AN UP-FOR-ANYTHING MENTALITY PERMEATES ISLAND CULTURE. Adventure is always a priority: swimming, hiking, exploring, and photographing the ‘aina (land) ultimately leads to a deeper understanding of place — an irreplaceable knowledge that echoes through the rhythms of everyday life. O‘ahu – Hawai‘i

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

FLUX PHILES

20 | Culture: Kaʻiulani Murphy

26 | Art: Matthew Kaopio

A HUI HOU

192 | Transit to Totality

FEATURES

30 | What It Means to Walk

Timothy A. Schuler examines how a seemingly mundane act can transform the world.

44 | A Hula Unearthed

Matthew Dekneef chronicles how an all-male hula hālau enlivens one of the form’s most athletic dances.

58 | The Body Is a Vessel

In this personal essay, Martha Cheng reflects on the strength in self found through surfing and paddling Hawaiʻi waters.

66 | It’s in the Moves

Rae Sojot profiles local residents who are united by motion with this kinetic photo essay.

88 | Synchronicity in Solid Ground

Printmakers Charles Cohan and Abigail Romanchak reveal the creative process behind their collagraphs.

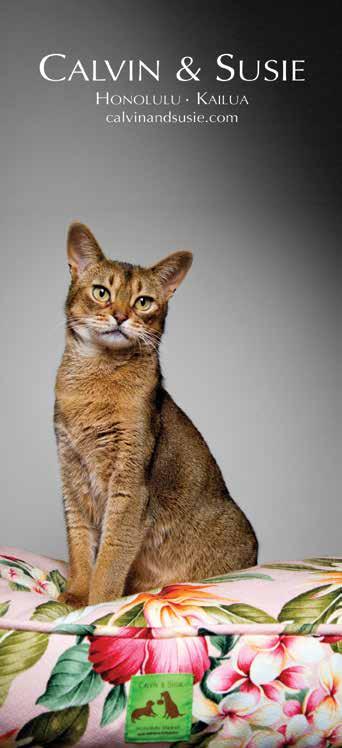

Brought to you by

100 | Hawai‘i’s Sonic Exports

Creative Lab Hawai‘i Music Immersive

106 | From the Top Hawaiian Music’s Unique Song Structure

110 | Sounds of Hawai‘i Recording Studios of Yesteryear

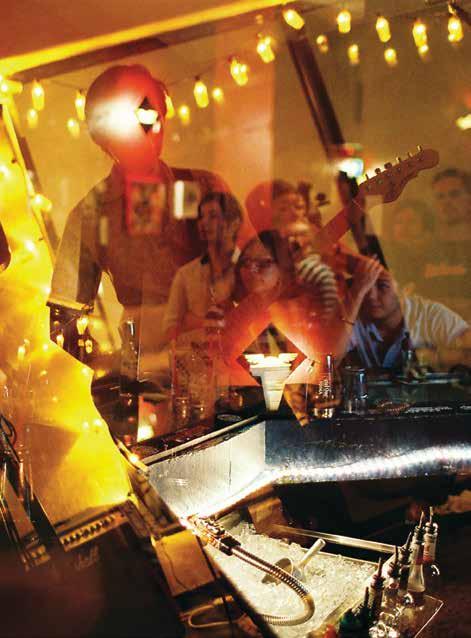

116 | Music in the Moment BAMP Project

120 | Ambassadors of Aloha The Green

124 | Underwater Duets Man and Whales

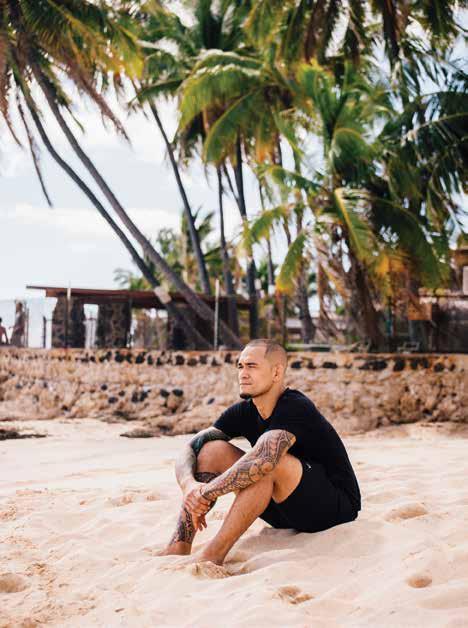

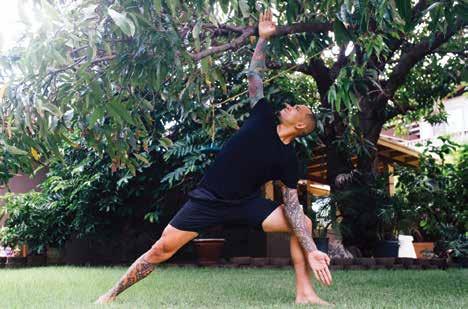

130 | Balance Yancy

136 | Dance Emilia

138 | Dive Benjamin

150 | The Gift of Rain

162 | The Essence of Hawai‘i Contest PhotoCon

178 | Sign of the Times

The World Reflected, Honolulu Museum of Art, Spalding House

“Am I dead?” I ask my acupuncturist, after he informs me of my particularly faint pulse.

It was my third visit in three weeks to his clinic. I sat there awkwardly, with my hand resting on a small pillow on his desk, while he pressed three fingers lightly against my wrist, tilting his head as if straining to hear the soft beat. The pulse, he explained, is like a communication network. Whizzing past major organs and along nervous systems, it is literally “the pulse” on the body’s health and can be used to diagnose ailments or deficiencies.

I had gone to see him on the recommendation of a friend, who spoke wonders of acupuncture’s ability to diminish her pain of a sore ankle. It had been a particularly stressful time for me. Owning your own business has its perks, but it also calls for workdays that stretch late into the night and into weekends. It can result in poor eating habits, scarce physical activity, little personal time with friends and—unhappily, for my still fairly new husband—family.

Athletes like Ryan Leong, who we feature on page 72, talk about “mental toughness,” how putting mind over matter can help the body push through physical pain to cross the finish line. “For any event you want to complete, regardless of whether it’s basic or ultra-endurance, you have to be at peace with the anticipated discomfort, and make the mental decision that you are going to finish, no exceptions,” the triathlete says. “Outwardly, you can say whatever you want, but inwardly, there can’t be an ounce of doubt. Once you’ve come to this mindset, every unexpected obstacle, the suffering, the emotional highs and lows, the desire to just stop moving, can be dealt with because the thought of quitting doesn’t actually exist.”

Acupuncture, I assumed, could work the other way around: settle the mind through the body—specifically, through pricks in my forehead, wrists, stomach, thighs, shins, and the tops of my feet. And it did, to a degree. At each session, the needles were

placed with a quick flick. I scrunched my face to adjust to the needle between my brows, and wiggled my fingers and toes to ease the pressure of needles in nearby extremities. And then I was out cold, waking up dazed, 45 minutes later, to my acupuncturist’s voice.

In the two months that I’ve been receiving acupuncture treatments, and in putting this, our Movement issue, together, I’ve become more aware of how connected the mind and body are. Stress the mind, and the body suffers; treat the body, and the mind can heal. My pulse has improved, according to my acupuncturist. “Whatever you’re doing, keep it up,” he says. Work remains taxing, and I still forget some days to eat lunch. Exercise involves taking the dog out to do his business. Reclining in a lounger once a week with needles in my face is what I’m doing. I’m a work in progress. Another thing that can soothe the mind, and also help get the body moving, is music. And so, it is with much excitement that we announce the launch of FLUX Sound, a new concept event that spotlights Hawai‘i’s sonic talents. In this issue, read about what sets the sounds of Hawai‘i among the most unique in the world, and then come visit us at The Modern Honolulu on December 13 and 14 for our inaugural event featuring Thundercat. The Grammy Award-winning producer will take the stage with local talent, including Izik, Aloha Got Soul, and Front Business, in an experience that fosters cultural connections between global and local musicians.

My pulse races just thinking about it. We hope yours does, too.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada-Son EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Matthew Dekneef

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

DESIGNERS

Mitchell Fong

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

COPY EDITOR

Andy Beth Miller

IMAGES

Michael Keany

Lila Lee

Jonas Maon

IJfke Ridgley

At a boxing gym in Waipiʻo Gentry, Oʻahu, photographer John Hook took this photo of Bree Locquiao, the first female flyweight from Hawaiʻi to win the Women’s National Golden Gloves championship title. Currently, she has her sights set on representing the Islands in the Olympics. Hook dropped in on a training session with Locquiao as part of our photo essay, on page 66, focusing on local athletes, dancers, and entertainers who use motion to inform their everyday beings, both physically and mentally. Watch these subjects in motion in our immersive video series, which can be viewed online and across our @fluxhawaii social media channels. This content is part of an exciting line of lifestyle programming for the NMG Network, a newly launched video platform airing across Hawai‘i and worldwide.

A Kansas native, Timothy A. Schuler writes about design, ecology, and the natural environment.

For the feature “What It Means to Walk” on page 30, Schuler was surprised by how much of the essay was composed while, literally, on a walk. “I’ve long had a habit of taking a walk when I’m feeling stuck or low on energy, and there’s a long literary tradition of doing just that, but here, it became an essential part of the writing,” he says. “Walking while writing about walking created a kind of unfocused attention that allowed my mind to make novel connections, and some days I literally wrote as I walked.”

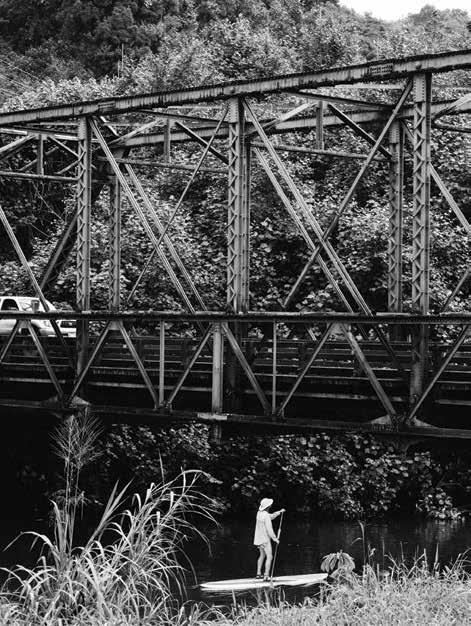

With her award-winning businesses coverage, Kate Mykleseth has reported extensively on the expansion of renewable energy in the state of Hawaiʻi, formerly as Honolulu Star-Advertiser’s energy reporter. Mykleseth turns her attention to the arts in this issue with her profile on artist Matthew Kaopio on page 26. “His accomplishments reinforced the idea that drastic physical movements aren’t required to reap outstanding impact,” says Mykleseth, who also shot and edited a video profile on the artist. “The gradual and delicate strokes of Kaopio’s brush helped to redefine his purpose in life, and it was inspiring to see him as a physical testimony of a mindset I share, just with a different tool.” When Mykleseth isn’t glued to a computer screen cutting her next audio or video project, you can find her stand-up paddling comfortably close to Oʻahu’s east coast or running the streets of Pālolo.

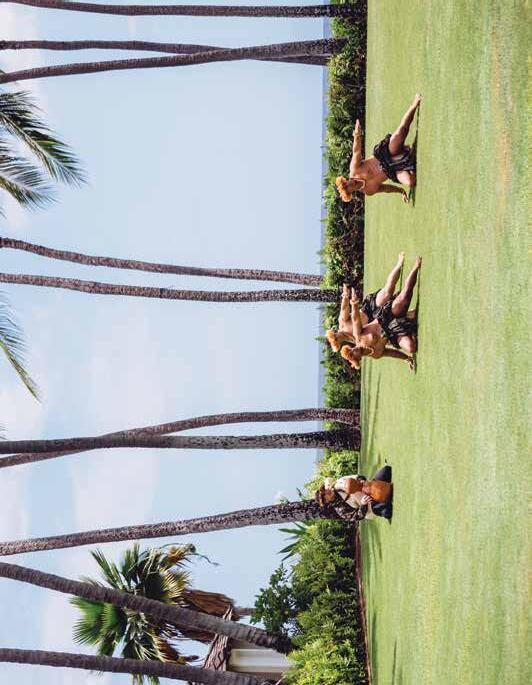

For this month’s issue, photographer IJfke Ridgley captured the dancers of Ke Kai O Kahiki, the all-male hālau based in Waiʻanae, in our story “A Hula Unearthed” on page 44. “It was moving how much ritual, reverence, and preparation the dancers brought to their weekly practice, even though it wasn’t a public performance,” Ridgley says. “On a technical level, the challenge lay in capturing the movement of each individual dancer while also encompassing the incredible setting at Lanikūhonua. Getting to spend the afternoon with some of the best dancers on the island in the most beautiful costumes was truly a treat.” Ridgley has spent part of the last year living in South America, but always looks forward to coming home to Hawaiʻi.

Rollover your 401(k) into an IRA. Ask your new employer if you can rollover to your new workplace’s plan, ask your former employer if you can continue to stay in the current plan, or cash out the account value.† American Insurance and Investments offers:

• Flexibility - a wide array of investment options to choose from

• Single View - manage all of your retirement accounts with American Insurance and Investments

• Tax Advantages - just like your 401(k) or 403(b), an IRA offers important tax benefits†

Meet with a Financial Consultant to discuss all of your options and help you through the process. Call (808) 735-1717 or toll-free (888) 343-5534.

� A pedestrian jogs through downtown Honolulu. Image by John Hook.

� A pedestrian jogs through downtown Honolulu. Image by John Hook.

“It is the movement as well as the sights going by that seems to make things happen in the mind, and this is what makes walking ambiguous and endlessly fertile: it is both means and end, travel and destination.”—Rebecca

Solnit

Navigator Ka‘iulani Murphy leads Hōkūle‘a home from its three-year world journey.

TEXT BY EUNICA ESCALANTE IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK AND COURTESY OF POLYNESIAN VOYAGING SOCIETYWeeks had passed since Hōkūleʻa had departed from Tahiti, and the weather had not been kind. Swaths of clouds, heavy with the promise of rain, blocked Hōkūpaʻa (the North Star) and Hānaiakamalama (the Southern Cross), star formations that would indicate their coordinates. Kaʻiulani Murphy sat atop the vessel’s koli hōkū, the navigator’s seat, straining her arm toward the night sky. Despite the currents, her hand was steady and sure as she lined it up with the horizon in search of the path home.

Murphy was navigating the Polynesian double-hulled voyaging canoe to Hawai‘i Island for the last leg of its Mālama Honua Worldwide Voyage—no small feat when you only have nature as your guide. Without the use of modern instruments, Murphy relied on traditional wayfinding methods, using her hands and eyes as her compass, and the sky as her map. On cloudy nights like this, when no moon or stars revealed the path, and not even the ocean’s surface was visible, she turned to her instincts, and to what she felt was happening. “It’s just a waiting game,” Murphy says. “Be patient for the clues to reaffirm what you already know. ”

The young navigator was chosen for this leg of the trip for a reason, namely, her confidence and composure that’s able to transcend any storm of situations. The inclusion of female crewmembers, like Murphy, on this trip is significant—in the years past, it was difficult for women to earn spots on voyages. She follows in the footsteps of Shantell De Silva, who was the first female navigator to lead Hōkūleʻa ’s journey from Tahiti to Hawaiʻi. “One of the things that young girls can take from Hōkūleʻa ,” Murphy says, “is that you really can be anything you want to be.”

The navigator first encountered the vessel as a child, on an elementary school field trip. Their paths crossed again while she was a freshman at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, when a then 19-year-old Murphy attended a lecture by Nainoa Thompson, who, back in the 1970s, was taught the art of traditional navigation by one of its last remaining practitioners, Micronesian master navigator Mau Piailug. Inspired by the stories Thompson told of the people he met and the experiences he had, Murphy set out to earn her own adventures. The next semester, she declared a major in Hawaiian Studies,

� Ka‘iulani Murphy observes the night sky at Hakipu‘u on O‘ahu, where the Hō k ū le‘a launched in 1975. Murphy is only one of two female navigators to be chosen as the lead navigator of a TahitiHawai‘i leg in the canoe’s 42-year history.

and registered for a course on navigation. Within a year, she was interning at the Polynesian Voyaging Society, assisting Thompson in his preparations for Hōkūleʻa ’s 1999 voyage to Rapa Nui. Hōkūleʻa has long been a symbol for social movements. In the 1970s, the canoe’s successful inaugural voyage to Tahiti helped to restore pride within the Native Hawaiian community. The trip, accomplished without the aid of Western instruments, demonstrated the capabilities of traditional Polynesian navigational techniques. “From the first time that the first missionaries came to Hawai‘i, our culture was devalued, we almost lost our language, and practices like hula were banned,” Murphy says. “The voyaging canoe was one key part of flipping that over, making us aware how intelligent our ancestors really were. That wasn’t in our consciousness until Hōkūleʻa showed us how it could be done.”

After its first trip, the Polynesian Voyaging Society continued Hōkūleʻa ’s travels in order to spread knowledge and pride to communities throughout the Pacific. In 1985, during its two-year Voyage of Rediscovery, the vessel sailed to destinations throughout Polynesia. In the 1990s, No Nā Mamo and Nā ʻOhana Holo Moana took the Hōkūleʻa beyond Polynesia, to islands throughout the Pacific and to ports on the mainland of the United States. The Polynesian Voyaging Society set its sights on the grandest voyage yet in 2014, setting off on the Mālama Honua Worldwide Voyage, a three-year journey circumnavigating the world as a response to today’s threats of climate change. In the last days of this voyage, the crew set their eyes on the horizon. They were on course for Hawaiʻi, as determined by Murphy, having turned toward their final destination at Hānaiakamalama some nights earlier. Within days, the faint

� “It’s just a waiting game,” says Murphy, on wayfinding during unfavorable conditions.

“Be patient for the clues to reaffirm what you already know.”

horizon line had grown, and Murphy recognized it as Hawaiʻi Island. “It felt good to finally bring her home,” Murphy says.

Hōkūleʻa arrived on Oʻahu on June 17, 2017, welcomed by a crowd so large that Kālia, Magic Island, was standing-room only. The homecoming signaled the end of the canoe’s epic voyage. But for Murphy, the journey aboard Hōkūleʻa is far from over. “It’s just one continuous cycle, yeah?” she says. “This is the end to one journey, but the start of the next.” Until then, Murphy will be standing on the docks, looking for her next adventure.

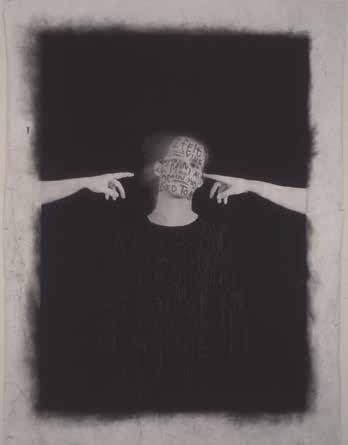

After a diving accident left him paralyzed from the shoulders down, artist Matthew Kaopio finds new ways to express himself.

TEXT BY KATE MYKLESETH IMAGES BY JONAS MAONMatthew Kaopio taps the tip of his paintbrush on the brim of a small saucer filled with water. Ripples of purple spread in the miniature basin and quickly dissolve, leaving a semi-opaque lavender pool resting on the edge of Kaopio’s easel. Different colors of acrylic paints and varying sizes of paintbrushes surround him and the piece holding his focus in the southeast corner of Kahuku Medical Center’s activity room: a nymph with auburn hair overlooking a pond, where a unicorn is embraced by a blonde woman as it bows down to drink from the water. Kaopio brings the brush to the canvas and, with a quick cadence, he shadows a boulder where the nymph lounges. She is perched on the stone as streams of whitewater fall into a dark pool below.

“I’m in the mood to paint something that is out of the ordinary,” Kaopio says. A couple feet outside of Kaopio’s workspace, dozens of his works, some mundane, others fantastical, lean against the wall, all waiting to be sold or gifted to friends: zebras grazing in the midst of a bright orange dust storm, an hourglass-shaped performer holding on to a microphone stand, a sun setting behind Mokoliʻi as waves crash onto the shore. “My dreams are very vivid— I have some incredibly creative dreams,” he adds.

The creation of the nymph’s deep blue pond is surprising when one considers how Kaopio controls his tool: by holding the brush with his mouth. In 1994, Kaopio became paralyzed from the shoulders down after breaking his neck while diving from Waipahe‘e Falls on Kaua‘i. Floating in the water, unable to move, Kaopio thought he had lost the ability to enjoy the activities he loved: swimming, surfing, hiking, even singing and drawing. “From that moment on, I knew life was changed forever,” Kaopio says. “I was probably in a funk for the first three years, just not knowing what the future was going to hold.”

� In defiance of his disability, Matthew Kaopio puts brush to canvas using his mouth to create fantastic works. This method has also doubled as a form of therapy, he says. “I became a lot more accepting of my situation.”

A self-portrait helped pull Kaopio out of his gloom. He signed up for an art therapy program in which painters controlled the brushes with their mouths. After much coaxing by the teacher, Kaopio painted a self-portrait that inspired compliments from the class. He said it came out looking like him, in a “Homer Simpson” kind of way. “I painted it yellow with purple hair,” Kaopio says. “It kind of dawned on me that there are some things I can still do, even though I can’t do it the way I want to. … Seeing myself from that perspective, I became a lot more accepting of my situation.”

To create a painting, Kaopio needs help setting up his tools. The canvas is placed in front of him. The palette and water dish are set below it. He is fitted with a mouth stick. Then, he selects his brush, dips it in one of the dollops of acrylic paint on his palette, and raises it to the canvas. His painting also triggered a different way of thinking that spilled over into his everyday life.

“I decided to try to see how creative I could be to get the results I want,” he says, a realization that emboldened him. He asked strangers to help him get money from his

pocket so he could pay for his groceries. He asked riders around him to push the button for his floor when entering an elevator. “That is when I decided to go back to school and finish my degree,” he says. In 1999, Kaopio completed a bachelor’s degree in Hawaiian studies at the University of Hawai‘i West O‘ahu. Next, he obtained a master’s degree at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Center for Pacific Island Studies. After earning his degree in Pacific Island Studies, he wrote his first novel, Written in the Sky, which was published by Mutual Publishing in 2005, followed by Up Among the Stars in 2011. “Writing was like painting using words,” he says.

Back at Kaopio’s corner workstation, the artist cleans his brush in the waters of the saucer. He raises the brush for the final strokes of the painting. The three streams of bright water divide into five as they fall into the pool below; the unicorn is reflected in the pond that fills the mossy landscape. Just as it does the unicorn’s oasis, moving water frames Kaopio’s journey. “If water cannot flow uphill,” he says, “it will carve another path around the mountain.”

� View of Kaopio’s workstation at Kahuku Medical Center. He has completed hundreds of pieces in his more than two decades of painting.

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

The most mundane of movements, walking is often simply a means of transportation. Yet the act of placing one foot in front of the other has the power to transform the world.

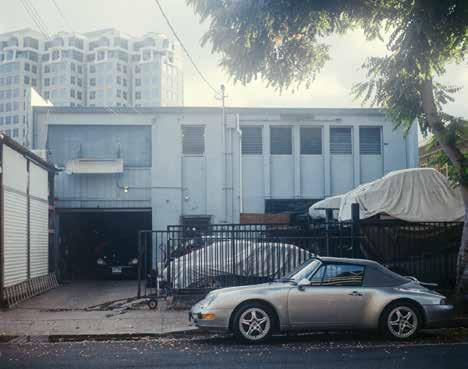

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

I.The women—and men, and toddlers, and teenagers—were not walking anywhere in particular that day. Although they strode with purpose, soon they were back where they began, spilling off the lawn of the Hawai‘i State Capitol, having trekked less than a mile. Distance, of course, was not a metric anyone cared about. The presidential inauguration had taken place just 24 hours earlier, and the Women’s March in Honolulu was one of 600 similar actions around the world, with more than two million people protesting an American president they saw as being a direct threat to themselves and their values.

In Honolulu, an impenetrable layer of clouds cocooned the city as an undulating column of pink shirts and hand-painted cardboard signs stretched from the Frank Fasi Building to ‘Iolani Palace. The march had swelled beyond the sidewalk and onto the rain-slicked streets, and even during the intermittent downpours, the mood was somewhere between buoyant and defiant. We were 5,000 miles from Washington, D.C., and yet in our collective motion, we became part of a global protest.

Around the world, and across centuries, acts of resistance often have taken this simplest of forms: walking. In Wanderlust: A History of Walking , Rebecca Solnit writes of participating in a protest at the Nevada Test Site, where, from the 1950s to the 1990s, the U.S. military detonated nuclear bombs. Hundreds of protesters camped on the fraying landscape. She writes, “The form our demonstrations took was walking: what was, on the public-land side of the fence, a ceremonious procession became, on the off-limits side, an act of trespass resulting in arrest.”

She continues, “It was a revelation to me, the way this act of walking through a desert and across a cattle guard into the forbidden zone could articulate political meaning.”

Walking has long been a form of protest. Gandhi famously walked 240 miles from his ashram to the coastal village of Dandi in 1930, joined along the way by thousands of Indians. The walk became known as the Salt March, a three-week-long act of civil disobedience that helped spark the Indian independence movement. In Hawai‘i, plantation workers regularly organized walkouts throughout the first half of the 20th century, like when, in May 1937, 2,500 Filipino plantation workers walked from Wailuku to Kahului to call for equal pay. More recently, in Australia, a 27-year-old aboriginal activist walked some 3,000 miles from Perth to Canberra, protesting the government’s treatment of aboriginal communities.

Even the languages of protest and walking are intertwined. The word “march” comes from the French marcher , which means “to walk.” Of course, soldiers marched before pacifists did, and so the language of nonviolent protest also borrows from war: The African-American men and women who marched in Selma and Birmingham were called foot soldiers.

One of the strangest aspects of the Women’s March was simply the sight of so many walkers in Honolulu. Outside the thrumming hive of Waikīkī, few people traverse the city on foot (besides the inevitable journey to and from their vehicles). Honolulu is not a walkable city. It lacks the density of New York City and the pedestrian scale of Paris. Its biggest growth spurts occurred in the 20th century, after the advent of the automobile, which arrived in Hawai‘i in 1899 and forever altered the future form of its capital. With the exception of historic districts like Chinatown, which remains one of Honolulu’s most walkable—and, not coincidentally, most attractive— neighborhoods, the city is dominated by streets designed for cars.

Recently, however, Honolulu-based artists, activists, and public health advocates have discovered walking as a medium for *From U.S. Census Bureau. car: 81%

4.5%

telling stories, combating gentrification, or simply promoting pedestrianism. No matter why we do it, walking tends to offer us something beyond its express purpose, an extra layer of experience and meaning that is all too often ignored. “It is the movement as well as the sights going by that seems to make things happen in the mind,” Solnit writes, “and this is what makes walking ambiguous and endlessly fertile: it is both means and end, travel and destination.”

II.As children, we are not taught to walk. It is innate, unlike language. Leave a healthy human child to its own devices, and it will eventually pull itself up on two legs. We walk because we are designed to walk.

And yet we spend little energy thinking about it. “Isn’t it really quite extraordinary,” Honoré de Balzac wrote in his 1833 essay, Théorie de la Démarche, “to see that, since man took his first step, no one has asked himself why he walks, how he walks, if he has ever walked, if he could walk better, what he achieves in walking?” In the nearly 200 years since Balzac’s time, scientists have studied everything from the evolutionary benefits of bipedalism to its effect on cognition—and yet in many ways, walking remains, in

Solnit’s words, the “most obvious and the most obscure thing in the world.”

We used to walk more than we do today, and not only because there were fewer ways to get around. Throughout history, people have walked for penance, for sport, to achieve enlightenment, to test the limits of the human body. Artists from Richard Long to Francis Alÿs have made art out of the act. In 2004, Alÿs walked 15 miles of Jerusalem’s so-called Green Line, the border established after World War II, all the while holding a can of leaking green paint. In Phoenix, there exists an entire institution dedicated to artful ambulation: the Museum of Walking, created by the artist Angela Ellsworth in 2014.

Like most people, I started walking when I was about one and a half years old. I didn’t give it another thought until 2008, when I was working my first postcollege job, at the Honolulu Weekly. I had been assigned a piece about the state’s master plan for Diamond Head, and after a tour and interview with an official park spokesperson, I decided to explore the areas around the outside of the crater rim. I had wandered for maybe an hour, not looking for anything in particular, when, on the ocean side, I saw a trail cutting into the brush. I followed it up the slope and around several switchbacks. Without warning, I walked

into a makeshift village. A dozen or so tents were scattered among haole koa trees, dirt paths spidering off to each like a planned subdivision. Near one, a stuffed Tigger doll lay in the red-brown dirt.

After a few minutes at the camp, I made my way back to the road, to the realm most of us inhabit and never leave. I learned that day that the only way to really see the world is to walk. In our cars we whoosh by, blind to much of the world, particularly to its most defenseless populations and the vast inequities that create them. But to walk is to make ourselves vulnerable, a precondition for transformation.

A few months later, I moved to Chicago. I kept walking, and invited others to join me. We would meet first thing in the morning and embark on what I started calling “urban hikes,” walking as many as 15 miles through rock quarries turned public parks and partially abandoned industrial districts. I became familiar with the term “psychogeography”—the idea that the built environment affects our thoughts and behavior—as well as the eccentric French group known as the Situationist International, which coined it.

Led by a Marxist theorist named Guy Debord, the Situationists appear in nearly every written history of walking. Formed in Paris in the 1950s, they were staunch critics of capitalism and had the lofty idea that they could achieve higher consciousness by walking aimlessly through the city. They weren’t successful in overturning Western capitalism, but at least one product of their thinking has persisted: the dérive, or “drift.” A dérive, to Debord, was an amorphous form of walking in which a group of people abandons all “usual motives for movement and action, and lets themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.”

It’s a pretentious notion, and yet, I do walk this way sometimes, eyes open, allowing myself to be drawn by the character of a street, or by the promise of a path whose end I cannot see. Today, drifts are organized around the world, and there are even apps to facilitate them. They’ve been especially popular in New York City, where from 2003 to 2012, there existed a semi-annual psychogeography festival called Conflux, a weekend of themed walks and walk-themed talks. One year, attendees walked through the city guided by a map not of New York, but of Copenhagen, in order to scramble traditional notions of navigation and discover new avenues through the city.

Among the organizers of the 2010 Conflux festival was a young woman named Adele Balderston. Balderston, a geographer and artist, grew up on the windward side of O‘ahu, and moved to New York City for school in 2004. A decade later, she moved back to Hawai‘i and created 88 Block Walks, a series of walking tours that feature oral histories and photographs of Kaka‘ako—ground zero for new development in Honolulu and the controversies that accompany it. The walks, which grew out of an interest in active forms of combating gentrification, are an attempt

�

“I don’t think you can just poke at people and say, ‘I’m encouraging you to walk more,’” says Matthew Gonser, co-founder of the community advocacy group Better Block Hawaii. “We have to work on the physical environment. We have to make it appealing.”

at reclamation. “I’m trying to take back control of the narrative of this place from developers,” Balderston tells me one evening before her fifth and final Kaka‘ako walk, titled “The Living Archive.”

Balderston, who has delicately tattooed arms and a round face dwarfed by large, vintage-looking glasses, started walking regularly when she moved to New York. Mainly, it was a necessity—she didn’t have a car—but it was also a way to get her bearings, to begin piecing together the neighborhoods in which she lived. Searching for an analogy, she asks if I ever played the video game The Legend of Zelda .

“This is really nerdy, but you know how in the beginning you just have those four little squares and everything else is obscured because you haven’t been there yet? It was kind of like that,” she says. “I had to walk each square for that to be part of my mental map of the place. That’s how it started.”

Balderston’s Kaka‘ako tours take place at night. At points along the walk, she projects historic photos of

the neighborhood onto walls of existing warehouses. The images are accompanied by monologues performed by trained actors, adapted from essays housed in UH’s Romanzo Adams Social Research Laboratory Collection. The first stop of “The Living Archive” is on Ilaniwai Street, where a few small storefronts face the back of a large warehouse. Here, Balderston takes people back to the 1920s, when the neighborhood was on an upswing, with new housing for families. In the decades that followed, the area was rezoned, displacing many of the residents. In the high-rise development happening today, Balderston sees familiar cycles of disinvestment and dispossession. “They’re calling it a ‘new place,’ but it’s like, no, this is a hundred-year-old neighborhood,” she says. When modern developers mention the community’s history, she says it is often romanticized, limited to the life of Victoria Ward or the saltponds of a precontact Hawai‘i. There’s little mention of the everyday people who lived and worked in 20th century Kaka‘ako, or of the informal settlement known as Squattersville, a community of close to 700 Native Hawaiian and hapa families that existed along the waterfront.

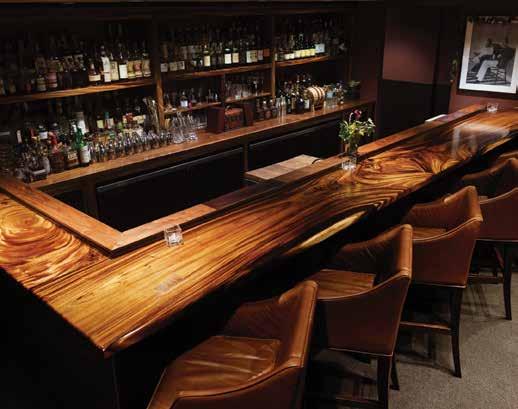

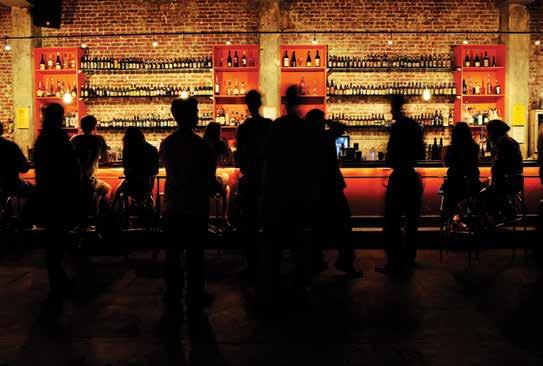

Later, Balderston and I retire to a table at Bevy. It’s early, but the bar is filled with the noise of overlapping conversations. Balderston has lived in some of the world’s most walkable cities—New York, Paris, Seattle—and when she was in those places, she says, walking “was like breathing.” Honolulu is different, she says. The city, with its mess of streets and absent sidewalks, can be punishing for pedestrians, even deadly. In both 2014 and 2016, according to reports by Smart Growth America, Hawai‘i had the highest fatality rate for pedestrians aged 65 or older in the country. For one of her walks, which partly followed a busy street, Balderston made attendees wear reflective vests and bike lights, so that no one would be maimed.

Honolulu’s general lack of walkability creates a negative feedback loop that exacerbates the problem. Walkers tend to feel safer around other walkers, which means that the less people walk, the more

dangerous it feels. “Strange places are always more frightening than known ones,” Solnit writes, “so the less one wanders the city the more alarming it seems, while the fewer the wanderers the more lonely and dangerous it really becomes.”

Not long ago, I attended a very different kind of walk. The route was undefined, as was the distance, which was fine because, like the Women’s March, this walk wasn’t about reaching some predetermined destination. It was about simply encouraging people to walk—and understanding why they don’t.

The walk took place in Pearl City and was organized by Colby Takeda, a young, clean-cut O‘ahu native who works for The Plaza Assisted Living, a group of senior housing facilities on O‘ahu. It was one-part art project, one-part public health initiative. Students from the Center for Tomorrow’s Leaders, a leadership program for high school juniors and seniors, accompanied Plaza residents on short walks through their communities, documenting the experience with digital cameras. After, the residents talked about what they photographed, and discussed whether or not they considered the neighborhood “walkable.” Takeda hoped the walks would put the youth in the kūpuna’s shoes, and also generate ideas for how to make O‘ahu’s streets safer for pedestrians.

The project was also part of Jane’s Walk, a global movement of “citizen-led walking tours” inspired by Jane Jacobs, the bespectacled urban thinker who wrote The Death and Life of Great American Cities . Jacobs believed that “cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” Jane’s Walk got its start in Toronto in 2007. Since then, it has expanded to more than 200 cities. Thousands of Jane’s Walks take place every year, exploring everything from the rich cinematic history of Santos, Brazil, to the unique roji (alleys) of Tokyo.

WHAT MAKES A NEIGHBORHOOD “ WALKABLE? ”

- a main center

- enough people

- affordable housing

- buildings close to the street

- schools and work nearby

- streets designed for bicyclists, walks, and transit

WHAT MAKES WALKS SAFE FOR PEDESTRIANS?

- streetlights

- clearly marked sidewalks

- well-timed crosswalk signals

- protected intersections

Honolulu’s first Jane’s Walk took place in May 2014. It was organized by Matthew Gonser, a co-founder of the community advocacy group Better Block Hawaii, and who is now with the Honolulu Office of Climate Change, Sustainability, and Resiliency. Gonser has been advocating for a safer, more walkable Honolulu since he moved to the city in 2012. Two years ago, he organized a Jane’s Walk to raise awareness about pedestrian safety. Participants—a mix of designers, planners, interested residents, and city employees, including the deputy director of Honolulu’s Department of Transportation Services— walked from Alapaʻi Street to University Avenue, intentionally crossing King Street at each un-signalized, mid-block crosswalk (which is striped, but does not have a stoplight). The aim was to demonstrate how treacherous these types of crossings are, and to encourage the city to take action. Honolulu has a mandate to make the city safer for pedestrians. Amended in 2006, the city’s charter states: “It shall be one of the priorities of the department of transportation services to make Honolulu a pedestrian- and bicycle-friendly city.” And yet, according to Hawai‘i Department of Transportation reports, pedestrian deaths have continued to rise in Hawai‘i, by as much as eight percent between 2014 and 2016. This year, the city banned looking at a cell phone while crossing the street, a law most experts agree unduly punishes pedestrians. “You, as a person walking, are such an easier target for enforcement,” Gonser says.

The people most affected by Honolulu’s poor walkability are the homeless and the elderly. According to one study released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which looked at Clark County, Nevada, homeless people were killed in pedestrian deaths at more than 20 times the rate of residents and visitors. In Hawai‘i, seniors who walk are at nearly three times the risk of being killed in a traffic accident when compared with the rest of the country, according to national statistics.

At Takeda’s walk in Pearl City, the deficiency of Hawai‘i’s built environment was apparent. Watching residents like Carl, a small, mostly silent gentleman who shuffled down the street using a walker, it was clear how unwelcoming the built environment can be for the elderly. For instance, the crosswalk nearest the Plaza was almost 700 feet away, at the bottom of a hill. If a person wanted to walk to the shopping center across the street, he or she would have to walk down to the crosswalk, cross, and walk back uphill. At an average pace, it would take about 10 minutes, an annoyingly long time to get somewhere right across the street, but doable. If you’re Carl, it’s out of the question. It would take him roughly half an hour just to reach the crosswalk, and longer to complete the opposite leg. That’s an hour’s walk to get from his home to the Sam’s Club across the street.

Later, when the group shared their photos, it was one of Carl’s that struck me as the most profound. Taken from about chest high, the slightly blurry photo was almost certainly an accident. In it, you see his walker, his laminated nametag affixed to the plastic handlebar, and his slippered feet on the sidewalk. What stood out to me, however, were the walker’s wheels, one of which was in the grass. It turns out that the sidewalk in front of the Plaza isn’t even wide enough for two people to walk abreast, certainly not when one person uses a walker or a wheelchair.

Most experts agree that the best way to reduce pedestrian deaths is to rethink our streets. Wide streets with infrequent intersections naturally encourage drivers to go fast, regardless of the posted speed limit. The faster the traffic along a particular roadway, the less pleasant and safe it is for pedestrians. A human body has a 93 percent chance of surviving an encounter with a motor vehicle traveling 20 miles per hour. But if that car is going 45 miles per hour—not uncommon on a wide street like Ala Moana Boulevard—the survival rate drops to just 40 percent, or 17 percent for the elderly.

There’s something rewarding about exploring the world on foot and realizing so much of it is, in fact, open to you. You can linger at streams and loiter in public plazas. You can walk to the edge of the city, and simply keep going.

� Walking has been shown to reduce stress, improve sleep, and generate economic activity. The challenge for Honolulu is to design communities more attractive for and encouraging of pedestrians.

To slow traffic speeds, cities around the world are implementing “road diets,” adding traffic-calming measures like speed humps, narrower lanes, traffic circles, raised crosswalks, and trees planted along the street. Coincidentally, elements like these also often improve the pedestrian experience, and not only by increasing the chances of surviving a walk to the grocery store.

Recently, walking advocates got another arrow in their quiver. In December 2016, the New York State Supreme Court ruled that cities, and not just drivers, can be held liable for vehicular incidents. The decision, in which New York City was found 40 percent liable for an accident involving a speedy driver and a bicyclist, and was ordered to pay $8 million to the defendant, is one of the first to recognize that a city’s physical form directly affects the behavior of its drivers.

A city’s form also affects whether and where we walk. Pedestrians naturally gravitate to the shady sides of streets, as well as to areas with other pedestrians. If Honolulu wants to encourage walking— and it should, given that walking has been shown to reduce stress, improve sleep, lower a person’s risk for Alzheimer’s, and generate economic activity—it will have to rethink its streets and public spaces. “I don’t think you can just poke at people and say, ‘I’m encouraging you to walk more,’” Gonser says. “We have to work on the physical environment. We have to make it appealing.”

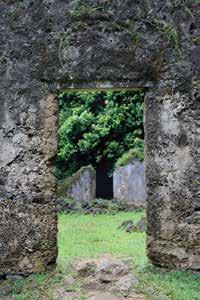

Solnit says you never really know a place until it surprises you. One of the most surprising places I’ve discovered while walking in Honolulu is a hidden stairway off Magellan Avenue above the H-1 freeway. It’s at the edge of a small, bowlshaped park almost completely enclosed by tall rock walls, with a boarded-up field house and a solitary, plastic playground. Like the park, the stairway feels leftover. No path leads to it. It simply starts at the

edge of the grass, its stone steps curling around a massive banyan tree whose roots form spaces littered with trash and broken bottles. Near the top, the stairway narrows to a dark channel as it cuts into the cliff. Then it opens, suddenly, onto a large, graffitied basketball court.

I’ve walked the stairway multiple times, and each time, going from the dark, enclosed cavern of the tree canopy to the exposed expanse of asphalt, feels like stepping through a portal. Such distinct shifts in the city’s urban fabric often happen between neighborhoods, or between streets. These two spaces, on the other hand, create a sort of friction in their adjacency.

Henry David Thoreau, America’s most famous literary walker, wrote, “Two or three hours’ walking will carry me to as strange a country as I expect ever to see.” I suffer from the same mild wanderlust. While I feel only the smallest compulsion to book flights to foreign countries, I feel a strong pull to walk the places I call home, and have a toddler’s tendency to wander off. It has, I think, something to do with freedom. In modern society, even walking down a street that isn’t yours can feel like trespassing. But there’s something rewarding about exploring the world on foot and realizing so much of it is, in fact, open to you. You can linger at streams and loiter in public plazas. You can walk to the edge of the city, and simply keep going. Without engines, gears, axles, we discover that more is possible, not less—there is a sense of empowerment in recognizing that we are freer than our departments of transportation would have us believe. Sidewalks become dirt paths, which become wilderness, and still we can walk, constrained by nothing but our own physical capacity.

This freedom is what is being enacted when we march. To walk in a place is to reclaim it, even for a moment. These small reclamations have set in motion entire reorderings of nations. At some point, a long time ago, human beings figured out that by simply walking, they could change the world. One foot in front of the other, until nothing is as it was.

Honolulu Mililani Mauka 15

POPULATION

337, 256 Mililani Mauka

21 ,039

Downtown Honolulu

*From walkscore.com.

� A one-mile walking radius in downtown Honolulu, Hawai‘i’s most walkable neighborhood, and Mililani Mauka, O‘ahu’s least, where almost all errands require a car.

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

With one of hula’s most athletic and ancient dances, the men of Ke Kai O Kahiki excavate the fundamentals of the form’s multi-layered tradition.

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF IMAGES BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

� Kumu hula La‘akea Perry and dancer Sunny Leutu.

Ahand slices through the air. In concert with the foot, leg extended and parallel to the arm, it thrusts forward in a precise and steady motion. Matching the hollow thud of a wooden gourd, hands and feet travel to the absolute reaches of their limbs, return to center across the mouth and groin, then repeat, one, two, three. Suddenly, the hula dancers, all men and all in recline, rise from the ground in a single sweeping motion, bodies hovering above the terra firma, balancing themselves confidently on a single arm and foot. Uprooted, they sway, ebbing and flowing, accelerating to a crescendo of eruptive backbends, their necks and shoulders flexing just inches from the ground as their sculpted bodies quake like mountains of their own making.

This is hula ʻōhelo, a brisk and energetic dance that is rarely seen today. At Lanikūhonua, a parcel of land on Oʻahu’s west side where Ke Kai O Kahiki trains, the male hālau performs its impressive and peculiar movements to the percussive chant “Tū ʻOe.” The kāne, men who range in age from their 20s to 30s, aim to perfect the pulsing rhythm of this ʻōhelo, the distinctive “seesaw” of the dance (also the meaning of the word, ʻōhelo), before progressing into even more complex floor work. One doesn’t have to be fluent in hula’s nuances to gather that it is an especially difficult and disciplined dance. To the modern eye struggling to make sense of its motions—the pointed toe angled at a concise degree; the palm, turned downward and flexed; the seismic swing, all which carry meaningful weight— the dance recalls a mix of CrossFit and ballet. Its gestures clearly strain the body. When Ke Kai O Kahiki first performed “Tū ʻOe,” for the kahiko night of the Merrie Monarch Festival in 2009, it blew open casual notions about what hula is and what it looks like by employing explicitly athletic and relentlessly masculine motions. With it, the hālau swept the competition, winning the year’s coveted overall title and becoming an instant Merrie Monarch classic. It is watched and re-watched by hula enthusiasts the world

over to this day—an online search for it is easy to find (it’s the video with more than 1.5 million views on YouTube). What is more notable, though, is that it reveals the excavation of dance movements many spectators had not even known existed in the canon of hula. “The motions were so unusual, learning it for the first time was like wiping the slate clean,” says Laʻakea Perry, who was the lead dancer at front and center during that performance eight years ago. Even with two decades of hula experience to his name, all spent under the tutelage of Ke Kai O Kahiki and the late O’Brian Eselu, its founding kumu hula, Perry initially found the ʻōhelo strange and uncomfortable. The unfamiliar steps, strung into exacting sequences and requiring constant adjustments to refine, test a dancer’s agility and strength. “We trained one year for that ʻōhelo,” Perry remembers. “In all my hula learning, the dance and its movements were something I’d never done before, and now I’ll never forget how to do.” Backbends combined with continuous ʻami, or hip rotations, for eight counts, for instance, elicit fevered applause from hula fans, in awe of the hālau’s ability to make such technical floor work appear so easy. In hula ʻōhelo, one misstep and the dancer is exposed, with no time to cover any flaws.

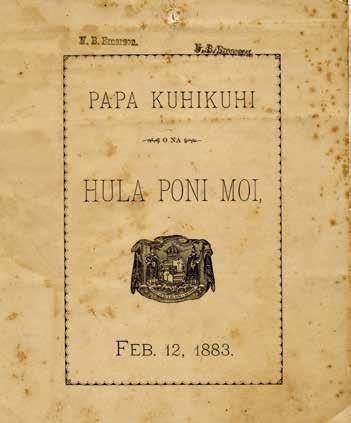

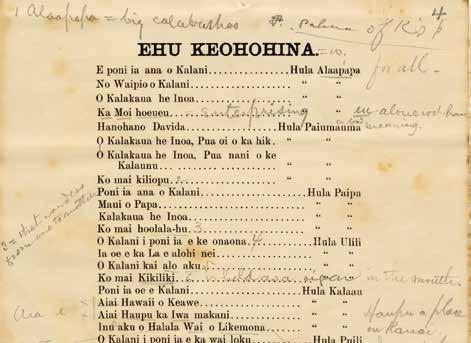

Prior to its Merrie Monarch debut, the last documented public performance of hula ʻōhelo may have been more than 150 years prior. In a brief chapter in the early 20th century tome Unwritten Literature of Hawaii, historian Nathaniel B. Emerson transcribes a vague account of its display to the year 1856 in ʻEwa (coincidentally the same general area of Oʻahu where Ke Kai O Kahiki is based). It’s accompanied by a mele maʻi, or a procreation chant, which celebrates the proliferation of future generations of aliʻi. But, even without this awareness, the viewer is coaxed toward the dance’s fertility themes by the gestures themselves: the men, minimally clothed, are in recline; the leaned body pushes, prods, thrusts; the finale peaks with a tantric climax. “The whole action, though fantastical, was conducted with modesty,” Emerson concludes.

To the modern eye struggling to make sense of ancient roots, the dance recalls a mix of CrossFit and ballet.

� Dancer Julian A. Maeva demonstrates the starting movement in hula ‘ō helo, a peculiar style atypical to other hula noho, or seated dances. From here, the progression goes from simple to complex.

Reawakened is perhaps a better word than rediscovered when tracing the trajectory of hula ʻōhelo from past to present. Like many Hawaiian customs suppressed under missionary authority, hula continued to persist, albeit more secretively, through unwavering practitioners. Its spiritual and ritualistic nature, incongruent to the conservatism of the century’s new societal influence, left hula at constant risk of erasure; because of its strong sexual connotations, the genus of hula ʻōhelo was potentially even more vulnerable. Pair this with the form’s sheer archaism, even during Emerson’s time (“It is safe to say that very few kumuhulas have seen and many have not even heard of the hula ʻōhelo,” he wrote), and its movements grew increasingly austere with each passing generation. Even in the hula ‘ōhelo that has survived, the manner in how the hands follow the feet—in “seesaw” with with minimal interpretation or allusion to the chanted text—highlight a hallmark of its antiquity, according to Taupōuri Tangarō, a kumu hula and the director of Hawaiian culture and protocols engagement for the University of Hawaiʻi at Hilo and Hawaiʻi Community College. Tangarō first encountered two hula ‘ōhelo dances in the 1980s, one for the ʻipu (gourd), the other for pahu (drum), on the heels of the Hawaiian Renaissance as a 19-year-old student of Hālau O Kekuhi, the regarded Hawaiʻi Island hula company founded

by Edith Kanakaʻole. The dances, he was informed, are related to fishermen returning home from cold nights at sea, who would warm themselves by dancing around a fire. Traditionally, this is how hula ‘ōhelo was danced— imagine now a circle and a corona of limbs stoking a flame—a formation that still has yet to be revitalized. “By design,

hula ʻōhelo is not soft and feminine, but sharp and masculine,” Tangarō says, suggesting that ‘ōhelo’s orientation toward the fire, a central and archetypal symbol for the sacred feminine, had a multi-tiered significance. “By doing it in the presence of the fire is to offer up again an intercourse of the male energy of the dance and the female energy of the fire. This is

potent, the balance of male and female, in many oceanic indigenous religions.”

When Eselu first heard of hula ‘ōhelo it was through word of mouth in 1985. He was 30 years old, still an emerging kumu hula himself, and became determined to learn it. Eselu sought his source, Nālani Kanakaʻole, the daughter of Edith, to gain proper information on the dance; Nālani still retained knowledge of hula ʻōhelo and its rarefied movements, in the tradition of Samuel Pua Haʻaheo, a hula master from Kahana Valley. It was Nālani’s husband, Sig Zane, who provided crucial details on certain hand motions identifying the lesserknown male version. But it wasn’t until he founded Ke Kai O Kahiki, his all-male hālau over a decade later, that timing would strike: Haʻaheo, it turns out, is also the great grand-uncle of Perry, Eselu’s star hula student. Together, the two had the privilege to continue this familial dance tradition. “That dance that year at Merrie Monarch was very special and important for me, and for O’Brian,” Perry says, “as it was a way for me to pay tribute and represent my ‘ohana.”

Under Eselu, the two commenced in reanimating the ʻōhelo for the world’s largest and most visible hula stage. Eselu’s guiding vision for his all-male troupe was to push the boundaries and biases about men

who practice hula—a sentiment that culminates in the hālau’s hula ʻōhelo, which emphasizes fluid hip movements combined with ‘ai haʻa, an emphatic class of hula that involves dancing very low to the floor, often in a stout, full-squat position. “Our style is often described as bombastic, as very strong, almost mimicking or replicating martial arts and Hawaiian lua, very warriorlike,” says Perry, who is now the kumu hula of Ke Kai O Kahiki, and who continues this dance tradition passed down to him by Eselu. “But if you look deeper into the style, it’s not just about the masculine look of it. There’s another level beneath there, where you can see the connection between its manly side and its softer side.”

To prepare for the dance, training is grueling. Hours of attention are dedicated to hula basics. The men also turn the landscape of Lanikūhonua into their conditioning gym: They climb coconut trees as quickly as they can; do duck walks across the length of its 10-acre fields; run drills on the sandy beach that fronts the property and along the ocean floor, weighing themselves underwater by carrying heavy boulders in their arms. “We have to reshape our bodies to do this dance,” says Sunny Leutu, who, after Perry, is the longest dancing hula member of Ke

Kai O Kahiki. Those who are unready often fail to complete it. “Your body is burning to that point, and every time you start feeling that pain, you give up, and ruin the dance,” Leutu says. “But when your muscles gave out, that’s when you’d find out how far your mind could take you. If you let your mind push your body, it’s really about mind over matter, telling yourself, ʻFinish this.’ You get stronger and stronger every time.”

Hula’s code prides, above all else, a story. Its rousing athleticism is neutered when disconnected from the movements its dancers strive to enliven, because hula, in its physical traffic of symbols and metaphoric imagery, inundates the viewer with richly detailed accounts of gods, of nature, of its people. Its dance gives literal shape to the oral tradition on which it is based—no step, bend, nod, or sway is arbitrary or ornamental. To lose a chant, a dance, or even a single movement, is to lose more than mere choreography; it is to sever a connection of the Hawaiian people to a sacred realm and identity so elemental to the soul of the islands. Under this context, consciously or unconsciously, hula ʻōhelo electrifies what makes hula so affecting at its core in this present day: to witness the power and poetry of reclamation in motion. On the lawn of Lanikūhonua, the kāne near the end of their hula ʻōhelo. Their levitated bodies draw back to where

they began, settling back down into the soil, one again with the earth. Their kumu chants the final phrases of the dance, and the energy between he and his students swells with an unseen cosmos of an ancient tradition passed down for centuries. The kāne, whose hands have now turned into fists held

at their waists, station themselves and gaze ahead. Still as the sea behind them, they wait on the kumu’s command to break this pose. For their hands and their arms, to once again, slice through the air. To wield their bodies and reach back into history. They will move to show that all is not lost.

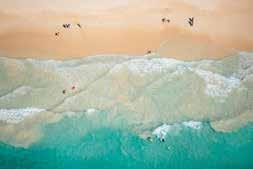

One writer discovers her own strength while paddling through currents of the sea.

BY MARTHA CHENG

BY JOHN HOOK

There are days when I can move no farther than the 400 square feet of my Mānoa apartment. And then there are days when I set out to cross the 32 miles between Moloka‘i and O‘ahu on a prone paddleboard.

I am not an athlete. I am definitely not an endurance athlete. These are things I told myself for most of my life. Until, one day, I decided to cross the Kaiwi Channel just to prove that I could. It started with such a small thing: a race to shore after a surf session at Secrets on O‘ahu’s southeast coast. I beat my friend, who had crossed the Kaiwi many times before. “Maybe paddleboarding is your new sport,” he said. “Maybe you should do the Moloka‘i-to-O‘ahu.” He dropped the comment as casually as a child brushes sand off her feet.

But nothing is as small as it seems. The tiny wave lapping at your toes is the accumulation of energy that has traveled a long distance. A shift in tide, barely noticeable to those who aren’t watching, is caused by the moon, a very large thing.

The day I decided I would cross the channel, I had erased things that didn’t seem small: a husband, a home, a job. I could tell you

the reasons why, but I would not know if they were true. Or maybe they are all the truth. Perhaps what matters, is in that moment, I felt like a different person than before I had entered into those contracts.

Surfing was partly to blame. I had fallen into the sport a few years before, and it had unearthed a physicality in me that I had always suspected but never known. I had always been the girl too nerdy and too small to be chosen for anyone’s kickball team. I had always wanted to play, to climb, to swim, but often, when I got to the top, I was too scared to come down. Once, at the Disneyworld pool, I swam too far, and the lifeguard had to rescue me.

I first tried surfing in the middle of a snowy New England winter, but for the entire season, I tumbled endlessly in the cold water. I tried again shortly after I moved to Hawai‘i in 2006, but I got in the way, got yelled at. So, I stopped. I lived in Hawai‘i for six more years before a friend introduced me to a break where the waves, and the people, were friendly. And then I went every day. I came to know the surfers in the lineup. I stayed in the water until the moon rose and sent a silvery beam along the water

straight to me, as if giving me a path. I grew comfortable in the sea. For the first time in three decades, I finally felt at home in my own body, with the figure I had thought was too skinny, too flat, that looked awkward in a bikini. I grew to love my body and the way it felt in the water. I became the most confident and happy I had ever been.

When people talk about surfing, they speak of its meditative nature and of the healing properties of the ocean. But surfing is also extremely addictive. Maybe, in the end, all things we enjoy become addictions. I couldn’t get enough. I let work and friendships and relationships slide. At first, I loved having this separate world. Then, it became my only world.

I soon found, though, that once I loosened myself from my contracts, the new world that once felt so alluring—the one without the job, the husband, the home—became empty and frightening. I was the child back in the middle of the pool, unable to go forward or back, afraid I would drown. And so, paddling the channel became something to do when I didn’t know what else to do. It became something to define me when I had lost my identity.

Through surfing, I learned the basics of the ocean: tides, swell, wind. Through paddleboarding, I learned its language, by way of intimacy and isolation. There are few places these days where you can surf alone; with paddleboarding, you are often alone. When prone paddleboarding, you lie or kneel on a long, narrow board that’s like a cross between a canoe and surfboard and propel yourself with only your arms. Pulling myself through the water this way feels like crawling across the surface of the sea, giving me time to study the bumps in the water, the curves of the coastline.

On 17-mile training runs from Makai Pier to Kaimana Beach, I observe the water at its moodiest. Around Makapu‘u Point, waves from every direction try to buck me off my board. Here, the water is a deep, dark blue that I want to linger in forever, if I weren’t too afraid of what else lingers there. I know that off the coast of Alan Davis Beach, the waves begin to line up. Delirious laughter escapes me as I find their rhythm. I know that a little farther, past Hanauma Bay, the water will feel violent, crashing against the coast so forcefully I can hear nothing else, but that there may be a little current right along the cliffs that will push me in the direction I want to go. By the time I get to Black Point, the seas are calmer, and the water has a stickiness, as if refusing to let me go. And then, rounding the corner of Diamond Head, I see the lighter blue of Waikīkī, like that of a lover’s eyes, the sign that I am home.

In 2016, I completed my first Moloka‘i-toO‘ahu crossing with a partner who was skilled in the ocean, and was comfortable in the water whether on a surfboard or aboard the Hōkūle‘a . We built our love on the water, and the race was a culmination of our passion. It was an adventure, full of excitement. When we broke up, I thought I was done with paddleboarding, but I found myself signing up for the race the following year, this time with a different partner, who was new to the channel. After a few months of training, I was filled with dread. Preparing for a race is like falling in love: The first time, you revel in the beauty and exhilaration of the experience. The second time around, you know challenges await, and so might heartbreak.

Now in its 22nd year, the Moloka‘i 2 O‘ahu World Championship race is reputed

I continue paddleboarding not because I like suffering and pain, but because I love the ocean, and who I am when I’m in it. It brings to the surface an endurance I didn’t know I had.

�

Martha Cheng writes of a love affair with the water that has both informed and influenced the way she understands herself and her relationships.

to be the most challenging paddleboard event in the world because of its deep and turbulent path. Kaiwi means “the bone,” a reference perhaps to its history of swallowing sailors and spitting up their corpses along the southeast shores of O‘ahu. This is the channel that claimed renowned waterman Eddie Aikau. This is the channel where winds of 30 miles an hour can whip up 20-foot waves. But somewhere between stormy and flat is the sweet spot for paddleboarders.

Every activity has its own way of engaging the ocean, depending on the vessel or purpose. When I am surfing, I love glassy, windless days. But when paddleboarding, I want the wind, which creates waves along the water’s surface that help carry me home. For a race like the Moloka‘i 2 O‘ahu, catching these “bumps” the entire way is ideal—to sprint into the wave, and then relax into it. Sprint, relax, sprint, relax.

Last July, while the elite athletes were nearing the Moloka‘i 2 O‘ahu finish line, breaking records and completing the race in less than five hours, my partner and I struggled as we felt the tide turn, literally. Four hours into the race, it switched and dropped, pushing us away from O‘ahu. I felt my arms and the minutes drag. Yet each time I jumped into the water to switch off with my partner, I let the water close over me, and in the silence and weightlessness of the ocean, I thought, I am lucky to be here. I am happy to be here. Finally,

we crossed. It had taken us 7 hours 49 minutes.

I continue paddleboarding not because I like suffering and pain, but because I love the ocean, and who I am when I’m in it. It brings to the surface an endurance I didn’t know I had. It makes things that once seemed insurmountable—like a 10- or even 17-mile paddle—

manageable. For me, it is the disciplined and competitive yang to the carefree and graceful yin of surfing. Each stroke, every time I put my hand in the water, is such a small movement. But together, they have become the parts of me that I like. And that is no small thing.

Inspiration strikes in a number of ways. Get in the mindset of a diverse cast of characters to find out what pushes them forward.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & LILA LEE

“Boxing is 90 percent mental. You have to be smart and always think ahead.”

In 2014, when Bree Locquiao dropped in on a boxing fitness class at the UFC Gym in Waipahu, boxing instructor Carlos “Nito” Tangaro immediately saw potential in the former collegiate soccer player. Over the next few years, the spry 5-foot1-inch boxing newcomer honed her skills in the ring, becoming a quick study in footwork and combos. In a sport where focus, force, and speed are critical, a strong mind game is tantamount. Her deadly combination of natural athleticism, grit, and discipline resulted in triumph: In 2017, Locquiao became the first female flyweight from Hawaiʻi to be crowned a national Golden Gloves champion.

BREE LOCQUIAO BOXER

RYAN

“Motion is important to me, not just for my lifestyle, but my life, as well.”

In 2008, triathlete Ryan Leong walked into his doctor’s office for a routine checkup, and walked out with sobering news. Leong, who had heart surgery a decade earlier, was told he had developed “stone heart,” or ischemic myocardial contracture, a rare heart condition in which the pericardium (the sac surrounding the heart) restricts the heart from expanding correctly. So the 45-yearold did what he’s always done: He kept moving. Leong’s affinity for triathlons—specifically, the Ironman races, with their 2.4-mile swims, 112-mile bike rides, and 26.2-mile runs—is eclipsed only by his appetite for the intense, physical training

demanded by them. Through it all, his heart pumps strong. Though doctors suspect that Leong’s robust cardiovascular system staves off his heart’s calcification, Leong remains nonplussed by his diagnosis, preferring instead to focus on the requirements of the sport’s arduous nature: The grind of training is gratifying, and he loves pushing his body to the limit.

KAMEHAMEHA SCHOOLS ’

K Ā PALAMA HIGH SCHOOL

GIRLS ’ TEAM

RUGBY

“Unlike being hit, to hit someone else feels amazing. If your technique is right, you can stop anybody coming your way.”

On the field, the Kamehameha School’s high school girls’ rugby team is a delightful exercise in cognitive dissonance: a group of teenagers giggling together one moment, and then colliding in brutal, physical combat minutes later. Though naysayers decry the sport as too violent for females, or worse, unladylike, the rugby girls of Kamehameha have found confidence and beauty in the sport’s physicality— running, rucking, scrumming, and tackling. “You may get a couple of bruises on the shoulders or a hit to the face, but nothing is better than preventing a score, and to be honest, taking a girl down to the ground,”

says Cameron Pagador, team captain. No one likes getting hit, the team unanimously agrees (the girls are taught proper response techniques to prevent injury), but hitting an opponent does have a raw, visceral appeal.

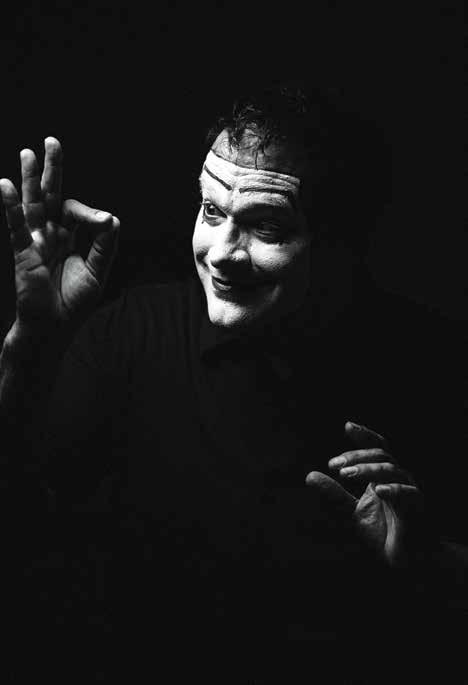

TODDFARLEY MIME

“Through mime I can tell stories that go beyond words, stories that are common to all human beings regardless of culture and language.”

Todd Farley spent his childhood swimming in waterfalls and playing barefoot deep in the rainforests of Hawaiʻi Island. Upon moving to Grandview, Washington at 13 years old, he struggled with mainland speech, manners, and customs. It was the late 1970s and mime was all the rage, recalls Farley. When his church, Grandview Christian Center, started a mime troupe as a form of evangelism, the theatrical art offered a lifeline. For an island-raised boy who spoke Pidgin English, miming was a perfect medium: It required no talking. When he was 17, Farley took his one-man show on the road across the United States, the Bahamas, and Israel, culminating in an invitation to

study under renowned mime artist Marcel Marceau in France. Farley, who has since returned home to Hawai‘i, teaches mime at University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa’s Outreach College, and is working on his opus, a grand retelling of Hawaiʻi Island artist Jerre Tanner’s painting “Boy with Goldfish.”

PAULO LINHARES DA SILVA CAPOEIRISTA

“Capoeira is the only martial art where, when you are doing it, you are smiling.”

Paulo Linhares da Silva, better known as Mestre Kinha of Capoeira Besouro Hawaii, grew up in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, where his parents enrolled him in a capoeira school when he was 7 years old; they were concerned about the violence of the favela in which they lived. The young capoeirista took away more than self-defense, going on to become Rio de Janeiro state capoeira champion in 1991. In 1994, da Silva was given the title of “mestre,” conferred upon those who attain a high level of excellence in the martial art. In accordance with tradition, he chose his nickname, Kinha, to accompany it. Moving to Hawai‘i in 2001,

da Silva brought his love for the sport with him. At his two capoeira academies, on O‘ahu’s east side and in Kaka‘ako, da Silva and his students practice to the upbeat sounds of the berimbau , a musical bow, and the atabaque , a hand drum that keeps the beat. Their swift movements are intensely physical, and the dance-like connections between capoeira players are equally personal. “In capoeira, it is about making the other person feel good,” da Silva says. “You think about the other person and make them feel comfortable. When you finish, you then feel proud about yourself and you feel happy toward your partner.”

JACKIEGRAESSLE SKATEBOARDER

“Skateboarding juxtaposes joy and peril, and therein lies its attraction for me.”

Jackie Graessle’s sunny disposition extends to her outlook on learning new skills. After watching (and rewatching, at least 30 times) Dogtown and Z-Boys , a 2001 documentary featuring a rag-tag collection of gritty Venice Beach street urchins who revolutionized skateboarding in the 1970s, Graessle, a social worker, was inspired by the sport’s subculture spirit. She decided that she wanted in. She was 62 years old. “I just see it and think I can do it,” says Graessle, a year later. Enlisting the help of Nainoa Andrade, a local skate instructor she procured online, Graessle finds joie de vivre via deck, trucks, and wheels. “I feel a profound

sense of exhilaration when I am in the moment, flying along,” Graessle says. At her home park in Kāne‘ohe, where she skates four times a week, she has also found a tribe of fellow skaters who share her sentiment: Stoke knows no age.

FLUX FEATURE

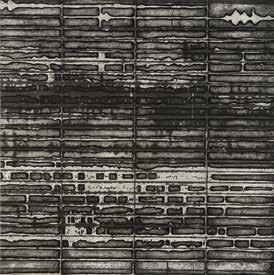

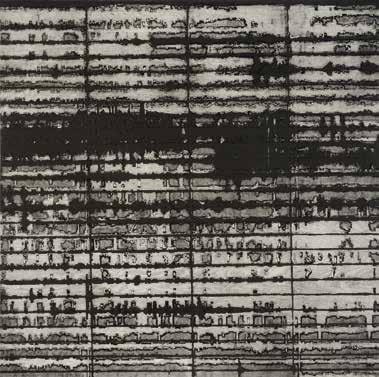

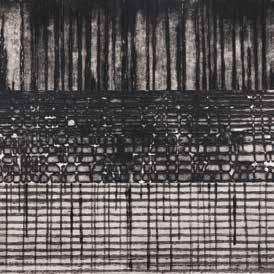

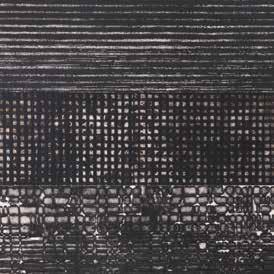

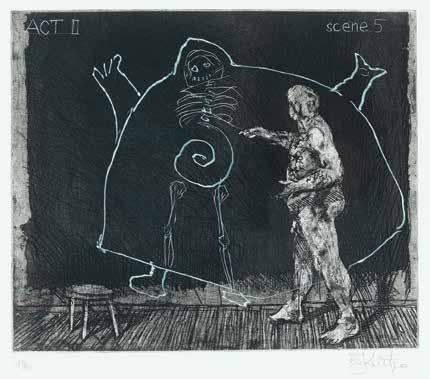

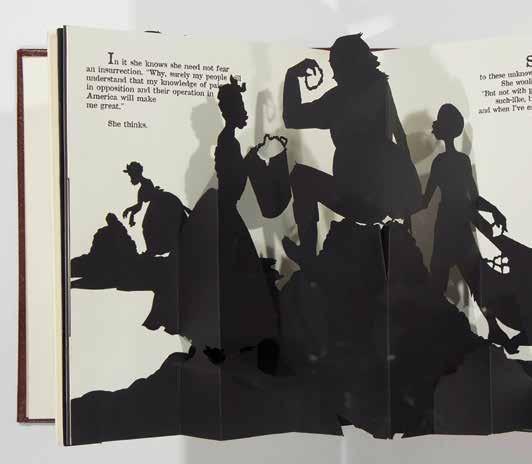

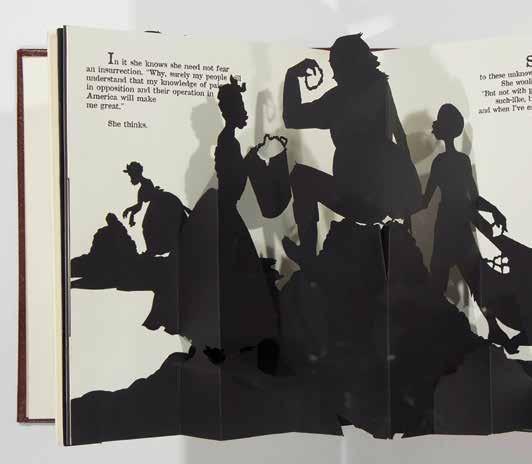

Two printmakers, Charles Cohan and Abigail Romanchak, teacher and student in no particular order, recount the path that led to their past and upcoming collaborations.

TEXT BY ABIGAIL ROMANCHAK & CHARLES COHANCOHAN IMAGES BY JONEL JUGETA ROMANCHAK IMAGES BY JOSE MORALES

ON CONVERGENCE:

� Charles Cohan: In 1952, Carl Jung published Synchronizität als ein Prinzip akausaler Zusammenhänge, or Synchronicity: An Acausal Connecting Principle, which states that events are “meaningful coincidences” if they occur with no causal logic, yet are meaningfully related. A favorite and enduring example of this phenomenon in the arts refers to the invention of photography in the 1830s, when unbeknownst to each other, Louis Daguerre was doing research in France that coincided with the experiments of Henry Fox Talbot in England.

The most profound example of this occurrence in my personal experience took place at noon on May 3, 2017, when Abigail Romanchak sent me a set of images that were eerily simultaneous to a body of work that I was developing. Through immediate phone calls, texts, and emails, it became clear that we were traveling a common path in our creative directions. Thus, the 9-foot by 20-foot print installation Converge , our collaboration for Ground , my solo exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art, was born.

� Abigail Romanchak: Reflecting on these collaborations with Charles Cohan, my former printmaking professor, brings to mind an interview I heard on Krista Tippett’s podcast, “On Being.” The guest was author Elizabeth Gilbert. At one point, Gilbert recounted a time she and another writer, Ann Patchett, had the exact same idea for a novel without even knowing it. Gilbert then described how she believes ideas are conscious, living things,

which possess a great desire to be manifested, and that they spin through the cosmos looking for human collaborators.

At the time, I thought this sounded wonky. But then, I had a very similar experience. In April 2017 I was invited to be part of a Smithsonian-sponsored pop-up culture lab in Honolulu. For it, artists were asked to respond to the concept of ‘ae kai, or convergence of land and water. I interpreted this theme quite literally, and decided to work with seismograph readings and harmonic tremor printouts from Kīlauea Volcano on Hawai‘i Island. I wanted to explore how the origins of new land converge with existing coastal landscapes. But as I began to carve, I realized that these intricate, large-scale woodcuts would pose too great a technical challenge for me to tackle on my own. So I emailed Charlie images of the carvings I had worked on, and asked if he would assist me. To my surprise, I received a call from him within 10 minutes of hitting the send button. “Abbey! You’re not going to believe how similar my new body of work is to the seismograph images you just emailed me,” he said. He agreed to help print the woodcuts, and asked to talk soon about a future collaboration.

� Cohan: Since my arrival at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa in August of 1994, I have worked with more than 1,000 undergraduate and 25 MFA students in the printmaking studios of the department of art and art history. Abigail Romanchak is one of a few of my former students who have provided the most significant

contributions to the identity and culture of the printmaking program. Abbey and I have shared four stages in our artistic relationship. First, I was her professor as she earned her BFA and MFA degrees. We were then fellow printmakers, before working together as collaborators. Now, Abbey has transcended the student-teacher duality, overturning this paradigm into the full cycle of teacher as student, student as teacher, exposing the power of this dichotomy and its inversion. Qualities of weight, density, texture, and the indelibility of the printed mark remain a shared aspect of our work. The visceral approach that we take, conveyed through the transfer of ink from plate to paper via sheer pressure, is a thread that ties together our collective graphic sense.

� Romanchak: Charlie remains youthfully enthusiastic and open, despite his high level of success and sophistication. He is a worldrenowned artist—idolized by his students and highly respected by his colleagues—who enjoys skateboarding with his son. I was grateful for his help, and humbled by the invitation to collaborate. Yet, I was also ambivalent. Creating as a team would be difficult with anyone, let alone my mentor. Could we really work on equal terms? What could I contribute to the process when he was used to hand-carving his own doorsize wood cuts, perfectly registering a 20-color screen print, and building his own custom frames?

Converge , Abigail Romanchak.

Converge , Abigail Romanchak.

� Cohan: My prints in the Converge and Ground series are carborundum and glue collagraphs. The collagraph process was mutually invented by a few printmakers during the 1970s print culture in the United States, including Edward Stasack and Lee Chesney, who were UH Mānoa printmaking professors at the time. Collagraphs are prints made using a collage-based process of attaching physical textures in a range of materials to the printing plate with various varnishes and adhesives.

� Romanchak: To make my Converge prints, I traced images of seismograph readings onto five different sheets of 30-inch by 30-inch birch plywood. Then, using a variety of tools, I carved away the negative space. In June 2017, Charlie flew from O‘ahu to the Hui No‘eau Visual Art Center printmaking studio on Maui to help me print my work for ‘Ae Kai , the exhibition put on in July by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, and Ground , Charlie’s solo exhibition at the Honolulu Museum of Art, for which we are collaborating on the Converge installation. Due to the size and intricacy of my carved woodcuts, it was most helpful to have an extra set of hands applying ink, wiping, and printing the woodcuts. While in the studio together, we pinned up our finished prints, imagining how they might look tiled

next to each other in ‘Ae Kai . A month later, I flew from Maui to O‘ahu with 20 different 30-inch by 30-inch prints. The day before the opening of the ‘Ae Kai exhibit, Charlie and I spent an afternoon together in an empty art studio at UH Mānoa rearranging our prints on the ground, until we were satisfied with a final composition for our 9-foot by 20-foot installation.

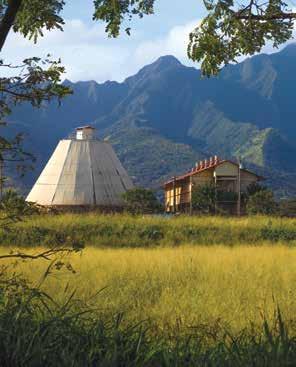

� Cohan: Twenty years into our relationship, I am increasingly inspired by Abbey’s commitment to the issues particular to Hawai‘i, the relevance her work has acquired in the Hawaiian cultural community, and her evolving recognition as one of Hawai‘i’s most important visual artists. We celebrate our mutual connection to volcanic formation, earth movement, the creation of landmass, and the existence of islands and mountains in general. For Abbey, this is the Hawaiian Island chain. For me, it is the Cascade Mountains of the Pacific Northwest. Inspired by these two locations, the collaborations presented in ‘Ae Kai and Ground attempt to graphically translate the forces of geophysical change, including sedimentary compression, geologic weight, and the occurrences of seepage, fracturing, slippage, failure, and layering: the geothermal and hydraulic meeting of rock and water; fluid or frozen, hot or cold.

� Romanchak: Our collaboration for ‘Ae Kai was influenced by the continuous breathing of a volcano. My prints drew from the sustained release of seismic energy typically associated with the underground movement of magma, while Charlie’s prints referenced a graphic reverb of the movement of ground. I am still awed that Charlie and I had such similar concepts at the same time, and that our prints came together so seamlessly. I like to think our ideas weren’t really ours, after all, but had been spinning through the cosmos, looking for someone to express them, when they found us.

Converge II , installation detail, Charles Cohan.

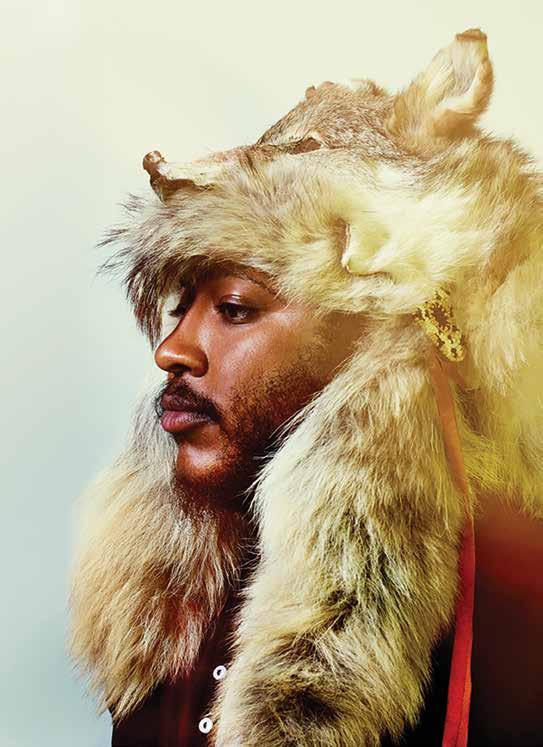

� Stephen Bruner, the artist better known as Thundercat. Image courtesy of Thundercat.

� Stephen Bruner, the artist better known as Thundercat. Image courtesy of Thundercat.

“Surf the cosmos. Smell the space dust. Find your way home.”—Thundercat, lyrics from “Song for the Dead,” from The Beyond/Where the Giants Roam

Brought to you by The Modern Honolulu

FLUX Sound spotlights Hawai‘i’s sonic talents, delving into what makes Hawai‘i music the most unique in the world.