SWIMMING WITH SHARKS

THE WRECK THAT INSPIRED MOBY-DICK

AHOY! LIFE ON BOATS

THE SEA

+ FORM : 2015 | 2016 STYLE SUPPLEMENT

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES

|

44

WHERE THE SHARKS LIVE

For decades, sharks have been fodder for many a tale. Managing editor Anna Harmon traces man’s relationship with the predators since ancient Hawai‘i and takes the plunge on two cage-free shark tours, coming face to face with the ocean’s most feared creatures.

50

EVER FORWARD AND TO THE HORIZON

Tradition meets speed just offshore of Kailua-Kona, where editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden documents how the young men of Na Koa O Kona train relentlessly to rival Tahitian dominators of outrigger canoe paddling.

58

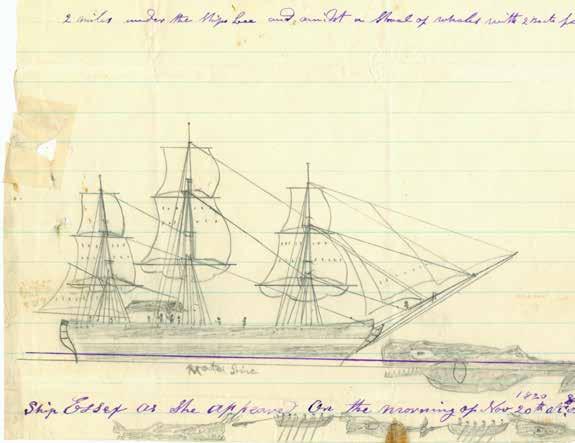

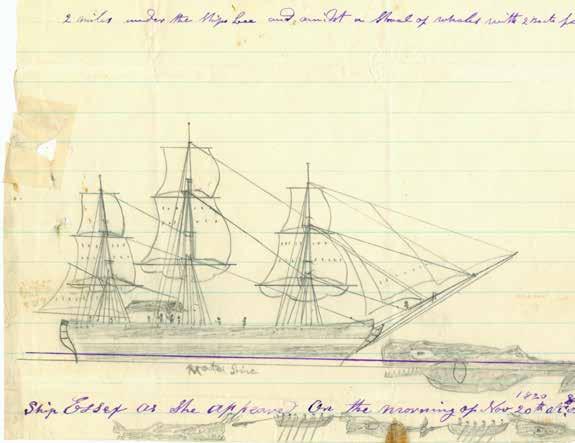

HARPOONS IN THE DEEP BLUE HAYSTACK

Whaling has a deep-seated history in the isles. Travis Hancock dives back in time to uncover the legacy of an industry that defined Hawai‘i in the 19th century, and tells the story of the ill-fated whalers that inspired Moby-Dick

Maritime archaeologist Jason Raupp takes a compass bearing on a try-pot at the Two Brothers whaling shipwreck site at the French Frigate Shoals. Image by Tane Casserley and courtesy of NOAA.

70

AHOY! LIFE ON BOATS

Who in their right minds would spend every day on the salty seas? From a seasick wanderer to a family of four, these two stories of boat dwellers reveal how life is full of adventure for those who make the ocean their home.

plus:

FORM

Tis 2015/2016 style and product supplement showcases looks from Tiffany & Co. and Vivienne Westwood, features wares from the FLUX Hawaii General Store, and highlights the Creative Lab Fashion Immersive Program.

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

58

EDITOR’S LETTER CONTRIBUTORS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 22 LOCAL MOCO KAI LENNY FLUX PHILES 28 ART: MARK CUNNINGHAM 32 ART: WAYNE LEVIN 40 CULTURE: KIMI WERNER VIEWS IN FLUX TRAVEL 76 OKINAWA: THE SCOURGE OF OURA BAY CULTURE IN FLUX 84 OGO : RECIPES BY HOME COOK JENNY ENGLE EVENT 90 FLUX HAWAII GENERAL STORE A HUI HOU 96 LET THE BAD TIMES BLOW 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Kai Lenny paddles the Moloka‘i to O‘ahu Paddleboard World Championships.

Fine art photographer Wayne Levin dives near his home on the Big Island.

32 22 28

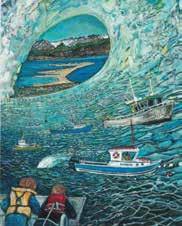

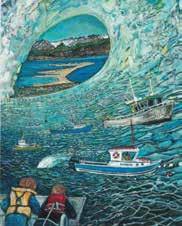

Mark Cunningham salvages underwater finds to create works of art.

NO CAGE? NO WAY!

What’s it like to swim free with sharks? See for yourself as Philip Lemoine takes you aboard and underwater with two shark tours, Islandview Hawai‘i and One Ocean Diving, both based on O‘ahu’s North Shore.

BTS: MAKING OF FORM

Go behind the scenes to see how the Vivienne Westwood editorial in the Form supplement came to life in a one-bedroom apartment in Mānoa.

#FLUXOCEAN

ON THE COVER:

RECAP: #ALOHANYC

In September, for New York Fashion Week, we took the show on the road with the FLUX Hawaii General Store, curated in collaboration with Mori by Art + Flea. Check out how our journey to the other side of the country brought aloha to Brooklyn.

WIN A NEW SURFBOARD WITH #FLUXOCEAN

Post a picture of your favorite moment oceanside on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter and tag @fluxhawaii @surfboardfactoryhawaii #fluxocean for a chance to win a surfboard from Surfboard Factory Outlet. Contest runs from November 30 to December 14, 2015. Photos must be posted during this time.

Shown on the cover is bodysurfing legend Mark Cunningham, whose iconic speedos and silver hair have made him immediately distinguishable in the water for years. Now 59, Cunningham is creating a name for himself, this time on land, as an artist. Objects found in the ocean are his medium, from encrusted surfboard fins and old watches to cellphones and hotel cards, which he turns into sculptural works of art. Of his work, Cunningham says, “I’m just starting this journey, and it’s crazy how everything is happening so fast.”

SHOT BY JOHN HOOK.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE

| FLUXHAWAII.COM |

OF CONTENTS

IMAGE

EDITOR’S LETTER

I have a confession: I never did like the ocean much. I guess you could say I was more of a pool kind of child. In a pool, I never had to worry about what I couldn’t see below, and aside from the smell of chlorine, it never left me with that sticky salty feeling like the ocean did after not rinsing off nearly well enough because the beach showers were always so cold. Te worst part about the ocean was the whole getting in part, wading up to my hips and waiting to adjust to the water’s temperature, oddly chilly for it being so sunny, just to have an annoying brother or cousin splash—and spite—me.

In elementary school, my father started taking me bodyboarding at Kewalos. He thought it would be a good opportunity for father-daughter bonding, I suppose. I hated it. Hated navigating down the rock wall; hated the long paddle to get out to the break; hated duck-diving and the impending feeling of being caught inside on a set; hated the feeling of sitting in wet clothes on the drive home.

Eventually, when I got old enough, I started going to the beach on my own (mostly, I think, because all my friends were doing it). Bodyboarding gave way to longboarding, which gave way to short. I surfed all over the island, from Mākaha on the west side to Rocky Point up north, from crowded breaks on the south shore to empty ones on the east. I even surfed around the world, in Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Bangladesh. I’ve seen fireworks light up the reef while nightsurfing at Kaisers, been spooked by the flap of a surfacing stingray, had my brow split open in Bali.

And then I stopped. From 2010 and for the next five years, I paddled out a total of three times. I had just started this magazine, and as I said, I never liked the beach all that much anyway. (Read: I never did get that good at surfing.) But the sea has a way of pulling you back. In July, spurred on by my fiancé, who had recently taken up standup paddling, I purchased a 9’4” board off the rack at Surf N Sea in Hale‘iwa—and have been hooked, in a way that I had not been before, ever since.

Te ocean works in mysterious ways. It teaches you all of life’s lessons, as the dynamic young waterman Kai Lenny, featured on page 22, says. Despite the sea’s ever-changing temperaments, from churning furor to placid calm, it remains a constant in the lives of those featured in this issue, their faithful companion in work, play, and everything in between.

Despite our recent reunion, my relationship with the sea has changed little since my younger days: I’m still horrible at pushing past breaking waves; I still sit as far out in the lineup as possible to avoid being caught on the inside; I still hate the sticky salty feeling left on my skin and in my hair after a dip. But now that I’m older and wiser, I always, always make sure to bring an extra change of clothes for the drive home.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor lisa@nellamediagroup.com

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| THE SEA |

WHAT DO YOU LOVE ABOUT THE SEA?

“Its vastness. How, on hard days when the deafening crush of its waves matches your mood, you feel small again.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNER

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR - AT - LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Chris Balidio

Brian Bielmann

Mike Caputo

Jon Letman

D.J. Struntz

Justin Turkowski

MASTHEAD | THE SEA |

CONTRIBUTORS

Le‘a Gleason

Kelli Gratz

Travis Hancock

Jeff Hawe

Jon Letman

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Carrie Shuler MARKETING & CREATIVE COORDINATOR

“It’s the core to my happiness. I plan everything else around it.”

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Mitchell Fong JUNIOR DESIGNER General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

“It doesn’t matter how I feel, even if I don’t really want to get in it, the ocean is always able to refresh and recharge the soul.”

©2009-2015 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

CONTRIBUTORS

MIKE CAPUTO

Photographing the Na Koa O Kona paddling team with his Nikonos, Mike Caputo did his best not to get run over. “I was in the water taking photos directly in their path,” he says of the Big Island team featured in “Ever Forward and to the Horizon” on page 50. “I should have gotten hazardous pay. But the most interesting thing was seeing the drive of the individuals without a coach solidify as a competitive force.” Caputo, who describes himself as an “immense, slambang, honest-to-goodness, three-fisted humdinger,” is a seaman. Literally. As a Merchant Marine, Caputo sailed around the world more times than he can remember. Now, the Chicago-native is a firefighter in Hilo. “With all that adventure, my most memorable moment is a simple, recurring one—taking my kids to the beach to play sea monster.”

TRAVIS HANCOCK

Travis Hancock, who wrote “Harpoons in the Deep Blue Haystack” on page 58, first came across Two Brothers by way of Herman Melville. His intrigue only grew after seeing the documentary Lightning Strikes Twice, featuring the dive team claiming to have found a ship connected to the one that inspired Moby-Dick. “When I learned about the shipwreck’s links to Hawai‘i, I was hooked.” Te writer, skateboarder, and university lecturer grew up on O‘ahu’s North Shore, where at the sweet age of 16, he got sucked out at Waimea Bay while bodysurfing during a massive winter swell. “After treading water for what felt like an hour,” he recalls, “a giant paddled up to me on a boogie board. It turned out to be a Tahitian kid from my French class. He put me on the board and towed me by his leash through a brief gap in the sets.”

JOHN HOOK

Neither FLUX photography director John Hook nor Mark Cunningham, featured in “Art Aquatic” on page 28, wanted to get together for Cunningham’s portrait session in the early hours. But it wasn’t because they don’t get along swell. “Both of us knew shooting in the morning would be better, but we were reluctant to say so because there was a fading south swell at the time,” Hook says. “We knew the morning was going to be the best time to surf.” Ten, a compromise: “We went out for an early morning swim at Point Panic,” says Hook, a self-taught photographer who began shooting as a hobby in the mid-1990s and also captures couples in love as a wedding photographer. “I figured I could get extra filler shots for the story. We ended up getting the cover that morning.”

18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

THE

|

SEA |

FLUX Me Baby, Enclosed please find:

1. Check for two years of your awesome FLUX.

2. Postcard of painting from WCC show—just in case you haven’t seen it, as it is almost as groovy as FLUX!

3. A picture of me with my completed BUCKET LIST and now that I have a subscription to FLUX it really is completed!

Love Allllllllways and Dim Sum then done,

Loved the karaoke story [“Pass the Mic,” from the Charm issue, August–October 2015]. It really is so good for the soul. We recently took our 77-year-old grandma out on a karaoke outing. Her face lit up at old tunes she used to sing. One of her favorites is Frank Sinatra’s “My Way.” It’s a telling song since she’s a stubborn old bird.

Chanel Reyes via email

From @jcabarteja, who submitted this photo for our Instagram shaka contest: “Tat time I threw a shaka at the xray machine #tbt #fluxshaka”

From @veexc_, who submitted this photo to our shaka contest: “Oldie but goodie. Fun fact: Te Bus flashes this shaka (preceded by a “Mahalo” sign) when you allow them to intertwine in your lane. Just a subtle sign of Aloha Spirit.”

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM LETTERS TO THE EDITOR WE WELCOME AND VALUE YOUR FEEDBACK. SEND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO: LISA NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM OR MAIL TO FLUX HAWAII, 36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A, HONOLULU, HI 96817.

Blue G Smith

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

UNQUENCHABLE

DYNAMIC WATERMAN KAI LENNY ALWAYS PADDLES OUT.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23 LOCAL

| KAI LENNY |

MOCO

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA

IMAGES BY BRIAN BIELMANN

“As I was underwater, I just couldn’t get out of my head the amazing view I had,” says Kai Lenny about a wipeout at Jaws on Maui.

It was 30 seconds. Tirty seconds that Kai Lenny was held underwater, 30 seconds that ticked by after he wiped out on a 50foot monstrosity at Pe‘ahi, also known as Jaws, Maui’s infamous big-wave surf break. Moments before, the surfer bottom-turned into a barrel the size of a house—the biggest he’s ever ridden. Ten it closed in on him, the weight of millions of tons of water pressing down on him.

“I got absolutely destroyed,” Kai recalls. “It’s like you’re watching a movie. You can’t save the character in the film. You can just sit there and watch from your seat. … But as I was underwater, I just couldn’t get out of my head the amazing view I had. Bar-none it was the happiest I’ve ever been when I came up, and I just wish I could experience it again soon.”

Te 22-year-old, who excels at surf sports of all kinds (he’s a six-time standup paddle world champ, and is versed in kiteboarding,

windsurfing, and foilboarding, among others), has an uncanny ability to see the good in all things. Recalling another massive wipeout at Jaws when he was dragged underwater for the length of two football fields and his foot was nearly cut in half after his surfboard fin tomahawked through his toes, he’s still stoked: “Tat was also a really good experience,” he says, “because I know I can survive it.”

Such positivity has defined Kai since he was a kid doing his best to make the most of every moment. His parents, Martin and Paula, are avid windsurfers from California. Te couple, who vacationed on Maui decades ago and never left, made a pact that they would not change their lifestyles after Kai and his younger brother, Ridge, were born. “We would go to the beach every chance we could,” Kai’s father, Martin, says. “[Kai] was kinda doomed. … We had a little crib in the van that we’d put out on the

beach. Ten we’d go surfing, and then later in the afternoon, it’d get windy, so we’d go windsurfing.”

Te young Kai reasoned he could either sit on the beach and “get sandblasted,” or he could go out into the water. So he paddled out, and at 4 years old caught his first wave with the longboard his parents had left for him on the beach. Tis was on a small inside break at a spot called Tousand Peaks on Maui’s west shore. “Down the beach, I saw this little perfect wave,” he recalls. “I just remember dropping in for what felt like forever. … It was probably pretty small, like ankle-high, but it felt like it was a huge drop—I mean at 4 years old, you’re not even three feet tall—and I knew exactly what I wanted to do with the rest of my life.”

Since then, Kai has done just that, exploding onto the crossover boardsports scene with unparalleled dynamism. Te multi-dimensional athlete, who’s been

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

One day after taking second overall in a grueling paddleboard contest spanning the 32-mile channel from Moloka‘i to O‘ahu, Lenny helped host an ocean-safety clinic for kids.

sponsored by Maui-based surf company Naish since he was 9 and Red Bull since he was 11, has been around the world and back. Standup paddling has taken him across a lake in Germany, through rapids in Colorado, and down the face of perfect waves in Fiji. He bet his kiteboard could win against a $15 million dollar yacht, racing Oracle Team USA down the San Francisco Bay. He even scaled mountains in Patagonia with Navy SEALs, crossing glacial lakes and clearing crevasses, in order to push the limits of his training.

But it’s Hawai‘i he returns to. “It’s the one place where I can really breathe,” says Kai, who, even as he says this, is preparing for trips to Bermuda, Japan, and Oregon for competitions and training. Despite his busy schedule, Kai makes time for the foundation he created in 2015, Positively Kai, which provides grants to nonprofits for improving ocean awareness and youth

development. “Te purpose is to really open kids’ minds to their potential future, and to show them that they can make anything of their life,” Kai says. “It’s not necessarily about becoming a professional surfer, it’s teaching kids life lessons through surfing—and the ocean will teach you all life lessons.”

Just one day after placing second overall in the Moloka‘i 2 O‘ahu Paddleboard World Championships—a grueling 32mile channel crossing considered one of the world’s most prestigious paddleboard races—Kai was back in the water to host an ocean-safety surf clinic with Duane DeSoto’s nonprofit, Nā Kama Kai, which empowers youth through ocean-based programs. He also donated $10,000 to it.

Like the kids who partook in the clinic, Kai sees himself as a perpetual student, even as a seasoned pro. “Te time you stop getting better at something is when you

forget how to learn,” Kai says. “I’m just going to keep putting my paddle in front of me. I’m going to try and get closer to that island. Tere’s no better feeling than when you’re coming into the home stretch and you’re like, I made it. Or, I’m making it.”

For more information on Kai and his foundation, visit positivelykai.com.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“Mother Nature is the real artist. I’m just putting it all together for everyone to see,” says legendary bodysurfer Mark Cunningham of his found object creations.

“Mother Nature is the real artist. I’m just putting it all together for everyone to see,” says legendary bodysurfer Mark Cunningham of his found object creations.

ART AQUATIC

MARK CUNNINGHAM GIVES NEW LIFE TO FOUND OBJECTS.

TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

“I’m having a hard time calling myself the a-word,” bodysurfing legend Mark Cunningham jokes, referring to his new profession as an artist. “I’m just starting this journey, and it’s crazy how everything is happening so fast.” He roots through a mess of his found objects on a late-summer afternoon, pulling up a calcium-encrusted surfboard fin. “Before they invented leash plugs, people would drill holes into the back of their fins and would tie their leash to it,” says Cunningham, holding up the old fin with a hole in it. “So when you find those, you know it’s from back in the day.”

Within seconds of meeting Cunningham at his beautiful home in Kāhala, I come to the deduction that I’m either going to get lost in his garage looking at objects reclaimed from the sea, or end up doing something unexpected, like night bodysurfing. Tis conclusion is brought on by Cunningham’s charming, bright and playful energy. He’s anything but wily, but somehow just for a moment, Cunningham is able to draw me out of my bubble and actually have me secretly hoping for a nighttime rendezvous.

Tough Cunningham may have made a name for himself bodysurfing massive Pipeline waves with nothing but the skin on his back (and of course his iconic Speedos), his art—three-dimensional sculptures made from personal items lost at sea—has opened up a new realm of creativity he never knew he had. His work has been displayed in galleries in San Francisco, New York, and Hawai‘i, earning the attention of gallery owners and critics, and has even appeared on television shows like Hawaii Five-O.

A childhood spent in Hawai‘i, immersed in surf culture, helped Cunningham start this journey toward becoming an artist. He grew up in the seaside neighborhood of Niu Valley with only one thing on his mind: surfing (well, that and girls). Now 59, Cunningham delights in items that look like they’ve been chewed up and thrown back out to sea. Te found objects all have a sort of strange history to them, be it a vintage gold watch, hotel key, designer necklace, or even the driftwood he uses to mount the objects upon. “Mother Nature is the real artist,” he says. “I’m just putting it all together for everyone to see.”

Cunningham’s artistic practice grew out of his profession as a Honolulu City and County lifeguard, when he would find lost, battered items on the near-shore seabed or in the surf. He was like O‘ahu’s own Aquaman, returning lost objects to their respective owners, keeping what he wasn’t able to give back. By the time he retired from his post at ‘Ehukai Beach Park in 2005, Cunningham had amassed an impressive collection of sea gems: precious stones as big as my thumb, broken glass rounded and softened by the hands of time, vintage cameras, sunglasses, watches, the occasional paddle, and an assemblage of fins stuffed into a large tin pail that became a signature piece entitled Fin Anemone

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 29 FLUX PHILES | ART |

Several years ago, John Koga, a respected local artist and curator, visited Cunningham’s house and saw the pail full of fins. “‘Holy fuck, that’s art. You’re an artist,’” Cunningham recalls Koga saying. “[Koga has] become sort of my sensei.” Inspiration also came from his longtime partner Katye Killebrew, whose custom jewelry line, MiNei, offers popular earrings made with encrusted sunglass lenses. “I saw how happy it made her, and how well people responded to her stuff. I think the best part is how we are always spending time together in the water, and showing each other the things we’ve found.”

Tere’s something hopeful about the artwork of Cunningham. Maybe it’s the repurposing of lost objects from the sea to form strikingly textural, organic forms that can seem joyful or buoyant. Or maybe it’s the spirit of his subject matter. He speaks to his finds, and imagines them responding. He holds a crusty fin and asks, “Who did you belong to? How did you get lost?”

By the time Mark Cunningham retired from lifeguarding in 2005, he had amassed an impressive collection of weathered items found on the seabed or on shore, from vintage cameras to surfboard fins.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“It’s a mysterious world a little bit beyond our comprehension, and I want to convey that,” photographer

Wayne Levin says of the ocean.

MYSTERY OF THE DEEP

WAYNE LEVIN’S STARK BLACK AND WHITE IMAGES ENHANCE THE ALLURE OF THE SEA.

TEXT BY LE‘A GLEASON

PORTRAIT IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

When Wayne Levin took the train with his grandmother from Southern California to Portland, Oregon as a child, he saw life in freeze-frame rectangles for the first time. Tose window-shaped mental pictures were early practice for a lifetime that would be spent framing images of some of the most incredible scenes on earth: massive schools of fish in swirling patterns, rare moments with undersea creatures, surfers ducking beneath sparkling clouds of whitewash, epic landscapes of lush forests and towering mountains. Levin had a knack for photography from the moment he received his first camera at 12 years old as a present from his dad, a doctor who never pressured him to follow in his footsteps. “I got a lot of encouragement with my photography, and I felt like even at a young age, it was something I could do well,” remembers Levin, who went on to attend Brooks Institute of Photography in Santa Barbara after high school. His family moved to Hawai‘i in 1968, and Levin’s love of travel photography was sparked. He spent a year and a half sailing through the South Pacific and trekking through parts of Asia, Europe, Mexico, and Central America. Tese images would become the basis for his first solo exhibit at Gima’s Art Gallery in Honolulu.

In 1983, after receiving his BFA in photography from the San Francisco Art Institute and his MFA from Pratt Institute in New York City, Levin returned to Hawai‘i to teach photography at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. It was here that he began to explore underwater photography for the first time.

“I loved the way it looked underwater to see the waves breaking on the shoreline,” Levin says. To capture this, he borrowed an underwater camera from a friend. But when he took it out into the ocean, he and the camera were pummeled by an onslaught of waves. “It’s not so much the wave bashing you on the rocks [you have to worry about] as it is when the wave sucks out,” he explains. “Te water level will drop, and you get dragged over rocks or coral.” Te experience was the best mistake he ever made, because he was obligated to trade one of his own camera lenses in exchange for keeping the scratched underwater camera, buying himself his first real look at the underwater world he was falling in love with.

In addition to his under-sea photography, Levin’s on-land work continued to garner wide recognition. Over the years, he worked as an assistant for environmentalist and renowned Hawai‘i photographer Robert Wenkham; documented the Kalaupapa Leprosy Settlement on Moloka‘i, which led to the book Kalaupapa: A Portrait; worked as an artist-in-residence at the Dayton Art institute in Ohio; and started the photography program at La Pietra, Hawaii School For Girls, where he would eventually marry his wife, Mary, in 1990, having met her at the old Amfac Gallery where they both had photos on exhibit.

Shortly thereafter, Levin moved to the sunny town of Kona on the Big Island, where his love of diving and underwater photography grew. Over time, his values in photographic work changed, too. Instead of producing just one stellar image, he became fascinated with communicating thoughts and emotions via a series of photographs.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 33 FLUX PHILES | ART |

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

Fish and swimmers at the Ironman Triathlon. Image by Wayne Levin.

Ascending freedivers. Image by Wayne Levin.

Ascending freedivers. Image by Wayne Levin.

For more than a decade, Levin photographed schools of akule, creating an impressive series of images depicting hundreds of dazzling fish moving through the water in precise spherical formations. “I loved the mesmerizing movement of the school, and the amazing shapes it made,” Levin says. “Te coordination of the spontaneous movements and the tight mass of the school made it appear like a single entity, with the individual fish like cells within a larger organism.” Te series was eventually published in 2010 in Akule, a book of black and white images of the impressive fish schools, with a second edition released in fall 2015. Instead of focusing on eye contact, being up close, or getting the perfect

angle, Levin’s photographs emphasize the relationship between the subjects and their environments. Candid moments of jellyfish and dolphins beside towering coral reefs, or intricate patterns on the sea floor made by the tides, are presented in stark black and white moments. “It’s a mysterious world a little bit beyond our comprehension, and I want to convey that,” Levin says. “With my underwater photography, I’m not trying to clarify the world beneath its surface, I’m trying to deepen the mystery.”

For more information, visit waynelevinimages.com.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

When Kimi Werner was 5 years old, she began accompanying her father on his regular spearfishing dives. Today, the former champion spearfisher continues to be an advocate for responsible food sourcing and the importance of healthy oceans.

Image of Werner near San Salvador Island in the Bahamas shot by D.J. Struntz.

When Kimi Werner was 5 years old, she began accompanying her father on his regular spearfishing dives. Today, the former champion spearfisher continues to be an advocate for responsible food sourcing and the importance of healthy oceans.

Image of Werner near San Salvador Island in the Bahamas shot by D.J. Struntz.

CATCH AND RELEASE

WHEN KIMI WERNER LEFT COMPETITIVE SPEARFISHING, SHE FOUND A NEW PLACE IN THE WATER.

TEXT BY JEFF HAWE

IMAGES BY D.J. STRUNTZ & JUSTIN TURKOWSKI

Just as when she is anywhere within splashing distance of the ocean, Kimi Werner is at ease on a boat in the middle of the Caribbean Sea. Te 35-year-old, who made a name for herself in the male-dominated world of spearfishing, is embarking on a weeklong trip with 5 Gyres—a nonprofit aiming to reduce plastic pollution—that will address how to maintain a healthy ocean ecosystem. Moments before throwing off mooring lines, she receives a notice from the San Sebastian Surf Film Festival: Tey plan to screen a film she submitted, Te Story Of An Island, a travel short about how diving connected her with the local culture on Robinson Crusoe Island in Fiji. Te only problem is that the film does not exist. Te festival, in San Sebastian, Spain, starts in less than two weeks, and all Werner has so far is a trailer. Realistically, she will have just four days to edit and complete it. Without a second’s hesitation, she responds affirmatively. Werner and her partner, Justin Turkowski, will make it happen.

Whirlwind events are not atypical in the life of this former champion spearfisher and Renaissance woman. Zigzagging the globe, Werner travels from one commitment to the next: TV and movie projects, conferences and festivals, dive trips to remote locations like the Tuamotu Archipelago. Werner is known for her dexterity in the ocean, swimming with a great white shark as if it was merely a dolphin, and freediving to notable depths. But it is her conscious work out of the water that has made the most impact. It’s a mentality she developed while growing up in Haiku on Maui. Her parents raised her and her two siblings on tightly limited resources, with daily chores that included placing pots and pans around their one-bedroom shack to catch rainwater, and gathering chicken eggs from under the house. Tese meager beginnings taught Werner to appreciate what she had, and to waste nothing. “Basically I grew up with nature and family,” she recalls. “It was a life lived outside, and a lot of it was spent in the ocean.”

When Werner was 5 years old, she began accompanying her father on his regular spearfishing dives. She recounts clinging to her father’s back as he climbed down a cliff to his favorite dive site, then floating on a boogie board as he gathered food for the family. “I would always end up off the boogie board, swimming, so he just began leaving it at home,” she says. As the Werner family grew, trips to the store slowly began to replace trips to the ocean. Tis change did not go unnoticed by Werner. “I missed everything about it,” she recalls. “I would ask my mom why my eggs for breakfast tasted so weird, and she explained they were from the store. So at 7 years old, I just thought store-bought meant manmade, which meant fake.”

Werner found herself missing that connection with her food, as well as the thrill found in attaining it, so after graduating from Maui High School, she moved to O‘ahu in 1998 to study at the Culinary Institute of the Pacific. Mostly, however, she was working as a waitress and spending her free time paddling outrigger canoes. It wasn’t until a crew barbecue one afternoon when some of the guys brought fish they had just speared that a switch flipped for Werner, and the sea drew her back to spending her days diving and fishing.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 41 FLUX PHILES | CULTURE |

In 2005, she began training under the tutelage of Kalei Fernandez and Wayde Hayashi, who had both taken notice of her natural skill. Each being renowned divers, with victories in the U.S. National Spearfishing Championships themselves, the pair helped Werner cinch the 2008 national title in a competition of primarily, as she describes, “big burly men.” But after a year and a half of intense competition, Werner began to feel something was wrong. “I realized I was over it,” she says. “I didn’t know who I was without all the titles and winning. It got to a point when I was going out for a dive that I no longer felt happy, and that was the biggest loss. I missed the magic, and I didn’t know if I could get that back.”

Overburdened with self-doubt, Werner walked away from competition, and left for the archipelago of Palau. Upon her return, instead of bringing home a trophy, she came back with a different way of looking

at the fish she spent so much time catching. “I [learned about] how the different locals wherever I was traveling eat the fish, and how they manage their natural resources,” Werner says. “What does fish mean to your culture? Tese things were just more interesting to me.”

Today, Werner continues to be an advocate for responsible food sourcing and the importance of healthy oceans, as highlighted in Te Story Of An Island, which debuted at the San Sebastian festival in July 2015. A short film about diving a pristine destination and taking the time to engage with the local culture, it encompasses what Werner is up to these days. “We all have different skillsets,” she says. “It comes down to connecting with a cause, and then figuring out the best way that each of us can help with the abilities we possess.”

Keep up with Werner on Instagram @kimi_swimmy.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

After Werner quit competitive spearfishing, she began to see the world differently, learning about how other peoples manage their natural resources: “What does fish mean to your culture? These things were just more interesting to me.”

Image of Werner off the Juan Fernández Islands in Chile shot by Justin Turkowski.

WHERE THE SHARKS LIVE

A REFLECTION ON HAWAI‘I’S INTIMATE RELATIONSHIP WITH THE MOST FEARED CREATURES OF THE OCEAN.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

When I was in high school, I wanted to be an animal behaviorist. For a senior assignment, I had to shadow someone with my dream job, and the closest I could get was the management of a wolf sanctuary. Volunteers were boiling chickens to feed the wolves and wolf-dog hybrids when I showed up. After explaining what I wanted to do, one of them told me to forget it. You can’t see animals in the wild, he said. Te instant humans are around, their behavior changes. Instead, he suggested, study humans.

In the summer of 2015, North Carolina experienced a rash of shark bites in shallow waters—eight, to be exact. Tere are 50 types of sharks off the shores of the state, of which 10 are known to have bitten humans; no one can be sure of the exact culprits, or the cause. Two encounters resulted in lost limbs, meaning these were probably perpetrated by bull or tiger sharks. Te series of events sparked national and international chatter, and a wide array of speculation about why this summer was so risky, ranging from a “shift in ecology” to the fact that it had been unusually hot, meaning people were flocking to the beach. But humans, it turns out, are a much greater threat to sharks. In 2010 alone, it is estimated that up to 97 million sharks were caught as by-catch, for sport, or for their fins. Despite such statistics, humans still largely fear the creatures. Tis is because they are at home in a world that humans have never fully adapted to but continually enter. Sharks roam waters around the world, even those alongside urban areas, and are incredibly quick and agile; comparatively, humans are pitifully clueless and defenseless animals in the ocean. Even brief, mistaken encounters between the two can leave individuals badly hurt. To regain control of this situation, humans have turned to culling, research, and face-on encounters.

In Hawai‘i, the relationships humans have with sharks vary. My hairdresser, whose family is from the islands but who grew up for part of her youth on the mainland, rarely goes into the ocean—when she does, she gets chicken skin because she imagines a shark is near. Surfers frequent spots like Electric Beach, even though it’s known shark territory. Some Hawaiians still consider the creatures ‘aumākua, or sacred ancestors.

Visitors and locals go on tours to swim with the toothy predators, snapping pictures with GoPros for Instagram accounts, telling stories of near misses; stories of how they have learned to love a creature they once feared, and still kind of do.

Including those that can be seen on such tours on O‘ahu’s North Shore—sandbar sharks, grey reef sharks, Galapagos, and the rare hammerhead or tiger sharks— there are 34 species that frequent Hawai‘i waters. (To say “shark” muddles the array of these animals, which range greatly in size, makeup, and behavior, but it’s the easiest way to group them.) Tis includes great whites, which only make rare appearances here. Tere are records of ancient Hawaiian chiefs canoe-fishing for large sharks, which they called niuhi, thought to be tiger and even great white sharks. “Tey could be tamed like pet pigs and be tickled and patted on the head,” wrote Hawaiian historian Samuel Kamakau of niuhi in an essay translated for a volume composed of his writings, Ka Po‘e Kahiko: Te People of Old Hawaiian stories confirm that sharks have been here as long as we can know, and that even then, the relationship between man and beast was fraught with ambiguity. In these ancient tales, sharks run the gamut from villain to god to victim. One story tells of a “shark man” who preys on travelers headed to pick ‘opihi—he runs ahead, morphs from human to shark, and gobbles them up. Another tells of Pehu, the man-eating shark of Maui, lying in wait for a surfer to eat in Waikīkī. A third involves Pearl Harbor’s guardian shark, Ka‘ahupāhau, who considers man-eating sharks to be bad, and notifies fishermen when a group of both good and bad sharks enters the harbor. Unfortunately, neither she nor the fishermen can distinguish the man-eaters, so all the sharks are hauled to shore and left to die in the heat.

In the second half of the 1900s, the state of Hawai‘i authorized shark culling in an attempt to make the waters safer for humans—there were at least eight deaths in the 1950s in which signs pointed to tiger sharks as culprits, though at least one may have been unassociated. From 1959 to 1976, a total of 4,668 sharks were caught and killed, of which 554 were tiger sharks, the type most likely to bite humans in Hawai‘i (they rank second to

great whites worldwide). In spite of the culling, there was no significant decrease in the rate of shark bites during or after, according to the Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology. In 2013, after two fatal encounters in Maui County in one month, culling was considered again—this, despite research showing that lone tiger sharks don’t remain in a set area, nor do they take on special preference for human flesh. For institute researcher Carl Meyer, this ongoing conversation about culling is a philosophical debate, one about “whether it is ethical to kill large predators in order to make the natural environment a safer playground for humans.”

Te first shark tour on O‘ahu’s North Shore opened in 2001, offering cage dives for snorkelers, who float behind metal bars at the ocean’s surface roughly three miles off the coast of Hale‘iwa Harbor, where Hawai‘i waters end and international waters begin. Sharks started coming here in larger numbers in the 1960s, when a crab fisherman began crabbing in the area and tossed his day-old bait from traps overboard, an easy meal for sharks. Now, to entice them to rise from the depths, tour boat captains play with their engines, which emit electrical currents; some tug at lines attached to objects on the ocean floor, simulating a crab fisherman hauling in his cage. Depending on the company and the pressure to deliver, operators may or may not also toss fish into the water before or during dives—but to bring this topic up is to warrant offense, since chumming for shark tours is both taboo and illegal in Hawai‘i—though not in international waters. (Fishermen, on the other hand, can still chum and toss old bait overboard anywhere.)

Te two cage tours here have had a spotted record in the community because of exactly this practice. In 2011, over the course of several months, three North Shore Shark Adventure tour boats were burned in Hale‘iwa Harbor. While the motive behind the arson was never confirmed, five workers from North Shore Shark Adventures and Hawaii Shark Encounters had been arrested for feeding sharks within Hawai‘i waters, and there were fears in the community that hungry sharks were following operators’ boats back to the harbor, and near to human activity. But the Institute of Marine Biology had already dispelled this theory in

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

2009, with a research paper that concluded that sharks remain at cage diving sites throughout the day and disperse at night. Sharks that visited the dive sites even migrate seasonally to deep waters off the west side of O‘ahu, going as far away as Maui and Kaua‘i.

In contrast to cage tours, two cage-free tours now also set out from the harbor. Instead of offering an adrenaline rush from behind bars, these tours count on an extra push of human confidence and curiosity (or, perhaps, bravado). Te fact that tour-goers are willing to pay for such excursions is also a sign that we have become a bit more savvy about sharks. Te first of such tours to set up shop was One Ocean Diving. Co-owned by diver and conservationist Ocean Ramsey and photographer Juan Oliphant, One Ocean started off as a research endeavor in 2010, and expanded to offer cage-free tours out of Hale‘iwa in 2013. Last year, Islandview Hawai‘i, which began offering snorkeling tours off Waimea Bay in 2013, joined the fray—its founder, Kaiwi Berry, is the grandson of the crab fisherman whose day-old bait first began attracting sharks to

the area in larger numbers. Cage-free tour operators believe that the creatures can be trusted when encountered in situations in which they feel secure and submissive, and those in which humans are not easily confused for potential meals. It helps that roughly 98 percent of sharks seen on tours in the area are Galapagos and sandbar sharks, species very rarely involved in shark bites. Te other two percent are tiger sharks.

On my first cage-free shark dive, I didn’t realize how nervous I was until I got out of the water and slowly unclenched my jaw from around the mouthpiece of my snorkel; we had seen Galapagos and grey reef sharks, and while two swam parallel just 20 feet ahead, I couldn’t stop wondering what was at our backs. On my second tour, several of us glimpsed a hammerhead in the distant blue. Tours rarely come across this type of shark, and it felt like a special, shared experience with the others in the water, and with the creature—even though it could hardly care that I was there.

But sometimes, certain sharks do care. On September 20, a spearfisher diving in a cave off the Big Island came face to

face with a jaw-gaping tiger shark, which he grabbed on the nose. It chomped him on the leg, then he punched it, and it swam away (sharks rarely stick around for more than one bite). Why it attacked him will never be known—it could have been hunting for fish, or it could have been a territorial warning that he countered with aggression. Including this one, there have been a recorded 59 shark bites of snorkelers, fishermen, surfers, and swimmers (but no tour-goers) in the islands since 1995. While justifications of such bites vary, theories include acts of defense, curiosity, and mistaken identity. Sharks feel things out with their teeth. Unlike what Ka‘ahupāhau thought and what we would like to believe, there are no good sharks to befriend or bad sharks to defeat—there is only nature, which we try our hardest to but cannot control.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

On cage-free shark tours that set out from Hale‘iwa Harbor, snorkelers can come face to face with Galapagos sharks, grey reef sharks, sandbar sharks, and even the rare tiger shark or hammerhead.

View what it’s like to swim with sharks.

As the fastest team in the Hawaiian Islands, Na Koa O Kona is closing in on the dominance of Tahitian teams who have ruled the sport for decades.

As the fastest team in the Hawaiian Islands, Na Koa O Kona is closing in on the dominance of Tahitian teams who have ruled the sport for decades.

EVER FORWARD AND TO THE HORIZON

THROUGH THE OCEANIC SPORT OF OUTRIGGER CANOE PADDLING, CENTURIES - OLD TRADITION MEETS 21ST CENTURY SPEED JUST OFFSHORE OF KAILUA - KONA ON HAWAI‘I ISLAND, WHERE THE YOUNG MEN OF NA KOA O KONA TRAIN RELENTLESSLY TO RIVAL THE TAHITIAN DOMINATORS OF THE SPORT. AS IS THE CASE THROUGHOUT THE PACIFIC, THESE FAST WATERMEN HAIL FROM A SLOW TOWN.

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGES BY MIKE CAPUTO

The sun is setting on a summer Monday as Kainoa Tanoai and Daniel Chun trade the lead in a fleet of one-man canoes racing along a 12-mile course. Tey accelerate in uneven bursts while surfing bumps of unbroken waves past familiar Kona landmarks: the jagged black cairns of Kaloko-Honokōhau National Historical Park, the rust-red roof of Kona Inn, the dry brush of the old Kona airport. Te pace is a stark contrast to that on land, where oppressive humidity gives the impression of a perpetual nap.

“Good job boys! Round the inside buoy at the church and finish at Honokōhau Harbor!” yells Mike Nakachi, the paddling team’s de facto promoter and coordinator, from the fancy escort boat we are standing in. Nakachi throttles past the racers, gives me the title of timekeeper, and drops me off at the rocky jetty at the mouth of the harbor. I clock Tanoai and Chun tying at 1:24—a blistering pace. Te next teammate to paddle in arrives 10 minutes later. Te one-man time trial determines rank within the crew, the equivalent of a football scouting combine or a basketball-skills test. In addition to racing their teammates, Tanoai and Chun are training for the Super

Aito Va’a (aito roughly translates to strong in Tahitian; va’a, like the Hawaiian word wa‘a, means canoe), a one-man race that consists of three days of brutal, hours-long competition outside of Papeete in Tahiti. Much of their training has been inspired by their French Polynesian counterparts, from the delicate, rudderless outrigger canoes they use to the rigorous practice necessary to propel them forward efficiently.

Te reason Hawai‘i crews model their training after their South-Pacific counterparts is simple: Tahitians almost always win. As the fastest team in the Hawaiian Islands, Na Koa O Kona is the closest crew challenging this dominance. Last summer, this team, formerly known as Mellow Johnny’s, and before that as LiveStrong, became one of few from Hawai‘i in the last generation to win first place against a formidable Tahitian crew. At the 44th annual Queen Lili‘uokalani long distance race, these mostly self-coached athletes beat Paddling Connection, a team of all-star paddlers from Papeete. It may not mean much for those who don’t paddle, but for the outrigger racing diaspora, which stretches across the Pacific and has ports in Rio de Janeiro, Tokyo, New York, and Toronto, it’s major news that the title of

fastest crew may return to Hawai‘i, where modern outrigger racing was first developed.

In Polynesia, paddling has always been more than sport. Prior to Western contact, outrigger canoes were both the day-to-day vehicles of commoners and the finely tuned vessels of both royalty and open-ocean voyages. Traditional Polynesian society developed from a lifestyle intertwined with the sea. Te construction, use, and social hierarchy of canoes facilitated that relationship. Like the rest of Polynesia, Hawaiians used their crafts for transport, conflict, fishing, and play. Unlike the rest of Polynesia, the usual and favorite mode of transportation around the islands was paddling rather than sailing. In the late 19th century, Hawaiian outrigger racing, like hula and chant, was nearly lost due to missionary influence and tragic indigenous population decline.

A century ago, the canoe culture of Kona was essential to the sport’s revival. Many outlying fishing villages off the rugged coast were nearly inaccessible by land until the development of 20th century roads. Te placement of these villages only makes sense when considering that the fastest

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 51

The perspective in the canoe is one of focused labor. Time contracts to the rate of the stroke, and stretches to the expanse of the ocean.

way to traverse the islands historically was via canoe, and that everyone, from child to elder, was adept at its use. In 1906, Prince Jonah Kuhio, an avid paddler, commissioned the building of two racing canoes for speed, named Princess and ‘A. One went to Kona, and the other to Honolulu, creating an inter-island rivalry. Summer regattas for sprint competitions and associations of canoe clubs to manage the contests were created on all major Hawaiian Islands. In 1933, a 40-foot, 400-pound canoe named Mālia (Hawaiian for peaceful) was crafted out of blonde koa wood by Kona boat builder James Takeo Yamasaki. It was the culmination of Hawaiian racing canoe design. In 1952, after A.E. “Toots” Minvielle of the Waikīkī Surf Club created the Moloka‘i Hoe race, which traverses the Ka‘iwi channel between Moloka‘i and O‘ahu, Mālia’s dimensions became the standard for the competition. Minvielle brought the canoe to California for the first Catalina to Newport Beach race in 1959. Before the canoe was packed on a barge and set for home, California paddlers made a mold of Mālia, and fleets of Hawaiian-style, California-built canoes were crafted from fiberglass and shipped to destinations around the world.

A parallel history occurred in Tahiti, where sprint races for youth and adults date to before Western contact and were integrated into Bastille Day celebrations by the French colonial government. Tahitian paddlers didn’t attempt inter-island races until teams from the villages of Tautira and Pirae competed in the Moloka‘i Hoe in 1977. Te Tahitian crews applied an alternate logic for this race, treating it as a series of all-out sprints rather than

a journey to be survived. Teir ferocity sparked an international revival and coincided with the Hawaiian Renaissance, when Hawaiian culture and political power emerged from a near century of dormancy. Hōkūle‘a, a replica of a wa‘a kaulua, or deep-sea voyaging canoe, was built by the Polynesian Voyaging Society. New canoe clubs joined venerable ones. Long-distance races were organized in California, New York, Japan, New Zealand, and exploded throughout French Polynesia, where races are covered on local television the way football is in the United States. Te reasons for Tahitian dominance are multiple: Children learn the sport earlier at little to no cost (one-man canoes are nearly as common as bicycles), have more options to enjoy the sport through school programs, train harder, and are rewarded with decently paid jobs for being on company teams. In Tahiti, corporations got in on the action in the 1990s, creating all-star teams of blue-collar workers. Shell Va’a (representing Tahiti’s primary oil refinery), EDT (Électricité de Tahiti, the electric company), and OPT (Office des Postes et Télécommunication, the nation’s post office) became the preeminent crews in the now international sport.

In the last decade, Hawaiian teams have been attempting to catch up. It has been the era of the Great Hawaiian Hope: Local beer company Primo fielded a crew based out of Honolulu, and venerable teams Outrigger, Lanikai, and Hui Nalu instituted rigorous training programs. “We were trying to change the local mindset about paddling, paying for guys to compete the same way the corporations do in Tahiti,” Nakachi says. Seth Koppes, a paddler in his 40s

and a friend of bicycling superstar Lance Armstrong, facilitated a sponsorship by the famous athlete that led to the development of a warehouse and gym in an industrial park near the Kona airport. Te team born of this, LiveStrong, became a competitive force: In their second year, they won second place in the masters division of the Moloka‘i Hoe. In 2012, after the controversy about Armstrong’s steroid use went public, the team changed their name to Mellow Johnny’s, the name of Armstrong’s Austin, Texas bicycle shop, and a homophone to the French “maillot jaune,” or yellow jersey, like the one worn by the winners of a stage of the Tour de France since 1919. A veritable who’s who of Tahitian paddling coaches, including Gerard Teiva, Mario Cowan, Tibert Lussia’a, and Jean Louis Urima, have coached the athletes from Kona for months at a time.

Much of the speed of Kona’s paddlers has to do with the town itself, which offers a slow place for its fast watermen. Historically a site of Hawaiian political power and missionary influence, Kona is an odd mash-up of ancient and modern. Te Ironman Triathlon has been held in the town since 1982, and a steady stream of wealth has followed. Like the south shores of Maui, Kaua‘i, and O‘ahu, the town has become a destination for the global 1 percent. It’s not uncommon for a new Tesla to pull up next to a beat-up Toyota pickup at an intersection. In addition to skyrocketing property values, wealth has brought new conceptions of athleticism. Next to the LiveStrong gym is the build shop of Pure Paddles, run by 27-year-old Odie Sumi, whose technology-driven paddles and canoes are in high demand by

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

In the canoe, speed is gained through the appropriate application of technique and focus, of blending with the team and the vessel.

“Most of these guys are beach boys or laborers or work with their families. That doesn’t mean they can’t be strong too,” says Ikaika

Hauanio, the paddling team’s de facto captain.

competitive clubs. Te gym has everything a paddler needs to make one’s neck disappear in muscles. In Kona, there are few other distractions for guys in their 20s and 30s. “We can train here because there’s just not much to do,” says Ikaika Hauanio, the team’s de facto captain, after a 6 a.m. workout. “Most of these guys are beach boys or laborers or work with their families. Tat doesn’t mean they can’t be strong too.” Hauanio is something of an exception. In amazing shape for his 40s, he’s a wealth manager at the regional Merrill Lynch branch.

Last year, the Mellow Johnny’s shop decided to lend support only to the masters team, leaving the younger members of the crew, the fastest paddlers in Hawai‘i, on their own. Tey are now under the moniker Na Koa O Kona. Nakachi’s oceanic adventuring company, Aloha Dive, which offers private tours and caters to global elite who have chosen Kona to vacation at, has acted as a resource. In 2012, Nakachi and others created the Olamau, a three-day race that traverses the northern coast of Hawai‘i Island, and is the Hawaiian answer to the Hawaiki Nui. It was the first race in Hawai‘i without any restrictions on canoe dimensions. Hawai‘i’s paddlers were

ready, and Nakachi came through: When Team Primo took top honors, they were presented with a $20,000 check. By the second running of the race, in 2013, Shell Va’a traveled from Papeete to compete, and won. Mellow Johnny’s took a close third behind EDT, the guys from the Tahitian electric company. Based on their success at the state championships and recent races, they are still considered the fastest team in the islands. “Tere are so many people that want to see this program succeed,” Nakachi says. “We’ve done it all by committee, and we’re organizing a load of sponsors and, frankly, wealthy individuals who think the sport should be perpetuated to keep it alive.”

F rom afar, paddling can be mad boring to watch. But the perspective in the canoe is entirely different. It’s one of focused labor. Time contracts to the rate of the stroke, and stretches to the expanse of the ocean. Most of what I know about the Pacific— the peoples of Oceania and the ocean itself—I know from experiences in and around canoes. Te pre-Western contact ‘Ōlelo No‘eau, the book of ubiquitous proverbs of Hawai‘i—which includes

sayings like, “Pupukahi i holomua” (unite to move forward), or “E lauhoe mai na wa‘a; i ke ka, i ka hoe; i ka hoe, i ke ka; pae aku i ka ‘āina” (Paddle together, bail, paddle; paddle, bail; paddle towards the land)—makes sense only when you’re stuck with five sort-of friends trying to get back to the parking lot without flipping and being eaten by a shark after a buoy sprint. Having never considered myself an athlete, I surprised myself by pushing the pace in the “stroker” seat at the front of the canoe during long-distance races. A decent stroker gets a malevolent satisfaction in his crew’s heaves and curses, a masochistic enjoyment when lungs and arms catch fire. I’ve often thought of the quote attributed to runner Steve Prefontaine that goes, “Te only good pace is suicide pace, and today’s a good day to die.”

It’s in this seat that I’ve felt most alive. Tere’s no greater feeling than a suicide sprint to match a wave’s speed off the stern, when the canoe becomes weightless, and labor is rewarded with a surf. It’s the ideal sport for the introverted. Long distance paddling has the same enjoyable loneliness and exertion of long distance writing: solitude within a team, helping without exchanging a ball or words. My canoe club, Ānuenue, created by the famous Joseph

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 55

“Nappy” Napoleon, who has competed in the Moloka‘i Hoe 57 consecutive times, is a club for writers. Tis has included Peter “Doc” Caldwell, who authored a history of the Moloka‘i Hoe; English professor Lisa Linn Kanae, who penned the magnificent short stories of Islands Linked by Ocean; and the late Tommy Holmes, one of the three founding members of the Polynesian Voyaging Society, who wrote the comprehensive Te Hawaiian Canoe. In 1993, Holmes died of a heart attack while paddling a course I know well. In other sports, athletes apply overt aggression or try to steal something. In the canoe, a winning strategy is to ignore the competition. Speed is gained through the appropriate application of technique and focus, of blending with each other and the canoe, of reaching further towards the horizon to pull the destination closer. From the front of the canoe, this feels like freedom.

Tere are many fine waters on which to paddle, but few can compete with the beauty offshore of the Keauhou Boat Ramp on Kona’s south end, where Na Koa O Kona practices. From park benches on a grassy slope, one can see the setting sun

flanked between the narrow bay’s stone walls and docked boats fronting a resort. At day’s end, Kona’s oppressive, still haze gives way to an explosion of Technicolor flash. Te place feels regal. If I wasn’t shown a plaque commemorating the site as the birthplace of Kamehameha III, I might have guessed it myself.

Tere are enough paddlers for three full canoes at the day’s practice, and I’m invited to sit in the canoe Tanoai is steering. As a steersman, Tanoai is a positive motivator, becoming alive when contacting water. “Straight out for eight minutes, then eightminute sprints,” he and Chun agree as we push past the harbor. We never settle to a dull rhythm; there’s no time to catch a full breath or acknowledge pain. Tanoai’s intensity pushes paddlers to constantly change their pace to exploit the subtle current, backwash, and side waves that pass under the bow. Just as we set into a pace, he exclaims, “Tis one! Catch it, don’t lose control!” and soon we’re killing ourselves, but beating the other canoes.

Back at the boat harbor, after retiring the canoes for the night, the team discusses next week’s training in preparation for

the upcoming sprint championships and the long distance season: more weights, more running, longer practices. No one complains. Outrigger paddling continues to grow in Hawai‘i and around the world, with new clubs, and new and recurring races like the 2016 Olomau. Tere is even talk of it becoming an Olympic sport. One day, this Kona crew may beat their South Pacific counterparts. Like those athletes, they live in provincial Oceania, and compete in a sport that originated in indigenous culture and has since been shared with the world. I have the urge to linger in Kona, to meet the crew before dawn for a run, and in the afternoon for sprints. To not speak a word while reaching our arms farther, pushing for the elusive horizon.

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“We were trying to change the local mindset about paddling,” says Mike Nakachi, the team’s de facto promoter and coordinator, shown here at Na Koa O Kona’s timed trials.

HARPOONS IN THE DEEP BLUE HAYSTACK

ASSESSING THE WRECKAGE WHERE MOBY - DICK AND HAWAI‘I COLLIDE.

TEXT BY TRAVIS HANCOCK | UNDERWATER IMAGES COURTESY OF NOAA

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Maritime archaeologist Kelly Gleason Keogh investigates a double flued whaling harpoon tip at the Two Brothers shipwreck site at French Frigate Shoals. Image by Greg McFall and courtesy of NOAA.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 59

In 1901, the Bernice Pauahi Bishop Museum bought a sperm whale skeleton from naturalist Henry Augustus Ward’s collection in Rochester, New York for $2,500. Te purchase effectively repatriated the whale’s bones to the Pacific, and they’ve been hanging high and dry in the museum’s Hawaiian Hall, half-concealed in papiermâché, ever since. L ike the squid and the whale exhibit in the American Museum of Natural History’s Hall of Ocean Life, Bishop Museum’s prestigious acquisition played a major role in telling the story of life in the Pacific.

Ten, the museum’s director, William T. Brigham, implicated the specimen in a particularly human facet of that story by making it the symbolic victim of 19th century whalers. In his 1902 report to the museum trustees, he wrote, “As Honolulu was built up largely by the whaling industry, it seemed desirable to recall to the memory of its present inhabitants the implements of that pursuit, once so familiar here.” Brigham was delighted to report that the museum received whaling tools from collectors in New Bedford, Massachusetts that year (simultaneously, the eminent director bemoaned the museum’s failure to amass a comprehensive skeletal collection of “the backwards peoples of the Pacific Ocean,” revealing a certain backwardness of his own by likening living, native makers of Pacific history—including whaling—to bygone artifacts).

Today, the New Bedford Whaling Museum also displays a sperm whale skeleton, as does the Nantucket Whaling Museum, and the Whalers Village Museum in Lāhainā on Maui. Daily visitors to these sites, thousands of miles apart, unknowingly observe this common thread—one that echoes an earlier connection between these distant spaces. Within the past 200 years alone, people on both sides of the continent have simultaneously revered these sperm whales, or palaoa, as sacred ‘aumākua, or ancestors; as bounties of oil and spermaceti wax; as scientific specimens; as symbols of mammalian evolution, barbaric industry, and nature’s resilience. Behind these brief descriptive labels, each creature in this floating community of bones tells a complex story of interconnectivity, and carries a legacy of leviathan proportions

that is still very much with us today, if sometimes forgotten. In order to interpret those stories—and the legacy of whaling in Hawai‘i—we must dive back in time.

RED SKY AT MORNING

On a stormy winter day in February 1823, three whalers from the tiny New England island of Nantucket staggered windswept and bedraggled from the whaleship Martha onto the dusty streets of Honolulu. Tey were Captain George Pollard Jr. and teenagers Charles Ramsdell and Tomas Nickerson. Te Honolulu they laid eyes on was a hodgepodge of huts and coralblock buildings, the latter of which were built by the Boston missionaries, who had arrived just three years prior. But the port town was developing swiftly, and the sheltered bay—the Hawaiian meaning of “Honolulu”—readily offered harbor to a growing number of whaleships carrying foreigners on the hunt for either blubber or unsaved souls.

According to young Nickerson’s account, the Martha left him and his mates in Honolulu, where a fleet of whaleships was in port, and “each took their own course and joined separate ships as Chances offered.” In fact they had never planned to sail with the Martha or set foot on O‘ahu, though “chance”—a disturbingly powerful force in the whaling life—had a lot to do with Nickerson and his mates arriving there. In the week prior, the three men had survived their second open-ocean shipwreck in three years.

Te first of the wrecks was that of the whaleship Essex, demolished in an infamous sperm whale attack—a tale that flooded New England’s shores, and eventually reached the ears of a young literary whaler named Herman Melville, inspiring him to write Moby-Dick in 1851. Te Essex disaster took place on the morning of November 20, 1820, as the ship’s smaller whaleboats were pursuing a pod of whales across the deep waters far west of the Galapagos Islands. Amid the scramble, a very confused or very angry (science and literature disagree here) bull sperm whale veered around and torpedoed itself through the timbers of the Essex’s bow. Pollard, Ramsdell, Nickerson, and the rest of the crew made their escape in the whaleboats—just like the sailor we

call Ishmael would escape the wreck of the Pequod. But where Melville ended his tale, the real drama began for Pollard and his crew. In the 95 days following the wreck, the men took tragic recourse to the marrowsucking depths of cannibalism in order to sustain a meager few until they reached the shores of Patagonia.

In 2000, author Nathaniel Philbrick brought this harrowing journey to light with his bestseller In the Heart of the Sea, which brilliantly synthesizes the accounts by Pollard, the heroic first mate Owen Chase, and Nickerson, whose wilting manuscripts, forgotten since the 1870s, were rediscovered in a New York attic in 1960 and finally published in 1984. In Philbrick’s assessment, it was the strength of community, notably the intimate bond of the white Nantucketers, that delivered eight of 21 Essex crewmembers back to their tiny island home in the Atlantic, the opulent dispatch center of American whaling during the Industrial Revolution.

One year to the day after the Essex was wrecked, and only a month after reaching Nantucket, survivors Nickerson and Ramsdell again sailed away from the island with Captain Pollard, who was now at the helm of the Two Brothers—one of the ships that had aided their journey home. After rounding Cape Horn, the Two Brothers sailed north with fellow Nantucket whaleship Martha for a cruise into the fertile Hawaiian whaling grounds, en route to the whale-rich waters off Japan. One night, as they passed the French Frigate Shoals between Kaua‘i and Midway Island, a blinding storm rolled in. Only the Martha made it out. A 19th-century poem believed to have been written by Nickerson captures the terrors that befell the Two Brothers: “Hold, hold she strikes, upon her side she reels / And each successive shock, the truth reveals / Her groaning timbers can no more withstand / Te bursting sides proclaims her fate at hand.”

Te Two Brothers broke in half, scattering its wooden planks and iron equipment across what we today call Shark Island, which is now no more than a swath of eroded reefs and a small kidney-shaped plot of sand some 400 miles northwest of Ni‘ihau. When visibility returned at dawn, the Martha scooped the ill-starred men from their trusty whaleboats.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Kelly Gleason Keogh, who leads the team that discovered the Two Brothers shipwreck, measures a grinding wheel, used to sharpen tools, at the French Frigate Shoals.

Image by Derek Smith and courtesy of NOAA.

Kelly Gleason Keogh, who leads the team that discovered the Two Brothers shipwreck, measures a grinding wheel, used to sharpen tools, at the French Frigate Shoals.

Image by Derek Smith and courtesy of NOAA.

Herman Melville would pick up the Nantucketers’ fading trail in Honolulu some 20 years later, following his own seafaring adventures aboard whaling ships and naval vessels through the Marquesas Islands, Tahiti, and Hawai‘i—trips that informed his popular early travel novels. During a trip to Nantucket later in life, Melville finally found George Pollard, who was working as a humble night watchman. Deeply impressed by the encounter, Melville sketched Pollard in his last major work, the epic poem Clarel: “Patient he was, he none withstood; / Oft on some secret thing would brood.”

In December 2015, the modern American masses will meet Pollard and his crew in Ron Howard’s cinematic rendition of In the Heart of the Sea, starring Chris Hemsworth, Cillian Murphy, and Brendan Gleeson. And although the film will focus on the Essex story, people in these islands are quickly gaining ways to trace the epilogue right back to Hawaiian waters.

EUREKA

It’s 2008, and Kelly Gleason Keogh, Ph.D., is in the warm waters off the Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument, which encompasses the Northwest Hawaiian Islands, including its largest atoll, the French Frigate Shoals. For this routine survey dive, Keogh is towboarding, clinging to a plank connected to a motorboat. With another diver at her side, Keogh glides just below the surface at about two knots, “a speed at which your mask isn’t gonna go flying off your face, but faster than you’d be able to kick,” she says. Ten she spots something glaringly out of place: a large coral-crusted anchor protruding from the reef. She lets go of her towboard and gazes down. As a maritime archaeologist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the maritime heritage coordinator of Papahānaumokuākea, Keogh knows that only something big and very old could have

left that anchor. She and her dive team scan the coral beds for more clues: iron, ceramics, anything vaguely geometric. Ten, up from the reef rise four try-pots, enormous cauldrons that were once used for rendering oil from blubber. Tese telltale relics can only mean an early whaling ship. Finally, Keogh swims down and plucks a harpoon tip from the reef, a fragment that will reveal itself to be a traceable tip of the invisible iceberg-like Two Brothers. Originally from the sunny shores of Santa Barbara, the bubbly blonde and razor-sharp Keogh studied the humanities as an undergraduate, immersing herself in the pages of books like Moby-Dick. Nowadays, after receiving her master’s degree in nautical archaeology and Ph.D. in coastal resource management and maritime history, she salvages the lost stories of early whalers and WWII pilots alike from one of the world’s largest marine protected areas. But finding anything in the vast 140,000-square-mile zone requires an eclectic repertoire of skills.

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Nickerson’s Essex sketch with whale, MS106-3. Courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association.

Like the iron and bone circulating through our nation’s museums, the ideas that whaling first introduced to the islands have now come full circle; but unlike the artifacts, these notions never really went below the surface.

It takes a mixture of deep archival digging and miles of shallow-water swimming over “parts of the reef that people usually don’t want to go to,” Keogh explains, a week after her return from yet another research trip to Nantucket in late July.

Because NOAA ships are only allotted about a month at a time within the highly protected marine area, and are spread thin between the needs of various scientists and researchers, Keogh has only had brief windows to excavate the Two Brothers following their initial discoveries. “We went back again in 2009, and that’s when we started to find more whaling tools, like harpoon tips,” she says. “And we went back in 2010 and accumulated enough of an artifact inventory that we could connect it with the ship Two Brothers sailing from Nantucket in the 1820s.” It’s the first Nantucket whaler anyone has ever found.

Keogh and her team made the official announcement in February 2011, 188 years after Pollard, Nickerson, and Ramsdell were forced to abandon ship. Te dozens of discovered artifacts, many of which are currently on loan for an exhibit at the Nantucket Whaling Museum, include harpoon tips, whaling lances, blubber hooks, ceramics, glass, cooking pots, and a wonderfully preserved ginger jar. In 2017, all the objects will be reunited in Hawai‘i, where they will find a permanent home at the Mokupāpapa Discovery Center in Hilo. By that time, there could be many more pieces joining them—half of the ship is still missing. Keogh returned to the wreck site in 2014, and again in the fall of 2015, to

continue searching for the bow section, as well as to hunt down campsites reportedly set up by survivors of other wrecks on the tiny islands within the monument. Te Two Brothers is the fifth whaleship to be found of a total of 10 known vessels to have sunk in the region.

OPPORTUNITY KNOCKS UPON THE SHORE

Maritime archaeologists know that the constellatory portraits their discoveries piece together aren’t always pretty. But creaky wooden ships sailing across 5,000 miles meant business. Te ship was a miniature company, with its stock divided into shares among the owners and crew. At whaling’s peak in the mid-19th century, a full haul could make the top shareholders millions. But the artifacts strewn across Hawaiian reefs often conjure up the grisly tasks that made each trip worthwhile: plunging iron lances into sophisticated marine mammals, fishing their gargantuan corpses from bloodied waters, and rendering oil from blubber, which sent pungent plumes of black smoke into the bright sky. It’s not surprising that Melville cast its practitioners in a hellish light. One night as the Pequod’s furnaces burned, he wrote in Moby-Dick, the “ship drove on, as if remorselessly commissioned to some vengeful deed,” while the “Tartarean shapes of the pagan harpooners ... with huge pronged poles … pitched hissing masses of blubber into the scalding pots.” Minus the infernal metaphors, that was real life work in a much different time. And in fact, whaling didn’t

always involve foreign outsiders entering hallowed Pacific spaces, draining them of natural resources, and occasionally leaving men and bits of iron behind. “A number of early businessmen were involved with whaling and owned whaleships under the Hawaiian flag,” maritime archaeologist and University of Hawai‘i anthropology lecturer Dr. Suzanne Finney explains over email while visiting her childhood home near New Bedford. Finney’s ongoing research focuses on the C.S.S. Shenandoah, a Confederate States Navy ship tasked with disrupting Union commerce, which included whaling, during the Civil War.

“[We were] searching underwater in pretty low visibility, when all of a sudden we saw what looked like a row of spikes sticking out of the wall of the harbor,” she recalls. “We were so excited! Tey were the remains of one of the hulls of the whaleships.” In total, Finney has documented four of the whaleships that the Shenandoah burned in 1865 around Pohnpei, Micronesia. One of them, the Harvest, was owned by a German immigrant to Hawai‘i named Heinrich Hackfeld, whose dry goods store evolved into the land developer American Factors, or Amfac, Inc., one of Hawai‘i’s “Big Five” early businesses. But big business owners, not to mention Hawaiian royals, represent merely the top of the pyramid. Whaleships spent a lot of time in port at Honolulu and Lāhainā, waiting on repairs, offloading oil, restocking their provisions, or waiting for spring to thaw the whale-rich Arctic. During the wait, men flowed in and out with the tides. New families were born, and others were broken apart.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Keogh documents a large anchor discovered at the Two Brothers shipwreck site at the French Frigate Shoals.

Image by Tane Casserley and courtesy of NOAA.

Keogh documents a large anchor discovered at the Two Brothers shipwreck site at the French Frigate Shoals.

Image by Tane Casserley and courtesy of NOAA.

“So many Hawaiians signed on to whaleships, that a big part of the intangible history is the movement of Hawaiians around the world, including the settling of Hawaiians in different places,” Finney says. “When the number of Hawaiians signing on to whaleships escalated ... the government ended up placing a bond on every Hawaiian sailor shipped, so that if the ship didn’t bring them back to Hawai‘i, they would lose the money.”

Tis migration of Hawaiians was so great that Susan Lebo, archaeology branch chief at the Hawai‘i State Historic Preservation Division, wrote an essay in 2007 titled “Native Hawaiian Whalers in Nantucket, 1820-60.” Her extensive archival research uncovered the paths of countless Hawaiians—renamed “George, Jack, Joe, or Tom Canacker, Kanaka, Mowee, or Woahoo”—who successfully integrated into Nantucket society, finding their ways into local schools and businesses, not to mention every station offered aboard the whaleship. “Tese whalers,” Lebo writes, “on countless … Nantucket voyages with Hawaiian crews, contributed to the economic and social

history of this small island community. Tey shared their cultural traditions, languages, skills, and knowledge with Nantucket’s citizens and with each other aboard the island’s whaleships.”