WINTER 2016 DISPLAY UNTIL JANUARY 31, 2017 + LIVING WELL, PAGE 65 THE Good Life

MILK

ONE

WHY

HAWAI‘I?

THE COST OF

& BREAD

DAY WITH THREE ENTREPRENEURS

DO CULTS COME TO

TABLE OF CONTENTS

32 | What Makes Them Tick?

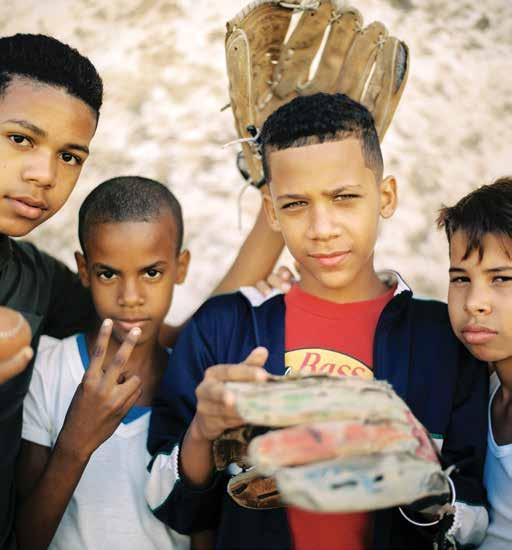

Through a tireless combination of passion, purpose, and perseverance, three entrepreneurs show what it means to live the good life in Hawai‘i. Rae Sojot goes behind the scenes to see what a day in the lives of these individuals is like.

44 | The Staff of Life

If you want a quick metric of the good life, check the price of a gallon of milk and a loaf of bread. Editor-at-large Sonny Ganaden explores how Big Island Diary and La Tour Bakehouse are expanding the local economy, improving the price of everyday items, and by extension, strengthening the purchasing power of local consumers.

54 | The Living Projects

Some call themselves intentional communities. Others are considered alternative spiritualities. At times, they have been labeled cults. Numerous such groups have been drawn to Hawai‘i, and more are trying to start here today. Managing editor Anna Harmon examines why.

Local commodity producing companies like La Tour Bakehouse, which employs 140 people to run its bakery around the clock, are preparing Hawai‘i for a sustainable economic future.

The Staff of Life

| 44 | 4 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| FEATURES |

Kaua‘iʼs

Christa Wittmier, Life of the Party

Austin Kino, A Sailorʼs Life

Living Well

John Koga and his wife, Karin, planned a home remodel that celebrated the aged space of John’s childhood home.

Experience the art of living well in Hawai‘i. In this special section, read a survey of contemporary housing, written by Timothy A. Schuler. Also, discover tips for making over your space, and learn about a few artisans and businesses who can help you do so.

6 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE OF CONTENTS | DEPARTMENTS |

Letter

Middle

Editor’s

Contributors 16 | What the Flux?! The

Class 18 | Local Moco

FLUX PHILES

IN

Micah Doane

22 | Culture Charlie Pereira 26 | Arts Patricia Lei Murray 30 | Fashion Dale Hope

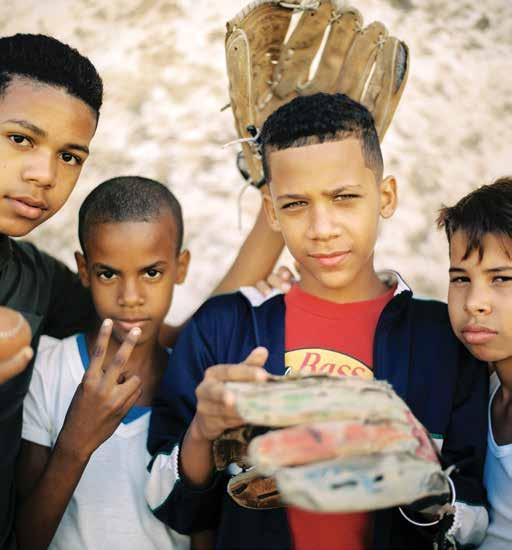

FLUX 90 | Travel Havana, Cuba 96 | Travel

Hindu Monastery 102 | Drink

Hawaiian Shochu 106 | Views

112 | Views

A HUI HOU

Stories

120 | Unheard

| 65 |

SPECIAL SECTION 65 | Living Well

ON THE COVER:

Shown on the cover are Paramacharya Sadasivanatha Palaniswami and Natyam Mayuranatha, who are among the 21 monks who lead spartan but fulfilled lives at Kaua‘i’s Hindu Monastery. A monk’s purpose, Palaniswami says, is to find perfection and to learn to abide there constantly. “Only then can you really share that with others,” he says.

BY BRYCE JOHNSON

We may be a quarterly, but we’re bringing stories all the time online.

STAY CURRENT ON ARTS AND CULTURE WITH US AT: fluxhawaii.com facebook /fluxhawaii twitter @fluxhawaii instagram @fluxhawaii

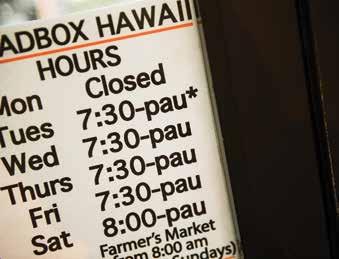

Go behind the scenes and live a day in the lives of some of Hawai‘i’s hardest working entrepreneurs in this video by Jonas Maon. Experience a baker’s hours with Mike Price at Breadbox Hawaii; drop in on Jesse Cruz and Dusty Grable during the lunchtime rush at Lucky Belly and Livestock Tavern; and spend the day cooking seafood with Sean Saiki.

See a recap of what went down at the FLUX Hawaii General Store, a pop-up shop in Abbot Kinney in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Venice Beach. Presented by Hawaiian Airlines, the FLUX Hawaii General Store featured wares from nearly 70 artisans inspired by Hawai‘i’s modern and diverse culture. Video by Leah Barylsky.

8 | FLUXHAWAII.COM TABLE

| FLUXHAWAII.COM |

OF CONTENTS

IMAGE

VIDEO: A DAY IN THE LIFE

VIDEO: FLUX HAWAII GENERAL STORE RECAP

In May 2016, I had the perfect springtime wedding, set beneath clear skies and amid breezy tradewinds. The next day, Sunday, followed with a boozy brunch on a lānai overlooking Sans Souci Beach along Waikīkī’s balmy Gold Coast. We took the following day off from work, and toward its end, while discussing what to do on Tuesday, my now lifelong beau turned to me and said with a shrug, “I think I’ll go back to work.”

My partner (who is featured on page 82) and I both own our businesses. We’ve never been good at vacations, or holidays, or weekends in general. When Sundays roll around, we look at each other dumbly, unable to come up with activities to consume the off-hours. In fact, I am writing this on Sunday morning. A few months back, I started gardening, hoping the plants would be needy enough to fill my nights and weekends. But mostly, like my husband, I work.

Both residents and visitors call Hawai‘i paradise, and it is. A quick perusal of social media reveals beaches that sparkle, waterfalls that tumble, and hikes that soar. But life in Hawai‘i is tough, too. Here, cost of living climbs, median wage (after being adjusted for inflation) declines, and traffic drags. About half of Hawai‘i residents live paycheck to paycheck.

Still, for all our misgivings, life in Hawai‘i is good. Like the people featured in this issue, I am determined to make it work in what is called one of the worst states in the country to do business. After all, the good life isn’t found by chasing the Hawai‘i that so many seek, with its endless days of sun and beach, but rather, by relentlessly pursuing a singular, purposeful passion. We islanders have dug in, committing long, often unglamorous hours at the office—whether that is a kitchen with boiling pots of seafood, or a farm saturated with the scent of manure—to create our own pieces of paradise.

Older, wiser individuals warn my husband and me of burning out, and perhaps one day we will. Maybe then I’ll expand my garden. But for now, we whistle while we work.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

10 | FLUXHAWAII.COM EDITOR’S LETTER | THE GOOD LIFE |

IMAGE BY CHRIS BALIDIO

MASTHEAD | THE GOOD LIFE |

“Since I live in a studio with zero storage space, I implemented floorto-ceiling shelving units to maintain organized living, and got a simple credenza that can hide clutter.”

Life hacks for maintaining a livable space:

“I use furnishings to enhance my home, like selecting white furniture to create an illusion of openness. Organizing my bookshelf by color and height also has a similar effect.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNER

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

EDITOR-AT-LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

Jonathan Canlas

David Chatsuthiphan

AJ Feducia

Bryce Johnson

Jonas Maon

Megan Spelman

Jayson Tuntland

CONTRIBUTORS

Martha Cheng

Brad Dell

Tina Grandinetti

Kelli Gratz

Austin Kino

Jon Letman

Brittany Lyte

Rebecca Pike

Timothy A. Schuler

Jade Snow

Rae Sojot

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Keely Bruns MARKETING & ADVERTISING DIRECTOR keely@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Kera Yong MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Jill Miyashiro OPERATIONS DIRECTOR jill@nellamediagroup.com

Mitchell Fong JUNIOR DESIGNER

INTERNS

Nicole Furtado Aja Toscano

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

“To help remind me my home is a place to unwind, I make sure I have a variety of spaces, both indoor and out, to sit and relax, preferably with company.”

©2009-2016 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher.

FLUX Hawaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and/or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group P.O. Box 38181 Honolulu, HI 96817

herein. FLUX Hawaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fluxhawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

FLUX Hawaii is a quarterly lifestyle publication.

12 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

CONTRIBUTORS

Bryce Johnson

Bryce Johnson is continually inspired by the water, the air, and the mountain valleys of his home island, the last especially so while on assignment photographing the monks at Kaua‘i’s Hindu Monastery for this issue’s cover. “Growing up on Kaua‘i, I had always heard of the property tucked in the mountains on the east side, but never had a chance to visit,” says the commercial and editorial photographer of the story “Soul Searching” on page 96. “The sheer beauty of the property showcased the wide variety of skills these monks have, from the design of the temple to the beautifully manicured landscaping. The community is truly a tropical paradise.”

Tina Grandinetti

Born and raised on O‘ahu, but now living in Melbourne, Australia on the lands of the Koorie nation, Tina Grandinetti has written about indigenous surf culture in Australia, apartheid in Palestine, and demilitarization activism in Hawai‘i. On page 18 of this issue, Grandinetti profiled Micah Doane, who formed Protectors of Paradise to preserve O‘ahu’s west side beaches. “On the day I first met Micah, I was actually planning on going out to swim with the dolphins,” she says. “But after speaking with him, I decided that one less body chasing after the pod would probably be a good thing. I went to Kā‘ena Point instead, and there, I saw the pod passing by offshore.

Doane has shown me and many others that sometimes, connecting with the natural world means taking a step back and allowing it to do its thing.”

Rae Sojot

Growing up in a local military family, and living in Hawai‘i, Colorado, Germany, North Carolina, the East Coast, and Tahiti, Rae Sojot developed a passion for telling the stories of people and their unique cultures. For “What Makes Them Tick,” on page 32, she shadowed local entrepreneurs to gain an intimate look of how hard people in Hawai‘i work, and how success, though welcomed, doesn’t come easy. “We often equate success with glamour and the easy life. Therein lies the irony,” Rae says. “It’s no easy life, but for these entrepreneurs, it is a life driven by passion, and therefore all that much more worth it.”

Megan Spelman

Megan Spelman

As a freelance editorial photographer who splits her time between the coasts of Kona, on the Big Island, and Valencia, in Spain, Megan Spelman enjoys getting glimpses of the amazing people and places she meets while on assignment, including Big Island Dairy farmer Brad Duff, featured on page 44 in “The Staff of Life.” “It’s easy to see Brad’s passion for dairy cows,” she says. “This is one of the last dairies on Hawai‘i Island, where I live, so it was interesting to see where my milk was likely coming from. It is a commercial dairy, but the cows are lucky enough to live in Hawai‘i and have an amazing look out to the Pacific from their fields when they are pregnant.”

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

| THE GOOD LIFE |

Highs and Lows of the Middle Class

How this aspirational social group is faring in Hawaiʻi.

COMPILED BY NICOLE FURTADO, ANNA HARMON & LISA YAMADA

While William Howard Taft was the first U.S. politician to use the term “middle class” in his presidential nomination acceptance speech in 1908, Aristotle wrote of the necessity of such a group all the way back in 4th Century BC. In Politics, the philosopher declared that a dominant middle class, which worked hard but didn’t aspire for too much, and which neutralized the dislike between the poor and the rich, was key to maintaining a constitutional government. (Of course, women and slaves had no political power then, so it was a flawed concept.) Still, today, thought leaders extol its virtues, including Amazon founder and venture capitalist Nick Hanauer, who said, “A thriving middle class is the source of growth and

prosperity in capitalist economies.” The rapid rise of an American middle class after WWII soon triggered a sustained fear of its disintegration. As early as the 1970s, conversations arose about the stratification of wealth and the loss of the middle class, what Vice President Joe Biden called the “backbone of this country” in 2009. Though middle class is defined in finite economic terms by percentages of median income, those who identify as middle class do not reference these delineations. Instead, the idea of the middle class represents something less tangible, an American dream that allows for a moderate lifestyle, home ownership, and a secure future. But what does this look like in Hawaiʻi?

THE BUDGET:

$66,374

Annual income before taxes needed to lead an average middle-class life in urban Honolulu.

Lower middle income: $49,200 Upper middle income: $146,900

Lower middle income: $42,000 Upper middle income: $125,00

240% vs . 108%

Between 1948 and 2013, worker productivity increased by 240%, but wages of the average employee grew by only 108%.

In 2015, for the first time in more than four decades, middle-income households no longer made up the economic majority in America (49.9 percent in middle class versus 50.1 percent in upper and lower class), though Hawai‘i bucks the trend, its middle class having grown 4 percent since 2000.

46 percent of U.S. workers earning less than $15 an hour are over 35 years old.

The Resident Alien Act gives foreigners the rights to buy land. Though the Kuleana Act authorizes land titles for all Native Hawaiian tenants living on the land, most never claim it.

Housing: $27,880

Car costs: $8,920

Retirement savings: $4,368

Healthcare: $4,056

Food: $9,346

Entertainment: $2,258

Child care/education: $2,300

Vacation: $3,561

Other: $3,685

Average annual expenditures spent by households earning between $50,000–$100,000, adjusted for inflation, according to a 2013–2014 report by DBEDT on consumer spending in Hawai‘i.

| THE MIDDLE

|

WHAT THE FLUX

CLASS

population lives in rural areas. 1835 1850 1890 In

Tax

nonHawaiians control more than a million acres. 1848 1868–1906 Early 1900s 1935 1820s King Kamehameha III imposes the Great Māhele, introducing private land ownership in Hawai‘i. Groups of Japanese, Portuguese, Korean, and Filipino plantation workers arrive in the Hawaiian Islands. The development of department stores and large offices leads to a “white-collar” work force. The U.S. Fair Labor Standards Act establishes minimum wages, the 40hour workweek, overtime pay eligibility, and child labor standards. TIMELINE THE BASICS THE MIDDLE CLASS IS DEFINED AS WHO IS THE MIDDLE CLASS? HAWAI‘I

UNITED STATES

Goods such as textiles and shoes begin to be produced in factories in New England, though the majority of the U.S.

the Kingdom of Hawai‘i,

William

Hooper of Ladd & Co. arrives on Kaua‘i to manage the first sugar plantation.

records reveal that Native Hawaiians own only an estimated 250,000 acres of land;

67 % 200% of median household income middle income upper income lower income INCOME

2014 63% 15% 22% 2000 59% 13% 28%

BREAKDOWN IN HONOLULU

IS THE MIDDLE CLASS THRIVING, OR JUST SURVIVING?

Hawai‘i has the 3rd highest median household income in the nation, but also one of the highest costs of living.

$100 feels more like $85 in Hawai‘i, as a result of cost of living.

47 hrs/week

The average amount of hours worked by adults employed full time.

Nearly half of Hawai‘i families live paycheck to paycheck.

1/4

Portion of Hawai‘i residents who had a car breakdown and didn’t have enough money to fix it.

32%

Percent of households that would not have enough in liquid assets to survive for three months at the poverty level in the absence of income.

47

TH

Hawai‘i’s ranking in the nation for home ownership, with 56.6% of residents owning homes in 2015.

MEDIAN SALES PRICE OF A HOME IN 2016

In the U.S.: $221,500

In Hawai‘i: $566,900

In Honolulu: $747,500

MONTHLY COST OF HOUSING

new GI Bill gives millions of veterans returning from WWII money for home mortgages, businesses, and college educations.

The number of subdivision homes jumps to 1.7 million.

LIVING WAGE* AFTER TAXES FOR HOUSEHOLDS IN HAWAI‘I

5 ¹/4 24- hr days

How much a single parent with two children, who is earning Hawai‘i’s minimum wage of $8.50 per hour, needs to work per week to earn a living wage.

*The living wage is the minimum a family needs to not require public assistance in order to avoid severe housing and food insecurity, assuming there are no savings.

Hawai‘i has the 3rd highest housing costs, behind those of New Jersey and Washington D.C.

43% of annual income

How much homeowners in Honolulu spent on housing related expenses in 2014. Renters in Honolulu spent 47.3% of annual income on housing related expenses in 2014.

1/4

Portion of Hawai‘i residents who have worried about how they would pay a month’s rent or mortgage within the last five years.

Hawai‘i becomes the 50th state. Jetliners begin regular air service, rapidly increasing both tourism and the retail and construction industries.

$34.22

The amount a person in Hawai‘i must make per hour in order to afford rent for a two-bedroom apartment at a market rate of $1,780, making Hawai‘i’s housing wage the highest in the nation. The annual income needed to afford this: $71,184.

Hawai‘i has the highest percentage of multigenerational family households at 7.7 percent.

REALITY 1944 2009

1955

1959

THE

The

1978

land

support. Hawai‘i’s

rate peaks

7.3%. 1946 1961 2002 2015 The International Longshore and Warehouse Union leads a sugar strike across Hawai‘i that gives plantation workers more rights and better pay. 1958 Bank of America introduces the first plastic charge card, allowing consumers to purchase goods and services on credit. The Civil Rights movement allows African Americans broader access to education and home ownership, contributing to the swift rise of a Black middle class. President George W. Bush implements tax cuts aimed to stimulate the economy after the 2001 recession; income inequality grows. For the first time in 45 years, the middle-income bracket is no longer the majority in the U.S., though in Honolulu, middle-class households remain on the rise.

Office of Hawaiian Affairs aims to remedy wrongs perpetuated against Native Hawaiians, including recovering income from illegally obtained

and providing Hawaiians with financial

unemployment

at

$26,203 $39,133 $51,250 $55,797 $67,916

IN HAWAI‘I, FOR A FAMILY OF FOUR WITH TWO WORKING ADULTS: $17.43 $8.50 $6.00 $10.10 wage needed to live wage to live in poverty current minimum wage minimum wage in 2018

MEDIAN

$1,477 $2,248 $1,500 $950 US Hawai‘i MORTGAGE RENT $3K $2K $1K

MIDDLE CLASS

SHELTER

HOME OWNERSHIP IS A CORNERSTONE OF

IDENTITY.

Keepers of Mākua

Micah Doane and his small band of volunteers help protect what so many others enjoy as paradise.

TEXT BY TINA GRANDINETTI

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

It’s early morning in Mākua on O‘ahu’s west side, and rain lingers in the valley that rises behind the beach. Out at sea, skies are beginning to clear. A small crowd of people are scattered along the water’s edge, scanning the bay for the sleek curve of a dorsal fin, or a burst of fine mist coughed into the air. Micah Doane approaches the crowd with a customary head nod and “howzit.” In a T-shirt and boardshorts, he looks like any other guy preparing for a morning dive, save for the laminated sheet of paper he holds in his hand. “You guys here for the dolphins?” he asks.

Doane is the co-founder of Protectors of Paradise, an informal group of divers and community members who have stepped up to mālama, or care for, this stretch of the Wai‘anae Coast. “We’re out here today making sure people know that interacting with dolphins can be really bad for them,” Doane says. The paper he is holding has a graphic depicting how the marine mammals rest: They dive and surface in sync with their pod, their eyes still open though half of their brains are turned off.

Mākua Beach has become famous for the dolphins that visit its waters. “[They] come into this bay to sleep, but with so many people and tour boats chasing after them lately, it’s disrupting their resting habits and might be making them less fit to survive,” Doane explains. He and other Protectors of Paradise volunteers spend as many mornings as they can educating divers and tourists on dolphin behavior, and documenting interactions that may put the aquatic mammals at risk. It is just one among a variety of activities they’ve undertaken to meet the area’s growing needs.

Doane can date his ties to Mākua as far back as the late 1800s. His paternal great- greatgrandmother, Malaea Naiwi, moved from Hawai‘i Island into the community of Native Hawaiians who farmed and fished in the area. In the 1940s, the U.S. military evicted the population in order to clear the valley for live munitions training. Cultural sites were destroyed and forests burned. Rooftops of family homes and the neighborhood church were painted with white X’s, then used as target practice for aerial bombardment. “The only land they didn’t touch was the cemetery by the beach, but you can see bullet holes and chunks missing out of the grave markers,” Doane says.

Through the decades, where the valley meets the sea, some Native Hawaiians continued to live in an encampment that they referred to as a pu‘uhonua, or place of refuge. Subject to the threat of eviction, its size fluctuated into the late ’90s, but the presence of this insular community kept the number of visitors low. While the valley was off-limits, the beach was still a primary place where families went to gather food from the sea.

Doane, too, maintained his connection to Mākua. “Because this place is so isolated, there’s always been a lot of illegal dumping going on here,” he explains. As a child, he and his family regularly drove out from Pearl City to do beach clean-ups and to tend the community cemetery (a task now carried out primarily by Uncle Moku Neil, whose family also hails from Mākua).

As the number of visitors to Mākua Beach on O‘ahu’s west side surged due to social media, Micah Doane formed Protectors of Paradise to help keep beaches clean.

LOCAL MOCO |

MICAH DOANE |

18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 19

“Having those ties with the area and being raised by descendants of Mākua instilled in us to take care of our land and resources,” Doane says.

The pu‘uhonua at Mākua Beach came to an end in 1996 after a sweep by the city. Over the last few years, Doane has seen a massive surge in the number of visitors, and subsequently, the amount of trash, on the beach at Mākua, which is part of the Kā‘ena Point State Park Reserve. “As social media became more popular, this place became famous for underwater photography because of its crystal-clear waters and the dolphins,” he says. As the number of visitors skyrocketed, spontaneous beach clean-ups were no longer adequate, and Protectors of Paradise was formed. “With each Instagram post, the influx of people grew,” Doane says.

That inundation hit a high point in summer 2016, when thousands of people flocked to Mākua over the Fourth of July weekend. By Sunday afternoon, trash was piled high along the beach. With no facilities onsite, some overnight campers dug latrines in the brush, provoking fears of water and soil contamination. This incident, and others

like it, highlighted the state’s neglect of this stretch of coast—there is only one Hawai‘i State Parks maintenance worker assigned to Mākua and neighboring Keawa‘ula, also known as Yokohama Bay.

When the weekend ended and the campers dispersed, Protectors of Paradise showed up to pick up the slack, filling trucks with collected waste and debris. Since then, the group’s members have been working to help the community and state find a resolution to this growing problem. “It’s not just the trash,” Doane says. “It’s people abusing the wildlife, turtles getting caught in nets, water getting polluted. There’s unexploded ordinances and maybe even depleted uranium in the valley— the result of military training. It’s one side of the island that gets the last say in anything. It’s been the last priority.”

Paradise or otherwise, Mākua has seen its fair share of abuse over the years. But there have always been the quiet few who have worked to protect it. For Doane, there’s hope in that. “If a few people could have an impact,” he says, “imagine what a whole island could do.”

The west side of the island is often lowest priority according to Doane, left, who heads over every week to care for the Wai‘anae Coast.

For more information about Protectors of Paradise, follow them on Facebook.

20 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Weaving Tales

Charlie Pereira is one of the last practitioners of throw net making.

TEXT BY BRITTANY LYTE

IMAGES BY BRYCE JOHNSON

A fishing net can make a grown man weep. Just ask master net weaver Charlie Pereira. He will tell of the devoted fisherman whose wife presented him with one of Pereira’s hand-sewn throw nets as a surprise gift.

“He cried,” Pereira says at the end of the story, pausing to allow reaction time. “Cried!”

It’s Sunday afternoon, and Pereira is at his usual post, a folding chair at the Anahola Farmer’s Market on Kaua‘i, with a bamboo needle in hand and a fistful of fishing line. As usual, he is engaged in equal parts net knitting and talking story. When there’s a lull in conversation, he rattles off anecdotes for his own merriment as much as anyone else’s. Unreeling a string of flashbacks from his 87 years of life, Pereira exudes the ease of a man who has spent the bulk of his days doing the thing that truly makes him thrive.

One of Hawai‘i’s last practitioners of traditional throw net making, Pereira has been weaving nets by hand for three quarters of a century. He was taught by his father, an avid fisherman who was 4 when he moved to Kaua‘i from Portugal in the care of his own father, who had sought employment in the booming sugar plantation industry. Growing up on Kaua‘i’s southern shore, Pereira’s dad learned the art of making throw nets from Hawaiian fishermen. While pre-contact Hawaiians used nets for fishing, throw nets were an import of Asia, brought to Hawai‘i in the late 1800s by Japanese immigrants who were recruited as plantation workers. Locals quickly popularized the practice. When Pereira was 7, his father began teaching him to knit the fishing device by which their family was able to eat.

Pereira still remembers the day he completed his first net. He was 12, and, elated with his creation, he rushed off to test it in the shallows at Nawiliwili. Pereira collected just one fish FLUX PHILES | CHARLIE PEREIRA |

One of Hawai‘i’s few practitioners of traditional throw net making, Charlie Pereira has been sewing nets by hand for three quarters of a century.

22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 23

from the sea that day, but he was happier about it than any of his catches since. It was his first unsupervised nab in his first selfmade net.

Before large companies like Matson and Costco globalized the way Hawai‘i eats, fishing was as essential to survival as breathing. More than spears, hooks, or traps, the throw net was the plantation era fisherman’s most promising tool to collect many small- and medium-sized fish in a single grab. But today, the way Hawai‘i feeds itself has been transformed, and the barge— not the net—is now the primary source of sustenance. And in a time when a net can be procured in minutes from any store, there is little incentive to knit one’s own. As such, an ancient skill is disappearing.

From a task that many consider avoidably tedious, Pereira derives a kind of moving meditation that puts him at ease. Measuring 11 feet in diameter, each of Pereira’s throw nets requires four weeks of daily labor. He sells them for $300 apiece, a small price to pay for artistry of this kind. If you want one of Pereira’s nets, you must get your name on his waiting list, of which there are two. And

it’s clear which one you want to be on: “If the person’s nice to me, he gets one real fast,” Pereira explains. “Otherwise, he can keep waiting. One guy has been waiting 10 years!” Pereira guesses his hands have stitched about 80 throw nets, some for hobby and most for income. He’s proud to say that at least one of them is in use on each of the main Hawaiian Islands.

“Everybody wants one of Uncle Charlie’s nets,” Pereira says. As if to signal a warning of his disinterest in modesty, he is fond of wearing a matching T-shirt and trucker hat emblazoned with this slogan: “If things improve with age, I’m getting pretty near perfect.”

Despite this saying, age has made it harder for Pereira to fish in recent years. He is less sturdy on his feet, and he worries a wave might knock him into an impetuous sea. These days, he has all but given up the practice. But his hands, wrinkled like crepe paper and big like shovels, are still amazingly nimble. They pain him every now and again, and when they do, he breaks from the net, taking a few minutes to exercise his storytelling muscle instead. Then he picks up the needle and continues weaving.

Measuring 11 feet in diameter, each of Pereira’s nets requires four weeks of daily labor to complete.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX PHILES

| PATRICIA LEI MURRAY |

Stitches in Time

Patricia Lei Murray’s Hawaiian quilts have sown stories for more than three decades.

TEXT BY JADE SNOW

IMAGES BY JONAS MAON

“It all stems from the piko,” Patricia Lei Murray says while gingerly seated on her living room couch, a perch where she has spent countless hours poring over a wooden hoop, weaving memories into Hawaiian quilts. Murray compares the center and starting point of each design to the spiritual piko, or center, of one’s own body. “Piko pondering, shall we say, is really the driving force to make a commitment to each quilt and stay on task. It has to come from your na‘au,” she explains, referencing the gut instinct that often denotes a Hawaiian code of ethics. Hawaiian quilting features radially symmetric appliqués of native flora and fauna, made from a single cut on folded fabric, that are stitched to a backing to create an artful scene. Murray first experienced this craft in the 1980s through Kamehameha Schools’ continuing education program, and has dedicated her time to it since, balancing the passion with family and work. Depending on both its size and one’s technique, a single quilt can take years to complete. “I taught time-management seminars to public and corporate clients for 11 years, so finding time for quilting was never a concern,” Murray says. “My motto is, ʻWhat you value, you make time for.’ I quilt every day. I make time for it. It is my daily meditation.”

The septuagenarian describes her prized quilts in the same loving tone that she speaks of her mo‘opuna, or her grandchildren. She can explain, in detail, the name and origin of each finished piece and its components. When quilting became popularized at the end of the nineteenth century, early Hawaiian quilters were limited to available materials, primarily solid colors and heavy cottons. Today, a diverse array of fabrics allows Murray to add depth and texture to her quilts, dynamic creations that tell a story through pattern and stitching. These elements also bear emotional significance to her life, which can be seen as she unveils sentimental keepsakes in her living room: One quilt features a collection of lace doilies from her travels in Paris; another showcases silk ferns, secured with delicate wedding veil tulle. In 2006, Murray reached the pinnacle of her quilting career with a solo exhibit at the La Conner Quilt and Textile Museum in Washington; it was the first time the museum had focused an entire exhibition on Hawaiian quilts by a single artist. Among the 30 quilts on display was one called “Ku‘u Hae Aloha Mau,” a Hawaiian flag quilt honoring the legacy of Queen Lili‘uokalani. Although other quilters create similar designs bearing the same powerful symbolism, each takes liberties to add personal elements that distinguish his or her own handiwork, and Murray is no exception. Through each of her flag’s blue stripes, she had stitched, in blue thread, the lyrics to “Ku‘u Pua I Paoakalani,” an added touch so subtle that it is barely visible to the naked eye. The song details the beauty of the queen’s

“Piko pondering, shall we say, is really the driving force to make a commitment to each quilt and stay on task,” says Patricia Lei Murray, who has been sewing Hawaiian quilts for more than three decades.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 27

garden (named Paoakalani), as well as the young man who delivered flowers wrapped in newspaper to ‘Iolani Palace during the queen’s imprisonment. The delivery kept the royal informed of news outside the palace gates during the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy. Murray shares the importance of this quilt with tears in her eyes, recalling the overthrow and the public removal of the Hawaiian flag, a time when women were forced to grieve silently for their lost nation, sewing their pain into quilted flags, which they hung in their homes. Today, Murray’s flag quilt hangs in the gallery of the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a symbol of hope and pride for the community.

More than 30 years since she first tried her hand at the craft, Murray remains drawn to

the level of devotion required to make a quilt. She has created more than 125, many of which have been displayed across the country, and has penned two books detailing her awardwinning work. She teaches monthly quilting classes from her home in Honolulu, creates commissioned pieces for quilt aficionados, and rescues unfinished quilts for families eager to see the work of their kūpuna completed. Though millennials have yet to embrace modern-day quilting as meditation, Murray says she hopes the next generation will continue practicing Hawai‘i’s proud art forms: “I would encourage the young people who are interested in any of the cultural arts to be brave, to learn and study, and make it a part of themselves, so that it becomes something they love and are willing to share.”

Murray’s passion for Hawaiian quilting can be seen in the more than 125 quilts she has created, many of which have been displayed across the country.

28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX PHILES

Strong Fabric

Dale Hope has spent nearly half a century immersed in the prints of the islands.

TEXT BY REBECCA PIKE

IMAGE BY JOHN HOOK

“It’s so special up here,” says Dale Hope on his Pālolo Valley lānai. His redwood pole house, which looks and feels like a treehouse, is draped with vegetation on all sides. Occasional birdsong interrupts the quiet whirring of palms rustling in the wind. Endlessly inspired by such nature, as well as the cultures of the only home he has known, Dale has spent the majority of his life immersed in the printed and painted textiles of Hawai‘i.

In the 1970s, Dale began working for the garment manufacturing business that his father, Howard R. Hope, started in 1953, the year Dale was born. What began as schlepping fabric bolts at his dad’s factories became a lifetime of singular devotion. Together, they launched menswear label, HRH—short for His Royal Highness, and also his father’s initials—to accompany Howard’s ongoing womenswear brand, Sun Fashions of Hawaii. It would have been simple enough to make this resort wear in perpetuity, but the young Dale was excited by the shirts he and his surfer friends wanted to wear, and so he capitalized on his resources to create several additional lines, starting with T-shirts under the Hawaiian Style brand, and then moving on to aloha shirts under Kahala by HRH. (Kahala had been one of the first well-established aloha shirt brands in Hawai‘i, but it had gone dormant, and Dale was eager to revive it.) In the decades to follow, he went on to create some of the most popular and enduring aloha shirts in the world.

“I’m not really into fashion,” Dale insists. “But I am really interested and excited to talk aloha shirts and create shirts. Aloha shirts are what told the story of Hawai‘i to the world.” His adoration for what he calls “the emblem of Hawai‘i” is lovingly depicted in The Aloha Shirt . Rereleased in 2016, approximately 16 years after he debuted the first edition, the remastered 400-page book is as much a testament to Dale’s passion as it is a living history of what is known as the “Hawaiian shirt” on the mainland. Amalgams of his own rich experiences, and memories of elders in the manufacturing scene, paint a picture of the infancy of the industry as the birth of an art form. Marvelous scenes and lush, hand-brushed prints parallel the text.

Dale is rhapsodic in his description of artists like Elsie Das, who in 1936 collaborated with her brother-in-law, G.J. Watumull, to reproduce Hawai‘i-inspired prints on raw silk shirts, as well as John Keoni Meigs, who painted scenes from exotic Hawai‘i in the many radiant colors of the islands. “I actually got to sit down and talk with these people,” says Dale, who remains in awe of having had first-person history lessons from those who lived during that nostalgic slice of history, when visitors arrived to the islands in increasing droves. The business owner and historian also recalls the late 20th century retailers that propelled the aloha shirt through decades of popularity by creating and selling the finest designs the industry had to offer.

As to what these prints look like, Dale sums up the essence of an aloha shirt as such: “It must have a reverence to whatever it is, some singular essence of Hawai‘i that is your starting point. A flower, a fish, a canoe, a tree. These things have stories. You want to dutifully, properly, tell that story through the shirt.”

Dale Hope has spent the majority of his life immersed in the printed and painted textiles of Hawai‘i.

The Aloha Shirt is available at select stores and online at thealohashirt.com.

|

DALE HOPE |

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

What Makes Them Tick?

Twenty-four hours in the lives of three local entrepreneurs show what it means to make a good life in Hawai‘i through passion, purpose, and tireless perseverance.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Dusty Grable and Jesse Cruz are the forces behind Breaking Bread Hospitality Group, under which they have debuted three culinary destinations in four years: Lucky Belly, Livestock Tavern, and The Tchin-Tchin! Bar, shown here.

FLUX FEATURE

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 33

It’s 4 a.m. and Mike Price is in the zone, glazing donuts and cinnamon rolls for their debut in the day’s glass display case. Bread is rising in the oven, giving Mike a respite from the meticulous ingredient scaling and dough mixing that he arrived six hours prior to perform. Sauces and gelées are attended to, all of which are made from scratch.

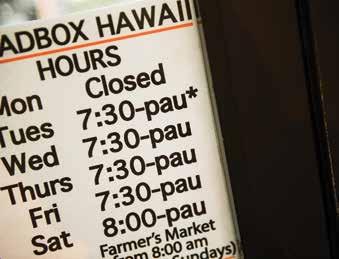

Mike is the one-man baking operation behind Breadbox Hawaii, a Japanese-style bakery tucked away in Manoa Marketplace. With nearly 40 items created on a daily basis—from kimchee muffins to liliko‘i bundt cake—there’s scarcely time for Mike to take a break, much less to make any misstep. A hungry, carb-seeking crowd arrives promptly at 7:30 a.m., when the shop opens, so the trays must be filled and the bread shelves stocked. Mike burns the midnight oil, but he’ll be damned if any loaves get burnt on his watch.

With his broad shoulders, board shorts, and tattooed arms, Mike looks more suited to beach breaks than bakeries. He grew up surfing Sandy Beach, his athleticism echoing in his fluid movement in the kitchen. This Kailua-bred local is no stranger to business. He and his wife, Maria, operate a media production company and also own Baby Awearness, a family lifestyle boutique located above Breadbox Hawaii, where Maria stocks baby goods and provides doula services. In 2015, when Mike and Maria were considering opening a bakery in the space that had previously housed Manoa Bakery, the duo’s entrepreneurial drive made the decision easy. Mike enjoyed cooking and had worked at his mom’s pizza restaurant as a teenager. Maria’s business acumen easily dovetailed with her passion for food. The question wasn’t why a bakery, but why not? Once the lease was freshly inked, Mike became a quick study in all things baking, courtesy of trial and error and YouTube videos. “I basically taught myself how to bake bread in three months,” Mike says, shaking his head. An obscure Japanese breadmaking book also served as a resource. Maria, a native Japanese speaker, would translate the oftenmystifying instructions. “A seed to start the bread? What seed? I had no clue what the recipes would be calling for,” he recalls.

The baking life may appear blissfully domestic to outsiders, but running a bakery demands the lion’s share of the Prices’ time and energy. Personal luxuries like free time have become rarities, anxiety and stress, the common currency. Yet the couple’s hard work and sacrifices are leavened by a sweeter outcome. Breadbox has evolved into a family-centered space for Mike and Maria.

Six days a week, while Mike is on the homestretch working at the bakery, Maria and her sister, Mayu Kawata, rise at dawn to tackle the morning’s household chores— laundering diapers, feeding the dog, waking the kids, and gathering essentials for the day. Once the crew is galvanized, they pile into the car and head over to Breadbox. At this point, the bakery becomes a family affair, with everyone working in concert in the kitchen. As Mike applies the finishing touches to the medley of pastries, Maria and Mayu prep for opening and bag breads. Their older son, Gee, is tasked with writing labels and filling trays. (On weekends, when Mike’s 9-year-old daughter, Azlyn, joins, she shares work with Gee or runs errands at Safeway.) Fourteen-month-old Mickey, however, boasts the best job. Dubbed Breadbox’s official taste tester, he’s happy to double-fist mini French crullers and stuff them into his mouth. It’s a sort of reverse family hour: Instead of gathering over dinner, the family bonds at breakfast amid trays of gleaming pastries and freshly baked bread.

Once the shop’s doors open, Maria takes the helm, her infectious personality a complement to Mike’s frank nature. Though her husband does the hard labor, it’s Maria who provides the panache and good-natured steadiness, when Mike’s lackof-sleep-induced delirium hits, making for comical banter that elicits chuckles from patrons within earshot.

While Maria and Mayu handle the steady flow of customers, Mike slips out to take 8-year-old Gee to school. If the day’s baking is done, he’ll head to the store to stock up on kitchen necessities, or maybe seek out a specialty ingredient for a newly conceived baked good idea. If he’s lucky, like today, he can head home—and straight to bed.

Breadbox’s hours are listed as “7:30–pau,” with pau translating to when the

Mike Price, the one-man operation behind Breadbox Hawaii, begins baking at 9 p.m. and continues until 6 a.m., when his wife, Maria, their kids, and Maria’s sister come to help prep for opening the 7:30 a.m. opening.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 35

daily inventory is significantly lighter, or as often is the case, completely sold out. With Mayu working the register, Maria ticks off administrative tasks, and makes a quick dash to the bank to refresh the till. Mic-key, situated on Maria’s hip, grins: Instead of French crullers, he’s now occupied with rolls of coins. As the morning progresses, the items dwindle. Maria surveys the glass display case with satisfaction. Only a handful of lonely muffins and anpans—Japanese rolls filled with sweet red bean paste—remain. These are swiftly packaged to donate to the nearby church.

As the bakery’s popularity increases, so too does the work required to feed its ever-increasing fan base. “The exhaustion is real,” says Maria, who was pregnant with Mic-key when plans for Breadbox were first sketched out. He was born around the time that Breadbox debuted. Life hasn’t slowed down since. But the triumph is worth the toil. The family’s passion to provide made-from-scratch, additive-free food has resonated with the community, whom the Prices consider an extension of their family. To them, this is the real success. “Mike always wanted people to feel like they walked into grandma’s kitchen,” Maria says. “It smells good, it feels good, and you know you’re going to get spoiled.”

By mid-morning, Maria and Mayu run a final sweep over the black and white checkered floor before closing the bakery doors. Then they climb the stairs to Baby Awearness for their second shift of the day.

Early sunlight slants through the windows at The TchinTchin! Bar in Honolulu’s Chinatown, creating blocks of diffused color on the brick walls. It ʼ s a hushed but amiable atmosphere, early enough for the restaurant’s crew to exchange morning pleasantries, but still too early for lively conversations. Employees are in the midst of the daily routine: polishing the long bar, sorting cutlery, transferring boxes of supplies. In a corner booth, several servers and managers have assembled, pulling out binders and notebooks. It looks like study hall, save for the tidy row of wine glasses at the head of the table.

It’s 8:30 a.m., and Dusty Grable is holding a wine class. Grable and Jesse Cruz are the forces behind Breaking Bread Hospitality Group, their shared enterprise that, not long ago, was the stuff of dreams, cooked up while the two were working as waiter and cook at Formaggio’s in Kailua. In a mere four years, the duo has debuted three bright stars in Chinatown’s growing constellation of culinary destinations: Lucky Belly, Livestock Tavern, and The Tchin-Tchin! Bar. This year, Livestock Tavern picked up Honolulu Magazine’s Hale ‘Aina Award for Best New Restaurant, conferring upon Grable and Cruz the title “Champions of Chinatown,” a moniker the pair cringes at. For these restaurateurs, the mantle of celebrity still feels unwieldy.

Grable is a bit bleary-eyed from last night’s dad duties to 2-month-old Paisley Bay, but he still looks the part of dapper

Breadbox is a family affair, and the Prices’ commitment to providing made-from-scratch, additive-free food has resonated with the community.

sommelier professor, dressed in dark jeans, leather wingtips, and a knit sweater. As students sniff, swirl, and scrutinize the wine, he explains technical terms and presents complex scenarios: “What might pair well with, say, a charred sponge cake topped with seared foie gras?” The class is a nine-week intensive that Grable offers, free of charge, to any of Breaking Bread’s 80-plus employees interested in upping their wine game. Grable created the course materials for the class, collating his personal notes into study binders. By investing in the staff, Grable and Cruz help employees build both their skillsets and confidence levels, tools the two believe bode well even beyond their restaurants’ walls.

Bison, the resident canine, shuffles inside to the crew’s delight, indicating that Cruz has arrived. Cruz is a study in quiet confidence, his solid frame a mirror to his talents in the restaurant world. He and Grable are two sides of the same spinning coin—while both are humble, dedicated visionaries, Cruz serves as the steady, reserved counterpart to Grable’s enthusiasm and zeal.

36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Cruz generally spends mornings touching base with his kitchen managers, confirming preparations for the imminent lunchtime rush and subsequent dinner service. A recent surge in hiring interviews and plans for a catering component have also demanded swaths of time. Today, though, a solo strike mission to a Waimānalo plant nursery is in order: Cruz wants to refresh Tchin-Tchin!’s living wall display. “It’s nice to get out of Chinatown,” he says, getting into his car with a trace of a schoolboy playing truant. He turns up the music. Even driving is fun. The past few years, Cruz rarely went beyond Honolulu’s concrete jungle—save for weekly workout treks up Koko Head Crater or visits with family in Makakilo. Maintaining the multiple restaurants has been thrilling and exhausting in equal measure, and similarly demanding of time.

While Cruz is out buying plants, Grable wraps up the wine class and checks the restaurants’ activity—Livestock Tavern is next door to Tchin-Tchin!, and Lucky Belly is across the street—before settling into a series of potential employee interviews. Flipping the switch from businessman to family man is no easy feat, but whenever a pocket of time bubbles up, he takes advantage. Today, after the interviews, he slips home to his two-bedroom apartment on the corner of Nu‘uanu Avenue and Beretania Street—a brief twoblock walk away—to hang with Paisley Bay and Grandpa Paul (Grable’s father), who has brought lunch. Cruz, too, enjoys quick family moments: His mom stops by every day at lunchtime, and his daughter, Kelsie, 18, works at the restaurants as a server.

By noon, Livestock Tavern and Lucky Belly are in high gear, satisfying the lunchtime crowd until both restaurants close at 2:30 p.m. to prep for dinner service. The Tchin-Tchin Bar!, not yet open, is still warming up, its telltale red carpet primed for display at the downstairs entrance in a few hours.

Between lunch and dinner service, the day crew passes the baton to the evening shift at “family dinner”—the weekly shared meal during which employees sit down and, like their company’s namesake, break bread together. The chefs take turns making the meal, and tonight Cruz is in the kitchen.

When Grable, standing, and Cruz opened Lucky Belly, the two were often the first to arrive, at 7 a.m., and the last to leave, at 3 a.m.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

He has prepared local comfort favorites: large pans of chicken long rice, lomi tomatoes, and kālua pig. A convivial intimacy fills Livestock Tavern’s dining room as the staff laughs and mingles. It’s a sweet interlude before the night’s inevitable accelerando. Amid the tinkling of silverware and conversation, Cruz and the head kitchen manager review the upcoming fall menu. Grable confers with the beverage staff. There’s always work to be done.

Aristotle’s concept of the whole being greater than the sum of its parts is in live, vibrant display come evening, when all three restaurants are open and humming like well-oiled machines. Grable moves fluidly—troubleshooting, assisting, encouraging—between the three venues. A back stairwell connects Tchin-Tchin! to Livestock Tavern, where Cruz is positioned at the invisible threshold between the kitchen and the dining room floor. He’s “calling the wheel,” a term used for the person who keeps a constant finger on the restaurant’s pulse, syncopating the speed and flow between the front of the house (hosts, servers, bussers) and the back of the house (line cooks, prep cooks, dishwashers). Cruz executes the role with calm precision and elegance, and the crew follows en suite. The kitchen reverberates with steady, consistent energy, producing 200 meals over the next three hours. It’s a nightly orchestration, well tuned and well earned. “We are a team,” Cruz says.

Around 10 p.m., the fervor of Chinatown’s dining scene eases to a slower, contented pace. “We used to be the very first people in and the last people to leave,” Grable says. “When [we] first opened Lucky Belly, it was typical for us to arrive at 7 a.m. and leave around 3 a.m.” But like all good leaders who learn the importance of delegation, the pair now trusts others to take the reins—an act that has been a bittersweet growing pain for the two partners, who are still adjusting from their early roles of waiter and cook to feted players in Chinatown’s restaurant vanguard. “Your thoughts are always occupied with work,” Grable says. “Heck, you even dream about work. You never stop.”

Outside, a short downpour of rain has ceased, and a patch of clear sky has opened up above the corner of Hotel and Smith streets. Under the stars, Cruz and Grable head home.

It’s past 11 p.m. when Sean Saiki arrives at Cafe Maru, the karaoke bar on Kapi‘olani Boulevard that he and his partner James Jay Choi opened last year. It boasts a decidedly Asian clientele, and has a genial vibe akin to a Cheers bar scene— except, instead of beers and football, it’s melona soju and K-pop videos. Saiki blends in well with the laidback crowd. His look is relaxed, insouciant even: casual scruff, a cranepatterned shirt, a black In4mation cap. The entrepreneur has an unassuming manner that lends itself to his quiet charm, both of which downplay his frenetic, wildly diverse array of pursuits. Urban apparel company? Check. Karaoke bar? Check. Dance clubs? Check. Seafood boil restaurants? Check.

Friends hint that Saiki possesses a Midas touch when it comes to the success of his endeavors. But he has a more pragmatic answer: hard work. Each morning, Saiki consults his to-do list and scrolls through the text messages that streamed in while he was sleeping: “Ice machine not working,” “Liquor commission came in last night...we got a warning,” or the infamous, “It’s 9am...are you still coming to meet me?” For a businessman known for his nightlife legacy, the party goes round the clock.

The bulk of this day has been spent at the newest Raging Crab location in ‘Aiea, which Saiki owns with another partner, J.C. “Moto” Chow. For Saiki, the title of boss isn’t necessarily glamorous. He pitches in as cook, cleaner, and even errand boy when supplies run low. But Saiki doesn’t balk at this grind, even if it translates to spending 10 hours toiling in a hot kitchen, like earlier today. Growing up on his parents’ Waimānalo plant nursery, manual labor was par for the course. When Cafe Maru first opened, Saiki often tended bar or washed dishes in the back. Tonight, though, operations are running smoothly. Saiki can momentarily relax with a beer. After midnight, Honolulu’s club scene warms up for its weekend ritual of frenzied, uninhibited fun. Saiki strikes out

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Bison spends his days lounging at The Tchin-Tchin! Bar until Cruz takes him home before the dinner rush.

to familiar territory: The District nightclub, his latest nightlife venue created with fellow Element Group partners. It’s a scene to be seen. The District acolytes flock outside the entrance, shooting hopeful glances to the grim-faced bouncers who might grant them swift passage into the inner party sanctum. At the front of the club, Saiki patiently waits for his friends. There’s no boisterous announcement or braggadocio that an established nightlife promoter could employ. Instead, he carries an air of quiet optimism. “I usually wear just a T-shirt,” Saiki says, despite the club’s collared-shirt policy for patrons, “otherwise security sometimes won’t recognize me.”

With slight nods to staff who unhook the velvet ropes, Saiki slips into the club. Inside, the party is loud and orgiastic. The District “Dimes,” the name given to cocktail servers, weave through the masses with sparkling batons and bottle service. Deejay Osna throws down tracks to a lusty, uproarious crowd. This is drunken bacchanal at is finest, wildest hour. And this is the world that Saiki has known and guided intimately for the past 20 years.

It was Saiki’s passion for fast cars that became the starting point for his nightlife career. “My first job was tinting,” he says. “I thought I was going to tint cars for the rest of my life.”

When Saiki and some friends created an apparel brand, Kaizo Speedgear, he started organizing events to promote the line. Turns out, he had a talent for throwing parties. Tapping into that entrepreneurial lodestar, Saiki parlayed those skills into opening his own bars and nightclubs.

The revelry at The District is still at full strength an hour later. If Saiki is working, it’s difficult to tell. He checks in with security, bartenders, and servers in discreet, systematic fashion. From the elevated stage behind the deejay, Saiki surveys the glittering spectacle with what appears a trace of fondness. For him, there is genuine pleasure in seeing people enjoying themselves.

Around 2 a.m., when Ginza, another of Saiki’s clubs, starts heating up, club-goers migrate a few blocks over to its location. He walks over as well, and once inside, seems pleased. Though the popularity of Honolulu nightclubs inevitably rises and falls, the collective euphoria of Ginza’s crowd feels eternal. “I’m addicted to the challenge of making something from nothing into something successful,” Saiki says. That after six years, Ginza is still packing a crowd on Saturday nights is a testimony to Saiki’s skills. “I know everything about this place,” he shares in a rare display of pride. But it’s not the packed crowd he is referring to. It’s the actual physical space. Saiki had an active hand in Ginza’s buildout—from sound and lighting to floor schematics—so whenever problems arise, Saiki doesn’t call a repairman. He’ll try to fix it himself. “He works harder than all of his employees,” says his girlfriend, Kiani Yamamoto, who Saiki met five years ago when she was working at one of his clubs. Saiki says her keen eye for all things “cool and creative”—a trait he claims he is missing—has been key in growing his business endeavors. With his project portfolio ever expanding,

Saiki says he must work harder and smarter. Nowadays, he adds, it’s “less hangovers, and more early meetings.”

Saiki heads back to The District, where the Hot Dog Steve food truck offers vital pre-hangover nourishment to a grateful crowd: bacon-wrapped hotdogs. Hot Dog Steve is actually Saiki’s dad, but Pops is off for the night. It’s about time for Saiki, too, to retire home. Maybe he’ll cruise the Internet to wind down—real estate is a new venture of his, and he likes checking property values online.

After a night of partying, club-goers finally stumble home to sleep. Saiki, too, says his goodbyes to friends. It’s 4 a.m.

A few miles away, in Mānoa Valley, Mike Price is monitoring bread baking in the brick oven. Another day begins.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Sean Saiki arrives to Cafe Maru around 11 p.m. to check on one of his several bars and nightclubs, which also include The District and Ginza. Earlier, he had spent the day working in the kitchen of his newest Raging Crab location in ‘Aiea, shown above.

FLUX FEATURE

The Staff of Life

Big Island Dairy and La Tour Bakehouse compete to produce staple goods and contribute toward creating a market of self-sufficiency in the islands.

IMAGES BY MEGAN SPELMAN & JOHN HOOK

TEXT BY SONNY GANADEN

The reason cows weren’t part of the scenery when Captain Cook first met Hawaiians might be because, like many things, cattle didn’t fit in a canoe. In 1793, British sea captain George Vancouver attempted a clumsy remedy, arriving on Hawai‘i Island with a gift of several longhorn cattle for high chief Kamehameha. They were called pua‘a pepeiaohao, or “pigs with iron ears,” as Hawaiians had never seen horns. The king placed a ban on harming them, and within a few generations, the slopes of Mauna Kea were overrun by herds. Over a century, the culture of the Hawaiian cowboy, or paniolo, emerged on all islands, in addition to a cottage dairy industry. By the 1970s, 100 percent of Hawai‘i’s milk supply came from Hawai‘i cows. A few decades later, that number shrank drastically, and today, in every community besides Hawai‘i Island, merely 20 percent of the milk supply is produced by local cows.

For centuries, milk has served as the sustenance of childhood and the promise of a hopeful future. In fact, milk from cows was integral to the development of civilization, and its availability, along with other staples like grain, became an indicator of wealth. (The ancient Egyptians amassed harvests in grain banks, using the crop as a currency for several millennia.) The notion continues today, when the availability of staple goods such as these often serve as useful, colloquial metrics of one’s standard of living: While gasoline prices fluctuate in relation to powers outside of local control, the price and quality of items like bread and milk speak volumes about the efficiency of local government, the health of the private sector, and quality of life. Nobody asks about the median household income in conversation. If you want a quick metric of the good life, you ask: “How much is a gallon of milk and a loaf of bread?” If you can afford a decent sandwich and a latte for $10, good living is not far off.

Relying on external sources for perishable commodities (interchangeable goods that spoil at an established rate) such as milk means that Hawai‘i is susceptible to the volatility of global trade. We’ve all heard how it could get worse: With an estimated 90 percent of food being imported for 1.4 million residents, the islands have only 10 days of fresh produce and dairy should cargo ships stop arriving. When it comes to food products,

the market, and hence availability, are often confined by economics. The dollar doesn’t go very far in Hawai‘i, which has a cost of living that is 85 percent higher than others; here, nearly half of adult residents live paycheck to paycheck. Still, jobs have been steadily increasing in Hawai‘i for several years, and the jobless rate is at an all-time low. In the 2016 fiscal year, the state had a record-setting $1 billion general treasury cash surplus, primarily because of tourism. But tourism waxes and wanes, and it is through industries that don’t rely on it that Hawai‘i will move toward a more sustainable economic future. Still, not everyone wants to be a dairy farmer or baker, roles with famously odd hours and unique smells. But these are the sorts of jobs that have traditionally provided middle-class wages in first-world nations. In Hawai‘i, an isolated archipelago with a considerably high quality of life, farming and baking are the sorts of commodity-producing careers that have become devalued with the ascendance of a tourism-based economy. For the last several decades, both industries have been dominated by a few local companies that provide stable, well-paying jobs. But by becoming serious contenders in local commodities production, two other Hawai‘ibased companies, Big Island Dairy and La Tour Bakehouse, are expanding the local economy, the affordability of everyday items, and by extension, the purchasing power of local consumers.

COW ISLAND

In 1929, five years after the introduction of mechanical refrigeration to Hawai‘i, C.W. Reynolds, the Industrial Secretary of the United States, created a report to assess the development of dairy across the islands. “Ask the dairymen of Wisconsin or Minnesota what the results would be if they could be given a succession of twelve months like June,” Reynolds wrote of Hawai‘i’s picturesque climate. “Give Hawaii knowledge of dairying held by these two states and anticipate the answer.” The secretary was under the impression that Hawai‘i could experience massive yields in its expanding dairy industry. The retail cost of a quart of milk was 30 cents, delivered to your home or office in a milk bottle, capped with a paper cap, what locals called a “pog.” The

If you can afford a decent sandwich and a latte for $10, good living is not far off.

Big Island Dairy, whose general manager, Brad Duff, is shown above, is helping to expand the local economy.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 47

industrial secretary advocated for 20-year leases to allow for the development of long-term irrigation plans for dairies, and referenced developing creameries in New Zealand and Japan, which had similar populaces that were becoming accustomed to dairy products. By the writing of the report, the territory had mandated that milk be served with public school meals, creating a built-in demand for the product.

By the 1960s, dozens of farms across the islands produced all the milk consumed locally. Farmers fed their cattle the dried stems and stumps of pineapple and dietary fiber from sugar industry byproduct. As a result of disagreements between processors like Meadow Gold and small family farms, called the “Milk Wars,” the state passed a law in 1967 that dictated the price at which milk is purchased from farmers, but not the price at which it is sold to consumers. Cattle husbandry, in the dairy industry and in paniolo contests, had become ingrained in local culture. In 1976, the winner of the national hand-milking contest, held annually in Sacramento, California, was a local guy, Mr. Walter Carlos, who pulled an impressive 13.6 lbs. of milk in a single sitting.

Around the same time, the cost of land and feed was becoming burdensome to local dairy farmers, who begun to rely on mainland corn and grain. Meanwhile, the cost of freight from the U.S. mainland had decreased dramatically, and the speed of ships had increased. Hawai‘i began importing milk in 1985, and not long after, dozens of dairies across the islands were shuttered. In 2004, when Foremost Dairy closed, Meadow Gold—originally Dairymen’s Association, Ltd., a cooperative of a few family farms across O‘ahu—became the only pasteurization and distribution facility in Hawai‘i, with one site in urban Honolulu, and the other near the airport in Hilo on Hawai‘i Island.

Today, a gallon of local milk can cost nearly $8, which is more than double the average price of milk in other U.S. states. Prices are dictated by an iniquitous alliance of factors: the state-regulated purchase price, the lack of dairy farms on the islands, and the vagaries of the market across the sea. As a result of the federal Jones Act, vessels that transport cargo or passengers between two U.S. ports must be built, crewed, and owned by Americans, meaning that refrigerated containers making a beeline from California to Hawai‘i with perishable milk are operating without international competition. And when feed or fuel costs increase for Northern California dairies, where Meadow Gold purchases most of its “pool” of milk, which includes milk from local farms, so too does the price of milk.

Nearly an hour’s drive up the coast from Hilo is the 2,500acre Big Island Dairy in ‘Ō‘ōkala, the largest local dairy in present production, and one of the last two large-scale milk producers in the state. Father-son owners Steven and Derek

For years, Meadow Gold has been the only pasteurization facility in the state, but Big Island Dairy, pictured, hopes to become a rival with the completion of its own facility.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Whitesides, who also own a 6,400-cow dairy in Idaho, purchased the dairy in 2012 in hopes of modernizing the operation and increasing Hawai‘i’s local supply. Seen through a window in the dairy’s administrative office is the milking parlor, where cows queue themselves into respective metal holders while a worker brushes iodine onto their teats, then gently applies a milking machine, which detaches itself like something out of a science fiction film when its pressure monitor senses that the cow is done for the session. “It’s a double parallel rapid release parlor, ready for the 21st century,” says Brad Duff, the dairy’s general manager, who is from Iowa. “The goal is to make these cows as comfortable as possible, which an experienced dairyman can tell by the sheen of their coats, by the affect of their demeanor. Most of these cows are milked three times a day, and we ship 24,000 gallons a week.” Big Island Dairy has room to grow to its allowed 2,000 cows, but presently it milks only 1,200—a tenth of the size of the mega milking operations throughout the American western states, which have an economy of scale that allows them to cut costs.

The environmental results of massive agribusiness, particularly cattle, are becoming known. A smaller number of cows means a smaller carbon footprint, but it also means a lower sale price. In other economic sectors, this could mean that a local producer is cut out of the market. But milk, like bread, is a perishable commodity, and the shorter the period between cow and consumer, the more viable the product. All of Big Island Dairy’s 4 million gallons produced each year go to a single plant for processing: Meadow Gold, which still handles pasteurization and distribution from its facilities in Hilo and Honolulu. This means that 80 percent of the milk sold on Hawai‘i Island is truly local, having been milked from cows on island, pasteurized and packaged there, and then distributed to several island grocery store chains, including Costco. To compete with the milk coming from California, Big Island Dairy must be obsessive about its cows. “Some healthy, recently calved

cows produce as much as 120 pounds of milk per day,” Duff says. “Though the goal is about 80 pounds per head.”

Per federal and state regulations, the lives of dairy cows are highly regulated. Everything else is determined by the market. “If the market dictated that we needed to produce organic milk, we’d do it,” Duff says, explaining that organic milk means that cows eat only organic feed. “As is, people aren’t willing to pay upwards of $16 a gallon.” To offset the cost of feed, Big Island Dairy attempts to grow much of its own. Over 350 acres are dedicated to corn, which ferments in a large, cylindrical plastic bag 3 meters high and is later mixed with a variety of other imported feed. The lot fronting the dairy’s administration building is abuzz with the construction of a new pasteurization facility. Once it ʼ s completed, Big Island Dairy hopes to become a rival to Meadow Gold, which may lead to lower costs for consumers.

On the day I visit the dairy, flocks gather where the feed is stored in a setup that resembles a series of handball courts filled with grain, a version of bird heaven. In the barn, a metal skidsteer continually sweeps the length of the pen, pushing fresh droppings through grates. “They eat, they drink, they give milk, they poop; these are the certainties of a cow,” Duff says. It’s a wonder of modern farming that milk survives rigorous testing from a variety of federal, state, and independent agencies, which mandate that entire silos of milk be dumped if a test shows contamination.

The fight over the smell of wafting manure, as well as the risk of contaminated runoff, is being played out on the south shore of Kaua‘i, where another local dairy is attempting to open. In the post-sugar era, the state invested in tourism to replace a century of an agricultural economy, which included the dairy industry. The gorgeous and historic southern shore of Kaua‘i, like South Maui and the coast of Kailua-Kona on Hawai‘i Island, became an exclusive visitor zone, with world-class golf courses dotting its coastline. Here, in 2013, Hawai‘i’s richest resident, Pierre Omidyar, the founder

of eBay whose network of investments constitute a significant bloc of nongovernmental organizations, purchased 557 acres in Maha‘ulepu Valley in hopes of building a dairy through his organization Ulupono Initiative. According to Ulupono Initiative, the dairy could produce 1.2 million gallons of milk per year, using a sustainable, pasture-based system. The proposed development has its detractors, however, and has been challenged in court on two separate occasions, first by Kawailoa Development, which owns the Grand Hyatt Kauai Resort and Spa, in 2014, and then by a group called Friends of Maha‘ulepu in 2015. Kawailoa’s award-winning Poipu Bay Golf Course, built on former agriculture land after a protracted battle in state courts, is directly downwind of the proposed dairy. From the perspective of residents who want fresh, affordable milk products, it remains debatable whether a golf course is better for the community than a pool of manure.

A BAKERY IN THE SKY

Once it is milled, grain—the foundation of any good bread—can be stored for months. “There’s a reason bread created civilization,” Trung Lam says from the 60,000-square-foot La Tour Bakehouse located on the second floor of the La Tour Plaza on Nimitz Highway. Much like the missionaries who settled in the islands who found themselves without that familiar taste of home, Trung’s father, Thanh Lam, an immigrant from Vietnam who arrived to Hawai‘i in 1984, was dismayed by the lack of fresh bread available for his Vietnamese grab-andgo sandwich shop Ba-Le, which he had opened in Chinatown, Honolulu with his wife and business partner, Le Vo. More than 130 years prior, another immigrant baker to Hawai‘i, a Scotsman named Robert Love, found himself in the Kingdom of Hawai‘i. By the time Love opened his bakery in 1853, there was money to be made baking the hardtack that was eaten aboard whaling ships. The Love family expanded the business over decades, and went on

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 51

to dominate the wholesale baking industry across the islands, offering hundreds of wellpaid jobs to residents. Today, as the state’s largest supplier of freshly baked breads, Love’s continues delivering everything from sliced bread to Hostess cupcakes across O‘ahu and to neighbor islands via tightly scheduled air transport, while frozen, thawed, and sometimes re-baked bread appears in fast food restaurants and grocery aisles.

“I want to be like Love’s,” Thanh Lam told Honolulu food critic John Heckathorn in 1986, two years after opening Ba-Le. To meet their sandwich ingredient needs, Thanh, whose sons Trung and Brandon were 5 and 3, respectively, at the time, had begun baking baguettes in the back of the shop, creating a freshness that added to the popularity of Ba-Le’s bánh mi, a sandwich that fuses French bread with the Vietnamese flavors of fresh cilantro and do chua (pickled daikon and carrots). The bread became locally famous, and orders for the baguettes began spilling in from other restaurants. By the time Trung and Brandon were in their 20s, there were 24 Ba-Le shops operating across O‘ahu, run by members of the Lam family or workers promoted from within.

In 1996, to keep up with orders, Thanh built a bakery near the O‘ahu Community Correctional Facility on Dillingham Boulevard. Fifteen years later, with Trung, Brandon, and local baker and pastry chef Rodney Weddle, Thanh expanded again, this time on the site on Nimitz Highway, where Dole Pineapple once packaged its pineapple products for global distribution. He renamed the building La Tour Plaza, and installed a massive bakery on the second floor that he called La Tour Bakehouse to reflect a turn toward artisanal breads. On the first floor, co-owners and lessees opened a variety of businesses, and the Lams opened La Tour Café, a casual, European-style spot serving bread fresh out of the ovens upstairs. The Bakehouse employs 140 people and runs its bakery around the clock, supplying artisanal bread or dough to hotels, supermarkets, and restaurants across the state. It also stocks the 19 Ba-Le restaurants and three La Tour Café locations across the island.

“Everything about operating in Hawai‘i is expensive,” says Trung, who can reasonably be described as the company’s chief operations officer. “We can save money through automation, and through smart

business practices.” They do so with massive 21st century ovens and calibrated machines that knead and cut dough precisely, so as to allow dough to rise or fall according to specific recipes. To compete in a market that literally feeds Hawai‘i, La Tour Bakehouse has had to learn the lessons of innovation and cost-reduction quickly, which, in turn, benefits the consumer.

The ubiquity of daily bread has meant that for centuries, bakeries, and bakers themselves, are the heartbeat of community. Bread is much more than the staff of life; it is the host of the spirit, and what is metaphorically broken during a peace treaty. La Tour Bakehouse is built on a global truism: that freshly baked bread is life-sustaining and delicious; and day-old bread is stale and inferior. Everyone from the day laborer to the company boss can afford something fresh off the bakery menu. Baking is a job that requires good spirits, good shoes, and in return, should deliver a livable wage—historically, in Hawai‘i and around the world, it has. The islands’ reliance on frozen bread and imported milk roughly tracked the reliance on a servicebased tourism economy, which, while capricious, is currently booming. But in order for the islands to be self-sufficient in the 21st century, there must exist opportunities for employment in commodities production, as well as in the service industry.

The American Dream was never the sole property of Americans, but of the vast majority of humanity. Whatever it is, the Lams have achieved it. Gallons of milk and loaves of bread—these are the daily items that make up the moments of our lives across the economic spectrum. Whether these products come from our community, and how much we pay for them, matters.

Residents in the islands are often reminded of the issue of food security when purchasing groceries, or lunch. A few weeks after my visit to the dairy, I attempt to get an affordable, all-local lunch for under $10 at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa. At Ba-Le, I order a $5 veggie bánh mi, which is made with bread I know was baked hours previous in the dark of night, and then stuffed with vegetables sourced from local farmers. A short walk away, I order a latte made with coffee beans grown on Hawai‘i Island, pricier than the house blend, for $4. Holding up the line, I pester the cashier to find out where the milk comes from.

In order for Hawai‘i to be self-sufficient in the 21st century, there must exist opportunities for employment in commodities production.

La Tour Bakehouse, which was founded by the father of Trung Lam, shown above, employs 140 people and runs its bakery around the clock, providing freshly baked artisanal bread to consumers across O‘ahu.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 53

The Living Projects