THE MIGRATION ISSUE DISPLAY UNTIL JULY 30, 2016 SUMMER 2016 MAUI’S ENDEMIC BIRDS PRAYER WARRIORS FACES OF ISLAM

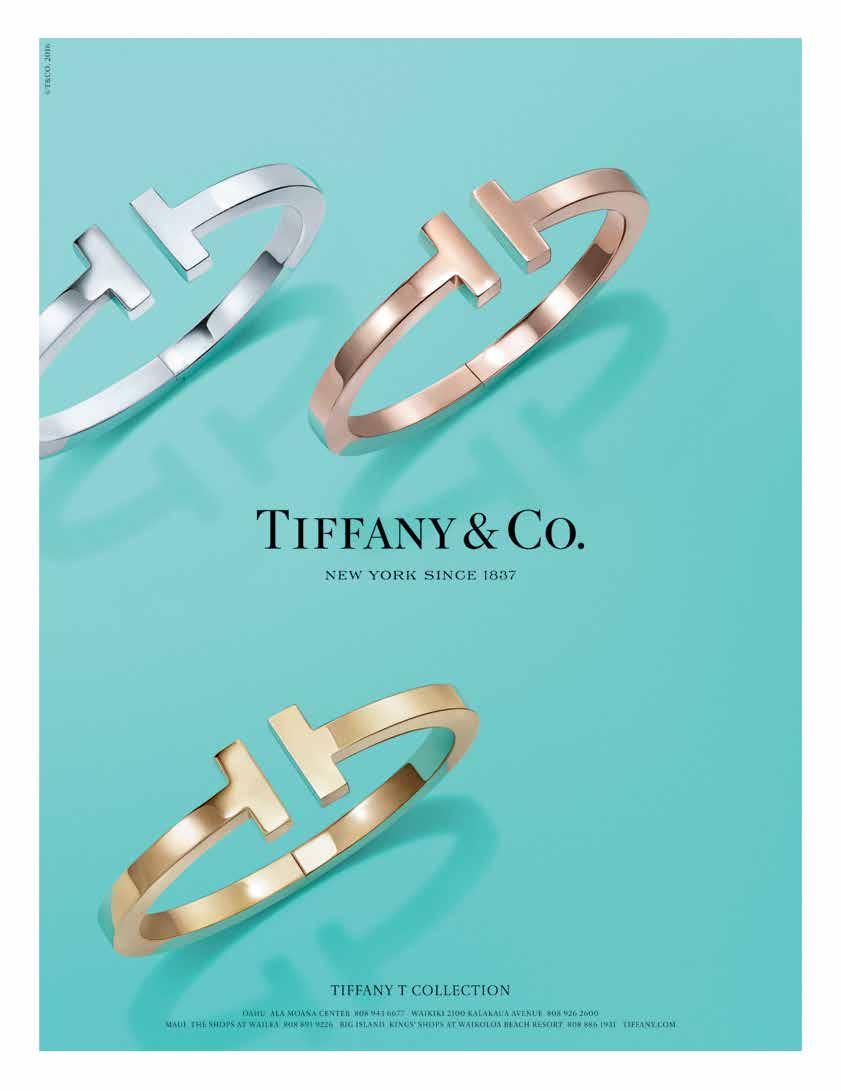

shop the exclusive ALOHA BANGLE

ALA MOANA NOW OPEN | ALA MOANA CENTER, EWA WING

LAS VEGAS Miracle Mile Shops • McCarran International Airport: D Gates

Grand Bazaar Shops • Grand Canal Shoppes The Palazzo | The Venetian

Fashion Show Mall, Open May 2016

ALEX AND ANI creates meaningful, eco-conscious jewelry and accessories to empower and connect you. We share a passion for the well-being of our planet, our communities, and our individual paths.

ALEX AND ANI creates meaningful, eco-conscious jewelry and accessories to empower and connect you. We share a passion for the well-being of our planet, our communities, and our individual paths.

MADE IN AMERICA WITH LOVE ® ALEXANDANI . COM

MADE

ALEXANDANI

IN AMERICA WITH LOVE ®

COM

TABLE OF CONTENTS

42 | Foreign Ambassador

As the senior geographer at the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of the American Indian in the nation’s capital, Doug Herman has become one of Hawai‘i’s most ardent cultural advocates—though he’s not native himself. Timothy Schuler examines the role of outsiders in native and minority communities.

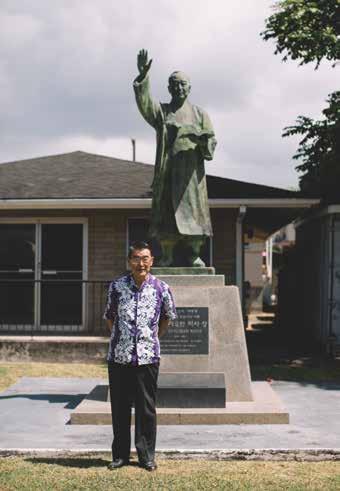

52 | Prayer Warriors

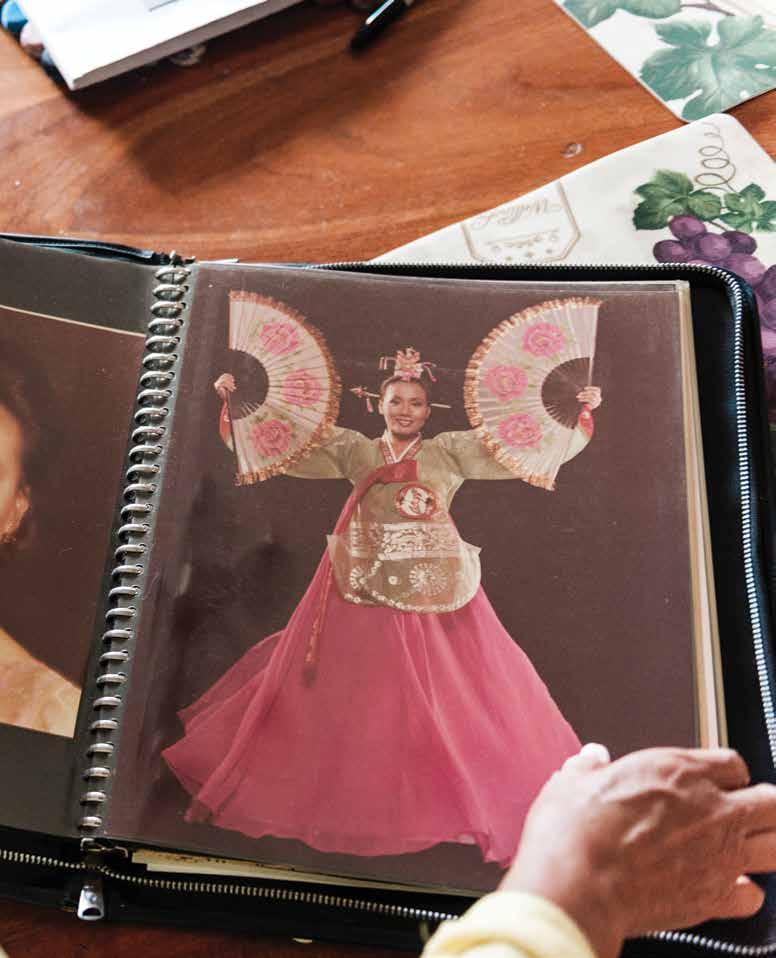

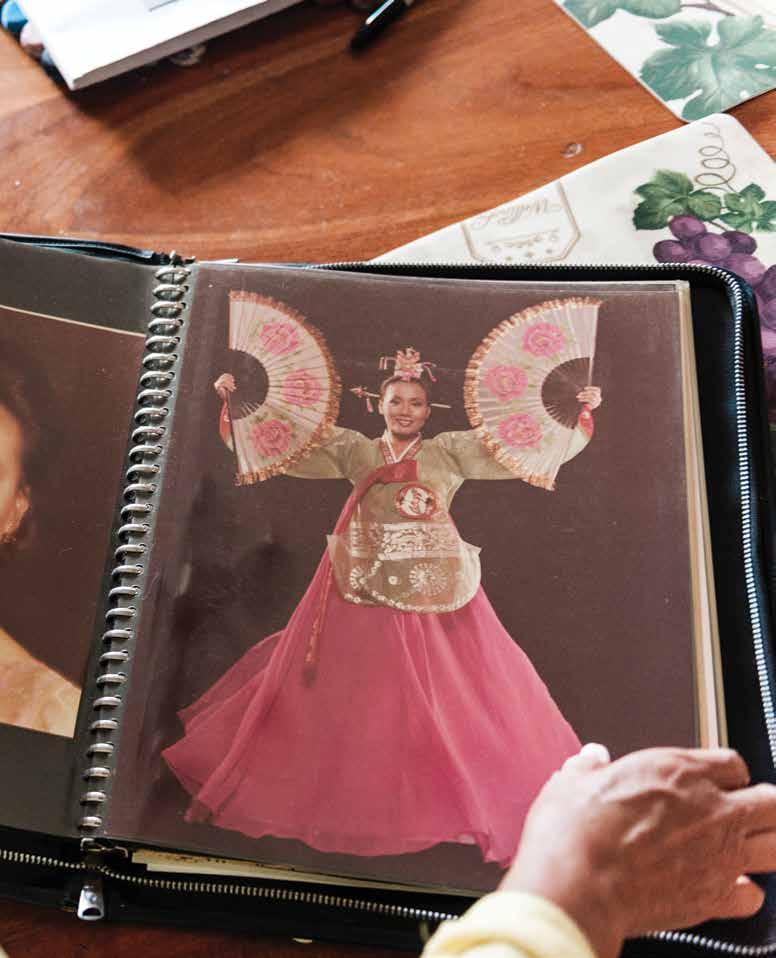

For Korean immigrants that arrived to Hawai‘i in 1903, the Christian church came to signify stability, camaraderie, and progress. Editor Lisa Yamada explores the relevance of the ageold institution in the isles.

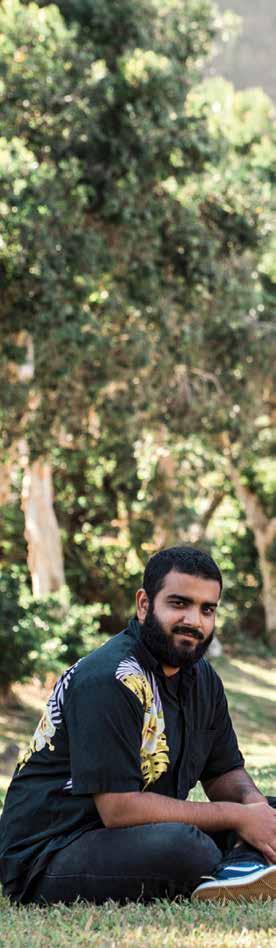

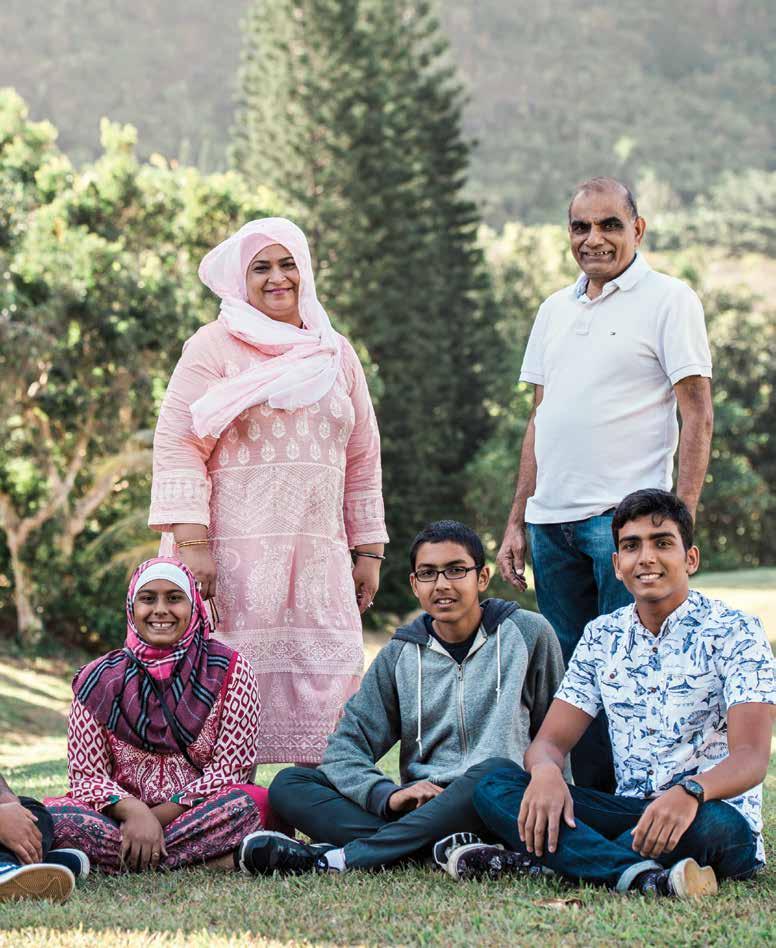

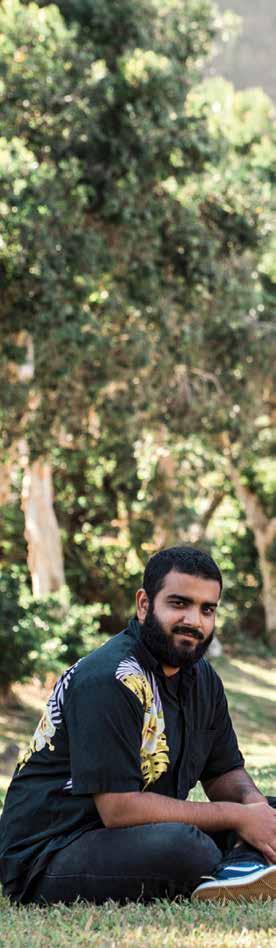

62 | Faces of Hawai‘i’s Islam

Unlike the simplistic, sensational picture the media draws of Muslims, those of Islamic faith make up a diverse, global population. Brad Dell talks to four such individuals who have made Hawaiʻi their home.

82 | Special Section:

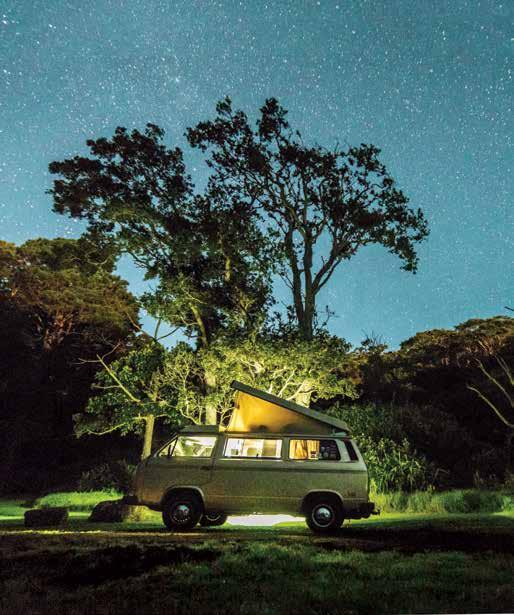

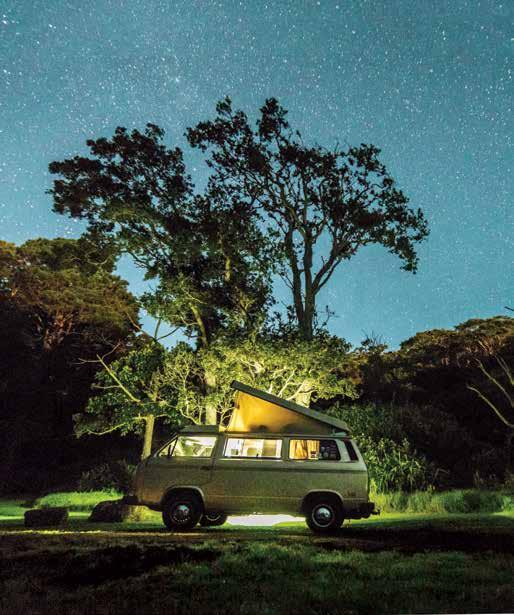

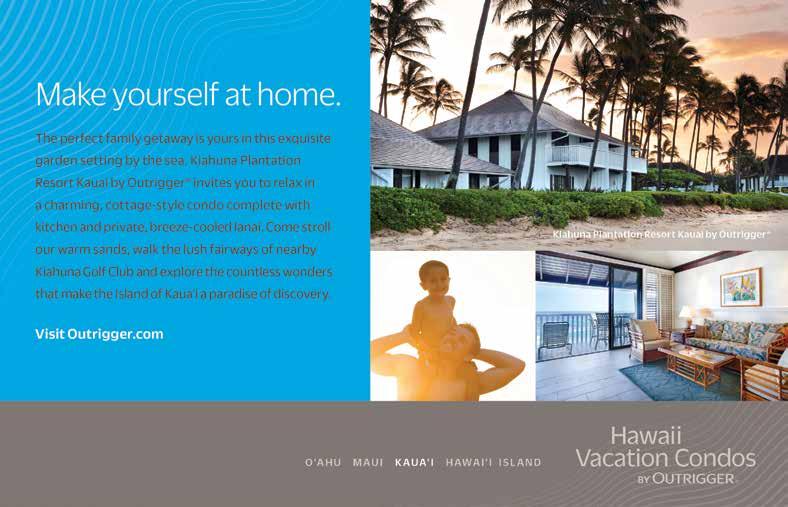

Escape!

It is only too easy to forget about the bounty of adventure that awaits in our own backyards. Discover refreshing ways to take a vacation in this special summer travel section, whether it’s exploring a remote location on a neighbor island for the frst time or looking diferently at a place we’ve known our whole lives.

| 30 |

Fight or Flight

By migration and by accident, birds arrived in the Hawaiian-Emperor archipelago of atolls and islands over the course of several millennia. Editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden explores how avian scientists just may save both bird and man from the efects of a warming world.

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

|

|

FEATURES

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

Letters to the Editor

18 | What the Flux?! Making Moves

24 | Art : Omer Kursat

28 | Art : Linny Morris IN FLUX 70 | Food : Olay’s Thai Express

74 | Food : Hide Sakurai 78 | Views : icronesia s igrant risis

Local Moco

As one of the last remaining sakadas alive to tell his tale, Cipriano Erice recounts what life on Hawai‘i’s plantations was like for Filipino laborers who arrived between 1906 and 1946.

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

FLUX PHILES

A HUI HOU

112 | Making Pâté de Lapin

| 20 |

VIDEO: CHASING BIRDS ON MAUI

In this video by Philip Lemoine, go behind the scenes with editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden and photographer John Hook as they accompany Maui Bird Recovery’s avian biologist Chris Warren through the Kula Forest Reserve on the leeward slope of Haleakalā on Maui.

ON THE COVER:

Shown on the cover is Nighat Quadri, who is part of the .05 percent of Hawai‘i’s population that declare Islam their religion. Quadri emigrated from Pakistan to the United States in 1997, after her husband won a lottery for immigration to America. Tough the Muslim community has been hurt by negative portrayals, Quadri says the people of Hawai‘i are welcoming. “I felt the spirit of aloha right away,” she says. Read Quadri’s story on page 62.

may be a quarterly, but we’re bringing stories all the time online.

STAY CURRENT ON ARTS AND CULTURE WITH US AT:

fluxhawaii.com facebook /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii instagram @fluxhawaii

NOTICE ANYTHING DIFFERENT?

Hey, we got redesign! Creative director Ara Feducia discusses the design inspiration and processes behind FLUX Hawaii’s new look.

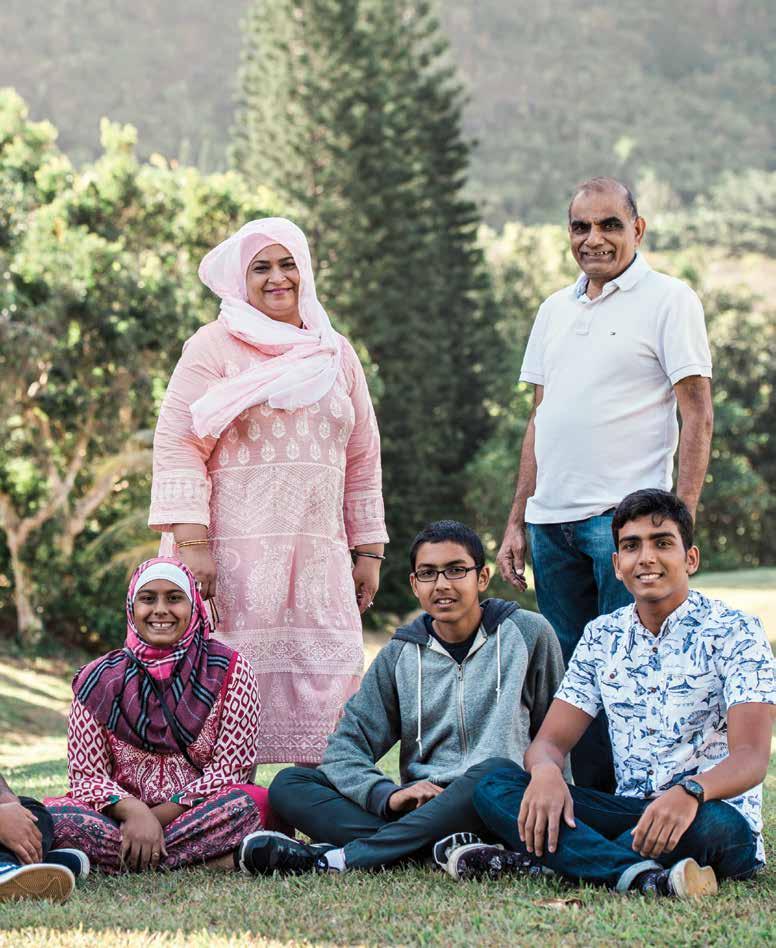

CONTEST: #FLUXROOTS

Tell your mom you love her. Tell your dad you care. Shout out your motherland and share with us the story of your migratory roots on Instagram, and tag @fluxhawaii #fluxroots between June 1 and June 20, 2016. A random contributor who posts during this time will win a FLUX prize pack.

Shown here is the Torres family, whose portrait was taken circa 1958, about 11 years after they arrived to Hawai‘i from Luzon island in the Philippines. The family’s patriarch, Primitivo, first came to Hawai‘i in 1946 to work for the Honoka‘a Sugar Plantation, and his family would join him a year later.

10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF

| FLUXHAWAII.COM |

CONTENTS

IMAGE SHOT BY JOHN HOOK

We

When grisly scenes from around the world confront our daily lives, we do our best to look away—to avoid seeing the blood in the streets, the blown out windows of buses and buildings, the shocked faces of those who have just escaped with their lives, the dejection of those waiting to start new ones.

Yet it’s all too easy to get caught up in the frenzy that arises from con ict. e b ild walls and reinforce borders to keep them o t to keep s safe. prime e ample and one that is fo nd right here at home early Hawai i residents signed a petition titled top yrian ef gees from entering Hawaii and the after o ernor Ige said the state would welcome these refugees in the days following the terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015. (This despite the fact that there has not been a single refugee involved in an act of terrorism in the United States since the country’s refugee resettlement program began in 1980; not to mention that all but one of the known assailants in the recent attacks in Paris and Belgium were European-born citizens, and all were raised in the EU.)

Fear is a powerful rhetoric. It was employed not so long ago on our very shores, when race prejudice and war hysteria marginalized an entire comm nity of apanese mericans. ap s a ap eneral ohn e itt famo sly said of internment. t makes no diference whether the ap is a citi en or not. nd while we like to tell o rsel es that hindsight is o are kidding yo rself if yo think the same thing will not happen again the late stice ntonin calia warned a group of University of Hawai‘i law students in 2014, predicting that the Supreme Court would eventually authorize another impediment on civil rights similar to that which happened with Japanese internment d ring orld ar . t was wrong b t wo ld not be s rprised to see it happen again in time of war. t s no stifcation b t it is the reality.

In Hawai‘i, it can be easy to ignore what is happening around the world, to quickly turn the page from the headline stories playing out far from our isles. After all, it is unlikely that the migrant crisis unfolding in Europe will ever reach Hawai‘i’s shores. But we can still put up borders, draw boundary lines around our neighborhoods, and cast blame on those who arrive in need. Nowhere does the cool shrug of indiference feel harsher than in the aloha state a place flled with migrants who traveled from Polynesia, Asia, and around the world. We are only too pro d to call o rsel es the melting pot of the acifc.

This, our Migration issue, celebrates the diversity of peoples— traveled from near and far—reminding us that no man is an island, and that we are all really foreigners, even in a place as familiar as our island home.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

o man is an island / Every man is a piece of the continent / A part of the main / Any man’s death diminishes me / Because I am involved in mankind.

—John Donne, Devotions Upon Emergent Occasions

The editor’s grandfather, shown left, with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team during World War II.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM EDITOR'S LETTER |

|

MIGRATION

How did you get here?

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

“My family emigrated from the Philippines when I was 7. As an American, my heritage is the foundation of why I believe teaching arts and culture to young people is important.”

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNER

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR - AT - LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Bryce Johnson

Jonas Maon

IJfke Ridgley

Haren Soril

“My Japanese and Chinese ancestors originally came to Hawai‘i to work on the plantations. My greatgreat grandpa, Young Anin, actually founded Oahu Market in Chinatown. I’ve always admired their hard work and humility.”

CONTRIBUTORS

Tess Bevernage

Martha Cheng

Brad Dell

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Christa Hester

Rebecca Pike

IJfke Ridgley

Timothy A. Schuler

Haren Soril

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns

MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Carrie Shuler

MARKETING & CREATIVE COORDINATOR

©2009-2016 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher.

FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro

OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Mitchell Fong JUNIOR DESIGNER

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

“My grandfather arrived to Hawai‘i from Munich, Germany by steamship more than 100 years ago to manage the old McInerny’s downtown retail store, eventually opening his own men’s shop at the current Ross location in downtown Honolulu.”

PUBLISHED BY: Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel Street, Suite A Honolulu, HI 96817

herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on hawaii.com as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| MIGRATION |

MASTHEAD

IJfke Ridgley

Born into a military family, Brad Dell has migrated every few years for most of his life, but decided to call Hawai‘i home because of his love for experiencing the myriad of cultures that have blended together here as a result of migrations from across the globe. He got to learn more abo t this in of c lt res while writing aces of Hawai i s slam on page . ears were shed d ring chats abo t the prejudices of media and people, and about the status of their homes, but there was plenty of smiling when talking about the tight-knit community of people with diferent backgro nds b t a shared faith shares Dell of his experience interviewing members of Hawai‘i’s Islamic community.

For O‘ahu local IJfke Ridgley, interviewing Cipriano Erice, one of Hawai‘i’s last remaining sakadas, or Filipino laborers, was a great way to peek into the history of the island story on page . t was surprising and touching what fond memories Cipriano had about life at the sugar plantation, and how modest he was abo t the role he played in its history she says. When not writing, Ridgley enjoys the challenge of making her photography as colorful and creative as possible, whether for fashion or tra el. s a shooting location she says Hawai i really is endlessly inspiring.

Timothy A. Schuler

Timothy A. Schuler

A contributing editor at Landscape Architecture Magazine, Kansas-born Timothy A. Schuler gained an appreciation for the natural environment from his parents (a landscape designer and soil conservationist), who took the family on annual vacations to some of North America’s most remote places. Schuler tra eled to one s ch location H ena on Kaua‘i’s north shore, to interview Doug Herman, a senior geographer at the Smithsonian and a Hawaiian cultural ad ocate. m certain now that part of the reason I was interested in telling Doug’s story is because, as someone who is not Native Hawaiian and who wasn’t born here, I continue to have questions about my role in Hawai i ch ler says.

I always read FLUX page by page, and this spring edition touched me in so many ways. My mother has been paralyzed on her left side for 10 years, and between my sister, daughter and me, we care for her. However, a few years ago, I arranged to have Yolanda stay with her from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. There is now a bond between them, and mom en oys her company. hat a diference in ha ing that social interaction since we are all on diferent b sy sched les

Keep up the great work!

Aloha McGuffie

16 | FLUXHAWAII.COM CONTRIBUTORS & LETTERS | MIGRATION |

Brad Dell

We welcome and value your feedback. SEND LETTERS TO THE EDITOR VIA EMAIL TO: lisa@nellamediagroup.com or mail to FLUX Hawaii, 36 N. Hotel St., Suite A, Honolulu, HI 96817 We asked our readers to post pics of their furry friends and tag them bestie. Here s a few for yo r viewing pleasure. You’re welcome. @ ALIIVET @ ISABELLA_N_BEAU @ KOSS__BOSS @ THISPUGOLIVE 77 76 “I think she tops,” says 91-year-old Jean Yamada her live-in caregiver, Lourdes Vivar Noble. “But she isn’t always tops.” bare whisper: “She gets awfully conceited if she thought was only saying good things about her.” Playful banter between Noble and Jean, says. wish could say the same,” Jean’s cheeky retort. While their relationship predicated on assertiveness and wit, it is calls loving, caring, and considerate of her needs. Is Noble tired? Jean encourages her to rest. “Very few clients are like her, most who views Jean and her family as her own. “Caregiving thinking of the other person instead of yourself,” she says. “You are giving yourself the other person.” early 2014, Jean (who is, in full disclosure, the grandmother FLUX Hawaii’s editor) was diagnosed with dementia. She moved temporarily her Noble first cared for her on part-time basis an employee of home care agency Attention Plus Care. Jean, who sometimes has trouble remembering names, came up what we were doing Mililani,” Noble ey also talked about the white moonflower that only blooms at night and thrown away, and said can make them live,” Noble recalls. at plant, after two months, bloomed. … And from then on she called me the Orchid Lady.” topped out at 18, her family decided one live-in caregiver could provide more ered the position to Noble, who accepted. Before moving into Jean’s home in ‘Aiea, Noble took month-long vacation to the Philippines, where she from. When she returned, she found Jean’s health had deteriorated. T dangerously low 86 pounds. Her family Working with the family and Jean’s parttime caregivers, Noble, like she had done and the coconut trees, and then she’d forget about saying she didn’t like to eat,” Noble What Noble’s nickname today? “Sexy Wexy,” says Noble, who demonstrates how she wiggles her hips when she exercises, or when she teases Jean make her laugh. never forgets that Sexy Wexy thing,” she says, beaming with pride and, even, hint NOBLE LADIES:

Correction page 36, Companions Issue: FLUX Hawaii incorrectly printed the name of the 15-year-old cowgirl. Her name is Caysie Medeiros, not Madeiros.

Making Moves

How did we get here? Facts on immigration, then and now.

COMPILED BY

ANNA HARMON

Hawai‘i was settled by immigrants from Polynesia who stayed so long that their culture and language became unique to the islands. During this time, the world population was both nomadic and sedentary, and national borders were in flux. In the 1800s, in the height of worldwide colonialism, immigrants from Europe and the United States arriving to Hawai‘i drastically changed the

way of life, both by greatly traumatizing the Native Hawaiian population and introducing a new political, religious, and economic system. This system needed laborers, and so immigrants largely from China, Japan, and the Philippines came to the islands. In 1898, when Hawai‘i became a U.S. territory, the flow of people to the islands began to be regulated by a federal system that was reactionary and

bigoted (take the Chinese Exclusion act of 1882).

Since then, policies have been implemented, quotas have been tweaked, and immigration continues to flow as people seek economic opportunity, easy retirement, healthcare, reunion with family, better lives for their children, escape from persecution, and refuge from natural disasters and war.

OVERVIEW:

46 ,782

Number of foreigners who moved to Hawai‘i from 2010 to 2015

18 %

Percent of small business owners in the U.S. who are immigrants. This is a higher share compared to U.S.-born workers.

Immigrants comprised 20.5% of Hawai‘i’s workforce in 2013, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. In the United States as a whole, there are almost as many immigrants in whitecollar jobs (46 percent) as in all other occupations combined.

HAWAI‘I:

250,000 foreign-born * (17.6% of total population; U.S. average is 13.3%)

* “Foreign born” includes naturalized U.S. citizens, green-card holders, refugees and asylees, certain legal nonimmigrants, and unauthorized immigrants.

UNAUTHORIZED IMMIGRANTS

DEFINED: Immigrants living in the U.S. without a visa or green card.

ECONOMIC IMPACT:

$31 . 2 million +

The amount unauthorized immigrants in Hawai‘i paid in state and local taxes in 2012

$7 billion+

The estimated amount unauthorized immigrants paid in Social Security taxes in 2005— benefits they will never be able to reclaim

GLOBAL WARMING

250 million

The amount of people anticipated to be displaced by climate change impacts worldwide by 2050. An estimated 665,000 to 1.7 million of these are estimated to be people from the Pacific.

WHAT THE FLUX | MIGRATION

|

HOW DID WE GET HERE? 1798 Alien Enemies Act: Authorizes imprisonment or deportment of male citizens from countries considered enemies of war. 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act: Prohibits the immigration of Chinese laborers. 1924 Immigration Act: Limits immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe to keep out those deemed “dangerous,” sentiments of the first Red Scare and eugenics movement. 1948 Displaced Persons Act: Relocates 400,000 displaced Europeans after World War II; four years later, Asian exclusion overturned.

1790 Naturalization Act: Excludes non-whites from eligibility to naturalize.

DEFINED:

Immigrants given entry to the U.S. with potential path to citizenship, including those relocating with sponsorship, to be with family or for work, those selected by lottery for diversity visas (countries with low immigration to the U.S.), refugees, and asylees, as well as naturalized citizens.

Since 1975, the U.S. has resettled more than 3 million refugees, with annual admissions figures ranging from a high of 207,000 in 1980 to a low of 27,110 in 2002.

59. 5 million

The number of refugees and asylees worldwide at the end of 2014, the highest ever recorded .

20 to 30 percent of refugees live in temporary camps. The average stay is 17 years.

NONIMMIGRANTS

DEFINED: Legal nonimmigrants are given temporary entry to the U.S., but have no path to citizenship (ex. temporary laborers, students), and include Compact of Free Association migrants from Micronesia.

*However, for Social Security cards, the U.S. treats COFA migrants as “lawfully admitted for permanent residence.”

4 , 812 , 993

The number of registered Syrian refugees as of March 16, 2016 13 , 947

The number of Hawai‘i residents who signed a petition on change. org titled, “Stop Syrian Refugees from entering Hawaii and the USA” after Governor Ige says Hawai‘i will welcome them.

1982 : 670 refugees

Top countries of origin: Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos

2014 : 2 refugees

Only country of origin: Burma

1 , 800

The number of Syrian refugees the U.S. has accepted since the crisis began, 62 percent of which are women and children under 12. President Obama says the U.S. will take 10,000 Syrian refugees in 2016.

US

1982 : 97,000 refugees

Top countries of origin: Cambodia, Vietnam, Laos

2014 : 69, 987 refugees

Top countries of origin: Iraq, Burma, Somalia, Bhutan

Immigration Reform Act: Seeks to prevent flow of undocumented immigrants to the U.S.

14 ,700

Estimated number of COFA migrants in Hawai‘i in 2013

Total COFA migrants in U.S. in 2008: 56,345 In Hawai‘i: 12,060

ECONOMIC IMPACT:

COFA migrants living in Hawai‘i pay all federal, state, and local taxes (from sales to income tax), payroll deductions, and other government fees, including social security, which they are ineligible to receive.

COFA migrants are ineligible to receive benefits such as financial assistance, food stamps and federal Medicaid. The few exceptions are that they can receive Temporary Assistance for Other Needy Families funds (an alternative to TANF); pregnant women and children can get Medicaid, and elderly and disabled can get statefunded medical assistance.

area. This is after the American military conducted 67 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands. Congress restricts COFA access to government programs in 1996. 1986 1975 Refugee Assistance Act: Evacuates 130,000 Vietnamese during Vietnam War. 1996 Illegal

strengthening border protections. 2003 Homeland

REFUGEE TOTALS US 2014 0 100K 50K 75K 25K US 1982 HI 1982 HI 2014 HAWAI‘I

Compact of Free Association: Gives Micronesian peoples limited access to the U.S. The compact exchanges this and financial assistance from the U.S. for military operation and bases in the

by

Security Act: Transfers the responsibility of immigration and naturalization services to the Department of Homeland Security.

IMMIGRANTS

LEGAL

GREATEST REFUGEE CRISIS TODAY: SYRIAN CIVIL WAR

Ø

All in a Day’s Work

Sakada Cipriano Erice recalls life on a Hawai‘i sugar plantation.

TEXT AND IMAGES BY

IJFKE RIDGLEY

As the sun rises on a Sunday morning over a crowded but quiet loop in Waialua, Cipriano ipi rice is wide awake and f ll of energy. He will be this year b t his infectio s smile and the twinkle in his eye makes him appear years yo nger. nd still dri e he says with a la gh. m l cky still ha e my mind.

Erice sits in his mint-green wooden house built right in the middle of the block—the same home he’s lived in since his arrival to O‘ahu in 1946—surrounded by other plantation homes that once housed workers of the Waialua sugar plantation. As one of roughly 6,000 Filipinos that immigrated to Hawai‘i after World War II, Erice is one of the only remaining sakadas alive to tell his tale.

agalog for laborers sakadas were ilipino workers contracted to work in the s gar plantations of Hawai‘i starting in 1906. By the 1930s, Filipino workers outnumbered Japanese, and by the time the final wave of workers arrived in 1946, more than 100,000 laborers had come from the Philippines alone. Leaving their lives and families behind, many of these immigrants came in search of better opportunities. They did, however, bring their Filipino customs along with them, forever changing the history and culture of Hawai‘i as a result.

As Erice remembers, it was an easy decision to leave Laoag, where he had lived in the northern Philippines. As a boy, Erice worked as a farmer and had little education. He was recruited by emissaries to the Philippines from the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association, and at age 23, made the 17-day journey across the Pacific aboard the SS Moanawili , along with his fo r brothers. he siblings landed in ia a i and si months later rice was transferred to a sugar plantation in Waialua on O‘ahu. he first day worked wanted to cry. wanted to go home. t was hard for me rice recalls of his early beginnings as a sakada. He started out weeding and cutting grass for the Waialua Agricultural Company, which meant strenuous manual labor and bosses who threw around numerous phrases that he didn’t understand. His luck changed when, about a month later, he was called in to take a test that would allow him to learn a specific trade, and he passed. y smile was from here to here says rice pointing to each of his cheeks beaming. Erice trained to become a welder, a role that he retained until his retirement in 1989, and soon earned the position of journeyman, a lucrative promotion that placed him at the top of the nine grades of plantation workers.

While Erice has mostly fond memories of the plantation, working in sugar in Hawai‘i was not a walk in the park. Employers demanded long work hours, enacted pay cuts often, and discriminated against workers based on race. When Erice first started at the plantation, many workers were paid ery little and co ldn t afford to send their children to college. o know how the boss treat s before he says. hey don t call yo r name. hey st say Hey boy e

By the 1930s, Filipinos like Cipriano Erice outnumbered Japanese laborers at Hawai‘i plantations, and by the time the final wave arrived in 1946, more than 100,000 had come from the Philippines alone.

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

LOCAL MOCO | SAKADA |

didn t like that so we started a nion. his union was a local chapter of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union, which represented workers in sugar and pineapple, as well as longshoreman and dockworkers. In 1952, all locales of ILWU joined forces. hen was in the nion had a high education [as a tradesman], so they gave me the hard job. I declined because it was hard to be a tro bleshooter rice e plains. Eventually though, he was convinced, and accepted both the role and its accompanying responsibilities. He became a union officer and began meeting with management and traveling to other plantations to fight the inequalities of the plantation system. By the 1950s, the ILWU had successfully instituted a 40-hour workweek, industry-wide medical care, sick leave, and paid vacations. Wages increased, and Erice is now proud to say that he was able to send all three of his children to college. always remind my kids it is important to study. Thanks to God, all three of them got an education. I’m really happy with that the sakada says smiling.

Nearly 30 years after retiring, Erice’s face still lights up when he talks about plantation life. liked the sense of comm nity. he company pro ided all what we needed says Erice, who recalls especially enjoying plantation-organized volleyball, baseball,

and basketball games for the workers every Sunday. His wife, Maring Erice—a quiet Filipina he met while on vacation to the Philippines, and brought back with him to O‘ahu years ago—pokes him in the back and interjects in Ilocano as he repeats himself. For decades, the close-knit community of Filipino sakadas lived in the ranch-style plantation houses alongside other Japanese, Chinese, and Spanish workers. The colaborers and neighbors often relied on each other to provide what the company did not, from sharing resources to celebrating special events. Found on the Erices’ back patio are long communal tables and a pig-preparation station, remnants of the old plantation days that the family still uses for hosting community get-togethers. Today, they are covered in bottles, the telltale signs of last night’s successful festivities. After 70 years in the neighborhood, the Erice house is still the center of the party.

After showing me his old stomping grounds at the Waialua Sugar Mill, Erice is off to his daily hour-long walk to the park. Or to drive his wife to church. Or to meet up with the surviving sakadas at the McDonalds in Hale‘iwa. Because for Cipriano Erice, life is still full.

Despite the arduous labor that Cipriano Erice faced on Hawai‘i’s sugar fields, his face still lights up when he talks about plantation life in Waialua, where he and his wife, Maring, have lived for more than half a century.

Cipriano Erice is the subject of A Sakada Story , the first of a three-part documentary series by O‘ahu-raised, Filipino-American filmmaker Maribel Apuya that highlights the history of Filipino culture in Hawai‘i. For more information, visit thesakadaseries.com.

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

In the Mom ent

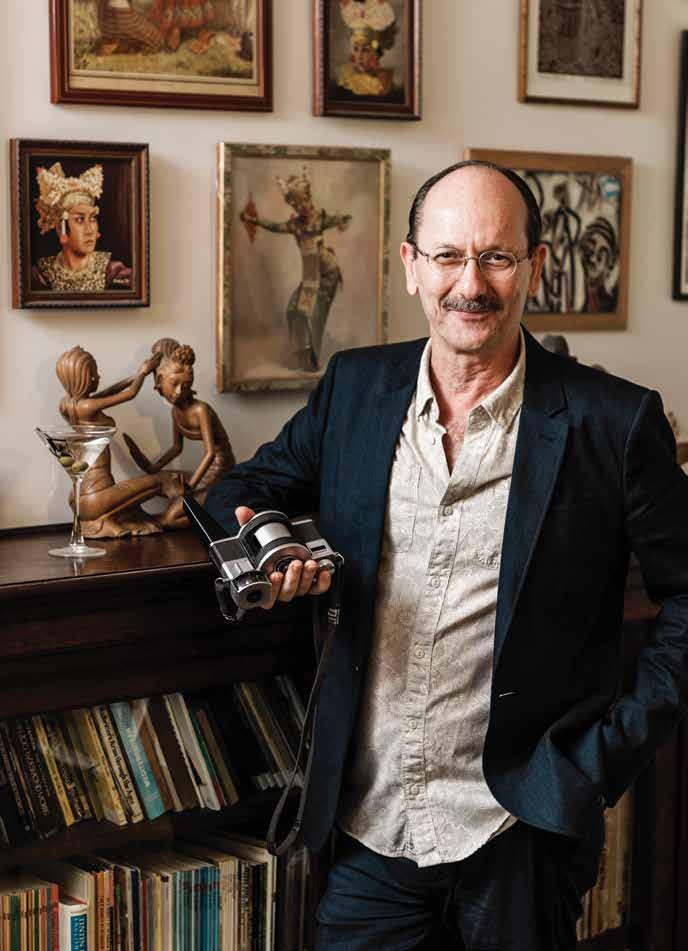

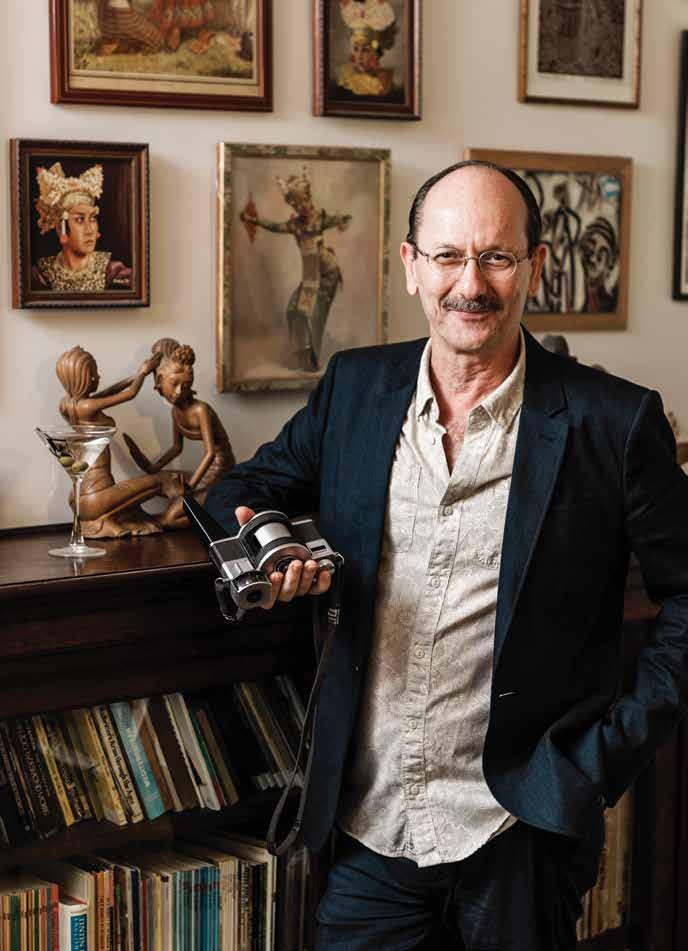

The son of a Turkish newspaperman, Omer Kursat captures scenes both forgotten and at the fore.

TEXT BY KELLI GRATZ

PORTRAIT IMAGE BY JOHN

HOOK

Photographer and publisher Omer Kursat drinks a celebratory afternoon glass of raki in a bar in Honol l s hinatown. t is rkey s national drink he says raising his small t mbler. hen rsat frst came to Hawai i in hinatown was not where one went for an imported apéritif. Years later, there are now several spots in the neighborhood to sip such an anisescented concoction, perfect for toasting a holiday, commiserating a breakup, or in Kursat’s case, celebrating the opening of an art show and the release of a new book. aki is meant to entice con ersation he says. hen tra el back to rkey to isit with some friends and drink raki the con ersation always gets really e cited. t a stif proof it s also helping rsat get o er a cold.

There is something lively about Kursat, messy and warm. His defined, well-groomed mustache bobs as he speaks, and his hands pantomime his enthusiasm. It might be the raki b t rsat is ali e in con ersation. y whole life ne er e er tho ght of myself as an immigrant he says. t recently with e erything that s been going on in the news kept thinking about how my father was originally from Crete and then moved to Turkey, so with that in mind reali e now was an immigrant before was e en born. rsat mo ed to the United States to attend the University of Southern California, where he graduated with a bachelor’s degree in computer science, and soon after, got hired as a software programmer at a bank. He worked there for eight years before coming to live in Hawai‘i with his wife, Dee. The co ple rented ee s sister s ho se in aim nalo and ha e been li ing there e er since. find myself c lt rally displaced sometimes he says. m not in rkey not in rete. m not ati e Hawaiian. o who am st consider myself an island boy.

Some of these questions of island identity are answered via Kursat’s widescreen photos. As a photographer, he is interested in living life in the present, capturing unexpected moments through the rotating-lens of his panoramic camera. Many of Kursat’s works illustrate the beauty of spontaneity—the candidness of things—including his first book, Over the Pali, 2 a.m., No Pork which capt res hinatown s cl b and arts scene from to . like the bl rry or the f y images low sh tter speeds where yo can barely make o t things rsat says. sing a Cold War-era, Russian-made, all-metal Horizont camera that he’s had since his teenage days in Turkey, Kursat shoots the complexity of a party scene, including the unfolding dramas in the backgro nd. he scope of the images adds a sense of grande r like a still from a mo ie a cinemascope or something he describes. was always a part of the scene people didn t really know was taking their pict re says rsat whose wide angle lens camera allows him to shoot without pointing the camera directly at his subjects. The off-camera gaze adds to

“I find myself culturally displaced sometimes,” says Omer Kursat, whose photographs help to answer questions of his identity.

“I’m not in Turkey, not in Crete. I’m not Native Hawaiian. So, who am I? I just consider myself an island boy.”

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX PHILES | ART |

the effect and narrative, elevating the oncederided genre of party photos to legitimate art. e always lo ed taking pict res don t know why. Maybe it’s sort of like a validation of o r e istence at that moment he says.

This preoccupation with setting moments on paper also reveals itself through Kursat’s publishing company, Deuxmers, through which he has produced seven publications, including poetry and photography compilations. The photographer is currently working on a second compilation of images salvaged from the collections of Peggy Ferris, a photographer and journalist who worked in Honolulu after World War II, as well as a collection of translated poems by an avantgarde Turkish literature collective known as The Second New.

Kursat’s work as a populist photographer and publisher is a natural result of his being the son of a journalist. Ege Ekspres (Aegean Express in English) was the name of Kursat’s father’s newspaper, which he started in a dangerous time. Originally from Crete, the Kursat family was forced to move to Turkey in the early 1920s as a result of the population exchange between Greece and Turkey during

the Turkish War of Independence. The partitioning of the Ottoman Empire forced emigration between the two evolving nations ia staggering iolence. y father was a very free-thinking, liberal person. It even landed him in jail for six months for writing a column that criticized the political party that was in power at the time rsat reflects. He is the reason I am the way I am. His influence shaped my perspecti e in life. Again, it might be the raki talking, but Kursat is a continuous stream of stories, jovial anecdotes of family adventures and North Shore weekends. In 10 minutes, he can recite tales of his first days in Hawai‘i, the sting of Manal Bay sea urchins at his family’s summerhouse in Turkey, rumors of Saint Nicholas; he even broaches the subject of exgirlfriends—and he’s just getting started. For a man that just celebrated his 60th birthday, he’s filled with as much energy as someone a quarter of his age. He carries the wisdom of someone who has taken long journeys across oceans, only to return to the place he now calls home.

Kursat remains preoccupied with capturing moments, like this one of carefree Nevra, a friend he photographed in 1970s Turkey whose image is one of 52 self-processed film photos in Kursat’s book Young Turks

For more information on Kursat and Deuxmers, visit omerkursat.com and deuxmers.com.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Morris Makes Contact

The descendent of an English merchant and Hawaiian royalty finds inspiration in fluidity.

TEXT BY CHRISTA HESTER

IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

Striding through the rainforest of upper Nu‘uanu, artist and photographer Linny Morris weaves past trees and down a sloping hill until she reaches a hidden waterfall of Nu‘uanu Stream. Her fingers swipe to unlock her phone and record the minute details that interest her: sparkling plumes of mist that rise from the waterfall and dissipate in the sunlight, specks of bubbles traveling over the water’s surface, floating fishnet patterns knit together by water and light.

Morris’ deep relationship with water was the impetus for her installation in Contact: Foreign and Familiar, an exhibition held in April at the Honolulu Museum of Art School that focused on c lt ral e change and migratory mo ements. y piece he onse ence of onfl ence was a looped ideo of freshwater and saltwater footage she says. orris who makes a li ing as a photographer specializing in editorial and architectural work and has a degree from Parsons School of Design, projected the video onto the ground and enclosed it in a varnished wooden box topped with a railing. The idea came to her while on a cruise in Alaska, during which she reg larly rested on the ship s railing while ga ing at the water. was mesmeri ed looking down at the water with the endlessly peeling white wake and the shifting reflections of sky and distant mo ntains she writes in her artist s statement for the show.

kept thinking how all the people come from ha e had this same e perience says orris whose family genealogy was passed down over years of oral tradition. Her paternal greatgreat-great grandfather, English captain Samuel Dowsett, sailed to Hawai‘i on the Wellington in 1828. Her paternal great grandmother, Martha Kahailani Holmes Dowsett, was the daughter of Kapelakapuokakae Kahalelaau, a pure Hawaiian chiefess whose Polynesian ancestors sailed to the islands centuries before. While these forebears shared neither skin color nor religion, they all knew what it was like to peer down into the deep Pacific waters.

It is this connection to water that allows Morris to bring her historically divisive Hawaiian, missionary and ropean blood together flowing in her eins in peace. o me water b ilds a bridge between these astly different peoples who were often di ided by history orris says. hey left e erything they knew the bea tif l land and life s staining freshwater to cross the ocean and find that same freshwater here in Hawai‘i. I can only imagine the fears they had crossing that great expanse, and how comforting it must have been to stare at the water peeling away from the essel.

Morris grew up feeling slightly removed from Hawaiian culture because of her haole looks and lack of cultural knowledge, but she is quickly finding her voice amongst other local artists such as Bernice Akamine, Kaui Chun, Joshua Lake, and Jerry Vasconcellos, whose works were all featured in Contact. his e hibit made me estion whether was Hawaiian enough to stand with these other artists, who have always sort of intimidated me with their c lt ral practice and correctness she says. ometimes feel g ilty for not ha ing learned o r language or dancing hula or knowing more about our history, but I’m at peace knowing that I’m honoring my Hawaiian ancestors through small rituals of daily gratitude and by observing, nderstanding and creating.

For photographer Linny Morris, water has come to represent the shared connection of her Polynesian and European ancestors, who crossed unknown ocean expanses to reach Hawai‘i’s shores.

To see more of Morris’ work, visit linnymorris.com.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX PHILES | ART |

F ight or F l ight

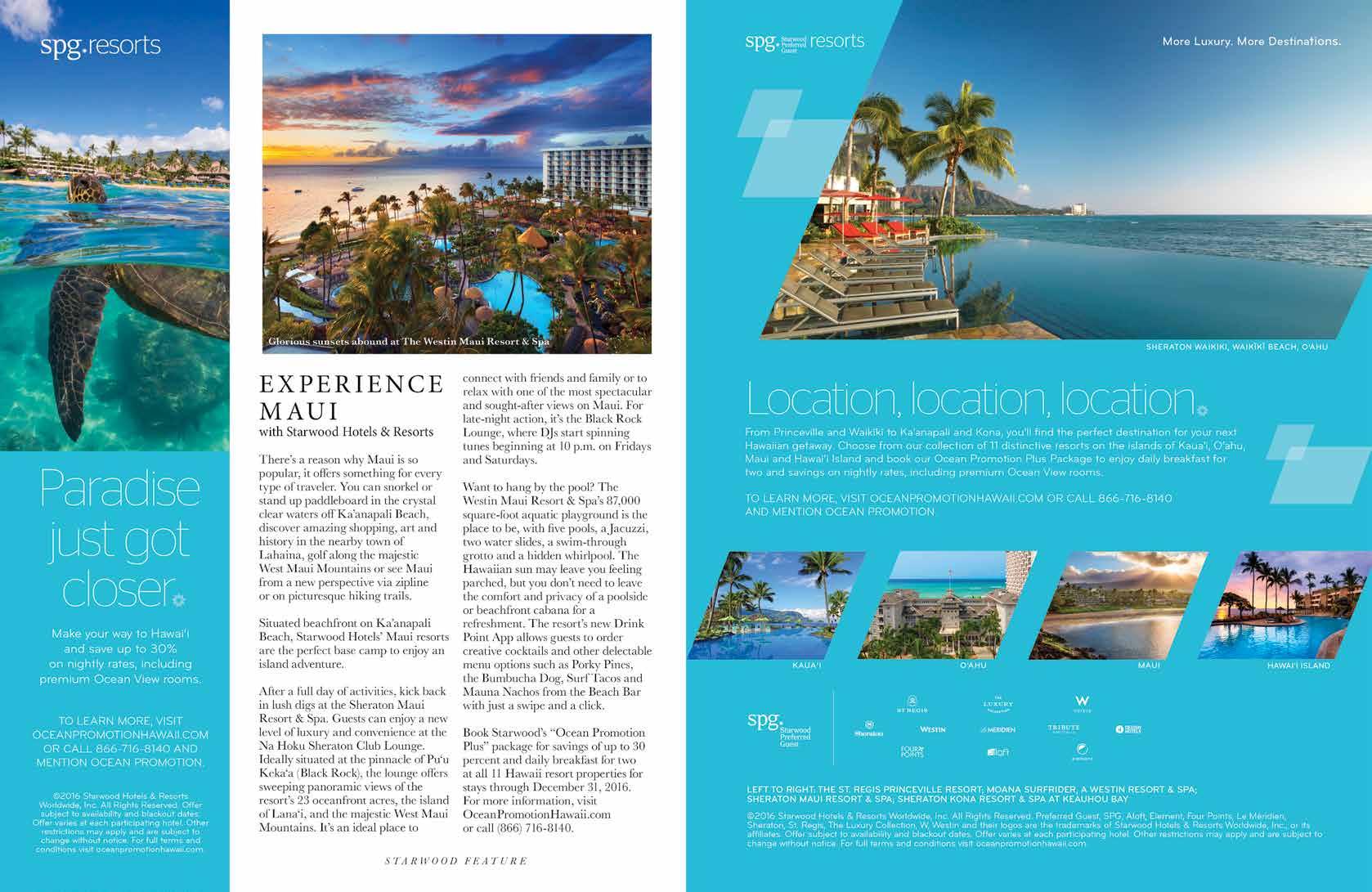

By migration and accident, birds arrived in the Hawaiian-Emperor archipelago over the course of several millennia. They evolved to create one of the most unique ecosystems on the planet. Since that time, most of Hawai‘i’s endemic birds have not survived humanity’s time on the islands. Now, at 6,500 feet above sea level, where cumulus clouds form, bird scientists are exploring sophisticated genetic biology and continuing evolution, which may save both bird and man from the effects of a warming world.

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

FLUX FEATURE

By the time Polynesians arrived in Hawai‘i some time after 300 CE, the islands were home to at least 110 separate species of birds found nowhere else on Earth. There were all sorts of creatures roaming the forest, like the great a i crake a ightless rail that h ng out in the understory; and the moa-nalo, an earthbound browser twice the size of a chicken, which must have been delicious considering its extinction coincided with the Polynesians’ arrival. Over centuries, Hawaiians named nearly every forest bird, as well as the numerous migratory birds that frequented the islands en route to faraway shores.

Of those 110 known species, only 48 still exist today, and many are critically endangered. The demise of endemic birds escalated in proportion to the migration of human settlement. As dry lowland forests were cut and turned to farmland by Native Hawaiians, and later made into towns, ranches, sugar fields, and airports by waves of Europeans, Americans, and immigrant laborers, the habitat for native birds was confined to what remained of the islands’ wooded peaks. here are reports from the 18th century of bird collectors saying, ‘I saw them in this kind of tree says hris arren avian biologist of Maui Forest Bird Recovery ro ect. f co rse they wrote that down after they shot them he laments.

Since those grim days, scientists, volunteers, landowners, and the state and federal governments have made significant efforts to save both Hawai‘i’s endemic bird population and the remaining forests they inhabit. This process has begun to utilize the cutting edge of genomic biology, what is referred to as the genomic revolution. In the 21st century, supercomputers have exponentially reduced the cost of mapping genomes. It took an international scientific community nearly two decades and $4 billion dollars to map the human genome, which was accomplished in 2003. With new technology, an individual animal, including human or bird, can have its genome mapped for approximately $100. There are implications for human welfare, as historically the expansion of biological science has led to discoveries and approaches that no one could have predicted: Moldy bread led to the development of penicillin, heating milk to the discovery of pasteurization. Saving an obscure

population of colorful, highly specialized forest birds in the middle of the Pacific Ocean just may lead to human survival in an unpredictably warming world.

LAST BIRDS OF THE FOREST

The sun has risen, but it’s still wet and dark as we drive in the shadow of the great mountain to Kula Forest Reserve on the leeward slope of Haleakal on a i. s part of a multi-step project to restore and maintain what is left of the original forest of Hawai‘i, and also to study health of Maui’s endemic forest bird population, Maui Bird Recovery Project is catching, studying, banding, and releasing birds. Led by Chris Warren, the day’s team consists of Erica Jernaill, a King Kekaulike High School senior adept at navigating the forest, field associate Bob Taylor, and Loren Cassin Sackett, Ph.D., an evolutionary biologist.

The ascent up the mountain provides a view of Maui’s vast interior valley, from ah l i to the north hei to the so th and the West Maui Mountains in the distance. ass me it happens e ent ally b t ha e you gotten used to the beauty of this place ackett asks arren. He responds as a scientist on an island where half of the pop lation is on acation his place is beautiful the way other places are. I just wish it was better preserved. … But seeing invasive species everywhere makes it less so for me. But I’m learning to take a step back, to see the forest thro gh the trees.

Chris Warren is a man of the feather. The two tattoos on his right forearm, which look like the readings of a seismic chart, are bird calls: one, of a warbler from Texas, where Warren got his master ’s degree, the other, of a Maui parrotbill, or kiwikiu, a pudgy honeycreeper with the business end of a giant parrot on its face. To catch birds, Warren employs a variety of techniques that would be familiar to the hahai manu, or specialized bird catchers, who once traversed these same forests. As a sort of modern hahai manu, Warren needs to think like a bird. After setting up their banding station, he finds several spots in narrow clearings of canopy that birds would need to cross, finding the path of least resistance from point to point.

The crew sets up wispy nylon nets in these aerial paths that forest birds might

The birds are fnding ways to s r i e fnding things to eat other than hi a nectar and discovering places to nest other than in native trees.

Maui Bird Recovery Project is studying an obscure population of birds in the Kula Forest Reserve, including the endangered ‘i‘iwi.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

follow. Stealthy as spiderwebs, the nets are suspended between two collapsible fishing pole rods. Some stretch 12 meters across. Unsuspecting birds are caught, gently decelerated, and sent tumbling into a cradle of nylon. As birds can be stuck in dangerous positions, nets are checked at least every 30 minutes, and are set in a perimeter around the temporary site that resembles a makeshift field hospital. When one is found, it requires deft hands to gather it in a soft cotton bag, where the bird flutters in capti ity. o acti ely catch a bird re ires a bit more effort: Warren sets up two speakers on either side of a net attached to his iPod, and plays a trick. The catch begins when a call sounds from one speaker, followed by the same call from the second. To a bird, it’s as if an invisible rival or mate has suddenly appeared and then flown to a nearby tree. The situation must be investigated. Warren cues the speakers as an ‘apapane, then an ‘amakihi, alight on a nearby branch before fluttering away. The ‘amakihi looks like a flying scoop of pistachio ice cream with a beak.

The Kula Forest Reserve is mostly nonnative, consisting of redwood and eucalyptus giants that were planted a century ago in an attempt to slow massive erosion caused by the harvesting of sandalwood and clear-cutting of the forest, and the ranching industry that followed. The eucalyptus was introduced for its ability to grow quickly. Unfortunately, the trees are brittle in tropical storms, and so every few years, the mountainside’s trails become an accumulated mess of dry, flammable tinder. Fires happen more than Warren would hope, and the smell of wood smoke from a fire that many think was maliciously set just a few miles away lingers in the air. his place has been f el loading since the last fire in arren says. Above 4,000 feet, it’s difficult to put a fire like that out with just helicopters. The trucks can’t get p here. hat st terrifies me.

Despite his fears, the forest maintains the aura of a cathedral. Mist descends through the dappled light where the road ends at Polipoli State Park. At dawn, birds can be heard clamoring and echoing through the fallen tree trunks. In 2011, several stateowned tracts of land on Maui were given greater habitat protection, paving the way for restoration. Even in this nearly entirely nonendemic forest, the birds are finding ways

to survive, encountering things to eat other than hi a nectar and disco ering places to nest other than in native trees. The Maui Forest Bird Recovery Project is one of several state and private organizations working to systematically, piece by piece and fence by fence, replant, protect, and manage the forest. At some point, through long-term planning and short-term funding, the forest will form a complete ring of functional habitat—a crown of green on Haleakal .

THE VAMPIRIC VECTOR

Evolved in the isolation of the vast Pacific Ocean, Hawai‘i’s forest birds are classic examples of adaptive radiation, or the diversification of one species into a multitude of new forms, like the Galapagos finches Charles Darwin wrote about at the outset of our understanding of genetics. The HawaiianEmperor seamount chain rose from the sea millions of years ago, where life evolved without humans and everything that humans brought along with them that has decimated birds: deforestation, roads, cattle, pigs, cats, and mosquitoes, which arrived in the islands in 1826.

In the 1930s, Hawai‘i’s endemic birds were ravaged by avian pox and avian malaria, both of which are transmitted by mosquitoes. These diseases are still here today. Because mosquitoes breed and thrive in tropical temperatures above 80 degrees, endemic birds are thought to be safe year-round at cooler ele ations appro imately abo e the mos ito line which is between to feet above sea level. As temperatures drop in the winter, birds can migrate to lower elevations nearer to 2,000 feet. But for the last several years, with temperatures rising around the world due to climate change, the habitat for mosquitoes has grown with the heat, while the habitat for native birds has dwindled. Equal-opportunity destroyers, mosquitoes transmit pathogens to nearly every vertebrate. For humans, mosquito-borne diseases, including malaria, dengue, and chikungunya, cause an estimated 1 million deaths globally every year. The bugs have been far more apocalyptic for island birds: Since its introduction, avian malaria is blamed for the extinction of many of Hawai‘i’s honeycreeper species (over half of which are now extinct), and also wiped out entire families of birds.

The bugs have been far more apocalyptic for island birds: Since its introduction, avian malaria has caused the extinction of entire families of birds.

Similar to the Hawai‘i ‘amakihi, the ‘alauahio, or Maui creeper, has been threatened by avian malaria at low elevations where mosquitoes thrive.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Most honeycreeper species have gone completely extinct at low elevations.

There are global initiatives underway to use genetic science to eradicate mos itoes or at least their efects. nfort nately the pests are hardy, resistant to chemical controls and the predation of other insects birds and fsh. onetheless scientists ha e performed s ccessf l feld tests in which local mosquito populations have been regionally wiped out, at least temporarily. The solution, it seems, is hampering the insects’ reproductive biology rather than eliminating larval or adult insects. Oxitec, a British biotechnology company, has experimented with the release of millions of genetically modifed mos itoes in feld tests in the ayman slands alaysia anama and ra il. he genetically modifed mosquitos throw a glitch into the life cycle of Aedes aegypti, or the yellow fever mosquito. Here is how it plays out: Male mosquitoes are harmless nectar-eaters, while female mosquitoes carrying eggs are the ones that bite. Oxitec introd ces males that are genetically modifed so that their ofspring cannot reach ad lthood. hen these modifed males mate with wild females the ofspring die before they can repeat the cycle. However, since tests have not been conducted on isolated islands, wild mosquitoes have quickly replaced itec s genetically modifed ones th s hampering their experiments. This hasn’t prevented Brazil, in the throes of Zika virus outbreak, to give the company the approval to commercially introd ce their genetically modifed mos itoes.

In Hawai‘i, one of the most remote island chains in the world, the ecology evolved without the little bastards. Because of this isolation, it is scientifically feasible to eradicate the problem entirely while continuing to monitor newly introduced populations. But any possible test would likely be met with public outcry here. Hawai‘i’s electorate has become wary of genetically modified anything, since multinational corporate farms have used the valley lands of Maui’s former sugar fields as the test site of genetically modified crops over the last several decades, including staples like soy, corn, and rice. With genetically modified mosquitos, there remains the possibility, which Oxitec refutes, of developing allergic reactions or virulent diseases from the bites (while Oxitec tries to introduce only males, a limited number of genetically modified females have been mixed in the released batches).

If the experiment works, it would have profound effects on the health of the humans and birds that reside on the islands. I am not the only person to have a fictitious, romantic conception of pre-contact Hawai‘i, rooted solely in the lack of b g bites. magine For centuries, an island surf session could be followed by an open-air nap without a mosquito bite that woke one from the deepest sleep.

SONG OF MAN AND BIRD

en so far arren says back at the forest counting the calls of ‘i‘iwi without ever act ally seeing one. ocali ations can be songs, say for mating or fighting, or calls, ways to check in a sort of declaration of e istence he explains as bees whirr overhead like an old air conditioner.

A hundred meters away from a clearing where the team holds camp, Warren plays bird songs through speakers connected to his iPod, attempting to catch an elusive study s b ect. almost had a H o er he whispers into a walkie-talkie. Avian biologists refer to birds by four-letter acronyms; a H is a Hawai i amakihi. e ca ght an o er here aylor responds referring to the only bird whose acronym is its name: the ‘i‘iwi, or scarlet Hawaiian honeycreeper, the iconic animal of the islands’ remaining forests—an exciting catch that sends us rushing back to camp.

Emerging from a cloth bag held by Taylor, the ‘i‘iwi is a showstopper, demanding attention with its color, which has the arresting capacity of a stoplight. Warren holds the bird in the palm of his hand as he prepares for the banding procedure, then using the gentlest of pressure between his middle and ring finger, he bands its legs, admiring its plumage as the bird whistles and chirps in indignation. The size of a man’s fist, an ‘i‘iwi is small and majestic. Knowing nothing of its cultural significance, the bold Hawaiian forest bird’s color and vocalization make it an obvious candidate as a spiritual being—the avian intermediary between man and the heavens. In fact, in Western context, angels are nearly always depicted with wings. n Hawai i many forest birds were a m k a including the fiery ‘i‘iwi, deified ancestors taking animal form.

ome re ered a m k a are gone fore er. he ah and Hawai i sland or yellow tufted honeyeater, were gorgeous coal-black songbirds with neon-yellow shoulder tufts and long, black, white-tipped tail feathers. feathers were caref lly pl cked by hahai manu, an essential part of the pre-Western economy in the islands, collected as a form of taxation and used by the elite to construct elaborate standards and symbols of religious and political importance. As part of the moho gen s specifc to Hawai i the last sang in 1987 on Kaua‘i, and has now been declared e tinct. long with the the mamo which provided the ali‘i’s black feathering, is also extinct. On O‘ahu, ‘i‘iwi are also thought to be gone. Every few years, birdwatchers still note a few which co ld be ad lts who ew from other islands. Kaua‘i is similarly barren of the birds. But today, the ‘i‘iwi being expertly handled here in the Kula Forest Reserve is very much alive. It is a boisterous, loud, mid-ranking bully among honeycreepers, known for chasing its genetic cousins around flowering hi a trees and pecking at ri als. Honeycreepers loudly proclaim their arrival at food and mating sites in the third person, so Hawaiians named the ‘i‘iwi after the bird itself as an onomatopoeia, as they did with the ‘elepaio. I can hear it now, between whistles and s eaks yelling iwi iwi the a ian e i alent of saying m enny owers nd am ery pset his g y is healthy. He co ld be between and years old arren says of the i iwi as Jernaill notes the observation. The bird’s hooked beak looks like it was modeled after the orange of candy corn. Over the course of the day, the group catches several birds: a few Maui ‘alauahio, which prove to be especially gullible to the double-speaker trick, two ‘i‘iwi, and a few Japanese white-eye, or mejiro, part of a population pet owners began setting free in the wild starting in 1929 that filled the niche left vacant by extinct species. Warren explains how to release a small bird: gently grasp its neck from behind with your pointer and middle finger while cradling its legs with your other hand. Then, open your hands. Surprisingly, some endemic birds are recovering despite the prevalence of mosquitoes. Sackett is attempting to determine how this survival is happening. Her previous work, studying prairie dogs,

The bold Hawaiian forest bird is an obvious candidate for a spiritual being— an avian intermediary between man and the heavens.

The

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

red-billed leiothrix is found in the Kula Forest Reserve.

attempted to understand the animal’s resistance to bubonic plague via the lens of genetics. In recent years, researchers and birdwatchers have seen more ‘apapane and ‘amakihi in lower elevations on Maui and Hawai‘i Island. These species appear to have become moderately resistant to avian malaria. How the heck are they doing that ackett asks incred lo sly as we wait to catch birds. f that estion can be answered, it would help the other birds, which share a genetic ancestor. ackett has two theories ne that certain members of the pop lation preg late meaning that the cells of these birds’ immune systems react to the pathogen, allowing them to survive. Two, that there is a recent mutation that makes the pathogen inert, or in other words, the bird has evolved. The possibility of a genetic basis for resistance—of evolution—is exciting, as it has occurred in the relatively short time of approximately 30 generations of birds. Determining these pathways to survival in a small population can lead to developments for other species. From the blood samples collected today, Sackett will determine the genetic signatures of the birds and if there are any traces of avian malaria, as well as their mechanisms for survival. The data s ggests ca tio s optimism that the ʻapapane and ʻamakihi have adapted, or evolved, to resist the pathogen. kay this g y s ready to go arren says smoothing the nape of the ‘i‘iwi’s ruffled feathers before handing it to Jernaill. Clasping the small bird with extended arms while making her way to a clearing a few meters away, Jernaill proceeds carefully, as if walking down the aisle of a cathedral holding a chalice after mass. She stops at the clearing and opens her hands. The ‘i‘iwi takes off toward the canopy, whistling and declaring its name while streaking skyward, then disappears into the mist.

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Foreign Ambassador

Geographer Doug Herman has traveled throughout Hawai‘i, researches and writes about the canoe as the islands’ most potent cultural metaphor, creates world-class exhibits about its people, and speaks Hawaiian fluently. He does all of this from more than 7,600 miles away in Baltimore, Maryland.

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY BRYCE JOHNSON

Despite being non-native himself, Doug Herman, senior geographer at the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of the American Indian, has become the ambassador for Native Hawaiian communities in the nation’s capital, even as the role of outsiders continues to be debated.

FLUX FEATURE

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

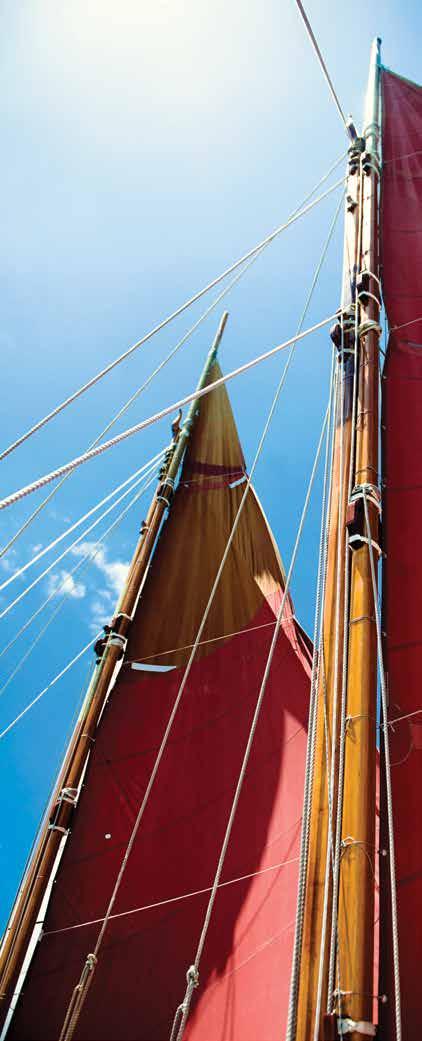

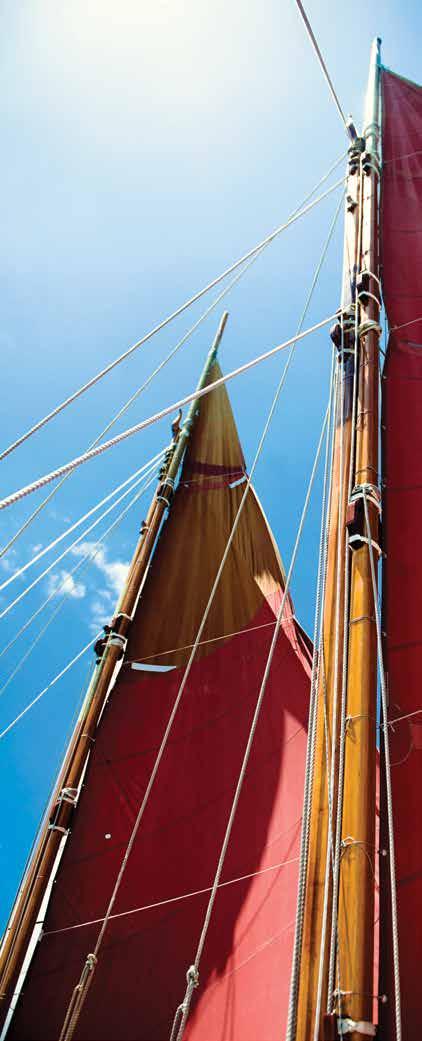

Do g Herman is ner o s. n f e days, he will sail from Honolulu Harbor to Hilo Bay on a three-day journey aboard the Hikianalia, the sister vessel of the famed voyaging canoe, Hōkūle‘a. The 56-year-old geographer has been fascinated by Polynesian voyaging since he arrived to teach at the University of Hawai‘i at noa in st eight years after members of the Polynesian Voyaging Society sailed Hōkūle‘a from Hawai‘i to Tahiti, thus disproving previously held theories of Polynesian settlement. But the Hikianalia voyage will be Herman s frst on the open ocean. ha e been giving talks on traditional navigation [for years], but I have no real, physical knowledge of even being on the boat away from the dock says Herman who sits cross legged on a rattan sofa in a cozy holiday rental on Kaua‘i, the island on which he’s chosen to conduct interviews for a separate research project. want to be able to translate all this book knowledge and embody it.

Herman is the senior geographer at the Smithsonian Institute National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. He is also the creator of acifc orlds an indigenous geography project that works to preserve traditional cultural knowledge thro gho t the acifc slands and package it into a place-based curriculum for educators.

Although he lives in Baltimore, Maryland, Herman’s research has, for the past 25 years, foc sed e cl si ely on Hawai i and the acifc Islands. Beginning in 2009, he spent three years researching traditional canoe-making for a major exhibition for the Smithsonian titled Aloha Aina: Hawaii, the Canoe, and the World, conducting more than 100 interviews with contemporary navigators, carvers, artisans, featherworkers, society leaders, activists, and scholars. Around the same time, he built his own 16-foot outrigger canoe (based on plans by famed multihull boat designer James Wharram) and chronicled the experience for the Smithsonian’s blog. For centuries in Hawai‘i, kahuna kalai wa‘a, or master canoe builders, were talented elites with sacred knowledge of how to turn the natural arbors of the land into sleek, durable vessels of the sea. ferings were made at the base of the tree to the gods, with prayers, a small black pig cocon t red fsh and awa a ceremonial be erage more commonly known as ka a Herman wrote on his blog in ne . or a

bigger and more important canoe for a noted chief a h man sacrifce might be deemed necessary.

Over the years, Herman has become an no cial ambassador of Hawai i writing for a national audience about such things as the cultural implications of building a new telescope on Mauna Kea on the Big Island, or the Polynesians’ place among history’s greatest na igators. olynesian migration resides among the greatest single human ad ent res of all time Herman wrote for the online edition of Smithsonian Magazine. Here were small island peoples sing stone tools, crafting rope from coconut husks and stitching pandanus leaves into sails to build an ocean-going craft that could journey 2,500 miles and back again.

Although Hikianalia’s voyage from O‘ahu to Hilo should be a cakewalk compared to those early voyages as the double-hulled canoe was outfitted with engines and GPS Herman feels a slight trepidation at the prospect of crossing the len ih h hannel a mile strait between Maui and the Big Island that is generally regarded as the most dangerous channel in the Hawaiian slands. hen told the Polynesian Voyaging Society guys that that’s the leg I wanted to do, they said, ‘You’re doing that one? You’re gonna need some gear Herman recalls. he channel s name ro ghly translated means great billows smashing and winds in this stretch of the Pacific, which are funneled between the twin peaks of a na ea and Haleakal on Maui, can reach 50 miles an hour, with swells topping 40 feet. It’s not just the danger that weighs on Herman’s mind. The trip is something of a test for the scholar, whose ultimate goal is to secure a spot on a voyaging leg of the Hōkūle‘a, currently in the midst of a oyage aro nd the world. ha e to pro e that I can survive on a canoe before they’re gonna p t me on a real oyage he e plains.

For now, Herman is trying to focus his mind here in H ena on a a i s north shore. The community is one of seven sites Herman has documented as part of Pacific Worlds, which spun out of a program launched by the Smithsonian in 1999 to help bridge computer technology and traditional cultural beliefs and practices—two things that, at the time, seemed diametrically opposed in many native communities in the United States. Herman initially worked with a Hopi community in

ha e been giving talks on traditional navigation, but I want to be able to translate all this book knowledge and embody it.

Herman’s research has focused exclusively on Hawai‘i and the Pacific Islands for the past 25 years.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Arizona on the project but quickly saw its potential for the Pacific Islands. He launched Pacific Worlds in 2000, weaving together geographic research with myths and oral histories told to him by elders and community members.

Voyaging, of course, played an important role in the curriculum, which has been adopted by institutions throughout the acifc from elementary schools to colleges. The topic of Polynesian migration was one of the frst lessons st dents learned and discussed. Herman hoped the project would inspire others to follow in acifc orlds footsteps, which for a while seemed likely to happen. t was all going really well ntil No Child Left Behind came along and wiped o t all the f nding for c lt ral ed cation he remembers. Years later, Polynesian canoe culture is woven into schools throughout Hawai‘i, and Herman aims to reboot his project with an added emphasis on climate change. here s that Hawaiian pro erb hewa‘a he moku, he moku hewa‘a, ‘the canoe is an island the island is a canoe he otes. limate change is reminding s that the world is an island.

Hawai i. didn t know anything abo t Hawai i b t was really interested in sia he says. Reading it, he found a place where he might ft in b t his application wasn t accepted. he ni ersity of Hawai i at noa howe er ga e him a teaching assistantship. Herman used what he learned to write about the similarities between Buddhist principles and the cultural practices of many acifc slanders b t in 1984, he had his sights set on Asia, envisioning a career in economic development or urban planning in India or China. For Herman, Hawai‘i was just a stopover.

As early as he can remember, Herman has been drawn to cultures other than his own. He grew up in Washington, D.C., in a home flled with sian art and stories of his father s time in Japan, where the longtime moderator of Face the Nation lived while covering the Korean War as a CBS war correspondent. Herman inherited his father’s fascination with all things abroad, and became even more interested after learning about Eastern religions in school. At Dartmouth College, his father’s alma mater, Herman majored in religion and spent two months at an orthodox Chinese Zen monastery in Northern California. There, waking up at 3:30 a.m. and eating just one meal a day, spiritual practice became more than an academic pursuit. It would transform Herman’s life. When he returned to Dartmouth, what had already seemed foreign now seemed totally alien. was conf sed by the al es of merican culture. It wasn’t making sense to me, partic larly at this preppy college he recalls. Nearing graduation, Herman came across a poster advertising the East-West Center in

Two years into his master’s degree, however, the adventurous geographer went on a solohiking trip along a a i s ali oast to the remote alala alley marking his frst encounter with a wilder, more pristine Hawai‘i. He recalls reaching a high point in the valley and being dwarfed by its cathedral like clifs where he had a second epiphany. knew, as I looked out from a high point in the middle of the valley, that the closest landfall in that direction was [Russia’s] Kamchatka enins la tho sands of miles away he says. hinking abo t the frst olynesians to set foot in Hawai‘i, and what it would have been like to cross the ocean in a canoe, he gained a new respect for their way of life. He returned to Honol l and went straight to the o ce of Abraham Pi‘ianai‘a, the director of UH’s Hawaiian Studies program at the time. After less than an hour, Asia was a distant memory. For Herman, Hawai‘i was now the focus.

Like so many other migratory creatures, Herman eventually returned home. In 2007, he oined the staf at the ational se m of the American Indian, writing scholarly articles, editing a variety of books, and occasionally teaching museumgoers about the materials used in ancient Polynesian voyaging. But the fact of Herman’s ancestry—that he isn’t American Indian or Native Hawaiian himself— has created con ict. y m se m does not recognize me as an ambassador of Hawai‘i beca se m not nati e Herman says. hen he recently suggested that he demonstrate traditional Hawaiian canoe carving at a festival devoted to Hawaiian culture, the Smithsonian’s organi ers dem rred. hen p sh came to sho e it was beca se m not Hawaiian according to Herman.

The biggest blow came when, for reasons that were never explained to him, the Aloha Aina exhibition—which he had

art of it

and I’ve only realized this in recent years— is that I don’t really identify with white American culture. I ne er ha e.

H ā‘ena on Kaua‘i’s north shore is one of seven sites Herman has documented as part of his Pacific Worlds project, which he hopes can bridge computer technology and traditional cultural beliefs and practices.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

been spearheading for three years—was ne pectedly canceled. t st s ddenly phwoot! disappeared off the sched le Herman recalls. (The decision may have stemmed from a growing desire in Native Hawaiian communities to be treated as an independent nation, and to not be lumped in with the American Indian tribes of North America. Museum staff, however, did not confirm a specific reason for the exhibition’s cancellation.)

These situations have arisen with more regularity, as the role of outsiders in native and minority communities—informed by centuries of colonialism and trauma—has been debated for decades. Most recently, Black Lives Matter has brought the debate to the fore with white allies being asked to stay of the megaphone as one set of instr ctions at a Boston protest put it, and Herman has earned the trust of the community by doing just that. ch of the te t incl ded in the acifc orlds curriculum comes directly from community leaders, and Herman gives his interview subjects near total control over what ultimately is published. But he has encountered skepticism along the way. When he does, Herman often relies on his academic pedigree. n Hawaiian c lt re e erything is based on genealogy, so in certain settings, I will recite my [academic] genealogy, which is Abraham Pi‘inai‘a, Rubellite Kawena Johnson, Puakea ogelmeier and ll do it in Hawaiian says Herman who speaks the lang age ently. n the s d ring what he calls the s per hot days of the so ereignty mo ement when Haunani-Kay Trask, an oft-quoted indigenous rights activist, was the director of the Hawaiian Studies program—Herman was more than a little aware of the color of his skin. t was a ery di c lt time to be white and particularly a white male scholar doing ati e Hawaiian st f he says. managed to y nder the radar partly beca se was learning Hawaiian. Part of it—and I’ve only realized this in recent years—is that I don’t really identify with white American culture. I never have. I’m somewhere in the middle in my sense of myself. So I just didn’t feel like [they were] talking about me. But I knew that they could be, and that that gun could be pointed at me. And that gun has been pointed at me o er the years. t only brie y.

For some, ancestry is unimportant. At a comm nity workday in H ena se eral

members of the local environmental group Hui Maka‘ainana o Makana told Herman that the comm nity is not defned by race. he comm nity they said is whoe er shows p. Few have demonstrated this attitude more powerfully—or personally—than Lynette Hi‘ilani Cruz, an anthropologist and kupuna in residence at Hawai i acifc ni ersity who adopted Herman into her family as her h nai brother. Cruz, who has been involved with the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, met Herman years ago and says she was str ck by his understanding of Hawaiian history and [his] s pport for the kind of work we were doing. Over time, their relationship deepened, and one day, Cruz proposed that he join her family. think he was taken aback by it she says. eca se that s a big deal yeah f the decision r adds t s not a head thing. t s a g t thing.

For Herman, there could be no greater symbol of acceptance. And yet he also accepts that he still may not have a place among all local scholars. hey don t need me he says. y role think is to comm nicate to the rest of the world. pecifically r says Herman is an important voice and resource in the capital. When he left Hawai‘i for Washington, D.C. she told him there was a reason for his being there. A few years ago, at least one of those reasons became clear.

In 2012, Cruz and several other activists traveled to the country’s capital to raise awareness about the 1897 Ku‘e Petition, which was uncovered by scholar Noenoe K. Silva in 1996. The petition had garnered more than 20,000 signatures from Hawaiians who opposed U.S. annexation. Among the events involved in the trip was a dramatic reenactment of a meeting between members of the Hui loha ina a gro p of women who had organized in support of Queen Lili‘uokalani. Herman helped Cruz secure a venue for the reenactment and, because he speaks Hawaiian, e en played the role of the minister. he minister was part haole so o g act ally ft the part r says with a la gh.

Today, a copy of the Ku‘e Petition is on display as part of E Mau Ke Ea: The Sovereign Hawaiian Nation , an exhibition on Hawaiian sovereignty that spun out of Herman’s work on Aloha Aina . The exhibit, which opened January 2016, will run through 2017 and will be on display when the Hōkūle‘a reaches D.C. in May 2016. In honor of its arrival, the

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

museum has planned a slew of special events, but Herman isn’t sure he’ll attend. He hopes to be on the canoe itself. hat s a better place for me he says.

When Herman arrives at the Marine Education Training Center in Sand Island, the Hikianalia is nowhere in sight. The crew—a mix of longtime voyagers and new initiates— has little choice but to wait. Some make last-minute supply runs. Others sleep or talk story. It’s dark by the time Hikianalia fnally arri es having been delayed by an nsched led stop in ai nae. Because of the late start, and strong winds out of the east, the canoe has to be towed all the way to Maui by the H ‘ kela a chartered fshing boat. On day two, the crew fnally sets sail and things go smoothly—until they reach the len ih h hannel. As the sun sinks behind them that second night, winds whip the water, churning out the giant black billows for which the channel is named, and causing the canoe to pitch as it crests the now 15-foot swells. Despite the technology onboard, navigators on the Hikianalia rely on the sun, stars, and waves to chart the canoe’s course. Using these methods, watch captain, Heather Nahaku Kalei, who sailed from Samoa to New Zealand on the Hōkūle‘a in 2014, realizes that the canoe has been pushed off course. The crew needs to bear northeast. t when we try to tack we can t t rn the canoe Herman recalls. The winds are too

strong. Two crewmembers also are out of commission.

ne s seasick and the other s knee had gone o t he says. o they were waking s p for half-hour shifts, between midnight and 6 a.m., to come o t and help.

The crew never reaches Hilo. That night, the captain, Ben Perkins, gives the order to tow the canoe once again, this time to the closer Big Island destination of Kawaihae, which the Hikianalia reaches without further incident. Despite the trials, Herman is not dissuaded. In fact, he feels an even greater desire to join the crew of the Hōkūle‘a, and recalls the high point of his trip, when on a particularly clear night beneath the stars, he is posted at the steering paddle. Kalei instructs him to hold the course. He looks up at the sky to find Mars glowing brighter than any star, and uses the planet as a guide, holding the canoe steady so that the planet remains just above the railing. his is what d been lecturing about, how to navigate and hold a course relati e to the stars he says.

The significance of this moment recalls the journey Herman undertook more than 30 years before at the monastery, when an intellectual pursuit became a lived experience. As Herman wrote in an essay that appeared in 2013’s A Deeper Sense of Place: Stories and Journeys of IndigenousAcademic Collaboration elief and faith are means … but are not ends in themselves. Texts show the way, but one still has to make the trip.

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

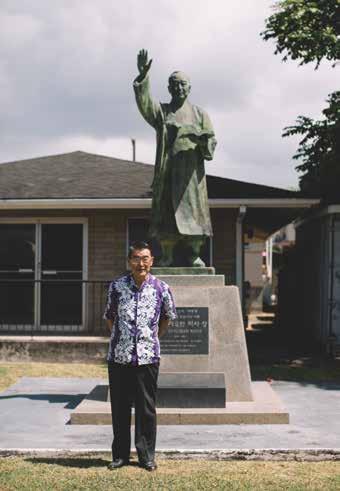

Prayer Warriors

For the Korean immigrants that began arriving to Hawai‘i in 1903, the church came to signify stability, camaraderie, and progress. Today, as the relevance of an age-old institution continues to wane, Korean devotees meditate on meeting the needs of an ever-changing community.

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & JONAS MAON

FLUX FEATURE

Koreans, we go out punching, then think later says omiko k ee a Korean who moved to the United tates in . don t know if by kimchi or what, but … we get so hot, sometimes it’s unreasonable. But we don’t even think about it. It’s kind of a character of oreans.

This spiciness makes sense in the context of Korea’s history. Known as Choson, or Land of Morning Calm, the mountainous peninsula of Korea has been anything but tranquil. Historically it is a sandwich nation according to Bong Rin Ro, Ph.D., a professor of church history at the Asia Graduate School of Theology on Makaloa Street in the area known as oreamok . t s a term he ses to refer to a place squeezed by world powers fighting over control of the strategic region. Over millennia, rule of Korea has shifted from China to Japan in a perpetual game of tug-of-war. Other nations, such as the Soviet Union and the United States, have joined in the contest at various times. The rope frayed so much that the country has split in two.

Amidst all of this turmoil, in the late 1880s, Protestant Christianity—as well as capitalism and Western culture—came to the peninsula in the arms of American missionaries. Within a couple of decades, Koreans began immigrating to Hawai‘i. Churches became shared places of worship, marks of kinship, and outposts for Korean liberation in the years to come. Today, only about 3.5 percent of Hawai‘i’s population, or just over 48,700 people, identifies as full or part Korean, according to U.S. Census data in 2010. Despite this, Korean culture permeates island life.

In 1903, Kea Shin Whang set off from Korea aboard the Gaelic , which was bound for the territory of Hawai‘i. Nearly half of his 102 shipmates were from the congregation of American Methodist minister Reverend George Heber Jones, who had persuaded members, many of them impoverished, to give up cruel life in Korea for the golden fields of opportunity that could be found on Hawai‘i’s plantations.

t that time the social conditions in orea were bad says ea hin s grandson Dr. Edmund Soo Myung Whang, a retired nephrologist who grew p in ahiaw . o

my grandfather immigrated with his whole family, just left with his four children and came to Hawai‘i to work on the sugarcane plantation in ah k .

For Kea Shin and the roughly 7,500 Korean migrants who arrived in the islands over the next two years, before Japan, then a protectorate over Korea, banned such migration, churches became community gathering places and networks of shared culture. Small home churches were started on plantations, while larger churches began cropping up in the cities. Sunday ser ices were an almost ni ersal feat re of plantation life for the oreans rth r . Gardner writes in The Koreans in Hawaii and the drift of non-Christian immigrants to these well-organized activities was so constant that through the years virtually all Koreans came to be identified with the hristian faith.