DISPLAY UNTIL APRIL 30, 2016 SPRING 2016 THE COMPANIONS ISSUE HOME ON THE RANGE IN DOG WE TRUST THE HUMAN BOND

36

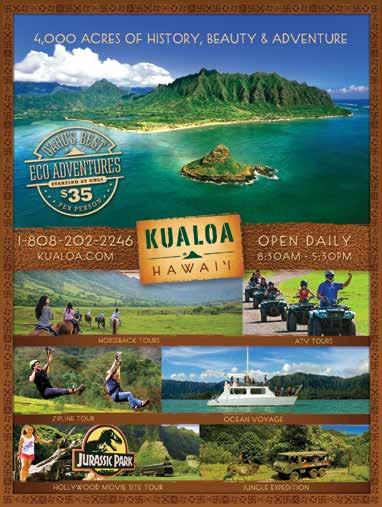

HOME ON THE RANGE

In Upcountry Maui, there is a contemporary paniolo community with traits influenced by Hawai‘i’s cowboy history. Appropriately, it also has its fair share of horses. Managing editor Anna Harmon wrangles up three paniolo and the working companions they ride.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES |

46

IN DOG WE TRUST

Te bond between service animals from Hawaii Fi-Do and the individuals who own them is transformative. Editor Lisa Yamada takes a look at how the first service dog training organization in the state is helping individuals get back on their feet.

54

BEHIND THE WHEEL

Nonprofits in Hawai‘i remain the last, best hope for an equitable society. Editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden examines two organizations providing a community of care to those who need it most.

The relationship between caregiver Lourdes Vivar Noble and client Jean Yamada is predicated on assertiveness and wit, and is solidified by a mutual care for one another.

62

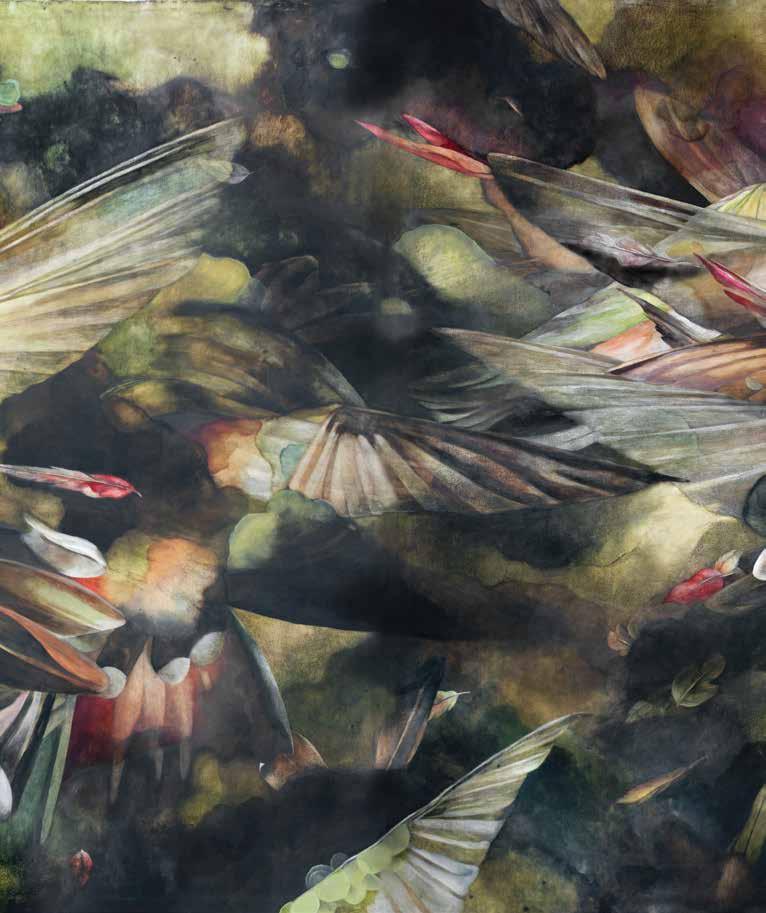

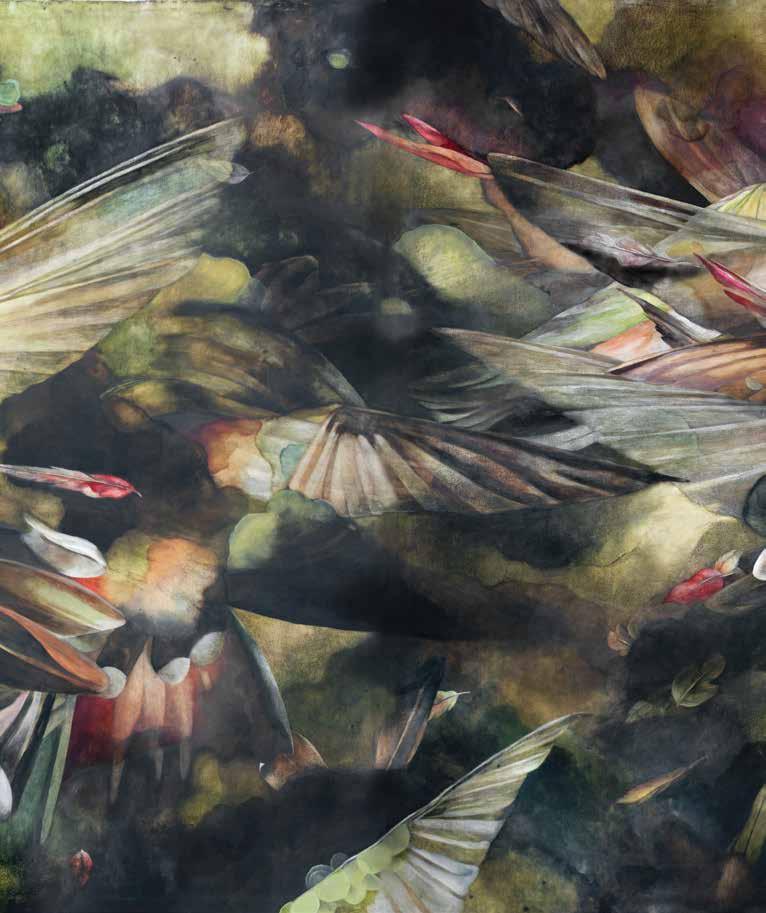

SHARING A SOUL

Society mines the lives of twins for greater meaning. But what meaning can be gleaned when one dies? When artist Emily McIlroy’s twin brother passed away at the age of 24, she lost half of herself. Contributing writer Martha Cheng outlines how she has coped.

68

THE HUMAN BOND

Humans are relational beings, shaped as much by their environments as by those with whom they spend their time. Tese four portraits depict what happens when paths align.

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Jennifer Kushi and her Rottweiler, Cocoa, are both owner and pet and a canine-handler team with Maui Search and Rescue.

to explore their creativity.

Lisa Shiroma’s paintings capture the twinkle in an animal’s eyes. “They are the most important part of the painting,” she says.

REVIEW: ALOHA, LADY BLUE

EDITOR’S LETTER CONTRIBUTORS LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 23 WHAT THE FLUX?! ANIMAL OVERPOPULATION 26 LOCAL MOCO KUSHI AND

FLUX PHILES 30 ART: SALLY

34 ART:

IN FLUX 80

86

COCOA

FRENCH

LISA SHIROMA

TRAVEL: WITNESS TO THE WONDER

A HUI HOU 96 THE NEXT CHAPTER 10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Sally French double dog dares artists

#FLUXBESTIE

THE PUPPIES!

Go behind the scenes of a Hawaii Fi-Do service dog training session in the busy heart of Kailua town. Shown here is 6-monthold Danno, dog number 14 for puppy raiser Mitch Gowan. Tese accredited volunteers, who ready the pups for lives of service, are the heart and soul of Hawaii Fi-Do. Over two years, they train the dogs to recognize upwards of 90 commands. Watch the puppies navigate through kids, crowds, cars, and even a rooster.

POST FOR PAWS! EVERY #FLUXBESTIE POST RAISES FUNDS FOR HAWAII FI - DO.

For this companion-themed contest, post a selfie with you and your bestie, be it four-legged or two, on Instagram, Facebook, or Twitter and tag @fluxhawaii @hawaiifido #fluxbestie. For every unique post, FLUX Hawaii will donate $1 to Hawaii Fi-Do (read about the service dog training organization on page 46). Contest runs from February 29 to March 7, 2016. Photos must be posted during this time, with these tags in the original caption.

ON THE COVER:

Shown on the cover is 15-yearold Caysie Madeiros, who, in 2014, became the youngest to win the All-Around Cowgirl title at the 4th of July Makawao Rodeo—Maui’s largest— competing against women four times her age. “Tat was all because of him, too,” she says about her buckskin horse, Bucky, also on the cover, who she calls Bullet because of his speed.

IMAGE SHOT BY JOHN HOOK.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE

| FLUXHAWAII.COM |

OF CONTENTS

Humans have a funny way of talking to their four-legged friends. We dote on them, speaking in voices both gooey and stern, as if they are children who should know better. We ask them questions and expect an answer. “Who did that?” we scold in anger. A pet’s over-the-shoulder glance is a sure sign of guilt. “Who’s a good boy?” A lolling tongue teases as if to say, “I am!”

You might have guessed that I am a dog person. Tis, despite the fact that in one of those online “Are You a Dog or Cat Person” tests, I came out as a cat person. (“You’re highly intelligent, witty, and, contrary to popular belief, no less loyal and fun-loving than your dog-people counterparts,” the results told me.) But I am decidedly dog. Contrary to the whole stereotype about ladies being the lovers of cats, my fiancé is the one with a soft spot for our cat, Bubba, a tuxedo tabby we inherited after my niece went off to college.

It’s true that animals can meaningfully impact our lives. Tey guide us, work with us, and bring us joy. But as significant as the relationships are that we have with the animals we love, they are but fleeting moments in the spans of our lifetimes.

Human relationships, for that matter, may be even more momentary. Harvard entomologist E.O. Wilson calls the age we are living in the Eremocene, the Age of Loneliness. More Americans are living alone than ever before, and while technology has expanded the breadth of our online networks, it has also contracted the depth of our physical ones. In the last two decades, the average number of confidants an individual may entrust dropped from three to one.

But social connection is good for you. As shared in this issue, it keeps you active, sane, and healthy. If you haven’t been lucky enough to find a significant bond like this, whether with a human or a furry friend, you might start by looking at your local animal shelter. Tere, many have discovered how the most enduring company is the kind that strengthens yet humbles; that allows you to to realize the best version of yourself; that loves you even when you do not. I consider myself lucky to have found two such companions: one with a frizzy tail and fluffy head that will, in the foreseeable future, pass on; the other with strong shoulders to lean on even after the last tear has been shed.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada Editor lisa@nellamediagroup.com

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM EDITOR’S LETTER | COMPANIONS |

WE FOSTERED THIS STRAY KITTY FOR A DAY AT THE FLUX HAWAII OFFICE. WHY DIDN’T ANYONE TAKE HER HOME?

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

“My other cat said no.”

“My place doesn’t allow pets.”

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNER

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR - AT - LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Beau Flemister

Bryce Johnson

Jonas Maon

MASTHEAD

COMPANIONS

CONTRIBUTORS

Katie Caldwell

Martha Cheng

Matthew Dekneef

Beau Flemister

Kelli Gratz

Rebecca Pike

Coco Zingaro

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns

MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Carrie Shuler

MARKETING & CREATIVE COORDINATOR

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Mitchell Fong JUNIOR DESIGNER

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

“I’m allergic.”

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

“Not yet ready for another cat.”

©2009-2016 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

|

|

CONTRIBUTORS | COMPANIONS |

MARTHA CHENG

Martha Cheng is a freelance writer and editor who usually writes about food, but sometimes she is intrigued by other topics, too. She was particularly interested in the specifics of Emily McIlroy’s story of twin loss on page 62—what it feels like to lose a twin and how to heal after the death of a companion you thought you would spend the rest of your life with. Te hardest part of writing the story: being an only child trying to understand what it’s like to have a twin. Find more of Cheng’s writing at curiousmartha.com.

BEAU FLEMISTER

Kailua-born Beau Flemister is the editor-at-large of Surfing Magazine. Having completed his first novel, In the Seat of a Stranger’s Car, he is now traveling around the world with his wife, Rachel, a journey he documents in “Witness to the Wonder” on page 80. “Te most challenging part about writing this story was not sounding like a complete douchebag, which is hard not to when you’re talking about world travel,” says Beau, who has contributed to VICE and Outside magazine. “Honestly, when I hear someone start a sentence with, ‘Last year in Italy we …’ I automatically tune out.” Catch up on Beau’s adventures (if you can stand it) at planestrainsballandchains.com or on Instagram @planestrainsballandchains

REBECCA PIKE

Born and raised in New York City, Rebecca Pike made her way to Honolulu in 2007 and has been writing about unique experiences for both visitor and local readers ever since. She did so on page 68 with her vignettes of Ye Nguyen, a midwife, and Molly Jenkins and Mamie Lawrence Gallagher, leaders at Mo‘O School, where Pike’s 4-year-old daughter is part of its first cohorts. “All three are living lives of purpose and perpetuating peace and love through connection with others at crucial periods in their lives, be it the birth of a first child or guiding a small child through her first years of education,” she says. “It’s professional, but it’s personal, too.”

18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

For FLUX Hawaii’s recent sea-themed issue, we as ed readers to post pictures of their favorite ocean moments. elow, are a few of our favorites. ou re welcome.

To see all the entries, search #fluxocean on Instagram.

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

WE WELCOME AND VALUE YOUR FEEDBACK. SEND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO: LISA NELLAMEDIAGROUP.COM OR MAIL TO FLUX HAWAII, 36 N. HOTEL ST., SUITE A, HONOLULU, HI 96817 @ APECUB @ HEWENTTOJARED__ @ LYSSIELOOLOO @ THETABATAFISH @ HIGHONHAWAII @ MEEMERS3 @ VINCENTHAWAII @ JADESSTEELE @ MUDRA_LOVE @ VINCENTHAWAII @ EEVEE_R @ VISIONHORSEMEDIA

BURDEN TO BEAR

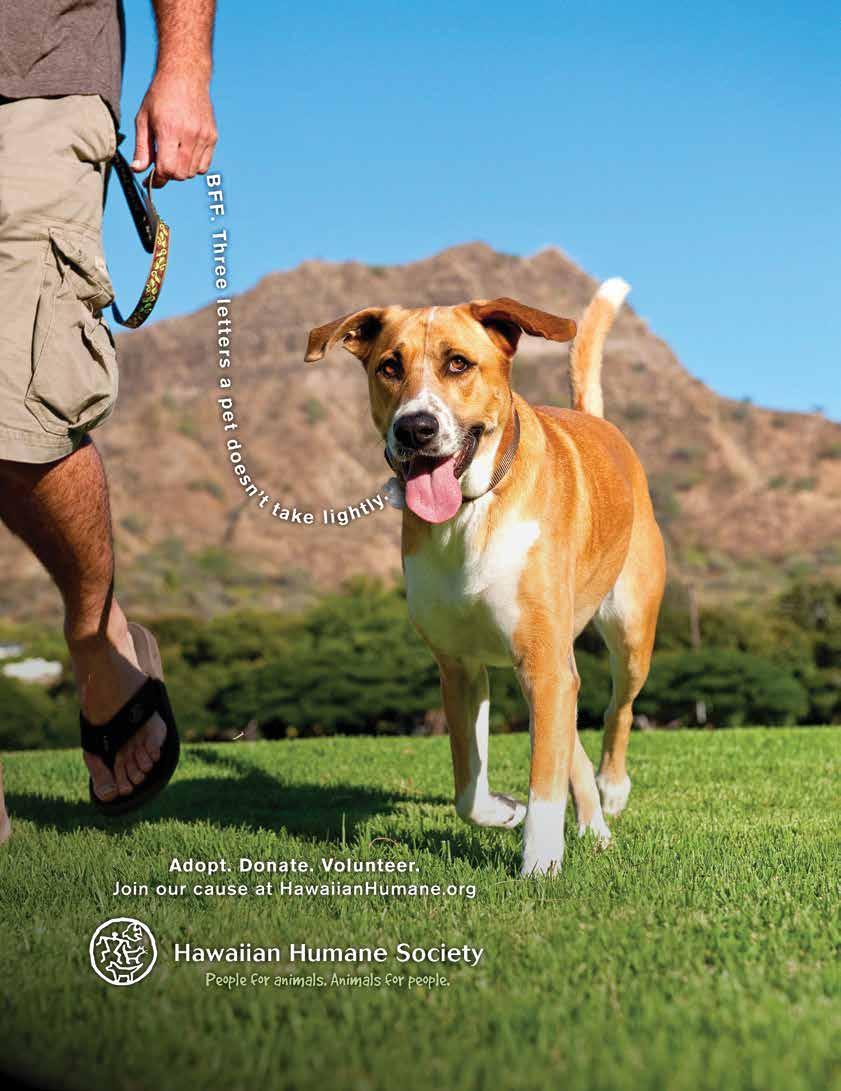

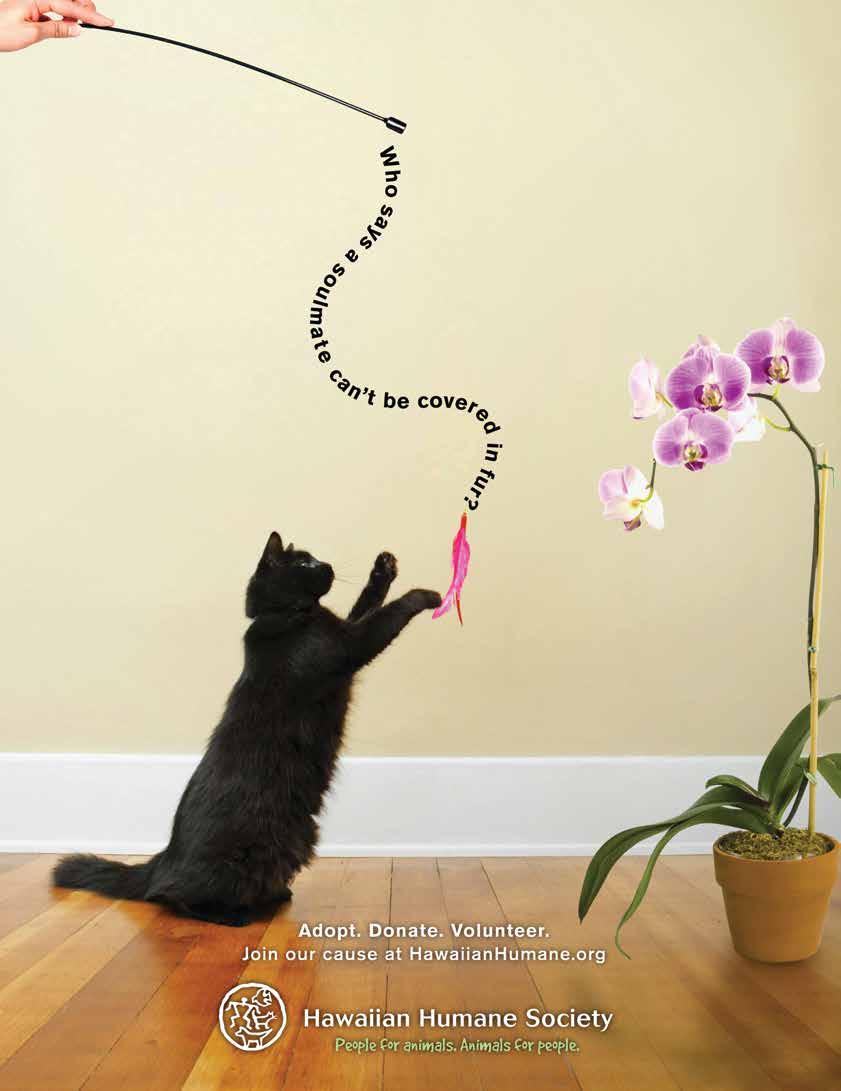

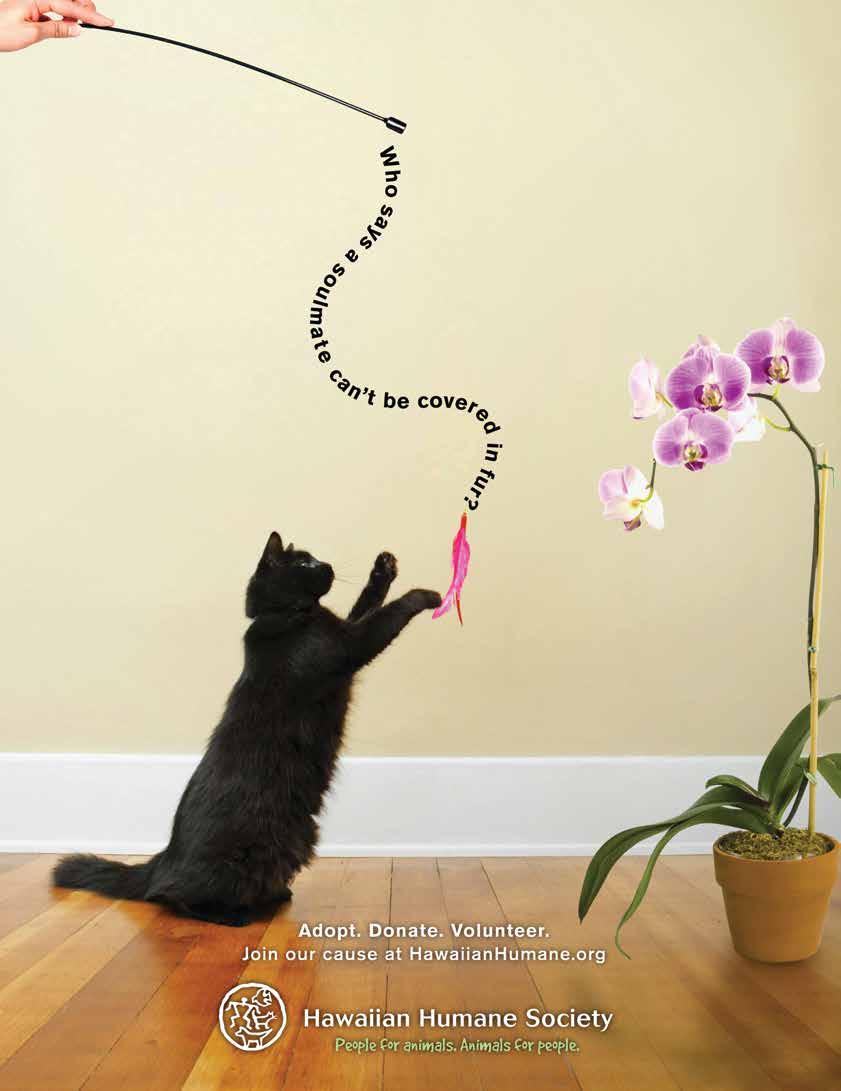

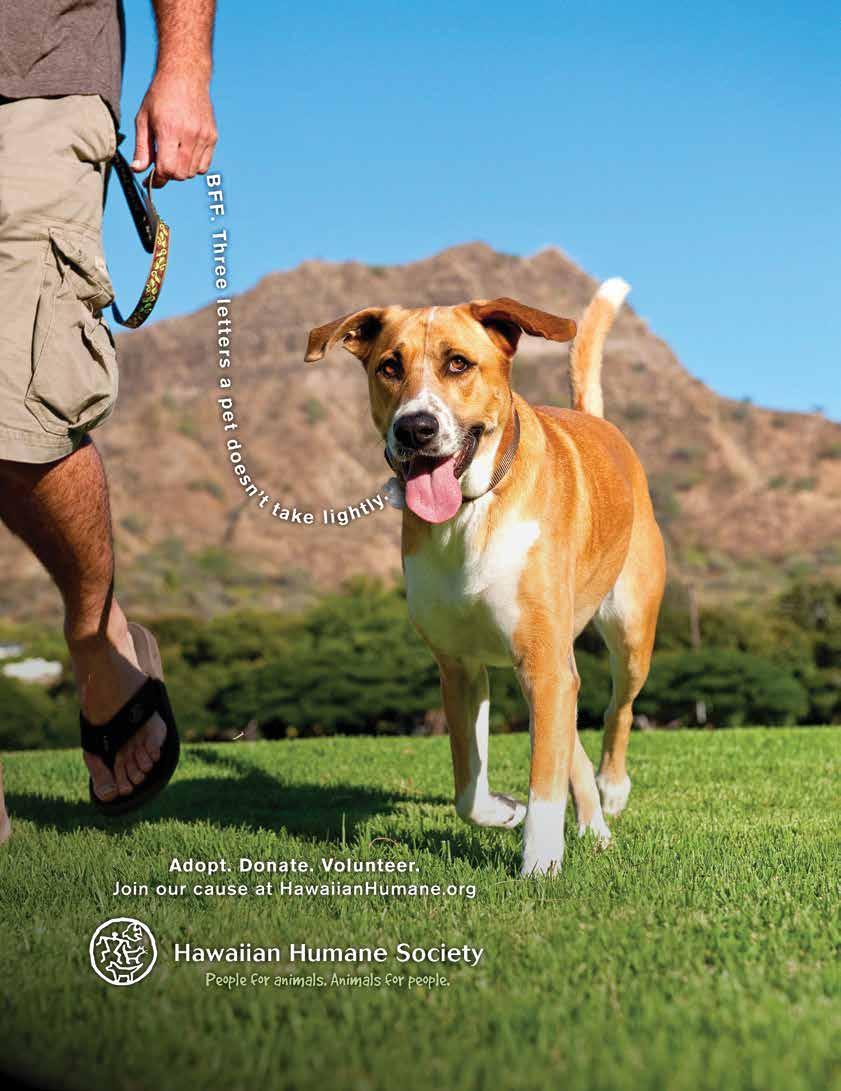

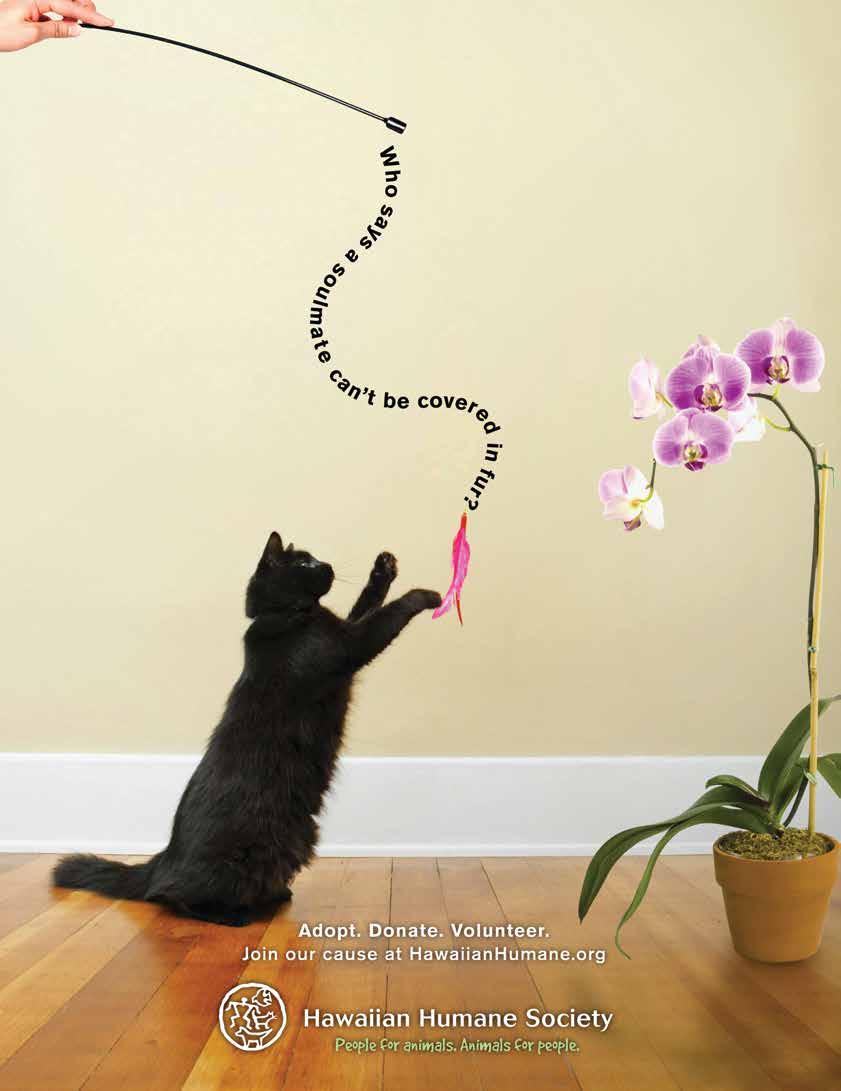

Each year, more than 7.6 million animals across the United States enter shelters. Of these, approximately 31 percent of dogs (1.2 million) and 41 percent of cats (1.4 million) are eventually euthanized. Hearing this statistic can be heartbreaking for any quadruped-loving biped, and most certainly for the estimated 60 percent of O‘ahu homeowners whose families include a pet. Although Hawai‘i’s many shelters do their best to alleviate animal overpopulation, the facilities can barely keep up: limited-admission, sometimes known as “no-kill” centers, like O‘ahu Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, may be faced with the difficult choice to turn away animals because of space, while

open-admission shelters like the Hawaiian Humane Society, which accepts 100 percent of animals regardless of condition—the only one to do so on O‘ahu—may have to euthanize animals that are deemed unadoptable due to factors like aggression or illness. As the largest animal welfare and protection charitable organization in the state, the Hawaiian Humane Society took in 23,876 animals, or 65 per day, with 31 percent adopted, in 2015. It is only when we, as a community, come together to chip away at this seemingly insurmountable problem that animal overpopulation can be put down for good.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23 WHAT THE FLUX?! | OVERPOPULATION |

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | ILLUSTRATIONS BY MICHELLE GANEKU

Reducing Animal Overpopulation:

3. SPAY AND NEUTER

An estimated 378,000 dogs and cats belong to families on O‘ahu. Nearly 30 percent, or about 113,000 of these animals are not sterilized.

1. MICROCHIP

There is a � � % increased probability of owners fnding lost pets if the animals are microchipped.

• 1 in 3 pets will get lost.

• Dogs are 2.4 times more likely to be returned to owners when microchipped. Cats are 21.4 times more likely to be returned to owners when microchipped.

In 2015, a Siamese cat named Bogie, who escaped from his carrier at the Honolulu International Airport during his family’s move to Michigan, was reunited with his owners after 19 months. Bill Antilla, a volunteer with Hawaii Cat Friends, was able to facilitate the reunion when he found Bogie in Honolulu and scanned his chip to discover that the feline’s family lived in Detroit.

2. ADOPT

If one in every fve of the Americans who are considering getting a dog or cat chose to adopt from a shelter or rescue this year, rather than buying from a breeder or pet store, euthanasia among healthy, treatable pets would be eradicated.

6 %

Percentage of O‘ahu pet owners who acquired their pets from proft-making entities rather than shelters or rescues.

• One female cat and her o fspring can theoretically produce 420,000 cats in 7 years. One female dog and her o fspring can theoretically produce 67,000 dogs in 6 years.

Only � in � � domestic cats entering animal shelters have been spayed or neutered prior.

4. TRAP, NEUTER, RETURN

Feral cat populations can be balanced by residents’ participation in a trap, neuter, and return initiative. The Hawaiian Humane Society has traps available on loan or for purchase.

�

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM WHAT THE FLUX?! | OVERPOPULATION | ��% ��%

What You Can Do

There are � ��,�� � + free-roaming cats on O‘ahu.

In order to e fectively reduce the population of feral cats on the island of O‘ahu, at least 75 percent of these 300,000 cats must be sterilized.

• Seventeen percent of O‘ahu residents report feeding cats they did not own. Of these residents, 70 percent said they didn’t know if the cat was sterilized or not.

• Only about 6,000 feral cats are sterilized annually via the e forts of Hawaiian Human Society, Hawaii Cat Friends, Hawaii Cat Foundation, and other cat advocacy groups.

5. BECOME A FOSTER PARENT

With limited space available in shelters, animals that need extra care (they may be too young, sick, or injured) or that are slow to be adopted are sometimes placed in the temporary care of volunteers. “We keep them as long as it takes to f nd them a home. There is no time limit. We foster for space when needed and need more people to choose adoption.” —Hawaiian Humane Society

� ,�� � +

Number of animals placed in foster homes by the Hawaiian Humane Society in 2015. Twenty percent of animals available for adoption have bene f ted from fostering.

6. ADVOCATE FOR MORE PET FRIENDLY HOUSING

� � %

Percentage of those who surrendered pets to shelters because their residences did not allow pets. The next most common reason cited for pet displacement was behavior issues, trailing at nine percent.

7. VOLUNTEER AT YOUR LOCAL ANIMAL RESCUE

In addition to the Hawaiian Humane Society, which is located on O‘ahu and remains the largest of such organizations in the state, there are many shelters in Hawai‘i that specialize in animal rescue:

• On O‘ahu, Poi Dogs and Popoki focuses on assisting economically disadvantaged pet owners by helping them provide their pets with safe living environments (such as installing fences to keep dogs contained rather than securing them with chains) and by o fering spay and neuter services.

• On L ā na‘i, The Lāna‘i Cat Sanctuary , which cares for about 300 cats in an open-air, 15,000-square-foot facility, was started by Kathy Carroll and Loretta Hellrung, who set out to trap and sterilize the island’s feral cat population nearly a decade ago.

• On Maui, the Maui Pitbull Rescue , the only one of its kind in the state, saves pitbulls who may be considered otherwise unadoptable due to health or aggression issues. Maui Pitbull rescues include those abandoned by breeders, deformed puppies, injured or lost hunting dogs, and bait dogs that have been dumped by dog f ghters.

• On Big Island, Three Ring Ranch o fers sanctuary to exotic animals already in the state, which has included zebras, n ē n ē, hawks, f amingos, alpaca, and others.

*Sources: American Veterinary Medical Foundation’s U.S. Pet Ownership and Demographics Sourcebook; a 2012 American Humane Association and Petsmart study on pet retention; “Understanding Oahu’s Animal Population & Community Responsibility,” published by Hawaiian Humane Society in 2013; Hawaiian Humane Society’s 2015 Annual Report; Humane Society of the United States; O‘ahu Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals; Hawaii Cat Foundation.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

“I’ve always wanted a Rottweiler because of their temperaments. I know that they’re smart,” says Jennifer Kushi, shown here with her dog, Cocoa, who she trained to detect the scent of human remains.

TOUGH LOVE

HOW

MAUI’S FIRST DOG TRAINED TO FIND HUMAN REMAINS, AND HER DETERMINED HANDLER, WORK TOGETHER.

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Jennifer Kushi has a Celtic infinity knot tattoo that runs from her ankle to her hip, where it meets a tattoo of yellow rays shining over a turbulent black ocean. Tis emblem matches that of an embroidered patch on the black harness of her dog Cocoa, a sweet 2-year-old Rottweiler. It is the logo of Maui Search and Rescue, for which Cocoa is one of two dogs trained to detect human remains.

Cocoa, who has the typical brown markings and docked tail of her breed, is both Kushi’s pet and her partner in searches for missing persons. Te two are practically inseparable, aside from the hours Kushi works as a nurse in obstetrics and gynecology or urgent care for Maui Medical Group. At night, Cocoa sleeps in a kennel, its door open, in Kushi’s room. Her four children, ages 2, 5, 6, and 8, adore the dog. “She is actually one of the biggest babies in the family,” Kushi says. In her spare time, Kushi may take Cocoa to Polipoli State Recreation Area, a cool forested space where the pair train for searches, or to meetings with Maui Search and Rescue, of which the 36-year-old is vice president. Tis all-volunteer organization consists of 50 to 80 members, with 15 to 20 who actively participate, as well as a handful of search and rescue dogs.

“I’ve always wanted a Rottweiler because of their temperaments,” says Kushi, who got Cocoa in February 2013 when she was roughly 2 months old. “I know that they’re smart.” Cocoa was the runt of the litter, picked on by her siblings but eager for love and attention. In the dog training classes that Kushi sent her to that summer, Cocoa learned common tasks such as heeling, as well as the less common one of picking up scents. Cocoa was a natural.

In February 2014, Kushi was watching the news when she learned that a loosely formed group (which would eventually become Maui Search and Rescue) was searching for missing pregnant woman Carly “Charli” Scott, and was recruiting volunteers with medical experience. Kushi decided to pitch in. After witnessing the despair and exhaustion of friends and family heading the search, she recalled the stories a former Maui pathologist she had worked with told her regarding FEMA-certified dogs that had been brought from the mainland to assist in searches. What they needed, she realized, was such a dog, which could cover as much ground as 50 human searchers.

Cocoa was a good fit for that type of task—desired traits include scenting capability, intelligence, a strong play drive, and physical stamina—so, after researching proper training procedures extensively online, Kushi began training her as a cadaver dog, which detects and tracks the scent of decaying human remains. (Maui Search and Rescue also utilizes an air-scent dog, which has a brief window of time to detect the scent of a live person.) Tey train in rural locations, where Kushi hides vertebrae and placentas in various states of decay for Cocoa to detect and locate. Te Rottweiler has developed her own way to signify when she has found something, tapping the spot before she sits beside it. She has also been trained to scent human blood, so that she can help find injured persons.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27

LOCAL MOCO | KUSHI & COCOA |

Two-year-old Rottweiler Cocoa has all the desired traits of a search and rescue dog, including scenting capability, intelligence, a strong play drive, and physical stamina.

On July 4, 2015, Kushi, Cocoa, Maui Search and Rescue president Adam Gaines, and air-scent dog Mia boarded a plane for O‘ahu to aid in the search for Justin Clark, a hiker who had been missing for nearly four days, after being contacted by his family. Despite it being the Rottweiler’s first ever flight, the large dog calmly settled under the seats in front of Kushi, not minding the fidgety toddler above her head or the crying baby nearby. By the time they landed, firefighters had found Clark, so Kushi and Gaines took the opportunity to bring the department pizzas instead—one of the organization’s priorities is to create better relationships with such agencies, so that they will recommend that families contact Maui Search and Rescue as soon as they

think someone is missing. “We want the call within one or two hours, especially with an air-scent dog,” Kushi says. “Te longer you wait, the more the scent grows cold.”

Maui Search and Rescue has participated in approximately 14 searches on Maui, O‘ahu, and Big Island, six of which have resulted in relevant finds.

To further expand their capabilities and credibility, the organization’s caninehandler teams are headed to California in April to undergo FEMA certification, which will teach and test them on search and rescue tactics and skills to utilize after disasters. Ten, they’ll learn to descend cliff faces with Maui Rappel to further expand their range of search.

Since Clark’s rescue, Kushi and Cocoa

have returned to O‘ahu several times to continue searching for 16-year-old Noah Montemayor, who vanished from his Hawai‘i Kai home, and 17-year-old Daylenn “Moke” Pua, who went missing while hiking the treacherous Stairway to Heaven trail. Neither has been found, but Maui Search and Rescue continues to stay in touch with the families.

Of her own children, Kushi says, “Tey know what [Cocoa] does, that she’s not necessarily looking for somebody that’s alive. … Tey understand that everybody does need to come home.”

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Sally French understands the necessity for artists to collaborate with other creatives, get outside their comfort zones, and push their limits, which she invites them to do at her Kaua‘i studio.

Sally French understands the necessity for artists to collaborate with other creatives, get outside their comfort zones, and push their limits, which she invites them to do at her Kaua‘i studio.

FLUX PHILES

SALLY FRENCH |

THE KEEPER

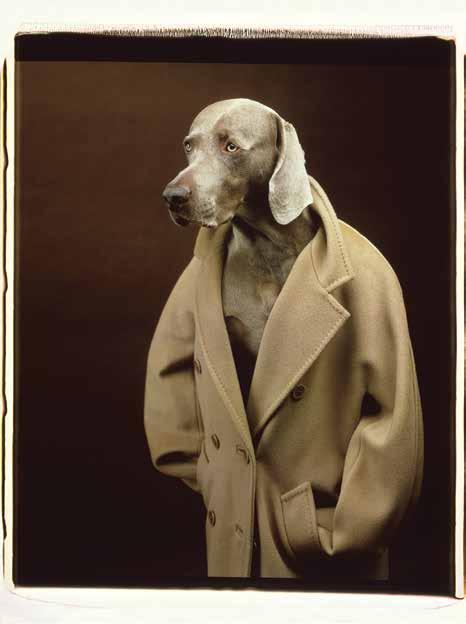

SALLY FRENCH DOUBLE DOG

DARES ARTISTS TO EXPLORE THEIR CREATIVITY.

TEXT BY COCO ZINGARO

IMAGES BY BRYCE JOHNSON

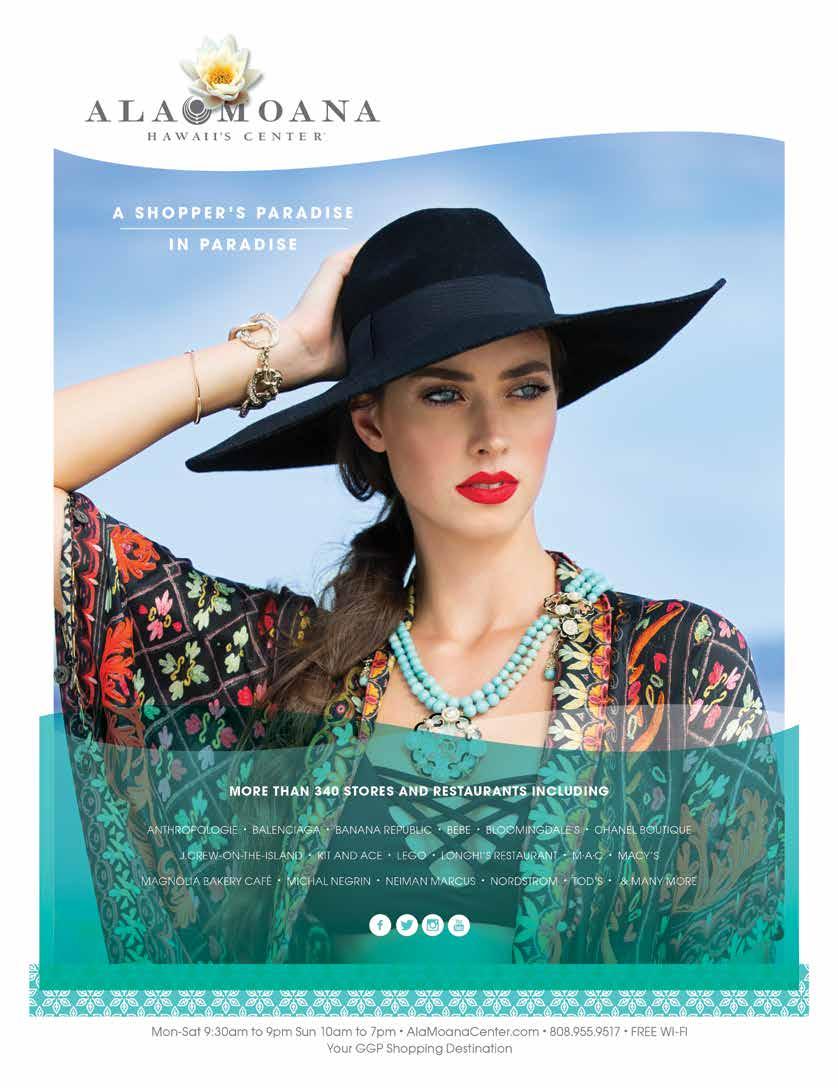

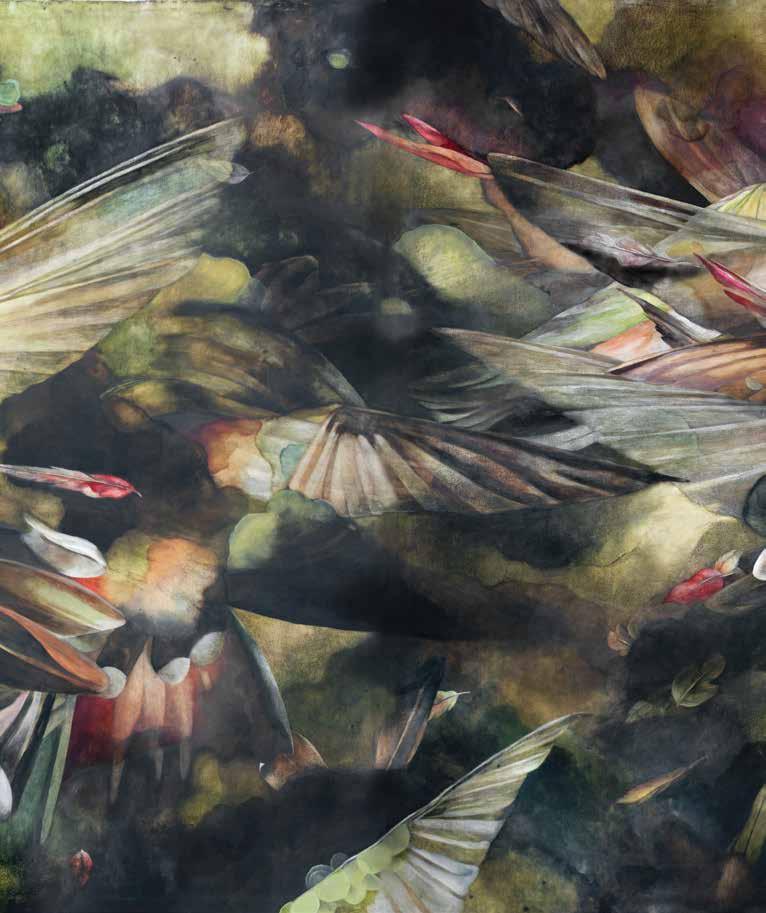

In a mountainside studio overlooking Kaua‘i’s alluring south shore, a handsome French bulldog named Sunny strikes a pose. Tis canine is the muse of artist Sally French, whose monotypes portray him in a variety of ways: In one, he exhibits the perfect dog shaming pose, petrified perhaps as a result of some recent bad behavior, while another shows him stoic, the perfect canine specimen. Te portraits are simplistic in form, a seeming departure from the works French has become known for—sexy kitties posed as strippers, a selfportrait of sorts on “candy ass pink,” a tattooed kitty punching the living daylights out of a nameless masculine form that personifies roadblocks for the artist. Her work deals in visual narratives, as she calls them, depicting her personal life and the environment around her. And what about Sunny? “Look at him,” she says of her sweet-demeanored dog. “I can’t help but use that face.”

French’s space, which she named Double Dog Studio, is filled with almost every artistic tool imaginable. A wooden cabinet filled with drawers holds supplies like fishing line, wood floor pieces, alligator clips, charcoal, glass weights, S-hooks, and of course, dog clippers. It all elicits an urge to grab a brush and start painting. French believes that she has the perfect recipe for artistic ingenuity, which is why she offers artist-in-residence retreats at her Kalaheo studio. “Tere is a surge of energy that comes with a new experience, a change of environment, and a defined amount of time to react creatively to it,” French says. “Artists tend to push through their walls of resistance and see solutions not available in their own working spaces.”

Te California native knows how necessary it is for artists to collaborate with other creatives, get outside their comfort zones, and push their limits—in fact, she “double dog dares” them to do so. At her studio, French provides workshops and weekend intensives for visiting artists, which can include accommodations in her beautiful home located just above the studio. Te intensives are composed of four days of studio work and consist of groups of up to five. Te artists work only in printmaking, with a focus on monotypes, which involves applying paint to a plexiglass plate and running it through a press to create a reverse image.

Prior to opening her studio to other artists two years ago, French used it privately for more than three decades after moving to Hawai‘i from San Francisco, where she taught figure drawing while majoring in illustration at the San Francisco Academy of Art. While there, she was part of an art collective that saved a turn-of-the-century hotel called the Goodman Building from demolition, using their rent money to paint the façade and to create a public art space. (Today, the building is still designated as an artist live-work space.) French also painted murals, including one at rock group Jefferson Airplane’s mansion on Fulton Street. “Tey paid my rent at the time, and I had all my art supplies on their tab,” she recalls of the collaboration. “Tat’s all I was paid, but it was fine with me since I could listen to them practice.”

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

|

French has exhibited her art in nearly 40 solo shows at various locations, including Heidi Cho Gallery in New York City, the Contemporary Center for the Arts in New Orleans, and Te Contemporary Museum on O‘ahu, now known as Honolulu Museum of Art Spalding House. Fumiko, Keeper of the Meek, a digital print from Wunderlust: Te Keepers’ Tale—a series of photographs that French eventually turned into a book—is currently on display at the Hawai‘i State Art Museum. Based on French’s daughter, Aimee, Fumiko,

one of eight keepers living in the land of Wunderlust, “watches over the young, guards the weak, sets the calendar, yodels, and yells all news throughout the land.” It’s a visual narrative not unlike the one unfolding at Double Dog Dare Studios. “When students are ready for what I can offer them, it’s really quite magical what happens,” French says. “I have found that artists always rise to the opportunity and create some of their best work in this studio, and this, in turn, stimulates me to create my best work.”

To see Sally French’s work on Kaua‘i, visit galerie 103, located at Te Shops at Kukui‘ula. To learn more about becoming a visiting artist at the Double Dog Dare Studio, visit doubledogdarestudio.com.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Sunny, French’s French bulldog, is often the muse for the artist’s work. “Look at him, I can’t help but use that face,” she says.

“It all started in

when a

2012,

friend suggested I paint a cat wearing an aloha shirt drinking a Mai Tai. It was fun, so I painted another cat drinking a cosmopolitan. I’ve been painting animals ever since,” says artist and gallery manager Lisa Shiroma.

WIDE EYED

LISA

SHIROMA IS AS ALTRUISTIC AS THE ANIMALS SHE PAINTS.

TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ

IMAGE

BY

JOHN HOOK

It’s pouring in Honolulu, the kind of rain that can be heard from inside a bustling art gallery during a show. I’m hurrying through the downpour, avoiding giant puddles, when moments later, artist and curator Lisa Shiroma appears in a kneelength gray dress and tall black boots. Her hair is jet-black and is pulled back into a ponytail. Unlike the weather and the color palette of her attire, Shiroma’s demeanor is warm and bright. She opens the door of the Koa Gallery at the Kapi‘olani Community College campus and ushers me in.

Te cozy gallery is on the first floor of the Koa Building, where KCC’s art department is located. Since it was built in 1980, many respectable artists have shown here—Keichi Kimura, Isami Doi, and Lucille Cooper, to name a few—who have paved the way for other local artists to gain recognition within the community. Shiroma, the gallery manager, gives me a tour of the space, where Mixed Media Miniature, an annual exhibition presenting the works of more than 150 artists of different mediums, is on display. Hanging in it are two paintings by Shiroma, one of Grumpy Cat, the Internet-famous feline whose pouty face garnered him millions of views, and another of Boo, the adorable Pomeranian dog with 19.3 million Facebook likes. “I think people are naturally drawn to animals because they have a special ability to make people feel comforted and unconditionally loved,” Shiroma says of her work. “In my paintings, I try to capture the twinkle in an animal’s eyes to make it look more lifelike. I think the eyes are the most important part of the painting, and I spend a lot of time trying to make them look right.”

Shiroma, who is in her mid-30s, calls herself something of a late bloomer. Although she won awards for her art as early as kindergarten, she didn’t realize her full potential until after she had already graduated with a bachelor of arts in psychology from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. “At the time, I was working with an autistic girl, always encouraging her to do art—sort of like the unfulfilled wishes of a parent,” she recalls. “But then I realized it was me who really wanted to do art.” She enrolled at Kapi‘olani Community College and began working as a lab assistant for the sculpture instructors. Shiroma had a knack for sculpture (Titty Bar, a bronze chocolate bar with boobs, was displayed in the Japanese Chamber of Commerce’s Commitment to Excellence exhibition), but it was painting that especially resonated with her. “It all started in 2012 in my last semester of school, when a friend suggested I paint a cat wearing an aloha shirt drinking a Mai Tai,” she says. “It was fun, so I painted another cat drinking a cosmopolitan. I’ve been painting animals ever since.”

In addition to being the gallery manager, Shiroma is also an art teacher at Kuhio Elementary, a part-time instructor at the Honolulu Museum of Art, and does small-scale metal casting in silver and bronze for local jewelry designer Andromeda Hendricks. Since curating her first show in 2012, when Koa Gallery director David Behlke asked her to pool a few students to present at KCC’s 220 Grille, Shiroma has organized shows in such places as Kissaten Coffee Bar, W Bistro (now closed), and UH’s sculpture courtyard. “Introducing the artists to each other at the opening receptions was like the icing on the cake,” she says. “Te artists, who would isolate themselves and work all the time, had a chance to show the fruits of their labor and get validation from their peers.”

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

PHILES | LISA SHIROMA |

FLUX

HOME ON THE RANGE

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

THREE MAUI PANIOLO AND THE HORSES THEY RIDE

TEXT BY ANNA HARMON | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 37

The paniolo of the Valley Isle can roam exactly 727.2 square miles. Tat is if you include Maui’s off-limits neighborhood developments and glittering resorts, the busy highways, and the island’s last sugar plantation still cranking out molasses and smoke. Teirs is a culture that doesn’t fall in step with the busy streets of Lāhainā or the pet-pampering populations of Kīhei. It was nurtured on the slopes of Haleakalā, where wild cattle took to grazing at the turn of the 19th century, and vaquero-trained paniolo became adept at wrangling the bovines three decades later. Around the time the paniolo were learning this trade, the volcanic crater’s land was stripped of its remaining sandalwood trees, and Western businessmen and plantation owners leaped at the chance to set up cattle ranches, both remote and expansive, on the naked land. Local homesteaders soon joined in, claiming small plots for their own agricultural endeavors.

Concentrated in Upcountry Maui, there is a contemporary paniolo community with traits that can be traced back to this Hawai‘i history, and other characteristics that mirror those found in cowboy culture on the other side of the Pacific Ocean. In Kula, annual rodeos seem more like family gatherings than prize competitions. At these events, country music blares from speakers, and concession stands sell plate lunches and shave ice. Competitors wear belt buckles that shine in the sun and trade trucker hats for Stetsons when the time comes to race around barrels or team-rope a steer.

On the handful of ranches on Maui, such as Ulupalakua Ranch and Haleakala Ranch, a small number of lucky paniolo get to live and breathe the working country lifestyle. Teir horses are not only rodeo partners and pets, they are working companions. When it’s time to move cattle, or to round them up for weaning or branding, the abilities of these horses can mean failure or success, injury or safety.

Meeting up with a paniolo ain’t easy. Locations change, horses escape, phones are lost. Look for the green gate on the left a mile and a half down the road. Look for the man out back clearing weeds and piling them onto the back of an ATV, his new puppy tumbling alongside him. Look for the cowboy hat, for the quiet place, for the dusty arena. And of course, look for the

horses they ride to wrangle cattle, lead tours, and race time.

Caysie Madeiros is seated on the tailgate of a pickup truck parked in the family pasture, where buffalo grass grows tall. Te family’s spotted white cattle dog Milo sits next to her, and her iPhone rests in her lap. Te 15-year-old doesn’t wear a cowboy hat—her long, brown hair hangs loose down her back, and her bootcut jeans are tucked into worn, elaborately tooled cowboy boots. Nearby, her dad and a couple of family friends are shoeing her horse, which is named Bucky because he is a buckskin. But she calls him Bullet, because he is so fast.

In July 2014, at the age of 13, Caysie became the youngest to win the All-Around Cowgirl title at the 4th of July Makawao Rodeo—Maui’s largest—competing against experienced women wranglers four times her age. She did so by earning the most points in the women’s events, which included steer undecorating (chasing a steer across the arena to pull a flag off its hindquarters); pole bending (weaving through a line of six poles as quickly as possible); barrel racing (sprinting your horse in a particular pattern around three barrels that are set up in an equilateral triangle); and breakaway roping (chasing a steer until you rope it around its neck). It was no coincidence that Bullet was the horse she rode. “Tat was all because of him too,” Caysie says. “At rodeos, he’s super competitive. I can’t even get him to walk because he just wants to go.”

Bullet is a competitive but solitary gelding who took months for Caysie to sync up with after she got him in August 2013. He doesn’t care to nuzzle visitors, and is eager to wander off to a lonely corner of the pasture. But the other two horses owned by the Madeiros family make up for Bullet’s reclusiveness. “[Johnny is] the personality horse, come over here and bother everybody,” says her dad, Chucky Madeiros, about their black gelding, who Caysie rides for team roping events since Bullet can’t help but run too fast. “He’s going to latch on to you in a few hours. ... Sweet Pea is the same thing.” Tis sorrel mare is the default horse for Caysie’s 9-year-old brother, CJ, who has recently graduated from mutton busting

(an event in which children attempt to ride and race sheep) to roping. All three horses came from Ralph Fukushima, the owner of Ralph’s Tack and Transportation on O‘ahu, who helps support the Madeiros children by providing steeds and tackle. He goes way back with Chucky, a longtime rodeo cowboy whose land came from grandparents who homesteaded in Kula—their residence sits on land from his grandfather Joseph Madeiros, and the pasture where they keep the horses is from his grandmother, Rose Rodriguez. It is Chucky who opened the door to roping and rodeo for Caysie. She team ropes with him, and calls him her best friend.

“[Caysie] was on the horse before she could even walk, just sitting on the saddle with one of us,” says her mother, Janice Palad, who picked up barrel racing when she was married Chucky. At events, the couple’s daughter would be passed from saddle to saddle. Palad remembers Caysie’s first competition riding solo when she was around 2 years old, in an event with parents leading their children around barrels. “Pretty soon, she would not want anybody to lead her,” Palad says. “She’s just like, I don’t care if I don’t have a fast time, I just want to go by myself.”

Nowadays, while attending King Kekaulike High School, Caysie hangs with a likeminded crew. “Sometimes one of my friends brings the roping dummy and we rope at school,” she says. Twice a week, she practices with them and other community members at Piiholo Ranch Arena. Afterwards, she likes to ride with a friend through the forest to take the cattle back to the family’s pasture. But her dad makes sure that rodeo doesn’t distract from school. “We just got her report card, and she’s got a 4.0 GPA,” he says. “We’re really proud of her.” Upon graduating, Caysie hopes to study marine biology on the mainland while competing in junior college rodeo. She hopes Bullet can come along, too.

In 2015, as a freshman, Caysie was one of 21 Hawai‘i high school students who competed at the National High School Finals Rodeo. For the qualifying state high school rodeo competition on Big Island, she had to send Bullet ahead on a freight ship one week in advance, with an overnight stop on O‘ahu—an expense covered by a family friend at Young Brothers. At

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Caysie Madeiros rides her bucksin horse, Bucky, who she calls Bullet, at her family’s pasture in Kula. In their first 4th of July Makawao Rodeo together, in 2014, Caysie became the youngest in the contest’s history to win the All-Around Cowgirl title.

Caysie Madeiros rides her bucksin horse, Bucky, who she calls Bullet, at her family’s pasture in Kula. In their first 4th of July Makawao Rodeo together, in 2014, Caysie became the youngest in the contest’s history to win the All-Around Cowgirl title.

Garrett Montalvo uses all of his trained horses, including this 7-year-old buckskin that he has yet to name, for everything ranging from horseback tours to wild cattle roundups. “A horse, you gotta give a little more respect because he has to carry you all over the place,” he says.

Emerson Makekau breeds and trains his own horses, looking for composition, stamina, speed, and heart. When it comes to training a colt, “From day one, just keep treating them like your kids,” he says.

nationals in Gillette, Wyoming, where she competed in breakaway roping, she used the horse of a cowboy family from Utah, since transporting Bullet would have been too expensive, and too stressful on him. For paniolo, the cost of roaming and rodeoing outside of home islands brings a high toll.

Back on Maui, Caysie and Bullet have begun competing in double mugging at high school rodeos, which, her dad explains, is usually a men’s event, and involves a team of two riders roping a steer, wrestling it to the ground, and tying three of its legs together. “It just looked fun,” Caysie explains. “Plus, like how my dad said, it’s like a guys’ event, and I’m a girl. I wanted to prove that I could do it, too.”

Garrett Montalvo goes by the name Potagee Paniolo, which he uses in his voicemail and as a signature on every text message he sends. He got this nickname when he was a teenager. “All my friends Upcountry call me Pocho, Potagee,” says Montalvo, who is Portuguese and Filipino. At Baldwin, he was the lone student in a cowboy hat and boots,

hence the nickname paniolo. “I just put the two together and that’s what everybody started calling me,” he says.

If you can’t reach the 31-year-old on the phone, you will hear, “I am either on the job, driving, or being with the animals.” To make a living, Montalvo builds and fixes fences, raises animals, leads trail rides for Triple L Ranch, and pitches in on cattle roundups. If he could choose, he would be a full-time ranch hand.

“I’m the last of my family to be a cowboy,” he explains at a coffee shop in Honolulu, where he is visiting from his home in Makawao in order to obtain legal services for divorce—woman troubles, a trope of many a country song. Amid students studying for finals and baristas steaming milk, Montalvo isn’t quite at home, insisting he doesn’t need a drink. He wears a black cowboy hat and new Wranglers. His belt buckle is from his 2004 bareback bronc-riding win at the 4th of July Makawao Rodeo. “My great grandpa was a paniolo at Haleakala Ranch,” says Montalvo, who picked up the skills from his dad, a man he says he didn’t get along with outside of wrangling cattle. For most

of his childhood, Montalvo lived with his grandparents, who weren’t involved in rodeo or ranching (his grandfather was a Maui chief of police), but for Montalvo, “It was just what I was born to do.”

Today, the paniolo has five horses, the youngest of which he has set aside for his 6-year-old nephew. He likes to get them green-broke, which means that the horses come with basic knowledge of how to be ridden, so he only has to “give them a job and show them how to do it,” such as rounding up cattle or tourists. Tere is Blackie, who Montalvo has had since he was 5. (Te average life span of a horse is 25 to 33 years.) “Blackie is my most faithful horse,” he says. Unlike a difficult horse that may be hard to catch or that may refuse to enter a trailer, Blackie comes right up to Montalvo when the paniolo arrives at his pasture, taking a halter and walking into the trailer without a fuss. Ten there is Pepe, who he got in high school. “She’s got her good days and her bad days. Some days she feels like she’s ready to work, other days she’ll pull a quick one on you and act like she’s hurt.” Next is Paliku, a sorrel gelding that he got from his uncle who just

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 41

Some horses take care of you; others, with their speed and competitive nature, can be trusted to get you to the winner’s circle.

passed away. Te final two are a 7-year-old buckskin and a 5-year-old chestnut colt he has yet to name.

Of them, Montalvo insists he doesn’t have favorites. He rode Pepe all the way from Kula to Baldwin High School when he was a student, has ridden Blackie on wild cattle roundups, has taken the buckskin to lead tours from Bully’s Burgers on the slopes of Kanaio in Kula to Kanaio Beach in Wailea and back. On long excursions, he needs all his trained horses to rotate through, to ensure that one doesn’t get overworked.

Montalvo recalls his scariest horseback experience, which took place with his dad in Mā‘alaea, where towering windmills now stand. “A bunch of wild cattle chased us through the fog, you couldn’t see five feet in front of you,” he says. “Tey were charging for us. We ran, made a big circle, a loop around them, and the dogs chased them.” In the end, the father and son escaped unscathed. Typically, the tactic is to rope these wild animals, tie them to a tree, and then leave them there for a couple days to wear themselves out, making it easier and safer for the paniolo when he returns to bring them down the mountain for slaughter. Nowadays, to combat the erosion caused by the cattle, the animals are mostly being shot from helicopters, considered a safer, more financially effective approach. Montalvo thinks differently. “I’m trying to get it so we can go in and extract them before they go shoot them again,” he says. Tis paniolo’s preferred way of life is often at odds with contemporary Maui. Helicopters are used to kill the wild cattle that Montalvo would rather wrangle up. He has been reported to the Maui Humane Society for a handful of things, like not

feeding his horses while keeping them in pastures with over-knee-high grass (though sustenance of this type is plenty sufficient), or not providing the horses with enough shade, which he rectified by moving his fence to allow for more coverage. Trails he once rode are now closed to him, since horseback riding can be considered another form of erosion. Developments continue to expand, while ranches contract. But he is still excited that his young nephew has taken an interest in what he does, even though sometimes all he feels that he gets out of Maui’s Upcountry community is a lot of headache. Living on an island, “You become sort of a topic after a while,” he says. But it’s a community Montalvo knows he needs. Te rodeo events he competes in, besides bull riding, involve techniques that lend themselves to ranch work, such as rounding up calves for branding. From roping to hogtying cattle, the skills demonstrated in competitions are also those necessary in managing the grass-fed or -finished cattle on Maui’s ranches— which Montalvo is eager to help with when he gets the chance. One cowboy can’t do it alone. “Upcountry,” he says, “we all kukui each other on the ranch, so we all go on a cattle drive.”

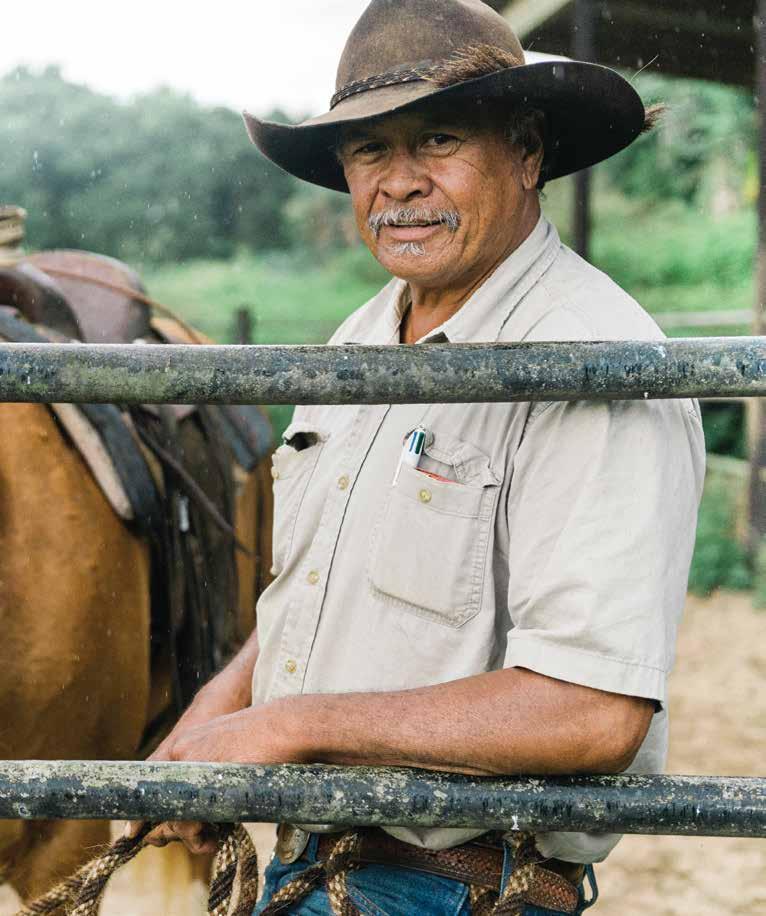

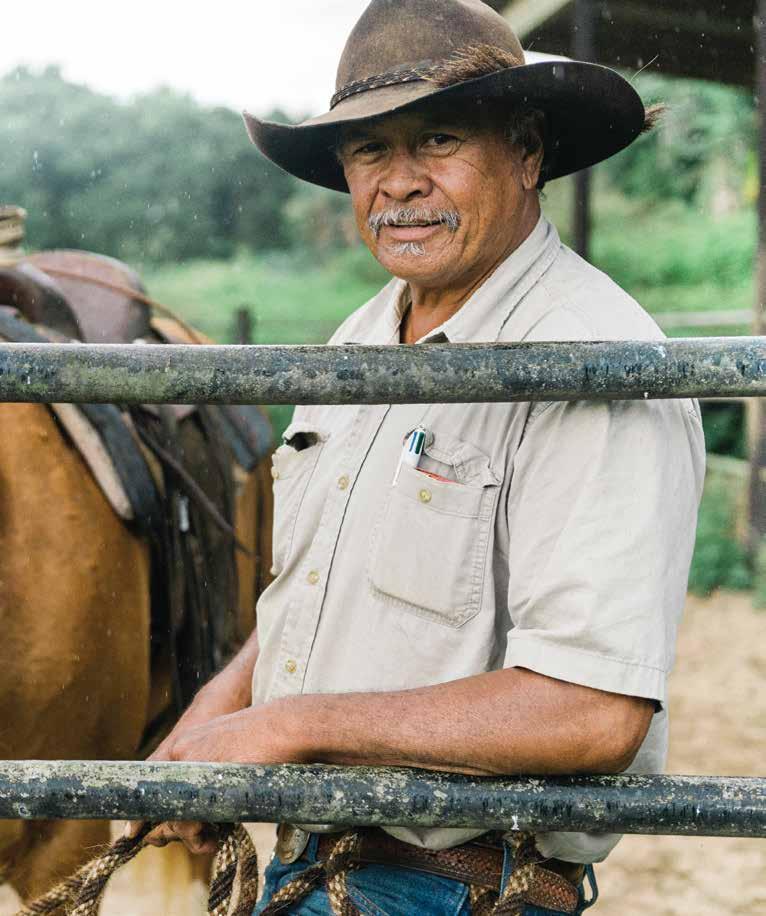

As Makekau explains this, he sits at a picnic table behind Ulupalakua Ranch Store as his 2-month-old Kelpie puppy, Jake, chews on his finger. Te 51-year-old’s home is just within view. He wears a brown cowboy hat with a braided horsehair band, and a belt buckle memento from when he was honored at Molokai Ranch’s centennial celebration. In his spare time, he likes to pitch in around the remote community. Every day, Makekau moves the ranch’s grass-finished cattle to graze in a new area. Other days, he and the five other ranch hands will bring the herd down for branding or weaning, work on irrigation (for this task he uses an ATV, not a horse), whatever needs to be done. His work horses, Princess, Lily, Beau, Badger, and Mahina, which he may rotate throughout the day depending on how demanding the task is, are kept at the ranch.

Emerson Makekau likes to get up early— very early, at 3:30 a.m. At this dark hour, even before birds have begun chirping, the soft-spoken paniolo turns on the news, drinks his coffee, and fills out any work reports he may have as a ranch hand at Ulupalakua Ranch. “My favorite moment is going to work, being around the livestock,” he says.

Most of them are quarter horses, though a couple are part-thoroughbred. “Toroughbreds, you’ve got the speed, the quarter horse, you’ve got the brains,” he explains. Makekau breeds and trains his own horses, and has earned a reputation for his skills and patience with the animals. “People like to call it ‘break them in,’ but we put them through training,” he says. “It’s day by day, you know? You cannot start from kindergarten and expect to graduate the day after. Some horses is fast learners, and some takes a little while.” In the ones he chooses to keep, he looks for good composition, attitude, speed, and heart.

Makekau got a taste of this lifestyle at an early age, on Moloka‘i, where he was born and raised. His uncle, a paniolo at Molokai Ranch, took him under his wing. “I loved horses, animals,” he says. “It kept me out of trouble.” He began working

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Makekau is one of six ranch hands at Ulupalakua Ranch, where he keeps his work horses Princess, Lily, Beau, Badger, and Mahina.

Makekau is one of six ranch hands at Ulupalakua Ranch, where he keeps his work horses Princess, Lily, Beau, Badger, and Mahina.

summers, helping with the branding at Molokai Ranch, and competing in rodeos. “Growing up, when I was a young boy with my uncle … it was like the rough tough cowboy deal,” he recalls. “I guess I enjoyed it, and loved the horses so much that I wouldn’t go to bed. Te next morning, you know, I’m always wide awake.” He would ride horses until 11 o‘clock at night, offroading through ranch pastures and up in the mountains.

Makekau followed in his uncle’s footsteps, working at Molokai Ranch for 15 years. Watch old promotional ranch videos, and even a documentary about Hawaiian paniolo, and you will spot Makekau riding a handsome bay stallion. Tis is the quarter horse that he has favored the most in his career. “He had the power in him, but he was really, really tame and mellow,” Makekau says. “A lot of stallions, you go into an arena and they’ll make big noise and problems.” Makekau was 28 when he got him as a 6-month-old colt, and while it was one of his main work horses, he would also walk his young son around on him. “My wife and I raised him until he died. He was 26,” Makekau remembers.

Eleven years ago, Makekau moved to Maui, bringing with him his wife and

five children, because he “got into family life,” as he puts it. He worked as assistant manager and ranch hand at Kaupo Ranch for several years before joining Ulupalakua Ranch. “Tis ranch, it’s unbelievable,” he says. “Everybody bonds together here. We call it the Hawaiian style—if one’s down, you pick them up, you know. We cheer them on and move forward. If they have a problem we’ll talk story, try to solve it, and move forward.”

Some of the most exciting moments Makekau remembers involve wrangling wild cattle. “A lot of them is being shot. … Te theory is, ‘Why you guys wanna go rope a wild bull with a horse that cost you $2,000, $2,500, $5,000, and the bull is only worth ten cents?” But that misses the point, he says. “Te risk, the liability, the dangerous part—the high in the paniolo cowboy is to show off your skill, what you have and what your horse have.”

Te first horse ever to step hoof in Hawai‘i arrived on Maui on June 23, 1803 in much the same way that wild cattle were introduced to the islands in 1793: It came from California aboard a Western explorer’s

ship and was intended as a gift to win King Kamehameha’s favor. (He apparently showed little interest.) Te horses that were introduced served no immediate purpose on the islands, since ranching and cowboys were yet to be. Instead, these wild mustangs roamed free.

As Haleakalā’s slopes became home to wild herds and expansive ranches, more horses were imported, this time to serve as the trusty steeds of paniolo wrangling in feral cattle for the beef trade and managing domesticated herds on ranches. Te techniques remain surprisingly similar today, as do the tools: the lasso, the saddle, the boots and hat—and the trusty steed.

Like Caysie says, some horses take care of you; others, with their speed and competitive nature, can be trusted to get you to the winner’s circle. For Montalvo, a horse deserves your respect because he carries you far and wide. And for Makekau, a stallion with spirit and speed, with the right attitude, will hold a place in your heart for as long as you live. Your grandchildren will ride them, will fall in love with roaming the remaining open spaces on the islands. A good horse, he says, “It becomes a part of you.”

Caysie and her 9-year-old brother, CJ, are happy to follow in the footsteps of their father, Chucky, a longtime rodeo paniolo. Pictured with them are their three horses, Bucky aka Bullet, Sweet Pea, and Johnny.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 45

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

IN DOG

WE TRUST

ONE ORGANIZATION HELPS INDIVIDUALS GET BACK ON THEIR FEET BY GIVING THEM FOUR MORE.

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK, SAMANTHA HOOK & JONAS MAON

When Charlene Hasebe rises from her wheelchair, Puff, a 10-year-old Labradoodle, stares inquisitively at her owner, cocking her head slightly as if to ask, “Everything alright?” As Hasebe wobbles across the room, the canine’s eyes never stray from her owner, watching her as a mother would watch her child. For centuries, domesticated dogs have used eye contact to bond with their owners, and it’s a skill that puppies hone early in their training to become service dogs at Hawaii Fi-Do.

Founded in 1999 by Susan Luehrs, Hawaii Fi-Do is a nonprofit organization that matches service dogs with those facing the daily challenges of living with a psychiatric or physical disability, like Hasebe, who was born with cerebellar ataxia, a disorder that affects the brain’s ability to control muscle coordination and gait. “When she sees me wiggling back and forth, swaying, she wants to help me, but I shoo her away,” Hasebe says of Puff, who helps her owner to retrieve items and open drawers. “She’s a small dog, and I could break her hip.” Hasebe has been living on her own in a quaint Whitmore Village apartment in Wahiawā since 1995. “Without her help, I would be living in an institution,” Hasebe says. “With her, I feel more confident. … I feel like I can meet the public. I may be in a chair, but I can still go out.”

Tat Hasebe has been able to stay on her own for so long is thanks, in part, to her constant canine companion, who also helps Hasebe stay active. Caring for Puff—trimming her hair, cutting her nails, brushing her teeth—helps strengthen the muscles in Hasebe’s hands, a particular problem area for the 64-year-old, but it’s the Labradoodle’s natural ability to uplift others that has bolstered Hasebe’s spirit the most. “When people see her, they are so happy,” exclaims Hasebe, who serves as a trained volunteer for Hawaii Fi-Do, offering therapeutic wellness visits at hospitals and care homes around O‘ahu. On Tuesdays, she and Puff visit seniors at assisted living facility Te Plaza at Mililani; Fridays, they make the rounds at the hospice center in Wahiawa General Hospital; and every second Wednesday, the pair heads out to Kahuku Hospital. “We had this lady, and she was a grouchy lady,” Hasebe recalls. “She couldn’t connect with Puff. But we kept going and going, then finally one day, she just accepted

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

“With her, I feel more confident. I feel like I can meet the public. I may be in a chair, but I can still go out,”

Charlene Hasebe says of her 10-year-old Labradoodle, Puff.

Puff. … She would make Puff go on her bed, and she taught Puff how to honi honi her—that means kiss.”

Despite her disability, Hasebe considers herself lucky. “Am I going to ask, ‘How come God made me this way?’” she says. “If I’m sad and depressed, what am I going to do about it? So I say, ‘Come on Puff, let’s go out.’”

Te bond between dog and human companions is a strong one—science has proven this fact with complex studies that demonstrate the presence of elevated levels of oxytocin, a hormone that promotes social bonding, in both canines and keepers when they interact. But one only has to observe a rollicking canine greeting its master after periods of absence both long and short to understand the deep impact a dog can make on a person’s life. Susan Luehrs observed this firsthand in 1999, while working as a special education teacher at Kahuku High School, where she began bringing therapy dogs into the classroom to engage the students. Luehrs had started a vocational program called

the Youth Trainers Project, in which at-risk youth learned pre-employment skills while helping to train, groom, and socialize young dogs that were in training. It was eye opening for her. “When the kids in the wheelchairs went out in the schoolyard with the dog, people came and talked to them,” she says. “It wasn’t just the adults, it was the football guys, the cheerleaders, the custodians.” Dogs, Luehrs came to realize, fostered relationships. Tey were hooks, motivators, and wellsprings of unconditional love.

Before Hawaii Fi-Do, service dogs were procured from the mainland—a lengthy process that involved complex quarantine procedures. Guided by the late Eloise Monsarrat, who developed the Human Animal Bond Program in collaboration with the American Red Cross at Tripler Army Medical Center, Luehrs set out in 1999 to build what was, at the time, the only service dog training organization in the state. Two years later, Hawaii Fi-Do became a member of Assistance Dogs International—which sets the standards of the assistance dog industry in North America, Asia, Europe, and Australia— and in 2005, Hawaii Fi-Do became the

first organization in Hawai‘i to become accredited (the other accredited program is on Maui)

Today, at its kennel facility located on the North Shore, Hawaii Fi-Do breeds the Labrador retriever and Australian Labradoodle puppies that will one day become accredited assistance animals. Training for the service dogs, which are different from therapy or emotionalsupport dogs, begins when the canines are just three days old. Once they are about 3 months, the pooches move in with puppy raisers, which Luehrs calls the “heart and soul of the organization,” who ready the pups for lives of service. During the next two years, these accredited volunteers will train the dogs to recognize upwards of 90 commands.

Beneficiaries of Hawaii Fi-Do have included individuals with a wide array of needs, from those with hearing disabilities to veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder to young adults facing cancer. Luehrs estimates that about 80 dogs have been placed since the organization’s inception 16 years ago. Te process is slowgoing and the need is great—the wait time to receive a dog is currently two years. It’s

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 49

Young Labradoodles train with volunteer puppy raisers for two years before becoming service dogs.

A smart, kind, intuitive animal such as this— which is not any animal, but an extension of your soul—becomes a holy presence, becomes a sacred presence that looks at you, witnesses you.

also costly: Te process of breeding, raising, and training a dog to become certified can total anywhere from $16,000 to $20,000. Despite this expense, the privately funded organization provides its dogs free of charge.

“Tis is life-changing work,” says Nayer Taheri, who was given a service dog in 2014. “Here is this gift that comes into my life and improves my life-quality emotionally, spiritually, physically. It brings tears to my eyes.”

It was raining the day Nayer Taheri first met her service companion, Wren, then a small, 3-month-old white Labradoodle, on the grounds of Hawaii Fi-Do’s outdoor North Shore kennel. As Taheri kneeled in the dirt on all fours, a Persian proverb she had once heard came to mind: “Tere are thousands of ways to kneel down and kiss the ground.” As she bent to pick up the young puppy, she began to see the world from the dog’s point of view: “Playfulness, gratefulness, sense of trust … When I look from her eyes, [I see] the green of the grass and hear the chirp of the birds differently—and you are grateful for it,” she reflects.

For years, Taheri had battled debilitating anxiety attacks, bouts of vertigo, and spells of depression that left her housebound. Taheri had fled to the United States in 1994 with her son, Daniel, who was 3 at the time, to escape the Islamic Republic of Iran’s oppressive regime. Taheri’s life in Iran had been mired in brutality. After the Iranian Revolution of 1979, Taheri recalls, everything changed in an instant. Supreme leader Ayatollah Khomeini ruled according to Sharī‘ah, or Islamic law based on the

Qur’an, whereby, according to Taheri, social constructions shifted, and human rights for women, children, and minorities disappeared. Ten, war. From 1980 to 1988, tens of thousands of Iranians were killed during the Iran-Iraq War (some estimates place the death toll as high as a million). “Upon that, there was political upheaval,” Taheri says. “So you live based on that, and you are aware that you are just surviving, like a fish, you learn to find a way out.”

Upon arriving in the United States, in her search to mend her soul after the trauma of her past, Taheri found healing through ministry, becoming a Unitarian Universalist chaplain in 2006. It was during Taheri’s ordination assessment that she met fellow chaplain Cynthia Kane. Te two fell in love, were married, and gave birth to two children, Asher and Ari. In 2013, when Kane received orders to move to the Marine Corps Base in Kāne‘ohe, her family followed. Despite Taheri’s strong family life and her attempts to make peace with who she was, her infirmities prevailed. A panic attack left her frozen in the cereal aisle at the commissary for over an hour, disassociated from reality and unable to move until Kane came to retrieve her; a fainting spell left Taheri with a mild concussion and a sprained shoulder.

A few months after arriving to Hawai‘i, Taheri initially dropped in on Hawaii Fi-Do on the suggestion of Kane, who had heard about the service dog program at work and thought her spouse might benefit from being around the dogs. “Little did we know,” Kane says, “that she was then going to become a candidate.” Taheri agreed to pay a visit to the center, mostly because she liked the idea of the long drive to the North

Shore. Tere, she listened to a veteran share about living through an explosion in the war. His story resembled her own in many ways, and she began to feel that familiar sense of panic welling up inside her. “After living a long time with the symptoms, you become stoic and try to pretend everything’s okay, even though deep inside everything is shattering,” she says. Te veteran’s dog, which was sitting across from her, sensing something amiss, stood up, walked over, and put her face in Taheri’s lap. “It just brought so much comfort at that moment,” she recalls.

Taheri began helping out around the kennel, and when she laid eyes on Wren that day in the rain, an instant connection was made. “It was clear that they got each other, just like spouses do,” Kane recalls of Taheri and Wren, who grew to be a striking Labradoodle with a broad chest and friendly face. “Tere’s a shorthand in an intimate companionship—there’s this kind of knowing that goes beyond words, and I could tell that the two of them were completely in connection with one another.”

Today, Taheri calls Wren the “chaplain to the chaplains,” providing emotional and physical support to the entire family. “She just is so very smart that she learns about what pleases you, what displeases you, what triggers you—she knows,” Taheri says. “I don’t know how she has this information, but she is so sensitive that she learns very fast.” Wren is so intuitive, in fact, that she can anticipate when an attack might hit, guiding Taheri to a quiet corner or licking her hand until the panic subsides. Just recently, Taheri was holding their newborn, Ari, when a dizzy spell hit and she began to fall backward. “[Wren]

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“She is an

extension of my soul,” says Nayer Taheri, shown right, of Wren, the Labradoodle service companion that helps her overcome anxiety, vertigo, and depression. The two are shown here with Taheri’s spouse, Cynthia Kane, and their two children, Asher and Ari.

Despite the lengthy and costly process to train a service dog, Hawaii Fi-Do provides its canine companions to those in need free of charge.

Despite the lengthy and costly process to train a service dog, Hawaii Fi-Do provides its canine companions to those in need free of charge.

is behind me without me even noticing,” Taheri says. “She has her paws on the bed, with the chest protecting me.”

Tehari continues, explaining that, “A smart, kind, intuitive animal such as this— which is not any animal, but an extension of your soul—becomes a holy presence, becomes a sacred presence that looks at you, witnesses you. And in that image, in that mirror, you allow yourself the possibilities of other thinking. … Maybe if I think this way with more compassion and forgiving … my view toward the past is going to change.”

Today, Taheri believes that Wren has helped her to start trusting again. “I make eye contact, I smile more, I’m more physically active,” says Taheri, who takes Wren to the beach for exercise. “When we are coming back up the dunes … I just need a little bit of help, so I just say, ‘pull,’ and she goes with all the might and gives me a little bit of strength to get on my knees.”

FIVE THINGS YOU SHOULD KNOW ABOUT SERVICE DOGS:

ONE

Tey are not required to wear a vest, nor is their owner required to carry the dog’s identification on his or her person, to be permitted access in public.

TWO

Tey are always working. Do not pet or talk to the animal, which distracts from the job he or she is tasked with.

THREE

Tey are not carried in a purse or stroller. “A dog has gotta have four feet on the floor, otherwise how’s it gonna help ya?” Luehrs says.

FOUR

Guide dogs for the blind and visually impaired are the highest trained type of assistance dogs, followed by hearing dogs for the deaf, and service dogs, which are trained for a specific task that mitigates the person’s disability. Terapy or emotional-support dogs do not have to be trained, and their defined function is to provide comfort.

FIVE

Service dog “training” does not include being able to shake, kiss, or speak on command. Te fundamental tasks of service dogs include providing counterbalance support, leading disoriented handlers to a designated place, conducting room searches for handlers with PTSD unable to enter his or her own home, and retrieving items.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 53

Science has proven the existence of a chemical bond between dog and human companions, but you only have to observe canine and keeper interact to understand the impact a dog can make on a person’s life.

Maui Economic Opportunity has been ahead of the curve on what makes an actual difference in ending poverty for decades.

Maui Economic Opportunity has been ahead of the curve on what makes an actual difference in ending poverty for decades.

BEHIND THE WHEEL

NONPROFITS IN HAWAI‘I REMAIN THE LAST, BEST HOPE FOR AN EQUITABLE SOCIETY, PROVIDING A COMMUNITY OF CARE TO THOSE WHO NEED IT MOST.

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN | IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & COURTESY OF THE SALVATION ARMY

Most Maui county residents recognize Maui Economic Opportunity for its buses, which are easily mistaken for hotel shuttles, with a pink plumeria poking out of the capitalized “O” of its acronym, MEO. Te island’s public transportation system is a mix of the county’s fixed routes, tourist vans, and hitchhikers sharing space in the back of pickup trucks; MEO takes care of the rest: buses for schoolchildren, elderly, and the disabled, who would otherwise be left sans transportation. MEO’s buses traverse the three islands that comprise Maui County: Maui, Lāna‘i, and Moloka‘i.

A ride with MEO entails more than getting from point A to point B. MEO has been ahead of the curve on what makes an actual difference in ending poverty for decades—a study published by Harvard University found that the link between transportation and social mobility is stronger than that of several other factors like crime, elementary school test scores, or the percentage of two-parent families in a community. Te longer the average commute in a given county, the worse the chances are of low-income families moving up the ladder. Harvard’s study found that

geographic agility is directly correlated with economic progress—access to schools, healthcare, and affordable goods all require transportation services. Tat’s where MEO comes in, providing transportation services to communities who need it most, literally driven by those who need the support of community most. By law, individuals with criminal records must wait three years after their last misdemeanor conviction before applying for a bus driving position; five years if they have a felony record. Tis is not the case with MEO drivers. For them, it’s a chance at a career—and a fresh start.

“Ah yes, transportation services,” says Joe Souki, the speaker of the Hawai‘i House of Representatives for Hawai‘i’s 8th District, which includes part of Maui. Souki was the executive director of MEO for 16 years, through the formative 1970s, and oversaw much of the program’s expansion. “We started with one van we purchased for $9,000 dollars, and by the time we left, we had 50,” he says. “We also did insulation, solar water heaters, nutrition programs, false teeth for senior citizens, Meals on Wheels, congregate meals, mental health programing, even Planned Parenthood— one of the first in the state.”

Driving onto the three-acre lot of

MEO in Kahului, it’s easy to mistake the place for a governmental agency. Past the first complex of buildings, maintenance men mow lawns, disabled clients queue for the bus, and workers with IDs on lanyards chat with elderly clients seated on benches. MEO was created as a private nonprofit community action agency and was organized under the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964, which was initiated by President Lyndon B. Johnson. As part of the broader War on Poverty, community action agencies were developed across the United States as a sort of political hand up rather than hand out. Te rear two-story building hosts the organization’s five departments: business development, early childhood services, community centers, youth services, and transportation services. Besides the lot in Kahului, MEO owns an 11-acre macadamia nut farm in Waiehu that serves as a job skills facility, as well as parking lots to accommodate a fleet of more than 80 buses, vans, and cars.

In 2003, faced with increasingly overpopulated prisons, Maui County commissioned MEO to study what the basic needs were of those individuals returning to society after incarceration. Based on its study, MEO extended a

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 55

nstead o e acerbatin a culture in hich e o enders are stigmatized well after he or she has done their time, mi es evidence based pro rammin ith island style connecting, focusing on the things necessary to bring an e o ender back into the community

program to former inmates, providing them with the things advocates have been requesting for years, like developing a county-specific workbook with recommendations on best practices; setting up a work furlough program, which takes advantage of the connections MEO has with local businesses to create employment opportunities for former inmates; and coordinating with other nonprofits to provide continuing care. Te program also supplies simple yet vital, daily necessities: “ID, clothing, a few dollars to get to the next place, a home for a month,” explains Bishop Pahia, an MEO caseworker with decades of experience working at Maui Community Correctional Center. “Basic stuff keeps people off the streets.” A major yet easily soluble problem for ex-offenders who are leaving incarceration has been identification, as an ID is necessary to procure basic services, jobs, and housing, and helps to keep the heat off when a parolee is stopped by police. A law to provide departing inmates with basic documents has yet to be passed. Instead of waiting around, MEO got the county to accept enrollment with MEO as a means of meeting the requirements necessary in order for parolees to procure identification. As a result of these cost-effective solutions, Maui’s recidivism rates for ex-offenders is the lowest of all the islands.

Te benefits of work programs are felt throughout the community. Instead of exacerbating a culture in which ex-offenders are stigmatized well after he or she has done

his or her time, MEO mixes evidence-based programming with island-style connecting, focusing on the things necessary to bring an ex-offender back into the community. MEO starts its programming with inmates prior to release, assisting them with educational programs and financial aid forms. Once offenders are out of jail, MEO drivers take them to job interviews, pick them up afterward, and ensure they return home without incident. Many beneficiaries of the program have gone on to build successful lives in the community. Tere are stories of clients who run photovoltaic installation businesses and asphalt companies, and others who have worked for decades as MEO groundskeepers and bus drivers. “Te success stories are the ones you don’t remember,” Pahia explains. “Tey blend back into the community. Mostly because they change the circles, swap out the people they spend time with.”

In Hawai‘i, as in the rest of the United States, the economy itself is dependent on the nonprofit sector, particularly the large, decades-old organizations that have provided their services for generations. In 2014, nonprofits contributed 5.3 percent of the nation’s entire GDP, or roughly $890 billion. In the islands, where the global 1 percent has invested in vacant properties for the last several decades, nonprofits have continued to provide essential services, largely through grants provided by the federal government. Tere are specific programs for children and new mothers, school children, the elderly, Native

Hawaiians, specific immigrant populations, the homeless, those returning from incarceration—all pulling from discreet, separate funds determined by lengthy grant requests, competing interests, and interval funding timelines.

In this environment, nonprofits continue to develop and enhance programs with federal and private funds. Founded in the islands in 1894, Te Salvation Army is another such example. Te headquarters of its Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Division is off Mānoa Road. Its 10-acre plot serves the Hawaiian Islands, Guam, Micronesia, and the Marshall Islands. Mānoa Valley residents know the turnoff as the site of the Waioli Tea Room, which closed in December 2014 after decades of service and was originally conceived as a skillsdevelopment site by the organization. In Hawai‘i, Te Salvation Army invests nearly $37 million annually in programs and services. “We have over 55 years of working with those who have addictions in Hawai‘i,” says Major John Chamness, divisional leader for Te Salvation Army Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Division. In a uniform with a white “S” on a crimson hexagon on the upper collar of his coat, he explains the global organizational model: “Our regional programs must all be self-sustaining. We do this through determining the specific needs of places through relationships with local government and other service providers.”

Te Salvation Army is dedicated to helping end systemic poverty. Te international organization’s Pathway of

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“I put myself into a dark, isolated world,” says Kea Reeves, a graduate of The Salvation Army’s Family Treatment Services, which provides substance abuse treatment for women with children. Reeves, Chamness says, is a great example of what the Pathway of Hope is about. “They just need someone to come alongside them, to believe in them, to provide tools, the friendships that they need to really find success in their lives.”

“The Salvation Army does drug treatment for individuals in the facility, and has found that treatment programs are more successful than incarceration on its own. People need a friend to walk alongside them through treatment programs.”

— a or ohn hamness, divisional leader or he alvation Army Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Division

Hope program, developed in 2015, is set to be the largest treatment program in the Pacific, intended to help families break the cycle of intergenerational poverty and drug addiction by assisting them in securing stable jobs and housing, and in becoming contributing members of the community. What differentiates the program from others is its scope: Only large nonprofits, with vast holdings and decades of relationships with local governments and other organizations, are capable of providing what service providers call a “continuum of care,” a comprehensive system that tracks individuals over a longer period of time while providing multi-level services.

“Te Salvation Army does drug treatment for individuals in the facility, and has found that treatment programs are more successful than incarceration on its own,” Chamness explains. “People need a friend to walk alongside them through treatment programs.” Focusing on providing a community of support and accountability, the Pathway of Hope program guides, who are similar to life coaches, will partner with and work alongside individuals, rather than do the work for them. Te wait list for the program is lengthy. Te organization’s goal is to have 50 families and individuals participating in the initiative within its first year in 2016. Tey are also looking into developing clean and sober living houses, proven to keep many marginally housed individuals with addictions off the streets, and which are nearly non-existent on O‘ahu.