Well: Back to the Earth Maui naturists bare it all, and the dead inform the living how to lead a more eco-conscious existence.

Power in Unity Kūpuna take on development, houseless find belonging, and migrant patriots fight for freedom.

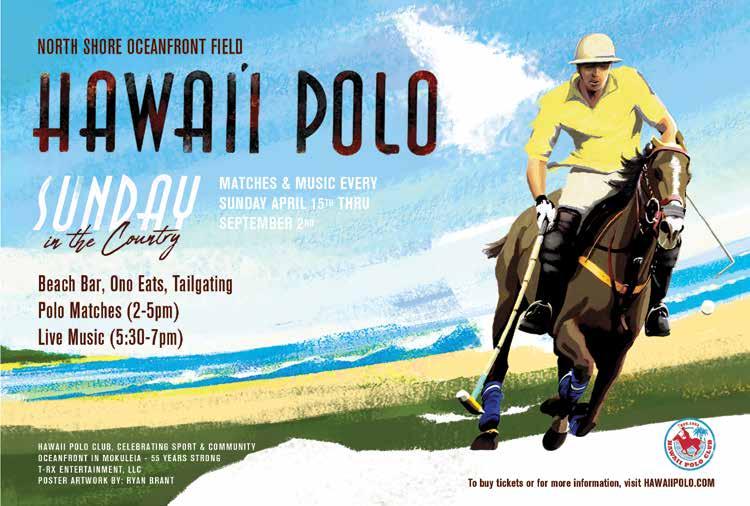

The CURRENT of HAWAI‘I Theme:

Volume 8 Issue 2 Features:

Living

Special Section: Kaka‘ako Redux Living, working,

walking in this growing Honolulu neighborhood. 0 02 > 09281 $14.95 US $14.95 CAN 25489 8

Tribes

and

TRIBES

Editor’s Letter

Contributors

FLUX PHILES

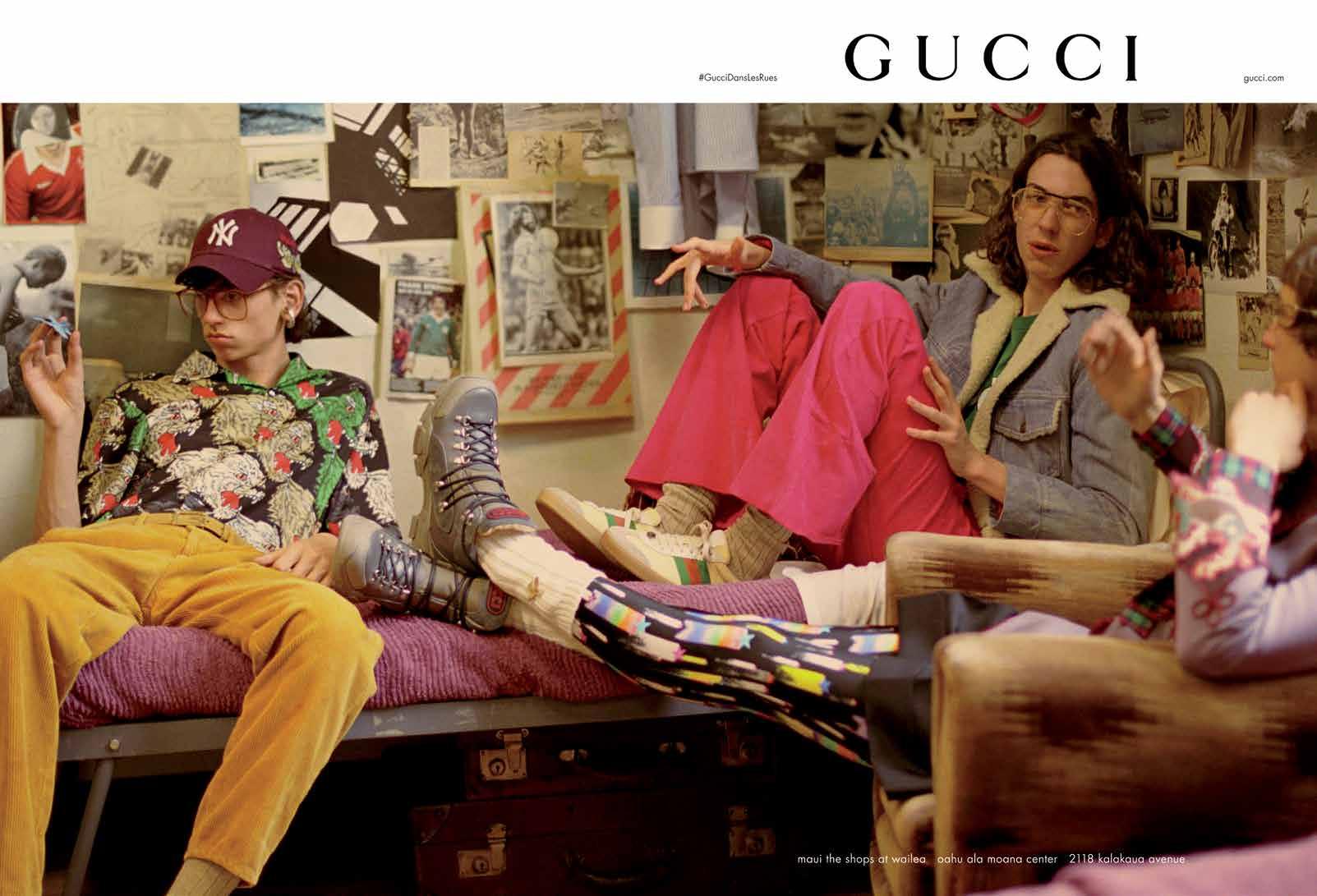

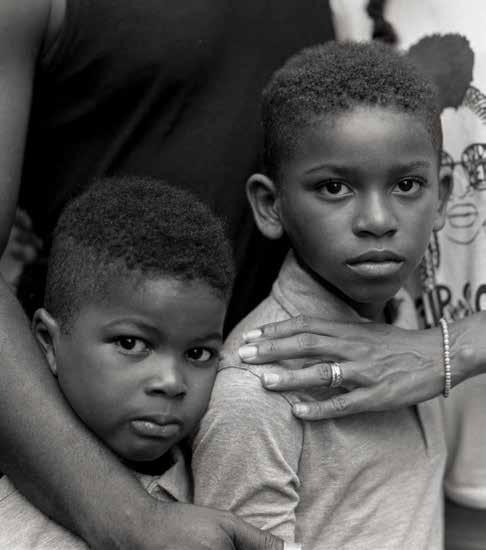

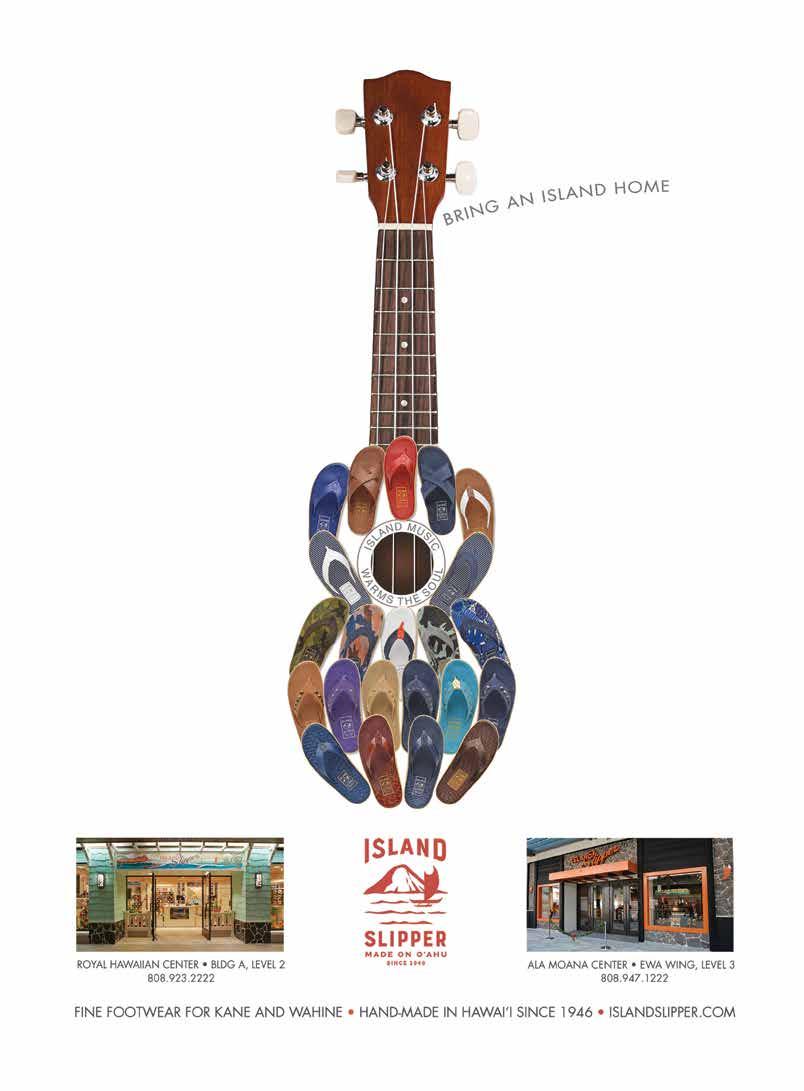

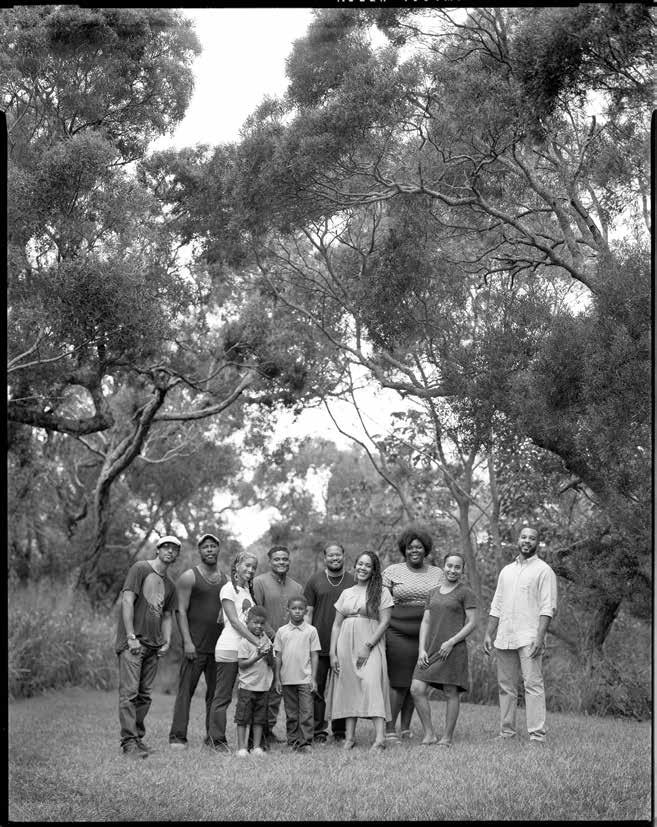

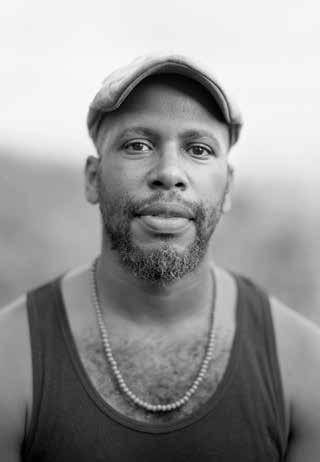

24 | Culture: The Pōpolo Project

36 | Science: The Hawaiian Crow

42 | Culture: Kānaka Rangers

48 | Arts: Kilohana Art League

A HUI HOU

192 | Waikīkī Beachboys

FEATURES

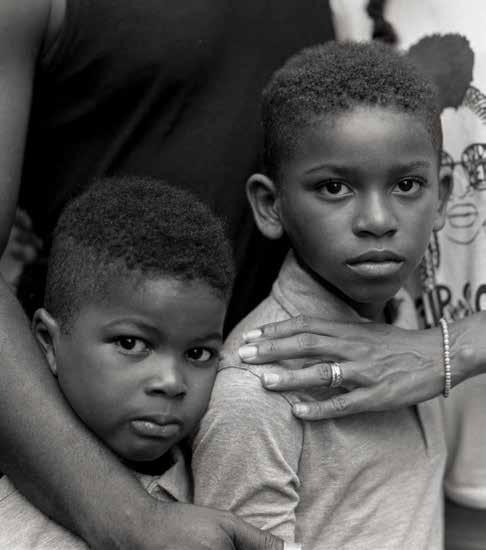

54 | A Place of Refuge

Rae Sojot ventures to Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae, Hawai‘i’s largest homeless encampment, to see how it has become a mecca for those who seek safe shelter, including the toddler shown above.

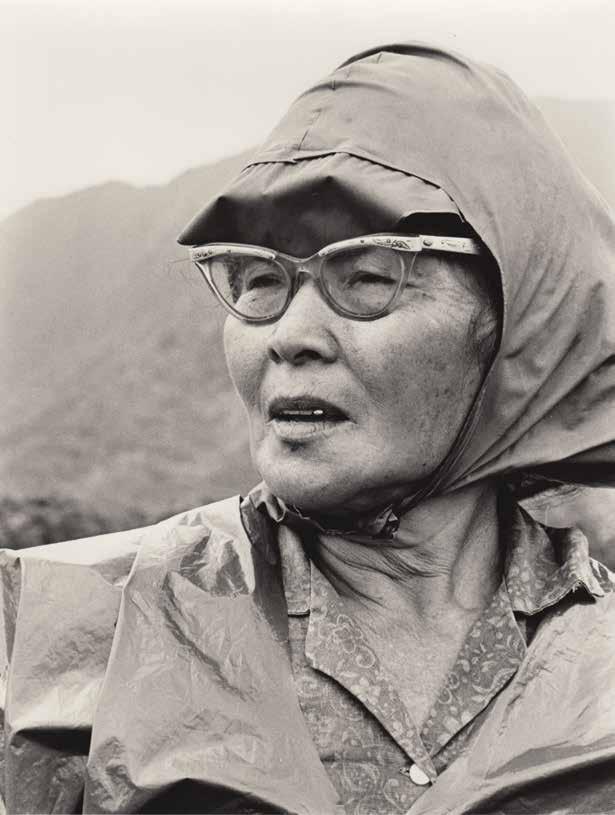

66 | Seniors Strike Back

Martha Cheng discovers how a community and its kūpuna are fighting to prevent a Kailua institution from being razed.

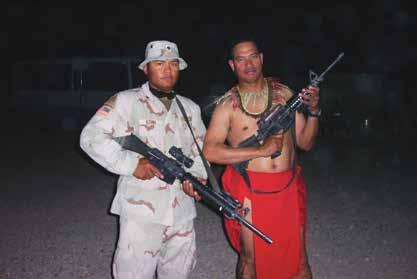

76 | Patriots Adrift

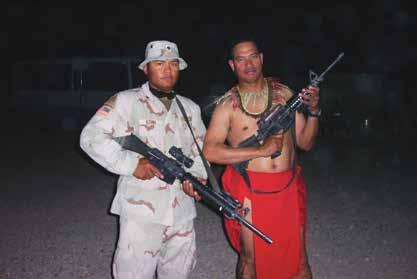

Despite not being U.S. citizens, Micronesians have risked their lives fighting for the United States. Timothy A. Schuler writes about how the unique immigration status of this group leaves them in limbo once they retire from service.

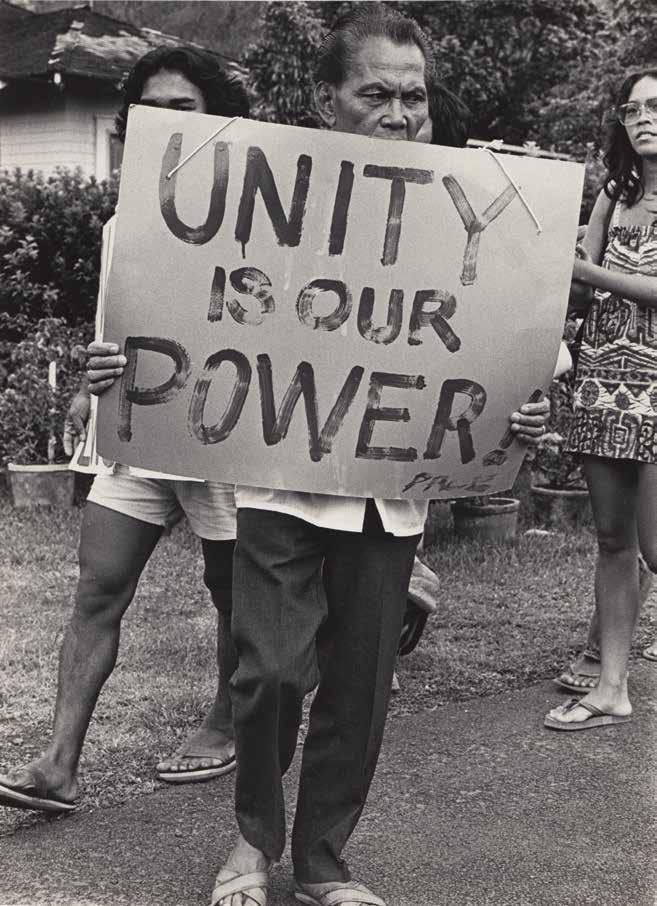

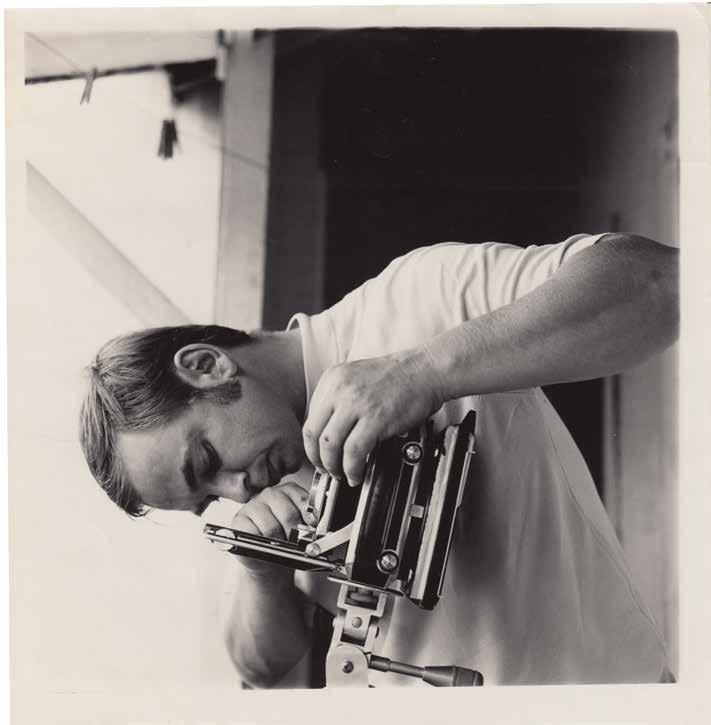

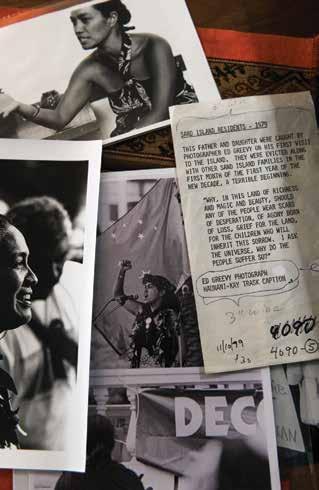

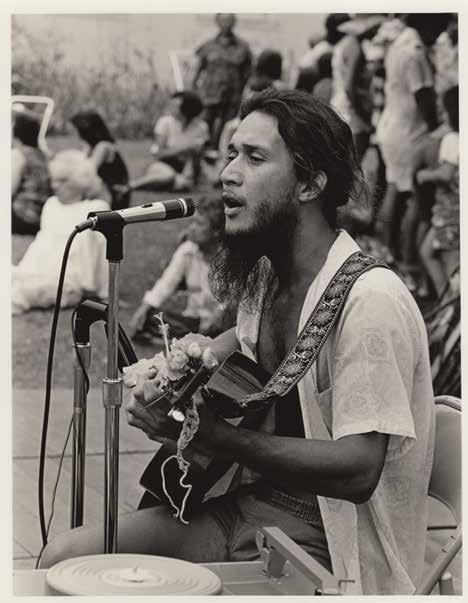

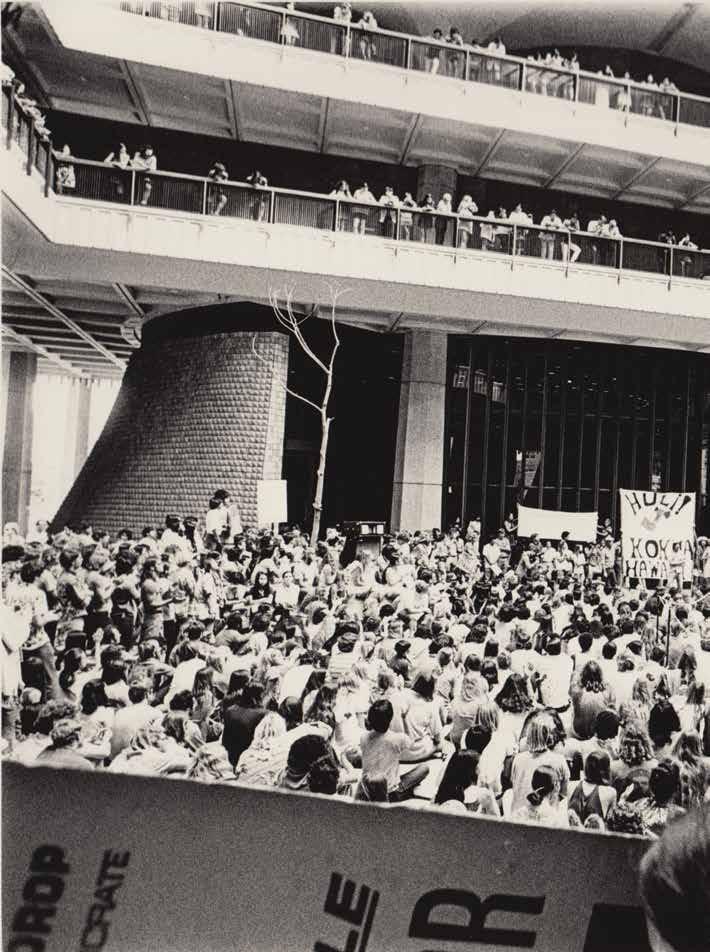

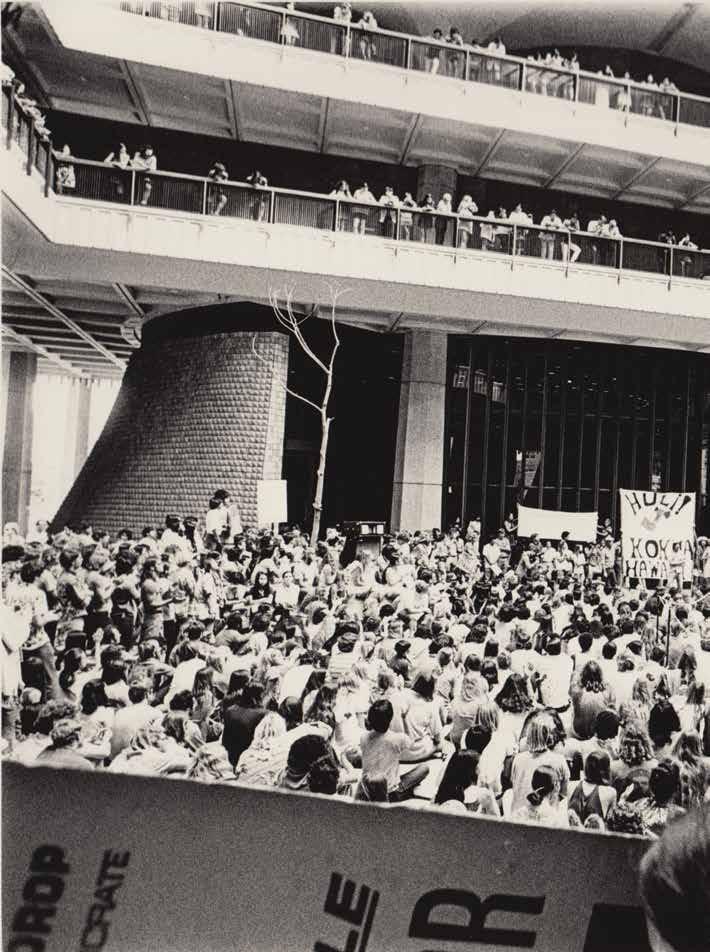

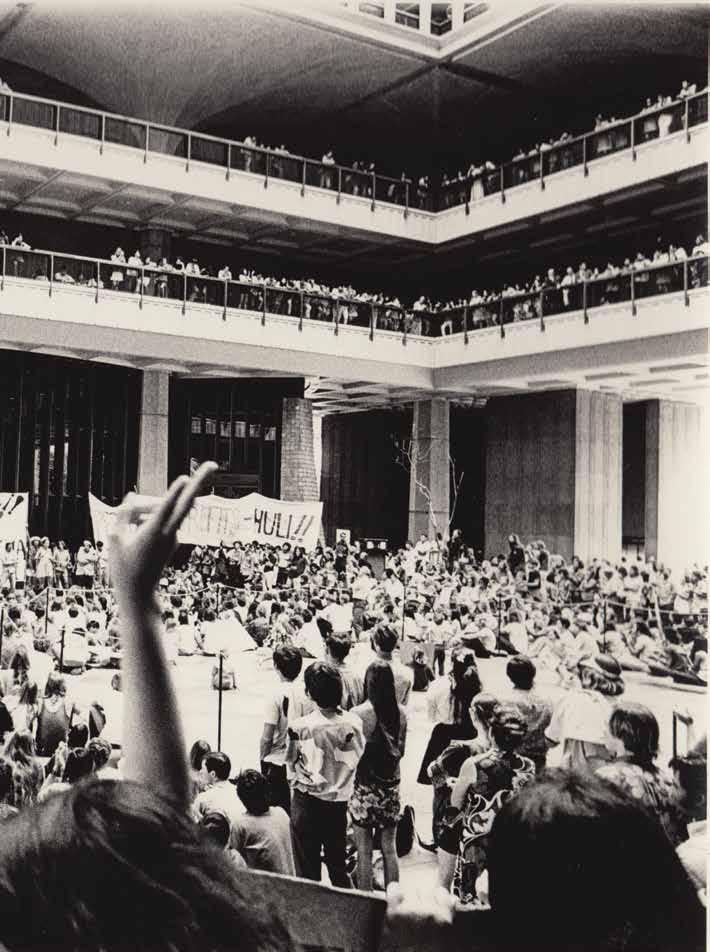

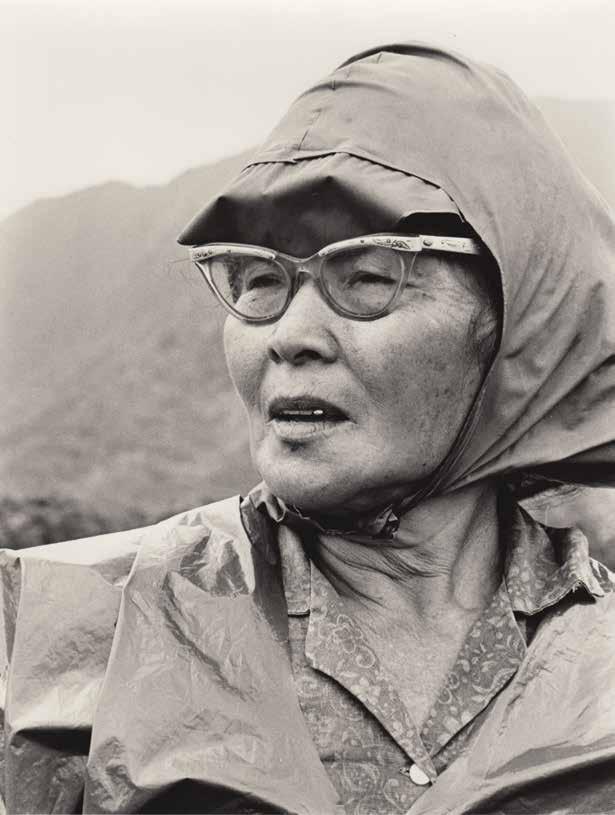

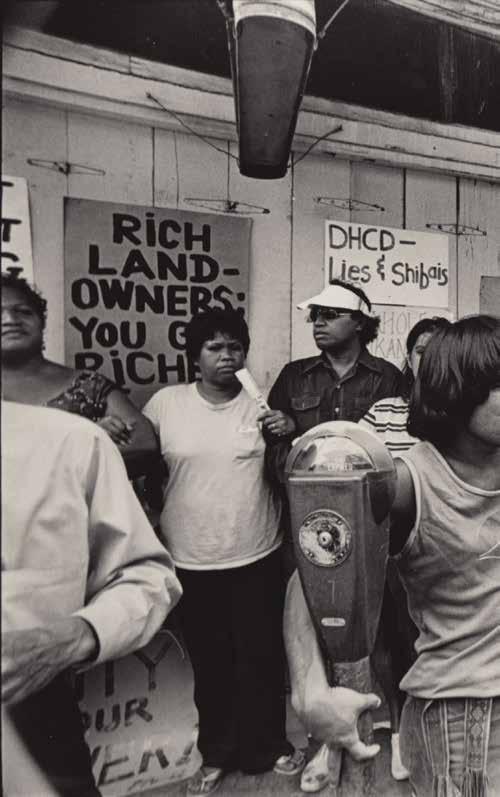

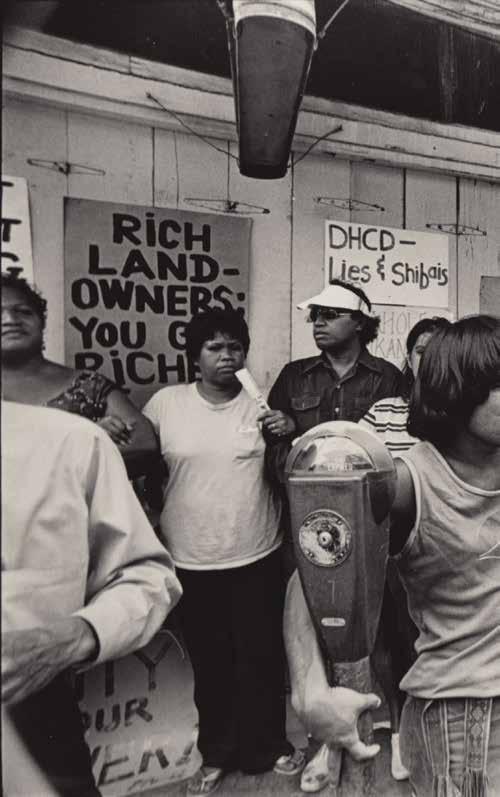

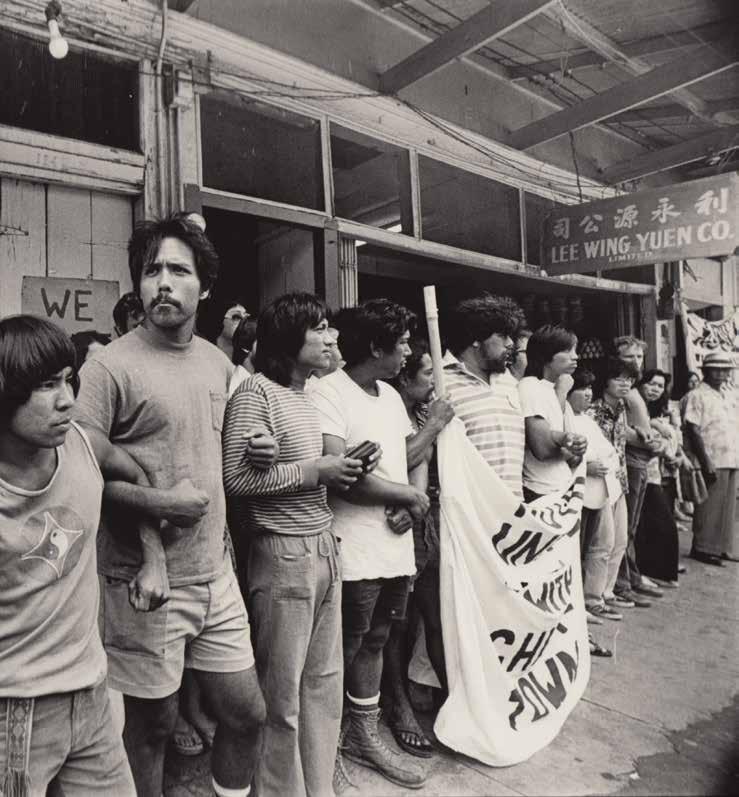

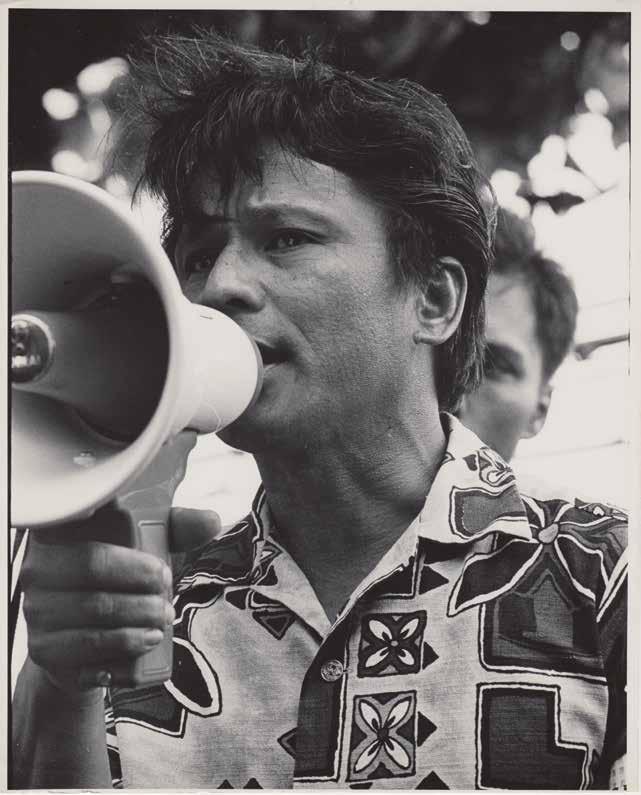

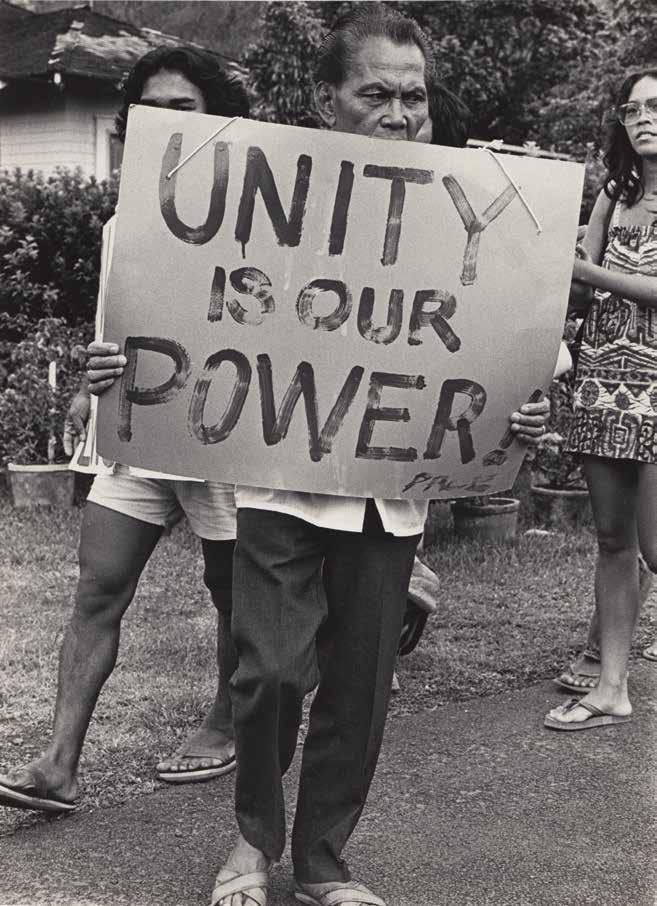

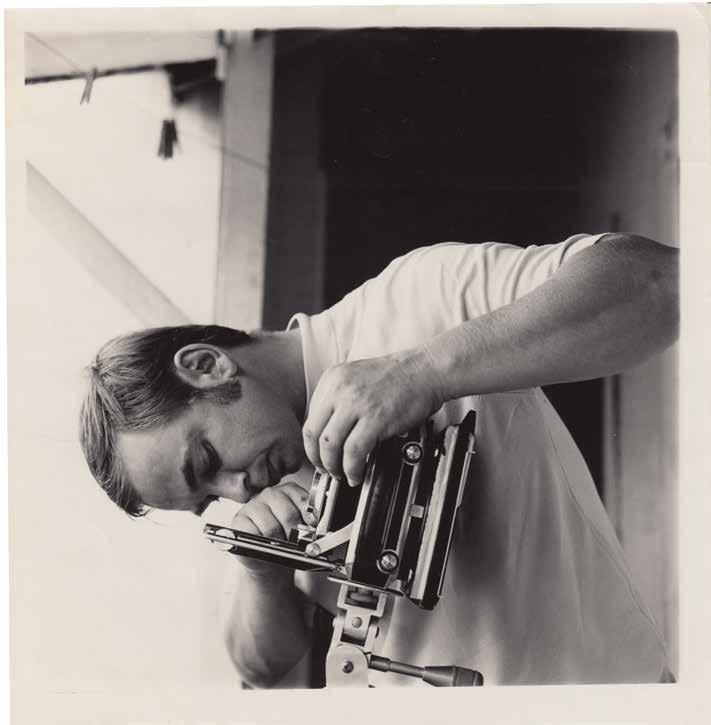

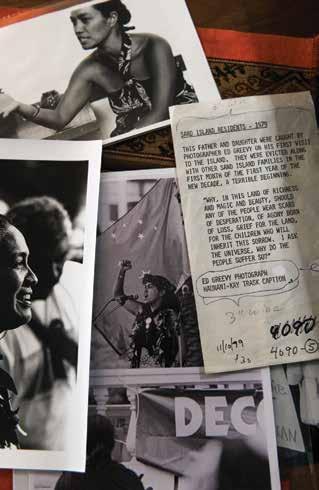

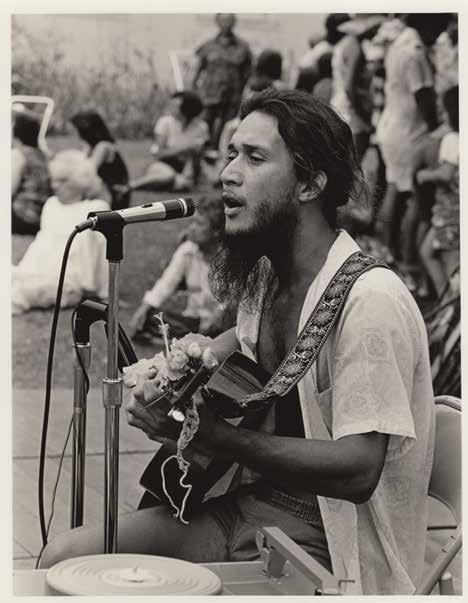

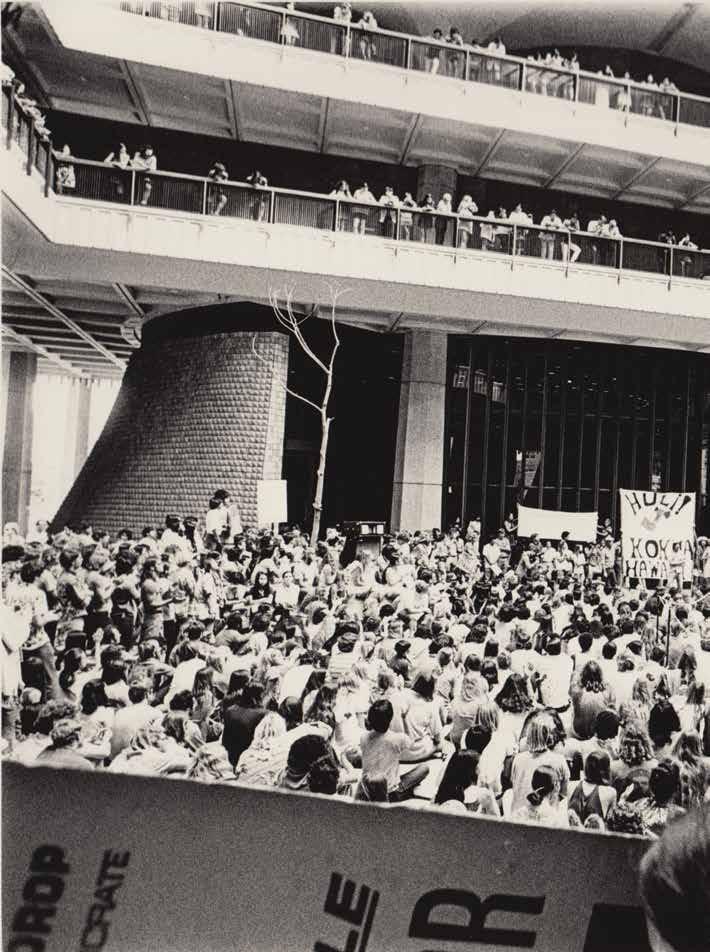

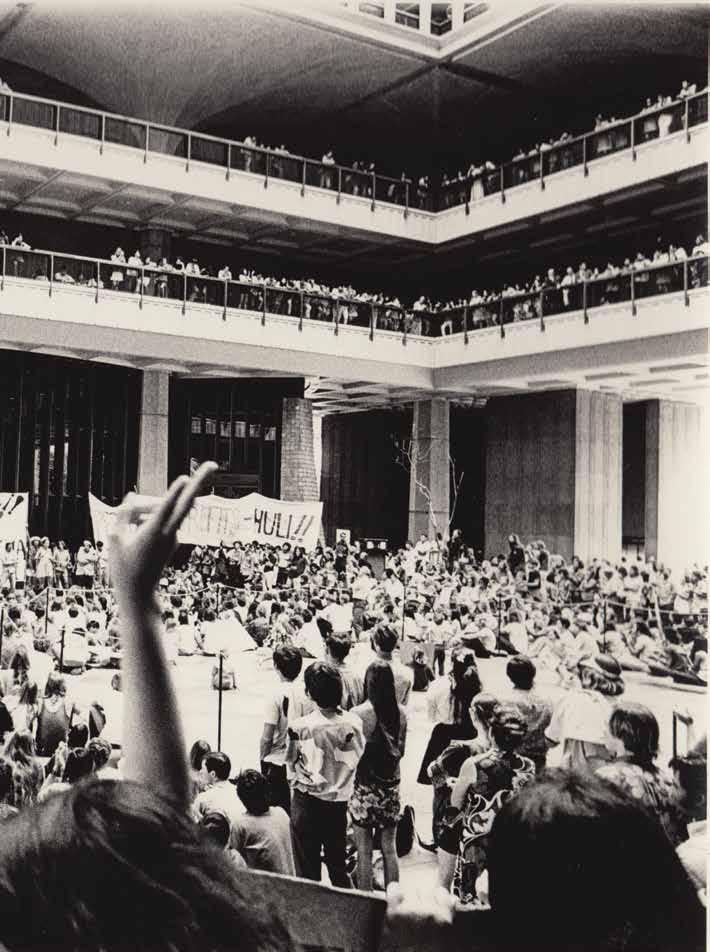

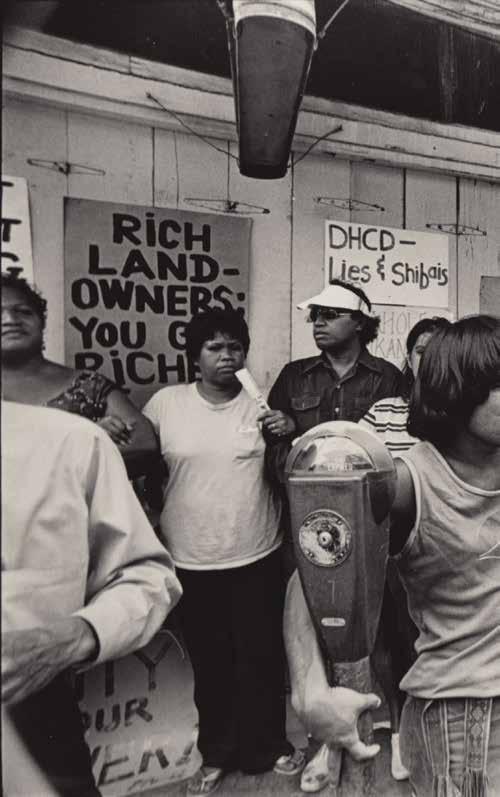

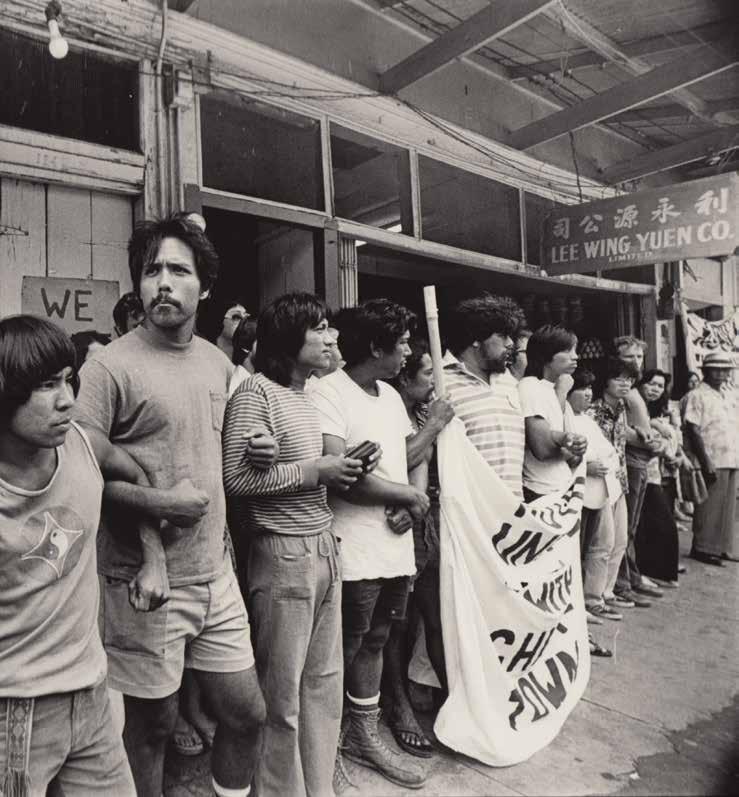

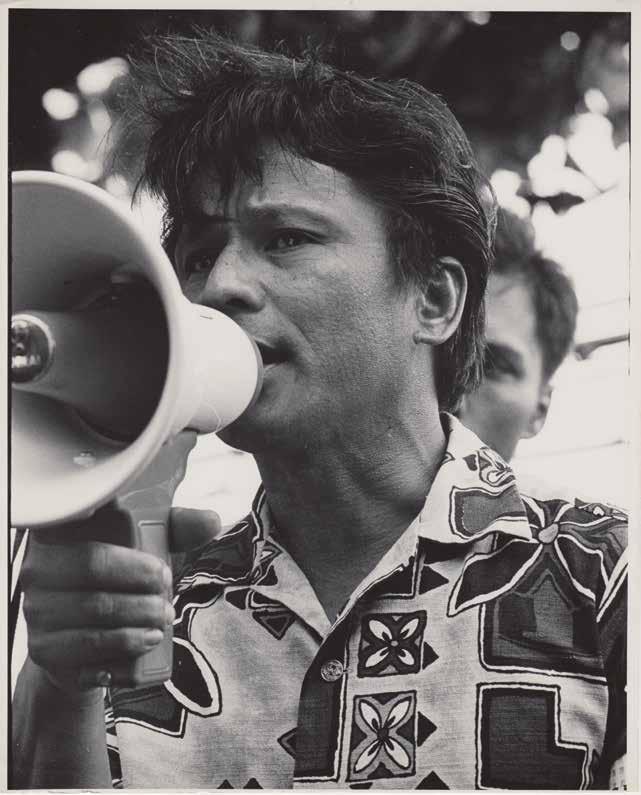

86 | The Witness

Matthew Dekneef examines the lasting impact of the work of Ed Greevy, who photographed land struggles and political strife in the Hawaiian Islands for more than three decades.

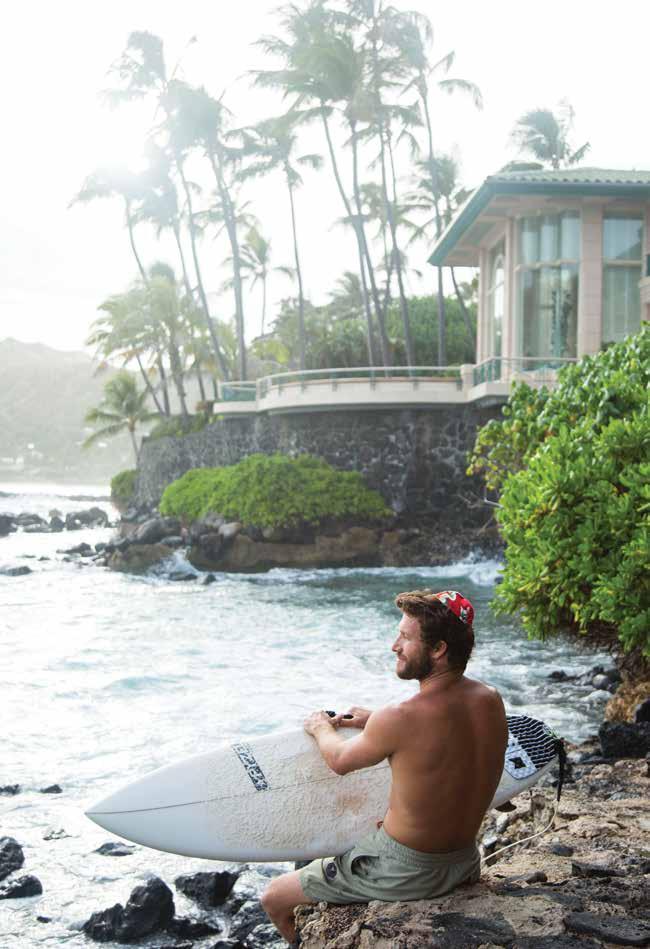

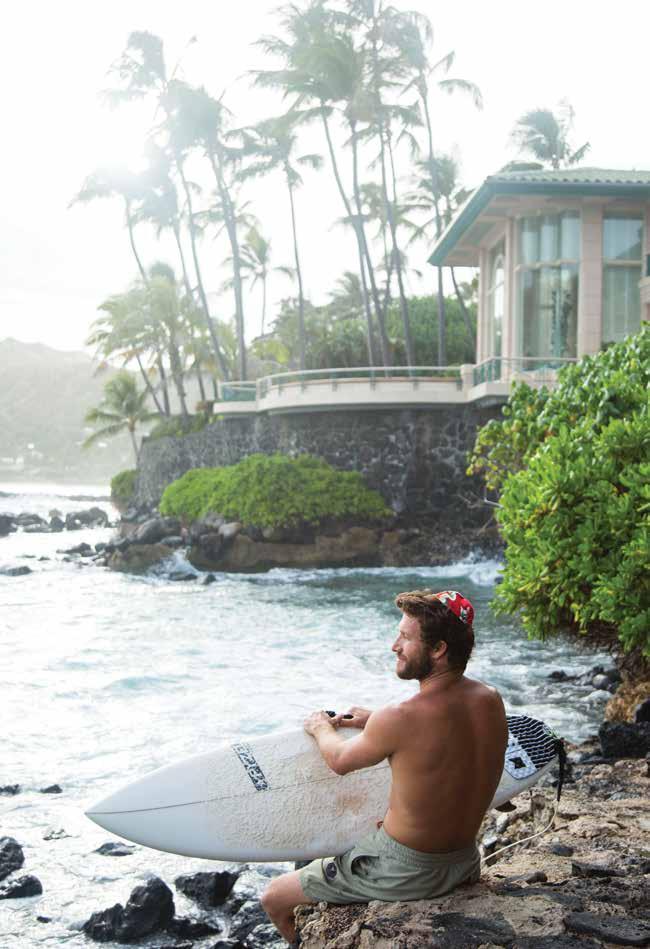

102 | Jew-ish

Beau Flemister journeys from land to sea to discover what it means to be Jewish in Hawaiʻi.

112 | Stranger Than Paradise

A photo essay by the anonymous Honolulu-based photographer known as @misterver captures the energy, color, and spontaneity of Waikīkī through the lens of his iPhone.

| FEATURES |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

22

TABLE OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS |

SPECIAL SECTION:

KAKA‘AKO

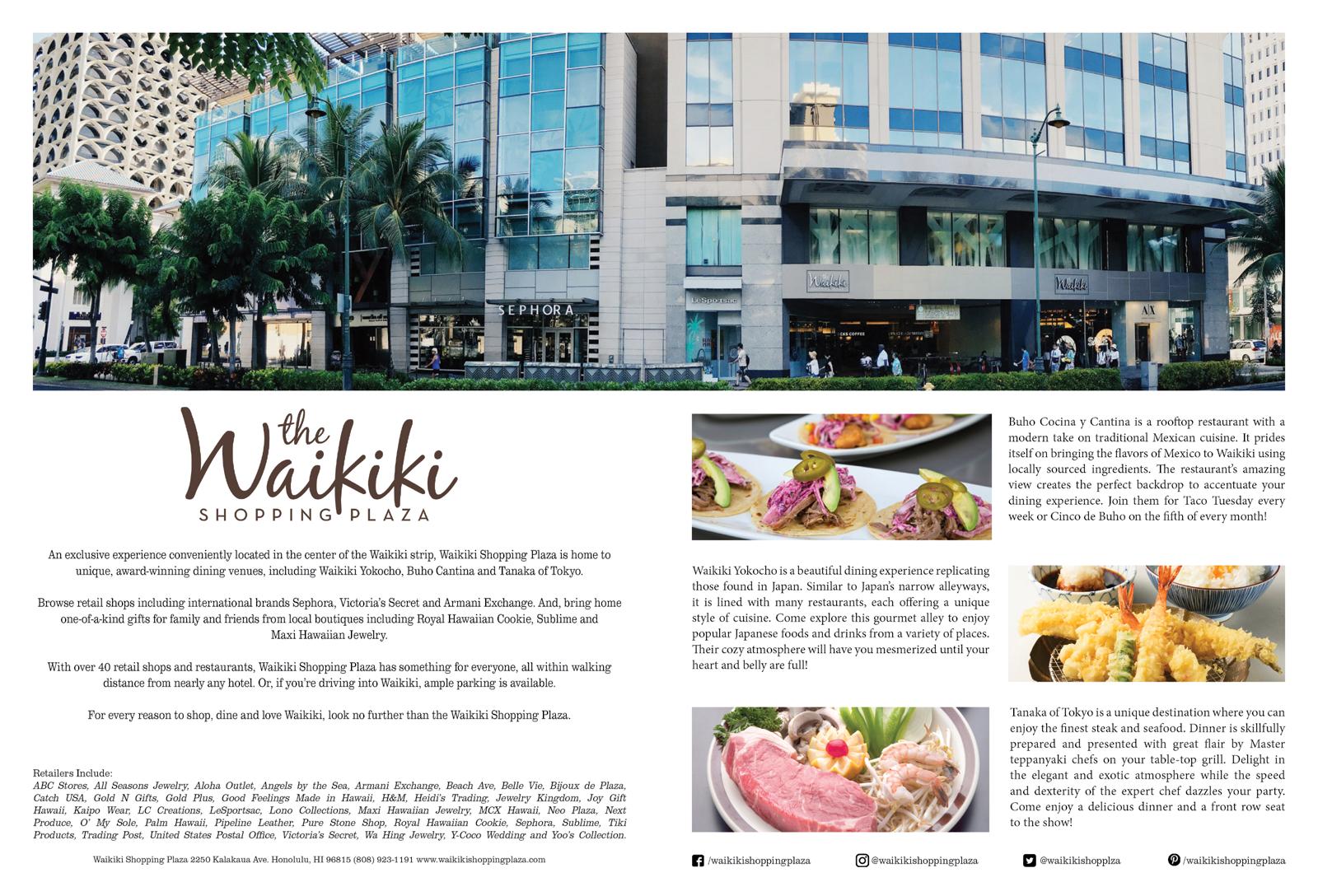

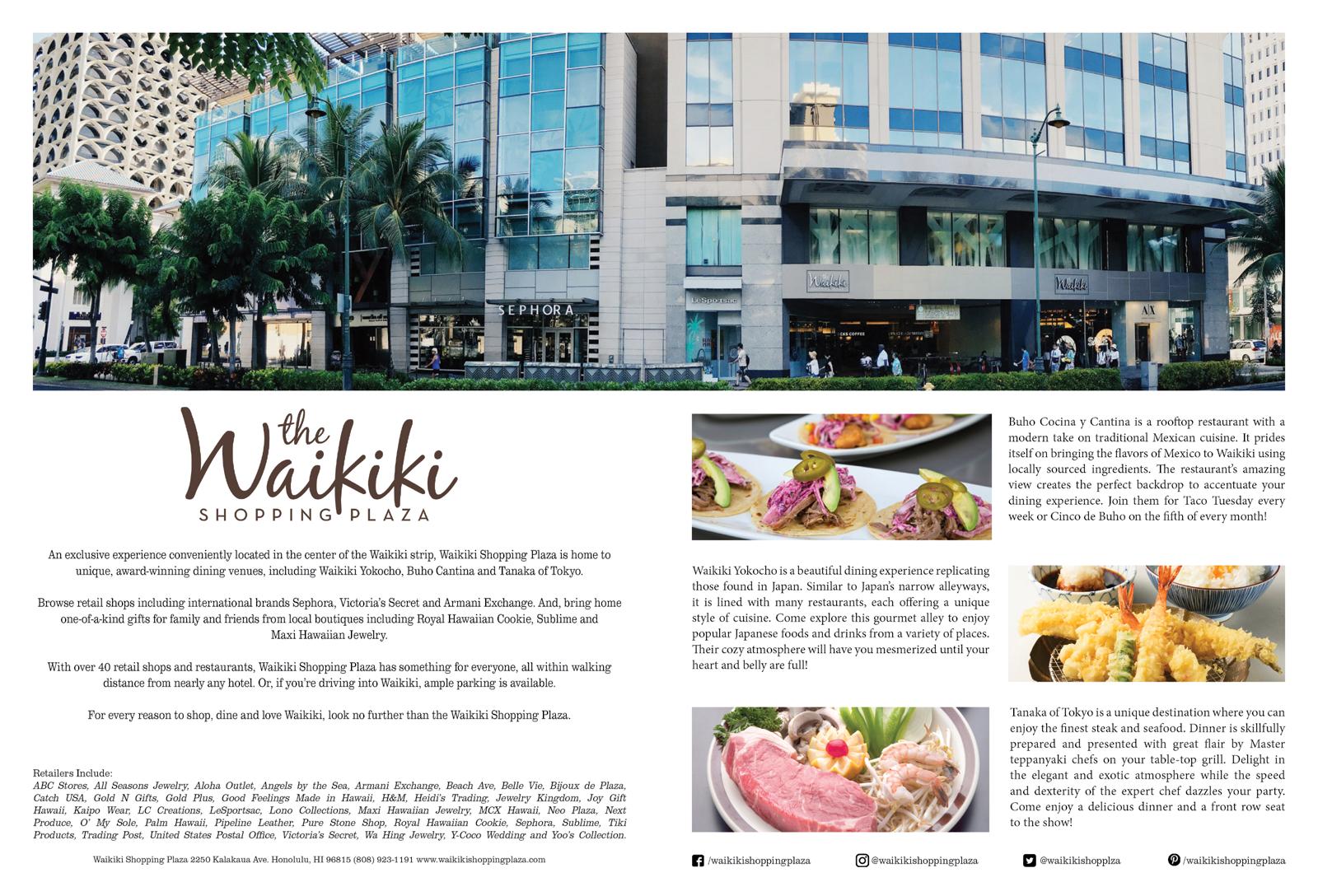

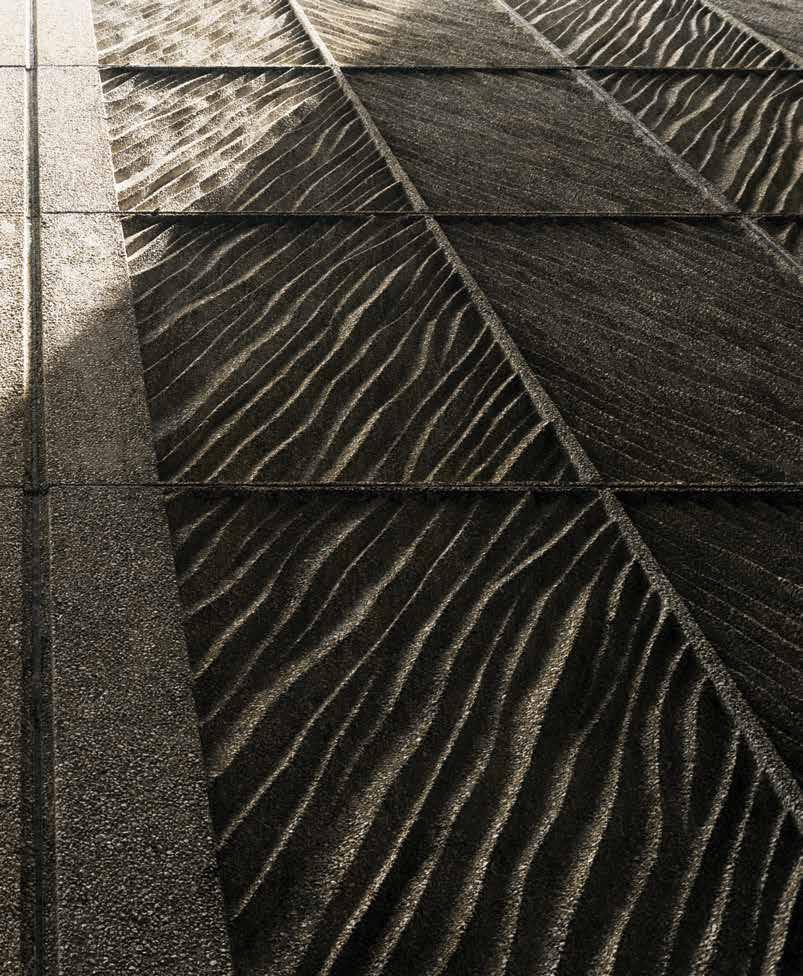

Living , working, and walking in the growing neighborhood of Kaka‘ako reveals the energy of its local community.

126

Shown left, Milo, a lifestyle boutique that shares a space with the popular café Arvo and floral shop Paiko, shown above.

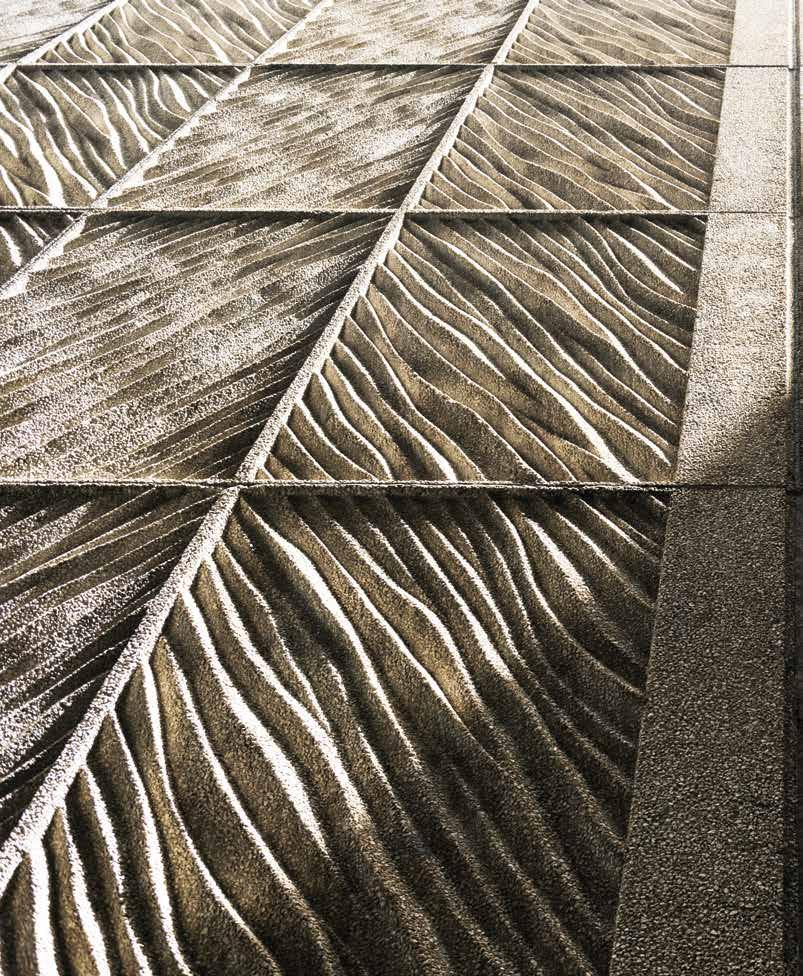

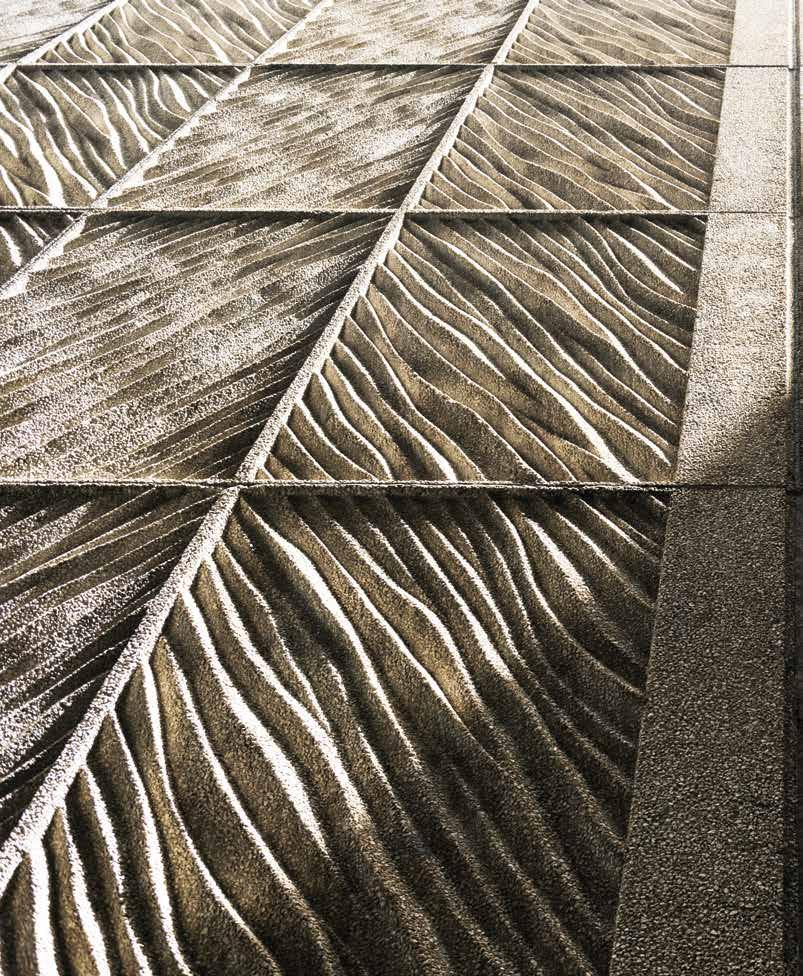

150 | Design Pāhiki Eco-Caskets

154 | Wellness

Maui’s Naturists

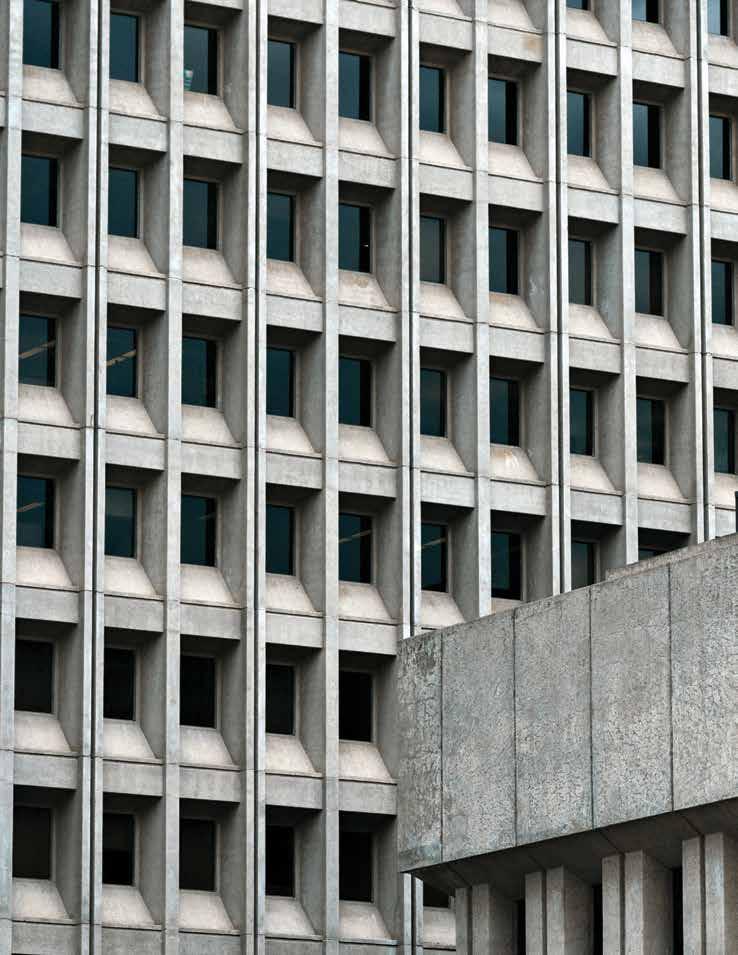

TABLE OF CONTENTS | SECTIONS | 162 EXPLORE

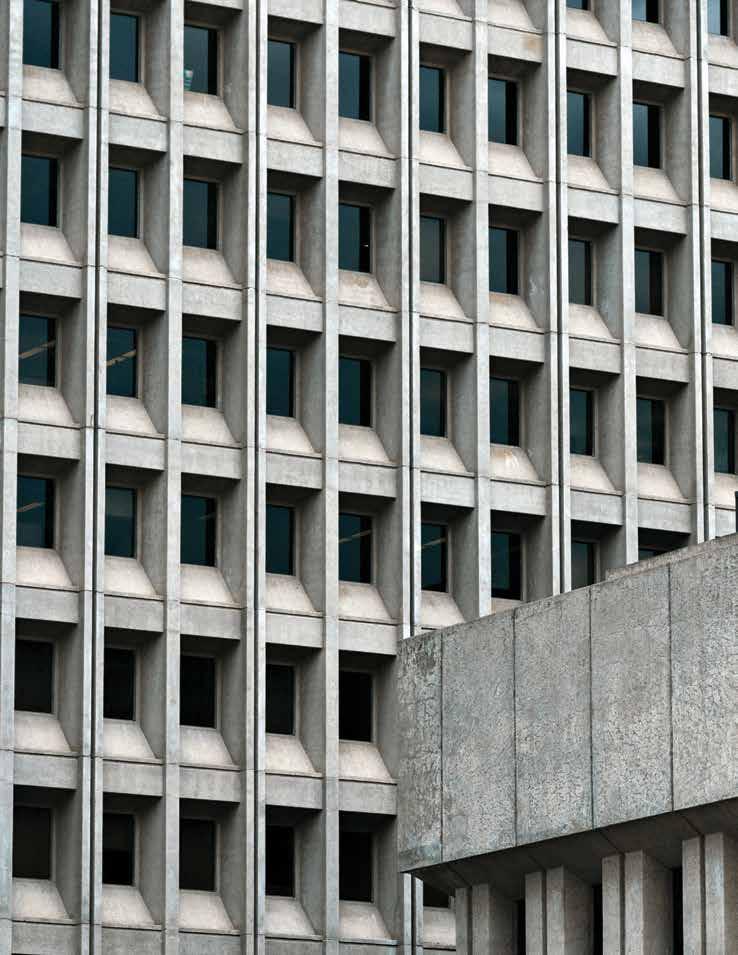

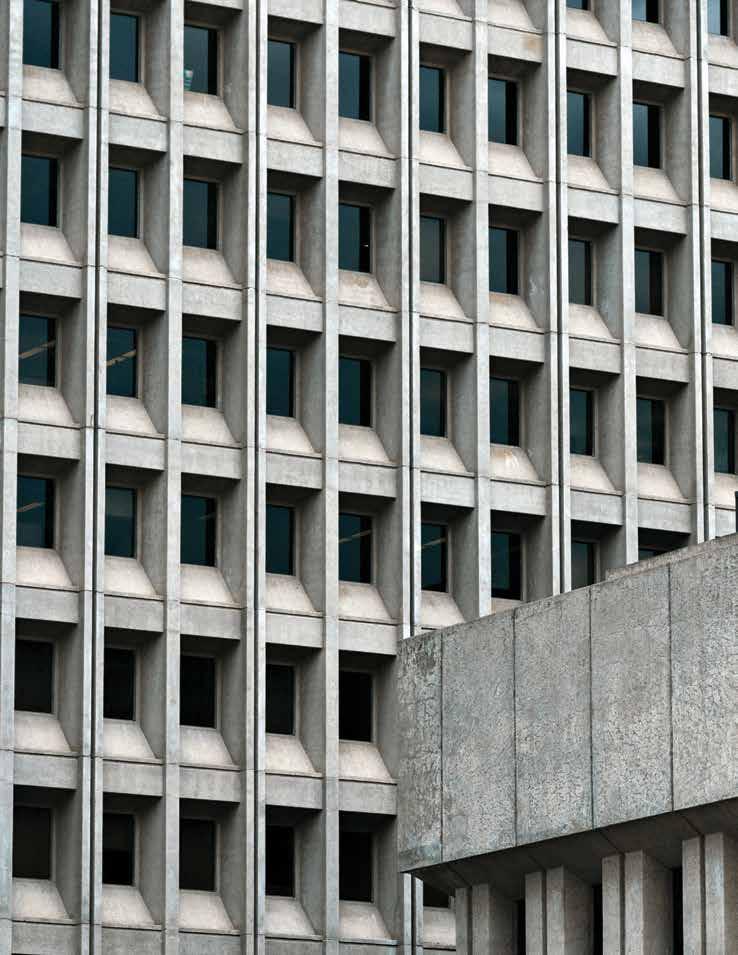

Architecture

Travel

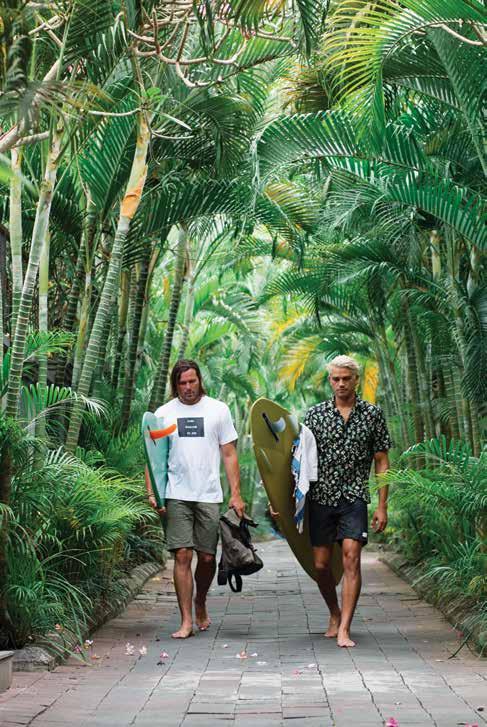

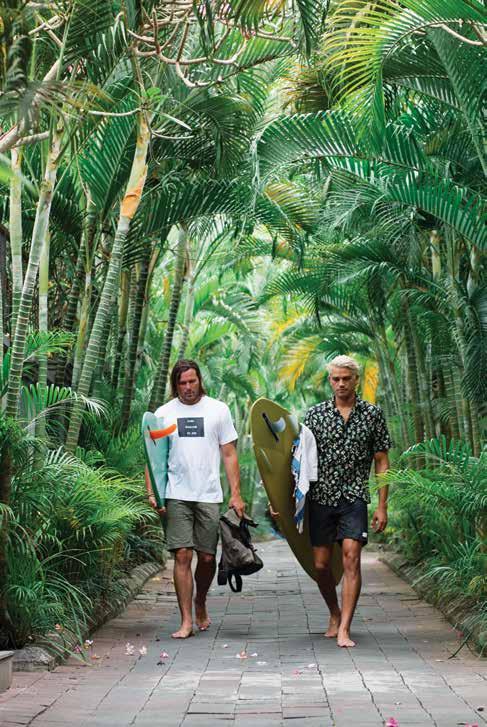

Indonesia 148 LIVING WELL

164 |

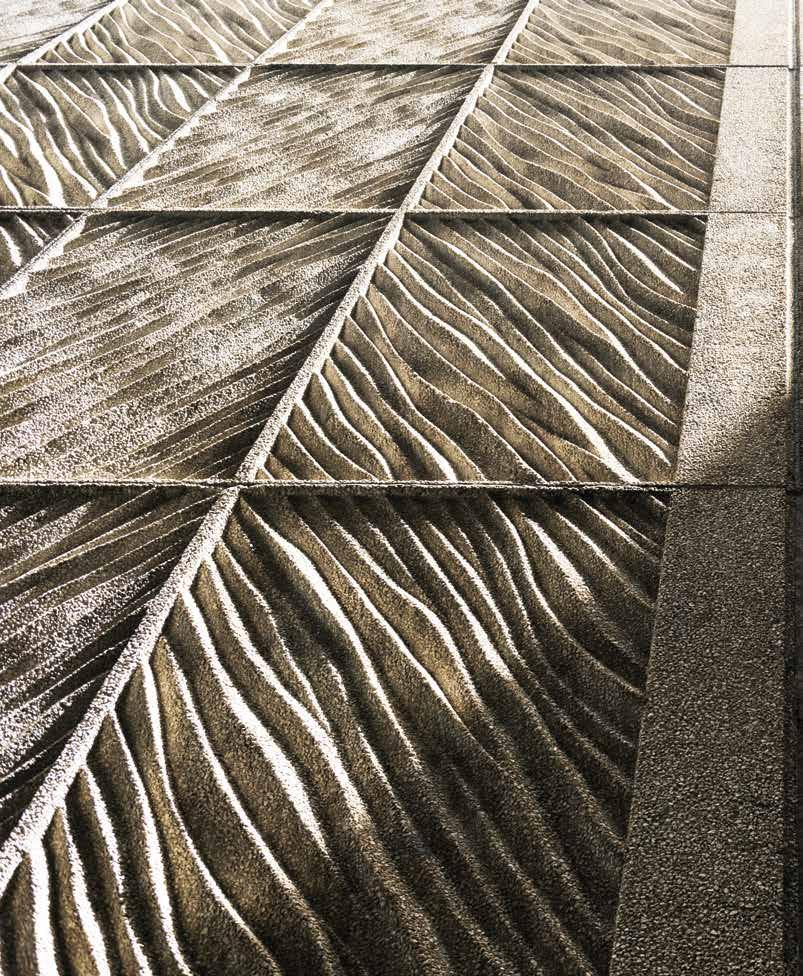

Hawai‘i Brutalism 180 |

Bali,

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Stay current on arts and culture with us at:

fluxhawaii.com

/fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaii

@fluxhawaiitravel

FLUX TV

The Legacy of Language

We chat with members of the Pōpolo Project about what it means to be black in Hawai‘i. “It’s really about creating a space for us to ask questions about what it means to be here, what it means to be in our bodies here, what it means to be representatives of our different lineages here,” says founder Akiemi Glenn.

Behind the Lens: Ed Greevy

For three decades, Ed Greevy documented peoples’ struggles over land in the Hawaiian Islands from the frontlines. We visit the photographer to discover how the the social movements of the 1970s to 1990s organized, resisted, and can be remade today.

|

FLUX TV |

EDITOR’S LETTER | TRIBES |

In July 2017, Andres Magaña Ortiz was deported to Mexico after living nearly 30 years in Hawai‘i.

Ortiz was one of Kona’s most respected coffee farmers, working his way from a coffee picker as a teenager to owning his own farm and helping others run their farms as an adult. He even aided the U.S. Department of Agriculture in combating the spread of the coffee berry borer, which threatened to wipe out Hawai‘i Island crops in 2010. But Ortiz was also in the country illegally, having been smuggled across the border in 1989 at age 15 to join his mother, who was living in California. When President Trump took office in November 2016, he vowed to make immigration a landmark part of his agenda, and Ortiz became one of the first in Hawai‘i to feel the effects of Trump’s immigration crackdown. When he left for Morelia, Mexico, a place he has not known for most of his life, he left behind his wife and three children, who are all American citizens.

It was during this time that the idea for the Tribes-themed issue was born, when the country was roiled—and still is—in a debate over immigration. Though Hawai‘i can often feel removed from the effects of what’s happening around the country, Ortiz’s case brought the reality of these new immigration policies into stark focus.

It’s hard not to compare the country’s new immigration tactics with the orders that swept up people groups and shoved them into internment camps on the basis of race during World War II. During that time, citizens who were at least 1/16 Japanese were given just six days notice before they were taken with only what they could carry to isolated relocation centers around the country—upwards of 120,000 people in total, including 17,000 children under 10 and thousands of elderly.

Seven decades later, in June, the Supreme Court upheld Trump’s Muslim travel ban on the grounds of

national security, while simultaneously overturning Korematsu v. United States, the 1944 ruling that upheld the forcible detainment of JapaneseAmerican citizens. In response, UCLA law professor Hiroshi Motomura, who has written extensively on immigration and citizenship, stated in The New York Times, “Overruling Korematsu the way the court did in this case … is deeply troubling, given the parts of the reasoning behind Korematsu that live on in today’s decision: a willingness to paint with a broad brush by nationality, race or religion by claiming national security grounds.”

When we ignore the nuances of any given situation, we run the risk of decaying into what Utah senator Orrin Hatch described as “a divided country of ideological ghettos.” But we may already be there. According to the Pew Research Center, Republicans and Democrats are more ideologically divided than they have been in the last two decades, and both parties increasingly view the other as a threat to the nation’s wellbeing.

During World War II, my grandfather served along with other men from the Hawai‘i National Guard in the 100th Infantry Battalion (nicknamed the “Purple Heart Battalion” for the high number of men injured in combat), which later joined forces with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. Composed primarily of Japanese-American soldiers, this regiment would become the most decorated unit in American military history, while the country sanctioned what many today view as one of the most heinous violations of civil rights in 20th century America. In one of the most famous acts of valor, soldiers from the 100th/442nd charged through enemy fire in the Vosges Mountains in France to rescue men from the 141st Texas Infantry Regiment, who had

been surrounded by German forces. Over six days of fierce combat, my grandfather, a medic, braved enemy fire to drag wounded soldiers out of the forest. Eventually, the 100th/442nd combat team would save 211 of the 275 Texans, but not before losing hundreds of men in the rescue.

My grandfather died of cancer before I got the chance to meet him, but I know that he risked his life in service of others because he refused to let the government’s assumptions about his loyalty, his identity, define who he was or what he believed in. Like the men in my grandfather’s unit, who banded together in solidarity amid discrimination that tore lives apart, the people featured in this issue show us that tribes can bind us to one another, helping us to inch forward in unity amid a divided society.

We see this on vibrant display in the formation of the Pōpolo Project, whose members, part of a group that makes up less than 4 percent of Hawai‘i’s population, reappropriated a term of derogation into one of power; in the community of Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae, whose formerly homeless inhabitants strode down a path to a place of purpose and belonging; in the legacy of Ed Greevy, whose images documented the people and purpose of social movements from a few decades past that still have the power to unite us again today. And while it would be all too easy to hunker down and indulge the tribes of people that look, sound, and think like we do, it is only when we venture out from beyond the barriers that separate us that battle lines can truly be broken.

With aloha,

Lisa Yamada-Son EDITOR lisa@nellamediagroup.com

MASTHEAD | TRIBES |

What is a tribe that shaped you in your youth?

“Growing up as an immigrant, there was a pressure to hide my Filipino culture. But my family resisted the urge to be Americanized. Understanding my heritage reminds me to never forget where I’ve come from. I’ve realized the identity that others wanted me to be ashamed of is integral to who I am.”

PUBLISHER

Jason Cutinella

EDITOR

Lisa Yamada-Son

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Ara Feducia

MANAGING EDITOR

Matthew Dekneef

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

Anna Harmon

SENIOR EDITOR

Rae Sojot

DESIGNERS

Mitchell Fong

Michelle Ganeku

JUNIOR DESIGNER

Skye Yonamine

PHOTOGRAPHY DIRECTOR

John Hook

PHOTO EDITOR

Samantha Hook

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Eunica Escalante

CREATIVE ASSISTANT

Naz Kawakami

“My Japanese family tribe has shaped my cultural identity from an early age by sharing traditions, language, and core values with me. For instance, my mother made up the kanji to the name she gave me, Naoko, which literally means ‘child of seven promises/values.’”

IMAGES

Marie Eriel Hobro

Cidney Kelly

Kyle Kosaki

Lila Lee

@misterver

Kainoa Reponte

IJfke Ridgley

Chris Rohrer

Wolf & Woman

CONTRIBUTORS

Martha Cheng

Beau Flemister

Travis Hancock

Cash Lambert

Kelsie Pualoa

Timothy A. Schuler

ADVERTISING

Mike Wiley

GROUP PUBLISHER mike@nellamediagroup.com

Francine Beppu

NETWORK STRATEGY DIRECTOR francine@NMGnetwork.com

Chelsea Tsuchida

MARKETING & ADVERTISING EXECUTIVE

Kylee Takata

ADVERTISING ASSISTANT

Hunter Rapoza

MARKETING & SALES COORDINATOR

©2009-2018 by Nella Media Group, LLC. Contents of FLUX Hawaii are protected by copyright and may not be reproduced without the expressed written consent of the publisher.

OPERATIONS

Joe V. Bock

CHIEF REVENUE OFFICER joe@nellamediagroup.com

Gary Payne VP ACCOUNTS RECEIVABLE gpayne@nellamediagroup.com

Courtney Miyashiro OPERATIONS ADMINISTRATOR courtney@nellamediagroup.com

MEDIA

Gerard Elmore LEAD PRODUCER gerard@NMGnetwork.com

Kyle Kosaki VIDEO EDITOR

Shaneika Aguilar JUNIOR VIDEO EDITOR

Aja Toscano

NETWORK MARKETING COORDINATOR

INTERN Kylie Yamauchi

General Inquiries: contact@fluxhawaii.com

“I loved movies, video games, TV, and I wasn’t part of the cool kids (read: limited friends). Then I got into hip-hop, and I freestyled using pop-culture references and became a breaker, using aspects of what I learned from doing wrestling and judo in high school. Here, I finally found myself.”

PUBLISHED BY:

Nella Media Group 36 N. Hotel St., Ste. A Honolulu, HI 96817

FLUX Hawaii assumes no liability for products or services advertised herein.

FLUX Hawaii is a triannual lifestyle publication. ISSN 2578-2053

CONTRIBUTORS

On the Cover

A portrait of artist Nicole Maileen Woo photographed at Pu‘u‘ōhiʻa (also known as Mount Tantalus) by Chris Rohrer. Woo is a member of The Pōpolo Project, which was started by Akiemi Glenn as a way to discuss the black experience in Hawai‘i. Pōpolo—the Hawaiian name of an indigenous herb with edible black berries—is sometimes used in the islands plainly as a marker of black race, but it can also hold racist connotations. By reappropriating its usage, the word becomes a tool of empowerment. “Art holds the transformative ability to tell the stories of the marginalized with resounding voice and vigor,” Woo says. “Yet for any story to be heard, a platform is crucial. The Pōpolo Project is such a platform.” Read about the group on page 24.

Marie Eriel Hobro

Marie Eriel Hobro is a documentary photographer and filmmaker from leeward

O‘ahu who is part of Wolf & Woman, a documentary media collective for women, people of color, and LGBTQ creatives in Hawai‘i. Nearly every weekend, she and other members of the collective teach photography to youth from Leilehua High School and Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae.

“People can learn a lot from Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae,” says Hobro, whose photos of the encampment are featured in “A Place of Refuge” on page 54. “Some people who go to Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae flee from situations where they feel like they don’t belong, but the familial bonds of the village help them gain that feeling back.

Even if they don’t have a lot of material things, the people there always make sure to give back and help others. They practice a lot of what’s missing in our current society, and I think that everyone can learn something from them.”

@misterver

Since joining Instagram in 2012 as @misterver, the anonymous Honolulubased photographer has been capturing the constant energy, color, and spontaneity of O‘ahu’s streets—all through the lens of his iPhone. In the photo essay “Stranger Than Paradise” on page 112, the candid consumerism that runs throughout the city is observed. “The tourism industry forces us to look at Waikīkī in a certain way, and I’m always trying to find new ways to frame the usual,” the photographer says via email. “Waikīkī is a lifelong dream to some and an everyday existence to others. It’s interesting how travel can separate people from their group or tribe yet helps them to define it when stepping out in a new environment.”

Timothy A. Schuler

Originally from Kansas, Timothy A. Schuler usually writes about design, ecology, and the natural environment. For the feature “Patriots Adrift” on page 76, Schuler found that a tribe can be elastic and inclusive. “Since the 2016 presidential election, it seems as if we’ve watched America become a nation of warring tribes,” he says. “Writing about Micronesian islanders serving in the U.S. military, I realized that these men and women might have been the ultimate outsiders, foreigners fighting for a nation not their own, and yet I heard story after story of walls coming down, not being built up. To me, it proved that tribal lines can be redrawn. We just have to find those things that unite us.”

| TRIBES |

When developers threatened to raze their beloved bowling alley, Kailua seniors fought back. Image by IJfke Ridgley.

When developers threatened to raze their beloved bowling alley, Kailua seniors fought back. Image by IJfke Ridgley.

TRIBES

“Don’t feel like you have to intervene. Just shut up and listen.”—Ed Greevy

The Lineage of Language

The Pōpolo Project asks that we start with one word and tell a new story.

TEXT BY KELSIE PUALOA

IMAGES BY CHRIS ROHRER

pō.polo (n.)

1. The black nightshade (Solanum nigrum, often incorrectly called S. nodiflorum), a smooth cosmopolitan herb, 0.3 to 0.9 meters high. It is with ovate leaves, small white flowers, and small black edible berries. In Hawai‘i, young shoots and leaves are eaten as greens, and the plant is valued for medicine, formerly for ceremonies. Also polopolo. The fruit is hua pōpolo. Because of its color, pōpolo has long been an uncomplimentary term: see lepo pōpolo.

— Hawaiian Dictionary by Mary Kawena Pukui and Samuel H. Elbert

Jarmila Jarmon says her skin carries a lot of history. She grew up in Salt Lake and Pacific Palisades on O‘ahu, and recalls moments of feeling like “the only one.” When slavery was discussed in class, she says, “People would look at you and ask, ‘What do you think about that?’” Jarmon wanted to talk to other local kids about these things, but there weren’t many kids like her. She also felt her experiences seemed too manini, or small, to discuss with her parents, who lived in North Carolina during the Jim Crow era. Years later, she feels like she has found a group with whom she can share her experiences as a black person: the Pōpolo Project.

Akiemi Glenn, the 37-year-old executive director of the Pōpolo Project, says she started the project in 2015 as a way to learn about the black experience in Hawaiʻi after moving to Honolulu from New York. The black community represented less than 4 percent of Hawaiʻi’s population, according to the 2016 U.S. Census, and Glenn wanted to support her community by creating a space where people could talk about their stories and culture.

“We don’t necessarily have an agenda or really want to be able to have a definitive representation of the black experience in Hawaiʻi,” Glenn says of the Pōpolo Project, which has since grown into a collective of community members with a board of directors. “It’s really about creating a space for us to ask questions about what it means to be here, what it means to be in our bodies here, what it means to be representatives of our different lineages here.”

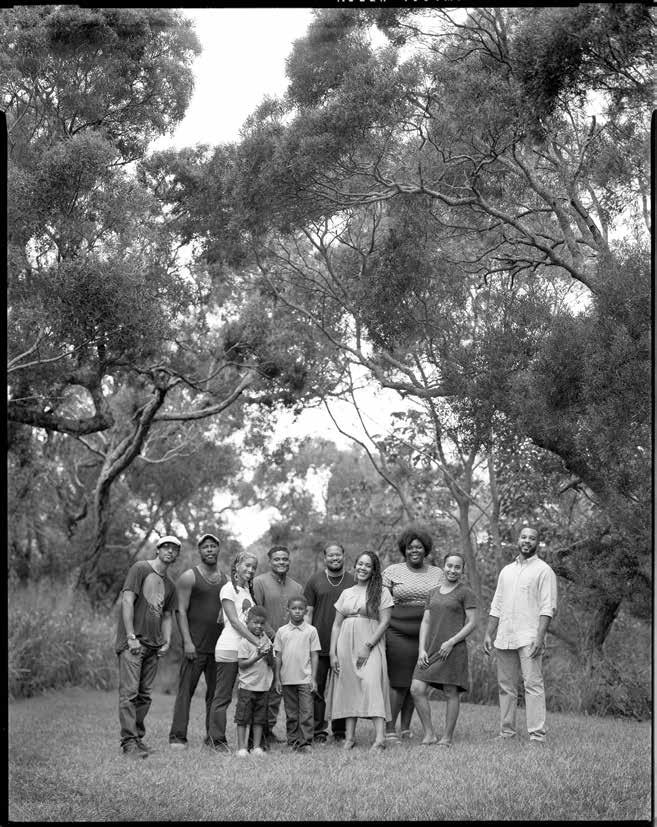

Started by Akiemi Glenn, shown fourth from the right, the Pōpolo Project examines what it means to be black in Hawai‘i.

FLUX PHILES | CULTURE | 24 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

When Pōpolo Project members talk about their experiences, there is a palpable sense of relief, a meditative exhale in the midst of tension. The opportunity to do so is one some have not had before. Throughout the year, and especially in February (Black History Month) and August (Black August), the Pōpolo Project holds events like film screenings with panel discussions or art exhibits featuring works by members. Glenn continues to seek out stories of black people in the islands and gather research about black history in Hawaiʻi. (The resulting Pōpolo Syllabus is available on the group’s website.)

At early Pōpolo Project events, people shared their painful histories with the word “pōpolo.” Also the Hawaiian name of an indigenous herb with rounded leaves, white flowers, and edible black berries, time and context have given the word an uneasy racialized weight. Although “pōpolo” is sometimes used plainly as a

marker of black race, people told Glenn that there are racist connotations to the word. They cautioned her about including “pōpolo” in the project’s title.

As a linguist and a black woman, Glenn understands this difficult relationship with language very well. Elders in her family still don’t like using “black” to reference their community because of how negatively it was used in the past. Yet “black” has undergone a cultural restoration, and is used to symbolize strength, unity, and celebration. The Pōpolo Project aims to add more layers to the word “pōpolo” by sharing the stories of black people in Hawaiʻi. If a harmless word for a medicinal herb can be weaponized as a slur, there is an equal chance that, with the right treatment, it can be used to empower.

“It’s really about creating a space for us to ask questions about what it means to be here, what it means to be in our bodies here, what it means to be representatives of our different lineages here,” says Pōpolo Project founder Akiemi Glenn.

Pōpolo Project members discuss the black experience in Hawai‘i online at fluxhawaii.com.

26 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Akiemi Glenn

Age: 37

Residence: Pālolo

Occupation: Linguist and executive director of the Pōpolo Project

“There’s not one way to be black from Hawaiʻi. It’s not just about being Barack Obama or Janet Mock. It’s about the different experiences. It links to a larger question of what it means to be black anywhere.”

Jamila Jarmon

Age: 35

Residence: Honolulu

Occupation: Special Projects at Elemental Excelerator

“I grew up here in Hawaiʻi, and I kind of grew up thinking I was the only one. Hearing about the Pōpolo Project and being able to create community is something I missed as a child. If we can do that now, at least I can have it as an adult, and we can create a community for children growing up in Hawaiʻi who are black.”

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 29

Edward Hemphill

Age: 28

Residence: Kahaluʻu

Occupation: Grant writer

“Storytelling is so important. The stories you are told about this place often ignore the stories that highlight injustice here. That’s what is really important to me about the Pōpolo Project—making the connections between stories of those impacted by colonization.”

Rechung Fujihira

Age: 35

Residence: Honolulu

Occupation: Owner of The Box Jelly

“Being black here is like being a superminority. When we were younger, there weren’t many black people. So I think our experience is definitely different, and we have been able to share and talk about that. Finding a community has been great.”

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 31

Ade Milligan (age 6)

Amari Milligan (age 8)

Nicole Maileen Woo (age 43)

Mark Feijão Milligan II (age 41)

Residence: Waiʻanae

Occupations: Artists and students

Nicole Maileen Woo

Nicole Maileen Woo

“Art has always also been at the crux of social and political change throughout the ages. And as a potent change agent, art holds the transformative ability to tell the stories of the marginalized with resounding voice and vigor. Stories build bridges. Yet for any story to be heard, a platform is crucial. The Pōpolo Project is such a platform.”

Mark Feijão Milligan II

“As a U.S. Virgin Islander, I see clear connections between the Native Hawaiian experience and the experience of people of the African diaspora. What we experience in the Atlantic, you experience here in Hawai‘i. Both peoples have spiritually rich cultures with strong ties to ancestral energy and ʻāina. Both peoples have withstood colonial oppression and are reclaiming our true legacies with unwavering pride as we move toward the future.”

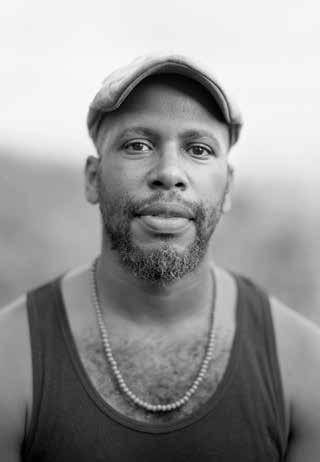

Hasan “Sonny” Scott

Age: 40

Residence: Honolulu

Occupation: English teacher at Kamehameha Schools at Kapālama

“As an African-American living in Hawaiʻi, I always appreciated when I saw my people out here, and I knew I wanted to connect with them and be able to expand that familiarity that we share. There’s nothing like being yourself around your people.”

Serena Michel

Age: 22

Residence: Kaimukī

Occupation: Student at University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

“ Before I moved here, I felt that I was always Dominican, but no one had ever given me permission to go back in time and connect to that—not even myself. So when I came to Hawaiʻi and saw how much ancestry and genealogy is so important here, I finally felt I could give myself permission to travel through the histories of colonization and trauma and revive that history through my writing.”

Call of the Wild

A few hours spent with a critically tiny but resilient group of ‘alalā, the Hawaiian Islands’ endemic crow, gives a glimpse into recovery efforts intended to bring the species back from the brink of extinction.

TEXT BY MATTHEW DEKNEEF

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK

We hear the birds before we see them. From somewhere amid the shaded terrain of ʻōhiʻa lehua and shady koa at the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center Discovery Forest, an unexpected caw cuts through the still, morning air. The screech, shrill and piercing, belongs to an ʻalalā, a crow endemic to Hawai‘i that most people have rarely heard, let alone seen. Its animal call, then, is cause for childlike excitement as we approach the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center, set in the interior of the forest’s 150 acres. It is at these Hawaiʻi Island headquarters located outside Volcano that the revival efforts of critically endangered native birds including the ʻalalā are spearheaded.

Designated “Extinct in the Wild” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species, the ʻalalā is the most threatened species of the entire crow family. Today, only 142 ʻalalā remain, the majority of which are cared for at the Keauhou center and a bird facility on Maui. Most notable, however, are the 11 ‘alalā living wild in the Puʻu Makaʻala Natural Area Reserve on the windward side of Hawaiʻi Island, where they were released by conservationists last year.

Bryce Masuda, the conservation program manager of the Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, leads me inside the Keauhou center’s main building to see two ʻalalā. “These are the most social of our birds,” Masuda says. Leo Mana and Po Noe, a 17-year-old male and a 10-year-old female, respectively, have become the most accustomed to guests. Their open-air aviary features sturdy ʻōhiʻa and koa branches on which the birds perch, a tray of fruits that include ʻōhelo berries to sustain their frugivorous diet, and a tire-sized container of water. We peer into the aviary from a viewing room designed to accommodate visits from schools, volunteers, the local community, and media.

Leo Mana and Po Noe are hard to miss. Their wingspans measure about 40 inches, and their bodies are roughly as wide as footballs. There’s a depth to their plumage, a silverblue luster that glows beautifully against the sun’s natural light. Around their necks are a ring of feathers that fans out like a fluffy beard. ʻAlalā are monogamous, and Leo Mana and Po Noe appear to be a match made in bird heaven, passing berries back and forth with their beaks to feed each other. The ʻalalā are more majestic, yet cuter, than I expect crows to be.

They are also noticeably inquisitive and alert. About half an hour into observing them, Po Noe, certainly the more expressive of the two that morning, picks up a tiny stick with her bill and pokes it into a hole in a log on the ground. She is probing for insects, Masuda

At the Keauhou Bird Conservation Center, researchers work to save the ‘alalā, or Hawaiian crow, designated “Extinct in the Wild” on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species.

FLUX PHILES | SCIENCE | 36 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

explains, a foraging talent he refers to as “tool use.” It is the most distinctive display of the ‘alalā’s intelligence—the South Pacific’s New Caledonian crow is the only other documented crow species to showcase tool-wielding abilities—and quite remarkable in the animal kingdom, considering that fewer than 1 percent of the world’s animal genera use tools.

There are still fundamental questions about Hawaiʻi’s native crow that scientists have yet to answer. “What does it mean for an ʻalalā to be angry at another ʻalalā?” Masuda asks hypothetically as we watch Leo Mana and Po Noe fly and hop about the aviary. Through observation, he hopes humans will one day know the answers to such questions. “The better we understand their natural behavior,” he says, “the better we can reintroduce them into their habitat.”

Like many native bird species in the islands, the ʻalalā has a familiar and tragic narrative. No one can assert what its normal population size was precontact, according to Masuda, but fossils indicate they were found throughout the Hawaiian Islands. The birds flourished enough to be heard far and wide by the native settlers— ‘alalā in Hawaiian means “to bawl, bleat, scream”—who figured them into Hawaiian

legends and gathered their feathers for kāhili, standards that symbolized nobility. Even Captain Cook, when he arrived at a village in Kawaʻaloa, was forewarned not to disturb a pair that were kept as ceremonial pets and considered ʻaumakua. Then avian malaria arrived with mosquitos, and settlers introduced predators like rats, mongoose, and feral cats, which eat birds and their eggs. By the early 1990s, fewer than 15 ‘alalā were known to exist.

The Keauhou Bird Conservation Center, operated by the Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program, opened in 1996—the same year the last ‘alalā egg was laid in the wild—with 18 aviaries dedicated to recovering the species. But due to disappearing forest, crow numbers continued to diminish. The last time a truly wild pair of ‘alalā were seen in their natural habitat was in 2002.

It takes a flock of institutions to save this single species. In this case, the Hawaii Endangered Bird Conservation Program, which includes the rehabilitation activities at Keauhou and on Maui, has partnerships with parent organization San Diego Zoo Global, the State of Hawai‘i Division of Forestry and Wildlife, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and Kamehameha

“The better we understand their natural behavior, the better we can reintroduce [‘alalā] into their habitat,” says Bryce Masuda, the conservation program manager of the Hawai‘i Endangered Bird Conservation Program.

38 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Schools for funding, permitting, and land management. The facilities serve as hubs where research and recovery teams monitor the captive birds, breed them, and incubate and hand-rear chicks. When the center pairs up the ʻalalā in aviaries, they start by matching the furthest related individuals to prevent inbreeding. In 2016, after increasing the species to more than 125 birds, Masuda oversaw a widely publicized release of five ʻalalā into the wild. The excitement was tempered when three turned up dead within two weeks of their release. (The remaining two were recaptured by specialists.) Masuda remembers the day he had to recover one. The bird was motionless in the grass, its breast torn and caked with blood. A necropsy revealed it was killed by an ʻio, the Hawaiian hawk, a natural predator of the ‘alalā. “It was just a shock,” Masuda recalls. “Just to come across it dead, it was devastating.” But it was also as nature would have intended.

Efforts to reintroduce the species are ongoing—the 11 ‘alalā released in Pu‘u Maka‘ala are succeeding in the wild, and 10 more are being prepared for a future release—and lessons continue to be

learned. The ‘alalā program now intends to introduce younger birds into the reserve, since they are expected to better adjust to their surroundings and fend off danger if they observe how other forest birds interact with predators. Eventually, researchers hope the first generation of ʻalalā will again be born in the wild. A thriving ʻalalā population would not only help recover the native forest through foraging and spreading seeds, but would also allow scientists to learn about their natural behavior and responses to the habitat. For instance, compared to all other crows and ravens, ʻalalā have the most vocalizations, according to Masuda. Researchers have identified at least 24 unique calls used in the aviaries. But they have also found that the ʻalalā’s vocal repertoire became less pronounced in captivity. This vibrant language originated in a dense, sprawling forest, and would be enriched if the birds could once again explore the region. As I leave the center, an ʻalalā calls out from within the aviary. It is impossible to discern if it is a cry of joy or despair. But it is reassuring to hear the ‘alalā, loud and clear.

‘Alalā are monogamous and highly intelligent, one of the fewer than 1 percent of the world’s animal genera that use tools to perform such tasks as foraging for food.

40 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

First Watch

At the base of Maunakea, the Kānaka Rangers keep a vigilant eye on the mountain to raise awareness of the lands surrounding it.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK & MIKE WILEY

Standing nearly 14,000 feet above sea level, Maunakea is a majestic vision rising before those traveling to its summit. Along the mountain’s primary access road, a vast expanse of field is matched by a vast expanse of sky. Near the juncture where the access road meets Daniel K. Inouye Highway stands a small, wooden booth that had appeared in the silent chill of dawn in the spring of 2018. “This wen drop outta the sky,” Hanale Halualani says of it. This booth is where Halualani and his fellow Kānaka Rangers, the self-appointed stewards of Maunakea’s Hawaiian homelands, assemble for voluntary eight-hour shifts to monitor the mountain’s activity. Easily spotted by their wide smiles and neon safety vests, they stand alongside the road welcoming summit visitors and offering sweaters, water, and refreshment to anyone who stops.

They aren’t there to protest anything, the Kānaka Rangers make clear. As kānaka maoli and custodians of the ʻāina, they are there to observe. Every hour of every day, a rotating shift of three rangers (with three on standby and three on-call) man the observation station, monitoring reports of trespassing, illegal tour operations, and unauthorized camping. In 2014, a fire that burned down two historic cabins of Humuʻula Sheep Station off the summit access road was caused by an unauthorized camper, Halualani says. On March 26, their very first night watch, the rangers caught someone stealing fence lines and notified authorities.

The Kānaka Rangers also log vehicles by color, type (Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources or University of Hawai‘i, for example), license plate, and passenger headcount. Monitoring activity is the first step in addressing land and resource management issues surrounding water, forestry, and wildlife on Maunakea state trust lands, the Kānaka Rangers say. It precludes the crunching of numbers that inform dialogue about infrastructure issues like roads and housing.

“[The Department of Hawaiian Home Lands] say they need $7 million to do what we are doing, to build something like this and pay staff to take numbers,” Halualani claims, raising his eyebrows. “And here we are doing it for free.”

Their checkpoint, or “observation station,” as they call it, was erected on a date of significance to the Kānaka Rangers: Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole’s birthday. “We

The Kānaka Rangers, a volunteer-led group at Maunakea, collect activity data and engage with summit visitors to help better address its land and resource management issues.

42 | FLUXHAWAII.COM FLUX PHILES | CULTURE |

want to bring awareness to his legacy,” says Halualani of the Hawaiian prince who served as Hawaiʻi’s first territorial delegate to U.S. Congress. In 1921, Kalanianaʻole spearheaded the passage of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act, which dedicated 200,000 acres of homestead land across Hawai‘i to Native Hawaiians of 50 percent or more Hawaiian blood quantum. Those eligible are to be awarded a 99-year land lease at $1 per year. Kalanianaʻole’s intent, according to beneficiaries like the Kānaka Rangers, was to “‘āina hoʻopulapula,” or to rehabilitate the land and its people, thereby preserving the values, traditions, and culture of Native Hawaiians. A fullblooded Hawaiian, Kalanianaʻole was brokenhearted over what he saw to be the dying of his race since the overthrow of the Hawaiian monarchy in 1893. The act was his effort to save it.

But in the near century that has passed since the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act was enacted, the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, the agency responsible for the provision of the act, has been stymied

by lack of funds and poor administration, according to Halualani. There are 10,000 homestead leaseholders statewide and more than 26,000 applicants who are waitlisted. “But in the last 97 years, over 9,000 have died waiting on that list,” Halualani says. (The Department of Hawaiian Home Lands did not return requests for comment.)

If the wait for a homeland lease isn’t painful enough, the irony of nonbeneficiaries being granted leases is an additional sting. The law allows for vacant land not yet awarded be leased to nonbeneficiaries to generate income to help carry out the objectives of the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act. However, nearly half of the allocated land is granted to non-beneficiaries rather than to the Native Hawaiians it was intended for, and often at an exorbitantly low cost. This includes large swaths of the 67,000 acres of state trust lands that unfold along Maunakea’s slopes. The University of Hawaiʻi pays $1 a year to lease 11,000 acres near the summit. Nearby in Pōhakuloa, the U.S. Army uses

The Kānaka Rangers checkpoint, or “observation station,” on Maunakea Access Road was erected on the birthday of Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalaniana‘ole, the territorial delegate who championed the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act.

44 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

nearly 23,000 acres for activities that include live-fire training at the rate of $1 for a 65-year lease period.

Retail enterprises, like Prince Kuhio Plaza shopping center, Walmart, Target, and Home Depot, all located in Hilo, were constructed on once-vacant Hawaiian Home Lands pasture lots. According to the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands website, commercial leases are awarded at market value. Still, a more pressing concern looms. “Where is the rehabilitation of the people when you destroy the land for commercial use?” Halualani asks. Rather than protest or excoriate the Department of Hawaiian Home Lands, the Kānaka Rangers prefer to be proactive. They want the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act better fulfilled by having more Hawaiians awarded their rightful lands, including those found at Maunakea. “This is the legacy we want to see succeed,” says Halualani of the Kānaka Rangers’ continuous presence and

monitoring efforts on the mountain. “To make it simple, better land management leads to accelerated land awards.”

The cool, spring morning of March 26th, when the Kānaka Rangers and their observation station made their first official public appearance, Halualani remembers two squalls accompanied by rain—“blessings,” he calls them—followed by a vivid ānuenue, or rainbow, stretching over the vast expanse of sky. He saw the rainbow as an auspicious sign, a hōʻailona, or blessing, and as acknowledgment from the ancestors. “The ‘āina needs kānaka, and the kānaka needs the ‘āina,” Halualani says. “That is why we Kānaka Rangers are here. This land is our kuleana.”

The Kānaka Rangers want to see the Hawaiian Homes Commission Act better fulfilled. Pictured, Mikey Kyser, Hanale Halualani, and Mai‘kai Kanui, who rotate shifts at the booth with other volunteers.

46 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

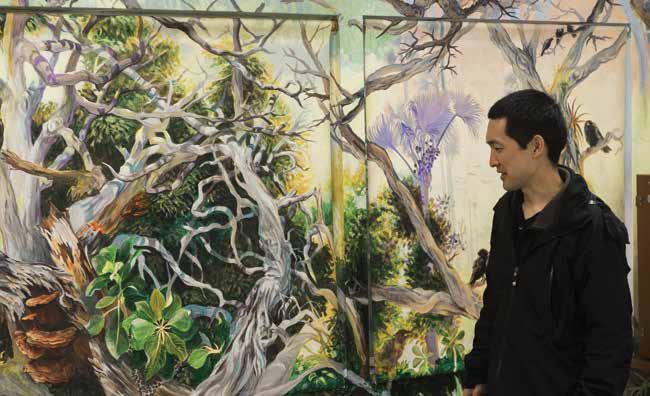

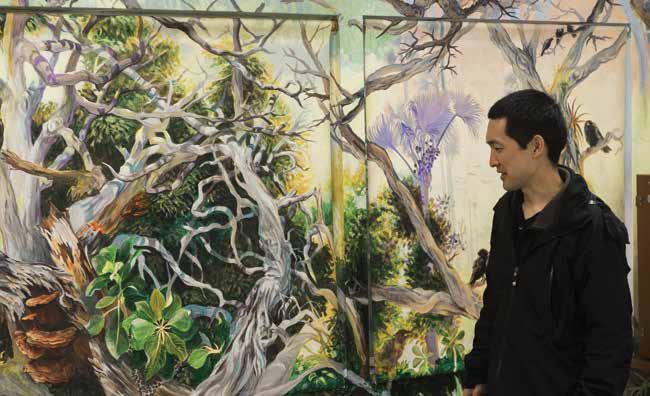

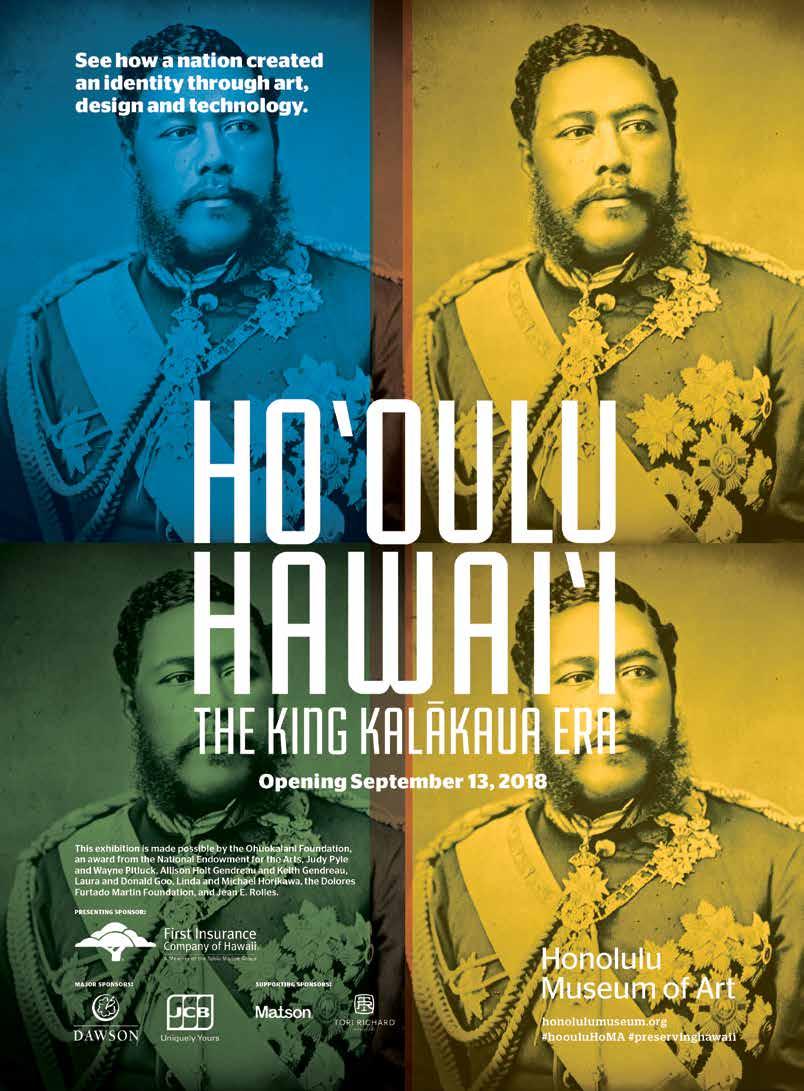

The Aesthetics of Annexation

Unearthing the Kilohana Art League, the most influential art society in Hawai‘i’s history that you have never heard of.

TEXT BY TRAVIS HANCOCK

More than 100 years before the 2018 Kīlauea eruption in lower Puna began drawing spectators with high-definition cameras, the same volcano attracted a second-generation missionary descendant from Hilo named David Howard Hitchcock to record its flows in sketches and watercolors. In 1885, the traveling French painter Jules Tavernier saw Hitchcock’s work and encouraged him to go abroad to master his skills. Hitchcock left for three years to study in New York and then Paris, where he managed to get an impressionistic painting of a French country road into the famed Académie des BeauxArts’ annual salon exhibition.

His European training complete, Hitchcock sailed triumphantly into Honolulu Harbor in November 1893—less than one year after the Hawaiian monarchy was toppled. Within a month, the haole-owned Hawaiian Gazette reported, “Our artist, D. Howard Hitchcock, has just returned from a two week’s sketching tour at the volcano and through the Puna district.” These sketches served as Hitchcock’s first studies for a Modernist line of works that culminated with a piece depicting a rare daylight view of the volcano. This painting, as described by art historian David Forbes, “showed the usual fiery lava lake but also had effects of strong, raking sunlight and clouds of blue vapor and gas rising from the pit.”

Today, Hitchcock and Tavernier are remembered as pillars of the Volcano School, the islands’ first major group of internationally recognized artists. For many years, the group’s molten landscapes set aglow a dedicated room at the Honolulu Museum of Art. But in 2017, the museum’s new Arts of Hawaiʻi curator Healoha Johnston broke up the paintings in her effort “to introduce new narratives about Hawai‘i’s social history through the lens of art,” as she wrote in her curator’s notes. Johnston’s intervention upended the idea that white Euro-American artists aptly represented the “Arts of Hawaiʻi,” a deeprooted notion first propounded by Hitchcock’s lesser-known artistic association, the Kilohana Art League.

Hitchcock launched this art society in May 1894 with a small exhibition on Hotel Street, with the purported aim of establishing a modern art culture in the islands. The group’s four founders—Hitchcock, woodcarver Augusta Graham, English sculptor Allen Hutchinson, and painter Annie H. Parke—chose the name “Kilohana,” meaning the topmost layer of a Hawaiian quilt or a high vantage point, to denote their excellence. By 1896, its membership had reached at least 125 members.

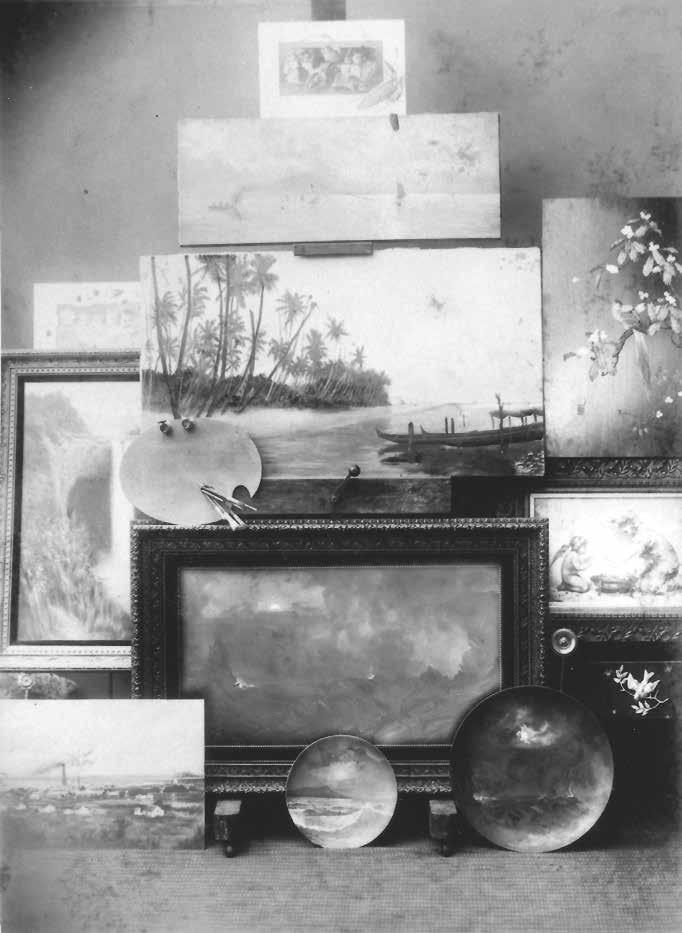

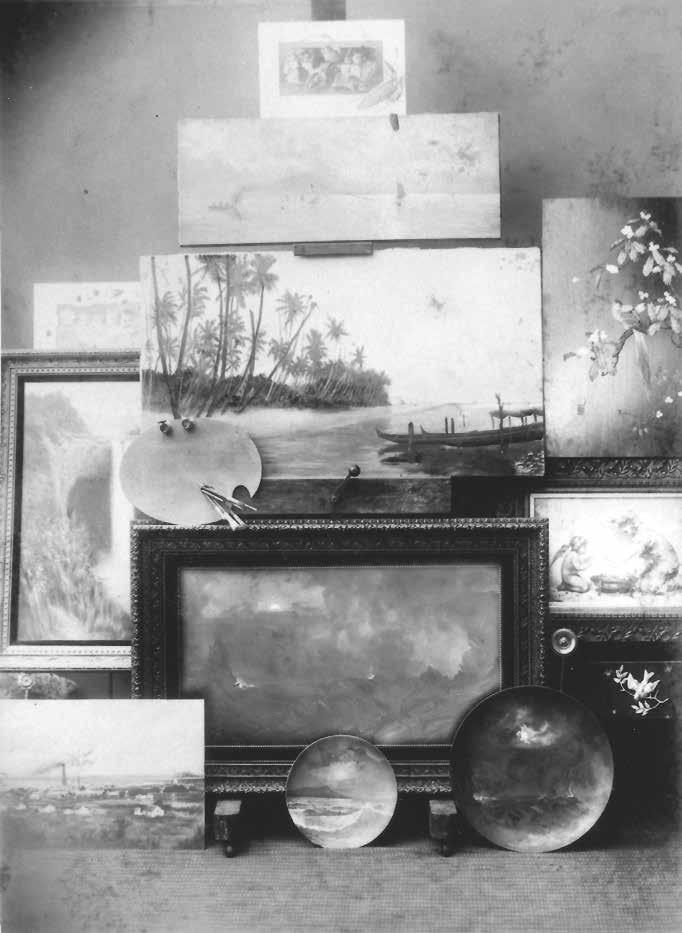

This advertising display from the 1890s at the King Bros. Art Store showcases motifs developed by Kilohana Art League artists. Shown center, an empty canoe on a tropical shore, likely painted by Jules Tavernier or D. Howard Hitchcock. Image courtesy of Hawaiian Historical Society.

FLUX PHILES | ART | 48 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The league participated in American expos, held literary contests, and hosted international artists, logging many of these achievements in a scrapbook now shelved at the Hawaiian Historical Society, where Kauaʻi-born art historian Stacy Kamehiro found it. “There are all these clippings of the exhibitions and what they were doing, and it sounded like more of a social club,” Kamehiro says. “Then when you looked and saw who was involved, it became clear that this social club was very much linked to the political clubs of the time.” According to her, if you look at the affiliations of those who joined the League, they were all linked to the cause of the annexing of Hawai‘i to the United States.

Kamehiro, who teaches at University of California, Santa Cruz, is currently exploring what she calls the “aesthetics of annexation.” Through what was essentially propaganda, Kamehiro argues, the league was “able to create a cluster of images of belonging to a place, of thinking they belong to a place, and claiming it.” She cites portraits of haole elites, paintings of their homesteads and

lush plantations, and images of a decaying traditional life—all of which were geared toward proving the viability of American culture in the islands. “When they do show something like a hale, a Hawaiian home, it’s usually dilapidated,” Kamehiro explains. “It’s very much about, ‘This is passing, this is gone. It’s going away, and we’re replacing it with all of our prosperity.’”

Hitchcock also leaves Kamehiro suspicious. “Hitchcock does 20 to 30 paintings of empty canoes—canoes on beaches with no people, no Hawaiians attached to them,” she says. “There is a literal and also sort of symbolic removal of kānaka maoli from the landscape, whereas Robert Barnfield and Joseph Strong, who were friends of [King] Kalākaua, were showing brown bodies, kānaka maoli bodies, who were engaged with canoeing, fishing, doing stuff. Strong also showed pictures of the Japanese immigrants, which were completely absent from the Kilohana Art League. They didn’t want to show the Asians at all.” This art of removal extended to the league’s 1899 literary collection, Six Prize Stories, which

50 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

The Beach at Waikiki , D. Howard Hitchcock (1861 – 1943), 1896 oil on canvas, Bishop Museum.

featured five stories by named white authors and a sixth assigned only to “A Native.”

By the early 1900s, the vast league was subdivided into circles, including painting, music, drama, reading, and later, the outdoors—the last of which is now known as The Outdoor Circle, an environmental nonprofit. The circles held gatherings around the city until the wealthy businessman and politician Charles Montague Cooke granted them the use of a large building on Beretania Street. When the sprawling league fractured apart in 1913, many of its pieces ended up in Cooke’s collection. In 1927, his wife, Anna Rice Cooke, transformed her Beretania home into the Honolulu Academy of Arts, which became the Honolulu Museum of Art in 2012.

In May, as Kīlauea continued to erupt through fissures in lower Puna, making national headlines, Kamehiro, who has family on Kaua‘i and O‘ahu, was among the many people to receive messages from distant friends asking if they remained

safe from the flow of the eruption. Somehow, in 2018, the media failed the islands’ geography and led mainlanders to believe lava may be inching toward any and every home in the state. This is nothing new. Through 240 years of alleged representation in ink, paint, film, and pixels, Westerners have allowed Hawai‘i Island’s smoking peaks to blind them from the whole picture. It is the same cultural smokescreen that first billowed in with the Volcano School and floated up to new, commanding vantages, the supposed “kilohana,” in the hands of artists whose early visions of fire and brimstone became the forge and cornerstone of an ingenious, igneous ignorance.

Halemaumau Eruption at Night , D. Howard Hitchcock (1861 – 1943), 1917 oil on canvas, courtesy of Honolulu Museum of Art, gift of Aaron G. Marcus, 1978 (4612.1).

52 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

FLUX FEATURE

A Place of Ref uge

As the cost of living in Hawai‘i becomes an insurmountable hurdle for some, thousands are left to pick up the pieces and patch together a new normal. Welcome to another day at Hawai‘i’s largest homeless village.

TEXT BY RAE SOJOT

IMAGES BY MARIE ERIEL HOBRO, CIDNEY KELLY, AND LILA LEE OF WOLF & WOMAN

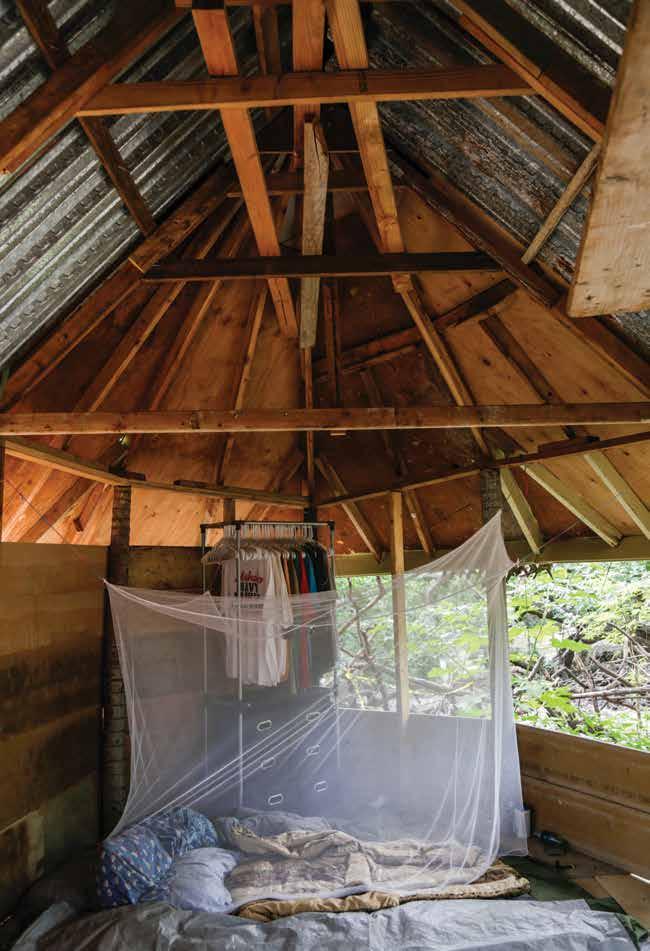

Sprawled across nearly 20 acres of dusty underbrush near Waiʻanae Boat Harbor, a patchwork of tents and shanties peeks out from groves of kiawe and haole koa. A battered couch sits at a main entrance, offering brief respite for those coming or going along the warren of well-trod dirt paths. A sun-weathered man hauling a precariously loaded dolly of food picked up from a Hawaiʻi Foodbank distribution site is greeted by a small pack of children. When he fishes out a tray of cupcakes for them, they shriek in delight. Their mothers cluck their tongues in good-natured exasperation. It’s nearly dinnertime, but they don’t protest. Such is the amicable spirit found at Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae, Hawaiʻi’s largest homeless encampment. Here, the residents don’t see themselves as homeless, just house-less.

As Hawaiʻiʼs increasing cost of living continues to plague local families, island residents eke out livelihoods while facing expenses that are nearly two-thirds higher than the rest of the United States. According to a 2018 Out of Reach report from the National Low Income Housing Coalition, Hawai‘i has the highest cost of rent in the nation, and wage earners here need an hourly wage of $36.13—a far cry from Hawaiʻi’s minimum wage of $10.10—in order to afford the average two-bedroom rental. Not surprisingly, a recent survey found that nearly half of Hawaiʻi residents live paycheck to paycheck. For many, an unexpected job loss or medical expense could land them in the red, or in the worst case, out on the streets. For many, that worst case has already happened: For the last five years, Hawaiʻi has had the nation’s highest rate of homelessness per capita. Current estimates place the islands’ homeless population at more than 7,000.

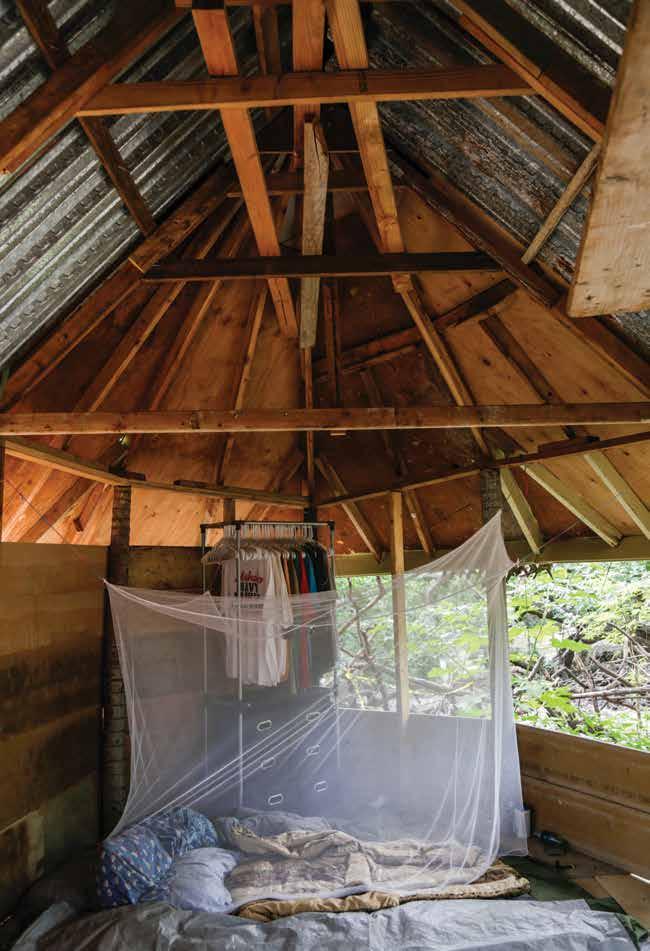

Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae, or the Refuge of Waiʻanae, has become a mecca for those who seek safe shelter. But the living conditions are far from ideal for the 170 people or so who live there. Residents confront a laundry list of challenges: constant exposure to the elements, no running water or electricity, rats and scorpions, too. “Survival of the fittest? No, survival of the smartest,” says a 64-year-old woman who goes by Auntie Joey. She has called Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae home since 2011. “Living like this is gonna harden you,” she says. “You gotta develop a sense of strength.”

56 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Though there are a dozen or so formally registered shelters and transitional homes in Waiʻanae, those who find themselves at Puʻuhonua o Wai‘anae are drawn to its community ethos. Managed by people who live there and not well-meaning outsiders, the village is absent of any patronizing charity. There, the focus is on compassion and connection, empathy over sympathy. “We have rules no different from a shelter,” says Twinkle Borge, who, for the last 10 years, has helmed Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae. “But for me, you need to have and build relationships with the people. In our village, everyone knows everyone.”

Borge was grappling with the loss of her job as a trainer for Big Brothers Big Sisters delivery drivers, as well as a broken heart from a tumultuous relationship, when she headed west in 2005. “I was getting away from it all,” Borge says. “I just never went back.” Back then, the area inland of the harbor was reputed as a haven for derelicts, drug users, and outcasts, not those just simply down on their luck. But Borge, who grew up in Pālolo, brought her own bit of street cred: As a teenager, she had a flair for the illicit, running an all-girl gang that stole cars and broke into houses. As an adult, she was a recovering addict. “I needed to build bridges first with the community here,” Borges recalls. So she took initiative to connect. “I would watch people clean their areas and walk over and help.” Her forthright, pragmatic bearing, softened by a calm and compassionate demeanor, soon earned the trust of those around her. She emerged as the guiding voice and matriarchal fulcrum of the camp. People sought her for advice, help, or sometimes just a hug. However, as more families began arriving with young children in tow, Borge found herself thinking of the hānai son she had raised in his infancy. A safer space was needed, Borge decided. More order, too. “It’s not their fault why [the children] are here,” Borge says. “It’s my job to protect, educate, and love them.”

Galvanizing other likeminded residents, Borge implemented and enforced strict camp rules. No sex offenders. No drugs. No stealing. No loud noises after 8 p.m. For many, the benefits of being a part of the village were worth these restrictions. As Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae’s population expanded, a hierarchy evolved, helping establish a chain of command to which residents could bring their concerns or requests for help. Any disagreements were mediated by either Borges or her “block captains,” a crew largely composed of women that she had tasked with managing the different sections of the village. Infractions resulted in warnings, first verbal, then written. Serious offenses, like repeated drug use or stealing from residents, nearby businesses, or Waiʻanae High School, which sits adjacent to the camp, led to the gravest punishment of all: eviction. “If you steal, you out,” Borge says. “We are trying to build relationships, not break them.” Asking a resident to break down their camp and leave is a task Borge never finds easy. “It hurts more so if they have kids,” she says. Often, Borge will offer to take in the children.

“You need to have and build relationships with the people. In our village, everyone knows everyone,” says Twinkle Borge, who has helmed Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae, Hawai‘i’s largest homeless encampment, for the past 10 years.

As undesirable behaviors were pushed to the outer fringes of the camp (Borge estimates drug use has declined from 90 percent to about 20 percent), a marvelous effect began to happen in its interior: What was initially a casual affiliation of camp dwellers was coalescing into a cohesive community. Residents, encouraged by the sense of structure and the feeling of being part of a larger collective, began transforming their plots into more permanent, elaborate homes, erecting low coral walls and fences, even planting gardens. People helped each other. The ablebodied assisted kūpuna in filling water jugs, and neighbors equipped with shovels, digging sticks, and rakes worked together to clear out a resident’s tent site that had burned down. New arrivals vetted by Borge and her captains were given a village walk-through and briefing before being assigned a site. If someone came empty-handed, essentials like bedding, a week’s-worth of food, perhaps even a tent—cobbled from the village’s donations or even the personal caches of residents—were provided. That tenor of generosity and inclusivity continues today at Puʻuohonua

58 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

o Waiʻanae, which, despite its hardscrabble exterior, feels like a tight-knit neighborhood.

Aristotle’s concept of the whole being more than the sum of its parts is on vibrant display during dayto-day life at Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae. The camp’s center operates like a town square of sorts where residents pull up metal folding chairs to talk story while children play tag and ride bikes along the dusty trails. Just like in any other neighborhood, the kids are reminded not to trample residents’ yards lest they be scolded by their occupants. Kids being kids, the warning is lost to the breeze.

Among the camp’s 16 children are Borge’s seven hānai sons and daughters, who range in age from 2 to 15 years old. They live in Borge’s sizable multitent structure off the camp’s main thoroughfare. The floor plan is cozy: an assortment of small, communal “rooms” partitioned by suspended sheets and tarps radiate outward from a makeshift kitchen. It’s a late spring afternoon when one of Borge’s adult hānai daughters, Queenie, who lives at the camp and helps take care of the children, surveys its current state of affairs, like a parent checking to see if a child’s room is clean. In the children’s sleeping quarters, she lets out an exasperated sigh as she picks her way through a carpeted area strewn with clothes, school

supplies, and toys. In stark contrast is another child’s space a few feet over, where a mattress is stacked with carefully folded bedding and a plastic storage bin that serves as a nightstand houses neatly arranged knickknacks. “Some people are messier than others,” Queenie says with a grin.

For Borge, the welfare of Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae’s children is paramount. Their safety, health, and

happiness serve as a barometer of the village’s success. This emphasis was demonstrated six months ago, when a new family arrived to Pu‘uhonua with 8-year-old Kyhroe, who was deaf. Unfamiliar with his new surroundings and unable to communicate with anyone other than his family, Kyhroe’s assimilation was difficult. Feelings of helplessness would frequently boil

Sixteen children live in the camp—seven of which are Borge’s hānai sons and daughters—and the welfare of these kids is paramount, hence a set of strict rules enforced by Borge and a crew of “block captains” tasked with managing different sections of the village.

60 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

Once a casual affiliation of camp dwellers, Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae is coalescing into a cohesive community, with residents taking pride in their plots and building them into more established homes, even erecting low coral walls and fences and planting gardens. Shown here is resident Josiah Koria’s home at Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae.

Josiah Koria, who is active duty in the U.S. Navy, moved to Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae after founding Tyrell’s Angels in memory of his 1-year-old nephew Tyrell Ioane Niko, who died after being struck by a reversing vehicle. Tyrell’s Angels helps homeless children and their families live healthy, independent lives.

over to frustration, then rage, causing him to lash out and scream at others. Rather than ostracize Khyroe, the village sought a solution: If the boy couldn’t speak to the village, then the village would learn to speak to the boy. Xeroxed copies of the American Sign Language alphabet soon appeared on community bulletin boards. Borge arranged for teachers from the Hawaiʻi School for the Deaf and Blind to come teach the residents how to sign. The children especially picked up the hand gestures eagerly. The village had built a bridge.

As the sun dips below the ocean’s horizon, young children in groups of twos and threes cheerily make their way to the Wai‘anae Small Boat Harbor parking lot. It’s time to bathe. A few teenagers trail after them, towels draped across their shoulders and plastic buckets under their arms. Queenie explains that on school nights, children are to be washed and fed by nightfall. The older ones are responsible for helping with the younger ones. (Borge, aware of complaints about Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae’s contribution to the harbor’s exorbitant water bill, instructs residents to only shower and fill their water jugs after 4:30 p.m. She also says she has offered to work with state officials to pay for the water usage.) Two young fishermen from Honolulu who had spent the day plying the west side’s premier fishing ground are rinsing off their boat while knocking back some beers. They avert their eyes as the children expertly attach a rubber hose to one of the harbor’s four water taps. The kids initially balk at getting wet—the stream of water is ice cold. But moments later, they’re splashing each other and dumping buckets of soapy water on each other’s shoulders. From their boat, the fishermen watch the drama unfold, their faces a thinly veiled mixture of curiosity, embarrassment, and pity. Quietly, one wonders to his friend if the group’s toddlers had ever experienced a hot shower. “So sad,” the friend replies, shaking his head. If the teenagers overhear this, they are nonplussed. The younger ones, now shooting the hose at each other, are oblivious. Their jubilant laughter rises up to the sky.

Wanting to check on the children, Borge zips to the parking lot in a beat-up golf cart. This cart, much like Borges’ cellphone, is an indispensable tool for managing the daily operations of the village and connecting with its residents. When she is not using it to transport heavy supplies to campsites (or humoring the children with an occasional spin), Borge makes her rounds along the village’s myriad trails. She visits with residents to see if they might need anything, looks out for safety hazards like a precarious tree branch or a hole, and surveys areas that could be cleared for any new residents. There’s always something to do. She admits that she feels burned out sometimes, her anxiety levels reaching points where she can’t sleep or eat, especially when she wonders of the village’s future. Ultimately she pushes through these dark periods by finding strength and solace in the community she helped to create. “This is my home,” Borge says. Greeting Queenie in the lot, Borge smiles broadly at the children, who are now cocooned in towels. As mother and daughter catch up on camp news, Leilei, a precocious 2-year-old, climbs atop Borge’s lap for a quick snuggle. Queenie inquires about Borges’ plans for the evening—will she be joining for dinner? Borge says she needs to check on a complaint first. Apparently, a resident has been allowing her trash to pile up in front of her tent. Not only is it an eyesore, but it is also attracting rodents. Trash disposal is a chronic issue and headache for Borge, especially when Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae critics cite sanitation issues as a clarion call to disband the village. For now, residents do what they can, regularly hauling their trash to the harbor’s dumpsters until a better system can be implemented. She needs to find out what’s going on with the resident. She turns the ignition, and the cart’s engine throttles gently. Placing Leilei back with the other children, she waves and heads off. Back in the village, all is quieting down. Generators hum against the susurrations of the evening’s light tradewinds. Sounds of dinner preparations drift from the tents. A lamp crafted from a large plastic jug and a solar panel pad hangs from a kiawe branch. It casts a soft light on Puʻuhonua o Waiʻanae’s main path, guiding the children home.

“If you steal, you out. We are trying to build relationships, not break them.”

Twinkle

Borge

Despite its hardscrabble exterior, Pu‘uhonua o Wai‘anae feels like a tightknit neighborhood.

64 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

66 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUX FEATURE

T he Senior s Str ike Back

It’s a game of old Kailua versus new Kailua, and the community’s kūpuna who bowl at Pali Lanes aren’t backing down without a fight.

TEXT BY MARTHA CHENG

IMAGES BY IJFKE RIDGLEY

It was never just about saving a bowling alley.

On a recent Monday night, Arthur Machado, Jr. stood in front of the Koolau Seniors bowling league before their weekly match at Pali Lanes. He spoke passionately about saving the Kailua bowling alley he owned. He vaguely mentioned lawsuits, he talked about fighting Alexander and Baldwin. More than 5,000 people had signed the Save Pali Lanes online petition. In late 2017, Alexander and Baldwin, which owns the land under the bowling alley (as well as 38 acres in downtown Kailua, which it had purchased from Kaneohe Ranch and the Harold K.L. Castle Foundation in 2013) had announced that when the lease for the bowling alley expired in January 2019, it would raze the building to create a new community space, possibly an open area where farmers markets or food trucks could gather. But Machado said it already was a gathering place, one for seniors on the Windward side of O‘ahu. It was an easy cause to get behind, and the Kailua community was inspired by the example set by the petition to save the monkeypod trees in Mānoa Marketplace,

another property owned by Alexander and Baldwin. The developer had planned on removing the trees, but when it was presented with 20,000 signatures and a proposal for how to manage the trees’ roots, which were cracking the pavement, it decided against cutting them down.

By the time Machado spoke to the seniors that night, Alexander and Baldwin had already announced that it was putting its plans for Pali Lanes on hold. But people are still fired up. The bowling alley has come to represent something more than 24 lanes and a bunch

“My doctor says don’t walk the sidewalks, because they’re all uneven, you’ll break your neck. Just keep rolling that ball,” says 97-year-old Mary Sabate, at left, who still bowls with a 10-pound ball. She carpools with her friend, Marion Teixeira, to Pali Lanes every week.

68 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

of pins. It is a symbol of old Kailua, and it is something very tangible for the older residents of the community.

The senior bowlers who frequent Pali Lanes include Mary Sabate, who is 97 years old and still bowling with a 10-pound ball. When people tell her, “You too old for that,” she retorts, “What are you guys doing? Getting fat.”

Says Sabate, “My doctor says don’t walk the sidewalks, because they’re all uneven, you’ll break your neck or fracture your knee. Just keep rolling that ball. When the ladies want to quit, I say, no it’s your physical therapy, you need the exercise.”

She had just returned from Reno, Nevada, where she competed in a women’s national bowling championship. It’s her 37th year participating in it. Asked how her team did, she says, “Well, you don’t expect the oldies to win [against] the younger ones.”

Sabate has lived in Kailua for 62 years, and started bowling before Pali Lanes was even built in 1961. Where there are now condominiums, she remembers a dairy farm and Kailua’s first bowling alley, which opened in 1947, around the same time as a telephone company branch office and Hawaiʻi’s very first supermarket.

If Pali Lanes closes, Sabate thinks she will retire from bowling. At a recent Kailua neighborhood board meeting, she said, “My biggest question for the people who want to tear it down: Do you folks have a plan for the seniors?”

But the solutions for the seniors are not as straightforward as managing the roots of the Mānoa Marketplace trees. “Bowling is a dying sport,” says Ruth Chatterton, secretary for the Koolau Seniors. At the Monday night bowl, the league, in which members compete against each other in teams of three, is two members short. One person had to drop out for medical reasons,

another had passed away. She remembers when there were 36 bowling alleys on Oʻahu, including one that was literally underground, below Fort Street Mall in downtown Honolulu. Now there are only four: Aiea Bowl, Leeward Bowl, Barbers Point Bowling, and Pali Lanes. “The waitlist used to be so long for lanes, now I’m begging [people to join],” she says. After Machado’s speech, he returns to his office, tucked in the back corner of the alley, past the concession stand. Here, Machado is quieter, more contemplative. There’s no mention of taking anyone to court, just a float for the Kailua 4th of July parade. He tenderly recounts his relationship with the sport. “Bowling has always been my love,” he says. Machado has been bowling for 54 years. He ran K-Bay Lanes on the Marine Corps Base Hawaii in Kāne‘ohe for a quarter of a century, from the day it opened in 1976. In 2010, he and two partners reopened Pali Lanes, which had closed at the end of 2009. But it has never made much money. Machado says it costs him $18,000 a month to run Pali Lanes, and he has been lucky if he gets one or two bowling party reservations a month. So when Alexander and Baldwin announced they would end his lease, Machado considered letting the bowling alley go. But then a group of 20-somethings who grew up in Kailua told him to fight for it, and they created the Save Pali Lanes petition. Reservations for the bowling alley flooded in, and it was booked every weekend from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m. for the summer. The public outcry over the demise of Pali Lanes has been enough for Alexander and Baldwin to pause its plans and reconsider.

The reaction might have surprised the developer, which probably saw an aging bowling alley frequented by a dwindling

“The lanes have always been a special place for families and communities to gather, and we’re not going to let them be sold out just to turn Kailua into a moneymaking tourist attraction.”

—From the Save Pali Lanes petition

When Alexander and Baldwin announced plans in 2017 to raze Pali Lanes, owner Arthur Machado, Jr., above, began working with Evan Weber to create the Save Pali Lanes petition.

72 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

number of seniors, a few bowling leagues, and the occasional bored teen on a weekend night. But one’s crumbling eyesore is another’s symbol of nostalgia. Pali Lanes is one of the last vestiges of a Kailua that generations frequented and loved, before the tourists came in such droves that there are now laws to reign in commercial beach activity and street parking, before the low-slung, post-war era buildings that once characterized Kailua were demolished for commercial centers anchored by Target and Whole Foods. Nevermind that many of us didn’t go bowl, that many of us just saw Pali Lanes on our way to Target. Nevermind that we had forgotten about Pali Lanes until we heard it was closing.

Right now, Alexander and Baldwin isn’t making any promises about the fate of the bowling alley. It is conducting a round of surveys to “understand what the community’s interest and concerns are,” says its spokesman Darren Pai. “We don’t want to draw any conclusions at this point. We’ve really heard a whole range of opinions. Not just about this particular situation, but about Kailua.”

This is what the Save Pali Lanes petition was truly about all along. Evan Weber, who is from Kailua and created the petition, says, “Over the past couple of decades, there’s been a steady change in our town, loss of businesses for more places that serve the interests of developers by catering primarily to tourists and people who have not lived in Kailua their entire lives.” For the youth, who have a future longer than the past, there is more at stake. “Pali Lanes is a special place for families and community,” the 26-year-old adds, “and to me, this is the last straw over what ’s been happening here.”

In contrast, Chatterton is resigned. “Guess we gotta go with progress,” she says. The Kailua she lived in when she was young is already long gone. She left Kapahulu for Kailua, left the city for the country, and stayed long enough for the city to catch up with her, to see the horse racetrack give way to Aikahi Shopping Center. She prefers the old Kailua, but admits to liking Target. And she knows interest in bowling is already waning. There’s talk of relocating the leagues to K-Bay Lanes if Kailua loses Pali Lanes. But even if that happens, Chatterton might retire anyway.

74 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

FLUXHAWAII.COM | 75

Patriots Adrift

For decades, Micronesians have risked and even sacrificed their lives fighting for the United States, despite not being U.S. citizens. As they begin to retire, these islanders are finding that their unique immigration status leaves them in limbo.

TEXT BY TIMOTHY A. SCHULER

IMAGES BY JOHN HOOK, KYLE KOSAKI, AND COURTESY OF TOM RAFFIPIY

Tom Raffipiy looked out the window of the plane, nervous. He was 30,000 feet in the air, flying over the rugged, desolate landscape of the Western United States. The Satawal native had never seen a landmass so large, and it was unsettling to him the way the ground stretched to the horizon in every direction. “I’d always traveled across ocean,” says Raffipiy, who was 20 years old at the time. “I was nervous because I know that if we fall down, I don’t have a chance. If we fall down in the ocean, it can take the impact.” Every so often, he would check the view. Still no water. The continent seemed endless.

Raffipiy, now 52, was a newly enlisted soldier in the U.S. Army on his way to Fort

Leonard Wood in rural Missouri. Up to that point, Raffipiy had spent most of his life on a tiny, boomerang-shaped island called Satawal that is part of the Federated States of Micronesia, or FSM. Like many Pacific Islanders, Raffipiy grew up close to the land and closer to the water, fishing and sailing traditional outrigger canoes, which by age 9, he also knew how to build. As a boy, he spent portions of nearly every day with Mau Piailug, the famed navigator who is credited with helping revive Polynesian voyaging worldwide.

In 1985, Raffipiy left Satawal to attend the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo. Flying into Honolulu at night, Raffipiy wondered if he had made the right choice. The city was enormous, glowing like a million

FLUX FEATURE 76 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

embers. When he arrived in Hilo, however, he found the pace of life familiar. What he was unprepared for was how expensive things were. Even with financial aid and a parttime job, Raffipiy couldn’t afford tuition, rent, and groceries. After one semester, Raffipiy realized he needed to change course. Although Raffipiy wasn’t a U.S. citizen, because of an agreement called the Compact of Free Association, or COFA, he was allowed to serve in the U.S. Armed Forces. He called the local recruiting office.

Today, the geographic area of Oceania in the Pacific is broken up into four major regions: Polynesia (which includes Hawai‘i), Australasia, Melanesia, and Micronesia. Micronesia stretches from Kiribati, 1,840 miles south of Hawai‘i, all the way to west Palau, just a few hundred miles from the Philippines, and includes the FSM as well as the Marshall Islands, Nauru and the U.S. territories of Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Altogether, Micronesia covers an area roughly the size of Australia. Although the world has chosen to group them, not all islanders from Micronesia consider themselves “Micronesian.” Many of the islands are culturally distinct, with their own languages and customs. However, citizens of the FSM, Palau, and the Marshall Islands are linked in one important way: COFA.

To understand the far-reaching effects that COFA continues to have, you have to first understand the history of Micronesia. Because of their location, the Micronesian islands have been places of strategic interest for foreign powers over the decades, including the United States, which oversaw much of the region as a United Nations Trust Territory from 1945 through the mid-1980s, when the FSM and the Marshall Islands voted to become sovereign nations. (Palau became independent shortly thereafter.) Treaties were negotiated with each of the fledgling republics, and in return for permission to

maintain military operations there, the United States promised economic assistance and free entry into the country. With the signing of the compacts, COFA citizens were permitted to live and work in the United States without a visa.

Today, nearly 50,000 people from the FSM alone have emigrated to the United States, representing a third of the Micronesian country’s total population. Hawai‘i in particular has become a landing pad for COFA migrants, due to its proximity and cultural similarities to Micronesia. According to Census data, between 20,000 and 30,000 Micronesians live in Hawai‘i.

There is one other area of American society in which islanders from Micronesia are highly visible: the U.S. military. According to the U.S. State Department, citizens of the FSM enlist at double the per capita rate of U.S. citizens, and the figure is likely similar for citizens of Palau and the Marshall Islands. A 2005 article published in USA Today described the Micronesian islands as a “recruiter’s paradise.” One recruiter glibly told The New York Times, “You can’t beat recruiting here in the Marianas, in Micronesia. In the States, they are really hurting. But over here, I can afford go play golf every other day.”

Some islanders believe the region is being unfairly preyed upon and have urged their community’s young people to consider alternatives to military service, even organizing “anti-recruiting” sessions at local high schools. Political and religious leaders have weighed in over the years, arguing that as independent nations they shouldn’t be fighting America’s wars. Others have said war itself goes against Micronesian values.

Such sentiments haven’t stopped individuals like Raffipiy from enlisting. Shortly after he called the recruiting office in Hilo, Raffipiy found himself in Missouri, 8,000 miles from home, adjusting to his first Midwestern winter. At Fort Leonard

Wood, Raffipiy began basic training. To his surprise, it was relatively easy. The push-ups, the sit-ups, the early morning runs—none of it was more demanding than life back on Satawal. “A lot of mainland kids were crying, but for me, I’d already lived through that. Running was something we always did on the beach. It’s a lot harder to run in the sand than on the road,” he says. When training exercises required that soldiers stay up nearly all night, Raffipiy was used to that too, having done so while voyaging to other islands. He discovered that despite having grown up on an island less than one-tenth the size of the base, he knew a lot about the world. Eventually, he began to think of basic training as a game—a game at which he realized he could excel.

A lot of people assume that islanders like Raffipiy enlist in the military purely for financial reasons. It certainly is a factor. For Raffipiy, Hawai‘i was prohibitively expensive. But things were even more bleak back home. Places like the FSM have found themselves navigating the tenuous transition from subsistence fishing and small-scale farming to a more Westernized way of life. Jobs are scarce. Those that do exist don’t pay well. A teacher on Kosrae, for instance, might make as little as $7,000 per year. By comparison, the Army offers a starting salary of nearly $20,000 plus allowances for cost of living, signing bonuses, and benefits.

But Raffipiy also exhibits a palpable sense of patriotism when he speaks. It is clear that he believes in values

Like many migrants from the Federated States of Micronesia, Tom Raffipiy enlisted in the military under the Compact of Free Association. Because of their unique immigration status, many Micronesian soldiers are left in limbo once their service ends, unable to access the same benefits as U.S. citizens.

78 | FLUXHAWAII.COM

like democracy and freedom, and that he is willing to risk his life for them. He is not alone. Owen Milne grew up on Kwajalein in the Marshall Islands. He joined the Army after quitting several entry-level jobs in Tampa, Florida, where he was living with his sister. For Milne, the Army represented a path to financial independence, but also, he hoped, a job more exciting than bagging groceries. After basic training, Milne was assigned to the 173rd Airborne Brigade, learned how to jump out of helicopters, and got a job in logistics, ensuring that his unit’s supplies made it to the right place at the right time. He did two tours in Iraq and one in Afghanistan, and is now stationed in Hawai‘i. Along the way, he met his wife, Regina, who is also Marshallese and spent six years working in Army intelligence.

Milne says he doesn’t feel any sort of cognitive dissonance fighting for the United States even though he is not an American citizen. “We’re not fighting just for the United States,” he says. “The Marshall Islands don’t have an army. We’re the army. So I don’t care what anybody says, we’re fighting for the Marshall Islands, we’re fighting for the United States, and we’re fighting for every ally of the United States.”

In one sense, the patriotism is befuddling since for years the Marshall Islands served as America’s nuclear testing ground. From 1946 to 1958, the United States detonated more than 60 atomic bombs off Bikini Atoll, destroying the island’s ecosystems and exposing thousands of islanders to radioactive fallout, a horrifying event that resulted in the deaths of some islanders, a plague of stillborn babies, and adverse health effects that continue today. In another sense, however, military service is simpatico with Micronesian culture, says Josie Howard, director of the Hawai‘i-based nonprofit organization We Are Oceania and a native of Onoun in Chuuk, part of the FSM. Many islanders volunteer “because it’s a service to humanity,” she says.

And yet Micronesians who serve are hamstrung in an important way: Because they are not U.S. citizens, they cannot become commissioned officers, which limits what they can make in terms of salary and

the level of recognition they can receive. In the Army, the highest rank an enlisted soldier can achieve is sergeant major, or E-9. If they have served for more than 20 years, they can expect a salary of a little more than $70,000 a year. A commissioned officer such as a colonel, however, can easily make six figures. No matter how hard they work, Micronesians in uniform will forever be excluded from the more prestigious rungs of the military ladder.