The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme:

Volume � Issue � Features: An Island Reborn A Hawaiian island recovers from decades of bombing, a botanist climbs clifs to save rare plants, and social media infuencers question their reaches. Living Well: Sacred Design Get interior design tips from The Vanguard Theory’s Michelle Jaime, and learn the story behind architect Ossipof’s most sacred structure. Explore: Sydney’s Suburbs Find diversity in Sydney, spirituality in a sweat lodge, and understanding of contested lands. 0 71658 25489 02 > 3 USD $14 95 AUD $19 95

Sacred Spaces

WAIKIKI ALA MOANA CENTER 800.550.0005 AVAILABLE AT CHANEL.COM ©2017 CHANEL ® , Inc. B ®

THE BEST ADVENTURES YIELD FRESH PERSPECTIVES. Miguel Rodriguez hails from Vancouver Island, British Columbia where he’s built a life tied closely to the ocean. On Kaua‘i, where the rhythms of the sea define each day, he found his own perch to take it all in. Waimea, Kaua‘i – Hawai‘i

ALOHA ® OLUKAI.COM/ANYWHEREALOHA

ANYWHERE

HIAPO in Rum / Dark Java

SACRED SPACES

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

FLUX PHILES

22 | Art: Kaori Ukaji

28 | Culture: Steve erlman

A HUI HOU

192 | Tombstone Tourism

FEATURES

38 | The Refrain n his series The Leaping Place, Matt Shallenberger refects on layers of time and identity in awai i.

50 | Reviving Kanaloa Matthew e neef volunteers on a awaiian island decimated by decades of bombardment.

64 | Curb Your Exposure eau Flemister e amines the impact of social media on physical places, sacred and unseen.

78 | In the Light e a Gleason pro les awai i sland residents who feel the callings of crystals.

TABLE

| F T S 20

OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| S T O S

EXPLORE

90 | Moloka‘i alaupapa’s Ghosts

98 | O‘ahu Sweat odge eremony

104 | Hawai‘i Island Ofshore on Mauna ea

112 | Sydney eyond the each

124 | Family rvo caf ’s i ie ose

132 | Interior Design Vanguard Theory’s Michelle Jaime

140 | Religion Ossipof’s Thurston hapel

88

122

LIVING WELL

150 SPECIAL SECTION: THE FLUX SHOP

by

154 | Menswear eyn Spooner eather Soul 158 | Menswear Salvage ublic 162 | Womenswear Matt ruening 164 | Footwear sland Slipper 166 | Accessories Jana am 168 | Stationery Miemi o o. 170 | Footwear Olu ai 172 | Art Steven ean 176 | Apparel V pparel TABLE OF CONTENTS | S T O S

Presented

Hawai‘i Tourism Oceania

Presenting Programming Sponsor: Creative Industries Division

180 | Accessories

178 | Art eachca e

178 | Apparel

Jams orld

Martin Mac rthur

180 | Food onolulu oo ie ompany

181 | Skincare awaiian ath and ody

182 | Event Recap F otanical runch

184 | Food

James pta in

ONLINE

Poisoning a Pacific City onolulu, ewel of the world, rst among equals in the cities of the aci c, is facing an e istential threat. Since , it s estimated that , gallons of petroleum products, including machine oil, marine diesel, and et fuel have soa ed into the earth in a hill above its water supply, in service of the .S. military. Though tests indicate the water supply is presently safe, Sonny Ganaden investigates how the poisoning of onolulu may only be a matter of time. llustration by J Feducia.

Read the full story online at features.fluxhawaii.com.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | S T O S

182 IN FLUX

hef

S S S

“What do people gain from all their labors at which they toil under the sun?

Generations come and generations go, but the earth remains forever.

The sun rises and the sun sets, and hurries back to where it rises.

The wind blows to the south and turns to the north; round and round it goes, ever returning on its course.

All streams flow into the sea, yet the sea is never full. …

The eye never has enough of seeing, nor the ear its fill of hearing. …

I have seen all the things that are done under the sun; all of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind.”

- ECCLESIASTES 1 : 1-8 , 14

couple years after launching the rst issue of F in , my father, an avid supporter of my new business endeavor, as ed me a devastating question f F went belly up tomorrow, would anyone care struggled with an answer, unsure how to respond when faced with the possible demise of what had become an e tension of myself. Then, more pointedly, he said Odds are F will fail. suc ed in my lip, trying to eep tears from spilling. hat was the point of it all, then as it all meaningless, a futile chasing after the wind had gone into ournalism because loved telling stories. started F because wanted to change the world with my writing. n the intervening years, life became an e hausting race to eep up. blin ed, and the world did indeed change. ew technology altered actions and long held beliefs. The world grew increasingly flat.

Today, information shoots across the stratosphere in a fren ied pace. Men are murdered in the streets. Mountains are poc mar ed by eager travelers. Missiles are paraded, bombs are dropped. This food of information has produced citi ens that are more aware than ever. nd yet, we respond with a TF, then shrug and go about our day.

arlier this year, in March, the ew or Times ran a piece by ells Tower titled The awaii ure. t was about the writer’s first trip to the island, in a desperate attempt to escape the news. Tower made some missteps, calling the most awaiian thing about a commercial luau its proficiency at e tracting tourists’ dollars.

eedless to say, people everywhere with love for the islands were miffed.

owever, for all of Tower’s crass ruminations, can’t blame him for wanting to escape his world and set foot into ours. is simplistic character tropes and hope for a paradisiacal den these have all been parts of the selling of Hawai‘i since aviation innovation enabled mass travel here decades ago. et Tower stumbled upon a bit of magic, too. The magic has to do with the moon, the thud and rustle of the surf, he writes. The magic is wor ing on Jed, my year old son. e is trying to seduce a girl of or so. She is engrossed with her tablet. cultist of the night s y, Jed touches her wrist, points overhead and says, Stars.’ The girl’s eyes do not flic er from her screen. There is something to be learned from Tower’s son. e has not yet been drawn to consume life online, to frivolously trample revered sites in order to attain the perfect posts or promote commercial endeavors. e has not yet been e posed to the flippant dissemination of information that threatens to undermine what have wor ed so hard to create media that see s not only to create more informed citi ens, but to better the world in which we live. nstead, he still can simply en oy the stars. t has ta en me five years to come to terms with my father’s statement, to be O with the fact that what hold sacred may be ta en from me. ecogni ing this, we continue to adapt and evolve F in today’s changing media landscape, incorporating new sections that celebrate the good things in life and prompt dialogue about cultures around the world. ather than focus in on the clamoring around me, loo up, marveling at the stars.

With aloha, isa amada Son TO lisa nellamediagroup.com

EDITOR’S LETTER |

14 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Take me to NYC. Shows, art, shopping, cronuts? There are two types of cards: the Visa Signature ® card and the Platinum Plus ® card. The card you receive will be determined by several factors including your income and credit history. The benefts and bonus miles above apply to Visa Signature® cards only. The Annual Fees, benefts and bonus miles for Platinum Plus® cards are diferent. For more information on the diferences, see the Features section accompanying the application. The Visa Signature card benefits described herein are subject to certain restrictions, limitations and exclusions. For more information about rates, fees, other costs and benefits of this credit card, or to apply, visit AlaskaAir.com or refer to the disclosures accompanying the application. This credit card program is issued and administered by Bank of America, N.A. Visa and Visa Signature are registered trademarks of Visa International Service Association and are used by the issuer pursuant to license from Visa U.S.A., Inc. Platinum Plus is a registered trademark of Bank of America Corporation. ©2017 Bank of America Corporation. Alaska’s Famous Companion Fare™ Offer -30,000 Bonus Mile Ofer -First Checked Bag Free -3x Miles on eligible Alaska and Virgin America Purchases

MASTHEAD

“Journals, because they form a passage between my internal and external self.”

PUBLISHER

Jason utinella

EDITOR isa amada Son

CREATIVE DIRECTOR ra Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNER

Michelle Gane u

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John oo

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha oo

COPY EDITOR

ndy eth Miller

EDITOR - AT - LARGE

Sonny Ganaden

IMAGES

J Feducia

sh Gowan

Jef awe

ryce Johnson

Lila Lee

ayne evin

Franco Salmoiraghi

Matt Shallenberger

“Being connected to a universal consciousness, because it allows for an encompassing and empathetic understanding of existence.”

hat is sacred to you

CONTRIBUTORS

Matthew e neef

unica scalante

eau Flemister

Le‘a Gleason

Tina Grandinetti

Travis Hancock

Jef awe

rittany yte

aycee Macaraeg

Timothy . Schuler

Matt Shallenberger ae So ot

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVic ar

ADVERTISING

Mi e iley

GROUP PUBLISHER mi e nellamediagroup.com

helsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

than est MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

OPERATIONS

Joe V. oc

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER oe nellamediagroup.com

Gary ayne VP BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT gpayne nellamediagroup.com

Mitchell Fong DESIGNER

Aja Toscano DIGITAL CONTENT COORDINATOR

INTERNS

unica scalante

Gabe Estevez

General nquiries contact flu hawaii.com

by ella Media Group, . ontents of F awaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the e pressed written consent of the publisher. F awaii accepts no responsibility for unsolicited manuscripts and or photographs and assumes no liability for products or services advertised

PUBLISHED BY: ella Media Group .O. o onolulu,

“Language. Being able to share a language, along with all the customs tied to it, is a phenomenon that makes us human.”

herein. F awaii reserves the right to edit, rewrite, refuse or reuse material, is not responsible for errors and omissions and may feature same on fu hawaii.com, as well as other mediums for any and all purposes.

F awaii is a triannual lifestyle publication.

| S S S

Find out how Hawai’i Life is changing the way that people do real estate in Hawai’i—simpler, smarter, with heart. 800-667-5028 HawaiiLife.com You’ll love our step-by-step Transaction Management process. It makes selling or buying as easy as 1-2-3.

Daniel Semisi, Transaction Coordinator, Oahu

On the Cover

On the cover is an image by Tara oc , the woman behind the popular surf fashion blog adyslider, who we interviewed on page for urb our posure, a story on social media’s impact on place. n a poignant call to creatives in a blog post titled, Sacred laces, she questioned the way the social community herself included portrays and uses awai i in its wor or play. hen a company emails you asking to work on a campaign it is easy to compromise the people and places around you, she wrote online. ’m guilty of this. will shoot a lifestyle campaign at the e pense of a photogenic location. f we’re to be good stewards of the land in awai i where resources are in fact limited then we should probably eep in mind what a photo connected to thousands of followers could do to a place.

Brittany Lyte

rittany yte has reported from ussia, oland, and across the nited States, interviewing sub ects ranging from the alai ama to Ghostface illah of the u Tang lan. er writing has covered a similarly wide range of topics, from ative awaiian sovereignty movements to undocumented to ic waste buried in onnecticut, the latter investigation inspiring a state law change. For this issue of F , she pro led an e ploratory botanist on aua i trying to save rare endemic plants from e tinction, and a reporter telling the story of indigenous groups rallying to preserve areas culturally and spiritually signi cant. ach of us, regardless of whether we are spiritual or if we adhere to a religion, hold something sacred, she says. place, a relationship, a ritual whatever it is that ma es us feel humble and awa e in its presence is what consider sacred.

Franco Salmoiraghi

Franco Salmoiraghi has documented important moments, daily life, and disappearing sights in awai i for more than ve decades. n the mid s, and for the ne t three decades, when ative Hawaiian activists arrived on the shores of aho olawe in an efort to halt target bombings conducted by the .S. military, Salmoiraghi’s star , blac and white images memoriali ed the landings on and desolation of the isle. These images are reprinted here for eviving analoa on page . i e his documentary wor , which records important occasions in awai i’s history, his landscape images honor sacred sites, some of which no longer e ist today, li e the spring fed ueen’s ath in the awai i sland area of alapana, the historic shing village that was engulfed in lava from lauea Volcano. The wor ’ve done the years photographing aho olawe, the years of awai i’s sugar industry, or my travel e periences all of it, it’s priceless, the year old says. got to see so many things that were virtually inaccessible, and I consider it a gift.

Matt Shallenberger

f there is something of the idea of sacredness being lost today, thin it is, in part, a move away from small, personal relationships less time spent alone, more time trying to do two things at once, says ailua born, large format landscape photographer Matt Shallenberger, who dove deep into his family heritage and the umulipo for his series of photographs The Leaping Place, which captures the vastness of Hawai‘i Island on page . thin it’s important to protect the things that allow us to build sacredness in the rst place attention, quiet, solitude. hope people nd some of that in my photographs, or inspiration to go nd it for themselves. ow residing in ltadena, alifornia, where his wife recently gave birth to their rst child, Shallenberger focuses his present wor on contemporary relationships to fol lore and mythology.

18 | FLUXHAWAII.COM CONTRIBUTORS | S S S

Petroglyph at Pu‘u Moa‘ulanui on Kaho‘olawe. Image by Wayne Levin.

Petroglyph at Pu‘u Moa‘ulanui on Kaho‘olawe. Image by Wayne Levin.

SACRED SPACES

“Slowly, and without any fanfare these jewels of creation have slipped into oblivion nevermore to grace our world.” —Steve Perlman

Body Language

Artist Kaori Ukaji incorporates the most personal objects and internal inspirations into her work.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

aori a i’s home is an e ercise in eclectic, artistic delight. colorful woven rug is splayed across the floor, and a merry assortment of tchotch es invites inspection. aintings, s etches, and photographs te ture the space with a well worn cheeriness, while a spherical, metal wire ovum nearly feet in diameter, created by Stephen ang, a i’s husband and fellow artist, hangs over the seating area. cross the room, a glass ar featuring stratums of wooly material also begs inquiry t is fur collected from mi, the couple’s dog. earby, a low lying apothecary dresser showcases nearly miniature compartments, each retrofitted with a brightly patterned enamel nob. eatly penned labels designate the contents within Sandpaper. Sunbloc . hal . Two drawers, one atop the other, offer more cryptic labeling Things. Things Spill. a i chuc les before offering a lighthearted yet similarly oblique e planation. ou have things and then sometimes those things spill over. ntentionally or not, a i refrains from divulging the drawers’ treasures. awai i sland based artist, a i is both private and pleasant. Originally from Japan, she describes having a quiet and responsible childhood, when a daily routine of school, piano lessons, and afternoons spent drawing and crafting paper dolls offered sweet contentment. She was especially fond of tracing paper, with its sil y, onion s in sheets, and the dot matri printer paper with its accordion li e continuity that her grandmother brought home in reams from her government ob. Such inclination toward paper’s tactility and form would emerge as a leitmotif in a i’s art years later. y high school, a i’s affinity for art had sharpened to a focus. ewing to her father’s pragmatic advice of getting a s ill in hand, she listed designer as her chosen career path in her high school yearboo . pon graduating from college as a

At her Hawai‘i Island studio, Kaori Ukaji mines her inner being and her body for inspiration, often incorporating her own skin, hair, and even earwax into her work.

FLUX PHILES | TS 22 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

trained graphic designer, a i settled into the professional world as an artist in To yo. ut at age , a i felt an unmista able urge to fly on. eaving Japan and her position as a research associate in Musashino rt niversity’s graphic design department, she embar ed upon a year of travel. The ourney was summarily cut short. lthough had never been here before, somehow, arriving in ilo made me feel that came bac , a i recalls of landing in awai i. My feeling here was so deep, could not leave. mysterious power compelled her to stay, and over the ne t years, a i’s art came to reflect her enigmatic interior, echoing the ever changing susurrations of self.

f a i’s art is a barometer of her internal state, her ear serves as the bridge to that inner sanctum. To a i, the ear is most sacred. go almost into a trance, a i says of the rhapsodic feelings that surface when she gently touches the sensitive areas of her inner ear with a

slender pic . itual e ploration of her ear allows her to tap into a sensual, mystical e istence. This is her mandala, a glimpse into the entirety of her being and the inner ecstasy that resonates there. rawing on that energy, a i then translates it into her art.

For years, a i’s pieces focused on graphite, paper, the color blac , and straight lines symbolic representations of the tightness and strength she felt within. ut as years passed, her inner world softened, and so, too, did the lines of her art. n the early s, a een interest in other materials rose to include her own s in, hair, and ear wa . i e the e ploration of her ear, canvassing her body became a daily ritual for a i, and she felt no hesitation in subsequently using the s in and hair she collected in her art. For a i, it was a statement both pragmatic and profound sing elements of her body in her art was a natural e tension of herself. round that time, a i also found

“Always my feeling is my art, always myself is my art. It is like a river flowing someplace without my decision,” says Japan-born Ukaji, who speaks of her art as an embodiment of self.

24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 25

herself pulled to another powerful color red. lac is me, but red is me, too, a i says. hen she married ang years ago, a i became drawn to true red today she describes the color as having evolved to a red orange hue, li e blood e posed to air.

This red orange hue was present in Serenely Proliferating , a i’s installation for Artists of Hawai‘i 2017 at the onolulu Museum of rt. She fell into a meditative state during its construction, as she had with pieces in the past, prompted by deep concentration and the repetitive movement of her hands. She imagined the artwor s as a metaphysical ourney through her body, to be intrinsically felt as much as seen. t’s li e something slowly spreading, a i e plains of the feminine mystique a concept of womanhood she is e ploring that is emerging from the art. rimson is diffused among lush, cylindrical folds of white bath tissue. arge, hanging embroidered canvases, their fronts and bac s e posed, display the delicate recursive stitching of thousands upon

thousands of thread loops. Two wor s, created with s in she peeled from calluses on her feet and then dyed a rich orange red, are e quisite, organic interplays of matter and interstice. For a i, each piece in Serenely Proliferating is a rapturous hymn to her body. only ma e pieces of what am now, she says. ac at home, the apothecary dresser silently holds its cache of treasures. Sewing. Graphite. Glue. The contents of Things and Things Spill remain wondrous and unrevealed. Sitting near the dresser, a i spea s of her art as an embodiment of self, a suffusion of her ever evolving identity. lways my feeling is my art, always myself is my art, she says. a i has discovered a new energy that may soon be influencing her wor t is li e a river flowing someplace without my decision, she says of the quietly e panding feelings and changes occurring within her. They swell up and in and around, waiting, perhaps, to spill over.

Ukaji’s installation for Artists of Hawai‘i 2017 at the Honolulu Museum of Art, Serenely Proliferating , presented her artworks as a metaphysical journey through her body.

For more information, visit kaoriukaji.com.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Let the Earth Sprout

Exploratory botanist Steve Perlman descends Hawai‘i’s cliff faces to save plants on the verge of extinction.

TEXT BY BRITTANY LYTE

IMAGES BY BRYCE JOHNSON

S teve erlman punches the spi es of his hi ing boots into the face of a vertical cliff. Spread beneath him is alalau Valley, a dramatic landscape spectacularly wrin led by wind, water, vo lcanic lava, and the spines of soaring pea s. idden within this million year old topography are wild plants that e ist nowhere else on earth.

erlman is roped to the trun of an old hi a lehua tree that’s rooted on the valley rim. is body dangles parallel to the valley floor , feet below. Twisting his suntanned nec , erlman drops his ga e into alalau’s impossibly beautiful bowl, scanning the cliffside for the fragile botanical treasures it holds.

awai i’s endemic plants arrived in the islands millions of years ago as seeds, mostly transported by wind or ocean currents, or in the gut of a migrating bird. From these single seeds evolved a much larger collection of species now nown as awai i’s native flora. ubbed the endangered species capital of the world, awai i is home to hundreds of varieties of threatened plants and animals. ll told, of the state’s , native plant species have already gone e tinct.

liffs are the last frontier for many of these endangered plants due to their sheer inaccessibility. fortress of weathered basalt, preserved by e treme isolation and agged terrain, the alalau sea cliffs are one of the richest remaining refuges for the state’s rare botanicals. redators who indiscriminately eat greens, endangered or not, can’t easily access the steep slopes. Minimal hoof traffic also means less erosion and fewer chances for the invasive weeds that tend to smother out natives to arrive and ta e root.

ut such paradises of biodiversity are still under attac from plant disease, e treme weather, and nimble goats whose teeth threaten to chew out whole species. The loss of even ust one of the delicate plant varieties ensconced in the folds of the alalau cliffs could hamper the natural world’s resiliency and hinder its ability to provide food, climate stabili ation, and shelter. lso at ris of being lost are any untapped medicinal powers these plants might possess. nd so, it is erlman’s ob to get there first.

escending into the alalau gorge, erlman finesses his way around a precarious rotting log. e avoids entanglement with a warped tree protruding from the fluted roc , but endures a battering by weeds armed with ra or sharp thorns growing in nee high clumps. e seems not to notice the shallow slices now scarring his arms. e is headed to a grouping of eight shrub li e plants, which he has been chec ing on for years. t the age of , erlman has been an e ploratory botanist for decades. former hobbyist roc climber, erlman moved to awai i from olorado in the s to wor with plants in one of the few places in the nited States where the age of botanical discovery remains far from over.

Exploratory botanist

Steve Perlman pioneered the practice of rappelling cliffs in order to save rare plants from extinction.

FLUX PHILES | T 28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

oupling his love of bouldering and e treme hi ing with the allure of awai i’s unwonted greenery, erlman pioneered the practice of rappelling cliffs in order to scour for plants in previously uncharted terrain. is ob ective then was the same as it is now iscover and, ultimately, save rare plants from e tinction.

n awai i and across the South acific, erlman’s use of ropes to traverse waterfalls and scale brea nec bluffs has led to the discovery of more than species, including yanea ole oleensis, a vulnerable flowering plant in the lobelioid bellflower family all of which are endemic to this island chain that is found on aua i’s Mount apalaoa. e also led the rediscovery of many plants once thought to be e tinct. There are species that evolved on cliffs and no one had really sampled them, erlman says. Today, he is employed by the awai i epartment of and and atural esource’s lant tinction revention rogram, or , which was established in to save the native species left in the state that each had fewer than plants remaining in the

wild. s botanists have gained a greater understanding of the plant diversity on cliffs and in other hard to reach places, do ens of plants have been added to the list. Only a few species have become strong enough to warrant removal from the program’s guardianship.

hile plant conservation groups typically focus on regenerating endangered species in botanical gardens, targets those that still e ist in nature. Guam and uerto ico now have plant conservation programs modeled after awai i’s. Four days each wee , erlman hi es and rappels to remote sites, where he collects wild seed for propagation or out plants nursery grown species to establish new populations. Some of these sites can only be reached this way, or by helicopter.

Two hundred feet below the alalau ridgeline, erlman arrives, elbows bloodied, at the site of the largest nown cluster of the anomola variety of lantago princeps in the wild. i e a little tree, the lantago, which is a rare flowering species in the plantain family and endemic to awai i, has a rosette of green leaves

In Hawai‘i and across the South Pacific, Perlman’s use of ropes to traverse waterfalls and scale breakneck bluffs has led to the discovery of more than 50 plant species.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

attached to a long, woody stem. There are eight of the anomola variety on the cliff. There are two additional sites on aua i with smaller clusters of it. ll told, only of these particular plants e ist in the wild.

f it’s a polar bear or a panda, something that’s really cute, people want to save it, erlman says as he collects seed from a spi y, flowering lantago stamen. hen it comes to plant species, often people don’t really care. Some people thin that as long as it’s still green out here, and there are guavas for the pigs to eat, then it’s no problem. ut if we lose them, they’ll be gone forever.

Of the eight lantago plants on the alalau cliff face, three are in flower and one is bearing mature fruit. t is the latter that erlman collects seeds from, noting the status of the others in his poc et field boo . e tuc s the seeds into a pouch on the bac of his vest. e will ta e them bac to the ational Tropical otanical

Garden, where they will be planted and nurtured. ith any luc , the seeds will produce offspring that can be introduced to the wild. n a few wee s, erlman will return to the site to collect more mature fruit.

hen this lantago princeps was rst discovered on the alalau clif face by erlman’s longtime partner, en ood, in the early s, it was nearly double the number of plants. Over time, goats chewed up almost half of the original population. dditional ha ards have come in the form of loss of pollinators and e treme wind. urricanes wa and ni i, for e ample, blew hundreds of e tinction prone species of the alalau clifs. more sinister threat to these species is the blac mar et for rare plants. fforts by botanists li e erlman to eep secret the location of awai i’s most vulnerable plants are reactions to the small but destructive number of thieves who don headlamps and embar on night hi es to find and

uproot plants that are as scarce as they are precious. single seed from an endangered palm, shrub, or flower can yield as much as times the price of heartier species when sold. ecause of this threat, there are some plants of which only erlman nows the location. ut it’s not clear how much longer he will be able to protect them since the current fiscal climate for environmental programs li e are blea . ast fiscal year, was only able to raise percent of its million budget, with percent of funds coming from federal monies. The program’s budget is poised for another percent reduction in the upcoming fiscal year, which would effectively reduce the current program by half. hopes to bolster its funding with help from private sources, including members of the public who understand how much there is to lose.

Meanwhile, fresh threats, such as new slug species, are surfacing.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 33 Our website gives you accurate, real-time information and powerful search tools from Hawaii’s neighborhood expert. Whether you’re buying, selling or just looking around, do it faster and better at LocationsHawaii.com. Real estate is a race. Consider us your head start. (808) 377-4648 • LocationsHawaii.com RB-17095

botanist may spend years encouraging a plant to thrive, only to suddenly lose it to an une pected pest, or to the mouth of a hungry goat. erlman estimates that he’s watched a couple do en plants go e tinct during his four decades of wor . t can be hard not to feel defeated, he admits. There are people who have become depressed about this, people who actually have to ta e medication, li e ro ac, erlman says. ou go out there to a plant you’ve been collecting seed from for years you’ve been monitoring it for years, it’s li e a member of your family and it dies. t’s sad. t’s really tragic. t’s li e wor ing in hospice for plants.

For years, erlman cared for a righamia insignis nown as awaiian palm, lulu, or colloquially as cabbage on a stic on aua i’s Mount aupu. hen he discovered the endangered succulents here in , there were a do en plants in number. ut over time, the endemic cluster was whittled down to a single survivor, and when erlman arrived to the site one day in , he found that this remaining awaiian palm had died. erlman unearthed it, ripping its roots from the

ground. Then, succulent in hand, he drove to a bar and ordered a drin . Setting the wilted plant down on a table, he gave it a heartfelt toast. e called his wife to say he wouldn’t be home for a while, before proceeding to drown his sorrow in beer. ater that night, erlman wrote a poem about the death of Mount aupu’s last righamia insignis

“Slowly, and without any fanfare These jewels of creation have slipped Into oblivion

Nevermore to grace our world O man, who can measure What we have lost?”

Today, only one righamia insignis is believed to be left in the wild. ut erlman is comforted by a simple, scienti c fact There is still hope. sn’t that incredible erlman says. ven when you’re down to one plant left, it is not doomed. e don’t give up, because diversity can come bac . ll of these plants have a ghting chance.

The loss of even just one of the delicate plant varieties ensconced in the folds of the Kalalau cliffs could hamper the natural world’s resiliency and hinder its ability to provide food, climate stabilization, and shelter.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

WE CAN PUT YOUR FIRST

WITHIN REACH.

With so many new communities being built throughout Hawaii, it’s the perfect time to think about buying your frst condo, townhome or single-family residence. Let us guide you through the loan application process and explore all the fnancing options available.

To fnd a residential loan offcer near you, visit asbhawaii.com/home-loans

Member FDIC NMLS #423168

home

MARK YOUR CALENDAR:

WORLD CLASS POLO COMES TO WAIMANALO

SUNDAY, SEPTEMBER 16 , 2017

GATES OPEN AT NOON HONOLULU POLO CLUB, WAIMANALO POLO FIELD

The Hawaii International Polo Association, (HIPA) Invitational Championship Event (ICE) started originally in 2012 as the White Summer Soiree. From there the Event Team at Dawson Media Group went on to produce Polo Events at Fort Shafter, Schofield Barracks and the Hawaii, Maui and Honolulu Polo Clubs. The goal is to produce up-scale Polo Events, support the US military, local polo communities and raise the public’s awareness of polo in Hawaii.

THE HAWAII INTERNATIONAL POLO ASSOCIATION WAS FOUNDED IN 2013 WITH THREE PRIMARY PROGRAM INITIATIVES:

ONE: celebrate Polo’s unique history in Hawaii dating back to 1880, TWO: establish an equine retirement program, THREE: working with Hawaii’s at-risk youth via horsemanship clinics.

It was determined that establishing an Annual event and fundraiser would be needed to fund program initiatives. With this in mind the Event Team at Dawson set out to bring World Class Polo to Hawaii and established the HIPA Invitational Championship Event. This year is the 3rd Annual event bringing some of the very best professional polo players from across the globe to play polo in Hawaii.

QUOTE FROM HIPA PRESIDENT AND FOUNDER MR. CHRISTOPHER DAWSON: “Hawaii has rarely seen this high level of polo, and it is my ambition to make it a regular thing. This in turn, will qualify Hawaii to be a part of the FIP (Federation of International Polo). When that happens, Hawaii would qualify as a stop on the International Pro Tour drawing polo enthusiasts from all over the world to our beautiful and unique location. Very similar to what the World Surfing League has done for surfing and the SONY Open has done for golf. Internationally renowned Events showcasing Hawaii.”

HIPOLOASSOCIATION.ORG

FLUX FEATURE

The Refrain

In The Leaping Place, a photographer reflects on layers of time and identity in Hawai‘i.

TEXT AND IMAGES BY MATT SHALLENBERGER

I. THE MASTER OF SONG

When was young, made maps. For a while, we lived in a house in Virginia with woods behind it three small forests, connected by a long stream, interrupted by a marsh with winter goose nests. named the regions of the forest as if were an archaeologist, imagining villages and roads erased over time, traces so subtle that only could see them. s a landscape photographer, see every image as an attempt to get bac to that e perience, nding places would have named as a id. oth sides of my mother’s family left ortugal for awai i in the s to wor in sugarcane. She was born on the ig sland, a few wee s before the end of orld ar . My father’s family is from ustria, by way of alifornia. biologist, he came to awai i in the s to study native bird life. was born on O ahu years after my ancestors immigrated, and years after the first uropean landfall.

hen was years old, my dad’s wor too us to Virginia, Oregon, ew Me ico, and then to Virginia again. My parents moved bac to the islands when left for college, and now they live near aimea, on the last remnant of what was my grandfather’s cattle ranch. Most of my mother’s family resides somewhere near where their forbearers first settled, along the m ua oast.

More by coincidence than by design, each photography series of mine begins with finding a boo . n my parents’ house, the umulipo is mi ed in among histories, field guides, and family photo albums. ’m sure saw it as a id, but was never formally introduced to it. The umulipo is popularly nown as the song of creation, and describes the cosmological beginnings of Hawai‘i through to the birth of animals, plants, gods, and men. onceived and memori ed centuries ago by ha u mele, or chant tellers, the umulipo serves various purposes. i e the stories in my mother’s family, it

connects children to their lines of ancestry. i e my father’s biological ta onomies, it classifies and organi es all the forms of animal and plant life. The themes, modes, and landscapes were all familiar to me. ediscovering the umulipo as an adult, while visiting my parents, was li e finding a map of a forest already new intimately. This became a conceptual starting point for e ploring my own history.

studied the umulipo first as a wor of poetry, comparing different translations, and focusing on the way the story was told stories reflecting upon one another, paired opposites, similar and repeated symbols describing birth and death, cultivation, world creation, genealogy. The umulipo was meant to tell several stories simultaneously political, environmental, personal, historical. t incorporated hidden meanings, known as kaona, to connect the layers. fter studying as many interpretations as could find, copied out the poem, combining different translations and removing all annotation, filling the holes with my own scattered notes. made my first map since childhood, mar ing places significant to my family history. nd then too pictures.

ach of the photographs is a large format lm landscape of a place with some signi cance to me or my family history, with each titled after a chapter in Martha ec with’s translation and commentary. n my photographs, some of the interpretations are literal, attempts to illustrate scenes from the stories. Others are metaphorical, or personal. Most are a foggy combination of all three.

The rst photograph in the series is titled The Master of Song. n this chapter, ec with e amines the ha u mele himself, describing his vocal style and use of layered imagery. My photograph shows a cement pylon deep in a awali i Gulch, a remnant from one of many trestle bridges built for trains that carried sugar up and down the ma ua oast. bove this

is where my great great grandfather built his house. i e many of the relics of industry, the pylon has been overta en by the forest, and is now di cult to place in time or scale. t is, for me, a totem, a place to appeal to my own ancestors, my own family gods. eople often assume that photographs are meant to say something specific, but more often than not, they’re an unpredictable mi of intent and instinct, and are offered as questions rather than statements. fter sequencing and titling the series, reached out to learn what it reveals to people with different relationships to awai i conservationists li e my father, who see a story of invasive species ta ing over native ones immigrants, li e those in my mother’s family, who see the small evidences of their history, the cement among the lava mainlanders who have never been to awai i, who see a landscape more violent and comple than the idyllic paradise they’ve been painted and ative awaiians, who see the conflict between the landscape of the umulipo’s time and that of today, altered by coloni ation and industry. That’s one of the reasons call this series The Leaping Place The title refers to a leina a u uhane places from which departed souls begin their ourneys to the underworld. Some of these locations are commonly nown, and others are a mystery. These are the places where we return to the beginning. come from awai i as a ama ina local but not a ana a maoli ative awaiian , returning home but also discovering. awai i is made up of countless stories. envision leaping places as pathways to our common past, and to conversations about our shared present. ach photograph is a haunted step bac into my own history, and a chance to as others about theirs. nd for those whom never meet, perhaps it’s a place on their own ourneys to stop and imagine.

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

PROLOGUE TO THE NIGHT WORLD

II.

III. THE REFRAIN OF GENERATION

IV. BIRTH OF SEA AND LAND LIFE

IV. BIRTH OF SEA AND LAND LIFE

VIII. THE NIGHT DIGGER

VIII. THE NIGHT DIGGER

XIII. THE FLOOD

XIII. THE FLOOD

X. THE DOG CHILD

X. THE DOG CHILD

XVII. THE DEDICATION

XVII. THE DEDICATION

XVIII. THE GENEALOGIES

FLUX FEATURE

Revivin g Kanaloa

A small number of people work to breathe life back into Kaho‘olawe, a Hawaiian island decimated by decades of bombardment by the U.S. military.

MATTHEW DEKNEEF

BY

TEXT

BY

IMAGES

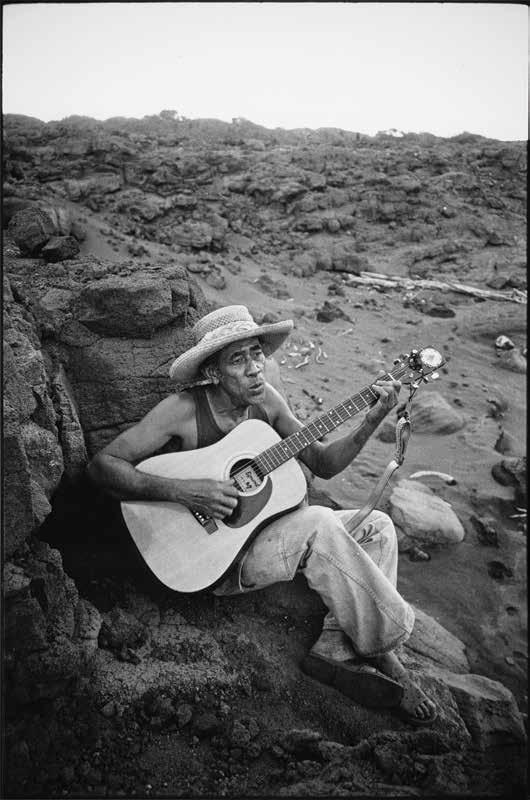

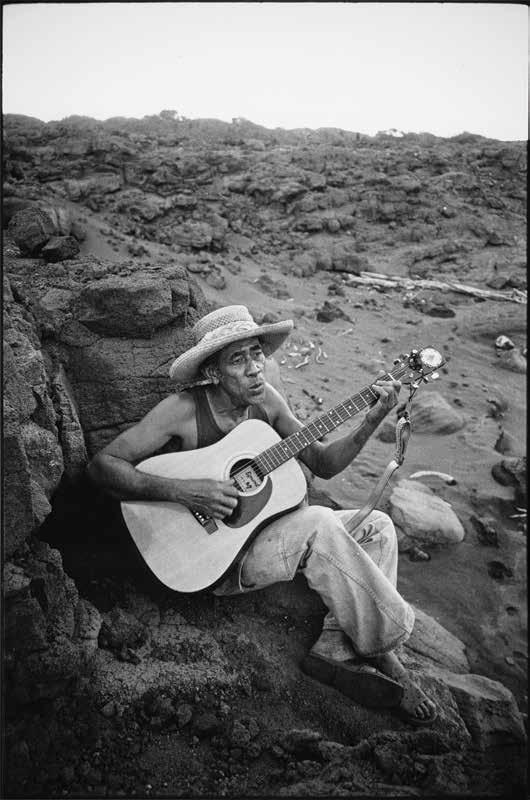

WAYNE LEVIN & FRANCO

SALMOIRAGHI

Pa‘a pu ka mana‘o o no ka pono o ka ‘ā ina I mua na pua Lanakila

Kaho‘olawe.

Together in one thought to bring prosperity to the land Forward young people and bring Salvation to Kaho‘olawe.

“MELE O KAHO‘OLAWE” BY

HARRY KUNIHI MITCHELL

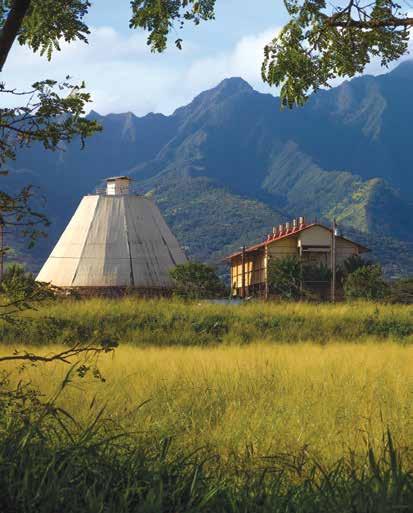

Blistered raw by the sun, aho olawe, in the recesses of its hardpan valleys and soil stained with red dirt, loo s li e a heart e posed. On the northeast region of the island, a reforestation effort runs the impressive, if e hausting, grid of three football fields. ong blac rubber hoses bloated with water spool perpendicular down angular slopes with the adroit ambition of arteries. They heave, deflate, and occasionally spray mist alongside rows of native flora, the bloom of tender ma o, ilima, and a ali i barely rising past the an le. hile this soft machine is a hopeful sight, its irrigating sound a wea hiss of freshwater into the wind is regrettably reminiscent of a person, breathing through a host of tubes, on life support.

On our third day on aho olawe, we stac ed roc s. nvironmentalists, engineers, archeologists, awaiian cultural practitioners, doctors, and ournalists, the of us had traveled to see the island’s scars for ourselves, and what could be done to heal them. Titles aside, we might have more appropriately been referred to as students of the aho olawe sland eserve ommission, a program that organi es a monthly stream of volunteer visits, though its funds are running dry. For an hour, we arranged the roc s into compact raised circles in the highlands of anapou, one of eight ili, the traditional subdivisons that comprise the island, building ma eshift planters that will later

be scattered with seeds. The notion is that, in this windswept region, the roc s will protect the ernels from wind but allow for dirt to accumulate over them, fostering an ideal opportunity for germination. Some will sprout, most won’t, we were told. place li e aho olawe can ta e those chances there’s nothing left for it to lose. ll this because you can’t dig on aho olawe. istory won’t allow it. From to , the island’s square miles were used as a bombing range and training facility by the nited States military, a year wound opened in response to the Japanese attac on earl arbor during . The devastation of this preemptive violence is found everywhere in the landscape, which is poc mar ed with erosion that is worsened by harsh tradewinds and a lac of vegetation. The island is in a perpetually parched limbo ithout plants to absorb rainwater, the island’s soil can’t replenish itself and runoff races to the sea without topsoil, plants that could unloc the foundation for any semblance of an ecosystem struggle to ta e root in the hardpan. This erosion began long before wartime, with the introduction of sheep, cows, and goats, which overgra ed the island through the military occupation by , the goats numbered , . Today, they are gone. ut as the e terior of the island wears away at a rate of nearly million tons of soil each year, more and more une ploded ordnances and fragments surface

Man is merely the careta er of the land that maintains his life and nourishes his soul. Therefore ina is sacred. The church of life is not in a building, it is in the open s y, the surrounding ocean, the beautiful soil.

Written

by George Helm, who was lost at sea in 1977 after an attempt to rescue protestors believed stranded on Kaho‘olawe.

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Harry Kunihi Mitchell was a mentor to the Protect Kaho‘olawe ‘Ohana. Shown here at Hakioawa in 1979, he sings “Mele o Kaho‘olawe,” which became the unofficial anthem of Protect Kaho‘olawe. Harry wrote the song after the disappearance of his son Kimo and George Helm, who were lost at sea in an attempt to rescue protestors believed stranded on Kaho‘olawe.

Retrieved shell casings found during cleanup sweeps of the island by the Navy Explosive Ordnance Demolition Crew.

Retrieved shell casings found during cleanup sweeps of the island by the Navy Explosive Ordnance Demolition Crew.

Unexploded artillery shells are displayed on a jeep during a Navy search mission of the topside live fire area of Kaho‘olawe during early cleanup operations, circa 1993.

Each winter, southern storms bring life-giving rain to Kaho‘olawe’s grasslands. At the same time, upland soil erodes away, and red silt and mud from erosion is deposited at the shoreline. Photographed in 1993 near Hakioawa Bay on the east side of the island.

a reminder that, for decades, aho olawe was assaulted with an arsenal of military grade roc ets, guided missiles, bombs, grenades, and T T so e plosive it is believed to have crac ed the island’s water table.

On our rst afternoon on the island, after par ing our four wheel drive truc s at another ili to remove invasive waist high fountain grass, we cautiously stepped around a rogue pile of bullet casings and shrapnel. Multiply that scrap metal by million pounds, and you have the estimated amount of material removed from the island’s interior following the .S. government’s handover of aho olawe to the State of awai i. Only percent of the island has been surface cleared o cially called Tier . reas cleared an additional four feet below the surface Tier are considerably less, only about percent. ative plants, then, are critical to the island’s preservation, and to alleviating the dread of simply wal ing on the island’s surface. ecause volunteers are only able to plant them in the designated tiers, their presence also indicate you’re in a one that’s been deemed safe for passage, by car and foot. eing surrounded by these stone planters creates a mutual feeling of refuge. e protect the island, and the island, in turn, protects us. i e most sacred spaces, life and death’s dualities fold into their boundaries, often une pectedly. Someone concluded the planters resembled mini ahu, awaiian altars another whispered that they loo ed li e gravestones. e ept on stac ing until there were no stones left. enturies ago, aho olawe went by another name ohe M lamalama O analoa, or analoa, for short, an a ua of the ocean and one of the four ma or

awaiian deities. The island is one of analoa’s inolau, or bodily forms. ts reverence is carved into boulders at oa a, where petroglyphs that date bac years have been recorded. They are noted for their unusual and idiosyncratic aesthetic human figures with inverted, triangular heads bisected at the center. early half of aho olawe’s nown petroglyph sites house these styli ed head shapes detached, headless, or draped in headdress. rcheologists theori e they could represent huna or demi gods they could also be allusions to numerous royal ali i visits. The emphasis placed on these religious sub ects echoes the island’s enduring status today as a spiritual center. t seems that even when ancient awaiians were chipping away at stone to create the memorials, they were already consumed with the island’s effect on the human consciousness.

t’s better to let these p ha u, or roc s, spea for themselves. ven George elm, alter itte, oretta itte, oa mmett luli, and other aloha ina warriors whose personal writings were published in Na Manaʻo Aloha o Kahoʻolawe struggled with e pressing the island’s significance. The place was too heavy for words, many felt, which only inspired action. Man is merely the careta er of the land that maintains his life and nourishes his soul, elm wrote in a letter. Therefore ina is sacred. The church of life is not in a building, it is in the open s y, the surrounding ocean, the beautiful soil. elm and imo Mitchell whose father, arry unihi Mitchell, wrote Mele O aho olawe were lost at sea after an attempt to rescue protestors they believed were stranded on aho olawe. found this limit on language, against the limitlessness of the landscape, to

hat can write of is inship. This, felt in nearly every wa ing hour on the island, kneeling in the sand, dirt, and salt with the other volunteers.

As the exterior of Kaho‘olawe wears away, more and more unexploded ordnances and fragments surface— a reminder that, for decades, Kaho‘olawe was assaulted with an arsenal of military bombardments.

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The akua loa, or banner of the god Lono, is carried across Hakioawa in 1987. The procession marked ceremonies and offerings celebrating the end of the Makahiki season. Through access to Kaho‘olawe, Native Hawaiian culture was reborn in the hearts and minds of many young Hawaiians.

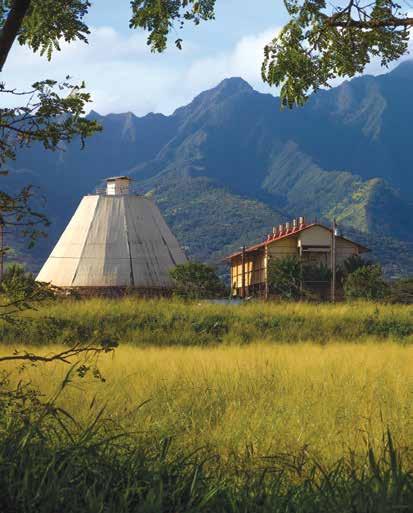

Flume from an old cattle ranch.

Flume from an old cattle ranch.

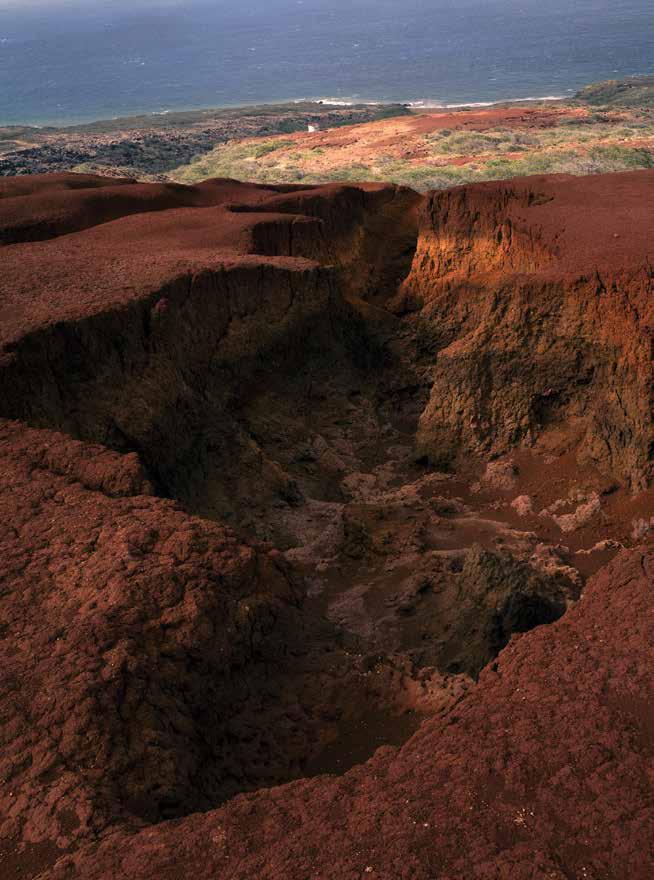

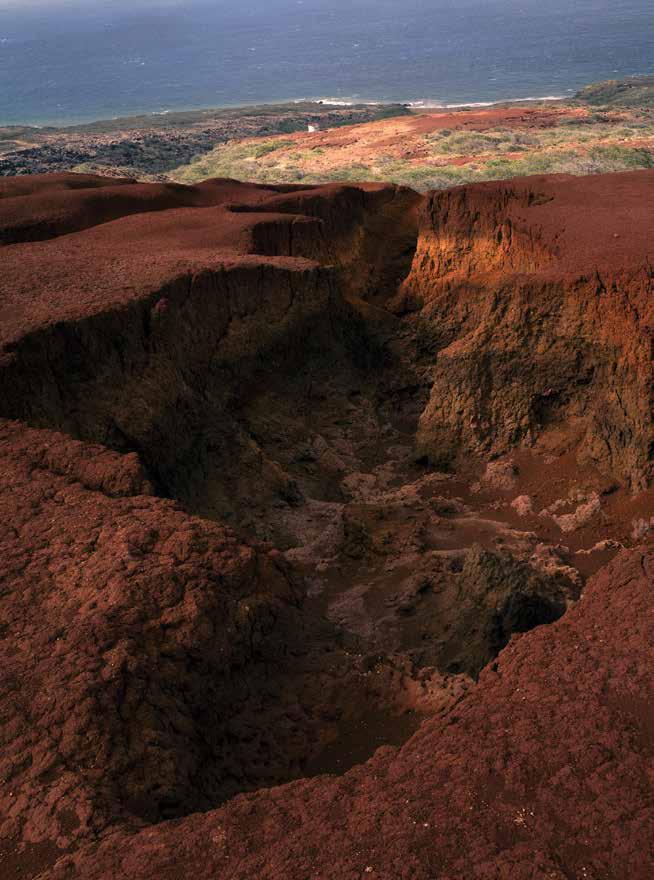

Major erosion above Hakioawa.

Major erosion above Hakioawa.

be a comfort. aving spent a mere weekend on aho olawe compared to its foremost guardians, the permanent aho olawe sland eserve ommission staff and independent members of the rotect aho olawe Ohana, people who’ve tirelessly devoted themselves to the island’s right to e ist in peace since the s feel admittedly foolish and incompetent to pontificate on its sacredness.

hat can write of is inship. This, felt in nearly every wa ing hour on the island, neeling in the sand, dirt, and salt with the other volunteers.

Side by side, we planted shrubs of a i a i, a

native grass, in the lowly sand dunes of ono ana i. n the late afternoon, we bodysurfed freely on the beach, our laughter and pearly grins floating on the whitewash. longside a tidepool, the eldest volunteer e tended to me the largest opihi ’d ever seen in my life, and the gesture itself felt li e its own ind of sacrosanct act. t sunset, a glow settled over our camp, where the grill si led with pulehu stea s. Our s in salty and bronzed, we sat in communion, loo ing across the ocean as its waves pulsed against the shore, and no one spo e. e ust listened.

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Crest of Moa‘ulaiki, looking toward the Kealakahiki Channel with L ā na‘i and Moloka‘i in the distance.

Curb Your Exposure

Social media has opened a window to the world. Its influential and eager users are left to wonder what impacts their online projections have on physical places, sacred and unseen.

TEXT BY BEAU FLEMISTER

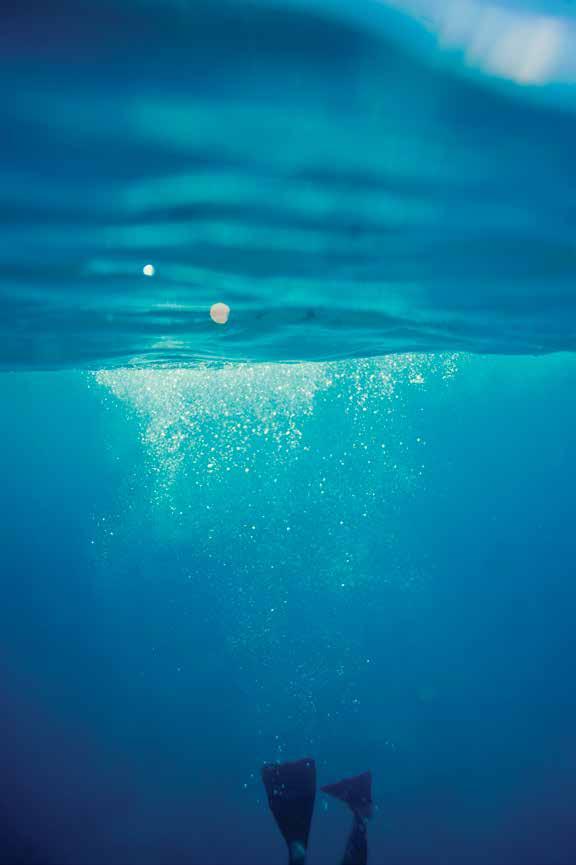

Social media users, like Kaua‘i-born Chelsea Yamase, whose media account is a surreal gallery that depicts her in extraordinary natural spaces across the globe, are reexamining their impact on physical spaces. Image by Bryce Johnson.

FLUX FEATURE 64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Ihave a photograph of myself standing ne t to a pile of human s ulls. eep it tuc ed away within the plastic sleeve of a photo album deep inside my closet. n the picture, my arms are outstretched, as if to say, Get a load of this am wearing a bright yellow cap that reads ot hic s. t’s a confusing photo.

am no anthropologist. found myself in that specific place in time because, some years bac , had a fascination with the deep South acific. was obsessed with the cultures of Melanesia, the cargo cults and land divers of Vanuatu, the pre contact tribes in the highlands of apua ew Guinea, and the region’s peculiar, not so distant cannibalistic past.

The islands of Melanesia are big, but the guideboo s are slim. saved up a few grand by par ing cars and pounding nails, bought a multi stop tic et, and went there. visited villages in apua ew Guinea, where little children who’d never seen a white man too one loo at me and ran away crying. n the highlands, saw women whose faces were covered in intricate tribal tattoos. witnessed a circumcision ceremony on the island of Tanna in Vanuatu, and felt the ground sha e as boys from four villages marched in for the celebration feast. saw warriors with bows and arrows, children hunting giant fruit bats with slingshots, and it was all much more e otic and humid than could have ever dreamt.

On an obscure island in the Solomon slands, the morning after hunting for coconut crabs beneath the light of a full moon, a local guide led me along a trail, up a mountain that ended at a pile of s ulls. t was the shrine left behind by a cannibal

ing, he told me. long with do ens of human s ulls were bits of coral ewelry and a crocodile s ull. There were no other bones from the human anatomy. Just many, many s ulls.

do not now if there is a polite way to as a local man to ta e your photo in front of such a macabre and presumably sacred place, but he didn’t seem to mind my fumbling request. Click .

This was shortly before the dawn of Faceboo and the normali ation of sharing every moment with the world. uring my travels, was armed with only a cheap disposable camera. t wasn’t until after returned home from my ourney that printed the pictures at ostco’s photo center and then slipped the by inch prints into a leather album also bought at ostco, in a two pac , of course .

hen loo at that photo a decade later, the emotion that emerges is not nostalgia, but rather, shame.

Today, we’ve all seen the efects that social media can have upon a place. The dive bar loses its grime but gains men with top nots. Trails are eroded by a surge of visitors. istracted hi ers die. Secret beaches are unveiled and soon littered with trash.

hen spo e with arbara runo, a past president of the awaiian Trail and Mountain lub, she spo e of the impact of social media on O ahu’s environment. can certainly say that in the ’ s and most of the ’ s, the trails on O ahu were usually empty, she says. n the last decade, however, there’s been a dramatic increase. n the past, the point was to go hi ing, and then maybe you would share some photos that you too later. ut now, it seems li e Image by Tara Rock.

n the past, the point was to go hi ing, and then maybe you would share some photos that you too later. ut now, it seems li e it’s the sharing that is the central point of the e perience.

Barbara Bruno, former president of the Hawaiian Trail and Mountain Club.

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

it’s the sharing that is the central point of the e perience.

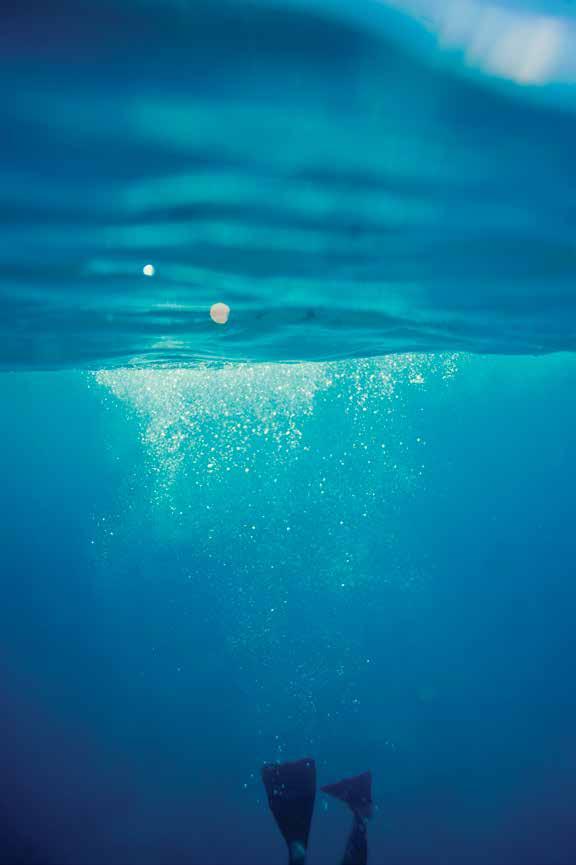

scapism has always been sought in society, but these days, social media users e hibit a sense of FOMO that’s a fear of missing out, for the socially obtuse li e never before. This plays out in our social feeds. e worship, follow, li e, and tap tap tap on the feeds of others who appear to be living the dream, those whose days are spent adventuring through cavernous valleys or piercing the ocean’s crystalline surface.

One such social influencer is athlete, model, and blogger helsea amase, whose nstagram feed chelsea auai is astonishing. amase’s more than , followers and counting view images of her lounging underwater on a bed of swaying sea grass, while a school of shar s circles above her somewhere off the coast of eli e. These followers double tap on pictures of her perched atop an obscure roc y pea overloo ing a valley on O ahu, or see her ushering in the dawn, posed at the gates of heaven above a volcano in ali.

ndeed, there are many nstagram accounts that resemble amase’s, all yelling triumphantly, am here, hear me roar amase’s fame, however, is not merely a result of smo e and mirrors.

aised on aua i by her father, a commercial fisherman and surfer, and her mother, a triathlete

and equestrian, amase was reared as a land and sea outdoorswoman. She can freedive to a depth of feet on one breath and casually ogs across towering ridgelines.

Over the years, amase has parlayed this lifestyle into a personal brand of influence, and is she is now hired by companies

to produce, photograph, and often star in marketing campaigns that highlight a particular product.

don’t thin anyone can stop the spread of information about beautiful places, amase says. The nternet and social media are too good at disseminating information to really manage it

“Culturally, among Hawaiians, there was always permission, training, knowledge, and lineage required. There was always a purpose to explore,” says Clifford Kapono, who has been using analytical chemistry to investigate the impacts humans have on their environments.

GOLD 2016 SPIRITS COMPETITION

efectively. thin a better way to approach it is to create an environment of conscious outdoor users.

hile amase’s nstagram account is a surreal gallery that depicts her in e traordinary natural spaces across the globe, she strives to use her reach responsibly, educating viewers about environmental issues connected to the shot and prioriti ing environmentally conscious brands. amase has even developed a personal code of ethics that she follows for her social media presence, in an attempt to mitigate any potential damage her e posure could create. few points include

elete comments that mention the location of photo or strong hints to it, and if possible, private message whoever commented to e plain why.

Only post photos that follow eave o Trace recommendations i.e. not camping ne t to a water source .

o photos touching marine life or images that could be ta en as implying it’s O to chase after or swim intrusively toward them.

e used to educate and pass nowledge one to one, amase says. nd, in a way, it ept things much safer, because you would hi e with someone and they would teach you, ey, this area is special, these plants are sensitive, this is an ancient heiau.’ ow, it’s one person reaching hundreds of thousands of people, and there is immense power and responsibility with that.

lifford apono, a scientist, surfer, and independent filmma er, has been

e amining how social media’s e posure affects awai i from a scientific lens. urrently obtaining his doctorate in chemistry at the niversity of alifornia, San iego, apono uses analytical chemistry and genome sequencing tools to investigate the impacts humans have on their environments.

cross social media, we’re commonly encouraged to interact with nature, apono says. nd thin that’s fine and healthy, but we’re finding out what that interaction actually loo s li e on a microscopic level. For e ample, for his Surfer iome ro ect, funded by a grant from the San iego Global ealth nstitute, apono is traveling to five continents to study how the chemicals and bacteria on surfers’ bodies affect their environments on a molecular level, and vice versa.

’m not spea ing on behalf of all ative awaiians, but for myself, was brought up that we have boundaries, apono says. thin there’s a huge difference in perspective between the community of social media and the community of indigenous cultures.

The message of social media, apono e plains, seems more closely tied to a estern mentality to coloni e and conquer, be an adventurer, e plore the un nown, he says. ut culturally, among awaiians, there was always permission, training, nowledge, and lineage required. There was always a purpose to e plore. nd that purpose was only to maintain a balance in accountability and stewardship.

f we’re to be good stewards of the land in awai i where resources are in fact limited— then we should probably keep in mind what a photo connected to thousands of followers could do to a place, Tara Rock, the woman behind the popular surffashion blog Ladyslider. Image by Tyler Rock.

72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Image by Tara Rock.

Image by Tara Rock.

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 75

Tara oc , the woman behind the popular surf fashion blog adyslider, reassessed her social practices after tal s with apono. round two years ago, my wor started to feel ind of meaningless, says oc , who is hired to create fashion and travel stories for brands like Teva and loomingdale’s. More than pretty photos of a person in a place, I wanted to bring some sort of significance or purpose to every shoot did. Maybe the audience could even learn something about the place other than it being some static location.

In a poignant call to creatives in a blog post titled, Sacred laces, she questioned the way the social community herself included portrays and uses awai i in its wor or play. hen a company emails you as ing to wor on a campaign it is easy to compromise the people and places around you, she wrote online. ’m guilty of this. will shoot a lifestyle campaign at the e pense of a photogenic location. nd there is always some level of contrived imagery involved. So essentially, it’s not real.

Since this reali ation, oc has been more mindful of the impact of her wor . ecently, when Teva hired her to promote the release of a new shoe collection, Rock embarked on a camping adventure in ahana State ar on O ahu’s east side. er blog post, titled On eing a More onscious amper, cited a cursory review of local area history and listed environmentally friendly camping tips alongside adventurous photos of

her sporting Teva’s newest offerings. t’s a fine line.

f we’re to be good stewards of the land in awai’i where resources are in fact limited then we should probably eep in mind what a photo connected to thousands of followers could do to a place, she says. ust wanted to continue this conversation about people being more diligent with

the content that they’re sharing. thin we should be held more accountable.

Maybe we need to as ourselves, hat are we contributing to society ’ ou can have a million followers, but is that the legacy you’re going to leave

“I don’t think anyone can stop the spread of information about beautiful places,” says Chelsea Yamase, whose image is shown here.

“I think a better way to approach it is to create an environment of conscious outdoor users.”

76 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

In the Light

Residents of Hawai‘i Island find relief, spirituality, and successful business in mineral crystals.

TEXT BY LEʻA GLEASON

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

Protected by massive clifs, Green Sands each, the gleaming bay at the southernmost point of the nited States, emits hues of sage and citrine when the sunlight hits its sand. eralded for its beauty, and for the sense of peace it instills in those who visit its shoreline, this ig sland beach boasts a glimmering display of one of awai i’s most unique facets olivine. This translucent green mineral comprises percent of the arth’s upper mantle, but it is rarely seen on the planet’s surface. owever, olivine is plentiful on the ig sland, home to the world’s most active volcano, since the mineral surfaces with magma, crystali ing as the molten roc solidi es, and dislodging via erosion over time. t Green Sands each, where the weather and waves erode the encircling clifs, olivine crystals dot the beach in such plentiful numbers that the sand actually appears green. On this island of olivine, several residents have felt the calling of such mineral manifestations, and have become crystal collectors.

REFLECTING LIGHT

On the ig sland’s southeast coast, in the una district, waves lap energetically at the large roc s that, when molten, flow over the town of alapana. t the edge of the roc s, a new beach is slowly forming. earby, lava from alema uma u rater continues to pour into the ocean, putting on fiery displays for legions of visitors who travel by land and sea to catch a glimpse of the spectacle.

long the viewing path to the current fow stands an outcropping of tiny homes, where feet erode gravel paths and sweat drips down the brows of e cited tourists. ere, local resident erry ong tests boundaries of former e pectations

about the life he once had, eroding away unnecessary ideals and e panding his mind. The solitary man’s tiny home, low on Mauna oa, is easily recogni able. long the road to the lava sits a small shed with an image of ele, the awaiian goddess of fire, that was painted by local artist an Madsen. earby, a small platform lined with turf is mar ed with a sign inviting tourists to sit down and rest amid the sweltering, arid heat. Orchids and tree ferns that ong has tuc ed into lava niches offer pops of green where soil will eventually form in the crevices, aided by a little cinder, mulch, and the roots of the flourishing plants.

earby on the property sit two more structures one, a modest itchen the other, a tiny room with one ma estic purpose to house ong’s hundreds of crystals. The smaller among the cache are displayed in wooden cases with individual cubbies, while the larger hun s rest on tables and the floor. ong has been collecting crystals for three years, but it was nearly seven years ago when he says he first felt a calling to become more spiritually aware.

ong had been financially successful as a property manager in alifornia, and later in awai i, and was happy living what he called a material life. ut he felt there might be something more substantial to pursue. hile in awai i, ong sought advice from those around him, li e his acupuncturist. ut it was ong’s tattoo artist, who added a manta ray image in reverence to ong’s passion for canoe paddling to the blan et of tattoos covering his bac , who sent ong down the path to spiritual awa ening. Three days after getting inked, Long was paddling in Hilo ay when a large manta ray leaped from the water in front of his canoe.

get so many compliments from people saying they feel the energy coming out of this place more than before, says crystal collector erry ong.

In Kalapana on Hawai‘i Island’s southeast coast, Kerry Long’s crystal room helps him to test boundaries of former expectations about the life he once had, eroding away unnecessary ideals and expanding his mind.

80 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The encounter left him feeling that there was rhyme and reason to everything happening in his life.

round that same time, ong says, his life began to change. olors flashed behind his closed eyelids, and the sound of Tibetan singing bowls would ring in his ears, despite his being nowhere near them. e began to e perience through feeling rather than nowing, and the feeling he found when he discovered his first crystal, he recalls, was magical and indescribable.

ong has never studied geology, or contemplated the metaphysical properties of crystals. ust loo at it and feel, and people tell me what they supposedly mean, he says of his crystal selection process. The pieces he brings into his home are always on display and sometimes held or worn around his nec on special occasions.

hile ong has spent most of his life in and around the water, at his tiny, crystal filled home amid miles and miles of barren lava fields, he see s to harness a new element fire. ong feels he was called to live in this particular home, ust miles

from the active lava flow, despite being afforded no insurance, should ele change her course. Still, he says it’s worth it to live in an area of such active creation.

n ong’s crystal room, a seashell curtain clin s softly as wind blows through the open window. Occasionally, beams of light catch one of the crystals, sending rainbows dancing throughout the room. One of his favorites among the gems is quart , which he has in many shapes and si es. One day, ong hopes to offer massage therapy in this room, where he feels the energy of the minerals will positively affect recipients.

Since purchasing the house and property, ong has come up with various improvements and pro ects, li e the mural of ele he commissioned to be en oyed by those hi ing to the lava. ong gets comments about it from tourists and residents ali e, some of whom have watched his property evolve over visits to the active lava flow. get so many compliments from people saying they feel the energy coming out of this place more than before, he says.

Though Long has never studied geology, or contemplated the metaphysical properties of crystals, he says the feeling he found when he discovered his first crystal was magical and indescribable.

82 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

REFRACTING MINERALS

own the slope of Mauna ea, tuc ed ust above ilo town in the aumana area, are two individuals who also love crystals as much as erry ong ora ndrews and ristof augher. ndrews is airy, mysterious, and sweet, while augher is patient, contemplative, and comparatively outgoing. oth are wildly passionate about mineral crystals. The couple run a booth at the owntown ilo’s Farmers Mar et, which is where they met years ago.

Originally, the duo set up shop to sell their ewelry made with mgambo seeds, which loo li e delicate velvet coated beads. ut now, at this booth and in their everyday lives, augher and ndrews are on a crystal ourney that began by chance and has now evolved into their current business, Shine rystals.

The couple began incorporating crystals into their creations when a friend, who happened to be a crystal dealer, gave augher a piece of orth arolina a e tulite that made augher feel a physical shift within his body. This acquaintance told augher that the a e tulite had been telling him it needed to come to augher, so he passed it along as a gift.

Once augher held the roc , he says, t was ust an immediate, overwhelming e perience for my whole body. hen that crystal got into my hand, it shot energy up into my left arm and then into my entire body.

t too augher, who was originally fascinated by the mineral components of crystals from a scientific perspective, a while to wrap his head around the e perience. There’s a density in the human mind that refuses to believe that’s real, he says. That’s a really big leap of faith for people, to say that they felt it. ou’ve now put yourself in a camp, pitted against the non believers. ut after this e perience, augher says he began to physically feel the effects of other crystals when he was around them, manifested in things li e better sleep quality or more vivid dreams. Similar shifts in awareness have been documented do ens of times by those involved with crystals, particularly by obert Simmons, a pioneer in the metaphysical, human facing properties of mineral crystals. onvinced about these effects, augher and ndrews began collecting crystals as a hobby. Soon, the couple began incorporating them into the ewelry they created. Today, they deal in both handcrafted ewelry and rare mineral crystals from around the world, and collate their e tensive personal crystal collection. They have also created proprietary groups of crystals based on how the stones interact, which they sell as pac ages. These organi ed groupings of crystals, according to augher, assist in attaining physical and mental wellbeing. They can also be laid out to create crystal grids geometric

to crystal distributors Cora Andrews and Kristof Baugher, the scientific properties of the minerals that make up crystals interact with the human body’s chemical composition and account for the feeling of energy.

patterns of crystals that help the user to focus his or her intentions and manifest quic er results.

Through their wor , augher and ndrews interact with massage therapists, rei i healers, and tarot card readers. istributing crystals is delicate wor , since the end users can be quite sensitive. The couple says that they have become attuned to the effects of various crystals, and find themselves halfway between the science camp and the metaphysical camp.

ccording to augher, the scientific properties of the minerals that ma e up crystals often light al ali ing metals, li e beryllium, strontium, or rubidium interact with the human body’s chemical composition and account for the feeling of energy. ealers who use crystals choose those that they believe aid them or their clients in physical, mental, and spiritual wellbeing, with effects ranging from lowered stress to increased ease in the brea ing of bad habits.

84 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

According

’m into the really powerful crystals, the metaphysical roc stars that have very rare chemical compounds, says augher, who favors phenacite, moldavite, and rhodi ite. ccording to him, these crystals can ma e a person feel more aware, alert, and alive.

e adds, ora is into the ones that are very calming and meditative and either contain lithium or have soothing qualities which nurture the soul. These include un ite, auralite , and quart . The pair li es to sit and rela with their crystals nearby. Sometimes they hold them, meditate while holding them, or even sleep with them.

On the other hand, the business side of Shine rystals requires not spending too much leisure time with the minerals they plan to sell. nstead, augher and ndrews match clients with the right crystals for each person’s unique and individual needs, listing the loo , feel, and beneficial qualities of each crystal carefully on their website for the public to see. ccording to the couple, many of the crystals they sell are rare, all of which were specially sought out for clarity, origin of location, and chemical composition.

Our clients are super e cited to feel the energy of something they haven’t e perienced yet, augher says. e were in the e act same position, saying , O ay now gotta try this

one ’ ou’re waiting for the mail to come so you can feel the energy of this crystal and see where that ta es you in life. t’s this beautiful unfolding.

“There’s a density in the human mind that refuses to believe that’s real,” Baugher says. “That’s a really big leap of faith for people, to say that they felt it. You’ve now put yourself in a camp, pitted against the non-believers.”

86 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Waikolu Valley on Moloka‘i. Image by Jeff Hawe.

Waikolu Valley on Moloka‘i. Image by Jeff Hawe.

EXPLORE

“I

don’t think you have to be a Christian or a Buddhist or a Native Hawaiian or an astronomer to appreciate … and experience the moments that other human beings feel are sacred.”—Jessica Terrell

Exiling Ghosts of the Past

With just 13 patients left in Kalaupapa on Moloka‘i, island residents are left to contend with the remote area’s uncertain future.

TEXT AND IMAGES BY JEFF HAWE

long the mile northern shore of Molo a i, towering sea clifs reach , feet into the s y. n their shadow is the alaupapa eninsula, barely ve square miles in total, which on most days feels tranquil. n contrast, its roc y coastline is largely inaccessible even by boat, since the aci c surf pounds it relentlessly.

The steep valleys e tending inland from the crac s of these fortress li e walls are sparsely inhabited. The beaches that front the peninsula, comprised of sand both blac and white, imply paradise. owever, most who now the history of the area, and how it served as a place of banishment for many island residents, know life here wasn’t always so serene.

For years, ative awaiians resided on the alaupapa eninsula, and in the connecting ai olu Valley. The land was divided according to the traditional ahupua a, consisting of three sections alaupapa to the west, Ma analua in the center, and alawao on the eastern side of the peninsula. stimates place the population between , and , at its pea . rchaeological evidence indicates that these small communities thrived, cultivating the land, gathering natural resources, and trading. owever, in the s, estern contact and disease decimated the inhabitants here, as well as in other areas of awai i. y , only about awaiians were left in alaupapa.

The northern coastline of Moloka‘i is largely lined by cliffs abutting the sea. Among them them is the 5-square-mile Kalauapapa peninsula.

90 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

EXPLORE | MO O

“Even if they sent us here ... look around,” says Norbert Kaiama Palea, who was exiled to Kalaupapa in 1947 at the age of 5. “They gave us the most beautiful home in the world.”

THECURRENTOFHAWAII.COM | 91

n , ing amehameha V passed n ct to revent the Spread of eprosy, banishing anyone diagnosed with ansen’s disease, better known as leprosy, to the remote peninsula. The disease was spreading across the islands, ta ing an especially brutal toll on the awaiian population, who possessed few immunities to disease. ith no nown cure and very little understanding regarding it, isolating those afflicted seemed the safest resolution. The oard of ealth, which amehameha V organi ed, acquired lands on the eastern portion of the peninsula in alawao, transferring the sic to this area and moving the remaining healthy inhabitants to the western side.

n , the first patients were dropped off in alaupapa nine men and three women. fter our names, ages and places we hailed from were ta en down, we were left on the roc y shore without food and shelter, patient mbrose T. utchison wrote, according to the ational ar Service, describing his arrival to alaupapa in . o houses provided by the then Government for the li es of us outcasts. The idea was that this collective would occupy the houses left behind by original inhabitants and cultivate the land for food. owever, most patients became too ill to work or even care for themselves. aving been torn away from their homes and left in an isolated, inescapable place to die, many simply gave up.

n , awaiian high chief and politician eter a eo wrote of life in alaupapa to his cousin ueen mma eaths occur frequently here, almost daily. apela last wee rode the beach to inspect the lepers and came on to one that had no oi for a wee but managed to live on what he could find in his hut, anything chewable. is legs were so bad that he cannot wal . y this time, there were people in alaupapa, and the quarantine had become a medical catastrophe. eports of the deplorable living conditions reached onolulu, and abroad. t was during this time that Father amien, a atholic priest from elgium, began wor ing to improve conditions for the a icted. ith aid from ing unalilo and ing al aua, amien established a rudimentary hospital and basic housing on the

peninsula, but after years of unwavering service, the clergyman passed away as a result of contracting ansen’s disease.