 Keeaumoku St. For more information, visit makiki.info/makiki-community-library.

Surfing is what started it all for Guy Hagi, whose Town and Country surf reports updated surfers on water and weather conditions.

Surfing is what started it all for Guy Hagi, whose Town and Country surf reports updated surfers on water and weather conditions.

WHAT IS IT LIKE TO TELL THE FORECAST IN A PLACE WITH THE BEST WEATHER ON THE PLANET? GUY HAGI HAS THE STORY.

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOKTwenty years ago, Guy Hagi promised himself he would never tell a lie. It was advice the young weatherman received from legendary sportscaster Jim Leahey upon the start of what would become a career as one of Hawai‘i’s most beloved and bedeviled weather reporters.

“The two most important things you can do is be yourself, because you cannot be anybody else,” Hagi recalls Leahey telling him, “and don’t tell a lie, because a lie will always come back and bite you in the ass.”

It’s ironic, then, that it was precisely a “lie” that made Hagi a household name—or at least a trending one—across the country as two potential hurricanes, Iselle and Julio, bowled toward the Hawaiian Islands in April 2014. Hagi was out of the country

on a family vacation and wasn’t reporting on the movements, and yet, social media put the weatherman on blast, poking fun at Hagi for sometimes getting it wrong, as happens when trying to predict something as unpredictable as the weather. More than 2,000 variations of memes tagged #liehagi paired previously aired screenshots of Hagi with funny captions. “You fakaz I not lying this time,” went one of the most popular. A Huffington Post article described Hagi as “having the worst day ever.”

The jovial weatherman who is known for peppering his reports with colorful commentary in the occasional Pidgin has become so top of mind that when people in Hawai‘i think about the weather, they immediately think: Guy Hagi. And it turns out that Hagi’s persona IRL (Internet speak for “in real life”) is practically the same as his onscreen one. “But I gotta tell you, I don’t swear nearly as much as all those memes say I do,” he jokes. Whether he’s talking about scattered showers over Kaua‘i or a beautiful 80-degree week, Hagi gives the weather report with a wide-eyed enthusiasm. While forecasting a large swell about to hit O‘ahu’s south shore, he can seem practically giddy—which makes perfect sense upon realizing that this sport is

what sparked his career as a weatherman. At 13 years old, Hagi began making the 4-mile trek from Liliha, where he grew up, to surf at Kewalo Basin. “The bad part is that there were no forecasts back then,” he recalls. “We walked down to the beach at the crack of dawn—flat. Or too big, one or the other.” In high school, Hagi’s father came to the rescue when he began driving him and his two brothers down to Ala Moana Beach Park each day after school— this despite working a grueling job at the oil refinery out in Campbell Industrial Park. “He didn’t surf,” Hagi says of his father. “He would either hit the tennis ball against the wall or walk around the park. He just was dedicated to the kids, going, ‘Eh, my kids like doing this, I going do this with them.’”

After graduating from McKinley High School in 1978, Hagi began working as a sales clerk at Town and Country Surf. A few months later, local radio stations looking perhaps to capitalize on the booming surf industry, decided to air surf reports, and Hagi was tapped for the job—mostly, he says, because he was the only one willing to wake up early enough to call in the report at 7 o’clock in the morning. “It was very rudimentary at the time,” recalls Hagi, who was one of two guys giving reports. “I had

Hawai‘i’s most beloved and bedeviled weather reporter in the state shown at the Hawaii News Now station where he prepares for his evening forecasts.

observers around all points of the island, and I’d call ’em up at 6:30 a.m., compile a report, and then do an update at noon.”

Even after he left Town and Country in 1982 for a sales position with ocean sports company Water Bound, Hagi continued calling in his reports—in total, he was the radio voice of surf for nearly 20 years. Listeners tuned in to KKUA and KQMQ would hear, on the hour, “This is Guy Hagi with the Town and Country surf report.”

When a weather reporter position opened up at KITV in 1994, the name that came up was one they’d heard on the radio for all those years—Guy Hagi. While he wasn’t a standard candidate, lacking TV experience as well as a degree in meteorology or journalism, Hagi’s star quality was on the rise amongst the local surf community. He had also been studying weather patterns for years to expand his surf reports. Hagi accepted the job at KITV and began diligently preparing for the position,

reading Weather in Hawaiian Waters by then-state climatologist Paul Haraguchi and following forecast discussions from the National Weather Service. After a couple months of preparation and before he could go on air, Dan Cooke at KHNL approached him to cover the weather for a new two-hour morning show alongside anchor Lee Cataluna. He bit. “It was good because nobody was watching,” he says. “I had two hours of practice every day.”

Seven years later, in 2001, Hagi moved to KGMB (today called Hawaii News Now, a shared service between KHNL, KFVE, and KGMB), where he has served as the resident weatherman ever since.

Today, before he checks in at the newsroom at 2 p.m., Hagi takes care of domestic duties like prepping dinner, which he does nearly five days a week, or taking his daughter’s cracked iPhone screen to get fixed. His family is comprised of his wife Kim Gennaula, the veteran journalist

who anchored KGMB’s weeknight spots for 15 years before becoming the executive director of advancement at ‘Iolani School, and their two children Alia, 12, and Luke, 11. Like his father, Hagi emphasizes the importance of spending time with his family, returning home to Kaimukī five days a week after his afternoon news brief to sit down for dinner with Gennaula and the kids, then returning to the station at 8 p.m. to prepare for the taping of the evening news.

In the newsroom, which is in Kalihi, Hagi’s station is walled off from the rest of the 100-person news staff, who have huddled open cubicles. It isn’t by design, but Hagi is grateful for the physical barrier, a symbolic extension of the personal separation he puts between himself and the news desk. Ask Hagi what the day’s top story is, and he can’t tell you. “Maybe it’s a defense mechanism I put up,” says Hagi, who gives his weather briefing to the rest of the news

team, then leaves without hearing what else will air that night. It’s an outlook shaped in part by an instance in 1999, when the story on the mass shooting at Xerox broke. Hagi, who was doing weather, was the only other reporter alongside anchor Lyle Galdeira on the desk during KHNL’s morning show. “Lyle grabbed a cameraman and went chasing the story, which was evolving throughout the morning,” Hagi recalls. “It’s just me and Lyle, so I gotta go on the desk and report what Lyle’s telling me and inform the public of what’s going on.”

The experience dampened Hagi’s upbeat spirit and stuck with him for a long time afterward. “News people get calloused by [the news], shaped by it, and it changes your outlook on everything,” he says. Today, the running joke at the newsroom is a lineup that frequently follows: death, murder, Hagi. “We’re going to dig this hole, and Guy, you gotta bring us out,” he says of what his news colleagues such as Stephanie Lum or Keahi Tucker might say. “Because nine times out of ten, what am I talking about? Best weather on the planet.”

The 10 percent of bad weather that does come is often in the form of tsunamis or hurricanes. News being what it is, Hagi acknowledges that some sensationalism may go into coverage of extreme weather conditions. For his part, Hagi plays down the severity until the National Weather Service tells him otherwise. “A hurricane is like a zombie. If you get killed by a zombie, that’s your fault—the thing is walking two feet every second. A hurricane is the same way. We got a forecast tracker five days out, and that forecast track adjusts as it gets closer.”

The National Weather Service, which Hagi uses exclusively to prepare his forecasts, is able to track large storms and swells with relative accuracy—when they’ll hit and how strong they’ll be—but the smaller showers and wave conditions are harder to predict. Hagi keeps tabs on how many times they get weather predictions right, which he estimates is about 75 percent. But no one remembers when someone is right, and as the proverbial messenger of the National Weather Service, Hagi is the one who gets killed when forecasts go south—he hears about it everywhere, from the grocery store checkout line when he’s buying bread (“You

know, it rained, and you said it wasn’t going rain!” says Hagi in a screechy voice while scrunching his nose) to, of course, online.

Despite his attempts to stay shielded from deflating news, Hagi says it is becoming harder to do. “Remember that show in the ’50s, Happy Days … where the kids would do all kine crazy stuff like eating goldfish?” Hagi asks contemplatively. “One of the stunts they used to do was to try and pack the most amount of kids into a car. But no matter how they squirmed around, there’d be a finite amount of kids that can fit into the car. This island is akin to that. We’re getting to the point where we’re putting too many people on this island, too many cars, too many houses, too many roads … the burgeoning growth of this place scares me.”

With all the changes Hawai‘i is facing, then, it feels safe to take jabs at the one constant: the weather. “The value of the weather in the newscast is it affects everybody,” Hagi says. “You can’t say that about every story in the news, but everything in weather applies to every single person.” So when Hagi gets it wrong, it’s easy to blame him, to string him up for bringing rains to our weddings or tropical storms to our first birthday luaus, as if he is some mythic being, a conjurer of storms and passing showers. But, Hagi explains, “The nature of weather and the science of forecasting is such that it’s impossible to get a forecast right 100 percent of the time, because we’re talking about a living, breathing thing that changes, and every subtle change will affect the outcome.” He likens predicting the weather to forecasting a football game. Can the football forecaster ever pinpoint the game’s final score? Probably not. “But today,” says Hagi, looking up to clear, blue skies, “we hit the nail on the head.”

Valets and doormen usher visitors and locals alike into paradise. Gerard

has been greeting customers at The

a

Collection

for 27 years. A great doorman, he says, “tries to understand what guests are going through and anticipate their needs before they even ask.”

Thomas Royal Hawaiian, Luxury Resort,

WHAT IT MEANS TO BE A GREAT VALET IN A STATE THAT CELEBRATES ALOHA HOSPITALITY.

TEXT BY BEAU FLEMISTER | IMAGES BY JONAS MAONIt’s not just about the tip. … Fine, it’s a little bit about the tip. We’re workin’ over here! But it’s not just that. What are we, waiters, or something? Plus, this is Hawai‘i, and our culture is one that prides itself on treating one another with respect. With courtesy. With decency. With aloha. Most of us in Hawai‘i have worked in the service or hospitality industry, and what’s that Golden Rule? Well, a good valet treats your car like you’d want to be treated; a great valet treats you like you’d want to be treated.

I was a valet parker in Hawai‘i on and off from ages 18 to 28. Full time, really, from 24 to 28. I worked for a local company contracted by a number of O‘ahu hotels, restaurants, private parties, events, shopping centers, and hospitals. I worked everywhere from the Ilikai to the Outrigger Reef to the New Otani to the Trump Hotel to Morton’s Steakhouse. Usually, valets are parking for just-off-the-jet tourists at hotels, local people at restaurants, and rich residents at private parties (say, a politician’s fundraiser in Mānoa or a privateschool grad party around Diamond Head).

Often, at least in regards to tourists visiting Hawai‘i, valets are the first face beyond those in the sea of arrivals that they see—the first sweet (or bitter) encounter of a local person that sets the pace of their entire experience that follows. Whether it be the Hilton, the Marriott, the Royal Hawaiian, the Outrigger Waikiki, when we open up that car door, we’re all smiles, albeit a little sweaty from having run up and down that garage ramp for the last eight hours. Our “Aloha, and welcome to the [insert hotel here],” is the first “aloha” a visitor might hear. Clearly, hotel owner and tycoon J.W. Marriott knows that first impressions are everything, because we do.

Believe it or not, the gig is more lucrative than you’d think. Indeed, it is a minimum-wage, base-pay job, but haven’t you ever wondered how a valet can pull in over $60K a year? Tips, of course. But again, it’s not just about the tips. Sure, we can look a little rough around the edges at times, but don’t let the bad press fool you. Valets aren’t all like those two greaseballs from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. The stories about valets copying your house key while you’re out to dinner, then burglarizing your home a week later? Well that’s just Fox News fear-mongering—classic “A Dingo Ate My Baby” tales.

A good valet is courteous; a great valet is an Oscar-worthy actor. No matter what the hell is going on in the garage below—a pileup of 40 rental cars, a Porsche T-boned by a Benz—the place where the client pulls up is known as “The Show.” This front lobby or entrance is a valet’s Broadway, with an equally hard-to-please audience: hotel guests arriving after hours-long flights and 45-minute drives through traffic, followed by the maze of eternally under construction Waikīkī, plus two kids in tow. All this hassle, before they pull up to those “Valet Parking Only” signs. Needless to say, they can be pretty damn perturbed.

But we, the valets, must put their cares at ease. We must quell their concerns. We must open up those rental car doors and usher them out not only onto their pre-booked hotel grounds but also into their entire Hawai‘i vacation experience. We open those rental car doors and welcome them into their idea of paradise. Thus, with the most sincere, warm-hearted, teeth-twinkling smiles, coupled with the tender surety of a Morgan Freeman voice-over, we greet them, “Aaaaa-loha, guys, welcome to the [insert hotel here]. So glad you could make it! Now let’s get unpacked and into that room so you can unwind, shall we?” Oh, we shall. Because a good valet makes you feel like your car is in good hands; a great valet makes you feel at home.

Of course, we can’t take all of the credit. There are a couple other key players in Hawai‘i within the hospitality business that can leave a mark as indelible as ours. The airport shuttle driver is one. The doorman is another. A good shuttle driver gets riders from point A to point B; a great shuttle driver is a historian with a wealth of knowledge, or a comedian showcasing his 40-minute set. The

is the owner of Prestige Valet Service, which has provided valets at local functions, private events, nightclubs, and restaurants since 1998. With nine permanent valet stands and 30 employees, Henson knows a thing or two about what makes a good valet: “Good customer service, a concern for people, and of course, a clean driving abstract.”

Chad Fujimoto has been working as a valet at Halekulani for eight years. Previously, he was a valet for nightclubs and private events, but of Halekulani, he says, “Every day is a memory. I don’t consider it work.”

doorman—the gentleman at the hotel who tags baggage upon arrival, gives said bags to the bellmen, then points guests toward reception—can actually flex his charm a little more intimately than us valets. The doorman has repeat clients, guests and families he sees year after year; guests he watches grow, and guests he grows with. I’ve even seen a particular doorman at a local hotel keep a pocket journal with details about returning clientele, from ages of their children to their favorite cocktails at the pool bar. And where a good doorman says hello; a great doorman asks you how Grandma Ethel’s hip-replacement surgery went last May.

A valet’s relationship with the local community, however—specifically at nightclubs, restaurants, events, and private parties—is a different beast entirely. Sure, there’s an act, but the scene is altered. And there is always that pervading question of space. As in, “Wat, get space?”

Because the thing about space is that there’s always space. Space is an ambiguous noun that appears and grows exponentially with gratuity and demand. It’s science, or complex mathematics, and also a ruse. Regardless, a good valet fits another car in; a

great valet puts it “up front.” Up front is the V.I.P. zone where we flaunt a client’s status and, in the process, make our operation look ballin’. What makes a valet an exceptional valet is how he can render said space by judging a driver’s sense of urgency or deeper sense of character.

I mean, the sign says, “Lot Full,” right?

A few freebies on how to manifest space for your ride when the “Lot Full” sign is posted: 1) Be of the opposite sex, with eyes that flirt and plead. 2) Know any one person from the valet company, then say he’s your cousin. For instance, “Is my cousin Ikaika working today?” Ikaika is a good valet name to bank on in Hawai‘i. It’s like New York pizza shop owners named Tony or mainland congressmen named John. 3) Be an auntie or uncle, as in, 50-plus, male or female, but preferably female so we can say, “Auntie, we going take care you.” We love saying that. 4) Have an expensive car that we can put up front. No, not a new Prius. Like a new Benz or a Tesla. 5) Flash that green when you drop your car off, not after. Even if said car is a dinged-up Toyota Corolla, you’re guaranteed a place in our hearts and a spot on our lot.

Which brings up a very good question:

What’s a good tip? Well, what’s the most you’re willing to part with? Now double that. Just sayin’. Seriously, though, when it comes down to it, this is at the core of our service: Doesn’t everyone deserve a little luxury? Doesn’t everyone deserve to be a little fabulous now and then? Greeted, schmoozed, helped out of their car like they are, well, somebody? ‘Cause aren’t we all somebodys? And every somebody deserves a little added class, and class is what valets give the world. Class is the first thing a venue or hotel wants you to see. We are Donald Trump’s and J.W. Marriott’s and Alan Wong’s first-date face, all dolled up, hair-did, winking you into paradise. Just make sure to stamp your ticket at the door, and remember, the first three hours are validated.

Because a good valet knows it’s more than the transaction—more than the act of parking a car, even if we are highly trained technicians with Ph.Ds in applied reverse parking. At the end of the night, a good valet brings your car back intact; a great valet leaves a sweet taste in your mouth and has you sleeping easy that night.

It’s not just about the tip. But you know, if you feel inclined and the service was stellar…

$35 each

Sound System $250 Leg Drapes $20 each Banquet TablesChandelier

$125 each

IN HAWAI‘I, ONE OF THE MOST POPULAR DESTINATION WEDDING LOCALES IN THE WORLD, MATRIMONY IS BIG BUSINESS.

Table Linens

$20 each

$10 each

Marquee Tent $450 each

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGES COURTESY OF JOHN HOOK & SPROUT BY ARIA STUDIOS ChairsTwice a year, in October and April, the Blaisdell Center exhibition hall in Honolulu is filled to capacity with vendors and shoppers looking to procure wedding services. If you identify yourself as a bride or groom at the entrance, you receive a cute heart sticker and can leave with enough swag to fill a shopping cart.

There are brochures for things you wouldn’t even think of: the chocolate fountain guy, the chair ribbon guy, the florist who specializes in sustainably harvested moss, the Christian hip-hop DJ crew. Photographers have displays with tourist couples kissing across the range of human experience: at churches and hotel courtyards, beach parks, nightclubs, shark cages; while skydiving or ziplining—whenever and wherever a licensed practitioner is willing to show up. Hawai‘i is one of the most popular places in the world to get married. Weddings here are what entertainment is to Los Angeles, finance is to New York City, oil is to Dubai. It is our ordinary workers’ bread and butter, our fish and poi, and everybody knows somebody who works in the variety of secondary industries which weddings supports. For those of us who don’t work directly in the industry, even those of us who do, all this talk of romance is enough to drive a sane person crazy. According to the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority, in 2013, more than 125,000 individuals indicated that the purpose of their visit to the islands was to get married, and more than 580,000 came for their honeymoons. They come from around the world, but primarily the U.S. mainland and Japan. Of Japanese tourists, nearly 20 percent come specifically to get married, and leave in a hurry. There are certainly other gorgeous locales to do the deed, so why Hawai‘i? It could be biological:

An anthropologist might say human couples arrive on the islands for the same reasons as migrating humpback whales, green sea turtles, and tiger sharks: to court and have sex. A yogi mystic might tell you this place is some version of a portal. Of course it’s not one reason but many. Hawai‘i has been in the wedding business for decades, and as the ladies passing out stickers at the Blaisdell might tell you, business is booming.

On a trip to the beach in Hawai‘i, you might be lucky enough to spot a monk seal, a turtle, or even a whale. More likely, you will see Japanese newlyweds. In 1973, Takao Watabe, a Japanese merchant, opened a wedding store on the ninth floor of the Waikiki Business Plaza. He was one of the first to sell wedding packages for Japanese nationals in what would become a widespread phenomenon. The afternoon I visit, I experience what as many as 50 Japanese couples a day do on the eve of their wedding date: After finding the elevator through a gaggle of visitors, cops, and guys hawking shooting range flyers, I ascend to the ninth floor and the Watabe briefing area. When the elevator opens, it smells like fresh flowers, and I float through the immaculately lit, open salon of Watabe Wedding. Tomoko Bohannon and Bella Sato from the planning department greet me. In addition to planners, Watabe has employees who work as in-house salon attendants, beauticians, florists, media correspondents, cooks, bartenders, chapel administrators, drivers, photographers, videographers, and then some. After a tour of the space, I take a seat where a groom might while waiting for his bride’s fitting.

“Hawai‘i for Japanese is their dream wedding,” Bohannon tells me. “For many of them, it’s their first trip out of the country. And if they want an international wedding, it’s usually here.” As is the custom in many cultures, a Japanese couple’s wedding invitation list may extend into the triple digits back in Japan, with a corresponding event that costs as much as a downpayment on a home, a vehicle, the first few years of raising a child. “It’s cheaper to just go with us,” Sato says. “Sometimes it’s just the couple. Mostly the party is about 10, their parents, a few friends.” They often combine the honeymoon and the ceremony. The

average stay is five to six days in Waikīkī, usually at the Moana Surfrider, or at Aulani on the west side of O‘ahu. If you head to the carport of the Moana Surfrider at precisely 10 a.m., there are often half a dozen brides awaiting their rides to the chapel. A Watabe staffer picks the couple up, and their precisely timed day, from photos to ceremony to party, begins. It’s a dash across the island: After in-room prep, the couple marries at a chapel, has their ceremony and reception, then hits the beaches and parks for the photo package.

“Unfortunately we can’t take too much time with each couple,” Sato says. Local government could learn much from Watabe’s efficiency: they handle more than 1,000 couples per month during the busy seasons. Watabe’s photo package starts at $700, though most couples pay for the standard set, which goes for around $8,000, not including hotel and flights. Watabe’s three chapels in Ko Olina operate like wellmanaged train stations. Sato and Bohannon laugh while mimicking the shoulderstrapped walkie-talkie correspondence their planners do every day. “There are codes for a bride going to the bathroom as another is headed toward the chapel,” says Sato, who explains their techniques to ensure the brides don’t see each other and that every couple has their special, private moment.

The majority of Watabe’s customers come from Japan, with a small percentage from the mainland and the emerging markets of China and Korea. In addition to dozens of offices throughout Japan, Watabe maintains locations in Las Vegas, Paris, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Bali, and Florence— all actively selling Hawai‘i as a destination for romance. Unlike Americans, who plan much of the ceremony themselves, Watabe’s Japanese customers are perfectly happy with receiving exactly what the brochure and wedding package lays out. “If they’re getting the photo package at Kualoa Ranch, they want a picture with the bride on the horse,” Bohannon says. “But we have to tell them that it’s just a promotional picture—the horse is scared of the dress.”

Marriage, and the weddings which demarcate them, are social constructions not universally common to humanity. For

Hawai‘i has been in the wedding business for decades, and business is booming: In 2013, more than 125,000 individuals indicated that the purpose of their visit to the islands was to get married, and more than 580,000 came for their honeymoons.

Weddings can be ridiculous affairs, often as improbable and foolish as the love that inspires them. But that never stopped anyone before. People will continue to come to Hawai‘i to fall in love, marry, and embarrass themselves.

many cultures, a wedding and the party that accompanies it is a cogent example of generational cultural transmutation and how we pass on our ideologies and customs. In 1958, acclaimed scholar, educator, dancer, and composer Mary Kawena Pukui co-authored a book titled The Polynesian Family System in Ka‘u Hawai‘i, an attempt to transcribe and preserve the memories of hundreds of years of familial experience. “Amongst commoners there were no formalities. When a lad saw a maiden that he wanted for his wife, he spoke of it to his parents or grandparents,” the book reads. If all was kosher, “the young man simply came to her home to live with her, becoming one of the household.” For the elite, there was always an event. “If the period of ho‘opalau (betrothal) lasted a long time, the young man sent gifts every now and then to his wife-to-be, perhaps a pig, a catch of fish, chickens, a feather lei or a fat dog. A kahuna (priest) prayed that the union be fruitful. In his prayer occurs the phrase: ‘E uhi ia olua i ke kapa ho‘okahi,’ or ‘You both shall (forever) share the same kapa.’ Fast forward to the present, and there are some problems with the contemporary construct of romantic union, besides the whole finding somebody part. Midcentury feminists argued that it was a suffocating morass tying women to economic dependence and stifling identity. Irina Dunn’s famous quote, that “a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle” remains true, and has been proven in Hawai‘i by countless women who swim like fish and are quite adept with gears. But it’s the institution of legal union that still warrants critique, not the personal

decisions. Marriage in Hawai‘i is the culmination of a tourism- and militarybased economy, a celebration of settler colonialism, conspicuous consumption, and the continued misappropriation of Hawaiian culture for outsiders. Marriage is also a positive and powerful economic force. These discussions remain valid. One thing that came of the discussions of same-sex marriage in recent years is that (surprise!) everybody likes weddings. Patriarchy and inequality can go, but weddings, with all the joy they bring, can definitely stay.

Though technology has forever altered young people’s landscape of human interactions, and dating is weirder than ever, the vast majority of us dream of getting hitched. In Hawai‘i, it is now easier than ever: It is possible to elope at lunch with two bus passes and a $100 bill, and return by dinner legally married. (In Hawai‘i, a marriage license, the document necessary prior to a ceremony by a sanctioned individual, costs $60, plus a $5 online service charge).

Local weddings defy categorization. If you live in Hawai‘i in your 20s and 30s, chances are you’ll gain experience as a caterer, performer, crasher, and sometimes guest in the industry. There are innumerable ethnically specific behaviors at receptions: Many local Japanese wedding guests defer attendance of the ceremony to party at the reception; historically, Shinto weddings were for families only, and Buddhist weddings, something of a recent phenomenon, were usually just for the couple.

But regardless of the constraints a couple’s culture might impose, local style has them doing what they like.

I have seen a Filipino wedding with a kung fu troupe performing as a dancing lion, a Japanese wedding with a full Tahitian dance revue, a haole wedding with 1,001 Okinawan paper tsuru (cranes) hanging over a wedding cake, and a Hawaiian wedding with the bride wearing cowboy boots and grandmas dancing to the raunchiest hiphop. My favorite customs involve raining dollar bills. Gratefully, the unsanitary Filipino practice of putting folded bills into the bride’s clenched teeth has been replaced by pinning them to her veil or the groom’s barong (shirt). At Samoan and Tongan receptions, a taualuga is performed by the bride in which family members dance and toss small fortunes in the air. If you wait for it, there’s always an auntie who holds a child with one hand and tosses a wad of loose bills right at the bride’s head with the other, the wad exploding in a cascading flurry.

Hollywood never seems to get it right. Hawai‘i remains the tropical backdrop of outsiders’ fantasies dating back to the 1940s.The iconic wedding scene from Blue Hawaii, the Elvis Presley musical from 1961 filmed at the long-since defunct Coco Palms hotel on Kaua‘i, has passed through the generations via cultural osmosis. It’s a doozy of technicolor corniness: Elvis, clad in all white with a red sash and carnation lei, stands regal while being paddled to the shore by shirtless local guys on a double-hulled canoe. He disembarks, takes his bride’s hand (Joan Blackman, playing his Hawaiian love interest named Maile), croons, “This is the moment,” as the music swells, and is paddled

to the opposite shore, all while a gaggle of tutus in mu‘umu‘us follows along the banks of the canal singing the chorus.

“We did something like that recently,” says Bill Hedgepeth, the director of catering and event management for Starwood Resorts of Waikiki, which includes The Royal Hawaiian in addition to its neighbors, the Sheraton Waikiki and the Moana Surfrider. “An Indian couple wanted to get paddled to shore, as if they were on an elephant,” he explains. “We made it happen and coned off the beach so they could make their procession.”

Remodeled in 2008, the Royal Hawaiian, with its iconic pink art deco architecture, has become the deluxe destination of local weddings. “Many of our couples were raised here and left, had careers in big cities, and came back to get married,” Hedgepeth says. The experience does not come cheap: the price for a wedding here starts at $140 per head with a minimum headcount, not including the space rental. As I’m given a tour, Hedgepeth pulls aside one of his colleagues who is supervising

the setup of chairs on the hotel’s ocean lawn, with a view of Diamond Head and the break at Pops. “I’ve got a bride in the King Kamehameha suite,” he tells him. “She wants to toss her bouquet from the balcony to the crowd below. Let’s set that up tomorrow.” Dream wedding stuff.

“Anything they ask for we can accomplish,” Hedgepeth says. “This is an open and public hotel, and the receptions have no walls, so the parties can get quite a crowd. But everybody’s respectful here. It’s a bit magical. Our destination weddings—the folks that come from Australia and the mainland and from around the world— they get that. Much of our business is from folks who are on vacation and just walk in, completely enchanted by the place.”

Hearing Hedgepeth speak, it’s hard to stay cynical. Only misanthropic psychopaths actually hate weddings. Everyone from Shakespeare to Judd Apatow has used them as the premise for foolishness. There are scrolling feeds on Netflix and racks of magazines, books, and manuals at Barnes and Noble devoted

to the subject. Academics continue to dissect the practice at universities around the world. Ritual unions bring the most bizarre and hilarious out of the drabbest among us: There’s no better send-up than a betrothal gone awry, a drunken uncle speech. Wedding marketers in Hawai‘i have the luxury of selling an obscenely attractive product. It’s the idea of this place, really: Far from home, where fragrant air meets sea spray and technicolor tropical sunsets serve as a backdrop, love blooms eternal. Weddings can be ridiculous affairs, often as improbable and foolish as the love that inspires them. But that never stopped anyone before. People will continue to come to Hawai‘i to fall in love, marry, and embarrass themselves. There are far worse things upon which to build an economy. I’m reminded of a line from the 2005 classic romantic comedy Wedding Crashers: “You know how they say we only use 10 percent of our brains? I think we only use 10 percent of our hearts.”

KARAOKE’S LONG-LASTING, LIFE-GIVING FORCE BREAKS BOUNDARIES AND CONNECTS US TO EACH OTHER.

For the many seniors in Hilo’s Kamana Karaoke Club, karaoke connects them to their past and each other. For Kay Fukuda, singing has more tangible effects: strengthening the muscles in her face, which were affected by Bell’s Palsy.

For the many seniors in Hilo’s Kamana Karaoke Club, karaoke connects them to their past and each other. For Kay Fukuda, singing has more tangible effects: strengthening the muscles in her face, which were affected by Bell’s Palsy.

It’s early afternoon in Hilo and the Kamana Senior Center is a hub of activity. Seniors pass through the center’s pavilion, moving to and from activities in classrooms, calling and waving to each other as they pass or stopping to chat. Emma Souza, president of the Kamana Karaoke Club, approaches a microphone.

Janis Joplin’s “Me and Bobby McGee” rings throughout the space on a giant speaker. “And feeing good was easy, Lord, when he sang the blues,” Souza belts from her favorite country tune.

The echo of the music drowns out the sound of the soft drizzle on the lawn outside. But how could anyone really notice the rain when someone is singing so passionately? As Souza finishes, her peers—a group of older women sitting across the pavilion—look up from their conversations, smile, and clap.

The karaoke program at the senior center is part of Hawai‘i County’s Elderly Recreation Services Activities Division, which provides free classes of all kinds— from yoga to gardening to quilting—for anyone ages 55 and up, resident or not. Karaoke class meets three times each week, and many of its members also participate in the karaoke club. The club officially meets quarterly, but also facilitates other outings throughout the year, including visits to elders in other care facilities who can no longer travel.

These visits are due, in part, to club member and karaoke class teacher Kay Fukuda, whose husband lived in an extensive care facility until recently. After he passed, she and a group of fellow singers

continued to visit residents and perform for those who could no longer sing karaoke themselves. Many of the traditional Japanese songs they sang triggered memories of childhood for the residents there.

The Kamana Karaoke Club has been a way for many seniors to connect through song for more than 30 years. Many of them began singing tunes in their native languages at parties and family gatherings when they were children. When they were young, “karaoke” hadn’t been coined as any particular concept. Singing was just what people did to socialize. For this group of seniors, Kamana Karaoke Club is not just a musical outlet, but a way for the seniors to reconnect with childhood memories.

Kamana Karaoke Club holds a yearly Karaoke Review every April, inviting senior karaoke clubs from other islands to perform. The review—Souza calls it a showcase of the islands’ best talent—has become widely known around town. The last review was held at Aunty Sally’s Luau House in Hilo. “It was decked out with so many flowers that it didn’t even look like Aunty Sally’s anymore!” Souza recalls. The public, even Big Island Mayor Billy Kenoi, came dressed to the nines. In fact, so many clubs have become interested in the review, which is in its 29th year, that singers now have to audition first in order to be selected to perform.

Back at Kamana Senior Center, it’s Fukuda’s turn to sing. She’s older, with a small frame, kind face, and sweet smile. She speaks softly, but is opinionated once you get her talking, and her singing voice comes as a pleasant surprise. She starts in on a traditional Japanese song, with lilting background music and a harmonious melody. She stands still, focused on the words. When she’s done, she brushes off praise and says she has a cold. Souza describes Fukuda as the more traditional of the two. While growing up in Hilo, Fukuda and others sang exclusively in Japanese, and used to stand and bow before every song.

A quick Google search generates millions of hits related to karaoke—evidence that this once traditional pastime has permeated pop culture. The first karaoke machine was created by a musician named Daisuke Inoue in 1971. Inoue lived in Kobe, Japan and played drums in a band that would accompany bar patrons when they wanted

to sing. He later told a reporter for The Guardian that he was a terrible musician, so he created a machine to play for him when he didn’t want to. He had 11 made, and leased them to local businesses. By the 1980s, karaoke (a Japanese abbreviated compound word made from “kara,” meaning empty, and “oke,” or orchestra) was booming in Japan.

Though karaoke traces its roots to Japan, it is in Hawai‘i—a place filled with diverse cultures and classes—that karaoke is, perhaps, most beloved. Locals like to think of Hawai‘i as the karaoke capital of the world. Maybe it’s because of the strong influence of Japanese culture. For Souza and Fukuda, though they may communicate differently—Souza is full of words and explanations but always passes the buck to her friend to tell the real story, while Fukuda is sweet in nature but blunt with her words—song forms the language of their history. The two friends have no shame. For them, karaoke isn’t a practice, it’s a way of living, and it seems to keep them present in the moment, open to whatever comes next.

Souza didn’t begin going to formal karaoke bars until her adult life. Now, she gathers with a group of friends to sing every week. Today, as she sings at the pavilion, she reads the lyrics off her iPhone. It’s a modern accessory juxtaposed with a traditional art. But things at the senior center aren’t that modern yet. There’s no giant television with words flashing across the screen, like those found in contemporary karaoke clubs. Just like old times, most people read the lyrics off sheets of paper from a giant songbook. When they perform, they memorize the songs.

“[Karaoke is] a form of relaxation, helps with your memory, your overall health, disposition, and emotional wellbeing,” says Souza, who sings to help keep her lungs healthy and her asthma at bay. For Fukuda, karaoke has strengthened the muscles in her face, which were affected by Bell’s Palsy. “After each song,” Souza says, “I feel rejuvenated and ready to charge.”

To hear Souza’s and Fukuda’s stories is to hear insight into a culture not defined by time. Like them, my own memories resurface when I hear and sing familiar songs. My interest in karaoke runs deep. My parents rented a karaoke machine for my 12th birthday, and I got my own

machine at 16. I’ve been going to karaoke bars since I was old enough to, belting the likes of Whitney Houston or Mariah Carey and eating fried food at late-night establishments. So I could only thank my lucky stars when a year ago, I heard of the opening of a late-night karaoke bar across town. Since then, Kanpai Noodles, Sushi, and Sake has transformed Hilo’s nighttime scene, finally offering a place to eat and gather after 10 p.m., when the sleepy streets have usually cleared.

At Kanpai, the walls are tiled in dark grey and accented by banzai trees placed around the room. Chunky black wooden tables sit in the center of the room, and a curving, polished wood bar top reflects an edgy design aesthetic. At the far end of the room, separated by a beaded curtain, is the karaoke room. It’s long and skinny, with a flatscreen television filling nearly an entire wall. Underneath it is the book—the bible of every

karaoke bar, that tome of pages providing the full list of songs that can be sung.

Sushi chef Mike Ito and owner Issa Hilweh are seated at a shiny black table, but only briefly. It’s an interlude before they get back to business; they’re the kind of people who work every day because they love what they do. Hilweh’s concept for the restaurant was to bring a positive, after-hours dining experience to Hilo. Kanpai serves food (fresh, never fried or frozen) until 1 a.m., something unheard of in Hilo before now.

“My initial reasoning was because you go around to these karaoke bars and it’s the same exact concept in every one. It’s not somewhere you want to bring a family or go to dinner. We wanted to do something a little bit more modern,” Hilweh says. Ito, who is Japanese himself, agrees. They aren’t saying there’s anything wrong with tradition, but that the concept of Kanpai is meant to elevate the traditional notion of

a gathering place with a karaoke room that breaks social boundaries. “Once anyone starts singing,” Ito muses, “you feel comfortable.” I thumb through that familiar, hefty book of songs and enter classic karaoke favorites: “Wannabe” by the Spice Girls, “What’s Up” by 4 Non Blondes, and of course, “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen. Just like Souza, when I finish singing, I feel rejuvenated. It’s not the food, or the room, or even the karaoke, but the memory of something good that I’ll keep with me long after the last note fades.

Growing up, Makua (right) was forced to play music at keiki surf contest award ceremonies

“You know, ‘Brown Eyed Girl,’ ‘Noho’ Pai Pai,’ the classics.”

Growing up, Makua (right) was forced to play music at keiki surf contest award ceremonies

“You know, ‘Brown Eyed Girl,’ ‘Noho’ Pai Pai,’ the classics.”

MAKUA ROTHMAN IS A BIG WAVE SURFING CHAMP, PROFESSIONAL MUSICIAN, FATHER OF TWO, AND SON OF AN INFAMOUS NORTH SHORE CHARACTER. HE HAS EAGERLY TAKEN ON A ROLE AS THE CAPACIOUS AMBASSADOR OF HAWAI‘I’S MODERN SURF CULTURE. NOW, HE SAYS, IT’S TIME TO GET ORGANIZED.

TEXT BY SONNY GANADENJust past a bakery known for its gloriously unhealthy pies, where the color of tourists’ limbs range from Elmer’s Glue white to Red Lobster crimson, the Rothman ‘ohana compound is abuzz. A contractor and friend of Makuakai Rothman (Makua, for short) hammers away at the siding of a garage dedicated to a growing surfboard collection.