Hale

In the Hawaiian language, hale (pronounced huh’-leh) translates to “house” or “host.” Hale is an intimate expression of the aloha spirit found throughout the islands and a reflection of the hospitality of Ko Olina. In this publication, you will find that hale is more than a structure, it is a way of life. Ko Olina celebrates the community it is privileged to be a part of and welcomes you to immerse yourself in these stories of home.

FEATURES

56

Scenes at Sunset

As day wanes into night, a photographer is drawn to the horizon’s golden glow.

70 Legacy bound Day in and day out, a Kunia rancher honors his commitment to both the land and his family.

86

The Stone and the Self

After years working in a quarry, an artist finds his true path carved in stone.

98

Orchid ‘Ohana

A West Side orchid specialist brings an eclectic twist to the family business.

Kirk Fritz: The Endurance Athlete

Chelsey Jay: The Cultivator

LETTER FROM JEFFREY R. STONE

Aloha,

Authentic experiences are what travelers aspire to when they pack their bags and head out. As keen as one is to meet locals, see the sights on a curated hot list and recount visits through social media images, there is always an overlooked secret to every destination. When discovered, it will enrich the vision of every trip, simply with a little lens tweaking and an open mind. I’m going to tell you how to find the true essence of Hawai‘i.

Have you ever asked the magical question: What words mean the most in a native language?

Ask that question with sincerity and more than curiosity – with a giving heart. You will be rewarded with answers that will impact your life. A tiny word in Hawaiian that has informed my life is pono.

There is no equivalent word in English because it is so complex. Essentially, it means a state of balance and harmony and the translation is righteousness. It also means integrity, contentment, harmony, alignment, and values that favor the common good. Living Pono is an ancient Hawaiian value. It means that one seeks and finds balance and contentment in all these qualities of life and has harmony within themselves, others and the environment. It is our way of living in the rainbows of life.

This single word holds the power of how Hawaiians view and value their relationships with themselves, the land and the world -- and this belief is the state motto: Ua Mau ke Ea o ka ‘Aina I ka Pono. The life of the Land is perpetuated in righteousness.

Hawai’i is extraordinary and every day, every decision that my family and I make for Ko Olina is with Living Pono in mind. It is my hope that you enjoy our resort with Living Pono as your way of life in the islands – through how you see yourself and how you treat the local people who care for you. May it influence how you interact with your friends and family near and far. May you regard the islands and oceans that are a part of Ko Olina as precious.

I also hope you will take home this incredible respect, kindness and love of the world. Spread the word through your personal example, your social media and continue to live in this powerful consciousness of awareness – perpetuating it for seven generations into the future.

May you Live Pono forever and shine with the good to come from it.

My Aloha,

Jeffrey R. Stone Master Developer

Ko Olina Resort

Hale is a publication that celebrates O‘ahu’s leeward community—a place rich in diverse stories and home to Ko Olina.

“Ma ka hana ka ike” is a Hawaiian proverb that encourages us to learn by doing. In this issue, we take notes from community members on the West Side who, through familial ties or pulses of passion, gain knowledge through their engagement with land and sea, culture and community. Meet a stone sculptor whose spiritual connection to Hawaiian basalt guides his craft and a traveling classroom that connects kūpuna and keiki through the teachings of Native Hawaiian values. Hear from a waterman whose efforts at sea provides lessons of resilience, and a community leader whose farm offers all who visit soulful nourishment of the āina.

Here, our West Side neighbors learn by acting naturally and instinctively, honoring the traditions that came before them. We invite you, dear reader, to sit in on these miniature Master classes, and discover these lessons too.

ABOUT THE COVER

Orchids are among the largest and most diverse of the flowering plant families and are especially prized for their beauty. In this cover image taken by photographer John Hook, a spray of Phalaenopsis , known as moth orchids, dazzles in a display of exquisite color and form.

KoOlina.com

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa aulani.com

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina fourseasons.com/oahu

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club marriott.com

Beach Villas at Ko Olina beachvillasaoao.com

Ko Olina Golf Club koolinagolf.com

Ko Olina Marina koolinamarina.com

Ko Olina Station + Center koolinashops.com

The Resort Group theresortgroup.com

CEO & Publisher

Jason Cutinella

Partner & General Manager, Hawai‘i

Joe V. Bock

Editorial Director

Lauren McNally

Senior Editor

Rae Sojot

Senior Photographer

John Hook

Managing Designer

Taylor Niimoto

Designers

Eleazar Herradura

Coby Shimabukuro-Sanchez

Translators

Eri Toyama N. Ha‘alilio Solomon

Advertising

Senior Director, Sales

Alejandro Moxey

Head of Media Solutions & Activations

Francine Beppu

Advertising Director

Simone Perez

Director of Sales

Tacy Bedell

Account Executive

Rachel Lee

Media Sales Coordinator

Will Forni

Sales Inquiries sales@nmgnetwork.com

Operations

Operations Director

Sabrine Rivera

Operations Coordinator

Jessica Lunasco

Traffic Manager Sheri Salmon

Accounts Receivable

Gary Payne

Published by:

41 N. Hotel St. Honolulu, HI 96817

©2024 by NMG Network

Contents of Hale are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher. Hale is the exclusive publication of Ko Olina Resort. Visit KoOlina.com for information on accommodations, activities, and special events.

Image by John Hook

“Our motto is ‘my voice, my choice, my future,’ and if there’s anything you want to do as a high school principal, it’s empower students.”

Zachary Sheets, principal, Waipahu High School

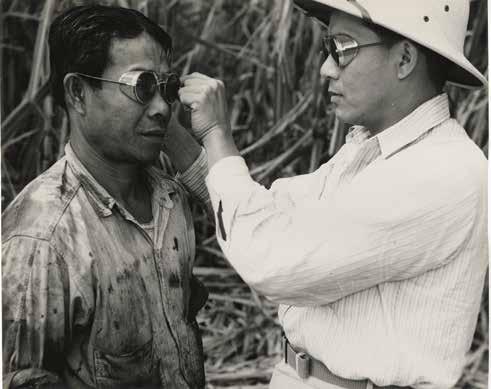

Image courtesy of Hawaii’s Plantation Village

Pinoy Pride

Text by Lindsey Vandal

Images by Kuhio Vellalos and courtesy of Hawaii’s Plantation Village

A student-led initiative to create the nation’s first public high school Filipino course comes to fruition.

Alaka‘i ‘ia e kekahi po‘e haumāna ka ho‘okumu ‘ia ‘ana o ka papa ‘ike Pilipino, ‘o ia ka papa mua loa o kēia ‘āina aupuni.

高校生たちが積極的に働きかけて生まれたフィリピン 文化の授業がはじまりました。公立高校としては全米初 の試みです。(ピノイとはフィリピンの人々が自分たちを 呼ぶ愛称)

Since their arrival in the 19th century, Filipino immigrants and their descendants have played an instrumental role here in Hawai‘i, both in driving the economy forward and threading the state’s cultural fabric. Though one in four residents bears Filipino roots, Filipino history and culture has been strikingly absent from classrooms in the state.

In 2020, a group of frustrated Filipino high school students turned a conversation into a crusade aimed at righting the oversight. Punahou High School sophomore Marisa Halagao recruited peers from public and private schools around O‘ahu to form the Filipino Curriculum Project. “I was feeling lost in my identity and wondering where the representation was in my Asian history class,” Halagao says. “We started this project so that no Filipino student has to ask that question, ‘Why don’t I feel seen?’”

19世紀にハワイに到着して以来、フィリピン移民とその子孫はハワ イ経済の発展に大きく寄与し、ハワイの多様な文化に彩りを加えて きた。だが、ハワイ住民の4人に1人がフィリピン系のルーツを持つ にもかかわらず、ハワイの学校教育の場でフィリピンの歴史や文化 が取り上げられることはほとんどなかった。

2020年、そのことに疑問を感じたフィリピン系の高校生数人が立 ち上がった。プナホウ高校の2年生(日本の高校1年生にあたる)の マリサ・ハラガオさんが、オアフ島の公立および私立高校の生徒に 呼びかけ、〈フィリピノ・カリキュラム・プロジェクト〉を発足させたの だ。「自分のアイデンティもよくわからなかったし、アジア史の授業 のどこが自分に関係しているのかもわかりませんでした」と、ハラガ オさん。「”なぜ自分の存在は見過ごされているんだろう?” わたし が感じたその思いをほかのフィリピン系の高校生が抱かずにすむ ように、このプロジェクトを立ち上げたんです」

After two years of campaigning and working with an educator design team to create a Filipino-based curriculum, the Filipino Curriculum Project team presented their framework to teachers and administrators at O‘ahu schools, including Waipahu High School, where roughly two-thirds of the 2,500 students are Filipino. “When I saw how invested they were and heard why it matters to them, there was no possibility of me saying no,” says Zachary Sheets, the school’s principal. “Our motto is ‘my voice, my choice, my future,’ and if there’s anything you want to do as a high school principal, it’s empower students.”

With widespread support from institutions, educators, and community members, CHR 2300, or Filipino History Culture, was approved in October 2023 by the Hawai‘i Department of Education—the first public school district in the nation to approve a Filipino studies course. Presented in six units, three times per week, Filipino

〈フィリピノ・カリキュラム・プロジェクト〉はその後2年にわたって 啓蒙活動を行ないながら、フィリピン文化を学ぶためのカリキュラ ムを教師たちと一緒に考案した。そして、その骨子をオアフ島のあ ちこちの学校で教師や学校理事たちに紹介した。そうした学校の ひとつが、全校生徒約2500人のうち3分の2がフィリンピン系の 生徒というワイパフ高校だ。「彼らの熱意を目のあたりにし、彼らに とってこのカリキュラムがなぜそんなに重要なのかを聞いたら、と てもノーとは言えませんでした」そう語るのは、ワイパフ高校の校 長ザッカリー・シーツ先生。「我が校のモットーは”わたしたちの声、 わたしたちの選択、わたしたちの未来”ですからね。高校の校長とし て、生徒たちの後押しができるなら喜んで協力します」

さまざまな機関、教師、そして一般の人々からの幅広い支持を得 て、2023年10月、フィリピン歴史文化コース”CHR 2300”はハワ イ教育庁に認可された。フィリピンについて学ぶコースが公立校の 授業として認められるのは全米でも初めてのことだ。6週間にわた って週3回行われる授業では、地域に根ざした市民活動を積極的 に行いながら、人権問題、逆境の克服や耐久力の育成、移民がフィ

Pinoy Pride

From 1906 to 1946, over 100,000 Filipino men were recruited by the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association to work on the islands’ sugar plantations. Today one in four Hawai‘i residents bears Filipino roots.

History Culture encourages community engagement and civic action, inviting students to consider topics such as human rights, resilience and sustainability, the effects of migration on Filipino identity, and solving current challenges.

Though the course is available statewide, only two O‘ahu high schools—Waipahu and Farrington—have signed on for the 2024 to 2025 school year. Halagao and Filipino Curriculum Project co-director Raymart Billote, both aspiring educators, are continuing to coach student collaborators throughout Hawai‘i on action steps they can take to help drive demand and improve the course’s reach.

During the first week of fall classes, Billote sat in on the inaugural session of Filipino History Culture taught at Waipahu High School, his alma mater. “When we shared our immigration stories as a kind of icebreaker, it was such an emotional, full-circle moment,” he reflects. “It’s so inspiring to see students take control of their education and want to learn about themselves and their roots.”

リピン人としてのアイデンティティにどんな影響を与えたといった トピックについて考え、さらには生徒が今、直面している問題の解 決法を探る。

ハワイ州のどこの学校でも取り入れられるカリキュラムとして認め られたが、2024年度にこのコースを実際に導入したのはオアフ島 のワイパフ高校とファーリントン高校の2校だけだった。教えること に情熱を燃やすハラガオさんと、〈フィリピノ・カリキュラム・プロジ ェクト〉のもうひとりのディレクター、レイマート・ビヨートさんは、よ り多くの高校生がこのカリキュラムを受けられるようにするために、 いったいどんな働きかけをしていけばいいのか、ハワイ各地でプロ ジェクトに協力する生徒たちにアドバイスを続けている。

秋の新学期の第一週目、ビヨートさんは、彼の母校でもあるワイパ フ高校で行なわれたフィリピン歴史文化の初めての授業に参加し た。「自己紹介も兼ね、生徒たちが自分の家族の移民物語を披露 したのですが、それはもう感動的で、それまでの努力が報われた気 がしました」ビヨートさんは振り返る。「自分や自分のルーツについ てもっと知りたい。そう考える高校生たちが、自分が受ける授業の 内容に自分たちの意見を反映させていく。その姿にとても勇気づ けられました」

Pinoy Pride

The announcement of a Filipino social studies course was a welcomed surprise for many students interested in themes of identity. Says Waipahu High School senior Jero Balason, “As an American-born Filipino, I am eager to explore my heritage further and am curious about the opportunities the course may provide for a deeper understanding of my roots.”

To learn more about the Filipino Curriculum Project, visit filipinocurriculumproject.com.

電撃的探求

Electric Explorations

Text by Kathleen Wong Images by Kuhio Vellalos

A decades-old power plant unexpectedly fuels a marine wonderland on the Wai‘anae Coast.

He mau anahulu makahiki ke kū ‘ana o kekahi hale ho‘īkehu ma Wai‘anae, ‘ano‘ai ho‘i kona hānai ‘ana a ulu he wahi home e noho ai nā ‘ano i‘a a mea ola o loko o ke kai.

数十年の昔からある古い発電所は、じつはワイアナ エ・コーストの海に広がるワンダーランドのエネルギ ー源となっています。

With my freediving fins and mask secured tightly in the bed of my Tacoma, I zip along the H-1 Freeway heading toward Wai‘anae. Once I pass Waipahu, the air feels noticeably hotter; the sun shines brighter. This is how I know I’m close to the West Side.

I spy the Kahe Power Plant welcoming me into Wai‘anae, its tall gray columns releasing steady streams of smoke into the air. The plant has long served as an informal marker for Kahe Point Beach Park, known to locals as the aptly named Electric Beach. Pulling off the highway, I pass over the area’s historical railroad tracks into the parking lot and slip into a stall.

愛車”タコマ”の荷台にフリーダイビング用のフィンとマスクをしっ かりくくりつけ、わたしはハイウェイH1を飛ばしてワイアナエに向 かう。ワイパフを越えると大気の温度ははっきりと上がり、太陽もま ぶしさを増す。ウエストサイドに近づいていると実感する瞬間だ。 カヘ発電所が目に入る。ワイアナエ・コーストへとわたしを歓迎し てくれているのだ。背の高い灰色の煙突から絶え間なく煙が空に 立ち昇る。ローカルの人々がごくあたりまえに”エレクトリック・ビー チ”と呼んできたカヘ・ポイント・ビーチ・パークの、昔からおなじみ

Electric Explorations

Despite the early hour, I can see people are already on the beach: scuba divers carrying hefty tanks, spearfishers prepping gear, families scoping out a spot to set up camp for the day.

I make my way across the sand. During the winter, heavy swells pound the northwestern coasts, requiring a carefully timed entry through the shore break. But today, the water is calm and inviting, its visibility crystal clear.

With a few swift strokes of my fins, I enter a flourishing underwater playground. Tropical fish of all kinds swim around me— iridescent uhu (parrotfish) and striped manini (convict tang), the lemon-hued lau‘ipala (yellow tang) and the occasional humuhumunukunukuāpua‘a—Hawai‘i’s state fish. An unexpected site for such activity, the Kahe Power Plant fuels the bustling ecosystem, pulling in sea water to

の目印だ。わたしはハイウェイをはずれ、列車が走っていた頃の名 残りの線路を渡り、駐車場の一角に車を停める。

朝まだ早いのに浜辺には人がいる。重いタンクを運ぶスキューバダ イバー。道具を準備するスピアフィッシャー。一日ビーチで過ごすつ もりの家族がテントを張るスポットを探している。

わたしは砂浜を横切った。冬のあいだは北西の浜辺には大波が押 し寄せるので、ショアブレイクを抜けるときは慎重にタイミングを見 計らわなければならない。だが今日は穏やかな海がクリスタルのよ うに澄みわたり、わたしを誘っている。

フィンをつけた脚で2、3回蹴り出すと、そこは華やかな水中の遊園 地だ。玉虫のように光の加減で色が変わるウフ(ブダイ)や縞々の マニーニ(シマハギ)、レモン色のラウイパラ(キイロハギ)、そしてと きにはハワイの州魚であるフムフムヌクヌクアープアア。さまざまな 熱帯魚がわたしを取り囲む。こんなところにこんな世界が広がって いるとは夢にも思わないだろうが、カヘ発電所はこの生き生きした

cool the plant then discharging it back into the ocean through its outflow pipes, the resulting warm water a congregating point for the area’s marine life.

Here, sea turtles drift about lazily, riding the current from the pipe. Some mornings, spinner dolphins dance and twirl their way up along the coast. I keep an eye out for a submerged stone buddha, who sits peacefully on top of a rock. The small statue is easy to miss, if not for the fish pecking at his thin layer of algae.

I hold my breath to dive down even deeper and slowly scale along the coral reef to see if I can spot a shy octopus. An inquisitive hīnālea (cleaner wrasse) trails closely behind me, watching everything I do. I break away to swim through some nearby rock arches, testing my ability to stay underwater. Like so many who swim at Electric Beach, I wish to stay in this vibrant marine world for as long as possible.

エコシステムにエネルギーを供給しているのだ。海水を引き入れて 施設を冷却したあと、パイプを通じて海に戻す。その水が温かいの で、周辺の海の生物が集まるスポットとなっているのだ。

パイプから出てくる温かい水の流れに身をまかせ、海ガメがぷかぷ か浮かんでいる。くるくると踊るようにジャンプしながら泳いでいく ハシナガイルカに出会える朝もある。水中の岩の上に安らかに鎮座 する石像を見逃さないように、しっかりと目を凝らす。仏像は小さく て、うっすらと仏像を覆う海藻をつつく魚たちがいなければうっか り見過ごしてしまいがちだ。

息を止めてさらに深く潜り、恥ずかしがり屋のタコがいないか珊瑚 礁をじっくり確認していく。好奇心の強いヒーナーレア(リュウグウ ベラ)がすぐ後ろをつけてきて、わたしの一挙手一投足を見守って いる。それを振り切るように近くの岩のアーチをくぐり抜け、自分が どれだけ長く潜っていられるかを試す。エレクトリック・ビーチで泳 ぐ多くの人と同じように、わたしも色鮮やかな海中の世界になるべ く長くとどまっていたいのだ。

The warm water discharged from the Kahe Power Plant’s submerged pipes attracts scores of tropical fish, making Electric Beach a snorkeler’s delight.

Visit Electric Beach’s marine wonderland by heading west along Farrington Highway. Turn left into Kahe Point Beach Park. Exercise caution before entering the water and speak to the lifeguard stationed there. If in doubt, don’t go out.

知恵を運ぶ車

Wisdom on Wheels

Text by Lindsey Vandal Images by Kuhio Vellalos

At Ko Olina, a traveling classroom connects keiki and kūpuna through lessons rooted in Native Hawaiian values.

Aia ma Ko ‘Olina, he lumi papa ne‘e hele ka mea e launa ai ‘o kamali‘i me kūpuna ma nā ha‘awina i pa‘a i nā pono Hawai‘i.

コ・オリナの移動幼稚園は、ハワイ独特の価値観に根 ざしたカリキュラムでケイキ(子供)とクープナ(祖父 母)の絆を深めています。

In April 2002, the Partners In Development Foundation hosted its very first session of the Tūtū and Me Traveling Preschool at Lili‘uokalani Protestant Church in Hale‘iwa on O‘ahu’s North Shore. Designed to support kūpuna (grandparents) who care for their mo‘opuna (grandchildren), Tūtū and Me’s novel concept delivered a free familychild interaction learning (FCIL) program right to the community and provided a culture-based alternative to expensive and inaccessible private preschools.

Today, Tūtū and Me makes twice-weekly visits to 24 learning sites in predominantly

2002年4月、〈発達を支えるパートナー財団〉はオアフ島ノースシ ョアのハレイヴァの町にあるリリウオカラニ・プロテスタント教会で 移動幼稚園〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉の記念すべき第1回目の授業を 行なった。モオプナ(孫)の世話をするクープナ(祖父母)支援のた めにつくられた〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉のコンセプトは画期的で、月 謝が高くて手が届かない私立の幼稚園の代わりに、家族が子供と 向き合いながら一緒に学習できる環境(FCIL)をハワイの文化にも とづいたプログラムとして無料で、しかも直接コミュニティに届けよ うというものだった。

Native Hawaiian communities on O‘ahu, Kaua‘i, Hawai‘i, Moloka‘i, and Maui. “The initial dream was to nurture the special relationship of kūpuna and keiki, and it’s blossomed to include parents, aunties, even daycare providers, all coming together to create a learning environment driven by Hawaiian culture and values,” says Amanda Ishigo, a former Tūtū and Me caregiver educator who serves as the program’s project director. “We’re empowering our caregivers to be the keiki’s first teacher, and they get to be right there learning alongside their little ones.”

Each Tuesday and Thursday, the preschool on wheels arrives at Lanikūhonua Cultural Institute at Ko Olina via the program’s Mercedes Sprinter van. Tūtū and Me caregiver educators open with the program’s signature song, “‘O Wai Ma Ke Kula?” (“Who Has Come to School Today?” before guiding children through explorations of music and movement, math, language, science, and creative arts all through the lens of Hawaiian values. Many of the program’s lessons are site-specific and

現在〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉はオアフ島、カウアイ島、ハワイ島、 モロカイ島、そしてマウイ島の、ネイティブハワイアンが多く暮らす 地域24ヶ所を週2回ずつ訪れている。「祖父母と孫たちの特別な 絆を育むのが狙いでしたが、そのうちに両親や親戚、やがては保 育園の先生まで加わって、ハワイの文化と価値観にもとづく学習 の場が生まれていったんです」ケアギバー(子供の面倒をみる人) 支援スタッフとしてスタートし、今では〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉のプ ロジェクト・ディレクターを務めるアマンダ・イシゴさんは振り返る。 「わたしたちは、ケアギバーが子供たちの最初の先生になれるよ うに支援しながら、ケアギバー自身も子供たちと一緒に学べる場を 提供しています」

毎週火曜日と木曜日、移動幼稚園〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉は専用 のメルセデス・ベンツ社の商用バン、”スプリンター”でコ・オリナ のラニクーホヌア文化会館にやってくる。〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉 のテーマソングともいうべき《オ・ワイ・マ・ケ・クラ?(今日は誰が 学校に来たかな?)》ではじまる授業では、子供たちは歌に続い て音楽や運動、数遊び、言葉遊び、科学、クリエイティブアートな ど、ハワイらしさにあふれたアクティビティにチャレンジしていく。

tailored to the unique history, landscape, and spirit of the area.

“Having opportunities to work alongside mahi‘ai (farmers) and harvest kalo (taro), fruits, and vegetables connected so many dots for my keiki when we explained farmto-table concepts,” says Naomi Kim-Davis, who attended Tūtū and Me sessions at the Lanikūhonua site with her son, Kala‘i. “It was so special to show him how we cultivate ‘āina (land), how it relates to his grandpa’s ‘āina, and the importance of water distribution.”

Not only has Tūtū and Me become a successful model for teaching fundamental skills and cultural knowledge to younger generations, the inclusive, modular preschool strengthens the keiki-caregiver kinship and provides a unique space for older generations to socialize. “I’ve seen tūtū (grandmothers) bonding over their mo‘opuna as they learn and play together,” Ishigo adds. “We’re connecting families who have the same kind of values, the same aloha for their keiki—this is really the essence of community.”

アクティビティの多くはそれぞれの会場の歴史や地理、気質を反映 してつくられている。

「マヒアイ(農家の人)と一緒にカロ(タロ芋)や果物、野菜を収穫 する機会を得て、子供たちもファーム・トゥ・テーブル(畑から食卓 へ作物を直接届ける)のコンセプトをすんなり理解できたようで す」ラニクーホヌア会場で息子のカライくんと〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミ ー〉のプログラムに参加するナオミ・キムデイビスさんは語る。「わ たしたちがアーイナ(大地)を耕す様子を見せることで、息子に彼 のおじいちゃんの土地や水の配分の大切さを伝えられるのがすば らしいです」

あらゆる人を受け入れる〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ミー〉は、子供たちの基 本的な生活スキルと文化的教養を育むプログラムとして成功して いるだけではない。ケアギバーとケイキの絆を深めると同時に、年 配の人同士のユニークな交流の場にもなっている。「モオプナたち と一緒に学び、遊ぶうちにトゥトゥ(祖母)同士の絆も深まっていく 様子を見てきました」イシゴさんはつけ加えた。「〈トゥトゥ・アンド・ ミー〉のプログラムは、似たような価値観を持ち、自分たちのケイキ に同じアロハ(愛情)を抱く家族同士をつないでいます。コミュニテ ィとはまさにそういうものではないでしょうか」

Guiding children from birth to age 5, the Tūtū and Me program offers children and caregivers an opportunity to explore subjects like music, science, creative arts, and language through the lens of Hawaiian values.

The Tūtū and Me program features site-specific curriculum tailored to the unique history, landscape, and spirit of each location. To learn more about the Tūtū and Me program, visit pidf.org.

WEST O‘AHU’S LARGEST SHOPPING CENTER ONLY MINUTES AWAY

FROM KO

OLINA!

100 Shops

30+ Restaurants & Eateries

Luxury Movie Theatres

Popular National Retailers

Local Boutiques

Cultural Events & Entertainment

Visit Ka Makana Ali’i on our FREE SHOPPING SHUTTLE! See a movie, get a mani-pedi, enjoy lunch, visit the arcade with the kids, shop for yourself, or discover one-of-a-kind gifts.

Ask your concierge about our FREE SHOPPING SHUTTLE and other transportation options between the shopping center and the resort.

GUARANTEE YOUR RIDE!

Scan the QR code below to make your reservation or search online: Free Shuttle Ka Makana Ali‘i

Image by John Hook

“

From the soft morning tones to vibrant afternoon hues and finally the rich, mysterious shades of twilight, the light on the West Side is just as dramatic as the landscape.”

Josiah Patterson, photographer

Image by John Hook

A T R E E S U

56

Scenes at Sunset

夕日の風景

As day wanes into night, a photographer is drawn to the horizon’s golden glow.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images by Josiah Patterson

A pō iho ke ao, ‘ume‘ume ‘ia ka maka o ka pa‘i ki‘i i ka nōweo mai a ka mōlehulehu.

昼が夜に変わっていく時間。金色に輝く水平線に魅せられた 写真家がいました。

Photographer Josiah Patterson is no stranger to sunsets. “In high school, we used to surf Mākaha Beach every day after school, and I remember wanting the sun to stay up just a little longer so I could surf more.” Yet as the sun tracked its path from sky to sea, eventually slipping below the horizon, any disappointment over the day’s end was sweetly tempered by the beauty that surrounded him: a glittering ocean, the Wai‘anae Mountain Range draped in gold.

In these snapshots of classic West Side sunsets, Patterson captures the gilded interlude between day and dusk—and the moments found within.

写真家ジョサイア・パターソンにとって夕日はとても 身近な存在だ。「高校時代、放課後は毎日マーカハで サーフィンをしていました。太陽がもうほんの少しでい いから沈まないでいてほしい。もっとサーフィンがした かったので、いつもそう願っていました」とはいっても、

太陽が軌道に沿って空から海へと落ちていき、やが て水平線の向こうに姿を消してしまえば、周囲の景 色の美しさに心を奪われ、一日が終わる切なさも忘 れていた。きらきら輝く海。金色の布をかけたような ワイアナエの山々……。

ウエストサイドならでは夕日のスナップショットのな かで、パターソンが捉えたのは昼と夕闇の合間の金色 に染まる景色と、そこに見つけた愛おしい瞬間だ。

Legacy Bound

彼が受け継いだもの

Day in and day out, a Kunia rancher honors his commitment to both the land and his family.

Text by Rae Sojot

Images by John Hook

I kēlā me kēia lā, hanohano i kekahi hānai pipi ma Kunia ka ‘āina a me kona ‘ohana.

来る日も来る日も、クニアの牧場主は牧場と家族を守るという 使命に真摯に取り組んでいます。

As the late afternoon sun slips behind the Wai‘anae Mountain Range, Sheldon Sojot hoists a bucket of alfalfa over the metal railing of a horse pen. He gives Baby, his mare, a quick pat before scanning the foothills for signs of the wild horses that sometimes appear at this dusky hour.

Days such as these are long for Sheldon, whose alarm rings at 4 a.m. five days a week, signaling the start of his shift as a foreman at a local plumbing company. Once he clocks out, he swaps his work attire for a pair of worn Wrangler jeans, a trucker hat, and steel-toe boots before jumping in his Chevy Silverado and heading west toward Kunia. There, hidden along the mountain’s edge is a small ranch—his second job and, in many ways, his second home.

Sheldon’s connection to the ranch began in the early ’90s. His father, Ivan, who preferred outdoor work to a conventional 9-to-5 job, would allow Sheldon to tag along to the “mountain” and help with small ranch tasks or go hunting. Sheldon, the eldest of Ivan’s three children, was the only one who showed a keen interest in ranch life.

His hānai grandfather, Uncle Rodney, had taught Ivan the ins and outs of ranching and bestowed the same knowledge and training onto Sheldon too. “He called me ‘young blood,’”

遅い午後の太陽がワイアナエ山脈の後ろに姿を消す 頃、シェルドン・ソホットさんはアルファルファのバケツ を厩舎の鉄柵の向こうに置いた。雌の愛馬”ベイビー” を軽くぽんぽんとたたいて山肌に目を凝らし、夕暮れ のこの時間にときどき姿を見せる野生の馬たちの気配 を確かめる。

こんなふうに終わるシェルドンさんの一日は長い。週5日、毎朝4時 にアラームが鳴る。地元の配管工事会社の現場監督としての仕事 のはじまりだ。配管工としての仕事が終わると、着古したラングラ ーのジーンズにトラッカーハット、スティールトゥのブーツに着替え てシェビーのシルバラードに飛び乗り、クニア方面に向かう。山裾 にひっそり隠れた小さな牧場は、シェルドンさんのもうひとつの職 場であり、いろいろな意味で彼のもうひとつの家だ。

シェルドンさんが牧場に行きはじめたのは’90年代初頭。父アイヴ ァンさんは9時から5時のありきたりの仕事よりも屋外での仕事を 好み、幼いシェルドンさんを”山”に連れていっては牧場の簡単な作 業を手伝わせたり、一緒に猟に出かけたりした。アイヴァンさんの 子供3人のうち、牧場に興味を示したのはいちばん年上のシェルド ンさんだけだった。牧場の仕事の一から十までをアイヴァンさんに 手ほどきしたのは、シェルドンさんにとってはハーナイ[非公式の養 子縁組 ハワイでは珍しくない]の祖父にあたるアンクル・ロドニー さん。ロドニーさんはシェルドンさんにも同じ知識と訓練を授けた。

Sheldon recalls of the early years spent shadowing his father and Uncle Rodney under the hot leeward sun. Over the next decade, Sheldon learned all things ranching: running cattle and riding horses, how to wield a branding iron and post-hole digger, the best tactics in dealing with customers and, on occasion, poachers too.

The tedium of dust and hard labor tarnished the initial shine of fun and adventure at the ranch. By the time he graduated high school, Sheldon was spending less and less time there, eventually becoming a full-time plumber and raising his own family.

「アンクル・ロドニーには”ヤング・ブラッド(ぼうず)”と呼ばれてい ました」リーワードの太陽が照りつけるなか、父アイヴァンさんと一 緒にアンクル・ロドニーのあとをついてまわったシェルドンさんの幼 い日の思い出だ。それから10年のあいだに、シェルドンさんは牛の 追い方、馬の乗り方、焼きごてのあて方、杭穴の掘り方、顧客とのや りとり、そしてときどき勝手に牧場に侵入する輩のあしらい方など、 牧場の仕事のすべてを身につけた。

いつも土埃まみれで目新しいこともなく、仕事も重労働。楽しく冒 険に満ちていた牧場の魅力もやがて色褪せていく。高校を卒業す る頃のシェルドンさんは、牧場を訪れることもほとんどなく、やが て排水管工としてフルタイムで働きはじめ、家庭を持ち、家族を

When Uncle Rodney died, Ivan took charge of the ranch alone, and Sheldon’s visits remained infrequent—usually only when his father needed help.

Then, in the summer of 2020, Ivan passed. As the family grieved their patriarch, the question of caretaking the ranch arose: would Sheldon, like his father before him, answer the mountain’s call? The impending mantle loomed heavy. While the romantic notion of ranch life appeals to outsiders, Sheldon knew the reality was far less glamorous and far more gritty. Ranch life is a hard life, and unlikely to bring any financial gain. “No one does this for the money,” he says.

During his father’s life, friends and relatives of the family would often ask, “Where’s Ivan?” The answer was

支えた。アンクル・ロドニーが亡くなり、牧場の経営はアイヴァンさ んがひとりで引き継いだが、相変わらずシェルドンさんが牧場を 訪れるのは、アイヴァンさんにたまに手伝いを頼まれたときくらい だった。

ところが2020年夏、アイヴァンさんが他界する。一族は家長を失 った悲しみに暮れたが、やがて牧場は誰が世話するのかという話 になった。アイヴァンがそうしたように、シェルドンも山が呼ぶ声に

always the same—on the mountain. The implication was clear: Ranch life requires commitment, sacrifice, and long hours away from loved ones. There were late-night phone calls from neighbors reporting loose cattle or a broken waterline needing immediate repair, along with so many missed birthday parties and family gatherings, all because the mountain called.

Despite his initial reservations and the ongoing stress of managing the ranch, Sheldon has embraced his decision to honor his father’s legacy. On O‘ahu, the number of ranches has declined in the last 100 years as more agricultural land succumbs to urban sprawl and gentrification. “I’m lucky, not many people get to experience this,” Sheldon says, gesturing to the ranch’s vast swaths of land clear of any buildings and highways. “If you stand on the ridge, you can see all the way down to Diamond Head.”

When asked about Ivan, Sheldon’s eyes glisten, and he clears his throat. Like his father, he is a man of few words, and it’s hard for him to express the gravity of his father’s absence. Instead, he offers small details—how much his father loved waiting for the wild horses to come down from the mountain each evening, his joy in seeing a new calf appear in the herd,

応えるのだろうか。シェルドンさんの前に重い責任が差し迫ってい た。傍から見ればロマンにあふれて魅力的に見えるが、現実の牧場 は華やかさのかけらもなく、むしろ荒涼としている。苦労ばかりで経 済的にも採算が合わない。「お金のために牧場を経営している人な どいませんよ」シェルドンさんは言った。

アイヴァンさんの存命中、友人や親戚によく尋ねられたものだ。”ア イヴァンはどこだ?” 答えはいつも同じ。山だ。つまり、牧場で生き るには献身と自己犠牲が要求されるということだ。愛する人々と過 ごす時間も短い。夜更けに牧場の近所の人から電話がかかってき て、逃げた牛がうろうろしているとか、水道管が壊れているからすぐ に修理してくれと呼び出されることもあるし、誕生会や親戚の集ま りにもめったに出られない。すべては”山”のお呼びのせいなのだ。

当初のためらいや、すでに肩にのしかかっていた牧場経営のスト レスにもかかわらず、シェルドンさんは結局、父が遺した伝統を受 け継ぐと決めた。オアフ島では過去100年のあいだに牧場の数 がだいぶ減った。かつては農地だった土地の多くは広がる都会や 再開発の波にのまれている。「自分は幸運だと思いますよ。これが見 られる人はあまりいないから」シェルダンさんは腕を広げ、建物も 道路もなく、ただ牧草が生い茂る広大な牧場を示した。「山の尾根 からはダイアモンドヘッドまで見渡せるんですよ」 アイヴァンさんのことを尋ねると、シェルドンさんは目を潤ませて咳 払いをした。父親譲りで無口なだけに、その父を失ってできた心の

the rare instances he would indulge in some fun on the ranch and fly kites, his exceptionally close bond with his grandson Ikaika, Sheldon’s son, whom he would bring to the ranch regularly.

Day in and day out, Sheldon tackles the ranch’s perpetual to-do list. He checks the water tank and feeds the animals, fixes dirt roads after heavy rains. Some days bring excitement with cattle branding and butchering, while other days are dedicated to repairing fence lines. The cattle graze across the valleys and flatlands, at times oblivious to the barbed wire meant to contain them. They prod and nudge against the fence line until something breaks, creating an opening for others to escape. Sheldon must first wrangle the errant cows and then locate the area needing repair. With nearly 500 acres to canvas, it’s a tall order, with much of it done in solitude and on horseback. It’s quiet moments like these that affirm his choice to continue his father’s legacy, when he recognizes the ranch as not just a responsibility but a refuge—a space for one’s spirit to breathe deeply and feel free. “It’s just peaceful,” Sheldon says. “I could never get lost on the mountain.”

穴の大きさをうまく言葉にできないのかもしれない。そのかわり、 ぽつりぽつりと小さな思い出を語ってくれた。夜ごとに野生の馬た ちが山から下りてくるのをアイヴァンさんがどれだけ楽しみにして いたか。群れに新しい仔馬を見つけてうれしそうだったこと。珍しく 無邪気に牧場で凧を上げることもあった。シェルドンさんの息子イ カイカくんのことは特に可愛がっていて、しょっちゅう牧場に連れ てきたこと……。

毎日毎日、シェルドンさんは変わりばえのしない牧場の仕事と格 闘する。水のタンクをチェックして動物たちに餌をやり、大雨の後 は泥道を整備する。牛に焼きごてをあてる日や牛をさばく日は刺激 的だが、フェンスの修理を黙々と続ける日もある。谷や平地を移動 して草を食む牛たちは、ときに有刺鉄線のフェンスが自分たちを囲 うためにあることを忘れてしまう。そしてフェンスをぐいぐい押すう ちに何かがはずれてできたすき間から脱走してしまうのだ。そんな ときはまず迷子の牛たちを連れ戻し、次にフェンスの修理が必要 な場所を突き止めないといけない。馬にまたがり、500エーカー近 い広さ(東京ドーム約43個分)の敷地を囲むフェンスをたいてい ひとりで確認していく。とてつもなく地道な作業だ。だが、そんな静 かなひとときにこそ、父から受け継いだ伝統を守るという決断は正 しかったと思えるそうだ。牧場はただの重荷でなく、心の避難所で もある。魂が深呼吸できるところ、自由を感じるところなのだ。「心 が落ち着くんです」シェルドンさんは言う。「山では迷うこともあり ませんからね」

Dusk spreads over the lowlands, adding a blurred softness to the pitch and yaw of the terrain. On the upper slopes, the forest appears as a dark green smudge. The land soon quiets into the long stillness of night. Some 12 miles away, Sheldon lies in bed, setting his alarm for another early start. As sleep approaches, his thoughts drift to the ranch, to the mountain. To his father too. Under a black velvet sky, the cattle have finished drinking from the water trough, settling themselves amid the haole koa and California grass. They low softly. Higher up, unseen, the wild horses nicker among the ‘ōhi‘a lehua and naio. The cool air rises, and all feels right.

低地には夕闇が広がり、地形の凹凸もやわらかくぼやけていく。斜

面の上には森が広がり、点々と濃い緑色が散る。まもなく長い夜が 静かにあたりを包む。20キロほど離れた自宅で、シェルドンさんは ベッドに入り、また早くはじまる明日のためにアラームをセットす る。眠りに落ちながら、彼の思いは牧場や山へと飛んでいく。父アイ ヴァンさんも頭に浮かぶ。漆黒の夜空の下、水おけの水を飲んだ牛 たちは、ハオレコアの木とカリフォルニアグラスのなかにそっと膝を つく。姿は見えないが、山にはオーヒアレフアとナイオの木々に囲ま れた野生の馬たちのいななきが響く。ひんやりした空気が立ちのぼ り、夜は満たされた気分に包まれる。

The Stone and the Self

石と自分を見つめて

After years working in a quarry, an artist finds his true path carved in stone.

Text by Kathleen Wong

Images by Chris Rohrer

A hala nā makahiki he nui iā ia e hana ana ma ka lua ‘eli pōhaku, aia ka pono o kēia mea kālai ma ka pōhaku kālai.

採石場で長年働いた後、自分が本来歩むべき道は石に刻まれ ていたことに気づいたアーティストがいました。

The Stone and the Self

Nestled on a quiet road in Wai‘anae Valley stands a 20-foot-tall structure outfitted with the stuff of a craftsman’s dream: forklifts, cranes, sanders, and grinders; stands equipped with metal clamps, swivels, and U-joints; worktables and red metal tool chests.

Amid the tools and machinery, unexpected items populate the scene: a trio of large boulders, a stone bowl with a white coral inlay, a sculpture artfully hand-carved in the shape of a mango— the artistic works of Don Matsumura, a Wai‘anae-born-and-raised stone sculptor with a deep connection to Hawaiian basalt, Hawai‘i’s rock formed from volcanic lava flow.

Matsumura, who spent over 23 years quarrying rock for Hawaiian Cement, never imagined he would end up as a full-time artist. Applying to the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in the ’80s, Matsumura initially considered studying animal husbandry, since he worked at a dairy, and business, like his dad wanted. But once the campus’ art building caught his eye, he signed up for sculpture classes. “Art was one of the first things I felt really comfortable with—that I couldn’t do anything wrong,” Matsumura says. “All I had to do was just make whatever I wanted to.”

ワイアナエ・ヴァレーの静かな道に、職人なら誰もが大 喜びしそうな機材をずらりとそろえた高さ6メートルほ どの建物がある。フォークリフト、クレーン、研磨機、そ して研削機。クランプ、スイベルラチェット、自在継手な どが並ぶ道具棚。作業台。赤い鉄製の工具ワゴン。

工具や機材に混ざって意外なアイテムも顔をのぞかせ ている。大きな岩が三つ。内側に白い珊瑚を貼った石 のボウル。芸術的な手彫りのマンゴー。ワイアナエで生 まれ育った彫刻家ドン・マツムラさんの作品群だ。もと は火山から流れ出る溶岩だったハワイの玄武岩とマツ ムラさんの関わりは深い。

23年にわたってハワイアン・セメント社の採石現場で 働いたマツムラさんは、自分がフルタイムのアーティス トなるとは夢にも思っていなかった。’80年代、ハワイ 大学マーノア校に出願するとき、酪農場で働いた経験 があったことから当初は畜産か、父親の勧める経営を 専攻するつもりでいたそうだ。ところがキャンパスで芸 術学部の建物に目を奪われた彼は彫刻科に進学する。

「初めて自信を持って取り組めたものが芸術でした。

何を作っても失敗はありませんでした」マツムラさんは 当時を振り返る。「作りたいと思うものを作れば、それ でよかったんです」

Despite graduating with a fine arts degree, Matsumura settled into a reliable, nine-to-five job in the mining industry.

At Hawaiian Cement’s large quarry in Halawa Valley, known for its rich basalt deposits, he drilled and blasted boulders that were then hammered into finer pieces for cement production. It was a good living, Matsumura concedes—his strong work ethic allowed him to rise through the company ranks to the role of general manager—yet he remembers often yearning for some other, yetunknown form of fulfillment. “I just knew that I wasn’t where I was supposed to be,” he recalls. “There was always something missing.”

In 2013, Matsumura retired to take care of his father, who had been diagnosed with dementia, and found moments to rekindle his creative side by making jewelry and carving small bowls of stone. Then, as he noticed that large, industrial equipment were becoming increasingly available to everyday craftsmen like himself, Matsumura toyed with the idea of sculpting largescale stoneworks. “All my life, I’ve been around big equipment with big tires, big buckets, and stuff like that,” he says. “That’s the environment that I like.” In 2022, he took a leap of faith. He built out a 40 x 100-foot shop space, adding the heavy equipment needed to achieve the projects he envisioned:

芸術学部の学位をとって大学を卒業したものの、マツ ムラさんは採石会社での、9時から5時の安定した仕 事を選んだ。豊かな玄武岩の鉱床に恵まれたハラヴ ァ・ヴァレーにあるハワイアン・セメント社。その大規 模な採石場で、マツムラさん掘り出して爆破した岩を さらに打ち砕き、セメントをつくる作業に従事した。け っして悪くない暮らしだった。マツムラさんもそう認め る。だが、持ち前の勤勉さを買われて昇進を続け、所長 にまでなりながら、いつも何か物足りなさを感じてい たそうだ。何かはわからないが、やらなければいけない ことがあるような気分。「自分がいるべき場所がそこで はないのはわかっていました。いつも何かが欠けてい たんです」

2013年、マツムラさんは認知症の診断を受けた父親 の介護のために退職する。時間に余裕ができてふたた びクリエイティブな作業に目覚めたマツムラさんは、ア クセサリーをつくったり、小さな石のボウルを削ったり した。ふと気づけば、業務用の大型機材が昔に比べて ずっと身近なものになり、自分のような趣味の工芸家 にも手が届くようになっている。石を素材にして大がか りな作品に取り組んでみようか。マツムラさんはそんな 考えを抱きはじめた。「長年、大型の重機やタイヤ、大き なバケツなどに囲まれていましたから、そういう環境に

a crane found on Craigslist that could transport boulders, a heavy-duty drill press capable of making holes 24 inches wide, a Kubota mini excavator. Matsumura’s affinity for Hawaiian basalt is rooted in the stone’s aesthetic and endurance. “The stone stays around for a long time and eventually, over thousands of years, it breaks down from the wind,” he says. There is also the cultural connection through his Native Hawaiian heritage. In Hawaiian culture, stones, or pōhaku, are revered as sacred and utilized for various purposes, from everyday tasks like pounding kalo (taro) to masonry and

The Stone and the Self いると落ち着きました」2022年、マツムラさんは思い きって賭けに出る。横に約12メートル、縦に約30メー トルの作業場をつくり、心に思い描くプロジェクトの製 作に必要な重機をそろえはじめた。大きな岩を移動す るクレーンや直径約60センチの穴があけられる業務 用ドリル、クボタ社のミニ掘削機などは、個人売買情 報などで米国で人気のウェブサイト〈クレイグリスト〉 で見つけた。

マツムラさんは、その美しさと耐久性ゆえにハワイ産の 玄武岩を好む。「長い歳月を持ちこたえ、何千年ものあ いだ風に砕かれて石になったのです」ネイティブハワイ アンの血を受け継ぐマツムラさんは文化的なつながり も感じるという。ハワイ語で石はポーハクと呼ばれ、

crafting ki‘i (symbolic representations of deities). For Matsumura, Hawaiian basalt will always hold tremendous mana (power): “Looking back on my life, the images I kept and can still see so vividly are of stone–walking on dark, black boulders following a stream, the beach and mountains of Mākua Valley, huge rock walls dry laid without mortar.”

Today, stone sculpting remains an intentional, laborious affair for Matsumura—even a simple bowl can take months to complete—yet he never rushes the process, instead preferring to take his time observing the stone, walking around it, and touching it as he

神聖なものだった。日常ではカロ[タロ芋]を叩いたり、

キイ[神々の像]をつくったり、さまざまな用途に使われ てきた。マツムラさんは、昔からハワイ産の玄武岩の途 方もないマナ[パワー]を感じていたそうだ。「振り返れ ば、小川に沿って黒々とした岩の上を歩いた記憶や、 大きな岩壁がそびえたつマークアの谷の浜辺や山々な ど、昔から心に残り、今もまぶたにくっきりと浮かぶも のは石ばかりです」

マツムラさんにとって、今でも石を彫るのは面倒で気 力のいる作業だ。簡単なボウルひとつとっても完成ま でに数ヶ月を要する。だが、マツムラさんには急いで

The Stone and the Self

The Stone and the Self

crafts it into a sculpture. Sometimes he will move a stone around or stand it up to gain a new perspective and, hopefully, some answers. “I’m talking to it, you know? ‘Where do you come from? What do you want to be?’” The environment matters too: “Everything has to be really quiet, peaceful,” he explains. From there, Matsumura simply listens for directions and allows the stones to guide him.

Most mornings, Matsumura heads to the shop—just a few steps from the house he shares with wife, Sandra—where he then moves between various projects to keep his creative energies flowing. Sometimes he plays with negative space, removing perfectly disc-shaped sections of rock from a raw, irregular boulder. Other times, he’ll pick up a Dremel to fine-tune a stone sculpture’s intricate details.

Matsumura shares that while his journey from working in a rock quarry to becoming a stone sculptor now makes sense to him, he initially struggled with insecurities related to choosing the artist path. He has since embraced the belief that he’s exactly where he is meant to be, making a point to reflect on any hang-ups the same way he contemplates the stone forms in front of him. “That process clears the way for me to look at the stone and be able to receive something that says, ‘OK, this is what you can do.’”

仕上げる気はない。むしろじっくり時間をかけて石を 観察し、そのまわりを歩き、手で触れながら制作を進 めていく。ときには石を動かしたり、起こして別の角度 から眺めてみたりして答えを探す。「石に話しかけるん です。どこから来たんだ、何になりたいんだってね」そ んなときはまわりの環境も大切だ。「静けさと穏やかさ に満ちていないとだめですね」そうして石に問いかけ たあとは、ひたすら石の声に耳を傾け、導かれるままに 彫っていく。

ほぼ毎朝、マツムラさんは妻サンドラさんと暮らす家屋 からほんの数歩離れた作業場に向かう。そして、クリエ イティブなエネルギーの流れが途切れないように、い くつもあるプロジェクトからプロジェクトへと移動しな がら手を加えていく。ときには空白で遊んでみる。削り 出したままの不恰好な岩から完全な円盤型を切り出し てみたり、ドレメル社の研磨ドリルを握り、作品の細か い部分に手を加えたりもする。

採石場に長年勤めた後、こうして石を扱う彫刻家にな った運命がようやく腑に落ちたというマツムラさん。ア ーティストとして生きる道を選んだ当初はこれでよかっ たのかと悩んだそうだ。今では、ここが自分のいるべき 場所だという信念を持ち、不安に陥ったときは、石と向 き合うように不安と向き合う。「このプロセスのおかげ で雑念のない心で石と向き合えるようになる。”それな ら、こうしたらいいじゃないか”という石からの答えもキ ャッチできるようになるんです」

honolulumuseum.org

Orchid ‘Ohana

蘭の一族

A West Side orchid specialist brings an eclectic twist to the family business.

Text by Lindsey Vandal

Images by John Hook

Lawe ‘ia he ‘ike ma‘alea e kekahi mea ‘ike loa i ka ho‘oulu ‘okika ma ka ‘ao‘ao Komohana ma kekahi pā‘oihana na ka ‘ohana.

家族経営のビジネスにちょっと個性的なひねりを加えたウエ ストサイドの蘭農家をご紹介します。

Early each morning, Jeremy Domingo heads west along back country roads before entering a large agricultural lot located halfway between the Pacific Ocean and the Wai‘anae Mountains. There, inside a nearly football fieldsized greenhouse, orchids of countless colors and configurations await his careful tending.

S&W Orchids’ two-acre nursery—started by Jeremy’s parents, Carmela and Stan Watanabe—grows an impressive amount of orchid flowers, as well as other curious plants, for retail markets and orchid enthusiasts on O‘ahu and beyond. The family-run business has deep roots.

ジェレミー・ドミンゴさんは毎日早朝から田舎道を西 に向かって、ワイアナエの山々と太平洋のちょうど中 間に位置する広い農地にやってくる。アメリカンフット ボールのフィールドほどもある大きなビニールハウス のなかでは、あらゆる色やかたちの蘭の花たちがジェ レミーさんに愛情をこめて世話してもらうのを待って いる。

ジェレミーさんの両親、カーメラとスタン・ワタナベさ んがはじめた2エーカー(約2,500坪)の種苗園〈エ ス・アンド・ダブリュー・オーキッズ〉は、園芸店への卸 売りとオアフ島内外の愛好家のために、驚くほどたくさ んの蘭だけでなく、さまざまな珍しい植物を育ててい る。家族経営の農園の歴史は深い。

Orchid ‘Ohana

“My parents experimented with propagating orchids in bottles at our home in Waipahu,” says Jeremy, of the nursery’s origin in 1990. “It’s a whole process—from germinating orchid seeds in flasks in a sterile environment to planting them a year later—and I think they really enjoyed the challenge.”

Jumping into a new trade was risky, but the Watanabes weren’t exactly starting from scratch. Carmela’s father, Yasuji Takasaki, was an orchid wizard of sorts, renowned for his Hawai‘i Island farm, Carmela Orchids, started in 1960 on four acres at Hakalau Village in the Umauma district. A former cultivation supervisor at Hakalau Sugar Plantation, Takasaki and his wife, Mitsuko, raised Vanda Miss Joaquim orchids, prized for their stunning, speckled petals in shades of lavender—at one point harvesting 35,000 orchid blossoms a day to supply local lei makers. Gradually, the Takasakis transitioned to potted orchids with guidance from their two sons, Sheldon and Gerrit, who applied their knowledge from earning degrees in horticulture to breed and clone orchid plants in service of largescale production.

After high school, Jeremy helped his parents build out the S&W Orchids nursery in stages. He joined the business

「両親はワイパフの自宅で瓶のなかで蘭を増やす実験 をしていました」ジェレミーさんは1990年の農園の原 点を振り返る。「無菌の環境でフラスコのなかの蘭の種 を発芽させ、一年後に植えつけるまで、両親はすべての 工程を手がけていました。むずかしいからこそ意欲を 燃やしたんだと思いますよ」

未知の業界にいきなり飛び込むのは危険な賭けだが、 ワタナベ夫妻はずぶの素人というわけでもなかった。 カーメラさんの父、ヤスジ・タカサキさんは蘭の名人と して知られた人物。1960年、ハワイ島ウマウマ地区の ハカラウ村で、敷地4エーカー(約5,000坪)の種苗園 〈カーメラ・オーキッズ〉を起こした。もとは〈ハカラウ 砂糖農園〉の栽培の管理をしていたタカサキさんとそ の妻ミツコさんは、斑点の入った鮮やかなラベンダー 系の花弁が珍重されるヴァンダ・ミス・ジョアキムとい う蘭を育てる一方、ハワイのレイ・メーカーのために 一日35,000個の花を収穫していた時期もあったそう だ。二人の息子シェルドンさんとジェリットさんの勧め で、タカサキ夫妻は次第に主力商品を鉢植えの蘭に移 行していく。一方、シェルドンさんとジェリットさんは大 学で専攻した園芸学の知識を生かし、大規模な農園 における交配やクローン栽培に取り組んだ。

高校卒業後のジェレミーさんは、両親がはじめた〈エ ス・アンド・ダブリュー・オーキッズ〉をところどころで 手伝ってきた。21歳で本腰を入れて家業に取り組む ようになり、その年の大半は蘭の見本市をまわって

Orchid ‘Ohana

full time at age 21 and spent much of the year traveling to orchid trade shows. In the early days, the nursery’s key sales came from exporting orchids to the continental U.S. and Puerto Rico, with fringe income from selling to small shops around O‘ahu, such as Wally’s Garden Center and Longs Drugs.

As competition from overseas orchid superfarms forced many growers out of the market, S&W Orchids endured by adapting, with Jeremy driving day-today operations and Stan and Carmela serving as president and vice president, respectively. Today, the business relies on strong retail partnerships with highvolume, on-island retailers, including Costco, Walmart, and Home Depot.

“After surviving 9/11, we decided to focus more on the local market,” Jeremy says. “I must have approached the big guys at the right time, because we got in. We’ve been very blessed to keep these relationships going.”

Today, the ever-popular phalaenopsis orchid, with its broad palette of bold colors and lengthy blooming periods, is S&W Orchids’ bread and butter.

Jeremy also maintains a multifarious selection of dendrobium, oncidium, vanda, cattleya, and other genus types, often forging new hybrids in hopes of producing extraordinary montages of

過ごした。創業当時の売り上げの大半は米国本土とプ エルトリコへの蘭の輸出によるもので、ウォリーズ・ガ ーデン・センターやロングス・ドラッグなどオアフ島に 点在する小型店舗への卸売りの売り上げは微々たる ものだった。

外国のスーパーファームとの競争に敗れ、多くの蘭農 家が姿を消していくなか、〈エス・アンド・ダブリュー・オ ーキッズ〉はスタンさんとカーメラさんがそれぞれ社長 と副社長となり、ジェレミーさんが日常業務を切り盛 りしながら、状況にうまく順応して生き延びてきた。今 日ではコストコやウォルマート、ホーム・デポといった オアフ島内の大型店舗と強固な関係を結び、大口の卸 売りでビジネスを支えている。「アメリカ同時多発テロ 事件を乗り切ったあと、うちはローカル市場を中心に やっていこうと決めたんです」ジェレミーさんは振り返 る。「大型店舗にうまく食い込めたのはタイミングがよ かったんでしょうね。こうして取引が続いているのはあ りがたいことですよ」

〈エス・アンド・ダブリュー・オーキッズ〉の現在の主力 商品は、さまざまな花の色と開花期間の長さでますま す人気の胡蝶蘭だ。ジェレミーさんはほかにもデンド ロビウム、オンシジューム、ヴァンダ、カトレヤなど、さま ざまな属種の多種多様な品種を栽培しながら、よそで は見られない色やかたち、サイズの品種を生み出そう と新たな交配を続けている。外側にある3枚の萼片(が くへん、セパル)が内側の3枚の花弁を取り囲む花の構 造はすべての蘭に共通しているが、多様性に富む蘭の

color, shape, and size. Though all orchids share the same floral structure of three outer sepals encircling three inner petals, wildly diverse species within the Orchidaceae family possess highly coveted traits—for instance, the bubblegum fragrance of the Encyclia radiata, the cascading orange blossoms of the Cattleya labiata (aka “Big Lip”), and the fuschia and banana-speckled flowers of the Blc. Waianae Leopard hybrid.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Jeremy started collecting harderto-come-by niche plants, combing local nurseries and importing from faraway growers—both as a matter of curiosity

なかでもとくに人気の品種もある。バブルガムの匂い のするエンサイクリア・ラディアタやオレンジの花が滝 のように連なるカトレヤ・ラビアタ(通称ビッグリップ)、 紫紅色とバナナ色の斑点が浮かぶブラッソレリオカト レヤ・ワイアナエ・レオパードなどがそれだ。

2020年にコロナ禍がはじまったとき、ジェレミーさん は自身の好奇心だけではなく顧客からのリクエストの 増加もあって、近くの種苗園をくまなく探したり、遠く の農家から取り寄せたりして、なかなか手に入らない 植物を集めるようになった。今ではモンステラやティラ ンドシア(エアプランツ)、アロエ、ガステリア(アロエに

Orchid ‘Ohana

Discover

Orchid ‘Ohana and to satisfy the rising number of customer requests. His cadre of curious plants includes a remarkable array of monstera, tillandsia (air plants), and succulents such as aloe, gasteria (aloelike with long, pointy leaves), haworthia (small succulents), and echeveria (rosette shaped).

Among the abundance of captivating orchid images on S&W Orchids’ Facebook, YouTube, and Instagram accounts, Jeremy’s quirky and often humorous posts showcase his favorite unusual finds, such as a gigantic, 50-year-old Dendrochilum magnum (Orchid Dynasty), and an extremely rare, variegated Philodendron Golden Dragon with split-colored, dragonshaped leaves.

Carmela Orchids is still going strong in Hakalau, with Jeremy’s Uncle Sheldon at the helm, while Uncle Gerrit runs Hawai‘i Hybrids, another orchid nursery in Hilo. Though his passion for plants continues to grow alongside his long hours spent every day at the nursery, Jeremy is careful not to overdo it: Other than a small succulent display in a rocky patch at the end of the driveway, the exterior of his Waipahu home is strictly cement and gravel. “I never take my work home with me,” he says with wry charm. “At the end of the day, the last thing I want to do is work in the yard.”

似た植物で、長く尖った葉を持つ)、ハオルチア(小さ な多肉植物)、エケヴェリア(ロゼット型の多肉植物)な ど、驚くほど多様な珍しい草花を扱っている。

フェイスブックやユーチューブ、インスタグラムの 〈エス・アンド・ダブリュー・オーキッズ〉のページに は、魅惑的な蘭のイメージが数多く並ぶ。ジェレミーさ んは、独特のユーモアに富んだ口調で50年も前からあ るという巨大なデンドロキラム・マグナム(オーキッド・ ダイナスティ)や龍のかたちの葉が二色に分かれてい るフィロデンドロン・ゴールデン・ドラゴンなど、超がつ くほど珍しいお気に入りの草花を紹介している。

ジェレミーさんの叔父シェルドンさんが率いる〈カーメ ラ・オーキッズ〉は今もハカラウ村で順調に経営を続け ている。もうひとりの叔父ジェリットさんもヒロで別の 蘭農園〈ハワイ・ハイブリッズ〉を経営中だ。農園では毎 日長時間、植物に情熱を傾けるジェレミーさんだが、 熱中し過ぎないように気をつけていて、ワイパフの自宅 の庭は石の上にいくつかの多肉植物が並ぶほかはセ メントと砂利しか目に入らない。「仕事は家に持ち込ま ないようにしているんです」ジェレミーさんはにやりと 笑った。「なんだかんだ言っても、ぼくは庭仕事が嫌い なんですよ」

Image by Kuhio Vellalos

“My vision right now is continuity. You move at the speed of trust, right? You move at the speed of community.”

Chelsey Jay, executive director, Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha

Image by John Hook

Kirk Fritz: The Endurance Athlete

As told to Lindsey Vandal Images by John Hook

Nui nā eo i ka‘a iā Kirk Fritz, ka mea e ‘ike maopopo ‘ia ai, ‘o ka mana‘o ho‘opono ‘ana ka mea e wehe ai kēlā me kēia ālaina.

数十年にわたってスポーツ選手として活躍してきたカーク・フリッ ツさんは、揺るぎないポジティブ思考があればどんな難関も乗り 越えられることを証明してきました。

Growing up in Southern California, I was always skateboarding distance from the beach—body surfing, boogie boarding, and surfing became the backbone for everything else. I started competitive swimming at 5 years old, and at 9 years old I was racing BMX bikes and playing junior all-American football.

My football coach, Coach Johnson, had these crystal-blue eyes. He was not a very tall guy, but when he looked at you with fire in his eyes, there was this discipline factor. I knew I had that intensity inside of me and I could bring it out through sports.

In 1989, I moved to Hawai‘i and became a City and County of Honolulu lifeguard for District 1, Waikīkī and Ala Moana. Some friends invited me to join a sprint distance

南カルフォルニア出身のわたしは、いつもビーチにはスケートボー ドで行ける距離に住んでいました。ボディサーフィン、ブギーボー ド、サーフィンはすべての基本になりましたね。競泳をはじめたのは 5歳。9歳でBMXのレースに出場し、ジュニアの全米フットボールチ ームでもプレイしていました。

フットボールのジョンソン・コーチの目は、クリスタルのように澄ん だ青でね。小柄な人でしたが、炎のように燃える瞳で見つめられる とこっちは背筋が伸びました。自分にもコーチと同じ強さがあって、 それはスポーツを通じて発揮できるとわかっていました。

1989年にハワイに移り、ワイキキやアラモアナ一帯を含む第1地 区を担当するホノルル市のライフガードになりました。友人たちに トライアスロンのスプリント・ディタンスのチームに入らないかと誘 われてね。水泳の経験があったので、持久力を競うこうした競技の アンカーにはうってつけだったんですね。

triathlon team, and my swimming background turned out to be a perfect anchor sport for doing these endurance events.

I learned pretty quickly that even in socalled “individual” sports, it takes a lot of support around you to succeed. When I qualified for the first Kona Ironman World Championship in 1994, I had no idea what I was getting into. Raul Boca Torres of Boca Hawaii bike shop took me under his wing and didn’t ask for a dime. I got connected with 20-year Ironman veterans who helped me prepare months in advance.

たとえ”個人”競技といわれていても、勝つためには多くのサポートが 必要だということは競技をはじめてすぐに学びました。1994年、第1 回目のコナ・アイアンマン世界大会の出場権を得たときは、自分がど んな世界に足を踏み入れたのかさっぱりわかっていませんでしたが、 自転車ショップ〈ボカ・ハワイ〉のラウル・ボカ・トレスさんがお金もと らずに何から何まで面倒をみてくれました。アイアンマンレースで20 年の経験を持つベテランに、レースの数ヶ月前からみっちり訓練して もらいましたよ。

最初のレースは10時間16分で完走しました。気力と体力のどちらが 欠けていても達成できない記録ですよ。別のコナの予選では食中毒 にやられて、体調は最悪でした。それでも”気力で乗り切る”つもりで力 いっぱい自転車を漕ぎましたが、ゴールの100メートルほど手前で

The race took me 10 hours and 16 minutes—an impossible feat without a balance of mental and physical strength. During another Kona qualifying event, I had a stomach virus and couldn’t hold anything down. I thought, Mind over matter, and put the pedal to the metal. About a hundred yards from the finish line, I dropped to the pavement and just started flopping around like a fish. My brain was telling me, This is going to be the best race of my life, but my body wouldn’t cooperate. Everything has to be in sync.

At Ko Olina, it’s gratifying to play a part in helping people transition to and maintain an active lifestyle. Even if they’ve never been into sports, that curiosity is there. I had a group of retirees go from being nervous about jumping in the ocean to competing in the North Shore Swim Series races over the summer. With a little encouragement, they were able to achieve things they never thought possible.

I recently crossed the Ka‘iwi Channel solo for the first time in the Moloka‘i 2 O‘ahu Paddleboard World Championships, instead of with a relay team. You’re next to all these elite paddlers from around the world, but it’s more about seeing how you handle the elements presented to you on that day— and the massive challenge of being on the

地面に倒れ込み、魚のようにのたうちまわったんです。”人生最高のレ ースにするぞ”と頭では思っていても、身体がついてこなかったんです ね。すべてが調和していないとダメなんですよ。

コ・オリナでは、アクティブなライフスタイルに転向しようという人や、 アクティブなライフスタイルを継続したい人の力になれるのがうれし いですね。退職後、コ・オリナに移り住んだ人のなかには、はじめは海 に入ることさえ怖かったのに今では夏のノース・ショア・スイム・シリ ーズの大会に出場する人もいます。ちょっとした後押しがあるだけで、 絶対に無理だと思っていたこともできるものなんですよ。

今年のモロカイ2オアフ・パドルボード世界大会ではリレーチーム の一員としてではなく個人で初めてカイヴィ海峡を渡ります。世界 中から集まる一流パドラーと肩を並べて競うのですが、大切なのは 自分がその日、自然にどう立ち向かうか。6時間連続でボードの上に 立ち続けるのは大変なことなんですよ。最終区間では頭もぼうっとし て、’80年代の古い歌でも口ずさんでしまうかもしれない。でも、栄養 と水分をしっかり摂り、ポジティブ精神を忘れなければ、人に限界は ありませんよ。

さまざまなスポーツをこなすマルチアスリートとして1992年のモロ カイ・ホエ・アウトリガーカヌー大会出場をはじめ、数度にわたるホノ ルル・トライアスロン優勝やホノルル・マラソンの完走経験、2022年 ハレイヴァ・インターナショナル・オープンサーフィン競技会での上位 入賞など、30年以上もさまざまな競技に挑んできたカーク・フリッツ さん。2010年からコ・オリナ・ビーチ・アンド・サーフ・クラブの会長を 務めています。

board for six straight hours. During the last leg, you might get a little loopy and start singing old ’80s songs. But if you’ve got the right nutrition and hydration, and you can keep a positive mindset, there’s no limit to how far you can go.

Kirk Fritz is a multi-sport athlete with more than three decades of competition under his belt, from paddling the Moloka‘i Hoe outrigger canoe race in 1992, to multiple Honolulu Triathlon wins and Honolulu Marathon finishes, to advancing in the 2022 Hale‘iwa International Open surfing competition. He has served as director of Ko Olina Beach + Sports Club since 2010.

Chelsey Jay: The Cultivator

As told to Anna Harmon Images by Josiah Patterson

Kūpa‘a me ke aloha ma hope o ka ‘āina nāna ia i hānai a puka ‘o ia ma kona ‘ano alaka‘i o kēia mau lā, ho‘oulu ‘ia e Chelsea Jay ka ‘ai a me ke kaiāulu, i luna ho‘okele no Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha.

I grew up in Mā‘ili, and I was incredibly lucky to be surrounded by both the ocean and the mountains as a child. This unique upbringing instilled the deep love I have for my community and culture, which is one of the main reasons I do the work that I do now. A lot of my memories revolve around being at the ocean with our ‘ohana (family), swimming, surfing, camping, and watching the beautiful West Side sunsets. As an adult, I continue to spend time at the ocean and surf, not only for my mental and physical health, but also to connect to my ancestors and my Hawaiian way of being and knowing.

I began attending Kamehameha Schools in the seventh grade and was motivated to learn ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i (Hawaiian language). In my na‘au (gut), I knew I wanted to understand this part of myself more and

わたしはマーイリで育ちました。子供時代に海と山、両方に囲まれ て過ごせたのはとてつもなく幸運だったと思います。自分の故郷や 文化への深い愛情はこの特別な子供時代に育まれたものですし、 郷土愛があるからこそこの仕事を選んだんです。海で泳いだりサー フィンをしたり、キャンプのときにウエストサイドの美しい夕日を眺 めたことなど、小さい頃の記憶の多くはオハナ[家族]と一緒に過ご した海の記憶です。大人になった今も海に行き、サーフィンも続け ていますが、それは心身の健康のためだけでなく、自分の先祖とつ ながるため、ハワイアンとしてのあり方、ハワイアンとしての見聞を 深めるためでもあるんです。

日本の中学1年生にあたる7年生から、カメハメハ・スクール(ハワ イアンの血を引く子供たちが通う、ハワイ文化を重視する私立校) に通い、積極的にオーレロ・ハワイ[ハワイ語]を勉強しました。ハワ イアンとしての自分をより深く理解したいという思いが強かったの で、とれるかぎりのハワイ語の授業をとりました。高校を卒業したら リーダーとしての自分を育ててくれた土地への愛情を胸に、〈ホア・ アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉のエグゼクティブ・ディレクター、チェルシ ー・ジェイさんは食物とコミュニティを育てています。

took as many Hawaiian language classes as I could. My goal after high school was to go to college to be an ‘ōlelo Hawai‘i kumu (teacher), but then I decided to attend college in Seattle to be close to my grandmother. In high school, I went to Waipi‘o Valley with my Hawaiian language class, and later, in college, I had the opportunity to go to Kaho‘olawe with the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana. Having transformative experiences with ‘āina (land and sea, that which feeds) in those spaces with passionate people was eye-opening and showed me that I could perpetuate Hawaiian culture through the integration of ‘āina and education.

大学に進み、オーレロ・ハワイのクム[先生]になるのが夢でしたが、 祖母の近くにいたかったのでシアトルの大学に進学しました。ワイピ オ・ヴァレーは高校時代にハワイ語の授業で訪れましたし、大学時代 は〈プロテクト・カホオラヴェ・オハナ〉の一員としてカホオラヴェ島を 訪れる機会にも恵まれました。情熱あふれる人々とこうした場所でア ーイナ[土地や海。恵みをもたらすもの]に触れたことで新たなものの 見方ができるようになり、アーイナと教育を結びつけることがハワイ 文化の継承につながることにも気づきました。

多くの人々の支援と協力もあり、〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉は、何 世代にもわたって食物を育てながらそこに暮らす人々も育くんでき ました。エグゼクティブ・ディレクターに就任して以来、わたしの目標 は愛する人々や土地のためにアウアモ・クリアナ[組織の目標を達成

With the help of many hands and hearts, Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha has been growing food and growing community for generations. In stepping into the executive director position, my main goal has always been to ‘auamo kuleana (carry this responsibility to move towards collective goals) for the love of my people and this place, and to honor the incredible legacy and vision of this beloved organization alongside our team, board, and community. My hope for myself for the next couple of years is to get really ma‘a (familiar) with this work so that I can understand it deeply and build meaningful pilina (relationships, connections) with the people who love Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha— always moving at the speed of trust.

We have a small but mighty staff who all have a connection to Wai‘anae. I am grateful to work with this team of excellent educators, problem-solvers, and critical thinkers. They have an immense amount of knowledge and expertise that is required to grow food and hold space for the community. But most importantly, they are amazing human beings. Here, the work is gentle and rooted in aloha. You feel really loved, by both the people and the ‘āina.

The more time I spend at Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha and truly understand the history and essence of this place, the more I fall in love with it. In practice, it’s about growing

するための自分の役割]を果たすことと、同僚や理事、そしてコミュニ ティの人々と協力し、人々に愛されてきたこの団体のすばらしい伝統 とビジョンを大切にしていくことです。この先2年ほどは、時間をかけ て信頼関係を築きつつ、仕事へのマア[理解]を深め、〈ホア・アーイ ナ・オ・マーカハ〉を愛する人々と意味のあるピリナ[絆]を結んでいき たいと思っています。

〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉の少数精鋭のスタッフは、いずれもワ イアナエに縁がある人たちです。指導力があり、問題を解決する能力 に長け、深い考察のできる彼らと一緒に働けて光栄です。食物を育て ること、人々の力になることに関してははかり知れない知識を持つ彼 らですが、何より重要なのは一人ひとりが人としてすばらしいという 点です。〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉の仕事は人に優しく、アロハの 精神に基づいています。ここは人からの愛もアーイナからの愛もしっ かり感じられる場所なのです。

〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉で時間を重ね、その歴史や本質をき ちんと理解するにつれ、ますます愛おしく感じるようになりました。実 際の活動内容は、食物を育てること、ケイキ[子供たち]を育むこと、 再生力を重視しながらアーイナを修復すること、人々に食事を提供す ることなどですが、それだけではなく、より深いところで人々を育み、

魂にも栄養を与えているんです。わたしたちの使命は”子供たちの目 と手、心を通して、自然と調和しながら平和に満ちたコミュニティをつ くること”です。アンティ・プアナニ・バーゲスがつけた〈ホア・アーイナ・ オ・マーカハ〉という名前の意味は、”友情のもとに分かち合うマーカ ハの大地”。希望の種を植えることで培われた土地と人との深い絆を 通して、わたしたちは〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉の使命と名前を 体現しています。

food, nurturing our keiki (children), restoring ‘āina in a regenerative way, and feeding people through food. But it’s also about feeding people in a deeper way, through nourishment of your soul. Our mission is “creating peaceful communities in harmony with nature through the eyes, hands, and hearts of the children.” The name of our organization, Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha, translates to “Land of Mākaha Shared in Friendship” and was gifted to us by Auntie Puanani Burgess. We embody our mission and name through a deep relationship with the land and with people and by planting seeds of hope.

友人であり、アドバイザーでもあるマーカハ出身のカムエラ・イーノス さんに言われたのですが、アーイナは正しい人を呼び寄せるそうで す。わたしは、自分がぴったりのタイミングで来るべき場所に来たと思 っています。この場所がわたしを求めてくれるかぎり、なるべく長くこ こにいたいです。なんだか家に帰ってきたような気がするんですよ。

2023年、〈ホア・アーイナ・オ・マーカハ〉のエグゼクティブ・ディレク ターに就任したチェルシー・ジェイさんは、10年の〈マーラマ・ラーニ ング・センター〉勤務を含めて10数年、オアフ島ウエストサイドのアー イナと人々のために働いてきました。今の目標は、自分が育ったワイ アナエの人々の健康と幸せのために貢献することだそうです。

A friend and mentor, Kamuela Enos, who is from Mākaha, said to me that the ‘āina always calls the right people. I feel like I’m in the right place at the right time in my life, and I want to be here for as long as I possibly can, for as long as this place will have me. It feels like returning home.

Serving as the executive director of Hoa ‘Āina O Mākaha since 2023, Chelsey Jay has worked with the ‘āina and community on O‘ahu’s West Side for more than a decade, including 10 years at Mālama Learning Center. Her ongoing goal is to contribute to the health and well-being of Wai‘anae, the community that raised her.

RESORTS

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa

Beach Villas at Ko Olina

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

WEDDING CHAPELS

Ko Olina Chapel Place of Joy

Ko Olina Marina

Ko Olina Golf Club

Ko Olina Station

Ko Olina Center

Laniwai, A Disney Spa & Mikimiki Fitness Center

Four Seasons Naupaka Spa & Wellness Centre; Four Seasons Tennis Centre

Ko Olina Aqua Marina RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES

RESIDENTIAL COMMUNITIES

Kai Lani

Lanikuhonua Cultural Institute

Grand Lawn

Kai Lani

The Coconut Plantation

The Coconut Plantation

Ko Olina Kai Golf Estates & Villas

Ko Olina Kai

The Fairways at Ko Olina

Estates & Villas

The Fairways at Ko Olina

Ko Olina Hillside Villas

Ko Olina Hillside Villas

Centre / Four Seasons Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Campus Seagull School / The Stone

The Harry & Jeanette Weinberg Campus Seagull School, The Stone

Family Early

Early Education Center

Ko Olina Wellness

Ko Olina Wellness Academy / Kuleana Coral Restoration

Hawaiian Railway Society Railroad

Ko Olina is the only resort in Hawai‘i owned by a local family raising generations of keiki in the islands. We are surrounded by the hearts of a Hawaiian community: we mālama our culture and community ʻohana

by embracing neighbors, guests and employees with aloha. As stewards of the ‘āina and ocean, we honor the foundation of our wellbeing.

We invite you to experience our Place of Joy, where aloha lives.

Aulani, A Disney Resort & Spa

Beach Villas at Ko Olina

Four Seasons Resort O‘ahu at Ko Olina

Marriott’s Ko Olina Beach Club

Lanikūhonua

A HAWAIIAN PARADISE WHERE DREAMS WERE REALIZED, LIVES WERE LIVED AND TIMES WERE SHARED.

Located in Ko Olina, or “Place of Joy,” Lanikūhonua was known to be a tranquil retreat for Hawai‘i’s chiefs. It was said that Queen Ka‘ahumanu, the favorite wife of King Kamehameha I, bathed in the “sacred pools,” the three ocean coves that front the property.

In 1939, Alice Kamokila Campbell, the daughter of business pioneer, James Campbell, leased a portion of the land to use as her private residence. She named her slice of paradise, “Lanikūhonua,” as she felt it was the place “Where Heaven Meets the Earth.”

Today, across 10 beautiful acres, Lanikūhonua continues on as a place that preserves and promotes the cultural traditions of Hawai‘i. It allows visitors from around the world an opportunity to experience the rich, cultural history and lush, natural surroundings of this beautiful property.

FIND YOUR PLACE OF JOY

Shops, Restaurants, and Services to indulge your senses.

Hours: 6AM-11PM; Open Daily.

Ko Olina Center 92-1047 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707

Ko Olina Station 92-1048 Olani Street. Ko Olina, HI. 96707

Island

Image by Josiah Patterson