The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme: Food Volume 8 Issue 1 Features: Food Futures

ranchers shaping the future of island food, prisons

turn inmates

farmers,

of the dinners

defined Hawai‘i. Explore: Ritual Behavior Keepers of the flame

where to find them,

ritual acts that draw drinkers closer to the heavens. Special Section: 14 Local Flavors Perspectives on Hawaiʻi’s culinary zeitgeist, including where it’s going and what more it needs. 0 01 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 25489 8

Cattle

that

into

and reimaginings

that

and

and

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

PHILES

28 | Culture: Sheldon Simeon

36 | Community: Roots Cafe

44 | Arts: Yuki Uzuhashi

A HUI HOU

192 | Glow with the Flow

FEATURES

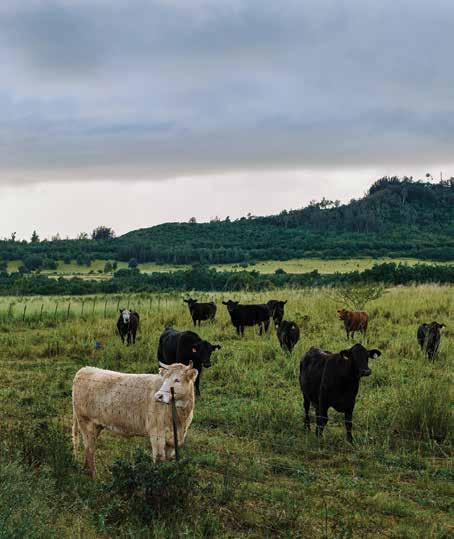

50 | Beeves of Grass

Travis Hancock explores how fallow lands left behind by Hawai‘i’s defunct sugar plantations opened the door for cattle ranchers whose old traditions and new ideas could shape the future of island food.

70 | Redemptive Roots

Martha Cheng takes a look at how two penitentiaries on O‘ahu are preparing inmates for life beyond bars through farming programs that not only feed the prisons, but also the community at large.

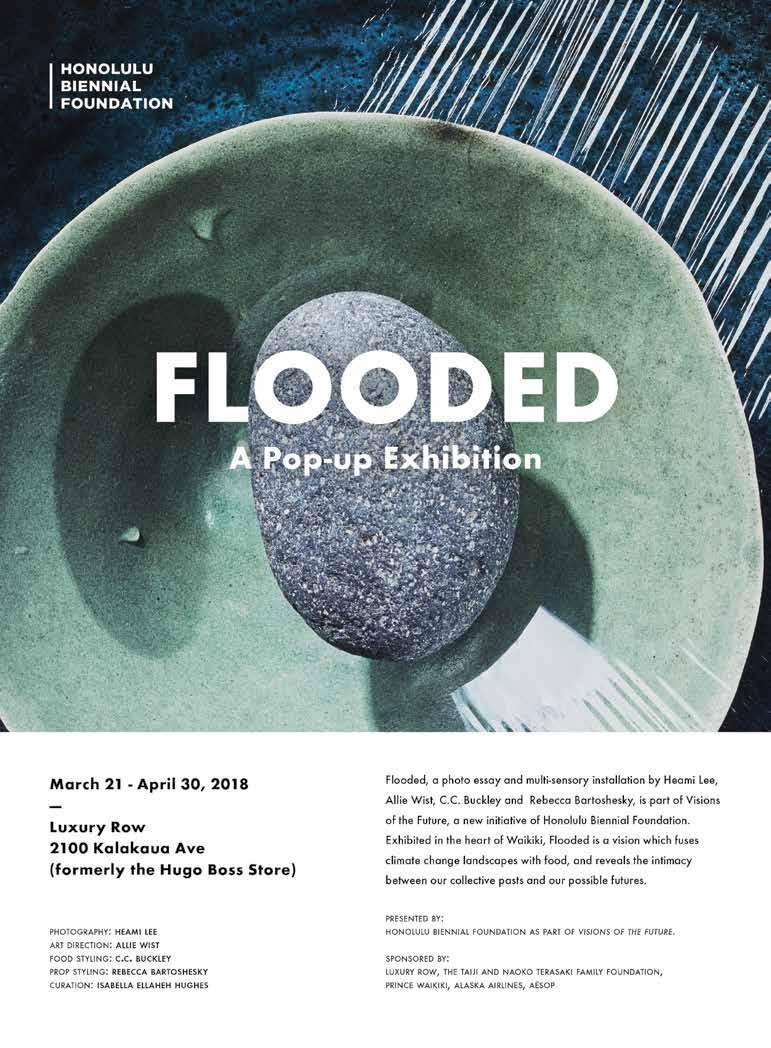

84 | Defining Dinners

Matthew Dekneef and Rae Sojot reimagine three historic dinners that highlight Hawai‘i’s changing place in the world.

TABLE OF CONTENTS | FEATURES | 26 FOOD

FLUX

SPECIAL SECTION:

14

FOODS THAT TELL US WHERE HAWAI‘I CUISINE IS GOING TABLE OF CONTENTS

� In 2018, the nature of food—its origins, its production, its presentation—is at the center of our conversations about what we eat. For this feature, we’ve compiled a diverse cross-section of voices, from chefs and farmers to writers and educators, to gain a range of perspectives on where Hawai‘i’s culinary zeitgeist is today, where it’s going, and what more it needs.

94

| SECTIONS |

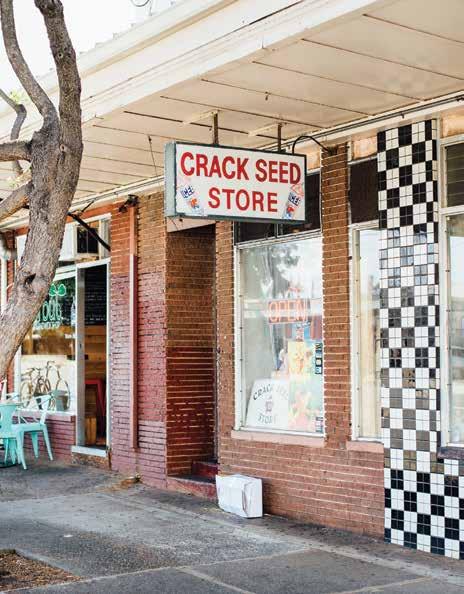

TABLE OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS | 160 EXPLORE 162 | Divinity’s Cup ʻAwa and wine 174 | This Tastes Like Home Crack seed, bento, and manapua 140 LIVING WELL 142 | Interiors The Dining Chair 154 | Health Marathon swimmer Kim Chambers

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FLUX TV |

Stay current on arts and culture with us at:

fluxhawaii.com

facebook /fluxhawaii

twitter @fluxhawaii

instagram @fluxhawaii

FLUX TV

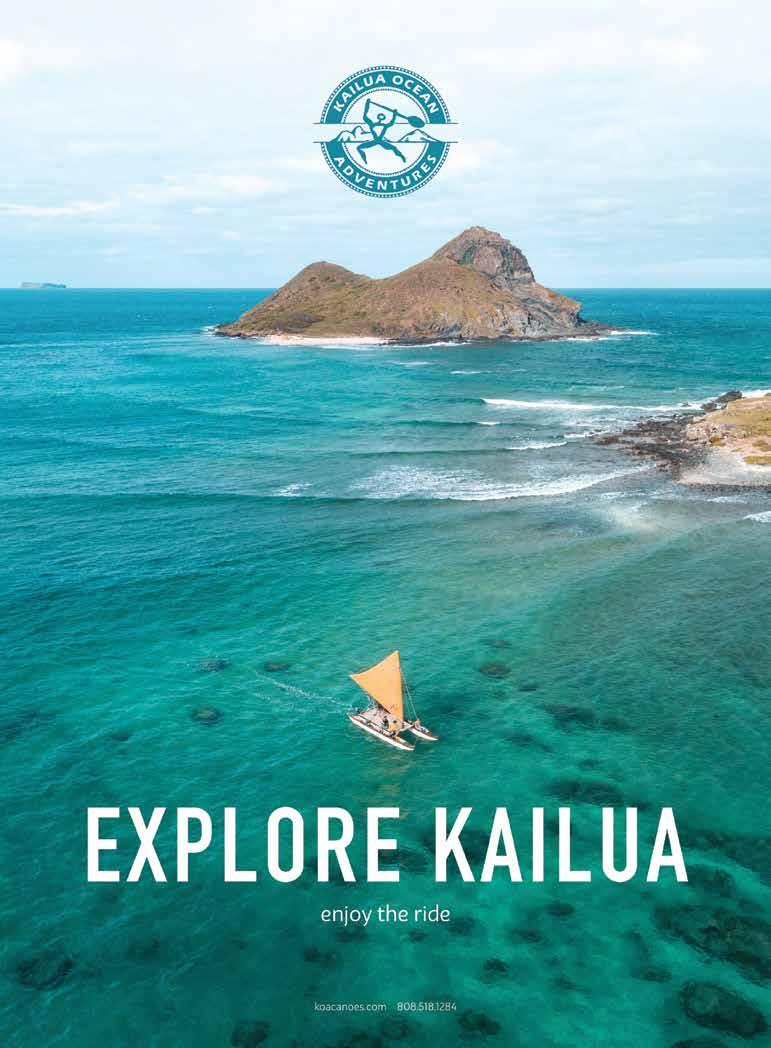

Where’s the Beef?

Spend a day with Kunoa Cattle Company, which utilizes a ranching model called holistic management in order to help Hawai‘i achieve food independence and keep its beef in the islands.

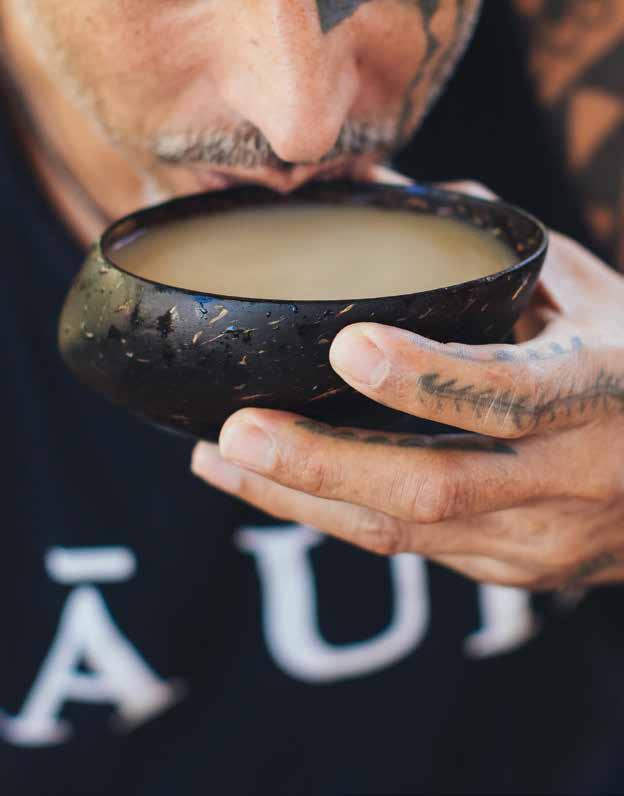

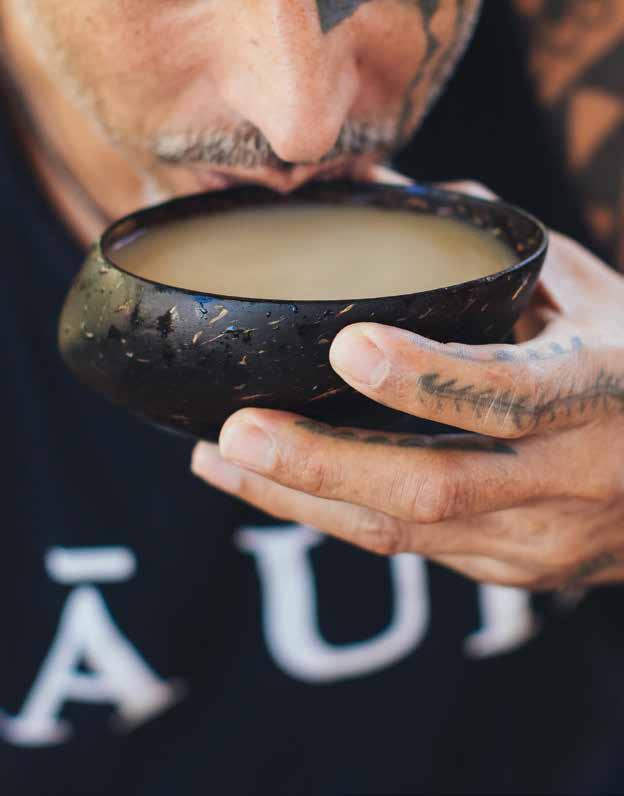

Drinking in the Divine

In Hawai‘i, Christian theology and Hawaiian mythology find twin relevance in practices where partakers drink in the divine—namely the practice of serving ‘awa and the taking of the Eucharist— as means to draw closer to one’s God or gods. In this video feature, take a look at the two spiritual rituals.

On the Wings of Bees

Records of entomophagy, the formal term for insect consumption, stretch as far back as the Edo period. In this video profile, beekeeper Yuki Uzuhashi shows diners how to enjoy the proteinrich delicacy of bee larvae.

|

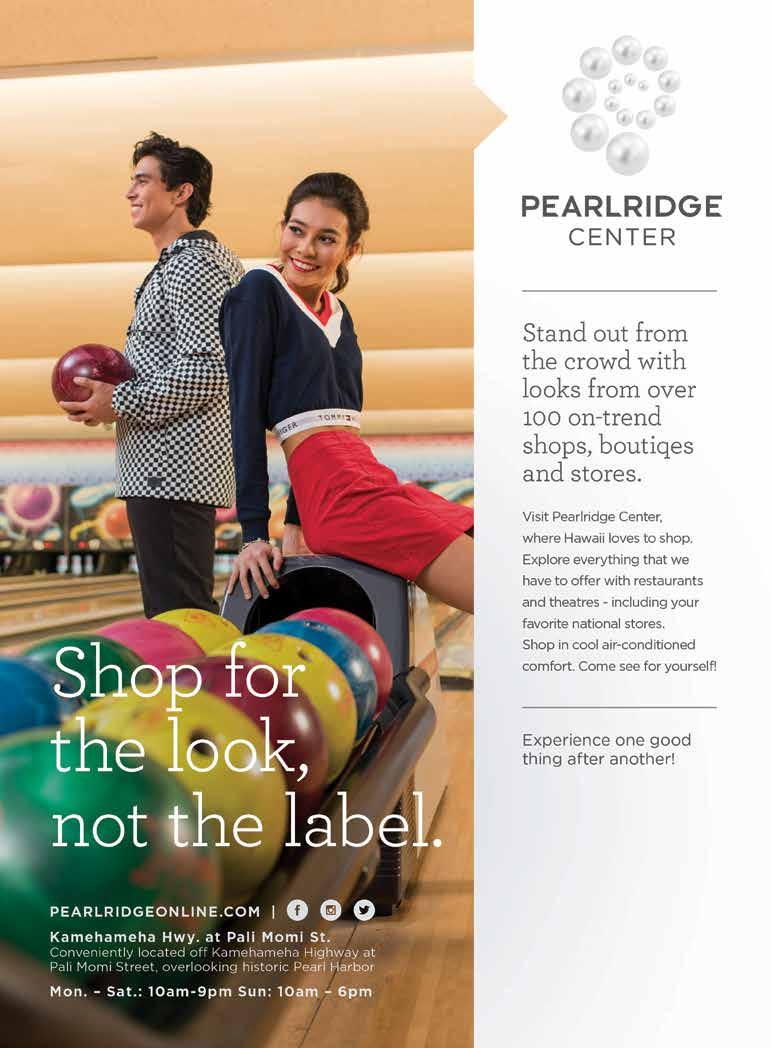

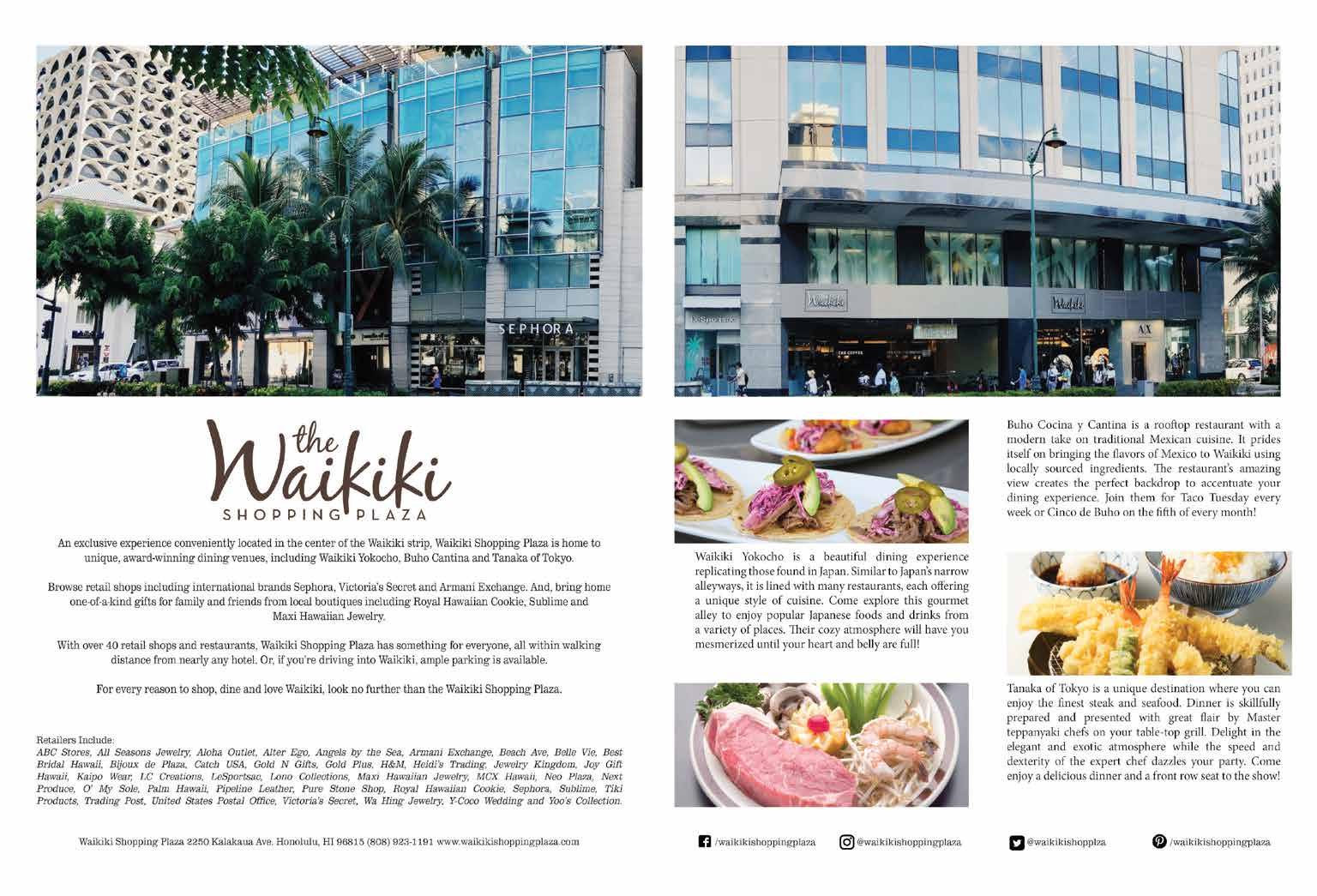

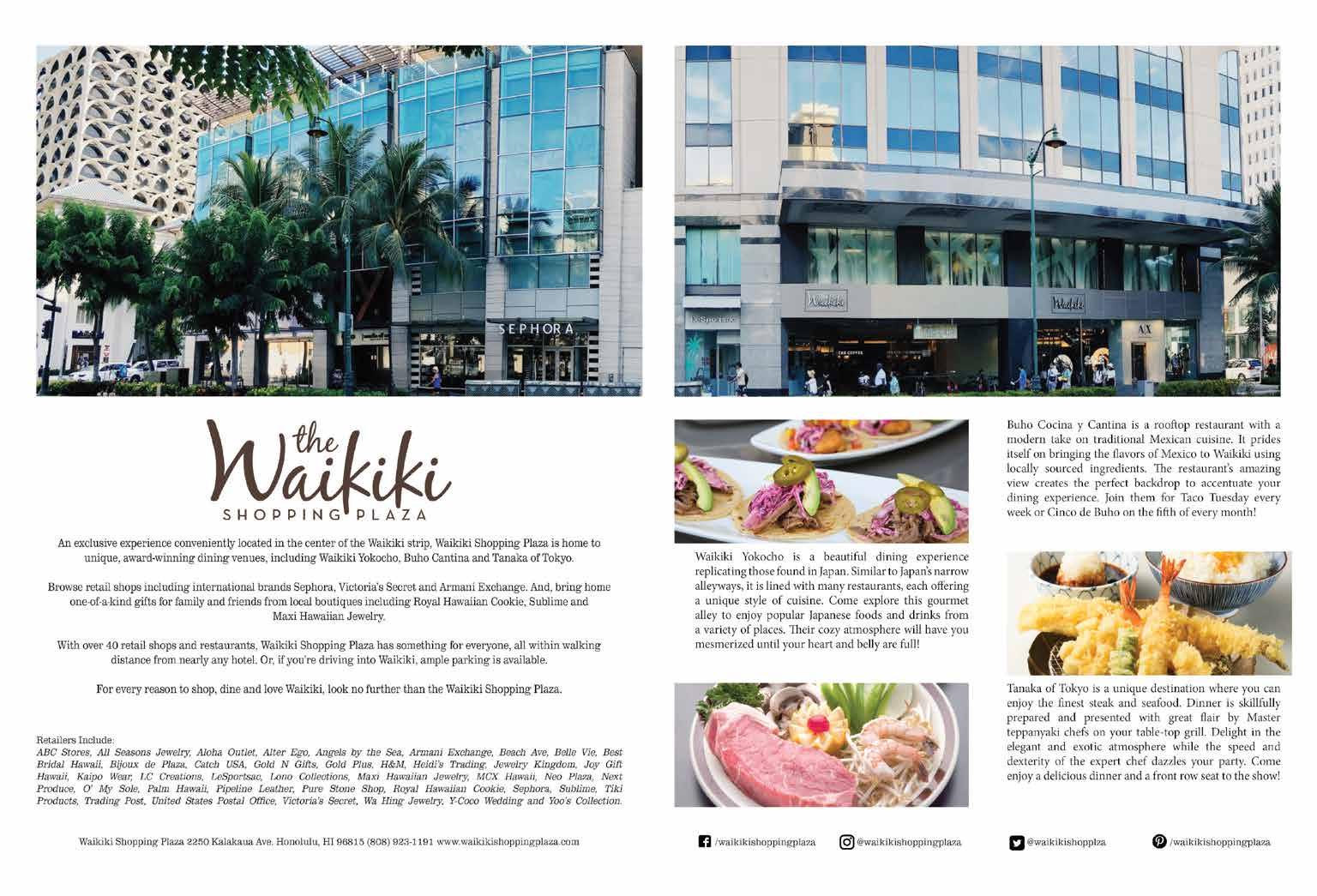

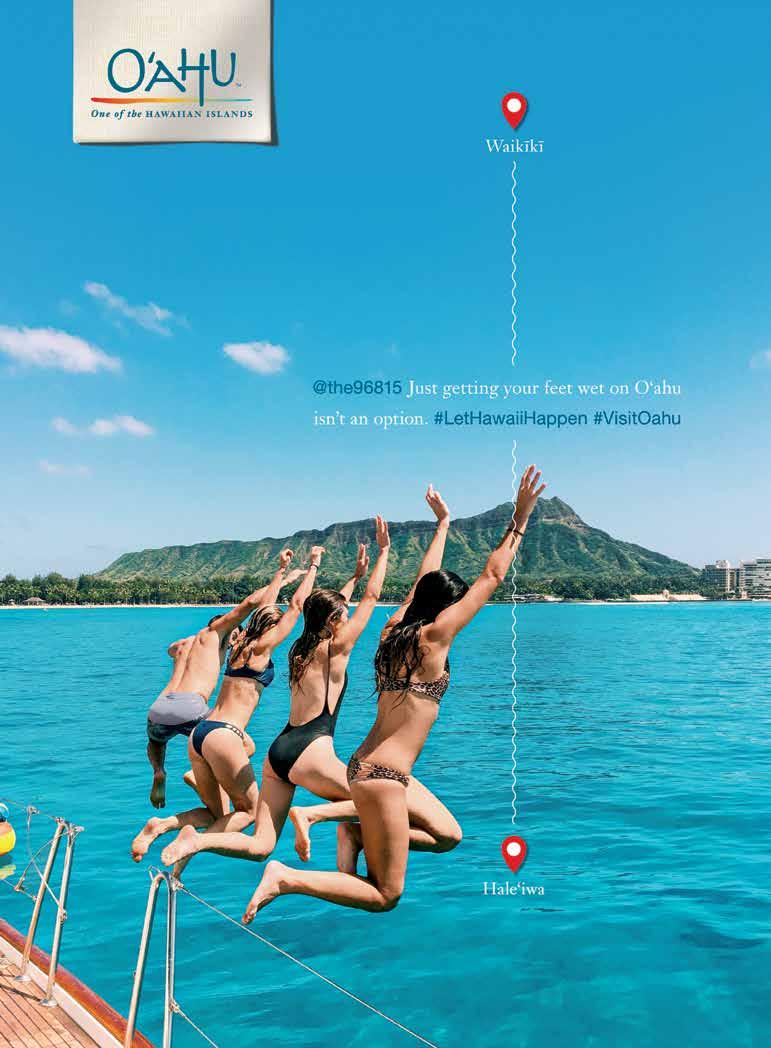

Mon-Sat 9:30am to 9pm Sun 10am to 7pm • AlaMoanaCenter com • 808.955.9517 • FREE WI-FI Your GGP Shopping Destination MORE THAN 350 STORES AND RESTAURANTS INCLUDING ANN TAYLOR • ASSAGGIO • BLOOMINGDALE’S • COACH • DIPTYQUE PARIS • GUESS • JANIE AND JACK • KIEHL’S LE LABO • LULULEMON • MACY’S • NEIMAN MARCUS • NORDSTROM • ROSS DRESS FOR LESS • SAKS OFF 5TH TARGET • THE REFINERY HONOLULU • TOMMY BAHAMA • UNICASE • VINTAGE CAVE CAFÉ • ZARA • & MANY MORE

In October of last year, I found myself in New York City, eager to dine in what many call the culinary capital of the world.

I was there to throw an event with Hawai‘i Tourism USA, promoting the sounds and flavors of the Hawaiian Islands, so with only a few days to spare, I set out to some of my favorite haunts: Russ and Daughters for bagels smeared with smoked fish and cream cheese; Katz’s Delicatessen for slabs of pastrami piled high on rye bread; Hi-Collar, a tiny 10-seat Japanese-style bar, for mentaiko pasta, omurice, and fluffy, towering hot cakes. I went for fried chicken and biscuits in Williamsburg, freshly shucked oysters in Chelsea, Italian food in Greenpoint, and New American in the East Village.

But the best food I had in New York City was not New York City food at all. It was at our event, served by a Maui chef flown in for the weekend: Sheldon Simeon. It was the first time I had tried Simeon’s food. There was ‘ahi poke, served with chili tobiko aioli and kaki mochi; pancit bucatini with bottarga and what Simeon calls “roof lemons” (see page 28); huli-huli pork belly with marungay and shoyu poi; onaga, served lāwalu-style, wrapped in banana leaves, with macadamia nuts and purple potato mash.

Can I just say that Hawai‘i food is having a moment? Simeon competed on Bravo’s Top Chef in seasons 10 and 14, and walked away with top-three finishes and the “fan favorite” award for both seasons. Poke is trending, for better or worse, around the globe. (Just when we thought it couldn’t get any worse, Tail and Fin in Las Vegas debuted its customizable pineapple poke bowls, while Poké Bowl Station—accent theirs—in Brooklyn launched handheld poke wrapped in rainbow-colored waffle tacos.) Try to walk in and get a table at San Francisco’s Liholiho Yacht Club, opened in 2015 by O‘ahu-born Ravi Kapur, who is of Indian, Native Hawaiian, and Chinese descent, without a reservation—you will likely be told to come back in two hours.

Here at home, the culinary scene is an increasingly dizzying bounty. More locally grown choices are within reach on grocery store shelves and in farmer’s markets booths than ever before. Food, as Simeon points out in our interview with him, is as powerful an indicator of culture as language and skin color. For those who hold the islands in our hearts, we know that Hawai‘i cuisine is much more than a trend. It is a reflection of who we are, a commemoration of where we have been, and a beacon of where we have yet to go.

Still, there is much work to do. Governor Ige is committed to doubling local food production by 2020, but less than half a percent of the state’s budget is dedicated to agriculture. So can it be done? Can Hawai‘i become a model for selfsufficiency? “It could be done here better than any state anywhere,” Kunoa Cattle Company co-founder Bobby Farias says, “if you let us.”

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada-Son EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

EDITOR’S LETTER | FOOD |

MASTHEAD

“Christoph Radl, creative director for Cabana and Interni. I know it would come with an art history lesson and a waterfront view of Lake Como.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Matthew Dekneef

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

DESIGNERS

Mitchell Fong

Michelle Ganeku

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

CREATIVE ASSISTANT

Naz Kawakami

“Someone with synesthesia—who can hear what they taste. I want to know what food sounds like to them!”

If you could have dinner with anyone in the world, who would it be?

IMAGES

AJ Feducia

Marie Eriel Hobro

Mark Kushimi

Josiah Patterson

Meagan Suzuki

Lauren Trangmar

Kate Webber

CONTRIBUTORS

Martha Cheng

Beau Flemister

Travis Hancock

Jen Murphy

Natalie Schack

NETWORK MARKETING COORDINATOR

Aja Toscano

WEB DEVELOPER

Matthew McVickar

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Chelsea Tsuchida MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

©2009-2018 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher.

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR courtney@nellamediagroup.com

Gerard Elmore

LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Kyle Kosaki VIDEO EDITOR kyle@NMGnetwork.com

Francine Beppu NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

INTERN Alan Fraser

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

“Barry Obama. To reminisce about our grade school and high school years together and to thank him for a favor he had done for me back in 2008.”

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein. FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication.

“Director Damien Chazelle because I’d like to pick his brain about the modern Hollywood industry and how storytelling structure is changing.”

| FOOD |

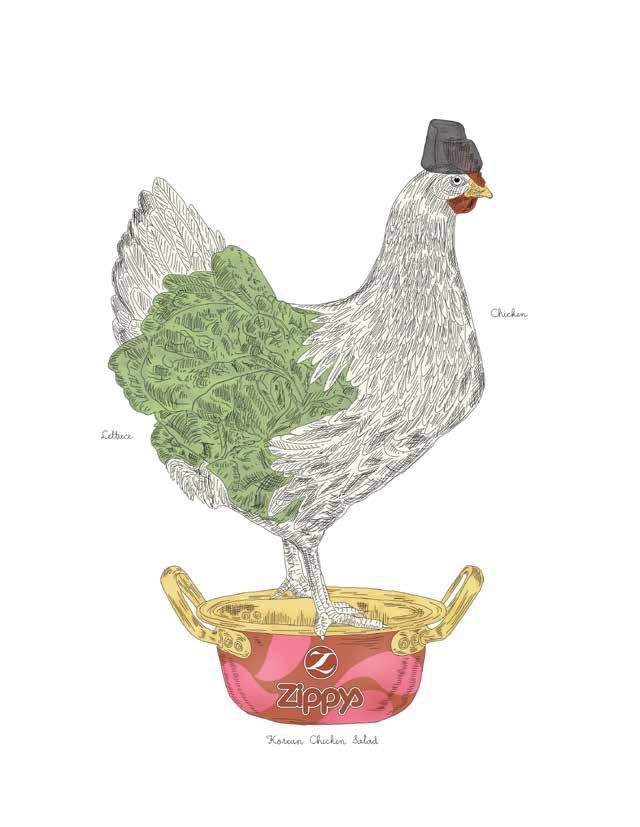

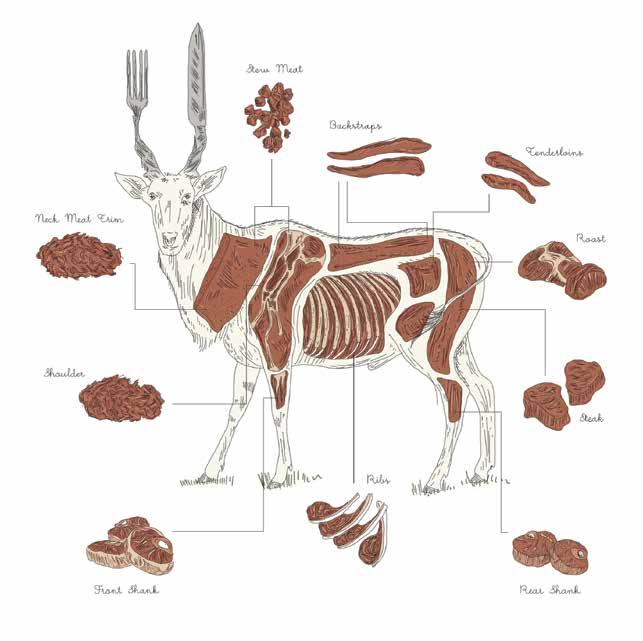

On the Cover

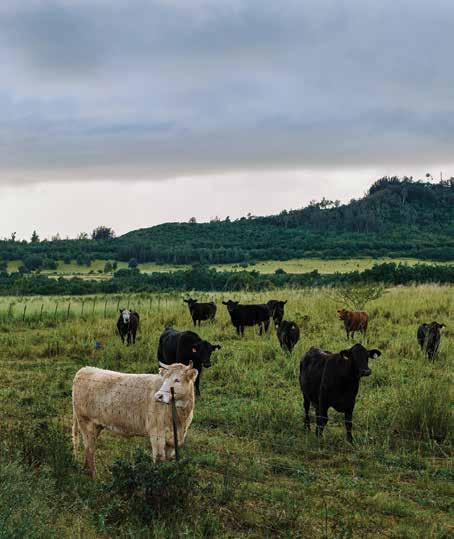

Local chicken or local beef?

In reflection of an age-old debate that continues in kitchens across Hawai‘i over what to eat for dinner, we’ve released two covers for this issue, each dedicated to these homegrown subjects. At J. Ludovico Farm in Waialua, O‘ahu, John Hook snapped this portrait of a meat chicken as part of our photo essay on page 98; in Līhu‘e, Kauaʻi, Josiah Patterson roamed the grasslands of Kunoa Cattle Company for this shot of a Black Angus cow, which you can read about on page 50.

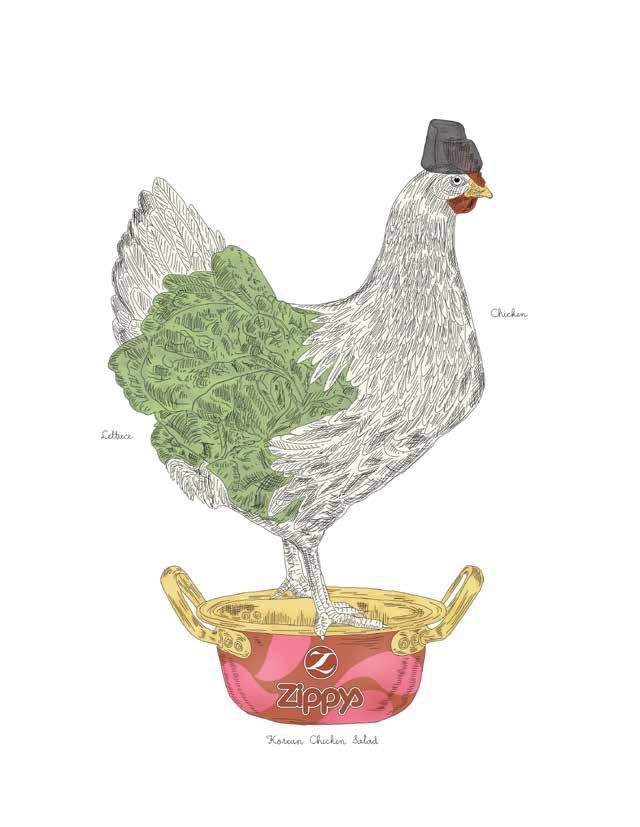

Lauren Trangmar

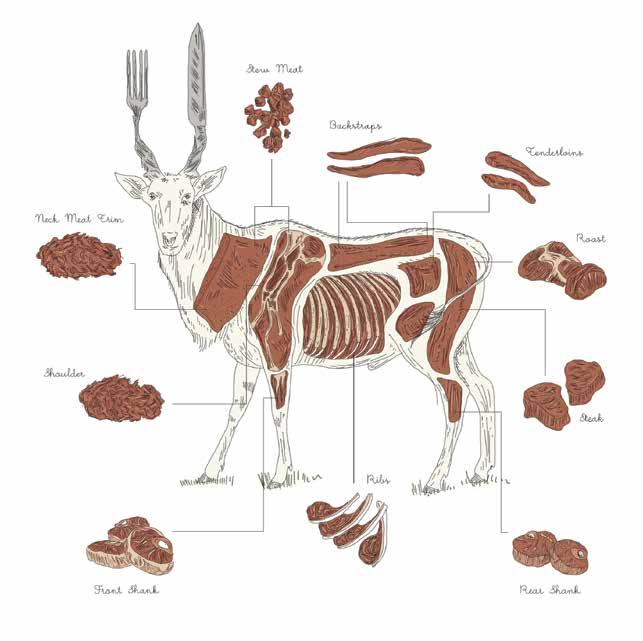

Lauren Trangmar is a Honolulu-based artist and graphic designer who combines meticulous, traditional processes with contemporary technologies to create surreal imagery. Born and raised in Christchurch, New Zealand, she moved to Hawaiʻi to purse a BFA in graphic design at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa. Her work has been included in private collections and exhibitions in Hawai‘i, North Carolina, Australia, and New Zealand. Most notably, she produced a body of work for the Honolulu Museum of Art’s Artists of Hawaiʻi 2015 exhibition. “Storytelling plays a central role in my work,” says Trangmar, whose playful illustrations accompany “14 Foods That Tell Us Where Hawai‘i Cuisine Is Going” on page 109. “Because my work belongs to an imaginative realm, I always face the challenge of capturing the essence of a story realistically, yet creatively, without pushing it too far. I like to play with form and meaning to create surprising images that are uncanny and humorous yet elicit a strange kind of logic.”

Josiah Patterson

Josiah Patterson is a selftaught photographer from Mākaha. In this issue, he photographed the ranchers of Kunoa Cattle Company for “Beeves of Grass” on page 50. “Sitting in the back of a truck while being given a tour of the ranch, I couldn’t help but notice how vast and beautiful the landscape was. While being on the move posed its challenges, it also gave me unrestricted views of mountains, pastures, and roaming cattle. I wanted to capture the beauty of the place, but also the ranchers and the hard work that they do. Hearing about the sustainable practices they employ and also the challenges that local ranchers go through gave me a newfound appreciation of where our beef comes from.”

Travis Hancock

In the process of writing the story “Beeves of Grass” featuring Kunoa Cattle Company on page 50, writer Travis Hancock got to thinking deeply about what cows, and in turn, humans, eat. This whisked him back to his childhood route to school, which passed the North Shore of O‘ahu’s mystifying Waialeʻe Livestock Experiment Station, where University of Hawai‘i scientists studied cattle that had been fitted with cannula to keep gaping portholes to their digestive tracts open in their sides. Incidentally, Hancock hasn’t eaten beef since he was 16, a fact that Kunoa co-owner Bobby Farias discovered partway through his visit to the ranch on Kauaʻi. “Have you tried our beef bars?” Farias asked. “Um, no, I haven’t,” Hancock replied. “Oh, you gotta try them!” Farias insisted. Hancock confessed he was pescatarian, and to his surprise, found the rancher tremendously understanding—his own wife is vegan.

| FOOD |

CONTRIBUTORS

Cattle roam the grasslands in L ī hu‘e. Image by Josiah

�

Patterson.

�

Patterson.

FOOD

“When the food is honest, that’s the sweet spot. It needs to be inspired by a moment, or connect to a story.”—Sheldon

Simeon

How Sheldon Got His Groove Back

Sheldon Simeon isn’t trying to reinvent the wheel. Instead, he looks to family history for inspiration in creating his soulful cuisine.

TEXT BY LISA YAMADA-SON

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

The line snaking its way along the counter and out the door of Tin Roof, the Kahului lunch joint helmed by Sheldon Simeon, never ceases. For four hours, a steady thrum of hungry patrons neatly file behind one another, waiting to get their hands on bowls filled with mochiko chicken, poke, or dry mein, and, perhaps, catch a glimpse of the guy whose humble persona and cuisine earned him the “fan favorite” award on both seasons 10 and 14 of Top Chef .

It has been a whirlwind of activity for Simeon since his two top-three finishes on the Bravo TV cooking show. He has made appearances at food and wine festivals around the country, started his own YouTube channel with Eater called “Cooking in America,” opened one restaurant, Migrant Maui, in 2014, only to close it in 2016 and open Tin Roof later that year. “I was gone every single month last year,” Simeon says. “But I’m just trying to preach the concept of Hawai‘i cuisine, [for people] to hear it from the horse’s mouth.”

For the born-and-bred Hawai‘i chef, Hawai‘i cuisine is nuanced and often misunderstood. “Everybody calls our cuisine ‘Hawaiian,’ but ‘Hawaiian’ is very specific,” Simeon says. Rather, Hawai‘i cuisine is a celebration of different moments in history, including when immigrants came to call Hawai‘i home, he says, and how it all seamlessly blends together today.

“Next time you go to a house party, just sit back and count the amount of cultures on the table,” Simeon says. “I was just in Hilo this past weekend, and we had beef stew on the table, poke, ‘opihi, kimchi stew. There’s this whole randomness of it, and to us, just felt natural. … Even though I’m not Korean, I associate kalbi as part of my culture. Even though I not Chinese, chow fun is still part of my culture.”

Simeon, who is full Filipino, attributes his philosophy on Hawai‘i cuisine to the plantation towns of Pepeʻekeo on Hawai‘i Island, where his grandparents on his dad’s side worked. He recalls biking through the Chinese and Korean plantation camps, looking for “roof lemons” to slingshot down. “The workers would take lemons, salt and sugar them— everybody had their own way—and put them in these gallon mayonnaise jars and ferment it on the top of their roof,” Simeon explains.

� For chef Sheldon Simeon, shown with his daughters at home in Wailuku on Maui, Hawai‘i cuisine is nuanced and often misunderstood.

FLUX PHILES | CULTURE | 28 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

With a large family on both his mom and dad’s sides, large parties naturally followed. His dad, a welder, would fix old stoves and fashion pig roasters and other cooking implements, sizzling dishes like his famous pork guisantes (often called “pork and peas”) in cavernous outdoor woks. “My mom, my dad, all my aunties, everybody always brought over food, and as young kids we were taught to always help out, clean the table, wash dishes. If uncle’s beer is halfway full, you grab him another one before he even asks,” Simeon recalls.

Though he initially wanted to be an architect, Simeon watched his older brother breeze through culinary school (those adolescent days honing their knife skills at family parties, butchering chickens for soups, even a neighborhood goat or pig for large celebrations, paid off). While enrolled in Leeward Community College’s culinary program, Simeon got an internship at Walt Disney World in

Orlando. There he met his wife, Janice, who was interning in the same program. But the work, as a busboy in a Mexican restaurant (“You should have seen my costume,” he says), proved uninspiring. He ended his internship early, completed two more semesters at LCC, then followed Janice home to Maui, where he would work his way up the ranks at Na Hoaloha ‘Ekolu restaurant group, first at Aloha Mixed Plate, then as the chef of Star Noodle.

But after 10 years of grueling 17-hour work days with Na Hoaloha ‘Ekolu, Simeon was burnt out. “I wasn’t always just cooking, it was stressing a lot of time,” Simeon says. “I was just tired.” With no other opportunities in sight, Simeon walked away and spent the entire summer hanging out with his kids. “It was like the first summer we actually went to the Big Island to cruise,” he says.

As it has since small-kid times, family has been what informs Simeon’s culinary

� Simeon combs his family history and classic Hawai‘i cookbooks for inspiration for his recipes, including those for dishes he serves at Tin Roof, his casual lunch spot in Kahului.

30 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

narrative and has contributed to some of the proudest moments in his career. Despite his hectic schedule and the multitudes of people vying for his time, Simeon spent the weekend cooking for his best friend’s baby’s first birthday party in Hilo. “To me, that’s the highest regards of cooking, the highest honor,” he says. “To cook for someone’s first birthday, I’d pick that over the James Beard House any day, to tell you the truth.”

Not that he hasn’t held that honor, either. In February 2017, after winning one of the challenges on Top Chef , Simeon found himself standing in the prestigious James Beard House serving his favorite plate lunch fare of mochiko chicken, rice, and ʻulu mac salad to New York’s culinary elite. It was a redemption of sorts for the chef, who failed to impress the judges in the finale of Top Chef season 10 after departing from his Filipino-inspired cuisine and cooking what he describes as

“fancy food.” But for Simeon, the timehonored Hawaiʻi tradition of a baby’s first birthday is a rare chance to feed his entire family. The same applies to Tin Roof, that unremarkable joint tucked between an island gift shop and a Money Mart. “Tin Roof has been the most rewarding restaurant for me, of all the restaurants I’ve ever done, because it’s a chance to feed my community,” he says.

In all things, Simeon is proud to represent Hawai‘i and Filipino foods, what Anthony Bourdain declared as “the next big thing” in 2017—a declaration that sits uncomfortably with Simeon. “I like that Filipino food gets a shine, but … food is tied in as personal to a nationality as it can be,” Simeon says. “Food and language and skin color is on the same level. Maybe a dish, that can be a trend, or a cronut, that’s a trend! I’m a Filipino, a culture is not a trend.”

� Family informs Simeon’s culinary narrative, which includes the dishes found at Tin Roof, shown right. Clockwise from top left: dry mein with wafu dashi; shoyu poke bowl; local kale tossed with Kula onion dressing; pork belly bowl with lomi tomato and patis vinaigrette; twice-fried mochiko chicken with kochujang aioli and mac salad.

32 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Instead, food should simply be a celebration of cultures. Simeon hopes to expand on this with the opening of Lineage in May at the Shops of Wailea. “Yeah, it will be a fancy restaurant,” Simeon says sheepishly. “I guess it’s chef-ego driven … but this is a moment that I can … express myself fully.” Though the fare might be fancier, the menu remains inspired by Simeon’s mixed-plate upbringing. It will feature an appetizer called the “pūpū line,” a celebration of all the foods one might find as pūpū for a baby’s first birthday party, including pa‘i ‘ai, pohole fern, ‘opihi, and smoked meat. He’s also doing the classic Filipino noodle dish, pancit, but his version is finished with roof lemons.

“I think when the food is honest, that’s the sweet spot. It needs to be inspired by a moment, or connect to a story,” he says. “That storyline is an ingredient that nobody can replicate, no matter if they get the same ingredients, the same recipe.”

� “Tin Roof has been the most rewarding restaurant for me, of all the restaurants I’ve ever done, because it’s a chance to feed my community,” Simeon says.

� Tin Roof is located in Kahului at 360 Papa Pl. For more information, visit tinroofmaui.com.

34 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

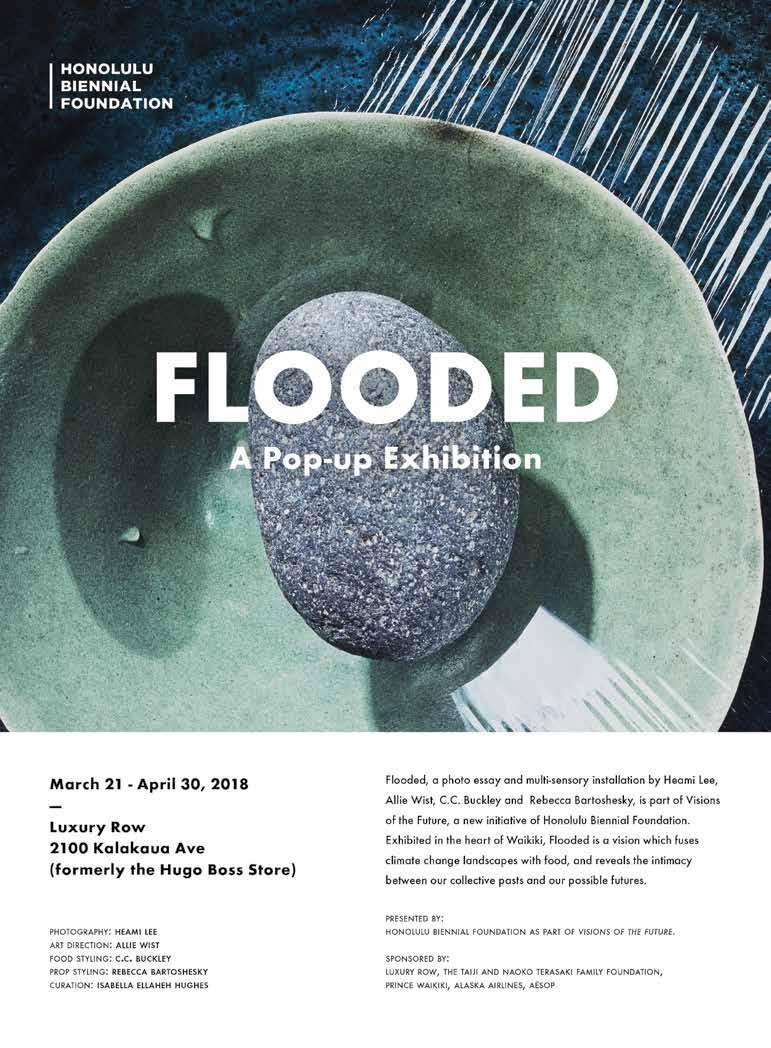

The Valley Provides

The Roots Project cooks up a hearty food system in Kalihi.

TEXT BY NATALIE SCHACK

IMAGES BY MEAGAN SUZUKI

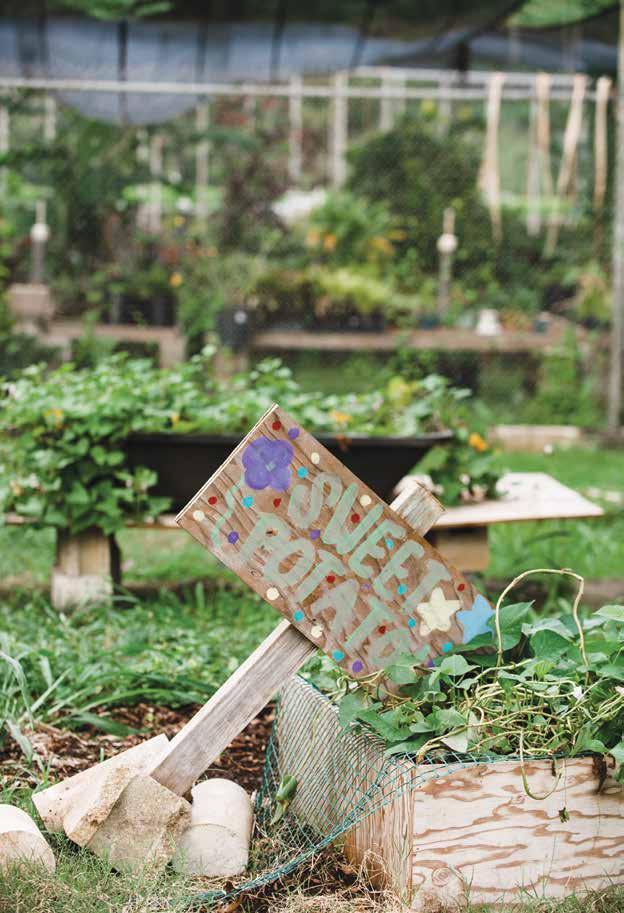

It’s Thursday at Roots Cafe, one of only two days a week the eatery is open, and it is bustling with activity. Diners greet cooks and workers by name, while groups of friends talk story, discuss work over lunch, or share food. It’s an unadorned, humble little thing, consisting of a few dining tables and a lunch counter tucked away at the far back of the Kōkua Kalihi Valley Community Health Center, on the far end of School Street. But it’s got big flavor. This day, the dishes listed on the café’s chalkboard include a barbecue portobello mushroom burger, chickpea curry, and pineapple kombucha. There is a hefty inclusion of ingredients from local farms, which are noted alongside the dish. It is a far cry from the menu of a typical graband-go plate-lunch restaurant.

In fact, Roots Kalihi, the organization behind the café, aims to change what its neighborhood considers standard fare. The organization began under Kōkua Kalihi Valley in 2011 with one grant and a vision to bring health back into Kalihi through food. Six years later, it is juggling six grants and a plateful of projects: the caf é , farmers markets, nutrition education outreach, cooking classes, cultural food events, community gardens, and a program discounting produce for food stamp holders.

The café, which opened in 2013, is a snapshot of Roots Kalihi’s endeavor to reshape the neighborhood’s food systems, from production to distribution to demand, and in body as well as in spirit. Its founders knew that native health couldn’t be truly understood solely through modern, clinical metrics like body mass index or blood pressure. For a roadmap on where to start, they turned to the community itself.

� With Ho‘oulu ‘Āina, Roots Kalihi endeavors to reshape the neighborhood’s food systems, from production to distribution to demand.

FLUX PHILES | COMMUNITY | 36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“We really wanted to sit down and ask, ʻWhat does health look like if you’re looking at wellness through indigenous eyes?’” says program director Sharon Ka‘iulani Odom. “Knowing that food connects you to all of your family, your customs, are we taking the time nowadays to share food with neighbors, to share stories with neighbors, to connect?”

The team embarked upon a year of research. They held dinners to which they invited cultural practitioners, thinkers, and community members. They asked each other how they defined good health and when they felt healthiest. The responses weren’t about numbers on a scale, weights lifted, or miles ran. Instead, they were about times when food provided key connections—to places, better selves, others, the past, and the future. Now, with each program, Odom and her team ask themselves how they can help people better connect in these ways.

Informing all programs, always, is a cultural foundation that values the power

of shared and ancestral knowledge and experiences. Special attention is paid to reviving and nurturing the food varieties and traditions of the past that once bound people together, enhanced their sense of place, and connected them to the foods on their plates.

“We want kids to know how to do an imu when they grow up, be able to be in charge and know all the steps,” Odom says. “We teach them how to lay net and how to make squid. We’ve even done haupia from scratch, where they have to get the coconut and grate the coconuts and squeeze it. It’s a family health project, but it’s based around food and taking care of the ‘āina.”

Roots is also improving access to resources. In 2013, the team launched a farmers market at the Towers at Kūhio Park, an affordable housing community. The idea was to give residents who might otherwise find it easier to reach for cheaper processed or fast-food options access to affordable, fresh, organic produce. In 2015, Roots Kalihi also launched a mobile produce cart that

� “We want kids to know how to do an imu when they grow up, be able to be in charge and know all the steps,” says Sharon Ka‘iulani Odom, the program director of Roots Kalihi, which aims to give the community greater access to resources.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

makes rounds at the health center and throughout the neighborhood, stopping at schools and workplaces. They provided access to ancestral foods such as poi and breadfruit. To bring it full circle, the nonprofit also offers nutrition awareness and cooking classes.

As families in the neighborhood get the knowledge they need to prepare wholesome meals, local farmers are finding growing customer support at the markets and health center, and Roots Kalihi’s community gardens are thriving. The cultural food knowledge of yore is being revived. It is busy but rewarding work for Roots Kalihi’s staff of about 15, each of whom contribute their own food-related passions and backgrounds in topics that include farming, nutrition, anthropology, social work, baking, and beer brewing.

Back at the café, employees and volunteers munch on rose and cardamom cookies, homemade by their operations manager, while they stuff gift baskets filled with local fruits, vegetables, and treats for helpers in the back office. Earlier that

morning, the group had come together at sister property Ho‘oulu ‘Āina, a farm and cultural space deep in the valley, for a time of togetherness and meditation. As the early sun began its crest over the Ko‘olau mountains, the Roots ‘ohana recited an oli, or chant, over the space’s four ahu, or shrines. Each individual set his or her personal intention for the coming months, and discussed their gratitude for this ‘āina, these people, and this work.

“We’re doing the best we can for Kalihi, but there are also things we’re getting from working here that’s helping us as individuals to grow,” Odom says. “From a Western point of view, it’s always about getting bigger and better—and that’s not my goal at all. My goal is to make sure that everyone is taken care of.” Roots Kalihi is doing just that, from body to soul, one plate of food at a time.

� Roots Cafe uses fruits, vegetables, and proteins sourced from local farms. While the menu changes daily, it is always affordable.

� Roots Cafe is located in the Kokua Kalihi Valley Wellness Center, 2229 North School St. For more information, visit rootskalihi.com.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The Buzz on Larvae

Out of artistic expression, a bee farmer stumbles upon an alternative protein source.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES

BY MEAGAN SUZUKI

When Yuki Uzuhashi was 12 years old, he accompanied his grandfather from Osaka to Nagano Prefecture for a summer holiday. While exploring the mountainous countryside together, his grandfather shared a curious detail from his youth: He had grown up eating hachinoko , or bee larvae. And, his grandfather added, not only was it nutritious, it was also very tasty. More intrigued than repulsed, the young Uzuhashi decided he had to try hachinoko for himself. The duo inquired among their Nagano relatives and eagerly combed local grocery shops for a taste of grandfather’s past, but their search proved futile. Then, as the two sat dejected and empty handed at the terminal waiting for their return bus to Osaka, an aunt strode in with a can of preserved bee larvae. As soon as he got home, Uzuhashi rushed to open the tin. Inside was larvae cooked in a traditional sauce of shoyu, sake, and sugar. It was savory sweet, Uzuhashi recalls. More than the taste, it was the entire hachinoko experience that left an indelible impression on the young Uzuhashi. “Searching for it, getting it, and biting on something unusual—I still remember it all,” he says.

Today Uzuhashi is the owner of Mānoa Honey Company on O‘ahu with nearly 400 hives under his care. Though first a beekeeper, he is foremost an artist. During college, he pursued sculpture, but the heavy mediums of stone and wood felt more onerous than uplifting. He later experimented with performance art, but was wary of works that leaned toward musicals or interpretive dance. Instead, Uzuhashi desired a long-term art form, an ethos that didn’t end in a white-cube gallery exhibit or a one-off performance. Inspiration came on the wings of bees. During his final year in college, Uzuhashi learned of a small tribe of people who traveled each spring from

� Mā noa Honey Company owner Yuki Uzuhashi has nearly 400 hives under his care. Though he is a beekeeper, Uzuhashi considers himself first and foremost an artist.

FLUX PHILES | ARTS | 44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

the southern islands of Japan to northern Hokkaido, following the blooming path of flowers, and in turn, bees. They were honey harvesters. “I liked the idea of a bohemian, gypsy lifestyle,” Uzuhashi says. He saw the migratory movement of the blossoms, bees, and beekeepers as organic poetry, a wonderful integrated performance set in nature. “I wanted to be like that,” Uzuhashi says. “Beekeeping would be my life’s expression of art.”

At age 23, he embarked on a beekeeping apprenticeship in Hyogo Prefecture on Japan’s main island, Honshu. Soon, his childhood memory of hachinoko, long dormant, resurfaced. As a burgeoning beekeeper, he was also the quintessential starving artist. “I was very poor,” Uzuhashi says, “so, I started to cook larvae.”

As in many Asian countries, the practice of eating bugs—namely bees, wasps, crickets, and grasshoppers—is not strange in Japan. Records of entomophagy, the formal term for insect consumption, stretch as far back as the Edo period. Though insects are more commonly consumed in rural areas or during times of food scarcity (World War II witnessed Japan’s population resorting to eating bugs out of

necessity), there has been a rise of interest in them as a viable alternate protein source across a wide swath of proponents that include environmentalists, sustainability advocates, nutritionists, and, of course, adventurous foodies. According to the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, bugs offer the same amount of protein as conventional meats like pork and poultry yet require much less feed, space, and time for growth. Their high content of nutritious fats, vitamins, fiber, and minerals has even led NASA to research insects as a possible food source for future colonies on Mars. Back on Earth, they might also help people to live longer: Nagano Prefecture, where Uzuhashi’s grandfather grew up, has the highest life expectancy in Japan, a country with a population that already averages 83.4 years as of 2015. In Nagano, insect consumption is commonplace, and men and women lead surprisingly active lives well into their 80s and 90s.

“I came into beekeeping from the point of view of contemporary art,” Uzuhashi says. Harvesting bee larvae is an edible extension of his craft. In 2007, Uzuhashi hosted what he called a “Panic Picnic,” as

� Honey is not the only life-giving substance bees provide. As a burgeoning beekeeper, Uzuhashi was also the quintessential starving artist. “I was very poor,” Uzuhashi says, “so I started to cook larvae.”

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

part of an art exhibit featuring elements of his life’s work as a beekeeper. Small teams of volunteers were given live hive trays and tweezers, and taught how to peel off the waxy brood nest cappings and extract the larvae, a laborious and meticulous process. Then, a culinary challenge was issued: Each group was tasked with creating a dish utilizing bee larvae. The result? An impressive tasting menu ranging from bee larvae pasta to bee larvae pudding. Sitting together at a long table to eat, “We cheered and gave thanks to a life given from bees,” Uzuhashi says. With each new Panic Picnic came a new set of bug-as-food believers.

Uzuhashi believes that the success of his Panic Picnics stem from the experiential excitement surrounding the discovery of something new. “Art is one of the greatest ways to change people’s perceptions or to expose them to something different,” Uzuhashi says. “Rather than going too straight or too direct into bugs as a protein food, it’s really more about experience.” Naturally, bee larvae rookies are curious, if not concerned, about the taste. Depending on the stage of development—pupa, larva, or adult—each has its own flavor profile and texture, Uzuhashi explains. When

deep-fried and salted, bee larvae tastes like crumbled potato chips. When eaten raw, they pop like ikura, or salmon roe, their flexible, firm exoskeletons giving way to a gush of creamy liquid. “It tastes like milky chestnut,” Uzuhashi says. “We also only eat the drones,” he adds, cognizant of the concern surrounding dwindling bee populations. Drones are different from the larger population of female worker bees. In their lifespans, drones perform one-time roles of inseminating the queen bee, who, once fertilized, lays nearly 2,000 eggs a day. Says Uzuhashi, “Drones play a much less important role than the workers do.”

Uzuhashi is quick to note that he doesn’t consider himself an ardent bug protein activist or even ambassador. To him, beekeeping, whether extracting honey or eating bees, is an iteration of his organic, poetic art form. He’s also diplomatic about the varied reactions—from the bewildered and curious to the bewildered and grossedout—he receives when he tells people that there’s more to bees than just honey, and that bee larvae is, in fact, a delicacy. “Some nod hard,” Uzuhashi says with a chuckle. “And some scream.”

� When deep-fried and salted, bee larvae tastes like crumbled potato chips. When eaten raw, they pop like ikura, or salmon roe, their flexible, firm exoskeletons giving way to a gush of creamy liquid.

� For more information, visit manoahoney.com.

48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

Beeves of Grass

The fallow lands left behind by Hawai‘i’s defunct sugar plantations opened the door for cattle ranchers whose old traditions and new ideas could shape the future of island food.

TEXT BY TRAVIS HANCOCK

IMAGES BY JOSIAH PATTERSON

That’s a perfect cow right there,” says Bobby Farias, as he puts his pristine Ford half-ton in park and points out the driver-side window. “Look. Number 41, height is good, good back line, sort of compact, nice and tight.” The cow whose twin ear tags read “41” is of the Black Angus breed, like most of the dozen or so grazers around her. The herd has been keeping pace with the truck as it ambles down the red-dirt road that rounds the perimeter of a sprawling grassland just upslope from Līhuʻe, Kauaʻi.

Farias has operated the Kunoa Cattle Company on these lands for nearly four years, but his roots here go much deeper. His grandfather once oversaw this area as manager of the Līhuʻe Plantation, which closed in 2000. A year later, Grove Farm added the land to its massive Kauaʻi holdings, and let wild guinea grass take over—the kind Farias knew would produce world-class beef. In 2004, Farias started leasing fallow parcels from Grove Farm, and raising calves on the hearty grass, before shipping them off to mainland buyers for grain or corn finishing and then slaughter. But the operation was “a doubleedged sword,” as he is wont to say—cattle kept the land clear and productive, but the standard export model kept Kauaʻi dependent on the mainland for beef it could clearly produce itself.

In 2014, Farias was introduced to Florida transplant and eco-entrepreneur Jack Beuttell, who envisioned a vertically integrated cattle company that could keep its beef in Hawai‘i. But Beuttell’s vision had a catch—it would require taking over the rundown slaughterhouse at Campbell Industrial Park on Oʻahu’s ‘Ewa plain. “I was hell-bent on a slaughterhouse on Kauaʻi,” Farias says. “I’m from Kauaʻi. I do everything on Kaua‘i.” But Beutell, who came equipped with master’s degrees in business administration and environmental management, and had formerly run sustainability programs for a multinational real estate firm, was convincingly pragmatic. Oʻahu’s cost of power is significantly lower, and its

customer base 15 times higher. Farias caved, and Kunoa was born.

Today, on Kunoa’s Līhuʻe land, the moans of bawling calves fill the air. “We’re getting them weaned off their moms, quieted down, and then they’ll get kicked out [to pasture], and then brought back in to get shipped to the mainland,” Farias says. Kunoa itself is still being weaned off the cow-calf model, as it is called in the industry. When Farias drives to the far side of the property, to the pasture where the ideal cow, Number 41, munches grass, he arrives at the dream represented by the Hawaiian word “kunoa,” meaning stand free. It is a dream of freedom from mainland buyers, antibiotics, foreign feed, chemical fertilizer, debt, and the fear of failure.

Farias and Beuttell believe that the best means of achieving independence is through the ranching model called holistic management, which involves rigorous rotational grazing of high-density herds on hearty grass diets. They see this model as far-reaching, with the ability to combat serious problems facing the Hawaiian Islands including the burden of fallow cane lands, the dependence on food imports, the runoff that imperils reefs, and the threat of rising sea levels. So far, the most immediate and persuasive arguments that the model has produced take the shape of USDA-approved prime cuts of beef, stamped with “Made in Hawai‘i” stickers and sold at Times and Don Quijote supermarkets.

But the public hasn’t yet reached a consensus on local, grass-fed beef, or on Kunoa as its lead provider. “Hawaiʻi was trained to buy food,” Farias says, referring to mainland imports. “That’s what Kunoa fights the most out of everything. Does it taste good? Is it tender? Is it marbled enough? Is it profitable? Those aren’t the big issues. The big issues are people saying, ‘I go to Costco for milk. It comes in a jug in aisle 12.’” With every new Costco, Walmart, and McDonalds that opens, imported food, shipped to the islands in bulk, increases its monopoly on local diets via higher convenience and lower costs.

“Hawai‘i was trained to buy food. That’s what Kunoa fights the most out of everything. Does it taste good? Is it tender? Those aren’t the big issues. The big issues are people saying, ‘I go to Costco for milk.’”

Bobby Farias, co-founder of Kunoa Cattle Company

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“

To steer public perception and, hopefully, allegiance toward locavorism, Farias takes every opportunity to speak publicly and show off Kunoa’s facilities. But for all its eye-opening power, Kunoa maintains a historical blindspot— before Hawaiʻi was trained to import its beef, it had to be trained to eat it, at a significant environmental cost. Beef entered Hawaiian diets after British explorer George Vancouver gave King Kamehameha a gift of six cows and one bull in 1793. Kamehameha protected them with a kapu, and the cattle exploded into a herd 25,000 strong by the 1840s—grazing solely, and devastatingly, on native forage. This homegrown herd on Hawai‘i Island was the genesis of island ranching, as Kamehameha III had to import vaqueros from Mexico to train up a new class of Hawaiian cowboys, or paniolo, who funneled the wild herds into beef production at places like Parker Ranch. However, corralled cattle overgrazed and trampled their pastures into desertified landscapes. Ranchers then introduced grasses and fodder that could grow fast enough to keep up—including modern menaces like haole koa and strawberry guava. To hold down topsoil and prevent runoff, they planted Australian eucalyptus and ironwood trees. And ultimately most of the hides, tallow, and meat left the islands for foreign markets.

In a sense, when Kunoa vaunts the power of local beef, it is asking consumers—including a growing base of ecominded millennials—to forget this past and trust a new era of island ranchers to do better by the ‘āina this time around. This

trust hinges on the success of holistic management, which, in the eyes of many ranchers, soil scientists, and scholars from around the world, is at best a complete gamble. Uncowed by the naysayers, Farias and Beuttell are betting on black—namely, the dark,

� To help Hawai‘i achieve food independence and keep its beef in Hawai‘i, Kunoa Cattle Company’s Bobby Farias and Jack Beuttell are betting on the hearty breed known as Black Angus.

54 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

hearty breed with marbled meat known as Black Angus. And Kunoa is all in. “If you find something that will do the community better than cattle, I’ll leave,” Farias says. “I’ll be the first one to move.”

Farias dresses the part of a Hawaiʻi cattle rancher, from the straw cowboy hat and brass belt buckle to the blue jeans and palaka-style shirt with “Kunoa” embroidered on the breast. A lifelong cattle roper who spent years competing in the mainland rodeo circuit, Farias wears the garb like a second skin. The dawn sky is overcast, filling up with sun. As if aware of the unfolding tableau, Farias’s dog Hina Iti, named during Farias’s stint managing real estate in Tahiti, trots over and poses by his boot.

Across the road from Farias is a wire fence almost totally consumed by headhigh grass. “That’s the hardline of the state and Grove Farm,” he says, pivoting around as he maps the area. “That’s Kālepa Ridge. Wailuā River is just on this side of that mountain range.” Farias’s gaze lands on an out-of-place grove of eucalyptus trees a few acres away. “That is the state line, under attack from the biofuel industry,” Farias says. Though Kunoa and biofuel companies work toward a common goal of island sustainability, Farias feels that ranchers, who also feed people and leave a less visible mark on the land, are undervalued. “A lot of the ranchers get pushed around with these higher-yielding crops,” Farias explains. In Hawaiʻi, most land leases defer to “highest and best use” terms, and returns on island cattle are historically low and a long time in the making. “We don’t mind the hard work, the heavy lifting, taking a place that’s completely overgrown, taking down all the trees, getting it all cleaned up. But then when it looks like that, somebody comes in and says, ‘Wow, that would be great for vegetables or something.’” Out go the ranchers.

The sound of conversation draws a steady muster of cows along Kunoa’s fenceline. They eye their ruler squarely.

“See, this is what we want,” Farias says, “cattle that want to know what we’re doing, versus us having to go out there and they’re all hiding in the trees. These cattle just don’t have any bad experiences so they aren’t afraid to come look. Those animals, when they go to harvest, are going to be gentle.”

Kunoa’s four-man herding team, led by multigenerational paniolo Koni Silva, and supported by at least five cattle dogs, puts the cows’ gentleness to the test. As Farias drives ahead and rounds a bend on the road, he inadvertently takes up the rear of Silva’s daily cattle drive. The men on horseback whoop and clap their hands as they press a herd of about 60 into a lane that leads to a holding pen. The dogs bark wildly, darting through dirt clouds and falling hooves. As Farias’ truck begins to approach, a few cows break and charge toward it. The dogs give chase and circle the ankles of a runner, but it leaps over them and bolts for pasture.

“Those will be culled,” Farias says. Skittish cows will raise skittish young, perpetuating a system containing smarter but less efficient cattle. “Culling is an ongoing thing, but I think in about two years we’ll have a really good bunch of cows that are giving us the kind of calves we need,” he says. “They say the difference between a good ranch and a great ranch is all the good cows. You’ve got to grow up enough to say, ‘We’re going to get rid of that good cow and make room for a great cow.’”

Since most Hawaiʻi ranchers do not have their own harvest facilities, culling has historically meant shooting the animal and leaving its disposal to nature. But with its own slaughterhouse, Kunoa has a new set of options for lower-grade animals: hamburger meat, beef bars, stew meat. At present, there are approximately 142,000 head of cattle throughout the islands, the majority of which are dedicated to producing calves for picky mainland buyers. But only a fraction of the animals that remain in the islands will make it into the eight local slaughterhouses—most of which are used privately at ranches around the state and not USDA-inspected. Kunoa

“I think you should take responsibility for that decision to eat meat. You should understand that it was a living creature that gave its life so that you could extend yours, essentially.”

Jack Beuttell, Kunoa Cattle Company CEO

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

All of the company’s lanes, pens, and harvest equipment fit the ethical guidelines set by Temple Grandin, an acclaimed proponent of humane livestock treatment.

A lifelong cattle roper who spent years competing in the mainland rodeo circuit, Farias utilizes a ranching model called holistic management, which involves rigorous rotational grazing of high-density herds on hearty grass diets.

wants to change that by opening up its facilities to other ranchers, and possibly enticing them to keep more beef in the state—a hard sell while calf sales continue to rank among the state’s top three most valuable agricultural commodities.

The cattle that Silva and his team rounded up jostle around as they get accustomed to the tighter space of the holding pen. A stout black cow with a glossy coat, tagged number 43—a virtual twin of cow 41—made the prime-cut list, and will ship to Honolulu on Tuesday. Fortunately for Silva, getting number 43 there is much easier than it was for his grandfather, who used to march cattle from Kauaʻi’s north shore across the island to Kalapakī Bay.

“They had a special group of horses that would ride into the mountains and rope all the bad cattle,” Farias says. “They would basically rope them and tie them to a tree for a couple days because they were so bad they had to let their horns get worn down a little bit.” Once broken, the leaders could be tied to a horse, and the rest of the herd would simply follow them down to the ocean. The animals then had to swim out to waiting ships, one cow on each side of the horse, which had to tread water until the cows were belly-banded and lifted onto the ship. Eventually, someone thought to replace the horses with canoes, and attach a number of cows to each side like outriggers, speeding up the load time and saving the horses from exhaustion.

Around WWII, shipping containers became the new normal, and today, Kunoa uses its own modified versions with custom, cattle-friendly windows and gates. Come Tuesday, cow 43 will be driven down the lane, then weighed and sent up a ramp into the container. After the short drive to Nawiliwili Harbor, 43 will be loaded onto a Young Brothers barge, shipped overnight, unloaded in Honolulu, and trucked out to the ʻEwa plain where, after wending through another series of lanes, pens, ramps, and scales, it will take a bolt to the brain, get broken down into cuts of meat, ride a conveyor belt into air-sealed

packages, and be placed in giant freezers until the next trucks arrive to take the meat to market.

“I think most people should eat less meat,” says Jack Beuttell over the phone from the East Coast, where he spent the holidays. “I think that when people eat meat, they should eat the right kind of meat, and I want Kunoa to be that kind of meat.” Beuttell has held this unorthodox approach to selling meat since he first pitched the Kunoa model to investors. They liked it, and tapped him to serve as the company’s CEO in 2015. Unlike Farias, who has been around cattle his entire life, Beuttell connected with the animals during the interval between college and graduate school, while working on a Colorado ranch in 2011. Even then, the concept of supplying an entire state with beef was unfathomable. Following a childhood deer hunting trip, he had been vegetarian for 10 years.

“I saw the life in that animal’s eyes when I walked up to it—or rather I saw the death in the animal’s eyes,” he said. “It was just a very intimate, powerful moment for me that made me, for the first time I think, conscious of food, because presumably we were going to eat that deer after I killed it.” Obviously, Beuttell has changed his ways since then, but he works to instill this conscientious approach in Kunoa’s treatment of animals. All of the company’s lanes, pens, and harvest equipment fit the guidelines set by Temple Grandin, an acclaimed proponent of humane livestock treatment.

“I am trying to bring more honesty and integrity to the space, and to the people that buy my product,” Beuttell says. “I think you should take responsibility for that decision to eat meat. You should understand that it was a living creature that gave its life so that you could extend yours, essentially. A lot of people don’t like that concept, but I sort of think with a scientific mind. If you look at human’s biological evolution, there’s a very tight relationship between human evolution and meat proteins.”

� At present, there are approximately 142,000 head of cattle in the Hawaiian Islands, the majority of which are part of calf-raising operations for mainland buyers.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Beuttell’s interest in biological history primed him for his encounter with the ideas of Allan Savory, the godfather of holistic management. The white Zimbabwean rancher and ecologist has been promoting the concept for 40 years, but hit a tipping point in 2013, when his TED Talk went viral. “In nature, grazing species live in herds and move in herds that are tightly bound by predators lurking on the perimeter of the herd, picking off the weaklings,” Beuttell says of Savory’s ideas. Holistic ranches mimic this through tactical fencing and culling. “The livestock follow the feed,” Beuttell continues, “so they eat that forage down voraciously and as they move along, they poop, they pee, their saliva actually serves as a stimulant of sorts to the grasses, and their hoof action turns the soil over and reseeds the grass, like a very superficial disking of the soil, and those animals then move on.” Over time, he explains, grasses evolved along with the species that grazed them.

In Beuttell’s inventory of the cattle’s various bodily emissions, he left out the most problematic one that Savory’s acolytes and for-profit Savory Institute are up against: methane from the animals’ flatulence and decomposing manure. A 2017 Penn State study found that livestock in the United States could be emitting as much as 19.6 billion pounds of methane gas per year. But proponents of holistic management attribute this to the industry’s status quo, the feedlot model, which holds animals in large, static spaces that gradually desertify land under the steady churn of hooves, and contains fermenting manure in nearby lagoons. Savory’s followers claim that the grass stimulated by roving ungulates actually sequesters carbon emissions through photosynthesis, reversing global warming. But the ostensible proof that moving herds can even affect grass growth rates, let alone greenhouse gases, has been hotly debated. Complicating matters, Savory has historically dismissed empirical studies altogether, claiming that holistic management is endlessly adaptable to different settings and thus produces unrepeatable results.

Looking past the fray, a number of ranchers around the world have cherry-picked from Savory’s strategy to find solutions that work best for their environs. At the moment, Kunoa is doing just that—as are some other Hawaiʻi ranches, though more out of tradition than newfound inspiration. Still, the current reality is that even if Savory’s ideas were definitively quashed tomorrow, Kunoa’s steadily moving herd of 2,500 is too small to significantly alter Kauaʻi’s rain-soaked landscape, for better or worse. But then, Kunoa wants to grow.

“We can put more cattle per unit of land because we have healthier land, and we have more productive land,” Beuttell says. Kunoa is nearing a goal of raising $3 million to buy more cattle, lease more land, upgrade the slaughterhouse’s capacity, and build an education center outside of it. In 2017, Kunoa was named a candidate for one of the Savory Institute’s satellite training centers known as Savory Hubs.

“What we’re trying to do is essentially shed light on these practices and create a way for consumers to engage with that narrative, to learn and understand why they should support this practice over the mainland feedlot model,” Beuttell says. “That’s where I think Kunoa is adding value and making a difference. We are essentially a vehicle for education.”

The coastal area now known as Campbell Industrial Park, where Kunoa’s slaughterhouse sits today, was once the finishing area for cattle belonging to 19th-century industrialist James Campbell. In August of 1885, the editor of Honolulu’s Daily Bulletin, Daniel Logan, joined a cavalcade of journalists from every major Honolulu newspaper, and went on a mission to explore the 43,000-acre world of Campbell’s Honouliuli Ranch. On arrival, Logan found the

62 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

� A 2017 Penn State study found that livestock in the United States could be contributing as much as 19.6 billion pounds of methane gas per year. Proponents of holistic management claim that the grass stimulated by cattle actually sequesters carbon emissions.

cattle grazing on native species that covered the slopes. In the seaside finishing paddock, he found “thick growths of pili, mākuʻekuʻe, pualele (milkweed), mānienie, kūkaepuaʻa, and other native grasses,” a vision far from the modern standard of finishing on grain or corn.

Campbell’s feeding practice was also at odds with the recommendation of the Planters’ Labor and Supply Company, an elite organization of white planters, which reported in 1883 that “the grass for stock which flourishes best on the island is the kind called ‘guinea.’” An invasive species of grass from Africa, Megathyrsus maximus, or guinea grass, was purportedly first introduced in the mid-1800s by Judge Lawrence McCully to Kaʻu on Hawaiʻi Island. It grew so well, the Planters’ report stated, that “[Charles Reed] Bishop said that this kind of grass ought to be more generally introduced. He had no doubt that it would prove valuable to feed stock.” With the seal of approval from Bishop— and a record of proven success in colonial agriculture projects in South Asia and the Caribbean—the introduced guinea grass became the feed of choice for island ranchers, and it remains so to this day.

And yet it seems that the decision to rally behind guinea grass was made in haste. Campbell’s herd of 5,500, which was subsisting and finishing on mostly native grasses, supplied one third of Honolulu’s daily meat consumption in 1885. What’s more, “The ranch is capable of supplying a much larger daily quota of beeves,” Logan wrote. “If the grasses, and other plants in their present condition, mean anything, they indicate enough and to spare for herds numbering twice five thousand.”

The planters’ quick deference to guinea grass derives from its ability to outpace foreign grasses introduced earlier to the islands. In 1889, the Hawaiian Gazette reported, “It is well known to all country residents that the native grasses have been steadily ousted by two foreign intruders, viz.: Hilo grass and mānienie.” Unfortunately, neither Hilo grass nor mānienie, also called Bermuda grass, produced quality beef. Instead of working to re-establish the wholesome

native grasses that fed Campbell’s cattle, which would have required time, space, and controlled breeding and grazing, the planters conducted an experiment. They tried sowing imports like guinea grass right over patches of Hilo grass. In a short time, the Gazette reported, “The foreign grasses, in spite of a luxuriant growth of Hilo grass, were holding their own famously.” Ironically, the success of guinea grass was seen as a win for diversity—making cattle, once an exclusively royal holding, viable to the haole planters whose coffers were previously dependent on sugar. As it turned out, the guinea grass spread indiscriminately throughout the cane fields, leading planters to introduce herbicides to the soil, and thus the water beneath it. With a trickle-down effect similar to so many other introduced elements of Hawaiʻi’s history, the cow was a big drop in a small pond, and it still ripples like wind across a field of grass that will never give a native plant a chance to break the soil. This, too, is the price, of local, grass-fed beef.

“The guinea grass is a double-edged sword,” Farias says, driving down a muddy road through Kunoa’s coastal finishing paddocks, immediately north of Līhuʻe Airport. The use of the metaphor speaks to his ability to look at problems from both sides, but this time he is being quite literal. If guinea grass grows too tall, its sharp edges slash the cows’ eyelids, which can attract flies, cause infections, and ultimately lead to a culled animal. But they let the grass here grow tall and seed out for practical reasons. “We’ve never planted any grass. This grass is trying to come back natural. It’s fighting all that herbicides and all that they put down,” he says, referring to the old sugar planters and the area’s last tenant—Syngenta.

In recent years, Syngenta, which grows seed corn on Kauaʻi, has faced fines from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and been taken to court for its pesticide use. By comparison, the ranchers raising guinea grass seem rather benign, and maybe in the broad scheme of things, it is better to have

� For Farias, growing grass is better than what his neighbors are growing, which include genetically modified corn crops for seed, invasive eucalyptus trees for biofuel, and even massive solar fields for energy.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

an introduced mammal keeping introduced grasses in check. As far as Farias is concerned, any grass is better than what his neighbors are growing, including genetically modified corn crops for seed, invasive eucalyptus trees for biofuel, and even massive solar fields, which are being developed by Tesla. Because the solar panels sit close to the ground, they actually hog the sun, preventing any undergrowth that would trap the topsoil. “It’s a monoculture,” Farias says. “If we all approach agriculture that way, then we’re going to be in trouble.” For Kunoa’s part, solar is relegated to the roof of the harvest facility. And while beef itself may be a monoculture, Farias reasons that “it’s a moveable crop.” In other words, it’s a stopgap against larger, less pono powers.

The dirt road ends at the edge of a bluff, and Farias parks his truck, its tires enveloped in red mud. He throws a stick for Hina Iti, then turns to survey the view—some tasseled grass, a few ironwood trees, and the wide, blue ocean.

“This is why we’re never going to own ranch land,” he says. The landowners and developers see too much potential, a higher, better use. “They’re going to sit here and have a drink and tell everybody how you can’t sell this for what Bobby wants to pay,” he says. Farias lets his thoughts run on, from hotels, to school lunches, to Mark Zuckerberg, and then recalls a recent run-in with Governor David Ige.

The governor asked him what he thought about increasing local food production, to which Farias replied, “I don’t see it.” Ige was stunned, saying, “I thought you, of all people.” But because the government only devotes less than half a percent of its budget to agriculture, Farias stood his ground. He

says that he told Ige, “We’re not magicians. You guys brag on the tourist numbers because that’s how much you put into it, you know? It’s like a bank account— you only get out of it what you put into it. So can it be done? It could be done here better than any state anywhere, if you let us.”

� Currently, less than half a percent of the state’s budget is dedicated to agriculture, even though it has set a goal to double local food production by 2020.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

Redemptive Roots

Hawai‘i’s prisons are preparing inmates for life beyond bars through farming programs that not only feed the prisons, but also the community at large. Although some consider these programs controversial, in the end, they may provide the solutions that redeem us all.

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG

IMAGES BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO & JOHN HOOK

It’s going to sound kind of weird, but I originally got into baking because I used to sell and make drugs,” Tricia Liupaono says. “When you cook cocaine, it’s a chemistry, and pastry is a chemistry.”

Liupaono, who was convicted on drug charges and served four years in state prison, now works as a pastry cook and baker at Aulani and Embassy Suites by Hilton in Kapolei. She has a knack for transferring her skills from the illicit to legal. Since she was released from prison in 2011, she has cooked in kitchens from Morimoto to Sullivan Family Kitchen, the production facility for Foodland and other subsidiaries, where she was promoted to manager. Before then, “the only thing I supervised and managed was dealing drugs, and it’s kind of the same concept,” she says. “I was in charge of ordering, and I never ordered fruit before, but I knew the concept of supply and demand, and I knew how to buy wholesale, break it down to make it a profit.”

While the state doesn’t keep data on the professions of former inmates, anecdotal stories indicate many find their ways into the restaurant and food industry. “There are so many convicts and felons that are really good at [working in restaurants],” Liupaono says. In some ways it is a natural fit for those who eschew office jobs, who can take the hot and physical labor that restaurant work entails, and, like Liupaono, who enjoy the adrenaline rush.

The food industry was also one of the few avenues available to her after prison. “It’s not that I only wanted to do culinary,” she says. But her conviction of distribution of a dangerous drug precluded her from jobs in the travel and nursing fields, other areas in which she was interested. In the restaurant industry, she says, people “never did discriminate who I was, where I came from, never judged me. It’s such a big and

huge industry that they need people. Do you need a background check to cook turkey and flip burgers or chop onions? No. You can take it as far as you want. As soon as you get your foot in the door, as soon as they see who you are as a person, the criminal record fades away and they don’t care about it anymore.”

And the restaurants need them. In Hawai‘i, the restaurant and food service industry employs 14 percent of the labor force, second only to the government. In addition, Hawai‘i’s unemployment rate hit a record low of 2 percent in December 2017, shrinking the labor pool and making it difficult for employers to find people. Add to that the lowest wages out of any major occupational group—restaurant workers earn an average of $22,165 annually—and it’s easy to see why there’s a constant labor shortage in the industry.

Russell Siu, chef and owner of 3660 on the Rise and Kaka‘ako Kitchen, has for years hired former inmates and inmates on work furlough. “It’s hard to find help,” he says. “And we like to give them the opportunity.” Most of the people Siu hires have been convicted on drug charges; some of them go back to using and drop out of the kitchen. “There’s a 50-50 chance these workers will make it,” Siu says. Even on general terms, the restaurant industry’s turnover rate is high: 70 percent was the national average as of 2016.

Currently, Siu employs three former inmates at Kaka‘ako Kitchen. One of them, Frank Scott, 41, has worked there for five years. He began as a dishwasher and is now the front-of-house manager, one of the first people you meet when entering the restaurant. He was in and out of prison on theft and drug paraphernalia convictions starting at age 26. After prison, he thought he would go into construction. “I didn’t want to use my brain,” he says. Instead, through a friend, he heard about the

“I was scared and worried about finding a job. With a felony background, I really don’t know where I would have been.”

Tricia Liupaono, pastry chef

� Tricia Liupaono’s conviction precluded her from jobs in the travel and nursing fields. The food industry was one of the few avenues available to her after prison.

72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

“

� Lyle Botelho, left, and Daniel Stephens, right, pick cabbage at the Waiawa Correctional Facility in Waipahu.

� Lyle Botelho, left, and Daniel Stephens, right, pick cabbage at the Waiawa Correctional Facility in Waipahu.

job opening at Kaka‘ako Kitchen. Since then, he has learned to write checks and manage people. “I have to say, I think I should have been doing something like this,” he says. “I’m such a social person. I like to talk to people and so forth. It doesn’t bother me to actually hold a conversation with people.” Siu’s wife, Marcy Uyehara, who runs Kaka‘ako Kitchen, calls him “Mr. Aloha.” Over the span of an hour, he leaves our conversation three times— to follow up on an older couple’s dinner order and to greet regulars with a kiss on a cheek. He says people even recognize him from his cameos on OC16’s The Champ Show and Terrace House , a Japanese reality TV series.

That’s the thing about restaurants: They are large, consumer-facing businesses where, in the end, no one cares whether you’re a Harvard grad or a convicted felon, as long as you can do the work.

It makes sense, then, that the Women’s Community Correctional Center on O‘ahu’s east side offers for-credit culinary classes through Kapi‘olani Community College, which Liupaono signed up for when she was incarcerated. “I was scared and worried about finding a job,” she says. “With a felony background, I really don’t know where I would have been, what I would have done when I got out of jail, if I would have gone back to selling drugs, if I didn’t have [culinary] as my backup.”

Since leaving the Women’s

Community Correctional Center, Liupaono has earned an associate degree in pastry arts from Kapi‘olani Community College. She has worked at events like the Hale ‘Aina Awards, and has even helped organize a KCC fundraiser benefiting women.

Hawai‘i’s recidivism rate of 52 percent suggests that a job alone isn’t enough to keep former inmates from returning to prison. But for Scott, the bonds that kitchen culture forges, with its high-intensity environment and close interactions with other

� Prisons like the Women’s Community Correctional Center and Waiawa Correctional Facility use agriculture to teach focus and discipline, skills inmates will need for jobs once they get out.

76 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

At Waiawa Correctional Facility, the rate varies, but inmates are paid up to $2 an hour for labor on the farm. There are more applicants signed up for the program than there are available slots. Since 2011, at least eight former inmates have gone on to work in agriculture. Shown here, Leighton Fuentes plants seeds in Waiawa Correctional Facility.

Waiawa Correctional Facility’s nearly 200 acres include prison facilities, an 8-acre farm, an aquaponics farm, a fruit orchard, a koa forest, and a Christmas tree farm.

Waiawa Correctional Facility’s nearly 200 acres include prison facilities, an 8-acre farm, an aquaponics farm, a fruit orchard, a koa forest, and a Christmas tree farm.

workers, helps. “I always keep that in the back of my mind—I can always get in trouble,” he says. “I separate myself from the friends I knew. I keep my circle small. And I work. I think about this place a lot. Sometimes I even dream about this place. It’s a business and it’s family. My boss is like my mom. She’s on me all the time: ‘If I ever catch you with drugs…’ We’ve become really close, and it’s kept me out of trouble.” Monday through Friday, 11:30 a.m. to 9 p.m., Scott is at the restaurant.

Inside the prisons, some programs use growing food to teach focus and discipline, skills the inmates will need for jobs once they get out.

Waiawa Correctional Facility, formerly a military installation, was converted to a minimum-security prison in 1985, and its prison farm program began in 1987. Across Waiawa’s nearly 200 acres are prison facilities, an 8-acre farm, an aquaponics farm, a fruit orchard, a koa forest that the prison maintains for University of Hawai‘i researchers, and a Christmas tree farm that supplies state, city, and county agencies. Here, at almost 1,000 feet in elevation, where vegetation is thriving, the air feels cooler. Neat rows of lettuce stretch out in front of the barracks, and the tops of Christmas trees peek out over other trees.

Wearing faded red shirts, 37 inmates harvest lettuce from the ground, as well as vegetables including ong choy and

mustard cabbage from the aquaponics setup. The farm yields 2,000 to 3,000 pounds of produce a week, supplying about 10 percent of the vegetables in Maui and O‘ahu prisons. In line with Governor Ige’s goal of doubling local food production by 2020 and

recent farm-to-school initiatives, the long-term plan is for Waiawa’s farm to supplement all of the state’s prisons, as well as the state’s schools.

Inmate Leighton Fuentes, who is in Waiawa for robbery, can name at least five varieties of lettuce

� “To see life, see something go from nothing, being renewed, grow, it gave hope for the situation and predicament that we were in,” says Tricia Liupaono, who now works as a pastry cook and baker at Aulani and Embassy Suites.

80 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

grown on the farm, including Tropicana, ānuenue, and a Korean green leaf lettuce, which is his favorite. “The more you put into it, the more you can see the results,” Fuentes says. “We don’t use any pesticides or herbicides. Everything we do to keep the weeds in check, we do by hand. So if you let it slip, it’s going to show. It helps to develop a good work ethic, and helps us to work together, work in unison.”

Fuentes spends his time in the greenhouse, sprouting the seeds and transplanting the seedlings in the field. “It’s really, really satisfying to see the fruits of labor,” he says. “And it’s a peaceful respite.”

For inmate Kevin Harris, serving time for unauthorized entry into a motor vehicle, it’s caring for another living thing that gives him gratification. He monitors the fish in the aquaponics system, which, last year, yielded 1,200 pounds of fish that was given to the KCC culinary program. (They can’t be fed to the inmates, for the risk of choking on bones.) “Idle time is where we go wrong,” Harris says. “For me, it’s having responsibility [that keeps me out of trouble], and having responsibility is taking care of the fish.”

Waiawa’s farm is not unique. Prison farms exist in many states and on much larger scales. At the Louisiana State Penitentiary, the largest maximum-security prison in the United States, inmates harvest four million pounds of vegetables, while the Cañon City prison complex in Colorado houses a 30-acre produce farm that supplies the prison. Some consider prison labor—in particular, the labor that supplies commercial businesses—exploitative. In response to protests in 2015, Whole Foods stopped selling cheese made with goat milk from Cañon City’s prison goat dairy. But others consider the labor part of a rehabilitation process, providing inmates with psychological benefits and a skillset

for when they are released and enter the work force. At Waiawa, the rate varies, but inmates are paid up to $2 an hour, and there are more applicants wanting to work the farm than there are available slots. (The prison hopes to get more funding for supervisory staff positions, so that 20 to 30 more inmates can work on the farm.) Since 2011, at least eight former inmates have gone on to work in agriculture.

Over at the Women’s Community Correctional Center, the hydroponics system functions as therapy as much as it does food production. The Lani-Kailua Outdoor Circle partnered with the women’s prison to create the hydroponics program in 2008. “We built those machines from the ground up,” Liupaono says. “That whole place was all trash. There was nothing, it was all dead. [The Outdoor Circle] taught us how to do hydroponics—it was the best program I was ever in. To be able to see something grow from a seed into a big entire plant that feeds you, that whole experience was indescribable. And just to see life, see something go from nothing, being renewed, grow, it gave hope for the situation and predicament that we were in.”

The women harvest more than 200 heads of lettuce a week, which are sold at five Foodland locations on O‘ahu. The Lani-Kailua Outdoor Circle manages the program and reinvests the profits back into it.

Hyacinth Poouahi, who has been incarcerated at the Women’s Community Correctional Center for eight years, says working the hydroponic farm has been healing and has helped her get along with others. “And I just enjoy it,” she says. “For those couple of hours that we come down here, it makes you feel like you’re not in prison, because you get to work with the land.”

“The more you put into it, the more you can see the results. … So if you let it slip, it’s going to show. It helps to develop a good work ethic, and helps us to work together, work in unison.”

Leighton

Fuentes

� Andrew Kaoihana mends his section of the Waiawa Correctional Facility farm.

82 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

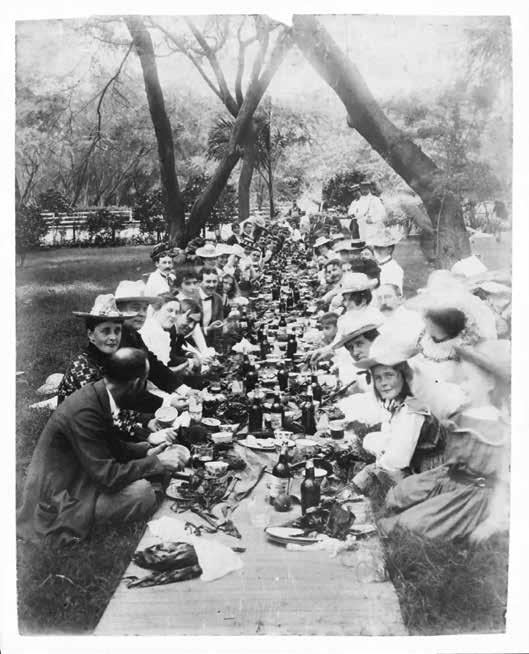

Defining Dinners

Hawai‘i’s iconic flavors go hand-in-hand with the customs that shaped them. Here are three historic meals that have gone on to forever alter the islands’ culinary landscape.

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF & RAE SOJOT

IMAGES COURTESY OF HAWAI‘I STATE ARCHIVES

84 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

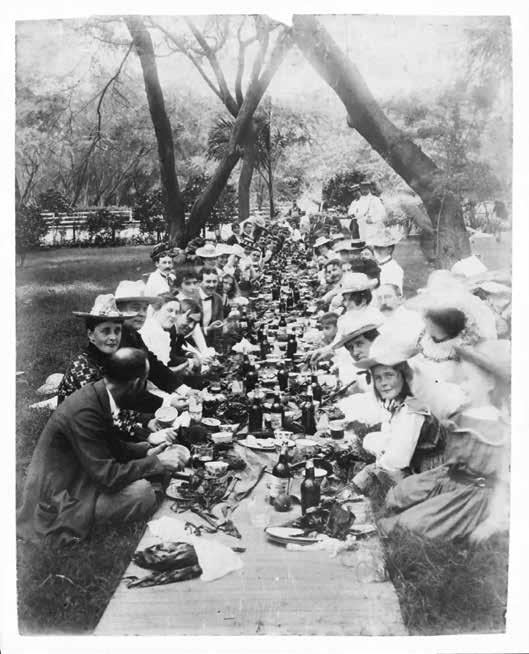

BREAKING KAPU: WHEN HAWAIIAN MEN AND WOMEN FIRST ATE TOGETHER

November, 1819. On the shores of Kailua, Hawaiʻi Island, the stage was unassuming, but set: two tables and woven mats—one for kāne, the other for wāhine. Seated with the women were Kaʻahumanu and Keōpūolani, two of the recently deceased King Kamehameha’s highest ranking wives, in the company of their royal female attendants. In front of them was a spread of kalo, iʻa, and limu (taro, fish, and seaweeds). Dining separately, at a generous tableau strewn with calabash bowls of puaʻa, maiʻa, kalo, ʻulu, and niu (pork, bananas, taro, breadfruit, and coconuts), the tender and savory staples of the people’s diet, were the leading chiefs of the time, sharing these foods with a handful of European male visitors. On the surface, this gendered scene was following standard protocol of the ʻai kapu, or “sacred eating” law. For centuries, this and other kapu laws, infused with political and spiritual powers, organized the daily fabric of Hawaiian society.

However, Kaʻahumanu, in alliance with Keōpūolani, was intent on ensuring that this evening’s meal would take a new course. She began by persuading Liholiho, Kamehameha’s chosen successor and Keōpūolani’s son, to call upon a dinner and surprise his brethren by explicitly breaking the ‘ai kapu by eating with the women, instead of the men. Liholiho, who was last to arrive, was visibly nervous as he entered the feast, clearly torn between upholding the framework of laws followed closely by his father or setting in motion the new progressive ideals of his mothers. He slowly circled both tables two or three times, as if considering the array of dishes being served on each.

In Hawaiʻi, food had always carried clear religious overtones. The act of

eating itself was seen as communing with the multitude of godly beings Hawaiians worshipped. The women, even consorts with unquestionable political clout like Kaʻahumanu, were not considered sacred enough for such an exchange, and refrained from eating the specific foods associated with male deities, such as bananas, a land form of Kanaloa, and pork, the beastly shape of Lono. ʻAi kapu went so far as to require women to only partake in foods that had been prepared in an imu designated for their gender, so as not to defile the holy communion between a man and his pork, his bananas, his coconuts, and his gods.

Kaʻahumanu was determined to dismantle this deeply ingrained edict. Upon Kamehameha’s death six months prior, she had emerged the most powerful person in the Hawaiian kingdom, as he had decreed her the kuhina nui, the co-ruler, of his newly unified islands, alongside Liholiho. She could order that all the guns of the neighboring aliʻi be collected and taken into her possession, which she commanded following Kamehameha’s last mortal breath. On any given day, she could be wrapped in new exotic fashions gifted by European explorers, a symbol of her boundless relationship to lands and luxuries the male aliʻi didn’t possess.

Yet, she still couldn’t feast from the same bowl as any of the men. Because of this, she hungered for a change. After all, dinners, from a Western perspective, displayed the power to bring people together, not divide them, and was something Kaʻahumanu witnessed intimately during her rise to power. She indulged in ignoring the ʻai kapu often throughout her youth. In her 20s, she spent an afternoon eating in the company of a young haole lieutenant under the watchful eyes of her allfemale court. She offered him fruit and sent to have coconuts, a forbidden

food, gathered from a nearby tree and presented to him. While the two ate together, her attendants continued to wave Kaʻahumanu with kahili, fanning a scene they hadn’t witnessed on their ‘āina before. In her 30s, while entertaining a Russian commander, she called for a watermelon, then cut it and offered it to him with her bare hands, a sacrilegious display, since women were never allowed to touch a man’s food. In the commander’s expedition journals, he described her as one who “united a clear understanding with masculine spirit, and seems to have been born for dominion.” Most importantly, according to historians, is that Kaʻahumanu always performed these displays in the presence of other Hawaiian women. Already she was stirring an appetite for a new social dynamic among her circles.